Abstract

With the growing financialization of energy markets, financial and energy security have become critical global concerns. This study overcomes the limitations of traditional methods in analyzing extreme events by adopting a conditional quantile spillover index approach. Using China’s energy market prices and financial sub-market pressure indices, it constructs Quantile Vector Autoregressive (QVAR) models for both traditional and new energy-finance systems to examine their time-varying risk spillovers. Key findings are: (1) A significant risk spillover effect exists within China’s energy-finance system. The energy market acts as the primary risk transmitter, driven by both industrial policy and market demand, while capital and foreign exchange markets are the main risk absorbers. (2) The system exhibits significant tail spillover and asymmetry. The traditional energy market is more sensitive to upside extreme risks, whereas the new energy market is more sensitive to downside extremes. (3) Uncertainties like supply demand imbalances, policy shifts, and changing domestic/international conditions are major volatility drivers. Supply demand issues primarily affect the traditional energy market, while policy adjustments trigger chain reactions in the new energy sector. Based on these insights, the paper proposes recommendations to prevent systemic risks and potential energy crises.

1. Introduction

Since the release of China’s “14th Five-Year Plan”, energy security and financial security have been identified as two of the country’s most pressing economic sustainability challenges [1]. Meanwhile, the gradual liberalization of financial markets, the expansion of cross-market financial products, and the deepening of mixed operations have strengthened the linkages among financial sub-markets, increasing the likelihood of cross-market risk transmission and amplifying systemic vulnerabilities [2]. In parallel, the diversification and financialization of energy derivatives—such as futures and options—have further embedded financial attributes into energy price formation, intensifying the interactions between energy markets and financial systems [3]. As energy-finance couplings become more complex, understanding how these dynamics influence the stability and sustainability of both energy and financial markets has become an essential research priority [4].

Against a backdrop of global economic volatility, climate change, and persistent energy pressures, China is experiencing a profound restructuring of its energy system. As the world’s second-largest economy and a major energy consumer, China faces the dual imperative of ensuring energy security while accelerating a green, low-carbon, and sustainable energy transition [5]. Although traditional fossil fuels—especially coal—remain dominant, the current energy structure characterized by “abundant coal, limited natural gas, and insufficient oil” is increasingly incompatible with long-term sustainable development goals [6]. In contrast, clean and renewable energy sources such as wind, solar, and nuclear power are becoming indispensable to China’s electricity generation. The rapid expansion of renewable and low-carbon energy not only facilitates China’s dual-carbon targets but also reshapes the interactions between energy and financial sub-markets, creating new channels for risk spillovers that may affect market stability and the broader sustainability of the energy–finance nexus [7].

Against this backdrop, this study systematically incorporates China’s rapidly developing new energy market into a broader analytical framework for energy–finance sustainability by employing a Quantile Vector Autoregression (QVAR) model combined with the spillover index approach developed by Ando et al. [8]. In doing so, it advances research in sustainability and energy finance. By examining the dynamic linkages among China’s traditional energy markets, new energy markets, and financial submarkets, and by identifying asymmetries, nonlinearities, and tail dependencies in cross-market risk transmission, the study provides a more nuanced depiction of how interdependencies in energy finance evolve under different market conditions. The findings carry important implications for building a more resilient and sustainable energy–finance system, offering policy insights for mitigating systemic risk, strengthening financial governance, and promoting coordinated development in the transition toward green energy. Throughout this process, the study presents strong empirical evidence that deepens the understanding of the evolving mechanisms underlying China’s energy–finance nexus. It contributes to the formulation of effective policies to enhance cross-market resilience and supports theoretical and policy discussions on constructing a stable, efficient, and sustainable energy and financial system under China’s carbon-neutrality goals.

2. Literature Review

Financial stress, first proposed and defined by Illing and Liu (2006) [9], refers to the potential loss expectations arising from economic agents facing unpredictable changes in financial markets and institutions. The most severe financial stress can lead to a financial crisis. The main methods for measuring systemic risk include structured methods, simplified methods, and composite index methods, among which the Financial Stress Index (FSI) is a typical example of the composite index approach [10]. Early studies, such as Illing and Liu [9], developed the Financial Stress Index (FSI) for Canada. Following this, financial stress indices for various regions have subsequently been constructed, including the STLFSI [11], KCFSI [12], and AE-FSI [13], among others. In recent years, scholars have further developed the Composite Indicator of Systemic Stress (CISS) [14] and other related indicators. Building on this, Chinese scholars have gradually developed financial stress indices tailored to the Chinese market [15,16,17]. Although scholars have differing interpretations of the concept of financial stress and there are variations in the choices of markets, indicators, and index aggregation methods when constructing these indices, all studies collectively demonstrate the widespread presence of financial stress. Since the existence of financial stress is an objective fact, measuring the contagion and spillover effects of financial stress has become an important topic for further scholarly attention and research. Currently, there is a wealth of research on financial market stress both domestically and internationally. A large number of scholars have conducted research and analysis on the cross-regional and cross-country spillover effects of financial stress and its transmission channels [18,19,20,21]. In contrast, although scholars have used methods like multivariate GARCH models and DY spillover indices to explore the transmission of volatility risks between financial markets [22,23,24,25], only a few scholars, including Chen and Semmler [26] and Soltani and Boujelbène Abbes [27], have constructed financial market stress indices to study the cross-market spillovers of financial stress.

As a crucial component of the global economy, the energy market not only impacts national energy security and economic development but also provides rich perspectives and challenges for academic research. In the new era, the international situation is facing “unprecedented changes in a century”, and research on cross-market energy dynamics under these global trends has become a hot topic of focus for scholars.

Research on the correlation between energy markets and financial markets primarily focuses on the degree of connection between the energy market and various financial sub-markets, with studies on the relationship between the energy market and the stock market occupying a significant portion [28,29,30]. In addition to the stock market, the correlation between the energy market and other financial markets has also received extensive attention. Ringstad and Tselika [31] studied the return spillover effects between green bonds, the clean energy market, and carbon prices, finding significant connectivity between these markets in the short-term. Their research suggests that these markets offer diversification opportunities for both short-term and long-term investors, especially during periods of economic and political stability. Khalifa et al. [32] found that there are spillover effects between the energy market and the foreign exchange market, with the asymmetric effects in the oil market being significantly higher than those in the natural gas market. The volatility spillover effects in the oil market are more pronounced, and macroeconomic factors related to the business cycle may cause market volatility to exhibit jumps.

A review of existing research on the relationship between domestic and international energy markets and financial market stress shows that scholars have made multidimensional academic contributions on the interactions between financial markets and energy markets. However, there are still some gaps:

- Most studies primarily focus on the volatility risk spillover effects between financial markets, as well as the cross-border transmission and influence channels of financial stress between different regions and countries. However, research on the construction of financial stress indices and the cross-market spillover of financial stress remains insufficient.

- Research on the correlation between energy markets and financial markets has mostly focused on the spillover effects between traditional energy markets and financial sub-markets, with few scholars exploring the volatility spillover effects between financial market stress and new energy markets. The stability between the new energy market and the financial market is crucial for the sustainable energy transition.

- Conventional methods, such as Granger causality tests, multivariate GARCH models, Copula theory, and the Diebold–Yilmaz (DY) spillover index [33], provide valuable insights into mean-based volatility spillovers but are limited in capturing tail risks and extreme events, which are crucial for assessing risks in sustainable energy-finance systems [34,35].

In light of this, this paper selected five representative financial sub-markets in China as the research objects: the money, stock, bond, credit, and foreign exchange markets. Ten key indicators from these five sub-markets were chosen to construct the financial stress indices for each sub-market, thus providing a comprehensive view of the financial risk status in these markets. Furthermore, the study employed a quantile vector autoregressive (QVAR) spillover index to measure time-varying risk spillovers and the dynamic evolution between China’s traditional energy-financial system and new energy-financial system under different market conditions, from the perspective of financial stress. This approach allows for a nuanced analysis of how financial pressures propagate across markets and affect sustainable energy systems. The potential marginal contributions of this article are as follows:

- This study utilizes the quantile vector autoregressive (QVAR) model with a conditional quantile spillover index method, which overcomes the limitations of the DY spillover index in capturing tail dependence and risk transmission during major events. Based on this method, the time-varying risk spillover effects between financial markets and energy markets are examined from the perspective of financial pressure. Additionally, financial pressure indices for various financial submarkets are constructed, providing a quantitative tool for assessing financial risks in the energy sector.

