Abstract

The Qinba Mountains in China span six provinces, characterized by a large population, rugged terrain, steep peaks, deep valleys, and scarce flat land, making large-scale agricultural development challenging. Terraced fields serve as the core cropland type in this region, playing a vital role in preventing soil erosion on sloping farmland and expanding agricultural production space. They also function as a crucial medium for sustaining the ecosystem services of mountainous areas. As a transitional zone between China’s northern and southern climates and a vital ecological barrier, the Qinba Mountains’ terraced ecosystems have undergone significant spatial changes over the past two decades due to compound factors including the Grain-for-Green Program, urban expansion, and population outflow. However, current large-scale, long-term, high-resolution monitoring studies of terraced fields in this region still face technical bottlenecks. On one hand, traditional remote sensing interpretation methods rely on manually designed features, making them ill-suited for the complex scenarios of fragmented, multi-scale distribution, and terrain shadow interference in Qinba terraced fields. On the other hand, the lack of high-resolution historical imagery means that low-resolution data suffers from insufficient accuracy and spatial detail for capturing dynamic changes in terraced fields. This study aims to fill the technical gap in detailed dynamic monitoring of terraced fields in the Qinba Mountains. By creating image tiles from Landsat-8 satellite imagery collected between 2017 and 2020, it employs three deep learning semantic segmentation models—DeepLabV3 based on ResNet-34, U-Net, and PSPNet deep learning semantic segmentation models. Through optimization strategies such as data augmentation and transfer learning, the study achieves 15-m-resolution remote sensing interpretation of terraced field information in the Qinba Mountains from 2000 to 2020. Comparative results revealed DeepLabV3 demonstrated significant advantages in identifying terraced field types: Mean Pixel Accuracy (MPA) reached 79.42%, Intersection over Union (IoU) was 77.26%, F1 score attained 80.98, and Kappa coefficient reached 0.7148—all outperforming U-Net and PSPNet models. The model’s accuracy is not uniform but is instead highly contingent on the topographic context. The model excels in environments that are archetypal for mid-altitudes with moderately steep slopes. Based on it we create a set of tiles integrating multi-source data from RBG and DEM. The fusion model, which incorporates DEM-derived topographic data, demonstrates improvement across these aspects. Dynamic monitoring based on the optimal model indicates that terraced fields in the Qinba Mountains expanded between 2000 and 2020: the total area was 57.834 km2 in 2000, and by 2020, this had increased to 63,742 km2, representing an approximate growth rate of 8.36%. Sichuan, Gansu, and Shaanxi provinces contributed the majority of this expansion, accounting for 71% of the newly added terraced fields. Over the 20-year period, the center of gravity of terraced fields shifted upward. The area of terraced fields above 500 m in elevation increased, while that below 500 m decreased. Terraced fields surrounding urban areas declined, and mountainous slopes at higher elevations became the primary source of newly constructed terraces. This study not only establishes a technical paradigm for the refined monitoring of terraced field resources in mountainous regions but also provides critical data support and theoretical foundations for implementing sustainable land development in the Qinba Mountains. It holds significant practical value for advancing regional sustainable development.

1. Introduction

The Qinba Mountainous Region is characterized by its steep terrain, deep valleys, and scarce flat land, with limited and scattered arable land. It is a typical mountainous agricultural area in China, and terraced fields are one of the most representative agricultural measures in this region. As the core form of slope farmland management, terraced fields reduce the risk of geological disasters such as landslides and debris flows, expand the area of cultivated land, increase crop yields, protect forest vegetation, and enhance the water conservation capacity of mountains. They play a crucial role in the economic development, agricultural security, and ecological security of the Qinba Mountainous Region [1]. However, over the past 20 years, the spatial pattern of terraced fields in the Qinba Mountainous Region has undergone significant changes due to the combined effects of returning farmland to forests, urban expansion, and the outflow of the mountain population. Accurately grasping the spatial distribution and changes of terraced fields is conducive to the effective protection and scientific development of the characteristic agricultural areas in the Qinba Mountainous Region.

Due to the immaturity of early remote sensing imaging technology and the low resolution of remote sensing images, the extraction technology of terraced fields from remote sensing images was not mature and remained at the stage of manual statistics for a long time. With the popularization and application of high-resolution remote sensing images, the extraction of terraced fields has begun to attract attention from the academic community and has gradually become a research hotspot [2]. There have been certain studies on extracting terraced field information using remote sensing images. Currently, there are mainly four types of methods for extracting terraced fields, including visual interpretation, texture spectrum information-based methods, object-oriented classification, and machine learning [3]. Visual interpretation is the main method for extracting terraced field information, which is based on the spectral, texture, and shape information of the images. Yang Lei extracted terraced fields and other soil and water conservation information through visual interpretation of Spot5 images. The results showed that the effect of extracting terraced fields through visual interpretation was poor [4]. With the continuous development of satellite sensors, the unique spatial frequency, texture features, and spectral differences of terraced fields can be utilized to achieve automatic interpretation through threshold segmentation, texture filtering, and other means. Wang Qing used high-resolution remote sensing images to extract terraced fields through the Fourier transform and compared this method with traditional supervised and unsupervised classification methods [5]. Zhao Xin et al. analyzed the feasibility of extracting terraced field information using the Fourier transform based on GF-1 images. The results showed that a large number of terraced fields with indistinct texture features were missed or misinterpreted, and the Fourier transform algorithm was difficult to widely apply for extracting terraced field information [6]. With the rapid development of high-resolution satellite sensors, object-oriented classification methods have also been applied to the extraction of terraced field information. This method segments remote sensing images into object units with semantic meaning and classifies them based on multi-dimensional features such as spectral, shape, and texture. Zhang Yugu, based on Spot5 images, used object-oriented classification, traditional supervised classification, and unsupervised classification methods to extract terraced field information. The results showed that the accuracy of extracting terraced fields using the object-oriented classification method was significantly higher than that of the traditional two classification methods [7]. With the development of computing power and algorithms, machine learning methods have been widely applied. These methods still rely on manually designed features and use statistical learning classifiers such as support vector machines, random forests, and decision trees to automatically construct the mapping relationship between input features and output categories [8,9]. Li Wanyuan et al. used random forest and other algorithms to classify terraced fields in the Guyuan area of Ningxia and compared them with SVM and decision trees. The results showed that the recognition accuracy of random forest was the highest [10]. In addition, some studies have combined terrain data and image features to extract terraced fields. By using the unique spatial frequency, shape, and other parameters of terraced fields to assist in segmentation, good results have been achieved. Among them, BP neural networks do not require manual setting of corresponding rules based on terraced field features, avoiding the interference of subjective factors. Support vector machines provide a classification standard for distinguishing terraced fields from non-terraced fields [11,12].

