Abstract

The use of mercury in industry causes its continuous increase in nature. A pro-ecological technology that can reduce mercury levels in aquatic environments is phytoremediation using the plant Salvinia natans. The study aimed to determine the maximum mercury concentration for effective phytoremediation using Salvinia natans. The study aimed to determine the threshold for effective phytoremediation using Salvinia natans. A Microtox screening test was performed for concentrations ranging from 0.15 to 0.50 mg Hg·L−1. For the same concentrations, the effect of contamination on the physiological condition of the plant was tested by observing changes in the presence of chlorosis and necrosis. Analysis of enzymatic activity using the API ZYM test for plants exposed to mercury did not show any significant changes. The phytoremediation process produces a significant amount of spent phytoremediation biomass containing large amounts of mercury. Sustainable management in the form of a mixture with soil substrate, uncontaminated with mercury, was proposed. Microtox toxicity analysis of water extracts from soil containing biomass, with a final mercury content in the substrate of 1 mg Hg·kg−1 of soil, showed no toxicity to the environment. However, microbiological analysis of the same soil substrate showed changes in the total number of bacteria, actinomycetes, fungi, moulds, and yeasts compared to the control samples.

1. Introduction

Mercury is toxic even at low concentrations and after short-term exposure. The protection of the aquatic environment is particularly important. Mercury can easily enter the human body through water, either through direct consumption or through food [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. The amount of mercury in the aquatic environment is constantly increasing, and its presence is increasingly being reported in regions of the world where it was previously absent [8]. Its accumulation in bottom sediments is a major problem [9,10,11]. Mercury enters marine waters along with other pollutants from rivers into which sewage, including industrial wastewater, is discharged [12,13].

Aquatic microorganisms can biochemically transform mercury, including the methylation of inorganic mercury into methylmercury. This is a very dangerous form with a high degree of bioaccumulation [5,14,15,16,17].

Mercury, like other heavy metals, accumulates in the tissues of humans, animals, and plants. The variability of mercury’s chemical forms in the environment and the problem of its biomagnification have led to the search for effective methods of its removal [12,18]. One of them is phytoremediation. This is a biological method of removing pollutants from water, soil, and even air. Among plants, there are numerous bioaccumulators known to be capable of purifying the environment even from high concentrations of heavy metals, including mercury [1,2,3,5]. One of the plants that can be successfully used in the process of phytoremediation is Salvinia natans. It is characterised by rapid growth, high tolerance to heavy metals, and an innate ability to absorb large amounts of heavy metals in its tissues, mainly in the roots and leaves [19]. This plant mainly occurs in Eurasia and North America [20]. It is characterised by rapid growth and the ability to adapt to various freshwater environments, both flowing and standing waters [21]. Studies have shown that this plant can accumulate, primarily in its roots, heavy metals such as cadmium, chromium, copper, nickel, lead, iron, manganese, and zinc. The obtained values for bioconcentration and translocation factors indicate that it may be classified as a hyperaccumulator. However, conducting metal removal processes through phytoremediation requires knowledge of the extent to which a given element can be removed by a specific plant for it to be effective [22]. Additionally, in the case of organic pollutants, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, they exhibit bioaccumulative properties [23]. Mercury disrupts the synthesis of assimilation pigments and, consequently, photosynthesis processes, which are the basis of plant metabolism. This element accumulates mainly in the roots of plants, protecting the above-ground parts (leaves and stems). This leads to disturbances in the transport of water and nutrients in plants. In addition, mercury can lead to biochemical changes, especially in enzyme activity. Monitoring changes in plant biochemical activity during phytoremediation has a significant impact on its effectiveness. Disturbances in this area can lead to abnormal plant functioning, thereby disrupting the phytoremediation process and significantly reducing its effectiveness [2]. Phytoremediation is often supported by microorganisms in order to achieve better results. This method allows for the creation of chelating agents, which increase the resistance of plants to heavy metals. It also improves the ability to translocate and accumulate heavy metals in plants. An important role of microorganisms in the phytoremediation process is also their ability to alleviate stress caused by the presence of heavy metals in the substrate [24,25].

Mercury, as a toxic element, hurts plant organisms and soil microorganisms. The study aimed to determine the impact of mercury on organisms in terms of the possibility of phytoremediation using the plant Salvinia natans and the possibility of utilising the resulting biomass. An acute toxicity test was performed for selected mercury concentrations, determining toxicity classes in accordance with the test manufacturer’s criteria. The impact of mercury on Salvinia natans was assessed based on the occurrence of chlorosis and necrosis, as well as plant death, for different mercury concentrations in the substrate. An enzymatic activity test was also performed on plants exposed to mercury. The phytoremediation process always generates a significant amount of contaminated biomass, which is difficult to manage because it is highly toxic. It is therefore important to develop solutions to prevent this. A mixture of control sample and biomass with mercury in a final amount of 1 mgHg·kg−1 of soil was proposed. A Microtox toxicological test was performed on water extracts from soil with mercury-containing biomass, and a microbiological analysis of this material was performed in comparison with a control sample and soils with biomass without mercury.

The results obtained may contribute to a better understanding of the impact of mercury on Salvinia natans plants and may be used in the process of removing it from the aquatic environment and in the possible utilisation of the resulting biomass.

2. Materials and Methods

The aim of the study was to determine the toxicity of mercury on a plant that could potentially be used in the phytoremediation (an environmentally friendly method of cleaning the environment) of mercury from the aquatic environment. The research focused on the floating fern Salvinia natans due to its widespread occurrence in Eurasia and North America [20]. Previous scientific studies have also shown that this plant has a predisposition to carry out the process of heavy metal phytoremediation [19,22].

Mercury (II) nitrate, an inorganic form of mercury with high water solubility, was selected for mercury toxicity assessment studies. Since toxicity assessment studies using the commercial Microtox test are conducted using marine bacteria, and the test itself is conducted in aqueous solutions, the solubility of the test substance in aqueous solutions is of significant importance for the test results.

The study applied mercury concentrations ranging from 0.15 mg Hg·L−1 to 0.50 mg Hg·L−1. These are concentrations of mercury that significantly exceed permissible values in surface waters or those intended for drinking [26]. However, the mercury content in municipal wastewater sediments can be as high as 8 mgHg·kg−1 [27], and in industrial wastewater, it can increase to 10 mg Hg·L−1 [26]. This leads to the accumulation of mercury in the bottom sediments of reservoirs and watercourses. In the sediments of rivers, the mercury content can reach up to 0.30 mg·kg−1, and it may be periodically released, causing its concentration in the water to intermittently increase sharply [28].