- Against the backdrop of energy transition, this study introduces the renewable energy market into the field of energy finance for the first time. Empirical analysis explores the heterogeneity of financial stress impacts on both traditional and renewable energy markets, shedding light on how financial stress propagates through energy-financial systems and its implications for green energy transition, low-carbon development, and sustainable financial governance.

3. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

Under different financial market conditions, energy price fluctuations exhibit significant heterogeneity. In the short-term, energy prices are mainly influenced by market supply and demand, domestic and international geopolitical conditions, and global climate changes. In the long-term, the trajectory of energy prices is determined by emerging energy technologies, adjustments in energy policies, and ecological and environmental factors. With the continuous growth in demand for clean energy, traditional energy prices may face downward pressure. Additionally, energy prices are affected by technological progress, policy changes, and the financialization and globalization of energy markets. Therefore, a deep understanding and systematic analysis of how these factors affect energy prices under different market conditions is of great significance for ensuring China’s energy and financial security, promoting the transformation of energy productivity, and constructing a stable and coordinated energy–financial market relationship.

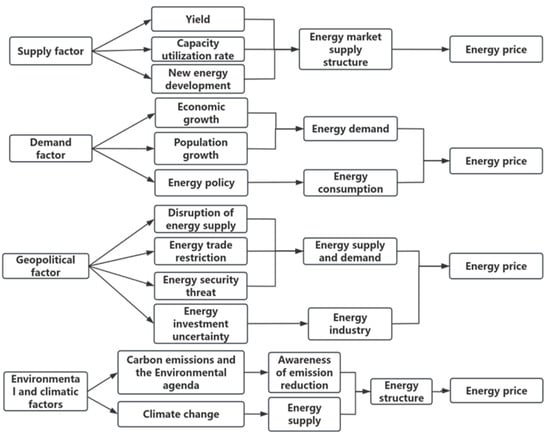

Based on this, the paper summarizes the transmission mechanisms between energy and financial markets as follows, as shown in Figure 1, and proposes corresponding research hypotheses.

Figure 1.

The transmission mechanisms between energy and financial markets.

3.1. The Supply Side Transmission Mechanism

As a commodity, energy prices reflect their market value. According to market price determination theory, market prices are ultimately driven by changes in supply and demand fundamentals. From the supply perspective, the main factors affecting energy prices include production levels, capacity utilization, and the development of new energy sources. Production levels are influenced by exploration technology, resource reserves, and policy constraints, and fluctuations in production directly affect market supply, thereby driving price changes. Capacity utilization affects the stability and efficiency of energy supply. With the rapid integration of solar, wind, and other new energy sources into the energy production system, the market supply structure is changing. Extreme supply shocks, such as a sudden decline in traditional energy production or rapid new energy rollout, may trigger tail-risk events and transmit them to financial markets.

Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1:

Supply side factors (production levels, capacity utilization, and new energy development) cause heterogeneous fluctuations in energy prices, and extreme supply shocks generate significant cross-quantile risk spillover effects in energy–financial markets.

3.2. The Demand-Side Transmission Mechanism

Energy demand is influenced by economic growth, population changes, and energy policies [36]. Rapid economic development and accelerated industrialization may push energy demand upward, creating upward pressure on prices; population growth directly increases energy demand in transportation, residential electricity, and industrial production; policy adjustments can alter preferences for traditional energy or promote clean energy, leading to asymmetric price fluctuations. Extreme shocks on the demand side often cause nonlinear responses of energy prices across different quantiles. For example, a sudden surge in industrial energy use may trigger a sharp rise in upper-quantile prices, while the promotion of new energy policies may suppress lower-quantile prices, reflecting distribution-dependent and tail-risk characteristics.

Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2:

Demand-side factors (economic growth, population trends, and energy policies) exert heterogeneous effects on energy prices, and extreme demand shocks trigger significant tail-risk propagation within the energy–financial system.

3.3. Geopolitical Transmission Mechanism

Geopolitical events (such as conflicts, sanctions, and political instability) typically cause sudden disruptions in energy supply, leading to extreme price fluctuations. Regional conflicts or trade restrictions may result in energy shortages, pushing market prices upward and transmitting risk to financial markets. Increased policy uncertainty and investment risks can amplify price volatility and cross-market tail effects. Additionally, security threats such as terrorism and piracy may impact energy transportation safety, exacerbating uncertainty in supply disruptions and reflecting systemic vulnerability under extreme market conditions.

Based on the above analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3:

Geopolitical risks trigger asymmetric cross-market spillover effects in the energy–financial system, and extreme market conditions amplify tail-risk impacts.

3.4. Environmental and Climate Transmission Mechanism

Environmental and climate factors, including extreme weather events and carbon-reduction policies, create simultaneous shocks to energy supply and demand, leading to significant tail fluctuations in prices [37]. Extreme weather events (such as hurricanes or floods) may damage energy infrastructure, causing sudden supply reductions; the sudden implementation of carbon emission regulations or reduction policies may suppress traditional energy demand while accelerating the growth of new energy. Such shocks exhibit nonlinear and quantile-dependent characteristics, with asymmetric price responses in the upper and lower quantiles. Extreme events related to environmental and climate factors not only affect energy prices but may also transmit systemic risks to financial markets.

Based on the above analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4:

Environmental and climate factors generate tail-dependent risk spillovers in the energy–financial system, and extreme events amplify the impact of sustainability shocks on energy prices.

4. Methodology and Research Design

4.1. Methodology

This study employed the Quantile Vector Autoregression (QVAR) model to capture the dynamic interactions between the energy and financial markets under different risk conditions. Unlike traditional models such as the DY spillover index model and VAR, QVAR estimates interdependencies across different quantiles, allowing for the analysis of extreme market behaviors and tail spillovers. Given the presence of nonlinearities and tail dependence in both the energy and financial markets, QVAR provides a more comprehensive framework to describe heterogeneous and asymmetric risk transmission, making it particularly suitable for this study. Therefore, the following section introduces the Quantile Vector Autoregressive (QVAR) model.

To calculate all spillover indices, we first estimated the quantile vector autoregressive model in this paper:

In this formula, and are endogenous vectors of the dimension, represents the lag length of the model. The value of is between , indicating the quantile level we intend to study. is a conditional mean vector of dimension. is the coefficients matrix of dimension. represents the error vector of dimension, which has a variance covariance matrix of dimension, and meet the condition of .

In order to convert the model to a model, which is more suitable for infinite order, Wald’s decomposition theorem is applied to Equation (1), and it comes out as:

To measure the spillover indices in the quantile time domain, it is necessary to further measure the variance decomposition (GFEVD) of the H-step generalized prediction error proposed by Koop et al. [38] and Hashem et al. [39], that is:

where is the proportion of the contribution caused by the impact of variable to the variance of the H-step prediction error of variable at the quantile in the prediction period . is the spillover level of variable to variable in the quantile time domain. indicates that the selection column vector, the unit column vector with the value of 1 is taken from the element. This normalization makes Equation (3) satisfy the following two conditions: , .

Furthermore, in order to measure the level of directional spillover under different conditional quantiles, the following directional spillover index is constructed:

In the equation above, is the total spillover index of the variable, collecting information from to all other variables and calculating the total spillover level to other variables. is the total spillover index of the variable , to obtain information from all other variables to the variable , and to calculate the total spillover level of the variable from other variables.

Take the difference between Equations (4) and (5), i.e., take the total spillover of the variable to other variables , minus the total overflow of the variable from all other variables , and define it as the net spillover index of the variable , measuring the net impact of the variable in the system we analyzed.