According to the current research status on terraced field extraction. The efficiency of extracting terraced field information based on visual interpretation methods is low, with high human and material costs, and the interpretation accuracy varies greatly, with low repeatability. The extraction of terraced fields based on texture spectral information is disturbed by the textures of non-terraced field objects and different terraced fields, resulting in a large number of false and missed areas, leading to unsatisfactory extraction accuracy. The extraction of terraced fields based on object-oriented methods requires manual adjustment of various parameter values, which is highly subjective. The extraction of terraced fields based on machine learning, such as BP neural networks, has limited information and cannot effectively eliminate interference objects on terraced fields, thus affecting the extraction accuracy.

In recent years, deep learning technology has become mainstream in image recognition. Compared with traditional machine learning, the advantage of deep learning is that it does not require manual feature extraction. The remote sensing image analysis method based on convolutional neural networks can significantly improve the recognition accuracy by automatically learning multi-level features from the original image and has been widely used in high-resolution remote sensing image classification tasks [13]. Common network structures include fully convolutional networks (FCN), U-Net, DeepLab series, etc., for pixel classification, and Faster R-CNN, Mask R-CNN, YOLO, SSD, etc., for object detection [14]. For terraced field interpretation research, Zhao et al. proposed the NLDF-Net model, which introduces a non-local attention module and a dual fusion module on the basis of U-Net, achieving better extraction results than other deep models [15]. Xie et al. proposed the JAM-R-CNN model based on Mask R-CNN, combining skip networks and convolutional attention mechanisms, effectively improving the accuracy of terraced field recognition [16]. Tian et al. optimized the structure of the classic segmentation network DeepLabv3 and weighted the loss to adapt to the fragmented characteristics of terraced fields, achieving higher accuracy and better recognition of field ridges and roads [17].

Although convolutional neural networks are widely used in remote sensing image interpretation, there are still problems such as poor multi-scale adaptability, severe loss of detailed information, and insufficient handling of inter-class differences in the application of terraced field interpretation, which affect the actual interpretation effect [18]. To address these issues, DeepLabV3 uses dilated spatial pyramid pooling to extract multi-scale features in parallel with different dilation rates, enhancing the adaptability to targets of diverse scales such as building clusters and farmlands, making it suitable for terraced field extraction [19]. Chen proposed to use the core dilated convolution of the DeepLab series to expand the receptive field of the convolution kernel, integrate more feature information, and extract the segmented image where the foreground and background can be clearly distinguished, making the edges of different attributes clearer [20]. Vijay et al. proposed the SegNet model in 2017, which has the advantage of reducing model running time and memory consumption [21]. Based on this, models such as Bayesian SegNet and U-Net series have been developed [22]. U-Net enhances feature extraction and reduces information loss during downsampling by strengthening detail recovery, improving the accuracy of road and river boundaries, making it suitable for fine tasks with small samples and high resolution, and more suitable for terraced field extraction [23]. Lu et al. used an improved U-Net deep learning model to extract the spatial distribution of terraced fields in the Loess Plateau of China [24]. Zhao H proposed the Pyramid Scene Analysis Network (PSPNet) model, which, compared with other models, integrates context information from different regions to identify and extract targets for all pixels in the image [25]. This deep learning model can capture global and local contexts through multi-scale pooling for modeling, and capture global scenes, regional structures and local details through multi-level pooling [26].

Among the deep learning models for land object recognition, DeepLabV3 represents the technical route of “dilated convolution + global context modeling”, UNet represents the technical route of “encoder-decoder + detail recovery”, and PSPNet represents the technical route of “multi-scale pooling + global scene capture”. These three routes basically cover the core technical directions of current semantic segmentation, and have all been verified in a large number of practices in remote sensing land object extraction, and have mature backbone networks. Therefore, this study adopts these three classic and widely used networks in the field of remote sensing land object extraction, which makes the research have a clear technical orientation and comparable basis [27].

Generally speaking, the higher the resolution of remote sensing images used for interpretation, the higher the accuracy. However, due to the low resolution of remote sensing images before 2010, it is difficult to use deep learning models trained with high-precision images for recognition. When making remote sensing slices through visual interpretation with low-precision images, there are problems of low accuracy and unclear edge recognition. Therefore, this study selects the highest resolution historical images available (15 m resolution), uses ArcGISPro 3.0.1 to make remote sensing interpretation slices, and then uses Retnet-34 as the backbone, and respectively uses DeepLabV3, U-Net, and PSPNet models for deep learning training. After comparing the results, the deep learning model with the highest accuracy is used to finely extract terraced fields in the Qinba Mountain Area, and analyze the spatio-temporal distribution change rules of terraced fields in the Qinba Mountain Area from 2000 to 2020.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

