Abstract

Given the uncertainty from renewable production, local loads and battery operating states in microgrid, it is vital to develop an efficient energy management scheme to improve system economics and enhance grid reliability. In this paper, we consider a renewable integrated microgrid scenario including an energy storage system (ESS), bidirectional energy flow from/to conventional power grid and ESS health estimation. We develop a novel demand response-based scheme for microgrid energy management with a long short-term memory (LSTM) network and reinforcement learning (RL), aiming to improve the system operating profit from energy-trading and reduce the battery health cost from energy-scheduling. Specifically, to overcome the uncertainty from future, we utilize LSTM to forecast the unknown demand and electricity price. To obtain the desired ESS control scheme, we apply RL to learn an optimal energy-scheduling strategy. To improve the critical performance of the RL paradigm, we propose a random greedy strategy to encourage exploration. Numerical results show that our proposed algorithm outperforms the baselines by improve the system operating profit by 8.27% and 17.31% while ensuring ESS operating safety. By integrating energy efficiency with sustainable energy management practices, our scheme contributes to long-term environmental and economic resilience.

1. Introduction

Microgrids, integrated with distributed energy generators, renewable energy sources, energy storage facilities, energy conversion facilities and loads, have received growing attention than traditional power grids due to high reliability and flexibility in recent years [1,2]. As a controllable unit, the microgrid, through its energy conversion equipment, can utilize the forecasting and scheduling modules to quickly respond to various kinds of demands in urban areas so as to achieve uninterrupted power supply and reduce distribution losses [3,4]. In most medium-scale microgrids, the power is generated by renewable energy sources, i.e., solar photovoltaic [5] and wind [6]. However, the highly integrated renewable energy brings great challenges to the microgrid instability due to its unpredictability, intermittency and randomness [7,8]. Moreover, in areas where real-time pricing is deployed, customer demand and electricity price vary throughout the day and season [9,10]. All these constraints and uncertainties make the microgrid a complex system that the service providers should treat as a smart unit and make more profit through inter-connection with the main grid [11,12].

Demand response (DR) programs allow the consumers to reduce the energy consumption by generating and storing energy at specific times, providing more flexibility for the main grid while reducing energy expenses [13,14]. The dynamic pricing mechanisms commonly adopted in DR programs include time-of-use (TOU) rates, critical peak pricing (CPP), and real-time pricing (RTP) [15]. TOU and CPP employ price levels that remain fixed over relatively long predefined periods, whereas RTP exhibits more pronounced and frequent fluctuations in response to real-time system conditions [16]. RTP-aided incentive-based DR programs achieve about 93% of peak load reductions from existing DR resources in the U.S [17,18]. The widespread deployment of the DR program enables service providers (SPs) to profit from energy storage systems by purchasing relatively cheap energy to store during low peak hours and selling the energy during peak hours [19,20]. Besides, both load demand and power supply from distributed renewable generators also fluctuate greatly, but the ESS connected to the main grid can be employed to achieve the balance between generation and demand by peak load shifting [21,22]. However, owing to the increasing application of ESSs in microgrids, the estimation of degradation cost for ESSs has become a major obstacle to their participation in the electricity market [23]. Although existing studies examine battery health status, its impact on the operating costs of microgrid scenarios has been largely overlooked in prior work. In the context of global sustainability, energy conservation and battery health management play a central role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and enabling long-term renewable energy integration [24]. The demand response-based reinforcement learning framework we proposed directly supports sustainable energy use by promoting efficient scheduling and reducing unnecessary energy waste. Furthermore, by mitigating battery degradation, the system contributes to resource conservation and minimizes the environmental footprint associated with frequent battery replacement. This aligns with the broader goals of sustainable urban infrastructure and climate-resilient energy systems emphasized in the recent literature. Thus, our proposed DR-RQL not only advances technical efficiency but also strengthens the sustainable development pathway for modern microgrids.

In this work, we propose a novel DR-based energy scheduling framework with a long short-term memory (LSTM) network and reinforcement learning (RL) in a microgrid energy management system (EMS), aiming to maximize the SP’s operating profit and minimize the battery degradation cost. So far, two major issues in energy scheduling are still the main obstacles to their adoption in industry: model of battery health and uncertainty from the RTP/demand. To address the battery health problem, a module to monitor battery health is designed in the microgrid EMS, which is able to calculate the incremental operating cost caused by the battery degradation. To deal with the future uncertainties, LSTM is utilized to forecast future electricity price and demand based on existing RTP, and this process is repeated when new RTP and demands are updated by SPs. To ensure sufficient exploration in the real world, an RL-based Q-learning algorithm with a random greedy strategy is developed to fully interact with the microgrid environment. Afterward, in cooperation with the forecasted price and demand, Random Q-learning (RQL) is adopted to obtain the optimal operating profit by scheduling an ESS while reducing battery degradation cost as much as possible.

The main contributions are summarized as follows:

- An energy management system is proposed for microgrid scenario, including a renewable energy generator, an ESS and bidirectional energy flow with the main grid. Different from previous works, a battery health monitoring module is designed to calculate the ESS degradation cost.

- A novel DR-based reinforcement learning scheme is proposed for the above energy scheduling problem. To overcome the future price/demand uncertainties in presence of the rapidly updated RTPs, LSTM is adopted to forecast the unknown electricity price and demand.

- To improve profits through adequate exploration, a random greedy strategy-based Q-learning variant is proposed to derive the optimized ESS control policy. RQL is model-free, enabling the SP to determine the control actions in real time without knowing the system dynamics.

- An examination of the SP’s operating profit under three representative energy-scheduling baselines reveals that our proposed algorithm can improve the profit by 5.04–17.31% than the other, indicating that the DR-based RQL algorithm enables the SP to make more profit while keeping the ESS healthy.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the related works. Section 3 first introduces the microgrid EMS model and battery health model and then formulates the joint optimization problem. Section 4 transforms the optimization problem into an MDP problem and then introduces the DR-based RTP/demand forecasting algorithm and RQL-based energy scheduling scheme. Section 5 evaluates the performance of the proposed algorithm by simulations, and finally Section 6 concludes this paper. The main symbols used in this paper are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of Notations.

