Hydrogen–Electricity Cooperative Mode Switching Mechanism and Optimization Based on Economic Trade-Off Index and Adaptive Threshold

Abstract

1. Introduction

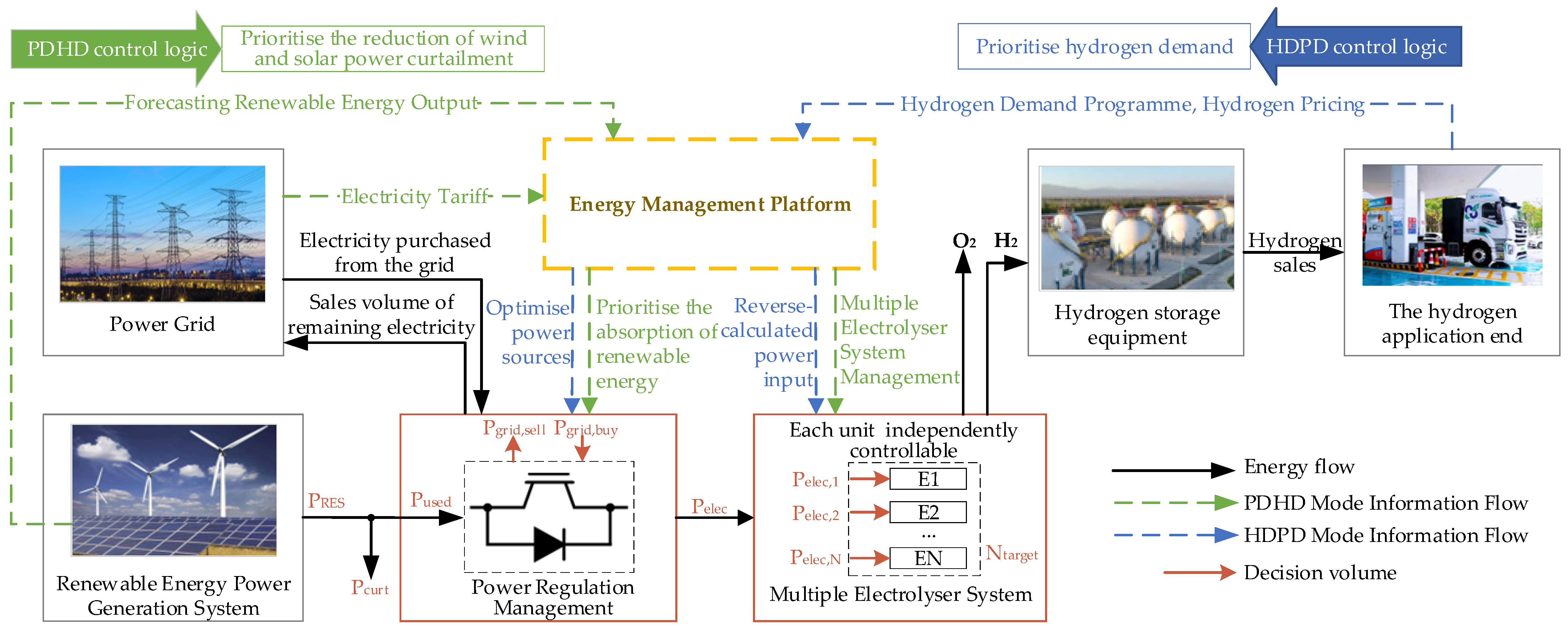

2. System Architecture and Component Modeling

2.1. Core Component Composition

2.2. Core Component Modeling

2.2.1. Renewable Energy System Modeling

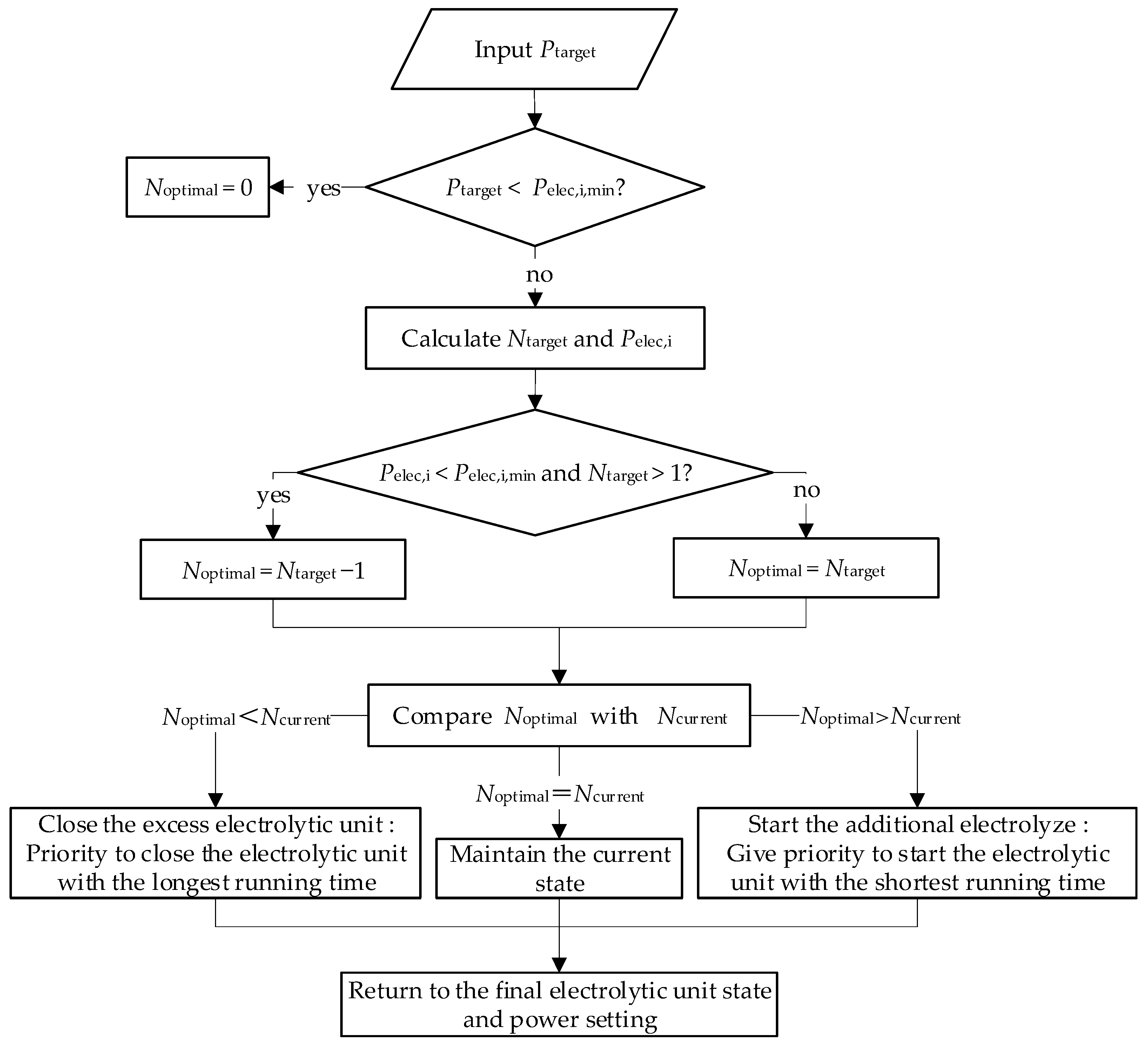

2.2.2. Multiple-Electrolyzer System Modeling

2.2.3. Modeling of Hydrogen Storage Systems

2.2.4. Grid Interaction Modeling

3. Hydrogen–Electricity Synergistic Optimization Decision-Making Strategy

3.1. Mathematical Modeling of Operation Mode

3.1.1. HDPD Mode

3.1.2. PDHP Mode

3.2. Mode Switching Decision Mechanism

3.2.1. HEETI

3.2.2. Dynamic Economic Threshold

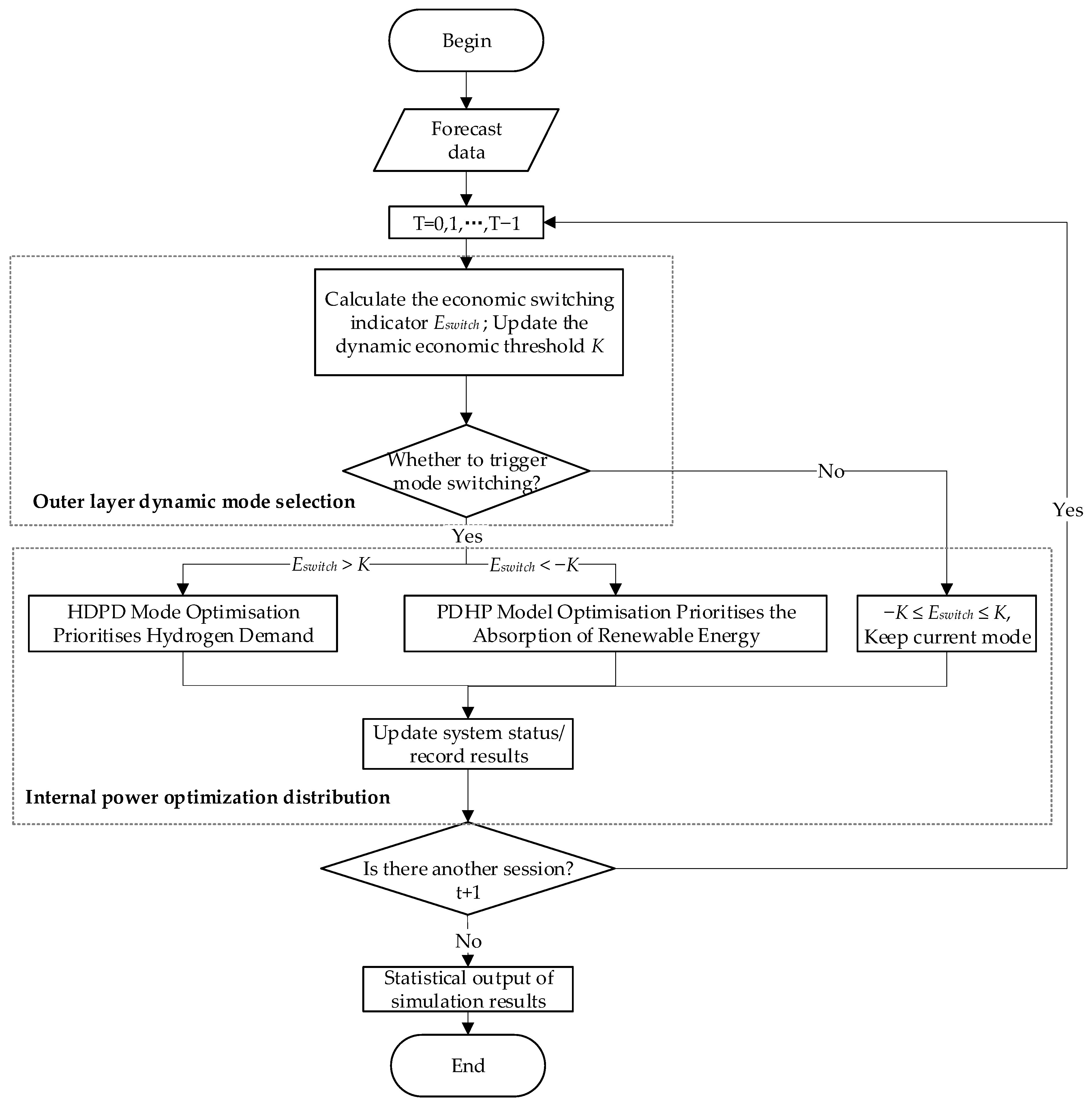

3.3. System Implementation of Bi-Level Optimization Architecture

