Abstract

The hydrological processes of red soil slope farmland are complex, and the vertical migration of nitrogen (N) is influenced by these processes, which present different layering characteristics of water flow. Previous studies on the vertically stratified transport of N on slope soils have mainly relied on rainfall simulation, lacking a comprehensive study of the overall process of N leaching from surface soil to underground under natural conditions. To investigate the impact of these hydrological processes on the transport of N at different layers under natural rainfall events, large-scale field runoff plots were constructed as draining lysimeters to conduct a consecutive 2-year observation experiment at Jiangxi Soil and Water Conservation Ecological Science and Technology Experimental Station, China. The runoff (the water of 0 cm), interflow, deep percolation, soil moisture content (SMC), total nitrogen (TN), nitrate nitrogen (NO3−-N) and ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N) concentrations were monitored and determined. The N loss of red soil farmland under two treatments, namely grass mulching (FC, a coverage of 100% with Bahia grass) and exposed treatment (BL, without anything covered), were measured. The relationships between hydrological factors and different forms of N losses were analyzed. The results indicate the following: (1) Deep percolation is the main pathway of water loss and N loss for red soil slope farmland, accounting for over 85% of the total water loss and N Loss. Grass mulching can significantly reduce surface runoff and N loss. (2) Vertically stratified N is mainly NO3−-N, and the concentrations of each form of N show the same trend: deep percolation > interflow > runoff. (3) Water loss, rainfall, and SMC are closely related to the stratified loss of N, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.74 to 0.98. The correlation analysis and redundancy analysis (RDA) on the relationships between different forms of N losses and hydrological factors indicate that rainfall was the primary factor driving the stratified loss of N in red soil slope farmland.

1. Introduction

Soil erosion is recognized as one of the major environmental problems in the hilly red soil region of Jiangxi province, southern China [1]. Nitrogen (N) is one of the important factors of soil fertility, which plays an important role in agricultural production [2]. In the hilly red soil region of southern China, slope farmland is an important land resource, and it is also the main source of soil and water loss. The N loss caused by rainfall erosion not only leads to a decrease in land productivity but also becomes the source of non-point source pollution [3]. Under the action of rainfall, nutrients from slope farmland can enter water through surface and deep percolation [4]. However, the existence of complex topography and diversified land uses can influence the relationship between rainfall and runoff, leading to corresponding changes in surface erosion [5,6,7,8].

The surface–soil–subsurface hydrological processes driving N transport are very complicated on the hilly red soil slope in southern China due to its special topography and diversified land uses [9,10]. The interaction characteristics between surface runoff and soil water movement processes are obvious. The migration of N occurs dynamically over time and space in association with surface runoff, sediment, and soil hydrological processes, and it is the result of the coupling effect of various processes such as surface runoff, soil water movement, and sediment transport. Vertical migration patterns of N are affected by these hydrological processes and exhibit different characteristics in the out-flow components (runoff: the process of surface water accumulating and flowing without infiltration; interflow: percolation in soil, which refers to the vertical infiltration or the flow along different soil layer interfaces; and deep percolation: when water seeps into the deeper soil and eventually replenishes groundwater). Generally speaking, deep percolation loss is the main pathway for N loss on red soil sloping farmland. The amount of nitrate nitrogen (NO3−-N) leaching increases with the increase in fertilizer application and precipitation. Ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N) is adsorbed by soil colloids and is not easily leached. Surface runoff is also a major pathway for N loss, and the main form of N loss is NO3−-N. Due to the existence of interflow, the hydrological process of red soil sloping farmland is relatively complex. The vertical migration form of N is affected by the hydrological process and presents different layered characteristics [11,12,13,14]. Currently, there is a lack of research on the vertical layered output patterns of surface runoff, interflow, and deep percolation under natural rainfall conditions. Therefore, elucidating the response of N stratified transport on red soil sloping farmland to soil hydrological processes can provide an important theoretical basis for controlling soil N runoff and leaching losses, which is beneficial for reducing N loss and preventing non-point source pollution from the sources in this region.

Organic mulch is an important agronomic measure which has been proven effective for soil and water conservation worldwide [15]. In recent years, many studies have been carried out to evaluate the effects of straw mulching on soil and water conservation, soil improvement, non-point source pollution control, organic carbon sequestration, and crop yield [16,17,18,19]. Although mulching can reduce the risk of nutrient loss from the surface [20,21], it is worth noting that some studies showed that mulching increases N leakage loss [22,23]. At present, there is a lack of experimental data for evaluating the effect of mulching on N transport on sloping farmland, and the changes in soil hydrological processes caused by vegetation cover need further study.

Rainfall is the main driving force of soil and water loss. It can directly strike the surface soil, causing both splash erosion and runoff [24]. Surface runoff, interflow, and deep percolation are all components of slope runoff, which have important effects on runoff generation and nutrient loss. Under rainfall, N can be transferred with surface runoff water or erosion sediment. It can also migrate vertically with infiltration of water [25]. Many studies have been conducted to investigate N loss from slope land with surface runoff [5,26,27,28]. However, most of studies only consider the surface loss of soil N without accounting for the leaching loss of soil N.

Soil water is the carrier of N runoff and leaching losses on farmland. Reducing water loss in various hydrological processes such as infiltration, transport, and redistribution of rain in soil has an impact on both soil erosion and N migration [29]. Most studies on N leaching loss are conducted through indoor experiments or field experimental observations without exploring the pollution load caused by N leaching loss on farmland, although the formation and transport of N leaching loss are closely related to soil hydrological processes.

At present, most existing studies on slope-stratified runoff generation, as affected by surface condition, cultivation measures, rainfall characteristics and fertilization method shave, mainly relied on artificial rainfall simulation methods [30,31,32]. There is a significant lack of research on the vertical stratified output patterns of runoff, interflow, and deep percolation under natural rainfall. Regarding the transfer of N, studies mainly focused on the ratio of N output through soil lateral loss to surface runoff and the ratio of surface runoff to soil lateral N flow under various environmental conditions [5,33]. In fact, there are two ways for N to migrate on the slope: one is being transported along surface runoff or eroded sediment, and the other is migrating vertically along the infiltrated water. The surface runoff and deep percolation processes in the red soil area are coupled with each other, which is bound to have a significant impact on the N loss pathways and the forms of N loss. Therefore, there are still several issues that need to be addressed. Firstly, under the coupling condition of surface runoff and deep infiltration, what are the main pathways for water and N loss? Secondly, what are the main forms of N loss? Thirdly, what are the impacts of hydrological factors such as rainfall, soil moisture, and flow paths on the stratified loss of N? Therefore, a comprehensive observation of N migration and transport at different layers under natural rainfall should be carried out to better understand N loss on slope farmland.

