Population Growth–Decline Differentiation and Regional Inequality in the Yangtze River Delta: Implications for Sustainable Regional Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

- identify spatial clustering patterns of population change;

- measure regional inequality across provincial, municipal, and county levels;

- assess how these patterns relate to the objectives of balanced and inclusive development under SDG 10 and SDG 11.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Three Theoretical Principles

2.2.1. Core–Periphery Structure

2.2.2. Urban Hierarchy System

2.2.3. Urbanization Saturation Effect

2.3. Framework for Population Growth and Decline in Mega-City Region

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Overview of the Study Area

3.2. Data Sources and Processing

3.3. Indicator System and Analytical Methods

3.3.1. Population Growth Indicators

- Absolute Population Change (ΔP)where and are the permanent populations of region i in 2010 and 2020, respectively. It is used mainly for descriptive purposes, whereas comparative assessments rely on relative measures.

- Population Growth Rate (r)where denotes the population growth rate of region i. This indicator expresses the relative intensity of change and facilitates comparison across units with different population sizes and development levels.

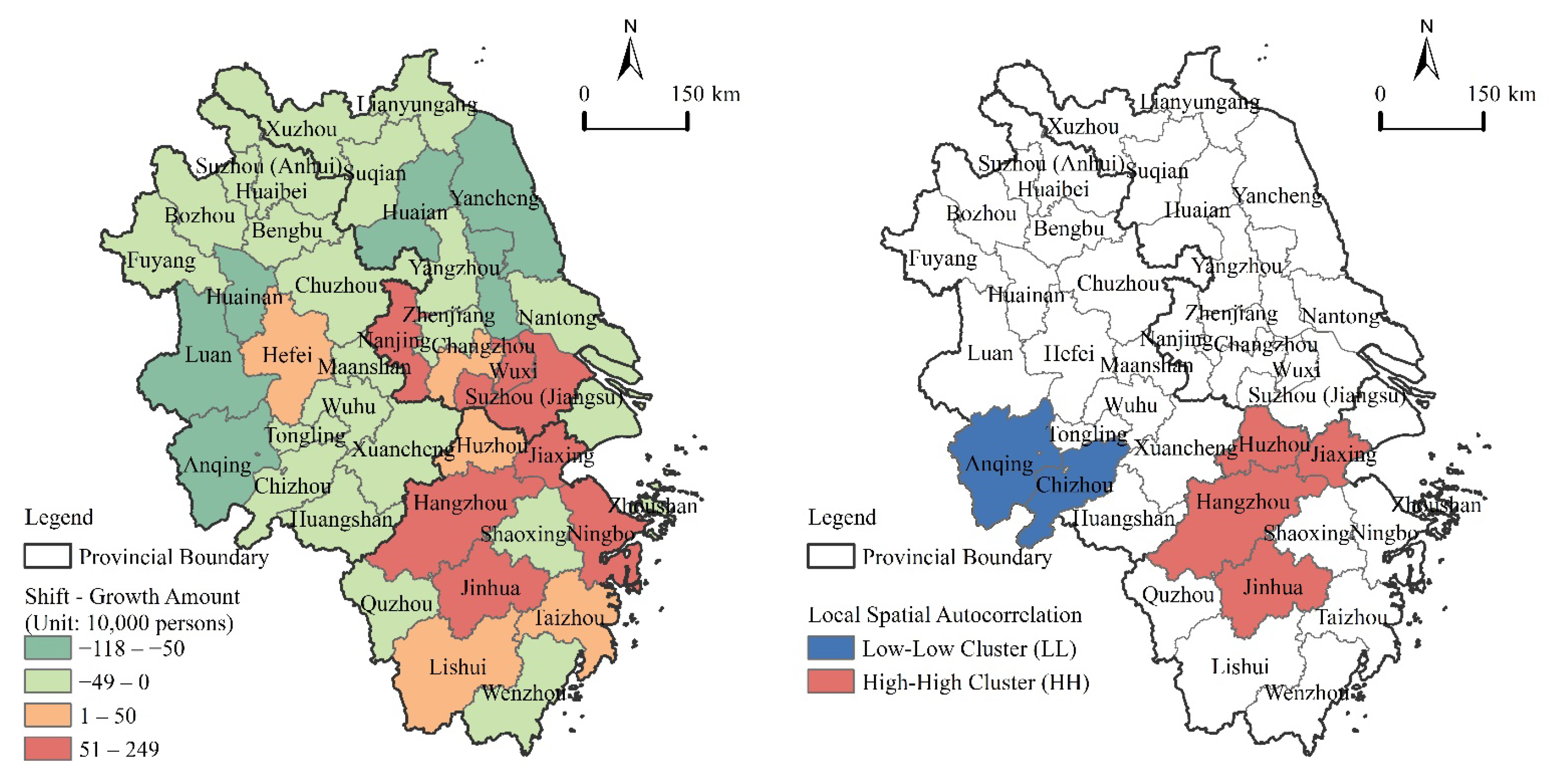

- Shift–Share Analysis (Shifti)where , , and represent the absolute growth, share growth, and shift effect of region i between and , respectively. The share growth denotes the expected increase if region i had grown at the same rate as the whole region, while the shift effect captures the deviation from the average growth—reflecting a region’s relative population advantage or disadvantage.

