Abstract

This study examines how online gamification for environmental protection influences university students’ organisational citizenship behaviour toward the environment (OCBE). Grounded in the Cognitive Affective Personality System (CAPS) theory, it investigates how environmental responsibility and environmental passion jointly mediate this relationship through cognitive and affective pathways. Using a dual-mediation framework and survey data from university students engaged with online environmental gamification platforms, the study evaluates both the direct and indirect effects of gamification on OCBE. The results indicate that gamification positively predicts OCBE, operating not only through a direct effect but also through indirect effects via strengthened environmental responsibility and heightened environmental passion. These findings provide empirical evidence for the dual cognitive affective mechanism underlying OCBE. By applying CAPS theory to a digital behavioural context, this research identifies gamification as an effective contextual trigger for pro-environmental organisational behaviour. The study contributes to the sustainable behaviour literature by clarifying how digital gamified environments can foster continuous engagement and offers practical guidance for universities and platform designers to promote students’ participation in green initiatives through the co-activation of responsibility and passion.

1. Introduction

Environmental engagement has moved up policy and research agendas in response to accelerating ecological risks. Escalating climate and ecological risks have pushed environmental action up global agendas. The increase in environmental pollution and ecosystem degradation has become more severe, threatening our progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [1] (p. 100004). The SDGs embed environmental targets and call for coordinated international responses [2]. Against this backdrop, identifying effective ways to mobilise public engagement in ecological action—particularly among younger generations—has become a pressing priority in environmental governance. Given ongoing value formation and habit development, university students are highly malleable and therefore an appropriate priority for environmental interventions [3].

In the field of environmental behaviour research, organisational citizenship behaviour for the environment (OCBE) pertains to voluntary and discretionary actions undertaken by individuals to support environmental initiatives within an organisation, exceeding their formal role responsibilities [4] (p. 7450), [5] (pp. 353–371). The concept has, in recent years, been increasingly applied to higher education settings to explain students’ green engagement on campus [6] (p. 3634). Among students, OCBE typically manifests in self-initiated green practices driven by intrinsic values—such as turning off classroom electricity after use, participating in environmental clubs, or promoting low-carbon lifestyles. Existing research on student OCBE has primarily examined the direct effects of factors such as ecological cognition and pro-environmental attitudes, while offering limited exploration of how situational incentives may activate psychological mechanisms that drive OCBE [7].

Online environmental gamification—an incentive-based behavioural intervention that integrates elements such as task design, instant feedback and social interaction—has, in recent years, attracted growing scholarly attention for its potential to stimulate public pro-environmental behaviours [8] (p. 87). Some studies have examined its use in particular environmental contexts, such as resource conservation and waste sorting, with empirical results providing initial evidence of positive impacts on ecological awareness, behavioural intention, and actual performance [9] (p. 10400). However, a significant portion of the existing research has concentrated on areas such as education or health-related behaviours, with limited systematic examination of the applicability and effectiveness of gamification as an incentive mechanism within environmental education contexts [10] (p. 80). Furthermore, current scholarship on gamification and pro-environmental behaviour tends to follow two relatively distinct research trajectories—one emphasising behavioural incentive mechanisms and the other environmental psychological processes—yet rarely adopts a cross-domain integrative perspective [11] (pp. 1510–1549). To address these gaps, this study asks: Does online environmental gamification promote university students’ OCBE, and if so, through which cognitive and affective mechanisms does this occur?

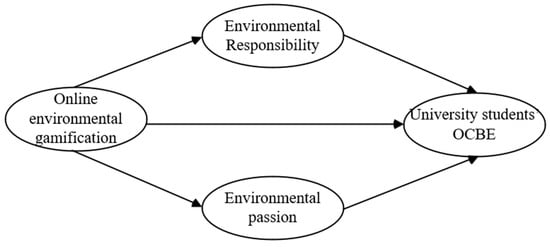

To answer these questions, the study draws on the Cognitive Affective Personality System (CAPS) theory [12] (p. 246) to develop a dual-mediation model explaining how online environmental gamification stimulates students’ OCBE. CAPS theory posits that individual behaviour arises from the joint activation of cognitive and affective units within specific situational contexts [12] (p. 246). In an online environmental gamification setting, rich gamified elements—such as instant feedback and social interaction—can enhance environmental cognition, heighten sensitivity to environmental issues and strengthen a sense of responsibility, thereby fostering environmental responsibility. At the same time, the sense of achievement and belonging derived from gamification can elicit positive emotions, triggering environmental passion and strengthening the willingness and persistence to engage in green behaviours [10] (p. 80). Under the combined influence of these cognitive and affective pathways, students are more likely to demonstrate proactive, role-exceeding OCBE within the campus environment [7].

This study offers three main contributions. First, it extends the contextual boundaries of antecedent research on university students’ OCBE. Second, it identifies the dual mediating roles of environmental responsibility and environmental passion, thereby clarifying the underlying mechanisms through which online environmental gamification influences OCBE. Third, it advances CAPS theory by extending its application from traditional organisational behaviour research to the domain of digital ecological behaviour. Practically, the findings provide both theoretical foundations and actionable insights for universities aiming to implement digital green education programmes, as well as empirical guidance for online platforms seeking to design green action projects with more substantial behavioural incentive effects.

