Identification of Organizational Efficiency Profiles Based on Human Capital Management: A Study Using Principal Component Analysis and Clustering Algorithms

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Conceptual Foundations of Organizational Efficiency

1.2. Human Capital and Organizational Efficiency

1.3. Competencies, Leadership, and Organizational Climate

1.4. Multivariate Approaches in the Study of Efficiency

1.5. Conceptual Synthesis

1.6. Sectoral Context: The Ecuadorian Banana Export Industry

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Approach

2.2. Population, Sample, and Research Context

2.3. Instrument and Analytical Variable

2.4. Analytical Procedure

2.4.1. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

2.4.2. Cluster Analysis

Evaluation of Clustering Quality

- Hierarchical phase. An ascending dendrogram in which the progressive fusions reveal the similarities among individuals and the overall pattern of homogeneity.

- Non-hierarchical phase. A factorial plane (PCA Component 1 × Component 2) where individuals appear grouped around centroids, and the distance between clusters reflects structural differences in the profiles of organizational efficiency.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

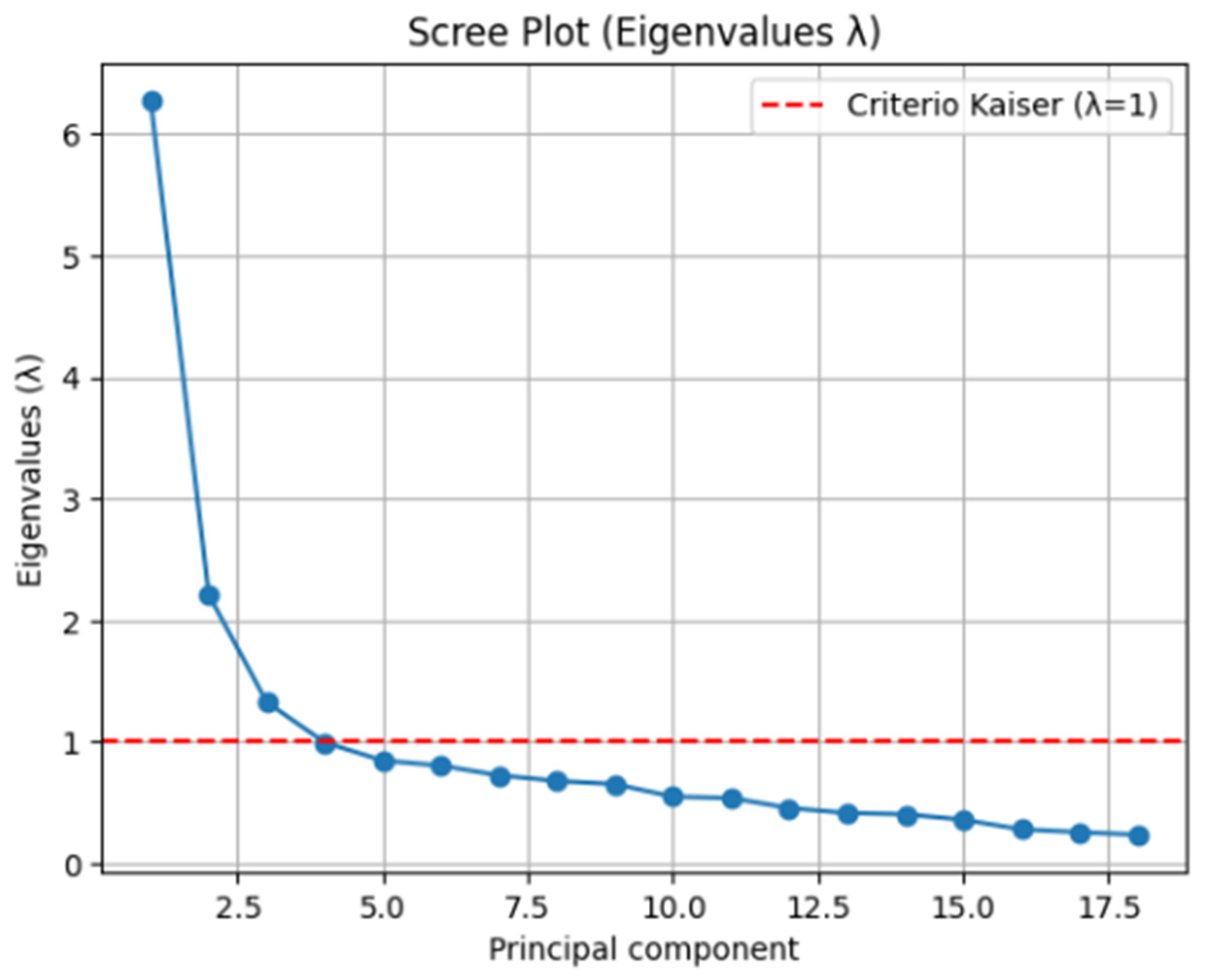

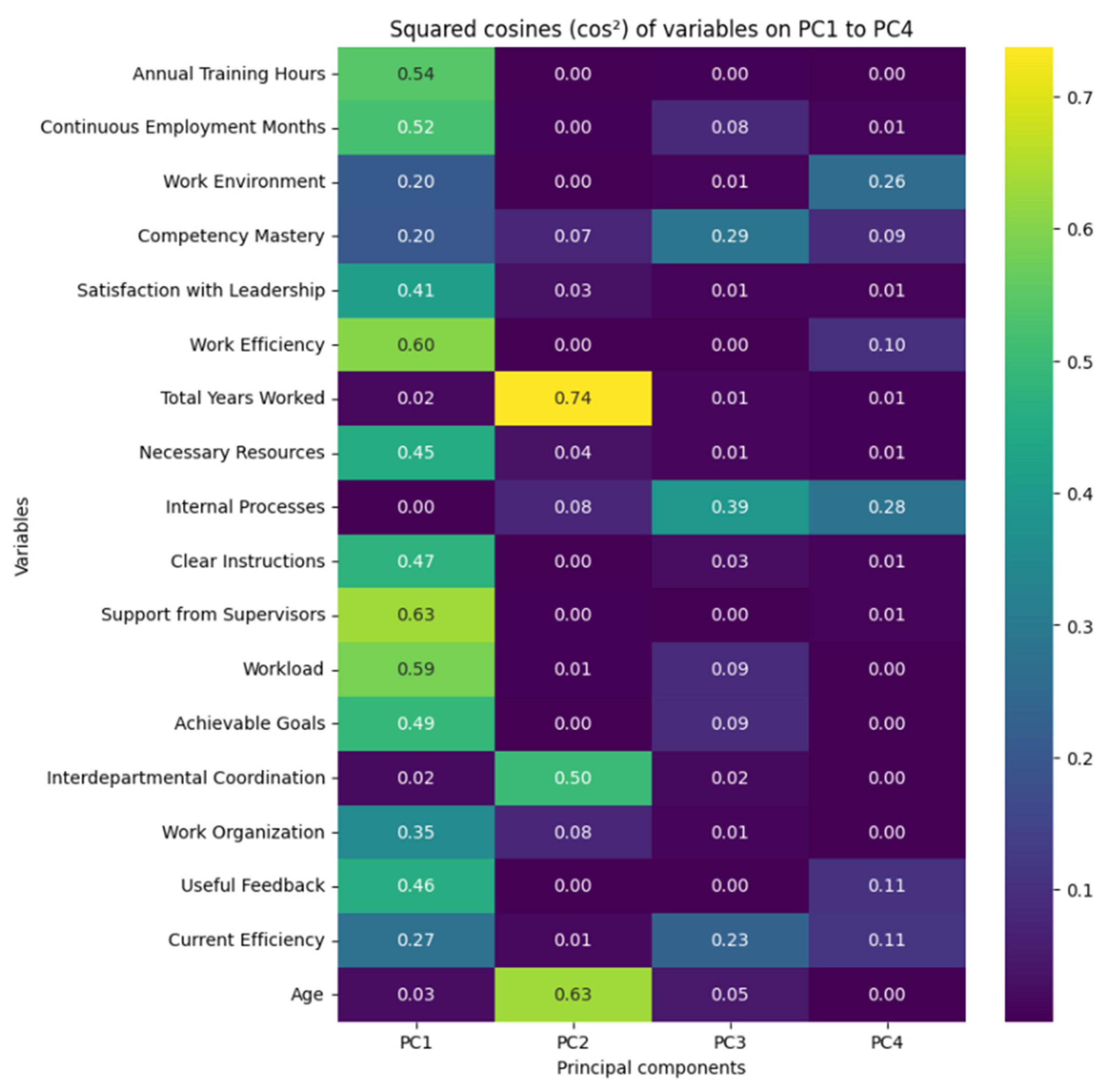

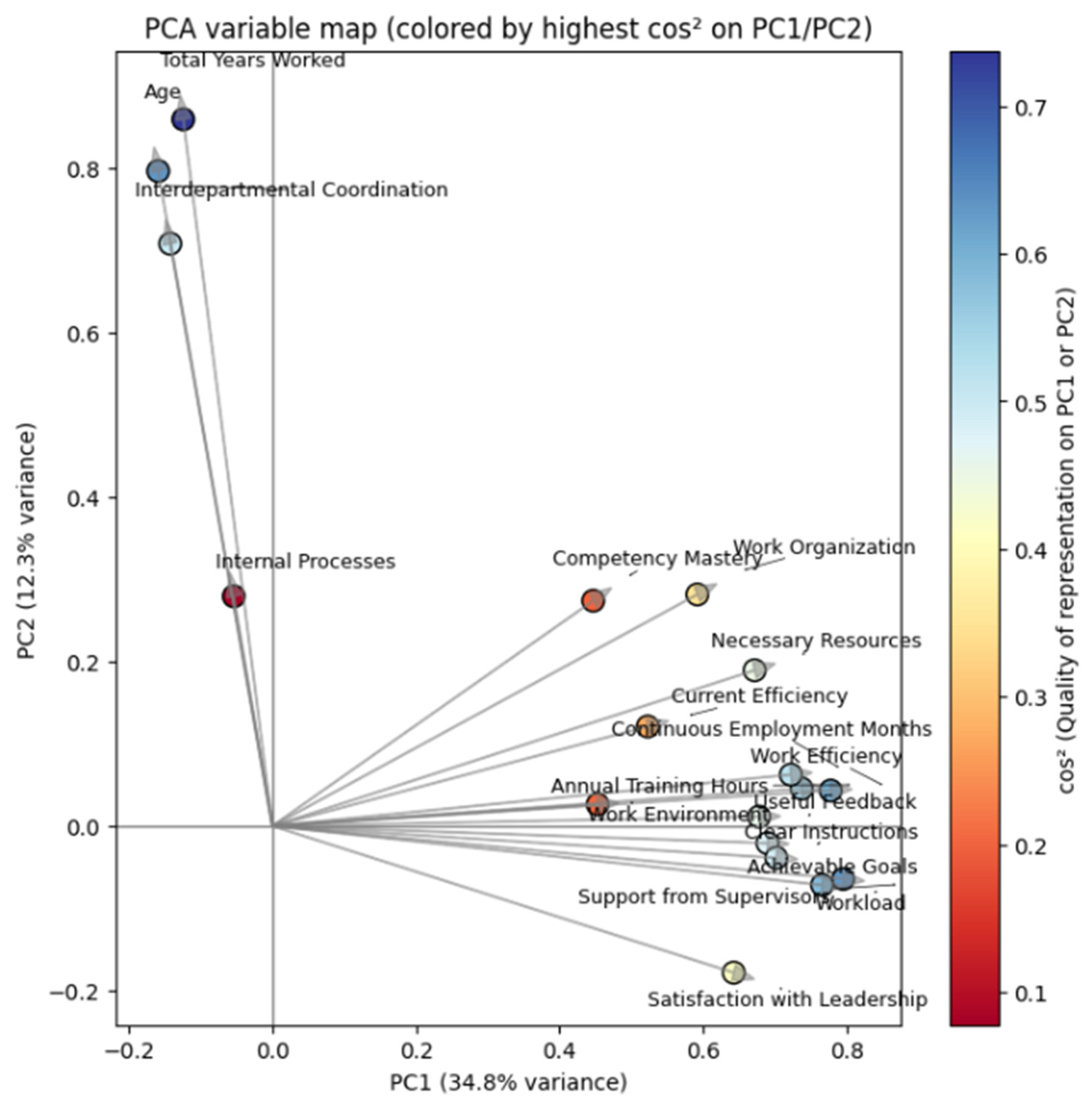

3.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

3.3. Identification of Profiles Through Clustering Algorithms

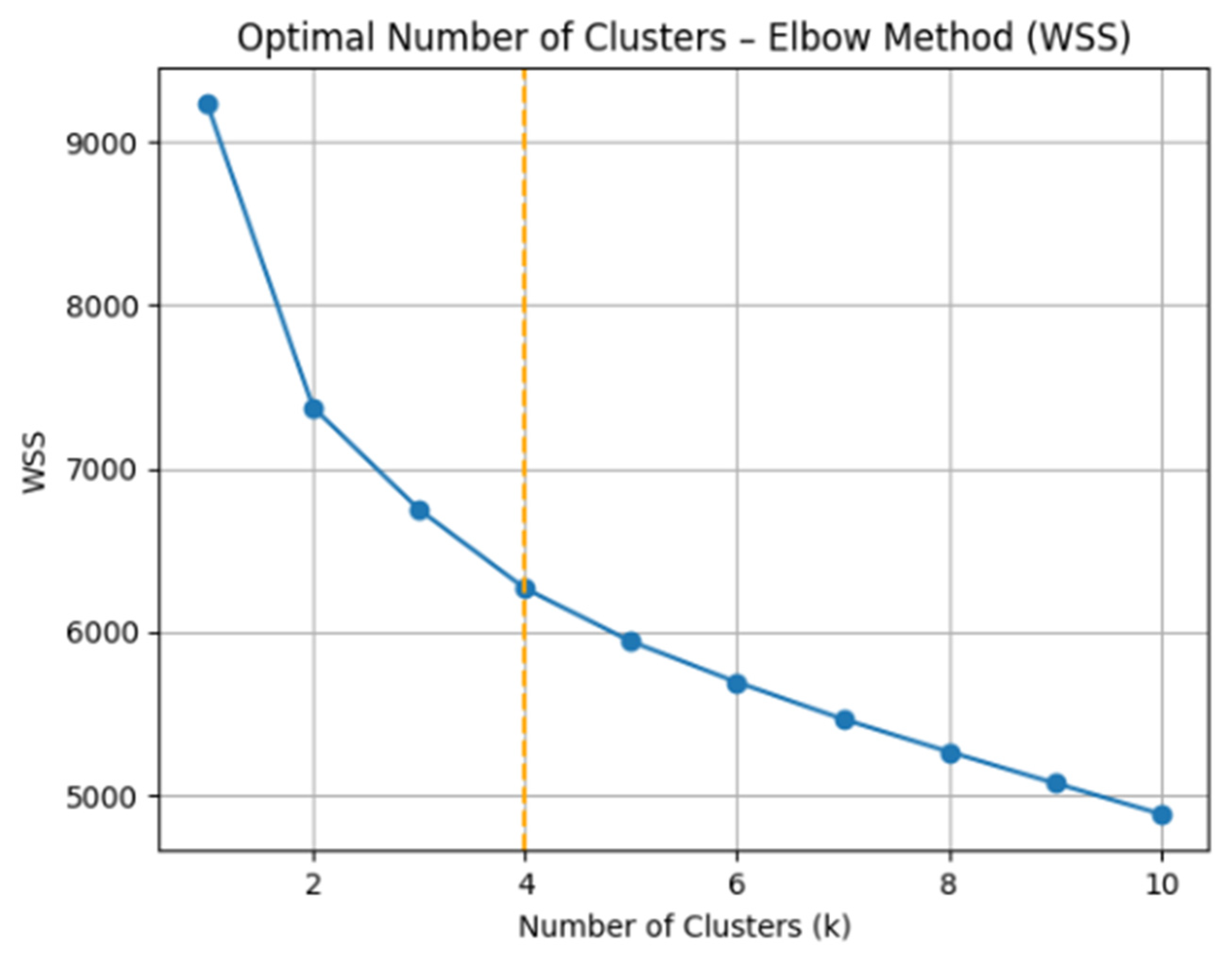

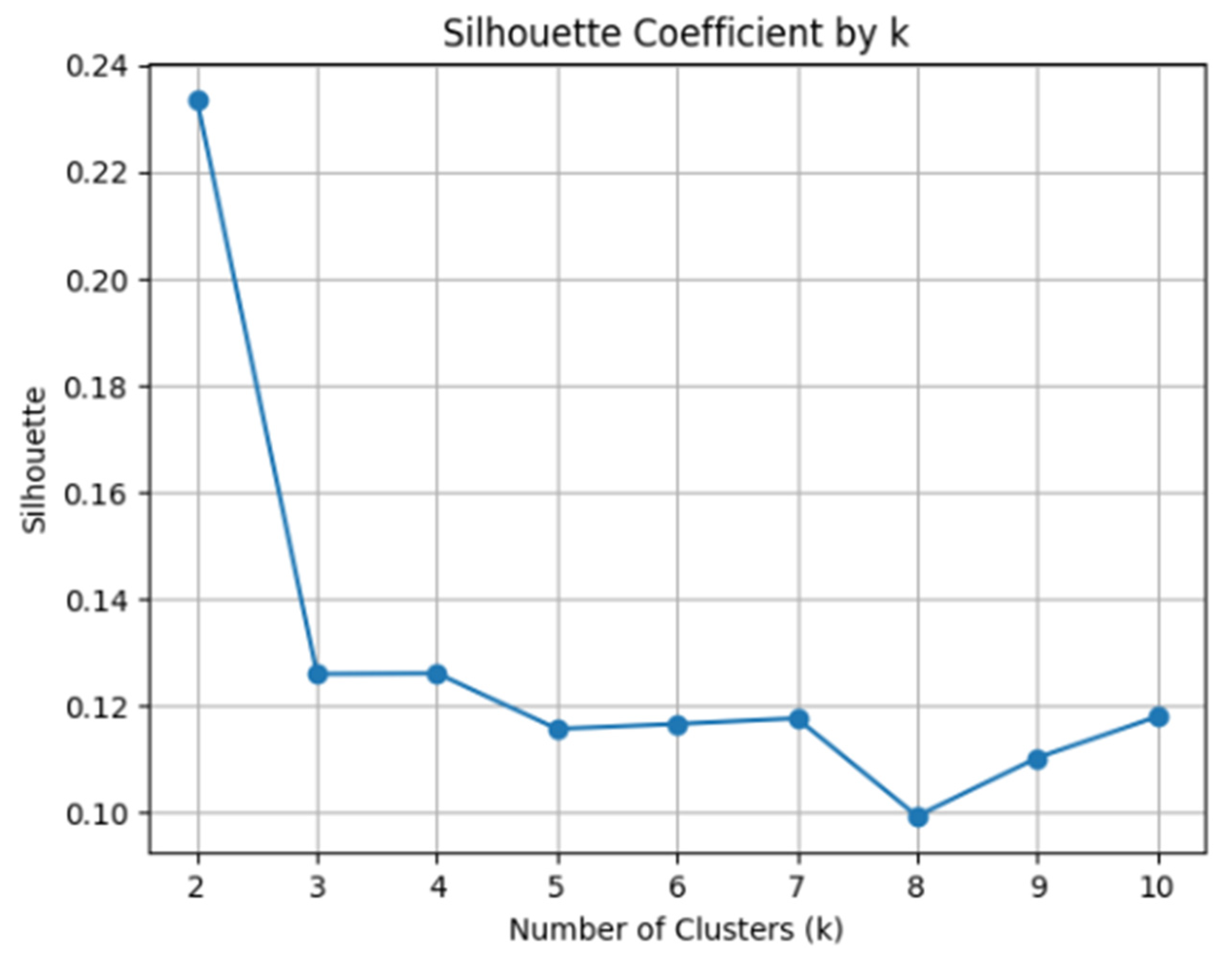

3.3.1. Selection of the Number of Clusters

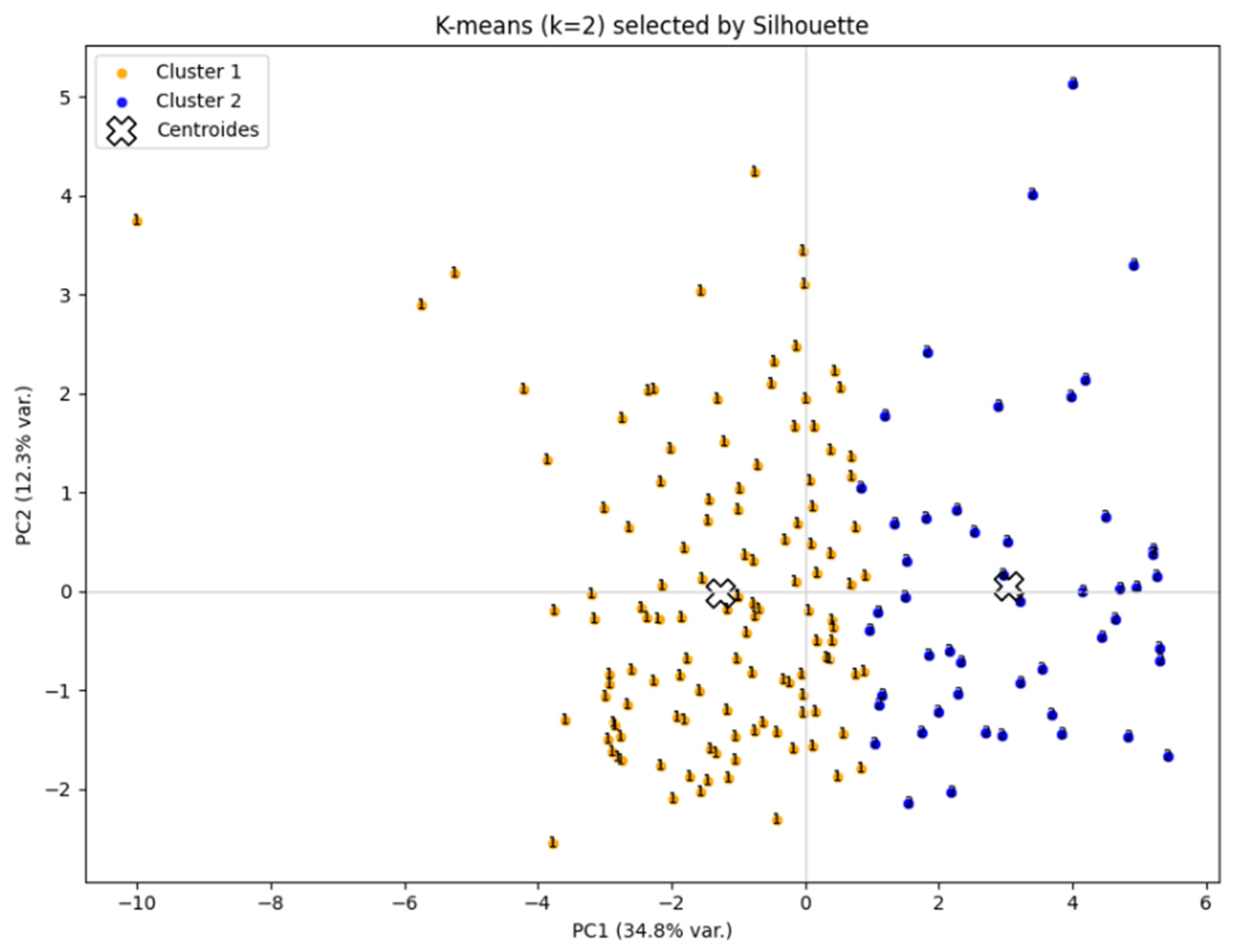

3.3.2. Main Partition (K-means, k = 2)

