Abstract

Forests are crucial for achieving carbon neutrality and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This study contributes to SDG 13 (Climate Action) and SDG 15 (Life on Land) by constructing a comprehensive evaluation system for high-quality forestry development (HQDF), integrating economic efficiency, ecological functions, and social benefits. Using provincial panel data for China from 2010 to 2023 and applying two-way fixed effects, panel quantile regression, and instrumental-variable methods, we examine the catalytic role of green finance. The results show that green finance significantly promotes HQDF and displays an inverted U-shaped effect over the development cycle. Regional heterogeneity is marked: the strongest effects appear in western and southern China, moderate effects in central regions, and negative effects in some eastern and northern provinces. Among specific instruments, green investment and green bonds exert the largest positive impacts, followed by green insurance and fiscal funds, while green credit plays an important role at particular stages. These findings provide evidence from a major emerging economy and offer practical guidance for optimizing forestry-related green finance strategies worldwide.

1. Introduction

Climate change and the pursuit of carbon neutrality have become critical global challenges [1,2]. Forests, as Earth’s primary terrestrial carbon reservoir, are central to carbon sequestration and climate mitigation [3,4]. However, the forestry sector is constrained by long investment cycles, high exposure to natural disasters, and chronic capital shortages. The World Bank and FAO identify these factors as core obstacles to sustainable forest management [5,6].

Green finance has emerged as a key instrument for developing a sustainable forest economy. It channels financial resources into eco-friendly activities and aims to align economic growth with ecological conservation through tools such as green bonds and sustainable investment mechanisms [7]. From the G20 Green Finance Reports to the UNEP FI principles, the international community has been experimenting with models that support forest protection [8,9]. Understanding how green finance can drive forestry transformation—by enhancing ecological outcomes (carbon sequestration, biodiversity) and socio-economic outcomes (community welfare, green industries)—has therefore become an important academic and policy concern.

International experience illustrates the diversity of green finance applications in forestry. Brazil’s Amazon Fund channels multilateral capital into forest governance through performance-based payments [10]. Kenya’s blended-finance schemes combine public climate funds with private investment for reforestation [11]. In Scandinavia, green bonds help support biodiversity-friendly timber value chains [12]. These cases highlight how institutional design and local conditions shape both the deployment and the effectiveness of green finance.

China offers a particularly valuable case. It is the world’s leading afforestation country and is committed to ambitious “dual-carbon” targets—peaking carbon emissions by 2030 and achieving carbon neutrality by 2060. It has also developed a comprehensive green-finance policy framework and provides rich provincial panel data for empirical analysis. Large regional differences in economic structure, financial depth, and forestry endowments create an ideal setting for examining heterogeneous impacts. Against this backdrop, three questions arise: How does green finance promote China’s high-quality forestry development (HQDF)? Through which mechanisms does this effect operate? What insights can China’s experience offer for global sustainable-forestry strategies?

The existing literature reveals several important gaps. Studies have shown that green credit can help conserve rainforests [13,14] and that European green bonds support sustainable forest management [15,16]. However, most of this work focuses on specific instruments or individual regions. Systematic cross-regional analyses remain rare. International frameworks such as sustainable forest management (SFM), forest landscape restoration (FLR), and nature-based solutions (NbS) stress the need to balance ecological, social, and economic objectives, but they often lack operational indicators and empirical testing.

Research on “high-quality development” has mainly concentrated on the macroeconomy [17,18,19,20,21]. Applications to forestry are still limited, despite emerging work on manufacturing [22] and agriculture [23]. Mlachila et al. (2017) conceptualize development quality as going beyond growth rates [24]. Jin (2018) and Guo et al. (2024) operationalize the notion of “innovation, coordination, green, openness, and sharing,” [25,26] while Yang and Shao (2018) emphasize industrial linkages [27]. Building on this literature, we define HQDF as a process of structural upgrading and coordinated expansion that maintains ecosystem stability. It is innovation-driven, openness-supported, green-oriented, and benefit-sharing. Two main gaps persist: first, there is insufficient quantitative evidence on how green finance affects HQDF, including its mechanisms (such as R&D-driven innovation and the easing of financing constraints) and dynamic effects over time; second, there is a lack of systematic research that combines multi-dimensional HQDF indicators with explicit mechanism tests and careful treatment of endogeneity.

This study addresses these gaps in several ways. (I) We construct a new HQDF evaluation system that integrates China’s “new development philosophy” with international forestry frameworks, using provincial panel data. (II) We apply rigorous econometric methods, including a two-way fixed-effects model, panel quantile regression, and an innovative instrumental variable based on topographic variation across regions, to identify causal impacts. (III) We test three key transmission channels—environmentally induced R&D (ER&D), green technological innovation, and the alleviation of financing constraints. (IV) We reveal that the marginal impact of green finance on HQDF follows an inverted U-shaped trajectory across development stages. (V) We place China’s experience in a comparative perspective by relating the results to cases in Brazil, Kenya, Scandinavia, and North America, thereby deriving lessons for global forestry-finance strategies.

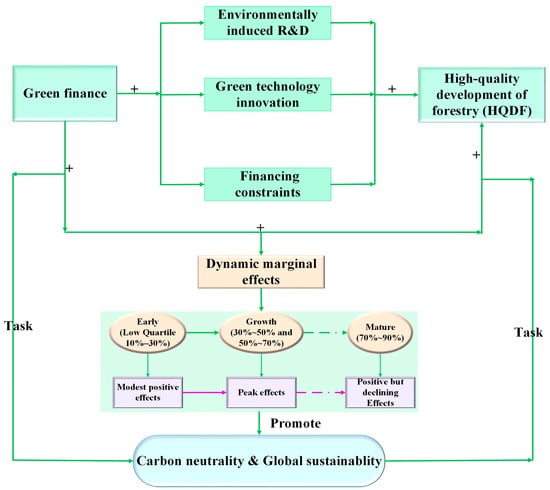

The theoretical framework of this paper is presented in Figure 1. It illustrates how green finance catalyzes HQDF in China through environmental induced R&D, green technology innovation, and the easing of financing constraints. The framework also reflects how the marginal impact of green finance varies across contexts and forestry development stages, and how HQDF contributes to carbon neutrality and the achievement of global sustainability goals.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework illustrating how green finance catalyzes the high-quality development of forestry (HQDF) in China through three primary mechanisms—environmental R&D, green technology innovation, and financing constraint alleviation. (The marginal impact of green finance varies by context and forestry stages, reflecting sector-specific dynamics in sustainable forestry practices. Ultimately, HQDF contributes to carbon neutrality and the achievement of global sustainability goals).

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 develops the research hypotheses. Section 3 describes the methodology and data. Section 4 reports and discusses the empirical results. Section 5 presents the main conclusions and policy implications and suggests avenues for future research.

2. Research Hypotheses

Capital allocation theory postulates balanced fund allocation across sectors, yet traditional models persist in unidimensional economic metrics; combining it with the theory of environmental externalities and the theory of sustainable development can help form a multi-dimensional analytical perspective that takes into account economy, ecology, and society. As an important tool to guide capital towards environmentally friendly activities, green finance, on one hand, shares commonalities with traditional finance in supporting economic entities with funding needs, and on the other hand, differs significantly from traditional finance in core support standards: traditional finance is centered around economic returns, while green finance embeds corporate social responsibility in the decision-making process and considers environmental and social risks [28,29,30]. Therefore, analyzing green finance’s role in forestry development requires integrating economic, ecological, social, and institutional dimensions into the system; this comprehensive approach clarifies how capital allocation logic reshapes forestry transformation.

On this basis, refining the EKC framework is essential. The traditional EKC centers on the inverted U between production–consumption patterns and ecological degradation. By introducing green finance into this theoretical framework, it helps to understand the phased changes in the economic-environment relationship from the perspective of regulatory variables. Following environmental and resource economics principles, green finance improves forestry capital allocation efficiency while mitigating funding gaps for high-quality projects through addressing information asymmetry and incomplete valuation of environmental externalities. This mechanism aligns with capital efficiency principles and fits EKC’s nonlinear trajectory where economic output and environmental quality follow an inverted U pattern across development phases. Green finance, by embedding environmental constraints, helps the economy to enter the stage of environmental improvement earlier, thereby weakening or even avoiding the path dependence of “pollution first, governance later”. The extension of this theory is not only applicable to forestry but can also provide theoretical support for the sustainable transformation of other resource-dependent industries.