2. Related Work

Energy scheduling and ESS degradation: Until now, a great deal of works have been devoted to optimize operational cost in microgrid EMS with single or multiple energy generators or storages [25]. The conventional renewable generator and energy storage are studied in microgrid scenario and further transformed into a convex optimization problem, solved by modified Lyapunov optimization in [26], without considering ESSs healthy. An online energy management approach is proposed to manage local demand and EVs’ behaviors with stochastic optimization; however, the ESS degradation in [27] is modeled as a convex function, which is too idealistic to be adopted in reality. The authors of [28] study a grid-connected microgrid EMS including controllable distributed resources, renewable energy resources, an ESS and propose an RL-based scheme to minimize the real-time operation cost, which ignores the battery degradation cost. All these papers have considered the power grid with renewable production and ESS operations without incorporating battery health management. Meanwhile, in studies [29,30], a real market-based case study of battery health is conducted in grid applications. State of health (SoH) and end of life (EoL) are further introduced as indicators of battery health in [31], aiming to estimate the degradation cost of an ESS under price arbitrage and frequency regulation, with no renewable generator and SP participating.

DR program and RL: More recent works pay attention to the design of energy management mechanism under DR program in microgrid scenario. A day-ahead DR model, spanning three hierarchical levels including the microgrid operator, SPs and customer demand, is studied in the literature [32]. Then the Stackelberg game is utilized to analyze the coordination between different participants [33]. Similarly, the study described in [34] considers an integrated DR model and its application to electricity and natural gas systems based on mixed integer nonlinear programming (MINLP), wherein the customer demand is adjusted by DR strategy to minimize the energy purchase cost in engineering practice. Most studies have explored DR in the day-ahead markets, but real-time DR offers greater potential for balancing supply and demand [35,36,37]. So far, several studies attempted adopting RL to solve the energy scheduling problem under a real-time DR program in a microgrid EMS. An incentive-based DR program is developed in the literature [37,38] to manage both electricity cost and dissatisfaction cost from the perspective of customers by an artificial neural network and RL, wherein the multiple energy generations and ESSs are also considered. The studies in [39,40] develop RL algorithms to minimize the cost of energy consumption from controllable loads under the real-time DR scheme without any expert knowledge of the system dynamics. Therefore, in order to bridge the above research gap, this paper proposes a novel RTP-aid DR-based microgrid energy scheduling scheme using RL and LSTM methods.

3. System Model

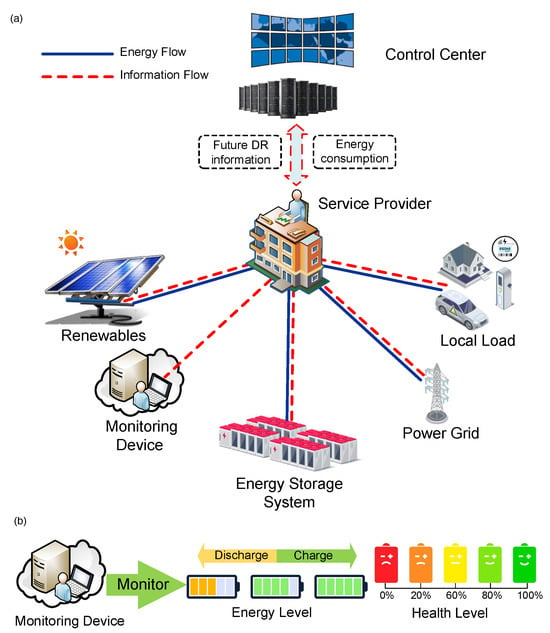

In this section, we consider an EMS in which the microgrid controller is equipped with an ESS and distributed energy generators, with the aim of achieving the highest operating profit. As shown in Figure 1, a bi-directional communication network connects both an EMS and SP, which plays a main role in exchanging the information between price and energy consumption. The microgrid controller integrates the future price and demand information from the forecasting module and then executes control actions of ESS according to demand response. In addition, the EMS is made up of a renewable energy generator (REG), an ESS and the local load, connected to the conventional power grid (CPG) for bi-directional energy flow. The mathematical model of the microgrid EMS, including the various operation constraints for the REG, ESS, CPG, are described in detail in the following subsections.

Figure 1.

(a) Microgrid energy management model. (b) A monitoring device for battery health.

3.1. Renewable Energy Generator

Renewable energy generation units in microgrid are limited by technology and climate conditions and thus need to meet the constraints of power generation [41]. At the same time, the REG should give priority to supplying local loads within any time period [42]. We denote as the amount of renewable energy production at time slot t and as the amount of local load at time slot t. The operation and supply constraints of power generation are denoted as

where represents the part of that served the consumers preferentially, and and denote the minimum and maximum amount of REG production. and denote the minimum and maximum amount of local load. The excess part of will be sold back to CPG through bidirectional energy flow, calculated as .

3.2. Service Provider

The service provider purchases energy from the CPG side through purchasing price and make profits by providing energy for the local load through selling price [43]. Both purchasing and price is announced by the utility company at the beginning of time slot t, which are bounded by

where and are the upper and lower bounds of energy-purchasing price, and are the upper and lower bounds of energy-selling price, respectively. To avoid energy arbitrage, the purchasing price should be strictly higher than selling price [44].

3.3. Battery Dynamic Model

The energy storage system is a necessary component for the service provider to obtain profits from consumers. The ESS should meet its own capacity constraints, charging/discharging amount constraints and energy balance constraints during operation [45]. Let be the amount of energy charging to the ESS, and denotes the amount of energy discharging from the ESS. The ESS cannot work in the charging and discharging patterns simultaneously in practical application [26], so and should meet the constraints as follows:

where and are the maximum charging and discharging energy of the ESS at time slot t.

We introduce the state-of-energy (SoE) to describe the dynamic energy change of the battery [46], denoted as . Considering the battery charging/discharging operations and charging/discharging inefficiency, the dynamic change of the battery evolves over time as

where and represent the upper and lower bounds of battery SoE. and represents the battery charging and discharging inefficiency, respectively.

