Can Imports of Clean Energy Equipment Inhibit a Country’s Carbon Emissions? Evidence from China’s Manufacturing Industry for Solar PVs, Wind Turbines, and Lithium Batteries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Influence Mechanisms and Research Hypotheses

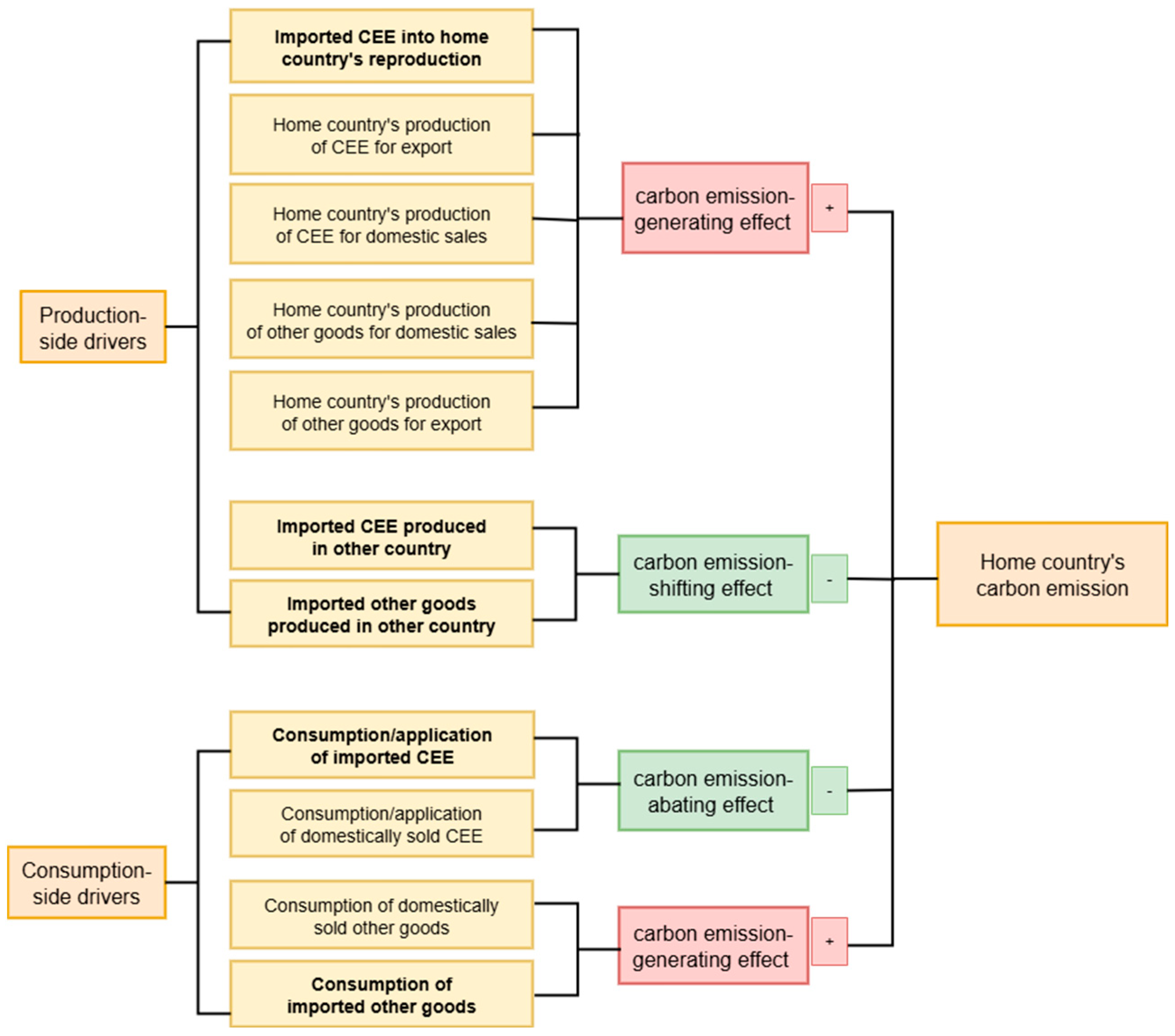

2.1. CEEMI’s Imports and Carbon Emissions: A Theoretical Framework

2.2. Mechanisms Analysis of How the Imports of the CEEMI Affects Carbon Emissions

2.2.1. GVC Participation

2.2.2. Technological Advance

3. Research Design

3.1. Model Specification

- (1)

- Baseline Model

- (2)

- Impact Mechanism Model

3.2. Description of Variables

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Explanatory Variable

3.2.3. Control Variables

- (1)

- Clean energy equipment exports (): Data on the exports of clean energy equipment is obtained from the customs database, categorized by the registered location of the exporters.

- (2)

- Domestic sales of clean energy equipment (): Considering data availability, and the fact that clean energy equipment is primarily used in power generation and optimizing the energy structure, we use the ratio of non-coal and non-nuclear electricity generation to total electricity generation as a proxy for domestic sales of clean energy equipment.

- (3)

- Other imports (): Imports of other goods, excluding clean energy equipment manufacturing imports.

- (4)

- Population density (): Measured as the ratio of population to administrative area, representing population density.

- (5)

- Per capita GDP (): Defined as the GDP of the province divided by its population size.

- (6)

- Energy efficiency (): Defined as the ratio of GDP to electricity consumption, reflecting the energy efficiency of a province.

- (7)

- Industrial structure (): Measured by the share of the tertiary sector in GDP, representing the structure of the local economy.

3.2.4. Mechanism Variables

- (1)