2. Theoretical Background and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Online Environmental Gamification

By embedding points, badges and leaderboards in environmental tasks, gamification heightens interactivity and engagement. A behavioural intervention mechanism that enhances individual emotional engagement and behavioural participation in green action (Ouariachi et al., 2020) [13]. Relative to conventional tools, gamified designs foreground enjoyment and social interaction, thereby lowering entry barriers and supporting sustained, self-directed participation [13] (p. 4565). Existing research indicates that gamified experiences characterised by feelings of accomplishment and interactivity can evoke positive emotions, enjoyment, and a heightened sense of environmental responsibility. Such experiences have been shown to significantly predict voluntary green behaviours and prosocial actions [14] (pp. 371–380), [15] (pp. 160–169).

Ant Forest, launched by Alipay in 2016, is China’s most representative “personal carbon account” and a widely adopted online environmental gamification platform. Through the mechanism of “accumulating green energy from low-carbon behaviours—virtual tree growth—offline tree planting” [16], it embeds core gamification elements such as point accumulation, progress feedback, social interaction, cooperative tasks, and leaderboard competition into daily life [17] (p. 30). When users collect sufficient energy, partner organisations plant corresponding real trees in ecological conservation areas and provide digital records. With over 700 million participants, the platform has become an influential model of public environmental engagement. Prior studies show that this “virtual-to-real transformation” enhances the visibility and perceived impact of environmental actions [18] (p. 1741) and strengthens intrinsic motivation by elevating responsibility awareness and emotional involvement [19] (p. 4791), [20] (pp. 1–21). Given its extensive user base, clear behavioural transformation pathway, and typical gamified design, Ant Forest offers a highly representative context for examining how online environmental gamification shapes individual pro-environmental behaviour.

2.2. Online Environmental Gamification and OCBE

OCBE denotes voluntary, beyond-role efforts that advance an organisation’s environmental aims—for example, resource saving, advocacy, and volunteering [21] (pp. 431–445). In recent years, the concept of OCBE has been increasingly utilised in higher education settings to explain university students’ environmentally friendly practices within the campus environment [7]. University students are at a formative stage in the development of values and behavioural habits—making their pro-environmental actions more malleable and susceptible to the influence of intrinsic motivation and psychological identification [22] (pp. 97–100).

CAPS holds that situations co-activate cognitive and affective units to shape behaviour, beyond any stable dispositional tendencies [12] (p. 246). Ant Forest combines points, virtual trees and “green energy” so that pro-environmental actions become salient and intrinsically engaging [23] (p. 2213). Real-time feedback makes progress visible, reinforces satisfaction, and sustains participation [24]. Peer-based interaction and norms foster a pro-engagement climate that further nudges green behaviours [25]. These contextual features, through the synergy of cognitive processing and emotional experience, jointly enhance individual environmental behaviour levels [26] (p. 13253).

Accumulating evidence shows that gamified settings raise environmental awareness, intentions, and actual behaviours [13] (p. 4565), [23] (p. 2213), [27] (p. 512). For example, Ouariachi, Li and Elving [13] found that contextual incentives and gamification mechanisms can effectively enhance public engagement and sustainability in environmental behaviour; Sun and Xing [27] found that Ant Forest effectively stimulated users’ motivation to engage in green consumption through gamification mechanisms, thereby enhancing their environmental behaviour performance; Wang and Yao [23] emphasized through empirical analysis that well-designed gamification elements, such as points, virtual trees, and leaderboards, play a significant role in stimulating individual environmental Behaviour and fostering long-term green habits. Building on this, the paper proposes the following hypotheses:

H1.

Online environmental gamification is positively associated with students’ OCBE.

2.3. The Mediating Role of Environmental Responsibility

Environmental responsibility reflects a felt obligation to protect the environment and an internalised commitment to act on it [28] (pp. 407–424). The concept originates from the Norm Activation Model (NAM) within social psychology. This highlights that when a person recognises the environmental impact of their actions and feels responsible, their internal personal norms are stirred, leading to related behavioural tendencies [29] (pp. 221–279). In recent years, environmental responsibility has been extensively studied in empirical research within the field of environmental behaviour, and related studies have demonstrated that it has significant positive predictive effects on various pro-environmental actions such as green consumption, energy conservation and emission reduction, and environmental initiatives [30], (p. 2456, [31]). In the context of higher education, the sense of environmental responsibility among college students is typically manifested as concern for campus environmental problems, sensitivity to the consequences of environmental actions, and the recognition of responsibility for improving environmental conditions [32].

According to the cognitional-affective personality system theory [12] (p. 246), the use of Ant Forest can activate and strengthen users’ environmental responsibility through cognitive pathways. First, Ant Forest enhances users’ awareness of the severity and urgency of environmental issues through task design and environmental knowledge quizzes, helps establish a causal relationship between ecological behaviour and environmental protection, and thereby strengthens responsibility awareness [23] (p. 2213). Secondly, visual feedback on platform emissions reduction and tree planting transforms abstract environmental achievements into concrete ones, enhancing users’ sense of responsibility and belonging [17] (p. 30). Finally, the social sharing function reinforces the internalisation process of responsibility, enabling users to demonstrate their environmental contributions while also taking on the social responsibility of spreading environmental concepts to others, thereby transforming external environmental requirements into internal moral obligations [33] (pp. 8314–8342).