- Profile 1: Low Specific/Support (PC1 < 0). Workers with lower values in annual training hours and months of continuous employment (specific human capital), as well as relatively lower perceptions of supervisory support, clear instructions, achievable goals, feedback, resources, and work organization. By construction of the PCA, these individuals are expected to show lower scores in work efficiency, and, through PC3, more moderate levels of current efficiency.

- Profile 2: High Specific/Support (PC1 > 0). This group concentrates workers with greater tenure and internal training, together with stronger micro-organizational conditions (support, resources, and work organization). The deployment of firm-specific human capital in this cluster is associated with higher perceived efficiency and stronger applied competencies (PC3), thus anticipating higher current performance.

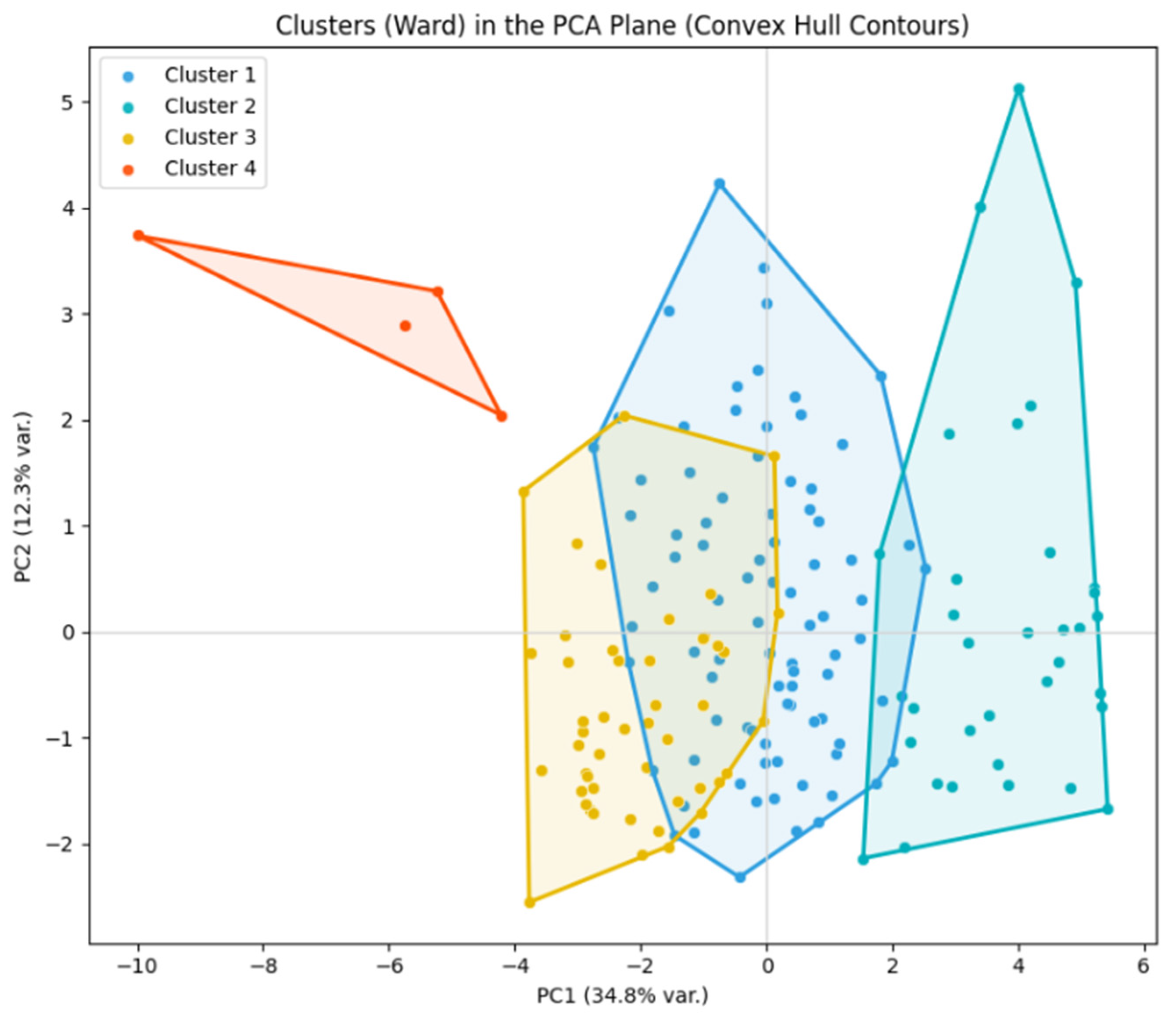

3.3.3. Complementary Partition (Ward, k = 4)

- C1—High PC1, Medium PC2 (“Specific Deployment with Support”). Strong combination of tenure and training with solid supervisory and organizational support; candidates for sustained high performance.