3.4. Battery Health Model

State of health is utilized to estimate the cumulative capacity loss of battery, which is caused by battery degradation. In the existing works [31], battery degradation is divided into calendar aging and cycle aging. Calendar aging is the natural reduction of battery over time t [29,31]. Cycle aging is caused by the charging and discharging cycles of the battery, which is defined as cycle depth. According to the charging and discharging actions in (3) and (4), the cycle depth at the time slot t is denoted as

where is the ESS capacity. The SoH of the ESS depends on the charging and discharging cycles [47], modeled as

where is the battery SoH at the time slot t, and , , are the degradation coefficients decided by the battery types and the values are obtained from the empirical experiments. We define as the battery back replacement cost, and the degradation cost of ESS can be calculated as

In addition to the cycle depth, over-charging and over-discharging can lead to extreme SoC levels, which significantly reduce the battery lifespan. However, we can avoid over-charging and over-discharging by enforcing upper and lower limits on the SoC via the battery controller. In this work, the battery SoC is limited to the range of [0.1, 0.9].

3.5. Pricing Model

During energy dispatch, the balance of supply and demand must be met, and the EMS fills the shortage between demand and production by purchasing power from CPG [48]. At the beginning of each time slot t, the microgrid controller measures the REG production and the ESS input/output energy and then determines the amount of electricity purchased from CPG, expressed as

where represents the amount of electricity from CPG, and is the upper bound of electricity-purchasing amount. The profit of microgrid EMS at time slot t is mainly from trading electricity between CPG and customers, denoted as

The operating cost of the microgrid EMS at the time slot t is mainly from the ESS degradation cost , so the operating revenue for the microgrid EMS at every time slot t can be calculated as .

3.6. Objective Function

Based on the system components described in the previous subsections, we deduce the system input variable as and the decision variable at the time slot t. The target of the EMS is to find an optimal control policy (i.e., a mapping : wherein ) to not only maximize the operating revenue but also reduce the ESS degradation cost as much as possible. The objective function is expressed as

P1 is NP-hard, leading to high computational complexity as the T goes infinite [1,26,49]. The challenges of solving P1 are two-fold. First, P1 needs the statistics for future information which is difficult to obtain, i.e., the uncertainty of REG production, electricity price as well as demand. Thus, the energy scheduling algorithm should only rely on the current or previous information of the system input. Second, the energy and health level of the ESS is time-coupled; i.e., the next states , rely on the current states , according to the Equations (5) and (8). Therefore, the control policy for P1 should consider both the present and future. As a result, we transform the joint optimization problem into an MDP problem and adopt DRL to design an energy-scheduling approach in order to meet all above constraints and provide an asymptotically optimal resolution for P1 with system-operating profit being increased as much as possible.

4. RL-Based Demand Response Energy Scheduling Algorithm

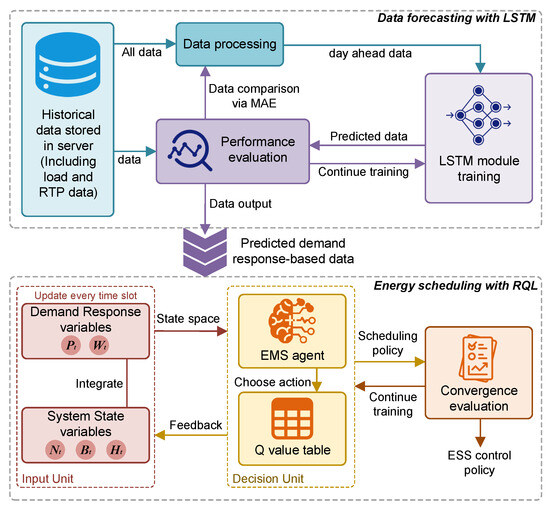

In this section, we propose a day-ahead energy scheduling paradigm for the EMS under the microgrid scenery utilizing the LSTM and Q-learning variant. To deal with the uncertainty of demand response, an LSTM module is designed to forecast the day-ahead electricity price and demand. After that, the Random Q-learning is adopted to derive the optimal energy-scheduling policy for the ESS. The details of LSTM module and Q-learning variant are introduced as follows.

4.1. MDP Reformation

In this work, the NP-hard P1 is reformulated into the Markov Decision Process (MDP) problem for the reason that the ESS health and energy level is up to the current energy price, local load and the EMS control signal, which is independent of the previous control actions and system states, satisfying the MDP property [49]. The MDP is divided into a quadruple where S represents the set of states, A represents the set of actions, R represents the reward function and is the discount factor. The EMS working as the agent searches the optimal control strategy through trial and error learning. The elements of will be described in detail as follows.

4.1.1. State

First, we divide one day into 48 time slots, i.e., half an hour for each time slot. The manually integrated state space S for the microgrid EMS comprises two types of information, i.e., timing information (TI) and controlled plant information (CPI). In this work, TI refers to the electricity price/load, which are announced by the current time slot tending to be cyclically under diurnal variation and the REG production varying periodically under seasonal variation. CPI includes the ESS energy level and health level influenced by control actions in (5), (8). To sum up, the state space of EMS at the time slot t is defined as

4.1.2. Action

4.1.3. Reward

Considering the NP-hard problem P1, the designed reward function comprises the reward for energy-trading in (13), the reward for ESS degradation in (10) and the penalty for over-charging and over-discharging in (6). The first part of reward function is the EMS operating profit deduced from (14), denoted as

where is the reward for energy-trading, and represents the reward for ESS degradation. The penalty for over-charging/discharging is denoted as

where is the penalty coefficient. To sum up, the reward at the time slot t is deduced as

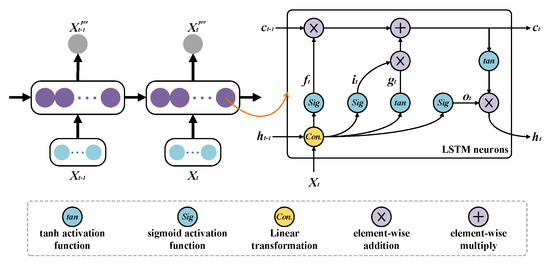

4.2. Demand Response Forecasting with LSTM

The variation in electricity price is a manifestation of DR, reflected in the fact that electricity price will increase when demand is high and decrease when demand is low. This work designs an LSTM-based module to extract the temporal feature from the day-ahead data announced by service providers and predicts the demand and electricity price of the next day for EMS decision making. LSTM, as a novel nonlinear function approximator [50], performs well in handling temporal relationship problems, i.e., load forecasting. The structure of the LSTM module is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The structure of the LSTM module.