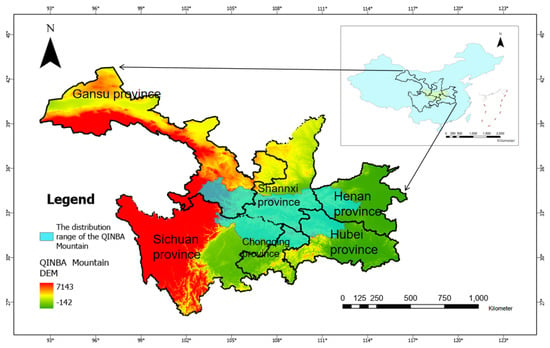

The study area encompasses the southern region of Shaanxi Province, the southeastern part of Gansu Province, the northern portion of Sichuan Province, the western section of Henan Province, the northern area of Hubei Province, and the northeastern region of Chongqing Municipality (Figure 1). The total land area covers approximately 280,000 square kilometers. The Qinba Mountain Region, the core geographical entity of the study area, is primarily composed of the Qinling Mountains in the north and the Daba Mountains in the south. This region forms an arc-shaped structural belt resulting from the east-west trending Qinling Mountains and the northwest-southeast oriented Daba Mountains. The Qinling Mountains, situated in the northern part of the study area, are characterized by mid-to-high mountainous terrain with elevations ranging from 1500 to 3000 m. The topography is marked by steep slopes and deeply incised valleys. In contrast, the southern part of the study area corresponds to the Daba Mountains, where the dominant landforms are low to mid-high mountains with elevations between 800 and 2000 m and relatively gentle slopes. Intermontane river valleys and basins, with elevations of 400 to 800 m, exhibit relatively flat terrain. The climate of the region lies within a transitional zone between the subtropical monsoon climate and the warm temperate monsoon climate, exhibiting notable spatial heterogeneity. The mean annual temperature ranges from 12 °C to 16 °C, with January averages between −2 °C and 3 °C and July averages from 22 °C to 28 °C. Annual precipitation varies from 700 to 1200 mm, with 70% to 80% occurring between May and September, often accompanied by heavy rainfall events. Land use is predominantly forested, accounting for over 50% of the total area. Terraced fields are primarily developed through the conversion of forested land or the modification of sloping cropland. The region functions as a traditional agricultural zone, with major crops including rice, maize, and tea. The rural population was estimated at approximately 18 million in 2020.

Figure 1.

The distribution range of the Qinba Mountain Area.

2.2. Research Method

2.2.1. Remote Sensing Image Data

This study analyzed the 15 m resolution remote sensing images of the Qinba Mountain Area through a deep learning model. In 2000 and 2010, remote sensing images were obtained via Landset-7 satellite (15 m resolution), and in 2020, remote sensing images were obtained via Landset-8 satellite (15 m resolution). Using the Gram-Schmidt Pan Sharpening tool for panchromatic fusion in ENVI 5.6.

2.2.2. DEM Data

A digital elevation model with a spatial resolution of 30 m was adopted, and the data number was NASA-SRTM1. Resample the DEM to 15 m using bilinear interpolation.

2.2.3. Sample Slice

Remote sensing slices of the Qinba Mountain Area were obtained via the Landsat-8 satellite, and the images were stitched together from the data of 2017 to 2020. To ensure consistency in spatial analysis and area calculations, all remote sensing imagery and DEM data have been reprojected into the WGS1984 (EPSG:4326). The image preprocessing was performed in ArcGIS Pro. The initial steps included radiometric correction and atmospheric correction to minimize sensor and atmospheric distortions. Then the 30-m multispectral bands were fused with the 15-m panchromatic band by the Gram-Schmidt Pan Sharpening tool for panchromatic fusion in ENVI. Following pan-sharpening, the 30-m spatial resolution data was resampled to 15 m.

After completing the tile production, proceed to create a set of tiles integrating multi-source data from RBG and DEM. It provides the deep learning model with explicit topographical context for each pixel, which is crucial for distinguishing terraced fields from other land cover types with similar spectral signatures but different terrain characteristics. Use DEM data as a layer and perform spatial data fusion with a corresponding multispectral remote sensing image using the Gram-Schmidt Pan Sharpening tool in ENVI. Overlay elevation information onto visible band data to create fused remote sensing data. Input this feature-overlay method into a deep learning model for training. Prior to fusion, perform registration between the two datasets to minimize the impact of projection errors.

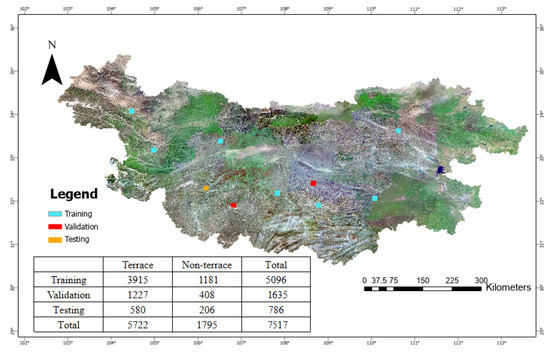

Ten different plots were selected to make terraced field interpretation slices, and the area of each plot was 10 km × 10 km. The image processing steps are geometric correction → radiometric correction → resampling → image fusion → data cropping. Subsequently, the visual interpretation method was used to create the sample data of terraced fields. In this study, only the elements of terraced fields need to be extracted, so the annotations are divided into two categories. Terraced fields are set as 1, and non-terraced fields are set as 0. The preprocessed images were segmented into object classification slices with slice sizes of 256 × 256, step lengths of 128 × 128, and overlap rates ranging from 10% to 20%. For ambiguous pixels on class boundaries, the label was assigned to the class covering >30% of the pixel’s area. Random horizontal flip, random vertical flip, random rotation, Contrast adjustment, and Gaussian Blur was used for Data Augmentation. A total of 7517 terraced field sample slices were obtained.

2.2.4. Deep Learning Parameter Configuration

To prevent spatial data leakage and ensure an unbiased evaluation of the model’s generalization capability, we implemented a strict geographically-based dataset splitting strategy. We first partitioned the ten 10 km × 10 km geographic plots into distinct training, validation, and test sets. Seven plots were allocated for model training (70% of slices), two for validation (20% of slices), and one entirely separate plot was reserved for model testing (10% of slices). Geographic plots are shown in Figure 2. And then adopted Spatial 3-Fold Cross-Validation. The training and validation blocks were merged into one set, which was then partitioned into 3 folds. A 3-fold cross-validation procedure was performed on the development set. In each of the three iterations, one fold (3 blocks) was used for validation, while the remaining two folds (6 blocks) were used for training. The performance metrics were averaged across all three folds to provide a robust estimate of each model’s generalization performance, reported as SD.

Figure 2.

Training, Validation and Testing of the Spatial Distribution Map of Geographical Blocks.

