Abstract

Poland, as an important transit hub in Europe, has experienced a dynamic increase in the significance of air transport in recent years. However, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 led to a severe collapse of passenger aviation worldwide. The aim of this study was to assess the condition of the passenger air transport market in Poland against the background of selected European countries in connection with the disruptions caused by the pandemic. The Holt–Winters models, based on pre-pandemic data, made it possible to forecast passenger transport volumes in the absence of the crisis and compare them with actual values to estimate losses and the extent of recovery. In the first three months after the outbreak, passenger losses ranged from 7.8 million in Sweden to 13.5 million in Portugal, while Poland recorded 10.9 million; after one year, cumulative losses in Poland reached 44.5 million. In addition, the pace of restoration of selected markets was evaluated. In 2022, Poland reached levels of up to 145% of its reference value, indicating one of the strongest restoration dynamics among the analyzed countries. The results show that all markets experienced sharp declines followed by a comparable rate of growth. The findings confirm Poland’s strengthening position in the European air transport system and highlight the need to build resilience to potential future crises.

1. Introduction

Air transport plays a special role in the movement of passengers due to its ability to provide comfortable travel over long distances in a relatively short time [1]. For this reason, it is an attractive mode of transport for all travelers, regardless of whether they travel for personal, tourist, or business purposes, which in turn positively contributes to increased mobility and economic development. Poland, as an important transit hub in Europe, has in recent years experienced a dynamic increase in the importance of air transport. However, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 led to serious disruptions in passenger aviation [2]. This was primarily the result of the progressively introduced restrictions aimed at limiting the spread of the virus. Self-isolation, social distancing, mandatory quarantines, as well as remote work and education, had a clear impact on the functioning and activity of the population [3]. Numerous restrictions and the need to adapt lifestyles to completely new conditions resulted in a decline in mobility and a reduction in demand for passenger transport. Moreover, fears of possible contact with infected individuals in public spaces caused people to more frequently choose individual means of transport, avoiding public transportation [4]. In addition, many people abandoned international travel in favor of local trips [5]. Thus, the pandemic period translated into changes in transport mode preferences and affected travel patterns. This situation was reflected in the functioning of passenger air transport markets worldwide, including in Europe, and consequently also in Poland [6]. The number of flights decreased, interest in international travel declined, and airlines were forced to adapt their operations to a new and challenging reality [7]. Given the situation at that time, both at the national and international levels, the aim of this study was to assess the condition of the passenger air transport market in Poland against the background of selected European countries in connection with the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The research is based on two key research questions:

- How did the COVID-19 pandemic affect the performance of passenger air transport in Poland compared with selected European countries?

- From the post-pandemic perspective, how did the process of recovery of the passenger air transport market in Poland proceed in relation to other European countries?

The article presents a comparative analysis of the condition of passenger air transport in Poland and selected European countries during the COVID-19 pandemic disruption, applying the Holt-Winters forecasting method to assess losses and the extent of recovery across individual markets. The study provides evidence that the aviation sector in Poland, similarly to other countries, experienced a dramatic decline in the number of passengers carried. At the same time, it demonstrated a recovery dynamic comparable to that of markets with stronger economies, which is a positive phenomenon. The results highlight the importance of the transport market’s resilience to epidemic-related crises and indicate that Poland’s strategic location and the ongoing development of its infrastructure may foster long-term growth. The paper also emphasizes the need to develop strategies that enhance the stability and preparedness of the aviation market for future threats of a similar nature.

This study contributes to the existing research by applying a single forecasting approach consistently across several European aviation markets (Poland, Portugal, Sweden, Norway, Switzerland), by quantifying the scale of COVID-19 pandemic-related changes using pre-pandemic trends and seasonal patterns, and by comparing differences in the extent and pace of restoration between air passenger transport markets with distinct structural characteristics.

This publication consists of several sections. The introduction presents a general outline of the study, including its purpose and research questions. This is followed by a literature review focusing on publications addressing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the economy and the transport sector, as well as studies employing mathematical methods to analyze transport disruptions resulting from the epidemic crisis. Subsequently, the materials and methods applied in the study are described. Section 4 constitutes the core of the paper and includes the review and selection of markets for comparison, the modeling and forecasting of passenger numbers in selected countries, along with a supplementary comparison of alternative forecasting approaches to verify the robustness of the results, and a comparative analysis of market losses and recovery. and a comparative analysis of market losses and recovery. Finally, the conclusions are presented, summarizing the study’s findings and key results.

2. Literature Review

The COVID-19 pandemic became a phenomenon that was closely monitored and analyzed, which was reflected in the growing number of published reports, information bulletins, and scientific papers focused on this threat. The global spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus shook the world economy, leading to its prolonged destabilization. This situation was reflected in serious disruptions to transport systems [8], particularly affecting passenger air transport. Initially, airlines attempted to maintain regular flight schedules in order to meet public demand. However, it was soon observed that a characteristic feature of COVID-19 was the rapid transmission of the virus across different regions of the world [9]. Most countries recognized international and regional air connections as one of the main routes for pathogen transmission [10]. Therefore, governments around the world decided to introduce travel restrictions to curb the spread of the virus [11]. In response to the threat, there were increasing instances of countries refusing to accept flights from states and regions with high infection rates. International borders began to close, which not only made foreign destinations inaccessible to visitors but also created difficulties for people attempting to return to their home countries [12,13]. Air transport also became less attractive due to the requirements imposed by some governments on travelers. These often involved mandatory testing, the obligation to present a vaccination certificate, or enforced quarantine.

Another important factor influencing the condition of passenger air transport was the restrictions imposed on the hotel industry. The availability of hotel facilities became strictly dependent on government decisions, which varied according to the current epidemiological situation. Hotels were alternately closed and reopened for specific groups. This made it impossible to plan vacations or business trips in advance, which ultimately led to a decline in interest among passengers traveling for tourism and business purposes [14].

Other studies have shown that psychological factors were also significant for the demand for air travel. It was found that the spread of SARS-CoV-2 caused concern among many people, and in extreme cases even fear of infection through close contact with others in airports or on airplanes [15]. Flights were increasingly canceled, or travelers chose alternative and seemingly safer modes of transportation. The development of videoconferencing technology also contributed to the decline in the number of passengers carried, as it made it possible to conduct business and social activities without the need for physical travel [16,17].

All of the above-mentioned factors led to a severe decline in travel demand, thereby generating significant disruptions in passenger aviation [18]. As a result, the analytical approach has become a popular direction in the literature, aiming to illustrate the broad impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on transport. Researchers frequently apply mathematical methods to examine the functioning of transport processes under crisis conditions, including passenger air transport. Existing studies can generally be examined in relation to three aspects: the research region, the applied methods, and the main areas of application.

A significant portion of publications focuses on Europe. For example, in Poland researchers employed various time series analysis methods, ranging from the discrete wavelet transform (DWT) and statistical tests used to identify seasonality, to exponential smoothing and Fourier spectral analysis. These approaches made it possible not only to capture the sharp declines in air traffic [19] but also to indicate differences in the number of passengers handled at specific airports (e.g., Szczecin Goleniów) [20]. Other studies focused on assessing the variation in passenger transport losses among selected EU countries in the years 2015–2021 [21], as well as on a multidimensional comparative analysis of the Polish and German markets in 2020–2022, highlighting different initial recovery paths following the outbreak of the pandemic [22]. In Germany, additional research examined the financial condition of airports (Frankfurt, Munich), using stochastic equations with the standard Wiener process to forecast EBITDA [23].

In Latin America, specifically in Brazil, the use of Bayesian structural time series (BSTS) models made it possible to estimate the impact of COVID-19 on air travel demand and the resulting changes in CO2 emissions [24]. In Colombia, BSTS models were applied to develop medium- and long-term forecasts, confirming that both passenger and freight transport demand would return to pre-pandemic levels within the next few years [25].