Appropriate input selection for LSTM is a key factor in the success of demand response forecasting. For this energy scheduling algorithm, the input variables for the LSTM neurons contain the maximally correlated historical information, denoted as .

where , is the electricity price and demand for the past j time slots. The processed information from the previous neurons , and the output are the features extracted from the historical demand response. The detailed forward propagation process for LSTM can be described as follows:

where W and b denote the weight matrix and bias vectors, and and represent the sigmoid and hyperbolic tangent activation functions, respectively. is the input gate that determines what information from memory state should be saved into the current cell state ; is the forget gate utilized to decide what information from the previous cell state should be kept on the current cell state ; and is the output gate that decides how much information from the current cell state can be retained. Finally, the desired output for the LSTM layer can be obtained.

Afterward, the forecasting variables are derived through the fully-connected layer, calculated by . All the weight matrix and bias can be computed by the Adam optimizer, and the performance of the LSTM module is evaluated by mean absolute error (MAE) between the actual and forecasted values as follows:

4.3. Decision Making with Random Q-Learning

In Algorithm 1, the forecasting electricity price and demand from the LSTM module are concatenated with the current renewable generation, battery SoH and SoE level, and then integrated into the state space. Given the state space , we merge with into , because at every time slot t. Afterwards, we discretize the price into intervals, into intervals, into intervals and into intervals. Thus, the state space is deduced as

where refers to the price interval range from to , refers to the purchased energy interval range from to , refers to the SoE interval range from to , and refers to the SoH interval range from 0 to 1.

| Algorithm 1 RQL-Based DR Energy Scheduling Algorithm for Microgrid EMS |

| Require: , W, , , , the parameter for RQL |

| Ensure: , , the optimal Q-value table |

|

Different from the previous works, we introduce a Q-learning (QL) variant based on reinforcement learning to achieve the optimal energy-scheduling policy, denoted as Random Q-learning, which is described in detail in Figure 3 and Table 1. In this work, the microgrid scenery represents the environment and has its own agent EMS with different actions and corresponding rewards. The agent obtains the state information from the microgrid and executes the control action via random -greedy policy.

Figure 3.

Overall framework of the proposed RL-based DR energy-scheduling scheme. The offline forecasting and training process is performed once, while the online scheduling is conducted at each time t.

Random -greedy policy: Different from the traditional QL, we introduce the random -greedy policy as a trick to encourage agent to explore the environment. The tradition version of -greedy policy [51] is expressed as

and the random -greedy policy we proposed is expressed as

where is a generated random number, and is the greedy value. refers to the training episode, and represents the episode for exploration. After receiving the instant reward , the EMS moves to the next state, and the Q-value can be derived to quantify the performance of actions in the current state.

Q-value table: The optimal Q-value satisfies the Bellman equation, denoted

where is the discounting factor indicating the importance of the future reward. The Q-value is stored in the state-action table, wherein each item represents the value of performing a specific action in a specific state. The agent executes different actions at each time slot, and the corresponding Q-value is updated according to the Bellman equation in (13), as follows:

where is the learning rate for trading off the newly-acquired and old Q-value. The agent learns the optimal scheduling policy through trials and errors. At the same time, the Q-value of every state-action pair is updating and finally converges to the maximum after adequate iterations.

5. Case Study

5.1. Experiment Setup

In this section, a microgrid EMS case shown in Figure 1 is adopted to evaluate the performance of the proposed energy-scheduling algorithm. A day is divided into 48 time slots; i.e., each time slot incorporates 30 min. The intervals are set at = = = = 5. The ESS has a rate capacity of 2 MWh, and the efficiency of charging and discharging for the ESS is 0.95. The degradation coefficients of the battery are = 0.001, = −2, and = 0 according to empirical curve-fitting. Other parameters of EMS energy trading and algorithm are listed in Table 2. The renewable generation, the load profile and the electricity price are obtained from the National Electricity Market. The ESS, REG, Loads and SP are simulated using the real-time data. The whole training process is performed on a workstation with an Intel Core i7-9700K Processor 3.60 GHz and one Nvidia RTX 2060S. Once the training process is finished, the proposed approach can be used in the ESS charging and discharging scheduling. The agent takes less than 0.1s to output the control action, which can be used in real-time control.

Table 2.

Parameters of RQL training settings and model.

5.2. Performance of DR Forecasting Model

In DR forecasting, the proposed model utilizes the previous price and demand data from 1 June 2019 to 27 June 2019 for both training and testing. For a period of consecutive 30 days, the first 27 days of data are used for training, and the remaining 3 days are utilized to evaluate. Both price and demand data are fed into the slide window with a stride of 2, which results in 648 training pairs. After training, the model is saved to forecast unknown price and demand data for next 144 half-hours. The LSTM module is designed with an input layer containing two LSTM neurons, a hidden layer with eight neurons, and an output layer with one neuron. Furthermore, we introduce two benchmarks to compare with the LSTM module.

- BiLSTM [52]: Bi-directional LSTM (BiLSTM) is a modified version of LSTM. In this work, the input layer of BiLSTM contains one forward layer with two LSTM neurons and one backward layer with two LSTM neurons. The remaining structure is the same as the proposed LSTM module.

- ARIMA [53]:Auto-regressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) model is a widely used method for analyzing time-series data. In this work, the auto-regression degree is set at p = 50, the moving average degree is q = 1, and the order of differentiation is d = 5.

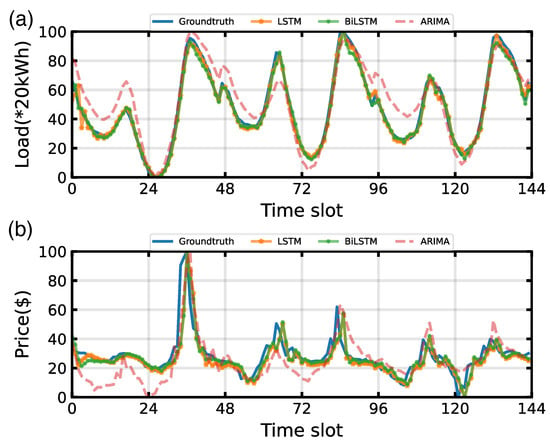

Specifically, the models above are trained and tested using data from the past 1296 time slots, i.e., 1 June 2019 to 27 June 2019, and then used to forecast the DR data for the next 144 time slots, 28–30 June 2019. Finally, we evaluate the performance of the models by visualizing the difference between forecasted data and actual demand response, as well as computing the MAE between the forecasted value and groundtruth.

