Abstract

Amidst the threat of increasingly extreme weather, climate change risks greatly influence firms’ decision-making. Gathering information from China’s listed enterprises from 2011 to 2023, we investigate the impact of climate risk perception (CRP) on the quantity and quality of firms’ green innovation (Q&Q). The results show that CRP promotes both Q&Q, and the promoting effect on quantity is more significant. Impact channel tests show that an encouraging impact on Q&Q is mainly achieved by increasing the number of executives with environmental backgrounds and promoting green investment. In addition, the level of external digital integration and executives’ international management experience can positively enhance the role of CRP on Q&Q. Furthermore, the promoting effect of CRP is more evident in polluting and high-tech enterprises. This study presents new empirical evidence to convey the risk signals of climate transition and transform enterprises’ risk perception into green innovation momentum.

1. Introduction

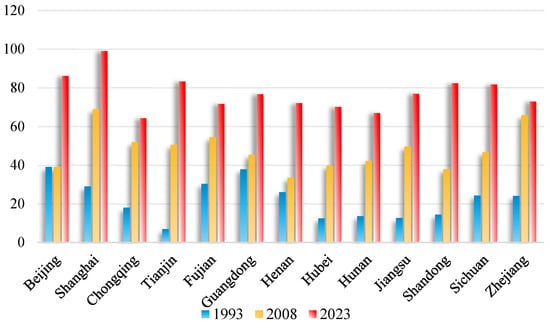

With the continuous escalation of global warming, climate change has become a major long-term global risk, significantly increasing the frequency and severity of disasters, posing a serious threat to economic and social activities [1,2]. The frequency of extreme heat events in China has increased significantly since the 20th century. Figure 1 shows the number of extreme hot days in China’s municipalities directly under the central government and the top 10 cities by GDP. Since 1993, extreme weather events in these economic centers have become increasingly intense, posing a potential risk to social development. Therefore, it is urgently necessary to enhance climate adaptability and environmental governance comprehensively. Green innovation (GI) is essential to create sustainable momentum [3]. It provides crucial support for enterprises to effectively cope with climate change fluctuations [4]. By using green technologies, enterprises can significantly reduce pollutant emissions and environmental risks. Therefore, research on strategies for improving the quantity and quality of enterprises’ green innovation (Q&Q) should be given attention.

Figure 1.

The extremely hot days in some developed cities in China.

Existing studies have extensively researched the factors influencing enterprises’ Q&Q. Although there are still apparent controversies, these influencing factors involve both firms’ internal and external aspects, including not only internal elements such as the firm’s management strategy [5] and corporate culture [6] but also external aspects such as the market environment [7] and social expectations [8]. Although existing studies have provided in-depth analyses of the impact factors of corporate green innovation, in the context of increasing extreme climate risks, limited research has explored the role of climate risk perception (CRP) on firms’ green innovation, particularly in relation to intrinsic motivation. Unlike climate risk exposure (where enterprises objectively face climate events) and climate risk response (a series of direct measures taken by enterprises to address climate risks in the short term), climate risk perception refers to the subjective understanding, interpretation, and degree of attention that management attaches to these risks. It is more likely to have an impact on enterprises from the perspectives of decision-making and long-term interests.

According to prospect theory, the psychological impact of losses is usually twice that of the impact of the same-value gains. This loss aversion enables enterprises to respond more quickly and intensely when facing climate risks—whether it is potential environmental damage or sudden policy tightening—and even invest excess resources to avoid possible losses. In fact, when enterprises become aware of the risks associated with climate uncertainty, they are likely to take measures to prevent potential losses and stimulate a range of green behaviours, such as reducing pollution emissions, increasing environmental governance costs, and actively disclosing ecological conditions [9,10]. Specifically, CRP may first encourage firms to hire more managers with environmental backgrounds, who may be more inclined to engage in ecological behaviors. Second, CRP may allow firms to make preventive green investments, promote environmental restoration, and reduce pollution emissions to mitigate possible climate risk events. Third, the response of different firms to climate change shocks varies according to their exposure to climate risk and their perceptions of the environment [11]. Therefore, only by incorporating CRP into the analytical framework can heterogeneous leaps in the Q&Q be accurately identified.

Therefore, we collect the companies listed in dataset from the past decade to investigate how firms’ climate risk perception impacts the Q&Q. Specifically, we adopt a two-way fixed effects panel model to examine the relationship of CRP and Q&Q. We adopt the mediating effect model to examine the mechanism channels, including the effect of the proportion of executives with environmental backgrounds, and green investment. Furthermore, the model provides evidence of moderating effects of external digital integration and executives’ internal experience in overseas management. In addition, group regressions are employed according to the degree of pollution and technological characteristics to test heterogeneous effects.

This study provides three potential contributions: First, we innovatively construct a firm-level CRP index by combining textual analysis and machine learning. The existing literature rarely considers that Chinese enterprises face climate change when constructing alternatives to mitigate climate risks. Therefore, this study utilizes the Word2Vec model to expand the climate risk vocabulary to a Chinese context, thereby building the CRP index for listed enterprises. Second, we add to the literature by exploring the effect of improvement of Q&Q from a climate risk perspective. Most scholars tend to explore green innovation from the viewpoint of external policies [12], internal enterprise resources [13], and management [14]; few studies have considered the dual effects of CPR on the Q&Q. Third, this paper takes the Porter hypothesis as the entry point to explore the innovation compensation effect, further expanding the mechanism of corporate green innovation. Most of the existing literature examines policies or corporate finance [15,16], but has not yet focused on the potential mediating role of the environmental background of senior executives and green investment. Furthermore, this paper examines the moderating effects of internal digital integration and senior executives’ external experience in overseas management.

2. Literature Review

Existing research primarily focuses on the economic impact of climate change at both the macro and micro levels. At the macro level, the effects of climate change on national finance and the economy are very significant, including on the return rate of stocks in the same period [17], stock price volatility [15], bond price volatility [16], green index volatility [18], and energy market risk transmission [19]. For example, Mukherjee and Ouattara (2021) argue that the impact of temperature could lead to market inflation [20]. Shang et al. (2022) propose that climate policy uncertainty has reduced demand for traditional energy sources in the US energy market [21]. These studies highlight the macroeconomic impact of climate change risk and provide profound insights into the interaction between the two.