After the sense of environmental responsibility is effectively stimulated, its driving effect on individual environmental behaviour gradually emerges. Based on the cognition-affective Personality System (CAPS) theory, ecological responsibility as a Cognitive structure can influence an individual’s interpretation and response to environmental situations. When individuals have a strong sense of responsibility, they are more likely to identify ecological opportunities, positively evaluate the significance of ecological behaviour, and thus exhibit more environmental organisational citizenship behaviour beyond role requirements (OCBE). The formation of this cognitive bias and behavioural tendency reflects the guiding role of cognitive units on behaviour in CAPS theory. In addition, the existing empirical evidence in the academic community also provides relevant empirical evidence. Zeng et al. [19] (p. 4791) pointed out that environmental responsibility significantly predicts the performance of individuals in pro-environmental behaviours such as resource conservation and green consumption. Gulliver et al. [34] found that highly responsible individuals were significantly more involved in environmental advocacy and volunteer services. Building on this, the paper presents the following hypothesis:

H2.

Environmental responsibility transmits the effect of gamification to students’ OCBE.

2.4. The Mediating Role of Environmental Passion

Environmental passion describes sustained positive affect coupled with enthusiastic involvement in environmental activities [35] (pp. 18–29). This concept emphasises the emotional connection and psychological excitement of the target behaviour in the process of environmental protection behaviour, which is an essential emotional resource for stimulating the motivation of environmental behaviour [36] (p. 14747). In recent years, Environmental passion has been extensively used in pro-environmental behaviour research. Empirical studies have found that it can significantly enhance the level of individual participation in various environmental behaviours such as environmental advocacy, resource conservation, and environmental volunteer actions [36] (p. 14747), [37] (p. 567). In the college context, college students’ environmental enthusiasm is typically manifested as emotional engagement in environmental activities, interest in environmental issues, and willingness to participate in environmental actions on campus [38] (p.985).

Based on the theory of the cognitively affective personality system [12] (p. 246), specific contextual stimuli can effectively activate an individual’s emotional units and enhance their emotional experience and emotional motivation levels. First, the gamification design of Ant Forest (such as points achievements, badges, leaderboards) transforms dull environmental behaviours into enjoyable game activities, providing users with pleasant and immersive environmental experiences that stimulate their interest and emotional engagement [39] (p. 3197). Secondly, the platform provides users with various achievement-based rewards, displayed as badges on the “My Achievements” interface. These badges visually communicate the attainment of personal goals, eliciting a strong sense of pride and accomplishment and further reinforcing the emotional motivation that drives pro-environmental behaviour [18] (p. 1741). Again, social features (such as friend interaction and sharing of ecological achievements) add the social dimension of environmental passion, allowing users to experience a sense of belonging and emotional resonance in their interactions with others [40] (p. 4305). Finally, the platform gives users an intuitive understanding of the actual environmental impact of their ecological protection actions by presenting the results of tree planting and the progress of desertification control. This perception of meaning further inspires users’ passion for environmental protection [41].

Drawing on the Cognitive-Affective Personality System (CAPS) theory, environmental passion can be understood as a type of positive emotion that is triggered by the activation of emotional units. Once activated, these units influence how individuals perceive and interpret their emotional experiences, thereby exerting a significant impact on their subsequent behavioural preferences and choices [12] (p. 246). When individuals have a high level of environmental passion, they are more likely to experience emotional resonance and value recognition in ecological situations, thereby demonstrating sustained enthusiasm for action and environmental behaviour beyond role requirements. In addition, the existing empirical evidence in the academic field also provides relevant empirical evidence. Shah, Fahlevi, Rahman, Akram, Jamshed, Aljuaid and Abbas [36] found that environmental passion can enhance an individual’s willingness to act and motivation to participate, enhancing their propensity to actively and consistently participate in environmentally friendly practices. Russell and Ashkanasy [42] pointed out that the positive emotion-driven effect helps to reduce behavioural delay and increase the speed and persistence of behavioural execution. Saifulina et al. [20] (pp. 1–21) further demonstrated that high levels of environmental passion significantly predict individual performance in transpersonal behaviours such as environmental advocacy, resource conservation, and volunteering. Based on this, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

H3.

Environmental passion acts as an intermediary through which gamification relates to OCBE.

The theoretical framework of this study is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework.

3. Method

3.1. Sample

Participants were recruited on Credamo, which allows criterion-based sampling and quality screens to ensure dependable data [43] (p. 1277829). Participants were drawn from five universities in East China. University students were chosen as the target group because, as active users of digital platforms, they tend to show a high level of participation in online environmental gamification activities. In addition, being at a formative stage of value development, they are more responsive to external situational stimuli. The specific features of this population indicate that it is highly consistent with the assumptions of the theoretical framework and the operational variables employed in this study, thereby enhancing the appropriateness and validity of the research design.

In order to mitigate potential issues related to common method bias, the data collection process was deliberately designed to unfold in three separate waves across a period of 56 days. This time-lagged approach not only reduced the likelihood of inflated correlations but also strengthened the robustness of the findings. Furthermore, prior to filling out each questionnaire, participants were explicitly reminded that their responses would remain completely anonymous and strictly confidential, thereby minimising social desirability bias and encouraging more authentic, candid answers. Unique IDs enabled online administration, restricted later waves to Wave-1 respondents, and ensured longitudinal matching. To this end, we distributed 600 questionnaires to university students through the Credamo platform. After completing the three-wave survey, we removed respondents who did not continue into Waves 2 or 3, as well as cases that could not be longitudinally matched due to unmatched unique identification codes, resulting in 428 participants who successfully completed all three waves (effective response rate = 71.3%). We then applied pre-established quality control criteria to ensure data validity and the reliability of subsequent analyses. Specifically, questionnaires with response times falling within the top or bottom 5% of the overall distribution were excluded to avoid biases arising from inattentive or interrupted responses, and cases with substantial missing data on core variables (Ant Forest Usage, environmental responsibility, environmental passion, and OCBE) were treated as invalid. Following these procedures, a final dataset of 333 respondents with complete and high-quality three-wave data was obtained. Among the final sample, 56.3% were female; 83.7% were undergraduates; 47.2% studied in the humanities and social sciences, while 52.8% in science and engineering disciplines.