Finally, the overall degree of correlation between all variables of the system needs to be measured, i.e., the total spillover index (TOTAL). In this paper, we used a measurement method adjusted based on Chatziantoniou et al. [40] and improve the quantile time domain index to the quantile frequency domain index by spectral representation of variance decomposition, so that the adjusted total spillover index (TOTAL) ranges between [0,1]:

This indicator is often used as a proxy for market risk, as the higher the TOTAL, the higher the degree of correlation of the variable system.

4.2. Variable Selection and Descriptive Statistics of Indicators

To systematically measure the risk spillover effect between the energy market and the financial stress of China, and deeply analyze their linkage relationship, this paper selected coal price as a proxy variable for the price of China’s traditional energy market in the field of traditional energy according to the characteristics of China’s energy structure. In the field of new energy development, photovoltaic power generation is the most widely popularized in China currently, and silicon is the most ideal solar cell material. Therefore, choosing the market price of domestic polysilicon as the proxy variable of China’s new energy price can be more in line with the current situation of domestic energy economic development. At the same time, this paper draws on the construction method of the EM-FSI index [41], combined with relevant research by Xu and Li [42] and other scholars, to develop the Financial Stress Index (FSI) for China. Firstly, China’s financial market was subdivided into five sub-markets: Credit, Stock, Exchange, Bond, and Monetary. The relevant data were selected to construct the financial stress index of each sub-market, which were CFSI, SFSI, EFSI, BFSI, and MFSI. Secondly, the CRITIC weighting method was used to construct the stress index system of each Chinese financial sub-market. Finally, the synthetic indices were standardized. The stress indicators of each financial sub-market are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The index system of China’s financial sub-market stress index.

According to the availability of data, the sample period of each market data was from September 2011 to September 2022, and the data were derived from the Wind database “https://www.wind.com.cn/mobile/EDB/zh.html (accessed on 20 June 2025)” and the Choice database “http://choice.eastmoney.com (accessed on 20 June 2025)”. Prior to model estimation, the data were preprocessed to ensure comparability, stability, and robustness. First, potential outliers in each series were inspected using standardized Z-scores. Observations exceeding three standard deviations from the mean were examined, and no significant outliers were detected. To eliminate the possible influence of statistical caliber and dimensional differences on the research results, this paper adjusted the coal price and domestic polysilicon price to January 2011 as the base period and performed logarithmic difference processing on the energy market price series: , where the logarithmic rate of return is described as The descriptive statistics of the main indicators used in this paper are shown in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

As shown in Table 2, the skewness of CFSI, EFSI, and BFSI were 2.1293, 1.0432, and 0.9014, respectively, indicating a strong right skew. On the other hand, the skewness of Si was −0.8134, showing a significant left skew, while other indicators exhibited varying degrees of asymmetry. In addition, except for MFSI, the kurtosis values of the other indicators were significantly greater than 3, suggesting that the data have fat tails and sharp peaks, further indicating that the data did not follow a normal distribution. The results of the Jarque–Bera (JB) test also confirmed that the variables did not meet the normality assumption. Therefore, the estimates obtained through ordinary least squares (OLS) regression would not be robust [43]. To address this issue, this paper adopted a conditional quantile regression model, which is better suited for handling heteroscedasticity and non-normal data, and aligns more effectively with the data characteristics. Subsequently, ADF and PP unit root tests were used to detect stationarity. The results indicated that all variables rejected the unit root null hypothesis at the 1% significance level, suggesting that the processed data were stationary sequences and suitable for QVAR modeling.

4.3. Construction of the Financial System Stress Index

The construction of the financial stress indices for the submarkets of the financial system is as follows:

4.3.1. Credit Market Stress Index (CFSI)

Drawing on the research of Louzis and Vouldis [44], this paper constructed the Credit Market Financial Stress Index (CFSI). The selected indicators include: ① Bank System Beta Value: The banking system Beta value is estimated using the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). A 12-month rolling window is used to perform a regression analysis between the returns of the banking system index and the market returns. This Beta value is used to measure the market risk of the banking system. ② Bank Index Volatility: Refers to the GARCH (1,1) volatility of the bank index. ③ Idiosyncratic Risk: Refers to the portion of risk faced by banks that cannot be explained by systemic risk. It is calculated by regressing the bank index returns on market returns and obtaining the residuals of the model. The volatility of the residuals is the idiosyncratic volatility. The definition of the Credit Market Stress Index (CFSI) is:

Here, , , and represent the weights of each indicator. Referring to the relevant research by Deng and Xie [45] under the condition that the conditional variances of each indicator are equal, the weights are determined based on the inverse of the standard deviation of each indicator. Considering the time-varying nature of the sample, the standard deviations of each indicator in this section were estimated using a 12-month rolling window, and the same applies hereafter.

4.3.2. Capital Market Financial Stress Index (SFSI)

Based on the research of Park and Mercado [19], this paper constructed the Capital Market Financial Stress Index (SFSI). The selected indicators include: ① Inverted stock market return: Measured using the monthly negative returns of the stock market; ② Stock market volatility: Measured using the time-varying variance obtained from a GARCH (1,1) model based on the stock price index. The definition of the Capital Market Stress Index (SFSI) is as follows:

The weights of each indicator, and are calculated in the same way as in Equation (8).

4.3.3. Foreign Exchange Market Financial Stress Index (EFSI)

Based on the methodology for constructing the Financial Stress Index for Emerging Market Economies (EM-FSI) proposed by the IMF and relevant research by scholars such as Zhong and Liu [46], this paper selected the Exchange Rate Pressure Index (EMPI) as a proxy indicator to construct the Foreign Exchange Market Financial Stress Index (EFSI). The foreign exchange pressure index is used to measure the stress in the foreign exchange market, indicating that exchange rate volatility increases macroeconomic volatility. The construction model for the Foreign Exchange Market Financial Stress Index (EFSI) is as follows:

Here, and represent the monthly nominal exchange rate change and the monthly foreign exchange reserve change, respectively, while and represent the mean and standard deviation, respectively.

4.3.4. Bond Market Stress Index (BFSI)

Based on the relevant research of Xu and Li [42], this paper constructed the Bond Market Financial Stress Index (BFSI) by selecting two indicators related to the bond market: ① Inverted Term Spread: The difference between the short-term and long-term government bond yields. This paper measured it using the yield spread between the 1-year government bond and the 10-year government bond; ② Corporate Bond Spread: The yield spread between the 1-year AAA-rated corporate bond and the 1-year government bond. The definition of the Bond Market Stress Index (BFSI) is as follows:

The weights of each indicator, and , are calculated in the same way as in Equation (8).

4.3.5. Money Market Stress Index (MFSI)

Based on the relevant research by Louzis and Vouldis [44], this paper selected the TED spread as a proxy indicator to construct the Money Market Financial Stress Index (MFSI). The TED spread is the difference between the 3-month interbank lending rate and the 3-month short-term government bond yield, used to measure liquidity in the money market. The TED spread reflects the tightness of liquidity and changes in investor risk appetite. A higher TED spread indicates that banks are demanding a larger risk premium in interbank lending, and the rising cost of funds leads to increased pressure in the money market. However, due to the small scale of China’s government bond market, its discontinuous issuance periods, and the lack of 3-month short-term government bonds, the average yield of 3-month government bonds can be approximated by the 3-month time deposit rate.

5. Empirical Results and Analysis

The selection of an appropriate lag order is crucial for the QVAR (Quantile Vector Autoregression) model, as it can substantially affect the accuracy and robustness of the empirical results. To determine the optimal lag order p, this study employed the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the Schwarz Information Criterion (SIC). The empirical results indicate that for the traditional energy–financial system, both AIC and SIC suggest an optimal lag order of p = 2, whereas for the new energy–financial system, both criteria consistently support p = 1. Accordingly, to examine the dynamics of risk spillovers between the traditional and new energy markets and financial market pressures, this study constructed two QVAR models separately. Specifically, a second-order lag model and a first-order lag model were adopted for the two market systems, respectively. The variance decomposition period H of the prediction error was 10 for both.