- Forecast data input: the system receives renewable energy output forecasts, hydrogen demand forecasts, and time-series data for electricity prices and hydrogen prices. The simulation model introduces random disturbance to enhance the authenticity, but it uses a deterministic optimization method; that is, each run generates a set of input data containing randomness and then assumes that the set of data is perfectly predicted for optimization decision. This method cannot quantify the impact of uncertainty on the quality of decision-making because the optimization process assumes that future data is known, but it can show the performance of the system in scenarios containing fluctuations and extreme events.

- Outer-layer mode switching decision: based on HEETI exponential Equation (25) to determine the current economic state combined with the dynamic threshold to trigger mode switching and output the operational mode for the current period (HDPD or PDHP).

- Inner-layer power optimization allocation: based on the operational mode determined by the outer-layer decision, the inner layer employs differentiated algorithms for precise power allocation:In HDPD mode, solve the MILP model of Equations (15)–(19) to ensure hydrogen supply constraints;In PDHP mode, solve the heuristic optimization of Equations (20)–(24) to maximize renewable energy utilization.

- System status updates and logging: update hydrogen storage levels, equipment start/stop status, number of electrolyzer units in operation and their operating modes, cumulative costs, etc. The switching frequency is transmitted back for threshold adjustment in the subsequent period, forming an adaptive closed-loop system.

- Recursive sequence and result output: the recursive process cycles through subsequent time periods, ultimately compiling key metrics for each operational mode, including total costs, hydrogen production volume, hydrogen production costs, renewable energy consumption rate, electricity purchase-to-sale ratio, and carbon emissions reduction.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Simulation Settings