3.3.2. Spatial Autocorrelation Indicators

- Global Moran’s Iwhere is the number of regions, and are population growth rates, and denotes the spatial weight. A significantly positive I indicates spatial clustering (high–high or low–low), while a negative I suggests spatial dispersion. This provides a global perspective on spatial dependence in population dynamics. In this study, the spatial weight matrix is constructed using a first-order queen contiguity scheme, in which two administrative units are considered neighbors if they share a common boundary or vertex. The matrix is row-standardized, and no distance-based or hierarchical weighting structures are applied.

- Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA)where denotes the local Moran’s I for region i, and is the spatial weight between regions i and j. The LISA statistic identifies local clusters, distinguishing high–high (HH), low–low (LL), high–low (HL), and low–high (LH) patterns. It reveals localized population hotspots and shrinking belts, highlighting the internal heterogeneity of regional systems.

3.3.3. Regional Inequality Indicators

- Coefficient of Variation (CV)where is the standard deviation of the indicator across regions, and is the mean. The CV measures the dispersion of population distribution relative to the mean, offering a simple yet effective representation of inequality.

- Theil Index (T)where T denotes the Theil inequality index, represents the value of the indicator (e.g., population) for region i, is the mean value of the indicator across all regions. The Theil index, derived from information entropy, quantifies the degree of inequality and can be decomposed into within group and between group components, which is suitable for multilevel comparisons across provinces, cities, and counties.

- Hoover Index (H)where and represent the shares of population and land area, respectively. The Hoover index intuitively reflects the degree of spatial concentration versus dispersion, making it a useful indicator for evaluating territorial balance in population allocation.