3.2. Measures

All measurement scales used in this study have been validated in prior research by both domestic and international scholars. All items used seven-point Likert anchors (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). As all latent variables in this study were measured using established scales whose items represent manifestations of the underlying constructs, each construct was modelled as a reflective measurement.

3.2.1. Ant Forest Usage

The measurement of this construct adopted a four-point scale created by Ren [44] based on Hu [45], with sample items such as “By playing the Ant Forest game, I have satisfied my entertainment needs.” In this study, the scale’s Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was found to be 0.774.

3.2.2. Environmental Responsibility

The variable was measured using a scale (Stone et al., 1995) [46] (pp. 595–612), such as “I have a responsibility to do my best to save resources and protect the environment”. In this study, the Cronbach’s α value of the scale was 0.710.

3.2.3. Environmental Passion

The scale developed by Robertson and Barling [47]. The original scale consists of three dimensions and 10 items, covering environmental commitment, environmental fun, and environmental enthusiasm. To enhance the contextual suitability of the scale for this study, a pre-test and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were conducted. The results showed that three items—“At my university, I am confident in my environmental values,” “At my university, I am proud to contribute to improving the environment” and “At my university, I enjoy implementing environmental behaviours”—had factor loadings below 0.50, failing to meet the required measurement threshold. Moreover, these items exhibited clear social desirability bias in the pre-test, as students tended to provide morally normative responses, which weakened the scale’s ability to capture true variance. Accordingly, the three items were removed, and seven items were retained for measurement. The full list of measurement items is provided in the Supplementary Materials. The Cronbach’s α value of the scale was 0.847 in this study.

3.2.4. Organizational Citizenship Behaviour for the Environment

The variable was assessed using a 10-item scale created by Boiral and Paillé [21], including: “I weigh whether my behaviour is beneficial to environmental protection before engaging in an activity”, etc. The CFA results indicated that the item “In my daily life, I voluntarily engage in environmentally friendly behaviours and measures.” exhibited a substantially low factor loading (<0.50). To enhance the contextual suitability of the scale for this study, this item was removed, and nine items were ultimately retained for measurement. The Cronbach’s α value of the scale was 0.860 in this study.

3.2.5. Control Variables

Prior research has indicated that demographic variables can influence individuals’ environmental behaviours [48] (pp. 613–627). Accordingly, gender, year of study, and level of education were included as control variables in the present study.

3.3. Data Analysis Strategy

Regarding model estimation, this study employed Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE), which is appropriate for continuous variables under the assumption of multivariate normality and is widely used in AMOS for confirmatory factor analysis and structural path estimation, thereby ensuring the robustness and validity of model estimation. First, AMOS 24 was used to conduct confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess the discriminant validity of the four core constructs—AFU, ER, EP, and OCBE. Second, IBM SPSS Statistics 27 was used to compute descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations, and to perform bivariate correlations and regression analyses. Finally, mediation effects were tested using PROCESS 3.3 in SPSS.

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

CFA was used to evaluate the latent structure and discriminant validity of the focal constructs. Table 1 reports fit indices for the four-factor model (χ2/df = 1.942; RMSEA = 0.053; CFI = 0.918; TLI = 0.908; SRMR = 0.055), which indicate acceptable fit [49] (pp. 1–55). This model outperformed all alternative models, suggesting satisfactory discriminant validity among the core constructs.

Table 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis (N = 333).

To assess the discriminant validity of the constructs, the Fornell–Larcker criterion was further applied. In Table 2, the diagonal values represent the square roots of each construct’s AVE, and the off-diagonal values indicate the inter-construct correlations. The results show that most constructs met the criterion that the AVE square root exceeds their correlations with other constructs. However, a few correlations slightly exceeded their respective AVE square roots, suggesting potential conceptual proximity between certain construct pairs. Nonetheless, prior research has noted that when constructs are highly correlated, the Fornell–Larcker criterion may lack sufficient sensitivity and may fail to reliably detect issues of discriminant validity [50] (pp. 115–135).

Table 2.

Fornell–Larcker Criterion for Discriminant Validity (N = 333).

In light of these considerations, the Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) was subsequently employed as an additional criterion to further verify the discriminant validity among the constructs. HTMT reflects the degree of similarity between latent constructs, and values below 0.85 are generally regarded as indicative of adequate discriminant validity [50] (pp. 115–135). As shown in Table 3, all HTMT values among the constructs were well below the 0.85 threshold, indicating the absence of high inter-construct correlations or conceptual overlap. These results provide strong support for the discriminant validity of the latent variables.

Table 3.

HTMT discriminant validity results (N = 333).