- GVC participation (): measures the depth of participation in the GVC by a country’s or region’s industry. It is a key indicator of the industry’s integration into the global production network. Following the method proposed by Koopman et al. (2014) [37], we calculated this index by summing forward (), as shown in Equation (5). The calculation formula for pt f is as follows: . GVC forward participation is the sum of simple GVC forward participation and complex GVC forward participation . Here, represents the value-added of various countries and industries, and represents the domestic value-added contained in exported intermediate goods. is the portion of the value-added in exported intermediate goods that is absorbed by the direct importing country for the production of domestically consumed goods, i.e., simple GVC. represents the portion of the value-added in exported intermediate goods that is absorbed by the direct importing country for the production of export goods, i.e., complex GVC [38]. () and backward GVC participation: The calculation formula for is as follows: . GVC backward participation is the sum of simple GVC backward participation and complex GVC backward participation . Here, represents the value-added of the final output of various countries and industries, and represents the value-added contained in imported intermediate goods. is the portion of the value-added in imported intermediate goods used for the production of domestically produced consumer goods, i.e., simple GVC. represents the portion of the value-added in imported intermediate goods used for the production of export goods or returned to the home country, i.e., complex GVC [38]. The larger the , the greater the extent to which a country’s industry participates in the division of labor within GVC.

- (2)

- Green technological progress is a core driver in environmental economics, often represented by the number of green patent grants. An increase in patent numbers typically indicates technological advancements, which can reduce carbon emission intensity by improving production efficiency and energy utilization [48]. Therefore, we use green patent grants (Patent) as an indicator of technological innovation’s role in emission reduction.