This study was carried out on red soil slope farmland at the Jiangxi Soil and Water Conservation Ecological Science and Technology Experimental Station, a national demonstration station of soil and water conservation, and a large soil lysimeter was used as part of the field observation. N transport at different layers on red soil slope farmland under rainfall conditions and the characteristics of different forms of N, such as NO3−-N, NH4+-N, and organic N (ON), in these soil hydrological processes were determined; the responses and mechanisms of different N forms to soil hydrological processes were discussed; and the effect of grass mulching on N transport were analyzed. The aims of this study were to (1) describe the runoff characteristics of red soil sloping farmland under natural rainfall conditions; (2) elucidate the output characteristics of N on red soil sloping farmland; and (3) explore the influence of soil hydrological processes on N loss, which could provide an in-depth understanding of the mechanism of N loss on hilly red soil slope farmland.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Area of Study

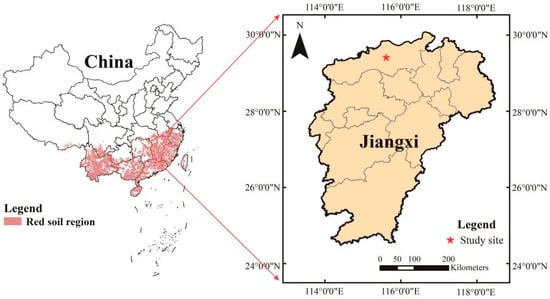

The experimental site is located in Jiangxi Soil and Water Conservation Ecological Science and Technology Experimental Station (115°42′38″~115°43′06″ E, 29°16′37″~29°17′40″ N) in De’an County, northern Jiangxi Province [34] (See Figure 1). The experimental site has a subtropical humid monsoon climate, with annual average precipitation of 1399 mm. The annual average temperature is 16.7 °C, and the highest monthly temperature occurs in July, while the lowest occurs in January. The annual average sunshine duration is 1650–2100 h, and the annual average frost-free period is 249 d. The rainy season occurs from April to September, during which >70% of the total rainfall occurs. The soil is red soil developed from quaternary red clay, and the soil pH is acidic to slightly acidic. The thickness of the local soil layer is approximately 105 cm. Below 105 cm, it is usually the base layer or a weakly permeable layer.

Figure 1.

The location of the study area.

2.2. The Rainfall Characteristics of Study Area in 2016 and 2017

In order to accurately study the runoff characteristics of red soil slope farmland under natural rainfall conditions, we chose seven rainfall events that occurred in 2016 and 2017. The rainfall data was measured using self-counting rain gauges. The rainfall characteristics of the experimental area in 2016 and 2017 are shown in Table 1. The total number of rainfall events in the experimental area in 2016 and 2017 was 136 and 124 events, respectively, lower than the average for the period from 2001 to 2017. The total rainfall in the experimental area in 2016 and 2017 was 1797.4 and 1839.6 mm, respectively, approximately 27% higher than the average for the past 17 years. The total rainfall duration in 2016 and 2017 was 61,225 and 6770 min, respectively, approximately 30% higher than the average for the past 17 years. The average rainfall intensity in 2016 and 2017 was 2.05 and 2.35, respectively, basically the same as the average for the past 17 years. By comparison, it can be seen that the rainfall in 2016 and 2017 was abundant, with no extreme rainstorm events, indicating that these two years were typical years for rainfall–runoff development.

Table 1.

The relevant rainfall data of study area in 2016 and 2017.

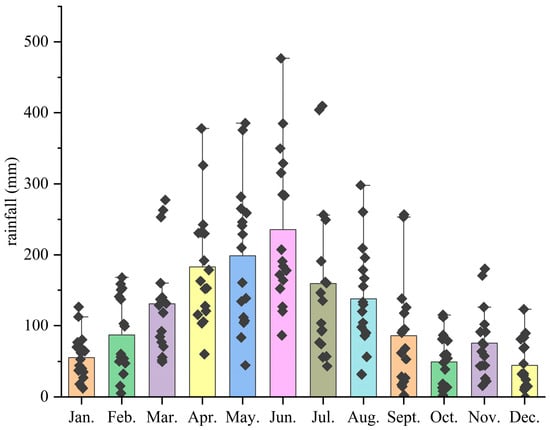

At the same time, in order to better observe and record the occurrence of runoff, we selected seven typical rainfall events in May 2016 and June 2017, and detailed information of these seven rainfall events is shown in Table 2. We compared the average rainfall in May 2016 and June 2017 with the average rainfall in the same months over the past 17 years (2001–2017) (see Figure 2) and found that the average rainfall in these two months was 28% and 102% higher, respectively, than the average rainfall in the same months over the past 17 years. This indicates that May 2016 and June 2017 are typical periods for observing runoff generation in the components of red soil slope farmland, as runoff is more likely to occur during these months.

Table 2.

The seven chosen rainfall events in 2016 and 2017.

Figure 2.

Average monthly rainfall from 2001 to 2017. Explanatory note: The black rhombuses represent the average monthly rainfall for different years.

2.3. Experimental Design and Treatments

To test the runoff, interflow, and deep percolation on the red soil with different land covers, large-scale field runoff plots were constructed by using draining lysimeters to conduct a consecutive 2-year (2016 and 2017 year) experiment. Two treatments (FC and BL) were conducted in this study. FC represents litter cover, obtained from mowing the Paspalum natatu with a coverage of 100% and a thickness of about 15 cm, and the litter cover layer was maintained every three months for the decade cover. BL represents bare land without anything covered, and weeding was performed every three months. Runoff, interflow, and deep percolation were collected at 4 depths (0, 30, 60, and 105 cm) in each of the plots. The plots are adjacent and have the same slope direction (14°). Each of the runoff plots was 5 m wide and 15 m long. At the bottom of the plots, a retaining wall was built to form a closed drainage collection system. The soil properties of BL are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Physical and chemical properties of the test soils.