- C2—High PC1, High PC2 (“Coordinating Maturity”). In addition to specific deployment, this cluster highlights seniority/age and interdepartmental coordination; represents bridging profiles between functional units.

- C3—Low PC1, Medium PC2 (“Operation by Individual Effort”). Lower levels of support and process standardization; efficiency depends primarily on personal effort rather than structured processes.

- C4—Low PC1, High PC2 (“Isolated Seniority”, small group). High experience/age combined with limited specific support; at risk of inefficiencies unless training and job conditions are strengthened.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. Banana Market Review: Preliminary Results 2024; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giermindl, L.M.; Strich, F.; Christ, O.; Leicht-Deobald, U.; Redzepi, A. The dark sides of people analytics: Reviewing the perils for organisations and employees. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2022, 31, 410–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minbaeva, D.B. Building credible human capital analytics for organizational competitive advantage. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Liu, A.; Chen, G. High performance work systems and corporate performance: The influence of entrepreneurial orientation and organizational learning. Front. Bus. Res. China 2018, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fegade, T.K.; Sharma, P. Exploring the impact of employee training and development on organizational efficiency: A systematic literature review. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2023, 25, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Crook, T.R.; Todd, S.Y.; Combs, J.G.; Woehr, D.J.; Ketchen, D.J., Jr. Does human capital matter? A meta-analysis of the relationship between human capital and firm performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coolen, P.; Van den Heuvel, S.; Van de Voorde, K.; Paauwe, J. Understanding the adoption and institutionalization of workforce analytics: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2023, 33, 100985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, C.; Den Hartog, D.N.; Lepak, D.P. A systematic review of human resource management systems and their measurement. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 2498–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafie, M.R.; Khosravi, H.; Farhadpour, S.; Das, S. A cluster-based human resources analytics for predicting employee turnover using optimized artificial neural networks and data augmentation. Decis. Anal. J. 2024, 11, 100461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binanto, I.; Tumanggor, A. Comparison of the K-Means method with and without Principal Component Analysis (PCA) in predicting employee resignation. In E3S Web of Conferences, Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Applied Sciences and Smart Technologies, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 18–19 October 2023; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2024; Volume 475, p. 02009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamanlı, A.İ.; Balcıoğlu, Y.S. Human Capital Deployment and Organizational Efficiency: A Cross-National Benchmarking Analysis of Global Workforce Distribution Patterns. Int. J. Account. Econ. Stud. 2025, 12, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Saavedra, M.; Vallejos, M.; Huancahuire-Vega, S.; Morales-García, W.C.; Geraldo-Campos, L.A. Work Team Effectiveness: Importance of Organizational Culture, Work Climate, Leadership, Creative Synergy, and Emotional Intelligence in University Employees. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, N.K. The impact of leadership competences, organizational culture and performance. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2022, 28, 1391–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jung, H.-S. The effect of employee competency and organizational culture on employees’ perceived stress for better workplace. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jooss, S.; Collings, D.G.; McMackin, J.; Dickmann, M. A skills-matching perspective on talent management: Developing strategic agility. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 63, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravariti, F.; Tasoulis, K.; Scullion, H.; Alali, M.K. Talent management and performance in the public sector: The role of organisational and line managerial support for development. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 34, 1782–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education, 3rd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lazear, E.P. Firm-Specific Human Capital: A Skill-Weights Approach. J. Political Econ. 2009, 117, 914–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, D. Industry-specific human capital: Evidence from displaced workers. J. Labor Econ. 1995, 13, 653–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, N.W.; Dyer, J.H. Human capital and learning as a source of sustainable competitive advantage. Strateg. Manag. J. 2004, 25, 1155–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichniowski, C.; Shaw, K.; Prennushi, G. The effects of human resource management practices on productivity: A study of steel finishing lines. Am. Econ. Rev. 1997, 87, 291–313. [Google Scholar]

