Abstract

Evaluating and categorizing an economy’s capacity for regional innovation is important. Within China, regional innovation capacity is imbalanced. With this in mind, we construct a data system to assess regions within the Yangtze River Basin. Using this data system, we deploy a series of four models to analyze change in the distribution of the Basin’s scientific and technological innovation capacity and obstacles to enhancing that capacity. The variables we select and our research approach are the prime features of the research reported here. Our research findings are that an area’s count of high-tech enterprises, their shares of export revenues, and their relative level of activity in technology markets most influence a region’s capacity for science and technology innovation. Our index expects continued growth in the Basin’s innovative capacity through 2033, particularly in Shanghai and Jiangsu. To improve innovative equity, we recommend that the government try better at balancing investment at the regional level, enhance access to the interior, and nudge enterprises to improve their engagement in global trade.

1. Introduction

Scientific and technological innovation is not only the primary driver of sustainable economic growth but also pivotal for achieving a harmonious balance between society and the natural environment. For example, innovation accelerates advances in environmental technologies and renewable energy [1,2] and plays a vital role in mitigating the effects of climate change, reducing environmental damage, and ensuring food and energy security [3]. The Yangtze River Basin contributes one-third of China’s freshwater runoff and sustains the livelihoods of 459 million people. Geographical heterogeneity across its upper, middle, and lower reaches has caused an imbalance in the distribution of resources for innovation. For instance, Guo et al. [4] found that the overall level of innovation in the eastern coastal areas of China and its six central provinces is high but is low in the country’s western regions, with an increasing overall spatial correlation. Hence, the establishment of a comprehensive evaluation framework is imperative for a thorough examination of the factors and characteristics of innovation capacity imbalances across the Yangtze River Basin.

Systems of regional innovation represent complex configurations of interconnected social, economic, technological, and ecological subsystems, each of which comprises capital, talent, technology, and resources [5]. The evaluation of the capabilities of innovation encompasses indicator systems and methodologies of assessment. Research on indicators examines critical factors, such as the inputs and outputs of innovation and the relevant environmental conditions [6,7,8,9]. No standardized framework for evaluating them has thus far been established. Dziallas and Blind [10] identified 82 distinct indicators that influence the processes and outcomes of innovation, spanning the culture of innovation, capacity for absorbing knowledge, organizational structures, investment in R&D, financial performance, market conditions, and environmental factors. Recent studies have used varied approaches to assess the capacity for regional innovation. For instance, Szopik-Depczyńska et al. [11] developed a multi-criteria framework of classification for the EU to comparatively analyze the patterns of innovation while providing a comprehensive regional assessment. Aronica et al. [12] examined regions of Italy through the lens of the input-output relationships of innovation and the capacity for knowledge absorption. Brodny and Tutak [13] established a system to assess the capacity of innovation in Poland based on 15 indicators across three dimensions: the capability for innovation, its status, and economic development. Liu et al. [14] developed a three-tier evaluation system comprising 50 indicators to assess innovation inputs, outputs, and benefits in five provinces of Northwest China. A scientific and rational system of indicators is the foundational prerequisite for effectively assessing the capabilities for innovation. The construction of such a system must be closely aligned with regional developmental realities, grounded in a comprehensive and systemic perspective, and based on a deep understanding of the functional dynamics of all actors within the landscape of innovation.

Current research on the assessment of regional innovation synergistically draws on several analytical approaches to compensate for the limitations of single-method evaluations and to generate comprehensive insights into innovation ecosystems. Examples of such integrated approaches include methods of weighting and prioritization [e.g., the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) and entropy-weighting method], comprehensive techniques of evaluation (e.g., fuzzy comprehensive evaluation), and tools to assess efficiency and conduct spatial analyses (e.g., Dagum decomposition of the Gini coefficient) [15,16,17]. Yang et al. [18] applied the gray clustering method to comprehensively evaluate the capabilities of innovation of 31 provinces and municipalities in China, focusing on inputs to innovation, its outputs, carriers of innovation, and its environment. Shan [19] used the AHP to assess Hangzhou’s capacity for innovation along four dimensions (input capacity, environment of innovation, capacity for management, and output of innovation) and explored specific strategies for enhancing the capabilities of innovation. By using the Dagum decomposition of the Gini coefficient, Li et al. [20] evaluated the heterogeneity of innovation among 11 coastal provinces and municipalities in China and concluded that the eastern coastal regions enjoy significant advantages. These findings show the robust assessment of regional capabilities of innovation necessitates multi-dimensional frameworks of evaluation that can capture both structural and temporal dimensions, a rigorous analysis of spatial heterogeneity to account for geographical disparities, and a systematic investigation of the multi-factor synergistic mechanisms underlying innovation.

Most relevant studies have focused on the national level and individual provinces, predominantly developed coastal provinces, cities, or the Yangtze River Economic Belt [21,22]. In contrast, few studies have considered typical regions within the entire Yangtze River Basin, and even fewer have focused on the central and western regions. Furthermore, some studies have considered relatively short time spans or a limited number of reference objects, such that this has hindered an in-depth analysis and comparison of the results and has yielded biased conclusions. The numerous systems of indices to assess the capabilities of scientific and technological innovation also lack a unified standard, which has impeded the comparability and universality of the research findings. To gain more fine-grained insights into the complex dynamics of innovation of the basin and improve policies for optimizing resource allocation and cross-provincial collaboration, research in the area should be expanded to cover underrepresented upper/middle reaches of the basin. Moreover, a longitudinal analysis of the evolution of the regional system of innovation should be conducted.

This study aims to: (1) construct a scientific and reasonable system of indices to assess the capability for regional innovation of the Yangtze River Basin; (2) analyze the characteristics of spatiotemporal evolution of scientific and technological innovation in different regions, and their driving factors; and (3) identify key obstacle factors hindering improvements in the capability for regional innovation and propose targeted policy suggestions. Our research reveals the patterns of spatial differentiation of and mechanisms driving the development of regional innovation at the scale of watersheds. The aims are to enrich the application of regional innovation system theory within unique economic–geographical units, and to provide policy-related insights for the high-quality development of the Yangtze River Basin.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Area

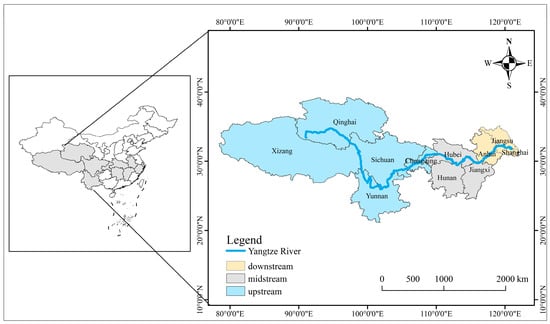

We focused on the 11 provincial-level regions within the Yangtze River Basin (Figure 1). The basin spans 1.8085 million km2, accounting for about a fifth of China’s total area of land. It has a prominent multi-level stepped terrain, and the river flows through mountains, plateaus, basins, hills, and plains from west to east. Based on its natural geographical and socio-economic characteristics, we divided the Yangtze River Basin into three regions: the upper, middle, and lower reaches. The upper reaches included the Tibet Autonomous Region, Qinghai Province, Sichuan Province, Yunnan Province, and Chongqing Municipality; the middle reaches included Hubei Province, Hunan Province, and Jiangxi Province; while the lower reaches covered Anhui Province, Jiangsu Province, and Shanghai Municipality. This regional division not only accurately reflected the natural hydrological characteristics of the Yangtze River as it flowed from west to east, but also clearly embodied the spatial pattern of its socioeconomic development. This provided a geographical foundation for the subsequent analysis of the capabilities of scientific and technological innovation in different regions.

Figure 1.

The mainstream of Yangtze River Basin.

