Abstract

Urban areas globally face the critical challenge of meeting growing energy demands while maintaining environmental sustainability. However, existing research provides limited and often inconsistent evidence on how green finance affects urban energy efficiency, largely due to heterogeneous measurement systems, methodological constraints, and insufficient identification of underlying mechanisms. To address these research gaps, this study investigates two core questions: Does green finance significantly improve urban energy efficiency? If so, what are the specific transmission mechanisms driving this impact? Methodologically, this exploration employs a Double Machine Learning (DML) approach to analyze panel data from 210 Chinese cities between 2006 and 2022. The analysis demonstrates a significant and positive impact of green finance on urban energy efficiency, with an estimated coefficient of 0.1910. Further analysis identifies three constructive mechanisms, including environmental regulations, industrial structures, and green technological innovation, which enhance resource allocation and energy utilization efficiency. Moreover, green finance shows a stronger positive impact in non-resource-dependent cities, regions outside traditional industrial bases, and financially developed areas. These findings recommend establishing standardized green finance frameworks, increasing targeted financial support for key regions, and integrating green innovation with industrial restructuring. These measures help consolidate China’s green finance system and improve regional energy efficiency through market expansion, energy transition, and technological advancement.

1. Introduction

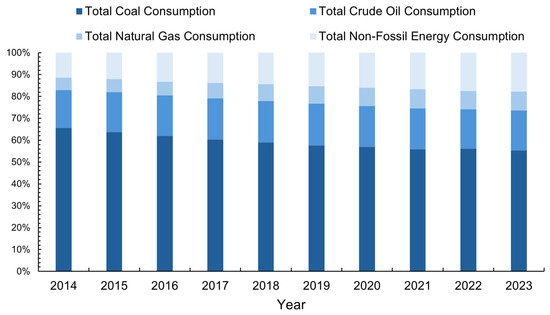

The transition to green energy has achieved significant progress globally; nonetheless, persistent energy shortages remain a critical challenge [1]. This dilemma compels economies to ensure energy security while expanding renewable energy. Despite the sustained priority of economic growth, the resource-intensive development paradigm has proven unsustainable due to its inherent characteristics, including pollution, excessive energy consumption, and high emissions [2]. Figure 1 illustrates the recent decadal evolution of primary energy consumption structure in China during 2014–2023. Regarding the figure, coal consumption comprises more than half of total energy use despite its gradually decreasing trend, which signifies a heavy reliance on fossil fuels. This coal-dominated mix not only accelerates environmental degradation but also strains governance systems. This issue is particularly crucial for China, as the second-largest economy in the world, undergoing urbanization and industrialization, necessitating optimization of its energy use to sustain economic growth while mitigating environmental impact. As a potential solution to the issue, energy efficiency is a key indicator equal to the proportion of economic output to energy consumption, which balances energy consumption and pollution reduction. Hence, enhancing energy efficiency can pave the way for reducing the consumption of energy resources and carbon emissions, leading to the sustainable development of the economy and environment.

Figure 1.

China’s primary energy consumption structure, 2014–2023. Source: China energy statistical yearbook.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) highlights the urgency of action in its 2023 Energy Efficiency Report. According to the report, doubling global energy efficiency by 2030 can reduce carbon dioxide emissions by over 7 billion tons, equivalent to the emissions of the global transportation sector. Achieving the emission reduction targets requires sustained efficiency improvements, especially due to the continuous increase in electricity consumption. In response, governments worldwide are adopting strategies, particularly involving green finance plans, to address efficiency barriers [3]. Green finance facilitates energy savings and emission reductions by funding the development and application of green technologies [4]. It balances production and consumption of energy, incentivizes businesses to optimize resource-intensive operations, and propels sectors toward sustainable, low-carbon models, ultimately boosting energy efficiency [5,6,7]. Recent empirical evidence further indicates that green finance accelerates energy transitions across diverse socioeconomic settings, showing distinct threshold and climate-risk moderation effects [8].

Extensive research has explored the spatial–temporal dynamics of green finance, energy systems, and energy efficiency, focusing on spatial spillover effects of development in the energy sector [9,10,11]. However, studies include inconsistent measurements for green finance, challenging the provision of comparative analyses with high precision. Some research examines the effects of specific green financial instruments, like green credit and bonds, on energy efficiency [12], while others use Difference-In-Differences (DID) models to assess policy impacts on green innovation, energy efficiency, or total factor productivity [13,14]. They assess the impact of green finance on energy efficiency to provide preliminary evidence of its key role in energy development [15,16,17], leading to the adoption of multidimensional frameworks incorporating policies, market dynamics, and technological innovation [9,16]. Furthermore, recent studies highlight that specific green finance instruments, particularly green bonds, significantly drive renewable energy growth [18], with the digital economy acting as a key moderator in low-carbon transformations [19]. Based on the findings of these studies, a growing consensus reveals that green finance boosts energy efficiency by fostering technological innovation and optimizing energy use [20,21,22]. Accordingly, green finance has been reinforced by adopting stricter environmental regulations and technological advancements in cities, which are economic hubs, major energy consumers, and main carbon emitters. Green finance also has significant indirect effects on urban total factor energy efficiency [23]. It accelerates efficiency gains by promoting renewable energy adoption and innovation [24]. However, its specific impact pathways on urban energy efficiency remain underexplored due to the complexity of accounting for diverse economic and social factors. In this regard, traditional econometric methods often face challenges such as omitted variable bias, model misspecification, multicollinearity, and high dimensionality, limiting the estimation accuracy. The reviewed literature highlights the following critical research gap: while the correlation between green finance and energy efficiency is acknowledged, the causal transmission mechanisms remain “black-boxed”, and traditional linear estimations fail to capture the complex, nonlinear dynamics inherent in this relationship. To address this issue, the double machine learning (DML) model offers a robust solution with a more reliable estimation approach [25,26,27].