In Asia, research conducted on Beijing Daxing International Airport (China) was based on machine learning algorithms (the LightGBM model with SHAP values), incorporating pandemic-related variables to forecast short-term daily passenger flows at the airport terminal [26]. Meanwhile, in Turkey, actual air traffic density was compared with forecasts obtained from two models—SARIMA and the multilayer perceptron (MLP). Both models proved effective and demonstrated a significant decline in air traffic in Turkish airspace, dependent on pandemic restrictions [27]. Other comparative studies based on ARIMAX models indicated that the Asia–Pacific macroregion experienced a short-term but intense shock, followed by a rapid recovery of the air transport sector [28].

North America was primarily analyzed within comparative studies involving other parts of the world. SARIMA models, based on data from 2010 to 2019, were used to estimate monthly passenger traffic in the United States, European countries, and China from January 2020 to December 2022, assuming the absence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The results showed that in the United States and Europe, a gradual improvement in transport volumes was observed in the months following the outbreak of the pandemic, whereas in China, a clear decline in traffic occurred in 2021–2022 due to a sharp increase in the number of infections [29]. Furthermore, another comparative analysis demonstrated that in the United States, the impact of the pandemic was relatively uniform, and the recovery of domestic connections progressed faster than in Europe [30].

In the case of global-scale studies, it can be observed that they focused on analyzing virus transmission mechanisms in the context of passenger air travel. To forecast the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission, survival models (e.g., the Cox model, inverse distance model) and the concept of “effective distance” in the air transport network were applied [31]. Another study estimated the relationship between the volume of passenger air traffic and the number of COVID-19 cases worldwide, using, among others, Poisson regression models (PM, QPM) [32].

As shown, the literature employs a variety of analytical approaches, ranging from classical statistical methods and time series analyses to machine learning and network-based models. Such methods make it possible not only to analyze sudden drops in demand but also to forecast recovery scenarios, assess the effects of pandemic restrictions, evaluate economic impacts and analyze environmental consequences [33,34].

In parallel to studies focused on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, an increasing number of publications examine long-term changes taking place in the aviation sector in connection with climate-policy commitments and decarbonization targets [35,36]. These works point to the growing importance of technological developments, the role of sustainable aviation fuels and the use of market-based instruments, including emissions trading and carbon pricing, in shaping the sector’s future regulatory and cost environment [37,38]. In the European context, these issues are reflected in the Fit for 55 package, the ReFuelEU Aviation regulation, which introduces mandatory SAF blending levels [39], as well as the gradual tightening of the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) for aviation [40,41]. Scenario-based studies also show that achieving net-zero climate impacts will require improvements in energy efficiency, the use of alternative fuels and operational adjustments, and may lead to higher operating costs and ticket prices, while only moderately affecting overall demand for air travel [42,43]. This different strand of work highlights that contemporary aviation is subject to multiple, overlapping pressures, with the pandemic representing only one albeit highly disruptive factor.

However, there is a lack of studies that, from a post-pandemic perspective, compare the condition of passenger air transport in Poland with that of other European countries using forecasting models such as the Holt–Winters method to assess the losses caused by the COVID-19 crisis and the dynamics of market recovery. The identified research gap served as the starting point for this study, which is focused on analyzing the impact of the pandemic on transport performance and the course of recovery processes in passenger air transport markets in Poland and selected European countries.

3. Materials and Methods

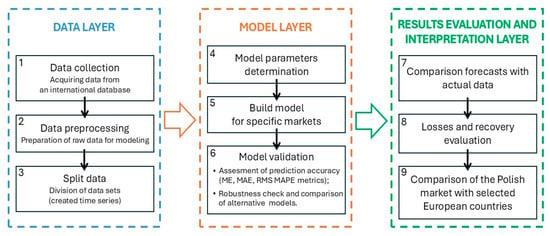

The entire research process was structured in the form of a three-layer methodological framework. This structure includes the stages of data preparation, mathematical model development and validation, as well as the analysis and interpretation of the obtained results. Figure 1 illustrates this framework by clearly outlining the sequential structure of the study and the relationships between its stages, providing a clearer context for the applied approach.

Figure 1.

Three-layer methodological framework of study outlining the sequence from data preparation to model development and results analysis.

The study, starting from data layer, utilized the database of the Statistical Office of the European Union (Eurostat), which contains extensive data on transport activities in Europe. The research was based on the dataset “Air passenger transport by type of schedule, transport coverage and country”, which was adjusted in terms of geopolitical scope, time range, and available measurement units [44]. As a result, monthly data were obtained on the total number of passengers transported by air in 30 European countries (the EU27 region plus Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland). The study covered the period from January 2004 to March 2024, as only for this time range was a complete set of monthly data available for all 30 countries. Subsequently, taking into account the long-term transport characteristics of individual national markets, countries with results comparable to those of Poland were identified. In addition, a contextual analysis of economic and infrastructural conditions was carried out to better understand the specific features of each market. In the next stage of the research, the collected data were used to construct time series representing the number of passengers transported by air in the selected countries. Each of the time series was then divided into two subsets, with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 serving as the point of division. The first subset was used to develop a mathematical model and to generate forecasts for the period following the emergence of the epidemic threat. The second subset served as a reference dataset, enabling the estimation of losses through the comparison of the actual state (reflecting the declines caused by the pandemic) with the forecasts based on data from before March 2020, which represented the potential level of air transport in the absence of disruptions.

The next layer of the study (model layer) involved the development of mathematical models describing the number of passengers transported by air. To identify and predict temporal changes, time series models are used, as they make it possible to describe the nature of the analyzed process, identify its deterministic components, and represent the process as a function consisting of such elements as a trend, seasonal fluctuations, cyclical variations, and random disturbances [45]. Identification of the individual components and the internal dynamics of a time series enables the forecasting of its future values [46]. In this study, the Holt–Winters model was applied, as it is suitable for time series that exhibit a trend, seasonal fluctuations, and random variations. Due to its flexibility, this model is widely used by researchers across various fields. For instance, in industry, it can be used for forecasting product sales [47], or electricity generation [48], while in demography it is applied to predict birth and death rates [49]. Another area of application involves the analysis of developmental trends and the forecasting of the spread of epidemic threats such as COVID-19 [50]. Moreover, the Holt–Winters method is also used in transport process modeling, including analyses of vehicle volumes and related congestion, road traffic safety studies, and forecasts of passenger transport demand [51,52]. There are two variants of this model that differ in the nature of their seasonal component. The additive model is preferred when seasonal fluctuations remain approximately constant throughout the series, whereas the multiplicative model is more suitable when seasonal fluctuations change proportionally to the level of the series [53,54]. In this study, for each of the analyzed air transport markets, a multiplicative model was applied, consisting of the forecasting equation (1) and three smoothing equations: the level Lt (2), the trend Bt (3), and the seasonality St (4):

where:

- α, δ, γ—exponential smoothing coefficients such that ;

- Yt—actual value at time t;

- S—length of the seasonality cycle (for monthly data L = 12);

- m—forecast horizon [55].

In the adopted approach, the exponential smoothing coefficients α, δ, γ were selected to achieve a high fit of the model to the actual data by minimizing the Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) [24]:

where:

- —forecast value at time t;

- —actual value at time t;

- n—number of observations.

The Holt–Winters models were estimated using an automatic optimization procedure, which determines the smoothing parameters (α, δ, γ) by minimizing the in-sample forecast errors. For each country, several candidate specifications generated by the software were compared, and the final model was selected based on the lowest MAPE value. Model validation was carried out by applying the set of accuracy metrics, by comparing AIC values across specifications, and by analyzing residual behavior using standard diagnostic tests, including the Shapiro–Wilk test. In addition, the coefficient of determination (R2) was included as a supplementary indicator of the overall fit of each model.

To present these diagnostic results explicitly, the accuracy of each model was assessed using standard error metrics. Besides MAPE, the Mean Error (ME), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) were computed according to Formulas (6)–(8):

where:

- —forecast value at time t;

- —actual value at time t;

- n—number of observations.

