Abstract

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into higher education offers new opportunities for inclusive and sustainable learning. This study investigates the impact of an AI-enabled microlearning cycle—comprising short instructional videos, formative quizzes, and structured discussions—on student engagement, inclusivity, and academic performance in postgraduate management education. A mixed-methods design was applied across two cohorts (2023, n = 138; 2024, n = 140). Data included: (1) survey responses on engagement, accessibility, and confidence (5-point Likert scale); (2) learning analytics (video views, quiz completion, forum activity); (3) academic results; and (4) qualitative feedback from open-ended questions. Quantitative analyses used Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, regressions, and subgroup comparisons; qualitative data underwent thematic analysis. Findings revealed significant improvements across all dimensions (p < 0.001), with large effect sizes (r = 0.35–0.48). Engagement, accessibility, and confidence increased most, supported by behavioural data showing higher video viewing (+19%), quiz completion (+21%), and forum participation (+65%). Regression analysis indicated that forum contributions (β = 0.39) and video engagement (β = 0.31) were the strongest predictors of grades. Subgroup analysis confirmed equitable outcomes, with non-native English speakers reporting slightly higher accessibility gains. Qualitative themes highlighted interactivity, real-world application, and inclusivity, but also noted quiz-related anxiety and a need for industry tools. The AI-enabled microlearning model enhanced engagement, equity, and academic success, aligning with SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). By combining Cognitive Load Theory, Kolb’s experiential learning, and Universal Design for Learning, it offers a scalable, pedagogically sustainable framework. Future research should explore emotional impacts, AI co-teaching models, and cross-disciplinary applications. By integrating Kolb’s experiential learning, Universal Design for Learning, and Cognitive Load Theory, this model advances both pedagogical and ecological sustainability.

Keywords:

AI-enabled microlearning; inclusive digital pedagogy; Universal Design for Learning (UDL); Cognitive Load Theory (CLT); experiential learning cycle; sustainable higher education; digital equity in education; educational technology and SDGs; multimodal instructional design; AI in management education 1. Introduction

The integration of digital technologies into higher education is profoundly transforming teaching practices and opening up new perspectives to address the challenges of internationalisation, mass education, and inclusion [1]. The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) and digital learning tools represents a significant lever for improving the accessibility and quality of teaching, while supporting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 4 (quality education) and SDG 10 (reduced inequalities) [2,3]. In addition to these social dimensions, the sustainability of digital education also requires consideration of ecological impacts, such as resource efficiency and the environmental footprint of ICT infrastructures [4,5]. In a context where institutions welcome increasingly diverse cohorts, comprising students from different cultures and linguistic backgrounds, rethinking teaching methods is both an academic and a societal necessity [6].

Among the preferred pedagogical approaches in management, case studies play a central role in developing analytical, problem-solving, and decision-making skills. While this method remains valuable, it nevertheless presents certain limitations for diverse audiences. The complexity of the texts, the density of the information, and the dynamics of the discussions can pose significant obstacles for international and non-English-speaking students, who sometimes struggle to keep up or fully participate in the discussions [7]. This situation raises a significant challenge: how to maintain the pedagogical benefits of case studies while making the experience more inclusive and accessible to all student profiles. To address concerns about engaging students in deep, critical discussions, AI-driven microlearning can serve as a valuable introduction to broader discussions. The videos can provide foundational knowledge or context, which can then lead to more in-depth conversations. In doing so, microlearning enhances rather than replaces traditional methods, offering a bridge between accessibility and academic rigour [8,9].

Recent literature has explored several solutions to enhance engagement and inclusivity, including microlearning, formative quizzes, and interactive discussions [10]. However, most studies have focused on each of these approaches in isolation, without evaluating their combined effects in an integrated approach. Furthermore, few empirical studies have examined the use of AI to break down complex case studies into short, structured learning units [4,11,12]. This gap is even more pronounced in management education, where the use of AI remains relatively underdeveloped and is rarely integrated with systematic pedagogical strategies. Regarding content fragmentation, it is essential to note that the complete case study remains accessible on platforms such as Canvas. The microlearning videos are designed to complement the in-depth materials, not to replace them. They serve to clarify and facilitate understanding, helping students grasp complex subjects more effectively.

To address this gap, our research draws on three complementary theoretical frameworks. Kolb’s experiential learning cycle [13] emphasises the importance of alternating between experience, reflection, conceptualisation, and experimentation, which corresponds to the video, discussion, and quiz phases implemented in this study. This model continues to be used extensively in management and adult education [13]. The Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework [14] highlights the need to offer multiple means of representation, action, and engagement to support diverse learner profiles. UDL is especially relevant in multilingual and intercultural classrooms, where students benefit from flexibility in content delivery [15].

Finally, Cognitive Load Theory [16,17] underlines the importance of segmenting and structuring information to reduce extraneous load and enhance working memory efficiency—principles directly applicable to the design of microlearning resources. These frameworks collectively inform the logic of using atomised video cases, structured discussions, and formative quizzes as a scaffolded and inclusive learning strategy.

Regarding the digital divide, it is essential to consider that while many university students now have access to smartphones and campus Wi-Fi, disparities persist in device functionality, connectivity, and digital literacy [18]. By introducing microlearning through institutional platforms and educator facilitation, we aim to reduce initial barriers and promote more equitable access to technology-enabled learning.

While previous research has examined microlearning, AI tutoring, or inclusive design independently, few studies have combined these elements into a coherent, empirically tested model that also considers sustainability. The novelty of this study lies in empirically validating an integrated framework that links AI-enabled microlearning with inclusivity and ecological responsibility in postgraduate management education. This dual focus distinguishes the research from prior work that treated digital or inclusive innovation as separate pedagogical concerns.

RQ1: To what extent do these strategies improve engagement compared to traditional pedagogical approaches?

RQ2: To what extent do they support inclusivity, particularly for students from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds?

RQ3: What barriers remain in the implementation of these strategies, and how can they be overcome?

This research makes three key contributions. Empirically, it draws on two consecutive cohorts (n = 278) of students enrolled in a Master’s module in Supply Chain Management, employing a mixed-methods approach that integrates learning analytics from Canvas, student surveys, and qualitative thematic analysis. Mixed-methods research is especially suitable for exploring inclusive pedagogies as it captures both performance outcomes and learner perspectives [19].

From a theoretical perspective, this is the first study to systematically test AI-assisted atomisation of management case studies, grounded in experiential learning, UDL, and cognitive load frameworks. This triadic integration not only addresses a gap in the literature but also offers a replicable conceptual framework that can be applied across other disciplines and institutional settings.

Beyond its academic contribution, this research offers practical and policy implications. It provides concrete recommendations for instructors and institutions seeking to utilise ICT to support student diversity and foster more inclusive and sustainable pedagogies [4,15]. By explicitly linking pedagogical inclusivity with the ecological implications of digitalisation, this study contributes to the broader debate on how higher education can align with the Sustainable Development Goals—in particular, SDG 4 (Quality Education), SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) [20,21].

It thus highlights the potential of AI and digital technologies not only to enhance participation and equity but also to prepare graduates with the critical and systemic skills needed to address complex sustainability challenges in the 21st century.

This study offers three key contributions: (1) Conceptual—it integrates Kolb, UDL, and CLT into a unified framework for AI-enabled inclusive pedagogy; (2) Empirical—it provides large-sample, mixed-methods evidence (n = 278) of measurable gains in engagement, inclusivity, and performance; and (3) Practical—it delivers actionable recommendations for institutions seeking to align digital innovation with the Sustainable Development Goals.

In summary, the article is structured as follows: we first present the theoretical framework and previous work, then detail the methodology employed. We then present the quantitative and qualitative results, which we discuss considering the objectives of inclusion and sustainability. Finally, we conclude by proposing practical implications for instructors and policymakers, as well as avenues for future research on AI and sustainable development in higher education.

This research makes three key contributions:

- 1.

- Conceptual: It proposes an integrated model aligning Kolb’s experiential learning, Universal Design for Learning (UDL), and Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) with Sustainable Development Goals 4, 10, and 12.

- 2.

- Empirical: It provides mixed-methods evidence from two postgraduate cohorts (n = 278) demonstrating significant and equitable improvements in engagement, accessibility, and academic performance.

- 3.