To fill this gap, the primary objective of this study is to rigorously identify the causal impact of green finance on urban energy efficiency. Specifically, this research aims to achieve three sub-objectives: (1) to accurately estimate the net effect of green finance by eliminating potential biases from high-dimensional control variables; (2) to decode the “black box” of transmission mechanisms by verifying the mediating roles of environmental regulation, industrial upgrading, and technological innovation; and (3) to reveal the heterogeneous impacts across different resource endowments and industrial bases.

To achieve these objectives, this study uses a Double Machine Learning (DML) framework to analyze comprehensive panel data of Chinese cities. The innovation of this study lies in the development of two novel key methods to estimate the impacts of green finance. First, it applies a DML approach with nonlinear interaction terms and dynamic weight matrices specifically designed to capture the complex, non-uniform relationships between green finance and urban energy efficiency. This technique produces results with higher accuracy compared to the conventional econometric models. Second, the study develops an original three-dimensional heterogeneity analysis framework, considering regional development stages, industrial structures, and resource endowments simultaneously. This framework systematically reveals the spatially differentiated mechanisms underlying the green finance and energy efficiency nexus, providing a novel analytical approach to understanding context-specific impact pathways. In this way, this study contributes significantly to the literature by elucidating the intrinsic mechanisms through which green finance enhances urban energy efficiency. It establishes a comprehensive analytical framework demonstrating that green finance operates through three key pathways: technological innovation, environmental regulation, and industrial upgrading. These findings not only advance the theoretical understanding of finance–environment interactions but also provide policymakers with critical insights into designing differentiated green finance instruments. The identified mechanisms are particularly valuable for developing targeted policy packages that can be tailored to cities’ specific developmental stages and industrial characteristics for maximal improvement of energy efficiency.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the theoretical analysis and research hypotheses. Section 3 details the methodology and materials, including the DML model construction and variable selection. Section 4 provides the results and discussion, covering baseline regressions, robustness checks, mechanism analysis, and heterogeneity. Section 5 presents the conclusions, followed by policy recommendations in Section 6. Finally, Section 7 discusses the limitations and suggests directions for future research.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

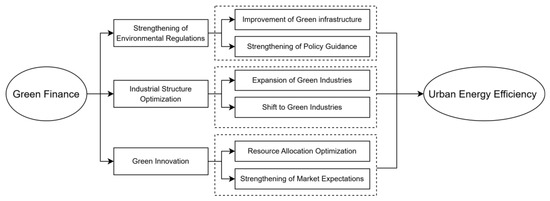

Figure 2 demonstrates the conceptual framework of the study. Addressing the identified research gap regarding the “black-boxed” transmission mechanisms, this section theoretically deduces the specific pathways through which green finance influences energy efficiency. As shown in the figure, energy efficiency is critical for sustainable development and environmental protection. The foundation of this pronounced relationship is the “big push” theory, which states that developing countries require substantial initial investments in clean energy technologies, research and development (R&D), and human resource training to enhance energy efficiency and drive sustainability [28]. Nevertheless, such investments frequently involve substantial expenses and unpredictable results, necessitating the adoption of fiscal policies, encompassing funding, incentives, and risk mitigation. Green finance supports environmentally friendly projects by channeling capital toward sustainability, fostering innovation, and promoting energy-saving technologies in different countries. In China, for example, it has significantly advanced green innovation and resource efficiency, advancing clean energy technology and increasing investments in emission reduction projects, thereby facilitating sustainable economic transitions and optimizing resource management [29]. Considering the potential for market failures in environmental investments, green finance leverages government intervention and incentives to ensure efficient capital allocation to projects that benefit both the environment and society. This promotes energy-efficient technological advancements and infrastructure development [30], accelerates R&D and the deployment of clean energy innovations, and optimizes energy use in economic ventures. Based on green finance’s pivotal role in enhancing energy efficiency and sustainability, this research introduces its first hypothesis.

Figure 2.

Mechanisms of green finance’s impact on urban energy efficiency. The dashed boxes indicate the specific sub-mechanisms for each pathway.

Hypothesis H1:

Green finance improves urban energy efficiency.

Furthermore, to explicitly address the research gap regarding the ‘black-boxed’ transmission pathways identified in the literature, this study explores how green finance influences urban energy efficiency. It outlines various mechanisms by which green finance influences urban energy efficiency, including the research hypotheses. As a unique environmental regulation tool, green finance steers capital allocation toward environmental protection, distinguishing itself from traditional command-and-control and market-based regulatory approaches [31]. Environmental investments often generate positive externalities, making them a cornerstone of effective regulation. However, converting these investments into immediate economic returns and addressing pollution spillover effects remains a challenge, necessitating strong government intervention to maximize societal welfare. Green finance leverages low-interest loans, green bonds, and similar instruments to encourage firms to adopt energy-efficient equipment, low-carbon technologies, and smart systems, promoting compliance with environmental standards. In this way, it improves overall environmental performance by supporting green infrastructure development, optimizing energy structures, reducing fossil fuel dependence, and enhancing energy system resilience [32]. In addition, government policies strengthen financial support for eco-friendly initiatives, expanding green finance markets and indirectly increasing firms’ environmental awareness and compliance. Strict regulations ensure funds align with environmental objectives, which enhances transparency and corporate performance. Furthermore, incentives and subsidies may induce a “crowding-in effect”, thereby drawing increased investment into environmental capital. This influx catalyzes production shifts, reinforces green finance governance, and ultimately improves energy structures and efficiency. Drawing on this analysis, the second research hypothesis is formulated.

Hypothesis H2a:

Environmental regulation has a mediating role in the impact of green finance on urban energy efficiency.

Green finance can improve the industrial structure by balancing environmental risks and economic returns, which maximizes dual benefits. As a strategic macroeconomic tool, it optimally allocates financial resources to transition industries from high-energy, high-pollution models to low-energy, low-pollution frameworks while expanding investments in green sectors [33]. First, through green credit, bonds, and funds, green finance supports clean energy, environmental protection, and green agriculture, alleviating constraints of early-stage finance and fostering innovation and growth in green industries. It also strengthens green supply chains—from raw materials to production and consumption—enhancing the competitiveness in the green economy. Second, by setting environmental standards and financing thresholds, green finance channels capital into emerging energy-saving industries [34]. In this way, it motivates high-pollution, high-energy sectors to upgrade technologies, reduce emissions, improve efficiency, and transition toward high-value, low-energy structures. This structural change further facilitates green upgrades in traditional industries, promoting resource recycling and pollution control. For example, it enables manufacturing sectors to adopt green technologies and clean energy, fostering waste reuse and efficient energy cycles. This analysis proposes the following research hypothesis.