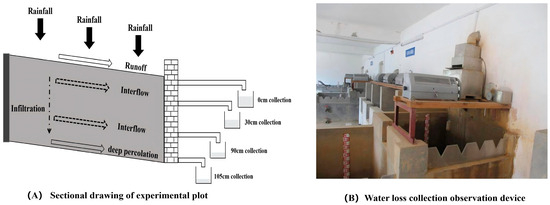

2.4. Plots and Equipment

At the bottom of the slope in the residential area, a total of 4 out-flow outlets are set from top to bottom to collect runoff and sediment. They are the 0 cm runoff outlet, the 30 cm and 60 cm interflow outlets, and the 105 cm deep percolation outlet (see Figure 3A). At the bottom of each outlet, there are grooves to enable the different layers of soil infiltration flow to be intercepted and converge to the out-flow outlet. The out-flow collection ponds were equipped with automatic recording water level meters to monitor the dynamic processes of runoff and drainage in real time. The surrounding area and the base plate of the test device are cast with reinforced concrete. A gravel filter layer is set on the floor. A trapezoidal reinforced concrete retaining wall is built at the foot of the slope, which is 30 cm higher than the ground surface to prevent water from entering or exiting the community, thereby forming a closed drainage soil infiltration device. The runoff volume is calculated based on the water level readings on the pool walls; the flow in different soil layers is read from the self-recording water level meters (see Figure 3B). After the runoff generation process is completed, samples are taken from the pool, and the N contents of various forms are analyzed. Among them, TN is determined using the alkaline potassium persulfate digestion-ultraviolet spectrophotometry method; NH4+-N is determined using the sodium salicylate spectrophotometry method; NO3−-N is determined using the sulfuric hydrazine reduction method; and ON is TN minus NH4+-N and NO3−-N. In addition, an automatic meteorological station is set up next to the plots to observe meteorological variables such as precipitation, temperature, and sunshine according to the requirements of national meteorological stations. We observed rainfall, surface runoff, interflow, and deep percolation of 7 typical rainfall events for two years (2016 and 2017).

Figure 3.

The overview of the experimental plot.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Experimental data were processed and analyzed using Excel 2020, SPSS 27.0 software and Origin 2021. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out to determine differences between the FC and BL treatments (n = 7). Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to explore the relationship between rainfall, water loss, SMC (soil moisture content), and different forms of N concentrations. Redundancy analysis (RDA) on the relationships between different N forms and environmental factors was conducted to reveal the impact of soil hydrological processes on N transport.

3. Results

3.1. The Out-Flow Components on Red Soil Sloping Farmland

The runoff, interflow, and deep percolation volumes of seven natural rainfall events in 2016 and 2017 were analyzed. As shown in Table 4 and Figure 3, the average runoff, interflow, and deep percolation volumes of red soil slope under BL are 462.8, 123.8, and 3502.6 L, respectively, and under FC, they are 97.5, 328.6, and 4487.0 L, respectively, for the 2-year experimental period. In general, deep percolation accounts for more than 85.7% of the total water loss. The contribution of surface flow to the total out-flow volume of the slope red soil is the smallest, accounting only for 2~11.3%. The flows at the 30 cm and 60 cm soil depths account for 3–6.7% of the total water loss. This indicates that deep percolation is the main pathway of water loss on red soil sloping farmland. By comparing the differences in each runoff component under the two measures, it can be seen that compared with BL, FC reduces the proportion of surface runoff but increases the risk of interflow and underground infiltration. This indicates that grass mulch can effectively prevent rainwater from directly eroding the soil surface and promote water infiltration.

Table 4.

The water losses (unit: L) under the BL and FC treatments during 7 rainfall events.

3.2. Nitrogen Transport at Different Soil Layers on Red Soil Slope Farmland

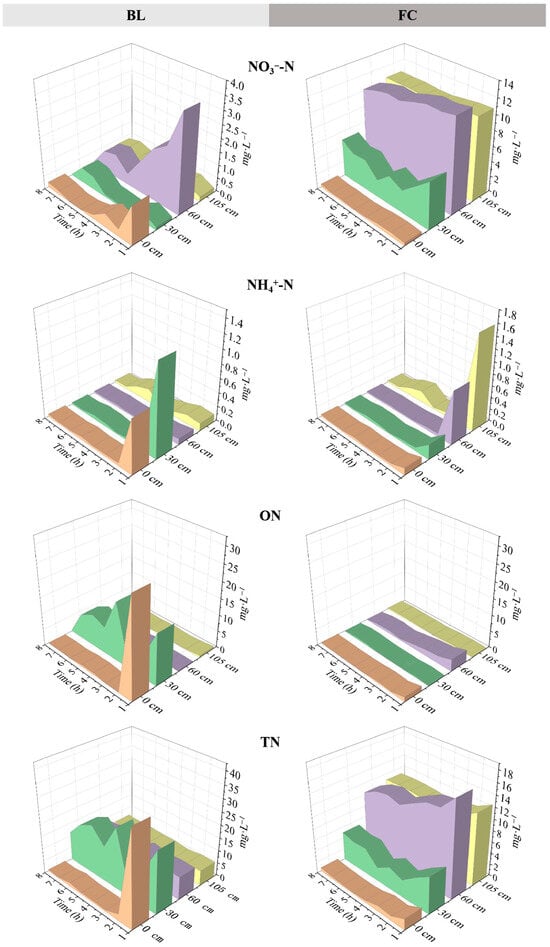

3.2.1. Changes in Different Forms of N Concentrations During a Single Rainfall Event

In order to further understand the rule of N loss on red soil sloping farmland, we measured the N content in different forms of each runoff component. To study the variation in N output with rainfall duration, we chose a typical rainfall event for our analysis. The concentration variations in different N forms in the out-flow water in July 2017 are shown in Figure 4. In general, the concentrations of NO3−-N and NH4+-N in each layer were relatively stable, indicating that they were less affected by rainfall duration. The concentrations of organic nitrogen (ON) and total nitrogen (TN) in runoff and shallow (30 cm) interflow gradually decreased from a high level to a stable value, indicating that ON was more easily lost in the early stages of rainfall and is the main form of N output. However, for the deeper interflow (60 cm) and deep percolation, the output concentrations of ON and TN were relatively stable, which indicates that the N output concentration was less affected in the deeper soil layers during a rainfall event. It is worth noting that, compared with BL, the concentrations of NO3−-N in groundwater infiltration under FC treatment is significantly higher than that in surface runoff. This might indicate that under heavy rain conditions, the litter cover can reduce surface runoff. While doing so, it also increases water infiltration, thereby altering the downward migration characteristics of NO3−-N.