2.2. Indicators to Assess Capability for Regional Innovation

The variables were selected through a three-stage process to ensure that they were theoretically grounded, scientifically relevant, and practically operable. First, an initial pool of indicators was identified based on a comprehensive review of the literature on the evaluation of regional innovation [23,24,25,26]. Second, this longlist was refined by retaining only the variables that were the most relevant to our specific research context, all the while ensuring that each indicator accurately represented a core component of the innovation process. Finally, the critical step of assessing the availability of the data was applied. We prioritized variables with consistent and officially published data across all studied regions to guarantee the objectivity and reproducibility of the analysis. This approach ensured that our indicator system was both scientifically grounded and practically operable. The final framework comprised three layers of indicators, the inputs to scientific and technological innovation, its outputs, and the environment, encompassing 21 secondary indicators. The definitions of the indicators are provided in the Appendix A, Table A1.

- (1)

- Input to scientific and technological innovation

The input to innovation refers to the investment in resources dedicated to such activities. These resources primarily included the government’s internal expenditure on R&D and related items. The number of personnel involved in scientific and technological activities (X1) reflected the scale of the input in innovation in terms of human resources. The full-time equivalent of R&D personnel per 10,000 people (X2) represented the density of human resources used for R&D. The number of institutions of higher education (X3) represented the foundation for scientific research and educational institutions. The number of high-tech enterprises (X4) referred to the scale of innovative entities in the area. The government’s financial investment in science and technology as a ratio of the GDP (X5), internal expenditure on R&D as a ratio of the GDP (X6), and expenditure on financial education as a ratio of the GDP (X7) were used to measure the intensity of distribution of funds for innovation with respect to the total economic output.

- (2)

- Output of scientific and technological innovation

The output of innovation encompassed various achievements derived from such activities, including both direct and indirect outputs. This reflected regional scientific and technological strength and drove technological transformation. We selected indicators across three dimensions: patents, research papers, and income. The revenue from high-tech industries from product sales (X8) and their total industrial output (X9) jointly reflected the scale of economic output of high-tech industries. The output of high-tech enterprises, particularly their share in the total industrial output, is a key indicator of a given region’s industrial upgrade and its tangible economic outcomes of innovation. This is because it directly reflects the scale and success of translating technological achievements into market supply. The volume of transactions in the technology market (X10) reflected the vitality of such transactions and the value of transformation in terms of achievement. The number of patents per 10,000 people (X11) represented the capability for the creation of intellectual property, while the export income of enterprises (X12) reflected their competitiveness in terms of innovative achievements in the international market. The export revenue of enterprises quantifies their market success in terms of innovation by demonstrating their ability to create unique value that secures a global competitive edge for them. The proportion of revenue from new product sales as part of the business income of industrial enterprises above a designated size (X13) measured the contribution of new products to their revenue, thereby reflecting the market penetration of innovative products. The term “industrial enterprises above a designated size” refers to industrial enterprises with an annual business revenue of RMB 20 million (approximately US $2.8 million) or higher. The number of published scientific and technological papers (X14) represented the output of innovative achievements at the level of academic research.

- (3)

- Environment for scientific and technological innovation

The environment of scientific and technological innovation referred to the sum of internal and external factors that influenced the activities of the subjects of innovation. We selected indicators that were closely associated with R&D activities. The year-end loan balance of financial institutions (X15) reflected the capacity of the financial system to provide funding for innovation. The year-end number of mobile phone users (X16), as well as the number of fixed-line phone and Internet users (X20), was the degree of popularization of information and communication that underpinned informational interaction for innovation. The mileage of graded highways (X17) and per capita urban area of road (X21) reflected the accessibility of transportation. Graded highways refer to all highways that are technically classified as such according to official Chinese standards (Technical Standard for Highway Engineering [WTBZ] JTJ01-88) [27] and encompass a hierarchy from expressways to roads with a lower classification. The number of college students per 10,000 people (X18) reflected the educational foundation for the reserve of talent. The number of books in public libraries per 100 people (X19) evaluated the accessibility of knowledge. Together, these indicators provided the hardware, resources, and environment of talent required for innovation (Table 1).

Table 1.

System of indicators to assess the capabilities of scientific and technological innovation.

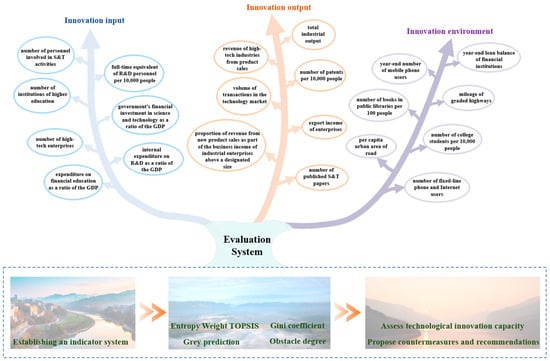

We developed a comprehensive research framework to evaluate the capabilities of Scientific and technological innovation in the Yangtze River Basin through six key steps: (1) constructing a multi-dimensional system of indicators that incorporated the input, output, and environmental factors; (2) standardizing raw data for cross-indicator comparability; (3) applying the entropy-weighted method for the objective determination of weights, combined with TOPSIS for optimizing the scheme; (4) analyzing regional disparities by using the Dagum decomposition of the Gini coefficient; (5) forecasting trends of development through gray prediction modeling; and (6) identifying key constraints via obstacle degree analysis. This integrated quantitative approach enabled both cross-sectional assessments and longitudinal predictions to support the evidence-based formulation of policies to support innovation, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Analysis of capabilities of scientific and technological innovation in the Yangtze River Basin.

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Entropy-Weighted TOPSIS

The entropy-weighted TOPSIS method was an improved version of the traditional TOPSIS approach through its combination it with the entropy method. This integrated methodology merged the advantages of objective weighting of entropy weighting with the multi-criteria decision-making capabilities of TOPSIS, thus mitigating the impact of extreme values on the sample size while enhancing the objectivity of weight assignment. Furthermore, the incorporation of the rank-sum ratio method addressed TOPSIS’s inherent limitation in categorical ranking, and made it particularly suitable for evaluating the comprehensive indicators derived from diverse objective datasets [28].

- (1)

- Data standardization

After standardization, the data were subjected to logarithmic non-negative processing, where i = 1, 2, …, m (m represents the number of years, specifically m = 16) and j = 1, 2, …, n (n denotes the number of evaluation indicators, specifically n = 21).

- (2)

- Calculation of proportion Pij

- (3)

- Measurement of entropy value ej

- (4)

- Calculation of variation coefficient dj

- (5)

- Calculation of entropy weight wj

The weight assigned to a principle layer represents the sum of the weights of all corresponding indicators beneath it.

- (6)

- Calculation of Euclidean distances to the optimal and worst weighted indicators

- (7)

- Determination of index of capability for innovation in science and technology

To facilitate comparative analysis, we classified regional capabilities of innovation into five distinct levels: extremely low (0–0.20), relatively low (0.20–0.40), moderate (0.40–0.60), relatively high (0.60–0.80), and extremely high (0.80–1). This standardized system of classification enabled the clear identification of leaders in innovation (≥0.80) and regions that required targeted policy support (<0.20) [23].

2.3.2. Dagum Gini Coefficient

The Dagum Gini coefficient is a pivotal analytical tool for assessing disparities in regional development, and can decompose the overall inequality in this regard into three distinct components: intra-regional differences, inter-regional differences, and density of transvariation (cross-term components) [29,30]. This decomposition yielded three measurable contributions: Gw (contribution of intra-regional disparity), Gnb (net contribution of inter-regional disparity), and Gt (contribution of the density of transvariation). The analytical results systematically revealed the evolutionary trends of spatial disparities in scientific and technological innovation across the Yangtze River Basin, and clearly showed the differentiated performance and relative influence of the upper, middle, and lower reach regions. These quantitative findings provided robust support for formulating differentiated, yet coordinated, strategies for development. The specific formulae followed the methodology established by Wei et al. [31]:

where Djh represents the relative influence of the index of scientific and technological innovation between regions. It is defined as:

where k represents the number of divided regions, k = 3, and pj is the proportion of the number of provinces in region j to the total number of provinces. , where j = 1, 2, …, k, while Gjj and Gjh represent the intra- and inter-regional Gini coefficients, respectively. djl characterizes differences in the composite index between regions j and l, and yjl represents the first-order moment of transvariation. The Gini coefficient ranged from zero to one, and the closer it was to one, the greater was the difference between the corresponding regions.