Lower error values indicate that the model forecasts are closer to the actual observations, which translates into higher forecast accuracy and, consequently, greater predictive capability of the model [56]. Furthermore, to compare the goodness of fit and complexity of alternative models, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was applied, the value of which was determined using the following formula:

where:

- k—number of parameters in the model;

- L—reliability function.

Lower AIC values indicate a better trade-off between model fit and the number of estimated parameters. This ensured that the model selection was not solely the result of forecast error minimization, but also maintained a balance between accuracy and model complexity. At this stage of the study, the Shapiro–Wilk test (W) was also performed to assess whether the residuals followed an approximately normal distribution [57].

The coefficient of determination (R2) was also calculated as a supplementary measure of overall model fit. It was computed using the standard formulation based on the sum of squared residuals (SSE) and the total sum of squares (SST) [58]:

where:

- —actual value at time t;

- —forecast value at time t;

- —mean of all observations;

- n—number of observations.

Additionally, for robustness purposes, several alternative forecasting models (SARIMA [59], BSM [60,61], TSLM [62], Random Forest [63,64]) were estimated using the same pre-pandemic dataset and identical accuracy metrics. These models served only as a supplementary check of the stability of the results.

The final stage (results evaluation and interpretation layer) involved the analysis and interpretation of the results obtained from the mathematical models in order to evaluate and compare the condition of selected passenger air transport markets disrupted by the epidemic threat. The forecasts derived from the Holt–Winters models were used to determine the losses (Lm) incurred during specific periods following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, which were calculated as follows:

where:

- Lm—passenger losses in the m months since the outbreak of the pandemic;

- m—number of months since the outbreak of the pandemic;

- PFm—projected number of passengers transported m months after the outbreak of the pandemic;

- PAm—actual number of passengers transported m months after the outbreak of the pandemic.

Next, the extent of loss recovery (Rm) was determined in the corresponding periods:

where:

- Rm—extent of loss recovery in the period of m months since the outbreak of the pandemic;

- m—number of months since the outbreak of the pandemic;

- PAm—actual number of passengers transported m months after the outbreak of the pandemic;

- PFm—projected number of passengers transported m months after the outbreak of the pandemic.

Additionally, to obtain a more comprehensive picture, the actual transport performance in the subsequent months following the announcement of the pandemic was compared with the data from the beginning of 2020, which made it possible to assess the pace of market restoration in each of the analyzed countries. For this purpose, the following formula was applied:

where:

- Dz—ratio of the number of passengers carried in month z relative to January 2020;

- z—months following the outbreak of the pandemic, starting in April 2020;

- Yz—actual number of passengers in month z;

- J—actual number of passengers in January 2020.

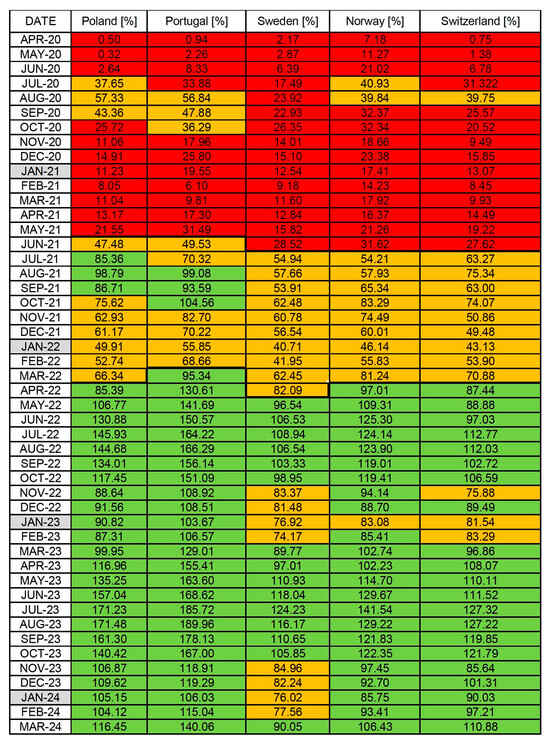

Furthermore, for the results obtained in this way, color mapping was applied, assigning appropriate colors to three percentage value ranges:

- red (≤35%)—very low or low level of market restoration;

- yellow (35.1–85%)—medium level;

- green (≥85.1%)—high level, close to or exceeding the level from January 2020.

The introduced classification facilitated the systematic interpretation of the data, enabling the identification of patterns and the comparison of the pace of restoration between individual air transport markets.

The modeling within this study was carried out using Statistica software (version 13.3, StatSoft/TIBCO, Hamburg, Germany) [65] and R Core software (version 4.4.3, R Core Team/R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) [66] with packages that provide a set of algorithms for data preprocessing, time series forecasting and machine learning. All visualizations were prepared in MS Excel. The approach described in this section made it possible to conduct a comparative analysis of the condition of air transport markets disrupted by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as to assess Poland’s situation relative to other European countries.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Selection and Characteristics of Markets Included in the Analysis

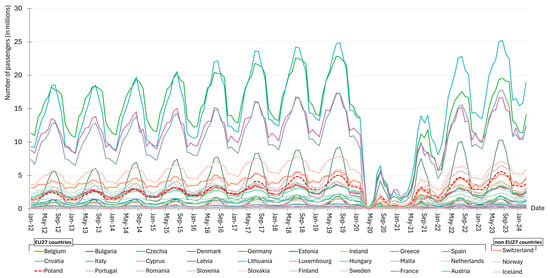

The study began with the acquisition of data from the Eurostat database containing information on air passenger transport in 35 European countries. The dataset was subsequently adjusted in terms of geopolitical scope, time horizon, and available measurement units. Verification of the completeness of monthly data made it possible to determine a study period that ensured the largest number of markets suitable for comparison. The period from January 2012 to March 2024 was adopted, excluding countries with data gaps for these dates—the United Kingdom, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia. As a result, monthly data were obtained for the total number of passengers transported by air in 30 European countries, specifically in the European Union member states (EU27) as well as Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland. The prepared dataset reflected both long-term transport trends and distinct disruptions in the trend caused by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, forming the starting point for further analysis. Figure 2 provides a comparative overview of monthly passenger volumes in 2012–2024 across 30 European countries (EU27 plus Switzerland, Norway, and Iceland), showing both the typical seasonal patterns and the sharp structural break in 2020 caused by the pandemic.

Figure 2.

Overview of monthly passenger air transport volumes across 30 European countries in 2012–2024.

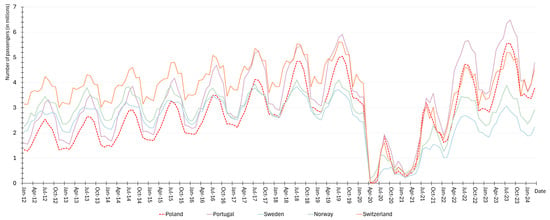

Subsequently, from the dataset comprising 30 European countries, a comparative group was selected based on the similarity of long-term passenger traffic volumes to those observed in Poland prior to the pandemic. Before the final selection, several other medium-sized markets with comparable monthly passenger volumes in the last pre-pandemic years were also taken into consideration (among others Ireland, Belgium, Denmark and Austria). The final choice of countries was made according to three criteria: (i) full availability and internal consistency of the Eurostat series for 2012–2024, (ii) the most comparable whole-term passenger volumes, and (iii) the possibility of capturing structurally distinct configurations of national air transport markets. In this respect, the inclusion of Portugal, Sweden, Norway and Switzerland provides a complete set of reference countries that, despite having pre-pandemic passenger volumes broadly comparable to those of Poland, represent different long-term demand structures shaped, respectively, by tourism activity (Portugal), domestic network needs (Sweden and Norway), and internationally oriented hub operations (Switzerland). Such structural variation within a volume-comparable group makes it possible to interpret Poland’s dynamics more reliably by contrasting its trajectory with markets exposed to different dominant drivers of passenger air transport. The monthly passenger air transport volumes in 2012–2024 for these countries are presented in Figure 3 to illustrate their relevance as reference markets. The monthly passenger air transport volumes in 2012–2024 for these countries are presented in Figure 3 to demonstrate their relevance as comparable markets.