- Practical: It offers a replicable, resource-efficient framework for higher-education institutions seeking to design inclusive and sustainable digital learning ecosystems.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Challenges of Management Teaching for International Students

Management teaching has historically relied on active and experiential approaches, particularly case studies, which remain a cornerstone of pedagogy in business schools and managerial training [22]. Using case studies fosters critical thinking, strategic analysis, and informed decision-making in complex and uncertain contexts [23]. By confronting students with complex problems and encouraging them to explore multiple paths to resolution, the case method seeks to replicate the real-world challenges faced by managers [13].

However, the strengths of the case method may not translate effectively across all cultural and linguistic contexts. In increasingly diverse and internationalised classrooms, the linguistic and conceptual complexity of case studies often results in significant cognitive overload for students whose first language is not English [7,24]. Research grounded in Cognitive Load Theory indicates that the simultaneous processing of unfamiliar vocabulary, idiomatic language, and cultural references can exceed learners’ working memory, impeding comprehension and critical engagement [16,17]. Native English speakers may be able to skim and infer meaning quickly, whereas international students often struggle with slower decoding and deeper contextual interpretation. This disparity manifests as asymmetrical classroom participation, with less fluent students withdrawing from fast-paced debates or contributing less confidently [7,24].

Moreover, pedagogical expectations embedded in the case method often reflect Western academic norms that prioritise oral participation, debate, and spontaneity [25,26]. In contrast, students from cultures that value reflection, silence, or collective harmony may find these expectations alienating. As such, the model risks privileging specific cultural profiles while marginalising others—undermining the very inclusivity that internationalised programmes claim to promote. These dynamics raise questions about the epistemic legitimacy of global management curricula and their ability to deliver equitable learning experiences [25].

The massification of higher education further compounds these issues. With ballooning class sizes and rising diversity, the gap between high-performing and at-risk students is widening [27]. International students who lack academic support or digital access may disengage, contributing to higher attrition rates and reproducing inequalities rather than alleviating them. These patterns run counter to Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) [21]. The hidden costs of disengagement also raise questions of sustainability at the system level, as remediation, dropout prevention, and student turnover all incur institutional inefficiencies [20].

An often-under-discussed barrier to inclusive and sustainable teaching lies not only with students, but also with educators and institutions. Adapting case-based pedagogy to meet the needs of international students requires substantial investments in educator training, time, and digital competence [28]. Simply introducing technology into teaching does not guarantee impact; it must be meaningfully integrated into redesigned pedagogical frameworks [28]. The Digital Competence of Educators (DigCompEdu) framework [29] underscores digital competence as a key component of teacher professionalism. Meanwhile, previous studies [5,30] emphasise that teacher educators act as gatekeepers of transformation: unless teachers are equipped, digital innovation will remain underutilised or misapplied.

Technological responses, such as microlearning, video-based content, and AI-enabled adaptive learning, offer promising ways to bridge linguistic and conceptual gaps [3,8]. However, these require a shift in educator mindsets and institutional investment in both time and infrastructure. Generative AI, for instance, holds potential for personalised scaffolding and multilingual support [1,21], but also introduces new pedagogical, ethical, and sustainability dilemmas [2].

Crucially, the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework provides a valuable lens for redesigning inclusive case-based teaching [15]. UDL principles encourage the provision of multiple means of representation and expression, which are essential when supporting students with diverse linguistic, cultural, and cognitive profiles [15].

Beyond pedagogical redesign, the environmental sustainability of management teaching is also underexplored. While digital resources can reduce the carbon footprint of printed case materials, they also introduce new trade-offs. The energy demands of ICT and AI systems are non-trivial [31], and their sustainability depends on access to green infrastructures and responsible governance models [4]. As van Deursen [18] notes, Digital inequality during crises, such as COVID-19, further complicates access to online resources—particularly for disadvantaged international students. Thus, digital delivery is not automatically more equitable or sustainable unless carefully designed within a socio-technical framework [20]

In summary, the challenges of management teaching for international students are deeply interconnected, encompassing cognitive and cultural barriers, teacher readiness, technological equity, and ecological sustainability. Addressing these requires more than superficial changes to existing methods; it calls for a systemic rethinking of how inclusivity, innovation, and sustainability intersect in international higher education [32]. Without such an approach, management education risks perpetuating inequities rather than addressing and transforming them.

2.2. Microlearning, Content Segmentation and Multimedia Approaches

Microlearning has gained attention as a response to the limitations of case-based pedagogy, offering targeted, bite-sized content accessible online and suited to the needs of diverse learners [3,10]. Defined as the delivery of short, focused learning units—often through videos, quizzes, or animations—microlearning promotes retention, flexibility, and just-in-time learning [8,9]. It has been widely adopted in MOOCs and blended learning environments to visualise complex concepts and enhance accessibility.

The theoretical basis for microlearning lies in Cognitive Load Theory, which highlights the limits of working memory and the need to minimise extraneous load [17]. By modularising dense case studies, microlearning helps students—particularly non-native English speakers—focus on core ideas. Multimedia Learning Theory reinforces this approach, showing how dual-channel presentation, subtitles, and visual cues enhance comprehension [8,33,34].

Nevertheless, fragmentation and shallow learning remain concerns. Microlearning can foster superficial engagement if not integrated with deeper cognitive tasks [10]. In management education, where synthesis and critical systems thinking are essential, over-reliance on short videos may hinder conceptual integration. Passive viewing, especially in large international cohorts, can mask disengagement, with language barriers intensifying comprehension gaps [35,36].

From a sustainability standpoint, microlearning supports SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) by increasing accessibility and reducing paper use [1,21]. Yet, its ecological footprint—encompassing energy for streaming, storage, and data centres—raises questions about digital sustainability [4]. Green infrastructures and lifecycle analyses are needed to ensure genuine environmental benefits [20].

Educator capacity is pivotal. Designing pedagogically robust micro-units demands subject expertise, digital literacy, and institutional support [2,5]. Without targeted professional development and workload recognition, microlearning may deepen divides between well-resourced and under-resourced institutions [5].

In summary, microlearning and multimedia tools can enhance engagement and inclusivity in international management education; however, their impact depends on thoughtful integration, educator readiness, and the development of sustainable infrastructure. They should complement—not replace—deeper reflective learning.

2.3. Structured Interactions and Continuous Assessment

Active participation is central to management education, fostering critical thinking, communication, and problem-solving [37]. Within Kolb’s experiential learning cycle [13], discussions facilitate reflective observation and collective sense-making.

However, open discussions often privilege confident, fluent speakers. Language barriers, cultural norms, and social anxiety can silence international or non-native students [38,39]. Structured discussions—guided by explicit phases, prompts, and rotating roles—promote balanced participation and inclusivity [37]. Digital tools such as forums, breakout rooms, and collaborative whiteboards extend these opportunities, allowing students to contribute at their own pace and in multiple formats [40]. Yet, without intentional design, discussions may become superficial or dominated by assertive voices [38].

Alongside discussions, formative quizzes encourage retrieval practice, strengthening memory and conceptual understanding [41,42]. Immediate feedback supports self-regulation and metacognition. Quizzes can sustain attention, foster accountability, and reduce cognitive load through short, frequent checks [16]. From a UDL perspective, varied formats, repeat attempts, and flexible timing enhance accessibility [43]. However, poorly designed quizzes risk causing stress or promoting surface learning [44,45]. Embedding higher-order tasks aligned with Bloom’s taxonomy and providing explanatory feedback improves depth and motivation [46,47].

Together, structured discussions and formative quizzes illustrate intentional interaction design, which scaffolds engagement, fosters inclusivity, and supports cognitive efficiency—particularly when integrated into microlearning cycles combining videos, reflection, and feedback.

2.4. Emerging Digital Tools and Artificial Intelligence

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is increasingly integrated into higher education, offering adaptive and interactive tools that personalise learning and automate feedback. AI-driven microlearning platforms, chatbots, and recommender systems can tailor content, pacing, and support to individual learner profiles [48]. Generative AI further enhances accessibility through multimodal outputs—such as subtitles, audio narration, or translated content—supporting diverse learners and aligning with UDL principles [49].

Building on the cognitive and design principles previously outlined, AI systems extend CLT’s segmentation strategies and UDL’s call for multiple means of engagement by dynamically adjusting cognitive load and presenting information through varied channels [1,17]. These technologies facilitate just-in-time feedback, reflective prompts, and adaptive pathways that reinforce metacognitive skills and self-regulation.