2.3.3. Gray Prediction Model GM (1,1)

We applied the GM (1,1) predictive model, which is rooted in gray system theory, to quantitatively forecast the trends of development of scientific and technological innovation across the provinces in the Yangtze River Basin from 2024 to 2033. The model used an accumulated generating operator (AGO) to preprocess the original discrete data and reduce random disturbances in them. This allowed for the establishment of reliable predictive models, even in case of few samples and incomplete information [22,32].

where α (development coefficient) determines the system’s inherent trend of growth, μ (gray input quantity) captures the effect of external influences on the system dynamics, e represents the natural logarithm base, t denotes time, and denotes simulated values of the original sequence of data. To ensure the predictive reliability of the model, we implemented a rigorous validation protocol by using two statistical measures: the probability of small error (p) and the posterior variance ratio (C) [33]. The accuracy of the model was classified into one of four grades based on these metrics. When p ≥ 0.95 and C ≤ 0.35, the model was considered to have good precision; when 0.80 ≤ p < 0.95 and 0.35 < C ≤ 0.50, its precision was considered to have qualified; the ranges 0.70 ≤ p < 0.80 and 0.50 < C ≤ 0.65 represent bare qualification, while p < 0.70 and C > 0.65 mean that the model was unqualified [34].

2.3.4. Obstacle Degree Model

The obstacle degree model is a diagnostic tool used to identify and quantify the key factors constraining the capacity for regional innovation [35]:

where Fj denotes the degree of contribution of the relevant factor, Wj is the weight of the j-th indicator, Rj is the weight of the criterion layer to which the j-th indicator belongs, Ij denotes the degree of deviation of an indicator, Xj is the standardized value of a given indicator, and Yj represents the degree of hindrance posed by the obstacle to the j-th indicator.

2.4. Data Sources and Processing

The data used in this study were derived from the China Statistical Yearbook, China Torch Statistical Yearbook, China Science and Technology Statistical Yearbook (2008–2023), and the China Economic and Social Big Data Research Platform. Linear interpolation was used to fill in the missing values [36].

The weights of the indicators and the degree of difficulty of the obstacles were calculated in Microsoft Excel 2019, while gray prediction, the Gini coefficient, correlation analysis, and principal component analysis were determined by using IBM SPSS Statistics 27. Charts were generated by using ARCGIS 10.8.1 and Origin 2022.

3. Results and Discussion

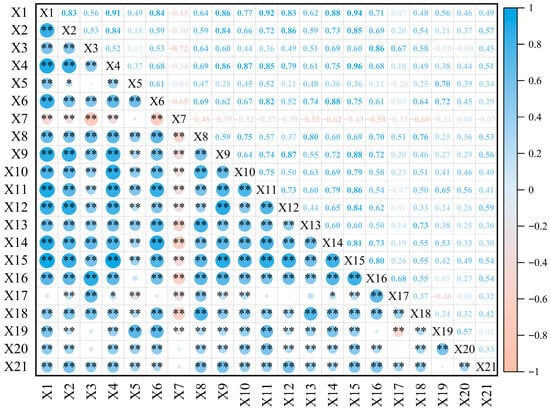

3.1. Weights of Indicators of Capacity for Innovation

As shown in Figure 3, Pearson’s correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationships among the 21 indicators. The results revealed moderate to strong correlations between several variables. For instance, the coefficient of correlation between the number of personnel involved in scientific and technological activities (X1) and the full-time equivalent of R&D personnel per 10,000 people (X2) was 0.83. Similarly, strong correlations were observed between the number of institutions of higher education (X3) and the year-end number of mobile phone users (X16) (r = 0.86), as well as between the number of high-tech enterprises (X4) and the total industrial output (X9) (r = 0.86). Although these indicators represent distinct dimensions of the effects of regional development in sci-tech innovation on the input, output, and environmental context, their significant correlations demonstrate intrinsic interconnections within the innovation system.

Figure 3.

The Pearson correlation among 21 scientific and technological innovation indicators (* significance level of p < 0.05; ** Significance level of p < 0.01).

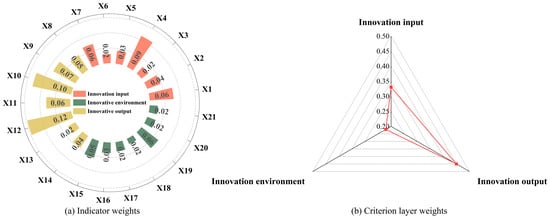

Figure 4a shows that the weights of the export revenue of enterprises (X12), volume of transactions in the technology market (X10), and number of high-tech enterprises (X4) were 0.11, 0.10, and 0.083, respectively, and they were the top three indicators by rank. This suggested that they were the key drivers of the capability for scientific and technological innovation. Moreover, the industrial output of high-tech enterprises (X9), number of patents granted per 10,000 people (X11), and number of R&D personnel (X1) had weights of 0.064, 0.063, and 0.062, respectively. This confirmed their role as secondary, yet significant, factors. These findings were closely aligned with those reported by Lei et al. [37], and highlighted the importance of the volume of transactions in the technology market for evaluating the capacity of national high-tech zones in Guangdong Province for innovation. Nguyen et al. [38] have emphasized the importance of human capital (e.g., R&D personnel) in driving scientific and technological progress in low- and middle-income countries. The stock of human capital also significantly enhances innovation-related performance, and has a strong positive impact on the output of innovation [39]. Moreover, Liu et al. [40] found that the certification of high-tech enterprises can promote corporate innovation in China, especially that represented by invention patents.

Figure 4.

Distribution of weights across the indicator and criterion layers for scientific and technological innovation (Red dots in subfigure b mean the criterion layers weights).

The dimensional weights given in Figure 4b showed that the output of innovation (0.45) made the largest contribution, which underscored its central role in measuring the capability for innovation. In contrast, the input to innovation (0.33) and the environment for it (0.22) had smaller weights, but still provided essential support to the system of innovation.

3.2. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of the Capacity for Innovation

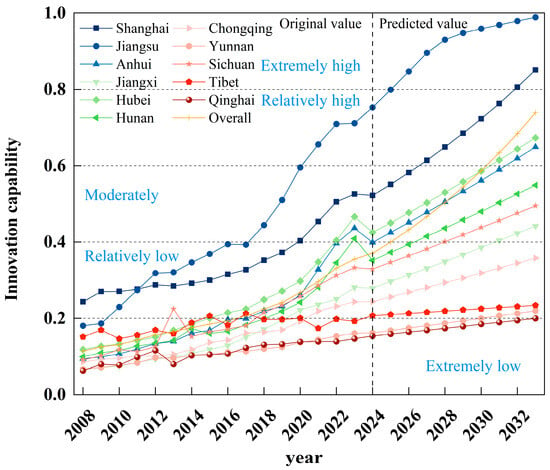

From 2008 to 2023, the capacity for innovation in science and technology in the 11 provinces of the Yangtze River Basin demonstrated consistent upward growth (Figure 5). Jiangsu Province emerged as the standout performer, with its index surging from 0.18 to 0.71 over this period, and this solidified its position as the regional leader in innovation. Shanghai likewise exhibited robust progress, and its index increased by more than twice (from 0.243 to 0.526). This reflected the mature innovation ecosystem and advanced technological capabilities of the downstream region.

Figure 5.

Predicted and evaluated levels of scientific and technological innovation capacity.

The index of the capacity for innovation in science and technology in the provinces of Jiangxi, Hubei, and Hunan, which are situated in the central reaches of the Yangtze River Basin, ranged from 0.066 to 0.47. While their rate of growth was slightly lower than that of the eastern region, their overall trajectory was positive. These regions have gradually evolved from an extremely low level of innovation to low and moderate levels, reflecting the steady enhancement in the strength of central China in science and technology.