A random seed of 42 was set for all stochastic processes, including dataset splits, model weight initialization, and data augmentation. Before being fed into the models, input image slices underwent a normalization strategy and data augmentation. Pixel values were scaled to the range of [0, 1]. Subsequently, they were normalized on a per-channel basis using the mean and standard deviation derived from the BigEarthNet dataset, on which the backbone network was pre-trained. For the creation of ground truth masks, a consistent labeling rule for ambiguous edges was enforced: any pixel where the boundary between classes passed through was assigned the label of the class that covered the majority (>30%) of the pixel’s area. This minimized annotation ambiguity and ensured label consistency.

DeeplabV3, U-Net, and PSPNet all use the pre-trained backbone network Resnet for transfer learning. The Optimizer selects AdamW and the Initial learning rate is set to 0.001. Choose CosineAnnealingWarmRestarts vector Scheduler, the largest gradient norm is 1.0. Epoch is 50. Batch Size is 16 which was the maximum feasible size for the available 8 GB GPU memory. An adaptive learning rate optimizer with decoupled weight decay. The loss function was a combination of CrossEntropyLoss and DiceLoss to handle potential class imbalance. The early stop Patience is 5, meaning the training would terminate if the validation loss did not improve for five consecutive epochs, and the backbone network freezing strategy is set to phased thawing. The hardware is as follows: 8GB GPU video memory, CPU is an Intel i5 13400 10-core processor, and memory is 16GB.

2.3. Formula

C—Number of interpretation categories (terrace and non-terrace);

Ti—Total correct raster;

TP_i — Number of pixels where predicted values match actual values;

TN_i — Neither the measured value nor the true value matches the number of pixels in this category;

FP_i — The number of other categories misclassified as real category;

FN_i — The number of true values misclassified as other categories.

2.4. Post-Processing

The probabilistic graph generated by the deep learning model needs to be converted into a binary mask through a Threshold (Threshold), and the initial threshold is determined based on the optimal F1 score of the test set to achieve a balance between the accuracy and recall rate of terraced field recognition. For highly heterogeneous areas, local adaptive thresholds are adopted to calculate the average probability within a 3 × 3 sliding window. When the probability of the central pixel is greater than the window mean ×1.1, it is determined to be terraced fields, reducing systematic errors caused by terrain. Isolated fine pixels and internal cavities of terraced fields need to be cleared through morphological operations. First, use 3 × 3 structural elements to corrode the mask to remove fine areas with an area of less than 2 pixels (approximately 256 m2 at a resolution of 15 m). Then, use 3 × 3 structural elements to expand and fill the voids within the terraced fields that are less than 3 pixels in size, restoring the continuity of the fields. The mask was converted into a vector polygon using ArcGISPro, and the PAEK algorithm with a “smoothing factor = 5” was applied to the polygon boundaries to eliminate local fluctuations and perform smoothing processing.

Binary mask calculation formula:

P(x,y)—Pixel Probability;

T—Global threshold;

T local(x,y)—Local threshold;

When T = 0.55,T local(x,y) = Window Mean(3 × 3) × 1.1.

3. Results

3.1. Dataset Creation

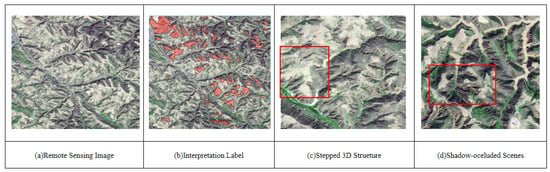

The characteristics of terraced fields in Landsat-8 remote sensing imagery are shown in Figure 3b. Based on the experimental requirements for terraced field extraction, visual interpretation was applied to assign corresponding categories and labels to the imagery. Since this study only requires the extraction of terraced field geographic features, they are classified as terraced fields (1) and non-terraced fields (0).

Figure 3.

Sample labeling and different types of terraced fields. (Red squares is terrace).

The Qinba Mountains exhibit diverse terraced field types with complex structures and varying morphological characteristics, complicating their extraction from remote sensing imagery. To extract terraced field information using deep learning, the training samples must contain rich terraced field features to ensure the deep learning model accurately learns these characteristics.

The first category exhibits distinct morphological characteristics, featuring pronounced three-dimensional terraced structures with clearly defined strip-like features (Figure 3c). The second category is embedded within valleys, showing significant shadow occlusion and indistinct boundaries (Figure 3d).

3.2. Comparison of Terrace Training Results

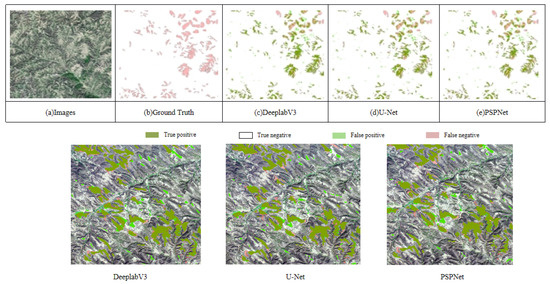

Using visual interpretation results as validation samples, three improved network models were trained for 50 epochs each. The trained models were then applied to validate the test set. Representative image blocks from the test set were selected for result demonstration, with predictions shown in Figure 4. Visually, all three deep learning models exhibit high accuracy in interpreting terraced fields in the Qinba Mountains, accurately representing most sub-regions with clear boundaries.

Figure 4.

Qualitative comparisons of semantic segmentation and error maps among different methods.

To further investigate the performance disparities revealed by the quantitative metrics, a qualitative visual assessment was performed. Figure 4 presents a comparative visualization of the segmentation results from the three deep learning models on a single,. The map illustrates prediction outcomes by overlaying True Positives, False Positives, and False Negatives on the original imagery, allowing for a direct analysis of each model’s behavior and typical error patterns.

PSPNet exhibited the least satisfactory performance. Its result is marked by a significant number of FN. This indicates that the model failed to identify a large portion of the actual terraces, particularly smaller patches, those with indistinct boundaries, or those situated in terrain shadow. U-Net performance was intermediate. In comparison to PSPNet, U-Net achieved a notable reduction in FN, producing more complete and contiguous terrace segments. DeepLabV3 demonstrated superior and more robust performance; its output shows the best equilibrium, achieving the lowest rates of both FN and FP.