Hypothesis H2b:

Optimization of industrial structures has a mediating role in the impact of green finance on urban energy efficiency.

Green finance can ensure the efficient allocation of resources to industries by directing capital toward green innovation, improving financing conditions, and lowering costs, which drive energy efficiency and low-carbon growth. Polluting industries face higher financing barriers and costs, compelling them to prioritize green innovation for a sustainable transition [35]. Green finance accelerates market-based emission trading, enhancing resource allocation efficiency. For instance, eco-friendly firms with lower emissions can trade surplus quotas for economic gains, promoting technology-driven innovation, energy efficiency, and investments in emission reduction [36]. Additionally, through policy support and funding, green finance mitigates the long cycles and high costs of innovation projects, bolstering investor confidence and market predictability regarding risks and returns. As green finance markets expand, firms and investors increasingly recognize the potential of green technologies, spurring investment in innovation projects, enhancing energy efficiency, and creating a virtuous cycle. Based on this analysis, the following hypothesis is formulated.

Hypothesis H2c:

Green innovation has a mediating role in the impact of green finance on urban energy efficiency.

3. Methodology and Materials

This section systematically presents the research methodology and data materials employed in this study. It is organized into three subsections: Section 3.1 elaborates on model construction, specifically the rationale and specification of the Double Machine Learning (DML) framework; Section 3.2 presents variable setting, including the dependent, independent, and mechanism variables; and Section 3.3 describes the data sources and provides descriptive statistics.

3.1. Model Construction

3.1.1. Rationale for Method Selection

To rigorously investigate the impact of green finance on urban energy efficiency, this study adopts the Double Machine Learning (DML) framework. This approach offers significant advantages over conventional causal inference models, particularly in terms of variable selection and estimation accuracy [37]. Urban energy efficiency is a complex system influenced by a wide range of socioeconomic factors. DML is uniquely suited to this high-dimensional context, providing a more accurate assessment than traditional alternatives.

First, DML overcomes the structural limitations of traditional econometric models. Conventional methods rely on pre-specified control variables, which expose research to omitted variable bias due to theoretical gaps or data unavailability. Furthermore, in high-dimensional settings, these models suffer from the “curse of dimensionality” and are highly sensitive to multicollinearity, which can distort coefficient estimates. In contrast, DML utilizes machine learning and regularization techniques to autonomously select optimal subsets of control variables from high-dimensional datasets. This capability effectively mitigates the adverse effects of multicollinearity and excessive controls, thereby minimizing estimation bias and enhancing model reliability.

Second, DML fundamentally distinguishes itself from standard machine learning algorithms (e.g., Random Forests, Support Vector Machines, Gradient Boosting) by prioritizing causal inference over pure prediction. While standard ML algorithms excel at predictive accuracy, they generally fail to yield valid causal interpretations. DML addresses this issue by combining orthogonalization with cross-fitting. This mechanism effectively removes the influence of high-dimensional nuisance parameters on the target parameter, preventing overfitting and ensuring consistent, asymptotically normal estimates of the treatment effect.

Finally, DML is superior in handling complex, nonlinear relationships. Traditional linear regressions often fail to capture the dynamic interactions between green finance and energy efficiency, leading to model misspecification. Unlike generic ML models that capture nonlinearity but lack causal validity, DML integrates the flexible modeling capabilities of algorithms (such as Random Forests) into a rigorous econometric identification strategy. This integration allows the model to effectively consider nonlinearities and complex variable dependencies without sacrificing the unbiasedness required for robust causal analysis.

3.1.2. Model Specification

Drawing on prior studies [38], Equation (1) represents a DML model used in the research.

where is the treatment variable coefficient; represents urban energy efficiency; indicates green finance development as the treatment variable; is a K-dimensional vector of control variables; i shows cities; t denotes years; captures the direct and potential nonlinear effects of the high-dimensional on ; and and are error terms with white noise characteristics, i.e., . Equation (2) is the auxiliary equation, where affects the treatment variable via and the outcome variable via .

3.1.3. Estimation Procedure

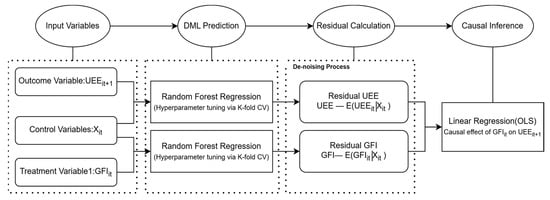

In essence, as illustrated in Figure 3, this procedure serves as a ‘denoising’ process, where machine learning algorithms first remove the confounding effects of control variables, allowing the subsequent linear regression to capture the pure causal effect of green finance on energy efficiency.

Figure 3.

Estimation framework of double machine learning. The dashed boxes illustrate the main stages of the DML procedure, including variable input, machine learning–based prediction, residual (de-noising) calculation, and causal inference.

The estimation process begins with obtaining an unbiased estimate of , by transforming Equation (1). Taking conditional expectations with respect to on both sides of Equation (1) and subtracting them from Equation (1) yields the following: . This equation requires estimates of and for Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression. We use machine learning to estimate and , denoted as and , respectively. If , Equation (3) represents the unbiased estimator of .

3.1.4. Algorithm Implementation

The present research applies a partially linear double machine learning (DML) approach to investigate the relationship between green finance and urban energy efficiency. The model uses a 1:4 sample split, applying random forests for prediction and estimation in both the main regression and the auxiliary regression.