3.3. Data Sources

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Benchmark Regression Results

4.2. Endogeneity Test

4.3. Robustness Tests

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.4.1. Heterogeneity of Economic Development Level

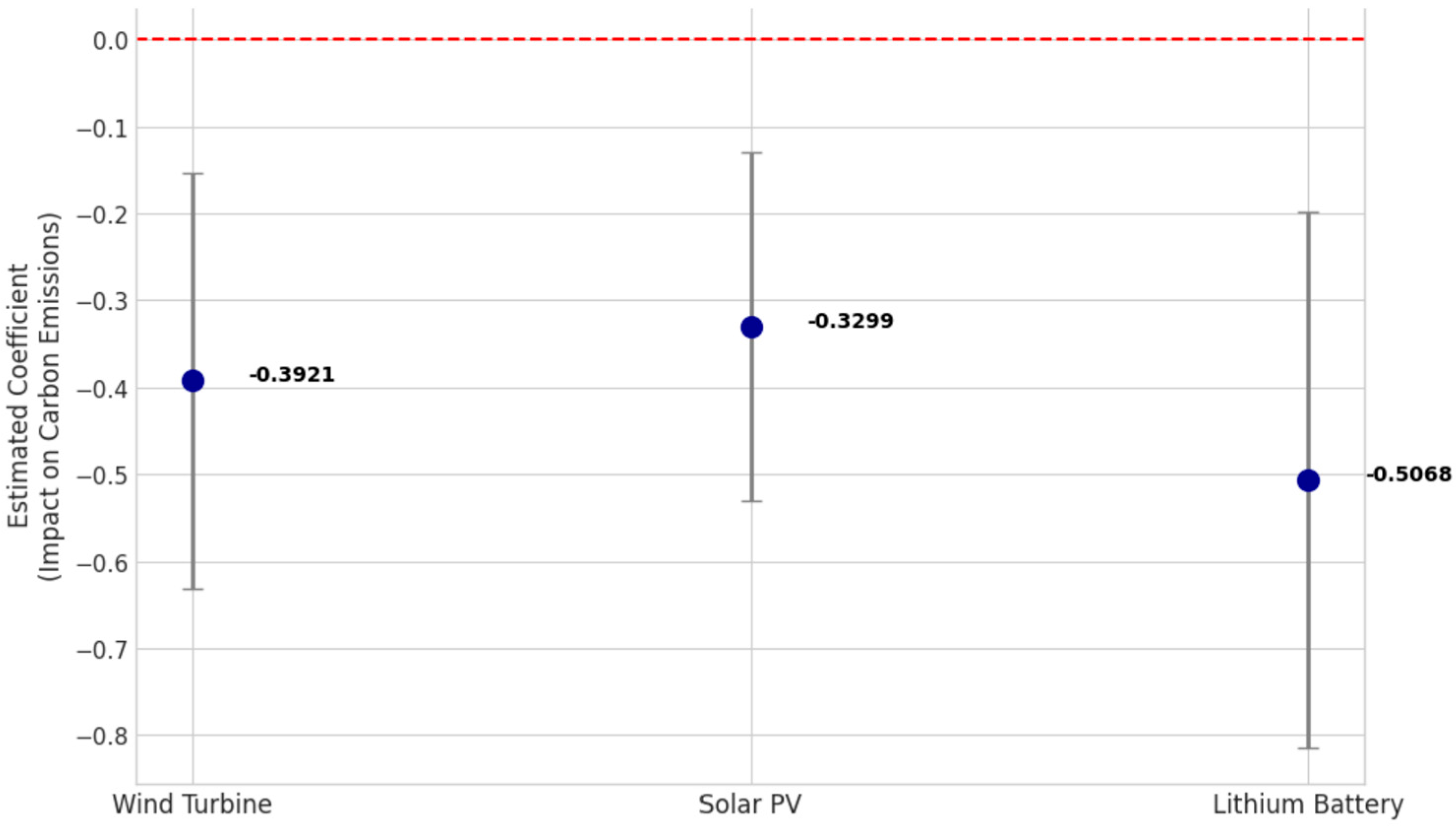

4.4.2. Heterogeneity of Product

4.4.3. Heterogeneity of Provinces of Different Industrial Structure

4.5. Mechanism Test

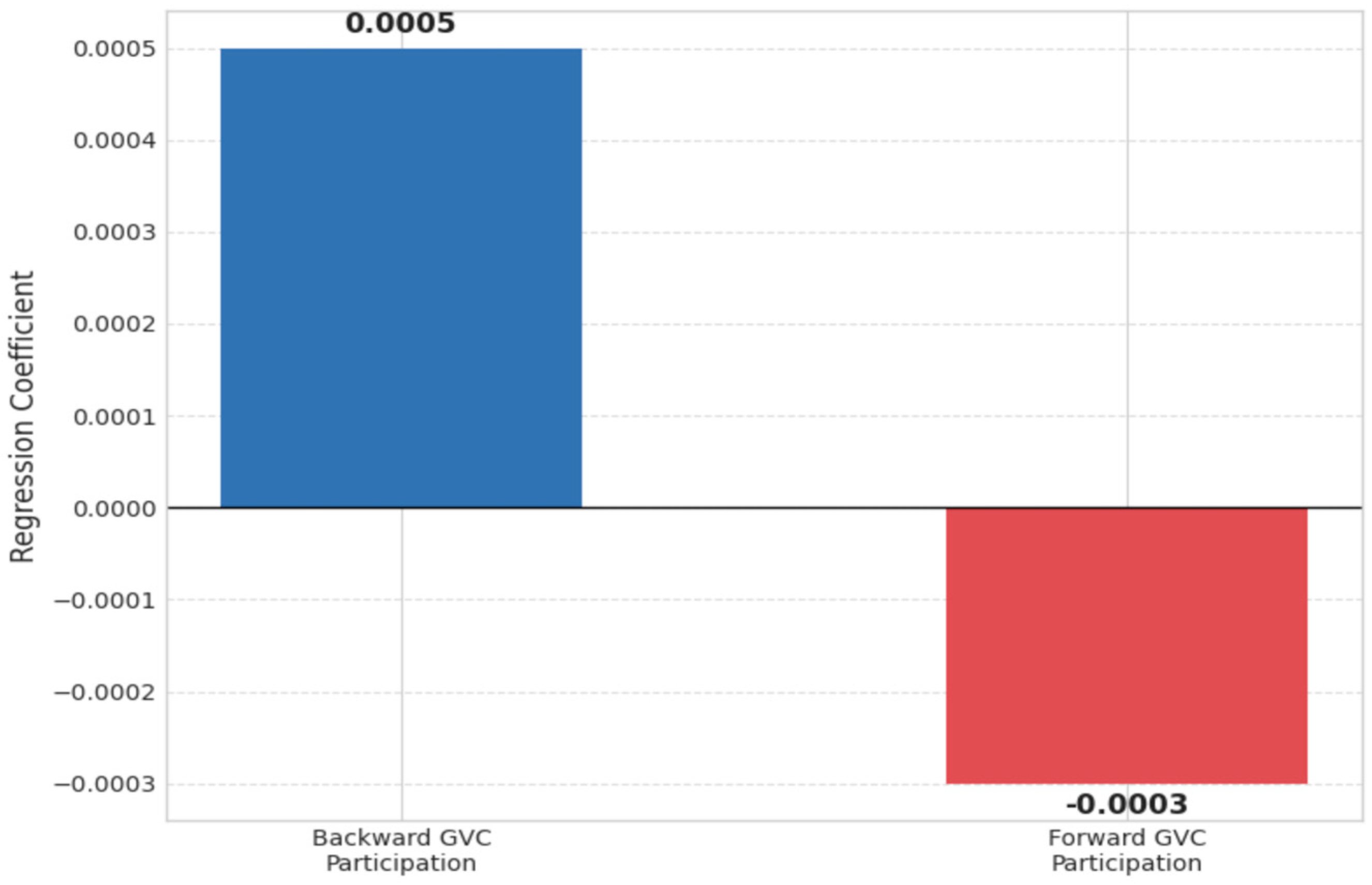

4.5.1. GVC Participation

4.5.2. Technological Advance

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Copeland, B.R.; Taylor, M.S. Trade, growth, and the environment. J. Econ. Lit. 2004, 42, 7–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellenberg, D.K. An empirical investigation of the pollution haven effect with strategic environment and trade policy. J. Int. Econ. 2009, 78, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antweiler, W.; Copeland, B.R.; Taylor, M.S. Is free trade good for the environment? Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 877–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grether, J.-M.; Mathys, N.A.; de Melo, J. Scale, technique and composition effects in manufacturing SO2 emissions. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2009, 43, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, A. Technology, international trade, and pollution from US manufacturing. Am. Econ. Rev. 2009, 99, 2177–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunel, C. Pollution offshoring and emission reductions in EU and US manufacturing. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2017, 68, 621–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, J.S.; Walker, R. Why is pollution from US manufacturing declining? The roles of environmental regulation, productivity, and trade. Am. Econ. Rev. 2018, 108, 3814–3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, N.; Genakos, C.; Martin, R.; Sadun, R. Modern management: Good for the environment or just hot air? Econ. J. 2010, 120, 551–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.A. Energy Efficiency Gains from Trade: Greenhouse Gas Emissions and India’ s Manufacturing Sector. Mimeograph, Berkeley ARE. 2011. Available online: https://arefiles.ucdavis.edu/uploads/filer_public/2014/03/27/martin-energy-efficiencynov.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2014).