Figure 4.

Changes in different forms of N concentrations with different out-flow components during a single rainfall event.

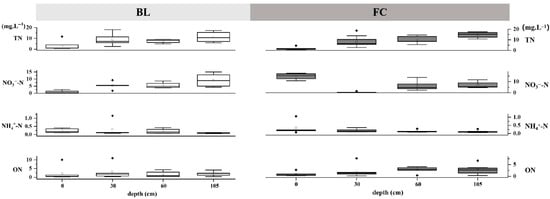

3.2.2. Characteristics of N Concentration Stratification Output with Different Forms of Runoff Components

In order to study the characteristics of N transport in different layers, we analyzed the different forms of N concentrations in runoff, interflow, and deep percolation from seven natural rainfall events in 2016 and 2017. To compare the difference in N output between BL and FC, a one-way analysis of variance was conducted (n = 7). The average concentrations of TN and NO3−-N in deep percolation of FC are about 40% higher than those of BL. In terms of each flow output component, the concentrations of different N forms showed the trend of deep percolation > interflow > runoff (See Figure 5). The results indicate that in addition to paying attention to the risk of N loss on the surface, we may also need to pay more attention to the risk of N loss and pollution of groundwater through interflow and deep percolation.

Figure 5.

Comparison of different forms of N concentrations in different out-flow components.

3.2.3. N Loss with Different Runoff Components

The total amounts of losses of different forms of N in the out-flow components for the seven natural rainfall events in 2016 and 2017 are shown in Table 5. The total N losses in the BL and FC treatments were 208.55 and 417.61 g, respectively. The total losses of NO3−-N, NH4+-N, and ON in BL were 156.09, 2.72, and 49.76 g, respectively. The total losses of NO3−-N, NH4+-N, and ON in FC were 319.64, 4.46, and 93.51 g, respectively. Overall, for the two treatments, the order of N loss in various forms was NO3−-N > ON > NH4+-N. It can be seen that under natural rainfall conditions, the main form of N loss on red soil slope farmland is NO3−-N.

Table 5.

N loss (unit: g) with different runoff components under 7 natural rainfall events.

3.3. The Correlation Analysis Between Soil Hydrological Processes and Stratified Transport of N

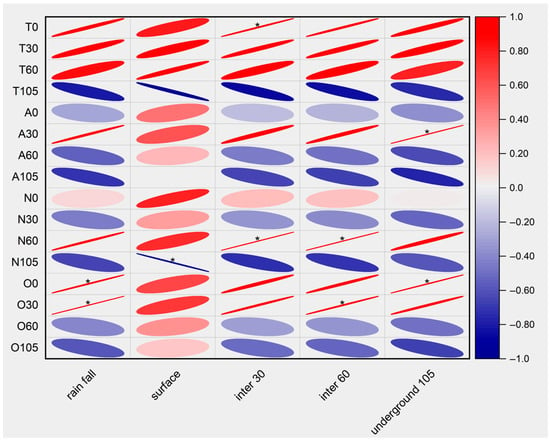

3.3.1. Correlation Between Soil Water, Rainfall, Runoff, and Different Forms of N Transport

In order to investigate the effect of soil hydrological processes on the stratified transport of N, correlation analyses between rainfall, runoff, and the losses of different forms of N were conducted. Overall, there was a significant correlation between rainfall, runoff, and N transport. The TN concentration of runoff was highly positively correlated with both rainfall and water loss, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.74 to 0.98. However, TN, NH4+-N, NO3−-N, and ON of deep percolation were negatively correlated with rainfall and runoff, with correlation coefficients ranging from −0.80 to −0.37 (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Correlation analysis between runoff and N transport. Explanatory note: The red ellipse represents a positive correlation, while the blue ellipse represents a negative correlation, and the darker the color, the larger the absolute value of the correlation coefficient. * indicates that there is a significant correlation between two factors (p < 0.05). T0, T30, T60, and T105 represent the concentrations of TN of runoff, interflow (30 cm), interflow (60 cm), and deep percolation, respectively. A0, A30, A60, and A105 represent the concentrations of NH4+-N of runoff, interflow (30 cm), interflow (60 cm), and deep percolation, respectively. N0, N30, N60, and N105 represent the concentrations of NO3−-N of runoff, interflow (30 cm), interflow (60 cm), and deep percolation, respectively. O0, O30, O60, and O105 represent the concentrations of ON of runoff, interflow (30 cm), interflow (60 cm), and deep percolation, respectively.

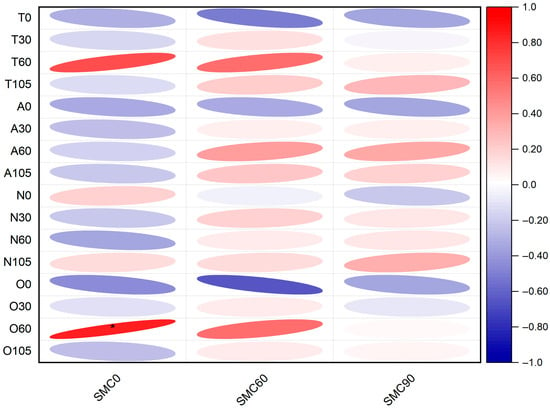

3.3.2. Correlation Between Soil Water and Different Forms of N Transport

SMC is closely related to the N transport process. In order to investigate the relationship between SMC and N output in the stratified transport, we installed soil moisture probes in the BL plot to automatically record soil moisture contents at depths of 30, 60, and 90 cm. Here, we analyzed the correlations between runoff N concentrations and SMC for the seven rainfall events in 2018 (see Figure 7). Our result indicates a close relationship between soil water content (SMC) and N transport. The correlation coefficient between the TN concentration in the 60 cm soil and the upper-layer SMC (30 cm and 60 cm depth) is relatively high, reaching 0.57~0.68. The TN concentration and NH4+-N concentration of surface runoff were negatively correlated with soil water content in each soil layer.

