Individual Behavior or Collective Phenomenon: Peer Effects in the Coordinated Intelligentization and Greenization of Chinese Manufacturing Firms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Peer Effects in the Coordinated Development of Intelligentization and Greenization: Basic Hypotheses

2.2. Peer Effects in the Coordinated Development of Enterprise Intelligentization and Greenization: Formation Mechanisms

3. Research Design

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

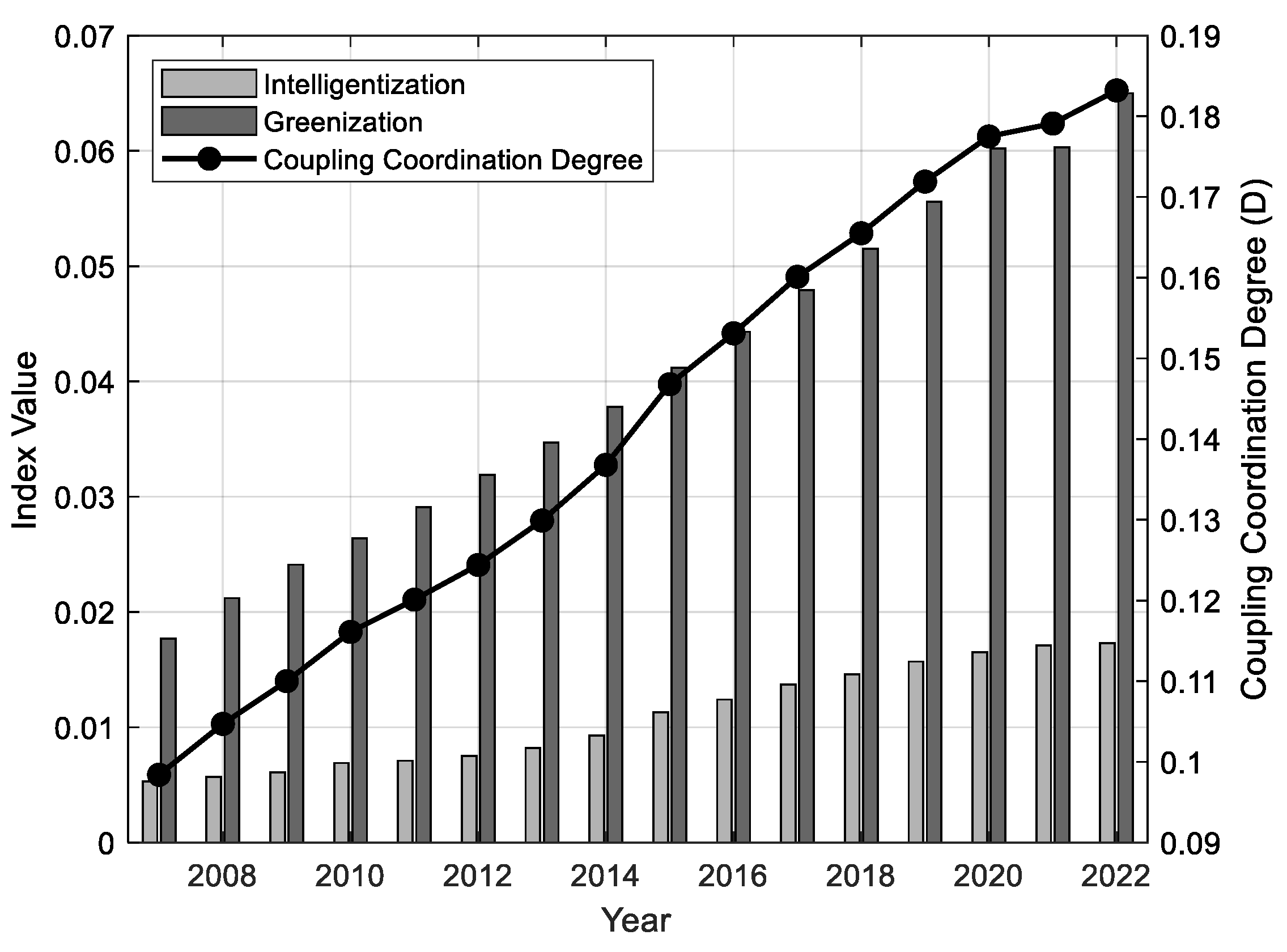

3.2. Variable Setting and Model Establishment

3.2.1. Variable Setting

- (1)