The index of the capacity for innovation in science and technology in the upper reaches of the Yangtze River, including in Chongqing, Yunnan, and Sichuan, was between 0.067 and 0.33, and had a slow momentum of growth. Despite a slow increase from an extremely low level to a low level, they still lagged behind the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River. From 2008 to 2023, Tibet and Qinghai recorded relatively slow growth. Even in 2023, their index of scientific and technological innovation remained below 0.20, indicating that the level of innovation in the field in these regions continued to be extremely low. Notably, Sichuan and Chongqing, in the upper reaches of the Yangtze River, recorded relatively high scores. This phenomenon can be attributed to the launch of such initiatives as the “Belt and Road” Sci-tech Innovation Cooperation Zone, Sichuan-Chongqing Joint Key Laboratories, and the Western Science City. These regions continue to capitalize on the overarching advantages of synergistic collaboration, and are cultivating new strengths in innovation-driven development. It is evident that as we traverse westward from the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, the collaboration for innovation that is centered on the Chengdu-Chongqing region is becoming increasingly close, and is driving the deep integration of industry, academia, and research in the upper reaches of the Yangtze River.

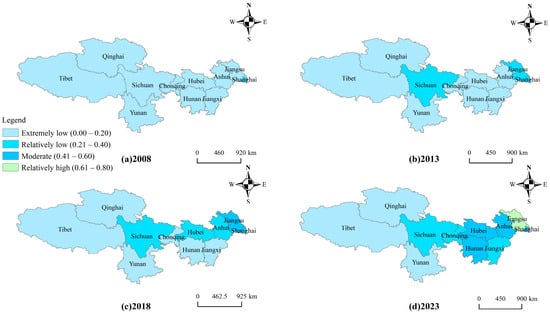

We chose data from 2008, 2013, 2018, and 2023 to spatially visualize the fluctuations in the regional innovation index (Figure 6) to reveal its spatial distribution. From 2008 to 2023, the lower region of the Yangtze River Basin consistently maintained a leading position in technological innovation. Jiangsu Province and Shanghai gradually advanced to medium and high levels of innovation, respectively, while the middle region of the basin progressed from very low to relatively low levels and demonstrated clear spatial clustering. This trend reflected both the transformation of the momentum for endogenous development in central China and the strategic success of the country’s innovation-driven approach to promoting balanced regional development. The ranking of regions by the average index for technological innovation in the Yangtze River Basin in 2008 was downstream (0.173) > midstream (0.095) > upstream (0.092). These regional disparities gradually narrowed, and the ranking in 2023 was downstream (0.558) > midstream (0.386) > upstream (0.215). Notably, the midstream region exhibited the most significant growth in this period, increasing by 4.1 times (using 2008 as the base year). The spatial imbalance in technological innovation across the Yangtze River Basin was pronounced at the provincial level. Overall, the basin exhibited a gradient of “high in the east and low in the west” in terms of technological innovation, with distinct regional clustering. Song et al. [41] and Wen et al. [42] have claimed that the effects of spatial spillover facilitate the diffusion of knowledge and technology from core urban clusters to neighboring cities, thus reinforcing the effects of agglomeration.

Figure 6.

Spatial distribution of the scientific and technological innovation capacity.

3.3. Predicted Capacity for Innovation

We applied the gray GM (1,1) predictive model to data from the provincial Innovation Index from 2008 to 2023 to forecast its trends of evolution in the Yangtze River Basin from 2024 to 2033. We observed a regional disparity in the predictive accuracy of the model (Table 2). It demonstrated a high predictive accuracy (p ≥ 0.95 and C ≤ 0.35) for eight provinces, which underscores its capability to reliably forecast trends of the capacity for innovation throughout most of the Yangtze River Basin. On the contrary, the model’s accuracy for Sichuan, Tibet, and Qinghai was only at a qualifying or barely qualifying level, implying that their predictions remained applicable.

Table 2.

Verification of the accuracy of the gray model of prediction.

Figure 5 shows that provinces in the Yangtze River Basin will generally maintain their upward trajectory in the innovation capacity in 2024–2033, and this reflects the basin-wide enhancement of technological capabilities. While the indices of all provinces are projected to grow, significant disparities exist in both the magnitude and pace of this growth that will accentuating regional imbalances. The downstream regions, represented by Shanghai and Jiangsu, will exhibit an accelerated capacity for innovation that is projected to reach high and very high levels during the forecasted period (Figure 5). Shanghai and Jiangsu’s substantial upgrade in innovation will generate positive spillover effects on neighboring provinces through technology transfer, industrial collaboration, and the sharing of resources for innovation.

Hubei and Anhui Provinces are rapidly emerging as innovation powerhouses in the Yangtze River Basin, and have exhibited strong potential to join Shanghai and Jiangsu as regions of relatively high levels of innovation (Figure 5). These provinces benefit from distinctive advantages owing to a dense concentration of prestigious higher education institutions and a robust pool of talent for scientific innovation [43]. Regional education significantly boosts the upgrade in export products of the high-tech industry, the agglomeration of which has a positive impact on this upgrade through the mediating roles of innovation and openness [44]. Meanwhile, robust government-driven developmental strategies for innovation have significantly enhanced the service efficiency of innovation and the capacity for governance.

Hunan, Sichuan, and Chongqing were projected to steadily advance to moderate levels of the capacity for innovation (Figure 5). In 2023, China’s Ministry of Science and Technology issued the “Guidelines on Accelerating the Development of Western Science Cities,” which designated science parks and innovation zones in Chengdu and Chongqing as pilot areas to promote clustered development. This fosters regional complementarity and collaboration to provide policy support for scientific innovation in the Chengdu-Chongqing economic zone.

In contrast, regions like Yunnan, Tibet, and Qinghai will continue to exhibit a relatively low level of innovation, and will trail behind more developed areas (Figure 5), owing to persistent shortages of the resources for innovation, including R&D funding, talent reserves, and technological stockpiles. While our projections indicated a sustained rise in the indices of innovation across the Yangtze River Basin, regional disparities may further widen in the years ahead.

3.4. Spatiotemporal Discrepancy in Capacity for Innovation

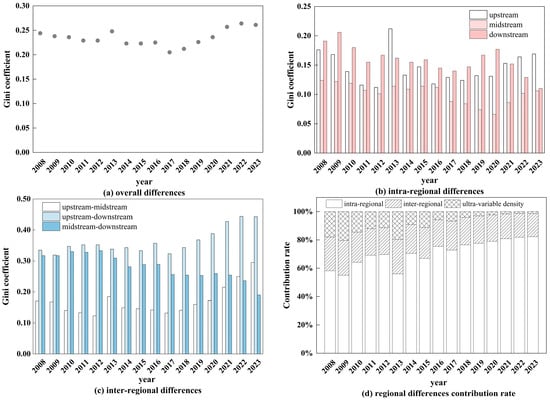

To thoroughly examine the spatial heterogeneity of the levels of technological innovation in the Yangtze River Basin, we used the Dagum Gini coefficient and the method for its decomposition to measure and analyze the overall disparities in provincial capabilities of innovation across the basin, and differences among the upper, middle, and lower reaches during 2008–2023.

Figure 7 shows the spatiotemporal patterns of inter-provincial disparities and intra-regional differentiation. The basin-wide analysis showed a trend of “decline followed by a rise” in regional disparities in innovation, with the overall coefficient of differentiation increasing from 0.24 in 2008 to 0.26 in 2023 (6.97% growth) (Figure 7a). With regard to intra-regional spatial discrepancies, the downstream region maintained the highest inequality (0.16 annual average, 42.40% decrease), followed by the upstream (0.15, 3.98% decrease) and midstream areas (0.10, 14.52% decrease) (Figure 7b). The concentrated resources for innovation and diversified industrial structures of economic powerhouses in the downstream region, like Shanghai and Jiangsu, have created significant developmental gaps with the neighboring Anhui Province that have become a key driver of intra-regional imbalance. Yang et al. [45] have revealed that Anhui’s 16 prefecture-level cities exhibited a moderate but an uneven efficiency of innovation among industrial enterprises. In contrast, the midstream region demonstrated relatively minor internal disparities that were attributable to the comparably rich natural resource endowments and convergent industrial structures of its three provinces. In recent years, the expansion of disparities in innovation in the upper Yangtze region has surpassed those in the downstream area (Figure 7b). This growing gap principally stems from the widening technological divide between the Sichuan-Chongqing hub and neighboring provinces (Yunnan, Qinghai, and Tibet). The central government’s 2020 strategic designation of the Chengdu-Chongqing Economic Circle as a “nationally influential sci-tech innovation hub” has further amplified this trend. Benefiting from advanced transportation networks and mature logistics systems, the twin-city cluster has exhibited consistent growth in its composite innovation index in 2015–2022 [46].