However, critical challenges persist. Over-automation can reduce learner agency, and fragmented AI-generated content may hinder conceptual integration. Concerns regarding algorithmic bias, transparency, and digital equity underline the need for human oversight and pedagogical intentionality [29,49]. Effective implementation requires educators equipped to curate, evaluate, and integrate AI tools ethically within structured, reflective learning cycles.

Recent work by Almuqhim & Berri [12] proposes an AI-driven personalised microlearning framework that parallels our segmentation strategy, while Navas Bonilla et al. [50] highlight self-directed learning with AI as a future direction for sustainable education—further validating the approach adopted in this study.

2.5. Theoretical Integration and Conceptual Framework

Although microlearning and AI-enabled strategies offer promising avenues for inclusive education, the literature reveals several unresolved gaps. Research remains fragmented, often addressing isolated benefits such as cognitive efficiency or accessibility without integrating frameworks like CLT, UDL, and experiential learning into cohesive pedagogical models [8,10]. Most studies emphasise knowledge retention rather than higher-order learning such as critical thinking, synthesis, and systemic reasoning—central to management education [22]. Empirical work linking AI-driven microlearning with reflective observation and application in complex, interdisciplinary contexts is still scarce.

Institutional and teacher readiness also remain underexplored. Successful adoption depends on educators’ digital competences, design literacy, and the capacity to align emerging tools with pedagogical objectives [5,29]. Few studies investigate how universities manage ethical risks or connect AI initiatives with sustainability objectives. Consequently, the field lacks longitudinal evidence demonstrating how AI-enhanced microlearning can simultaneously foster cognitive efficiency, inclusivity, and sustainability.

Addressing these gaps requires an integrated framework that connects learning theory, technological design, and institutional practice. The present study therefore positions AI-enabled microlearning at the intersection of three complementary perspectives—Kolb’s experiential learning cycle, UDL’s inclusive design principles, and CLT’s cognitive-efficiency mechanisms—while embedding them within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs 4, 10, and 12).

2.6. Synergistic Interaction of CLT, UDL and ELT in AI-Enabled Microlearning

Although Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory (ELT), Universal Design for Learning (UDL), and Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) derive from different pedagogical traditions, they operate synergistically in AI-enabled microlearning design. CLT provides the cognitive foundation by reducing extraneous load, allowing learners to engage meaningfully with the stages of Kolb’s experiential cycle. When unnecessary complexity is removed, learners have more working memory available for reflective observation (ELT Stage 2) and active experimentation (ELT Stage 4).

UDL acts as a bridging mechanism between CLT and ELT by operationalising inclusive access pathways. Multiple means of representation reduce linguistic and cognitive barriers in line with CLT principles, while multiple means of engagement support Kolb’s emphasis on learner agency and experimentation.

Together, these three frameworks create a learning environment in which cognitive accessibility (CLT) enables experiential progression (ELT), and UDL ensures that this process remains equitable for linguistically and culturally diverse learners. This synergistic mechanism provides the theoretical rationale for the improved comprehension, confidence, and inclusivity reported by students.

2.7. Pedagogical and Ecological Sustainability of AI in Higher Education

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and microlearning in higher education must be assessed not only through a pedagogical lens but also through a broader framework of sustainability. This dual perspective involves, on the one hand, pedagogical sustainability—ensuring the inclusivity, quality, and resilience of teaching and learning—and, on the other hand, ecological sustainability, which considers the environmental impact of digital infrastructures and practices. Together, these dimensions determine whether AI-assisted innovation aligns with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

2.7.1. Pedagogical Sustainability: Inclusivity, Equity, and Resilience

Pedagogical sustainability connects directly to SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). AI-enabled microlearning enhances inclusivity by reducing the cognitive overload associated with long, dense case studies and offering multiple modes of engagement—such as videos, transcripts, quizzes, and structured discussions—aligned with the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework [22]. This multimodality gives students from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds equitable opportunities to access and process complex content.

From a retention perspective, microlearning mitigates one of the main challenges of massified higher education: student disengagement. By offering incremental entry points into complex material, digital tools reduce the risk of alienation and attrition, which otherwise create inefficiencies and additional costs for institutions. In this sense, pedagogical sustainability is not only a matter of equity but also of institutional efficiency: students who remain engaged require fewer remedial interventions, reducing wasted time and resources.

Finally, resilience is integral to pedagogical sustainability. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed higher education’s vulnerability to disruption. Reusable digital micro-modules allow teaching to continue during crises—pandemics, conflicts, or climate events—thereby reinforcing system stability and inclusivity [22].

2.7.2. Ecological Sustainability: Efficiency and Hidden Costs

Ecological sustainability, aligned with SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), requires a critical examination of how digital infrastructures both enable and constrain sustainable education. On the one hand, AI-enabled microlearning contributes to ecological efficiency by reducing reliance on printed case studies, which often exceed 30 pages per student. Digital artefacts such as videos or quizzes can be reused across multiple cohorts and institutions, reducing the repetitive reproduction of teaching materials and optimising resource use. This scalability makes digital learning appear as a natural ally of sustainability.

However, these benefits must be balanced against the hidden ecological costs of digitalisation. ICT infrastructure and AI model training consume significant computational energy [31]. The storage and streaming of multimedia materials also contribute to carbon emissions. Sustainable educational design therefore requires a life-cycle perspective that weighs immediate resource savings against long-term.

In this study, the primary sustainability contribution lies in pedagogical and social sustainability—specifically improving accessibility (SDG 4) and reducing inequities for linguistically and culturally diverse learners (SDG 10). Quantifying the ecological impact of digital microlearning was beyond the methodological scope of this work, as such indicators vary widely depending on institutional energy infrastructures and device usage. Future research could complement this socio-pedagogical perspective with quantitative measures of digital energy consumption to produce a more comprehensive ecological sustainability assessment.

2.8. Integrated Conceptual Framework

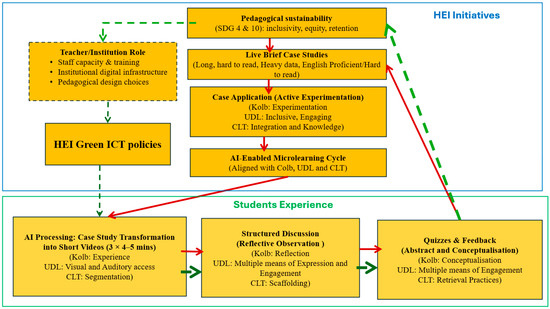

Figure 1 illustrates the integrated conceptual framework guiding this study. The model aligns the AI-enabled microlearning cycle with Kolb’s experiential learning theory, Universal Design for Learning (UDL), and Cognitive Load Theory (CLT), operationalised within institutional strategies for pedagogical sustainability linked to SDGs 4 (Quality Education) and 10 (Reduced Inequalities).

Figure 1.

Integrated conceptual framework of AI-enabled microlearning for pedagogical sustainability. This model aligns the AI-enabled microlearning cycle with Kolb’s experiential learning theory, Universal Design for Learning (UDL), and Cognitive Load Theory (CLT), operationalised within institutional strategies for pedagogical sustainability (SDGs 4 and 10). Green arrows represent institutional-level enablers, red arrows represent pedagogical flow across the microlearning cycle, and dashed arrows indicate indirect or supporting relationships.

As shown in Figure 1, higher education institutions (HEIs) play a pivotal role through staff capacity building, digital infrastructure, and pedagogical design choices. These institutional elements interact with AI-enabled microlearning processes—such as AI-based case study segmentation, structured discussions, and formative quizzes—to foster inclusive, engaging, and cognitively efficient learning experiences.

This framework provided the conceptual foundation for the design and analysis described in Section 3.

3. Methodology

This study adopts a mixed-methods design, combining quantitative and qualitative approaches to provide a comprehensive understanding of how AI-enabled microlearning cycles influence inclusivity and engagement. Artificial Intelligence (AI) was employed primarily for pedagogical structuring—specifically the atomisation of traditional case studies into segmented, multimodal learning units. While this study focused on design-level applications, future iterations may explore AI-generated feedback, adaptive content sequencing, or real-time learning analytics to enhance personalisation.