Figure 3.

Overview of monthly passenger air transport volumes in 2012–2024 for Poland and markets selected for further analysis.

In addition, key demographic, economic, and infrastructural indicators were compiled to characterize the structural profile of the selected countries and to support the justification for their inclusion in the subsequent stages of the analysis. These characteristics provide essential background for interpreting the comparative results discussed later in the study. The detailed values of these indicators are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic, economic, and infrastructural characteristics of Poland and the markets selected for further analysis.

As shown in Table 1, among the countries included in the further stages of the study, there is a clear differentiation, particularly in terms of population size, economic performance, land area, and the number of airports. These differences reflect the specific characteristics of individual markets, thereby increasing the comparative value of the entire analysis. Although Poland has a relatively lower GDP per capita compared to the Scandinavian countries and Switzerland, in 2023 it recorded a high passenger volume of over 50 million people. This result was comparable to the Swiss market and exceeded the volumes achieved in Sweden and Norway. This indicates that after the COVID-19 pandemic, Poland has been consistently becoming an increasingly important transport hub in Central Europe, mainly due to the expansion of international routes offered by low-cost airlines, as well as the strengthening position of the national carrier LOT Polish Airlines. Among the analyzed countries, the highest passenger transport volume was recorded in Portugal, which handled 61.1 million passengers in 2023—about 11 million more than Poland—despite having a population more than three times smaller. This high level of air traffic primarily results from the structure of Portugal’s economy and its geographical location. The country is strongly tourism-oriented, and its attractiveness as a leisure destination means that a significant share of passenger transport is generated by foreign visitors. In the case of Sweden and Norway, it can be observed that compared to Poland, these countries have a much higher GDP per capita, as well as exceptionally well-developed domestic air transport networks—with 41 and 45 civil airports, respectively. The large number of airports demonstrates that in both countries, air transport plays a crucial role not only in international connections but also as an essential mode of internal communication within the Scandinavian region, characterized by vast territory, low population density, and geographical barriers such as mountain ranges and numerous fjords. Meanwhile, Switzerland, despite having the smallest area and population among all the compared countries, recorded nearly 52 million air passengers in 2023, according to the available data. This high level of passenger transport is directly related to Switzerland’s significance on the international stage, where its role as a financial and institutional center is combined with a well-developed transport infrastructure. Moreover, the strong position of the national carrier SWISS, which is part of the German Lufthansa Group, further reinforces this effect.

The conducted selection and analysis of the conditions of individual markets made it possible to establish a comparative perspective for assessing the situation in Poland against other European countries. Therefore, the selection of countries constituted the starting point for the next stage of the study, in which mathematical models were developed to forecast the level of air passenger transport under conditions without disruptions related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

4.2. Modeling and Forecasting of the Number of Carried Passengers in Selected Countries

The application of mathematical modeling enables the study of transport processes under crisis conditions and the assessment of their resilience. In this case, by employing the Holt–Winters model, forecasts were generated based on pre-pandemic data to determine the potential level of passenger transport in the absence of epidemic disruptions. For all selected countries, the multiplicative variant of the model was applied, as it allows capturing both development trends and the distinct seasonality characteristic of the air passenger transport market. The exponential smoothing coefficients α, δ, and γ were selected in order to achieve a high degree of model fit to actual data by minimizing the Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE).

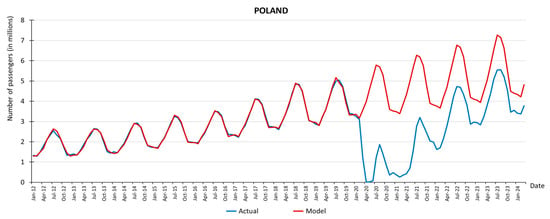

The modeling process began with Poland. The lowest MAPE value, amounting to 1.85%, was obtained for the parameters α = 0.9, δ = 0.1, and γ = 0.1. The results indicate a strong agreement between the forecasted and actual values up to the outbreak of the pandemic. However, in the subsequent months, due to COVID-19, a significant deviation became apparent, particularly during the period March–June 2020. Actual passenger transport plummeted sharply, reaching only 10.4 thousand in May 2020, whereas the model predicted a continued upward trend. It is also noteworthy that by mid-2023, the forecasts indicated that the number of carried passengers should exceed the record level of 7 million. It should be noted that this represents a forecasted level reflecting the development potential of the market based on historical data, which in practice may be constrained by various financial, infrastructural, or organizational factors. In this context, particular importance is attached to the implementation of the Central Communication Port (CPK) project, which aims to create a transport hub integrating passenger and cargo air traffic with the rail and road networks. The main component of this project will be a new airport, which is ultimately expected to become the largest hub in Central and Eastern Europe, handling millions of passengers annually and providing long-haul connections [67]. According to the latest forecasts by IATA, CPK will be capable of serving around 32 million passengers in its first full year of operation, and by 2040 this number may increase to as many as 40 million. The investment is expected to significantly enhance Poland’s air connectivity, thereby strengthening the country’s competitiveness in the European market. It also assumes a high share of transfer traffic and a developed cargo activity, both of which may contribute substantially to overcoming existing limitations and further market growth [68]. Against this background, it is a positive development that since 2022, actual passenger traffic has gradually recovered its typical seasonality, and during the summer peaks of 2022 and 2023, the observed values were already much closer to the optimistic forecasts, indicating market stabilization and a return to a growth trajectory. A comparison of the model values with the actual number of passengers carried by air transport in Poland is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Comparison of model forecasts with the actual number of air transport passengers in Poland.

As part of the verification process, the Shapiro–Wilk test was carried out, and the result (W = 0.978, p-value = 0.105) confirmed that the residuals followed a distribution close to normal. The obtained AIC value of 2466.5 indicates a good model fit with moderate complexity. The R2 value for the model was 0.99602. In addition, to further assess the forecast accuracy, the ME, MAE, and RMSE metrics were applied, with their low values confirming a high level of model precision (Table 2).

Table 2.

Assessment of forecast accuracy in the Holt–Winters model for the Polish market.

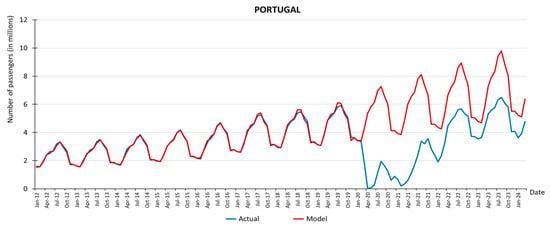

For the case study of Portugal, the best-fitting model was obtained with the parameters α = 0.8, δ = 0.1, γ = 0.1, yielding a MAPE of 1.97%. Similarly to Poland, the forecasts indicated a continued dynamic market expansion, which was abruptly interrupted by the epidemic crisis. The developed model accurately reproduced the characteristics of passenger traffic observed before the COVID-19 pandemic. After the outbreak, the largest discrepancies between the forecasts and actual values occurred during the summer months of 2020 (difference of approx. 16.99 million) and 2021 (difference of approx. 15.28 million). In contrast, during the winter season, the deviations were smaller (around 10.13 million in 2021), reflecting the lower demand for air transport outside the holiday period. Portugal thus represents a market strongly dependent on tourism-driven demand, which was severely constrained by the mobility restrictions and epidemiological safety procedures in force at the time. From 2022 onwards, a gradual restoration of seasonal patterns can be observed, while the still significant differences from the forecasts stem from the fact that the historically based model assumed the achievement of record traffic levels under a no-crisis scenario (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Comparison of model forecasts with the actual number of air transport passengers in Portugal.

As in the previous case, the conformity of the model residuals with the normal distribution was verified. In the Shapiro–Wilk test, the result was W = 0.982 with a p-value = 0.184. The AIC value of 2552.2 indicates a level of model complexity similar to that obtained for the Polish case study. This model achieved an R2 of 0.9933. In addition to MAPE, the values of the ME, MAE, and RMSE were also calculated (Table 3).