At the micro level, climate change risk, as an external variable beyond the control of firms [22], has important implications for firm operations and decision-making, for example, cash requirements [23], capital debt structure [24], optimization and reform of firms’ production network [25], cross-regional investment risk decisions [26], daily operational cost control [27], and green innovation [28]. Moreover, the effects include both positive and negative effects. For example, Li and Zhang [24] believe that firms could reduce financial leverage in the face of climate uncertainty. Gong et al. [29] argued that a firm’s exposure to climate change is positively correlated with return volatility. In summary, assessing climate change risk at the micro level is complex, posing financial and operational challenges and potential growth opportunities for firms.

Meanwhile, some scholars mainly explore the factors influencing the Q&Q from internal and external aspects. The internal factors include corporate environmental responsibility [30], digital transformation [31], ESG performance [32], and management turnover [33]. External factors include environmental legislation [34], carbon trading policies [35], green finance policies [7,36], the digital economy [37], and other relevant factors. For example, Song et al. [37] propose that the digital economy can enhance the quantity and quality of green innovation. Although the existing literature about green innovation is quite rich, few scholars have analyzed issues related to corporate green innovation from the perspective of firms’ CRP.

To summarize, three research gaps remain that require further exploration. First, exploration of the micro-effects of climate risks has primarily been limited to the financial and operational dimensions. Few studies have examined the impact of climate risks on green innovation, a key strategic asset. Second, the internal mechanism of how CRP drives the quantitative expansion and qualitative leapgrowth of green innovation remains a black box. Third, potential transmission paths, from climate risk perception and executive environmental background to preventive green investment, have not yet been systematically identified and tested, and urgently require supplementation and expansion.

3. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

As Schumpeter proposed initially in the theory of innovation, enterprise innovation constitutes a creative response to market disequilibrium. When firms recognize the physical and transitional risks associated with climate change, such awareness disrupts existing technological equilibria and prompts the reallocation of resources toward green technologies [38]. First, risk perception lowers the threshold for adopting green technologies and accelerates the development and diffusion of clean technologies [39]. At the strategic level, the recognition of both physical and transition risks motivates firms to adjust their technological trajectories and increase investment in environmentally sustainable innovations. From the perspectives of talent acquisition and capital allocation, perceived risks signal emerging opportunities. This awareness encourages enterprises to attract personnel with expertise in green technologies and to increase the share of investments dedicated to environmental initiatives, thereby establishing a foundation for long-term sustainability [40].

Second, drawing on the theory of path dependence, firms may develop entrenched reliance on polluting technologies due to historical experience; however, heightened risk perception can mitigate this inertia, enabling a shift toward cleaner alternatives and fostering sustainable development [41]. Under pressure from environmental regulations, firms face long-term financial penalties for continuing to use traditional, high-emission technologies. They are incentivized to restructure internal production processes, reduce their dependence on carbon-intensive products, and develop low-carbon product lines, thereby generating sustained demand for green innovation [42].

Third, grounded in the theory of innovation ecosystems, CRP can reshape corporate innovation frameworks. With forward-looking strategic planning, increased awareness of climate risks leads firms to place greater emphasis on external collaboration and knowledge exchange during the innovation process. Consequently, firms are more likely to form strategic alliances with universities and research institutions specializing in green technologies. This open innovation model enhances both the speed and quality of innovation output [43], allowing firms to accelerate the advancement of green technologies. Therefore, only by integrating CRP into long-term strategic planning—rather than by treating it as a short-term compliance obligation—can firms achieve sustained, high-quality green innovation. Therefore, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 1:

The CRP can boost green innovation, and quantity promotion is more obvious.

According to Porter’s hypothesis, green innovation initiatives undertaken by enterprises can generate compensatory advantages, encompassing both product and process improvements. Product-related benefits arise as corporate innovation and the development of environmentally products enhance a firm’s reputation and market competitiveness. Process-related gains stem from reductions in per-unit production costs and improved economic performance. At the strategic level, companies increasingly prioritise the recruitment and advancement of executives with environmental expertise, who leverage their specialized knowledge to manage environmental risks and crises effectively [44]. The environmental competence of senior management not only enhances organizational capacity to understand and respond to climate transition risks but also guides the realignment of strategic priorities, reinforcing green innovation as a source of long-term competitive advantage [45]. Such executives’ long-term orientation facilitates the formulation of sustainable development strategies, reduces dependence on traditional, high-pollution technologies, and promotes sustained investment in green innovation, thereby enhancing green innovation performance [46].

At the financial level, escalating climate volatility drives firms to allocate greater resources toward green technologies and sustainable production. This shift represents not merely incremental capital adjustment but a fundamental realignment of corporate strategic focus. Green investments meet the necessary conditions and capital requirements to foster green innovation [47]. Consequently, enterprises treat green investment as a core strategic response, systematically channeling funds into areas such as renewable energy adoption, energy efficiency enhancement, and pollution control. These investments modernize production infrastructure and, more importantly, cultivate a robust and sustainable green R&D capability. For example, clean energy installations provide platforms for testing emerging technologies, energy-saving equipment upgrades foster innovations in complementary processes, and investments in environmental governance catalyze breakthroughs in circular economy technologies. The resulting knowledge accumulation enables firms to transition from passive regulatory compliance to proactive innovation. Over time, this leads to significant advancements in green technology patents and eco-friendly product development, culminating in a strategic evolution from risk adaptation to innovation leadership [48]. Therefore, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 2:

The CRP can enhance Q&Q by leveraging executives with corporate environmental backgrounds and green investment expertise.

The digital integration of external and international management experience of internal executives can contribute to the role of CRP in driving green innovation. From the perspective of external digitalization, first, the systematic application and integration of digital technologies can enhance enterprises’ identification accuracy and response speed of climate risks and transform ambiguous climate threats into specific emission reduction and innovation demands, which improve the pertinence of GI [49]; second, digital integration enhances operational efficiency and frees up more research and development (R&D) resources, enabling enterprises to increase the Q&Q.

