Corporate Sustainability in the Coffee Industry: Organic Certification for Small Producers in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

- “organic coffee” AND “sustainability”;

- “coffee” AND “income” AND “small producers”;

- “organic certification” AND “forest reserves”;

- “coffee production” AND “Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta”;

- “voluntary sustainability standards” AND “coffee”;

- “organic vs. conventional coffee” AND “productivity”.

3. The Coffee Production Process

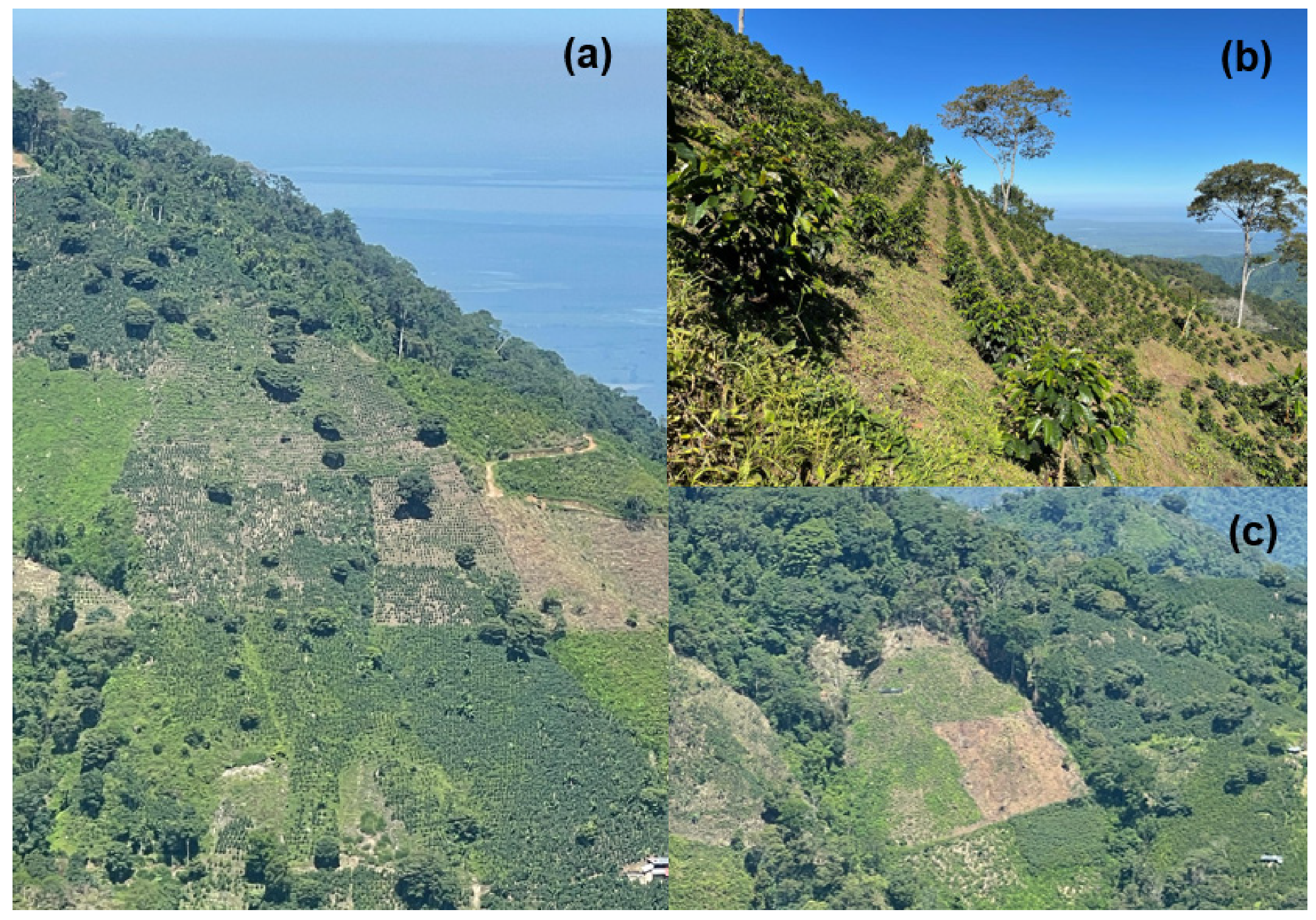

3.1. Environmental Conditions

3.2. Meteorological and Latitudinal Conditions

3.3. Coffee Varieties in Colombia

3.4. Production Stages and Maintenance of Coffee Farms

3.5. Coffee Production in Colombia

4. Corporate Sustainability in the Coffee Industry

4.1. Environmental Impacts of Coffee Production

| Stage | Coffee Production Process | Environmental Impact | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Preparation of land | Soil erosion and degradation, deforestation, expansion of agricultural frontiers, reduction in riparian and protected areas, loss of biodiversity, soil and water contamination by pesticides, and greenhouse gases emission. | [2,75,76] |

| 2 | Creation of germinators and seedbeds | Solid waste generation due to high plastic bag volumes, deforestation of bamboo and timber trees due to the construction of germinators and seedbeds, and soil and water contamination with pesticides and fertilizers. | [77,78] |

| 3 | Sowing stage | Soil erosion, water and soil pollution by pesticides and fertilizers that release byproducts and heavy metals into the environment, and solid waste generation. | [77,78] |

| 4 | Maintenance of plantations | Soil erosion and degradation due to coffee monoculture, water and soil pollution from pesticides and fertilizers, solid waste generation, and loss of biodiversity. | [2,75,79] |

| 5 | Fruit harvesting | Solid waste generation and if harvesting machines are used, soil compaction and greenhouse gas emissions occur. | [77,80,81] |

| 6 | Pulping and washing | Contamination of water sources by liquid discharges laden with organic matter (sewage), solid waste generation, contamination of soil and water by leachate, air pollution from engine combustion and electricity consumption. | [79,82,83] |

| 7 | Drying of the parchment coffee | Air pollution from particulate matter and exhaust gas emissions when using silos for coffee drying. Electricity consumption and solid waste generation. | [77,79] |

| 8 | Threshed, roasted, and ground for consumption | Air pollution from engine combustion, electricity consumption, particulate matter, and exhaust gas emissions from mills and roasters. Solid waste generation. | [8,84] |