The study was divided into three stages. The first stage involved testing the toxicity of selected mercury concentrations using the Microtox test. Based on the results obtained, three concentrations were selected for the next stage involving Salvinia natans plants. The second stage is to determine the effect of mercury on Salvinia natans plants exposed to selected concentrations of this metal in the substrate. The study included a visual assessment of the plants to observe changes such as chlorosis and necrosis. Plant growth, changes in the amount of protein and total chlorophyll in plant tissues, and plant enzyme activity were assessed. A negative aspect of phytoremediation is the formation of a significant amount of phytoremediation biomass containing large amounts of heavy metals. In the case of the conducted research, an attempt was made to utilise the resulting biomass as ‘soil material’ that could be used in construction or decorative gardening. The toxicity of the resulting product was also assessed. The study of phytoremediation biomass was the third stage of the research.

2.1. Mercury Toxicity-MICROTOX Test

The Microtox test (Microtox is the trade name of Microbiox Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA) is an internationally recognized acute toxicity test. It complies with ASTM (American Society for Testing and Materials) standard methods. The test uses marine bacteria Allivibrio fischeri, which can emit light. However, this ability is disrupted in the presence of toxic substances. Placing the bacteria in a contaminated environment causes abnormalities in metabolic processes, resulting in a significant reduction in intensity or complete disappearance of luminescence. This phenomenon is used in the Microtox test. The luminescence of bacteria is measured under conditions favourable to the test organisms (control) and after 5 and 15 min of contact with the test samples. The luminescence measurement time is based on the structure of the test bacterium’s cell membrane and its permeability to inorganic (5 min) and organic (15 min) substances [29].

A screening test was conducted for five concentrations of mercury(II) nitrate: 0.15 mg Hg·L−1, 0.20 mg Hg·L−1, 0.30 mg Hg·L−1, 0.40 mg Hg·L−1, and 0.50 mg Hg·L−1. Mercury(II) nitrate was dissolved in deionised water. The tests were performed in duplicate. Based on the results, the effective concentration (EC50) was determined. The Microtox test was performed according to the manufacturer’s SDI procedure on a Microtox M500 analyser (Strategic Diagnostics Inc., Newark, NJ, USA). The control sample was a substrate dedicated to the Microtox test in accordance with its procedure. Results were processed using Microtox Omni Software and presented as a percentage of toxic effect (PE). Based on the obtained results, the samples were classified into the following toxicity classes according to the manufacturer’s criteria:

- ➢

- Class I: no toxicity (PE ≤ 20%)

- ➢

- Class II: low toxicity hazard (20% < PE ≤ 50%)

- ➢

- Class III: acute toxicity hazard (50% < PE ≤ 100%)

- ➢

- Class IV: high acute toxicity hazard (at least one test sample obtained a PE = 100%)

- ➢

- Class V: very high acute toxicity hazard (all test samples obtained a PE = 100%)

2.2. Study of the Effects of Mercury on Salvinia natans

The study was conducted on the Salvinia natans aquatic plant purchased from a commercial farm. During the experiment, the plants were grown on modified Hoagland medium (composition: KNO3—1.02 g·L−1; Ca(NO3)2·4H2O—0.71 g·L−1; NH4H2PO4—0.23 g·L−1; MgSO4·7H2O—0.49 g·L−1; MnCl2·4H2O—1.81 mg·L−1; H3BO3—2.86 mg·L−1; CuSO4·5H2O—0.08 mg·L−1; ZnSO4·7H2O—0.22 mg·L−1; FeSO4·7H2O—0.60 mg·L−1). It is a liquid medium characterised by a balanced content of micro- and macroelements necessary for proper plant growth [30,31]. The solution had a pH of 4.0–4.5 after adding mercury. Modified Hoagland medium was used as a control, and in the case of studies with mercury, this medium was contaminated with mercury(II) nitrate. Mercury nitrate in the form of a Merck ASA standard at a concentration of 1000 mg Hg·L−1 was added in the appropriate amount to the modified Hoagland medium.

2.2.1. Visual Assessment of Plants Exposed to Mercury

Studies of the effects of mercury on Salvinia natans plants began with preliminary tests. The tests were conducted at the same mercury concentrations in the substrate as in the Microtox test: 0.15 mg Hg·L−1, 0.20 mg Hg·L−1, 0.30 mg Hg·L−1, 0.40 mg Hg·L−1, and 0.50 mg Hg·L−1. Mercury exposure was conducted in seedbeds, each containing 500 mL of nutrient medium and 5 g of plants. In order to maintain constant conditions, the experiment was conducted in a Biosell (Feucht, Germany) FD 147 Inox phytotron equipped with OSRAM (Munich, Germany) 18W/965 Biolux fluorescent lamps, in a day/night cycle (12 h/12 h), at a temperature of 22 ± 2 °C/15 ± 2 °C, with air humidity of 40%. A general assessment of the physiological condition of the plants following short-term (14-day) exposure to mercury was performed. This assessment was performed by visually assessing the presence of chlorosis and necrosis on the leaf surface. The assessment was based on a qualitative (yes/no) and quantitative (point scale: 1–5, where 1 point means no chlorosis or necrosis, and 5 points means the highest presence of chlorosis and necrosis observed in the study) evaluation. The results were documented with photographs.

2.2.2. Enzymatic Activity Test-API ZYM Test

The API ZYM test (BioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) is a micromethod enabling the rapid assessment of the enzymatic profile of biological material, typically microorganisms, cell suspensions, or tissues. The test is recommended for screening studies. The obtained results form the basis for further, more detailed studies of the enzymatic activity of the tested samples. The test detects the activity of 19 selected enzymes (Table 1). The test uses strips with 20 reaction chambers. The first is a negative control, i.e., a well without the substrate necessary for the enzymatic reaction to occur. The remaining 19 contain the appropriate substrates (Table 1). If the biological material contains the appropriate enzymes, the reaction causes a colour change in the contents of the reaction chamber. Colour saturation indicates the intensity of the enzymatic reaction, and indirectly, the number of enzymes responsible for it. Visual assessment of colour intensity and the inclusion of a scale allow for comparison of the intensity of enzymatic processes in different samples. Therefore, this test is considered semi-quantitative.

Table 1.

Enzyme substrates in API ZYM test.

As part of the study, the API ZYM test was performed on Salvinia natans plants exposed to mercury. The plants were placed in Hoagland medium contaminated with mercury(II) nitrate to a concentration of 0.20 mg Hg·L−1 for 21 days. Plants for the API ZYM test were collected at 7-day intervals and tested.