- Independent variables: focal enterprises’ coordinated development degree of intelligentization and greenization

- (2)

- Dependent variable: integration degree of intelligentization and greenization in peer enterprises

- (3)

- Control variables

3.2.2. Model Establishment

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Baseline Regression

4.2. Robustness Tests

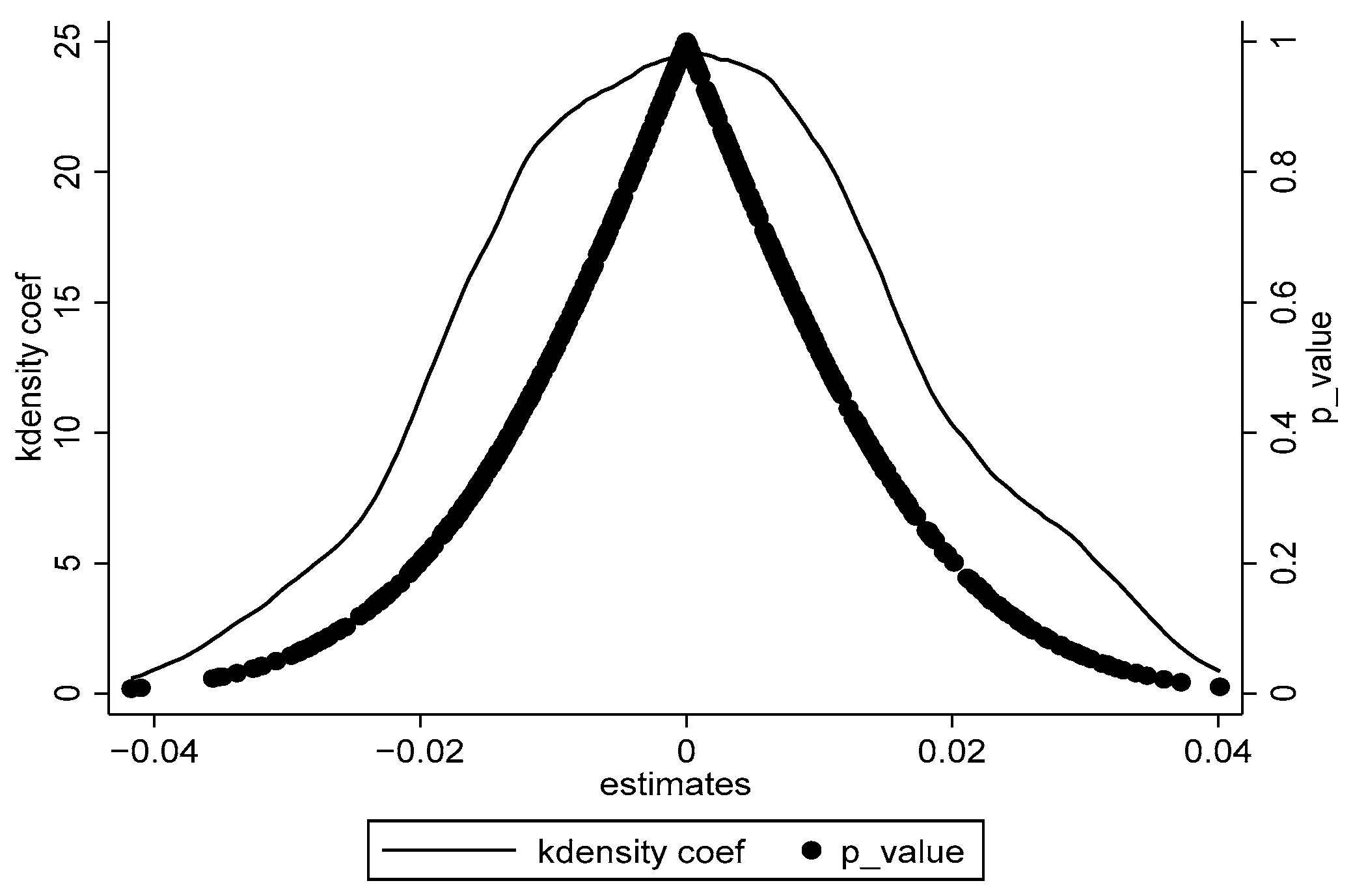

4.2.1. Placebo Test

4.2.2. Inclusion of Peer Characterization Variables

4.2.3. Substitution of Core Variables

4.2.4. Exclude Sample Selection Interference

4.2.5. Dynamic Effects Test

4.3. Endogenous Treatment

5. Analysis of Impact Mechanisms

5.1. The Perspective of Intelligentization Empowering Greenization

5.2. The Perspective of Intra-Industry Competition Effect

5.3. The Perspective of Lead–Follow Learning Effect

6. Further Discussion

6.1. Tests Based on Different Enterprise Attributes

6.1.1. Classified by Ownership Type

6.1.2. Classified by Factor Intensity Type

6.2. Tests Based on Different Spatial Dimensions

6.3. Tests Based on Different Industrial Organizational Structures

7. Conclusions, Policy Recommendations, and Limitations

7.1. Conclusions

7.2. Policy Recommendations

7.3. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ye, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhong, N.; Tu, X.; Jia, J.; Wang, J. Tackling environmental challenges in pollution controls using artificial intelligence: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 699, 134279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, L.; Wang, W.; Wang, G. Intelligentized reconstruction and green transformation of enterprises: A study based on micro data of imported industrial robots. Econ. Perspect. 2024, 3, 44–60. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, D.; Bu, W. The usage of robots and enterprises’ pollution emissions in China. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2022, 39, 157–176. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu, D.; Restrepo, P. Robots and jobs: Evidence from US labor markets. J. Political Econ. 2020, 128, 2188–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Tang, M. Analysis of the impact mechanisms of the digital economy and executive risk preference on the intelligent transformation of enterprises. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 102, 104389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Liu, Q.; Feng, G. Intelligent manufacturing and green development: From the perspective of Chinese industrial firms importing robots. J. World Econ. 2023, 46, 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Biswanath, B.; Puspanjali, B.; Ugur, K.; Litu, S.; Narayan, S. Artificial intelligence-driven green innovation for sustainable development: Empirical insights from India’s renewable energy transition. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 389, 126285. [Google Scholar]