4. Regional Differentiation of Population Growth and Decline in the YRD

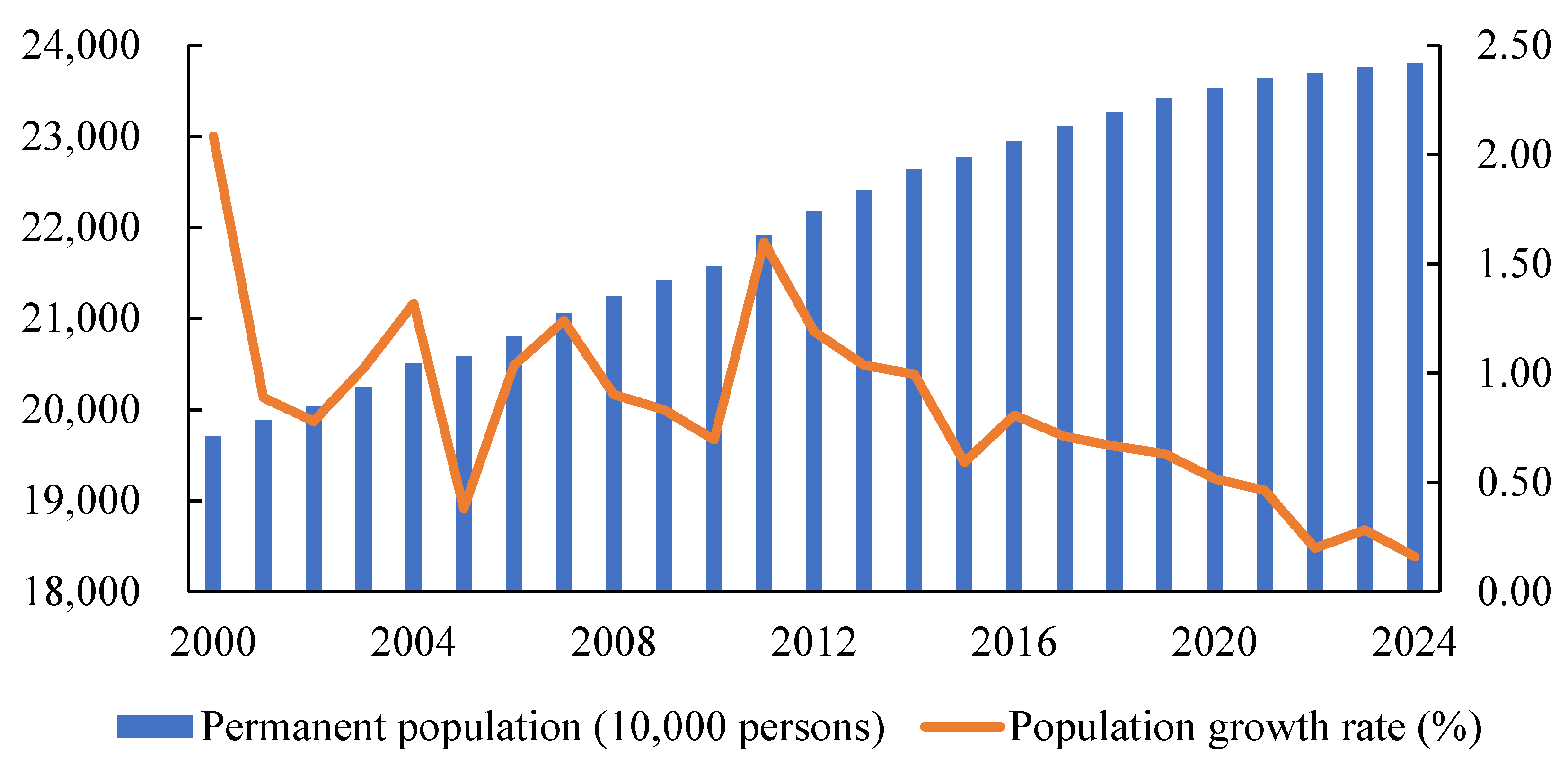

4.1. Population Growth Trends (2000–2024)

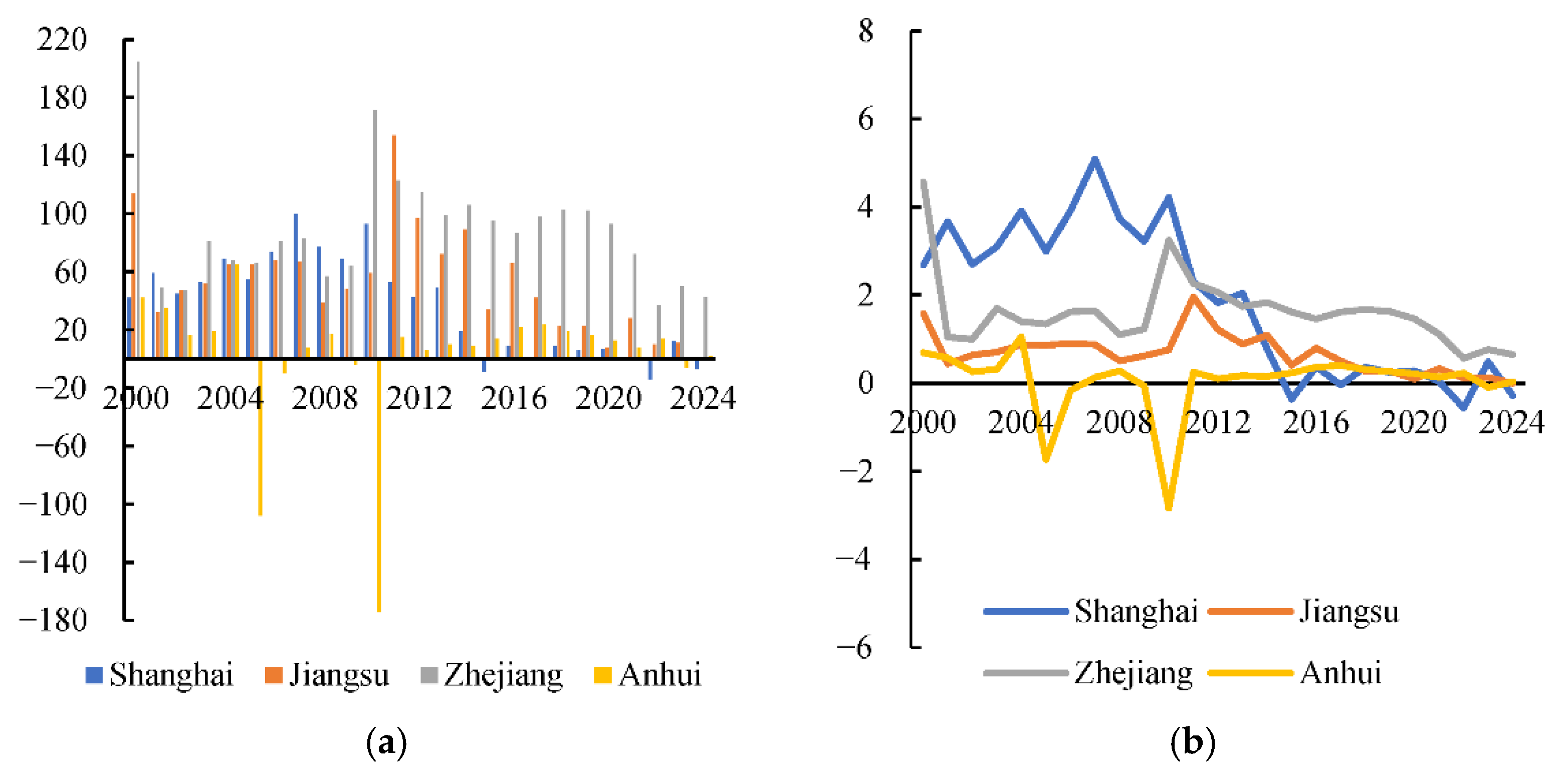

4.1.1. Rapid and Volatile Growth Phase (2000–2011)

4.1.2. Slow-Growth and Decelerating Phase (2012–2024)

4.2. Provincial-Level Population Changes in the YRD

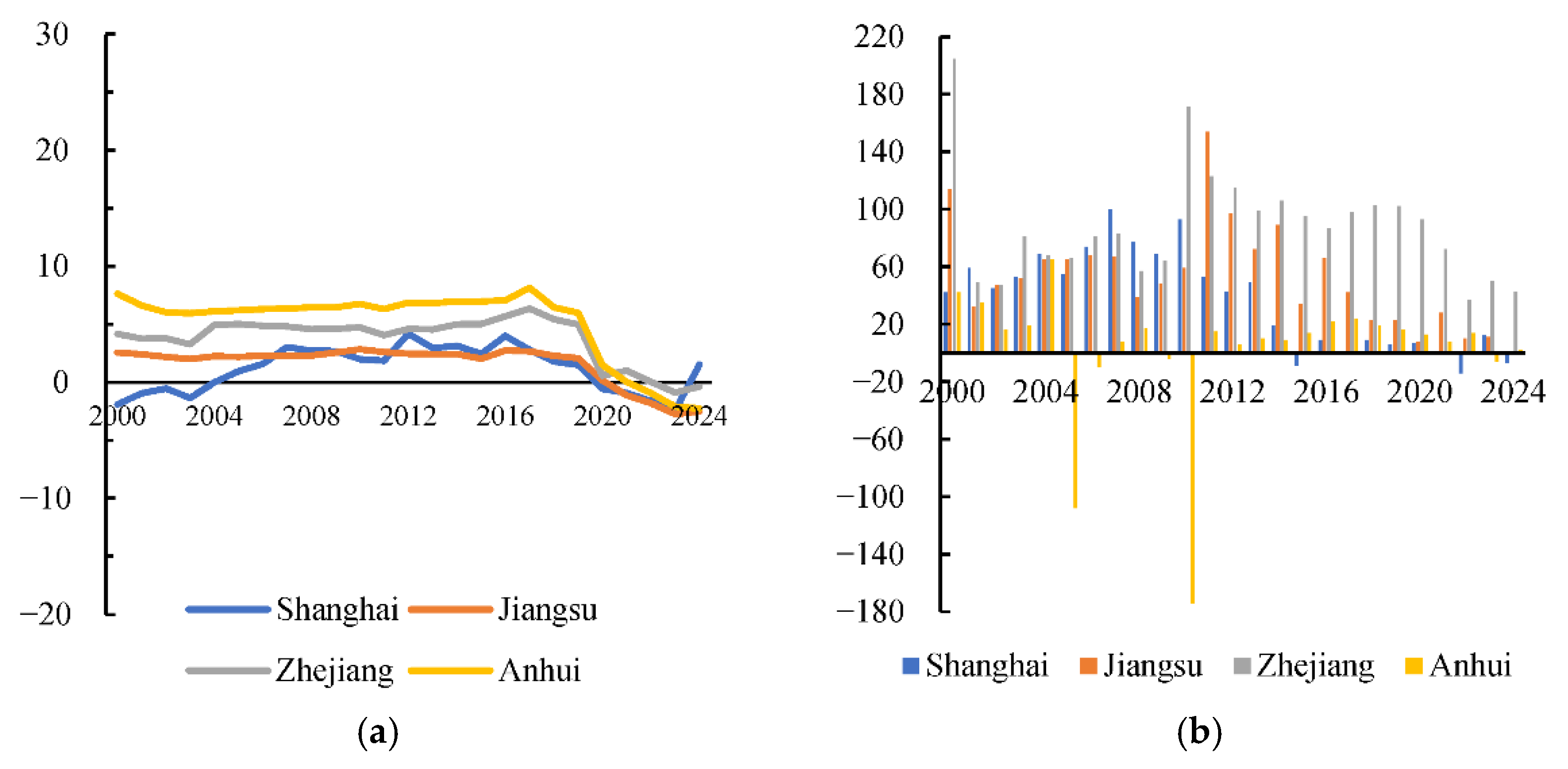

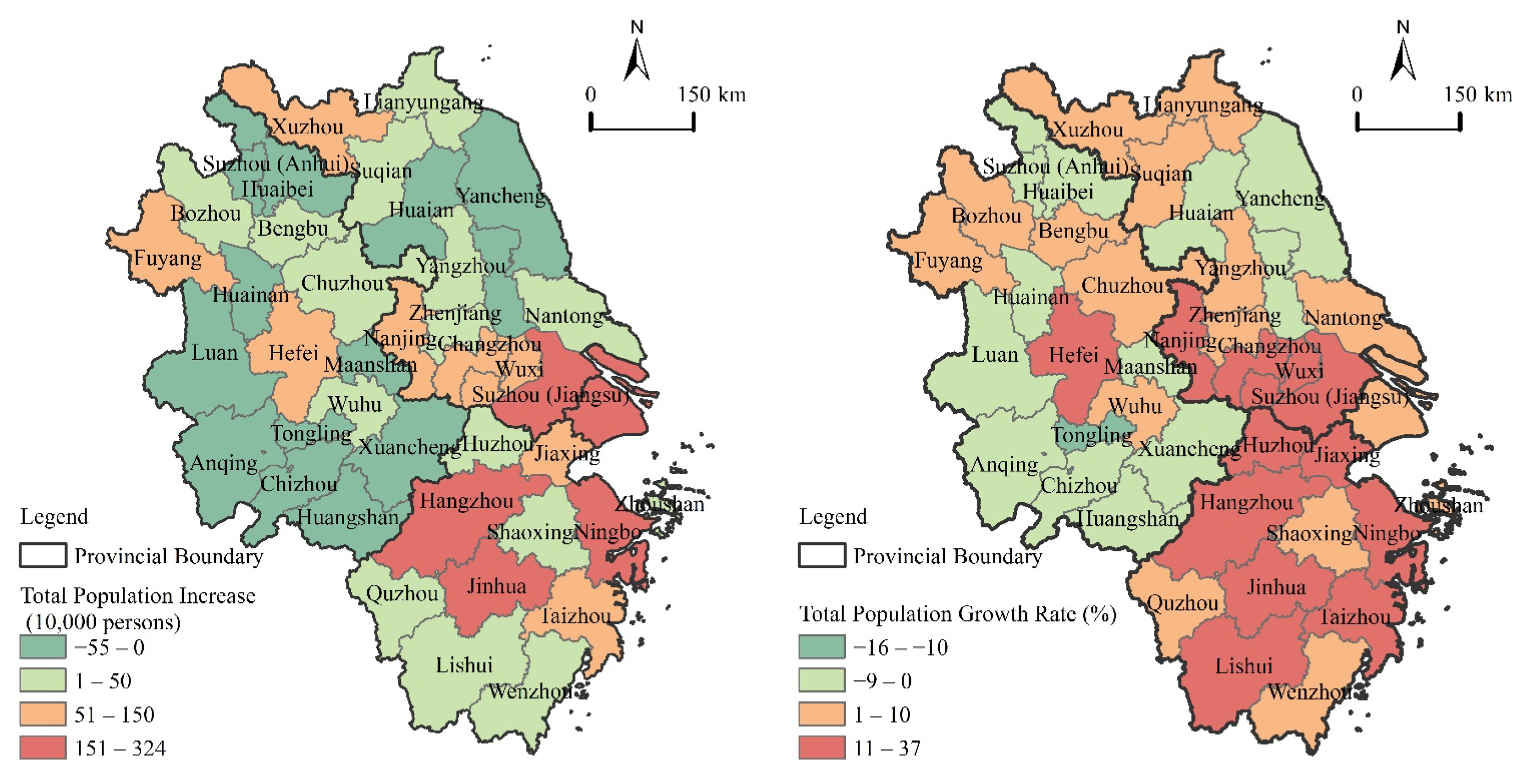

4.3. City-Level Population Redistribution and Spatial Differentiation

4.3.1. Spatial Patterns of Population Increase and Growth Rate

4.3.2. Shift–Share Analysis: Population Redistribution and Core Reinforcement