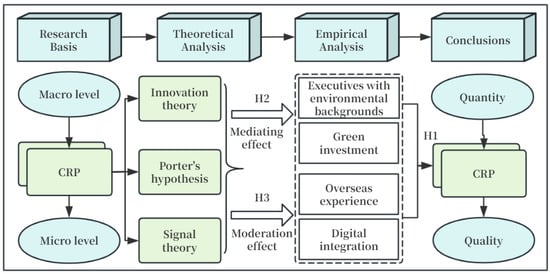

From the perspective of internal executives, those with overseas management experience are more familiar with international climate governance practices and can make systematic, innovative decisions by keenly transforming CRP [26]. This global perspective prompts enterprises to prioritize the layout of technologies with international compatibility when pursuing patents, rather than simply complying with environmental regulations. Additionally, the cognitive flexibility gained from overseas experience can help mitigate the tendency toward defensive innovation. The signal theory suggests that the overseas experience of senior executives, as a reliable signal of capability, can not only effectively attract the attention of domestic and foreign investors and partners [50] but also help enterprises obtain better opportunities for green technology cooperation. In conclusion, the primary structure of this paper is depicted in Figure 2. Therefore, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 3:

The internal executives’ overseas management experience and external digital integration positively strengthen the role of CRP on Q&Q.

Figure 2.

The research framework.

4. Method Design

4.1. Econometric Model

We employ a panel model with two-way fixed effects to investigate whether climate risk perception (CRP) affects the quantity and quality of firms’ green innovations (Q&Q).

In the above formula, is the explained variable, is the core explanatory variable and contains quantity and quality, is other control variables, and i and t represent the firm and year. is the individual fixed effect and is the time fixed effects. is the disturbance term.

Referring to Gao et al. [51], we construct the mediating effects model as Equations (2) and (3):

where the other variables are the same as in Equation (1), and is the mediating variable.

Referring to Xie and Teo [52], we utilize the moderation effect model to verify the role of digital integration and overseas management experience in Equation (4):

where is the moderating variable, and is the interaction term of the explanatory variable and the moderating variable.

4.2. Variable

4.2.1. Dependent Variable

This paper utilizes enterprise green patents to measure corporate green innovation, encompassing three categories: inventions, utility models, and designs. Among them, invention patents must pass a strict dual examination of novelty and practicality, which best represents technological breakthroughs. The threshold for utility models and designs is relatively loose, reflecting gradual improvement. To scientifically distinguish between “Quantity” and “Quality”, we follow the approach of Chang & Zhao [35], measuring quantity by the total number of green patent authorizations and measuring quality by the number of green invention patents with the highest technological content.

4.2.2. Explanatory Variable

Drawing on the index construction of Nagar & Schoenfeld [53] and Sun et al. [26], we took the China Meteorological Disaster Yearbook, the authoritative bulletin of the National Meteorological Administration, and the English dictionary of Nagar & Schoenfeld [53] as the original corpus. We extracted seed keywords highly relevant to enterprises’ perception of climate risk. Subsequently, Word2Vec was adopted with deep semantic matching technology to expand the context and cluster synonyms of the seed words, forming a bilingual word bank that combined policy contexts and disaster contexts. Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) weights and the annual inverse document frequency correction were introduced to calculate the disclosure frequency of each term in the annual reports and interim announcements of listed companies, and a Chinese-context CRP index was synthesised. The specific construction steps were as follows:

Step 1: Referring to Yin et al. [54], we download and organize the annual reports disclosed by enterprises in bulk through “Juchao Information Network” (www.cninfo.com.cn).

Step 2: Using the China Meteorological Disaster Yearbook as a guide, we analyze text information related to climate risk, combining it with details revealed by the government website [55]. Specifically, we construct an enterprise climate risk perception measurement framework based on the four aspects of “Climate-Physical-Regulatory-Opportunity”, and solicit opinions from relevant experts through interviews to further adjust and improve the framework, obtaining a total of 149 related phrases: Group 1 pertains to climate risk awareness, such as “air pollution”, “air quality”, etc., aiming to explore enterprises’ initial perception of the current environmental pollution situation. Group 2 focuses on climate risk identification, such as “typhoons” and “heavy snow”, aiming to explore enterprise standards for identifying climate risks. Group 3 relates to environmental governance, such as “carbon bonds”, “carbon sequestration”, etc., aiming to explore a series of enterprises’ reactions after identifying climate risks. Group 4 is a risk and opportunity category, such as “tidal energy” and “geothermal energy”, aiming to explore enterprises’ expectations for the future under climate risks. In this study, the complete measurement framework is placed in Appendix A, Table A1. This transparency is crucial for verifying the content validity of the firm-level CRP index.

Step 3: Based on the Word2Vec model of Mikolov et al. [56], the semantic expansion of the seed word library is carried out by using machine learning methods. The TF-IDF weight and the correction of the annual inverse document frequency are introduced to eliminate the interference of high-frequency common words. We build a bilingual extended word bank that integrates “policy contexts” (such as national strategies and emission reduction plans) with “disaster contexts” (such as extreme weather and disaster losses). Ultimately, 149 seed words associated with CRP are generated, providing a corpus on which to base the subsequent index calculation.

Step 4: Take the ratio of the total word frequency of the climate risk extended word set in the annual report to the total word frequency as the base value to construct the enterprise’s annual CRP index. To mitigate the short-term disclosure impulse of firms’ management and maintain a long-term risk perception trend, we calculated a three-year rolling average of this proportion to obtain the final CRP index.

4.2.3. Control Variables

Referring to Barko et al. [57], this paper excludes other factors affecting firms’ green innovation. Return on assets (ROA), enterprise size (Size), Tobin value (Tobq), operating margin (Opr), intangible asset ratio (Isr), and asset-liability ratio (Lev) are used as control variables. A reasonable introduction of control variables can effectively enhance the robustness of the research results. The calculation methods for each indicator are in Table 1:

Table 1.