Table 3.

Assessment of forecast accuracy in the Holt–Winters model for the Portuguese market.

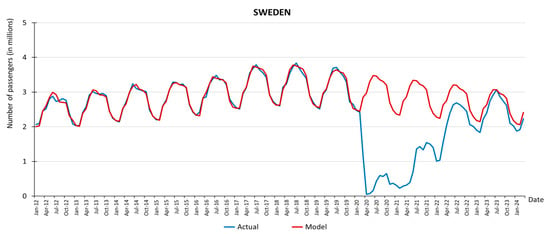

For Sweden, the best fit for the Holt–Winters model was achieved with the parameters α = 0.6, δ = 0.1, γ = 0.1. The developed model accurately captured both the trend and seasonality of the Swedish passenger market, as evidenced by a low MAPE of approximately 1.64%. It is worth noting that even before the pandemic, in 2019, there was a decline in the annual number of passengers compared to the record level of 2018 (a year-on-year difference of about 1.33 million passengers), suggesting that the airline market’s performance was also constrained by factors unrelated to the epidemic crisis. In the first half of 2020, similar to the Polish and Portuguese markets, there was a sharp collapse in passenger traffic, resulting from pandemic restrictions and the associated changes in society’s travel needs. The 2021–2022 period brought a noticeable recovery, although seasonal peaks were still below those projected under a no-crisis scenario. The turning point came in 2023, as from April onwards, the actual values gradually approached the forecasts, and during the summer, the two series almost completely overlapped. This can be interpreted as a return of the Swedish market to the level of passenger traffic that would have been achieved without pandemic disruptions. This demonstrates the relatively high resilience of Sweden’s passenger air transport, largely based on domestic connections. The comparison of model forecasts with the actual number of passengers transported in Sweden is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Comparison of model forecasts with the actual number of air transport passengers in Sweden.

Model verification confirmed its validity. The Shapiro–Wilk test statistic was W = 0.986 with a p-value = 0.363, and the AIC was 2471.1. The coefficient of determination (R2) for this model amounted to 0.98304. Additionally, other error metrics such as ME, MAE, and RMSE also indicate a high accuracy of the forecasts (Table 4).

Table 4.

Assessment of forecast accuracy in the Holt–Winters model for the Swedish market.

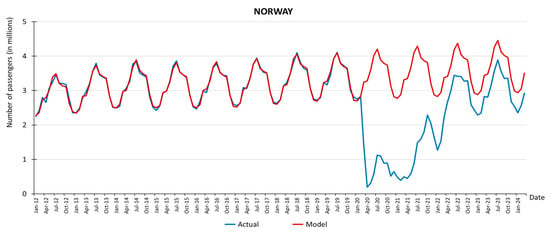

The Norwegian market was best described by the Holt–Winters model with parameters α = 0.3, δ = 0.1, γ = 0.1. The low MAPE of approximately 1.31% indicates that the forecasts obtained were the most accurate among all analyzed cases. Between 2012 and 2019, the market in Norway experienced moderate growth without the significant increases characteristic of countries such as Poland or Portugal. Consequently, forecasts for 2023–2024 assumed only a gradual, mild increase in passenger numbers compared to pre-crisis levels. The initial phase of the pandemic caused a sharp decline in passenger traffic, reaching around 86% in April 2020 compared to March of the same year. The recovery process began in 2021 and, in Norway, it was more dynamic than in Sweden. Seasonal fluctuation amplitudes were more pronounced, and differences between forecasted and actual values decreased more rapidly. From mid-2023 onwards, both series converged significantly, which can be interpreted as a sign of the Norwegian market steadily returning to the pre-pandemic growth scenario. This supports the conclusion that the dominance of domestic flights and Norway’s specific geographic conditions made the market relatively less vulnerable to the effects of restrictions on international travel. The comparison of forecasted and actual values for Norwegian passenger air transport is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Comparison of model forecasts with the actual number of air transport passengers in Norway.

For this model as well, there is no basis to reject the hypothesis of normality of residuals. The Shapiro–Wilk test statistic (W) was 0.988 with a p-value = 0.505. The AIC value of 2442.7 confirms that the applied model achieves an appropriate balance between goodness of fit and the complexity of its parametric structure. The R2 for this model reached 0.9878. Moreover, the error metrics ME, MAE, and RMSE, similarly to MAPE, also confirm the high accuracy of the forecasts (Table 5).

Table 5.

Assessment of forecast accuracy in the Holt–Winters model for the Norwegian market.

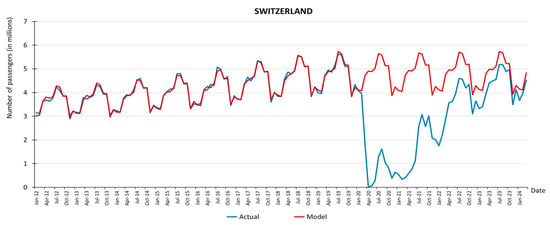

The last of the models developed in this study concerned the Swiss market, with parameters set at α = 0.4, δ = 0.1, γ = 0.1, yielding a MAPE of approximately 1.43%. A comparison of the forecasted and actual values shows that the Swiss air transport market, similar to Portugal, was heavily dependent on international travel, which led to a sharp collapse immediately after the outbreak of the pandemic. This is confirmed by the difference in the number of passengers carried, which reached 3.94 million during the February–April 2020 period. In 2021–2022, despite visible signs of market recovery, actual passenger traffic remained significantly below the levels projected in a no-disruption scenario. At the beginning of 2023, there was a clear improvement, and from October of the same year, actual values nearly matched the forecasts. This indicates that the Swiss market had returned to its model development trajectory, thereby restoring the potential implied by its pre-pandemic condition. As observed, COVID-19 clearly impacted passenger air transport in Switzerland, mainly due to restrictions on international travel. However, the strong service-based economy, high purchasing power of citizens, and institutional stability contributed to a relatively rapid return to forecasted levels, as illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Comparison of model forecasts with the actual number of passengers in Switzerland.

As with the other developed models, the Shapiro–Wilk test was performed, yielding W = 0.981 and a p-value = 0.175. The AIC was 2509.1, indicating a complexity similar to that of the previously analyzed models. This model achieved an R2 of 0.98738. Additionally, the ME, MAE, and RMSE values were calculated, confirming the high accuracy of the forecasts (Table 6).

Table 6.

Assessment of forecast accuracy in the Holt-Winters model for the Swiss market.

The Holt-Winters method proved effective in modeling passenger numbers on the selected aviation markets, achieving very low error values, as evidenced by MAPE below 2% in all cases. Moreover, across all countries the R2 values exceeded 0.98, indicating a consistently high alignment between the fitted and observed series. Up to March 2020, the forecasts closely matched the actual data, after which significant and country-specific discrepancies emerged. The pandemic had a greater impact in countries with a higher share of international traffic (Portugal, Switzerland), while markets with a strong domestic network, such as Norway and Sweden, proved more resilient. Among the analyzed countries, Poland was positioned in the middle, combining a sharp decline with the forecasted growth potential. The models and results presented in this section form the basis for further analysis, including estimating losses, assessing the extent of recovery and pace of restoration of individual markets.

4.3. Robustness Check and Comparison of Alternative Models

To strengthen the empirical framework and verify the stability of the results, several additional forecasting approaches were estimated alongside the multiplicative Holt–Winters model. The aim of this part of the research was to assess whether the long-term projections used in the study are sensitive to the choice of forecasting method, or whether similar patterns emerge when applying alternative models. For this purpose, four commonly used approaches were considered:

- seasonal ARIMA model (SARIMA);

- basic structural model (BSM);

- trend–seasonal linear model (TSLM);

- Random Forest model (RF).

All models were trained on the same pre-pandemic period and evaluated using identical forecast accuracy metrics to ensure full comparability (Table 7).

Table 7.

Forecast accuracy metrics for the examined models.