- Qi, J.; Tang, X.; Xi, X. The size distribution of firms and industrial water pollution: A quantitative analysis of China. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 2021, 13, 151–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, G.P.; Minx, J.C.; Weber, C.L.; Edenhofer, O. Growth in emission transfers via international trade from 1990 to 2008. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011, 108, 8903–8908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogmans, C. Can the terms of trade externality outweigh free-riding? The role of vertical linkages. J. Int. Econ. 2015, 95, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Li, Z.; Ma, T.; He, R. Carbon efficiency and international specialization position: Evidence from global value chain position index of manufacture. Energy Policy 2019, 128, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, R.; Zheng, X.; Zhao, Z. Carbon endowment and trade-embodied carbon emissions in global value chains: Evidence from China. Appl. Energy 2020, 277, 115592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, D.I. The environmental Kuznets curve after 25 years. J. Bioecon. 2017, 19, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wan, G.; Wang, C. Participation in GVCs and CO2 emissions. Energy Econ. 2019, 84, 104561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertwich, E.G. Carbon fueling complex global value chains tripled in the period 1995–2012. Energy Econ. 2020, 86, 104651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; He, Y.; Song, M. Global value chains, technological progress, and environmental pollution: Inequality towards developing countries. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 277, 110999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Qian, Z.; Zheng, L.; Wang, S. Global value chains participation and carbon emissions: Evidence from Belt and Road countries. Appl. Energy 2022, 310, 118505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Chen, S. Global value chains and carbon emission reduction in developing countries: Does industrial upgrading matter? Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 97, 106895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, S. Global value chains and carbon emission efficiency: Evidence from 30 provinces in China. Appl. Econ. 2024, 57, 7123–7138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Peters, G.P.; Wang, Z.; Li, M. Tracing CO2 emissions in global value chains. Energy Econ. 2018, 73, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z. Re-calculation of responsibility distribution and spatiotemporal patterns of global production carbon emissions from the perspective of global value chain. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 773, 145065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Zhao, Y.; Shi, Q.; Qian, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhu, J. Global value chains participation and carbon emissions embodied in exports of China: Perspective of firm heterogeneity. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 813, 152587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, P.R.; Holdren, J.P. Impact of Population Growth. Science 1971, 171, 1212–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya, Y. Impact of Carbon Dioxide Emission Control on GNP Growth: Interpretation of Proposed Scenarios; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change/Response Strategies Working Group: Paris, France, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- O’Mahony, T. Decomposition of Ireland’s carbon emissions from 1990 to 2010: An extended Kaya identity. Energy Policy 2013, 59, 573–581. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, T.; Rosa, E.A. Rethinking the environmental impacts of population, affluence and technology. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1994, 1, 277–300. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, T.; Rosa, E.A. Effects of population and affluence on CO2 emissions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Fang, Z.; Tang, Z. Effects of Imports and Exports on China’s PM2.5 Pollution. China World Econ. 2020, 28, 28–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanov, F.J.; Khan, Z.; Hussain, M.; Tufail, M. Theoretical Framework for the Carbon Emissions Effects of Technological Progress and Renewable Energy Consumption. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 810–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jebli, M.B.; Madaleno, M.; Doğan, B.; Shahzad, U. Does export product quality and renewable energy induce carbon dioxide emissions: Evidence from leading complex and renewable energy economies. Renew. Energy 2021, 171, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Wu, C.; Feng, W.; You, K.; Liu, J.; Zhou, G.; Liu, L.; Cheng, H.-M. Impact of electric vehicle battery recycling on reducing raw material demand and battery life-cycle carbon emissions in China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edziah, B.K.; Sun, H.; Adom, P.K.; Wang, F.; Agyemang, A.O. The role of exogenous technological factors and renewable energy in carbon dioxide emission reduction in sub-Saharan African. Renew. Energy 2022, 196, 1418–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzer, D. The impact on domestic CO2 emissions of domestic government-funded clean energy, R&D; of spillovers from foreign government-funded clean energy, R&D. Energy Policy 2022, 168, 113126. [Google Scholar]