Figure 7.

Intra- and inter-regional differences in scientific and technological innovation capacity.

Inter-regional disparities were most prominent between the upstream and downstream (mean Gini = 0.363), and midstream and downstream regions (mean Gini = 0.281), and were smaller between the upstream and midstream areas (mean Gini = 0.170) (Figure 7c). The gap between the midstream and downstream areas has gradually narrowed, while that between the upstream and midstream regions has widened. The upstream area lagged in the inputs and outputs to innovation as well as environmental support (notably, Tibet and Qinghai), while the downstream area led in all dimensions. Notably, the innovation-related achievements of the downstream area have generated positive spillovers to the midstream region that have accelerated its convergence while expanding its lead over the upstream area.

The decomposition-based contributions of regional disparities to innovation were as follows: inter-regional differences (55.02–82.27%) > intra-regional differences (16.28–24.65%) > transvariational density (1.31–20.33%) (Figure 7d). While intra-regional and transvariational contributions exhibited a fluctuating temporal decline, which are a secondary factor influencing the overall regional disparities level. The density of super-variables contributed the least to the overall disparity, implying that the cross-regional overlap of the samples had a minimal impact. Meanwhile, inter-regional disparities showed a significant upward trend that solidified their dominance in shaping the overall inequality (Figure 7d). This pattern stemmed from upstream developed regions like Shanghai and Jiangsu attracted disproportionate shares of capital, talent, and technology to create self-reinforcing cycles of innovation, while underdeveloped downstream areas (e.g., Yunnan and Qinghai) faced widening gaps owing to insufficient investment and lagging outputs. For example, the downstream provinces had 46.6 patents per 10,000 people (vs. 9.9 for the upstream region), ¥11.78 trillion in high-tech industrial output (vs. ¥3.24 trillion), and ¥11,570.9 billion in technological market transactions (vs. 3.91 billion).

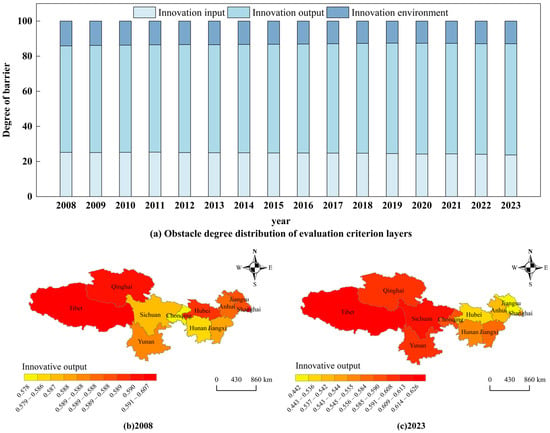

3.5. Obstacles to Capacity for Innovation

Based on measurements of the obstacle degree model (Figure 8a), the ratio of the degree of hindrance posed by each obstacle in each criterion layer of innovation in the Yangtze River Basin had the following characteristics. The average degrees of hindrance posed by obstacles of the criterion layers were ranked as the output of innovation (0.591) > input to innovation (0.296) > environment of innovation (0.113). This clearly showed that the output of innovation had the most prominent impact on the innovation index. The degree of hindrance posed by obstacles to the output of innovation showed a slow upward trend from 2008 to 2023, reflecting the suboptimal overall efficiency of the output of innovation among provinces and cities within the basin. Wang et al. [17] have also confirmed that the overall efficiency of innovation in the basin remains low, with a significant imbalance between R&D capabilities and the capacity for transforming S&T achievements. The former was notably stronger than the latter. Such a low output of innovation not only constrained improvements in the application and development of innovation, but also hindered the use of its innovation-driven role in ecological industries. We considered 2008 and 2023 as an example. The spatial distribution of the degree of hindrance posed by obstacles to the output of innovation is shown in Figure 8b,c. The output of innovation was consistently the core obstacle restricting improvements in the capabilities of innovation in the upper reaches of the Yangtze River Basin, and a low turnover of the technology market and insufficient revenue from enterprise exports were constraints. Data for 2023 showed that Shanghai’s sales of high-tech industrial products reached 1.0385 trillion yuan, far exceeding the average of 746.5 billion yuan reported for the upper reaches. Shanghai also recorded 1.9019 trillion yuan in the industrial output of high-tech enterprises and 464.23 billion yuan in the turnover of the technology market, compared with averages of 649.6 billion yuan and 59.14 billion yuan, respectively, for the upper reaches. Jiangsu maintained a significant lead over the best-performing areas in the upper reaches: 52.4 vs. 17 authorized patents per 10,000 people (Chongqing), and 172,238 vs. 96,124 scientific papers published (Sichuan). Jiangsu’s revenue from enterprise exports was 1.148 trillion yuan, with sales of new products by large-scale industrial enterprises accounting for 29% of main business revenue. This was in stark contrast with Tibet (lowest in the upper reaches), at 19 million yuan in exports and 2.1% for new products. To address this disconnect in the transformation of R&D, we recommend the establishment of a mechanism of transmission of downstream technology to the upper reaches, and the construction of an innovation consortium for the ecological industry that links downstream R&D with upstream manufacturing.

Figure 8.

Obstacle degree distribution of evaluation criterion layers for scientific and technological innovation and the innovation output layer spatial distribution.

We analyzed the top five obstacles to the indices of regional innovation from 2008 to 2023 (Table 3). The primary constraints on the capabilities of scientific and technological innovation by provinces and municipalities within the Yangtze River Basin shared common features along the order of the revenue of enterprise exports (X12), turnover of the technology market (X10), number of high-tech enterprises (X4), value of industrial output by high-tech enterprises (X9), and number of authorized patent applications per 10,000 people (X11).

Table 3.

Ranking of barriers to indicators of the capacity for innovation.

Innovation by enterprises is the foundation underpinning the high-quality development of China’s exports. The high obstacles associated with the export revenue of enterprises reflect the stringent demands of global market competition on the capabilities of innovation, while underscoring the critical driving role of the opening-up strategy in fostering innovation by enterprise. The technology market acts as the primary medium for translating basic research outcomes into industrial applications through transfer to enterprises. The volume of transactions of the technology market mirrors the efficacy of integrating innovation with industrial innovation. The following indicators highlighted structural deficiencies in the innovation ecosystem as secondary obstacles: The number of high-tech enterprises reflected the insufficient cultivation of entities of innovation, their total industrial output reflected a low degree of industrialization in terms of achievements, and the number of authorized patent applications per 10,000 people characterized the efficiency of the output of innovative. These metrics collectively underscored fundamental challenges, both in fostering the entities of innovation and translating research into tangible outcomes.

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanism of Formation of Disparities in Regional Distribution of Capability for Innovation

A distinct geographical clustering of the capacity for innovation was observed in this study, with eastern provinces such as Shanghai and Jiangsu demonstrating significantly higher levels, while western regions like Qinghai and Tibet lagged considerably behind. The economic outputs of Shanghai and Jiangsu further underscore their dominance. The revenue from enterprise exports reached 1.78 trillion RMB in Shanghai and 11.48 trillion RMB in Jiangsu in 2023. The high-tech industries of the latter constituted 50.7% of its total output in 2024, and all of its 13 prefecture-level cities were the sites for national advanced clusters of manufacturing. In 2024, the permanent populations of Jiangsu and Shanghai were 85.26 million and 24.8745 million, respectively, with their GDPs at 13.7 trillion RMB and 5.39 trillion RMB. Their per capita GDPs stood at 1.607 million and 2171 million RMB, respectively, significantly higher than those of other regions in the Yangtze River Basin. Ye et al. [47] have noted that the intensity of innovation is positively correlated with the urban population and per capita GDP, a conclusion that is corroborated by our findings. Moreover, Shanghai and Jiangsu Province were supported by strong transactions in the technology market and a large number of patent grants per 10,000 people. The turnover of Shanghai’s technology market reached 464.2 billion yuan in 2023, while Jiangsu recorded 52 patent grants per 10,000 people. Zhao et al. [48] have confirmed that geographical proximity positively influences regional innovation in China. The synergistic “Shanghai–Suzhou science and technology cluster” exemplifies regional integration by optimizing its resource allocation through complementary strengths. Han et al. [49] have attributed Shanghai’s sustained leadership in innovation to its unique confluence of economic vitality, industrial maturity, resource abundance, and excellence in R&D.