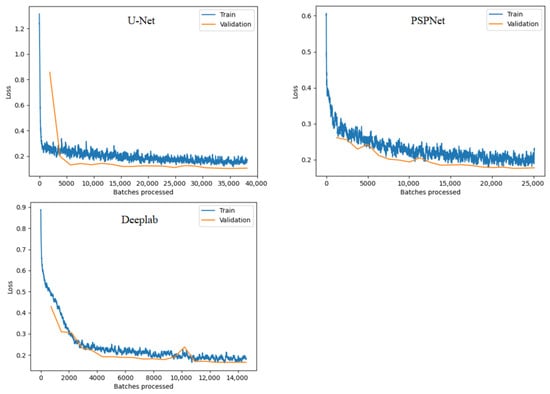

3.3. Accuracy Assessment of the Dataset

The training loss curves (blue represents training set loss, orange represents validation set loss) allow us to compare the training processes and performance differences among U-Net, PSPNet, and DeepLabV3 as follows (Figure 5). DeepLabV3 converges most rapidly among the three models, with training loss dropping below 0.2 after approximately 2000 batches and validation loss converging simultaneously. This demonstrates its superior fitting efficiency for the Qinba Mountain terraced field dataset. U-Net’s training loss stabilizes around 5000 batches, converging slower than DeepLabV3+ but faster than PSPNet. PSPNet exhibited the slowest convergence, with loss values only gradually stabilizing after 5000 batches. Notably, its training loss remained below validation loss, indicating significant overfitting. Consequently, its generalization capability was relatively weak, demonstrating insufficient adaptation to the complex features of the Qinba Mountain terraced field dataset.

Figure 5.

Training and Validation loss.

The accuracy matrix for the different models is shown in Table 1. Based on the comprehensive performance of core metrics, DeepLabV3 demonstrated the best performance among the three models, followed by U-Net, while PSP-Net showed relatively weaker performance. The accuracy matrix (Table 1) shows that the DeepLab model achieved the highest recall (73.70%), precision (83.50%), IoU (77.26%), and F1 (80.98%) for the terraced field category among the three models. It also achieved the highest MPA (79.42%) and Kappa coefficient (71.48%), indicating superior classification accuracy between terraced and non-terraced fields, overall consistency, and minimal false negatives for terraced fields. The PSPNet model suffers from local detail loss due to pooling operations and employs a relatively simple fusion method for multi-scale features. In the fragmented terrain of the Qinba Mountains, where small-scale terraces are prevalent, it exhibits significant underclassification of small plots and misclassification of non-terraced areas. This model struggles to accurately identify individual terraces, often misclassifying large areas of scattered terraces as a single entity. The U-Net model relies on an encoder-decoder + skip-connection architecture, preserving more local details. This provides advantages in restoring terrace boundaries and identifying small plots. However, its lack of multi-scale global feature fusion results in weaker semantic discrimination between terraces and non-terraces compared to DeepLabV3, leading to slightly lower precision and recall rates. DeepLabV3’s structural design best aligns with the extraction requirements for Qinba Mountain terraces, delivering optimal performance in accuracy, stability, and consistency. U-Net serves as a lightweight alternative. PSP-Net, constrained by its structural limitations, demonstrates weaker performance in interpreting Qinba Mountain terraces.

Table 1.

The accuracy matrix for the different models.

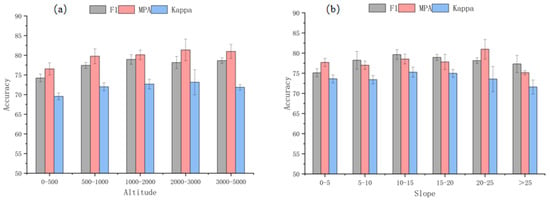

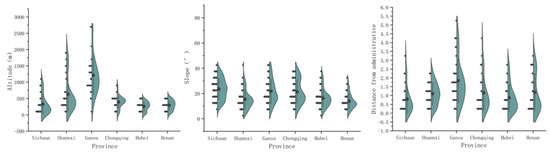

3.4. Terrain-Level Uncertainty

As crucial factors in terrace classification, terrain has a major impact on classification accuracy. Terraces with obvious terrain features, specific slope and elevation, are easier to identify. The terrain-related uncertainty of our data is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

F1, Kappa, MPA of terrace class for (a) different elevations and (b) different slopes.

The model exhibits its lowest accuracy in the low-altitude zone. River valleys and basins at lower elevations are often mosaics of various land cover types, including fragmented agricultural plots, expanding urban settlements, and infrastructure, which creates significant spectral confusion and complicates the identification of traditional terraced fields. Model performance steadily increases with altitude, peaking in the 1000–2000 m and 2000–3000 m ranges. In these areas, terraces are often the dominant form of agriculture, creating large, contiguous, and well-defined features that align perfectly with what the model has learned. A slight decrease in performance is observed at the highest elevations. This can be attributed to the transition to alpine and sub-alpine environments, where terraces become smaller, more fragmented, and are often interspersed with alpine meadows, shrubs, or bare rock, increasing classification ambiguity. The model achieves its highest accuracy in the 15–20° and particularly the 20–25° slope categories. This is the ideal range where terraces are most necessary and, consequently, most distinct. The topographic signature of a flat tread and a steep riser is maximized in this range, providing strong, unambiguous geometric and spectral features for the model to correctly classify.