To perform the API ZYM test on plants, a homogenate was prepared. To do this, 1 g of averaged Salvinia natans plant biomass was weighed and then homogenised in a chilled mortar with 4 mL of ice-cold deionised water. The homogenate was centrifuged for 10 min at 4 °C at 15,000× g. The resulting supernatant, 0.065 mL, was added to the API ZYM test reaction chambers. Incubations were carried out in the dark at 37 °C for 2 h. Then, according to the manufacturer’s procedure, a drop of ZYM A and ZYM B reagents was added to each reaction chamber of the test strip. Readings were performed visually. The results were presented on an accepted 6-point scale of 0–5 depending on the intensity of the reaction (colour intensity) compared to the API ZYM test control.

2.3. Toxicity of Spent Phytoremediation Biomass

The resulting spent phytoremediation biomass may contain significant amounts of mercury. An attempt was made to assess the toxicity of the mixture of garden soil and phytoremediation biomass in order to enable its use, e.g., in construction or decorative gardening. However, this requires the use of appropriate proportions in the soil substrate mixture with the mercury-containing biomass. This mixture must not be toxic to the natural environment. In the conducted studies, a mixture of compost and mercury-containing biomass was used in proportions that allowed for a final mercury concentration of 1 mg Hg·kg−1 DM (dry matter) of soil substrate. After drying the phytoremediation biomass to an air-dry form, its mercury content was determined using an Altem AMA 254 atomic absorption spectrometer (Altec, Prague, Czech Republic). Knowing the mercury content in the biomass, the necessary calculations were made to determine the proportions in which the compost should be mixed with the biomass. The resulting mixture was again tested for mercury content using an Altem AMA 254 atomic absorption spectrometer to check the final mercury content in the soil substrate. The introduction of plant biomass into the soil can change its environmental conditions, e.g., the availability of nutrients, which may affect the number of microorganisms or the toxicity of the soil. Therefore, an additional soil sample was prepared. Plant biomass was added to the compost in the same mass quantity as before for biomass containing mercury, but in this case, the biomass did not contain mercury (it came from phytoremediation control samples).

Aqueous extracts were used to assess the toxicity of the tested soil material. The soil substrate was dried at room temperature to an air-dry state. One gram of the substrate was then weighed and added to 9 cm3 of sterile physiological saline. A 10-min ultrasonic cavitation process was applied, after which the resulting suspension was centrifuged (10 min at 4 °C at 15,000× g). The supernatant obtained was filtered through a soft qualitative filter. The prepared solutions were used for further testing (Section 2.3.1 and Section 2.3.2).

2.3.1. Microtox Test

A Microtox screening test was performed on the supernatants obtained for compost, compost with biomass and compost with biomass containing mercury. The Microtox test was performed in two replicates. The control was a substrate dedicated to the Microtox test in accordance with its procedure. Luminescence measurements for the control and the tested soil extract samples were performed after 5 and 15 min. The Microtox test was performed in accordance with the SDI manufacturer’s procedure. A Microtox M500 analyser was used for the test, and the results were processed using Microtox Omni Software. The results obtained are presented as a percentage of the toxic effect (TE). Based on the results obtained, the samples were classified according to the manufacturer’s criteria specified in Section 2.1.

2.3.2. Microbiological Analysis

Analysis of changes in the number of microorganisms in the soil substrates included the total number of mesophilic bacteria (enriched agar medium, 48-h incubation at 36 ± 2 °C) and psychrophilic bacteria (enriched agar medium, 72-h incubation at 20 ± 2 °C), actinomycetes (Pochona medium, 6-day incubation at 26 ± 2 °C), fungi, yeasts, and molds (Czapek-Dox and Sabouraud medium, 6-day incubation at 26 ± 2 °C) (Table 2). Microbiological analysis of the composts was performed using standard microbiological methods, i.e., the Koch plate method with a minimum of four repetitions. The results obtained are presented as the number of colony-forming units per gram of the tested soil sample (CFU·g−1). The microbiological analysis was intended to preliminarily determine changes in the total number of bacteria and fungi in the soil under the influence of mercury.

Table 2.

Composition of microbiological substrates.

The results obtained were subjected to statistical analysis using a one-way non-parametric analysis of variance (ANOVA)—the Kruskal-Wallis test—and a post-hoc test (Dunna test) consistent with this test was performed. The statistical analysis was performed using Excel Office 2019. The results are presented in the form of a bar chart with standard error.

3. Results

3.1. Mercury Toxicity-Microtox Test

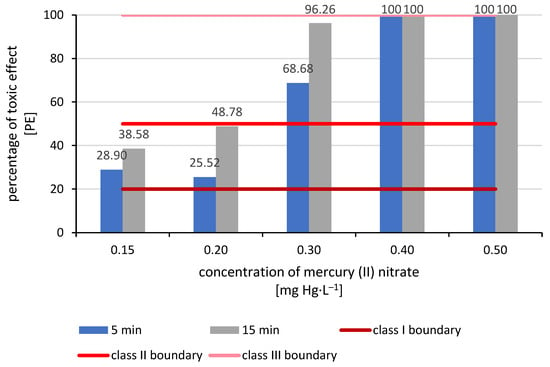

The lowest toxicity effect was obtained for a concentration of 0.15 mg Hg·L−1. After 5 min, bacterial percentage of toxic effect was 28.90%, increasing after 15 min to 38.58%. The next concentration tested was 0.20 mg Hg·L−1. After 5 min, the percentage toxicity effect was 25.52%, and, as before, after 15 min, it increased to 48.78%. Both mercury concentrations achieved percentage of toxic effect results for the test bacteria in the range of 20–50%, which classifies them as Class II—low toxicity hazard. The concentration of 0.30 mg Hg·L−1 achieved higher toxicity results, classifying it as Class III—acute toxicity hazard. After 5 min, the PE was 68.68%, while after 15 min it was as high as 96.26%. The remaining two tested concentrations, i.e., 0.40 mg Hg·L−1 and 0.50 mg Hg·L−1, obtained results of 100% PE, which classifies them as class V—very high toxic hazard (Figure 1). The effective concentration (EC50) for 5 min was 0.23 mg Hg·L−1, and for 15 min it was 0.19 mg Hg·L−1.

Figure 1.

Assessment of the toxicity of selected mercury concentrations using the Microtox test (class I boundary: no toxicity; class II boundary: low toxicity hazard; class III boundary: acute toxicity hazard).

The conducted studies have shown that mercury concentrations above 0.30 mg Hg·L−1 achieve a percentage toxic effect exceeding 50%. According to the Microtox test classification, this is Class III toxicity for the tested substances. Mercury values in the aquatic environment higher than 0.30 mg Hg·L−1 cause a strong toxic effect (≥toxicity class III according to the Microtox test manufacturer’s classification). Therefore, in further studies, we adopted lower concentrations, taking 0.30 mg Hg·L−1 as the upper limit. This process often involves not only plants but also their epiphytic bacteria. This cooperation often significantly increases the effectiveness of phytoremediated contaminant removal and is often the basis for many biochemical processes, without which phytoremediation would not occur at all.

