Abstract

This paper is intended to present—in light of the authors’ own research—the inhabitants of Polish municipalities’ perceptions of the environmental determinants affecting the quality of life, with particular emphasis on the environmental assessment of their place of residence, the changes that have taken place in this area over the last five years as well as the key environmental hazards impacting on the quality of life, and sustainable development. The research method consisted of the following steps: (i) review of the literature, (ii) preparation of a questionnaire on the perception of the quality of the environment and environmental threats, (iii) conducting questionnaire interviews using the CAWI technique among adult residents of Poland in the period July–September 2023, (iv) statistical analysis of the results obtained. The findings of the nationwide survey indicate that respondents ranked air quality problems among the most significant environmental problems. The analysis of these surveys shows that respondents’ awareness of the most harmful factors degrading the environment varied by area. The study contributes to the development of research on the perception of environmental threats and public environmental awareness, filling a gap related to the insufficient consideration of the spatial and temporal aspects of this phenomenon in the existing Polish literature. The research results presented in the article may be useful in diagnosing the environmental determinants of quality of life. They also provide guidance for decision-makers, spatial planners, environmental protection institutions, social organisations, and educational institutions on which directions of action in the field of environmental protection and sustainable development should be implemented in a given area.

1. Introduction

Sustainable development as a socio-economic strategy was primarily introduced in order to create the conditions for humans to function in a healthy and high-quality natural environment over the long term [1,2,3,4]. In this context, important issues are problems related to ensuring a proper quality of life [5,6,7,8,9,10]. In recent years, the relationship between quality of life and the environment has become an emerging topic of scientific, social and political discussion. Numerous publications on this subject have been produced in academic circles (see, e.g., Refs. [11,12,13,14,15,16,17]). Moreover, organisations such as the United Nations and its specialised agencies, the European Union together with the European Environment Agency and Eurostat have made a significant contribution to progress in thinking about the environmental determinants of quality of life. Sustainable development policies should also be able to identify and minimise environmental risks, taking into account existing social needs and preferences and ensuring an adequate quality of life for citizens.

Previous studies on quality of life in Poland have focused mainly on economic, socio-psychological, or health aspects, marginalising environmental conditions. There is therefore a research gap concerning the perception of the impact of factors related to the state of the environment by the inhabitants themselves, especially at the local level, taking into account spatial differences and changes over time. This gap justifies the need for research on the social perception of the state of the environment and its changes, as well as the identification of environmental threats to quality of life. Even the few scientific articles referring to the environmental aspects of quality of life in the Polish economy [18] are based on objective data. The literature on the subject, however, points to the growing importance of the environmental factor in the subjective assessment of quality of life [19,20]. Research on the subjective assessment of environmental threats has already been conducted by the authors of the following study, but it mainly concerned the Śląskie voivodeship (one of the administrative regions in southern Poland). The results of this research indicated that awareness of environmental threats in Poland is relatively high, but often limited to a declarative level. The key challenge remains translating knowledge into practical pro-environmental actions [15,21,22].

At the same time, public opinion polls on the environmental awareness of Poles were conducted in Poland [23,24]. The first studies devoted to social issues of environmental protection, environmental awareness, and attitudes towards the natural environment were conducted in Poland in the 1980s. The results of these studies indicate that the level of environmental awareness among various social groups was insufficient [21]. The results of subsequent studies conducted by the Institute for Sustainable Development [25,26,27] and CBOS [23,28] show that the level of concern about the state of the environment was highest in the 1990s and began to decline significantly from 1999. Other studies assessing the state of environmental awareness among the Polish public include tracking studies commissioned by the Ministry of Climate and Environment and ongoing since 2011. The latest edition shows that Poles are increasingly aware of environmental problems and declare pro-ecological actions, although practice does not always go hand in hand with declarations [29].

The above studies justify the following research hypothesis: the inhabitants of Poland assess well the state and changes taking place in the natural environment, but at the same time are aware of the existence of environmental threats with negative consequences for the quality of life. Thus, the basic questions that the authors wish to find an answer to on the basis of the analysis of the surveys are:

- RQ1: How do the inhabitants of Poland assess the state of the environment and the changes that have taken place in the environment in the last 5 years?

- RQ2: Which environmental threats are the most important in the view of Polish citizens?

In this study, the term “natural environment” refers to the physical surroundings and ecological systems that have not been created by humans, including air, water, soil, flora, fauna, and landscapes. This concept encompasses key natural resources and conditions that directly affect human health, well-being, and quality of life [30,31].

Also, it should be pointed out that quality of life is an extremely difficult category to measure, as it is related to an individual’s feelings and degree of satisfaction [32,33,34]. The most precise method of measurement remains, in this aspect, to address the subject individually, hence, for the purposes of the following paper, the basic research tool chosen is individual questionnaire surveys. The survey was conducted using the Computer Assisted Web Interviewing (CAWI) method in 2023 among 858 adult residents of Poland.

2. Literature Review

As raised in the subject literature [35,36,37,38,39,40,41], quality of life (QOL) is a multidisciplinary research category, which has become the subject of study within such diverse scientific disciplines as economics, management science, sociology, political science, psychology, medicine or geography. Consequently, the concept has not received a single, universal and widely used definition, rather many approaches and research operationalisations. This is due both to the differences in the approach of these scientific disciplines to the empirical analysis of quality of life and to the nature of quality of life itself, which is a multidimensional phenomenon and hard to unambiguously capture; entangled in cultural and ideological contexts [39,42].

An attempt to systematise definitions of quality of life in the Polish scientific literature was made by J. Trzebiatowski, distinguishing: (1) existential definitions, in which the key issue is answering the question “What kind of man to be?”; (2) definitions related to subjective self-realisation, in which quality of life consists of creative fulfilment; (3) definitions emphasising the necessity of satisfying the needs that a person considers the most important in his/her life. In this approach, quality of life is understood as the level of satisfaction with the fulfilment of needs within the pursued way of life; (4) definitions including objective and subjective determinants of quality of life, as well as an assessment of the satisfaction of individual needs [43].

The beginning of scientific interest in the quality of life is connected with the American research of 1971, conducted under the direction of A. Campbell at the Institute of Social Research at the University of Michigan, whose aim was to determine the degree of satisfaction of respondents with individual spheres of life, expressed in reflective assessments of such spheres as: marriage, family, health, education, professional work, earnings, leisure time, place of residence, standard of living, or savings [44]. In Poland, the first studies on quality of life were conducted in the mid-1970s by the Public Opinion Research Centre, the Institute of Philosophy and Sociology of the Polish Academy of Sciences and the Institute of Sociology of the University of Warsaw, yet the results of these studies have not been widely reported [45]. Further theoretical and methodological work on quality of life was carried out at the Department of Social and Economic Research of the Central Statistical Office (Statistics Poland) and the Polish Academy of Sciences. Regular research on quality of life has been conducted in Poland since the early 1990s. They were initiated in the years 1991–1997 within the framework of projects of the State Committee for Scientific Research (KBN)—the Polish General Survey of the Quality of Life. From 2000 onwards, the survey of the conditions and quality of life of Poles was conducted by the Council for Social Monitoring, while the Social Diagnosis reports [46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53] prepared by a team led by Professor Janusz Czapiński constituted the most representative study of both objective and subjective quality of life of Poles. Unfortunately, they did not take into account the environmental determinants of quality of life at all [54].