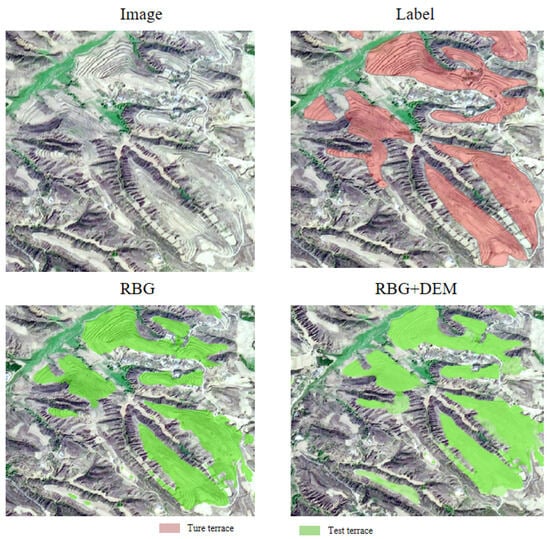

3.5. Application of Multi-Channel Input Fusion in Mountain Terraces Identification

The RGB model, relying solely on spectral information, successfully identifies the general presence of terraced fields but the recognition accuracy varies among different DEMs. The predictions within large, contiguous terrace areas are fraught with internal voids and fragmentation. This indicates that when variations in spectral signatures occur within a terrace the model erroneously classifies these patches as non-terrace, thereby failing to preserve the semantic integrity of the geographic feature. In addition, the model exhibits a tendency to misclassify landforms with similar linear or curvilinear textures, such as contour farming strips or erosional gullies, as terraced fields. By learning from 2D texture alone, the model struggles to differentiate the true step-like structure of terraces from visually similar patterns on sloped terrain.

The fusion model, which incorporates DEM-derived topographic data, demonstrates improvement across these aspects (Figure 7). The voids and fragmentation that plagued the baseline model’s predictions are effectively filled, resulting in complete and coherent terrace patches. And the fusion model accurately discriminates between terraced fields and the surrounding sloped terrain, significantly reducing the false positives observed in the baseline result.

Figure 7.

Ablation experiment of RBG and RGB+DEM.

Table 2 demonstrates that the fusion model (RGB+DEM) significantly outperforms the baseline model (RGB-Only) in the task of terrace extraction. The IoU increases from 77.26% to 78.38%, and the Kappa coefficient increases from 71.48% to 73.53%, which signifies a meaningful improvement in the model’s overall classification accuracy and reliability. The standard deviation of the IoU and Kappa score was reduced, indicating that the inclusion of DEM data makes the model not only more accurate but also more robust and generalizable across different geographic scenes within the Qinba Mountains.

Table 2.

The accuracy matrix for the different channels.

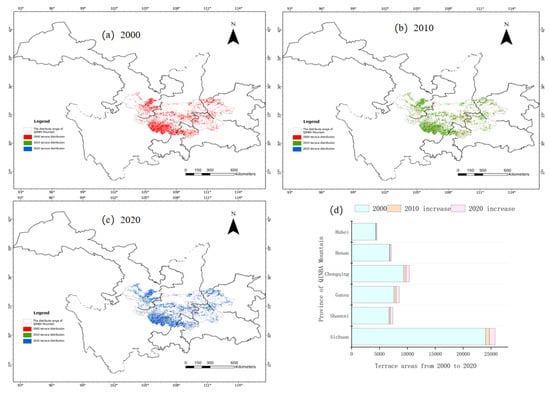

3.6. Terrace Distribution Change in Qinba Mountain

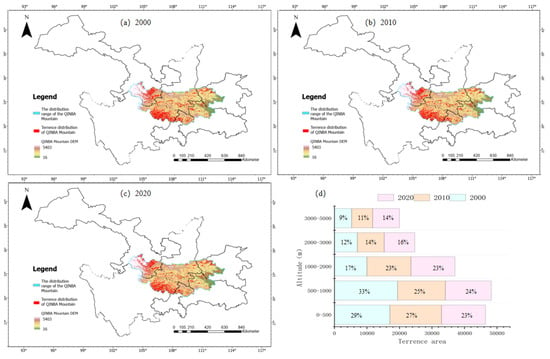

Using the most accurate DeepLabV3 model to interpret the distribution of terraced fields in the Qinba Mountains from 2000 to 2020, the results are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Distribution Patterns and Changes of Terraced Fields in the Qinba Mountains from 2000 to 2020. (a–c) Distribution patterns of terraced fields in the Qinba Mountains from 2000 to 2020. (d) Changes in the distribution of terraced fields across provinces in the Qinba Mountains from 2000 to 2020.

From 2000 to 2010, the total area of terraced fields increased from 57.834 km2 to 59,668 km2, representing a net increase of 2844 km2 over the decade. The average annual growth rate was approximately 0.44%, indicating relatively stable expansion. 2010–2020: The total area expanded from 59,668 km2 to 63,742 km2. Over the decade, the net increase was 3074 km2, with an average annual growth rate of approximately 0.51%, indicating a significantly accelerated growth rate. The trend over the 20-year period showed a pattern of initially slow growth followed by accelerated expansion.

Analysis of terrace area changes and spatial distribution across provinces (Figure 8a–c) reveals pronounced regional heterogeneity in terrace expansion. Sichuan consistently maintained the largest terrace area, growing from 24,032 km2 to 25,729 km2 between 2000 and 2020. Its net increase of 1697 km2 accounted for 55.2% of the regional total, establishing Sichuan as the core growth area. Its spatial distribution is concentrated in the Daba Mountains of northern Sichuan. Shaanxi, Gansu, and Chongqing exhibit relatively balanced growth in terraced field area, with southern Shaanxi, southern Gansu, and northeastern Chongqing being the primary growth areas. Henan and Hubei provinces have the smallest terraced field areas and the slowest growth rates.

The changes in area across elevation gradients (Figure 9) reveal a pronounced vertical shift in terraced field distribution, with continuous reduction in low-elevation terraced areas. The 0–500 m zone decreased from 17,058.96 km2 in 2000 to 13,529.52 km2 in 2020, representing a net loss of 3529.44 km2. The 500–1000 m zone decreased from 19,411.92 km2 to 14,117.76 km2, a net reduction of 5294.16 km2. Conversely, terraced fields expanded significantly in the mid-to-high altitude zones. The 1000–2000 m zone increased from 10,000.08 km2 to 13,529.52 km2, a net gain of 3529.44 km2. This pattern of contraction at lower elevations and expansion at medium-to-high elevations reflects the vertical migration of terraced fields’ distribution center from lower to medium-to-high elevations.

