The Impact of Controversial Events on Corporate Resilience: The Chain-Mediating Role of ESG and Value-at-Risk

Abstract

1. Introduction

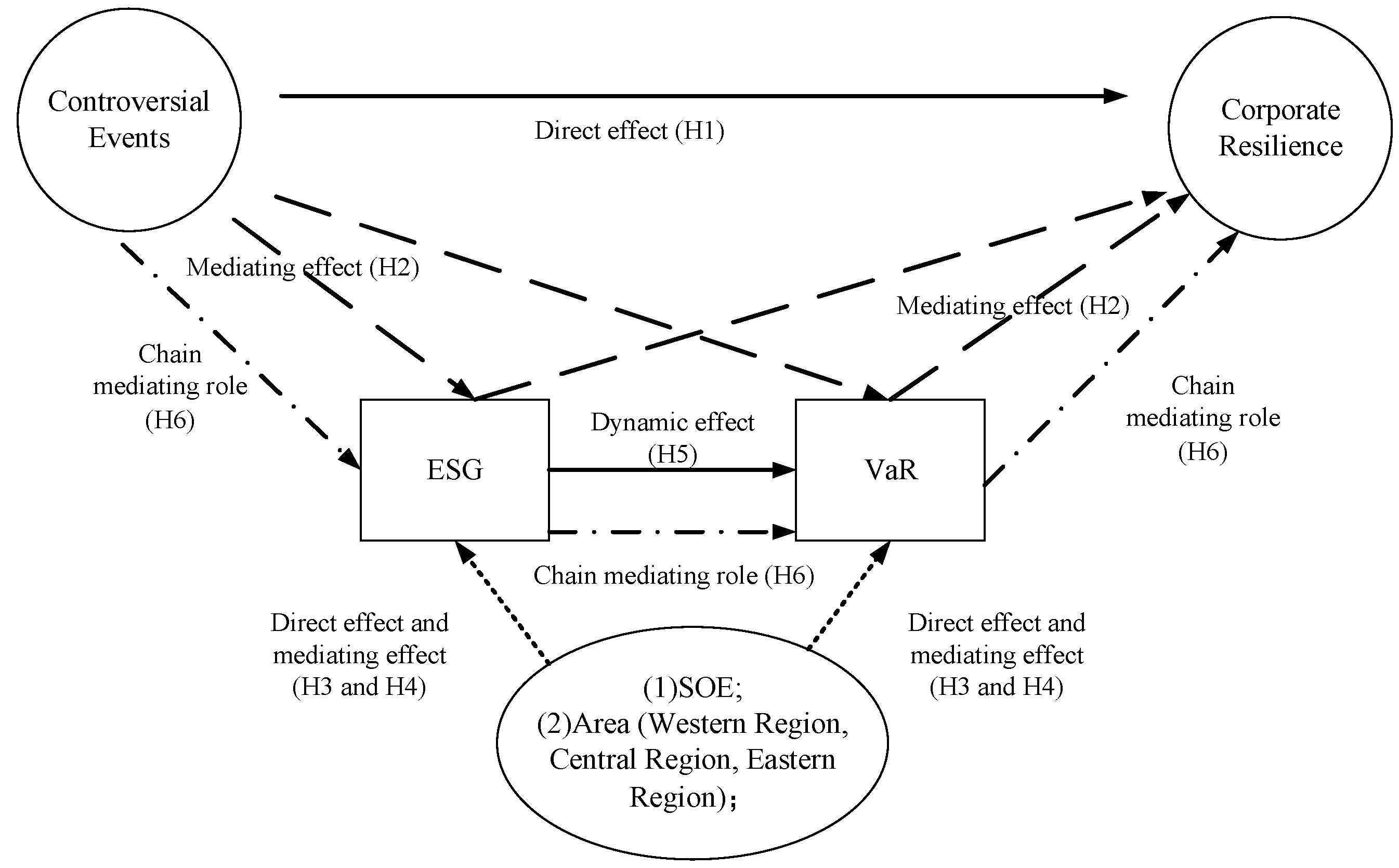

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Controversial Events and Corporate Resilience

2.2. The Mediating Effects of ESG and VaR

2.3. Corporate Ownership and Regional Differences

2.4. ESG, VaR and the Chain-Mediating Role

2.5. Gaps in Existing Literature and Research Contributions

3. Data and Model Building

3.1. Data Sources and Sample Selection

3.2. Variable Definitions and Descriptions

3.2.1. Dependent Variable: Corporate Resilience

3.2.2. Independent Variable: Controversial Events

3.2.3. Mediating Variables: ESG and VaR

- 1.

- ESG Ratings.

- 2.

- Value-at-Risk.