Figure 4 shows the comparison between the forecasted data and groundtruth for the 144 time slots in summer pattern, where the orange, green and red line denote the predicted price/demand from LSTM, BiLSTM and ARIMA, respectively, the blue line represents the groundtruth. From the figure we can observe that both the LSTM and BiLSTM module can track the trend of actual price/demand accurately. Both models show high accuracy in forecasting strongly periodic data i.e., demand as shown in Figure 4a. However, there is a time lag between the weakly periodic data, i.e., price as shown in Figure 4b and the forecasting value which can be seen in the 65th, 83rd, and 111th time slot. Furthermore, the MAE for DR and computational time cost of the LSTM and the other two comparison models are shown in Table 3. We can observe that the DR forecasting performance of LSTM and BiLSTM is almost equal, and both are much better than ARIMA. However, LSTM is 72.3% faster than BiLSTM in terms of computation time. Afterwards, the forecasted price/demand will be integrated into state space for agent training.

Figure 4.

Demand response forecasting results during June 2019: (a) Load. (b) Electricity price.

Table 3.

Performance of the Forecasting Module.

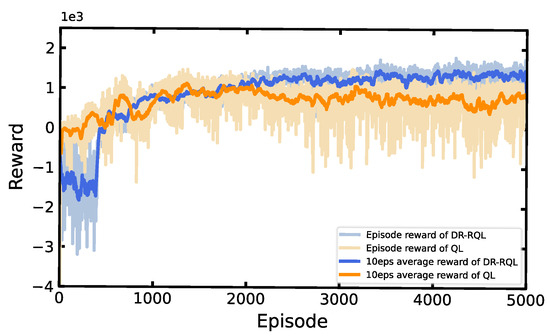

5.3. Performance Evaluation for DR-RQL

First, we evaluate the convergence of the DR-RQL algorithm with 5000 training episodes wherein each episode comprises 48 time slots. To demonstrate the performance more visually, we compare DR-RQL with QL by two metrics, i.e., the reward per episode and the average reward per 10 episodes, as shown in Figure 5. Both algorithms have the same parameter settings evaluated under the real-time environment. The difference is that the proposed DR-RQL utilizes a segmented modified -greedy strategy training in DR-forecasting-based state space, while the classical QL is training under the past price and demand data. The exploring episode for both DR-RQL and RQL is 400. During the early training stage, the reward of DR-RQL improves more slowly than QL, i.e., the reward of DR-RQL reaches −1634.12, while QL reaches 324.75 when training to the 400th episode; this is due to the fact that the agent of DR-RQL is in the exploration state and randomly selects actions to traverse the state-action value function in the first 400 training episodes. After that, the agent of DR-RQL shifts to the utilization state, selecting the action according to the maximum state-action value with a 90% probability, and still randomly selecting the action to explore with a 10% probability. At the same time, the reward of DR-RQL rises sharply and catches up with QL within 800 episodes. Ultimately, with enough exploring and utilizing, the reward curves of DR-RQL gradually stabilize and converge to greater value than QL; i.e., DR-RQL reaches 1215.61, while QL reaches 945.52 after 2200 episodes, which demonstrates that DR-RQL derives to the optimal energy-scheduling strategy by maximizing the cumulative reward in dynamic environment. Additionally, the reward curve continues to oscillate slightly for the reason that the agent of DR-RQL still keeps choosing random actions with a 10% probability.

Figure 5.

Comparison of average reward using RQL and QL on the microgrid EMS case during the training process.

Second, to gain insights into the economical superiority of the proposed DR-RQL energy scheduling algorithm, we compare it with other benchmark algorithms. Details of the benchmark algorithms are described as follows:

- RQL: This scheme utilizes the segmented modified -greedy strategy in (31) to update the Q-value table, training on the summer pattern dataset, i.e., 1–27 June 2019 for energy scheduling.

- QL [54]: This scheme is the vanilla version of the proposed method, utilizing the original -greedy strategy in (30) for action-selecting and training on the same dataset as RQL.

- Myopic [55]: This scheme pays more attention to current return and ignores the impact on future, as the EMS prefers to empty the battery storage while never guiding the battery to recharge only for maximizing the current reward.

- PSO [56]: Particle swarm optimization (PSO) is a heuristic optimization scheme widely used in microgrid scenarios for energy management. In this work, 100 random particles are generated in action space to evaluate the objective function P1. During each iteration, every particle adjusts its velocity and position to find the optimal solution. The maximum iteration is set at 1500, the inertia weight is w = 0.9, and the learning factor is = = 2.