5.1. Analysis of Static Spillovers Between Markets

In the first step, this paper examined the total static risk spillover(TOTAL), directional spillover effect (including spillover(TO) effect and spillover(FROM) effect), and net spillover effect(NET) of the energy market to various shocks in the middle state of financial market stress (based on the conditional mean and 0.5 quantile) and the extreme state of financial market stress (based on 0.05 quantile and 0.95 quantile).

5.1.1. Static Risk Spillover Analysis Based on the Conditional Mean

Table 3 shows the static risk spillovers of the energy–financial system based on the conditional mean under normal market conditions.

Table 3.

Static risk spillover effect based on conditional mean.

From the perspective of total spillover effects, the risk transmission between the traditional energy–financial system and the new energy–financial system is generally weak, with total spillover effects of 19.3% and 14.7%, respectively. Under normal market conditions, the risk transmission between the old and new energy markets and the Chinese financial market was not intense. The reason for this may be that both the energy market and the financial market in China have strong risk resilience under stable operation. On the other hand, risk measures based on conditional means may not adequately reflect the interconnections and risk spillovers between China’s energy and financial markets.

Regarding directional spillover effects, in the traditional energy–financial system, the risk spillover (27.02%) and spill-in (32.84%) from the capital market (SFSI) were the highest, followed by the credit market (CFSI), while the spillover and spill-in from the money market (MFSI) were relatively low. The risk spillover (5.55%) and spill-in (11.73%) from the traditional energy market were both lower than those from the financial sub-markets. In the new energy–financial system, the credit market (CFSI) had the highest risk spillover (27%), while the capital market had the highest risk spill-in (32.6%). The money market (MFSI) had the lowest spillover effect among the financial sub-markets (9.7%), and the spillover (6.1%) and spill-in (7.2%) from the new energy market were both relatively weak. From the above analysis, it is clear that the financial sub-markets, represented by the capital market and credit market, are not only the strongest risk-exporting markets but also the primary risk-receiving markets. This further indicates that markets with higher levels of risk spillover are more susceptible to shocks from other markets, while markets with weaker responses to uncertainty shocks from other markets also have relatively lower levels of risk input. This is consistent with the conclusion of Gong et al. [34]. Meanwhile, the energy market plays a smaller role in cross-market risk transmission and mainly serves as a risk receiver. The risk fluctuations of money market pressure are comparatively weak, which may be related to the fact that since China entered the new normal for economic development, the monetary policy has tended to be stable, and the monetary liquidity has remained in the range of low and medium levels and tends to be moderately tightened so that the money market risk could be controlled at a low level, which verifies the relevant view of Lv et al. [47].

In terms of net spillover effects, in the traditional energy–financial system, the capital market (SFSI) is the main net risk receiver (−5.82%) and serves as the primary risk input market for the financial market. In the new energy–financial system, the capital market (SFSI) is the largest net risk inflow (−19.4%), while the credit market (CFSI) is the largest net risk exporter (15.2%). This indicates that credit market stress is primarily characterized by risk spillovers, while capital market stress is mainly a result of risk inflows. It also reflects the mature level of financialization and the close risk linkage between China’s banking sector and the stock market. The stable operation and pressure relief of the credit and capital markets have a significant impact on the country’s energy financial system.

Having examined the static risk spillover based on the conditional mean, we next extend the analysis to different quantiles in order to capture the heterogeneous spillover effects under varying market conditions.

5.1.2. Static Spillover Analysis Based on Each Quantile

Based on the analysis above, this paper used the quantile index spillover method to further investigate the correlation and risk spillover effect between markets. Table 4 shows the static risk spillover effects of the traditional energy–financial system and the new energy–financial system based on various quantiles.

Table 4.

Static spillover effect based on each quantile.

By comparing the spillover effects based on conditional means and the 0.5 quantile, as shown in Table 3 and Table 4, it can be observed that the total spillover effect based on the conditional mean was stable between the old and new energy markets and the stress in China’s financial markets, while the risk measure based on the quantile 0.5 was more significant. The reason may be that, on the one hand, the spillover index based on the conditional mean is equivalent to the equally weighted average of the quantile regression estimation, while the spillover index based on the conditional median is only the quantile regression estimation when . As the latter is a robust Mestimation, it is less susceptible to outlier interference. On the other hand, the risk spillover between China’s energy and financial markets may have large extreme differentiation characteristics in different market conditions, which makes the difference in the two measurements significant. As the difference between the spillover measure based on the mean of the conditions and the median of the conditions, quantile variation may occur in the system network. The more pronounced the difference between the spillover indices based on the conditional mean and the conditional median, the greater the quantile variation will be [37]. Therefore, this further indicates that risk measures based on conditional means do not adequately reflect the interconnections and risk spillovers between China’s energy and financial markets, which is consistent with the conclusions of Li et al. [48] and other scholars. It is necessary to use the index spillover method based on quantile regression to examine the risk contagion ability of the system under different market conditions, so as to measure the spillover effect between markets more reasonably and rigorously.

As shown in Table 4, compared to the extreme states of financial market stress ( and ), the energy market’s sensitivity to risk shocks in the intermediate state ) of financial market stress was notably weaker across all spillover effect levels. In the traditional energy-financial system, the static total spillover in the intermediate state (, 51.35%) was smaller than the spillover effects in the extreme downward state (, 74.17%) and extreme upward state (, 78.15%). The same holds for the new energy-financial system. This preliminarily suggests that the instability of China’s energy-financial system is primarily driven by risk shocks under extreme financial market stress conditions. Additionally, in the intermediate state ) of financial market stress, the static total risk spillover level in the new energy-financial system (36.48%) was lower than that in the traditional energy-financial system (51.35%), whereas in the extreme financial market stress conditions ( and ), the static total risk spillover levels (76.04%, 78.84%) were higher than those in the traditional energy–financial system (74.17%, 78.15%). This indicates that the new energy–financial system exhibits more pronounced characteristics of extreme risk spillovers.

For the traditional energy–financial system, risk spillovers were strongest under conditions of extreme upward market stress (), that during periods of severe financial market pressure, risk transmission across different markets is most intense. This right-tail spillover phenomenon may stem from the high cyclicality and financialization of traditional energy markets. Under such stressed conditions, leveraged trading and herding behavior can be triggered, amplifying inter-market linkages and risk propagation. In addition, investors generally exhibit excessive optimism under upward market stress, further magnifying the transmission of risk. In contrast, in the new energy–financial system, although total spillovers were strongest under extreme upward market stress, net spillovers and directional spillovers were more pronounced under extreme downward market stress (), showing that the new energy market is more sensitive to downside risk. This may be related to the relative immaturity of the new energy market, lower liquidity, a higher proportion of retail investors, and strong policy dependence. During periods of downward market stress, market reactions to policy changes and uncertainty about future returns are more intense, thereby amplifying risk spillovers. This indicates that the new energy market is more prone to systemic risk when facing negative shocks.

Furthermore, both the capital market and the foreign exchange market exhibited static net risk inflows across the market states based on various quantiles. The traditional energy market was more sensitive to the risk shock of capital market pressure (, −28.94%) under extreme upward financial market stress conditions, while the new energy market showed a more pronounced response to the risk shock of foreign exchange market pressure (, −24.03%) under extreme downward financial market stress conditions. This indicates that in the energy–financial system, the capital market and the foreign exchange market are the main risk receivers. It was also found that the new energy market exhibited the largest static net risk spillovers across all market stress states (). This is mainly because compared to the traditional energy–financial system, the new energy–financial system, still in its development phase, is not yet mature, with greater uncertainty and instability between markets. Under risk shocks from extreme events, the static directional spillovers and net spillover effects in the new energy market were more pronounced, and its spillover effects exceeded those of the risk spillovers generated by the financial sub-markets, demonstrating a weaker capacity to resist external shocks [49].

An examination of the risk spillover levels of each market indicator at different quantiles revealed that the sub-markets that play a dominant role under different market stress states vary. Table 5 shows the dominant market under different market stress states. It can be observed that except for the new energy–financial system under the intermediate market stress state, the market with the largest directional spillover effect is usually also the largest net spillover market. However, the market with the largest directional spill-in effect is not necessarily the largest net spill-in market.