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.3. Methodology

3.3.1. Model Implementation and Parameter Settings

3.3.2. The Double Machine Learning Model

3.3.3. The Generalized Additive Model

3.3.4. The Total Indirect Effect

4. Results

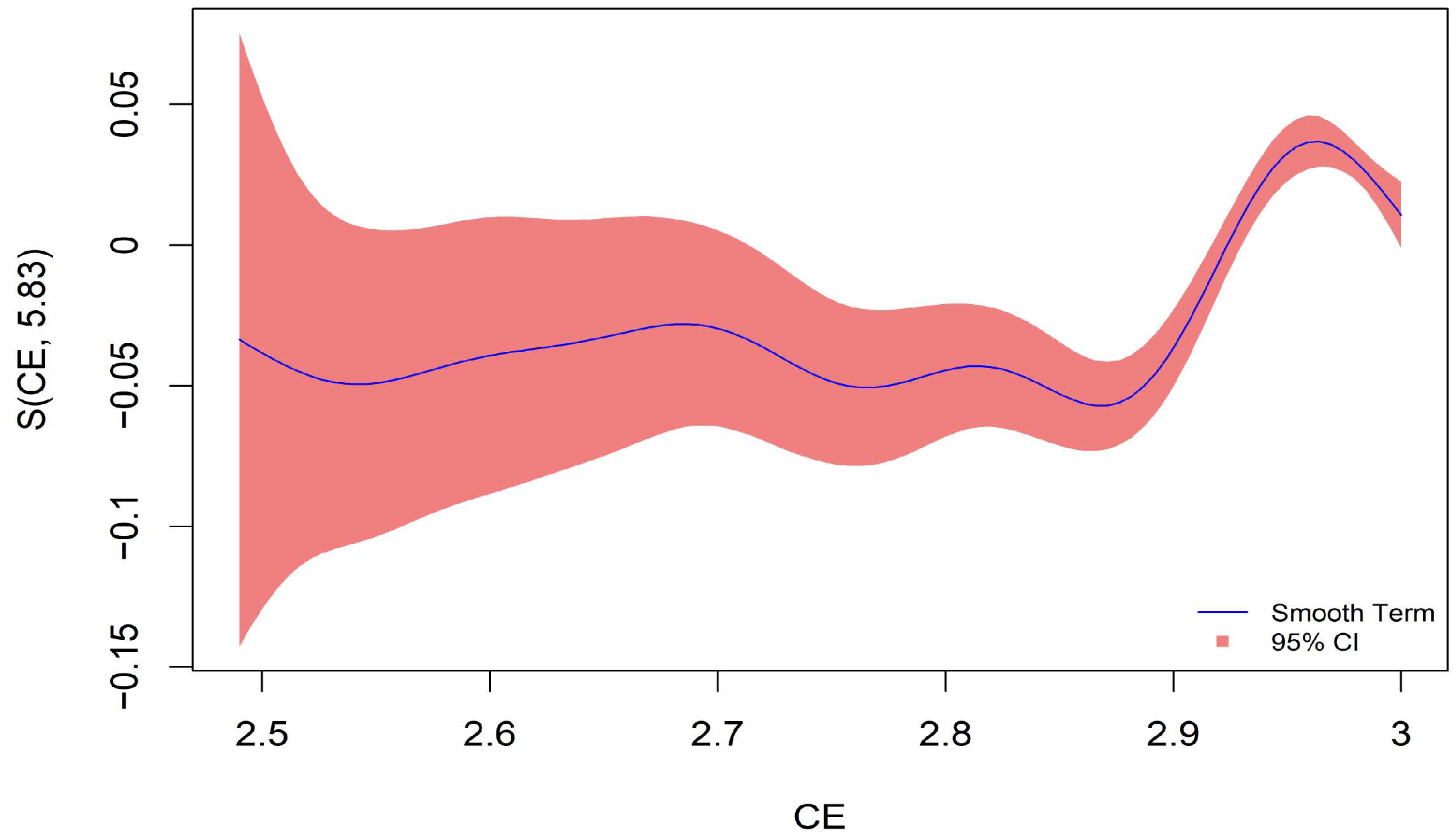

4.1. H1 Test Results: The Non-Linear Impact of Controversial Events

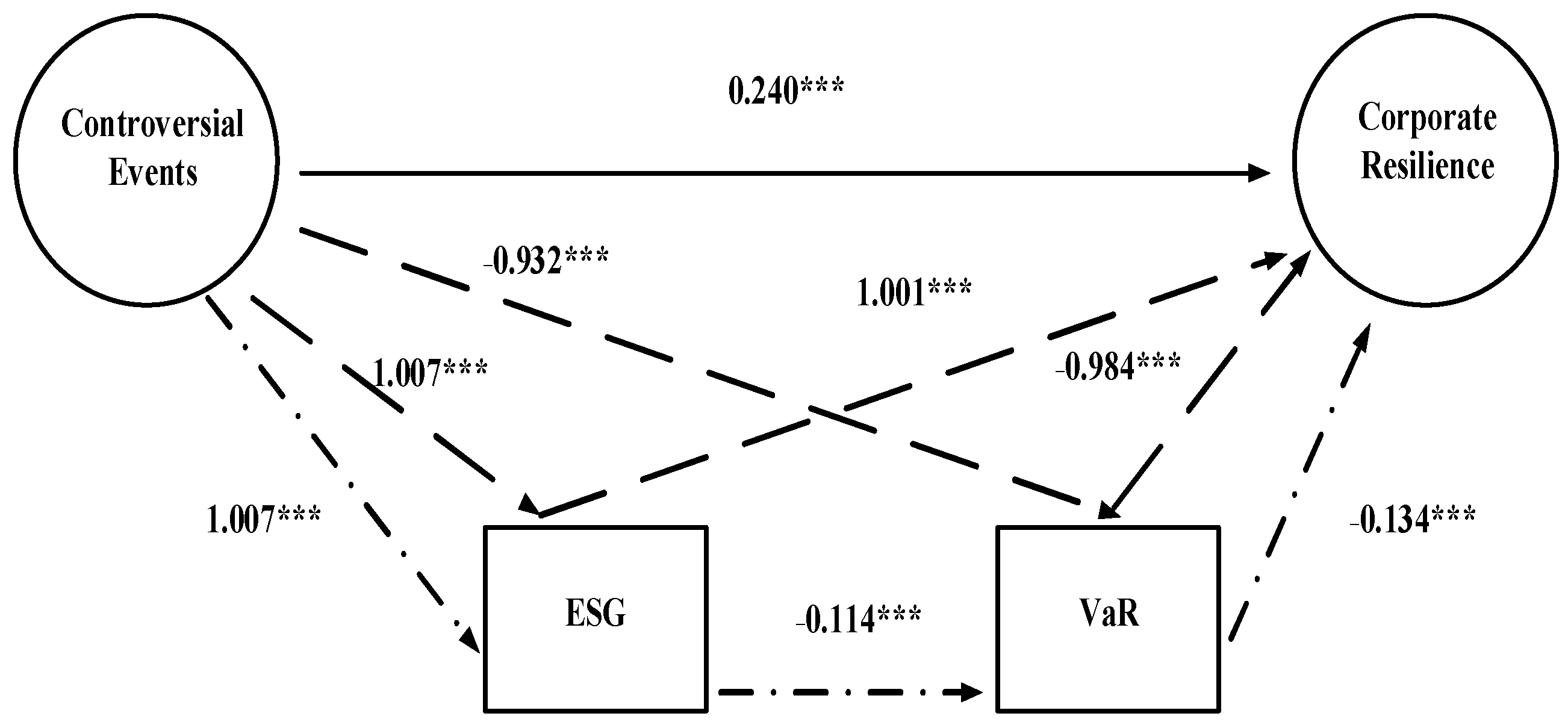

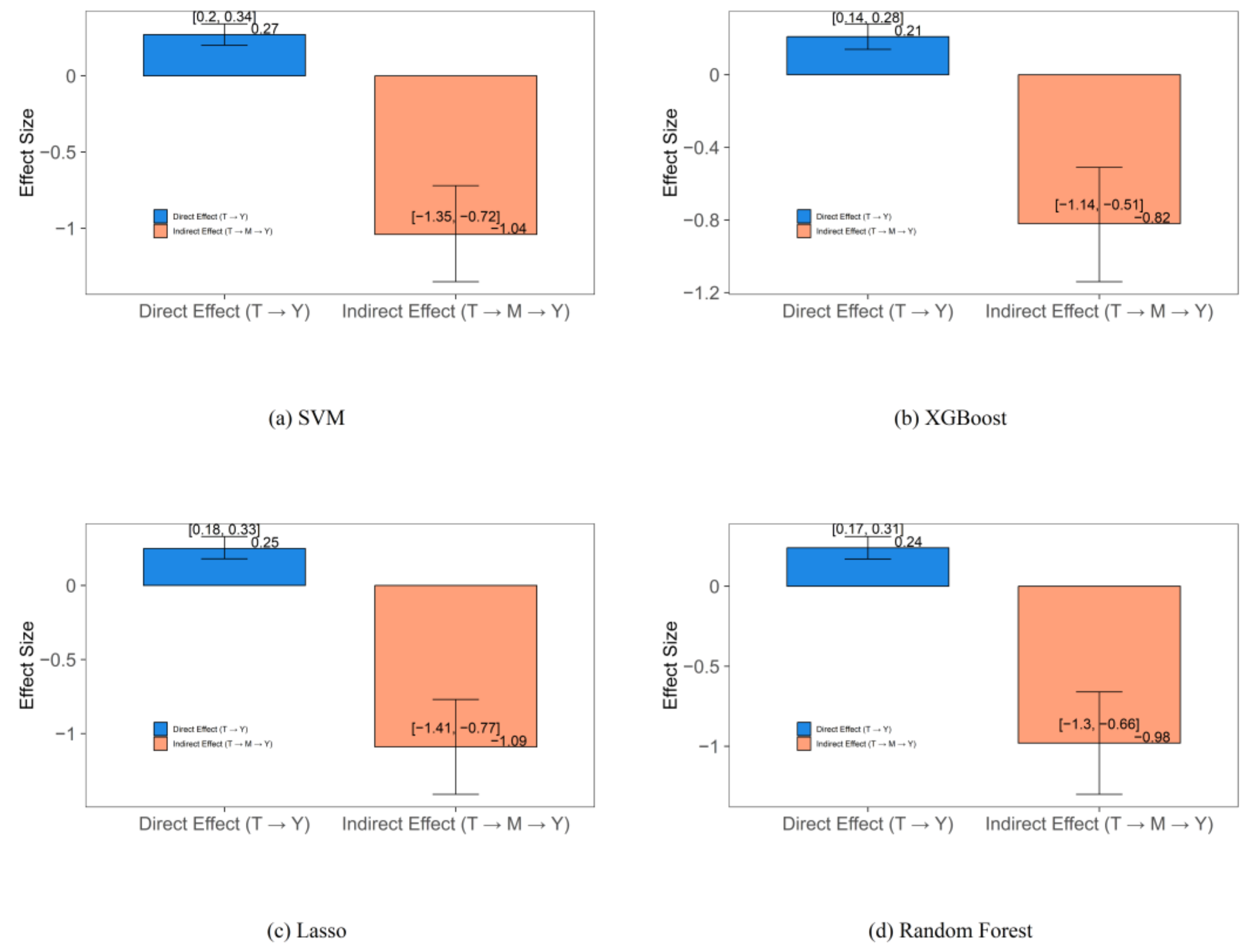

4.2. H2 Test Results: The Chain-Mediating Role of ESG and VaR

4.3. H3 and H4 Test Results: Heterogeneity Analysis

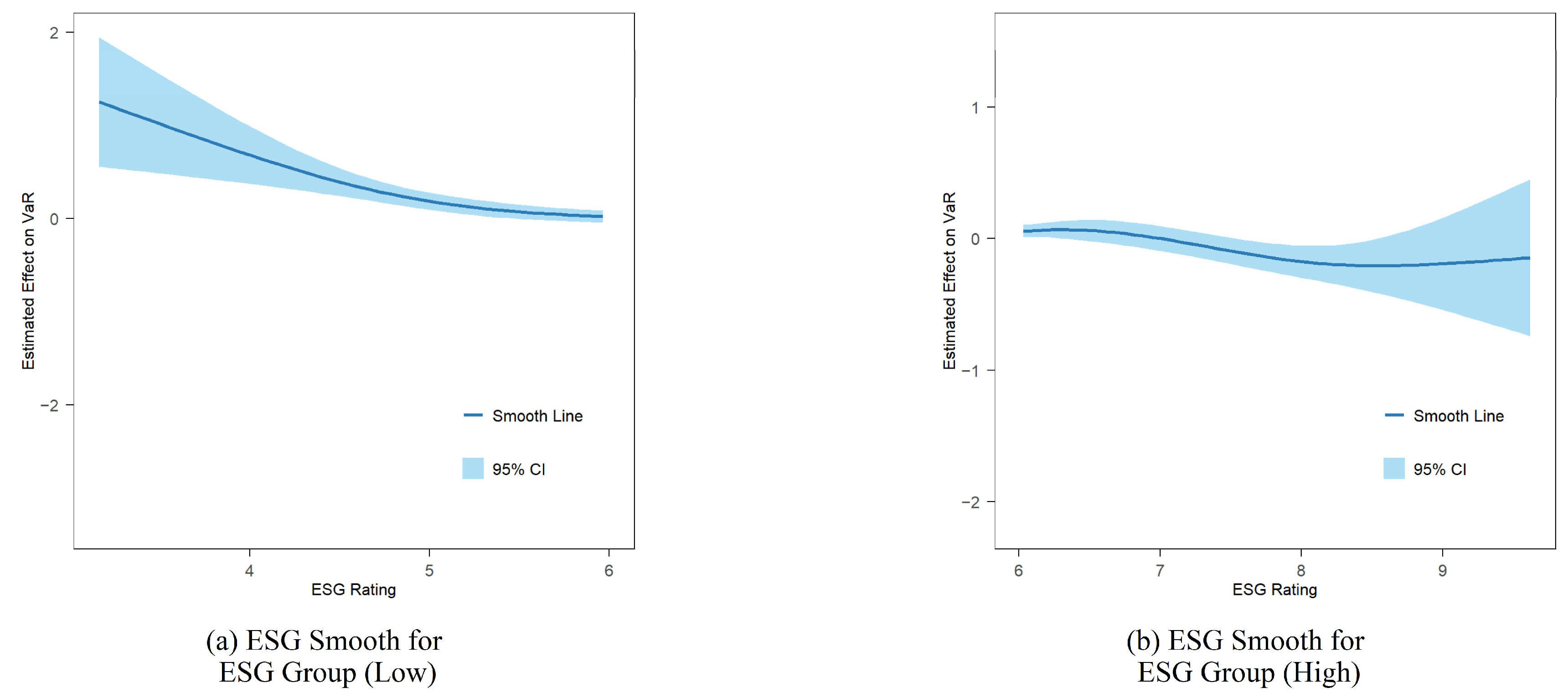

4.4. H5 Test Results: The Impact of ESG on VaR

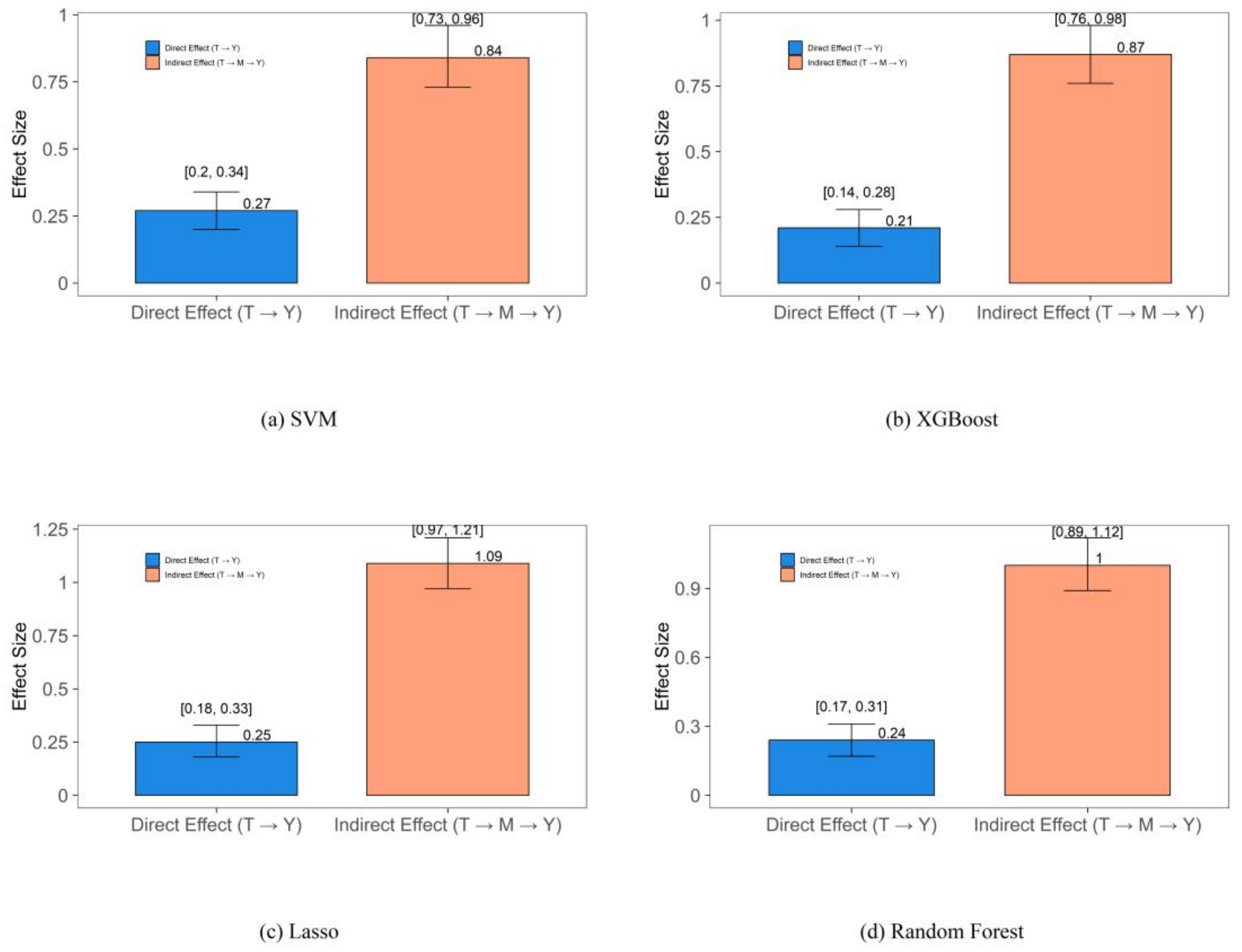

4.5. H6 Test Results: Total Indirect Effects

4.6. Robustness Test and Endogeneity Test

- Moderating Effect of Corporate Ownership and Industry Characteristics.

- 2.

- Adjusting Sample Partition Size.

- 3.

- Mediation Test of Quadratic Term Method with Control Variables.

- 4.