The calculation of control variables.

4.2.4. Mediating Variables

Environmental background executives (Ebe): Referring to Li et al. [58], we adopt the text analysis method to determine the number of executives with an environmental background by searching for annual reports related to the environment in the resumes of senior executives. Among the senior management personnel of enterprises, those with an environmental protection background included individuals who had participated in environmental protection projects, obtained environmental protection degrees, or patented environmental technologies.

Green investment (Gin): Referring to Cui et al. [59], expenditures related to pollution prevention, ecological environment governance, and green production listed in firms’ ongoing projects are regarded as green investments. Specifically, we compare the project names, budget items, and contract texts one by one, add up the capital expenditures directly related to sewage treatment, ultra-low greenhouse gas emissions to the atmosphere, clean energy substitution, resource recycling, and green certification, and exclude the expenditures for simple capacity expansion to accurately capture real capital movement of enterprises towards green transformation.

4.2.5. Moderation Variables

Digital integration (DI): We count the word frequency related to digitalization in the annual reports of listed enterprises to represent the digital integration level, referring to Wu et al. [60]. Specifically, the level of enterprises’ DI is divided into five dimensions, “artificial intelligence technology”, “big data technology”, “cloud computing technology”, “blockchain technology”, and “digital technology application”, and a total of 76 digital-related word frequencies are calculated, which are used as the measurement index to measure enterprise digital level.

Executives’ overseas experience (Os): There are two methods to measure executives’ overseas management experience. One approach is to construct dummy variables to measure whether senior executives have overseas management experience within the enterprise; the other is to measure the proportion of executives with such experience. The former is more convenient, but the representation cannot reflect the impact. Therefore, regarding Zheng et al. [61], we adopt the latter measurement method to construct proxy indicators of senior executives’ overseas management experience.

4.3. Data

We select information on China’s A-share listed companies from 2011 to 2023, and all the data are from the sample companies’ annual reports and the China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database (CSMAR). The special treatment (ST) and particular transfer (PT) firms with serious information missing are scaled by 1% across all study variables, aiming to mitigate any potential bias from extreme values on the estimated results. We process the data logarithmically to prevent significant data gaps from affecting the results. The final sample covers 4723 listed companies with 35,262 observations.

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics of the main variables. The output of green innovation is divided into quantity and quality. The sample enterprises apply for an average of 0.611 green patents per year, but the median is 0, indicating that about half of the enterprises have not carried out any green innovation. The mean value of the quality dimension is even lower, at only 0.222, and the standard deviation is 0.523, indicating that the proportion of high-quality green patents is generally low, with a highly skewed distribution to the right. The average and maximum CRP values can reflect significant differences in carbon reduction intensity among different enterprises.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

Regarding control variables, the average company Size is 2.217, and the average Tobq is 1.918, indicating that the market has a reasonable expectation for future growth, but the extreme values vary greatly. The average ROA of the profit indicator is 4.1%, the median is 3.9%, and the lowest loss is −25.2%. The Lev is 41.6%, with a maximum of 94%. Some enterprises are under considerable debt repayment pressure. The Opr and Isr also show a relatively large degree of dispersion, providing sufficient sources of variation for subsequent regression.

Table 3 presents the Pearson correlation and multicollinearity test results for the main variables. It can be seen that the correlation coefficients between green innovation and CRP are both significant at the 1% level, initially indicating a positive association. Regarding control variables, the correlation coefficients of indicators such as enterprise scale, asset–liability ratio, profitability, and natural property rights with green innovation and CRP are all lower than 0.5, indicating no signs of high collinearity. Further variance inflation factor tests revealed that the variance inflation factor (VIF) values of all variables are far below the warning threshold of 10, preliminarily confirming that the model does not exhibit significant multicollinearity and that the regression results are reliable.

Table 3.

Correlation and multicollinearity test.

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Benchmark Regression and Result Analysis

Table 4 presents the results of benchmark regression. Columns (1) and (3) are reported as results without control variables; control variables are added in columns (2) and (4) and control for both individual and time effects. In general, the coefficients of CRP in columns (1)–(4) are all positive and significant, indicating that CRP can boost green innovation both in quality and quantity, and this conclusion verifies Hypothesis 1. In addition, the coefficients in the first two columns are significantly larger than those in the last two columns, which suggests that CRP promotes quantity more than quality.

Table 4.

Benchmark regression.

One possible explanation is that when enterprises perceive climate risks, they prioritize meeting regulatory requirements or market expectations by rapidly increasing the number of green patents rather than pursuing technological breakthroughs [62]. Since high-quality green innovations, such as breakthrough emission reduction technologies, typically require long-term R&D investment and high failure risks [63], enterprises tend to opt for incremental innovations with lower risks and faster results when faced with policy pressure or market uncertainties. This defensive innovation strategy focuses more on short-term compliance. It demonstrates the enterprise’s response to climate policies by rapidly launching many low-threshold green patents [9], quickly obtaining benefits such as subsidies. Especially in cases of clear policy signals, enterprises must rapidly accumulate patents to convey compliance signals and respond to regulatory assessments or investor attention [64]. However, although this quantity-oriented innovation model can meet external demands in the short term, it may not truly enhance the enterprises’ competitiveness in green technology.

5.2. Robustness Test

5.2.1. Replacing Q&Q Measurement

To ensure the robustness of the baseline conclusion, this paper draws on Zhang et al. [45] and replaces the “authorized quantity” of green patents with the “application quantity” to remeasure the Q&Q. Specifically, we measure the quantity by the number of green invention patent applications independently submitted by enterprises and the quality by the ratio of the number of green invention patent applications to the total number of green patent applications, thereby alleviating the measurement errors caused by delay in authorization and the uncertainty of examination. Columns (1) and (2) of Table 5 report the regression results after replacing the explanatory variables; the coefficient direction, significance, and economic significance of CRP are highly consistent with the benchmark results in Table 4, indicating that the promoting effect of CRP on the Q&Q does not rely on specific patent statistical standards. This conclusion is robust and reliable.