Table 5.

The Market Leading in Different Market Stress States.

5.2. Analysis of Dynamic Spillovers Between Markets

5.2.1. Dynamic Total Spillover Analysis at Each Quantile

After examining the static risk spillover effect between the energy market and the financial market pressure under different market conditions, the dynamic linkage relationship and risk spillover effect of the energy market and the financial market pressure in the full quantile and different quantile were further analyzed. Given the limitation of the data, this paper selected a rolling window based on a certain proportion of the sample length. Setting the rolling window to 36 better reflects the periodic changes and volatility of the data. The extreme conditional quantiles were set to and .

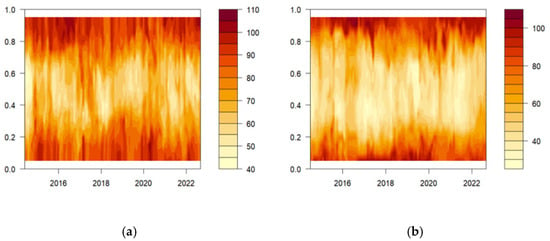

Figure 2 shows the dynamic total spillover effects of the energy–financial system at different quantiles, with warm and cold colors reflecting the differences in the degree of risk spillover linkage.

Figure 2.

The total spillover of the energy market dynamic in the full quantile under financial market stress: (a) The total spillover of traditional energy–financial System; (b) the total spillover of new energy–financial system.

From Figure 2, it can be seen that under extreme market stress conditions ( or the volatility and risk spillover levels of the traditional energy-financial system were higher. However, under intermediate market stress conditions , the risk spillover level significantly decreased. In contrast, the new energy–financial system exhibited more significant tail risk spillover characteristics, with the warm color distribution more concentrated, primarily in the and regions, and with a lower risk spillover level under moderate market stress. Table 6 shows the volatility range of the dynamic total spillover effects of the energy–financial system at different quantiles. From Table 6, it can be seen that the volatility ranges for the traditional energy–financial system and new energy–financial system at the 0.5 quantile (46.26–86.17%, 26.68–53.92%) were smaller than those at the 0.05 quantile (71.42–101.00%, 71.09–101.41%) and the 0.95 quantile (81.08–107.13%, 78.60–101.75%), which is consistent with the previous analysis and the color distribution in Figure 2. This further confirms that the instability of China’s energy–financial system is primarily due to risk shocks under extreme financial market stress conditions.

Table 6.

Volatility Range of the Dynamic Total Spillover Effects of the Energy–Financial System at Different Quantiles.

By combining Figure 2 and Table 6, and comparing the risk spillover levels at the two extreme quantiles, it was found that the highest risk spillover levels for both energy markets were concentrated at the 0.95 quantile (). This indicates that under extreme financial market stress, the energy–financial system exhibits pronounced right-tail spillover characteristics and asymmetry. Specifically, the maximum total risk spillover reached 107.13% for the traditional energy–financial system and 101.75% for the new energy–financial system, with the time concentration spanning from October 2015 to September 2016. The intense risk spillovers in the traditional energy market during this period can be attributed to multiple structural and behavioral factors. The sharp stock market volatility in late 2015, combined with supply side reforms in the coal industry at the beginning of 2016, created simultaneous shocks across energy and financial markets. Under extreme market stress, rapid price adjustments and increased leveraged trading amplified inter-market linkages, while investor herding behavior and over-optimism during upward market movements further intensified risk contagion. This is visually reflected in the warm-colored regions of Figure 2, providing preliminary confirmation of Hypothesis H1. For left-tail risk spillovers, the traditional energy market showed significant effects around April 2020 (), with the maximum tail risk reaching 101.00%, whereas the new energy market exhibited left-tail spillovers from March to April 2019, peaking at 101.41%. The heightened sensitivity of the new energy market to downside shocks can be explained by market immaturity, high policy dependence, and liquidity constraints. In March 2019, substantial reductions in subsidies for the new energy vehicle market triggered sharp declines in investor confidence. Similarly, the traditional energy market experienced strong negative shocks at the beginning of 2020 due to COVID-19–induced supply demand mismatches, falling prices, and volatile investor sentiment [50]. These factors collectively intensified risk spillovers under extreme downward market stress, highlighting the asymmetric nature of the energy–financial system and providing preliminary support for Hypothesis H2.

5.2.2. Dynamic Directionality Spillover Analysis of Each Quantile

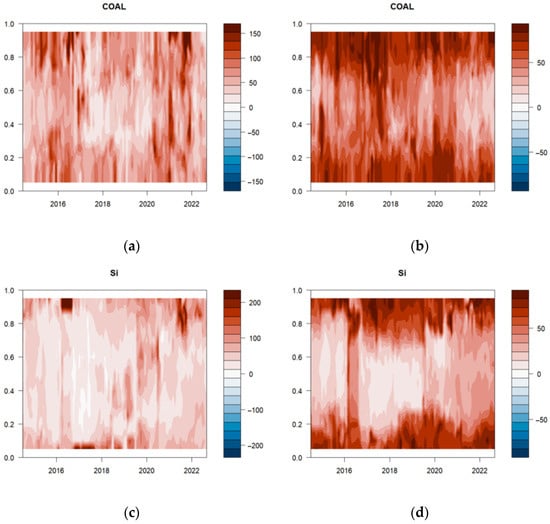

Figure 3 illustrates the temporal characteristics of the dynamic directional spillover levels of the two energy markets under financial market stress at all quantiles, respectively. Among them, the risk spillover (TO) indicates the level of risk spill from the energy market to financial market stress, and the risk spillover (FROM) indicates the level of risk spill from financial market stress to the energy market.

Figure 3.

Dynamic directional spillovers in the energy market under financial market stress: (a) Full quantile TO spillover estimation of the traditional energy market; (b) Full-quantile FROM spillover estimation of the traditional energy market; (c) Full quantile TO spillover estimation of the new energy market; (d) Full quantile FROM spillover estimation of the new energy market.

As can be seen from Figure 3, the all-encompassing dynamic directional spillovers (TO) and spill-ins (FROM) in the energy-financial system generally exhibited a “Shallow in the middle, deep at both ends” pattern in terms of color distribution. In this context, the energy market’s dynamic directional spillover (TO) effects were more extreme, with dark-colored blocks primarily concentrated in specific time periods under extreme market pressure conditions. On the other hand, the dynamic directional spill-in (FROM) effects were relatively smoother, with dark-colored blocks primarily concentrated in multiple time periods under extreme market pressure states. For the traditional energy market, the directional spillover (TO) was more stable, while the directional spillover (FROM) was more volatile. For the new energy market, the directional spillover (TO) was weak in the full quantile, while the directional spillover (FROM) showed a significant tail characteristic, which indicates that the new energy market is more sensitive to the shocks from extreme market conditions. Thus, it can be confirmed that there are volatility spillovers between the energy–financial system. Compared to the traditional energy market, the new energy market exhibits more significant tail risk spillover characteristics when facing risk shocks, further confirming that the new energy market is more sensitive to shocks under extreme market conditions. The reason may lie in the fact that, as an emerging market, the internal industrial structure and the connectivity between markets in the new energy sector are still in need of improvement. Under intermediate financial market stress conditions, the spillover linkage of the new energy market is weaker than that of the traditional energy market, displaying a seemingly stable market operation. However, under extreme financial market stress, the lack of risk resilience causes the new energy market to exhibit higher volatility and fragility, demonstrating greater instability [51].