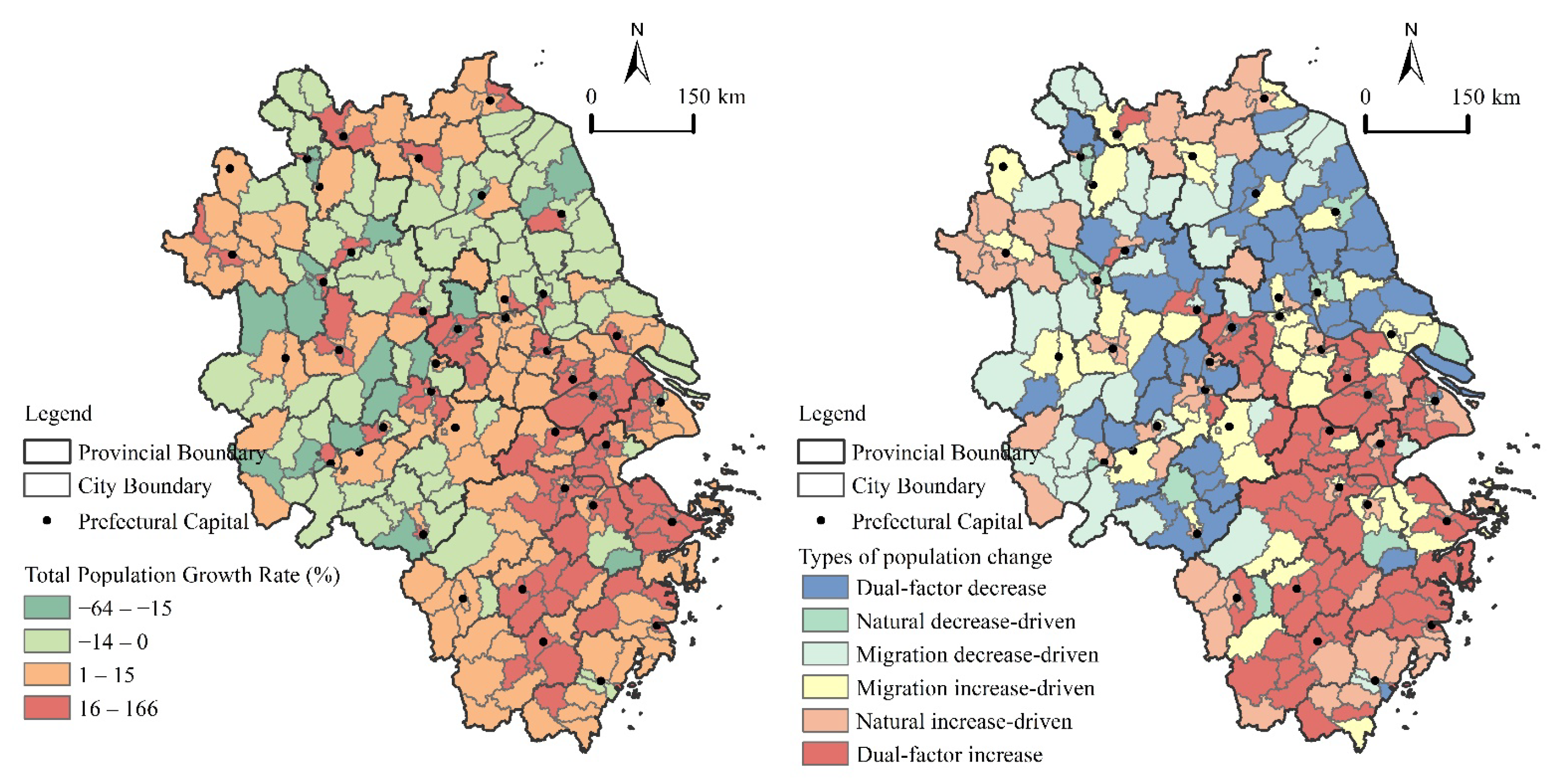

4.4. County-Level Population Growth Analysis in the YRD

4.5. Spatial Inequality Analysis

5. Conclusions and Implications for Sustainable Development

5.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- Population growth has shifted from industrialization-driven surge to quality-oriented stable expansion, with demographic dividend decline and aging marking a structural turn toward sustainability. Spatial polarization intensifies across scales: provincial disparities remain modest, but city- and county-level inequalities widen sharply. Core metropolises (Shanghai, Suzhou, Nanjing, Hangzhou, Hefei) sustain growth as high–high clusters, while peripheral counties in northern Jiangsu and Anhui face stagnation or decline (low–low clusters), reflecting cumulative causation in core–periphery structures.

- (2)

- Higher-tier cities demonstrate stronger demographic resilience via stable mechanical growth, aligning with urban hierarchy theory, while megacities exhibit early saturation signals—slowing migration, central district stabilization—driving growth spillover to secondary cities and suburban hinterlands. Notably, county-level inequality dominates overall imbalance, with intra-provincial disparities (not inter-provincial gaps) becoming the primary driver of demographic unevenness, as peripheral counties and rural townships suffer structural contraction due to limited economic and institutional support.

- (3)

- Migration, though slightly more diffuse, remains concentrated in metropolitan cores, failing to alleviate peripheral shrinkage. This study underscores that under national low-growth conditions, the YRD’s demographic transition reinforces multiscale hierarchical reallocation rather than spatial equilibrium. These findings enrich theoretical understanding of megaregional demographic dynamics and provide normative implications for reconciling efficiency and equity in sustainable urbanization under the SDG framework.