- Leary, M.T.; Roberts, M.R. Do peer firms affect corporate financial policy. J. Financ. 2014, 69, 139–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q. Peer effect on the integration of industrial-financial capital: Empirical evidence from A-share listed companies. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2024, 27, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Li, Z. Research on peer effect of enterprise ESG information disclosure. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2023, 26, 126–138. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, T.; Fresard, L. Learning from peers’ stock prices and corporate investment. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2014, 111, 554–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y.; Peng, Z.; Cai, J.; Yang, H. Peer effect of capital structure in business cycle. Account. Res. 2020, 11, 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Lou, J.; Hu, H. Peer effect of enterprise digital transformation in the network constructed by supply chain common-ownership. China Ind. Econ. 2023, 4, 136–155. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Chu, X. Research on the peer group effect of green technology innovation in manufacturing enterprises: Reference function based on multi-level situation. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2022, 25, 68–81. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Hu, Y. Digital peer effects and the resilience of industrial and supply chains. Ind. Econ. Res. 2024, 5, 44–56. [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb, A.; Tucker, C. Digital economics. J. Econ. Lit. 2019, 57, 3–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, M.; Wang, Y.; Liang, Y. The peer effect of digital transformation and enterprise breakthrough innovation: Based on the perspective of interlocking directorate network. Sci. Sci. Manag. S. T 2025, 46, 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, S.; Wang, C. How does peer effect of digital transformation influence the depth of enterprise internationalization? evidence from A-share listed enterprises. East China Econ. Manag. 2024, 38, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; He, L.; Lin, X. Robot adoption and energy performance: Evidence from Chinese industrial firms. Energy Econ. 2022, 107, 105837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Xin, K. Impact of AI patent networks on the intelligent development of enterprises. Sci. Res. Manag. 2024, 45, 118–126. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, L.; Liang, C.; Rao, J. Industry peer effect in M&A decisions of China’s listed companies. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2016, 19, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wan, M. Research on peer effect of enterprise digital transformation and influencing factors. Chin. J. Manag. 2021, 18, 653–663. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Liu, T.; Li, N. Financial asset allocation peer effect and stock price crash risk under the Co-analyst network. Account. Res. 2023, 7, 103–117. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, N.; Bai, Y.; An, Y. Active imitation or passive reaction: Research on the peer effect on trade credit. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2022, 25, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Wang, C.; Deng, M. “Peer effect” in capital structure of China’s listed firms. Bus. Manag. J. 2017, 39, 181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Wang, F. Intelligent transformation, cost stickiness and enterprise performance—An empirical study based on traditional manufacturing enterprises. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2022, 40, 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Q.; Niu, Y.; Xu, H. Research on the mechanism of the impact of enterprise data element utilization level on investment efficiency—Using data elements to activate the intermediary role of redundant resources. J. Cent. Univ. Financ. Econ. 2023, 11, 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Dong, W. How the rise of robots has affected China’s labor market: Evidence from China’s listed manufacturing firms. Econ. Res. J. 2020, 55, 159–175. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, X.; Yang, S. Digital empowerment, source of digital input and green manufacturing. China Ind. Econ. 2022, 9, 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Zhang, L. Carbon emissions and assets pricing—Evidence from Chinese listed firms. China J. Econ. 2022, 9, 28–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Guo, Y.; Cao, J.; Xu, J. Local government financing vehicle debt and environmental pollution control. J. Manag. World 2022, 38, 96–118. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Kong, D. Local environmental governance pressure, executive’s working experience and enterprise investment in environmental protection: A quasi-natural experiment based on China’s “Ambient Air Quality Standards 2012”. Econ. Res. J. 2019, 54, 183–198. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.; Lyu, X. Responsible multinational investment: ESG and Chinese OFDI. Econ. Res. J. 2022, 57, 83–99. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, F.; Li, W. Research on the coupling coordination degree of “upstream-midstream-downstream” of China’ s wind power industry chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 283, 124633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Meng, Y. Coupling coordination measurement and evaluation of urban digital economy and green technology innovation in China. China Soft Sci. 2022, 9, 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: http://www.csrc.gov.cn/csrc/c101864/c1024632/content.shtml (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Wang, L.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, S. Peer effects in corporate cash dividends policy. Syst. Eng. Theory Pract. 2021, 41, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Lin, S.; Shi, Z.; Wang, S. Research on the peer effect of listed companies’ leverage manipulation. Chin. J. Manag. 2025, 22, 1774–1782. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Q.; Chen, L.; Xie, G.; Zhai, Z.; Zhao, L. The community structure of interlocking directors network and corporate green innovation peer effects. Manag. Rev. 2025, 37, 84–96. [Google Scholar]

- Gyimah, D.; Machokoto, M.; Sikochi, A. Peer influence on trade credit. J. Corp. Financ. 2020, 64, 101685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Su, C.; Li, H.; Kong, D. Excess leverage and region—Based corporate peer effects. J. Financ. Res. 2018, 9, 74–90. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, L.; Li, X.; Li, S. Urban system structure evolution, dynamic industrial agglomeration and synergistic spatial efficiency improvement. J. Chongqing Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 29, 70–87. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Fung, H.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, Z. Interlocking directorate networks, financial constraints and the social responsibility of private enterprises. Chin. J. Manag. 2020, 17, 1208–1217. [Google Scholar]

| System Level | Standardized Layer | Specific Indicators | Measurement | Weight Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intelligentization | Basic support | Software investment | Ratio of intelligent software investment to total investment | 0.092 |

| Hardware investment | Ratio of intelligent hardware investment to total investment | 0.129 | ||

| Degree of penetration | AI word frequency | Frequency of AI-related keywords in annual reports | 0.133 | |