3.2. Study of the Effect of Mercury on Salvinia natans Plants

3.2.1. Visual Assessment of Plants Exposed to Mercury

Plants play a crucial role in phytoremediation processes, as they often incorporate anthropogenic substances into their biomass to remove them from the environment. Therefore, the preliminary studies determined the effect of various mercury concentrations in aqueous solutions on Salvinia natans based on visual assessment of the condition of plants exposed to different metal concentrations. The condition of plants used in phytoremediation processes is crucial. One of the most important conditions for properly conducted phytoextraction is the appropriate level of physiological processes occurring in plant organisms. Excessively high metal concentrations can inhibit metabolic processes and even cause irreversible changes, leading to chlorosis or necrosis, and consequently, rapid deterioration of plant condition and even death. The condition of plants significantly deteriorated as a result of their 14-day exposure to mercury, as seen in the photos (Figure 2). Changes in leaf colour (chlorosis) are visible from concentrations as low as 0.15 mg Hg·L−1, most likely the result of disturbances in chlorophyll production. At higher concentrations, 0.20–0.40 mg Hg·L−1, individual clusters of necrosis were additionally observed, likely resulting from reduced plant resistance to pathogens, which resulted in changes in leaf colour due to disease lesions. Plants exposed to mercury concentrations of 0.15 mg Hg·L−1, 0.20 mg Hg·L−1, and 0.30 mg Hg·L−1 were characterised by a decrease in colour intensity and pathological lesions appearing on the leaf edges, most likely resulting from metabolic disorders caused by the presence of the toxin in the substrate. The number of pathogenic individuals in the population also increased with increasing mercury levels in the substrate. The worst condition was observed in plants exposed to mercury at a concentration of 0.50 mg Hg·L−1, where virtually all plants in the culture started the death phase (Figure 2). According to the quantitative (point) assessment of chlorosis and necrosis, the following results were obtained: 0.15 mg Hg·L−1—1 point; 0.20 mg Hg·L−1—1 point; 0.30 mg Hg·L−1—2 points; 0.40 mg Hg·L−1—4 points; 0.50 mg Hg·L−1—5 points.

Figure 2.

Morphological changes in Salvinia natans plants exposed to selected mercury concentrations (14 days).

As in the case of the Microtox test, the results here also indicate that the upper limit for researching mercury phytoremediation is 0.30 mg Hg·L−1. The physiological condition of the plants, as evidenced by the degree of changes in their leaves, remained at a level that allowed mercury phytoremediation to be conducted. However, the premature death of plant organisms can lead to secondary contamination due to the release of mercury from decomposing tissues.

3.2.2. Enzymatic Activity Test-API ZYM Test

The API ZYM test results indicated the activity of four of the 19 enzymes tested. These were acid phosphatase, naphthyl-AS-BI phosphohydrolase, leucine arylamidase, and N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase.

A colour intensity scale was used to assess the intensity of enzymatic activity in the tested samples and their changes during mercury exposure. Very low enzymatic activity was observed, even in control samples without mercury exposure. The colour intensity did not exceed 1 on a 6-point scale. Similar values were observed for samples exposed to mercury for 14 and 21 days. A slight decrease to 0.5 was observed only after the first 7 days of mercury exposure. This may have been due to environmental stress. In subsequent days, a return to the previous intensity of the tested enzymatic activities was observed (Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 3.

API ZYM test results.

Table 4.

Detailed API ZYM test results.

The lack of visible changes in enzymatic activity as a result of plant exposure to mercury may be due to the insufficient sensitivity of the test used (semi-quantitative test). It is also possible that mercury does not significantly affect the enzymes selected for the study, which is why no significant changes were observed.

3.3. Toxicity of Spent Phytoremediation Biomass

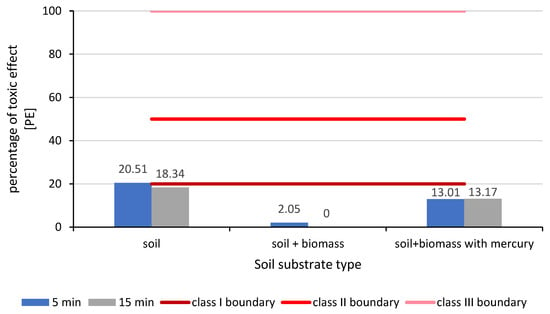

3.3.1. Microtox Test

Microtox tests of aqueous extracts from soil substrates containing mercury-contaminated biomass showed no acute toxicity (Class I, PE ≤ 20%). For aqueous extracts from soil substrates without Salvinia natans biomass and without mercury, the toxicity effect after 5 and 15 min of exposure was 20.51% and 18.34%, respectively. For extracts from soil substrates containing plant biomass not contaminated with mercury, the toxicity effect was 2.05% after 5 min, and after 15 min, the bacteria returned to full metabolic capacity. The greatest reduction in luminescence was observed for compost containing mercury-contaminated biomass, which was approximately 13% after 5 min and remained unchanged after 15 min (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Assessment of soil substrate toxicity using the Microtox test (class I boundary: no toxicity; class II boundary: low toxicity hazard; class III boundary: acute toxicity hazard).

The greatest toxicity effect was observed for the soil substrate without biomass and mercury. Only after adding Salvinia natans biomass did the Microtox test achieve a smaller reduction in the bioluminescence of the test organisms.

3.3.2. Microbiological Analysis

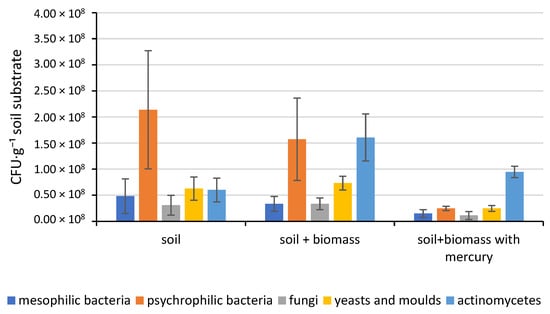

Microbiological analysis revealed that the most abundant microorganism group in the control sample substrate used for further studies was psychrophilic bacteria. Their number was 21.4 × 107 CFU·g−1 soil substrate, constituting over 51% of all microorganisms in the tested biological material. Mesophilic bacteria were significantly fewer. Their number was 4.8 × 107 CFU·g−1 soil substrate, constituting just under 12% of the quantitative microorganism count in the tested samples. The obtained results indicate a psychrophilic to mesophilic bacteria ratio of 4.4:1, a normal ratio for soils. The study also analysed the abundance of actinomycetes. Their presence in soil substrates is extremely important due to their role in the decomposition of organic and inorganic matter present in soils and composts. Their count in the reference medium was higher than that of mesophilic bacteria, reaching 6.0 × 107 CFU·g−1 soil substrate. This count constituted 14.5% of the total number of microorganisms in the tested samples. A similar count was obtained for fungi, reaching 6.3 × 107 CFU·g−1 soil substrate. Yeasts and moulds were the least numerous. Their total count was 3.1 107 CFU·g−1 soil substrate, representing just over 7% of all microorganisms present in the soil substrate. The ratio of total bacteria to fungi, yeasts, and moulds was 3.4:1 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Changes in the number of selected groups of microorganisms in the tested soil substrates.