- Hitka, M.; Kucharčíková, A.; Štarchoň, P.; Balážová, Ž.; Lukáč, M.; Stacho, Z. Knowledge and Human Capital as Sustainable Competitive Advantage in Human Resource Management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendickson, J.; Gur, F.A.; Taylor, E.C. Reducing environmental uncertainty: How high performance work systems moderate the resource dependence–firm performance relationship. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2018, 35, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappi, E. New hires, adjustment costs, and knowledge transfer—Evidence from the mobility of entrepreneurs and skills on firm productivity. Ind. Corp. Change 2024, 33, 712–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A.; Mano, Y.; Abebe, G. Earnings, savings, and job satisfaction in a labor-intensive export sector: Evidence from the cut flower industry in Ethiopia. World Dev. 2018, 110, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garavan, T.N.; McCarthy, A.; Lai, Y.; Murphy, K.; Sheehan, M.; Carbery, R. Training and organisational performance: A meta-analysis of temporal, institutional and organisational context moderators. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2021, 31, 93–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osagie, E.R.; Wesselink, R.; Blok, V.; Mulder, M. Learning organization for corporate social responsibility implementation: Unravelling the intricate relationship between organisational and operational LO characteristics. Organ. Environ. 2022, 35, 130–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campion, M.A.; Fink, A.A.; Ruggeberg, B.J.; Carr, L.; Phillips, G.M.; Odman, R.B. Doing competencies well: Best practices in competency modeling. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 225–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J.I.; Levine, E.L. What is (or should be) the difference between competency modeling and traditional job analysis? Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2009, 19, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Dansereau, F. Are transformational leaders fair? A multi-level study of transformational leadership, justice perceptions, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.; Ehrhart, M.G.; Macey, W.H. Organizational climate and culture. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013, 64, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berberoglu, A. Impact of organizational climate on organizational commitment and perceived organizational performance: Empirical evidence from public hospitals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Takeuchi, R.; Lepak, D.P. Where do we go from here? New perspectives on the black box in strategic human resource management research. J. Manag. Stud. 2013, 50, 1448–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieranoja, S.; Fränti, P. Adapting k-means for graph clustering. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2022, 64, 115–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikotun, A.M.; Ezugwu, A.E.; Abualigah, L.; Abuhaija, B.; Heming, J. K-means clustering algorithms: A comprehensive review, variants analysis, and advances in the era of big data. Inf. Sci. 2023, 622, 178–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 9th ed.; Cengage Learning: Andover, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: A review and recent developments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliński, T.; Harabasz, J. A dendrite method for cluster analysis. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 1974, 3, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marler, J.H.; Boudreau, J.W. An evidence-based review of HR analytics. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, S.; Annosi, M.C.; Marchegiani, L.; Messeni Petruzzelli, A. Digital technologies and knowledge processes: New emerging strategies in international business. J. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 27, 330–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellström, D.; Holtström, J.; Berg, E.; Josefsson, C. Dynamic capabilities for digital transformation. J. Strategy Manag. 2022, 15, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiyegunhi, L.J.S. Examining the impact of human capital and innovation on farm productivity in the KwaZulu-Natal North Coast, South Africa. Agrekon 2024, 63, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.B.M.; Godinho Filho, M.; Fredendall, L.D.; Gómez Paredes, F.J. Lean, Six Sigma and Lean Six Sigma in the food industry: A systematic literature review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 82, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boon, A.; Sandström, C.; Rose, D.C. Governing agricultural innovation: A comprehensive framework to underpin sustainable transitions. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 89, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description | Scale |

|---|---|---|

| General Human Capital | ||

| Total Years Worked | Total years of work experience accumulated throughout the employee’s career. | Number of years working |

| Age | Employee’s age (related to job maturity and knowledge accumulation). | Employee’s age |

| Specific Human Capital | ||

| Annual Training Hours | Participation in training programs organized by the company during the last year. | Number of training hours received in the last year |

| Continuous Employment Months | Specific tenure within the organization. | Number of months employed in the company |

| Competency Mastery | Level of mastery of the technical and soft skills required for the position. | Likert scale: 1 (very low)–5 (very high) |

| Organizational Conditions | ||

| Work Environment | Perception of the work environment and workplace relationships. | Likert scale: 1 (very unsatisfactory)–5 (very satisfactory) |

| Satisfaction with Leadership | Evaluation of immediate leadership. | Likert scale: 1 (very unsatisfactory)–5 (very satisfactory) |

| Support from Supervisors | Degree of support received from supervisors and coordinators. | Likert scale: 1 (strongly disagree)–5 (strongly agree) |

| Interdepartmental Coordination | Quality of collaboration across departments. | Likert scale: 1 (strongly disagree)–5 (strongly agree) |

| Necessary Resources | Availability of tools and materials required for work. | Likert scale: 1 (strongly disagree)–5 (strongly agree) |

| Structural Processes | ||

| Internal Processes | Level of standardization and clarity in organizational processes. | Likert scale: 1 (strongly disagree)–5 (strongly agree) |

| Clear Instructions | Precision and clarity of the directives received. | Likert scale: 1 (strongly disagree)–5 (strongly agree) |

| Achievable Goals | Planning and realism of operational objectives. | Likert scale: 1 (strongly disagree)–5 (strongly agree) |

| Workload | Volume of assigned tasks and work–life balance. | Likert scale: 1 (strongly disagree)–5 (strongly agree) |

| Work Organization | Structure and distribution of job functions. | Likert scale: 1 (strongly disagree)–5 (strongly agree) |

| Useful Feedback | Quality of feedback received to improve performance. | Likert scale: 1 (strongly disagree)–5 (strongly agree) |

| Work Efficiency | Perception of the degree of efficiency with which the employee meets objectives and goals within their work area. | Likert scale: 1 (very low)–5 (very high) |

| Current Efficiency | Ability to work efficiently given the company’s current conditions. | Likert scale: 1 (strongly disagree)–5 (strongly agree) |

| Variables | Count | Media | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual Training Hours | 513 | 58.18 | 44.71 | 5 | 276 |

| Continuous Employment Months | 513 | 42.41 | 44.05 | 0 | 250 |

| Work Environment | 513 | 3.46 | 1.14 | 1 | 5 |

| Competency Mastery | 513 | 3.92 | 0.7 | 2 | 5 |

| Satisfaction with Leadership | 513 | 3.88 | 0.88 | 1 | 5 |

| Work Efficiency | 513 | 3.85 | 0.84 | 1 | 5 |

| Total Years Worked | 513 | 12.53 | 8.21 | 1 | 35 |

| Necessary Resources | 513 | 3.77 | 0.89 | 1 | 5 |

| Internal Processes | 513 | 3.9 | 0.8 | 1 | 5 |

| Clear Instructions | 513 | 3.89 | 0.81 | 1 | 5 |

| Support from Supervisors | 513 | 3.87 | 0.79 | 1 | 5 |

| Workload | 513 | 3.78 | 0.78 | 1 | 5 |

| Achievable Goals | 513 | 3.88 | 0.84 | 1 | 5 |

| Interdepartmental Coordination | 513 | 3.8 | 0.84 | 1 | 5 |

| Work Organization | 513 | 3.96 | 0.75 | 1 | 5 |

| Useful Feedback | 513 | 3.85 | 0.8 | 1 | 5 |

| Current Efficiency | 513 | 3.87 | 0.77 | 1 | 5 |

| Age | 513 | 36.37 | 8.64 | 21 | 65 |

| Component | Eigenvalue (λ) | Explained Variance | Cumulative Variance |

|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | 6.2755 | 0.3480 | 0.3480 |