- Endogeneity Test: Instrumental Variable Approach.

| Panel | Algorithm | Effect | Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | Pr (>|t|) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A | Random Forest | Direct | 0.240 | 0.036 | 6.698 | 0.000 |

| Mediating (ESG) | 1.001 | 0.058 | 17.180 | 0.000 | ||

| Mediating (VaR) | −0.984 | 0.163 | −6.044 | 0.000 | ||

| Panel B | Random Forest | Direct | 0.235 | 0.036 | 6.548 | 0.000 |

| Mediating (ESG) | 1.001 | 0.058 | 17.260 | 0.000 | ||

| Mediating (VaR) | −0.996 | 0.163 | −6.119 | 0.000 | ||

| Panel C | Random Forest | Direct | 0.237 | 0.036 | 6.647 | 0.000 |

| Mediating (ESG) | 0.990 | 0.058 | 17.080 | 0.000 | ||

| Mediating (VaR) | −1.003 | 0.162 | −6.176 | 0.000 | ||

| Panel D | Random Forest | Direct | 0.730 | 0.105 | 6.976 | 0.000 |

| Mediating (ESG) | 2.831 | 0.171 | 16.580 | 0.000 | ||

| Mediating (VaR) | −2.919 | 0.476 | −6.135 | 0.000 |

5. Discussion