Following a convergent triangulation strategy [32], quantitative and qualitative data were collected in parallel and later integrated to identify convergence, complementarity, or divergence, ensuring comprehensive interpretation. Quantitative data objectively measured engagement (e.g., participation rates, activity completion, quiz performance), while qualitative data explored students’ perceptions, barriers, and lived experiences.

The research was conducted within a master’s programme in Supply Chain Management at a UK university, drawing on two consecutive cohorts: 2023 (n = 138) and 2024 (n = 140), for a total of 278 participants. Both cohorts comprised predominantly international students, reflecting significant linguistic and cultural diversity. This context offered a relevant setting for analysing inclusivity, mirroring the realities of globalised higher education in management disciplines.

3.1. Pedagogical Design

The pedagogical intervention was structured as a three-stage cycle. First, traditional case studies were broken down into 3–5 min AI-generated video sequences, accompanied by subtitles and transcripts, to reduce cognitive overload. Second, structured discussions followed each video, progressing from individual reflection to small-group and plenary sessions to encourage equitable participation. Third, interactive quizzes integrated into the learning platform enabled students to test comprehension immediately, with instant feedback supporting self-regulated learning. Together, these stages operationalised Kolb’s experiential learning cycle: videos offered concrete experience, discussions promoted reflective observation, and quizzes supported conceptualisation and application.

3.1.1. Data Collection and Validation

Data were collected from three complementary sources: (a) student surveys, (b) semi-structured interviews, and (c) Canvas learning analytics.

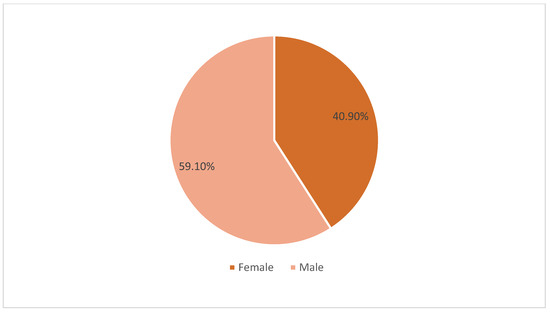

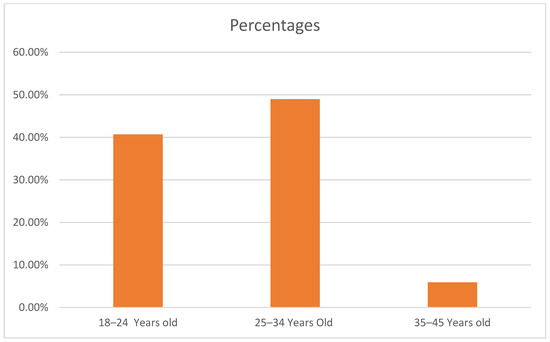

Two rounds of surveys were distributed across the 2023 and 2024 cohorts, combining Likert-scale items (1–5) measuring perceptions of accessibility, engagement, inclusivity, confidence, and stress with two open-ended questions to gather qualitative reflections. The qualitative dataset was further enriched through semi-structured interviews conducted with 10 students in 2023 and 8 students in 2024. An assistant researcher facilitated recruitment, obtained consent, and anonymised transcripts. Each interview lasted approximately 25–30 min and followed a flexible guide focusing on accessibility, engagement, and the perceived inclusivity of AI-enabled learning materials. To contextualise the sample, Figure 2 presents the gender distribution of participants, and Figure 3 displays the age composition across the 2023–2024 cohorts.

Figure 2.

Respondents’ Gender Distribution (both cohorts 2023–2024).

Figure 3.

Respondents’ age distribution (both cohorts 2023–2024).

All participants received an information sheet outlining the purpose of the study, consent procedures, and their right to withdraw at any time without penalty. The ethics committee’s contact details were included in the consent form. The deputy head of department acted as a gatekeeper, overseeing data access on Canvas and ensuring ethical compliance.

Thematic saturation was reached after fewer than ten interviews in 2023 and eight in 2024, with recurring patterns aligning closely with the open-ended survey questions. This convergence between interview and survey data strengthened the validity of the qualitative findings.

Survey scales were adapted from validated instruments in previous studies on digital and microlearning engagement [9,10]. Content validity was confirmed through expert review by three faculty members in educational technology, and a pilot test (n = 32) verified clarity and reliability prior to full deployment. Internal consistency values (Cronbach’s α = 0.83–0.91) are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Constructs measured, sample survey items, and reliability indices (Cronbach’s α = 0.83–0.91), confirming the internal consistency of all subscales.

Canvas learning-analytics data—including video-viewing rates, quiz completion, discussion participation, and grade records—were extracted for the 2022, 2023, and 2024 cohorts to capture longitudinal engagement trends.

3.1.2. Data Analysis and Reflexivity

Quantitative data were analysed using descriptive and comparative statistics, including cohort difference tests. Qualitative data from open-ended survey questions and interviews were analysed thematically, following an inductive approach [32,51,52] to identify recurrent themes relating to engagement, inclusivity, and perceived barriers. The researcher read all responses and transcripts repeatedly to gain familiarity with the data and generated initial codes directly from participants’ words in a data-driven manner. Codes were iteratively refined and grouped into broader themes such as accessibility, engagement, inclusivity, and cognitive load. Although the coding was conducted by the instructor–researcher, an assistant researcher anonymised transcripts and verified the coding scheme for reliability. Reflexive notes and cross-checking were used throughout to reduce interpretive bias.

In line with the study’s sustainability goals, the methodology explicitly targeted inclusivity and equitable participation, aligning with SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). Multilingual captions, structured discussion phases, and multimodal resources were designed to reduce barriers for non-native speakers and promote fairer participation across diverse cohorts.

3.1.3. Integration of CLT, UDL and Experiential Learning Within the Methodological Design

To demonstrate how theoretical frameworks informed the methodological choices of this study, this subsection explains the integration of Cognitive Load Theory (CLT), Universal Design for Learning (UDL), and Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory (ELT) within the intervention’s design. The methodological design directly operationalised the synergy between CLT, UDL, and ELT. CLT informed the segmentation of long case studies into short, multimodal learning units to minimise extraneous cognitive load, enabling students—particularly non-native speakers—to process information more efficiently. UDL principles shaped the provision of multiple means of representation (videos, captions, transcripts) and multiple means of engagement (structured discussions and formative quizzes), supporting equitable access for a linguistically diverse cohort. ELT structured the sequencing of activities: videos provided concrete experience, discussions facilitated reflective observation, and quizzes enabled conceptualisation and application. Together, this integrated design underpinned a more inclusive and cognitively efficient learning environment, aligning the methodological choices with the sustainability goals of SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities).

3.1.4. Cohort Coverage and Data Scope

Canvas learning-analytics indicators (e.g., weekly participation frequency and pages viewed per student) were collected for three cohorts: 2022, 2023, and 2024. Survey-based analyses compare 2023 and 2024, while Canvas-based figures report longitudinal engagement trends across 2022–2024. For comparability, Canvas indicators were normalised to the 2023 baseline (2023 = 100%), and checks using raw values showed consistent patterns.

Ethical approval was granted by the institutional review board. Participation was voluntary, informed consent was obtained, and all data were anonymised and stored securely in accordance with GDPR.

AI was used in three capacities: (1) generatively, via ChatGPT and Adobe Express, to segment case studies and generate captions; (2) analytic, through Canvas Insights to ex-tract engagement data; and (3) assistive, to support transcript summarisation and visual generation.

(1) generative, using ChatGPT (OpenAI, version 4.5, 2023 and 2014) and Adobe Express (Adobe Inc., version 2024.9) to segment case studies and generate captions; (2) analytic, using Canvas Insights (Instructure, version 2023 and 2024) to extract engagement data; and (3) assistive, using Grammarly (Grammarly Inc., version 2024.10) to support transcript summarisation, minor grammar refinement, and visual generation.

No AI tool was used to replace human interpretation or to generate findings; all analyses and thematic interpretations were performed by the authors.

4. Results

This section integrates survey data, learning analytics, student grades, and qualitative insights across two consecutive cohorts (2023, n = 138; 2024, n = 140). Findings are organised into six subsections: (1) descriptive statistics, (2) inferential analysis, (3) subgroup analysis, (4) learning analytics and academic performance, (5) qualitative themes, and (6) triangulation. Together, they provide a holistic picture of how AI-enabled microlearning influenced engagement, inclusivity, and sustainability in postgraduate management education.