Nowadays, the following trends of research interest can be distinguished in quality of life studies [55]: (1) the trend focusing on the economic aspects of life (quality of life is understood here as the standard of living of an individual, family, local community, region, country. The level of wealth and poverty, as well as their unequal distribution, are of major importance for the quality of life of the individual and society); (2) the stream based on socio-psychological motives (focuses on the negative consequences of civilisation development for individuals and social life); (3) the stream related to the measurement of health (characteristic of medical science; health-related quality of life, understood as the patient’s self-assessment of the impact of the disease and the treatment applied on his or her physical, psychological and social functioning); (4) the trend relating to problems of urbanisation (focuses attention on the particularly adverse effects of scientific and technological development in urbanised areas, such as: defective urban planning, housing, high density of agglomerations, excessive use of car transport); (5) the stream focusing on the quality and protection of the environment (points out the consequences of the progress of civilisation on the natural environment and on human health and quality of life, as a result of, inter alia, air and water pollution, excessive noise, etc.). It should be emphasised that within each of the aforementioned research approaches, the significance of quality of life is now widely recognised in the context of implementing the paradigm of sustainable development (see, e.g., Refs. [14,15,56,57,58,59,60]).

At the same time, it should be emphasised that in all the above-mentioned research trends both a comparative (valuing) and descriptive (non-valuing) orientation is present. It should also be added that, of the research streams indicated, the environmental stream has, until recently, enjoyed relatively limited research interest. We have only observed an increase in interest in the indicated matter in recent years.

A different, multi-faceted approach to measuring quality of life has been adopted and implemented within the framework of Eurostat statistics, which draws on the concept proposed by the German sociologist Wolfgang Zapf, combining the Scandinavian approach to measuring quality of life—which focuses on objective living conditions—and the American approach—which identifies quality of life with subjective well-being. Thus, within the broad framework of living conditions, the following eight domains (thematic areas) are taken into account in Eurostat surveys: material living conditions, health, education, economic activity, leisure time and social relations, economic and physical security, quality of the state and fundamental rights, infrastructure and the environment. In turn, the measurement of subjective well-being (referred to as the 9th domain) includes an overall assessment of quality of life/overall experience of life [34,61].

The concept of measuring quality of life adopted by the Polish Central Statistical Office (GUS) refers both to the above-mentioned tradition of Polish research on this issue and to international recommendations, including Eurostat. Accordingly, the concept of quality of life measurement adopted by the Central Statistical Office takes into account the nine domains (thematic groups) indicated above, but the scope of information collected by the GUS goes significantly beyond the scope of obligatory data at the European Union level, which includes subjective assessments of quality of life [62]. Quality of life is described by the GUS on the basis of the following number of measures adopted for individual domains: material situation—14 measures; work—9 measures; health—7 measures; education—7 measures; leisure time and social relations—6 measures; personal security (economic and physical)—3 measures; quality of the state and basic rights—8 measures; quality of the environment in the place of residence—3 measures, and so-called subjective well-being—5 measures [63,64].

We should add that the measures in the area of “quality of the natural environment at the place of residence” are: exposure to excessive noise, exposure to pollution or other environmental problems, satisfaction with recreational areas and green spaces.

As indicated above, recent years have seen an increased interest concerning the issue of quality of life and its determinants, and its relevance to the implementation of the socio-economic sustainable development paradigm by both international organisations and governments, as well as by researchers representing various scientific disciplines. The indicated increase in interest in the subject matter results from new challenges related to socio-economic changes taking place in the world, including demographic processes (changes in the age structure of the population, migration), globalisation processes, the aspiration of an increasing number of people to improve the quality of life, the growing awareness of societies and governments about the possibility of improving their current living conditions. The need to monitor the implementation process of the socio-economic sustainability paradigm is also relevant here.

Concurrently, the literature emphasises that the social, economic, and environmental goals of sustainable development are closely linked to human existential security, which is a basic condition for a high quality of life (see, e.g., Refs. [65,66,67,68,69,70]). When analysing this subject matter, it can be observed that the following feedback loop occurs: existential security promotes quality of life, and high quality of life increases support for and the ability to implement sustainable development strategies (research by R. Inglehart and Ch. Welzel have already shown that societies with higher existential security are more inclined towards pro-environmental attitudes and investment in long-term development strategies—[71]), while sustainable development is a mechanism that strengthens existential security and quality of life. UNDP reports emphasise that the concept of human security, related to the idea of existential security, is inextricably linked to both well-being and sustainable development [72,73] (see also Ref. [74]).

Research on the quality of life is carried out within the framework of various scientific disciplines already indicated above, including the disciplines of economics and finance, as well as management and quality sciences. It should be emphasised, however, that they mainly represent the trend focusing on the economic aspect of the quality of life, where quality of life is perceived as the standard of living of an individual, local community/region/country, whereby traditional measures of wealth are considered here together with the subjective assessment of deprivation, e.g., Refs. [24,39,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,75,76,77,78]), and the trend referring to the impact of social infrastructure and social services on the quality of life of the inhabitants of a given area [56,58,59,79,80,81,82,83].

The issue of environmental determinants of quality of life has so far not been the subject of broader interest among Polish researchers, although it should be noted that some of them have recognised its importance in their publications [54,84]. One of the few studies dedicated to the issue of environmental determinants of quality of life was carried out by Iwona Bąk, who in her article “Regional diversity of the environmental quality of life in Poland” [18], presented an assessment of the diversity of the quality of life in Polish provinces (voivodeships) in 2021 in the context of environmental determinants, using indicators monitoring the links between the environment and society and its quality of life in her analysis.

For over fifty years, research has been conducted in Poland on citizens’ environmental awareness and their attitudes towards the natural environment (see [21] for more details). Nationwide research on this subject has been conducted since the early 1990s by the Public Opinion Research Center in Warsaw (CBOS), with the most recent study carried out in 2020 [23]. This analysis supports the claim that the environmental awareness of Poles is steadily growing, but it is often negative in nature—it is expressed as opposition to real and potential environmental threats, but rarely translates into personal pro-environmental behaviour and positive actions. Similar results were obtained by A. Lorek, who studied the role of ecosystem services in the sustainable development of municipalities in a highly urbanised region [15]. It should be emphasised, however, that in all these studies, respondents recognised the importance of nature for quality of life. It should be added that surveys on the quality of the natural environment at the local level are also conducted by the Polish Central Statistical Office (GUS) as part of the Social Cohesion Survey. The results of the latest of these surveys were published in 2020 [24].

This article can be treated as a supplement to the previously discussed research, as it presents the results of a survey conducted among the inhabitants of Polish municipalities on their perception of the importance of environmental determinants of the quality of life, with particular emphasis on the assessment of the state of the natural environment in their place of residence, the changes that have taken place in this area over the past 5 years and the core environmental threats to the quality of life.

3. Materials and Methods

The research procedure adopted covered the following three stages:

Stage I. A systematic review of the literature on the subject and available research relating to the problem of quality of life and the importance of environmental factors for it. Environmental quality generally plays a key role in quality of life, and sustainable development. It directly affects people’s health and safety, as well as the attractiveness of a place to live.

Stage II. Selection of the survey instrument and preparation of the questionnaire.

Measures of a qualitative nature have a central role in quality of life research, so the main sources of information are individual surveys and, to a lesser extent, group opinion polls. In the research conducted, a survey questionnaire was chosen as the research tool. The following survey questions are analysed in this article:

- How do you assess the state of the natural environment in your municipality (answers: very good, rather good, rather bad, bad, hard to say)?

- How do you assess the changes in the natural environment in your municipality over the last 5 years (answers: very favourable, rather favourable, nothing has changed, rather unfavourable, very unfavourable)?