Global research has examined the transmission pathways of green finance’s role in forest sector sustainable growth. Green finance instruments (such as green credit, green bonds, and green insurance) can directly affect industries with high environmental values by optimizing resource allocation, such as the improvement of forestry development levels. The core path is prioritizing environmentally compliant entities; it restricts financing for high-risk polluters [31,32,33]. Evidence from multiple regions shows that this selective financing behavior can effectively guide social capital towards sustainable forest management, thereby becoming an important foundation for promoting the high-quality development of forestry [34]. In terms of specific transmission mechanisms, it can be summarized into three aspects: (1) Direct capital allocation mechanism—by providing preferential loan conditions, attracting social capital, expanding the investment scale of the forestry sector, reducing corporate financing costs, and increasing output levels [35,36]; (2) Industrial structure adjustment mechanism—by raising the financing costs of high-pollution industries or reducing loan amounts, promoting their transformation or exit, and guiding funds to green industries such as forestry, thereby enhancing the competitiveness of the green sector [37,38,39]; (3) Innovation-driven mechanism—by optimizing the financing structure through credit guarantees, interest-free loans, bond financing, etc., lowering the financial threshold for innovation activities, and thus promoting the research and diffusion of green technology.

Further analysis shows aligning China’s new development concepts with global sustainable forestry frameworks can systematically clarify green finance’s indirect pathways in forestry’s high-quality development. Relevant research indicates that environmental innovation-driven R&D activities (ER&D) are key to achieving sustainable green coordinated development in forestry [40,41]; green technological innovation provides direct motivation and technical support for sustainable forestry development [42,43]; while alleviating financing constraints is an important prerequisite for realizing an open, innovative, green, and shared development model [44,45,46]. These transmission mechanisms are highly aligned with international frameworks such as “sustainable forest management”(SFM), “forest landscape restoration”(FLR), and “natural solutions”(NbS), taking into account ecosystem integrity (such as biodiversity, soil erosion control), social benefits (such as community participation, livelihood improvement), and economic resilience (such as value chain enhancement and risk response capabilities), thereby endowing green finance with replicability and policy spillover effects in global forestry governance. However, global forestry development still generally faces challenges such as large financing gaps, long-term capital shortages, and imperfect risk-sharing mechanisms (such as insurance), which are particularly prominent in developing countries and form a clear contrast with developed countries.

Consequently, this study advances the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.

Green finance boosts HQDF via environmental research and development (ER&D) facilitation, innovation driving, and forestry financing easing.

3. Methodology and Data

3.1. Model Construction

First, to test the relationship between green finance and HQDF, this paper builds a two-way regional and time fixed effects model.

where i denotes province and t denotes time; represents the level of high-quality development of forestry in province i in year t; denotes the level of green finance in province i in year t; denotes province fixed effects; denotes time fixed effects; and denotes the nuisance term.

To explore the dynamic effects of green finance on HQDF at different stages, we employed the panel quantile method. This approach allows us to estimate the impact of green finance on HQDF across different quantiles of the explanatory variable. Traditional panel quantile models face challenges in interpreting results due to the fixed effects term, which decomposes the random disturbance term. To address this issue, we utilized the Quantile Regression for Panel Data with Nonadditive Fixed Effects (QRPD) model proposed by Powell [47]. The QRPD model incorporates panel quantile estimation within the instrumental variables framework, resulting in more accurate and robust coefficient estimates. We focused on five quartiles (10%, 30%, 50%, 70%, 90%) to construct the panel quantile function using QRPD.

where denotes the corresponding quantile; denotes HQDF at the corresponding quantile; denotes green finance at the corresponding quantile; denotes a set of control variables at the province level at the corresponding quantile. The QRPD model used in this study is a special case of Generalized Quantile Regression (GQR) designed for panel data analysis. It shares the same explanatory power as the GQR model and allows for quantile regression estimation in panel data settings. In the QRPD model, the regression coefficients describe the effects of explanatory variables at different quantile points. To estimate the QRPD model, we employed the adaptive Monte Carlo method (Adaptive MCMC), which has been shown to provide reliable estimates [48,49].

3.2. Variables

3.2.1. Explained Variable

The construction of the HQDF indicator system in this study follows several principles to ensure objectivity and comprehensiveness. The first principle is comprehensiveness, selecting indicators that capture the essence of HQDF and reflect its basic characteristics. The second principle is representativeness, choosing mainly representative indicators to avoid missing key aspects. The third principle is comparability, using proportional and intensity indicators to allow for comparison across provinces with different levels of development. The fourth principle is operability, considering data availability and ensuring validity and applicability. The fifth principle is simplicity, avoiding excessive indicators that may lead to data correlation issues or difficulties in determining weights. Based on the connotation of HQDF, the principles mentioned above, and the new development concepts, the evaluation of HQDF covers eight levels: input and output efficiency, production and operation efficiency, structural optimization efficiency, technological innovation efficiency, scientific and technological innovation efficiency, international influence, ecological and environmental efficiency, carbon sink efficiency, and social welfare efficiency.

The HQDF indicator system consists of various dimensions. (1) Input–output efficiency measures the productive use of forestry resources using a meta-front DEA and directional distance function (see Appendix A for more details). (2) Production and operation efficiency assesses market performance through forest land output rates and value-added growth. (3) Structural optimization reflects the degree of industry structure optimization based on the output value of the tertiary forestry. (4) Innovative advancement encompasses tech enhancements and sci-tech breakthroughs, gauged by metrics like R&D funding and internal R&D costs. (5) International competitiveness is evaluated using FDI in forestry and total import/export of forest products. (6) Forestry eco-environmental benefits are measured by factors such as planted forest area and natural areas protected. (7) Carbon sink benefits capture the forest’s role in absorbing CO2, estimated using carbon sequestration data. (8) Social welfare benefits consider the impact on people’s income, livelihood, and quality of life, including factors like wages, income from forestry tourism, and outputs from industries related to forestry tourism. Additionally, the inclusion of forestry floral professionals reflects human capital conservation and improved quality of forestry resources.

To ensure transparency and replicability, the HQDF index system was constructed from 22 indicators across five dimensions and eight sub-dimensions (Table 1), with data drawn from authoritative sources such as the China Statistical Yearbook, Forestry Yearbooks, and relevant environmental and economic statistical bulletins. The measurement of HQDF adopts the method of expanding levels both vertically and horizontally. Compared with other empowerment methods, the advantages of this approach are: (1) the evaluation results are relatively objective; (2) it is suitable for panel data; (3) it can perform cross-sectional comparisons, reflecting the dynamic characteristics of the evaluation indicators. The specific calculation steps are as follows:

Table 1.

Indicator system for high-quality development of forestry.

First, the data is standardized using the interquartile range method. For positive indicators, the standardization formula is:

For reverse indicators, the standardization formula is:

Secondly, determine the weights of the evaluation indicators . Let set be the set of objects to be evaluated, is the weight coefficient vector of indicators, representing the raw value of the j-th indicator of the i-th province in the year, is the value after the has been normalized without dimensions. For any given time , the comprehensive evaluation function is taken as follows.

The differences between each evaluated object can be characterized by the total sum of squared deviations of , that is . Since the original data has been normalized, we have:

Here, is an m × m symmetric matrix, and . It can be proven that if is limited, when W is the eigenvector corresponding to the maximum eigenvalue of matrix H, 62 takes its maximum value. To ensure all weights are positive, it is further limited that W > 0. That is, by solving the programming problem of Equation (3), the weight coefficient vector W can be calculated.