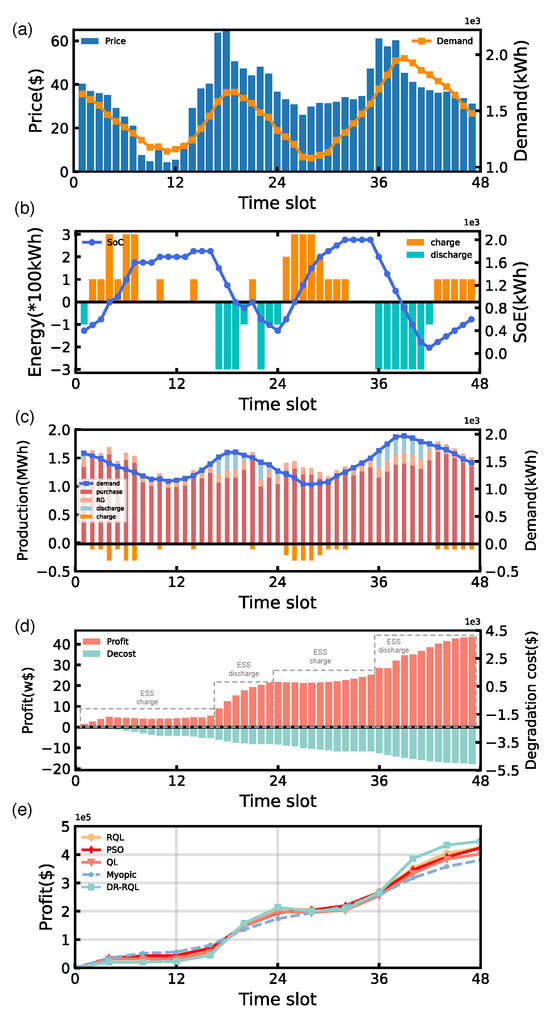

In this work, we compare the cumulative system operational profit defined as according to the (14) under the five different algorithms. As shown in Figure 6, DR-RQL outperforms the benchmark algorithms by achieving the highest profit and ensuring the battery operating safety. Figure 6e shows the cumulative EMS operational profits on the 48 testing time slot. Specifically, the total operating costs for RQL, PSO, QL, Myopic, and DR-RQL are USD 425.27K, USD 423.89K, USD 402.21K, USD 380.72K, and USD 446.72K, respectively. Compared with RQL, PSO, QL, and Myopic, DR-RQL improves the profit by 5.04%, 5.39%, 8.27%, and 17.31%, respectively.

Figure 6.

Operating results of DR-RQL for the microgrid EMS on 48 testing time slots: (a) Customer demand and electricity price. (b) Charging discharging energy and the SoE of the ESS. (c) Output of each dispatchable unit. (d) System profit and degradation cost during the EMS operation. (e) Comparison results with benchmark algorithms on cumulative system operational profit.

Figure 6 also shows the EMS operating results derived from DR-RQL on 48 testing time slots. From the figure we can observe that the ESS is scheduled in an efficient and economical manner to maximize the profit from purchasing electricity from the CPG side and selling it to customers, and the operating safety of the battery is strongly ensured. For instance, comparing Figure 6a,b, we can see that the ESS is scheduled to charge at off-peak hours to store energy and discharge to supply demand at peak hours. At the same time, the ESS is also appropriately operated to satisfy the maximum (under 2.0) and minimum (above 0.1) level of SoE to protect the battery.

Figure 6c shows the operation results of each unit based on DR-RQL in detail. Figure 6d shows the trend of operating profit and degradation cost during the EMS operation. The microgrid EMS operation results include energy trading with CPG, REG output, and the ESS charging and discharging energy under the real-world environment state. When the trading price is low (i.e., 0–16 h, 24–35 h), the ESS purchases energy from CPG to store, and the operating profit decreases slightly. When the trading price is high (i.e., 17–23 h, 36–48 h), the ESS releases stored energy to supply demand, and the operating profit rises significantly. Meanwhile, the degradation cost is rising due to the frequent battery operation. However, if the local load exceeds the supply capacity of microgrid EMS, the EMS will purchase energy from CPG directly. Finally, we can conclude from the results that the proposed DR-RQL method enables EMS to flexibly manage the dispatchable units in response to the microgrid environment. Further details are provided in Appendix A.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposes a novel real-time DR-based reinforcement learning algorithm for microgrid EMS energy scheduling, aiming to maximize SP’s operating profit while maintaining ESS health level. The microgrid EMS is modeled as a controllable unit comprised with renewable generator, ESS, bilateral energy flow with the main grid and the battery health monitoring module. Then, the optimization problem associated with energy scheduling is transformed into an MDP. To deal with the uncertainty from the real-time DR program, an LSTM network is utilized to extract discriminative features from the past RTP/demand sequences and generate predicted data for the next training process. Random Q-learning is presented to approximate the optimal control strategy, wherein the random greedy policy is proposed to improve algorithm performance by encouraging exploration. Ultimately, the effectiveness of the proposed DR-based reinforcement learning scheme is evaluated in comparison with other three baselines. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed energy scheduling scheme can converge to the optimal value at about 400 episodes with slight oscillation and make profits from microgrid EMS operation. Meanwhile, numerical results show that DR-RQL outperforms the vanilla Q-learning as well as the Myopic strategy by improve the SP’s operating profit by 8.27% and 17.31% while ensuring ESS operating safety.

Future work will be expanded in the following direction:

In this work, we propose a value-based RL algorithm, which is suitable for industrial environments that can be decomposed into limited discrete action and state spaces. Nowadays, many advanced reinforcement learning algorithms are proposed to handle continuous action and state spaceproblems, which means that we can feed continuous sequences of data directly to the agent for training without discretizing the input data. On the other hand, to enhance the algorithm’s adaptability across different microgrid scales, we plan to collect datasets from small community microgrids and adjust key parameters, such as ESS capacity, time resolution, and economic objectives, to enable comprehensive multi-scale evaluation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z. and K.D.; methodology, Z.C., Z.Z., S.G. and Y.H.; software, Z.C., Y.H. and X.L. (Xiaoyan Liu); validation, Z.C., X.L. (Xiaoyan Liu) and F.W.; formal analysis, K.D., Z.Z., S.G. and G.C.; investigation, H.Z., S.Y. and X.L. (Xiaoyan Liu); resources, H.Z., S.Y., S.X. and G.C.; data curation, K.D., Z.Z., S.Y. and F.W.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Z., Z.C. and S.G.; writing—review and editing, K.D., Z.Z. and S.Y.; visualization, H.Z., Z.C., S.G., S.X. and X.L. (Xiaoyan Liu); supervision, K.D., Y.H., X.L. (Xiaojie Liu), S.X., F.W., G.C. and X.L. (Xiaoyan Liu); project administration, H.Z.; funding acquisition, K.D., Y.H., X.L. (Xiaojie Liu), S.X., F.W., G.C. and X.L. (Xiaoyan Liu) All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the NSFC Programs under Grant 62403121.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

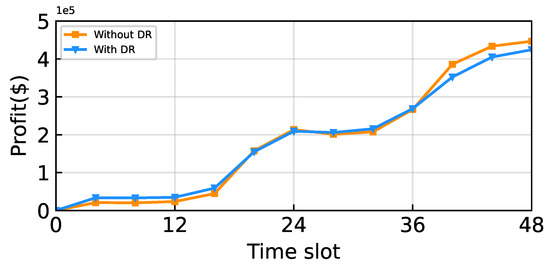

Appendix A. Diagnostic Experiment with LSTM Prediction Module

We further evaluated the operation of the ESS without predictive information, as illustrated in Figure A1. As shown in Figure A1, removing the LSTM-based prediction module results in a notable degradation in operating profit, with a reduction of 4.80%. Without access to essential forecasted signals, the agent is unable to formulate decisions that properly account for long-term returns, thereby diminishing the overall profitability of the system.