Figure 7.

Correlation analysis between SMC and N transport. Explanatory note: The red ellipse represents positive correlation, while the blue ellipse represents negative correlation, and the darker the color, the larger the absolute value of the correlation coefficient. * indicates that there is a significant correlation between two factors (p < 0.05). T0, T30, T60, and T105 represent the concentrations of TN of runoff, interflow (30 cm), interflow (60 cm), and deep percolation, respectively. A0, A30, A60, and A105 represent the concentrations of NH4+-N of runoff, interflow (30 cm), interflow (60 cm), and deep percolation, respectively. N0, N30, N60, and N105 represent the concentrations of NO3−-N of runoff, interflow (30 cm), interflow (60 cm), and deep percolation, respectively. O0, O30, O60, and O105 represent the concentrations of ON of runoff, interflow (30 cm), interflow (60 cm), and deep percolation, respectively.

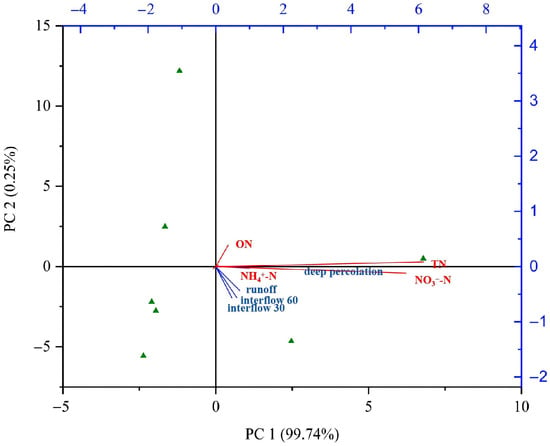

3.3.3. The Impact of Hydrological Processes on N Transport

Redundancy analysis (RDA) on the relationships between different forms of N losses and environmental factors was conducted to reveal the impact of hydrological processes on N transport. The result of the RDA revealed that the first and second components axes explained approximately 99.74% and 0.25% of the total variation in N loss, respectively (see Figure 8). RDA results suggest that rainfall and water loss (especially the surface runoff) are the main factors affecting the stratified transport of N.

Figure 8.

RDA on the relationships between different N forms and hydrological environmental factors. Explanatory note: Blue and red lines represent different forms of N loss and hydrological environmental factors, respectively. The green triangle represents 7 rainfall events. The length and angle of lines indicate relationships between different forms of N loss and environmental factors and principal component analysis (PCA) axes; n = 7.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Impact of Vegetation Cover on Water Loss Process

In general, the order of total water loss from the three out-flow components is FC > BL, that of runoff is BL > FC, that of interflow is FC > BL, and that of deep percolation is FC > BL. A one-way analysis of variance was conducted to further determine whether there is a significant difference in water loss at each layer between the two treatments. The result showed that grass mulching has a significant impact on the runoff process. Compared with FC, BL increased the total runoff volume, with the main increase being in deep percolation. This result is consistent with Shi’s study [35]. The mulching measures can reduce the evaporation of soil moisture and direct more water to the downward infiltration paths [16]. The mulching material can insulate heat, thereby reducing the evaporation of water on the soil surface. At the same time, the covering material can effectively absorb the impact force of raindrops and protect the aggregate structure of the soil surface [36]. This helps the soil to maintain a loose and porous state so that water can flow smoothly downward.

Moreover, the FC treatment decreased the proportion of runoff. Our result shows that soil and water conservation measures can promote the infiltration of surface water on the slope and increase the interflow. This is consistent with Guzha’s [37] study, which showed that mulching can decrease surface runoff. This is because mulching can effectively reduce the direct impact of raindrops on the soil surface, decrease soil dispersion by rain droplets, and reduce the formation of soil surface crust. On the other hand, mulching can also improve the formation and protection of soil aggregates, reducing soil particle detachment and runoff [38]. Our results suggest that the litter layer and soil humus layer are very important for water conservation.

4.2. The Impact of Vegetation Cover on the N Transport Process

4.2.1. The Changes in N Concentrations in the Out-Flow Components Under Natural Rainfall

The results show that grass mulching could significantly affect N loss in different soil layers. Overall, the fluctuations in different forms of N concentrations in the FC treatment were lower than those in the BL treatment. Under grass mulching, the fluctuations in TN, NO3−-N, and NH4+-N concentrations in the surface runoff of FC were significantly lower than those of the BL. This is mainly because the covering reduces the total flow rate and velocity of the surface gold slurry. Once the runoff occurs, as it flows through these obstacles, the flow velocity will significantly decrease. Meanwhile, the surface coverings maintain the moisture and looseness of the soil surface, which greatly enhances the soil’s infiltration capacity. In the BL treatment, there existed a significant variation in the concentration of NO3−-N in the surface runoff. The rapid decrease in the NO3−-N concentration with time during the rainfall event indicates that NO3−-N is most easily lost during the initial stage of runoff generation. This is because NO3−-N is a water-soluble N that cannot be adsorbed by the soil. Secondly, it is mainly concentrated in the soil surface layer. In the early stage of runoff generation, water can flush away the NO3−-N that has accumulated on the surface and is easily mobile first [39]. Our result indicates that grass mulching can effectively reduce N loss, especially in surface runoff. However, we also found that the concentrations of TN and NO3−-N in the deep percolation of the FC treatment were significantly higher than those of the BL treatment. This is attributed to the N input from the decomposition of the mulching material.

4.2.2. The Impact of Vegetation Cover on Stratified Transport of N

The results show that the FC treatment can significantly affect N output. Compared with the BL treatment, the concentrations of TN and nitrate nitrogen in each runoff component in FC significantly increased. This may be due to the decomposed N from in grass mulching. Our findings are similar to Jing’s research [33], who found that returning straw significantly reduced surface runoff but increased the risk of N loss through interflow and deep percolation. However, the N concentration differences in surface runoff and interflow were not obvious between the two treatments, similar to Wang et al. (2015) [40], who studied the effects of straw covering methods on runoff and found that mulch cover caused an increase in runoff flow depth and hydraulic roughness, resulting in a decrease in flow velocity. Overall, the concentration changes in N in surface runoff under grass cover are rather complex. On the one hand, the reduced runoff may have a “concentration effect” on NO3−-N; on the other hand, grass decomposition can release nutrients, which may increase the concentration in soil solution. Therefore, the impact on a single concentration indicator needs to be determined based on specific fertilization, rainfall, and management conditions.