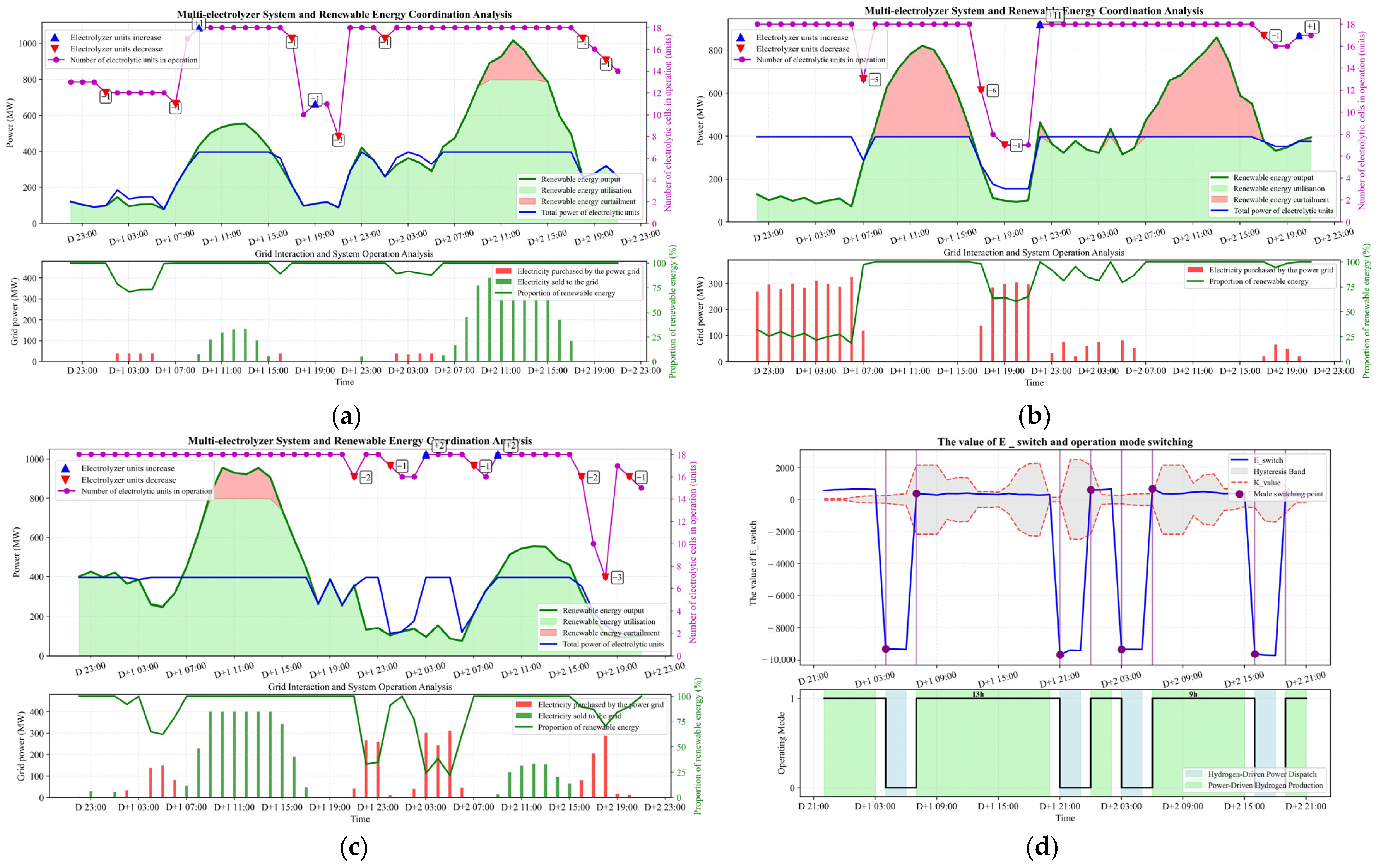

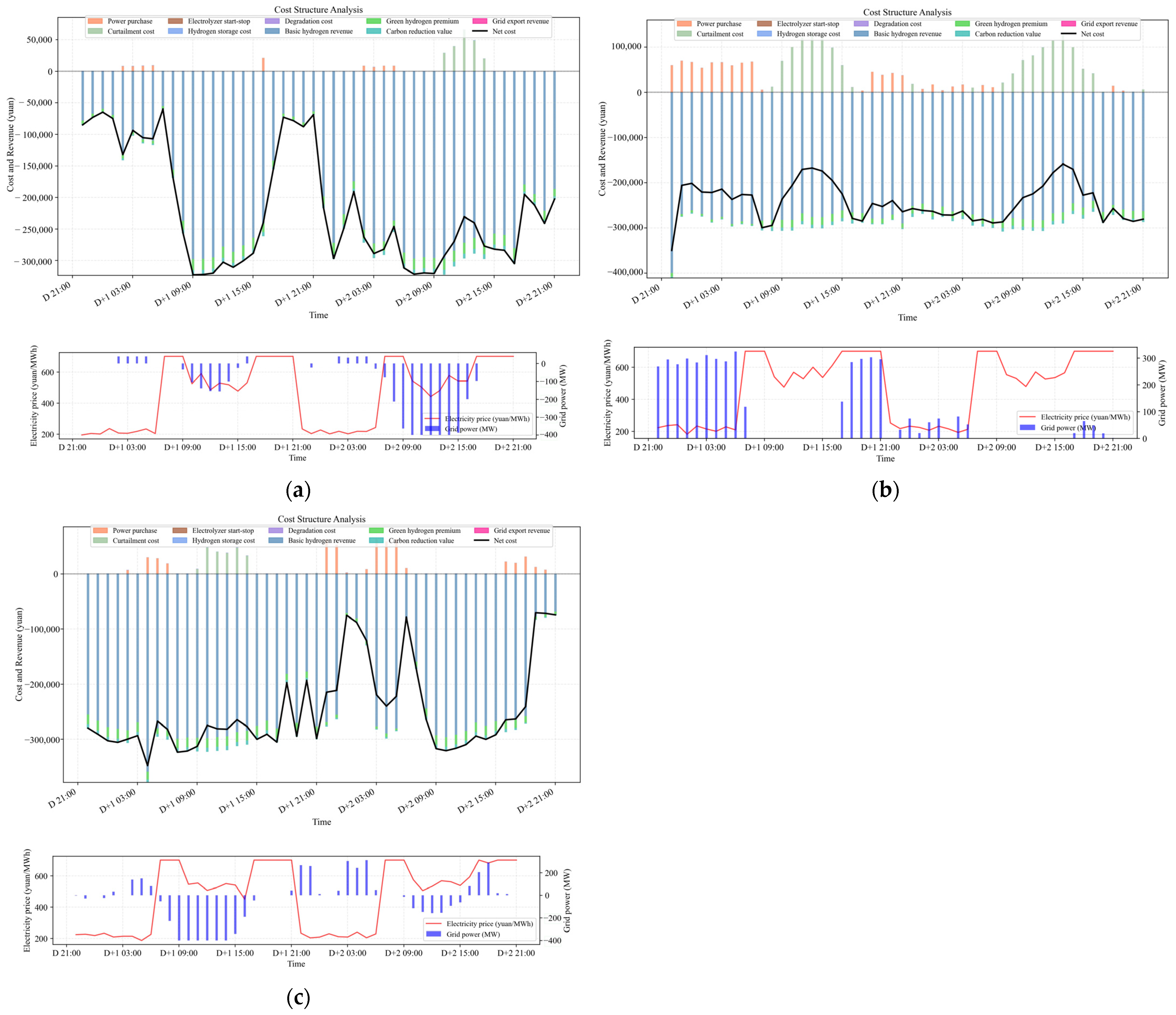

4.2. Results Analysis

4.3. Counterfactual Test Analysis

5. Conclusions

- The PDHP mode achieves the lowest hydrogen production cost of 0.063 USD/kg and the highest renewable energy absorption rate of 96.19%, making it particularly suitable for scenarios prioritizing cost minimization and renewable utilization.

- The HDPD mode maintains the highest hydrogen output of 318 metric tons, thereby ensuring supply stability for applications with stringent hydrogen demand. This supply assurance, however, comes at the expense of a higher levelized cost of hydrogen, which reaches 0.38 USD/kg.

- The proposed dynamic switching mechanism demonstrates superior comprehensive performance by achieving an optimal multi-objective balance: 16.3% cost reduction compared to HDPD, and 14.4% hydrogen output increase compared to PDHP, while maintaining 96.34% renewable energy utilization and 0.25 USD/kg LCOH.

- Counterfactual validation confirms the effectiveness of the decision-making mechanism, with all switching points yielding positive net gains, demonstrating that the HEETI index reliably captures market signals for economic optimization. Furthermore, policy factors, such as green hydrogen premiums and carbon reduction value, contributed marginally within the current model. Future refinement should focus on core economic and operational variables to enhance the model’s practicality and interpretability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HDPD | Hydrogen-driven power dispatch |

| PDHP | Power-driven hydrogen production |

| HEETI | Hydrogen–electricity economic trade-off index |

References

- Li, J.L.; Li, G.H.; Liang, D.X.; Ma, S.L. Review and prospect of renewable energy hydrogen production technology under “Dual-Carbon Target”. Distrib. Energy 2021, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.L.; Song, B.S.; Wang, H.; Li, H.; Lin, D.J. Application scenarios, development status and challenges of hydrogen-electricity coupling. China Resour. Compr. Util. 2024, 42, 129–133. [Google Scholar]