| Utilization of data elements | Number of disclosures of five indicators in annual reports | 0.102 | ||

| Robotics applications | Industrial robot penetration | 0.015 | ||

| Innovation environment | Innovative inputs | Total R&D expenditures | 0.117 | |

| R&D staff | Number of R&D staff | 0.112 | ||

| Digital technology innovation | Number of digital economy patent filings | 0.198 | ||

| Economic impact | Operational efficiency | Inventory turnover (=cost of goods sold/average inventory) | 0.102 | |

| Greenization | Green Innovation | Green invention patent | Total number of green invention patent applications | 0.342 |

| Green new patent | Total green utility model patent applications | 0.396 | ||

| Emissions | Carbon emissions | Calculated carbon emissions from enterprises’ reports | 0.020 | |

| Air pollution | Log of combined air pollution equivalent | 0.026 | ||

| Water contamination | Logarithm of combined water body pollution equivalent | 0.001 | ||

| Energy consumption | Water consumption, electricity consumption, etc. | Converted to standard coal equivalents | 0.025 | |

| Environmental investment | Environmental investment | Total environmental protection expenditures | 0.181 | |

| Social responsibility | ESG rating | Assign ESG ratings from 1 to 9 in descending order | 0.009 |

| Range of Coupling Coordination Degree | Coupling Coordination Level |

|---|---|

| 0 ≤ D ≤ 0.3 | Low coupling coordination |

| 0.3 < D ≤ 0.5 | Medium coupling coordination |

| 0.5 < D ≤ 0.8 | High coupling coordination |

| 0.8 < D ≤ 1 | Extreme coupling coordination |

| Variant | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | 24,753 | 0.110 | 0.024 | 0.059 | 0.205 |

| Peer_D | 24,753 | 0.110 | 0.007 | 0.059 | 0.172 |

| Age | 24,753 | 10.472 | 7.188 | 1.000 | 27.000 |

| Size | 24,753 | 22.338 | 1.316 | 20.081 | 26.408 |

| Lev | 24,753 | 0.433 | 0.199 | 0.061 | 0.887 |

| Tobin | 24,753 | 1.978 | 1.201 | 0.840 | 7.780 |

| Roe | 24,753 | 0.060 | 0.127 | −0.667 | 0.327 |

| MBratio | 24,753 | 0.632 | 0.249 | 0.129 | 1.190 |

| Cash | 24,753 | 0.183 | 0.124 | 0.017 | 0.598 |

| Top1 | 24,753 | 34.825 | 14.747 | 8.850 | 74.660 |

| Growth | 24,753 | 0.167 | 0.365 | −0.475 | 2.250 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| D | D | D | |

| peer_D | 0.902 *** | 0.865 *** | 0.409 *** |

| (0.021) | (0.019) | (0.048) | |

| Age | −0.001 *** | −0.001 | |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| Size | 0.010 *** | 0.008 *** | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | ||

| Lev | −0.003 *** | −0.003 ** | |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| Tobin | −0.001 | 0.001 | |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| Roe | −0.003 *** | −0.002 ** | |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| MBratio | −0.011 *** | −0.002 ** | |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| Cash | 0.015 *** | −0.000 | |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| Top1 | −0.001 *** | −0.001 | |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| Growth | −0.001 *** | −0.001 * | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | ||

| _cons | 0.011 *** | −0.191 *** | −0.092 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.012) | |

| Year | NO | NO | YES |

| Industry | NO | NO | YES |

| Area | NO | NO | YES |

| N | 24,753 | 24,753 | 23,806 |

| R2 | 0.070 | 0.257 | 0.093 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | D | D | D | |

| peer_D | 0.841 *** | 0.850 *** | 0.202 *** | 0.197 *** |

| (0.028) | (0.025) | (0.055) | (0.054) | |

| peer_Age | −0.000 ** | −0.000 | −0.001 ** | −0.001 ** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| peer_Size | 0.000 | −0.009 *** | −0.002 | −0.001 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| peer_Lev | 0.004 | 0.006 ** | 0.004 | 0.005 |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| peer_Tobin | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 * |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| peer_Roe | −0.014 * | −0.003 | −0.013 | −0.015 * |