- A multi-item question on choosing the 5 factors you consider to be the most dangerous in the area where you live from a list of different environmental impacts. The list included the following items: air pollution from industrial plants, air pollution from residential chimneys, air pollution from car exhaust fumes, pollution of surface and groundwater (rivers, lakes) by municipal sewage, pollution of surface and groundwater (rivers, lakes) by industrial sewage, industrial waste, municipal waste landfills, illegal dumps, noise, mining damage, poor water quality, soil pollution and degradation, excessive tree felling and destruction of green areas, dirt and disorder on streets and in residential areas, difficult to say, and others—option to enter custom answer.

Stage III. Conducting the survey. The research was conducted using a survey method through a specialised on-line survey creator Ankieteo. Ankieteo is integrated with the largest Polish online panel (called Swpanel), i.e., Polish residents who have agreed to participate in surveys (as of January 2023, this is over 313,000 people). Every year, Swpanel undergoes an audit by the most important Polish organisation associating research companies—OFBOR (Organization of Opinion and Market Research Companies). Since 2015, it has held a certificate of quality for online research (CAWI), which guarantees the highest possible quality of research projects. Swpanel has maintained an appropriate demographic structure of the panel so that it is as close as possible to the image of Polish society.

The minimum sample size was calculated according to Formula (1). This formula illustrates the relation between sample size n and error margin e, level of confidence z, sample proportion p and population size N [85]. The confidence level used is z = 0.95 and the margin of error is e = 5% for the adult Polish population.

In 2023, the population of Poland aged 18 and over was approximately 30 million. According to data from the Central Statistical Office [86], the total population of Poland at the end of 2022 was 37,766,000. The number of people aged 18+ accounted for 81.6% of the total population. This means that the number of adult Poles in 2022 was N = 30,817,056, which was the basis for calculating the minimum sample size of 385 people. The number of participants in the study was greater than the previously calculated minimum sample size.

The survey was aimed at people using the Internet, who independently completed an electronic questionnaire via a survey link that they received. The links were posted on the on-line survey platform Swpanel. The survey was anonymous and targeted adults. The data collected did not contain any characteristics that could identify the respondents. The survey was conducted between July and September 2023 and complied with ethical standards, including the ICC/ESOMAR International Code [87]. The process of conducting the survey is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The process of conducting the survey.

The research conducted in 2023 was preceded by earlier editions of the study in the Śląskie voivodeship. As a result, after verification and rejection of incomplete responses, 858 completed questionnaires were obtained. Table 1 contains the characteristics of the research sample.

Table 1.

Characteristics of survey respondents.

For comparative purposes, the results of studies carried out in the Śląskie voivodeship over the years were also used: 1999/2000; 2012/14 and 2017/18 [15].

Stage IV. Data analysis. Based on the data collected through the questionnaire, a database was created, which was used to interpret the data and create a perception map of the most significant environmental risks as perceived by the respondents. Analysis approach contained descriptive and spatial statistics.

4. Results

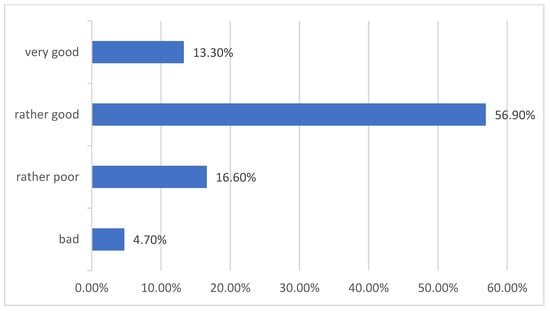

The following subsection concerns the identification of the main environmental determinants of quality of life in the opinion of Polish residents. The first questions analysed concerned the general assessment of the state of the environment in the respondent’s municipality of residence and the changes that have taken place in this environment over the past 5 years. Detailed results are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Assessment of the state of the natural environment in the municipality of the respondent’s residence on a nationwide basis in 2023.

The results indicate that residents’ opinions on the state of the natural environment in their municipalities are mostly positive. As many as 56.9% of respondents rate the state of the environment as rather good, and an additional 13.3% as very good, which together gives over 70% of positive responses. This shows that the vast majority of residents are satisfied with the environmental conditions in their place of residence.

Negative assessments are relatively rare—only 16.6% of respondents indicated that the state of the environment is rather poor, and 4.7% described it as poor. In total, critical opinions account for 21.3%, which suggests that environmental problems are recognised but do not dominate on a national scale. However, the proportion of these responses may indicate the existence of local areas with poorer environmental quality, which requires further in-depth analysis.

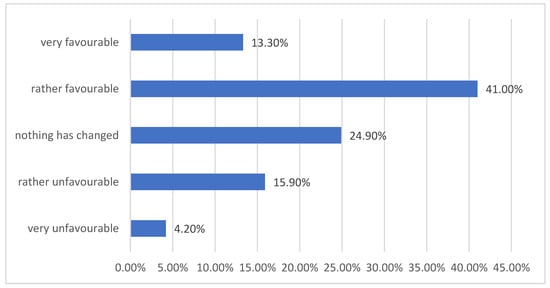

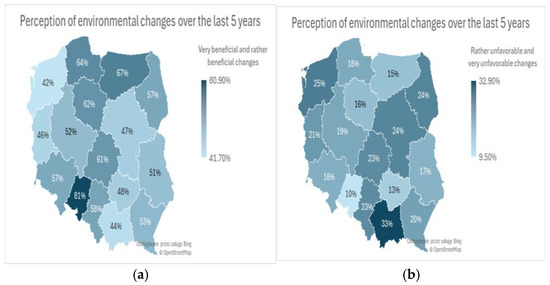

The next question concerns changes that have taken place in the environment over the last 5 years (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Assessment of changes that have occurred in the environment in the respondent’s municipality of residence in the last 5 years on a nationwide basis in 2023.

An analysis of residents’ opinions on environmental changes in their municipalities over the past five years reveals a moderately optimistic picture. The largest group of respondents (41%) assess these changes as rather beneficial, and an additional 13.3% as very beneficial. In total, this means that more than half of the respondents (54.3%) perceive an improvement in the quality of the environment in their immediate surroundings.

At the same time, a significant proportion of respondents (24.9%) declare that, in their opinion, no significant changes have taken place in the environment. This response may suggest stability in environmental conditions, but also a lack of awareness or limited observation of the processes taking place in the environment.

Negative assessments are in the minority—15.9% of respondents describe the changes as rather unfavourable, and only 4.2% as very unfavourable. The total share of critical assessments (20.1%) indicates that, despite the prevailing positive trend, some municipalities have environmental problems that are noticed by residents but are not captured in this article due to the level of analysis (the level of entire provinces).

An analysis of the relationship between the answers to the above questions and the respondents’ profile showed that there is no correlation with regard to gender for both questions and age when answering the question on the state of the environment. When assessing the changes that have taken place in the environment, those aged 26–39 are the most positive. People aged 40–65 have a different perception—less than 50% of respondents in this group rated the changes as positive.

In other cases, the following regularities can be distinguished:

- Education. The assessment of the state of the environment in terms of education is similar outside the group with lower secondary education (this group is dominated by a bad or rather bad assessment of the state of the environment—53.3% of responses). In turn, changes in the environment in the last 5 years were best assessed by people with a master’s degree (57.2% of responses). The highest number of responses assessing the changes negatively was again recorded in the group with lower secondary education (26.7%).

- Occupation. The best assessment of the state of the environment was made in the group of white-collar workers and officials (75.7% of responses assessing the state of the environment very well and rather well). The highest number of responses assessing the negative state of the environment was recorded in the professional group of teachers (39.1%). Evaluations of environmental change are even more varied (the range of positive evaluations ranges from 49 to 81%). The best rated changes in the environment were in the group of trade and service employees (81.5% rating the changes positively). The highest number of responses assessing changes negatively concerned managers (26.7% of responses).