The qualitative component comprises a thematic analysis of open-ended survey responses and sentiment analysis of textual feedback, providing insights into perceptions, emotions, and suggestions for improvement.

Triangulating these complementary data sources enables a multidimensional understanding of how microlearning cycles—comprising preparatory videos, formative quizzes, and structured discussions—affect both cognitive and affective aspects of learning. This integration aligns with recommendations for evidence-informed pedagogy in complex and diverse learning environments, supporting a robust interpretation of observed trends.

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics from the survey data collected across two consecutive cohorts (2023, n = 138; 2024, n = 140). Six constructs were measured using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree): accessibility of learning materials, clarity of case study content, engagement during sessions, inclusivity of participation, confidence in contributing to discussions, and reduced stress through scaffolding.

Across both cohorts, the mean values consistently exceeded the neutral midpoint, indicating generally positive student perceptions of the AI-enabled microlearning approach. Between 2023 and 2024, all constructs demonstrated measurable improvement, with the most notable increases observed in content clarity (+0.47) and confidence in participation (+0.46). Accessibility (+0.44), inclusivity (+0.44), and engagement (+0.42) also showed substantial improvements, while stress reduction (+0.47) demonstrated moderate yet meaningful progress.

The standard deviations (0.63–0.72) indicate moderate variability across responses, suggesting broad agreement among students regarding the effectiveness of the intervention. The internal reliability of the instrument was high (Cronbach’s α = 0.89), confirming strong internal consistency across the six constructs.

These patterns suggest that the integration of short videos, low-stakes quizzes, and structured discussions contributed to more accessible, clearer, and engaging learning experiences. The positive shift across all dimensions provides preliminary evidence that the intervention outperformed traditional, lecture-based approaches by enhancing both cognitive and affective aspects of learning.

In summary, the descriptive results indicate consistent, cross-dimensional improvements in student perceptions of learning quality, inclusivity, and confidence. The findings justify the use of inferential analysis to determine whether these observed gains are statistically significant and educationally meaningful, as examined in Section 4.2. All significant differences were associated with large effect magnitudes (Cohen’s d > 0.80) and 95% confidence intervals excluding zero, confirming the robustness of these improvements.

4.2. Inferential Analysis

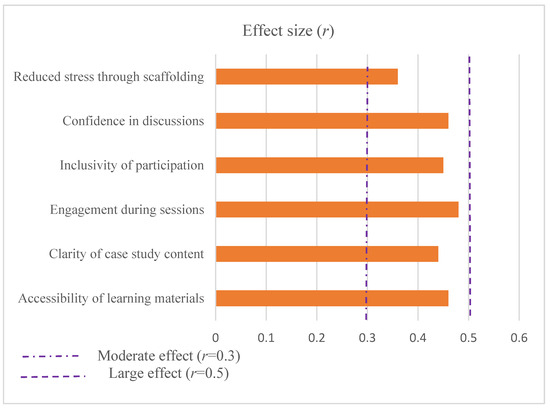

To test whether the observed improvements between the 2023 and 2024 cohorts were statistically significant, a series of Wilcoxon signed-rank tests was conducted for each construct. This non-parametric approach was selected because the Shapiro–Wilk tests confirmed that the data did not follow a normal distribution (p < 0.001). Effect sizes (r) were calculated by dividing the Z-statistic by the square root of the total number of observations, allowing for the interpretation of the magnitude of change [53].

Results (Table 2) show statistically significant improvements across all six dimensions (p < 0.001), with medium to large effect sizes (r = 0.35–0.48). The most significant improvements were observed in engagement, accessibility, and confidence, indicating that the intervention substantially enhanced both behavioural and cognitive dimensions of learning. These patterns are supported by the Wilcoxon signed-rank tests summarised in Table 3, which indicate statistically significant improvements across all dimensions (p < 0.001) and medium-to-large effect sizes (r = 0.36–0.48) [54]. Figure 4 visually illustrates these effect sizes, showing that all six constructs exceed the moderate-effect threshold and cluster near the large-effect benchmark, offering a clear graphical confirmation of the strength of the improvements.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of survey responses for the 2023 and 2024 cohorts.

Table 3.

Wilcoxon signed-rank tests comparing the 2023 and 2024 cohorts.

Figure 4.

Effect sizes (r) for improvements between 2023 and 2024 cohorts across six learning constructs. The dotted lines mark reference thresholds for moderate (r = 0.3) and significant (r = 0.5) effects. All constructs exceeded the moderate threshold, confirming the substantial pedagogical impact of the AI-enabled microlearning cycle.

Results of Wilcoxon signed-rank tests comparing the 2023 and 2024 cohorts indicated significant improvements across all constructs (p < 0.001), with large effect sizes (r = 0.44–0.48) and 95% confidence intervals excluding zero, confirming the robustness of these gains and the positive impact of the AI-enabled microlearning cycle.

All six constructs improved significantly, confirming that the AI-enabled microlearning approach produced measurable benefits over previous, more traditional teaching formats. The most significant effects in engagement and confidence suggest that the cyclic design—comprising preparatory videos, formative quizzes, and structured discussions—enhanced motivation, understanding, and participation.

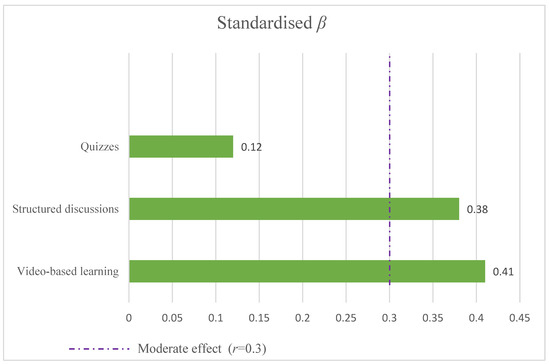

To further explore the factors influencing overall student satisfaction, a multiple linear regression analysis was conducted using satisfaction as the dependent variable and three key pedagogical components as predictors: video-based learning, quizzes, and structured discussions. The model explained a substantial proportion of the variance (R2 = 0.43, p < 0.001), indicating that these elements jointly account for nearly half of the variation in satisfaction scores. The regression results are summarised in Table 4, which presents the standardised coefficients and significance levels for each pedagogical predictor. Figure 5 visualises the relative contributions of the three predictors, illustrating their respective effect sizes within the regression model.

Table 4.

Regression model predicting overall satisfaction.

Figure 5.

Multiple linear regression predicting overall student satisfaction. The model included three pedagogical predictors—video-based learning, quizzes, and structured discussions—and explained 43% of the variance in satisfaction scores (R2 = 0.43, p < 0.001).

The analysis reveals that videos and structured discussions were the most influential contributors to student satisfaction, while quizzes, though positively correlated, had a smaller and statistically non-significant effect. This pattern suggests that cognitive scaffolding and collaborative reflection played a more decisive role than assessment alone.

These findings can be interpreted through the lens of Cognitive Load Theory [17] and Kolb’s experiential learning cycle [13].

- Videos segmented complex case studies into manageable units, reducing extraneous load and supporting comprehension.

- Discussions facilitated reflective observation and abstract conceptualisation, deepening understanding and fostering critical thinking.

- Quizzes, while aiding retrieval practice, may have induced residual anxiety, as discussed later in Section 5.4.

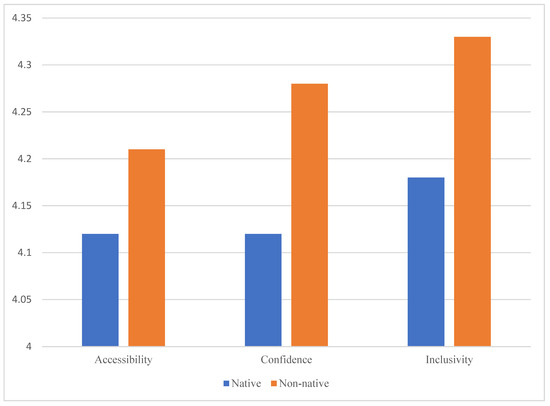

In sum, the inferential results confirm that the observed improvements across cohorts are both statistically significant and educationally meaningful. The following section explores whether these benefits were equitably distributed across demographic groups, addressing inclusivity and potential disparities. Table 5 presents the subgroup comparison between native and non-native English speakers across accessibility, confidence, and inclusivity. Figure 6 provides a visual comparison of the mean scores for both groups across the three constructs.