3.2.2. Key Independent Variables

The primary independent variable is green finance (green). The green finance index was built from seven secondary indicators—including green credit, green investment, green insurance, green bonds, green support, green funds, and green rights (Table 2)—measured as proportional or intensity ratios to ensure comparability across provinces. The data primarily originates from websites of authoritative institutions such as the National Bureau of Statistics, the Ministry of Science and Technology, and the People’s Bank of China, as well as various authoritative statistical yearbooks, including national and provincial statistical yearbooks, environmental condition bulletins, and some professional statistical yearbooks, such as the “China Science and Technology Statistical Yearbook,” “China Energy Statistical Yearbook,” “China Finance Annual,” “China Agricultural Statistical Yearbook,” “China Industrial Statistical Yearbook,” and the “China Tertiary Industry Statistical Yearbook.” Data were standardized using the same method as HQDF. And we used the entropy value method to measure the comprehensive index of green finance (see Appendix B for more details). This transparent construction aligns with prior methodologies [50,51], enabling robust cross-sectional and temporal comparisons.

Table 2.

Evaluation system of green finance development level indicators.

3.2.3. Other Variables

Inspired by prior studies [52,53,54], and other studies, along with factors affecting HQDF, control variables include: (i) Environmental regulation (ers): Investment in industrial pollution control relative to industrial value added. (ii) Government intervention (gov): Local fiscal expenditure as GDP share, adjusted for inflation. (iii) Human capital level (hr): Average years of education per capita, with specific years assigned per education level. (iv) Advanced industrial structure (hle): Tertiary sector value added to secondary sector value added ratio. (v) Industrial structure rationalization (rat): Thiel index for rationalization assessment. It is shown as model 4.

3.3. Data

Given data accessibility, this study employs panel data from 30 Chinese provinces and cities (excluding Tibet, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan due to data gaps) spanning 2010~2023. Data sources include the China Statistical Yearbook, Forestry and Financial Yearbooks, Environmental and Science & Technology Yearbooks, CEADs, CSMAR, bank and company CSR reports, key investment sites, provincial yearbooks, State Intellectual Property Office website, EPS, and WIND databases. Descriptive statistics and variable correlation coefficients are detailed in Appendix C. Observations indicate that variable correlation coefficients, with the highest being under 0.7. The maximum VIF for any variable is 2.72, significantly below 10, indicating negligible multicollinearity concerns.

4. Analysis of Empirical Results

4.1. Measurement Results of Green Finance and HQDF

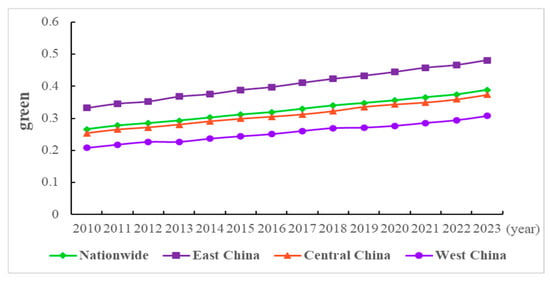

Figure 2 illustrates the green finance development levels across various Chinese regions. In terms of overall trend, the development of China’s green finance from 2010 to 2023 has gone through a process of slow start, rapid expansion, and then steady growth. In the early stages, due to the incomplete institutional framework and limited market recognition of the concept of green finance, the development curve was relatively flat. With the establishment of green finance reform pilot areas, the implementation of green bonds and green credit policies, capital began to flow increasingly towards green industries, and the level of development significantly improved in the medium term. In the later stages, the introduction of the carbon peak and carbon neutrality strategies accelerated capital inflows into renewable energy, clean production, and other fields. At the same time, the widespread adoption of ESG investment concepts transformed green finance from being policy-driven to being driven by both policy and market forces, forming a stable situation with high-level operation. This evolution highlights the guiding role of policy in the early stages and the endogenous supportive force of market mechanisms maturing in the later stages for growth.

Figure 2.

Changes in the level of green finance development in China from 2010 to 2023.

Figure 3 illustrates China’s green finance development distribution across regions. The spatial distribution shows a pattern where the eastern coastal areas are significantly leading and the central and western regions are gradually catching up. Relying on a strong economic foundation, dense financial institutions layout, and higher policy execution, the eastern region has formed a high-concentration area for green finance development. The overall level in areas such as the Yangtze River Delta and the Pearl River Delta is far above the national average. Under the push of energy structure adjustment and ecological protection projects, the scale of green finance investment in the central and western regions has increased. However, due to constraints such as single industrial structure and insufficient financial system density, the overall development level is still low. The formation of this spatial difference not only reflects the differences in economic development stages and industrial types but also reveals the imbalance between policy transmission efficiency and regional financing capabilities. It indicates that future green finance strategies need to formulate differentiated regional support policies to promote balanced regional development.

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of green finance development levels in China from 2010 to 2023. Notes: The map is based on the standard map (review number GS (2019)1822) of the Map Technical Review Center of the Ministry of Natural Resources, with no modifications to the base map.

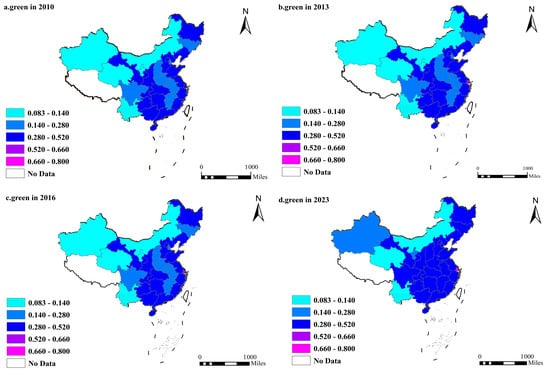

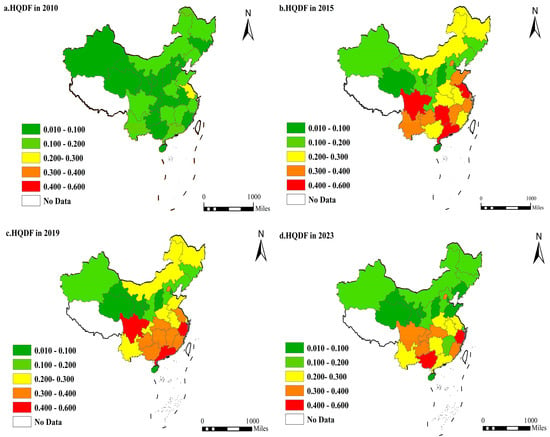

Figure 4 illustrates the spatial and temporal changes in the measurement results of HQDF. From 2010 to 2023, the level of high-quality development in China’s forestry has shown a consistent and steady upward trend, reflecting the long-term driving effect of green transformation and ecological civilization construction. In the early stages, forestry development mainly pursued the increase in forest coverage, and although progress was made in the scale of afforestation, the quality increase was limited. With the deepening implementation of the national ecological civilization strategy and the “Forest Quality Improvement Project,” the service functions of the forestry ecosystem have been significantly enhanced, and both forest quality and production efficiency have improved simultaneously. In the past three years, the widespread application of new technologies and models such as precision forestry management, remote sensing monitoring, and carbon sink trading has achieved a synergistic improvement in both economic and ecological benefits of forestry. Overall, China’s forestry development is shifting from simple quantitative expansion to quality optimization, showing characteristics of compound sustainable growth that takes into account economic, ecological, and social values.

Figure 4.

Temporal variation of the high-quality development of China’s forestry.

Figure 5 provides a visual representation of the spatial variations and dynamic changes in HQDF. The spatial pattern of high-quality forest development shows that regions with abundant southern forestry resources generally lead the way. These areas benefit from favorable natural conditions, strong policy support, and market demand, forming a dual advantage of ecology and industry. In particular, the southwestern region has built a relatively complete green industrial chain by leveraging diverse ecological resources. While some northern regions have achieved significant results in expanding afforestation areas, the speed of ecosystem stability and biodiversity improvement is relatively slow, and there is a certain gap between ecological benefits and economic benefits. Economically developed eastern regions have deeply integrated forestry with modern green industries through capital, technology, and management advantages, achieving a high-value-added forestry economic model while maintaining a good level of ecological protection. This spatial distribution pattern not only reflects the differences between natural endowments and economic foundations but also reminds us that in resource-based and arid areas, we should increase scientific and technological investment and ecological compensation to narrow the gap in high-quality development among different regions.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of HQDF in China over 2010–2023. Notes: The map is based on the standard map (review number GS (2019)1822) of the Map Technical Review Center of the Ministry of Natural Resources, with no modifications to the base map.