Our results indicate that the main pathway for N transport is through deep percolation, but it is worth noting that the proportion of N output in the interflow is relatively high and cannot be ignored. In terms of different N forms in the same treatment, in the same out-flow component (runoff, interflow, or deep percolation), the concentration of NO3−-N was the highest, followed by ON, and the content of NH4+-N was the lowest. Our results were consistent with Liu’s (2014) [41] study, which indicated that dissolved N was the predominant form of N loss. This is because NO3−-N has strong mobility, while NH4+-N has strong adsorption capacity. Therefore, the concentration of NH4+-N is close to the soil background value.

4.3. Characteristics of N Loss in the Out-Flow Components

The losses of different forms of N vary greatly among the out-flow components. In general, N loss (all forms of N combined) at the 105 cm layer accounted for 66.8~94.5% of the total N loss, indicating that deep percolation is the main pathway of N loss. Song et. al. (2017) [42] studied N loss from a karst area in China, and they also found that N loss mainly occurred through the subsurface. The largest amount of N loss was due to deep percolation because it is the largest out-flow component. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that the total N loss from surface runoff in the FC treatment is nearly 42 times lower than that in the BL treatment. This may be because the covering material provides abundant “food” (carbon source) for soil microorganisms. When microorganisms decompose these organic substances, they need to absorb a large amount of nitrogen to build their own cells. This process temporarily fixes inorganic nitrogen (such as NO3−-N) into ON (in the form of the microorganism’s body), thereby reducing the risk of it being washed away or carried away by runoff in the short term. In addition, under the BL treatment, the losses of NH4+-N and ON in runoff were slightly higher than that of interflow. Under the FC condition, the loss of each form of N in runoff is tens of times lower than that in the interflow. This may be due to the change in the soil hydrological process of slope farmland by mulching, which greatly reduces runoff and increases subsurface soil water movement [43,44].

4.4. The Influence of Soil Hydrological Processes on the Stratified Transport of N

4.4.1. The Correlation Between Rainfall, Runoff, Soil Water and Different Forms of N

Our findings are consistent with Xing’s study [45], which suggested that increasing rainfall intensity generally increased water loss. This may be related to surface erosion and the fact that runoff in the red soil region is dominated by surface water accumulation and runoff production [46]. More intensive rainfall can enforce the erosion effect, facilitating more soil particles and N (including granular and dissolved) transport with surface runoff [47]. When the interflow and deep percolation are both higher, greater runoff can also be expected, and more N in the soil will overflow and migrate to runoff [48,49]. Our results indicate that there was a negative correlation between TN, NH4+-N, NO3−-N, and ON of deep percolation and runoff. This may be due to the limited ability of soil to release N [50]. However, when the runoff flow increased, N would be diluted or excreted from the soil surface and soil profile. In addition to the flow in the 30 cm soil layer and its NO3−-N concentration, each runoff component has a certain correlation with their respective N concentration, indicating that each out-flow component has a significant effect on its N concentration.

There was a positive correlation between the TN concentration in the 60 cm soil layer and the upper-layer SMC (30 cm and 60 cm depth), indicating that the increase in the upper-layer soil water content can lead to the increase in the TN concentration in the 60 cm depth soil. The TN concentrations and NH4+-N concentrations of the runoff water were negatively correlated with the soil water content in each soil layer, indicating that the TN concentrations and NH4+-N concentrations of the runoff water decreased with the increase in SMC in each layer. Significant positive correlations between SMC and NH4+-N, TN, and NO3−-N were observed. This is attributed to the fact that the N mineralization process is closely related to SMC. Studies have shown that there is a significant positive correlation between SMC and N nitrification within a certain range [51,52]. When the SMC is below a certain value, nitrification is inhibited.

4.4.2. The Main Factors of the Stratified Transport of N

Redundancy analysis (RDA) showed that TN and NO3−-N losses were markedly influenced by rainfall. The loss of N during rainfall was mainly reflected in interflow and deep percolation. Under rainstorm conditions, raindrop splash can generate large surface runoff, and soil particles in the runoff can carry a large amount of nutrients, including N, causing N loss [53]. These results also indicate that surface runoff is also related to N loss, which agrees with a prior study indicating that the main pathway for N loss in croplands is runoff [54]. Overall, rainfall serves as the core driving force for nitrogen transfer from farmland to water bodies by generating surface runoff. This paper initially explored the influence of soil hydrological factors on N loss.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated different forms of N losses in out-flow components under natural rainfall events. The stratified water and N transport characteristics under exposed (BL) and covered (FC) treatments were observed, and comprehensive statistical analyses were conducted to investigate the impact of hydrological processes on water and N losses. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- The order of water loss volume for each component in the BL treatment is deep percolation > runoff > interflow, and in FC, it is deep percolation > interflow > runoff. The proportions of interflow and deep percolation in the total water loss under FC is much higher than that of BL. Grass mulching can significantly reduce the generation of surface runoff and increase water infiltration, consequently reducing the generation of surface runoff.

- (2)

- In both BL and FC treatments, the ranking of different forms of N concentrations of each layer was NO3−-N > ON > NH4+-N, and the concentration of each form of N showed a trend of deep percolation > interflow > runoff. Compared with BL, TN and NO3−-N concentrations under the FC treatment in deep percolation were significantly higher.

- (3)

- The main pathway for N loss on red soil slope farmland is deep percolation. Grass mulching can significantly reduce the loss of N in surface runoff. The findings of this study suggest that rainfall was the primary factor affecting N transport on red soil slope farmland.