Table 5.

Subgroup comparison by English language background (2024 cohort).

Figure 6.

Mean survey scores for native and non-native English speakers across accessibility, confidence, and inclusivity.

Non-native students reported marginally higher perceptions across all three constructs—accessibility, confidence, and inclusivity—indicating that the AI-enabled microlearning cycle effectively supported equitable participation. Although these differences were not statistically significant, the consistent upward trend suggests that inclusive design features, such as captioned videos, transcripts, and structured discussions, helped mitigate linguistic barriers and enhance learner confidence. Structured small-group discussions—effectively mitigated linguistic barriers and enhanced confidence.

4.2.1. Interpretation

The absence of significant gaps across demographic groups demonstrates that the AI-enabled microlearning model achieved pedagogical equity, benefiting all learners without exacerbating existing disparities. The slight advantage for non-native speakers reflects the value of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles, which recommend offering multiple means of representation and expression to accommodate diverse learning preferences [15].

Qualitative testimonies reinforce these findings. One student remarked:

“In small groups, I had time to think and speak. I would not talk in big groups, but here I felt included.”

Such reflections confirm that the scaffolded, multimodal design supported psychological safety and inclusive participation, especially for students who might otherwise remain silent in large, lecture-based environments.

4.2.2. Alignment with SDG 10

These results align with Sustainable Development Goal 10 (Reduced Inequalities) by demonstrating that digital pedagogical innovation can narrow participation gaps linked to language and confidence. The intervention redistributed learning opportunities more equitably, promoting social sustainability alongside academic excellence.

4.2.3. Summary

Overall, the subgroup analysis confirms that the benefits of AI-enabled microlearning were consistently experienced across all demographics, with non-native English speakers showing marginally higher gains in accessibility and confidence. This indicates that the approach not only enhanced learning for the majority but also levelled the field for linguistically diverse students.

The Section 4.3 examines objective engagement metrics and academic outcomes to determine whether these perceived improvements translated into measurable behavioural and performance gains.

4.3. Learning Analytics and Academic Performance

To complement the survey data, learning analytics from the institutional Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) were examined to assess whether perceived improvements translated into measurable engagement and performance gains. Metrics included:

- Participation frequency (forum posts, quiz attempts, interactions)

- Page views (resource access patterns)

- Number of active students engaging with learning materials weekly

These indicators were normalised to the 2023 baseline cohort to enable year-on-year comparison.

4.3.1. Participation Trends

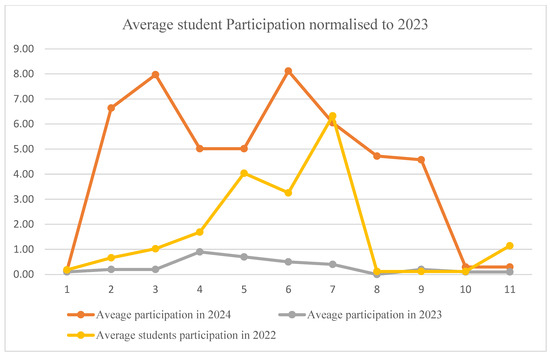

Figure 7 illustrates a notable increase in average participation across the semester for the 2024 cohort compared to the 2023 and 2022 cohorts. Peaks occurred around Weeks 4–7, aligning with major case study milestones and assessment activities.

Figure 7.

Average student participation per week (2022, 2023 and 2024), number of students normalised to 2023.

- 2024 cohort: consistently higher engagement, reaching nearly 8 interactions per student at mid-semester.

- 2023 cohort: moderate increase (~2 interactions) with plateau after Week 6.

- 2022 cohort: minimal engagement (<1 interaction).

These data demonstrate that the AI-enabled microlearning cycle fostered sustained behavioural engagement, particularly during cognitively demanding phases of the module. The segmentation of content into short videos and structured discussion prompts appears to have scaffolded active participation across the semester.

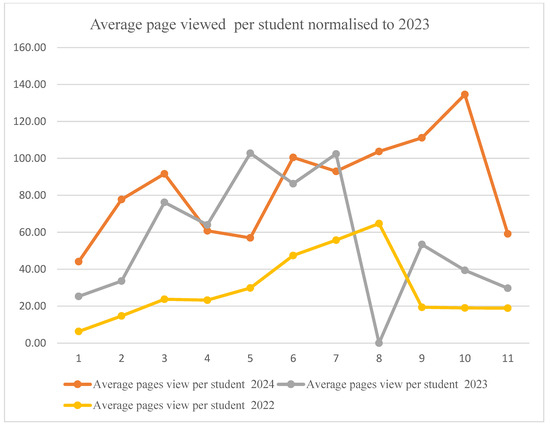

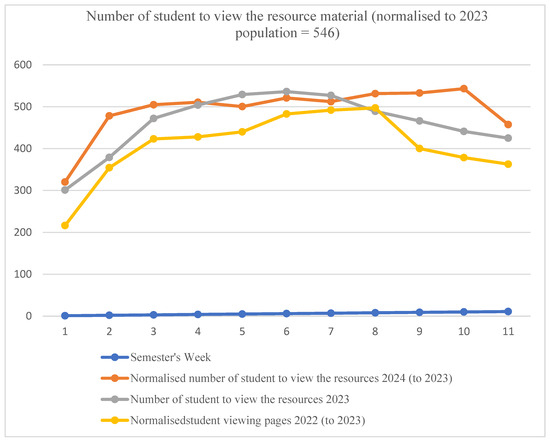

Figure 7 and Figure 8 visualise the Canvas learning-analytics data across the three cohorts (2022–2024). Figure 7 shows weekly participation frequency per student, while Figure 8 presents the average number of pages viewed per student. Both are normalised to the 2023 baseline, illustrating a clear upward trend in retention, resource access, and overall engagement following the introduction of AI-enabled microlearning.

Figure 8.

Average pages viewed per student per week (2022, 2023 and 2024); number of students normalised to 2023.

4.3.2. Resource Access Patterns

Figure 8 reports the average number of pages viewed per student per week. The 2024 cohort consistently accessed more resources than earlier cohorts. Notably, resource engagement spiked in Weeks 4, 7, and 10, coinciding with key learning and assessment cycles.

This sustained access suggests that students utilised preparatory materials more strategically, indicating improved self-regulation and study planning—an essential component of cognitive engagement and pedagogical sustainability.

4.3.3. Active Student Engagement

Figure 9 illustrates the number of students actively viewing resources throughout the semester. In 2024, engagement levels rose rapidly in the first three weeks and stabilised above 500 active students, surpassing both 2023 and 2022. This early adoption indicates that learners embraced the digital learning environment sooner, likely facilitated by clearer navigation, structured videos, and accessible scaffolding.

Figure 9.

Weekly number of students viewing resource materials (normalised to 2023).

4.3.4. Academic Performance Outcomes

The behavioural improvements reflected in the analytics were mirrored in academic outcomes:

- Average final grade: increased from 64.7% (2023) to 73.5% (2024) (p < 0.001).

- Completion rates: rose by 14%, with fewer non-submissions.

- Grade distribution: higher proportion of Merit and Distinction classifications.

A multiple regression analysis combining key engagement metrics (video views, quiz completion, forum posts) explained 36% of the variance in final grades (R2 = 0.36, p < 0.001).

- Forum participation was the strongest predictor (β = 0.39, p < 0.001).

- Video views contributed significantly (β = 0.31, p < 0.01).

- Quiz completion showed a weaker but positive effect (β = 0.18, p < 0.05).

These results confirm that multimodal engagement, rather than reliance on any single tool, drove improved academic achievement.

4.3.5. Interpretation

The analytics triangulate with survey data, indicating that AI-enabled microlearning enhanced both behavioural engagement and cognitive outcomes. The observed patterns align with Cognitive Load Theory, as segmentation and retrieval practice reduced overload, while reflective discussions deepened understanding.

From a sustainability perspective, the digital-first approach supports SDG 4 (Quality Education) by fostering continuous engagement and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) by ensuring equitable access across diverse learners.