The choice of random forests as the base learner is motivated by both the nature of the research question and the structure of the dataset. Random forests are well suited for high-dimensional economic data that may contain nonlinear interactions and complex variable dependencies, which are common in studies of urban energy efficiency. Compared with alternative learners such as LASSO or gradient boosting, random forests provide strong predictive performance without strong parametric assumptions, and they are relatively robust to multicollinearity and outliers. This makes them particularly appropriate for the DML framework, where the accuracy of nuisance parameter estimation directly affects the consistency of the treatment effect estimator. To minimize the potential bias from parameter dependence, we employed K-fold cross-validation to adaptively select optimal hyperparameters (e.g., tree depth) for the random forest algorithm, ensuring the robustness of our estimation results.

3.2. Variable Setting

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

This research employs green total factor urban energy efficiency (UEE) as a key indicator for measuring energy efficiency. Following Liu et al. [39], it incorporates labor, capital, and energy as primary input variables, while regional GDP serves as the intended output. Additionally, undesirable byproducts include industrial sulfur dioxide, industrial dust, and industrial wastewater. To assess urban energy efficiency comprehensively, this study adopts the SBM-ML index approach, which effectively accounts for both desirable outputs and undesirable environmental externalities.

3.2.2. Core Explanatory Variable

The Green Finance Development Index (GFI) serves as a key indicator for assessing green finance. Based on Liu and He [40], a holistic evaluation of green finance is performed through an analysis of its key components—green credit, green investment, green insurance, green bonds, green support, green funds, and green equity. This index thoroughly analyzes subdomains to reflect the development level and overall effectiveness of the green finance system.

3.2.3. Mechanism Variables

The mechanism analysis involves three pathways through which green finance affects urban energy efficiency: green innovation, industrial structure, and environmental regulation. To analyze the mechanisms, traditional methods often apply log transformations to patent application counts, which can distort data and reduce model interpretability. Following Yang et al. [35], green innovation (GI) is proxied by the unadjusted count of green invention patent applications. Using this proxy allows this study to offer a broad comparability analysis. Industrial structure upgrading (ISU) is assessed using the ratio of tertiary industry output to secondary industry output, following Gan et al. [33] and Zhang and Li [41]. To capture the intensity of environmental regulation (ER), this study employs the comprehensive utilization rate of general industrial solid waste as an indicator, based on Li et al. [42] and Xiao and Li [43]. The ER proxy is selected because it directly measures the stringency of environmental regulations enforcing industrial waste management, a critical policy lever in Chinese cities with manufacturing clusters. Moreover, we address potential endogeneity and multicollinearity with ISU through Double Machine Learning and robustness checks, while noting its limited applicability to service-dominated urban economies.

3.2.4. Control Variables

DML effectively handles high-dimensional control variables. To ensure empirical accuracy, it follows Feng et al. [28], Zhang and Li [41], and Lu and Li [36] to define the subsequent dimensional classification.

The first one is Economic and Industrial Structure Dimension which encompasses five key indicators: Financial Development Level (FDL), measured as total year-end deposits and loans from financial institutions in proportion to GDP; Industrial Development Level (IDL), represented by the industrial sector’s value-added share of GDP; Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), expressed as the proportion of actual foreign investment to GDP; Marketization Level (MAR), assessed by general budget expenditure as a percentage of GDP; and Fixed Asset Investment (FAI), defined as the ratio of fixed asset investment to GDP.

The second one is Population and Social Policy Dimension, which includes six key indicators. Population scale (PS) is measured as the year-end registered population in natural logarithm; the natural population growth rate (NPG) represents the rate of population increase to the total population; human capital level (HCL) is the proportion of college students within the total population; employment structure (ES) reflects the percentage of the workforce engaged in the tertiary sector; and urbanization level (UL) is quantified by population density (in people per square kilometer).

The third one is Technology and Infrastructure Dimension which involves environmental infrastructure level (EIL), proxied by green coverage rate; transportation infrastructure level (TIL), measured by per capita road freight volume (in tons); public service level (PSL), indicated by per capita road area (in square meters); science and technology expenditure (STE) as the proportion of science spending in the government budget; education expenditure level (ELE), measured by education spending as a share of the fiscal budget; and informatization level (ITL), measured by total telecommunications business volume (in billions of yuan).

3.3. Data Sources

This study analyzes data from 210 prefecture-level cities between 2006 and 2022. Energy consumption data are sourced from the China Energy Statistical Yearbook, while the green finance development index is primarily derived from the China Financial Yearbook and China Science and Technology Statistical Yearbook. City-level control variables are obtained from the China City Statistical Yearbook, and green invention patent data come from the National Intellectual Property Administration. Missing data are addressed through direct substitution using corresponding city-level statistics and linear interpolation. Table 1 provides a comprehensive statistical summary of key variables. According to the table, some variables like UL show a high standard deviation, which highlights their potential sensitivity to outliers and necessitates conducting additional robustness examinations, like the winsorization test.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of related variables.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Variable Stationarity and Validity Checks

To verify the existence of long-term equilibrium relationships and reduce the likelihood of spurious regression, we initially applied the Levin–Lin–Chu (LLC) and Im-Pesaran-Shin (IPS) panel unit root tests to examine whether all variables were stationary (see Table S1 for details). The results of the LLC test indicate that UEE, FAI, PS, HCL, and PSL have unit roots, classified as I(1), while the remaining variables are stationary at level, categorized as I(0). In addition, the results of IPS test reveal that GFI, IDL, MAR, NPG, UL, EIL, TIL, ELE, and ITL are I(0), and the other variables are I(1). The unit root test results show that the dependent variable UEE is I(1), while the key control variable GFI is I(0), failing to meet the classical cointegration requirement of homogeneous integration order. Consequently, we conducted a Kao panel cointegration test exclusively on the I(1) variables (UEE, FDL, FDI, FAI, PS, HCL, ES, PSL, STE, ER, ISU, and GI) to verify their long-term equilibrium relationship. Table 2 represents the results of the Kao panel cointegration tests. Based on the table, four out of five statistics are significant at 1% level, confirming a cointegrating relationship and a stationary linear combination among the variables. The Augmented Dickey–Fuller t statistic fails to reject the null hypothesis, potentially due to limited degrees of freedom caused by the large number of variables. The resulting cointegration relationship allows us to proceed with a Double Machine Learning (DML) regression analysis, without worrying about spurious regression estimation.