4.2. Baseline Regression Results

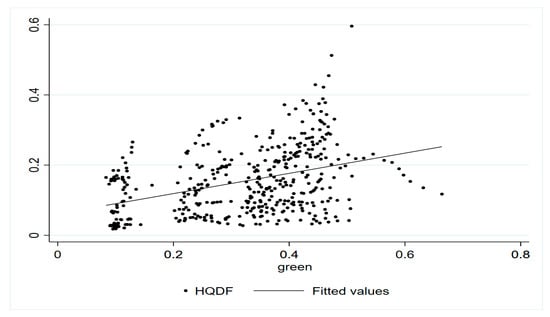

Prior to the regression analysis, the relationship between green finance and HQDF was observed more visually by drawing a scatter plot (see Figure 6). Figure 6 reveals a distinct positive link between green finance and HQDF, thus preliminarily supporting the research hypothesis.

Figure 6.

The relationship between green finance and the high-quality forestry development.

The influence of green finance on HQDF is evaluated using the benchmark model (1). Table 3, particularly columns (1) and (2), showcases the effects of green finance on HQDF, both with and without control variables and double fixed effects. The study indicates a substantial positive link between green finance and HQDF. Specifically, Column (2) reveals a 0.4850 average impact of green finance on HQDF, suggesting enhanced HQDF due to green finance growth, thus affirming Hypothesis 1. This study addresses the lack of empirical data on its effects on HQDF by providing relevant empirical evidence.

Table 3.

Benchmark regression results.

4.3. Robustness Test

We conducted several robustness tests to further validate the nexus of green finance and HQDF (For detailed results of the robustness test, please refer to Appendix D). First, by truncating the core variables, we observed that the development of green finance significantly contributes to improving HQDF, as shown in Columns (1), (2) of Panel A in Table A3 (see Appendix D). Second, when adjusting the sample period to 2010–2020, the positive correlation between green finance and HQDF remained significant with or without control variables, as shown in Columns (3), (4) of Panel A. Third, considering the policy impact of the 18th National Congress in 2012, we introduced a dummy variable (treat) that confirmed the promotion of HQDF by both green finance and the 18th National Congress, as shown in Columns (1), (2) of Panel B. Fourth, inspired by Liu et al. (2025) [55], We have recalibrated the indicators of green finance, as shown in Columns (3), (4) of Panel B. Fifth, to account for the influence of the “12th Five-Year Plan” we introduced a dummy variable (plan12), which showed a positive correlation with HQDF, as shown in Columns (1), (2) of Panel C. Finally, by considering the “13th Five-Year Plan” with the dummy variable (plan13), we again observed a positive relationship between green finance and HQDF, as shown in Columns (3), (4) of Panel C. These robustness tests consistently support the conclusion that the development of green finance has promoted HQDF. In addition, this paper further addresses endogeneity, and the results of the endogeneity analysis are provided in Appendix E.

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

The regional heterogeneity regression results show clear spatial differences (For detailed results of the heterogeneity analysis, see Appendix F). The role of green finance in promoting HQDF varies significantly across regions. In the western and southern regions, the promoting effect is most evident. The estimated coefficients are 1.1972 and 0.7744, both significant at the 1% or 5% level. This finding is consistent with the measurement analysis, which concludes that “the southern region has abundant forestry resources, a complete industrial chain, and prominent advantages in the ecological industrialization of the southwest.” (East China includes: Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Liaoning, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shandong, Guangdong and Hainan Province. Central China includes: Shanxi, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Anhui, Jiangxi, Henan, Hubei, Hunan. West China includes: Inner Mongolia, Guangxi, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia and Xinjiang.) The favourable natural conditions, supportive policies, and strong market demand in these regions jointly create strong synergies. Green finance there effectively promotes both industrial upgrading and ecological improvement. In the central region, the positive role of green finance is also evident (coefficient 0.5380), which reflects the recent success of ecological restoration and industrial-structure optimization policies. By contrast, the coefficients for the eastern and northern regions are negative and significant (−0.7520 and −0.3574). (North China includes: Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanxi, Inner Mongolia, Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Shandong, Henan, Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, Xinjiang. South China includes: Jiangsu, Anhui, Hubei, Chongqing, Sichuan, Yunnan, Guizhou, Hunan, Jiangxi, Guangxi, Guangdong, Fujian, Zhejiang, Shanghai, Hainan.)

The possible reasons are as follows. In the economically developed eastern regions, green industries and ecological protection are well integrated. However, green financial funds are mainly directed to urban green infrastructure and high value-added industries. This produces a relative “crowding out” of funds for the forestry sector. In some northern regions, the area of afforestation has expanded rapidly, but improvements in ecosystem stability and biodiversity are slow. The existing funds do not sufficiently drive both ecological and economic benefits. These patterns call for differentiated fund-allocation strategies based on each region’s natural endowment and development stage. In arid northern areas, investment in science and technology and in ecological compensation should be increased. In the east, the structure of green-finance support for forestry should be further optimized. Such measures can help narrow regional gaps and enhance overall synergies.

The underlying reasons for these regional differences must be examined through institutional economics and comparative environmental economics. The negative effects in the eastern and northern regions stand in sharp contrast to international experience. In developed European countries such as Germany and Sweden, green finance has consistently and significantly promoted forestry. This is largely due to mature environmental regulations and market-oriented resource-allocation mechanisms [56,57]. China’s eastern region, although economically advanced, shows a “Dutch disease” pattern. An overdeveloped tertiary sector and real estate market crowd out resources for forestry, which echoes resource-curse theory [58]. The negative effects in the north may reflect a mismatch between institutions and natural endowments. This is similar to the Russian Far East, where rich forest resources have not been effectively transformed into economic gains [59].

From the perspective of new institutional economics, regional differences in the effects of green finance reflect how well formal and informal institutions are coupled. Formal institutions include policies and regulations. Informal institutions involve market practices and cultural traditions. In the western and southern regions, green finance has clear positive effects. Central policies provide strong guidance, and local governments respond proactively. Together, they form a “top-down plus bottom-up” governance model, similar to the Brazilian Amazon Fund. In the eastern region, the degree of marketization is high. However, forestry is marginalized in the industrial structure. As a result, green finance tends to flow to high-return urban green-infrastructure projects. Similar patterns have appeared during the urbanization of Japan and South Korea. Additionally, we analyzed the heterogeneous effects of different categories of green financial instruments on HQDF (see Appendix G for details).

4.5. Mechanisms Analysis

The mechanism through which green finance affects HQDF is analyzed in this paper from three perspectives: environmentally induced R&D, green technology innovation, and financing constraints. To address potential endogeneity issues, the paper examines the correlation between green finance and these mechanism variables and conducts robustness tests using an instrumental variables approach.

- (1)

- Green finance and environmentally induced R&D (ER&D) (Following Zhao et al. (2022) [60] and Liu et al. (2022) [41] who decompose R&D into traditional R&D and ER&D capital stock, the perpetual inventory method was used to calculate ER&D for each province): ER&D refers to investment in research and development for environmental protection and management, is crucial for HQDF. The results in Table 4 show that green finance promotes ER&D significantly, supporting the hypothesis that green finance enhances HQDF by stimulating ER&D. The instrumental variable results confirm this positive correlation between green finance and ER&D, even when control variables are included.

Table 4. Mediating variable test results.

Table 4. Mediating variable test results. - (2)

- Green finance and green technology innovation (pat) (According to Xu et al. (2021), the number of green patents obtained by provinces and municipalities was employed to measure green technology innovation [61]): green technology innovation, characterized by the development and application of environmentally friendly technologies, plays a vital role in HQDF. The number of green patents obtained is used as a measure of green technology innovation. The results in Table 4 indicate that green finance promotes green technology innovation significantly, supporting the hypothesis that green finance enhances HQDF through fostering green technology innovation. The instrumental variable results further validate this positive relationship.