5.1. The Non-Linear Dynamics of Controversy and Resilience

5.2. The “Insurance” Mechanism of ESG and VaR

5.3. Heterogeneity and Contextual Factors

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Managerial and Policy Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Variable Definitions

| Type | Name | Meaning | Measurement Method | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Corporate Resilience Scores | is weighted by indicators such as “Stock price recovery rate”, “Quick ratio”, “Average return rate”, “R&D investment”, “Cash operation index”, “Total asset turnover rate”, and “Maximum withdrawal rate”. | Wind | |

| Independent variable | Ratings of controversial events | |||

| Mediating variable, Independent variable | ESG ratings | |||

| Mediating variable, Dependent variable | value-at-risk | |||

| Control variables | Firm total assets | |||

| Proportion of liabilities to assets | ||||

| Net profit margin of total assets | ||||

| Turnover rate of total assets | ||||

| Cash flow to current liabilities ratio | ||||

| Operating income growth rate | ||||

| Number of board members | ||||

| Proportion of independent directors | ||||

| Equity balance degree | ||||

| Tobin’s Q value | ||||

| Listed years | ||||

| Proportion of fixed assets | ||||

| Control variables, Categorical variables | Location of the company | |||

| Corporate governance structure | ||||

| Industry | Assigning natural numbers to industry code in order. | CSRC Industry Classification; | ||

| Share Price Recovery = (The date of the peak stock price within one year-the date of the trough stock price within one year). If the Share Price Recovery >0, it indicates that the stock price has recovered within one year. This is then recorded as EventState = 1; otherwise, it is recorded as EventState = 0. | Wind | |||

| Instrumental variable | There is a disparity among companies in how they score controversial events within the industry. | Wind |