Figure A1.

Comparison of operating profit without LSTM prediction module.

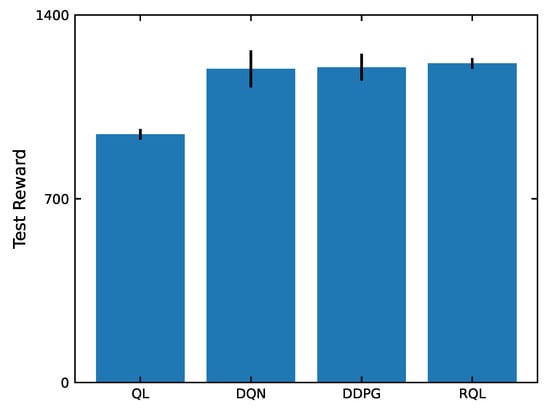

Appendix B. Performance Evaluation with Error Bars

In Figure A2, the blue bars indicate the average rewards from testing procedure, while the black lines indicate the standard deviation of the rewards. In the analysis shown in Figure A2, the results show that RQL achieved the highest average reward, followed by DDPG, DQN and QL, with average reward values of 1215.6, 1200.1, 1195.4 and 945.5, respectively, and standard deviation values of 19.7, 50.9, 70.6 and 20.8, respectively. Therefore, the algorithm with the highest stability remains the proposed RQL, followed by QL, DDPG and DQN. Thus, the experimental data confirms that the proposed RQL demonstrates the best performance and stability.

Figure A2.

Comparison of baseline performance after convergence with error bars.

Appendix C. Parameter Experiments

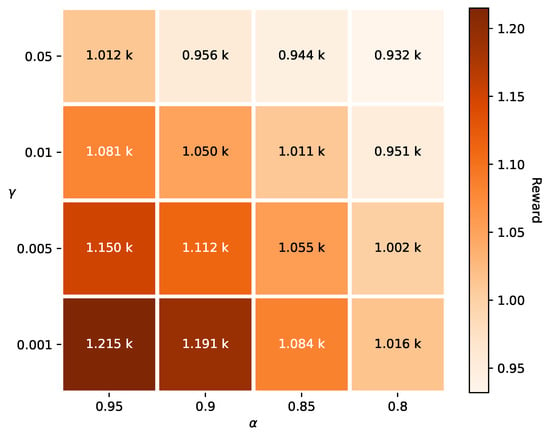

Figure A3 visualizes the effects of 16 combinations of , through a heatmap, where darker regions represent superior model performance. The experimental results clearly demonstrate that the parameter combination , produced the best performance, indicating that the combination achieves an ideal balance between bias and variance in reward function estimation. Above all, we accordingly determined the final parameter configuration.

Figure A3.

Heatmap comparison of model training effects under different (, ) combinations.