4.2. Sustainability of Small Producers

- The economic dimension (Profit) focuses on ensuring long-term business profitability for small producers and enhancing the efficiency of production systems within a value chain that maximizes profitability with minimum production costs [95]. It also aims to position a competitive company across national and international markets.

- The social dimension (People) is based on the company’s responsibility for the well-being of society and its employees, promoting fair labor practices, and respect for human rights [96]. This dimension aims to guarantee minimum incomes that allow small producers to have an excellent quality of life and meet their basic needs.

- The environmental dimension (Planet) aims to conserve natural resources in productive systems and their surroundings by reducing pollution and environmental impact. It also aims to promote the efficient use of resources, protection of diversity, and adaptation to climate change, among other aspects [97].

4.3. Corporate Sustainability Models for Coffee Production

- Optimal management of natural resources such as water, energy, and materials.

- Implementation of pollution control processes at source.

- Implementation of a clear and defined product lifecycle.

- Implementation of solid circular economic processes.

- Development of open processes for social evaluation to obtain sustainable certification seals.

5. Organic Coffee Certification: Challenges and Opportunities

5.1. Organic Certification and Sustainability

- Protection of endemic biodiversity.

- Use of organic fertilizers, including coffee waste and other products derived from local composting of production units.

- Deployment of physical or biological controls as a substitute for chemical pesticides.

- Protection of water sources and soils.

- Low waste generation and proper management.

- Fair trade.

- Elimination of child labor.

- Best market prices.

- Market diversification and purchase guarantee.

5.2. Challenges in Organic Production: Economic, Social, and Environmental Risks

- Increased participation of large producers in organic production with strong economic capacity to sustain organic certification and production processes.

5.3. Opportunities for Improvement in the Organic Sustainability Model

5.3.1. Sustainable Certification

5.3.2. Price Surcharge Guarantee and Financial Support

5.3.3. Reducing Certification Costs

5.3.4. Compensating the Production Gap

5.3.5. Added Value and Real Price Premiums

5.3.6. Investment in Resilient Coffee Varieties

5.3.7. Diversification of Income Sources

6. Implications and Future Research Lines

7. Limitations of This Study

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VSS | Voluntary Sustainability Standards |

| SNSM | Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta |

| FNC | National Federation of Coffee Growers of Colombia (Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia) |