Table 5.

Replacing the Q&Q measurement and Tobit model.

5.2.2. Replacing the Tobit Model

This paper further adopts an alternative metrological approach for robustness testing. Given that both the Q&Q are truncated to zero and showed a significant right bias, we refer to Shuai et al. [65] and re-estimated using the Tobit model instead of the benchmark Ordinary Least Squares (OLS). The results in columns (3) and (4) of Table 5 show that, regardless of whether the left endpoint is zero or the double-ended truncation setting is adopted, the marginal effect of the CRP is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that the conclusion is not affected by the differences in model settings and remains robust.

5.2.3. Excluding Special Samples

Given municipalities’ political and economic particularities, which are directly under the central government, they are more likely to receive state support and become pilot cities for various environmental policies. Moreover, due to their more complete infrastructure, local enterprises may be less affected by the climate. Therefore, this paper excluded samples from four municipalities directly under the central government for testing. Table 6’s columns (1) and (2) show that the conclusion remains robust after excluding the samples of four municipalities.

Table 6.

Excluding special samples and replacing the GMM model.

5.2.4. Replacing the Empirical Model

Referring to Khattak et al. [66], this paper adopts the generalized method of moment (GMM) to make estimations. By introducing the lag term of the dependent variable, the endogeneity problem that may exist in the model is effectively controlled. The estimation outcomes of the system’s GMM are shown in Table 6’s columns (3) and (4). This result indicates that, after controlling for endogeneity issues, the main conclusions in this paper remain robust.

5.2.5. Instrumental Variable Test

Table 7 presents the results of the IV test. Although we have tried our best to control the relevant factors affecting firms’ green innovation, the results may still be potentially affected by some unobserved variables, leading to certain biases. To mitigate the endogenous bias, we further adopt the endogenous test. Referring to Wang [67], we consider using the El Niño index as the instrumental variable (IV), which is the average value of a certain sea area’s sea surface temperature anomaly data. The adoption of this IV is based on the following considerations. There is a significant correlation between the El Niño phenomenon and climate phenomena in China. Moreover, as a climate phenomenon with global characteristics, it does not directly affect enterprises’ production and operation activities, thus meeting the selection criteria for IV.

Table 7.

The IV test.

Additionally, we construct the annual average of the El Niño index, as provided by the China Meteorological Administration. It processes this index as follows: IV equals the longitude of the enterprise headquarters location divided by the latitude of the enterprise headquarters × El Niño/1000. This is to capture the climate risks that listed companies face. The correlation between changes in sea surface temperature in the equatorial Pacific and potential climate risks at different geographical locations on the Chinese mainland, where enterprises are located, can be utilized to capture the changes in climate shocks faced by listed companies. The coefficients of columns (1)–(3) in Table 7 are still positive and significant at the 1% confidence level, which indicates that CRP can prompt Q&Q after considering this endogenous problem.

5.3. Mechanism Test

According to Hypothesis 2, we propose that the CRP promotes green innovation in firms by increasing the number of managers with environmental backgrounds and green investment. We mainly investigate its potential mechanism by using the mediating effect model. As seen from column (1) in Table 8, the CRP can significantly increase the proportion of environmental executives hired by enterprises. As seen from columns (2) and (3), Ebe plays a significant mediating role in promoting quantity by CRP but exerts a similar effect on quality. The possible reasons are that executives with a corporate environmental background typically have a stronger preference for green innovation, and their experience enables them to more easily identify the risks associated with climate uncertainty and take corresponding measures to mitigate these risks, thereby enhancing overall green innovation [58]. However, the actual innovation process may be limited by the management ability of senior executives and the organizational structure of enterprises, resulting in a limited effect on promoting quality [68].

Table 8.

The results of the mechanism tests.

Columns (4)–(6) in Table 8 show the mediating test of corporate green investment. The CRP can significantly promote the enterprises’ green investment behavior in column (4). Similarly, in columns (5) and (6), Gin plays a significant and complete mediating role in promoting quantity and quality. A potential explanation is that, through green investment, firms can proactively take measures to mitigate potential environmental risks, thereby improving the robustness and sustainability of their enterprises [46]. Second, through green investment, enterprises can access more innovation resources and opportunities, thus stimulating the vitality of green innovation. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is valid.

5.4. Moderation Effect Test

We explore the moderation effect by constructing interaction terms and further investigate and test the role of digital level and executives’ overseas management experience in regulating the CRP on Q&Q.

In Table 9, columns (1) and (2) are the results of the digital integration level. The coefficient of the interaction term is significantly positive, indicating that Dl can positively regulate the promoting effect of CRP on Q&Q. Specifically, as enterprises become more digitalized, their role in driving green innovation also increases. In addition, the interaction coefficient of column (1) is slightly larger than that of column (2), indicating that the quantity is more sensitive to the moderation effect of the quality.

Table 9.

The results of the moderation effect test.

Columns (3) and (4) in Table 9 are the test results of moderating executives’ overseas management experience. The interaction coefficient is significantly positive, indicating that the higher the proportion of executives with overseas management experience in the company, the more strongly the CRP can promote the enterprise’s Q&Q. The interaction coefficient value for quantity is higher than that for quality. This significant difference indicates that, compared to quality, quantity is more positively affected by executives’ overseas experience. This may mean that the number of green innovations is a more sensitive metric when assessing the impact of an executive team on a company’s innovation strategy. Therefore, when developing innovation strategies, companies may need to focus more on increasing the output of green innovation through the international experience of executives. Furthermore, this implies that when bringing in foreign talent, businesses should consider their breadth of experience and vision in green innovation. This will help businesses position themselves better to take the lead in the global green transformation wave and meet sustainable development objectives. As to the analysis above, Hypothesis 3 proposed is valid.

5.5. Heterogeneity Test

Enterprises’ pollution and technical characteristics are important factors influencing their green innovation. This paper classifies enterprises into two categories based on their pollution and technical characteristics: high-pollution and low-pollution enterprises, as well as high-tech and non-high-tech enterprises. The following regressions all controlled for covariates and incorporated time and individual fixed effects to ensure the accuracy of the results.