5.2. Implications for Sustainable Development

- (1)

- For saturated core metropolises, policies should shift from population attraction to high-quality, inclusive governance. Prioritize compact urban development, expand affordable housing, and equalize public services (education, healthcare) for registered and migrant residents to mitigate segregation and infrastructure overload. Leverage growth spillover to secondary cities and suburbs via transit integration and industrial relocation, avoiding unsustainable sprawl.

- (2)

- For shrinking peripheral counties (e.g., northern Jiangsu/Anhui), urgent measures are needed to break the downward spiral of population loss, aging, and service withdrawal. Safeguard basic public service thresholds, consolidate essential infrastructure, foster diversified local economies, and enhance physical/digital connectivity to core areas, enabling residents to access opportunities without relocation.

- (3)

- At the regional scale, governance should focus on intra-provincial inequality—strengthening cross-level coordination to rebalance resource allocation between core and peripheral areas. Use multiscale inequality indicators to monitor progress, aligning population dynamics with land use and infrastructure planning. These strategies will reconcile efficiency and equity, guiding the YRD toward spatially just, resilient development consistent with the 2030 Agenda.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| YRD | Yangtze River Delta |

References

- Wolff, M.; Wiechmann, T. Urban Growth and Decline: Europe’s Shrinking Cities in a Comparative Perspective 1990–2010. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2018, 25, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Urbanization Prospects 2018|Population Division. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/news/world-urbanization-prospects-2018 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/hk/en/2030-agenda-sustainable-development (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Kim, S.; Kim, E. Population Decline in Small and Medium-Sized Cities and Spatial Economic Patterns: Spatial Probit Model of South Korea. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2024, 32, 3141–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, L. Demographic Dynamics, Urban Cycles and Economic Downturns: A Long-Term Investigation of a Metropolitan Region in Europe, 1956–2016. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2020, 39, 549–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichter, D.T.; Brown, D.L.; Parisi, D. The Rural–Urban Interface: Rural and Small Town Growth at the Metropolitan Fringe. Popul. Space Place 2021, 27, e2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balandi, J.B.; To Hulu, J.P.P.M.; Sambieni, K.R.; Sikuzani, Y.U.; Bastin, J.-F.; Musavandalo, C.M.; Nguba, T.B.; Molo, J.E.L.; Selemani, T.M.; Mweru, J.-P.M.; et al. Urban Sprawl and Changes in Landscape Patterns: The Case of Kisangani City and Its Periphery (DR Congo). Land 2023, 12, 2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talkhabi, H.; Ghalehteimouri, K.J.; Mehranjani, M.S.; Zanganeh, A.; Karami, T. Spatial and Temporal Population Change in the Tehran Metropolitan Region and Its Consequences on Urban Decline and Sprawl. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 70, 101731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Ma, J.; Sho, K.; Seta, F. Are East Asian “Shrinking Cities” Falling into a Loop? Insights from the Interplay between Population Decline and Metropolitan Concentration in Japan. Cities 2024, 155, 105445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. The Era of Negative Population Growth: Characteristics, Risks, and Coping Strategies. J. Soc. Dev. 2019, 6, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, T.; Jin, G.; Guo, Y. A Comparison of Two Types of Negative Population Growth: Definition, Demographic Implications and Economic Impacts. Popul. Res. 2021, 45, 14–28. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, Z.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Y. An Analysis of Special Factors Influencing China’s Low Fertility Level. Popul. Res. 2025, 49, 52–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, Z.; Jin, G. China’s Negative Population Growth: Characteristics, Challenges, and Responses. Popul. Res. 2023, 47, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, G.; Guo, Y.; Tao, T. The Connotation Evolution, Multi-dimensional Differentiation, and Economic Impact Pathways of Negative Population Growth. Lanzhou Acad. J. 2024, 2, 64–76. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Z.; Mo, H. The Historical Evolution and Urban-Rural Differences of Population Momentum in China. Chin. J. Popul. Sci. 2024, 38, 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Y.; Cao, G. A Structural Analysis and Spatio-temporal Pattern of Regional Population Growth and Decline Differentiation in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2025, 80, 1482–1501. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Peng, R.; Zhuo, Y.; Cao, G. The Evolution of Population Distribution Pattern and Its Influencing Factors in China from 2000 to 2020. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2022, 77, 381–394. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Z. Spatial Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Population Shrinkage in Towns and Villages of Small and Medium-sized Cities in China. Geogr. Res. 2025, 44, 1534–1550. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Su, Y. Spatiotemporal Evolution of Economic Disparities among 23 Cities in Guangdong Province, Hong Kong, and Macau: A Comprehensive Study. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2024, 150, 04023052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zeng, Z.; Xi, Z.; Peng, Z.; Chen, G.; Zhu, X.; Chen, X. Research on Sustainable Urban-Rural Integration Development: Measuring Levels, Influencing Factors, and Exploring Driving Mechanisms-Taking Eight Cities in the Greater Bay Area as Examples. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Sun, W.; Wang, Y.; Xu, S. Evolution, Shift-Share Growth, and Influencing Factors of Population Distribution in the Yangtze River Delta. Prog. Geogr. 2020, 39, 2068–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, Z. Research on the Spatial Evolution Characteristics and Trends of the Yangtze River Delta Region Based on Population Flow. Urban Plan. Forum 2020, 5, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, M.; Meng, X.; Niu, X. Characteristics of Population Element Flow and Spatial Governance Strategies in the Su-Xi-Chang Metropolitan Area. Planners 2022, 38, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, J. Regional Development Policy: A Case Study of Venezuela; M.I.T. Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, J. A General Theory of Polarized Development. In Growth Centers in Regional Economic Development; Hansen, N.M., Ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1972; pp. 82–107. [Google Scholar]