| GPD | Gross domestic product |

| USD | United States dollar |

| COP | Colombian peso |

| FiBL | Research Institute of Organic Agriculture |

| NYSE | New York Stock Exchange |

References

- Quiñones-Ruiz, X.F. Social Brokerage: Encounters between Colombian Coffee Producers and Austrian Buyers—A Research-Based Relational Pathway. Geoforum 2021, 123, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holle, M.J.M.; Apriyani, V.; Mumbunan, S. Systematic Evidence Map of Coffee Agroecosystem Management and Biodiversity Linkages in Producing Countries. Clean. Circ. Bioecon. 2025, 11, 100147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, Q.; Brooks, M.S.-L.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V. Innovative Technologies Used to Convert Spent Coffee Grounds into New Food Ingredients: Opportunities, Challenges, and Prospects. Future Foods 2023, 8, 100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloso, T.G.R.; da Silva, M.d.C.S.; Moreira, T.R.; da Luz, J.M.R.; Moreli, A.P.; Kasuya, M.C.M.; Pereira, L.L. Microbiomes Associated with Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora in Four Different Floristic Domains of Brazil. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadigi, R.M.J.; Robinson, E.; Szabo, S.; Kangile, J.; Mgeni, C.P.; De Maria, M.; Tsusaka, T.; Nhau, B. Revisiting the Solow-Swan Model of Income Convergence in the Context of Coffee Producing and Re-Exporting Countries in the World. Sustain. Futures 2022, 4, 100082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilen, C.; El Chami, D.; Mereu, V.; Trabucco, A.; Marras, S.; Spano, D. A Systematic Review on the Impacts of Climate Change on Coffee Agrosystems. Plants 2023, 12, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngure, G.M.; Watanabe, K.N. Coffee Sustainability: Leveraging Collaborative Breeding for Variety Improvement. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1431849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosalvitr, P.; Cuéllar-Franca, R.M.; Smith, R.; Azapagic, A. An Environmental and Economic Sustainability Assessment of Coffee Production in the UK. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 465, 142793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO Manual del Café Arábico para la República Democrática Popular Lao. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/ae939e/ae939e03.htm (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Magalhães Júnior, A.I.; de Carvalho Neto, D.P.; de Melo Pereira, G.V.; da Silva Vale, A.; Medina, J.D.C.; de Carvalho, J.C.; Soccol, C.R. A Critical Techno-Economic Analysis of Coffee Processing Utilizing a Modern Fermentation System: Implications for Specialty Coffee Production. Food Bioprod. Process. 2021, 125, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irawan, A.; McLellan, B.C. A Comparison of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Andungsari Arabica Coffee Processing Technologies towards Lower Environmental Impact. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 447, 141561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navichoc, D.; Alamneh, M.; Mortara Batistic, P.; Dietz, T.; Kilian, B. Voluntary Sustainability Standards and Technical Efficiency of Honduran Smallholder Coffee Producers. World Dev. Perspect. 2024, 36, 100637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga, S.; Suárez, C.; Solís, J.D. Exploring Coffee Farmers’ Awareness about Climate Change and Water Needs: Smallholders’ Perceptions of Adaptive Capacity. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 45, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, V.; García-Barrios, L.; Sterling, E.J.; West, P.; Meza-Jiménez, A.; Naeem, S. Smallholder Response to Environmental Change: Impacts of Coffee Leaf Rust in a Forest Frontier in Mexico. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abera, W.; Tamene, L.; Kassawmar, T.; Mulatu, K.; Kassa, H.; Verchot, L.; Quintero, M. Impacts of Land Use and Land Cover Dynamics on Ecosystem Services in the Yayo Coffee Forest Biosphere Reserve, Southwestern Ethiopia. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 50, 101338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis dos Santos Bastos, T.; Anjos Bittencourt Barreto-Garcia, P.; de Carvalho Mendes, I.; Henrique Marques Monroe, P.; Ferreira de Carvalho, F. Response of Soil Microbial Biomass and Enzyme Activity in Coffee-Based Agroforestry Systems in a High-Altitude Tropical Climate Region of Brazil. CATENA 2023, 230, 107270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dröge, S.; Verbist, B.; Maertens, M.; Muys, B. Do Voluntary Sustainability Standards Reduce Primary Forest Loss? A Global Analysis for Food Commodities. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 374, 109158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siles, P.; Cerdán, C.R.; Staver, C. Smallholder Coffee in the Global Economy—A Framework to Explore Transformation Alternatives of Traditional Agroforestry for Greater Economic, Ecological, and Livelihood Viability. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 808207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoz, J.V.D.L. Aroma de café: Economía y empresas cafeteras en la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. Jangwa Pana 2019, 18, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berihun, T.; Gutema, P. The Economic Impact of Sustainability Standards on Smallholder Coffee Producers: Evidence from Ethiopia. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2025, 55, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.P.; Ribeiro, P.C.C.; Rodrigues, L.B. Sustainability Assessment of Coffee Production in Brazil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 11099–11118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto Peixoto, J.A.; Silva, J.F.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P.; Alves, R.C. Sustainability Issues along the Coffee Chain: From the Field to the Cup. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 287–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nab, C.; Maslin, M. Life Cycle Assessment Synthesis of the Carbon Footprint of Arabica Coffee: Case Study of Brazil and Vietnam Conventional and Sustainable Coffee Production and Export to the United Kingdom. Geo Geogr. Environ. 2020, 7, e00096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C.A.; Pritts, A.A.; Zwetsloot, M.J.; Jansen, K.; Pulleman, M.M.; Armbrecht, I.; Avelino, J.; Barrera, J.F.; Bunn, C.; García, J.H.; et al. Transformation of Coffee-Growing Landscapes across Latin America. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 41, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes Martins, K.; Teixeira, D.; de Oliveira Corrêa, R. Gains in Sustainability Using Voluntary Sustainability Standards: A Systematic Review. Clean. Logist. Supply Chain 2022, 5, 100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Jovel, K. Coffee Production Networks in Costa Rica and Colombia: A Systems Analysis on Voluntary Sustainability Standards and Impacts at the Local Level. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 445, 141196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Jovel, K. The Voluntary Sustainability Standards and Their Contribution towards the Achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals: A Systematic Review on the Coffee Sector. J. Int. Dev. 2023, 35, 1013–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Jovel, K.; Sellare, J.; Damm, Y.; Dietz, T. SDGs Trade-Offs Associated with Voluntary Sustainability Standards: A Case Study from the Coffee Sector in Costa Rica. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 917–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Ortiz, M.M.; Vivares Vergara, J.A. Organic Coffee Production: Mapping Trends through Bibliometric Analysis. CLIO América 2024, 18, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tey, Y.S.; Rajendran, N.; Brindal, M.; Sidique, S.F.A.; Shamsudin, M.N.; Radam, A.; Hadi, A.H.I.A. A Review of an International Sustainability Standard (GlobalGAP) and Its Local Replica (MyGAP). Outlook Agric. 2016, 45, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L.F.G.; Gardner, T.; McDermott, C.L.; Ayub, K.O.L. Group Certification Supports an Increase in the Diversity of Sustainable Agriculture Network–Rainforest Alliance Certified Coffee Producers in Brazil. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 107, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renard, M.-C. Values and the Making of Standards in ‘Sustainable’ Coffee Networks: The Case of 4C and Nestlé in México. Int. Sociol. 2022, 37, 758–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renard, M.-C. In the Name of Conservation: CAFE Practices and Fair Trade in Mexico. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 92, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, G.; Pilbeam, C.; Wilding, R. Nestlé Nespresso AAA Sustainable Quality Program: An Investigation into the Governance Dynamics in a Multi-stakeholder Supply Chain Network. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2010, 15, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrella, A.; Navichoc, D.; Kilian, B.; Dietz, T. Impact Pathways of Voluntary Sustainability Standards on Smallholder Coffee Producers in Honduras: Price Premiums, Farm Productivity, Production Costs, Access to Credit. World Dev. Perspect. 2022, 27, 100435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza Pião, R.; da Fonseca, L.S.; de Carvalho Januário, É.; Saes, M.S.M. Chapter 6—Certification: Facts, Challenges, and the Future. In Coffee Consumption and Industry Strategies in Brazil; de Almeida, L.F., Spers, E.E., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Consumer Sci & Strat Market; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 109–123. ISBN 978-0-12-814721-4. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade Arango, Y.; Castro Escobar, E.; Ramírez Ospina, D.E.; Andrade Arango, Y.; Castro Escobar, E.; Ramírez Ospina, D.E. Certificaciones e iniciativas de sostenibilidad en el sector cafetero: Un análisis desde la auditoría ambiental en el departamento de Caldas, Colombia. Contad. Adm. 2021, 66, 275. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, K.; Njeru, E.M.; Garnett, K.; Girkin, N. Assessing the Impact of Voluntary Certification Schemes on Future Sustainable Coffee Production. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascucci, F. Sustainability in the Coffee Sector: A Literature Review. In Sustainability in the Coffee Supply Chain; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 77–104. ISBN 978-3-031-72502-9. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, D.R.; Bekessy, S.A.; Lentini, P.E.; Garrard, G.E.; Gordon, A.; Rodewald, A.D.; Bennett, R.E.; Selinske, M.J. Sustainable Coffee: A Review of the Diverse Initiatives and Governance Dimensions of Global Coffee Supply Chains. Ambio 2024, 53, 984–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duran-Izquierdo, M.; Olivero-Verbel, J. Vulnerability Assessment of Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia: World’s Most Irreplaceable Nature Reserve. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 28, e01592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granados-Peña, R.; Arias Alzate, A.F.; Zárrate-Charry, D.; González Maya, J.F. Una estrategia de conservación a escala regional para el jaguar (Panthera onca) en el distrito biogeográfico de la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia. Rev. Biodivers. Neotrop. 2014, 4, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocarejo, D.; Del Cairo, C.; Ojeda, D.; Rojas Arias, F.; Esquinas, M.; Gonzalez, C.; Murcia, F.; Rojas, J.; Martínez, M.; García, M.E.; et al. Caracterización Socioeconómica y Cultural del Complejo de Páramos Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta en Jurisdicción de Corpamag y Corpocesar con Énfasis en Caracterización de Actores, Análisis de Redes y de Servicios Ecosistémicos; Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt: Bogotá, Colombia, 2015; p. 99. [Google Scholar]