5.5.1. Heterogeneity of Enterprise Pollution Level

Referring to Ren et al. (2024), we match the enterprises’ industry codes with the highly polluting industries in the “Classification Catalogue of Heavily Polluting Industries” published by the Ministry of Ecology and Environmental Protection [39]. If an enterprise belongs to any of these industries, it is considered a highly polluting enterprise and is assigned a value of 1; otherwise, it is assigned a value of 0. The results of CRP on Q&Q in two types of enterprises are listed in Table 10 below.

Table 10.

Heterogeneity test on enterprise pollution level.

Among them, columns (1) and (2) show that the CRP indicates that the promoting effect of CRP on quality is positively significant in both types of enterprises. The Suest test determines the difference in the coefficients between the groups. The results show that the p-value of the coefficients between the groups is greater than 0.1. Therefore, the promoting effect of CRP on quality shows no significant difference between the two types of enterprises. Columns (3) and (4) show that the promoting effect of CRP on quality is significant in highly polluting enterprises, but not significant in low-polluting enterprises. Furthermore, a Suest test is conducted to determine the differences in the coefficients between groups. The results show that the p-value of the coefficients between groups is 0.000, indicating a significant difference. Therefore, it can be considered that in highly polluting enterprises, CRP greatly promotes the quality of green innovation.

The possible reasons are as follows: highly polluting enterprises are confronted with stricter environmental supervision and penalty risks, which force them to avoid policy risks through high-quality green innovation. Such enterprises have more pronounced negative environmental externalities, and the pressure from stakeholders is greater, compelling them to enhance their environmental performance through substantive innovation [69]. Additionally, the marginal benefits of technological transformation are higher for highly polluting enterprises. This is because the pollution costs of the original technologies are high, and green innovation can bring about more significant efficiency improvements and reputation returns. Compared with high-pollution industries, low-pollution enterprises face limited environmental compliance pressure, and their emission intensity is already within the safe range regulated by policies. This weakens the motivation of enterprises to seek further emission reduction through high-quality innovation. Specifically, at the level of resource allocation, limited R&D resources are often invested in technological innovations directly related to the main business. This strategic positioning leads to the short-term and fragmented characteristics of enterprises’ investments in green innovation. Furthermore, the market mechanism has also failed to provide effective incentives for the green innovation of such enterprises [70]. Consumers and investors often pay more attention to the environmental performance of highly polluting enterprises, which makes it difficult for low-polluting enterprises to obtain corresponding market premiums and capital favor for their green innovation investments, further weakening their intrinsic motivation to improve the quality of their green innovations.

5.5.2. Heterogeneity of Enterprise Technological Development

Referring to Peng et al. [71], firms are classified into high-tech and non-high-tech firms according to their technical characteristics in accordance with the “China High-tech Industry Statistical Yearbook”. The results of CRP on Q&Q in two types of enterprises are listed in Table 11 below. Columns (1) and (2) show that the CRP coefficient significantly and positively promotes CRP’s effect on quantity in both types, while the p-value of the Suest test is greater than 0.1. Therefore, the promoting effect of CRP on quantity shows no significant difference between the two types. The remaining two columns indicate that, based on the CRP coefficient, the promoting effect of CRP on quality is significant in high-tech enterprises but not in low-technology enterprises. However, the Suest test indicates that the inter-group coefficient’s p-value is 0.000, showing a significant difference. Therefore, it can be considered that in high-tech enterprises, the promoting effect of CRP on the quality of GI is more significant.

Table 11.

Heterogeneity test on enterprise technology.

The possible reasons are that high-tech enterprises usually have a solid R&D foundation and technological accumulation, enabling them to quickly identify climate risks and transform them into substantive green technology breakthroughs. Such enterprises are usually at the high end of the industrial chain. Additionally, high-tech enterprises are more likely to receive support, including green subsidies and carbon trading quotas, provided by the government [72]. These policy dividends reduce innovation costs, forming a virtuous cycle of “risk identification—innovation input—policy incentives”. This enables high-tech enterprises to demonstrate stronger green innovation capabilities and higher-quality innovation outputs when addressing climate risks.

Compared with high-tech enterprises, non-high-tech enterprises face obvious disadvantages in conducting research and development of cutting-edge green technologies, which is mainly reflected in the relative lack of talent reserves, knowledge accumulation, and technical infrastructure. When addressing climate risks, this technological capability gap makes it difficult for enterprises, despite having the willingness to innovate, to effectively digest and implement high-quality green innovation solutions due to insufficient technological absorption capacity [36,62]. For instance, policy tools such as R&D tax incentives and the recognition of high-tech enterprises usually focus more on high-tech enterprises, which puts non-high-tech enterprises at a disadvantage when accessing innovation resources and policy support. Meanwhile, the position of non-high-tech enterprises in the industrial chain also restricts their space for independent innovation. This dependent innovation model significantly expands the possibilities for non-high-tech enterprises to explore green technologies independently.

6. Conclusions

This study first constructs a Chinese firm-level CRP index to quantify enterprises’ responses to climate change-related risks. Then, we assess its impact on enterprises’ green innovation behavior. The results indicate that CRP can significantly enhance the Q&Q, and the promoting effect on quantity is greater than on quality. The CRP primarily promotes green innovation through two channels: increasing the proportion of managers with an environmental background and encouraging green investment. In addition, both the degree of external digital integration and the executives’ overseas management experience positively moderated the promoting effect. Furthermore, CRP has a larger promoting effect on both the Q&Q in highly polluting and high-tech enterprises, while its effect on the quality in low-polluting and non-high-tech enterprises is insignificant.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the differences in production modes and impact mechanisms in various industries may not have been fully accounted for. Given the significant heterogeneity in characteristics and innovation drivers among industries, this study primarily focuses on the quantity and quality of green innovation at the firm level but does not provide an in-depth analysis of green innovation dynamics within distinct industry contexts. Second, the study uses the number of green invention patents as a proxy for the quality of green innovation. However, this metric alone may not adequately capture the broader value of such innovations, as it fails to reflect tangible outcomes such as environmental improvements and economic benefits. Therefore, future studies should be conducted from an industry classification perspective to explore CRP’s role in further promoting green innovation in various industries. Third, with advancements in technologies such as machine learning, future research can harness these tools to improve the accuracy and reliability of analyses, enabling a more in-depth exploration of the potential nonlinear relationships between the two variables. For instance, big data analytics could enable more precise tracking of corporate green innovation trends, while machine learning techniques could help identify key determinants of green innovation, offering novel perspectives and deeper insights. Finally, future studies could employ targeted surveys or richer datasets with expanded variables to further investigate how executive characteristics and investment decisions interact and co-evolve, thereby enhancing understanding of the underlying mechanisms of the dual pathways.