| (0.008) | (0.007) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| peer_MBratio | 0.003 | 0.011 ** | 0.011 | 0.013 * |

| (0.006) | (0.005) | (0.007) | (0.007) | |

| peer_Cash | −0.011 ** | −0.023 *** | −0.060 *** | −0.053 *** |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.010) | (0.010) | |

| peer_Top1 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| peer_Growth | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| _cons | 0.016 | −0.013 | 0.159 *** | −0.024 |

| (0.012) | (0.010) | (0.033) | (0.034) | |

| Controls | NO | YES | NO | YES |

| Year | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| Industry | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| Area | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| N | 24,753 | 24,753 | 23,806 | 23,806 |

| R2 | 0.071 | 0.285 | 0.067 | 0.097 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | D1 | D2 | D2 | |

| peer_D1 | 0.724 *** | 0.669 *** | ||

| (0.022) | (0.022) | |||

| peer_D2 | 0.724 *** | 0.669 *** | ||

| (0.022) | (0.022) | |||

| _cons | 0.063 *** | −0.417 *** | 0.063 *** | −0.417 *** |

| (0.018) | (0.028) | (0.018) | (0.028) | |

| Controls | NO | YES | NO | YES |

| Year | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Area | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 36,967 | 36,967 | 36,967 | 36,967 |

| R2 | 0.305 | 0.318 | 0.305 | 0.318 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | D | D | D | |

| peer_D | 0.660 *** | 0.261 *** | 0.668 *** | 0.287 *** |

| (0.029) | (0.063) | (0.029) | (0.063) | |

| _cons | −0.150 *** | −0.009 | −0.150 *** | −0.010 |

| (0.005) | (0.047) | (0.005) | (0.047) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year | NO | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry | NO | YES | YES | YES |

| Area | NO | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 14,889 | 14,806 | 14,858 | 14,775 |

| R2 | 0.203 | 0.068 | 0.204 | 0.067 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| delta_D | delta_D | delta_D | delta_D | |

| delta_peer_D | 0.605 *** | 0.526 *** | 0.587 *** | 0.402 *** |

| (0.035) | (0.043) | (0.035) | (0.048) | |

| _cons | −0.000 | 0.001 | −0.008 *** | −0.019 |

| (0.000) | (0.017) | (0.003) | (0.020) | |

| Controls | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| Area | NO | YES | NO | YES |

| Industry | NO | YES | NO | YES |

| N | 21,985 | 21,075 | 21,985 | 21,075 |

| R2 | 0.013 | 0.011 | 0.017 | 0.016 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| peer_D | D | |

| mean_returns | 0.007 *** | |

| (0.000) | ||

| peer_D | 0.917 ** | |

| (0.436) | ||

| _cons | 0.109 *** | −0.191 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.049) | |

| Cragg–Donald Wald F | 350.202 | |

| [16.380] | ||

| Controls | YES | YES |

| Year | YES | YES |

| Industry | YES | YES |

| Area | YES | YES |

| N | 14,755 | 14,755 |

| R2 | 0.650 | 0.087 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Int | Int | Green | Green | Greent + 1 | Greent + 1 | |

| peer_Int | 0.869 *** | 0.834 *** | ||||

| (0.045) | (0.045) | |||||

| Int | 0.680 *** | 0.683 *** | 0.617 *** | 0.623 *** | ||

| (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.011) | (0.011) | |||

| _cons | 0.002 | −0.040 *** | 0.052 *** | 0.049 *** | 0.049 *** | 0.058 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.007) | (0.009) | |

| Controls | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | YES |

| Year | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Area | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 23,806 | 23,806 | 23,826 | 23,826 | 20,462 | 20,462 |

| R2 | 0.176 | 0.189 | 0.558 | 0.560 | 0.515 | 0.518 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| D | D | |