4.4. Qualitative Themes

A thematic analysis of open-ended survey responses (n = 53 for effectiveness; n = 51 for suggestions) revealed five dominant themes reflecting students’ perceptions of the AI-enabled microlearning approach:

- (1)

- Interactive and Practical Learning,

- (2)

- Real-World Application through Case Studies and Simulations,

- (3)

- Feedback and Support,

- (4)

- Digital Tools and Industry Relevance, and

- (5)

- Inclusivity and Confidence.

These themes provide qualitative depth to the quantitative findings reported in Section 4.1, Section 4.2, Section 4.3 and Section 4.4.

Theme 1: Interactive and Practical Learning

Students consistently praised the interactive and hands-on nature of the redesigned module. Activities such as group discussions, collaborative projects, and practical exercises helped them apply theory to real-world contexts and fostered engagement:

“The integration of interactive and practical learning techniques has been the most effective aspect for me. Group discussions and hands-on activities helped me better understand complex concepts by applying them in real-time scenarios.”

This confirms the significant gains in engagement (+0.42) identified quantitatively and aligns with Kolb’s experiential learning theory, particularly the active experimentation phase. Through structured interaction, learners transitioned from passive receivers to active co-constructors of knowledge.

Theme 2: Real-World Application through Case Studies and Simulations

Students valued case-based learning and simulations for connecting abstract theory to authentic supply chain challenges:

“The case studies provided real business scenarios, allowing me to apply theoretical concepts to practical problems.”

“Interactive simulations helped me grasp complex concepts like demand forecasting and inventory management by immersing me in decision-making processes.”

These findings reinforce the high ratings for clarity (+0.47) and accessibility (+0.44), suggesting that AI-enabled microlearning enhanced conceptual understanding by segmenting complex content (CLT) and situating learning in authentic contexts.

Theme 3: Feedback and Support

Many students highlighted the importance of structured feedback sessions in promoting clarity and confidence:

“The structured feedback sessions after assignments were invaluable, providing clear guidance on areas of improvement.”

This reflects the improved confidence (+0.46) and reduced stress (+0.47) reported in survey data. Regular, formative feedback supported reflective observation in Kolb’s cycle and scaffolding in CLT, helping students identify learning gaps and adjust their strategies.

Theme 4: Digital Tools and Industry Relevance

Students suggested expanding exposure to industry-standard tools and guest speakers to enhance employability further:

“Incorporating more hands-on tools and software training (like SAP) would be incredibly beneficial.”

“More guest speakers from diverse industries could offer a wider perspective on global supply chain practices.”

While overall satisfaction was high, this theme highlights a future direction for curriculum development: integrating enterprise systems and digital simulations to strengthen the link between skills application.

Theme 5: Inclusivity and Confidence

Several responses emphasised the module’s supportive and inclusive design. Students appreciated collaborative discussions, which built confidence—especially for those less comfortable speaking in large classes:

“In small groups, I had time to think and speak. I would not talk in big groups, but here I felt safe and included.”

This corroborates the positive inclusivity gains (+0.44) and higher improvements among non-native speakers identified in subgroup analysis (Section 4.3). It also reflects the principles of UDL, which encourage multiple means of engagement and expression to accommodate diverse learners.

Summary of qualitative data

The qualitative findings converge with quantitative evidence, indicating that AI-enabled microlearning fostered:

- Active engagement through interactive learning,

- Deeper understanding via simulations and case applications,

- Emotional safety and confidence through feedback and small-group discussion, and

- Inclusive access for linguistically diverse learners.

At the same time, students’ constructive suggestions—such as expanding digital tool use and industry exposure—reveal opportunities for continuous improvement and pedagogical sustainability.

These themes feed into the triangulation analysis described in the Methodology (Section 3), confirming that that microlearning enhanced accessibility, engagement, and inclusivity, while residual stress around assessments and resource limitations remain areas for refinement.

Theoretical Interpretation: How Students’ Experiences Reflect CLT–UDL–ELT Interaction

The qualitative findings also illustrate how the Cognitive Load Theory (CLT), Universal Design for Learning (UDL), and Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory (ELT) interacted in practice during the module. One participant explained:

“When I read the case study, there is so much information, and I have to concentrate on the English. When I move to the second paragraph, I forget the first one. But with the videos, I remember the images and the animations immediately.”

This comment encapsulates the core mechanism of the integrated framework. The microlearning videos reduced extraneous cognitive load (CLT) by structuring information visually and narratively, freeing up working memory for deeper processing. This, in turn, supported the learner’s movement through Kolb’s experiential cycle—particularly reflective observation and active experimentation—because the material became cognitively manageable.

At the same time, the multimodal design aligned with UDL principles by providing multiple means of representation. For a linguistically diverse learner, the combination of visuals, narration, and segmentation created accessible entry points that reduced language-related barriers and enhanced retention.

In combination, the themes show that cognitive accessibility (CLT) enabled experiential engagement (ELT), and UDL ensured that these benefits were equitably distributed across students with varying linguistic and cultural backgrounds.

5. Discussion

This section interprets the results in light of the study’s three guiding questions:

- (1)

- the extent to which AI-enabled microlearning improved student engagement compared to traditional approaches;

- (2)

- its effectiveness in fostering inclusivity, particularly for culturally and linguistically diverse learners; and

- (3)

- the remaining barriers and their implications for pedagogical sustainability.

Findings demonstrate that AI-enabled microlearning enhanced engagement, confidence, and accessibility across cohorts, with positive effects confirmed through behavioural analytics and improved academic performance. However, residual quiz-related anxiety and calls for greater integration of professional tools suggest areas for refinement.

5.1. Enhancing Engagement and Reducing Cognitive Load

The significant gains in engagement (+0.42), accessibility (+0.44), and clarity (+0.47), corroborated by analytics showing a 19% rise in video views and 65% increase in forum activity, indicate that the AI-enabled microlearning cycle effectively promoted sustained participation and deeper learning.

These outcomes align with Cognitive Load Theory [16], which posits that segmentation and scaffolded practice reduce extraneous load and facilitate schema construction. Short videos allowed students to process information incrementally, while structured discussions encouraged knowledge integration and application. The results are consistent with Almuqhim and Berri [12] who show that AI-enabled microlearning environments support learner engagement by tailoring content into cognitively manageable units. Although their study focuses on engineering education, the underlying mechanisms—personalisation, segmentation, and multimodal delivery—parallel the benefits observed in this postgraduate business module.

In contrast to traditional lecture-based formats, this cyclical model—video preparation → reflective discussion → formative quizzes—supported active knowledge construction, echoing Kolb’s experiential learning cycle [13] across its stages:

- Concrete experience through video-based exposure,

- Reflective observation via discussion forums,

- Abstract conceptualisation through feedback, and

- Active experimentation during case analysis.

The combination of microlearning and AI-enhanced accessibility (captions, transcripts, adaptive feedback) thus promoted cognitive engagement, time-on-task, and academic achievement, demonstrating superior outcomes compared to prior cohorts using static, text-heavy materials. These patterns confirm the synergistic operation of the three frameworks: segmentation reduced cognitive load (CLT), multimodal presentation enhanced accessibility (UDL), and the cyclical sequence of experience–reflection–application sustained engagement (Kolb).

5.2. Fostering Inclusivity and Equitable Participation

The absence of significant demographic differences, coupled with slightly higher accessibility gains for non-native English speakers, underscores the intervention’s inclusive design.

Features such as captioned videos, transcripts, and small-group reflective discussions align with Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles, which advocate multiple means of representation, expression, and engagement [15].

Student testimonies—“In small groups, I had time to think and speak”—highlight how scaffolded reflection provided psychological safety for culturally and linguistically diverse learners.

These findings support SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) by demonstrating that digital pedagogical innovation can redistribute learning opportunities and enhance confidence across diverse cohorts. Inclusivity in participation, combined with rising academic performance, reflects a socially sustainable approach to higher education.

5.3. Linking Engagement to Academic Outcomes

The regression results (R2 = 0.36, p < 0.001) revealed that forum participation (β = 0.39) and video engagement (β = 0.31) were the strongest predictors of final grades, while quizzes played a supportive but secondary role (β = 0.18).

This suggests that social and reflective dimensions of learning—rather than assessment alone—drive performance gains.

The findings extend prior work on active and collaborative learning by showing that AI-assisted scaffolds (e.g., adaptive video content and captioning) create more equitable pathways to success.