Table 7 shows the volatility range of dynamic risk ‘TO’ and ‘FROM’ effects in the energy–financial system under different states. From Table 7, the dynamic risk transmission characteristics of the traditional energy market and the new energy market are as follows: Under extreme market stress conditions (), both the dynamic risk directional spillover (TO) effect and the dynamic risk directional spill-in (FROM) effect of the traditional energy market are stronger, while under extreme downward market stress conditions (), the risk volatility is relatively weaker, indicating that the risk spillover of the traditional energy market has right-tail spillover characteristics and asymmetry. The new energy market showed the strongest dynamic risk directional spillover (TO) effect under extreme upward market stress conditions (), while the dynamic risk directional spill-in (FROM) effect was strongest under extreme downward market stress conditions (). This indicates that the risk spillover of the new energy market also exhibits asymmetry under extreme market stress.

Table 7.

Volatility Range of Dynamic Risk ‘TO’ and ‘FROM’ Effects in the Energy-Financial System under Different Stress States.

At the same time, the energy market in the energy–financial system exhibits stronger dynamic risk directional spillover (TO) effects and tends to act as a net spillover source of dynamic risk within the system.

5.2.3. Dynamic Net Spillover Analysis of Each Quantile

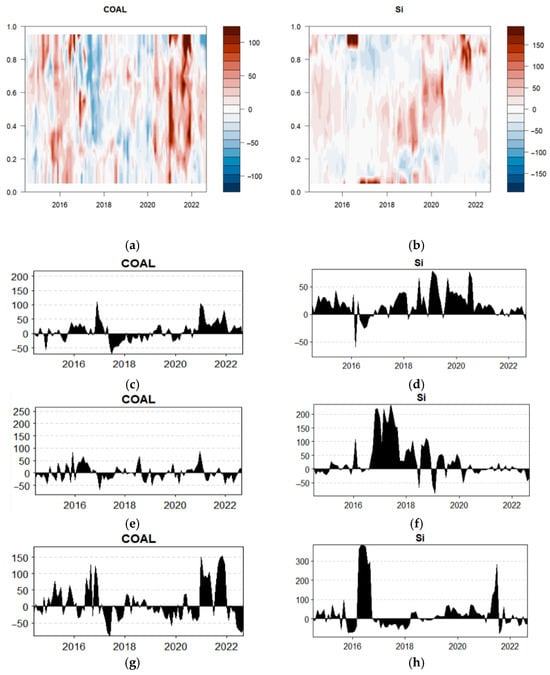

By examining the net risk spillover effects, we can determine the role of each energy market in the risk transmission pathway. This paper examined the dynamic volatility of net risk spillover effects from both a comprehensive and quantile-specific perspective. Figure 4 illustrates the dynamic effects of net risk spillover in the energy markets at different quantiles, where the red color in the full quantile chart represents net risk spillover effects, and the blue color represents net risk spill-in effects.

Figure 4.

Dynamic net spillovers in the energy market under financial market stress: (a) Full Quantiles of traditional energy market; (b) Full Quantiles of new energy market; (c) 0.5 Quantile of traditional energy market; (d) 0.5 Quantile of new energy market; (e) 0.05 Quantile of traditional energy market; (f) 0.05 Quantile of new energy market; (g) 0.95 Quantile of traditional energy market; (h) 0.95 Quantile of new energy market.

According to the color distribution in Figure 4, the full quantile chart is primarily dominated by warm tones represented by the red color, indicating that both the traditional energy market and the new energy market predominantly act as dynamic risk net spillover sources in the energy–financial system, which confirms the conclusions drawn from the directional spillover effect analysis.

Further analysis of the dynamic net risk spillover situation in the energy–financial system for the traditional energy market and the new energy market at the 0.5 quantile, 0.05 quantile, and 0.95 quantile. Table 8 shows the volatility range of dynamic net risk spillover effects in the energy–financial system under different states.

Table 8.

Volatility Range of Dynamic Net Risk Spillover Effects in the Energy–Financial System under Different Stress States.

By combining Figure 4 and Table 8, it can be observed that the new energy market acts as a net risk spillover source for most of the observed period, indicating that it is particularly sensitive to shocks and has a strong influence on other markets. From May to July 2016, China’s coal power and photovoltaic industries underwent a series of policy adjustments. The uncertainty surrounding these policy changes amplified volatility in the already unstable new energy market, triggering significant cross-market risk spillovers. During this period, the net spillover effect peaked, ranging from 385.02% to 416.16% under extreme upward financial market stress conditions (). This highlights how regulatory and policy uncertainty can act as a catalyst for systemic risk propagation in emerging markets. Over time, the traditional and new energy markets alternated between the roles of net spillover source and net spillover receiver. For instance, in June 2017, the U.S. announcement of its withdrawal from the Paris Agreement exerted differential pressures on China’s energy markets. Heightened volatility in the oil and gas industry, combined with shifts in investor sentiment, amplified cross-market spillovers [52]. During this period, the new energy market transitioned from being a net risk receiver to a net risk spillover source, with the net spillover effect reaching 236.96% at the 0.05 quantile. Meanwhile, the traditional energy market clearly assumed the role of a net risk receiver, with net risk spill-in peaking at −92.47% at the 0.95 quantile. This pattern illustrates how external geopolitical events, combined with market structure differences and investor behavior, can alter the direction and magnitude of risk transmission between energy sectors. Since the outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020, the traditional energy market has mainly acted as a net risk exporter, with peak net spillover levels reaching 181.10% during extreme upward market stress from October to November 2021. This suggests that during periods of global uncertainty, traditional energy markets—due to their size, financial integration, and central role in the energy system—become dominant channels for risk propagation.

In summary, the evidence indicates that policy changes, geopolitical shocks, and unpredictable “black swan” events are major drivers of cross-market risk contagion in China’s energy–financial system. The system responds most intensely under extreme upward financial market pressure, further confirming the right-tail spillover characteristics and asymmetry of risks. These results also emphasize that both structural features of the energy markets and behavioral responses of investors are crucial in understanding the dynamics of systemic risk transmission.

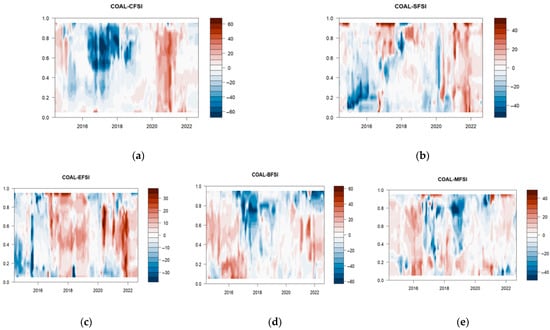

5.2.4. Binary Risk Spillover Effect Assessment

The binary risk spillover effect is a refined analytical approach designed to uncover the intrinsic mechanisms and dynamic relationships of risk transmission between different markets. By defining two distinct states—“spillover” and “no spillover”—this method systematically identifies the existence and direction of risk spillovers across markets, thereby quantifying the mutual influence of risks among them. Through the analysis of the dynamic net spillover between the two markets, we can better understand how the pressure of each financial sub-market is linked to the fluctuation of a particular domestic energy market, and speculate on its possible transmission path and influence mechanism. The net spillover effects of the traditional energy market and the new energy market in their energy–financial systems are shown Figure 5 and Figure 6, respectively.

Figure 5.

The dynamic net spillover of various financial market pressures on the traditional energy market: (a) The dynamic net spillover of traditional energy markets and credit markets; (b) The dynamic net spillover of traditional energy markets and stock markets; (c) The dynamic net spillover of traditional energy markets and exchange markets; (d) The dynamic net spillover of traditional energy markets and bond markets; (e) The dynamic net spillover of traditional energy markets and monetary markets.

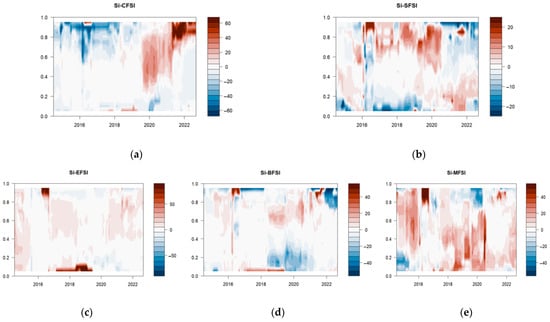

Figure 6.