- Siewers, S.; Martínez-Zarzoso, I.; Baghdadi, L. Global value chains and firms’ environmental performance. World Dev. 2023, 173, 106395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, R.; Wang, Z.; Wei, S.J. Tracing value-added and double counting in gross exports. Am. Econ. Rev. 2014, 104, 459–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wei, S.-J.; Yu, X.; Zhu, K. Measures of Participation in Global Value Chains and Global Business Cycles. NBER Working Paper 23222. 2017. Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w23222/w23222.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Şeker, M.; Ulu, M.F.; Rodriguez-Delgado, J.D. Imported intermediate goods and product innovation. J. Int. Econ. 2024, 150, 103927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedyunina, A.; Averyanova, Y. Empirical Analysis of Competitiveness Factors of Russian Exporters in Manufacturing Industries. Econ. Policy 2018, 6, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, H.; Humphrey, J. Governance and Upgrading: Linking Industrial Cluster and Global Value Chain Research; IDS Working Paper No. 120; Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex: Brighton, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Veeramani, C.; Dhir, G. Do developing countries gain by participating in global value chains? Evidence from India. Rev. World Econ. 2022, 158, 1011–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Ji, T.; Yu, T. Reassessing pollution haven effect in global value chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 284, 124705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Jiao, J.; Tang, Y.; Han, X.; Sun, H. The effect of global value chain position on green technology innovation efficiency: From the perspective of environmental regulation. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Cai, H.H.; Jiang, Y.; Khan, N.U.; Qamri, G.M. The asymmetric effect of global value chain on environmental quality: Implications for environmental management. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Lei, H.; Zhou, Y. How does green trade affect the environment? Evidence from China. J. Econ. Anal. 2022, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Qayyum, M.; Li, S. Trade dynamics of environmental goods within global energy economy and their impacts on green technological innovation: A complex network analysis. Energy Econ. 2024, 140, 107957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Li, T.; Wu, S.; Gao, W.; Li, G. Does green technology progress have a significant impact on carbon dioxide emission? Energy Econ. 2024, 133, 107524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autor, D.H.; Dorn, D.; Hanson, G.H. The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States. Am. Econ. Rev. 2013, 103, 2121–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, P.J.; Kurniawati, S. Electricity subsidy reform in Indonesia: Demand-side effects on electricity use. Energy Policy 2018, 116, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith-Pinkham, P.; Sorkin, I.; Swift, H. Bartik Instruments: What, When, Why, and How. Am. Econ. Rev. 2020, 110, 2586–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubbak, M.H. The technological system of production and innovation: The case of photovoltaic technology in China. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 993–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Representative Studies | Focus | Main Mechanism Explored | Limitations | Contribution of This Paper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Trade and Environment | Copeland & Taylor (2004) [1]; Shapiro & Walker (2018) [7] | General Manufacturing/All Sectors | Pollution haven hypothesis (PHH); scale/technique effects | Treats all imports as similar; ignores the unique environmental impact of clean energy products. | Propose and verify the net emission-abating effect of CEEMI: production transfer + consumption substitution > reprocessing emission. |