5.4. Remaining Barriers: Emotional and Infrastructural

Despite overall improvements, two barriers persist:

- Affective barriers—While students acknowledged quizzes as helpful for self-assessment, some described them as “anxious moments”, indicating residual assessment-related stress. This tension aligns with prior literature [45] and highlights the need for compassionate assessment design—low-stakes, feedback-oriented, and self-paced.

- Infrastructural barriers—Several students requested greater exposure to professional tools (e.g., SAP, simulation software) and guest speakers, indicating an appetite for industry-aligned digital literacy. Addressing this requires institutional investment in staff training and partnerships, consistent with HEI Green ICT policies.

- Two alternative explanations should also be considered. First, a novelty effect may have temporarily boosted motivation due to the newness of AI-based resources. Second, the instructor’s dual role may have influenced student enthusiasm. Both factors were acknowledged and mitigated through anonymisation and replication across two cohorts.

5.5. Pedagogical Sustainability and Alignment with SDGs

The intervention contributes to pedagogical sustainability by enhancing:

- Engagement and retention (SDG 4: Quality Education),

- Equity and inclusion (SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities),

- Resource efficiency (SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production) through reduced reliance on printed materials and reusable digital assets.

By integrating AI-driven microlearning with UDL and CLT frameworks, the approach exemplifies a systemic shift toward sustainable, resilient, and inclusive higher education.

Such models not only improve learning outcomes but also strengthen institutional adaptability in digitally mediated environments.

To contextualise these results, a comparative summary of prior microlearning and AI-enabled pedagogy studies is provided in Table 6. The table highlights areas of consistency—such as improved engagement and inclusivity—and notes persistent challenges including cognitive overload and assessment anxiety.

Table 6.

How this research’s results align with and extend prior research on AI-enabled microlearning.

Table 6.

How this research’s results align with and extend prior research on AI-enabled microlearning.

| Study | Focus/Context | Method | Key Findings | Relation to Current Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almuqhim and Berri [12] | AI-driven personalised microlearning for e-learning | Conceptual model | Improved learner adaptability and motivation | Supports engagement effect observed in this study |

| Navas-Bonilla et al. [51] | Self-directed learning with AI | Systematic review | Emphasised autonomy and self-regulation | Complements findings on confidence and independence |

| Zulfa et al. [6] | AI, microlearning, and gamification | Empirical survey | Reported higher participation and satisfaction | Reinforces inclusivity and engagement patterns |

| Bruck. Motiwalla and Foerster [14] | Microlearning in higher education | Experimental | Increased retention but limited critical thinking | Confirms engagement benefit; highlights need for deeper reasoning |

| Current Study | AI-enabled microlearning in postgraduate management education | Mixed-methods (n = 278) | Enhanced engagement, inclusivity, and performance; sustainable digital pedagogy | Extends previous work by integrating CLT, UDL, Kolb + SDGs |

5.6. Applicability Across Disciplines and Resource Contexts

Although this study was conducted within a single postgraduate supply chain management module, the underlying microlearning model is transferable to other disciplines and teaching environments. The tri-framework design—segmenting complex content (CLT), supporting experiential progression (ELT), and providing multiple pathways for engagement (UDL)—is content-neutral and can be applied in any subject where learners face cognitive or linguistic barriers. In STEM subjects, complex procedures or theoretical constructs could be transformed into multimodal micro-units to scaffold understanding. In the humanities and social sciences, long readings or ethnographic cases can similarly be atomised to support comprehension and reflection. Importantly, the approach can also be adapted for less digitally resourced contexts through low-tech alternatives such as narrated slides, static visual summaries, or text-based micro-scenarios delivered through learning platforms or mobile messaging. Thus, the effectiveness of the model rests not on advanced technology but on its underlying design principles, suggesting a wider relevance beyond the specific module examined here.

5.7. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

While this study offers compelling evidence of the benefits of AI-enabled microlearning, its generalisability is constrained by the specific context—a postgraduate business module at a UK university. Further research across disciplines (e.g., STEM, arts, humanities) and institutional types (e.g., non-English-speaking regions, under-resourced institutions) is necessary to confirm the model’s broader applicability.

Furthermore, if the findings are robust, three limitations should be noted:

- Context specificity—The study was confined to a single postgraduate module in supply chain management; broader validation across disciplines is needed.

- Temporal scope—Data across two years capture immediate effects; longitudinal studies could examine knowledge retention and transfer.

- Technological scope—AI was primarily used for content segmentation and scaffolding; future research could explore adaptive AI tutors or chatbots for personalised feedback.

Future work should also examine:

- The emotional impact of micro-assessments,

- Faculty readiness for AI-assisted pedagogy, and

- The ecological footprint of digital learning infrastructures.

5.8. Summary

The AI-enabled microlearning cycle significantly improved engagement, inclusivity, and academic outcomes, offering a replicable model for sustainable digital pedagogy.

By aligning learning design with Kolb’s experiential cycle, UDL principles, and CLT, the approach demonstrates that technology-enhanced learning can be both pedagogically effective and socially equitable. These patterns confirm the synergistic operation of the three frameworks: segmentation reduced cognitive load (CLT), multimodal presentation enhanced accessibility (UDL), and the cyclical sequence of experience–reflection–application sustained engagement (Kolb).

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study examined the impact of an AI-enabled microlearning cycle—comprising short videos, formative quizzes, and structured discussions—on student engagement, inclusivity, and academic performance in postgraduate management education. Using a mixed-methods approach across two cohorts (2023–2024), integrating surveys, learning analytics, and qualitative testimonies, the findings revealed statistically significant improvements in engagement, confidence, and accessibility, with strong behavioural and performance gains.

The intervention demonstrated that AI-assisted segmentation and scaffolded discussions not only enhanced comprehension and participation but also supported equitable outcomes for linguistically and culturally diverse learners. The results affirm that AI-enabled microlearning represents a pedagogically sustainable model—promoting both educational excellence and social inclusion, consistent with SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities).

However, challenges remain. While retrieval-based quizzes improved learning, some students experienced assessment-related anxiety. In addition, participants expressed a desire for greater exposure to professional tools and industry-led simulations, signalling the need for continuous enhancement of digital and employability skills.

6.1. Key Contributions

This study makes several key contributions to the field of inclusive and sustainable higher education. First, it offers a clear example of pedagogical innovation, demonstrating how AI-enabled microlearning can reduce cognitive overload, increase student participation, and enhance learning outcomes through structured, multimodal instructional design. Second, it validates the practical application of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles in higher education settings, showing that such frameworks can deliver equitable benefits across diverse demographic groups, particularly for international and non-native English-speaking students.

Third, the study contributes to the literature on sustainability in educational practice by proposing a replicable and low-resource model that supports both digital equity and environmental responsibility. The use of reusable digital content, such as captioned videos and formative quizzes, minimises material use and maximises scalability. Finally, the research offers a novel theoretical integration by aligning Kolb’s experiential learning cycle, Cognitive Load Theory (CLT), and UDL into a coherent instructional framework. This alignment not only underpins the intervention’s design but also provides a conceptual foundation for future pedagogical strategies that balance engagement, accessibility, and sustainability.

6.2. Practical Recommendations for Higher Education Institutions (HEIs)

Based on these findings, the study proposes a series of practical recommendations for higher education institutions seeking to enhance inclusion, engagement, and sustainability in digital learning environments. Institutions are encouraged to adopt AI-enabled microlearning cycles, which combine short, captioned videos, low-stakes formative quizzes, and scaffolded discussions to foster student engagement and improve accessibility. Alongside this, educators should embed UDL principles into curriculum design by offering multiple means of representation, engagement, and expression—an approach that is particularly effective for supporting non-native English speakers and students with varied learning needs.

Furthermore, it is essential to design compassionate assessments that prioritise formative, feedback-rich, and low-pressure evaluation methods. This can help reduce student anxiety while enhancing motivation and self-regulation. Institutions should also invest in staff development, equipping educators with training in AI-assisted content creation, learning analytics interpretation, and inclusive pedagogical practices. In addition, fostering partnerships with industry can enrich academic curricula by integrating professional tools (such as SAP or simulation software) and inviting guest speakers to bridge the gap between academic learning and employability outcomes. Finally, institutions should leverage learning analytics to monitor engagement patterns, enabling early identification of at-risk students and the provision of timely, targeted support throughout the learning process.

6.3. Recommendations for Future Research