Figure 9.

Distribution area of terraced fields in the Qinba Mountains at different elevations from 2000 to 2020. (a–c) Elevation distribution patterns of terraced fields in the Qinba Mountains from 2000 to 2020. (d) Changes in elevation distribution of terraced fields in the Qinba Mountains from 2000 to 2020.

4. Discussion

4.1. Application Evaluation of Deep Learning Model in Qinba Mountain

The Qinba Mountain region features fragmented terrain, complex climate, and highly heterogeneous terraced landscapes. It presents challenges such as numerous small, fragmented plots, significant topographical interference, and blurred field boundary demarcations, demanding high adaptability from deep learning semantic segmentation models. This study employed transfer learning using the pre-trained backbone network ResNet-34 and trained three common deep learning models for terraced field recognition in the Qinba Mountains. Results indicate that PSPNet exhibits adhesion artifacts, struggling to distinguish minute non-terrace areas within terraces. While U-Net improves upon this, it still produces scattered misclassifications. DeepLabV3 demonstrates significantly higher training accuracy than both U-Net and PSPNet, eliminating adhesion artifacts while maintaining sharp ridge edges. In testing with 15 m resolution imagery of the Qinba region, DeepLabV3 achieves an IoU of 77.26% and a Kappa coefficient of 71.48%. and a Kappa coefficient of 0.7148. Its adaptability to terrain interference significantly outperformed other models, making it the preferred technical solution for terrace extraction in this region.

Comparing the architectures of different models reveals that PSPNet’s core is the pyramid pooling module, which aggregates multi-scale contextual information through pooling operations at different scales, making it suitable for handling global context. Although it employs multi-scale pooling, its decoder is less refined than DeepLabV3 and U-Net. Furthermore, due to the high likelihood of occlusion between objects, edge extraction and segmentation become less precise, resulting in unclear boundaries and frequent merging. U-Net employs a classic encoder-decoder architecture, excelling in detail and boundary representation. It is well-suited for small targets and fine segmentation in remote sensing interpretation. However, its skip connections primarily fuse features at the same level, making it less effective than DeepLabV3 for handling multi-scale objects. Unlike the local receptive field achieved through layer-by-layer downsampling and upsampling, DeepLabV3 replaces dilated convolutions with cascaded dilated convolutions. enabling a single network to process global context. By concurrently employing dilated convolutions with varying dilation rates, it expands the receptive field without sacrificing image resolution. Furthermore, enhancements to the decoder architecture strengthen boundary details. These features enable high-precision recognition in mountainous terraced fields characterized by scattered, fragmented structures and severe shadow interference.

The stratified analysis demonstrates that the model’s accuracy is not uniform but is instead highly contingent on the topographic context. The model excels in environments that are archetypal for mid-altitudes with moderately steep slopes. Based on it we create a set of tiles integrating multi-source data from RBG and DEM. The fusion model, which incorporates DEM-derived topographic data, demonstrates improvement across these aspects. The visual results of this ablation study unequivocally demonstrate that for geographic features like terraces, whose very definition is intrinsically tied to their 3D morphology, relying on 2D spectral and textural information presents inherent limitations. By fusing DEM data, the model gains direct perception of the landform’s structure, leading to fundamental improvements in the completeness, boundary accuracy, and discriminative power of the segmentation.

4.2. Analysis of Driving Forces Behind Terraced Field Distribution in the Qinba Mountains

The dynamic evolution of mountainous terraced fields is a complex process influenced by multiple interacting factors. A correlation analysis was conducted between the distribution density of terraced fields in the Qinba Mountains and settlement density, precipitation, vegetation coverage, elevation, and slope gradient (Table 3). Results indicate that slope gradient, elevation, distance from roads, and settlement density are factors significantly contributing to terraced field area. This indicates that in low-elevation areas, urban expansion and the Grain-for-Green Program have led to significant reductions in terraced fields. Conversely, in mid-to-high elevation zones, fragmented terrain and scarce flat land make terraced fields a vital source for expanding cultivated areas. Slope exhibits a highly significant positive correlation with terraced field density, indicating that steep slopes are concentrated in terraced field zones. Given the Qinba Mountains’ steep slopes and deep valleys, terraced fields primarily originate from villagers’ conversion of slope farmland. Settlement density also exhibits a significant positive correlation with terraced field density, indicating a strong coupling between terraced field distribution and human habitation. Villages in the Qinba Mountains predominantly cluster along river valleys and gentle slopes, where surrounding terraced fields have become the primary farming method for residents.

Table 3.

Correlation Analysis of Environmental Factors in the Qinba Mountains.

Spatial statistics were conducted on several key influencing factors, including elevation and slope (Figure 10). The analysis revealed that the primary distribution area for terraced fields is between 500–1000 m elevation and 15–30° slope. Statistical analysis of the distance between terraced fields and settlements reveals that approximately 70% of terraced fields are concentrated within a two-kilometer radius of roads and settlements. As distance increases, the area of terraced fields shows a clear downward trend. This indicates that topography and accessibility conditions determine the patch quality of terraced fields, controlling both their evolutionary direction and quantity.

Figure 10.

Terrace distribution area spatial statistics.

5. Conclusions

This study employs three neural network models—DeepLabV3, U-Net, and PSP-Net—to extract terraced fields from 15 m-resolution remote sensing imagery. It investigates the accuracy of different models in interpreting terraced fields in the Qinba Mountains and analyzes the distribution changes and driving factors of terraced fields from 2000 to 2020. Key findings are as follows:

- Through transfer learning using the pre-trained ResNet-34 backbone network, three common deep learning models (DeepLabV3, U-Net, and PSPNet) were trained for terrace identification in the Qinba Mountains. DeepLabV3 achieved a mean pixel accuracy (MPA) of 79.42%, an intersection-over-union (IoU) of 77.26%, an F1 score of 80.98, and a Kappa coefficient of 0.7148—all outperforming U-Net and PSPNet models, demonstrating the highest accuracy for Qinba terracing classification. The model’s accuracy is not uniform but is instead highly contingent on the topographic context. The model excels in environments that are archetypal for mid-altitudes with moderately steep slopes. Based on it, we create a set of tiles integrating multi-source data from RBG and DEM. The fusion model, which incorporates DEM-derived topographic data, demonstrates improvement across these aspects.