The transport of N is influenced by many factors. This article only explores the impact of soil hydrological processes on the transport of N. In future research, it is necessary to comprehensively consider the effects of fertilizer use, water conservation measures, and soil properties and establish a complete structural equation model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.; Investigation, M.M.; Resources, A.T. and J.W.; Writing—original draft, F.Z. and Z.L.; Writing—review & editing, F.Z. and Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42067020), the Major Discipline Academic and Technical Leaders Training Program of Jiangxi Province (20225BCJ23005), Key R&D Program of Jiangxi Province, China (20252BCF320022), the Science and Technology Project of Jiangxi Provincial Department of Water Resources (202527ZDKT12, 202325ZDKT02).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BL | without anything covered |

| FC | mulching dry Bahia grass with 100% coverage |

| TN | total nitrogen |

| AN | ammoniacal nitrogen |

| NN | nitrate nitrogen |

| NH4+-N | ammoniacal nitrogen |

| NO3−-N | nitrate nitrogen |

| ON | organic nitrogen |

| SMC | soil moisture content |

| T0 | the concentration of TN of runoff |

| T30 | the concentration of TN of interflow (30 cm) |

| T60 | the concentration of TN of interflow (60 cm) |

| T105 | the concentration of TN of deep percolation |

| N0 | the concentration of NO3−-N of runoff |

| N30 | the concentration of NO3−-N of interflow (30 cm) |

| N60 | the concentration of NO3−-N of interflow (60 cm) |

| N105 | the concentration of NO3−-N of deep percolation |

| A0 | the concentration of NH4+-N of runoff |

| A30 | the concentration of NH4+-N of interflow (30 cm) |

| A60 | the concentration of NH4+-N of interflow (60 cm) |

| A105 | the concentration of NH4+-N of deep percolation |

| O0 | the concentration of ON of runoff |

| O30 | the concentration of ON of interflow (30 cm) |

| O60 | the concentration of ON of interflow (60 cm) |

| O105 | the concentration of ON of deep percolation |

References

- Mo, M.M.; Liu, Z.; Yang, J.; Song, Y.; Tu, A.G.; Liao, K.; Zhang, J. Water and sediment runoff and soil moisture response to grass cover in sloping citrus land, Southern China. Soil Water Res. 2019, 14, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzebisz, W.; Diatta, J.; Barłóg, P.; Biber, M.; Potarzycki, J.; Łukowiak, R.; Przygocka-Cyna, K.; Szczepaniak, W. Soil Fertility Clock—Crop Rotation as a Paradigm in Nitrogen Fertilizer Productivity Control. Plants 2022, 11, 2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Su, Z.; Fu, Y.; Li, J.; Mao, D.; Wang, S. Distribution of Subsurface Nitrogen and Phosphorus from Different Irrigation Methods in a Maize Field. Hydrology 2024, 11, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitterson, J.; Knightes, C.; Parmar, R.; Wolfe, K.; Avant, B.; Muche, M. An overview of rainfall-runoff model types. In Proceedings of the 9th International Congress on Environmental Modelling and Software, Ft. Collins, CO, USA, 24–28 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K.A.; Jackson, D.R.; Pepper, T.J. Nutrient losses by surface run-off following the application of organic manures to arable land. 1. Nitrogen. Environ. Pollut. 2001, 112, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Zhu, B. Nitrate loss via overland flow and interflow from a sloped farmland in the hilly area of purple soil, China. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2011, 90, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, L.; Peng, X. Hydrologic separation and their contributions to N loss in an agricultural catchment in hilly red soil region. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2019, 62, 1730–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, H.; Ren, X.; Lu, J.; Chen, Z.Y.; Liu, X.W.; Wang, G.; Li, L.S. Nitrogen loss on red soil in south China under artificial rainfall conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 39, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, J.; Wang, F.; Tian, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, N. Hydrological connectivity affects nitrogen migration and retention in the land–river continuum. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 326, 116816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Long, Y.; Li, T.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, G.; Peng, B.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y. Nitrogen dynamic transport processes shaped by watershed hydrological functional connectivity. J. Hydrol. 2024, 645, 132218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, T.; Li, P.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Deng, W. Runoff velocity controls soil nitrogen leaching in subtropical restored forest in southern China. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 548, 121412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Miao, Q.; Wei, Z.; Guo, Y.; Li, J.; Fan, Z.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Sun, J.; Cui, Z. Nutrient runoff and leaching under various fertilizer treatments and pedogeographic conditions: A case study in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) fields of the Erhai Lake basin, China. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 156, 127170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wu, X.; Xiao, H.; Toan, N.-S.; Liao, B.; Wu, X.; Hu, R. Leaching is the main pathway of nitrogen loss from a citrus orchard in Central China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 356, 108559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Xiao, W.; Huang, Z.; Zeng, L. Interflow pattern govern nitrogen loss from tea orchard slopes in response to rainfall pattern in Three Gorges Reservoir Area. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 269, 107684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, Q.; Pan, L. Review of organic mulching effects on soil and water loss. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2021, 67, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Beltagi, H.S.; Basit, A.; Mohamed, H.I.; Ali, I.; Ullah, S.; Kamel, E.A.R.; Shalaby, T.A.; Ramadan, K.M.A.; Alkhateeb, A.A.; Ghazzawy, H.S. Mulching as a sustainable water and soil saving practice in agriculture: A review. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yu, K.; Feng, H. Effects of straw mulching and plastic film mulching on improving soil organic carbon and nitrogen fractions, crop yield and water use efficiency in the Loess Plateau, China. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 201, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, K.; Wang, W.; Khan, A.; Ren, G.; Zaheer, S.; Sial, T.A.; Yang, G. Straw mulching with fertilizer nitrogen: An approach for improving crop yield, soil nutrients and enzyme activities. Soil Use Manag. 2019, 35, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantalice, J.R.B.; Silveira, F.P.M.; Singh, V.P.; Silva, Y.J.A.B.; Cavalcante, D.M.; Gomes, C. Interrill erosion and roughness parameters of vegetation in rangelands. Catena 2017, 148, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Duan, J.; Peng, L.; Zhang, X.; Guo, X.; Yang, J. Effects of straw mulching on near-surface hydrological process and soil loss in slope farmland of red Soil. Water 2022, 14, 3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekalu, K.O.; Olorunfemi, I.A.; Osunbitan, J.A. Grass mulching effect on infiltration, surface runoff and soil loss of three agricultural soils in Nigeria. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 912–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, E.W.; Williams, M.W.; Caine, N. Landscape controls on organic and inorganic nitrogen leaching across an alpine/subalpine ecotone, Green Lakes Valley. Ecosystems 2003, 6, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, O.; Oshunsanya, S.O.; Are, K. Effects of vetiver grass (Vetiveria nigritana) strips, vetiver grass mulch and an organomineral fertilizer on soil, water and nutrient losses and maize (Zea mays L.) yields. Soil Tillage Res. 2007, 96, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.; Cornelis, W.M.; Gabriels, D.; Schiettecatte, W.; De Neve, S.; Lu, J.; Harmann, R. Soil management effects on runoff and soil loss from field rainfall simulation. Catena 2008, 75, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, H.; Wang, A.; Gurmesa, G.A.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Fang, Y. Transformation mechanisms of ammonium and nitrate in subsurface wastewater infiltration system: Implication for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Water Res. 2024, 250, 121031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.H.; Li, S.X. Nitrate N loss by leaching and surface runoff in agricultural land: A global issue (a review). Adv. Agron. 2019, 156, 159–217. [Google Scholar]