| peer_D | 0.630 *** | 0.568 *** |

| (0.068) | (0.067) | |

| HHI | 0.095 *** | 0.078 *** |

| (0.025) | (0.024) | |

| HHI × peer_D | −0.888 *** | −0.744 *** |

| (0.223) | (0.219) | |

| _cons | 0.057 *** | −0.115 *** |

| (0.012) | (0.014) | |

| Controls | NO | YES |

| Year | YES | YES |

| Industry | YES | YES |

| Area | YES | YES |

| N | 22,014 | 22,014 |

| R2 | 0.048 | 0.080 |

| Variables | Industry Followers React to Leaders | Industry Leaders React to Followers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market Share | Enterprise Size | Technical Advantages | Market Share | Enterprise Size | Technical Advantages | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| peer_D | 0.562 *** | 0.717 *** | 0.218 *** | −0.023 | 0.077 | 0.247 * |

| (0.081) | (0.090) | (0.065) | (0.191) | (0.110) | (0.139) | |

| _cons | −0.125 *** | −0.264 *** | −0.034 * | 0.726 *** | 0.011 | −0.044 |

| (0.026) | (0.024) | (0.019) | (0.198) | (0.027) | (0.036) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Area | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 7256 | 7113 | 13,114 | 258 | 7186 | 6789 |

| R2 | 0.196 | 0.221 | 0.068 | 0.369 | 0.057 | 0.078 |

| Variables | Ownership Type | Factor Intensity Type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOEs | Non-SOEs | Labor-Intensive | Capital-Intensive | Technology-Intensive | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| peer_D | 0.401 *** | 0.260 *** | 0.101 | 0.227 ** | 0.704 *** |

| (0.070) | (0.057) | (0.075) | (0.110) | (0.103) | |

| _cons | −0.085 *** | −0.094 *** | −0.012 | −0.103 *** | −0.185 *** |

| (0.018) | (0.013) | (0.022) | (0.025) | (0.017) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Area | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Between-group coefficient | 5.86 (p = 0.015) | 19.64 (p = 0.000) | |||

| N | 9350 | 14,456 | 6931 | 5477 | 11,296 |

| R2 | 0.092 | 0.109 | 0.052 | 0.068 | 0.133 |

| Variables | Province Peer Effects | City Peer Effects | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large-Scale Cities | Small- and Medium-Sized Cities | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| peer_D | 0.108 *** | 0.046 ** | 0.016 |

| (0.040) | (0.022) | (0.029) | |

| _cons | −0.062 *** | −0.065 *** | −0.044 |

| (0.012) | (0.013) | (0.028) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES |

| Year | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry | YES | YES | YES |

| Area | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 23,816 | 19,071 | 2635 |

| R2 | 0.090 | 0.091 | 0.101 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | D | D | D | |

| peer_D | 0.178 *** | 0.014 *** | 0.101 *** | 0.011 *** |

| (0.005) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| _cons | 0.092 *** | 0.115 *** | −0.133 *** | −0.070 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.008) | (0.002) | (0.009) | |

| Controls | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| Year | NO | YES | NO | YES |

| Industry | NO | YES | NO | YES |

| Area | NO | YES | NO | YES |

| N | 46,895 | 45,212 | 46,895 | 45,212 |

| R2 | 0.026 | 0.063 | 0.256 | 0.095 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hao, L.; Li, X.; Ji, Z. Individual Behavior or Collective Phenomenon: Peer Effects in the Coordinated Intelligentization and Greenization of Chinese Manufacturing Firms. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11013. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411013

Hao L, Li X, Ji Z. Individual Behavior or Collective Phenomenon: Peer Effects in the Coordinated Intelligentization and Greenization of Chinese Manufacturing Firms. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11013. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411013

Chicago/Turabian StyleHao, Liangfeng, Xinyuan Li, and Zhongjuan Ji. 2025. "Individual Behavior or Collective Phenomenon: Peer Effects in the Coordinated Intelligentization and Greenization of Chinese Manufacturing Firms" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11013. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411013

APA StyleHao, L., Li, X., & Ji, Z. (2025). Individual Behavior or Collective Phenomenon: Peer Effects in the Coordinated Intelligentization and Greenization of Chinese Manufacturing Firms. Sustainability, 17(24), 11013. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411013