Appendix B. Description of the Equation

Appendix C. Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlation

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.027 | 0.503 | |||||||||||

| 2.920 | 0.093 | 0.044 (0.000) | ||||||||||

| 6.086 | 0.768 | 0.053 (0.000) | 0.106 (0.000) | |||||||||

| 6.839 | 2.094 | −0.522 (0.000) | −0.008 (0.253) | −0.081 (0.000) | ||||||||

| 22.298 | 1.299 | 0.137 (0.000) | −0.203 (0.000) | 0.192 (0.000) | −0.287 (0.000) | |||||||

| 0.401 | 0.192 | −0.074 (0.000) | −0.222 (0.000) | −0.046 (0.000) | −0.066 (0.000) | 0.496 (0.000) | ||||||

| 0.040 | 0.060 | 0.191 (0.000) | 0.140 (0.000) | 0.099 (0.000) | −0.024 (0.001) | 0.011 (0.117) | −0.333 (0.000) | |||||

| 0.602 | 0.339 | 0.199 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.982) | −0.009 (0.215) | −0.002 (0.745) | 0.084 (0.000) | 0.186 (0.000) | 0.240 (0.000) | ||||

| 0.053 | 0.063 | 0.151 (0.000) | 0.041 (0.000) | 0.071 (0.000) | −0.063 (0.000) | 0.087 (0.000) | −0.133 (0.000) | 0.469 (0.000) | 0.194 (0.000) | |||

| 0.098 | 0.259 | 0.086 (0.000) | 0.027 (0.000) | 0.044 (0.000) | 0.081 (0.000) | 0.038 (0.000) | 0.063 (0.000) | 0.336 (0.000) | 0.217 (0.000) | 0.079 (0.000) | ||

| 2.091 | 0.198 | 0.048 (0.000) | −0.033 (0.000) | 0.060 (0.000) | −0.096 (0.000) | 0.284 (0.000) | 0.143 (0.000) | 0.012 (0.095) | 0.007 (0.313) | 0.038 (0.000) | 0.007 (0.318) | |

| 37.966 | 5.585 | −0.007 (0.310) | −0.039 (0.000) | 0.033 (0.000) | 0.017 (0.021) | −0.013 (0.073) | −0.008 (0.262) | −0.023 (0.002) | −0.013 (0.085) | −0.001 (0.890) | −0.004 (0.550) | |

| 0.814 | 0.628 | −0.067 (0.000) | −0.021 (0.004) | 0.024 (0.001) | 0.060 (0.000) | −0.102 (0.000) | −0.063 (0.000) | −0.006 (0.386) | −0.045 (0.000) | −0.028 (0.000) | 0.023 (0.002) | |

| 1.821 | 0.890 | −0.022 (0.003) | 0.000 (0.953) | 0.064 (0.000) | 0.182 (0.000) | −0.334 (0.000) | −0.247 (0.000) | 0.191 (0.000) | −0.023 (0.001) | 0.108 (0.000) | 0.125 (0.000) | |

| 2.078 | 0.870 | 0.118 (0.000) | −0.173 (0.000) | 0.002 (0.736) | −0.220 (0.000) | 0.487 (0.000) | 0.342 (0.000) | −0.206 (0.000) | 0.034 (0.000) | 0.013 (0.071) | −0.100 (0.000) | |

| 0.198 | 0.142 | 0.013 (0.066) | −0.017 (0.020) | 0.014 (0.059) | −0.099 (0.000) | 0.137 (0.000) | 0.111 (0.000) | −0.046 (0.000) | 0.043 (0.000) | 0.190 (0.000) | 0.014 (0.054) | |

| 0.286 | 0.452 | 0.109 (0.000) | −0.050 (0.000) | 0.029 (0.000) | −0.128 (0.000) | 0.367 (0.000) | 0.252 (0.000) | −0.091 (0.000) | −0.003 (0.729) | −0.029( 0.000) | −0.046 (0.000) | |

| 1.645 | 0.655 | 0.002 (0.773) | 0.021 (0.003) | 0.047 (0.000) | 0.023 (0.002) | −0.055 (0.000) | −0.055 (0.000) | 0.003 (0.661) | 0.043 (0.000) | 0.004 (0.615) | 0.000 (0.982) | |

| 3.084 | 4.009 | −0.035 (0.000) | −0.069 (0.000) | −0.026 (0.000) | 0.036 (0.000) | 0.099 (0.000) | 0.048 (0.000) | −0.088 (0.000) | −0.149 (0.000) | −0.057 (0.000) | −0.039 (0.000) | |

| 0.449 | 0.497 | 0.342 (0.000) | −0.037 (0.000) | −0.034 (0.000) | 0.112 (0.000) | −0.036 (0.000) | 0.034 (0.000) | 0.042 (0.000) | 0.044 (0.000) | 0.042 (0.000) | 0.140 (0.000) | |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | ||||

| −0.559 (0.000) | ||||||||||||

| 0.025 (0.001) | −0.025 (0.001) | |||||||||||

| −0.106 (0.000) | 0.047 (0.000) | 0.079 (0.000) | ||||||||||

| 0.194 (0.000) | −0.009 (0.238) | −0.145 (0.000) | −0.087 (0.000) | |||||||||

| 0.094 (0.000) | −0.010 (0.178) | −0.080 (0.000) | −0.122 (0.000) | 0.140 (0.000) | ||||||||

| 0.266 (0.000) | −0.043 (0.000) | −0.208 (0.000) | −0.165 (0.000) | 0.428 (0.000) | 0.127 (0.000) | |||||||

| −0.095 (0.000) | 0.037 (0.000) | 0.057 (0.000) | 0.015 (0.038) | −0.139 (0.000) | −0.113 (0.000) | −0.168 (0.000) | ||||||

| 0.037 (0.000) | 0.016 (0.028) | 0.006 (0.387) | 0.015 (0.043) | 0.056 (0.000) | −0.181 (0.000) | 0.140 (0.000) | 0.003 (0.713) | |||||

| 0.004 (0.626) | −0.011 (0.126) | −0.018 (0.012) | 0.153 (0.000) | 0.081 (0.000) | 0.012 (0.083) | 0.031 (0.000) | −0.018 (0.013) | −0.023 (0.001) |