Therefore, we can extract the following policy implications: Firstly, strengthen enterprises’ climate risk perception capabilities and promote the coordinated improvement of both the quantity and quality of green innovation. The results of this paper show that climate risk perception significantly encourages the quantity of green innovation in enterprises, but its role in quality improvement is relatively limited. Therefore, policy-making should systematically enhance enterprises’ capabilities to respond to climate risks and promote a leap in green innovation from “quantity” to “quality”. It is suggested that the government take the lead in establishing an “Enterprise Climate Risk Monitoring and Disclosure Platform”, integrating data on climate, physical, and transition risks, to provide enterprises with dynamic and actionable risk information. Meanwhile, through fiscal and tax incentives and financial tools, enterprises are guided to combine climate risk response strategies with high-quality green technology R&D. In particular, enterprises should be encouraged to focus on key areas such as low-carbon processes, circular economy technologies, and carbon-neutral solutions, rather than merely pursuing a large number of patents. In addition, a special project on “Climate Risk and Green Innovation” can be established within the national Key Research And Development Program to support enterprises and research institutions in collaborating on common technology breakthroughs, thereby enhancing the green innovation.

Secondly, we should deepen the integration of green governance and digitalization, and activate the dual-channel roles of managers and investors. CRP promotes green innovation by enhancing the role of environmental background managers and increasing the level of green investment, indicating that internal governance and resource allocation mechanisms are vital. Policies should encourage enterprises to incorporate climate risks into the strategic agendas of their boards and performance evaluations, promote the establishment of Chief Sustainability Officers or environmental professional committees, and prioritize appointing senior executives with backgrounds in environmental management. For small and medium-sized enterprises, they can be supported in introducing external environmental expert advisors by receiving “green governance subsidies.” On the other hand, efforts should be made to accelerate the deep integration of digitalization and greenization. By leveraging the “external digital integration” regulatory effect discovered through research, industry-level industrial Internet platforms and green supply chain management systems should be established to help enterprises achieve real-time collection, analysis, and optimization. In terms of green investment, we suggest expanding the scale of green industry funds, exploring a linkage mechanism between climate risk insurance and green investment, reducing the risks of enterprise transformation, and guiding financial institutions to develop financing products based on CRP ratings so that funds can flow more precisely to high-quality green innovation projects.

Thirdly, differentiated policy guidance should be implemented to support high-pollution and high-tech enterprises, thereby strengthening industry collaboration. The heterogeneous results of this paper suggest that policies should focus on precision and industry heterogeneity. For highly polluting industries, strict control over the total amount and intensity of carbon emissions should be implemented. The carbon market pricing mechanism and environmental protection law enforcement should be utilised to compel enterprises to transform CRP into substantive, innovative actions. At the same time, special funds should be allocated to support research and development of low-carbon alternative technologies. High-tech enterprises can rely on national high-tech zones and key laboratories to establish a “Climate Technology Innovation Alliance,” thereby accelerating the commercialisation and application of green patents. Policies should focus on awakening risk awareness and building basic capabilities for low-pollution and non-high-tech enterprises. For instance, free climate risk assessment, green technology directories, and transformation path guidelines can be provided through a pilot program for the green transformation of small and medium-sized enterprises.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.L.; Methodology, K.L.; Software, K.L. and X.Z.; Validation, K.L. and D.G.; Formal analysis, D.G. and X.Z.; Resources, D.G. and X.Z.; Data curation, D.G. and X.Z.; Writing—original draft, K.L. and X.Z.; Visualization, X.Z.; Project administration, K.L. and D.G.; Funding acquisition, D.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China grant number [72504213].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Climate risk perception measurement framework.

Table A1.

Climate risk perception measurement framework.

| Climate Risk Awareness | Climate Risk Identification | Environmental Governance | Risk and Opportunity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ozone | Typhoon | Carbon Price | New Energy |

| Air | Heavy Rain | Carbon Sink | Renewable |

| Pollution | Blizzard | Carbon Tax | Energy Efficiency |

| Quality | Cold Wave | Emission Reduction | Solar Energy |

| Temperature | Strong Wind | Carbon Peak | Water Resources |

| Sea | Sandstorm | Green Mountains and Clear Water | Tidal Energy |

| Level | Low Temperature | Low Carbon | Wind Energy |

| Carbon Dioxide | High Temperature | Decarbonization | Thermal Energy |

| Emissions | Drought | Air Monitoring | Geothermal Energy |

| Greenhouse | Thunderstorm | Compliance Emissions | Energy Management |

| Warming | Hail | Pollution-Free | Energy Conservation |

| Climate | Frost | Biodegradable | Water Conservation |

| Change | Dense Fog | Environmental Governance | Green |

| CO2 | Extreme | Pollution Reduction | Natural Gas |

| Environmental | Natural Disasters | Carbon Reduction | Photovoltaic |

| Pollution | Earthquake | Green Ecology | Nuclear Power |

| Nitrogen | Fire | Pollution Control | Wind Power |

| Oxides | Mudslide | Carbon Sequestration | Energy Consumption Reduction |

| GHG | Hurricane | Carbon Neutral | Energy Consumption |

| Dioxide | Storm | Dual Carbon | Energy Use |

| N2O | Tsunami | Peak Carbon | Coal Savings |

| - | Flood | Carbon Savings | Energy Savings |

| - | Water Disaster | Environmental Protection | Energy Conservation and Consumption Reduction |