| 2. GVC and Carbon Emissions | Meng et al. (2018) [22]; Wang et al. (2021) [18] | Aggregate Global Value Chains | GVC participation; embodied carbon in exports | Often uses aggregate GVC indices; results on environmental impact are mixed/inconclusive. | Distinguishes between backward and forward participation paths. |

| 3. Clean Energy Trade | Hasanov et al. (2021) [31]; Jebli et al. (2021) [32] | Clean Energy Consumption/Exports | Impact of clean energy’s consumption on growth/CO2 | Focuses on the use or export of energy; neglects the production and import of the equipment itself. | Focus on the import of CEEMI, analyzing the net effect of production emission and usage abatement. |

| Variables | Obs. | Mean | Sd | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 690 | 5.3484 | 0.9429 | 0.6575 | 7.7378 | |

| 690 | 8.74461 | 2.9328 | 0 | 14.7621 | |

| 690 | 9.6161 | 2.7691 | 0 | 15.2219 | |

| 690 | 0.2247 | 0.2314 | 0 | 0.9189 | |

| 690 | 14.1614 | 1.8137 | 9.6928 | 18.5713 | |

| 690 | 7.6663 | 0.6812 | 4.0254 | 8.8250 | |

| 690 | 10.3753 | 0.8746 | 7.9707 | 12.3112 | |

| 690 | 2.1796 | 0.7031 | 1.06042 | 4.4568 | |

| 690 | 3.7737 | 0.1977 | 3.3534 | 4.4415 | |

| 420 | 0.0135 | 0.0232 | −0.01445 | 0.1500 | |

| 690 | 9.3643 | 1.8296 | 4.2484 | 13.6787 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.2466 *** | −0.1327 *** | −0.3012 *** | −0.1312 *** | |

| (0.0420) | (0.0400) | (0.0352) | (0.0407) | |

| 0.0583 ** | 0.0352 ** | 0.0637 *** | 0.0376 *** | |

| (0.0249) | (0.0145) | (0.0203) | (0.0139) | |

| −1.2451 *** | −1.0427 *** | −1.4376 *** | −0.4966 ** | |

| (0.1146) | (0.1962) | (0.1174) | (0.2002) | |

| 0.0279 | 0.0132 | 0.0344 ** | −0.0006 | |

| (0.0219) | (0.0117) | (0.0175) | (0.0113) | |

| 0.0655 | 0.0934 *** | −0.0560 | 0.0111 | |

| (0.0491) | (0.0294) | (0.0430) | (0.0302) | |

| 0.7755 *** | 0.8743 *** | −0.2537 * | 0.5404 *** | |

| (0.0778) | (0.0740) | (0.1373) | (0.1166) | |

| −2.1491 *** | −0.3849 * | −0.8909 *** | 0.2712 | |

| (0.1992) | (0.2275) | (0.2402) | (0.2341) | |

| −0.6872 *** | −0.6399 *** | −0.6799 *** | −0.5974 *** | |

| (0.0522) | (0.0715) | (0.0475) | (0.0679) | |

| _cons | 2.8587 *** | 0.2114 | 8.6415 *** | 1.5646 * |

| (0.4283) | (0.4640) | (0.8641) | (0.9361) | |

| Obs. | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 |

| R2 | 0.5878 | 0.8851 | 0.6426 | 0.9049 |

| Year FE Province FE | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Variable | Lag One Phase ) | Lag Two Phases ) | Instrumental Variable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (1) | (2) | (1) | (2) | |