However, these proportions changed after the introduction of mercury-free spent phytoremediation biomass into the control sample substrate, i.e., the one produced in the control samples. The total number of psychrophilic bacteria decreased significantly to 15.7 × 107 CFU·g−1 soil substrate. This proportion of psychrophilic bacteria in the total microorganisms present in the substrate was no longer 50%, but only 34%. The number of mesophilic bacteria also decreased significantly to 3.3 × 107 CFU·g−1 soil substrate. However, due to the decrease in the numbers of both bacterial groups, the ratio of one to the other did not change significantly and amounted to 4.7:1. However, the number of actinomycetes increased to 16.1 × 107 CFU·g−1 soil substrate. Their number doubled and now subsided to 35% of the total number of microorganisms in the samples. This was most likely due to the introduction of organic matter into the soil, which significantly increased the number of microorganisms capable of decomposing it. These conditions provided very favourable conditions for their reproduction. The total number of fungi, yeasts, and moulds did not change significantly. In the case of fungi, their total number was 7.3 × 107 CFU·g−1 soil substrate, and the total number of yeasts and moulds was 3.4 × 107 CFU·g−1 soil substrate. Their number relative to the total number of microorganisms present in the samples also remained unchanged, at 15% and 7%, respectively. The ratio of total bacteria to fungi, yeasts, and moulds for the soil substrate and spent phytoremediation biomass was 3.3:1 (Figure 4).

The lowest microbial counts were observed for samples containing mercury-containing spent phytoremediation biomass. The total number of psychrophilic bacteria decreased to 2.5 × 107 CFU·g−1 soil substrate, and the total number of mesophilic bacteria to 1.5 × 107 CFU·g−1 soil substrate. This represents an 88% decrease compared to the total number of psychrophilic bacteria in the control sample substrate and an 84% decrease for the reference substrate enriched with mercury-free spent phytoremediation biomass. However, the decreases for the total number of mesophilic bacteria were 69% and 55%, respectively. The ratio of psychrophilic to mesophilic bacteria also changed; their ratio was 1.7:1, almost three times lower. The total number of actinomycetes also changed. The total number of actinomycetes was 9.5 × 107 CFU·g−1 soil substrate. Their numbers increased relative to the control sample substrate, but decreased relative to the total number of actinomycetes in the soil substrate and spent phytoremediation biomass. This represented a 58% increase and a 41% decrease, respectively. Significant reductions were also observed for fungi, yeasts, and moulds. The total number of yeasts and moulds was 1.1 × 107 CFU·g−1 soil substrate, and for fungi, it was 2.5 × 107 CFU·g−1 soil substrate. This represented a 63% and 66% decrease in the total number of yeasts and moulds, respectively, compared to the control sample substrate and the soil substrate with biomass. However, for fungi, these decreases were 61% and 66%, respectively. The ratio of total bacteria to fungi, yeasts, and moulds did not change significantly compared to the previous samples and was 3.7:1. Analysing the percentages of individual microorganism groups studied about the total number of microorganisms, changes were also observed. The percentage of psychrophilic bacteria was 15%, and mesophilic bacteria was 9%. In the case of actinomycetes, their percentage increased significantly to 56%, from 14% and 35% initially. However, the percentages of fungi, yeasts, and moulds of the total number of microorganisms in the samples did not change. For all three soil substrates (standard soil substrate, soil substrate with biomass, and soil substrate with biomass and mercury), the percentages of fungi, yeasts, and moulds were 15% and 7%, respectively (Figure 4).

Statistical analysis using the Kruskal-Wallis test showed statistically significant differences in the numbers of microorganisms between the groups studied. The results of the statistical analysis for changes in the numbers of mesophilic bacteria (H statistic = 8.48; df = 2; p-values = 0.0144), psychrophilic bacteria (H statistic = 8.14; df = 2; p-values = 0.0171), fungi (H statistic = 8.98; df = 2; p-values = 0.0112), yeasts and moulds (H statistic = 9.74; df = 2; p-values = 0.0074) and actinomycetes (H statistic = 9.76; df = 2; p-values = 0.0076) indicated the existence of at least one pair with statistically significant differences. Therefore, the next step was to perform a post-hoc test to identify which groups showed these differences (Table 5). In the case of mesophilic bacteria, fungi, yeasts and moulds, statistically significant differences in their abundance were observed for the soil + biomass/soil + biomass with mercury group. No statistically significant differences were found for the other two groups compared. In the case of psychrophilic bacteria, a statistically significant difference was observed for the soil/soil + biomass with mercury groups. In contrast, for Actinomycetes, statistically significant differences were observed for the soil/soil + biomass groups.

Table 5.

Results of statistical analysis–post-hoc test for the Kruskal–Wallis test.

4. Discussion

Water resources on Earth are not evenly distributed in terms of both quantity and quality. Therefore, in accordance with the sixth (Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all) and fourteenth (Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development), the goal of sustainable development is to protect not only its quantity but also its quality. Sustainable water resource management by removing pollutants at their source will prevent their spread. This will allow for the maintenance of adequate water quality and, thus, the possibility of its use for various purposes related to human activity [32]. Therefore, the use of an environmentally friendly method such as phytoremediation with Salvinia natans to remove mercury from fresh water can also contribute to reducing its amount in seawater, where surface water flows into. However, in order for it to be effective, it is necessary to select the appropriate parameters for the phytoremediation process, such as the appropriate plant species or the maximum concentration of the pollutant to be removed.

The conducted studies confirmed the toxic effects of mercury on aquatic microorganisms. The Microtox test results clearly indicate mercury toxicity even at the lowest concentration used in the study, namely 0.15 mg Hg·L−1. From a concentration of 0.40 mg Hg·L−1, toxicity reached the level of toxicity class V. Such high toxicity significantly alters the metabolic processes of organisms.