On the contrary, such low-performing regions as Qinghai lagged behind owing to weaker economic development, resource dependence, insufficient foundational investment, a shortage of talent, geographical constraints, and delayed policy implementation. Qinghai Province and the Tibet Autonomous Region housed only 126 and 279 high-tech enterprises, respectively, in 2023, accounting for approximately 1% of those in Shanghai. A total of only 4972 and 11,117 personnel were engaged in sci-tech activities in these two regions, respectively, far lower than the 1.2296 million in Jiangsu Province. Moreover, Qinghai had only 14 patent grants per 10,000 people in 2023, far below the 52 reported for Jiangsu. This highlights the concentration of knowledge and resources for innovation in select regions, and underscores the pronounced imbalance in this regard in the Yangtze River Basin. Zhao et al. [50] have noted that human capital plays a pivotal role in accumulating high-quality labor and increasing the input to innovation. These regions are limited by the insufficient development of their high-tech industries and a scarcity of talent for scientific research [18]. This suggests that the western region has a weak foundation in innovation in science and technology.

4.2. Factors Influencing Capacity for Innovation

The export revenue of enterprises, volume of transactions in the technology market, and number of high-tech enterprises were not only assigned the largest weights of all indicators, but were also identified as among the top constraints on regional innovation. Export-oriented enterprises that are deeply integrated into the global division of the labor network generally demonstrated higher productivity, and consistently outperformed non-exporting enterprises on such metrics of innovation as investment in R&D and the efficiency of patent publications [51]. We also noted a particularly positive impact of the efficiency of innovation of China’s high-tech enterprises on state-owned enterprises in regions with concentrated resources for innovation [52]. Chinese enterprises are currently evolving from low-value-added segments to high-value-added domains amid globalization. However, the export activities of China’s industrial enterprises lack stability and continuity, with a relatively low ratio of continual exporters and high-tech products. In 2024, high-tech products accounted for 18.2% of China’s total export merchandise. Both the capacity of enterprises to drive an upgrade in exports through innovation, and their dominance in global value chains need to be strengthened. Hence, the competitiveness of products exported by enterprises constitutes the core bottleneck restricting innovation in the Yangtze River Basin.

As they are critical drivers of the innovation-driven strategy for development, the transformation of scientific and technological achievements is vital for enhancing economic competitiveness, accelerating industrial upgrade, and ensuring sustainable development. However, such growth is constrained by regional disparities, with the eastern region leading and the west lagging. This means that the ratio of technology transactions to the GDP is a key challenge for new productive forces [53,54]. A vibrant technology market reflects frequent engagements between the suppliers and demanders of technology. In recent years, the Chinese government has provided appropriate incentives and support for activities of technology transfer to facilitate the circulation of knowledge of basic research. In the reverse pathway of innovation, the technology market feeds back into basic research to enhance researchers’ insights into market dynamics, and to enable an appropriate alignment between the outputs of basic research and cutting-edge industrial applications. In 2024, the transaction value of national technology contracts reached 6.8 trillion yuan, marking an 11.2% year-on-year increase, and surpassing the target set in the 14th Five-Year Plan for the technology factor market ahead of schedule. Therefore, sustained policy support and targeted regional interventions to optimize the match between supply and demand remain essential to foster the balanced and robust growth of China’s technology market.

High-tech enterprises are characterized by advanced technologies and high value-added products, and are thus critical engines for qualitative growth [55]. According to data from the National Bureau of Statistics, the number of high-tech enterprises in China reached 463,000 in 2024. Their development remains starkly uneven, however. The downstream area of the Yangtze River Basin has forged a self-reinforcing cycle of the agglomeration of innovation, and hosts 74 (38 in Jiangsu and 36 in Shanghai) Fortune 500 HQs. On the contrary, the central/western regions lag considerably behind. Xia et al. [56] have identified two root causes of this divergence: the effectiveness of the intellectual property regime, and the capacity for technological commercialization. These factors explain why upstream provinces struggle to convert their inputs to research (e.g., patents) into economic outputs (e.g., industrial value). A systematic framework that features the “standards for cultivation, developmental support, and factor-related guarantees” should be established to cultivate innovation-driven enterprises, with tiered R&D subsidies for high-tech enterprises and proportional R&D funding allocated based on revenue.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

This study used data from 11 provinces and municipalities within the Yangtze River Basin to establish an index to evaluate their capability for science and technology innovation. We used the entropy-weighted TOPSIS method, along with the gray model, Gini coefficient, and obstacle degree model to empirically analyze the spatiotemporal evolution of this capacity and the obstacles to it. The key findings can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- The revenue from enterprise exports (X12), turnover of the technology market (X10), and number of high-tech enterprises (X4) had weights of 0.11, 0.10, and 0.083, respectively, and emerged as the most critical factors influencing the capability for innovation. Secondary indicators included the total industrial output of high-tech enterprises, number of patents authorized per 10,000 people, and number of personnel engaged in science and technology activities. The output of innovation was identified as the key dimension for measuring the capability for innovation.

- (2)

- The index of science and technology innovation of the 11 provinces and municipalities in the Yangtze River Basin underwent a steady rise from 2008 to 2023. Jiangsu Province and Shanghai Municipality, in the lower reaches of the Yangtze River, attained medium and relatively high levels of science and technology innovation, respectively. The growth in this capability was slightly slower for provinces in the middle reaches, including Jiangxi, Hubei, and Hunan, which gradually advanced from an extremely low level to relatively low and medium levels. The upper reaches have slowly climbed from an extremely low level to a relatively low one, and lag behind the middle and lower reaches. From an overall regional perspective, the index of innovation of the Yangtze River Basin presented a gradient disparity of “high in the east and low in the west,” and exhibited distinct characteristics of regional agglomeration.

- (3)

- The results of gray prediction showed that the level of science and technology innovation of each province and municipality in the Yangtze River Basin will continue to increase from 2024 to 2033. Their capabilities will improve to relatively high and extremely high levels. Regions such as Hubei and Anhui, following closely behind Jiangsu and Shanghai, are expected to join the ranks of provinces with high levels of scientific and technological innovation. The capabilities of Hunan, Sichuan, Chongqing, and other areas will steadily rise to a medium level as well. However, the imbalance in regional scientific and technological innovation may intensify on the whole.

- (4)

- The results of the Gini coefficient revealed that regional differences in the level of scientific and technological innovation of the basin first decreased and then increased. Cross-regional scientific and technological innovation in the upper, middle, and lower reaches of the Yangtze River exhibited the typical coexistence of significant differentiation and gradient spillover effects. The order of contributions to these differences was “inter-regional differences > intra-regional differences > super-variable density.”

- (5)

- The results of the obstacle degree model showed that the output of innovation had the most significant impact on the index of science and technology innovation. The five most influential obstacles were revenue from enterprise exports > turnover of the technology market > number of high-tech enterprises, their total industrial output, and number of patents applied authorized per 10,000 people.