4.2. Common Method Bias Analysis

A Harman single-factor check extracted four factors, with the first accounting for 32.65% of variance—below the conventional 40% heuristic—thus indicating that common method bias is unlikely to be a dominant threat to inference [51] (p. 879). In addition, a model incorporating a common method factor was constructed to further examine the presence of common method bias. A comparison between the four-factor model and the common method factor model yielded the following differences in key fit indices: ∆χ2/df = 0.371, ∆CFI = 0.037, ∆TLI = 0.036, and ∆RMSEA = 0.012. The changes in CFI and TLI were all below the conventional 0.10 threshold, and the change in RMSEA did not exceed 0.05. These results indicate that adding a common method factor did not produce any meaningful improvement in model fit, suggesting that common method bias is unlikely to be a serious concern in this study.

4.3. Analysis of Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 4 summarises descriptive statistics and correlations. The results show that Ant Forest use is significantly and positively correlated with environmental responsibility (r = 0.234, p < 0.01), environmental passion (r = 0.348, p < 0.01), and OCBE (r = 0.339, p < 0.01). Both environmental responsibility (r = 0.401, p < 0.01) and environmental passion (r = 0.665, p < 0.01) are also significantly and positively correlated with OCBE. These findings align with our expectations and bolster subsequent hypothesis testing. In addition, VIF values were modest (max = 1.560), indicating negligible multicollinearity.

Table 4.

Means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients of the variables (N = 333).

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

All regression results are reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

Hierarchical Regression Analysis Results.

H1 posited that online environmental gamification (measured by Ant Forest use) positively influences university students’ OCBE. Regression estimates (Model 2) show a positive association between Ant Forest use and OCBE (β = 0.340, p < 0.001), consistent with H1. Therefore, H1 is supported.

H2 posited that environmental responsibility mediates the relationship between online environmental gamification and OCBE. As shown in Model M6, Ant Forest use has a substantial positive impact on ecological responsibility (β = 0.224, p < 0.001). Model M3 further demonstrates that environmental responsibility significantly affects OCBE (β = 0.336, p < 0.001). After introducing the mediator, the direct impact of Ant Forest use on OCBE decreased from 0.340 in Model M2 to 0.265 in Model M3; the coefficient attenuation after introducing environmental responsibility indicates partial mediation. To further validate this conclusion, the bias-corrected bootstrap method proposed by Preacher and Hayes [52] was employed to estimate the 95% confidence intervals. The results showed that the indirect effect of environmental responsibility was 0.0868, with a 95% CI = [0.0397, 0.1474] > 0, indicating a significant mediation effect. Moreover, after controlling for the mediator, the direct effect of Ant Forest use remained significant (direct effect = 0.3054, 95% CI = [0.1927, 0.4181]), thereby providing empirical support for Hypothesis 2.

H3 posited that environmental passion mediates the relationship between Ant Forest use and OCBE. As shown in Model M5, Ant Forest use has a significant positive effect on ecological passion (β = 0.349, p < 0.001). Model M4 further indicates that environmental passion significantly influences OCBE (β = 0.614, p < 0.001). Following the introduction of the mediator, the direct impact of Ant Forest use on OCBE decreased from 0.340 in Model M2 to 0.122 in Model M4, introducing environmental passion substantially reduced the direct path, consistent with partial mediation. In the bootstrap analysis, the indirect effect of environmental passion was found to be significant (indirect effect = 0.2471, 95% CI = [0.1652, 0.3394] > 0). Moreover, the direct effect of Ant Forest use remained significant after controlling for the mediator (direct effect = 0.1452, 95% CI = [0.0045, 0.2454] > 0). These results provide empirical support for Hypothesis 3.

5. Discussion

Drawing on three-wave survey data and structural equation modelling, this study provides strong evidence supporting the core hypotheses: online environmental gamification significantly enhances university students’ pro-environmental organisational citizenship behaviour (OCBE) and operates through dual mediation via environmental responsibility and environmental passion.

Our conclusions align with and extend existing research on OCBE and gamification effects. On the one hand, the study corroborates the link between digital situational incentives and pro-environmental behaviour—a relationship previously established mainly among organisational employees or within traditional public-welfare contexts [53] (pp. 899–930), [54] (p. 1097655) and demonstrates that this mechanism likewise holds for university students. On the other hand, prior gamification research has tended to focus on the behavioural effectiveness of design elements [55] (pp. 14–31), [56] (pp. 3025–3034) while paying comparatively limited attention to the deeper psychological mechanisms that drive these effects. In contrast to interview-based studies on Ant Forest [16] which largely emphasise emotional experience and symbolic public-welfare cues, our findings indicate that responsibility cognition developed through structured digital tasks constitutes an equally important driver of green behaviour, suggesting that gamification effects rest on a multidimensional psychological foundation.

With regard to mechanism analysis, this study builds upon and extends existing theoretical frameworks. Prior research has argued that the behavioural impact of gamification stems from its activation of users’ psychological needs and perceived fulfilment [14] (pp. 371–380), [57] (p. 111544). Building on discussions such as [58] (p. 121038) concerning how Ant Forest technologies promote sustainable engagement, the present study further examines the psychological pathways through which digital green incentive mechanisms operate among university students. The results show that design features centred on public-welfare goals and virtual tree planting strengthen users’ cognitive sense of environmental responsibility, consistent with Shuang Chen’s [6] (p. 3634) findings that gamification enhances value cognition. At the same time, echoing Necati Taşkın’s [59] (pp. 3334–3345) analysis of gamification-induced emotional arousal, we find that similar affective processes contribute to university students’ environmental behaviour. Taken together, these results validate the synergistic roles of responsibility and environmental passion, demonstrating that environmental gamification promotes OCBE through the coordinated activation of cognitive and affective mechanisms. This deepens our understanding of how digital green incentives shape sustainable behaviour within structured platform environments.