- Durán-Izquierdo, M.L. Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta: Entre las Presiones Antrópicas y el uso Sostenible de sus Recursos. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Cartagena, Bolívar, Colombia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Corwin Rondano, A.C.; Issa Fontalvo, S.M.; Murillo Sanabria, O.; Morales, A. El ecoturismo como esperanza socioeconómica en territorios rurales de la región cafetera en el departamento del Magdalena. Loginn 2019, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FNC Federación Nacional de Cafeteros. Available online: https://magdalena.federaciondecafeteros.org/cafe-del-magdalena/ (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- Hoz, J.V.D.L. Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta: Economía de Sus Recursos Naturales; Banco de la Républica: Cartagena, Colombia, 2005; ISSN 1692–3715. [Google Scholar]

- Aragón-Guzmán, S.E.; Regino-Maldonado, J.; Vásquez-López, A.; Toledo-López, A.; Nuria Jurado-Celis, S.; Granados-Echegoyen, C.A.; Landero-Valenzuela, N.; Arroyo-Balán, F.; Quiroz-González, B.; Peñaloza-Ramírez, J.M. A Systematic Literature Review on Environmental, Agronomic, and Socioeconomic Factors for the Integration of Small-Scale Coffee Producers into Specialized Markets in Oaxaca, Mexico. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1386956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.; Njeru, E.M.; Garnett, K.; Girkin, N.T. Organic Management in Coffee: A Systematic Review of the Environmental, Economic and Social Benefits and Trade-Offs for Farmers. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 49, 1368–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.; Hussain, S.A.; Suleria, H.A.R. “Coffee Bean-Related” Agroecological Factors Affecting the Coffee. In Co-Evolution of Secondary Metabolites; Mérillon, J.-M., Ramawat, K.G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 641–705. ISBN 978-3-319-96397-6. [Google Scholar]

- Leal-Echeverri, J.C.; Tobón, C. The Water Footprint of Coffee Production in Colombia. Rev. Fac. Nac. Agron. Medellín 2021, 74, 9685–9697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadaf, S.A.; Shivaprasad, P.; Babou, C.; Hariyappa, N.; Chandrashekar, N.; Kumari, P.; Sowmya, P.R.; Hareesh, S.B.; Pati, N.R.; Nagaraja, J.S.; et al. Coffee (Coffea Spp.). In Soil Health Management for Plantation Crops: Recent Advances and New Paradigms; Thomas, G.V., Krishnakumar, V., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 337–389. ISBN 978-981-9700-92-9. [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel, F.M. Ecologia y Ensenanza Rural: Nociones Ambientales Basicas para Profesores Rurales y Extensionistas; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1996; ISBN 978-92-5-303847-3. [Google Scholar]

- FNC Proceso Productivo del Café. Available online: https://federaciondecafeteros.org/static/files/8Capitulo6.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Cassamo, C.T.; Draper, D.; Romeiras, M.M.; Marques, I.; Chiulele, R.; Rodrigues, M.; Stalmans, M.; Partelli, F.L.; Ribeiro-Barros, A.; Ramalho, J.C. Impact of Climate Changes in the Suitable Areas for Coffea arabica L. Production in Mozambique: Agroforestry as an Alternative Management System to Strengthen Crop Sustainability. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 346, 108341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaMatta, F.M.; Ramalho, J.D.C. Impacts of Drought and Temperature Stress on Coffee Physiology and Production: A Review. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2006, 18, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio del Medio Ambiente. Guia Ambiental para el Subsector Cafetero; Minambiente, Sociedad de Agricultores de Colombia, Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia, Eds.; Minambiente: Bogota, Colombia, 2002.