The primary significance of this study lies in its methodological contribution on the novel integration of four complementary models (Entropy-TOPSIS, Dagum Gini coefficient, Gray Prediction, Obstacle Degree) into a single analytical chain. This allows for a more comprehensive analysis from comprehensive evaluation to dynamic trend analysis, obstacle diagnosis, and future forecasting than is typically achieved in studies employing a single methodology. The integrated analytical framework proposed here offers a replicable template for diagnosing regional innovation imbalances on a global scale. However, we identified several limitations that suggest directions for future research in the area. Our analysis was constrained by its focus on 11 provinces/municipalities in the Yangtze River Basin and temporal coverage over the period from 2008 to 2023, which limited the generalizability of our findings. While our framework of evaluation incorporated key socioeconomic factors, it omitted important demographic and labor market-related indicators, like population aging (projected to increase from 310 to 400 million elderly people by 2030) and the unemployment rate (5.1% in 2024). Previous research [57] has confirmed that these factors significantly impact regional innovation. These structural shifts in China’s developmental context may profoundly influence its patterns of innovation. Future studies should expand their geographical and temporal coverage, while adjusting their frameworks of evaluation to incorporate demographic changes and employment dynamics. Methodologically, employing spatial econometric models with panel data can better capture spatial autocorrelation and lag effects in regional capabilities of innovation across the Yangtze River Basin.

5.2. Recommendations

Based on our findings, we have the following policy recommendations over four dimensions.

- (1)

- The government should establish a balanced mechanism of investment in regional innovation. To address uneven investment in innovation in the Yangtze River Basin, we propose a “Central and Western Innovation Fund” co-funded by the central government and provinces/cities. It should focus on supporting central and western regions in their R&D infrastructure and key technological breakthroughs. A systematic framework of standardized cultivation, developmental support, and factor-related guarantee should be built to cultivate innovative enterprises. This should involve tiered R&D subsidies for high-tech enterprises, with funds matched to the revenue. This can improve the quantity and quality of their output through professional training, optimized fiscal support, and standardized certification.

- (2)

- The government should establish a cross-regional factor circulation system, and the relevant efforts should focus on dismantling administrative barriers and facilitating the free flow of the elements of innovation. We propose creating a unified “Yangtze Innovation Corridor” to enable the seamless interprovincial movement of technology, talent, and capital. For instance, it should develop a “Yangtze Technology Exchange Big Data Platform” to integrate inter-provincial patent and data resources, improve the efficiency of technology transfer, and build a three-tier network of innovation consisting of the downstream “Shanghai-Jiangsu” core zone, the midstream “Hubei-Hunan-Jiangxi” collaborative zone, and the upstream “Sichuan-Yunnan-Chongqing” expansion zone. This framework can transform educational and human capital-related advantages into innovation-driven developmental benefits through the optimized allocation of resources for research and a shared infrastructure of innovation. This can in turn improve the basin’s capacity for science and technology innovation.

- (3)

- The government should enhance the independent capabilities of innovation in the middle and upper reaches (particularly the upper reaches) of the Yangtze River Basin. The following measures should be implemented to this end. First, it should strengthen incentives for enterprises to innovate and deepen university-industry collaboration by establishing joint laboratories between central/western universities and research institutions of the Yangtze River Delta to cultivate market-driven R&D talent. Second, the government should optimize the ecosystem of the technology market by supporting professional intermediaries and rewarding organizations that facilitate cross-provincial technology transactions. Third, it should develop collaborative “technology pilot bases” between upstream and downstream regions and implement profit-sharing mechanisms to balance the input to and output of innovation. Special support should be provided to less-developed border regions (Tibet, Qinghai, and Yunnan) through financial, material, and human resource-related incentives to boost their capacity for innovation and efficiency of output.

- (4)

- The government should encourage enterprises to participate in global trade and technology transfer, as this can enhance their quality and diversity of innovation, drive upgrades in their exports, and strengthen the global value chain. Moderate support should be provided to activities of international exchange and technology transfer to facilitate the flow of knowledge of basic research. Priority should be given to high-tech enterprises conducting “product innovation” (such as in computer chips and biopharmaceuticals) and medium- and low-tech enterprises pursuing “qualitative innovation” (such as in machinery manufacturing and new materials). Moreover, differentiated policies for export subsidies need to be formulated for these two types of innovation. On the demand side, enterprises should be guided to become the main body of technology absorption and transformation. On the supply side, universities and research institutions should be encouraged to conduct market-oriented R&D, while professional institutions should be guided to provide precise services to match supply and demand on the service side. This can expedite the development of a thriving ecosystem for the technology market.

In conclusion, systematically addressing the unbalanced development of science and technology innovation in the Yangtze River Basin requires a comprehensive approach that can balance the investment in innovation, facilitate factor mobility, strengthen regional capabilities of innovation, and deepen international cooperation. This integrated strategy will provide sustainable momentum for high-quality development throughout the basin.

Author Contributions

G.L.: Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing—original draft. S.Z.: Methodology, review and editing, Supervision. X.L.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing—original draft. X.Z.: Methodology, Writing—review and editing, Funding acquisition. All authors contributed to results interpretation and paper writing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Hubei Provincial Department of Technology/Education (Project No. 2023EHA010; 22ZD048) and National Natural Science Foundation (Project No. 42477427).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the contributions of the reviewers for this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The definition of the selected science and technology innovation indicators.

Table A1.

The definition of the selected science and technology innovation indicators.

| Indicator | Definition |

|---|---|

| number of personnel involved in S&T activities | Personnel in the survey unit who are directly engaged in (or participate in) scientific and technological activities during the reporting year, as well as those specifically engaged in the management of S&T activities and those providing direct services for S&T activities |

| full-time equivalent of R&D personnel per 10,000 people | The workload calculated based on the actual time spent on R&D activities by R&D personnel per 10,000 people |

| number of institutions of higher education | Full-time universities, independent colleges, higher specialized colleges, higher vocational schools, and other institutions (including independent branches and college preparatory programs) that are established in accordance with state-prescribed standards and approval procedures, primarily enroll high school graduates through the national unified entrance examination for regular higher education institutions, and provide higher education |

| number of high-tech enterprises | Enterprises recognized by relevant national departments (such as science and technology, finance, and tax authorities), typically including both enterprises within high-tech zones and certified enterprises outside these zones |

| government’s financial investment in science and technology as a ratio of the GDP | The proportion of government expenditure on science and technology to the Gross Domestic Product |

| internal expenditure on R&D as a ratio of the GDP | Refers to the proportion of actual expenses incurred by survey units for intramural S&T activities during the reporting year, including outsourcing processing fees, to the Gross Domestic Product |

| expenditure on financial education as a ratio of the GDP | The proportion of government expenditure on education to the Gross Domestic Product |

| revenue of high-tech industries from product sales | The total revenue earned by high-tech enterprises from selling self-developed or produced high-tech products within a certain period |

| total industrial output | The total value of industrial end-products produced or industrial services provided by high-tech enterprises within a certain period |

| volume of transactions in the technology market | The total contract value of transactions in the technology market within a certain period |

| number of patents per 10,000 people | The number of patents granted per 10,000 people |

| export income of enterprises | The total foreign exchange income earned by enterprises from selling goods or services abroad |

| proportion of revenue from new product sales as part of the business income of industrial enterprises above a designated size | The percentage of sales revenue from new products developed in the last three years to the total operating revenue in enterprises that meet the annual revenue threshold |

| number of published S&T papers | Reports of scientific research results published by researchers in domestic or international academic journals or conferences |

| year-end loan balance of financial institutions | The total amount of loans issued by financial institutions such as banks and credit cooperatives within the region to enterprises and individuals that have not been repaid by the end of the year |

| year-end number of mobile phone users | Refers to various types of telephone subscribers who have completed registration procedures at the business outlets of telecommunications operators, accessed the mobile phone network through mobile telephone switches, and occupy mobile phone numbers |

| mileage of graded highways | Refers to the mileage of highways that have actually met the standards specified in the “Technical Standards for Highway Engineering JTJ01-88” within a certain period and have been officially accepted and put into use by the highway authorities |

| number of college students per 10,000 people | The number of students enrolled in regular higher education institutions per 10,000 people |

| number of books in public libraries per 100 people | The number of books in public libraries per 100 people |

| number of fixed-line phone and Internet users | The number of subscribers with fixed telephone or fixed broadband access, mobile phone (SIM card) subscriptions, and internet access via any means (mobile data, Wi-Fi, etc.). |