6. Conclusions

Grounded in CAPS, we analysed 428 three-wave responses using a dual-mediation design to trace how gamification relates to OCBE. The findings confirmed the positive effect of Ant Forest use on OCBE. They elucidated its dual cognitive affective mediation pathways, thereby making an essential contribution to both the theoretical understanding and the practical application of gamified environmental platforms.

Online environmental gamification relates to OCBE both directly and via environmental responsibility and passion, delineating a cognitive affective pathway from digital experiences to real-world action. These findings expand the application of the Cognitive-Affective Personality System (CAPS) theory to the realm of digital pro-environmental behaviour, establishing a theoretical mechanism for transferring digital environmental experiences into real-world ecological actions. They also offer a scientific foundation for designing gamified environmental platforms, innovating ecological education, and developing environmental policies.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

First, this study broadens the theoretical perspective on the antecedents of pro-environmental organisational citizenship behaviour (OCBE). By introducing online environmental gamification as a situational, incentive-based intervention, it reveals how such gamified experiences foster OCBE by stimulating students’ environmental responsibility and environmental passion. This theoretical extension enriches the dimensionality of OCBE antecedents and expands the contextual boundaries within which OCBE can be understood, thereby offering new conceptual leverage for future research on how situational incentives drive pro-environmental organisational citizenship behaviour.

Second, we explicate the mechanism: effects travel through parallel cognitive and affective routes. Based on a dual-mediation pathway, it demonstrates that online environmental gamification positively influences college students’ OCBE by activating cognitive processing through ecological responsibility and emotional experience through environmental passion. This finding moves beyond the limitations of prior research that has predominantly emphasised the external incentive effects of gamification, highlighting instead the critical role of psychological mechanisms in linking situational incentives to pro-environmental behaviour. It thus offers a new perspective for exploring the intrinsic connections between digital platform interventions and environmental behaviour.

Third, situating CAPS in a platform context clarifies how coordinated cognitive affective activation connects digital cues to OCBE. It reveals the psychological pathway through which online environmental gamification influences OCBE via the coordinated activation of cognitive and affective units. This extension represents an essential shift of the CAPS framework from traditional organisational behaviour research to the domain of digital pro-environmental behaviour, enriching its explanatory power in elucidating the collaborative mechanisms between complex digital platform interventions and environmental behaviour.

6.2. Practical Implications

Universities can deploy gamified environments to directly enhance students’ OCBE. Universities should systematically integrate online environmental gamification mechanisms into their environmental education and behavioural intervention systems, leveraging digital situational incentives to strengthen students’ capacity for green action. Specific measures include integrating online environmental platforms with course instruction and extracurricular activities, using task design, instant feedback and points-based incentives to help students embed green behaviours into daily life. Universities may also leverage social features—such as team competitions, online challenges and leaderboards—to encourage collective participation and sustain engagement. To enhance systematisation and operability, institutions can establish a unified green points system linking classroom performance and energy-saving behaviours with campus app scores, and implement quantitative evaluation mechanisms such as “green dormitories” and “green classes” to create a data-driven feedback loop connecting online gamification with real-world green actions.

Second, because environmental responsibility mediates the relationship between online environmental gamification and students’ OCBE, university administrators can implement responsibility-enhancing initiatives. These may include incorporating a “personal carbon account” into the campus app to display each student’s contribution to overall campus carbon reduction; organising role-play tasks—such as acting as environmental managers or campus energy monitors—to strengthen students’ sense of role responsibility; and establishing a “responsibility reflection log” that encourages students to record daily carbon reductions, energy savings, and the motivations underlying their environmental actions, thereby further promoting voluntary green engagement.

Third, because environmental passion mediates the relationship between online environmental gamification and students’ OCBE, universities should prioritise the design of emotionally engaging experiences that make environmental actions more enjoyable and affectively involving. Examples include gamifying tasks through “environmental challenge” activities—such as energy-saving check-ins, recycling missions, or plant adoption; incorporating “environmental achievement badges” into the campus app to enhance students’ sense of accomplishment; and organising environmental storytelling sessions or short-video contests to strengthen emotional resonance and participation enthusiasm, thereby further encouraging the development of pro-environmental organisational citizenship behaviours.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Although this study clarifies the internal mechanisms through which online environmental gamification influences college students’ organisational citizenship behaviour for the environment (OCBE) via dual cognitive affective pathways, and provides valuable insights for promoting green education practices in universities, some limitations remain, particularly regarding research design and scope, which should be addressed and refined in future studies.

First, this study relies on self-reported questionnaire data and focuses primarily on university students in China, which introduces certain limitations in both cultural context and behavioural setting. Although the three-wave, time-lagged design helps mitigate common method bias and social desirability effects, the inherent nature of self-reported measures may still lead to subjective inflation of one’s behaviour or affective states as well as socially desirable responding. Future research could integrate objective behavioural indicators—such as backend behavioural logs from Ant Forest or other environmental platforms, or platform-level energy consumption data—with self-reported measures to enhance behavioural authenticity and measurement robustness. In addition, cross-contextual comparisons across different cultural or educational settings would be valuable for examining the generalisability and external validity of online environmental gamification mechanisms in predicting OCBE.