It should be noted that the MAPE values obtained for the benchmark models are relatively high. This results from the fact that, during the pandemic collapse, actual passenger numbers fell to very low levels, which significantly inflates percentage errors. Similar behavior of MAPE in periods with near-zero observations is well documented in forecasting research [69,70,71]. For this reason, the comparison focuses on the relative differences between the models rather than on the absolute size of the MAPE values.

The benchmarking results indicate that some alternative models, particularly BSM and Random Forest, achieved lower error values. However, the objective of the comparison was not to select the single most accurate algorithm, but to verify whether the general behavior of the examined markets remains consistent across different forecasting techniques. In this respect, the Holt–Winters method offers several practical advantages: it provides a clear decomposition of trend and seasonality, can be applied consistently across all analyzed markets without extensive model-specific adjustments, and generates stable long-term forecasts suitable for comparative analysis.

Overall, despite differences in accuracy metrics, all models produced highly consistent qualitative patterns, both in terms of the magnitude of the COVID-19 impact and the overall pattern of recovery observed across air passenger transport markets. This confirms that the key findings of the study are robust and do not depend on the specific forecasting method applied. As a result, Holt–Winters remains the primary analytical model in this study, while the benchmarking results are reported to ensure methodological transparency and to support confidence in the results.

4.4. Comparative Analysis of Losses and Recovery of Markets

The final stage of the study involved analyzing and interpreting the results obtained from the developed models to assess and compare the condition of selected aviation markets disrupted by the epidemic-driven crisis. Forecasts generated using the Holt-Winters method were used to determine both the losses in the number of carried passengers (Lm) and the extent of their recovery (Rm) across successive time intervals (m) following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. The results indicate significant variation among the analyzed markets.

In the initial period, covering the first three months of the crisis, passenger losses ranged from 7.82 million in Sweden to 13.54 million in Portugal. Poland, with a figure of 10.91 million, fell in the intermediate group between Norway (8.22 million) and Switzerland (12.64 million). This differentiation persisted in subsequent time intervals, with the fastest accumulation of losses observed in Portugal and Switzerland, while lower losses occurred in Sweden and Norway. One year after the outbreak, cumulative losses exceeded 30 million passengers in all countries, with the highest recorded in Portugal (53.87 million) and Switzerland (48.45 million). Poland, at 44.45 million, was slightly below this group, while Sweden and Norway reached 30.84 million and 32.88 million, respectively. These findings indicate that markets more dependent on international travel and tourism experienced a greater passenger deficit relative to projected demand, primarily due to prevailing restrictions (e.g., entry requirements, health regulations) and the resulting decline in societal mobility. Conversely, the Scandinavian countries, with a significant share of domestic travel and an extensive internal network, were less affected by the crisis. The reduced sensitivity of these markets to international passenger flow restrictions translated into lower losses and positively influenced the initial phase of passenger traffic recovery.

Equally important from the perspective of market health are the observations regarding the extent of loss recovery (Rm). After three months, Norway recorded the highest extent of recovery at 18.83%, while Poland reached 10.16%. After six months, Norway maintained its lead (21.16%), whereas Poland and Switzerland showed similar values of around 15–16%. For Portugal and Sweden, despite Portugal experiencing a larger passenger deficit—13.6 million more than Sweden—the difference in extent of recovery remained below two percentage points (14.85% and 12.82%). One year after the pandemic outbreak, the Rm indicator remained relatively low across all countries (13.9% to 20.6%), reflecting the persistent demand barrier caused by mobility restrictions. A clear acceleration became visible only in the second year: between the 18th and 24th month, all markets recorded an increase of around 7 pp. Two years after the outbreak, the Norwegian market demonstrated the highest capacity for loss recovery. Poland, despite a delayed start, achieved the largest overall increase—from 10.16% to 27.11% (+16.95 pp.). This confirms the Polish market’s ability to effectively compensate for lost volume, supported by deferred demand and restored airport throughput. Portugal and Switzerland, despite experiencing the highest losses and having substantial market potential, did not translate seasonal rebounds into higher extent of recovery, reaching only 26.62% and 27.01%, respectively. Sweden, despite a relatively low passenger deficit (52.94 million), exhibited the weakest extent of recovery, reaching 24.59% after two years. The contrast with Norway, whose losses were only about 6 million higher, but extent of recovery reached 29.34%, illustrates how markets with similar traffic profiles may follow different recovery dynamics. In Sweden’s case, this likely reflects a more gradual demand response and weaker seasonal rebounds compared to Norway.

A summary of passenger losses and recovery levels across the analyzed markets is presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Crisis-related losses based on predicted values obtained by models.

Next, the actual passenger transport results in the months following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic were compared with data from January 2020 (JAN-2020 = 100%), which allowed for the assessment of the pace of restoration of passenger air transport markets in the selected European countries. The results obtained in this way were further visualized by assigning appropriate colors to the percentage values (Dz), as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the pace of restoration of selected passenger air transport markets, visualized using color mapping.

As shown in Figure 9, all the analyzed air transport markets experienced a similar cycle, encompassing a sharp collapse, partial restoration, and then a return to stability near pre-pandemic levels, taking January 2020 passenger traffic as the baseline. The differences that emerged were mainly related to the intensity of the process and typically amounted to shifts of 1–2 months between individual phases, confirming that each European country was equally exposed to the unprecedented crisis in passenger aviation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. It is worth noting that Poland, in many periods, achieved results comparable to—or even higher than—other economically stronger countries. At the same time, these developments took place within a sector that is also being shaped by longer-term climate-policy and decarbonization efforts.

The initial collapse in spring 2020 affected all countries, with passenger air traffic almost completely halted. In April 2020, the Dz index stood at only 0.5% in Poland, 0.75% in Switzerland, and 0.94% in Portugal, while conditions were slightly better in the Scandinavian markets. In the subsequent months of 2020, a partial restoration occurred, particularly in August, when Poland and Portugal reached approximately 57% of the pre-pandemic reference level, while Norway and Sweden remained below 40% and Switzerland below 30%. This was the first indication of the Polish market’s strong responsiveness to seasonal restoration of air traffic. The following year, 2021, was marked by high volatility and clear differences between countries. In July, Poland reached over 85%, and in August nearly 99% of January 2020 traffic levels, indicating an almost full summer restoration. For comparison, Portugal recorded 70–99%, Switzerland 63–75%, and Norway and Sweden 54–58%. This confirms that Poland belonged to the markets with particularly high restoration levels, surpassing even the Scandinavian countries and Switzerland. During the winter of 2021–2022, all markets again fell to 40–70%, following a similar pattern. In 2022, the restoration process intensified. By May, the Polish market had exceeded the 100% threshold (106.77%), and in July and August reached around 145%. In the same months, the highest values were observed in Portugal (142–166%), while Norway recorded 109–125%, Sweden 97–109%, and Switzerland 89–113%. Thus, 2022 demonstrated that Poland was among the countries with the strongest restoration dynamics, matching markets supported by strong domestic traffic or high tourism potential. Results for 2023 and Q1 2024 reflect the stabilization of European passenger aviation. Poland maintained values above 105% for most months, frequently exceeding 150% (June–September 2023). The situation was even more favorable in Portugal, where the Dz index repeatedly surpassed 110%, often exceeding 160% (May–October 2023). During this period, Norway generally ranged between 90 and 130%, Sweden stabilized at 85–120%, and Switzerland remained within 95–127%.

The cross-country differences in the observed market dynamics after the pandemic outbreak can be partly explained by structural characteristics of the analyzed air transport systems. Norway and Sweden benefited from extensive domestic networks, which helped stabilize passenger volumes during periods of strict international travel restrictions. In contrast, Portugal and Switzerland were more exposed to international and tourism-driven demand, resulting in deeper initial declines and a slower return to pre-pandemic levels. Poland occupies an intermediate position: although domestic traffic plays a smaller role than in Scandinavia, this market combines diversified leisure, visiting-friends-and-relatives (VFR) and business demand with a strong presence of low-cost carriers. Taken together, these structural characteristics help account for the comparatively rapid improvement of the Polish market once pandemic-related travel restrictions were eased.