- Mamuye, M.; Gallemore, C.; Jespersen, K.; Kasongi, N.; Berecha, G. Changing Rainfall and Temperature Trends and Variability at Different Spatiotemporal Scales Threaten Coffee Production in Certain Elevations. Environ. Chall. 2024, 15, 100950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, R.; Jadmiko, S.D.; Hidayat, P.; Wachjar, A.; Ardiansyah, M.; Sulistyowati, D.; Situmorang, A.P. Managing Climate Risk in a Major Coffee-Growing Region of Indonesia. In Global Climate Change and Environmental Policy; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 147–205. ISBN 9789811395703. [Google Scholar]

- Campuzano-Duque, L.F.; Herrera, J.C.; Ged, C.; Blair, M.W. Bases for the Establishment of Robusta Coffee (Coffea canephora) as a New Crop for Colombia. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FNC Estadísticas Cafeteras. Available online: https://federaciondecafeteros.org/wp/estadisticas-cafeteras/ (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- FNC Cafés Suaves. Available online: https://federaciondecafeteros.org/wp/glosario/cafes-suaves/ (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Cenicafe Cartilla cafetera Cap. 01. Variedades de Café Sembradas en Colombia. Available online: https://www.fundacioncaucarural.org.co/3d-flip-book/cartilla-1-variedades-de-cafe-sembradas-en-colombia/ (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- De La Hoz Montes, M.; Perafán Ledezma, A.L.; Martínez-Dueñas, W.A. Apropiaciones sociales de la ciencia y la tecnología en la caficultura en la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta (Palmor y Río Piedras, Magdalena, Colombia). Jangwa Pana Rev. Cienc. Soc. Humanas 2019, 18, 183–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, P.S.; Duque, O.H. Guía para la Caficultura Sostenible en Colombia: Un Trabajo Articulado con los Caficultores Extensionistas y la Comunidad; CENICAFE: Chinchiná, Colombia, 2007; ISBN 978-958-97726-9-0. [Google Scholar]

- Leiva, B.; Vargas, A.; Casanoves, F.; Haggar, J. Changes in the Economics of Coffee Production between 2008 and 2019: A Tale of Two Central American Countries. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1376051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Cárdenas, E.L.; Oliveros Tascón, C.E.; Alfonso Carvajal, O.A.; Álvarez Mejía, F. Development of a New Striker for a Portable Coffee Harvesting Tool. Rev. Fac. Nac. Agron. Medellín 2013, 66, 7071–7083. [Google Scholar]

- Santinato, F.; Silva, R.P.D.; Silva, V.D.A.; Silva, C.D.D.; Tavares, T.D.O. Mechanical Harvesting of Coffee in High Slope. Rev. Caatinga 2016, 29, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, G.F.; Rosa, S.D.V.F.; Coelho, S.V.B.; Pereira, C.C.; Malta, M.R.; Fantazzini, T.B.; Vilela, A.L. Influence Of Hulling And Storage Conditions On Maintaining Coffee Quality. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2023, 95, e20190612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuela Martínez, A.E.; JR, S.-U.; RD, M.-R. Influence of Drying Air Temperature on Coffee Quality during Storage. Rev. Fac. Nac. Agron. Medellín 2023, 76, 10493–10503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Macías, E.T.; López, C.F.; Gentile, P.; Girón-Hernández, J.; López, A.F. Impact of Post-Harvest Treatments on Physicochemical and Sensory Characteristics of Coffee Beans in Huila, Colombia. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 187, 111852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presidencia; DANE; Minagricultura. Aumento de Cultivos de Café y Producción Ganadera Jalonaron Crecimiento del Sector Agro en 2024 y de la Economía Nacional. Available online: https://www.presidencia.gov.co/prensa/Paginas/Aumento-de-cultivos-de-cafe-y--produccion-ganadera-jalonaron-crecimiento-250218.aspx (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Agronet Cerca de 549.000 Familias Cafeteras Producen Más de 10,6 Millones de Sacos de Café Cada Año En Colombia. Available online: https://www.agronet.gov.co/Noticias/Paginas/Cerca-de-549-000-familias-cafeteras-producen-m%C3%A1s-de-10,6-millones-de-sacos-de-caf%C3%A9-cada-a%C3%B1o-en-Colombia.aspx (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Arcila Pulgarín, J.; Farfán Valencia, F.F.; Moreno Berrocal, A.M.; Salazar Gutiérrez, L.F.; Hincapie Gómez, E. Sistemas de Producción de Café en Colombia; Federación Nacional de Cafeteros: Bogotá, Colombia, 2007; ISBN 978-958-98193-0-2. [Google Scholar]