- (3)

- Green finance and financing constraints (fin) (According to Hadlock et al. (2010) [62], and following the model: , where Size is the size of the firm, measured by the logarithm of total assets, and Age is the age of the firm, i.e., the current year minus the year of IPO + 1, the SA index is calculated as a measure of financing constraint. A negative SA index with a larger value indicates a higher degree of financing constraint [62]): Sufficient capital support is essential for HQDF, and alleviating financing constraints is crucial in this regard. The results in Table 4 demonstrate that green finance has significantly eased financing constraints. The instrumental variable results consistently confirm this relationship, irrespective of the inclusion of control variables.

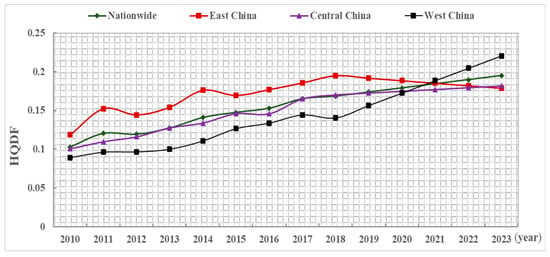

4.6. Marginal Effect at Different Development Stages

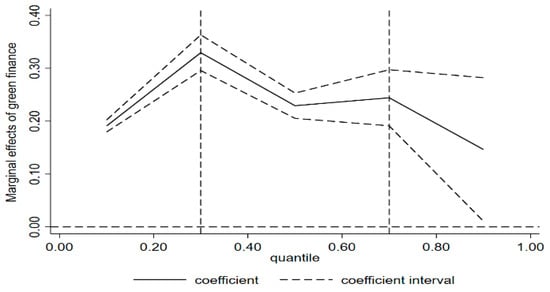

To more vividly and accurately evaluate the marginal effect of green finance and its dynamic trajectory at different stages of the high-quality forestry development, panel quantile regression model (2) was utilized in the paper, and the regression results are listed in Table 5. In addition, the trajectory of the marginal effect of green finance with all control variables considered is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Quantile regression results.

Table 5 and Figure 7 show that the marginal effect of green finance on HQDF is dynamic. Its intensity changes with the development stage and follows an “increase-then-decline” pattern. In the initial stage (low quartile 10–30%), the effect of green finance is positive and significant, but small in magnitude and highly uneven. This suggests that, at the early stage, green-finance injections are constrained by a weak industrial base, low project maturity, and poor matching between products and forestry needs. As a result, funds are hard to convert into substantial immediate outputs. Even so, green finance still plays a foundational role at this stage by improving funding availability and supporting infrastructure construction and ecological restoration.

Figure 7.

Marginal effects of green finance.

Entering the growth stage (median quantiles 30–50% and 50–70%), the marginal effect of green finance rises sharply and shows strong momentum. This reflects a shift toward scale and specialization in HQDF. In this phase, the capital-guidance, risk-management, and technical-support functions of green finance are fully activated. The match between financial capital and green projects improves markedly, leading to a period of intensive investment and rapid output growth. At this stage, green finance not only directly supports upgrading of the forestry industrial chain. It also boosts the overall competitiveness of forestry in both ecological and economic dimensions by introducing green innovations and improving the carbon-sink market mechanism.

As development enters the mature stage (high-score range 70–90%), the marginal effect of green finance remains significantly positive but starts to decline. This may be linked to a more stable industrial structure, slower returns on new investment, and reduced room for marginal improvement. In this stage, green finance shifts from driving rapid incremental growth to maintaining and optimizing existing forestry ecosystems and economic systems. Investment increasingly targets quality enhancement, long-term ecosystem maintenance, and risk prevention. As a result, the marginal contribution rate falls, but it remains above that of the initial stage, indicating that green finance continues to support forestry across the entire life cycle.

In summary, the effect of green finance on HQDF is both stage-specific and dynamic. Its role is limited in the early stage, rises sharply in the middle stage, and remains positive but more concentrated in the mature stage. This pattern shows that the action mechanism of green finance evolves with the industry life cycle and also points to clear policy directions. In the early stage, green-finance infrastructure and project-matching mechanisms should be strengthened to improve the efficiency of fund use. In the growth stage, the focus should be on integrating capital and technology to maximize the multiplier effect of funds. In the mature stage, policies should emphasize quality maintenance and risk management to secure the long-term and stable contribution of green finance. Such phased and refined policy and investment strategies can maximize the synergy between forestry economic returns and ecological benefits, and provide robust support for achieving carbon neutrality.

The inverted-U pattern across quantiles reflects dynamic efficiency gains during the scaling-up phase of HQDF, followed by a saturation effect in the mature stage, where marginal returns to additional green finance inputs decline. This nonlinear relationship is robust to alternative specifications. When we re-estimate the QRPD model with trimmed samples and region-specific controls, we obtain similar trajectories. Partial-effect plots across quantiles further show that the surge in marginal impact during the growth stage is the strongest, whereas impacts in the mature stage remain positive but are noticeably flatter.

From a global perspective, similar patterns in the relationship between green finance and sustainable forestry are evident. In the European Union, especially in Scandinavian countries, mature green-finance systems channel investment into eco-innovation and low-carbon technologies [9,63]. This has boosted forest productivity and strengthened long-term ecological resilience. In contrast, many developing economies in Southeast Asia, Latin America, and parts of Africa face persistent obstacles. Limited policy-implementation capacity, poor access to green finance instruments, and weak private-sector participation all hinder the conversion of financial resources into real forestry gains. China’s regional disparities—particularly the slower progress in some central and western provinces—are broadly consistent with the constraints seen in other emerging economies. This global comparison highlights the need for region-specific policies, stronger capacity building, and deeper international cooperation to fully harness green finance as a driver of HQDF.

4.7. Discussions

The heterogeneity findings of this study can be interpreted through several theoretical lenses. From an institutionalist perspective, North’s (1990) theory of institutional change holds that the effectiveness of formal institutions depends on their compatibility with informal institutions [64]. The strong effects of green finance in western and southern China indicate a good match between central policies (formal institutions) and local ecological and cultural traditions (informal institutions). This aligns with Ostrom’s (1990) theory of polycentric governance, which stresses that effective environmental governance relies on coordination among multiple levels of institutions [65].

From the perspective of comparative environmental economics, regional differences in the applicability of Porter’s hypothesis offer a new way to interpret the effects of green finance. In regions with strong technological absorptive capacity, environmental regulation can stimulate innovation via green finance and thus achieve a “win–win” outcome. In regions with weak technological foundations, however, “compliance costs” may exceed “innovation benefits.” This helps explain why the more developed eastern regions instead show negative effects. In the short term, stringent environmental standards raise the burden on forestry enterprises, while the compensating effects of innovation have not yet fully materialized.

Resource-dependence theory also helps explain these regional gaps. Bradley et al. (2011) argue that an organization’s survival depends on its ability to secure critical resources [66]. In the western and southern regions, forestry resources are abundant. Green finance capital complements these natural endowments and generates strong synergies. In the relatively resource-scarce north, however, capital alone cannot offset the disadvantages of weaker natural conditions.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

5.1. Conclusions

Using provincial panel data for China from 2010 to 2023, this paper constructs an index of high-quality forestry development based on a vertical-and-horizontal expansion approach and evaluates the impact of green finance through two-way fixed-effects models, panel quantile regression, and instrumental-variable methods. The empirical results show that green finance significantly promotes HQDF overall. This promotion effect exhibits a clear inverted U-shaped pattern over different development stages. In the initial stage, the effect is limited because of weak basic conditions and poor matching between financial products and forestry projects. During the growth stage, deep integration among capital, technology, and industry sharply amplifies the effect. In the mature stage, the effect slows but remains positive and stable, supported by quality upgrading and improved risk management.