Table 2.

Panel cointegration test.

4.2. Baseline Estimates of Green Finance Impact

Table 3 provides a summary of the estimation results from the baseline regression model. Based on the table, the results remain consistent across the specifications. The specification in Column (1) contains green finance and the control variables; Column (2) extends the model by adding city fixed effects; and Column (3) further includes time fixed effects to address temporal heterogeneity; and Column (4) includes both. The green finance index (GFI) exhibits consistently positive and statistically significant coefficients, confirming a strong positive relationship between green finance and urban energy efficiency. These findings support Hypothesis H1, aligning with the ‘big push’ theory, which emphasizes large-scale investments for sustainable transitions. They affirm green finance’s role in driving green innovation and resource efficiency in China.

Table 3.

Baseline estimates of the impact of green finance on urban energy efficiency.

Overall, these findings align with existing evidence that green finance enhances energy efficiency across different socioeconomic settings [9,12]. Compared with prior studies using linear fixed-effects or spatial models, the magnitude of our estimates is more conservative. This is likely due to the DML framework, which flexibly absorbs high-dimensional confounders and avoids functional form biases commonly present in traditional econometric approaches. Recent studies similarly note that policy effects may be overstated when nonlinearities and endogenous targeting are not properly addressed [18,24]. Thus, our results provide a more robust benchmark for assessing the true contribution of green finance and help refine the empirical understanding of its effectiveness.

4.3. Robustness Tests

4.3.1. Excluding Large City Samples

Municipalities and provincial capitals, with their higher administrative status, stricter environmental regulations, and greater financial resources, may introduce bias in estimating green finance’s impact on energy efficiency. To address this issue, this research re-estimates the model excluding these cities. Table 4 presents the findings from the robustness analyses. In Column 1, the estimate for GFI is 0.1846, demonstrating statistical significance at the 1% level, confirming that green finance continues to enhance urban energy efficiency even without major metropolitan areas. This result reinforces the reliability and consistency of the findings.

Table 4.

Robustness checks: alternative samples and instrumental variables.

4.3.2. Winsorization Test

To address potential outliers, we re-estimate the baseline model by applying two-sided tail trimming at 1% and 5% thresholds for control variables. The results from Columns 2 and 3 in Table 4 demonstrate that the GFI coefficient retains its direction, statistical significance, and magnitude, thereby affirming the robustness of the findings.

4.3.3. Instrumental Variable Approach

Green finance may be endogenous to urban energy efficiency due to reverse causality or omitted variable bias. To tackle this issue, we utilize an instrumental variable (IV) approach, using the one-period lagged green finance development index (LGF) as the IV, following prior studies [5,7]. The GFI shows a strong temporal autocorrelation, as past green finance policies and outcomes influence the present corresponding values. Moreover, urban energy efficiency does not directly impact lagged green finance, mitigating endogeneity concerns. To assess the suitability of the chosen instrumental variables, this study implemented multiple identification evaluations. Firstly, in the initial stage of regression, the LGF exerts a substantial influence on energy efficiency. The F statistic in this stage is 271.84, thus alleviating concerns about the weakness of the instrumental variables. Secondly, under the setting of multiple instrumental variables, the green finance pilot zone dummy was introduced as an auxiliary instrumental variable. The Hansen J test was also implemented. Its p-value was 0.97, which did not reject the null hypothesis and supported the exogenous hypothesis of the overall instrumental variable. Similarly, according to Column (4), the coefficient of GFI is statistically significant, affirming the robustness of our findings.

4.3.4. Excluding Interference from Concurrent Energy-Saving Policies

An accurate assessment of green finance’s impact on energy efficiency needs to consider the effects of concurrent energy policies on energy structure and transitions. To isolate green finance’s net effect, we exclude samples influenced by such policies, including major coal-consuming provinces, renewable energy-rich western regions, pilot cities for energy-saving and new energy vehicles, and national fiscal policy demonstration cities for energy conservation. This approach minimizes interference from other energy-saving policies. Column (5) represents the results of estimating the model excluding these samples. According to the results, the coefficients of the GFI continue to be significant at the 1% level, supporting the robustness of the results and reinforcing the strong link between green finance and urban energy efficiency.

4.3.5. Algorithmic Robustness

To ensure robustness, we conduct multiple sensitivity tests on the DML model. First, we alter the sample division, changing the ratio from 1:4 to 1:2 and 1:6 to test robustness. Second, we introduce alternative prediction algorithms—neural networks, gradient boosting, and Lasso. The results of the sensitivity analyses are summarized in Table 5. Based on the results, the coefficients show insubstantial variation compared to the core findings, supporting the stability of the findings in terms of the observed positive association between green finance and urban energy efficiency.

Table 5.

Sensitivity analysis using alternative algorithms.

4.4. Transmission Channels: Regulation, Industry, and Innovation

The aforementioned findings confirm that green finance significantly improves urban energy efficiency, which can involve specific mechanisms. In this regard, this study examines the intermediary influences of environmental regulation, industrial structure optimization, and green innovation. Following Farbmacher et al. [44], it employs a DML framework, integrating random forests to analyze causal mediation effects. Table 6 reports the outcomes of the mediation effect estimations. Regarding the estimates, all mediation pathways show positive effects, statistically significant at the 1% level, thereby confirming that green finance bolsters urban energy efficiency.

Table 6.

Mechanism analysis: the mediating roles of regulation, industry, and innovation.

4.4.1. Environmental Regulation

Theoretical analysis suggests that green finance enhances urban energy efficiency by strengthening environmental regulation. To test this mechanism, we first examine green finance’s impact on environmental regulation (ER) and then its effect on urban energy efficiency (UEE). Table 6 provides the results of examining the mechanism effects of environmental regulation. Based on Columns (1) and (2), both green finance and ER exhibit positive coefficients that are statistically significant, confirming the constructive mediating role of environmental regulations regarding the association between green finance and energy efficiency. This result is consistent with Hypothesis H2a. Specifically, green finance drives stricter emission standards and regulatory oversight for high-pollution firms while supporting green infrastructure and pollution control projects. By directing capital toward green industries, it optimizes urban energy structures and accelerates the transition to sustainable production, ultimately enhancing energy efficiency.