However, it should be noted that the Microtox test is conducted using a single cell. This bacterium lacks the mer operon genes (merB, merA, merR, merT, merP, merD, merF, merC, merE, merH, merG), which means its tolerance to mercury in the environment is lower compared to bacteria that do possess this gene [33,34]. This accurately reflects the environmental conditions where the vast majority of aquatic microorganisms do not possess this gene. Although microorganisms with high mercury tolerance, even up to 125 mg Hg·L−1, are present in the aquatic environment, their numbers are low [1]. Studies conducted by Gonzalez-Reguero and colleagues have shown that microbiologically assisted phytoremediation is more effective, and plants achieve greater biomass in mercury-contaminated environments compared to phytoremediation without microbiological assistance [35].

In the case of Salvinia natans plants, toxic effects were also observed as a result of their mercury exposure, even at the lowest concentration used, and as the mercury concentration increased, the plants’ physiological condition deteriorated significantly. Clear changes in leaf colouration, chlorosis, and necrosis were visible without the use of optical instruments. However, these effects were visible after a much longer exposure of the plants to mercury than in the case of the bacteria. The plants were exposed to mercury for 14 days, and despite the significant deterioration in their physiological condition, complete plant death was not observed. This may be the result of the plants’ numerous defence mechanisms against the presence of heavy metals in the substrate.

The presence of heavy metals in the environment causes oxidative stress in plants, which in turn negatively affects cellular homeostasis. This results in changes in plant growth and development [36]. Depending on the amount of toxin in the substrate and the duration of exposure, plants can exhibit various defence responses [37]. The most common mechanism is the reduction of heavy metal uptake by the plant, followed by various detoxification mechanisms if the plant exhibits such metabolic capabilities [38]. One such mechanism is the incorporation of mercury into cell walls. An increase in mercury concentration in the substrate causes an increase in its amount in plant cell walls. This is a plant defence mechanism that immobilises the toxin in the cell wall, preventing the formation of mercury complexes and increasing plant tolerance to this heavy metal [39]. Studies by de Oliveira and colleagues have shown negative changes in the metabolic processes of plants exposed to mercury. These include decreased photosynthetic efficiency and reduced transpiration [39,40]. This may indirectly lead to a deterioration in the physiological condition of plants and increased susceptibility to chlorosis and necrosis. Plants exposed to low mercury concentrations may not exhibit visual signs of chlorosis or necrosis [40], but in the conducted studies, the concentrations were high enough to make these changes visible.

Research conducted by Nurfanifah and Siswanti indicates the effect of mercury on plant enzymatic activity. They investigated changes in the activity of nitrate reductase, which is responsible for plant productivity. Depending on the mercury concentration in the substrate, from 0 to 20 mg Hg·L−1, its activity varies by 9.5–13.5% [41]. The API ZYM test used in the presented study does not allow for the measurement of this enzyme’s activity, as, according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, it is primarily intended for the study of the enzymatic activity of microorganisms. Therefore, its use is justified when using homogenates containing not only plant biological material but also accompanying microorganisms, such as the rhizosphere or epiphytic bacteria. This allows for the study of enzymatic activity not only of plants, within a selected range, but also of the associated microflora in the event of exposure to pollutants.

The API ZYM test performed on plants exposed to mercury did not reveal any changes in their enzymatic activity as a result of contact with the metal. However, this may be due to the test not being sufficiently sensitive for the biological material used. This test is designed for microorganisms and is gaining popularity due to its precision and ease of analysis. Its applicability to other biological materials would enhance the methodology of research on enzymatic activities. Particular attention should be paid to the proper preparation of the test material (sample preparation procedure) and method validation. However, this requires further research with a high degree of analytical detail.

Phytoremediation, like other utilisation methods, is not waste-free. In this case, the waste generated involves large quantities of biomass containing significant amounts of the contaminants removed during the process. These are primarily heavy metals and polycyclic aromatic compounds, the quantities of which and the transformations occurring in the environment must be monitored. This study attempted to identify the potential for sustainable management of mercury-containing biomass after phytoremediation.

The final stage of the research was to assess the potential use of spent phytoremediation biomass for soil substrate preparation. Due to the presence of mercury, it could not be used as a substrate for growing crops intended for human or animal consumption, but other applications could be considered, such as in construction or post-mining land reclamation. Such a substrate must be non-toxic and must not leach from it. Toxicological studies and microbiological analyses were conducted, allowing for a preliminary assessment of the proposed solution. Microtox testing of aqueous extracts from the substrate did not reveal any toxicity, which may indicate that mercury was most likely not released into the solution. Adding spent phytoremediation biomass to garden soil, achieving a final mercury content of 1 mg Hg·kg−1 DM of soil, resulted in significant changes in its microbiome. The total number of mesophilic and psychrophilic bacteria, fungi, yeasts, moulds, and actinomycetes decreased significantly. A comparative analysis of the percentages of individual microorganism groups also revealed significant differences. While psychrophilic bacteria were the most abundant in the mercury-free soil, actinomycetes were the most abundant in the mercury-treated soil. However, these studies require further analysis. Saldarriagi and colleagues demonstrated changes in the microbiome of the plant rhizosphere as a result of mercury exposure. Microorganisms from the Enterobacteriaceae family influence mercury biosorption. Microorganisms improve phytoremediation by increasing plant tolerance to mercury [42]. Actinomycetes have been shown to support the phytoremediation of heavy metals such as Cd, Cu, Pb, and Zn [24]. Studies have shown an increase in the number of actinomycetes in the presence of mercury in the medium, which may suggest their reduced sensitivity to mercury compared to other microorganisms. However, further research is required to verify this hypothesis. These studies should focus on the mechanisms of mercury tolerance. Molecular studies of the mer operon genes are also necessary. Studies conducted on Streptomyces collected from contaminated environments have shown that these bacteria, as a result of environmental pressure, demonstrate the ability to develop adaptive mechanisms. That may result in high tolerance to heavy metals [43]. In mining areas where soil often contains elevated levels of mercury, increased numbers of actinomycetes are observed [44].

The toxicity of mercury-containing soils and their leachates depends largely on their chemical composition and pH, as this influences the bioavailability of mercury and its absorption into living organisms [45,46]. Therefore, when preparing such a substrate, the toxicity of the soil substrate and its aqueous extracts should always be checked.

The increasing amount of mercury in the environment necessitates increasing the effectiveness of phytoremediation processes. That requires increasing knowledge in this area. The conducted research confirms the toxicity of mercury and the changes in the soil microbiome caused by its presence. It also indicates the possibility of using Salvinia natans as a plant capable of conducting phytoremediation at concentrations no greater than 0.30 mg Hg·L−1.