- Alnuwaiser, A.; Rabia, M.; Elsayed, A.M. Bismuthyl chloride/poly(m-toluidine) nanocomposite seeded on poly-1H-pyrrole photocathode for green hydrogen generation. Open Phys. 2024, 22, 20240111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttler, A.; Spliethoff, H. Current status of water electrolysis for energy storage, grid balancing and sector coupling via power-to-gas and power-to-liquids: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 2440–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.S.; Zhang, H.Q.; Jiang, H.; Liu, G.J.; Liu, W.Z. Configuration and optimal dispatch of renewable energy electrolytic hydrogen production system. Water Power 2025, 51, 105–112+118. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X.; Feng, T.; He, G.L.; Hu, T.; Liu, Y.j. Research progress of the influence of wind power and photovoltaic of power fluctuation on water electrolyzer for hydrogen production. Energy Storage Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 3275–3284. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.X.; Dong, Y.R.; Sun, X.; Tang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S.Y.; Tan, J.P. Integrated energy management platform for renewable energy hydrogen production. South. Energy Constr. 2022, 9, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Meng, X.; Nie, G.; Li, B.; Yang, H.; He, M. Optimization of hydrogen production in multi-electrolyzer systems: A novel control strategy for enhanced renewable energy utilization and electrolyzer lifespan. Appl. Energy 2024, 376, 124299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, P.W.; Liu, Q.H.; Pan, A.; Wang, J.Y.; Fu, X.G.; Yang, S.Y.; Yu, H. Wind-powered hydrogen production system considering uncertainty: A multi-time scale operation strategy. CIESC J. 2025, 76, 2743–2754. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, T.J.; Wan, Z.; Wang, J.J.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, D.F. Day-ahead output plan of hydrogen production system considering electrolyzer start-stop characteristics. Electr. Power 2022, 55, 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Peng, H.W.; Zhang, J.F.; Chen, P.; Ruan, J.; Li, B.; Wang, Y. Optimized demand-side day-ahead generation scheduling model for a wind–photovoltaic–energy storage hydrogen production system. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 43036–43044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.; Huang, K.; Yang, C.; Xu, J. Day-ahead scheduling of microgrid with hydrogen energy considering economic and environmental objectives. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 1303–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tian, R.; Zheng, S.; Lu, C.; Zhou, S. Multi-objective optimal scheduling of islands considering offshore hydrogen production. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, M.; Alanazi, A.; Alruwaili, M. Optimal stochastic scheduling of a hybrid photovoltaic/hydrogen storage-based fuel cell system in distribution networks using dynamic point sampling and adaptive weighting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 180, 151680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aatabe, M.; Jenkal, W.; Mosaad, M.I.; Hussien, S.A. Stochastic control for sustainable hydrogen generation in standalone PV–battery–PEM electrolyzer systems. Energies 2025, 18, 3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Wang, X.; Hua, Q.; Sun, L. Deep reinforcement learning based energy management of a hybrid electricity-heat-hydrogen energy system with demand response. Energy 2024, 305, 131874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.R.; Zhao, X.L.; Zhang, R.D. Business model analysis of hydrogen integrated utilization stations under new power system. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2024, 44, 183–191. [Google Scholar]

- Glenk, G.; Reichelstein, S. Economics of converting renewable power to hydrogen. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, M.; Yan, Y.L.; Xie, Y.B.; Zhang, J.; Hou, H.; Xie, C.J. Multi-dimensional business operation model and development strategy for electricity-hydrogen complementary synergy system. South. Energy Constr. 2025, 12, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaner, M.R.; Atwater, H.A.; Lewis, N.S.; McFarland, E.W. A comparative technoeconomic analysis of renewable hydrogen production using solar energy. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 2354–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, D.; Zhang, X.; Bauer, C.; Patel, M.K. An integrated techno-economic and life cycle environmental assessment of power-to-gas systems. Appl. Energy 2017, 193, 440–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Deng, Y.; Li, C.; Yi, D.; Liu, Y.; Hu, B.; Shao, C. Optimized operation of integrated electricity–HCNG systems with distributed hydrogen injecting. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2024, 18, 2897–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.T.; Ge, Y.Y.; Yao, H.Y.; Yuan, T.J. Operation control strategy of hydrogen production electrolyzers based on particle swarm optimization. Therm. Power Gener. 2023, 52, 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.L.; Nian, H.; Zhao, J.Y.; Fan, C.X.; Zhou, J.; Shi, S.C. Energy management optimization for renewable hydrogen production with multiple electrolyzers. Electr. Power Eng. Technol. 2024, 43, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; François, B. Energy management and power control of a hybrid active wind generator for distributed power generation and grid integration. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2011, 58, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, P.; Lin, H.; Zhou, X.; Zou, Y.; Li, Y.; Yan, G.; Duan, X.; Cai, J. Control strategies for multi-electrolyzer alkaline hydrogen generation systems improving renewable energy utilization and electrolyzer lifespan. Renew. Energy 2025, 253, 123628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.X.; Wang, S.L.; Miao, J.; Xiang, B. Technical economy discussion and cost analysis of renewable energy hydrogen production. Sino-Glob. Energy 2023, 28, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.T.; Zhou, J.H.; Zhang, R.Z.; Wang, L.J.; Xu, G. Optimal strategy for alkaline electrolyzer clusters in wind-solar hydrogen production considering energy consumption characteristics. Chem. Ind. Eng. Prog. 2024, 43, 6119–6128. [Google Scholar]