4.4.2. Industrial Structure Optimization

Following the same approach, we examine the mediating role of industrial structure advancement (ISU). According to Table 6, columns (3) and (4), green finance has a positive and significant effect on ISU. Likewise, the effect of ISU on urban energy efficiency is positive and significant at the 1% level, confirming its role as a mediating variable. This result suggests that green finance, by integrating government guidance with market mechanisms, flows capital into energy-efficient, low-carbon, and eco-friendly industries. This flow accelerates the transformation of traditional sectors, strengthens the scale and competitiveness of green industries, and optimizes resource allocation. By reducing reliance on high-energy industries, green finance improves industrial energy efficiency, facilitating a green economic transition and sustainability. These findings validate Hypothesis H2b.

4.4.3. Green Innovation

Applying the same method, we test the causal mediation effect of green innovation (GI). Table 6, particularly columns (5) and (6), demonstrates that the coefficients associated with green finance and GI are positive and statistically significant at the 1% level, confirming that green finance enhances urban energy efficiency by incentivizing green innovation. Specifically, green finance facilitates funding for green technology R&D, enabling firms to achieve breakthroughs in clean energy and emission reduction technologies. In addition, it mitigates innovation risks, enhances firms’ motivation for technological advancements, and improves production energy efficiency while supporting industrial green transitions. These mechanisms collectively drive sustained improvements in urban energy efficiency, validating Hypothesis H2c.

The mechanism findings complement and extend existing research that typically evaluates single channels—such as innovation or industrial upgrading—in isolation. By using a DML-based mediation framework, this study uncovers three simultaneous and mutually reinforcing pathways. Interestingly, the dominant role of environmental regulation contrasts with evidence from Europe and other emerging economies, where innovation effects tend to prevail [18]. This divergence reflects China’s regulatory-centered green finance system, which generates strong compliance incentives. These results emphasize that institutional context shapes how green finance operates, offering a more integrated explanation of the finance–energy efficiency nexus than previously available.

4.5. Heterogeneity Analysis Based on Resource and Industrial Contexts

4.5.1. Resource Endowment Heterogeneity

As a crucial strategic asset, energy efficiency is significantly influenced by resource endowments, particularly in resource-based cities. In line with the National Sustainable Development Plan for Resource-Based Cities (2013–2020), this research distinguishes between resource-dependent and non-resource-dependent cities in the sample to analyze the heterogeneity of impacts of green finance. Table 7 provides a summary of the heterogeneity analysis, highlighting variations in the estimated effects across different subsamples. Based on Columns (1) and (2), the coefficients of GFI equal 0.0966 and 0.2191 in resource-based and non-resource-based cities, respectively, indicating a positive effect that remains statistically significant at the 1% confidence level. This result implies that GFI enhances energy efficiency across both city types. Comparatively, this effect is more pronounced in non-resource-based cities. Such variation can be explained by the structural nature of resource-oriented urban economies, whose growth models are predominantly shaped by resource exploitation and energy-intensive industrial activities. In these cities, green finance primarily facilitates transitions to low-carbon and energy-efficient models, yet the process involves industrial restructuring, technological innovation, and resource reallocation—factors associated with higher financial and technical risks. Consequently, while green finance fosters energy efficiency improvements, its impact is relatively weaker compared to non-resource-based cities, where economic structures are more diversified and adaptive to green financial mechanisms. Unlike resource-dependent cities, those with diversified economies provide a more conducive environment for green finance to flourish. Financial investment functions as a critical impetus for the development of green technologies and industries, advancing the transition toward energy-efficient and low-carbon solutions and ultimately enhancing comprehensive energy performance. Additionally, the position of these cities has more potential for leveraging policy guidance and market mechanisms to drive green finance innovation, further strengthening their energy efficiency gains.

Table 7.

Heterogeneity analysis across resource endowments and industrial bases.

The heterogeneity results further reveal that the effectiveness of green finance varies substantially across urban contexts. While prior research suggests that financial development enhances the environmental impact of green finance [19], few studies assess the combined roles of resource dependence and industrial legacy. Our findings show markedly weaker effects in resource-based and old industrial-based cities, where structural inertia and path dependence constrain the transition toward energy-efficient development. This result contrasts with the more uniform gains observed in OECD urban studies [3]. These patterns highlight that green finance is context-dependent rather than universally effective, contributing new comparative insights into urban energy transition dynamics.

4.5.2. Industrial Base Heterogeneity

The National Plan for the Adjustment and Transformation of Old Industrial Bases (2013–2022) highlights that old industrial base cities, as key national energy hubs, face significant challenges. These issues are rooted in high energy consumption and pollution, severely constraining energy efficiency improvements. The study examines industrial base heterogeneity by distinguishing cities according to the maturity of their industrial development—identifying old industrial bases and non-old bases. The regression estimates shown in Table 7, Columns (3) and (4), indicate that the coefficients corresponding to GFI are 0.1316 and 0.1858, respectively, for old and non-old industrial base cities, with both coefficients exhibiting strong statistical significance at the 1% criterion. This result shows that green finance enhances energy efficiency in both groups, with a more pronounced impact in non-old industrial base cities. This disparity arises from the long-standing reliance of old industrial base cities on outdated technologies and high-energy industries, where entrenched industrial structures and path dependence create barriers to transformation. In these cities, green finance-driven energy-saving innovations often require extended R&D and adoption periods, leading to delayed and less pronounced efficiency gains in the short term. The cities classified as non-old industrial bases display a more dynamic industrial structure, accelerated technological upgrading, and reduced expenditure in the course of economic transition. These advantages boost the beneficial impacts of green finance on energy-saving technology adoption and structural optimization, ultimately accelerating the improvement of energy efficiency.