- Occupational status. The state of the environment was rated best by housewives (88.9% of answers rating the state of the environment as very good and rather good and 8.3% rating it bad and rather bad). The fewest responses assessing the state of the environment well were given by farmers (46.7% assessing the state of the environment very well or rather well and 26.7% assessing it badly or rather badly). A similar distribution applies to the assessment of the changes that have taken place in the environment in the last 5 years (61.1% of housewives assess the changes positively compared to 33.3% of positive assessments in the group of farmers).

- Type of apartment, place of residence. The state of the environment is assessed more positively by residents of single-family houses (75.5% of very good and rather good ratings) and villages (76.4% of positive ratings). A similar regularity applies to the assessment of changes in the environment.

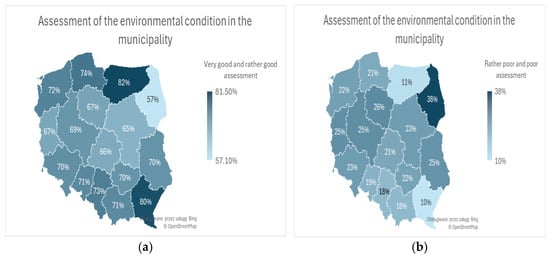

- Province. Significant differences can also be observed in spatial terms. The best assessment of the state of the environment was made by the inhabitants of the following voivodeships/provinces: Warmińsko-Mazurskie and Podkarpackie, the most answers assessing the state of the environment as bad or rather bad were given in the Podlaskie voivodeship (these data are illustrated in Figure 4a,b). Most respondents positively assessed the changes in the environment in the Opolskie voivodeship, and the highest percentage of negative assessments concerned the Małopolskie voivodeship (see Figure 5a,b).

Figure 4. Assessment of the environmental condition in the municipality. (a) Very good and rather good assessment; (b) poor and rather poor assessment.

Figure 4. Assessment of the environmental condition in the municipality. (a) Very good and rather good assessment; (b) poor and rather poor assessment. Figure 5. Perception of environmental changes over the last 5 years. (a) Very beneficial and rather beneficial changes (b) rather unfavourable and very unfavourable changes.

Figure 5. Perception of environmental changes over the last 5 years. (a) Very beneficial and rather beneficial changes (b) rather unfavourable and very unfavourable changes.

The next question focused on the perception of different types of environmental hazards occurring in the municipality of the respondent’s residence. Respondents considered air pollution from cars to be the most important threat, followed by air pollution from low emissions from houses and illegal rubbish dumps. Based on the results obtained, a ranking of the most important environmental threats in the opinion of Polish residents was prepared, as presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Ranking of the most important ecological threats in the opinion of the inhabitants of Poland in 2023.

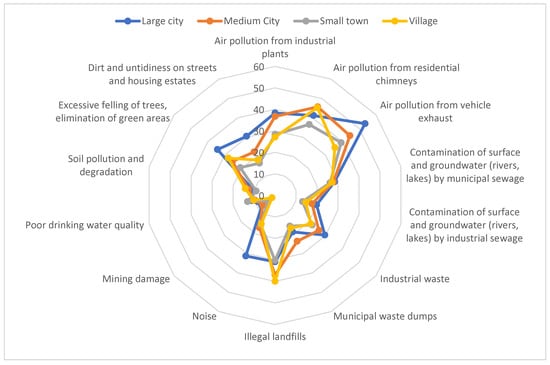

The next step of the analysis was to prepare a ranking of environmental hazards in terms of living in: a large city (100,000 inhabitants and more), a medium-sized city (20,000–100,000 inhabitants), a small city (less than 20,000 inhabitants) and a village, as illustrated in Figure 6. The results indicate a high ranking of air pollution (both low emissions and vehicle exhaust) as the most relevant environmental issue for respondents.

Figure 6.

Perception of environmental threats by place of residence divided into large, medium and small cities and villages for Poland in 2023.

Based on the ranking presented in Figure 6 in terms of the size of settlement units, the following conclusions can be formulated:

- In medium and small cities and among rural residents, there is a stronger sense of the problem related to illegal landfills (medium and small cities: place 3, village: place 2),

- Noise occupies a high 5th place in the ranking of threats to residents of large cities,

- Excessive felling of trees and liquidation of green areas occupies the highest positions in the ranking for residents of large cities and villages.

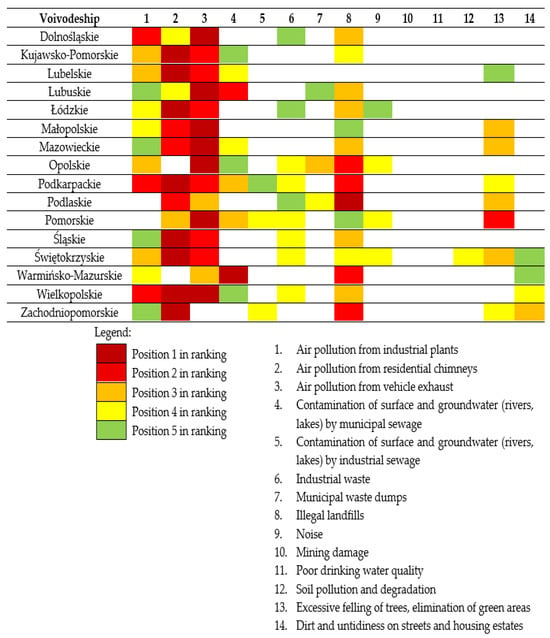

The next stage was the analysis of the perception of reported environmental threats in the spatial layout for the nationwide sample in the voivodeship/province approach, which is presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Map of perception of the 5 most important environmental threats in the spatial layout by voivodeship in 2023.

An analysis of perceptions of environmental threats across voivodeships indicates a clear predominance of issues related to air quality. In almost all regions, air pollution is ranked first, with differences in emission sources. The most frequently mentioned threats are car exhaust fumes and emissions from residential chimneys, reflecting both the problem of low emissions and heavy traffic, especially in urban areas. In several voivodeships (including Dolnośląskie, Lubuskie, Małopolskie, Mazowieckie, Opolskie, Pomorskie, and Wielkopolskie), car exhaust fumes are at the top of the ranking, while in some regions with a higher proportion of scattered development and individual home heating (Kujawsko-Pomorskie, Lubelskie, Podkarpackie, Świętokrzyskie, Wielkopolskie, and Zachodniopomorskie) or with a high population density and traditions related to industrial development (Łódzkie and Śląskie), emissions from domestic heating systems are the most serious problem.

The second significant set of problems in residents’ perceptions are threats related to waste management. Illegal dumps appear in the top five environmental threats in almost all voivodeships, often occupying high positions (including 1st place—Podlaskie; 2nd place—Opolskie, Podkarpackie, Warmińsko-Mazurskie, Zachodniopomorskie; 3rd place—Dolnośląskie, Lubuskie, Łódzkie, Mazowieckie, Śląśkie, Wielkopolskie). This confirms that the problem of illegal waste disposal remains widespread regardless of the region. In some voivodeships, residents also point to problems related to legal municipal and industrial waste landfills, which indicates a growing sensitivity to waste management issues, as well as possible threats and nuisances (e.g., odour emissions, space occupation) associated with their storage.

In some provinces, problems related to surface and groundwater pollution are also among the key threats. This applies in particular to the Warmińsko-Mazurskie (ranked first in terms of threats related to municipal sewage pollution), Lubuskie, Pomorskie, and Podkarpackie voivodeships, i.e., areas with significant water resources and high anthropogenic pressure. Residents point to both municipal and industrial pollution, confirming the multifaceted nature of the problem.