Considering all the obtained results, it can be concluded that the Polish passenger air transport market occupies a strong position within Europe and in recent years has clearly asserted its growing role in the region. A performance similar to that of economically stronger markets in the post-COVID-19 period demonstrates not only the flexibility of demand but also the effectiveness of measures undertaken by transport organizers, carriers, and airports. The epidemic crisis at the time proved to be critically impactful for passenger aviation, yet it simultaneously showed that Poland not only met the challenges but also joined the group of countries that managed to restore their transport capacity within a short period. At the same time, this experience highlights the need to strengthen the sector’s resilience by developing recommendations and solutions that will enable effective responses to similar threats in the future.

A comparison of the five chosen markets indicates that the ways in which they reconstructed their passenger volume were closely associated with short-term crisis conditions such as the stabilizing effect of extensive domestic networks in Norway and Sweden or the relatively rapid reinstatement of leisure- and VFR-oriented capacity in Poland. In turn, longer-term structural characteristics, including the strong reliance on international traffic in Portugal and Switzerland, were more important for explaining both the extent of loss recovery and the pace at which markets restored pre-pandemic traffic levels. These observations help contextualize the practical recommendations.

Given the resilience patterns observed across all analyzed markets, several practical directions for policymakers and the aviation sector emerge from the comparative results:

- strengthening domestic and regional connectivity, which contributed to a faster pace of restoration in markets with more diversified demand structures;

- enhancing the operational flexibility of airlines and airports, allowing for rapid adjustments to sudden fluctuations in traffic volumes;

- maintaining adequate airport capacity reserves and intermodal accessibility, which facilitate a quicker scaling-up of operations once mobility restrictions are eased;

- developing clear and coordinated crisis-management procedures, helping stabilize connectivity during periods of severe disruption.

5. Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly affected the functioning of passenger aviation, initially causing sharp declines in carried passenger volumes and subsequently forcing the process of market recovery. The publication assessed the condition of passenger air transport in Poland relative to selected European countries in the context of disruptions caused by the pandemic, using the Holt–Winters method to forecast passenger transport outcomes. The conducted study not only enabled the identification of the scale of incurred losses and the determination of the extent of their recovery based on forecasts obtained from the models but also allowed for the assessment of the pace of restoration in individual markets. The results showed that Poland, like other European countries, experienced a severe collapse in passenger air traffic during the initial phase of the pandemic. At the same time, however, the extent of loss recovery and the pace of market restoration in the following years proved comparable to those observed in stronger European economies. All markets included in the study recorded a significant deficit in the number of handled passengers during the first months of the pandemic, with the largest declines observed in Portugal and Switzerland—countries more dependent on international and tourism-related traffic. In contrast, the Scandinavian markets, characterized by a high share of domestic flights, demonstrated greater stability and returned to the growth path more quickly. Poland ranked in the middle of the comparison, with a passenger deficit of approximately 44.5 million after the first year of the pandemic. Nevertheless, the analysis of loss recovery showed that despite an initially delayed response, the Polish market achieved the highest increase in the Rm indicator across all cases (+16.95 pp), confirming its capacity to compensate for the lost volume in the medium term. Moreover, the assessment of the pace of restoration revealed that Poland, in many periods, achieved results comparable to—and sometimes exceeding—those of other countries. Since spring 2023, similarly to Portugal, Poland has not only fully restored its January 2020 passenger transport level but has also exceeded it for several consecutive months, which constitutes a highly positive signal for the condition of the Polish passenger aviation sector in the post-pandemic context. In summary, it can be concluded that Poland’s role within the European air transport system continues to strengthen. These post-pandemic developments in passenger air transport should also be perceived in the context of a wider structural shift in the aviation sector, where long-term climate policy and decarbonization processes are gradually redefining the conditions under which European air transport develops. At the same time, this study—based on the challenging experience of the COVID-19 pandemic—clearly suggests that, beyond the growing passenger volume, equal importance should be placed on enhancing market resilience through coordinated actions of policymakers and operators aimed at shaping transport policies to prepare for future crises of a similar nature.

The contribution of the study can be summarized in several areas. First, the analysis applies the same forecasting approach to a group of European aviation markets that differ in size and structure, which allows long-term changes in passenger traffic to be examined in a comparable manner. Second, the use of pre-pandemic trend and seasonal patterns makes it possible to estimate the scale of passenger losses caused by COVID-19 and to assess both the extent of recovery and the pace of market restoration. Third, the comparison of markets shows that recovery trajectories are shaped not only by the depth of the initial decline but also by structural characteristics, such as market orientation or the role of domestic traffic. In this respect, the study extends previous work that has usually focused on individual markets or shorter time horizons.

From a practical perspective, this study provides valuable insights for infrastructure development planning, transport strategy formulation, and the strengthening of passenger aviation resilience to future crises. Above all, the results confirm the growing importance of Poland as a transport hub in Europe, which has significant implications for the continued development of infrastructure and the operational policy of the national carrier. In the longer term, one of the key factors that could help consolidate this position is the implementation of the Central Communication Port (CPK) project. The construction of CPK may overcome existing infrastructural constraints that limit the number of air operations and, consequently, the overall transport performance. By increasing capacity and improving connectivity, this investment could substantially enhance market competitiveness and stimulate further growth in passenger transport, thereby strengthening the aviation sector as well as related industries. Secondly, the analysis highlighted that market resilience depends not only on its scale but also on its structure. It demonstrated that a higher share of domestic flights can reduce vulnerability to global epidemic-related disruptions. Furthermore, the study emphasizes the need to develop comprehensive crisis management strategies, including diversification of route networks, implementation of epidemic risk management procedures, and a stronger role of the state in ensuring the stability of the air transport market.

The study has several limitations. The applied Holt–Winters method made it possible to develop highly accurate models that very effectively capture the trends and seasonality present in time series. However, it should be noted that the proposed models are based solely on historical data on the number of passengers carried, omitting significant economic and social variables such as air ticket prices, GDP level, or unemployment rate.

At the same time, the modeling framework does not explicitly incorporate broader socioeconomic determinants, such as income dynamics, labor market stability, the stringency of mobility restrictions or ticket price evolution, which may substantially shape both the depth of pandemic-related losses and the rate of recovery. Their inclusion in future research would enable a more multidimensional explanation of cross-country differences and deepen the analytical interpretation of resilience patterns. They also do not account for extraordinary factors such as armed conflicts, economic crises, or changes in tourist preferences, which could significantly influence passenger behavior and transport demand. Moreover, although the study compares Poland with a group of four other European markets, this set does not fully represent the diversity of pandemic impacts observed across the continent. While the chosen countries provide a structurally varied set of reference cases that differ in their domestic traffic shares, international orientations and long-term demand drivers, several other types of European aviation systems may nevertheless have experienced distinct post-pandemic dynamics—for example, those characterized by substantially different traffic scales, pronounced tourism-driven seasonality or very small national markets. As a result, the conclusions drawn in this study should be generalized with caution to countries whose scale or structural characteristics fall outside the range represented here. Additional markets were not included because only a limited number of European countries met all methodological requirements, namely full availability and internal consistency of data, comparable passenger volumes in the years immediately preceding the COVID-19 pandemic, and the ability to represent distinct aviation system configurations. Overall, these limitations do not undermine the credibility of the present results but rather define the scope and applicability of the study’s conclusions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.; methodology, S.S. and A.B.; software, S.S.; validation, A.B.; formal analysis, S.S. and A.B.; investigation, S.S.; resources, S.S. and A.B.; data curation, S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, S.S. and A.B.; visualization, S.S.; supervision, A.B.; project administration, S.S.; funding acquisition, A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| ARIMAX | Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average with Exogenous variables |

| BSM | Basic Structural Model |

| BSTS | Bayesian Structural Time Series |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| DWT | Discrete Wavelet Transform |

| EBITDA | Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization |

| EU | European Union |

| ETS | Emissions Trading System |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| IATA | International Air Transport Association |