Regional heterogeneity is also evident. The promoting effect of green finance on HQDF is strongest in western and southern China, followed by the central region, while some eastern and northern provinces display negative effects. Different green-finance instruments play distinct roles. Green investment and green bonds have the largest positive impacts on HQDF. Green insurance and fiscal support funds rank next, while green funds and green credit are particularly important at specific stages of the forestry development cycle.

Viewed from a global perspective, China’s experience in using green finance to advance HQDF is broadly consistent with trends in other regions. Developed economies—especially those in Europe and Scandinavia—rely on mature green-finance systems to channel capital into ecological innovation, renewable energy, and sustainable forest management, thereby enhancing both forest productivity and ecosystem resilience. Many developing countries in Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Africa face persistent challenges, including limited policy implementation capacity, an undersupply of green-finance products, and insufficient private-sector participation. As a result, their progress is relatively slow.

China’s own pattern—strong effects in western and southern regions but weaker or even negative effects in some eastern and northern regions—echoes this global heterogeneity. The comparison suggests that targeted policy design, stronger institutional capacity, and deeper international cooperation are essential. These elements can unlock the full potential of green finance and offer practical pathways for other economies to promote sustainable forestry and ecological protection.

5.2. Policy Implications

Several policy implications follow from these findings.

First, green finance support should be aligned with the inverted U-shaped dynamics of HQDF and designed in a staged manner. The marginal impact of green finance is not linear. It depends on how well capital supply, technological absorption, and the institutional environment are matched. In the initial stage, green credit and fiscal funds should form the core, addressing basic financing constraints and infrastructure gaps. During the growth stage, the emphasis should shift towards larger-scale green investment and green bonds to deepen the integration of capital, technology, and industry. In the mature stage, green insurance and stable long-term funds should be used to maintain quality and resilience. This staged configuration not only informs policy practice but also enriches the theory on how green finance and industrial development stages are coupled, implying that the mix of instruments must adjust dynamically as industries evolve.

Second, regional differentiation is necessary to achieve more balanced overall development. The findings show that the west and south, with favourable resource endowments and institutional environments, are more likely to form a high-efficiency coupling among capital, technology, and ecology. By contrast, some eastern and northern regions experience negative effects because of industrial-structure bias and misallocation of financial resources. Policy design should therefore accelerate technological upgrading and ecological restoration in regions with strong comparative advantages, improve information platforms and project-matching mechanisms in central regions, and introduce technology-intensive green projects and risk-compensation schemes in less-developed areas. This approach reflects the logic of spatial heterogeneity, where policy effectiveness depends jointly on resource endowment, institutional capacity, and market maturity.

Third, the portfolio of green finance instruments should be optimized to match specific stages and regional conditions. The results indicate that green investment and green bonds are most effective for overall and medium-to-high-speed development phases. Green insurance and fiscal funds are especially important for risk prevention and infrastructure. Funds and green credit can provide flexible and structural support at particular points in the development cycle. Policymakers should also strengthen the carbon market, convert forestry carbon sinks into tradable assets, and build a closed loop between capital inflows and ecological benefits. This not only enhances the efficiency of fund use but also offers empirical support for a performance-oriented green finance mechanism.

Fourth, enhancing international cooperation and institutional capacity is essential for amplifying the global spillover effects of China’s experience. China’s model of regionally differentiated allocation and multi-instrument combinations is highly compatible with the mature systems in many developed economies and can offer concrete options for developing countries that face policy-implementation gaps and product shortages. International organizations can promote the creation of cross-border forestry green funds and technology-sharing platforms tailored to different institutional environments. This would accelerate the scaled application of green finance in the forestry sector and illustrate, at a theoretical level, how transnational institutional adaptation and ecological-capital flows support carbon neutrality goals and global ecological resilience.

Finally, the transferability of China’s experience to other countries must account for differences in institutional settings, development stages, and resource endowments. For emerging economies at a similar stage—such as India, Brazil, and Indonesia—a phased strategy can be adapted. In the early stage, policy-oriented financial instruments can address basic market failures. In the middle stage, market-based mechanisms can improve efficiency. In the mature stage, the focus can shift to risk management and quality maintenance. However, each country needs to adjust this template to its own conditions. India’s fragmented land-tenure system requires stronger community-based finance. Brazil’s federal structure calls for more robust cross-state coordination mechanisms. Indonesia’s archipelagic geography requires a decentralized green finance service network.

For developed countries, the main value of China’s experience lies in demonstrating how to balance government guidance and market mechanisms in a dynamic way. The United States and Canada can draw on China’s regional-differentiation strategies to offer more support to lagging areas. European Union member states can learn from China’s multi-instrument approach, especially for forestry development in Central and Eastern Europe. At the same time, the mature carbon-market practices of developed countries provide important lessons for China, creating opportunities for two-way learning.

For the least-developed countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, a more gradual pathway is required. The priority is to establish a basic green-credit system to improve access to finance. The next step is to introduce technologies and management experience through international cooperation. Over time, countries can then build localized green finance markets. China’s experience with South–South cooperation, such as forestry projects funded by the China–Africa Development Fund, offers a useful and replicable model for such contexts.

5.3. Limitations

Despite addressing the connection between green finance and high-quality forestry development, this study has certain limitations. Firstly, the analysis was conducted at the provincial level due to data availability, overlooking the substantial economic and social differences among cities within the provinces. Future research could explore the relationship at a more granular city-level if data becomes accessible. Secondly, as the subsequent research continues, the green finance index rating system needs to be further improved. Lastly, considering the approaching deadlines for the “double carbon” strategic targets, it is crucial to investigate whether the synergy between green finance and high-quality forestry development can contribute to achieving the goals of carbon peak in 2030 and carbon neutrality in 2060. Urgent attention should be given to this aspect in future research.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design, data collection and some form of analysis. X.L.: Writing—original draft; Data collection and curation; Conceptualization; Frame design; Modification of the article; Resources; Software; Validation; Visualization; J.H.: Conceptualization; Data collection and curation; Modification of the article; W.Z.: Conceptualization; Frame design; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Project administration; Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been supported by the Sichuan Provincial Natural Science Foundation for Young Scholars—“Mechanism and policy optimization of green finance innovation driving pollution reduction and carbon emission reduction synergy in Sichuan province” (Grant No. 2025NSFSC1966)—and the key project of the National Social Science Foundation of China—“Research on policy framework and innovation path of green finance to promote the realization of carbon neutrality goal” (Grant No. 21AZD113).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the National Bureau of Statistics of China or can be obtained from the authors on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Global Meta-Frontier DEA Combined with Directional Distance Function (DDF)

Firstly, the concepts of environmental technology and meta-frontier. It is defined that represent various types of inputs, expected outputs (good outputs), and unexpected outputs (bad outputs). Based on this, the production possibility frontier can be represented as:

In the formula above, represents the number of decision-making units; is a variable that constitutes the production possibility boundary and connects inputs and outputs. In fact, in Formula (A1), both the inputs and outputs of (including expected and unexpected outputs) are strongly controllable. In other words, inputs and outputs satisfy the following characteristics: if and or , then there exists an inclusion relationship or ; if and or , then there exists an inclusion relationship or .

As shown above, due to the strong controllability of unintended outputs, we can reduce unintended outputs without increasing any costs. However, in real life, we cannot randomly reduce these unintended outputs; that is, reducing unintended outputs requires certain costs. Therefore, Färe et al. (1989) believe that unintended outputs should meet weak processing properties [67]. That is, Formula (A1) can be rewritten as:

Comparing Formulas (A1) and (A2), it can be seen that the restriction condition for unexpected outputs has changed from to . The weak processing nature of unexpected output can be written as: if and , there is an inclusion relationship . This means that we cannot arbitrarily reduce unexpected outputs, and reducing unexpected outputs requires a certain cost.

To this point, we have introduced the concept of environmental technology to handle unintended outputs. Next, we introduce the concept of meta-frontier outputs to address regional heterogeneity. All decision-making units are divided into subsets, where represents the number of decision-making units contained in the th subset. Then, all decision-making units within the th subset constitute the production possibility frontier (PPF) for that subset. Ultimately, the meta-frontier PPF includes all sublevel PPFs .