- Between 2000 and 2020, terraced fields in the Qinba Mountains exhibited an increasing trend: the total area of terraced fields in the Qinba region was 57.834 km2 in 2000, growing to 63,742 km2 by 2020, representing an increase of approximately 10.22%. Sichuan, Gansu, and Shaanxi provinces contributed the majority of the new terraced field area, accounting for 71% of the increase. Slope gradient, elevation, distance from roads, and settlement density were the factors most significantly contributing to terraced field expansion. Low-elevation areas experienced substantial terraced field reduction due to urban expansion and the Grain-for-Green Program. Conversely, in medium-to-high elevation zones, fragmented terrain and scarce flat land made terraced fields a vital source for expanding cultivated areas.

- The study has certain limitations. While 15 m-resolution imagery achieved good accuracy in identifying terraced fields in the Qinba Mountains, it remains constrained in detecting fragmented terraces smaller than 100 m2. It is necessary to focus on other uncertainties, such as satellite models, image resolution, provinces, terrain, and even optical bands, in future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.M. and P.S.; methodology, X.M.; software, Z.S.; validation, X.C. and P.S.; formal analysis, P.S.; investigation, X.C.; data curation, X.C.; writing—original draft preparation, X.M.; writing—review and editing, P.S.; visualization, Z.S.; supervision, X.M.; project administration, P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant: 2024YFF1306504).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author, Peng Shi, upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, R. Research on the Spatial System of Qinba Mountains National Park and Nature Reserves. Chin. J. Eng. Sci. 2020, 22, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Feng, Q.; Chen, L. Ecosystem Services of Soil and Water Conservation Engineering Measures on the Loess Plateau. Resour. Sci. 2020, 42, 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Shi, M.; Zhao, X.; Wang, X.; Luo, Z.; Zhao, Y. Methods for automatic identification and extraction of terraces from high spatial resolution satellite data (China-GF-1). Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2017, 5, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. Research on Extracting Soil and Water Conservation Information Based on Spot5 Remote Sensing Images. Master’s Thesis, Northwest University, Xi’an, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q. Research on Extraction Methods for Soil and Water Conservation Measures Based on Texture Features of High-Resolution Remote Sensing Images. Master’s Thesis, Northwest University, Xi’an, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y. Feasibility Analysis of Extracting Terraced Field Images Using Fourier Transform of Domestic Gaofen-1 Satellite Data. Chin. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2016, 63–65+73, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, F.; Sun, W. Research on Extracting Terraced Field Information from SPOT Satellite Images Based on Object-Oriented Approach. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2016, 23, 345–351. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, P.; Cheng, T.; Yao, X. Machine Learning Paradigms in High-Resolution Remote Sensing Image Interpretation. J. Remote Sens. 2021, 25, 182–197. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.; Liu, X. Research Status and Development Trends in Remote Sensing Image Interpretation. Remote Sens. Land Resour. 2004, 7–10+15, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Tian, J.; Ma, Q.; Jin, X.; Yang, Z.; Yang, P. Dynamic Monitoring of Loess Terraces Based on Google Earth Engine and Machine Learning. J. Zhejiang AF Univ. 2021, 38, 730–736. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Lai, G. Enhancement and Extraction of Small-Scale Terraced Field Texture Information in High-Resolution Remote Sensing Images. Jiangxi Sci. 2020, 38, 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y. Research on Terraced Field Extraction Methods Based on UAV Imagery and Slope Data. Master’s Thesis, Northwest A&F University, Xi’an, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Deep Learning-Based Identification and Extraction of Terraced Fields in Southern Hilly Regions. Master’s Thesis, Huazhong Agricultural University, Xi’an, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y. Research and Application of Deep Learning-Based Feature Extraction Techniques for Remote Sensing Images. Master’s Thesis, Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Zou, J.; Liu, S.; Xie, Y. Terrace Extraction Method Based on Remote Sensing and a Novel Deep Learning Framework. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Lin, A.; Wu, H.; Wu, Z.; Wu, W.; Yu, Q. JAM-R-CNN Deep Network Model for Terrace Remote Sensing Recognition. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 28, 3136–3146. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, S.; Lin, N. Water Edge Extraction Based on Semantic Segmentation Model and Remote Sensing Image Band Expansion. Radio Eng. 2025, 55, 1256–1264. [Google Scholar]

- Alshehhi, R.; Marpu, P.R.; Woon, W.L.; Mura, M.D. Simultaneous extraction of roads and buildings in remote sensing imagery with convolutional neural networks. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2017, 130, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Cao, W. A High-Resolution Road Extraction Method for Remote Sensing Images Using an Improved DeepLabV3+ Network. Remote Sens. Inf. 2022, 37, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K. and Yuille, A.L. DeepLab: Semantic Image Segmentation with Deep Convolutional Nets, Atrous Convolution, and Fully Connected CRFs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2018, 40, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badrinarayanan, V.; Kendall, A.; Cipolla, R. Segnet: A deep convolutional encoder-decoder architecture for image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 2481–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Rahman Siddiquee, M.M.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. UNet++: A Nested U-Net Architecture for Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis, Granada, Spain, 20 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Y.; Huang, Z. A Building Segmentation Method for Remote Sensing Images Based on an Improved UNet Network. Urban Surv. 2024, 109–113, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Li, X.; Xin, L.; Song, H.; Wang, X. Mapping the Terraces on the Loess Plateau Based on a Deep Learning-Based Model at 1.89 m Resolution. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Pyramid Scene Parsing Network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2881–2890. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.M.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, X.F. Evaluation of Landscape Quality in Traditional Villages of Guanzhong Based on PSPNet Deep Learning and Random Forest. West. For. Sci. 2025, 54, 128–134+142. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Hou, R.; Yang, X. Analysis of Remote Sensing Image Technology from the Perspective of Pre-trained Model Paradigm Transfer. Comput. Technol. Dev. 2025; 1–11, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).