| LightGBM | Light Gradient Boosting Machine |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| ME | Mean Error |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| PLL LOT | LOT Polish Airlines |

| PM | Poisson Model |

| QPM | Quasi-Poisson Model |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| SARIMA | Seasonal Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| SAS | Scandinavian Airlines |

| SAF | Sustainable Aviation Fuels |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| SWISS | Swiss International Air Lines AG |

| TAP | Transportes Aéreos Portugueses |

| TSLM | Trend–Seasonal Linear Model |

| USA | United States of America |

| VFR | Visiting-friends-and-relatives |

References

- Izdebski, M.; Michalska, A.; Jacyna-Gołda, I.; Gherman, L. Prediction of Cyber-Attacks in Air Transport Using Neural Networks. Eksploat. I Niezawodn.—Maint. Reliab. 2024, 26, 191476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barczak, A. COVID-19 Pandemic—Financial Consequences for Polish Airports—Selected Aspects. Aerospace 2021, 8, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białek-Szwed, O. Everyday Life During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Perspective of Contemporary Polish Press. Ann. Soc. Sci. KUL 2021, 13, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Monterde-i-Bort, H.; Sucha, M.; Risser, R.; Kochetova, T. Mobility Patterns and Mode Choice Preferences during the COVID-19 Situation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobczuk, S. Transport in the tourist services sector in Poland during the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. WUT J. Transp. Eng. 2024, 138, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huderek-Glapska, S.; Antczak, D. Attitudes of Airline Passengers under Uncertainty—A Case Study of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2024, 124, 102734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers, S.; Rundshagen, V. European Airlines′ Strategic Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic (January–May, 2020). J. Air Transp. Manag. 2020, 87, 101863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukulski, J.; Lewczuk, K.; Góra, I.; Wasiak, M. Methodological Aspects of Risk Mapping in Multimode Transport Systems. Eksploat. I Niezawodn.—Maint. Reliab. 2023, 25, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-C.; Shih, T.-P.; Ko, W.-C.; Tang, H.-J.; Hsueh, P.-R. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19): The Epidemic and the Challenges. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, H.; Wang, K.; Zhan, Y.; Bian, L. Measuring imported case risk of COVID-19 from inbound international flights. A case study on China. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2020, 89, 101918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN World Tourism Organization. Overview of COVID-19 Related Travel Restrictions as of 1 June 2021. COVID-19 Related Travel Restrictions. A Global Review for Tourism. Available online: https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2021-07/210705-travel-restrictions.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Lim, D. Travel Bans and COVID-19. Ethics Glob. Politics 2021, 14, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortall, R.; Mouter, N.; Van Wee, B. COVID-19 Passenger Transport Measures and Their Impacts. Transp. Rev. 2021, 42, 441–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Schweiggart, N. Two Years of COVID-19 and Tourism: What We Learned, and What We Should Have Learned. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 915–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, T.L.; Winter, S.R.; Rice, S.; Ruskin, K.J.; Vaughn, A. Factors That Predict Passengers Willingness to Fly during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2020, 89, 101897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöwer, M.; Hopkins, D.; Allen, M.; Higham, J. An Analysis of Ways to Decarbonize Conference Travel after COVID-19. Nature 2020, 583, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenda, K.W. Connecting Through Technology During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic: Avoiding “Zoom Fatigue”. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 437–438. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Wandelt, S.; Zhang, A. How Did COVID-19 Impact Air Transportation? A First Peek through the Lens of Complex Networks. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2020, 89, 101928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borucka, A.; Parczewski, R.; Kozłowski, E.; Świderski, A. Evaluation of Air Traffic in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Arch. Transp. 2022, 64, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drop, N.; Bohdan, A. Application of the Holt–Winters Model in the Forecasting of Passenger Traffic at Szczecin–Goleniów Airport (Poland). Sustainability 2025, 17, 6407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barczak, A.; Dembińska, I.; Rozmus, D.; Szopik-Depczyńska, K. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Air Transport Passenger Markets-Implications for Selected EU Airports Based on Time Series Models Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozicki, B.; Skrabacz, A.; Gałek, B.; Lorek, M. Multidimensional Analysis of Losses in the Number of Passengers Transported by Air in Poland and Germany Caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic in Terms of the Maintenance of Economic Security. J. Sustain. Dev. Transp. Logist. 2023, 8, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolle, B. Stochastic Modelling of Air Passenger Volume during the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Financial Impact on German Airports. Fortune J. Health Sci. 2024, 7, 418–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzo Vieira, J.P.; Vieira Braga, C.K.; Pereira, R.H.M. The Impact of COVID-19 on Air Passenger Demand and CO2 Emissions in Brazil. Energy Policy 2022, 164, 112906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, Y.; Olariaga, D.O. Air Traffic Demand Forecasting with a Bayesian Structural Time Series Approach. Period. Polytech. Transp. Eng. 2023, 52, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.B.; Yu, J.; Lin, B.; Geng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Lin, T.; Xiao, F. Airport Terminal Passenger Forecast under the Impact of COVID-19 Outbreaks: A Case Study from China. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 65, 105740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultekin, N.; Acik Kemaloglu, S. Evaluation of the Impact of COVID-19 on Air Traffic Volume in Turkish Airspace Using Artificial Neural Networks and Time Series. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsson, S.V.; Cattaneo, M.; Redondi, R. Forecasting Temporal World Recovery in Air Transport Markets in the Presence of Large Economic Shocks: The Case of COVID-19. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2021, 91, 102007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- To, W.M.; Lee, P.K.C. Modeling of the COVID-19 Impact on Air Passenger Traffic in the US, European Countries, and China. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2024, 115, 102556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wandelt, S.; Fricke, H.; Rosenow, J. The Impact of COVID-19 on Air Transportation Network in the United States, Europe, and China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, P.-F.; Chiu, C.-S. Airline Transportation and Arrival Time of International Disease Spread: A Case Study of COVID-19. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokadjo, Y.M.; Atchadé, M.N. The influence of passenger air traffic on the spread of COVID-19 in the world. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 8, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; de Groot, M.; Bäck, T. Using Forecasting to Evaluate the Impact of COVID-19 on Passenger Air Transport Demand. Decis. Sci. 2021, 54, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte-Fischedick, M.; Shan, Y.; Hubacek, K. Implications of COVID-19 Lockdowns on Surface Passenger Mobility and Related CO2 Emission Changes in Europe. Appl. Energy 2021, 300, 117396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burbidge, R. Adapting Aviation to a Changing Climate: Key Priorities for Action. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2018, 71, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.A.; Mamun, A.A.; Rahman, S.M.; Malik, K.; Al Amran, M.I.U.; Khondaker, A.N.; Reshi, O.; Tiwari, S.P.; Alismail, F.S. Climate Change Mitigation Pathways for the Aviation Sector. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, R.; Guzman, A.F. A Perspective on Emerging Energy Policy and Economic Research Agenda for Enabling Aviation Climate Action. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 117, 103725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fageda, X.; Teixidó, J.J. Pricing Carbon in the Aviation Sector: Evidence from the European Emissions Trading System Pricing Carbon in the Aviation Sector: Evidence from the European Emissions Trading System. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2021, 111, 102591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency. Fit for 55 and ReFuelEU Aviation. Available online: https://www.easa.europa.eu/en/light/topics/fit-55-and-refueleu-aviation (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Afşar, B.; Bilgiç, H.B.; Emen, M.; Zarifoğlu, S.; Acar, S. Analyzing the EU ETS, Challenges and Opportunities for Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions from the Aviation Industry in Europe. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiaas, A.M. The EU ETS and Aviation: Evaluating the Effectiveness of the EU Emission Trading System in Reducing Emissions from Air Travel. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2021, 9, 84–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dray, L.; Schäfer, A.W.; Grobler, C.; Falter, C.; Allroggen, F.; Stettler, M.E.J.; Barrett, S.R.H. Cost and Emissions Pathways towards Net-Zero Climate Impacts in Aviation. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 956–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]