Threats related to the degradation of green areas and deforestation, such as excessive tree felling, rank high in several provinces, especially Pomorskie, Mazowieckie, Małopolskie, Podlaskie, and Świętokrzyskie. This reflects the growing importance of green areas in the perception of environmental quality and the concern of residents about the loss of biodiversity and recreational spaces.

On the other hand, threats such as mining damage, poor drinking water quality, and soil degradation are relatively rare in the top five, which may stem from their lower prevalence or local nature. These phenomena, although significant in certain regions (e.g., mining damage in the Śląskie voivodeship), are not a dominant problem on a national scale.

5. Discussion

Summarising the results of the research nationwide, one can see that respondents ranked air quality problems among the most significant environmental problems, i.e., air pollution from car exhausts, air pollution from residential chimneys and air pollution from industrial plants. The conducted questionnaire surveys also made it possible to assess environmental awareness in spatial terms among people living in individual provinces and depending on the size of the town or village they live in. The analysis of these surveys shows that respondents’ awareness of the most harmful factors degrading the environment varied by area. The most frequently selected environmental hazards (ranked 1) were air pollution from residential chimneys and air pollution from car exhausts.

Such pollutants are classified as factors that have the greatest impact on human health and, consequently, on quality of life. A significant problem related to air quality in Poland is the exceeding of standards for particulate matter, especially in winter, which affects the comfort of life for people living in the city centres of large cities and agglomerations. Poland emits almost five times more PM10 and PM2.5 particulate matter and more than twice as much NO2 as the EU average. Municipal and residential emissions account for the largest share of PM10 and PM2.5 particulate matter and benzo(a)pyrene emissions in Poland. On the other hand, emissions from transport are the main source of NOx. Data published by the Chief Inspectorate for Environmental Protection (GIOŚ) indicate that over the last decade, Poland has seen a significant reduction in human exposure to long-term high concentrations of particulate matter [88]. In 2022, PM10 emissions amounted to 353,700 tons, which was lower than in both the previous year and 2000, by 11.0% and 15.7%, respectively. In the case of PM2.5 dust, emissions amounted to 262,300 tons, a decrease of 12.0% compared to 2021 and 11.0% compared to 2000. Per capita, 9.4 kg of PM10 dust was emitted in 2022, including 6.9 kg of PM2.5 dust, which were the lowest values recorded since 2000. In European Union countries, based on data from the European Monitoring Program for Air Pollution (EMEP), this indicator was 4.4 kg for PM10 and 2.9 kg for PM2.5 in 2022. The highest emissions of PM10, including PM2.5, per capita were recorded in Latvia (14.0 kg and 9.1 kg, respectively) and Poland (9.6 kg and 7.1 kg), while the lowest were in the Netherlands (1.5 kg and 0.8 kg), Germany (2.2 kg and 1.0 kg), and Cyprus (2.2 kg and 1.1 kg) [89]. Despite a significant improvement in air quality resulting from measures taken over the period 2010–2021, the problem of meeting the standards for PM10 and PM2.5 particulate matter is chiefly prevalent in cities and, at the provincial level, in the Śląskie and Małopolskie voivodeships [88].

There is therefore a discrepancy between residents’ strong perception of low emission problems and actual trends in air quality improvement. This suggests that subjective assessments may: react with a delay, be linked to established experiences from previous years, relate to seasonal episodes, or be linked to a limited area (e.g., city centres). These conclusions are confirmed by a study by Klima et al. [90], which found a significant discrepancy between the objective assessment of air pollution and residents’ perceptions. The authors note that the perception of air quality is partly shaped by factors such as smell. In this study, pollution was more often associated with smog related to car traffic or individual home heating than with odourless emissions from combined heat and power plants.

Despite the predominance of air pollution hazards in the spatial analysis, two exceptions are noticeable. The first example of an area with a different ranking is Warmińsko-Mazurskie voivodeship (Situated in north-eastern Poland, this voivodeship is characterised by extensive forested areas and numerous lakes, and plays an important role in the country’s tourism sector), where the first two positions were occupied by neither air pollution from residential chimneys nor air pollution from car exhausts, but surface and underground water pollution (rivers, lakes) from municipal sewage and second place by illegal dumps. These threats can be linked to the characteristics of the voivodeship and its high tourism potential associated with the recreational use of lakes and the development of buildings around them. The second example is the Podlaskie voivodeship (A voivodeship located in the north-eastern part of the country, rich in forested areas—including the Polish section of the Białowieża Forest—and playing a significant role in tourism), where illegal rubbish dumps were identified as the most significant environmental concern. This is a voivodeship with above-average natural values, a high degree of forest cover and scattered development, which causes problems with illegal waste disposal.

Also, an important priority in the national ranking was excessive tree felling and liquidation of green areas. This problem was given a high priority in the Pomorskie voivodeship (This northern Polish region, with its coastal location along the Baltic Sea, holds strategic significance for maritime and economic activities) (2nd place in the ranking), which can be associated with the felling of forests carried out by the “State Forests” National Forest Holding (Państwowe Gospodarstwo Leśne Lasy Państwowe) and by other persons. These cuttings affected areas (e.g., overgrown allotments, river banks, street trees) and forests with important social functions and aroused numerous protests [91,92,93,94,95].

For comparative purposes, previous editions of research conducted in the Śląskie voivodeship (Situated in the southern part of Poland, the region is marked by intensive urban and industrial growth) were used to show changes in the perception of threats in temporal terms. The ranking of the most important ecological threats in the place of residence in the opinion of respondents in the years 1999–2023 for the Śląskie voivodeship is presented in Table 3. In the editions 1999/2000 and 2012/14 the choice was limited to 3 factors, in the edition 2017/18 and in 2023 the possibility of choice was extended to 5 factors).

Table 3.

Ranking of the greatest environmental threats in the place of residence in the opinion of respondents in 1999–2023 for the Śląskie voivodeship (selected groups of threats are marked with the following colours: blue—air pollution from industrial plants; red—air pollution from residential chimneys; yellow—air pollution from vehicle exhaust; orange—illegal landfills; green—excessive felling of trees, elimination of green areas; dark purple—mining damage).

Based on the analysis, it is possible to identify some regularities regarding the perception of environmental threats by the inhabitants of the Śląskie voivodeship:

- The main environmental problems of the voivodeship, similarly to the nationwide sample, concern pollutants emitted into the air.

- The first three places in the last rankings conducted in 2017–2017 and 2023 have not changed and concern: air pollution by chimneys of residential houses, air pollution by car exhaust gases and illegal rubbish dumps.

- In the studies conducted in 1999–2000, the first hazard ranking was occupied by air pollution from industrial plants. This changed in the 2012–2014 surveys and since then the first place in the ranking of hazards has been taken by low emissions from residential houses.

- There is a systematic decrease in the perception of threat by mining damage (rankings 1999–2000 and 2012–2014: 3rd place, ranking 2017–2018: 5th place, ranking 2023: 8th place, which is related to the process of restructuring the mining industry and the gradual cessation of mine operations.