Mercury, as an element recognised as a hazardous, toxic, and persistent environmental pollutant according to the United Nations Environment Programme, should be continuously monitored in the environment [1]. It is not only its quantities that are important, but above all, its chemical form and the environmental component in which it is found. This has a significant impact due to the potential for its transformation through biological, biochemical, and chemical transformations. Mercury is used in many industries, and despite efforts to limit its release into the environment, its amount is unfortunately constantly increasing, although not at the same rate as in previous years [34,47]. Therefore, research related to assessing its impact on various organisms, including in the context of biodiversity conservation, is extremely important. Expanding knowledge in this area also allows for the determination of threshold concentrations for individual organisms, above which they begin to die. This is important in the context of its potential use for phytoremediation and remediation.

5. Conclusions

- The acute toxicity test (Microtox) showed strong mercury toxicity already at a concentration of 0.15 mg Hg·L−1, and at a concentration of 0.30 mg Hg·L−1 it was classified as a ‘severe toxic hazard’ according to the manufacturer’s criteria.

- Salvinia natans tolerates mercury concentrations up to 0.30 mg Hg·L−1. Changes in the form of chlorosis and necrosis were observed, indicating a deterioration in their physiological condition, but no total mortality was found.

- Enzymatic activity tests using the API ZYM test did not show any significant changes as a result of mercury exposure.

- The use of phytoremediation biomass as a soil additive, while maintaining a final concentration not exceeding 1 mg Hg·kg−1 DM of soil, affects changes in the number of microorganisms, with a predominance of actinomycetes. At the same time, aqueous extracts from such utilised biomass containing mercury did not show acute toxicity (Microtox test).

- The results obtained regarding changes in the abundance of microorganisms in the soil after the addition of biomass with mercury highlight the need for further research on the safe management of biomass and the role of soil microorganisms.

- Further research integrating plant–microbe interactions and mercury speciation analyses could improve the safety and efficiency of phytoremediation technologies

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and W.F.; methodology, M.S. and W.F.; investigation, M.S. and W.F.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was conducted under the grant MNiSW No. N N523 612139 entitled “Evaluation of the effectiveness of phytoremediation of water contaminated with mercury(II) by pleustophytes in Lower Silesia”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the final report on the funding granted. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Teodora Traczewska for valuable discussions and assistance in carrying out the research.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Wiktoria Filarowska was employed by the company US Pharmacia Sp. z o.o. The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PE | Percentage effect |