Appendix D. The Effect of Each Variable

Appendix E. Other Algorithms’ Results

| Panel | Algorithm | Independent Variable | Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | Pr (>|t|) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A Direct effect | Lasso | 0.253 | 0.037 | 6.822 | 0.000 | |

| XGBoost | 0.213 | 0.035 | 6.073 | 0.000 | ||

| SVM | 0.273 | 0.035 | 7.737 | 0.000 |

| Effect | Algorithm | Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | Pr (>|t|) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediating effect of ESG ) | Lasso | 1.088 | 0.062 | 17.540 | 0.000 |

| XGBoost | 0.870 | 0.057 | 15.200 | 0.000 | |

| SVM | 0.842 | 0.059 | 14.280 | 0.000 | |

| Mediating effect of VaR ) | Lasso | −1.093 | 0.163 | −6.715 | 0.000 |

| XGBoost | −0.824 | 0.160 | −5.148 | 0.000 | |

| SVM | −1.036 | 0.160 | −6.469 | 0.000 |

| Classification | Effect | Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | Pr (>|t|) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lasso | 1.089 | 0.062 | 17.552 | 0.000 | |

| XGBoost | 0.893 | 0.058 | 15.337 | 0.000 | |

| SVM | 0.833 | 0.059 | 14.023 | 0.000 | |

| Lasso | −0.089 | 0.019 | −4.622 | 0.000 | |

| XGBoost | −0.862 | 0.020 | −4.158 | 0.000 | |

| SVM | −0.104 | 0.020 | −5.242 | 0.000 | |

| Lasso | −0.136 | 0.001 | −94.452 | 0.000 | |

| XGBoost | −0.119 | 0.001 | −84.082 | 0.000 | |

| SVM | −0.133 | 0.001 | −93.742 | 0.000 | |

| Total indirect effect | Lasso | 0.013 | - | - | - |

| XGBoost | 0.011 | - | - | - | |

| SVM | 0.012 | - | - | - |

References

- Weber, O. Environmental, Social and Governance Reporting in China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2014, 23, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorobantu, S.; Henisz, W.J.; Nartey, L. Not All Sparks Light a Fire: Stakeholder and Shareholder Reactions to Critical Events in Contested Markets. Adm. Sci. Q. 2017, 62, 561–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cretu, A.E.; Brodie, R.J. The Influence of Brand Image and Company Reputation Where Manufacturers Market to Small Firms: A Customer Value Perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DesJardine, M.; Bansal, P.; Yang, Y. Bouncing Back: Building Resilience through Social and Environmental Practices in the Context of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 1434–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, O.K.; Eshraghi, A.; Muradoglu, G. Staring Death in the Face: The Financial Impact of Corporate Exposure to Prior Disasters. Br. J. Manag. 2021, 32, 1284–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulon, B.; Marsat, S. Does Environmental Footprint Influence the Resilience of Firms Facing Environmental Penalties? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 6154–6168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsat, S.; Pijourlet, G.; Ullah, M. Does Environmental Performance Help Firms to Be More Resilient against Environmental Controversies? International Evidence. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 44, 102028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldawsari, S.H. Does ESG Uncertainty Disrupt Inventory Management? Evidence from an Emerging Market. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiad, A.; Bluedorn, J.; Guajardo, J.; Topalova, P. The Rising Resilience of Emerging Market and Developing Economies. World Dev. 2015, 72, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, S.; Shapiro, A. Value-at-Risk-Based Risk Management: Optimal Policies and Asset Prices. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2001, 14, 371–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodnar, G.M.; Hayt, G.S.; Marston, R.C. 1998 Wharton Survey of Financial Risk Management by US Non-Financial Firms. Financ. Manag. 1998, 27, 70–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, J.; Christoffersen, P.; Pelletier, D. Evaluating Value-at-Risk Models with Desk-Level Data. Manag. Sci. 2009, 57, 2213–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David Cabedo, J.; Moya, I. Estimating Oil Price ‘Value at Risk’ Using the Historical Simulation Approach. Energy Econ. 2003, 25, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Väätänen, J.; Khaneja, S. Value Added Reseller or Value at Risk: The Dark Side of Relationships with VARs. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 55, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groening, C.; Kanuri, V.K. Investor Reaction to Positive and Negative Corporate Social Events. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1852–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Generalized Additive Models: Some Applications. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1987, 82, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernozhukov, V.; Chetverikov, D.; Demirer, M.; Duflo, E.; Hansen, C.; Newey, W.; Robins, J. Double/Debiased Machine Learning for Treatment and Structural Parameters. Econom. J. 2018, 21, C1–C68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, R.; Ivkovíc, Z.; Trzcinka, C. Cross-Subsidization in Institutional Asset Management Firms. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2018, 31, 638–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, K.V.; Servaes, H.; Tamayo, A. Social Capital, Trust, and Firm Performance: The Value of Corporate Social Responsibility during the Financial Crisis. J. Finance 2017, 72, 1785–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.A.; Gruber, D.A.; Sutcliffe, K.M.; Shepherd, D.A.; Zhao, E.Y. Organizational Response to Adversity: Fusing Crisis Management and Resilience Research Streams. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 733–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoh, P.-L.; Roth, K. An Empirical Analysis of Sustained Advantage in the U.S. Pharmaceutical Industry: Impact of Firm Resources and Capabilities. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Yeung, A.C.L.; Han, Z.; Huo, B. The Effect of Customer and Supplier Concentrations on Firm Resilience during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Resource Dependence and Power Balancing. J. Oper. Manag. 2023, 69, 497–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, R.; Koskinen, Y.; Zhang, C. Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Risk: Theory and Empirical Evidence. Manag. Sci. 2018, 65, 4451–4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianconi, M.; Yoshino, J.A. Risk Factors and Value at Risk in Publicly Traded Companies of the Nonrenewable Energy Sector. Energy Econ. 2014, 45, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hautsch, N.; Schaumburg, J.; Schienle, M. Financial Network Systemic Risk Contributions*. Rev. Financ. 2015, 19, 685–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P.C. The Relationship Between Corporate Philanthropy And Shareholder Wealth: A Risk Management Perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 777–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Gao, H.; Liu, Z.; Treepongkaruna, S. Strategic Choices in Going Public: ESG Performance Implications in China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 7708–7728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Le, Q.; Peng, M.; Zeng, H.; Kong, L. Does Central Environmental Protection Inspection Improve Corporate Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance? Evidence from China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 2962–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Chen, X.; Wang, C. The Impact of Sustainable Development Planning in Resource-Based Cities on Corporate ESG–Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 2023, 127, 107087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Liu, L.; Luo, S. Sustainable Development, ESG Performance and Company Market Value: Mediating Effect of Financial Performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 3371–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenkopf, J.; Juranek, S.; Walz, U. Responsible Investment and Stock Market Shocks: Short-Term Insurance without Persistence. Br. J. Manag. 2023, 34, 1420–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. Do ESG ETFs Provide Downside Risk Protection during COVID-19? Evidence from Forecast Combination Models. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 94, 103320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model Type | AIC | BIC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Regression Model | 0.233 | 22,506.73 | 22,655.66 |