- Manson, S.; Nekaris, K.a.I.; Rendell, A.; Budiadi, B.; Imron, M.A.; Campera, M. Agrochemicals and Shade Complexity Affect Soil Quality in Coffee Home Gardens. Earth 2022, 3, 853–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noponen, M.R.A.; Edwards-Jones, G.; Haggar, J.P.; Soto, G.; Attarzadeh, N.; Healey, J.R. Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Coffee Grown with Differing Input Levels under Conventional and Organic Management. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2012, 151, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldi-Díaz, M.R.; De Medina-Salas, L.; Castillo-González, E.; León-Lira, R. Environmental Impact Associated with the Supply Chain and Production of Grounding and Roasting Coffee through Life Cycle Analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, G.A.A.; Palacios, L.M.; Guarín, H.P.; Castillo, H.S.V. Biodegradable Packaging Colombian Coffee Industry. In Biodegradable Polymers; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-1-00-323053-3. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, M.; Ghaly, A.E. Maximizing Sustainability of the Costa Rican Coffee Industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1716–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, P.C.C.; Dias Junior, M.d.S.; Andrade, M.L.d.C.; Guimarães, P.T.G. Compaction Caused by Mechanized Operations in a Red-Yellow Latosol Cultivated with Coffee over Time. Ciênc. Agrotecnol 2012, 36, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velmourougane, K. Impact of Organic and Conventional Systems of Coffee Farming on Soil Properties and Culturable Microbial Diversity. Scientifica 2016, 2016, 3604026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijanu, E.M.; Kamaruddin, M.A.; Norashiddin, F.A. Coffee Processing Wastewater Treatment: A Critical Review on Current Treatment Technologies with a Proposed Alternative. Appl. Water Sci. 2020, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemayehu, Y.A.; Asfaw, S.L.; Tirfie, T.A. Management Options for Coffee Processing Wastewater. A Review. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2020, 22, 454–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosalvitr, P.; Cuéllar-Franca, R.M.; Smith, R.; Azapagic, A. Environmental and Economic Sustainability Assessment of the Production and Consumption of Different Types of Coffee in the UK. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 49, 144–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suescún-Barón, C.A.; Giraldo Giraldo, C.A.; Sandoval Castaño, J.P.; Cantor Ávila, V.A.; Suescún-Barón, C.A.; Giraldo Giraldo, C.A.; Sandoval Castaño, J.P.; Cantor Ávila, V.A. La frontera agraria en disputa: Análisis de algunos conflictos territoriales sobre comunidades étnicas y campesinas en Colombia. Cuad. Econ. 2023, 42, 297–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantino, L.M. La taxonomía integrativa en la resolución de problemas taxonómicos complejos en algunos insectos plaga emergentes de la caficultura colombiana. Mem. Semin. Científico Cenicafé 2022, 73, e73106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla Soler, R. La Expansión de la Frontera Agrícola y Los Inicios de la Industrialización Colombiana; CSIC—Escuela de Estudios Hispano-Americanos (EEHA): Sevilla, Spain, 1997; ISBN 978-84-00-07680-1. [Google Scholar]

- Santos Delgado, A.; Sánchez Mejía, H.R.; Blanquiceth, M. Public and Private Land for Raising Cattle and Crops of Coffee in a Border Area of the Colombian Caribbean: Valledupar (Magdalena), 1920–1940. Mem. Rev. Digit. Hist. Arqueol. Desde Caribe 2015, 11, 244–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadovska, V.; Fernqvist, F.; Barth, H. We Do It Our Way—Small Scale Farms in Business Model Transformation for Sustainability. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 102, 103090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankoski, J.; Lankoski, L. Environmental Sustainability in Agriculture: Identification of Bottlenecks. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 204, 107656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, J. Ecoeficiencia: Marco de Análisis, Indicadores y Experiencias; CEPAL: Santiago, Chile, 2005; ISBN 978-92-1-322721-3. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar Ramirez, R. Gestión Verde del Negocio para la Sostenibilidad Empresarial: Ejemplos de empresas en Costa Rica. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Latinoamericana de Ciencia y Tecnología, San José, Costa Rica, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Alfaro, A.C. Economía, salud, desarrollo humano e innovación en el desarrollo sustentable. Conoc. Glob. 2018, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez León, I.M.; Arcas Lario, N.; García Hernández, M. La influencia del género sobre la responsabilidad social empresarial en las entidades de economía social. REVESCO Rev. Estud. Coop. 2011, 105, 143–172. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla, R.; Oddone, N. Manual para el Fortalecimiento de Cadenas de Valor | Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe; FIDA—CEPAL: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, A.L.; Hidalgo, J.F.O.; Manríquez, M.R. La responsabilidad social empresarial desde la percepción del capital humano. Estudio de un caso: The corporate social responsibility from the perception of human capital. A case study. Rev. Contab. 2017, 20, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajardo Fonseca, H. La producción mas limpia como estrategia ambiental en el marco del desarrollo sostenible. Rev. Ing. Matemáticas Cienc. Inf. 2017, 4, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retamoso, C.E.F. Producción Limpia, Contaminación y Gestión Ambiental; Pontificia Universidad Javeriana: Bogotá, Colombia, 2007; ISBN 978-958-683-924-2. [Google Scholar]