4.5.3. Financial Development Heterogeneity

The varying stages of financial system development substantially shape the capacity of green finance to deliver effective environmental and economic outcomes. Regions with high financial development provide firms with easier access to financing to allocate resources toward energy efficiency improvements. Conversely, in less financially developed regions, funding constraints hinder investments in green technologies and efficiency-enhancing measures. To assess this heterogeneity, this study employs the criterion of financial deepening, defined by the mean share of bank deposits and lending over GDP, to distinguish cities with high financial development from those with lower levels. The regression estimates in Columns (5) and (6) of Table 7 indicate that green finance has coefficients of 0.2887 and 0.1230 in high- and low-financial-development areas, respectively, with both effects remaining highly significant at the 1% threshold. The findings reveal that green finance exerts a more pronounced influence on energy efficiency in regions exhibiting greater levels of financial development. This implies that a well-developed financial system provides firms with greater access to capital and a more conducive market environment, thus enhancing the beneficial influence of green finance on urban energy efficiency.

5. Conclusions

In the pursuit of high-quality development and carbon neutrality, improving urban energy efficiency is a critical challenge for China. To this end, green finance has emerged as a key policy tool that optimizes resource allocation. To rigorously evaluate its effectiveness and underlying mechanisms, this study employs a Double Machine Learning (DML) framework using panel data from 210 Chinese cities. The key conclusions drawn from the empirical analysis are as follows:

First, green finance significantly boosts urban energy efficiency. This improvement is realized through three distinct mechanisms: (1) strengthening environmental regulation, which promotes green infrastructure and energy-saving technologies while discouraging energy-intensive firms; (2) optimizing industrial structures, which shifts high-energy sectors toward low-carbon models and supports green industry clusters; and (3) incentivizing green innovation, which improves resource allocation and market expectations, thereby encouraging corporate R&D in green technologies.

Second, the impact of green finance exhibits significant regional heterogeneity. The positive effects are more pronounced in non-resource-based cities, regions outside traditional industrial bases, and financially developed areas. These variations are attributed to mature market mechanisms, advanced technology adoption capabilities, and greater industrial adaptability in these regions.

Beyond these empirical findings, this study also provides theoretical insights. The application of a Double Machine Learning framework underscores the importance of nonlinear and high-dimensional interactions in understanding how green finance affects urban energy efficiency. This extends existing theories that predominantly assume linear and homogeneous policy effects. In addition, the differentiated impacts observed across city types enrich the literature on urban energy efficiency by demonstrating that structural and institutional conditions fundamentally shape the effectiveness of green financial policies. These contributions help advance a more context-sensitive theoretical understanding of green finance in the urban development domain.

6. Policy Recommendations

Based on the empirical findings, this study proposes the following policy recommendations to enhance the effectiveness of green finance:

First, governments should establish a unified system for green finance standards. Inconsistencies in current standards can hinder funding for low-carbon projects. Therefore, developing a comprehensive certification and regulatory framework for green bonds, loans, and insurance is essential to enhance transparency and investor confidence. Strict entry and exit rules should be enforced to ensure funds effectively support energy conservation and green innovation while restricting financing for high-pollution industries.

Second, policymakers should implement targeted financial support strategies for key regions. Resource-based cities and old industrial bases face specific barriers to energy transition. Special funds and low-interest loans should be directed toward these areas to facilitate green technology upgrades, low-carbon projects, and sector-specific initiatives such as green mining. Effective use of these funds requires active collaboration between financial institutions and local governments, which drives regional low-carbon transitions.

Third, decision-makers should align green innovation initiatives with industrial transformation goals. Joint government-financial innovation funds should prioritize R&D in energy-saving technologies and clean energy, directing capital toward green credit and bonds. Furthermore, supporting small and medium-sized cities in sectors like green buildings can foster green industry clusters and establish an innovation-driven model, thereby enhancing energy efficiency on a national scale.

7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

While this research deepens insights into the function of green finance in promoting urban energy efficiency, three specific limitations highlight key avenues for future research.

First, regarding generalizability and context, this study relies on Chinese data, and the specific institutional environment may limit the direct transferability of findings to market-based systems. Future research should adopt a comparative perspective, replicating this analysis in other transition economies (e.g., BRICS) to test external validity. Additionally, applying Qualitative Comparative Analysis or Synthetic Control Methods could help disentangle how regional variations in development stages affect the optimal alignment of policy mixes.

Second, the depth of mechanism analysis can be expanded. The current study focuses on macro-level data and traditional financial instruments, leaving the synergy with digital technology and micro-foundations underexplored. Future studies should employ Spatial Durbin Models to test the interaction effects between digitalization and green finance. Furthermore, complementing quantitative analysis with qualitative methods, such as semi-structured interviews with financial practitioners and urban decision-makers, would be valuable for validating the specific implementation mechanisms proposed in this paper.

Third, measurement and estimation techniques can be further refined. The use of static patent counts may overlook the quality and time-lagged effects of innovation. Future research should adopt dynamic panel data models and use patent citation metrics to capture long-run impacts. Moreover, incorporating advanced estimators like Causal Forests could improve the identification of heterogeneous treatment effects, providing deeper insights into the causal dynamics of green finance.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172411016/s1, Table S1. Panel unit root tests for variables.