- Schuman, G.E.; Burwell, R.E.; Piest, R.F.; Spomer, R.G. Nitrogen losses in surface runoff from agricultural watersheds on Missouri Valley loess American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, and Soil Science Society of America. J. Environ. Qual. 1973, 2, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, J.A. Quantifying the loss mechanisms of nitrogen. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2002, 57, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Wu, J.; Wang, D.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Y.; He, X. Moisture movement, soil salt migration, and nitrogen transformation under different irrigation conditions: Field experimental research. Chemosphere 2022, 300, 134569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Min, J.; Kronzucker, H.J.; Li, Y.; Shi, W. N and P runoff losses in China’s vegetable production systems: Loss characteristics, impact, and management practices. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 663, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin-Hu, L.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, G.H.; Wang, B. Effects of Bahia grass cover and mulch on runoff and sediment yield of sloping red soil in southern China. Pedosphere 2011, 21, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, Y.; Haijin, Z.; Xiaoan, C.; Le, S. Effects of tillage practices on nutrient loss and soybean growth in red-soil slope farmland. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2013, 1, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Li, L.; Chen, S.; Shi, Y.; Xu, M.; Zhang, Q. Straw returning on sloping farmland reduces the soil and water loss via surface flow but increases the nitrogen loss via interflow. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 339, 108154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Liu, Z.; Han, X.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, G.; Mo, M. Effects of ridge tillage and peanut growth on the surface–subsurface runoff generation and soil loss in the red soil sloping farmland of southern China. J. Soils Sediments 2024, 24, 1431–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Li, P.; Li, Z.; Sun, J.; Wang, D.; Min, Z. Effects of grass vegetation coverage and position on runoff and sediment yields on the slope of Loess Plateau, China. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 259, 107231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, P.; Jia, Z. Long-term effects of plastic mulching on soil structure, organic carbon and yield of rainfed maize. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 287, 108447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzha, A.C.; Rufino, M.C.; Okoth, S.; Jacobs, S.; Nóbrega, R.L. Impacts of land use and land cover change on surface runoff, discharge and low flows: Evidence from East Africa. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2018, 15, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordán, A.; Zavala, L.M.; Gil, J. Effects of mulching on soil physical properties and runoff under semi-arid conditions in southern Spain. Catena 2010, 81, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, X.; Wang, T.; Cai, K.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Lu, L.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, Y. Characterization and source apportionment of rainfall-driven nitrate export from dryland crop systems with agricultural practices at mid-high latitudes. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 375, 109218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Hao, M.; Li, J. Effects of straw covering methods on runoff and soil erosion in summer maize field on the Loess Plateau of China. Plant Soil Environ. 2015, 61, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wang, J.; Shi, J.; Chen, Y.; Sun, C.; Zhang, P.; Shen, Z. Runoff characteristics and nutrient loss mechanism from plain farmland under simulated rainfall conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 468, 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Gao, Y.; Green, S.M.; Dungait, J.A.; Peng, T.; Quine, T.A.; He, N. Nitrogen loss from karst area in China in recent 50 years: An in-situ simulated rainfall experiment’s assessment. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 10131–10142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R. Study on Environmental Effects of Different Covering Measures on Spring Maize Planting in the Loess Plateau. In IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 384, 012158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, F.L.; Crouch, T.D.; Stallard, R.F.; Hall, J.S. Effect of land cover and use on dry season river runoff, runoff efficiency, and peak storm runoff in the seasonal tropics of Central Panama. Water Resour. Res. 2013, 49, 8443–8462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Yang, P.; Ren, S.; Ao, C.; Li, X.; Gao, W. Slope length effects on processes of total nitrogen loss under simulated rainfall. Catena 2016, 139, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Li, D.; Zhuo, M.; Guo, T.; Liao, Y.; Xie, Z. Effects of rainfall intensity and slope gradient on erosion characteristics of the red soil slope. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2015, 29, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinman, P.J.; Srinivasan, M.S.; Dell, C.J.; Schmidt, J.P.; Sharpley, A.N.; Bryant, R.B. Role of rainfall intensity and hydrology in nutrient transport via surface runoff. J. Environ. Qual. 2006, 35, 1248–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Yang, J.; Tang, C.; Zheng, T.; Li, L. Effects of rainfall intensity and slope on surface and subsurface runoff in red soil slope farmland. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2017, 33, 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, D.; Cheng, S.; Huang, X. Combined effects of runoff and soil erodibility on available nitrogen losses from sloping farmland affected by agricultural practices. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 176, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.L.; Alva, A.K. Ammonium adsorption and desorption in sandy soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2000, 64, 1669–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, K.I.; Polglase, P.J.; O’connell, A.M.; Carlyle, J.C.; Smethurst, P.J.; Khanna, P.K. Defining the relation between soil water content and net nitrogen mineralization. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2003, 54, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Guo, X. Evaluating soil water and nitrogen transport, nitrate leaching and soil nitrogen concentration uniformity under sprinkler irrigation and fertigation using numerical simulation. J. Hydrol. 2025, 647, 132345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, H.; She, D.; Li, P.; Lang, M.; Xia, Y. High-frequency monitoring during rainstorm events reveals nitrogen sources and transport in a rural catchment. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 362, 121308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, H.; Yao, M.; Zhou, J.; Wu, K.; Hu, M.; Chen, D. Estimation of nitrogen runoff loss from croplands in the Yangtze River Basin: A meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 272, 116001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).