The dynamic net spillover of various financial market pressures on the new energy market: (a) The dynamic net spillover of new energy markets and credit markets; (b) The dynamic net spillover of new energy markets and stock markets; (c) The dynamic net spillover of new energy markets and exchange markets; (d) The dynamic net spillover of new energy markets and bond markets; (e) The dynamic net spillover of new energy markets and monetary markets.

- Analysis of the dynamic net spillover effect of the pressure of the traditional energy market and various financial sub-markets.

Firstly, the contagion path of each financial sub-market toward the traditional energy market in different periods is analyzed according to Figure 5. Affected by the stress of the foreign exchange market (EFSI) and the stock market (SFSI), China’s traditional energy market acted as a net risk recipient in the extreme downward state of market stress around 2016. This may be attributed to the fourth stock market fluctuation in China’s A-share market. Around 2018, as the anti-globalization policy of the United States and the Sino-U.S. trade friction intensified, the traditional energy market turned to be a net risk recipient in the extreme upward state of market stress due to the stress strike of credit market (CFSI), bond market (BFSI), and money market (MFSI).

Secondly, we analyzed the dynamic net spillover effects of the traditional energy market during different periods and their transmission paths across various financial sub-markets. In 2016, the Chinese government implemented supply side structural reforms and cracked down on illegal mining, leading to a sharp decline in coal production capacity and a disruption of supply demand equilibrium. At the same time, some coal companies engaged in retaliatory price hikes, causing coal prices to rise rapidly. As a cornerstone of China’s economy, the substantial fluctuations in coal prices were transmitted throughout the economic system via the industrial chain. The market behavior during this period fully reflected the combined effects of supply side factors (capacity, utilization rate, and the development of new energy) and demand-side factors (economic growth and industrial demand), thereby validating the theoretical expectations of Hypotheses H1 and H2 regarding the impact of extreme supply and demand shocks on energy prices and their spillover effects in financial markets. Empirical results indicate that the core position of traditional energy markets in the economic system allows their price volatility to significantly propagate to financial sub-markets, thereby reinforcing the cross-market risk characteristics of supply and demand shocks.

Around 2018, under a macroeconomic backdrop of de-globalization, the implementation of the carbon emission trading system suppressed both the price and consumption of coal in China. Additionally, some coal enterprises faced liquidity crises due to credit downgrades, further releasing credit risk in the coal industry. Moreover, the depreciation of the RMB had a profound impact on the coal market’s supply demand fundamentals and energy imports and exports. Market volatility during this period primarily transmitted to the foreign exchange market. This episode validates Hypothesis H3, which posits that geopolitical factors can trigger continuous cross-market spillovers between energy and financial markets. Empirical evidence suggests that credit risk and exchange rate fluctuations become important channels for energy–financial system risk transmission under a geopolitical context.

At the end of 2020, under the influence of extreme cold weather associated with the “La Niña” phenomenon, coal prices experienced short-term surges and declines due to the resonance of multiple factors, including policy, market conditions, trade, and supply demand dynamics. Subsequently, the COVID-19 pandemic relieved overall industry supply and demand, leading to a sharp decline in coal prices. Under adverse price conditions, some highly indebted and low-profit coal enterprises lowered the overall credit level of the coal industry due to debt postponement or defaults. Consequently, the traditional energy market, through price and market fluctuations, gradually propagated risks to credit and equity sub-markets. This period validates Hypothesis H4, demonstrating that extreme environmental and climatic events generate tail-risk spillover effects, which are amplified through systemic financial markets, thereby intensifying the impact of energy price volatility.

- Analysis of the dynamic net spillover effect of the pressure of the new energy market and various financial sub-markets.

Compared to the traditional energy market, the net spillover between the new energy market and the financial market pressure is relatively weaker. This may be attributed to the fact that China’s new energy market is still in its early stages and has not yet established a mature transmission network with the financial market, which to some extent mitigates the large fluctuations in the new energy market caused by speculative activities using financial instruments. However, as shown in Figure 6, the new energy market has already begun to display its role in interactions with China’s financial markets. In the intermediate market pressure state, the new energy market mainly acts as a risk spillover source. In extreme market states, the new energy market may also adjust or shift in response to the heterogeneous shocks from financial sub-markets.

Under the extreme rise state of market pressure (), China’s new energy market has experienced two significant role shifts around 2016 and 2021. From April to September 2016, the new energy market exhibited notable risk spillover characteristics in its linkage with various financial sub-markets. During this period, global polysilicon demand increased, and fluctuations in imports, exports, and rising silicon prices affected China’s financial markets. This was driven by the gradual release of domestic wafer production capacity, alongside the implementation of “anti-dumping and anti-subsidy duties” and the suspension of “processing trade measures”. This episode illustrates the supply side transmission mechanism (H1), whereby external supply shocks and production adjustments led to quantile-dependent risk spillovers from the new energy market to the financial system. In the subsequent period, influenced by credit market stress (CFSI) and bond market stress (BFSI), the new energy market became a net risk taker. This reflects the demand-side and financial conditions transmission mechanism (H2), as higher borrowing costs and tighter credit conditions constrained market activity, showing how financial pressures can modulate risk spillovers and affect the market’s absorption of external shocks. At the beginning of 2021, the surge in polysilicon prices transformed the new energy market into a net risk spillover source. The implementation of the “dual carbon” strategy, coupled with the overseas energy crisis, domestic power rationing, and the ongoing transition from traditional to new energy, contributed to rapidly rising inflation expectations. Accelerating global monetary policy tightening affected the stock and bond markets, which in turn transmitted risks back to the new energy market. This period illustrates the compound effect of supply shocks, policy interventions, and geopolitical/environmental factors (H1, H3, H4) on market risk propagation, highlighting that extreme market conditions amplify tail-risk effects and generate feedback loops between energy and financial markets.

In the extreme decline state of market pressure , the new energy market primarily manifests as a net risk spillover. Around 2018, it exhibited significant spillover effects on all financial sub-markets except the stock market, which may be linked to the reduction of NEV purchase subsidies and rising global trade tensions. This episode reflects the demand-side transmission mechanism (H2), as policy changes reduced market incentives and suppressed domestic demand, generating asymmetric price fluctuations and risk propagation across financial sub-markets.

Specifically, the escalation of the Sino-U.S. trade dispute affected the stock market, creating additional cross-market linkages. This illustrates the geopolitical transmission mechanism (H3), demonstrating how external trade tensions can induce tail-risk spillovers in the energy-financial system.

Since then, with the rise of emerging economies such as China and shifts in domestic and U.S. economic policies, calls for oil de-dollarization and RMB internationalization have gradually increased. Central banks’ adjustments to monetary policy and interest rate fluctuations have shifted the primary source of risk spillovers to the bond market (BFSI). In the ongoing reform of the energy–financial landscape, the new energy market primarily spills over risk to the monetary market. This highlights the interaction of demand-side pressures, geopolitical shifts, and financial market conditions, showing that even under extreme declines, tail-risk propagation is sensitive to policy, macroeconomic, and regulatory changes, consistent with Hypotheses H2 and H3.

To sum up, China’s energy market shows the dual characteristics of industrial policy guidance and market demand-driven. The oscillation of the financial market mainly lies in the changes in market expectations caused by domestic and foreign market policies, the external environment, and the fluctuation of investor sentiment.

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

This paper selected China’s coal market price and domestic polysilicon price from September 2011 to September 2022 as the research sample and constructed a pressure index of China’s financial sub-markets. On this basis, this paper established two QVAR models and empirically studied the fluctuation spillover effect and tail characteristics between the pressure of each financial sub-market and China’s new and traditional energy markets. As the empirical results show:

- The Chinese energy–financial system exhibits significant risk spillover effects, with the energy market being the primary source of risk. It demonstrates a dual characteristic driven by both industrial policy guidance and market demand. Meanwhile, the capital market and the foreign exchange market are the main recipients of these risks.