Secondly, the direction distance function, meta-frontier DEA method, and its inefficiency items in the forestry GTFP. In the actual production process, people always pursue the maximization of expected output and the minimization of unexpected output. Therefore, this study introduces the direction distance function:

in Equation (A3) represents the direction vector , and the optimal solution of DDF in Equation (A3) is the maximization of y and the minimization of u.

Combining Formula (A2), the optimal solution for the meta-frontier production function below can be expressed as follows:

In Formula (A4), CRS represents the optimal solution for under the condition of constant scale returns. , , and respectively represent decreasing, constant, and increasing scale returns.

Based on the production possibility boundary of subset , the optimal solution for function can be expressed as follows:

To this point, the total factor productivity of forestry can be represented as and in the cases of output at the frontier of yuan and grouped output at the frontier.

Forestry total factor productivity decomposition is as follows:

The TGR represents the technical gap ratio between the subset and the overall. A higher TGR indicates a smaller gap between the subset and the overall, and vice versa. TE stands for technical efficiency, and the decomposition of net technical efficiency is as follows:

GTFP is represented by constant returns to scale (VRS); SE stands for scale efficiency; PE represents pure technical efficiency. To this end, GTFP can be broken down into TGR (technological gap ratio), SE (scale efficiency), and PE (pure technical efficiency).

According to the definition, the direction distance function measures the distance between the estimated decision unit and the production frontier. In other words, can be regarded as a non-efficiency item estimated by the DMU of GTFP. Accordingly, GTFP can be decomposed into:

Among them, TGI, SEI, and PEI respectively represent the inefficiencies in technical gap, scale efficiency, and pure technical efficiency.

Finally, the global Malmquist index for the decomposition of forest GTFP changes. In order to examine the driving factors of forest GTFP changes, a Malmquist index that decomposes forest GTFP changes is introduced. Pastor and Lovell (2005) pointed out that the traditional simultaneous Malmquist index, which is built based on the simultaneous production possibility boundary and used to decompose TFP changes, is not cyclic and is easily affected by the unfeasibility of linear programming [68]. Therefore, following the approach of Pastor and Lovell (2005) [68], a global Malmquist index is established based on the global production possibility boundary to decompose TFP changes At this time, the production possibility boundary at period t can be represented as:

Global PPS implies that encompasses all the production possibility boundaries of the same period. Assuming the sample covers I periods, then the relationship between and can be defined as:

Based on , the change rate of the Forestry GTFP between two consecutive years t and t + 1 can be expressed as:

Here, represents the growth rate of GTFP, denotes the direction distance function for the period t + 1 based on , and is the direction distance function for the period t based on .

The GM index can be further broken down into two parts: Technological progress (GTCH) and efficiency progress (GECH), as shown below:

GTCHt,t+1 and GECHt,t+1 respectively represent the technological progress and efficiency improvement of two consecutive years. If GTCHt, t+1 is greater than 1, it indicates that there has been technological progress in the two adjacent years, and vice versa; if GECHt,t+1 is greater than 1, it indicates that there has been an efficiency improvement in the two adjacent years, and vice versa.

Combining Formulas (A6) and (A7), GECH (Efficiency Progress) can be further broken down into the following three parts:

Here, , , and respectively represent the changes in the technical gap rate, scale technical efficiency, and pure technical efficiency over two adjacent periods. If the change in the technical gap rate (TGCH) is greater than 1, it indicates that the technical gap ratio has increased over the two years, narrowing the gap, and vice versa. If the change in scale efficiency (SECH) is greater than 1, it signifies that scale efficiency has improved over the adjacent two years, and conversely. If the change in pure technical efficiency (PECH) is greater than 1, it indicates an enhancement in pure technical efficiency over the adjacent two years. Until now, forestry total factor productivity changes, that is, GM, have been broken down into four parts: technological change (GTEC), change in the technical gap rate (TGCH), scale change (SECH), and change in pure technical efficiency (PECH).

Appendix B. Entropy Value Method

The entropy method is an objective weighting method based on the information entropy of the index. The smaller the information entropy is, the greater the dispersion degree of the index is, the more information it contains, and the greater the weight it gives. The entropy method can avoid the subjective errors of subjective weighting methods such as analytic hierarchy process and expert scoring method, and can avoid the lack of information caused by principal component analysis, so it is widely used in comprehensive evaluation. The specific steps of the entropy method are as follows.

First, the original data was standardized. Since the indicators in this paper are positive indicators, the standardization method can be expressed as.

Since the 0 value could appear after standardization, the standardized data is translated: .

Second, under the calculation of indicator j, the proportion of region i in this indicator is , where n is the number of samples and m is the number of indicators.

Third, we calculate the index entropy of item j. That is, .

Fourth, we calculate the variance factor for item j. .

Fifth, the difference coefficient is normalized to calculate the weight of j. .

Finally, we calculate the index of HQDF. .

Appendix C. Descriptive Statistics and Variable Correlation Coefficients

Table A1.

Descriptive statistics.

Table A1.

Descriptive statistics.

| VarName | Obs | Mean | SD | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HQDF | 420 | 0.1548 | 0.0964 | 0.1435 |

| green | 420 | 0.3253 | 0.1260 | 0.3510 |

| ers | 420 | 1.1698 | 0.8318 | 0.8987 |

| gov | 420 | 0.2445 | 0.1012 | 0.2220 |

| hr | 420 | 9.2544 | 0.9496 | 9.1891 |

| hle | 420 | 1.3467 | 0.7539 | 1.1892 |

| rat | 420 | 0.1526 | 0.0969 | 0.1409 |

Table A2.

Correlation coefficients between variables.

Table A2.

Correlation coefficients between variables.

| green | ers | gov | hr | hle | rat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| green | 1 | |||||

| ers | −0.438 | 1 | ||||

| gov | −0.441 | 0.152 | 1 | |||

| hr | 0.404 | −0.165 | −0.334 | 1 | ||

| hle | 0.305 | −0.145 | 0.081 | 0.679 | 1 | |

| rat | −0.532 | 0.376 | 0.373 | −0.554 | −0.426 | 1 |

Appendix D. Robustness Test Results

Table A3.

Robustness test.

Table A3.

Robustness test.

| Panel A: The explained and explanatory variable have been winsorized and the period has been adjusted to 2010–2020. | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| HQDF | HQDF | HQDF | HQDF | |

| green | 0.4106 *** | 0.5246 *** | 0.4061 *** | 0.5020 *** |

| (2.8676) | (3.5711) | (3.1889) | (3.9138) | |

| CV | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| _cons | 0.0574 | 0.2624 | 0.0400 | 0.3494 *** |

| (1.1262) | (1.4104) | (0.9013) | (2.6487) | |

| Province fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 420 | 420 | 330 | 330 |

| r2_a | 0.7730 | 0.7997 | 0.8771 | 0.8971 |

| Panel B: Exclusion of the effect of the 18th National Ecological Civilization Policy and the replacement of green finance measurement. | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| HQDF | HQDF | HQDF | HQDF | |

| green | 0.3493 ** | 0.4850 *** | ||

| (2.2909) | (2.9993) | |||

| treat | 0.0422 ** | 0.0603 * | ||

| (2.3912) | (1.6553) | |||

| green2 | 0.0765 ** | 0.0948 ** | ||

| (2.0927) | (2.5457) | |||

| CV | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| _cons | 0.0777 | 0.2810 | 0.1785 *** | 0.2401 |

| (1.4322) | (1.3950) | (10.0206) | (1.1800) | |

| Province fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 420 | 420 | 420 | 420 |

| r2_a | 0.7475 | 0.7731 | 0.7470 | 0.7505 |

| Panel C: Excluding the effect of the 12th Five-Year Plan and 13th Five-Year Plan policies. | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| HQDF | HQDF | HQDF | HQDF | |

| green | 0.3493 ** | 0.4850 *** | 0.3493 ** | 0.4850 *** |

| (2.2909) | (2.9993) | (2.2909) | (2.9993) | |

| plan12 | 0.0148 | 0.0218 | ||

| (1.1275) | (1.1095) | |||

| plan13 | 0.0422 ** | 0.0603 * | ||

| (2.3912) | (1.6553) | |||

| CV | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| _cons | 0.0777 | 0.2810 | 0.0777 | 0.2810 |

| (1.4322) | (1.3950) | (1.4322) | (1.3950) | |

| Province fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 420 | 420 | 420 | 420 |

| r2_a | 0.7475 | 0.7731 | 0.7475 | 0.7731 |

Notes: ***, **, and * indicate significance level at 1%, 5%, and 10% respectively, and the values in () represent t-statistics. r2_a is adjust R2. CV denotes control variables.