Second, this study primarily examines the positive effects of online environmental gamification on pro-environmental behaviour, while empirical testing of its potential negative effects remains limited. Prior research suggests that gamification may induce risks such as “moral licensing,” superficial motivation driven by excessive reliance on external rewards, and digital fatigue resulting from prolonged use. As these potential drawbacks were not empirically assessed in the present study, future research should further examine the boundary conditions and possible countereffects of gamification incentives across different contexts to develop a more comprehensive understanding of their dual impact on environmental behaviour.

Third, this study presents several limitations in research design and methodology. The analysis focuses on the dual mediation mechanism of online environmental gamification and does not systematically incorporate potential moderating factors—such as campus green policies, peer norms, or the intensity of social media interaction—which may reduce the model’s sensitivity to contextual variation and constrain its external validity. In addition, the study relies primarily on quantitative questionnaires and structural equation modelling, which, while effective in identifying statistical associations, offer limited insight into students’ psychological experiences and behavioural formation processes during gamified engagement. The absence of qualitative interviews, process tracing, or mixed-methods approaches restricts the depth and dynamic explanatory power of the proposed mechanisms. Future research could incorporate institutional contextual factors or individual-difference variables as moderators to clarify the boundary conditions of gamification effects, and employ interviews, digital behavioural data, experimental paradigms, or cross-scenario comparisons to more comprehensively capture the micro-level psychological mechanisms and behavioural change processes underlying gamification incentives.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172411038/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.H. (Zhiyong Han); Methodology, Z.H. (Zhiyong Han); Software, J.H.; Validation, Z.H. (Ziwei Huang); Investigation, J.H.; Resources, Z.H. (Ziwei Huang); Data curation, Z.H. (Zhiyong Han); Writing—original draft, J.H. and Z.H. (Zhiyong Han); Writing—review & editing, Z.H. (Ziwei Huang) and Z.H. (Zhiyong Han); Supervision, Z.H. (Ziwei Huang); Project administration, Z.H. (Ziwei Huang) and Z.H. (Zhiyong Han); Funding acquisition, Z.H. (Ziwei Huang). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the General Program of the Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation [Grant number 202302a04020062] and the Key Project of Scientific Research in Universities of Anhui Province [Grant number 2023AH050263].

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Academic Research Ethics Committee of the School of Business Administration, Anhui University of Finance and Economics on 2 July 2025. No formal approval code was assigned.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhou, Y.; Gu, B. The impacts of human activities on Earth Critical Zone. Earth Crit. Zone 2024, 1, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliu, O.; Sarumi, O. The Role of Circular Economy in Achieving Sustainability: A Case Study of Songhai Integrated Farming Initiatives. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Manag. 2025, 5, 931–941. [Google Scholar]