| GAM | 0.235 | 22,460.08 | 22,653.84 |

| Panel | Algorithm | Independent Variable | Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | Pr (>|t|) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A Direct effect | Random Forest | 0.240 | 0.036 | 6.698 | 0.000 | |

| Panel B Direct effect ) | Random Forest | −1.216 | 0.312 | −3.896 | 0.000 | |

| 0.233 | 0.047 | 4.916 | 0.000 | |||

| Panel C Direct effect , with interaction terms) | Random Forest | −2.793 | 0.744 | −3.754 | 0.000 | |

| 0.208 | 0.090 | 2.331 | 0.020 |

| Effect | Algorithm | Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | Pr (>|t|) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediating effect of ESG ) | Random Forest | 1.001 | 0.058 | 17.180 | 0.000 |

| Mediating effect of VaR ) | Random Forest | −0.984 | 0.163 | −6.044 | 0.000 |

| Panel | Classification | Effect | Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | Pr (>|t|) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Corporate ownership | Direct | 0.145 | 0.064 | 2.276 | 0.023 | |

| Mediating (ESG) | 1.025 | 0.099 | 10.335 | 0.000 | ||

| Mediating (VaR) | −1.046 | 0.280 | −3.739 | 0.000 | ||

| Direct | 0.264 | 0.044 | 6.035 | 0.000 | ||

| Mediating (ESG) | 0.956 | 0.071 | 13.382 | 0.000 | ||

| Mediating (VaR) | −0.983 | 0.201 | −4.891 | 0.000 | ||

| Panel B: Regions | Direct | 0.231 | 0.036 | 6.437 | 0.000 | |

| Mediating (ESG) | 1.019 | 0.059 | 17.230 | 0.000 | ||

| Mediating (VaR) | −0.969 | 0.163 | −5.954 | 0.000 | ||

| Direct | 0.246 | 0.036 | 6.860 | 0.000 | ||

| Mediating (ESG) | 1.000 | 0.059 | 17.046 | 0.000 | ||

| Mediating (VaR) | −0.970 | 0.163 | −5.949 | 0.000 | ||

| Direct | 0.237 | 0.036 | 6.603 | 0.000 | ||

| Mediating (ESG) | 1.006 | 0.059 | 17.062 | 0.000 | ||

| Mediating (VaR) | −0.964 | 0.163 | −5.913 | 0.000 |

| Variable | Type | Edf | Ref.df | F Value | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoothing term | 2.416 | 2.760 | 5.225 | 0.009 | |

| 2.309 | 2.644 | 7.091 | 0.000 |

| Classification | Effect | Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | Pr (>|t|) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 1.007 | 0.058 | 17.320 | 0.000 | |

| −0.114 | 0.021 | −5.539 | 0.000 | ||

| −0.134 | 0.001 | −96.256 | 0.000 | ||

| Total indirect effect | 0.015 | - | - | - | |

| One-period Lag Effect | |||||

| Random Forest | 0.262 | 0.066 | 3.989 | 0.000 | |

| −0.066 | 0.023 | −2.903 | 0.004 | ||

| −0.018 | 0.002 | −9.632 | 0.000 | ||

| Total indirect effect | 0.0004 | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Wang, D.D. The Impact of Controversial Events on Corporate Resilience: The Chain-Mediating Role of ESG and Value-at-Risk. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11032. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411032

Zhang J, Wang DD. The Impact of Controversial Events on Corporate Resilience: The Chain-Mediating Role of ESG and Value-at-Risk. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11032. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411032

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jie, and Derek D. Wang. 2025. "The Impact of Controversial Events on Corporate Resilience: The Chain-Mediating Role of ESG and Value-at-Risk" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11032. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411032

APA StyleZhang, J., & Wang, D. D. (2025). The Impact of Controversial Events on Corporate Resilience: The Chain-Mediating Role of ESG and Value-at-Risk. Sustainability, 17(24), 11032. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411032

_Li.png)