| PC2 | 2.2096 | 0.1225 | 0.4705 |

| PC3 | 1.3274 | 0.0736 | 0.5441 |

| PC4 | 0.9972 | 0.0553 | 0.5994 |

| PC5 | 0.8487 | 0.0471 | 0.6464 |

| PC6 | 0.8067 | 0.0447 | 0.6912 |

| PC7 | 0.7267 | 0.0403 | 0.7314 |

| PC8 | 0.6803 | 0.0377 | 0.7692 |

| PC9 | 0.6541 | 0.0363 | 0.8054 |

| PC10 | 0.5518 | 0.0306 | 0.8360 |

| PC11 | 0.5389 | 0.0299 | 0.8659 |

| PC12 | 0.4576 | 0.0254 | 0.8913 |

| PC13 | 0.4158 | 0.0231 | 0.9143 |

| PC14 | 0.4060 | 0.0225 | 0.9368 |

| PC15 | 0.3614 | 0.0200 | 0.9569 |

| PC16 | 0.2820 | 0.0156 | 0.9725 |

| PC17 | 0.2584 | 0.0143 | 0.9869 |

| PC18 | 0.2371 | 0.0131 | 1.0000 |

| Componentes | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Cont | cos2 | CF | Contb | cos2 | CF | Cont | cos2 | CF | Cont | cos2 | CF |

| Support from Supervisors | 0.101 | 0.980 | 0.795 | |||||||||

| Work Efficiency | 0.096 | 0.848 | 0.778 | 0.104 | 0.146 | 0.322 | ||||||

| Workload | 0.093 | 0.863 | 0.766 | 0.066 | 0.128 | 0.295 | ||||||

| Annual Training Hours | 0.087 | 0.989 | 0.737 | |||||||||

| Continuous Employment Months | 0.083 | 0.845 | 0.722 | |||||||||

| Total Years Worked | 0.334 | 0.955 | 0.859 | |||||||||

| Age | 0.287 | 0.897 | 0.797 | |||||||||

| Interdepartmental Coordination | 0.227 | 0.928 | 0.708 | |||||||||

| Work Organization | 0.036 | 0.179 | 0.282 | |||||||||

| Internal Processes | 0.035 | 0.104 | 0.279 | 0.295 | 0.521 | 0.626 | 0.281 | 0.372 | 0.529 | |||

| Competency Mastery | 0.217 | 0.441 | 0.537 | |||||||||

| Current Efficiency | 0.175 | 0.366 | 0.483 | 0.115 | 0.181 | 0.339 | ||||||

| Achievable Goals | 0.068 | 0.154 | 0.300 | |||||||||

| Work Environment | 0.259 | 0.548 | 0.508 | |||||||||

| Useful Feedback | 0.107 | 0.188 | 0.327 | |||||||||

| Number of Clusters (k) | Silhouette Score |

|---|---|

| 2 | 0.2087 |

| 3 | 0.1367 |

| 4 | 0.1317 |

| 5 | 0.1318 |

| 6 | 0.1339 |

| 7 | 0.1323 |

| Problem Domain | Main Problems Identified | Strategic Goals | Illustrative Managerial Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human capital management practices | Limited formalisation of HR procedures; weak recruitment and selection criteria; insufficient investment in training and development. | To professionalise human resource management and ensure that HR practices support organisational efficiency. | Design and implement formal recruitment and selection processes; establish clear job descriptions; create annual training plans focused on critical skills. |

| Organisational climate and leadership | Low levels of participation and communication; limited feedback; leadership styles not fully aligned with collaboration and learning. | To foster an organisational climate that supports commitment, communication and collaborative problem-solving. | Introduce regular team meetings and feedback mechanisms; develop leadership training programmes; promote participatory decision-making practices. |

| Competencies and productivity | Gaps in technical and soft skills; difficulties in adapting to new technologies and standards; heterogeneous performance across teams. | To strengthen individual and collective competencies linked to productivity and quality requirements. | Implement targeted upskilling and reskilling initiatives; link performance evaluation to development plans; provide on-the-job coaching and mentoring. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Serrano-Orellana, B.; Lalangui Ramírez, J.I.; Gutiérrez Jaramillo, N.D.; Rodríguez-Jaramillo, L.; Lara-Guamán, J. Identification of Organizational Efficiency Profiles Based on Human Capital Management: A Study Using Principal Component Analysis and Clustering Algorithms. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11037. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411037

Serrano-Orellana B, Lalangui Ramírez JI, Gutiérrez Jaramillo ND, Rodríguez-Jaramillo L, Lara-Guamán J. Identification of Organizational Efficiency Profiles Based on Human Capital Management: A Study Using Principal Component Analysis and Clustering Algorithms. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11037. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411037

Chicago/Turabian StyleSerrano-Orellana, Bill, Jessica Ivonne Lalangui Ramírez, Néstor Daniel Gutiérrez Jaramillo, Lia Rodríguez-Jaramillo, and Johanna Lara-Guamán. 2025. "Identification of Organizational Efficiency Profiles Based on Human Capital Management: A Study Using Principal Component Analysis and Clustering Algorithms" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11037. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411037

APA StyleSerrano-Orellana, B., Lalangui Ramírez, J. I., Gutiérrez Jaramillo, N. D., Rodríguez-Jaramillo, L., & Lara-Guamán, J. (2025). Identification of Organizational Efficiency Profiles Based on Human Capital Management: A Study Using Principal Component Analysis and Clustering Algorithms. Sustainability, 17(24), 11037. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411037