- Mabkhot, H.; Semlali, Y.; Gelaidan, H.M.; Abdelwahed, N.A.A.; Shaari, H. Unveiling Green Entrepreneurial Intentions and Behaviour Among Saudi Arabian Youth: Insights and Implications. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Sun, H.; Li, Q. The effect of self-sacrificial leadership on employees’ organisational citizenship behaviour for the environment: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahar, N.e.; Zawawi, D.; Jaharuddin, N.S.; Abbasi, M.A. Responsible leadership and organisational citizenship behaviour for the environment: Mediated by environmental corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2025, 41, 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Yan, X.; Liew, C.-B.A. University social responsibility in China: The mediating role of green psychological capital. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Jiang, C.; Li, J. Stimulating Chinese college students’ organizational citizenship behavior toward the environment: The role of pro-environmental organizational climate, green self-efficacy and intrinsic motivation. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, B.; Vishnupriya, V.; Arjunan, P.; Dhariwal, J. Net-zero energy campuses in India: Blending education and governance for sustainable and just transition. Sustainability 2024, 16, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boncu, Ș.; Candel, O.-S.; Popa, N.L. Gameful green: A systematic review on the use of serious computer games and gamified mobile apps to foster pro-environmental information, attitudes and behaviors. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, Y.; Hadjichambis, A.C.; Paraskeva-Hadjichambi, D.; Adamou, A. “From gamers into environmental citizens”: A systematic literature review of empirical research on behavior change games for environmental citizenship. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2023, 7, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Das, M.; Sharma, W.; Verma, A.; Kumra, R. Gamification for sustainable consumption: A state-of-the-art overview and future agenda. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 1510–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischel, W.; Shoda, Y. A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: Reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychol. Rev. 1995, 102, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouariachi, T.; Li, C.-Y.; Elving, W.J. Gamification approaches for education and engagement on pro-environmental behaviors: Searching for best practices. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailer, M.; Hense, J.U.; Mayr, S.K.; Mandl, H. How gamification motivates: An experimental study of the effects of specific game design elements on psychological need satisfaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jiang, X.; Cao, Y.; Ding, Z. Research on the influence of green gamification design on the pro-environmental behavior of the young generation. Coal Econ. Res. 2025, 45, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L. Research on the Nudging Mechanism of Gamification Design Boosting Youths’ Participation in Public Welfare Activities: A Case Study of Ant Forest. Master’s Thesis, Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics, Nanchang, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Cai, D. Ant forest through the haze: A case study of gamified participatory pro-environmental communication in China. J 2019, 2, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Z. From Virtual Trees to Real Forests: Public Participation in Virtual Forest Realization Projects in China. Forests 2024, 15, 1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Zhong, W.; Naz, S. Can environmental knowledge and risk perception make a difference? The role of environmental concern and pro-environmental behavior in fostering sustainable consumption behavior. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifulina, N.; Carballo-Penela, A.; Ruzo-Sanmartin, E. Harmonious environmental passion and voluntary pro-environmental behavior at home and at work: A moderated mediation model to examine the role of cultural femininity. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O.; Paillé, P. Organizational citizenship behaviour for the environment: Measurement and validation. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, E.; Krulj, J.; Lazović, N.; Simijonović, I. Educational and psychological aspects of developing of ecological identity. Sci. Int. J. 2024, 3, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yao, X. Fueling pro-environmental behaviors with gamification design: Identifying key elements in ant forest with the kano model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisurina, A. Gamifying Sustainability: Motivating Pro-Environmental Behavior Change Through Gamification. Case of JouleBug. Master’s Thesis, Lappeenranta University of Technology, Lappeenranta, Finland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Behroozi, A. Promoting Pro-Environmental Behavior for Sustainable Water Resource Management: A Social Exchange Perspective. In Promoting Pro-Environmental Behavior for Sustainable Water Resource Management: A Social Exchange Perspective; Qeios: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Si, W.; Jiang, C.; Meng, L. The relationship between environmental awareness, habitat quality, and community residents’ pro-environmental behavior—Mediated effects model analysis based on social capital. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Xing, J. The impact of gamification motivation on green consumption behavior—An empirical study based on ant forest. Sustainability 2022, 15, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative influences on altruism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1977; Volume 10, pp. 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorenza, M. Psychological Drivers of Environmental Action: From Attitudes and Identity to Readiness to Change. 2025. Available online: https://flore.unifi.it/handle/2158/1420792 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Vedantam, A.; Suresh, N.C.; Ajmal, K.; Shelly, M. Impact of China’s National Sword Policy on the U.S. Landfill and Plastics Recycling Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchiroyan, Z. Improving Energy Efficiency at CSUN Through Data-Driven HVAC Optimization. Ph.D. Thesis, California State University, Northridge, CA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wittayakom, S. Gamification Strategies to Enhance Environmental Awareness in Sustainable Retail: A Systematic Literature Review. Pak. J. Life Soc. Sci. (PJLSS) 2025, 23, 8314–8342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliver, R.E.; Fielding, K.S.; Louis, W.R. An investigation of factors influencing environmental volunteering leadership and participation behaviors. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2023, 52, 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gousse-Lessard, A.-S.; Vallerand, R.J.; Carbonneau, N.; Lafrenière, M.-A.K. The role of passion in mainstream and radical behaviors: A look at environmental activism. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 35, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.H.A.; Fahlevi, M.; Rahman, E.Z.; Akram, M.; Jamshed, K.; Aljuaid, M.; Abbas, J. Impact of green servant leadership in Pakistani small and medium enterprises: Bridging pro-environmental behaviour through environmental passion and climate for green creativity. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Li, J. Understanding the impact of environmentally specific servant leadership on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors in the workplace: Based on the proactive motivation model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Song, H.-D.; Hong, A.J. Exploring factors, and indicators for measuring students’ sustainable engagement in e-learning. Sustainability 2019, 11, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo, C.; Zanchetta, C.; Goldmann, E.; de Carvalho, C.V. The use of gamification and web-based apps for sustainability education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Long, R.; Wu, F. How symbols and social interaction influence the experienced utility of sustainable lifestyle guiding policies: Evidence from eastern China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J. The Motivations of Users to Participate in Sustainable Projects on Mobile Applications: The Case of Antforest. Master’s Thesis, Norwegian School of Economics, Bergen, Norway, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, S.V.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Pulling on heartstrings: Three studies of the effectiveness of emotionally framed communication to encourage workplace pro-environmental behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Yu, G. The nudging effect of AIGC labeling on users’ perceptions of automated news: Evidence from EEG. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1277829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X. From virtual to real media mobilization: An investigation into the impact of new media product usage on college students’ pro-environmental behavioral intentions. New Media Res. 2021, 7, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, X. Gamification strategies of environmental communication in the Internet age: A case study of “Ant Forest”. J. Lover 2018, 2018, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, G.; Barnes, J.H.; Montgomery, C. Ecoscale: A scale for the measurement of environmentally responsible consumers. Psychol. Mark. 1995, 12, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Barling, J. Greening organizations through leaders’ influence on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, J.; Shen, J.; Deng, X. Effects of green HRM practices on employee workplace green behavior: The role of psychological green climate and employee green values. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-t.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankelová, N.; Némethová, I.; Dabić, M.; Kallmuenzer, A. Enhancing organizational citizenship behavior towards the environment. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2025, 19, 899–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yu, X. Green transformational leadership and employee organizational citizenship behavior for the environment in the manufacturing industry: A social information processing perspective. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1097655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaborn, K.; Fels, D.I. Gamification in theory and action: A survey. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2015, 74, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Koivisto, J.; Sarsa, H. Does gamification work?—A literature review of empirical studies on gamification. In Proceedings of the 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2014; pp. 3025–3034. [Google Scholar]

- Mi, L.; Xu, T.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, J.; Lv, T.; Gan, X.; Shang, K.; Qiao, L. Playing Ant Forest to promote online green behavior: A new perspective on uses and gratifications. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 278, 111544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obuobi, B.; Tang, D.; Awuah, F.; Nketiah, E.; Adu-Gyamfi, G. Utilizing Ant Forest technology to foster sustainable behaviors: A novel approach towards environmental conservation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 359, 121038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taşkın, N.; Kılıç Çakmak, E. Effects of gamification on behavioral and cognitive engagement of students in the online learning environment. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2023, 39, 3334–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).