The presented research results concerning the perception of Polish respondents (with particular emphasis on the inhabitants of the Śląskie voivodeship) of the impact of environmental conditions on the quality of life and on sustainable social and economic development correspond to the results of nationwide diagnostic surveys on environmental awareness and perception of environmental problems [23,29]. In all of these studies, the majority of Poles assess the state of the environment positively, and air pollution was identified as the most important environmental threat in Poland. The presented research also corresponds to similar scientific studies conducted both for all European Union member states and in 24 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (see Refs. [96,97]). In the case of the scientific studies mentioned, it is noteworthy that respondents recognise the importance of the quality of the natural environment in their place of residence for their quality of life, and that they identify the reduction in the area of forests and other green spaces (especially in cities) and high levels of air pollution as some of the main environmental problems affecting the health of the population, quality of life, and the implementation of the sustainable development paradigm. Similar results were also obtained in studies conducted for regions of the Czech Republic (see Ref. [98]). The results of these studies also show that although environmental awareness in the countries where they were conducted is systematically increasing, its level varies from region to region.

6. Conclusions

The concept of quality of life is embedded centrally in the concept of sustainable development. Quality of life refers to the satisfaction of both tangible and intangible needs, which may be individual or collective. The quality of life is determined by objective and subjective factors resulting from individual reception and the degree of satisfaction, including the perception of factors and threats related to the state of the environment. In their entirety, these factors compose the complex aspects of human existence. Non-consumer, or non-material needs related to, among other things, the state of the natural environment have a direct impact on people’s health and safety, as well as on the attractiveness of the place of residence. The results of surveys of Polish citizens presented in the paper show that environmental quality issues are present in the consciousness of respondents. Most respondents positively assess the state of the environment and the changes that have occurred within it over the past five years. At the same time, respondents’ assessments indicate the most significant threats related to air pollution. Other threats that appear as important in the opinion of respondents are: illegal waste dumps and excessive felling of trees or liquidation of green areas. Thus, the research hypothesis was positively confirmed, and answers to the research questions were obtained. The study contributes to the development of research on the perception of environmental threats and public environmental awareness, filling a gap related to the insufficient consideration of the spatial and temporal aspects of this phenomenon in the existing Polish literature.

The study has several limitations that should be taken into account when interpreting the results. First, the analysis concerns perceptions rather than objective environmental indicators, which may cause discrepancies between the perceived and actual quality of the environment. Second, the research method used (declarative survey) is prone to subjectivity. The limitations also apply to the technique used to conduct the survey, i.e., an online interview, which is easier for the researcher to carry out but raises problems related to the lack of access to digitally excluded people. Thirdly, although the results are representative at the national and provincial levels, they do not take into account differences within individual regions.

The results of the study have significant practical implications—they indicate that environmental policies should be differentiated regionally, taking into account local perceptions and the specific nature of threats. The results obtained may be useful for public and local government decision-makers, spatial planners, environmental protection institutions, social organisations, and educational institutions. These findings can serve as a tool to support the process of public policy-making and strategic planning, particularly in the context of implementing local sustainable development strategies, air protection programmes, and spatial development policies. The identified spatial differences in the perception of threats indicate the need for a differentiated approach to environmental education and remedial measures in individual voivodeships.

Such surveys can be useful for politicians, pointing out unmet social needs and giving clues as to what the priorities of implemented policies should be in order to guarantee the highest possible quality of life for residents, and sustainable development. The research carried out needs to be continued so that changes in the perception of environmental risks can be tracked.

In the context of the research results obtained, it is essential to emphasise the need for further action by local government units, especially municipalities, to improve the state of the environment, which is crucial for advancing sustainable development at the local scale. Moreover, it should be noted that these actions should be both restorative (aimed at repairing the damage to the environment that has already occurred) and preventive—designed to avoid the degradation of this environment. As already raised in the literature on the subject [84], local authorities may have an impact on the level of all quality of life measures in the area of “quality of the natural environment in the place of residence” (exposure to excessive noise, exposure to pollution or other environmental problems, satisfaction with recreational areas and green areas), but it is a matter of adopting specific sustainable development priorities in a particular municipality in terms of spending public funds and implemented investments.

Considering the importance attributed to the indicated area of creating the desired quality of life in both national and international documents (UN, EU), it should be postulated that in the activities of local government units greater attention should be paid to the environmental determinants of the quality of life of citizens, and at the same time sustainable social and economic development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, W.K., A.L. and P.L.; methodology, W.K., A.L. and P.L.; software, P.L.; validation, W.K., A.L. and P.L., formal analysis, A.L. and P.L.; investigation, A.L. and P.L.; resources, W.K.; data curation, A.L. and P.L.; writing—original draft preparation, W.K. and A.L.; writing—review and editing, P.L.; visualisation, A.L. and P.L.; funding acquisition, P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations. Agenda 21: Programme of Action for Sustainable Development. United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), Rio de Janeiro. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://docs.un.org/en/A/RES/70/1 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- European Council. A Sustainable Europe for a Better World: A European Union Strategy for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52001DC0264 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- European Council. Renewed EU Sustainable Development Strategy. Council of the European Union. Available online: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-10917-2006-INIT/en/pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Zadrożniak, M. Jakość życia w kontekście koncepcji zrównoważonego rozwoju. Acta Univ. Lodziensis. Folia Oeconomica 2015, 2, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Katana, K. Istota jakości życia w koncepcji zrównoważonego rozwoju. Zesz. Nauk. Politech. Śląskiej. Ser. Organ. I Zarz. 2016, 95, 175–187. [Google Scholar]

- Cusack, C. Sustainable Development and Quality of Life. In Multidimensional Approach to Quality of Life Issues; Sinha, B.R.K., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, M.M. Improving the quality of life for sustainable development. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 561, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felce, D.; Perry, J. Quality of life: Its definition and measurement. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2019, 16, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto Torres, L.D.; Asmus, G.F.; Cal Seixas, S.R. Quality of Life and Sustainable Development. In Encyclopedia of Sustainability in Higher Education; Leal Filho, W., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štreimikiene, D.; Barakauskaite-Jakubauskiene, N. Sustainable Development and Quality of Life in Lithuania compared to other Countries. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2012, 18, 588–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryk, B. Środowiskowe uwarunkowania jakości życia w województwie zachodniopomorskim na tle Polski. Ekon. I Sr. 2015, 3, 170–181. [Google Scholar]

- Petelewicz, M.; Drabowicz, T. Jakość życia—Globalnie i Lokalnie. Pomiar i Wizualizacja; Wydawnictwo UŁ: Łódź, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gazzola, P.; Querci, E. The Connection Between the Quality of Life and Sustainable Ecological Development. Eur. Sci. J. 2017, 13, 361–375. [Google Scholar]