References

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, M.; Liu, Y. Load Forecasting-Based Learning System for Energy Management With Battery Degradation Estimation: A Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 70, 2342–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsamy, K.; Karuvelam, S. Modeling and Design of a Grid-Tied Renewable Energy System Exploiting Re-Lift Luo Converter and RNN Based Energy Management. Sustainability 2025, 17, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zha, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, L.; Fan, H. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Security-Constrained Battery Scheduling in Home Energy System. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 70, 3548–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Liu, H.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, G. Characteristic analysis and model predictive-improved active disturbance rejection control of direct-drive electro-hydrostatic actuators. Expert Syst. Appl. 2026, 301, 130565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhou, S.; Gu, W.; Zhuang, W.; Gao, M.; Chan, C.C.; Zhang, X. Coordinated planning model for multi-regional ammonia industries leveraging hydrogen supply chain and power grid integration: A case study of Shandong. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelis, G.F.; Timplalexis, C.; Salamanis, A.I.; Krinidis, S.; Ioannidis, D.; Kehagias, D.; Tzovaras, D. Energformer: A New Transformer Model for Energy Disaggregation. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2023, 69, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharatee, A.; Ray, P.K.; Ghosh, A. Hardware Design for Implementation of Energy Management in a Solar-Interfaced DC Microgrid. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2023, 69, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, P.K.; Pattnaik, M. Coordinated Power Management of a Laboratory Scale Wind Energy Assisted LVDC Microgrid With Hybrid Energy Storage System. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2023, 69, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, H. Online Digital Twin-Empowered Content Resale Mechanism in Age of Information-Aware Edge Caching Networks. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2025, 73, 4990–5004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Deng, K.; Zhang, H.; Zha, Z.; Jobaer, S. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Multi-Agent System with Advanced Actor–Critic Framework for Complex Environment. Mathematics 2025, 13, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Singh, B.; Mishra, S. Grid Interactive Solar PV and Battery Operated Air Conditioning System: Energy Management and Power Quality Improvement. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2023, 69, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becchi, L.; Belloni, E.; Bindi, M.; Intravaia, M.; Grasso, F.; Lozito, G.M.; Piccirilli, M.C. A computationally efficient rule-based scheduling algorithm for battery energy storage systems. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, H. Mobile Edge Computing Networks: Online Low-Latency and Fresh Service Provisioning. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2025, 73, 11463–11479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Hu, X.; Zhang, G.; Spachos, P.; Plataniotis, K.; Wu, H. Networking Systems of AI: On the Convergence of Computing and Communications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 20352–20381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrold, D.J.; Cao, J.; Fan, Z. Renewable energy integration and microgrid energy trading using multi-agent deep reinforcement learning. Appl. Energy 2022, 318, 119151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Oh, H.; Choi, J.K. Learning based cost optimal energy management model for campus microgrid systems. Appl. Energy 2022, 311, 118630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, R.; Esmaeilbeigi, R.; Charkhgard, H. The utilization of shared energy storage in energy systems: A comprehensive review. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 3163–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianvincenzi, M.; Marconi, M.; Mosconi, E.M.; Favi, C.; Tola, F. Systematic review of battery life cycle management: A framework for European regulation compliance. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, J.; Park, J. Demand-side management with shared energy storage system in smart grid. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2020, 11, 4466–4476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Hao, H.; Yang, D.; Yin, Z.; Zhou, B. Optimal Operation Strategy of Combined Heat and Power System Considering Demand Response and Household Thermal Inertia. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2023, 69, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Ma, D.; Wang, R.; Xie, X.; Zhang, H. Dynamic Event-Triggered-Based Integral Reinforcement Learning Algorithm for Frequency Control of Microgrid With Stochastic Uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2023, 69, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, A.; Zhou, M.; Wu, J.; Long, C. A comprehensive review on energy management, demand response, and coordination schemes utilization in multi-microgrids network. Appl. Energy 2022, 323, 119596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.; Singh, B. A Cost Effective High Power Factor General Purpose Battery Charger for Electric Two-Wheelers and Three Wheelers. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2023, 69, 1114–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmjoo, A.; Ghazanfari, A.; Østergaard, P.A.; Jahangiri, M.; Sumper, A.; Ahmadzadeh, S.; Eslamipoor, R. Moving toward the expansion of energy storage systems in renewable energy systems—A techno-institutional investigation with artificial intelligence consideration. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9926. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.; Saxena, V.; Singh, B.; Panigrahi, B.K. Power Quality Improved Grid-Interfaced PV-Assisted Onboard EV Charging Infrastructure for Smart Households Consumers. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2023, 69, 1091–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Shen, Z.; Wang, L. Online energy management for microgrids with CHP co-generation and energy storage. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2018, 28, 533–541. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Z.; Wu, C.; Wang, L.; Zhang, G. Real-time energy management for microgrid with EV station and CHP generation. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2021, 8, 1492–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Wang, X.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, F. Real-time optimal energy management of microgrid with uncertainties based on deep reinforcement learning. Energy 2022, 238, 121873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Oudalov, A.; Ulbig, A.; Andersson, G.; Kirschen, D.S. Modeling of lithium-ion battery degradation for cell life assessment. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2016, 9, 1131–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Xu, B.; Tan, Y.; Kirschen, D.; Zhang, B. Optimal battery control under cycle aging mechanisms in pay for performance settings. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2018, 64, 2324–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B. Dynamic valuation of battery lifetime. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 37, 2177–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Hong, S.H.; Ding, Y.; Ye, X. An incentive-based demand response (DR) model considering composited DR resources. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 66, 1488–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, M.; Wu, Z.; Liu, Y. Instance-Aware Visual Language Grounding for Consumer Robot Navigation. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2025; Early Access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.; Ding, Y.; Siano, P.; Song, Y. Optimal scheduling of the integrated electricity and natural gas systems considering the integrated demand response of energy hubs. IEEE Syst. J. 2020, 15, 4545–4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wan, Z.; He, H. Real-Time Residential Demand Response. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2020, 11, 4144–4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; He, H. Learning to Operate Distribution Networks With Safe Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 13, 1860–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Hong, S.H.; Yu, M. Demand response for home energy management using reinforcement learning and artificial neural network. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, 10, 6629–6639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Hong, S.H. Incentive-based demand response for smart grid with reinforcement learning and deep neural network. Appl. Energy 2019, 236, 937–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruelens, F.; Claessens, B.J.; Quaiyum, S.; De Schutter, B.; Babuška, R.; Belmans, R. Reinforcement learning applied to an electric water heater: From theory to practice. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2016, 9, 3792–3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruelens, F.; Claessens, B.J.; Vandael, S.; De Schutter, B.; Babuška, R.; Belmans, R. Residential demand response of thermostatically controlled loads using batch reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2016, 8, 2149–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.L.; Lou, J.L.; Tseng, M.L.; Lim, M.K.; Tan, R.R. A hybrid dynamic economic environmental dispatch model for balancing operating costs and pollutant emissions in renewable energy: A novel improved mayfly algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 203, 117411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Dong, M. Residential energy storage management with bidirectional energy control. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2018, 10, 3596–3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, A.; Sajjad, K.; Hafeez, G.; Murawwat, S.; Khan, S.; Khan, F.A. Real-time energy optimization and scheduling of buildings integrated with renewable microgrid. Appl. Energy 2023, 335, 120640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Feng, D.; Zhou, Y.; Hao, X.; Yi, Y.; Li, K. Impact of uncertainty on optimal battery operation for price arbitrage and peak shaving: From perspectives of analytical solutions and examples. J. Energy Storage 2023, 62, 106909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Le, B. Artificial ecosystem optimization for optimizing of position and operational power of battery energy storage system on the distribution network considering distributed generations. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 208, 118127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Hu, C.; Cheng, F. State of charge and state of energy estimation for lithium-ion batteries based on a long short-term memory neural network. J. Energy Storage 2021, 37, 102440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Xu, Y.; Deng, N.; Huang, X. Efficient degradation of organophosphorus pesticides and in situ phosphate recovery via NiFe-LDH activated peroxymonosulfate. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 524, 169107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Zhang, G. Two-Timescale Mobile User Association and Hybrid Generator On/Off Control for Green Cellular Networks With Energy Storage. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 11047–11059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, J.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, G. Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Trajectory Design for Customized UAV-Aided NOMA Data Collection. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2024, 13, 3365–3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Z.; Briso-Rodríguez, C.; Zhang, L. Experimental study on low-altitude UAV-to-ground propagation characteristics in campus environment. Comput. Netw. 2023, 237, 110055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, Z.; Wang, B.; Tang, X. Evaluate, explain, and explore the state more exactly: An improved Actor-Critic algorithm for complex environment. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 35, 12271–12282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Yu, Z.; Wang, Q.; Du, P.; Zhang, X. Prediction of SSE Shanghai Enterprises index based on bidirectional LSTM model of air pollutants. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 204, 117600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.M.; Ko, C.N. Short-term load forecasting using lifting scheme and ARIMA models. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 5902–5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Fan, X.; Zhao, Y.; Kang, K.; Yin, Q.; Zeng, J. Q-learning based dynamic task scheduling for energy-efficient cloud computing. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 108, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Shen, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, G. Intelligent energy scheduling in renewable integrated microgrid with bidirectional electricity-to-hydrogen conversion. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2022, 9, 2212–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Pota, H.R.; Squartini, S.; Abdou, A.F. Modified PSO algorithm for real-time energy management in grid-connected microgrids. Renew. Energy 2019, 136, 746–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).