- Christaller, W. Central Places in Southern Germany; Baskin, C.W., Translator; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, B.J.L. Cities as Systems within Systems of Cities. Pap. Reg. Sci. 1964, 13, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, H.W. City Size and National Spatial Strategies in Developing Countries; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Champion, T. Urbanization, Suburbanization, Counterurbanization and Reurbanization. In Handbook of Urban Studies; Paddison, R., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2001; pp. 143–161. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2025; Statistical Bulletin on National Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China in 2024. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202502/t20250228_1958817.html (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- China Statistics Press. Shanghai Statistical Yearbook 2000–2024; China Statistics Press: Shanghai, China, 2000–2024. [Google Scholar]

- China Statistics Press. Jiangsu Statistical Yearbook 2000–2024; China Statistics Press: Nanjing, China, 2000–2024. [Google Scholar]

- China Statistics Press. Zhejiang Statistical Yearbook 2000–2024; China Statistics Press: Hangzhou, China, 2000–2024. [Google Scholar]

- China Statistics Press. Anhui Statistical Yearbook 2000–2024; China Statistics Press: Hefei, China, 2000–2024. [Google Scholar]

- China Statistics Press. Tabulation on the 2010 Population Census of China; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- China Statistics Press. Tabulation on the 2020 Population Census of China; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, D.; Wang, D.; Bai, N.; Qian, W.; Xie, C.; Zhou, Z. From “Migrant Worker Shortage” to “Returning Tide”: Has China’s Lewis Turning Point Arrived? Popul. Res. 2009, 33, 32–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, D.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Jiang, J. Analysis of the Formation Mechanism of Jiaxing City as a “Metropolitan Shadow Area”: A Comparative Study with the Development Difference of Suzhou City. Hum. Geogr. 2014, 29, 66–71. [Google Scholar]

| Region | 2000–2011 | 2011–2020 | 2000–2024 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shanghai | 566.42 | −77.84 | 537.10 |

| Jiangsu | −126.33 | −184.34 | −321.49 |

| Zhejiang | 364.75 | 622.81 | 1018.81 |

| Anhui | −804.84 | −360.63 | −1234.42 |

| Administrative Type | Number of Units | Share of Population (%) | Population Growth Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urban Districts | 144 | 53.3 | 18.44 |

| County-Level Cities | 51 | 20.6 | 5.95 |

| Ordinary Counties | 101 | 26.1 | −1.11 |

| Total | 296 | 100 | 7.76 |

| Level | Year | CV | Theil | Hoover |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provincial | 2010 | 0.411 | 0.070 | 0.138 |

| 2020 | 0.424 | 0.076 | 0.144 | |

| City-level | 2010 | 0.738 | 0.201 | 0.234 |

| 2020 | 0.739 | 0.215 | 0.254 | |

| County-level | 2010 | 0.671 | 0.190 | 0.239 |

| 2020 | 0.722 | 0.209 | 0.244 |

| Year | T (Overall) | TB (Inter-Provincial) | TW (Intra-Provincial) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 0.190 | 0.084 | 0.019 |

| 2020 | 0.209 | 0.071 | 0.024 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qin, X.; Yang, J. Population Growth–Decline Differentiation and Regional Inequality in the Yangtze River Delta: Implications for Sustainable Regional Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11011. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411011

Qin X, Yang J. Population Growth–Decline Differentiation and Regional Inequality in the Yangtze River Delta: Implications for Sustainable Regional Development. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11011. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411011

Chicago/Turabian StyleQin, Xianhong, and Jingchun Yang. 2025. "Population Growth–Decline Differentiation and Regional Inequality in the Yangtze River Delta: Implications for Sustainable Regional Development" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11011. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411011

APA StyleQin, X., & Yang, J. (2025). Population Growth–Decline Differentiation and Regional Inequality in the Yangtze River Delta: Implications for Sustainable Regional Development. Sustainability, 17(24), 11011. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411011