- Lorek, A. Usługi Ekosystemów w Rozwoju Zrównoważonym Gmin Regionu Wysoko Zurbanizowanego; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Katowicach: Katowice, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, H.; El-Walid, N.; Ben, K. Quality of Life as a Model for Achieving Sustainable Development -An Approach Study in the Light of Experiences of Some Leading Countries. Int. J. Inspir. Resil. Econ. 2019, 2, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski, M.; Wasiuta, A. Stan Środowiska a Poziom Życia Ludności w Polsce; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bąk, I. Regional diversity of the environmental quality of life in Poland. Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technology. Organ. Manag. Ser. 2023, 168, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacione, M. Urban environmental quality and human wellbeing—A social geographical perspective. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 65, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, G. Quality of life and sustainability: Toward person-environment congruity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorek, E.; Dubiel, B.; Lorek, A.; Mańkowska-Wróbel, L.; Słupik, S.; Sobol, A. Biznes Ekologiczny. Ekorynek, Ekokonsument, Ekostrategie Firm; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Katowicach: Katowice, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lorek, A.; Lorek, P. Social Assessment of the Value of Forests and Protected Areas on the Example of the Silesian Voivodeship. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBOS. Świadomość Ekologiczna Polaków. Komunikat z Badań Nr 163/2020. Available online: https://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2020/K_163_20.PDF (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- GUS. Jakość Życia i Kapitał Społeczny w Polsce. Wyniki Badania Spójności Społecznej 2018. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/warunki-zycia/dochody-wydatki-i-warunki-zycia-ludnosci/jakosc-zycia-i-kapital-spoleczny-w-polsce-wyniki-badania-spojnosci-spolecznej-2018,4,3.html (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Bołtromiuk, A.; Burger, T. Polacy w Zwierciadle Ekologicznym. Raport z Badań nad Świadomością Ekologiczną Polaków w 2008r. Available online: https://www.pine.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/pdf/polacy_w_zwierciadle_ekol.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Bołtromiuk, A. Świadomość Ekologiczna Polaków—Zrównoważony rozwój—Raport z Badań 2009. Available online: https://odpowiedzialnybiznes.pl/wp-content/uploads/attachments/news/Swiadomosc_ekologiczna_Polakow_InE_2009.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Stanaszek, A.; Tędziagolska, M. Badanie Świadomości Ekologicznej Polaków 2010 ze Szczególnym Uwzględnieniem Energetyki Przyjaznej Środowisku. Available online: https://www.pine.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/pdf/badanie_swiad_ekol_polakow_.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- CBOS. Zachowania Proekologiczne Polaków. Available online: https://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2011/K_023_11.PDF (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Ministerstwo Klimatu i Środowiska. Badanie Świadomości i Zachowań Ekologicznych Mieszkańców Polski. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/attachment/71c6a10d-4b7a-44a9-872d-f3f6434a7d01 (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Millenium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis. Available online: https://www.millenniumassessment.org/documents/document.356.aspx.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- World Health Organization. Preventing Disease Through Healthy Environments: A Global Assessment of the Burden of Disease from Environmental Risks. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565196 (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Borys, T.; Rogala, P. Jakość Życia na Poziomie Lokalnym—Ujęcie Wskaźnikowe; UNDP: Warszawa, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Quality of Life. Facts and Views; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Reig-Mullor, J.; Garcia-Bernabeu, A.; Pla-Santamaria, D.; Salas-Molina, F. Measuring quality of life in Europe: A new fuzzy multicriteria approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 206, 123494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borys, T. Jakość życia jako kategoria badawcza i cel nadrzędny. In Jak Żyć? Wybrane Problemy Jakości Życia; Wachowiak, A., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Fundacji “Humaniora”: Poznań, Poland, 2001; pp. 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, D. Quality of Life: Concept, Quality, Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jankiewicz-Siwek, A.; Bartosińska, D. Jakość życia—Istota, uwarunkowania, wskaźniki oraz praktyka badań w Polsce. Ann. Univ. Mariae Curie-Skłodowska Sect. H Oeconomia 2011, 45, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sztumski, J. Jakość życia jako kategoria socjologiczno-ekonomiczna. In Polityka Społeczna Wobec Problemu Bezpieczeństwa Socjalnego w Dobie Przeobrażeń Społeczno—Gospodarczych; Koczur, W., Rączaszek, A., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Katowicach: Katowice, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Michalska-Żyła, A. Jakość życia na poziomie lokalnym. Acta Univ. Lodziensis. Folia Sociol. 2016, 56, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, A.; Ghellini, G.; Navarro, M.; Sanchez, A. Overview of Quality of Life in Europe. In Analysis of Socio-Economic Conditions: Insights from a Fuzzy Multidimensional Approach; Betti, G., Lemmi, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 120–133. [Google Scholar]

- Wesz, J.G.B.; Miron, L.I.G.; Delsante, I.; Tzortzopoulos, P. Urban Quality of Life: A Systematic Literature Review. Urban Sci. 2023, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcaccia, B.; Esposito, G.; Matarese, M.; Bertoloso, M.; Elvira, M.; De Marinis, M.G. Defining Quality of Life: A Wild-Goose Chase ? Eur. J. Psychol. 2013, 9, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzebiatowski, J. Jakość życia w perspektywie nauk społecznych i medycznych—Systematyzacja ujęć definicyjnych. Hygeia Public Health 2010, 46, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, A.; Converse, P.E.; Rodgers, W.L. The Quality of American Life: Perceptions, Evaluations and Satisfactions; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Kata, J. Jakość życia w wymiarze społecznym—Dyskurs teoretyczny. PROSOPON. Eur. Stud. Społeczno-Humanist. 2018, 25, 229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Rada Monitoringu Społecznego. Diagnoza Społeczna. 2000. Available online: http://www.diagnoza.com/pliki/raporty/Diagnoza_raport_2000.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Rada Monitoringu Społecznego. Diagnoza Społeczna. 2003. Available online: http://www.diagnoza.com/files/raport2003.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Rada Monitoringu Społecznego. Diagnoza Społeczna. 2005. Available online: http://www.diagnoza.com/files/diagnoza2005/raport_diagnoza2005_110106.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Rada Monitoringu Społecznego. Diagnoza Społeczna. 2007. Available online: http://www.diagnoza.com/pliki/raporty/Diagnoza_raport_2007.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Rada Monitoringu Społecznego. Diagnoza Społeczna. 2009. Available online: http://www.diagnoza.com/pliki/raporty/Diagnoza_raport_2009.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Rada Monitoringu Społecznego. Diagnoza Społeczna. 2011. Available online: http://www.diagnoza.com/pliki/raporty/Diagnoza_raport_2011.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Rada Monitoringu Społecznego. Social Diagnosis. 2013. Available online: http://www.diagnoza.com/data/report/report_2013.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Rada Monitoringu Społecznego. Social Diagnosis. 2015. Available online: http://www.diagnoza.com/pliki/raporty/Diagnoza_raport_2015.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Gotowska, M. Jakość życia, poziom jakości życia, równowaga bytu—Dyskusja trwa. Stud. I Pr. Wydziału Nauk. Ekon. Zarządzania 2014, 37, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kaniewska-Mackiewicz, E. Problematyka jakości życia w dyskursie nauk społecznych. Zesz. Nauk. WSG. Ser. Eduk.-Rodz.-Społeczeństwo 2021, 6, 201–222. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, J.M.; Amekudzi, A. Quality of Life, Sustainable Civil Infrastructure, and Sustainable Development: Strategically Expanding Choice. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2011, 137, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siedlecka, A. Obiektywna jakość życia jako kategoria rozwoju zrównoważonego na przykładzie gmin województwa lubelskiego. In Jakość Życia a Zrównoważony Rozwój; Rusnak, Z., Zmyślona, B., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2013; pp. 149–169. [Google Scholar]

- Turkoglu, H. Sustainable Development and Quality of Urban Life. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 202, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubów, A. Infrastruktura społeczna jako narzędzie polityki społecznej. In Wyzwania Polityki Społecznej. Wybrane Aspekty; Kubów, A., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesli, T.X.; Liebe, U.; Hammer, T.; Bär, R. Sustainable Quality of Life: A Conceptualization That Integrates the Views of Inhabitants of Swiss Rural Regions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Report on the Quality of Life in European Cities; Publications Office of European Union: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szukiełojć-Bieńkuńska, A. Pomiar jakości życia w statystyce publicznej. Wiadomości Stat. 2015, 7, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- GUS. Jakość Życia w Polsce. Edycja. 2017. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/5486/16/4/1/jakosc_zycia_w_polsce_2017.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- GUS. Green Economy Indicators in Poland. 2022. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/environment-energy/environment/green-economy-indicators-in-poland-2022,3,5.html (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Kozaczyński, W. Zrównoważony rozwój a bezpieczeństwo człowieka. Bezpieczeństwo. Teor. I Prakt. 2012, 4, 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Granit, J.; Eriksson, M.; Carlsen, H.; Andersson, C.; Carson, M.; Hallding, K.; Johnson, O.; Rosner, K.; Weitz, N.; Liljedahl, B.; et al. Integrating Sustainable Development and Security: An Analytical Approach with Examples from the Middle East and North Africa, the Arctic and Central Asia. SEI Working Paper No. 2015-14. Available online: https://www.sei.org/mediamanager/documents/Publications/SEI-FOI-WP-2015-14-Security-sustainable-development.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Stiglitz, J.; Fitoussi, J.P.; Durand, M. (Eds.) For Good Measure: Advancing Research on Well-Being Metrics Beyond GDP; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jarmoszko, S. Kultura bezpieczeństwa społecznego a kwestia zrównoważonego rozwoju. Kult. Bezpieczeństwa 2020, 6, 97–126. [Google Scholar]