Author Contributions

Y.K.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—Original draft preparation. P.Y.: Data curation, Software, Validation, Writing—Reviewing and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hosseini, S.E. An outlook on the global development of renewable and sustainable energy at the time of COVID-19. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 68, 101633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, R. Green finance policy innovation and energy consumption carbon intensity: Resource allocation effect or green innovation effect. Gansu Soc. Sci. 2023, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Quevedo, J.; Jové-Llopis, E. Environmental policies and energy efficiency investments. An industry-level analysis. Energy Policy 2021, 156, 112461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Wang, B.; Xu, Y. Green financial innovation, financial resource allocation and enterprise pollution reduction. China Ind. Econ. 2023, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, M. Green finance, economic growth and environmental change: Is it possible for the environmental index in the northwest to fulfill the “Paris Agreement”? Mod. Econ. Sci. 2020, 42, 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Wang, W.; Wang, L.; Wu, J. The effects of the carbon emission reduction of china’s green finance—An analysis based on green credit and green venture investment. Finance Forum 2020, 25, 39–48+80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Q.R.; Xinshu, M.; Qamri, G.M.; Nawaz, A. From COVID to conflict: Understanding the deriving forces of environment and implications for natural resources. Resour. Policy 2023, 83, 103700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.C.; Song, H.; An, J. The impact of green finance on energy transition: Does climate risk matter? Energy Econ. 2024, 129, 107258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, J. Development of green finance and improvement of energy efficiency: Theory and China experience. Finance Forum 2024, 29, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Ma, Q. The research on the threshold and spatial effects of green finance on energy structure under the “dual-carbon” strategy. Hubei Soc. Sci. 2024, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zou, G. Research on spatial spillover effects of green finance policy on carbon emissions. Wuhan Univ. J. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2024, 77, 60–72. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; Huang, K. Eco-cities of tomorrow: How green finance fuels urban energy efficiency—Insights from prefecture-level cities in China. Energy Inform. 2024, 7, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y. Effectiveness measurement of green finance reform and innovation pilot zone. J. Quant. Techn. Econ. 2021, 38, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Liu, S. Does green financial policy promote corporate green innovations? Evidences from the green financial reform and innovation pilot zones. Contemp. Financ. Econ. 2023, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Liu, L.; Ran, Q. Does green finance improve energy efficiency?—Based on a chinese government R&D subsidy perspective. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 39, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Peng, L. Green financial development, green R& D investment and growth of enterprise total factor productivity. J. Ind. Technol. Econ. 2023, 42, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, M.; Luo, M.; Su, Y. Green finance and corporate total factor energy efficiency: Influencing mechanism and empirical test. Contemp. Econ. Res. 2024, 348, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M.; Umair, M.; Hu, J. Green finance and renewable energy growth in developing nations: A GMM analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, R.; Liu, Y.; Dong, K.; Jamasb, T. Green financing, energy transformation, and the moderating effect of digital economy in developing countries. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2024, 87, 3357–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zeng, J.; Liu, H.; Li, C. Mechanism and spatial effect of green finance promoting the pollution control and emission reduction. Econ. Geogr. 2023, 43, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Liu, J. Effect and heterogeneity of green finance in promoting high-quality economic development: From the perspectives of technological innovation and industrial structure upgrading. Econ. Rev. J. 2023, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Liu, H.; Wang, H. Green finance, green innovation, and high-quality economic development. J. Financ. Res. 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.; Zheng, Y. Does environmental policy promote energy efficiency? Evidence from China in the context of developing green finance. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 733349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Dong, Y.; Feng, B.; Zhang, H. Can green finance development promote total-factor energy efficiency? Empirical evidence from China based on a spatial Durbin model. Energy Policy 2023, 177, 113523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.C.; Chuang, H.C.; Kuan, C.M. Double machine learning with gradient boosting and its application to the Big N audit quality effect. J. Econometr. 2020, 216, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Sun, J. Does smart city construction promote urban green development? Evidence from a double machine learning model. J. Environ. Manage. 2025, 373, 123701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Jiang, J.; Guo, B.; Hu, F. The impact of “zero-waste city” pilot policy on corporate green transformation: A causal inference based on double machine learning. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1564418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Yuan, H.; Liu, Y. Mechanisms for improving urban energy use efficiency in China’ new-type urbanization construction. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2023, 33, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhao, A. Coupling mechanism of energy stability and financial security in China under the “dual carbon” goal. Econ. Rev. J. 2023, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Sun, H.; Ma, D. Research on the impact of urban green finance reform on synergizing the reduction of pollution and carbon emissions. Ind. Econ. Res. 2024, 15–28+58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q. Environmental regulation, green financial development and technological innovation of firms. Sci. Res. Manag. 2021, 42, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, Z.; Cui, J. Green finance, environmental regulation and industrial structure optimization. J. Shanxi Univ. Financ. Econ. 2022, 44, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.; Zheng, R.; Yu, D. An empirical study on the effects of industrial structure on economic growth and fluctuations in China. Econ. Res. J. 2011, 46, 4–16+31. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Sun, X.; Wang, F. Green finance, financing constrains and the investment of polluting enterprise. Contemp. Econ. Manage. 2019, 41, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Ling, H.; Chen, J. Urban green development attention and enterprise green technology innovation. J. World Econ. 2024, 47, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Li, W. Spatial effect and mechanism of technological innovation on energy use efficiency: Panel data from 278 cities at or above the prefecture level in China. J. Central South Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2024, 30, 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Mukherjee, R.; Robins, J.M. Assumption-lean falsification tests of rate double-robustness of double-machine-learning estimators. J. Econometr. 2024, 240, 105500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernozhukov, V.; Chetverikov, D.; Demirer, M.; Duflo, E.; Hansen, C.; Newey, W.; Robins, J. Double/debiased machine learning for treatment and structural parameters. Econometr. J. 2018, 21, C1–C68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, L.; Wei, P. Measuring on China’s urban capital stock at prefecture-level and higher level. Urban Probl. 2017, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; He, C. Mechanisms and tests for green finance to promote urban economic high quality development—Empirical evidence from 272 prefecture level cities in China. Rev. Invest. Stud. 2021, 40, 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Li, J. Network infrastructure, inclusive green growth, and regional inequality: From causal inference based on double machine learning. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2023, 40, 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lu, X.; Kuang, B.; Cai, D. How does the industrial land misallocation affect regional green development. China Land Sci. 2021, 35, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Li, J. A study of land price distortions affecting urban green total factor productivity: From the perspective of green innovation ability. East China Econ. Manag. 2023, 37, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farbmacher, H.; Huber, M.; Lafférs, L.; Langen, H.; Spindler, M. Causal mediation analysis with double machine learning. Econometr. J. 2022, 25, 277–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).