- In the extreme market pressure states, the risk spillover effects and volatility of the energy–financial system are significantly higher than in intermediate states, showing notable tail spillover characteristics and asymmetry. Specifically, the traditional energy market is more sensitive to risk fluctuations under extreme upward market pressure, while the new energy market is more sensitive to risk fluctuations under extreme downward market pressure. This suggests that the instability of China’s energy and financial markets is primarily driven by the risk shocks in the extreme states of financial market pressure.

- By analyzing the formation causes and transmission paths of extreme risk spillover effects during specific time periods, it is found that the risk fluctuations in the energy market within the energy–financial system are mainly influenced by unstable factors such as supply–demand imbalances, geopolitical situations, and environmental and climate changes. Among these, the volatility of the traditional energy market is primarily driven by imbalances in the supply–demand fundamentals, while the volatility of the new energy market is mainly caused by a series of chain reactions triggered by energy policy adjustments. The volatility of financial markets is primarily driven by domestic and international market policies, external environments, and changes in market expectations caused by fluctuations in investor sentiment. Therefore, the hypotheses H1, H2, H3, and H4 proposed in this paper have been verified.

- Previous studies have analyzed directional spillover effects but have not systematically established the relationship among directional spillovers (To), spill-ins (From), and net spillovers (Net). This study found that under the same market conditions, markets exhibiting the largest directional spillover effects are often also the largest net risk spillover markets, whereas markets with the largest directional spill-in effects do not necessarily correspond to the largest net risk spill-in markets. Furthermore, both traditional and new energy markets exhibit significant tail-risk spillover characteristics, with dynamic directional spillover (TO) effects being more extreme and directional spill-in (FROM) effects relatively smoother. This provides a novel perspective on the asymmetric nature of risk transmission in extreme market conditions, contributing to the identification of systemic risk sources.

- Previous research has largely overlooked the risk spillover effects between the new energy market and financial markets. By introducing new energy market variables and conducting a heterogeneity analysis with the traditional energy market, this study shows that the new energy market is more sensitive to risk shocks, and the volatility of risk spillovers in the new energy–financial system is more pronounced. This indicates that, under extreme market conditions, the new energy market acts as a significant amplifier of systemic risk, offering important implications for policy-making and investment risk management.

Based on the conclusions above, the following policy recommendations are put forward in this paper:

- Stabilize the traditional energy market to ensure supply and price stability. To mitigate price fluctuations caused by supply demand imbalances, it is necessary to establish dynamic price adjustment mechanisms and strategic reserves, improve production–supply coordination, and enhance market transparency. Regulatory authorities can issue regular market supply demand reports, set price intervention thresholds, and guide enterprises to adjust production flexibly for precise regulation. These measures not only strengthen the risk resilience of the traditional energy sector and ensure energy security, but also contribute to the sustainable development of the energy–finance system by reducing systemic volatility and creating a stable foundation for investment and financial planning.

- Foster a resilient renewable energy market to promote long-term sustainable development. Given the sensitivity of the renewable energy market to downward shocks, it is important to build risk monitoring and early warning systems, support technological innovation and market-oriented applications, and accelerate the development of sustainable business models. Policymakers can establish dedicated R&D funds and encourage renewable energy enterprises to engage in green finance and carbon trading initiatives. By enhancing sector resilience through technological advancement and market mechanisms, systemic risks are mitigated, and the energy–finance system benefits from a more adaptive, long-term growth trajectory that aligns with sustainability goals.

- Strengthen financial regulation and cross-market risk management to prevent systemic crises. To prevent the transmission of energy market risks to the financial sector, it is essential to establish an integrated monitoring mechanism linking energy and financial markets, enhance supervision of capital, foreign exchange, and derivative markets, and improve emergency response systems. Regulators can conduct regular stress tests, define capital adequacy and liquidity requirements under extreme scenarios, and establish cross-departmental coordination mechanisms. Optimizing risk transmission channels helps mitigate tail risks and systemic crises, thereby ensuring the overall stability of the energy–finance system and supporting its sustainable development by safeguarding financial continuity and investor confidence over the long-term.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.D. and C.L.; formal analysis, S.D. and J.L.; funding acquisition, J.L.; methodology, N.L. and C.L.; software, N.L. and C.L.; supervision, S.D. and J.L.; visualization, N.L. and C.L.; writing—original draft, S.D., N.L., C.L. and J.L.; writing—review and editing, N.L. and C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors are grateful for the financial support provided by the Ministry of Education’s Humanities and Social Sciences Research Planning Fund Project (No.: 24YJA790041).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the raw data were sourced from the Wind database “https://www.wind.com.cn/mobile/EDB/zh.html (accessed on 20 June 2025)” and the Choice database “http://choice.eastmoney.com (accessed on 20 June 2025)”. If needed, the authors can provide the raw data for review to ensure the transparency and reliability of the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Shi, Y.R.; Zhao, Y.Q. The contribution of green finance to energy security in the construction of new energy system: Empirical research from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 429, 139480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.S.; Klein, T.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, P.Z.; Weber, O. Dynamic connectedness between crude oil futures and energy industrial bond credit spread: Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 2025, 143, 108294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Chen, L. Carbon financial trading risk based on multidimensional analysis of data flow from the perspective of low-carbon economy. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.Y.; Zhang, W.W.; Zhang, D. The time-varying impact of geopolitical risks on financial stress in China: A TVP-VAR analysis. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 69, 106134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, N. A statistical review of considerations on the implementation path of China’s “Double Carbon” goal. Sustainability 2022, 18, 11274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Rizwana, Y.; Padda, I.U.H.; Hassan, S.W.U.; Kamal, M.A. Inequalities by energy sources: An assessment of environmental quality. PLoS ONE 2020, 3, e0230503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.Q.; Bai, F.L.; Liu, X.L.; Liu, Z.W. A review on renewable energy transition under China’s carbon neutrality target. Sustainability 2022, 22, 15006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, T.; Greenwood Nimmo, M.; Shin, Y. Quantile connectedness: Modeling tail behavior in the topology of financial networks. Manag. Sci. 2022, 68, 3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illing, M.; Liu, Y. Measuring financial stress in a developed country: An application to Canada. J. Financ. Stab. 2006, 2, 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huotari, J. Measuring Financial Stress—A Country Specific Stress Index for Finland; Bank of Finland: Helsinki, Finland, 2015; Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Measuring-Financial-Stress-%E2%80%93-A-Country-Specific-for-Huotari/367f64ac59b18f6063db0fb6863f3900dbbc9a8b (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Kliesen, K.L.; Owyang, M.T.; Vermann, E.K. Disentangling diverse measures: A survey of financial stress indexes. Fed. Reserve Bank St. Louis Rev. 2012, 94, 369–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakkio, C.S.; Keeton, W.R. Financial stress: What is it, how can it be measured, and why does it matter? Econ. Rev. 2009, 94, 5–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lall, S.; Cardarelli, R.; Elekdag, S. Financial stress, downturns, and recoveries. IMF Work. Pap. 2013, 9, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestrini, A.; Zaghini, A. Financial shocks and the real economy in a nonlinear world: From theory to estimation. J. Policy Model. 2015, 6, 915–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Y.; Miao, Z.Q.; Zhang, T. Real-time monitoring of China’s financial stress: Evidence based on mixed frequency big data dynamic factor model. Econ. Stud. 2022, 4, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. Construction of systemic financial stress index based on three-pass regression filter model. Stat. Decis. 2022, 38, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.J. China’s systemic financial risk: Indexed measures and causal associations. Mod. Econ. Res. 2023, 4, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, S.B.; Li, Z.X. Dynamic spillover effects of global financial stress: Evidence from the quantile VAR network. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 90, 102945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.Y.; Mercado, R.V. Determinants of financial stress in emerging market economies. J. Bank. Financ. 2014, 45, 199–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolakis, G. Spreading crisis: Evidence of financial stress spillovers in the Asian financial markets. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2016, 54, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.F.; Liang, C.; Ma, F. Financial stress spillover network across Asian countries in the context of COVID-19. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2023, 7, 965–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolakis, G.; Papadopoulos, A.P. Financial stress spillovers across the banking, securities, and foreign exchange markets. J. Financ. Stab. 2015, 19, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]