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Green Hydrogen Cost Reduction: Scaling Up Electrolysers to Meet the 1.5 °C Climate Goal; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dongfang Securities. Hydrogen Energy Industry Special Research III: Hydrogen Production Electrolyzer; Dongfang Securities: Shanghai, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, S. Overview of electrolyser and hydrogen production power supply from industrial perspective. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 1048–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhsoos, A.; Kandidayeni, M.; Pollet, G.B.; Boulon, L. Proton exchange membrane water electrolyzers degradation models review: Implications for power allocation and energy management. J. Power Sources 2025, 655, 238003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozzi, E.; Grimaldi, A.; Minuto, F.D.; Lanzini, A. Model complexity and optimization trade-offs in the design and scheduling of hybrid hydrogen-battery systems. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 344, 120306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, S.; Alsenani, R.T.; Alrumayh, O.; Altamimi, A.; Kilic, H. Adaptive hydrogen buffering for enhanced flexibility in constrained transmission grids with integrated renewable energy system. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 144, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökay, B.; Alper, Y.; Recep, Ç. A new Fuzzy & Wavelet-based adaptive thresholding method for detecting PQDs in a hydrogen and solar-energy powered EV charging station. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 6855–6870. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, P.; Chen, Z.; Tang, W.; Liu, Z.; He, B. An adaptive prediction method for ultra-short-term generation power of power system based on the improved long- and short-term memory network of sparrow algorithm. Energy Inform. 2025, 8, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Wenjin, Z.; Qi, L.; Yu, Z.; Han, Y.; Bai, Z. Capacity configuration optimization for green hydrogen generation driven by solar-wind hybrid power based on comprehensive performance criteria. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1256463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Description | Symbol | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time period index (h) | Grid emission factor (t CO2/MWh) | ||

| Electrolyzer unit index (i = 1, 2, …, N) | Grid purchase cost (USD) | ||

| Total renewable output (MW) | Curtailment penalty (USD) | ||

| Actual utilized renewable power (MW) | Startup cost (USD) | ||

| Curtailed power (MW) | Storage cost (USD) | ||

| Total number of electrolyzer units | Demand gap penalty (USD) | ||

| Total electrolyzer power (MW) | Power stability cost (USD) | ||

| Power consumption of unit (MW) | Hydrogen sales revenue (USD) | ||

| Rated power of unit i (MW) | Green H2 premium (USD) | ||

| Minimum power of unit i (MW) | Grid sales revenue (USD) | ||

| Operating status of unit (0 = off, 1 = on) | Carbon reduction value (USD) | ||

| Startup command for unit (0/1) | HEETI index (USD) | ||

| Maximum ramp rate of unit (MW/h) | Basic economic comparison (USD/MWh) | ||

| Minimum runtime requirement (h) | Storage state factor (USD) | ||

| Electrolysis efficiency of unit (kg H2/MWh) | Renewable consumption factor (USD) | ||

| Initial efficiency (kg H2/MWh) | Carbon reduction factor (USD) | ||

| Number of start–stop cycles | Price trend factor (USD) | ||

| Degradation coefficients | Switching cost (USD) | ||

| Hydrogen production (kg) | Adaptive threshold | ||

| Hydrogen storage level (kg) | Threshold coefficients | ||

| Hydrogen demand (kg) | Storage/utilization correction factors | ||

| Maximum storage capacity (kg) | Forecast adjustment coefficient | ||

| Minimum storage capacity (kg) | Renewable power ratio | ||

| Power purchased from grid (MW) | Target number of active units | ||

| Power sold to grid (MW) | Calculated optimum number of operating electrolytic units | ||

| Grid connection capacity (MW) | Number of electrolytic units currently in operation | ||

| Binary variables for buy/sell status | Target electrolyzer power (MW) | ||

| Grid ramp rate limit (MW/h) | HDPD objective (minimize cost) (USD) | ||

| Electricity purchase price (USD/MWh) | PDHP objective (maximize revenue) (USD) | ||

| Hydrogen price (USD/kg) | Levelized cost of hydrogen (USD/kg) | ||

| Time step duration (h) | Renewable utilization rate (%) | ||

| Carbon price (USD/t CO2) | Curtailment rate (%) | ||

| Conventional H2 emissions (t CO2/t H2) | Total CO2 reduction (kg) |

| Symbol | Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of units | 18 | — | |

| Unit rated power | 22.0 | MW | |

| Unit minimum power | 6.6 | MW | |

| Maximum ramp rate | 2.0 | MW/h | |

| Minimum runtime | 3.0 | h | |

| Initial efficiency | 18.0 | kg H2/MWh | |

| Startup cost | 1028 | USD/event | |

| Maximum capacity | 61,400 | kg | |

| Minimum capacity | 6140 | kg | |

| Unit storage cost | 0.0085 | USD/(kg·h) |

| Aspect | HDPD | PDHP |

|---|---|---|

| Primary objective | Minimize total cost while satisfying hydrogen demand. | Maximize net revenue while maximizing renewable utilization. |

| Optimization method | Mixed-integer linear programming (MILP). | Heuristic allocation with forecasting. |