- Biloshkurska, N.; Omelyanenko, V.; Yemets, O.; Braslavska, O.; Matkovskyi, P.; Omelianenko, O.; Korniienko, T. Comprehensive human security assessment in sustainable regional development: Insights for innovation policy. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. Res. 2025, 9, em0315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomać-Pierzecka, E.; Błaszczak, B.; Godawa, S.; Kęsy, I. Human Safety in Light of the Economic, Social and Environmental Aspects of Sustainable Development—Determination of the Awareness of the Young Generation in Poland. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R.; Welzel, C. Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Human Development Report. 1994. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-1994 (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- UNDP. Human Development Report. 2020. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2020 (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Gołębiowska, A.; Prokopowicz, D.; Such-Prygiel, M. Human security as an element of the Concept of Sustainable Development in International Law. J. Moder Sci. 2023, 3, 36–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasny, J. Poziom i jakość życia ludności oraz źródła i mierniki ich określania. Ruch Praw. Ekon. I Socjol. 1993, 2, 73–92. Available online: https://repozytorium.amu.edu.pl/items/e9a0e47c-4930-43ba-85cd-e60699531505 (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Dmoch, T.; Rutkowski, J. Badanie poziomu i jakości życia. Wiadomości Stat. 1995, 10, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Zalewska, M. Jakość życia—Wybrane koncepcje. Analiza porównawcza wskaźników jakości życia w Polsce i krajach UE. Probl. Zarządzania 2012, 10, 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUS. Atlas Statystyczny Polski. Społeczeństwo-Jakość Życia-Przestrzeń. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/inne-opracowania/inne-opracowania-zbiorcze/atlas-statystyczny-polski-spoleczenstwo-jakosc-zycia-przestrzen,53,1.html (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Oleszko-Kurzyna, B. Jakość życia a procesy zarządzania rozwojem gmin wiejskich. In Polityka Społeczna Wobec Problemu Bezpieczeństwa Socjalnego w Dobie przeobrażeń Społeczno—Gospodarczych; Koczur, W., Rączaszek, A., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Katowicach: Katowice, Poland, 2014; pp. 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kubów, A. Infrastruktura społeczna a jakość życia. In Społeczeństwo a Zmiana; Kowalczyk, O., Kubów, A., Watroba, W., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Grewiński, M. Usługi Społeczne We Współczesnej Polityce Społecznej; Dom Wydawniczy Elipsa: Warszawa, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Stangierska, D.; Kowalczuk, I.; Juszczak-Szelągowska, K.; Widera, K.; Ferenc, W. Urban Environment, Green Urban Areas, and Life Quality of Citizens—The case of Warsaw. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoobi, A.W.; Mehdizade, A. Exploring the Interrelationship Between Sustainability and Ouality of Life in Urban Design: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Shared and Distinct Indicators. Architecture 2025, 5, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlińska, J. Wpływ władz lokalnych na poprawę jakości życia mieszkańców danego terenu. Nierówności Społeczne A Wzrost Gospod. 2018, 56, 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sample Size Calculator. Available online: https://goodcalculators.com/sample-size-calculator/ (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- GUS. Polska w Liczbach. 2023. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/download/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/5501/14/16/1/polska_w_liczbach_2023_pl_pi.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- ESOMAR. ICC/ESOMAR: International Code on Market, Opinion and Social Research and Data Analytics; ESOMAR World Research; International Chamber of Commerce: Paris, France, 2016; Available online: https://iccwbo.org/news-publications/policies-reports/iccesomar-international-code-market-opinion-social-research-data-analytics/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- GIOŚ. Stan Środowiska w Polsce. Raport. 2022. Available online: https://siedliska.gios.gov.pl/images/pliki_pdf/publikacje/Raporty%20i%20ekspertyzy/Stan_srodowiska_w_Polsce_-_raport_2022.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- GUS. Wskaźniki Zielonej Gospodarki w Polsce. 2024. Available online: https://bialystok.stat.gov.pl/publikacje-i-foldery/ochrona-srodowiska/wskazniki-zielonej-gospodarki-w-polsce-2024,5,6.html (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Klima, E.; Janiszewska, A.; Ciosek, A.; Cichowicz, R. Air Pollution in Residential Areas of Monocentric City Agglomerations: Objective and Subjective Dimensions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieliwończyk, T. Protest Przeciwko Wycince Lasu na Wyspie Sobieszewskiej. Available online: https://gdansk.tvp.pl/83845129/protest-przeciwko-wycince-lasu-na-wyspie-sobieszewskiej (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Żelazowska, A. Mieszkańcy Wyspy Sobieszewskiej Protestują: Zostawcie Nasz las w Spokoju! Co na to leśnicy? Oni Mają Swoje Argumenty. Available online: https://trojmiasto.wyborcza.pl/trojmiasto/7,35612,31520630,mieszkancy-mowia-drzewa-lesnicy-kubiki-spor-o-las-na-wyspie.html (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Abramowicz, D. Gdańsk: Uda się Powstrzymać Wycinkę 180-Letnich Buków na Terenie Planowanego Rezerwatu Lasy Oliwskie? Available online: https://www.zawszepomorze.pl/artykul/11097,gdansk-uda-sie-powstrzymac-wycinke-180-letnich-bukow-na-terenie-planowanego-rezerwatu-lasy-oliwskie (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Stenzel, D. Wycinka Drzew w Jelitkowie: Prezydent Gdańska Składa Zawiadomienie do Prokuratury. Available online: https://www.gdansk.pl/wiadomosci/Wycinka-drzew-w-Jelitkowie-prezydent-Gdanska-sklada-zawiadomienie-do-prokuratury,a,212528 (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Balicki, S. Włodarze Trójmiasta: “Lasy Państwowe chcą ukryć zwiększone wycinki drzew”. Leśnicy: “Realizujemy Plany Poprzedniego Rządu”. Available online: https://dziennikbaltycki.pl/wlodarze-trojmiasta-lasy-panstwowe-chca-ukryc-zwiekszone-wycinki-drzew-lesnicy-realizujemy-plany-poprzedniego-rzadu/ar/c8-16704237 (accessed on 19 August 2022).

- Murawska, A.; Sieg, P.; Stereńczak, S. Environmental Safety and Self-Perceived Quality of Life and Health: The Example of the European Union. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Urriata, X.; Yepez-Villacis, R.; Miranda, A.M.; Nogales-Portero, R.; Alvarez, E. Quality of Life and Environmental Degradation: An Empirical Assessment of Their Interactions and Determinants in Latin America and the Caribbean. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedlova, P.; Tomaskova, H.; Slachtova, H.; Babjakova, J.; Jirik, V. The Impact of Environmental Conditions on Lifestyle Quality in Industrial and Non-Industrial Region in the Czech Republic. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1505170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).