Appendix E. Endogeneity Treatment

The endogeneity issues are addressed by employing an endogenous treatment approach. First, this article constructs an instrumental variable using the degree of terrain undulation in various regions from the perspective of surface and topographic features. Generally speaking, the flatter the degree of terrain undulation in a region, the more conducive it is to the transmission of information, the construction of infrastructure such as software industries, and thus to the development of local green finance business. Therefore, there is a significant correlation between the degree of terrain undulation in a region and the development of green finance, satisfying the “relevance” assumption of the instrumental variable. Since this indicator is cross-sectional data, this paper adopts Nunn and Qian’s (2014) approach using the interaction term between the degree of terrain undulation in various regions and the green finance of the previous year to construct panel data, as the instrumental variable for green finance [69]. In addition, topographic features are exogenous variables that are detached from the economic system, satisfying the “exogeneity” assumption of the instrumental variable. Table A4’s columns (1) and (2) reveal that IV1’s estimated coefficient is 0.0368. It indicates a strong positive link between the chosen instrumental variables and green finance. Additionally, the green finance coefficient in the column remains positive, affirming the robustness of the baseline regression results.

Second, the province’s financial institution count interaction with the preceding year’s green finance is chosen as the instrumental variable (IV2). The selection is rationalized by the fact that areas with numerous financial entities tend to engage more in green finance, whereas the existence of financial outlets is not inherently connected to HQDF in theory. Moreover, the prior year’s green finance advancement shows no link to this year’s HQDF. The instrumental variable regression is conducted in two stages. Columns (3), (4) in Table A4 present the results. The first-stage regression reveals a positive, significant IV2 coefficient, supporting the instrumental variable correlation theory. The second-stage analysis confirms, at the 1% significance level, a positive green finance coefficient, suggesting the research finding persists despite addressing endogeneity concerns. The weak instrumental variable test confirms the absence of a weak instrumental variable problem.

Table A4.

Endogenous treatment.

Table A4.

Endogenous treatment.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| green | HQDF | green | HQDF | |

| IV1 | 0.0368 *** | |||

| (11.7107) | ||||

| green | 2.4125 *** | 0.6328 ** | ||

| (7.4750) | (2.1718) | |||

| IV2 | 0.0184 *** | |||

| (11.7931) | ||||

| _cons | 0.1114 ** | −0.2353 | 0.0184 *** | 0.2414 |

| (2.4965) | (−1.0056) | (11.7931) | (1.2018) | |

| Province fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Anderson canon. corr. LM statistic | 128.807 | 114.517 | ||

| [0.0000] | [0.0000] | |||

| Cragg-Donald Wald F statistic | 164.109 | 139.078 | ||

| {16.38} | {16.38} | |||

| N | 420 | 420 | 420 | 420 |

| r2_a | 0.8844 | 0.6861 | 0.9011 | 0.7725 |

Notes: ***, **, indicate significance level at 1%, 5%, respectively, The values in () are t statistics, and in [] are p statistics. The original assumption of this test is that the instrumental variables cannot be fully identified. Figures in {} are 10% critical values of Stock-Yogo weak ID test. Same below if not otherwise stated.

(2) HQDF has certain persistence. To solve the problem of sequence correlation, this paper further employs system GMM approach to test the robustness of the previous conclusions. The results of Columns (1), (2) in Table A5 show that the p-values for AR (2) are all greater than 0.1, indicating that the model does not have a second-order autocorrelation problem; at the same time, the p-values for the Hansen test are 0.856 and 0.826, respectively, which cannot reject the null hypothesis, indicating that the model has passed the Arellano–Bond serial correlation test and the Hansen test, and the system GMM model is valid. The results of Table A5 show that the coefficient of green was significantly positive at the 5% level in both regressions, whether control variables were included or not, indicating that after considering the sequence correlation of HQDF, the role of green finance in promoting HQDF still exists. The previous conclusions are robust.

Table A5.

System GMM.

Table A5.

System GMM.

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| HQDF | HQDF | |

| L.HQDF | 1.2215 *** | 1.0960 *** |

| (81.4973) | (85.7035) | |

| green | 0.0698 ** | 0.1761 *** |

| (2.2478) | (3.0881) | |

| CV | No | Yes |

| _cons | −0.0717 *** | −0.1034 *** |

| (−5.6670) | (−5.6394) | |

| AR (1) | −3.98 [0.000] | −2.72 [0.006] |

| AR (2) | 0.11 [0.912] | 0.96 [0.338] |

| Hansen Test | 16.82 [0.856] | 19.25 [0.826] |

| Province fixed effect | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effect | Yes | Yes |

| N | 390 | 390 |

Notes: ***, **, indicate significance level at 1%, 5%, respectively, and the values in () represent t-statistics. CV denotes control variables. “L” in the table presents the first-order lag of the variables. The values in [] are p-values of the corresponding test statistics. The SYS-GMM estimation results show that all AR (2) have p-values greater than 0.1, indicating that no second-order autocorrelation exists for the difference term of the perturbation terms. The results of the Hansen test show that the selected instrumental variable is valid.

Appendix F. Regional Heterogeneity Analysis

Table A6 shows clear spatial differences. The role of green finance in promoting HQDF varies significantly across regions. In the western and southern regions, the promoting effect is most evident. The estimated coefficients are 1.1972 and 0.7744, both significant at the 1% or 5% level. This finding is consistent with the measurement analysis, which concludes that “the southern region has abundant forestry resources, a complete industrial chain, and prominent advantages in the ecological industrialization of the southwest.” (East China includes: Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Liaoning, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shandong, Guangdong and Hainan Province. Central China includes: Shanxi, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Anhui, Jiangxi, Henan, Hubei, Hunan. West China includes: Inner Mongolia, Guangxi, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia and Xinjiang.) The favourable natural conditions, supportive policies, and strong market demand in these regions jointly create strong synergies. Green finance there effectively promotes both industrial upgrading and ecological improvement. In the central region, the positive role of green finance is also evident (coefficient 0.5380), which reflects the recent success of ecological restoration and industrial-structure optimization policies. By contrast, the coefficients for the eastern and northern regions are negative and significant (−0.7520 and −0.3574). (North China includes: Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanxi, Inner Mongolia, Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Shandong, Henan, Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, Xinjiang. South China includes: Jiangsu, Anhui, Hubei, Chongqing, Sichuan, Yunnan, Guizhou, Hunan, Jiangxi, Guangxi, Guangdong, Fujian, Zhejiang, Shanghai, Hainan.)

Table A6.

Sub-regional regression results.

Table A6.

Sub-regional regression results.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| East China | Central China | West China | North China | South China | |

| green | −0.7520 * | 0.5380 ** | 1.1972 *** | −0.3574 *** | 0.7744 ** |

| (−1.8200) | (2.2786) | (5.0541) | (−2.9906) | (2.4822) | |

| CV | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| _cons | 0.7460 ** | −0.2219 | −0.3050 | 0.0043 | 0.5353 |

| (2.1598) | (−1.1524) | (−1.1674) | (0.0292) | (1.6178) | |

| Province fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 154 | 112 | 154 | 210 | 210 |

| r2_a | 0.7807 | 0.8741 | 0.8087 | 0.8721 | 0.6778 |

Notes: ***, **, and * indicate significance level at 1%, 5%, and 10% respectively, and the values in () represent t-statistics. r2_a is adjust R2. CV denotes control variables.

Appendix G. Heterogeneity Analysis of Green Financial Instruments