- Podhorsky, A. A Positive Analysis of Fairtrade Certification. J. Dev. Econ. 2015, 116, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcafé Falcafé Certification: Neighbors and Friends Program. Available online: http://www.falcafes.com.br/english.php? (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Beuchelt, T.D.; Zeller, M. Profits and Poverty: Certification’s Troubled Link for Nicaragua’s Organic and Fairtrade Coffee Producers. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1316–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scialabba, N.E.-H.; Hattam, C.; FAO. Agricultura Organica, Ambiente y Seguridad Alimentaria; Food & Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2003; ISBN 978-92-5-304819-9. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, D.J. What Is the Real Productivity of Organic Farming Systems? Outlook Agric. 2021, 50, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollni, M.; Bohn, S.; Ocampo-Ariza, C.; Paz, B.; Santalucia, S.; Squarcina, M.; Umarishavu, F.; Wätzold, M.Y.L. Sustainability Standards in Agri-Food Value Chains: Impacts and Trade-Offs for Smallholder Farmers. Agric. Econ. 2025, 56, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, C.; Haggar, J.; Cerretelli, S.; Van Oijen, M.; Cerda B, R.H. Comparing Carbon Agronomic Footprint and Sequestration in Central American Coffee Agroforestry Systems and Assessing Trade-Offs with Economic Returns. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 961, 178360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soleto Polanco, I.T.; Cruz-Morales, J.; Soleto Polanco, I.T.; Cruz-Morales, J. ¿Quién se beneficia de las certificaciones de café orgánico? El caso de los campesinos de La Sepultura, Chiapas. Rev. Pueblos Front. Digit. 2017, 12, 126–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, J.G.; Neilson, J. Reviewing the Impacts of Coffee Certification Programmes on Smallholder Livelihoods. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2017, 13, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meemken, E.-M. Do Smallholder Farmers Benefit from Sustainability Standards? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 26, 100373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire-Rajpaul, V.A.; Rajpaul, V.M.; McDermott, C.L.; Guedes Pinto, L.F. Coffee Certification in Brazil: Compliance with Social Standards and Its Implications for Social Equity. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 2015–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, L.T.K.; Hu, A.H.; Lan, Y.C.; Chen, Z.H. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment for Conventional and Organic Coffee Cultivation in Vietnam. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 17, 1307–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, P.R.; Chichaibelu, B.B.; Stellmacher, T.; Grote, U. The Impact of Coffee Certification on Small-Scale Producers’ Livelihoods: A Case Study from the Jimma Zone, Ethiopia. Agric. Econ. 2012, 43, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano Paredes, D.L.; Okada Saavedra, H.; Moscoso Cuaresma, J.R.; Azabache Moran, C.A.; Yesquén Delgado, K.N.d.P.; Diaz Cruz, M.E.; Salazar Seminario, V.L.; Pastor Pinto, J.; Amer Layseca, T. Fairtrade in Peru: Challenges and Opportunities for Sustainable and Equitable Agricultural Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Cruz, V.Y.V.; Tantriani; Cheng, W.; Tawaraya, K. Yield Gap between Organic and Conventional Farming Systems across Climate Types and Sub-Types: A Meta-Analysis. Agric. Syst. 2023, 211, 103732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ponti, T.; Rijk, B.; van Ittersum, M.K. The Crop Yield Gap between Organic and Conventional Agriculture. Agric. Syst. 2012, 108, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Cardona, S. Caficultura Orgánica e Identidades en el Suroccidente de Colombia. El Caso de la Asociación de Caficultores Orgánicos de Colombia, ACOC—Café sano. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- RED ECOLSIERRA INFORME GESTIÓN 2023. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1hHm0lTAKWbbZIp1g9mEagCcLV9uZ6sHl/view (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Valkila, J. Fair Trade Organic Coffee Production in Nicaragua—Sustainable Development or a Poverty Trap? Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 3018–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilian, B.; Jones, C.; Pratt, L.; Villalobos, A. Is Sustainable Agriculture a Viable Strategy to Improve Farm Income in Central America? A Case Study on Coffee. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoluk-Sikorska, J. Differences Between Prices of Organic and Conventional Food in Poland. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoluk-Sikorska, J.; Śmiglak-Krajewska, M.; Rojík, S.; Fulnečková, P.R. Prices of Organic Food—The Gap between Willingness to Pay and Price Premiums in the Organic Food Market in Poland. Agriculture 2024, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naegele, H. Where Does the Fair Trade Money Go? How Much Consumers Pay Extra for Fair Trade Coffee and How This Value Is Split along the Value Chain. World Dev. 2020, 133, 105006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, K.L.; Johnson, T.G.; Yamamoto, N.; Gautam, S.; Mishra, B. Comparing Technical Efficiency of Organic and Conventional Coffee Farms in Rural Hill Region of Nepal Using Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) Approach. Org. Agric. 2015, 5, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmah, D.M.; Mardawati, E.; Kastaman, R.; Pujianto, T.; Pramulya, R. Coffee Pulp Biomass Utilization on Coffee Production and Its Impact on Energy Saving, CO2 Emission Reduction, and Economic Value Added to Promote Green Lean Practice in Agriculture Production. Agronomy 2023, 13, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmah, D.M.; Putra, A.S.; Ishizaki, R.; Noguchi, R.; Ahamed, T. A Life Cycle Assessment of Organic and Chemical Fertilizers for Coffee Production to Evaluate Sustainability toward the Energy–Environment–Economic Nexus in Indonesia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, P.R.; Grote, U. Do Certification Schemes Enhance Coffee Yields and Household Income? Lessons Learned Across Continents. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 5, 716904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Castillo, N.E.; Melchor-Martínez, E.M.; Ochoa Sierra, J.S.; Ramirez-Mendoza, R.A.; Parra-Saldívar, R.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Impact of Climate Change and Early Development of Coffee Rust—An Overview of Control Strategies to Preserve Organic Cultivars in Mexico. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 738, 140225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Resende, M.L.V.; Pozza, E.A.; Reichel, T.; Botelho, D.M.S. Strategies for Coffee Leaf Rust Management in Organic Crop Systems. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitler, J.-C.; Etienne, H.; Léran, S.; Marie, L.; Bertrand, B. Description of an Arabica Coffee Ideotype for Agroforestry Cropping Systems: A Guideline for Breeding More Resilient New Varieties. Plants 2022, 11, 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggar, J.; Casanoves, F.; Cerda, R.; Cerretelli, S.; Gonzalez-Mollinedo, S.; Lanza, G.; Lopez, E.; Leiva, B.; Ospina, A. Shade and Agronomic Intensification in Coffee Agroforestry Systems: Trade-Off or Synergy? Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 645958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FiBL. FiBL Statistics—Key Indicators. Available online: https://statistics.fibl.org/world/key-indicators.html (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Bravo-Monroy, L.; Potts, S.G.; Tzanopoulos, J. Drivers Influencing Farmer Decisions for Adopting Organic or Conventional Coffee Management Practices. Food Policy 2016, 58, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Q.V.; Jovanovic, G.; Le, D.-T.; Cowal, S. Understanding the Perceptions of Sustainable Coffee Production: A Case Study of the K’Ho Ethnic Minority in a Small Village in Lâm Đồng Province of Vietnam. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebig, T.; Jassogne, L.; Rahn, E.; Läderach, P.; Poehling, H.-M.; Kucel, P.; Van Asten, P.; Avelino, J. Towards a Collaborative Research: A Case Study on Linking Science to Farmers’ Perceptions and Knowledge on Arabica Coffee Pests and Diseases and Its Management. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitiku, F.; De Mey, Y.; Nyssen, J.; Maertens, M. Do Private Sustainability Standards Contribute to Income Growth and Poverty Alleviation? A Comparison of Different Coffee Certification Schemes in Ethiopia. Sustainability 2017, 9, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, E.; Marton, S.M.R.R.; Baumgart, L.; Curran, M.; Stolze, M.; Schader, C. Evaluating the Sustainability Performance of Typical Conventional and Certified Coffee Production Systems in Brazil and Ethiopia Based on Expert Judgements. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanzala, R.W.; Marwa, N.; Lwanga, E.N. Impact of Agricultural Credit on Coffee Productivity in Kenya. World Dev. Sustain. 2024, 5, 100166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folch, A.; Planas, J. Cooperation, Fair Trade, and the Development of Organic Coffee Growing in Chiapas (1980–2015). Sustainability 2019, 11, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngango, J.; Kim, S.G. Assessment of Technical Efficiency and Its Potential Determinants among Small-Scale Coffee Farmers in Rwanda. Agriculture 2019, 9, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, A.; Rivera, J. Producer-Level Benefits of Sustainability Certification. Conserv. Biol. J. Soc. Conserv. Biol. 2011, 25, 1176–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keenan, M.; Fort, R.; Vargas, R. Shocked into Side-Selling? Production Shocks and Organic Coffee Farmers’ Marketing Decisions. Food Policy 2024, 125, 102631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamsyah, A.; Widiyanesti, S.; Wulansari, P.; Nurhazizah, E.; Dewi, A.S.; Rahadian, D.; Ramadhani, D.P.; Hakim, M.N.; Tyasamesi, P. Blockchain Traceability Model in the Coffee Industry. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2023, 9, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.; Wojewska, A.N.; Persson, U.M.; Bager, S.L. Coffee Producers’ Perspectives of Blockchain Technology in the Context of Sustainable Global Value Chains. Front. Blockchain 2022, 5, 955463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, J.; Lara, D.; Opitz, S.; de Castelberg, S.; Urioste, S.; Irazoque, A.; Castro, D.; Wildisen, E.; Gutierrez, N.; Yeretzian, C. Making Specialty Coffee and Coffee-Cherry Value Chains Work for Family Farmers’ Livelihoods: A Participatory Action Research Approach. World Dev. Perspect. 2024, 33, 100551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, D.G.; Pereira, H.M.F.; Saes, M.S.M.; Oliveira, G.M. de When Unfair Trade Is Also at Home: The Economic Sustainability of Coffee Farms. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoggia, A.; Fantini, A. Revealing the Governance Dynamics of the Coffee Chain in Colombia: A State-of-the-Art Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappo, E.; Wilson, C.; Flory, S.L. Hybrid Coffee Cultivars May Enhance Agroecosystem Resilience to Climate Change. AoB Plants 2021, 13, plab010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.A.; Abrahão, J.C.d.R.; Reis, A.M.; Santos, M.d.O.; Pereira, A.A.; Botelho, C.E.; Carvalho, G.R.; Castro, E.M.d.; Barbosa, J.P.R.A.D.; Botega, G.P.; et al. Strategy for Selection of Drought-Tolerant Arabica Coffee Genotypes in Brazil. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, R.; Mello, C.; Nagai, C.; Sipes, B.; Matsumoto, T. Evaluation of Coffea arabica Cultivars for Resistance to Meloidogyne Konaensis. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga-Cardona, J.; Várzea, V.M.P.; Montoya-Restrepo, E.C.; Gaitán-Bustamante, Á.L.; Flórez-Ramos, C.P. Potential of the Colombian Coffee Collection as a Source of Genetic Resistance to Colletotrichum Kahawae JM Waller and PD Bridge. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrdoda, Y.; Balzano, M.; Vianelli, D. The Formation of a Sustainable Organizational Identity: Insights from Brazilian Coffee Producers. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-Y.; Yen, C.-Y.; Tsai, K.-N.; Lo, W.-S. A Conceptual Framework for Agri-Food Tourism as an Eco-Innovation Strategy in Small Farms. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blanco-Pacheco, T.E.; De-La-Rosa-Cadavid, M.L.; Quintero-Castañeda, C.Y. Corporate Sustainability in the Coffee Industry: Organic Certification for Small Producers in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10975. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410975

Blanco-Pacheco TE, De-La-Rosa-Cadavid ML, Quintero-Castañeda CY. Corporate Sustainability in the Coffee Industry: Organic Certification for Small Producers in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):10975. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410975

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlanco-Pacheco, Tatiana Esther, María Luz De-La-Rosa-Cadavid, and Cristian Yoel Quintero-Castañeda. 2025. "Corporate Sustainability in the Coffee Industry: Organic Certification for Small Producers in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 10975. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410975

APA StyleBlanco-Pacheco, T. E., De-La-Rosa-Cadavid, M. L., & Quintero-Castañeda, C. Y. (2025). Corporate Sustainability in the Coffee Industry: Organic Certification for Small Producers in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia. Sustainability, 17(24), 10975. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410975