| per capita urban area of road | The average road area per person |

References

- Jiao, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, S. The secrets to high-level green technology innovation of China’s waste power battery recycling enterprises. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 375, 124343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Wang, Y. Do circular innovations and carrying capacity of natural environment enhance circular economy in the European Union? Evidence from simulation and machine learning methods. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zu, X.; Ni, G.; Hu, R. AI technology innovation, knowledge management and corporate environmental sustainability: Evidence from Chinese patent data. Technol. Soc. 2025, 83, 102984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J. Evaluation and spatial characteristics analysis of Chinese port economy innovation impetus. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 104, S601–S604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ye, Y.; Huang, Z. Synergistic development in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area: Index measurement and systematic evaluation based on industry-innovation-infrastructure-institution perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balland, P.-A.; Boschma, R. Do scientific capabilities in specific domains matter for technological diversification in European regions? Res. Policy 2022, 51, 104594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Yang, X.; Yu, Z. Effect of basic research and applied research on the universities’ innovation capabilities: The moderating role of private research funding. Scientometrics 2021, 126, 5387–5411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhao, S.; Xi, Y.; Liu, N.; Xu, X. Relating science and technology resources integration and polarization effect to innovation ability in emerging economies: An empirical study of Chinese enterprises. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 135, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yin, H.; Fan, F.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, H. Science and technology insurance and regional innovation: Evidence from provincial panel data in China. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2024, 36, 746–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziallas, M.; Blind, K. Innovation indicators throughout the innovation process: An extensive literature analysis. Technovation 2019, 80–81, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szopik-Depczyńska, K.; Cheba, K.; Bąk, I.; Kędzierska-Szczepaniak, A.; Szczepaniak, K.; Ioppolo, G. Innovation level and local development of EU regions. A new assessment approach. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronica, M.; Fazio, G.; Piacentino, D. A micro-founded approach to regional innovation in Italy. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 176, 121494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodny, J.; Tutak, M. Assessing the level of innovation of Poland from the perspective of regions between 2010 and 2020. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zheng, J.; Shi, X.; Li, R. Analysis of science and technology innovation capabilities and influencing factors of the five less-developed provinces of northwestern China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.-F.; Chu, P.-Y.; Lu, S.-T.; Chen, W.T.; Tien, Y.-C. Evaluation of regional innovation capability: An empirical study on major metropolitan areas in Taiwan. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2022, 28, 1313–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.-L.; Xu, R.-Y.; Cheng, Y.-H.; Miao, Z.; Sun, H.-P. Understanding the overall difference, distribution dynamics and convergence trends of green innovation efficiency in China’s eight urban agglomerations. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 148, 110101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L. Innovation efficiency evaluation based on a two-stage DEA model with shared-input: A case of patent-intensive industry in China. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 70, 1808–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, Y. Grey clustering analysis of provincial scientific and technological innovation capability mainland. J. Grey Syst. 2023, 35, 130. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, D. Research of the construction of regional innovation capability evaluation system: Based on indicator analysis of Hangzhou and Ningbo. Procedia Eng. 2017, 174, 1244–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Jiang, X.; Xiang, K.; Hu, Y. Regional disparities and dynamic evolution of marine science and technology innovation in China. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2025, 87, 104213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zhou, N.; Zhao, X.; Yang, S. The impact of artificial intelligence on corporate green innovation: Can “increasing quantity” and “improving quality” go hand in hand? J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 376, 124439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, S.; Cui, X. Spatio-temporal evolution and drivers of coupling coordination between digital infrastructure and inclusive green growth: Evidence from the Yangtze River economic belt. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 376, 124416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J. Health evaluation and key influencing factor analysis of green technological innovation system. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 77482–77501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zou, Y.; Li, M. Dynamic evaluation of the technological innovation capability of patent-intensive industries in China. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2022, 43, 3198–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, K. Evaluation on Regional Scientific and Technological Innovation Capacity Based on Principal Component Analysis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Logistics Engineering, Management and Computer Science (LEMCS 2015), Shenyang, China, 29–31 July 2015; Atlantic Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 1582–1587. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Liu, G. Coupling coordination analysis of low-carbon development, technology innovation, and new urbanization: Data from 30 provinces and cities in China. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1047691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Communications Highway Bureau. Ministry of Communications Standard of the People’s Republic of China: Technical Standards of Highway Engineering JTJ01-88, 1st ed.; People’s Communications Press: Beijing, China, 1994; p. 1.

- Guo, S.; Diao, Y. Spatial-temporal evolution and driving factors of coupling between urban spatial functional division and green economic development: Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1071909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagum, C. A new approach to the decomposition of the Gini income inequality ratio. Empir. Econ. 1997, 22, 515–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Dong, S.; Ren, G.; Liu, K. China’s urban green innovation: Regional differences, distribution dynamics, and convergence. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2023, 21, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Yalikun, T.; Duan, Z.; Yao, X. Regional disparities and variation sources decomposition of energy system resilience in China. Energy 2025, 330, 136644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, J. Ecological security early-warning in central Yunnan Province, China, based on the gray model. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 111, 106000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wei, Z.; Ren, J.; Luo, Z.; Zhou, H. Early-warning measures for ecological security in the Qinghai alpine agricultural area. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 9292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; He, Z.; Piao, C.; Chi, W.; Lu, Y. Research on subsidence prediction method of water-conducting fracture zone of overlying strata in coal mine based on grey theory model. Water 2023, 15, 4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Li, C. Coupling coordination and spatial–temporal evolution between high-quality development of construction industry and scientific and technological innovation. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 19857–19887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J. Impact assessment of green finance reform on low-carbon energy transition: Evidence from China’s pilot zones. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 110, 107654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Yan, J.; Li, P.; Guo, Y.; Huang, X.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, S.; Hu, Y.; et al. Regional sssessment at the province Level of agricultural science and technology development in China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.-H.; Van Nguyen, D.; Nguyen, T.-P.; Thi Nguyen, L.-A.; Thi Nguyen, T.-H.; Vu, T.; Le Hoang, H.-G. Income-dependent variations in innovation performance: Insights from sustainable economic development indicators. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2025, 11, 100478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, J.; Qi, R.; Wu, X.; Zhao, M.; Zhou, Y. High-tech enterprise manpower capital affects innovative performance on innovation performance simulation design research. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 32319–32334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xing, F.; Li, B.; Yakshtas, K. Does the high-tech enterprise certification policy promote innovation in China? Sci. Public Policy 2021, 47, 678–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Kim, J. The spatial spillover effect of technological innovation network in cities: A case of the high-tech industry of Yangtze River Delta. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2023, 27, 414–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, F.; Yang, S.; Huang, D. Heterogeneous human capital, spatial spillovers and regional innovation: Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Hsu, W.-L.; Zhang, T. Analysis on scientific and technological innovation capacity for the Yangtze river economic belt. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Manufacturing (ICAM), Yunlin, Taiwan, 16–18 November 2018; pp. 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, K.; He, F.; Liu, R. Does high-tech industry agglomeration promote its export product upgrading?—Based on the perspective of innovation and openness. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C. Temporal and spatial evolution of the science and technology innovative efficiency of regional industrial enterprises: A data-driven perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wu, Q.; Su, J.; Li, B. Sustainable coordination and development of S&T Innovation and new urbanization: An empirical Study of Cheng-du-Chongqing Dual-City Economic circle, China. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 33, 2847–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, G.; Cao, Z.; Zhou, S. The spatial distribution and synergistic effect of different innovation activities in Chinese cities: An analysis based on technology, design, and market activities. Appl. Geogr. 2025, 176, 103527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Wang, J. Proximity and regional innovation performance: The mediating role of absorptive capacity. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2024, 16, 1094–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; He, M.; Xie, H.; Ding, T. The impact of scientific and technological innovation on high-quality economic development in the Yangtze river delta region. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; He, P. Government spending efficiency, fiscal decentralization and regional innovation capability: Evidence from China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 84, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petković, S.; Rastoka, J.; Radicic, D. Impact of innovation and exports on productivity: Are there complementary effects? Sustainability 2023, 15, 7174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Han, J.; Zhan, J.; Wu, Y.; Sun, L. The impact of global value chain embeddedness on the innovation of high-tech enterprises. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 2025, 100, 104095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]