| 0.9342 *** (0.0121) | −0.2976 *** (0.0397) | 0.8806 *** (0.0159) | −0.3461 *** (0.0337) | 0.0942 ** (0.0406) | −2.9284 ** (1.5221) | |

| Control Variable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year/Province FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs. | 660 | 660 | 630 | 630 | 690 | 690 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.9875 | 0.9743 | 0.8743 | |||

| Kleibergen–Paap rk LM statistic | 217.233 | 205.285 | 18.852 | |||

| Cragg–Donald Wald F statistic | 6225.264 | 2868.389 | 21.026 | |||

| Kleibergen–Paap rk Wald F statistic | 4590.158 | 2424.096 | 22.584 | |||

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.1225 *** (0.0402) | −0.1262 *** (0.0419) | −0.0975 *** (0.0327) | −0.1228 *** (0.0416) | −0.0684 ** (0.0308) | |

| Control Variable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year/Province FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| AR (1) | 0.007 | ||||

| AR (2) | 0.115 | ||||

| Hansen test | 0.829 | ||||

| Obs. | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 | 660 |

| R2 | 0.9466 | 0.8875 | 0.9288 | 0.8966 |

| Variable | Low-Income | Middle-Income | High-Income |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0342 (0.0528) | −0.0684 (0.0936) | −0.2809 *** (0.0755) | |

| Constant | 0.8485 (1.7847) | 4.3920 * (2.3681) | −0.7180 (1.9873) |

| Obs. | 230 | 230 | 230 |

| R2 | 0.9567 | 0.8755 | 0.9195 |

| Control Variable | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Province FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Variable | Industry-Dominated Provinces | Service-Dominated Provinces |

|---|---|---|

| −0.1324 ** (0.0635) | −0.0549 (0.0377) | |

| Constant | 4.8236 (2.9394) | 0.8039 (1.1055) |

| Obs. | 345 | 345 |

| R2 | 0.8496 | 0.9448 |

| Control Variable | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

| Province FE | Yes | Yes |

| Variable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| −0.0003 ** (0.0001) | 0.0005 *** (0.0002) | 0.0008 *** (0.0003) | 0.0681 ** (0.0337) | |

| Constant | −0.0854 *** (0.0133) | −0.0999 *** (0.0195) | −0.1856 *** (0.0321) | 2.8293 *** (0.7707) |

| Obs. | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 |

| R2 | 0.9175 | 0.8799 | 0.9021 | 0.9817 |

| Control Variable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Province FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Z.; Cui, W. Can Imports of Clean Energy Equipment Inhibit a Country’s Carbon Emissions? Evidence from China’s Manufacturing Industry for Solar PVs, Wind Turbines, and Lithium Batteries. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10972. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410972

Li Z, Cui W. Can Imports of Clean Energy Equipment Inhibit a Country’s Carbon Emissions? Evidence from China’s Manufacturing Industry for Solar PVs, Wind Turbines, and Lithium Batteries. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):10972. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410972

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Zhaohua, and Wenxin Cui. 2025. "Can Imports of Clean Energy Equipment Inhibit a Country’s Carbon Emissions? Evidence from China’s Manufacturing Industry for Solar PVs, Wind Turbines, and Lithium Batteries" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 10972. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410972

APA StyleLi, Z., & Cui, W. (2025). Can Imports of Clean Energy Equipment Inhibit a Country’s Carbon Emissions? Evidence from China’s Manufacturing Industry for Solar PVs, Wind Turbines, and Lithium Batteries. Sustainability, 17(24), 10972. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410972