| Decision priority | 1. Meet the basic hydrogen demand; 2. Minimize grid purchase; 3. Balance equipment wear. | 1. Maximize renewable absorption; 2. Arbitrage grid sales; 3. Adjust H2 output dynamically. |

| Hard constraint | (Equation (16)). | (Equation (21)). |

| Renewable priority | Use renewables first (Equations (18) and (19)); buy grid if insufficient. | Absorb all available renewables; sell surplus. |

| Electrolyzer dispatch | from demand; select units. | forecast (Equations (22) and (23)). |

| Factor | Symbol | Economic Meaning | Direction | Formula |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic economic comparison | Revenue comparison: H2 sales versus grid sales per MWh | ± | Equation (26) | |

| Hydrogen storage state | Shortage risk penalty: low storage level prompts shift to HDPD | ± | ||

| Renewable consumption | periods | high) | (Equation (27)) | |

| Carbon reduction value | Monetized CO2 abatement via carbon pricing | + | Equation (28) | |

| Price trend | Expected future price movements (suppress premature switch) | ± | Equation (29) | |

| Switching cost | Equipment wear and mode change penalty | − | Equations (30)–(32) |

| Symbol | Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connection capacity | 400 | MW | |

| Ramp rate limit | 80 | MW/h | |

| Electricity purchase price | 21–98 | USD/MWh | |

| Hydrogen selling price | 5.2–6.3 | USD/kg | |

| Carbon trading price | 14 | USD/ton CO2 | |

| Grid emission factor | 0.6 | Ton CO2/MWh | |

| Conventional H2 emissions | 10.0 | Ton CO2/ton H2 |

| Cost Component | HDPD | PDHP | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| weight | 42.2 | 63.4 | USD/MWh |

| weight | 169.0 | 112.7 | USD/kg |

| Renewable tracking penalty | — | 70.4 | USD/MWh |

| Mode | PDHP | HDPD | The Method Proposed in This Paper | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | ||||

| Total cost (USD 104) | −165.13 | −156.93 | −182.54 | |

| Hydrogen production (103 kg) | 35.49 | 44.79 | 40.62 | |

| LCOH (USD/kg) | 0.06 | 0.38 | 0.25 | |

| Renewable energy consumption rate (%) | 13.57 | 10.35 | 13.55 | |

| Green hydrogen ratio (%) | 13.73 | 11.45 | 12.32 | |

| Carbon emission reduction (106 kg CO2) | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.46 | |

| Decision Point | Time | The Original Decision | Counterfactual Decision | Opportunity Cost (USD 104) | Opportunity Cost (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | D 23:01 | HDPD | PDHP | −3.41 | −1.9 |

| 2 | D + 1 02:01 | PDHP | HDPD | −3.81 | −2.1 |

| 3 | D + 1 05:01 | HDPD | PDHP | −3.62 | −2.0 |

| 4 | D + 1 07:01 | PDHP | HDPD | −1.03 | −0.6 |

| 5 | D + 1 21:01 | HDPD | PDHP | −1.59 | −0.9 |

| 6 | D + 2 00:01 | PDHP | HDPD | −0.25 | −0.1 |

| 7 | D + 2 03:01 | HDPD | PDHP | −0.69 | −0.4 |

| 8 | D + 2 06:01 | PDHP | HDPD | −1.66 | −0.9 |

| 9 | D + 2 21:01 | PDHP | HDPD | −1.33 | −0.7 |

| Indicator | Original Decision (PDHP) | Counterfactual (HDPD) |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen production (103 kg) | 290.3 | 283.9 |

| Basic hydrogen income (USD 104) | 185.19 | 181.02 |

| Green hydrogen premium (USD 104) | 8.93 | 8.94 |

| Carbon emission reduction value (USD 104) | 3.26 | 3.25 |

| Basic operating costs (USD 104) | 6.91 | 5.86 |

| Renewable energy consumption (MW) | 18,943.52 | 18,934.28 |

| Carbon emissions (kg) | 1116 | 913 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, P.; Li, J.; Du, S.; Wang, Q. Hydrogen–Electricity Cooperative Mode Switching Mechanism and Optimization Based on Economic Trade-Off Index and Adaptive Threshold. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10987. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410987

Zhang P, Li J, Du S, Wang Q. Hydrogen–Electricity Cooperative Mode Switching Mechanism and Optimization Based on Economic Trade-Off Index and Adaptive Threshold. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):10987. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410987

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Panhong, Jiaman Li, Sheng Du, and Qingyi Wang. 2025. "Hydrogen–Electricity Cooperative Mode Switching Mechanism and Optimization Based on Economic Trade-Off Index and Adaptive Threshold" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 10987. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410987

APA StyleZhang, P., Li, J., Du, S., & Wang, Q. (2025). Hydrogen–Electricity Cooperative Mode Switching Mechanism and Optimization Based on Economic Trade-Off Index and Adaptive Threshold. Sustainability, 17(24), 10987. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410987