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials |

| DM | dry weight |

| CFU | colony-forming unit |

References

- Adewuyi, A. Biogeochemical dynamics and sustainable remediation of mercury in West African water systems. Chemosphere 2025, 379, 144436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, E.A.; da Silva, L.C.; Battirola, L.D.; de Andrade, R.L.T. Tridax procumbens: Applicable weed in phytoremediation and bioindication of soil contamination by mercury. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 27515–27524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Soares, C.; Santos Lopes, V.J.; de Freitas, F.; Córdova, M.O.; Cavalheiro, L.; Battirola, L.D.; de Andrade, R.L.T. Characterizing pioneer plants for phytoremediation of mercury–contaminated urban soils. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 10129–10144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Agarwal, R.; Kumar, K.; Kumar Chayal, N.; Kumar, G.; Kumar, R.; Ali, M.; Asivastava, A.; Aryal, S.; Pandey, T.; et al. Mercury poisoing in women and infants inhabiting the Gangetic plants of Bihar: Risk assessment. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, S.; Vashishth, R.; Mukherjee, A.G.; Gopalakrishnan, A.V.; Sabina, E.P. Mercury in the environment: Biogeochemical transformation, ecological impacts, human risks, and remediation strategies. Chemosphere 2025, 381, 144471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Li, R.; Wang, C.; Yang, S.; Shao, M.; Zhang, L.; Li, P.; Feng, X. Transport and transformation of colloidal and particulate mercury in contaminated watershed. Water Res. 2025, 278, 123428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Luo, W.; Cheng, Z.; Mou, G.; Wu, X.; Liu, H. Health risk of mercury and cadmium and their migrations in a soil-maize system of the karst mining area. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 236, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søndergaard, J.; Elberling, B.; Sonne, C.; Larsen, M.M.; Dietz, R. Stable isotopes unveil ocean transport of legacy mercury into Arctic food webs. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, X.; Sun, J.; Xiang, Y.; Su, H.; Huang, H.; Gu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jordan, R.W.; Jiang, S. Centennial-scale evolution, source apportionment, and ecological risks of heavy metals in Daya Bay, South China Sea. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 382, 126768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Li, Z.; Ding, D.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Q.; Sui, Q.; Sun, Q.; Cui, Z. Ecological risk assessment of heavy metals in seawater and sediment as in Jinghai Bay: Evidence for ecosystem degradation in a coastal bay of the Yellow Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 219, 118256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Chen, G.; Yang, R.; Bai, C.; Yang, W.; Zhang, J.; Yin, X.; Yang, F.; Seth, C.S.; Liu, H. Concentration-dependent interactive toxicity of cadmium and mercury: Non-negligible effect on phytoremediation by indigenous Artemisia lavandulaefolia. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 291, 117803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobbinah, R.T.; Boadi, N.O.; Saah, S.A.; Agorku, E.S.; Badu, M.; Kortei, N.K. Cancer risk from heavy metal contamination in fish and implications for public health. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiongyi, M.; Xueqin, W.; Yupei, H.; Xiqian, Z.; Xiaohua, Z. The sources of bioavailable toxic metals in sediments regulated their aggregated form, environmental responses and health risk-a case study on Liujiang River Basic, China. Water Res. 2025, 278, 123369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, J.P.; Tessier, E.; Le Faucheur, S.; Amouroux, D.; Slaveykova, V.I. Comparative analysis of species-specific dissolved gaseous mercury oxidation in phytoplankton cultures. Environ. Res. 2025, 279, 121764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanwel, S.; Gulzar, F.; Alofaysan, H.; Tanriverdiyev, S.; Jing, H. Toxic metal pollution in freshwater ecosystems: A systematic review of assessment methods using environmental and statistical indices. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 218, 118028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulin, B.A.; Tate, M.T.; Janssen, S.E.; Aiken, G.R.; Krabbenhoft, D.P. A comprehensive sulfate and DOM framework to assess methylmercury formation and risk in subtropical wetlands. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, M.; Guo, F.; Zhong, H.; Yin, Y. Making waves: Exploring scenarios of abiotic mercury methylation in nature. Water Res. 2025, 286, 124239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.M.; Elshebrawy, H.A.; Sallam, K.I. Health risk assessment of heavy metals—contaminated marine fish from the Mediterranean Sea at Damietta city coast, Egypt. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 220, 118426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.L.; Quek, Y.Y.; Lim, S.; Shuit, S.H. Review on phytoremediation potential of floating aquatic plants for heavy metals: A promising approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gałka, A.; Szmeja, J. Phenology of the aquatic fern Salvinia natans (L.) All. in the Vistula Delta in the context of climate warming. Limnologica 2013, 43, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, R.; Nam, S.-H.; An, Y.-J. Salvinia natans: A potential test species for ecotoxicity testing. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 267, 115650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbagory, M.; Kumar, P.; Shalaby, M.; El-Nahrawy, S.; Omara, A.E.; Goala, M.; Arya, A.K.; Bachheti, R.K.; Andabaka, Ž.; Širić, I. Heavy metal accumulation potential of Salvinia natans [(L.) All.] in selected freshwater lakes fed by Jhelum River in North India. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 236, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alp-Turgut, F.N.; Yildiztugay, E.; Ozfidan-Konakci, C.; Tarhan, I.; Öner, M.; Gulenturk, C. Evaluation of the phytotoxicity and accumulation potential of nitro-polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon, 3-nitrofluoranthene, on water status, photosystem II efficiency, antioxidant activity and ROS accumulation in Salvinia natans. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeyasundar, P.G.S.A.; Ali, A.; Azeem, M.; Li, Y.; Guo, D.; Sikdar, A.; Abdelrahman, H.; Kwon, E.; Antoniadis, V.; Mani, V.M.; et al. Green remediation of toxic metals contaminated mining soil using bacterial consortium and Brassica juncea. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 277, 116789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohmanna, A.N.; Agustina, L.; Saputra, R.A.; Sari, N.; Noor, I.; Majid, Z.A.N.M. Enhancing phytoremediation of heavy metals: A comprehensive review of performance microorganism-assisted Cyprerus rotundus L. J. Ecol. Eng. 2025, 26, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anirudhan, T.S.; Shainy, F. Effective removal of mercury (II) ions from chlor-alkali industrial wastewater using 2-mercaptobenzamide modified itaconic acid-grafted-magnetite nanocellulose composite. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 456, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, B.; Liu, F.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; Bu, Y. Evaluation and source apportionment of heavy metals (HMs) in sewage sludge of municipal wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) in Shanxi, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 15807–15818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, M.J.; Yang, Y.M.; Oh, D.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Yoon, Y.Y. Spatial distribution of heavy metal accumulation in the sediments after dam construction. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, M.; Etxebarria, J.; De las Fuentes, L. Evaluation of wastewater toxicity: Comparative study between Microtox® and activated sludge oxygen uptake inhibition. Water Res. 2002, 36, 919–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, G.; Sarker, S. The role of Salvinia rotundifolia in scavenging aquatic Pb (II) pollution: A case study. Bioprocess Eng. 1997, 17, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoagland, D.R.; Arnold, D.J. The Water Culture Method of Growing Plants Without Soil. Calif. Agric. Exp. Stn. 1950, 347, 1–32. Available online: https://archive.org/details/watercultureme3450hoag/mode/2up (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- United Nations. General Assembly Resolution A/RES/70/1. Transforming Our World, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Naguib, M.M.; El-Gendy, A.O.; Khairalla, A.S. Microbial diversity of Mer operon genes and their potential roles in mercury bioremediation and resistance. Open Biotechnol. J. 2018, 12, 56–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshanee, M.; Chatterjee, S.; Rath, S.; Dash, H.R.; Das, S. Cellular and genetic mechanism of bacterial mercury resistance and their role on biogeochemistry and bioremediation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 126985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Reguero, D.; Robas-Mora, M.; Alonso, M.R.; Fernández-Pastrana, V.M.; Lobo, A.P.; Gómez, P.A.J. Induction of phytoextraction, phytoprotection and growth promotion activities in Lupinus albus under mercury abiotic stress conditions by Peribacillus frigoritolerans subsp., mercuritolerans subsp. nov. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 285, 117139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Xiong, B.; Huong, X.; Sun, X.; Du, H.; Ma, M. Liquiritin and L-Dopa mitigate gaseous elemental mercury toxicity in Tillandsia usneoides: Insights into metabolic reprogramming and phytoremediation potential. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 496, 139237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Oliphant, K.D.; Xia, Z.; Chen, Z.; Hou, R.; Zhang, R.; Peng, T.; Hänsch, R.; Wang, D.; Rennenberg, H.; et al. Rhizobial symbiosis modulates mercury accumulation and metabolic adaptation under hydrological extremes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 495, 139141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kour, D.; Sharma, B.; Negi, R.; Kumar, S.; Kaur, S.; Kaur, T.; Khan, S.S.; Kour, H.; Ramniwas, S.; Rustegi, S.; et al. Microbial amelioration of heavy metal toxicity in plants for agro-environmental sustainability. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Bing, H.; Yuan, W.; Yang, R.; Wang, X. Quantifying post-dam anthropogenic mercury accumulation in tree gorges reservoir sediments using mercury isotopic signatures. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 494, 138773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, E.A.; Borella, D.R.; Santos Lopes, V.J.; Battirola, L.D.; de Andrade, R.L.T.; da Silva, A.C. Physiological effects of mercury on Handroanthus impetiginosus (Ipe Roxo) plants. Agronomy 2025, 15, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurhanifah, T.; Siswanti, D.U. Effect of mercury dose variation on growth and nitrate reductase activity in Aquarius palifolius (Nees & Mart.) Christenh. & Byng. Makara J. Sci. 2025, 29, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldarriaga, J.F.; Lòpez, J.E.; Díaz-García, L.; Montoya-Ruiz, C. Changes in Lolium perenne L. rhizosphere microbiome during phytoremediation of Cd- and HG- contaminated soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 49498–49511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorková, Z.; Cimermanová, M.; Piknová, M.; Adhvaryu, S.; Pristaš, P.; Kisková, J. Environmental impact on the genome shaping of putative new Streptomyces species. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, D.; Robas, M.; Fernández, V.; Bárcena, M.; Probanza, A.; Jiménez, P.A. Comparative metagenomic study of Rhizospheric and bulk mercury-contaminated soils in the mining district of Almadén. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 797444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiafe, S.; Boahen, C.; Bandoh, T. Enhanced phytoremediation of heavy metals by soil-applied organics and inorganic amendments: Heavy metal phytoavailability, accumulation, and metal recovery. Soil Sediment Contam. Int. J. 2025, 34, 634–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zheng, H.; Chen, Q.; Fei, J.; Sun, H.; Ding, Z. Unraveling the pathways of heavy metal accumulation in rice: Role of roots, stems, and soil pH. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 302, 118664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.Y.; Hsu, C.C.; Lin, C.L.; Lu, M.L.; Chiang, H.L.; Chang, M.B. Mercury flows in a cement plant adopting circular economy policies. Waste Manag. 2025, 202, 114808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).