| - | Urban Flooding | Protecting the Environment | Biomass |

| - | Flooding | Environmentally Friendly | Electric Vehicles |

| - | Flood Disaster | - | Hydrogen Energy |

| - | Drought Disaster | - | Electric Car |

| - | Snow Disaster | - | Electricity Consumption |

| - | Rainfall | - | Solar Thermal |

| - | Snowfall | - | Ocean Energy |

| - | Freezing | - | Hydropower |

| - | Dust | - | Biomass Energy |

| - | Haze | - | Nuclear Energy |

| - | Water Hazard | - | Green Hydrogen |

| - | Water-Related Disasters | - | Geothermal |

| - | Drought and Flooding | - | Electricity Conservation |

| - | Rain and Snow | - | Thermal Power |

| - | Cold Weather | - | Nuclear Power Plant |

| - | Sand and Wind | - | Nuclear Power Station |

| - | Storm Surge | - | Wind Farm |

| - | Flood Situation | - | Water Consumption |

| - | Intense Rainfall | - | Consumption Reduction |

| - | Cold Front | - | Resource Conservation |

| - | Drought Situation | - | - |

| - | Snow and Ice | - | - |

| - | Mountain Flood | - | - |

| - | Ice Disaster | - | - |

| - | Severe Cold | - | - |

References

- Du, M.; Antunes, J.; Wanke, P.; Chen, Z. Ecological efficiency assessment under the construction of low-carbon city: A perspective of green technology innovation. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2022, 65, 1727–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Cai, J.; Wu, K. The smart green tide: A bibliometric analysis of AI and renewable energy transition. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 5290–5304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Guo, Q. Green credit policy and green innovation in green industries: Does climate policy uncertainty matter? Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Yan, Y.; Dong, Y. Peer effect in green credit induced green innovation: An empirical study from China’s Green Credit Guidelines. Resour. Policy 2022, 76, 102619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Shen, Y.; Jiang, S. The effects of corporate governance uncertainty on state-owned enterprises’ green innovation in China: Perspective from the participation of non-state-owned shareholders. Energy Econ. 2022, 115, 106402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zeng, Y.; Wu, S.; Luo, X.R. How does artificial intelligence affect the environmental performance of organizations? The role of green innovation and green culture. Inf. Manag. 2024, 61, 103924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, T.; Chen, H.; Qi, X. Regional financial reform and corporate green innovation–Evidence based on the establishment of China National Financial Comprehensive Reform Pilot Zones. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 60, 104849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Lin, Y. Do more hands make work easier? Public supervision and corporate green innovation. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 91, 1064–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Chen, S.; Dai, L. How climate risk drives corporate green innovation: Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 59, 104762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Naseem, A. Artificial Intelligence in Sustainable Industrial Transformation: A Comparative Study of Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0. FinTech Sustain. Innov. 2025, 1, A2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzana, D.; Rizzati, M.; Ciola, E.; Turco, E.; Vergalli, S. Warming the MATRIX: Uncertainty and heterogeneity in climate change impacts and policy targets in the Euro Area. Energy Econ. 2024, 134, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zheng, M.; Feng, G.-F.; Chang, C.-P. Does an environmental policy bring to green innovation in renewable energy? Renew. Energy 2022, 195, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guo, X. The impact of resource misallocation on green technology innovation: Evidence from 288 cities in China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Cao, C. Impact of quality management on green innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, L.; Weng, C. Does climate policy uncertainty affect Chinese stock market volatility? Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2023, 84, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Guo, N.; Jin, J. Climate policy uncertainty risk and sovereign bond volatility. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.D.; Xia, Y. Panic selling when disaster strikes: Evidence in the bond and stock markets. Manag. Sci. 2023, 69, 7448–7467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Luo, N. Climate uncertainty and green index volatility: Empirical insights from Chinese financial markets. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 60, 104857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Borjigin, S. The amplifying role of geopolitical Risks, economic policy Uncertainty, and climate risks on Energy-Stock market volatility spillover across economic cycles. N. Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2024, 71, 102114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, K.; Ouattara, B. Climate and monetary policy: Do temperature shocks lead to inflationary pressures? Clim. Change 2021, 167, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Han, D.; Gozgor, G.; Mahalik, M.K.; Sahoo, B.K. The impact of climate policy uncertainty on renewable and non-renewable energy demand in the United States. Renew. Energy 2022, 197, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.F.; Pata, U.K.; Shahzad, L. Linking climate change, energy transition and renewable energy investments to combat energy security risks: Evidence from top energy consuming economies. Energy 2025, 314, 134175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadi, S.; Masum, A.-A. The impact of climate change on the cost of bank loans. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 69, 102019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Z. Corporate climate risk exposure and capital structure: Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 51, 103488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Azar, P.D. Endogenous production networks. Econometrica 2020, 88, 33–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wen, Y.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, H. The ripple effect of environmental shareholder activism and corporate green innovation: Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 93, 103136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addoum, J.M.; Ng, D.T.; Ortiz-Bobea, A. Temperature shocks and industry earnings news. J. Financ. Econ. 2023, 150, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kong, T.; Gu, L. The Impact of Climate Policy Uncertainty on Green Innovation in Chinese Agricultural Enterprises. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 62, 105145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Fu, C.; Huang, Q.; Lin, M. International political uncertainty and climate risk in the stock market. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2022, 81, 101683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Fu, W.; Albitar, K. Innovation with ecological sustainability: Does corporate environmental responsibility matter in green innovation? J. Econ. Anal. 2023, 2, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhong, X. Digital transformation and green innovation: Firm-level evidence from China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1389255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, B. ESG performance and corporate technology innovation: Evidence from China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 206, 123520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Lv, H.; Fung, A.; Feng, K. CEO turnover shock and green innovation: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 92, 894–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zou, X.; Li, P. Quantity or quality: Environmental legislation and corporate green innovations. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 204, 107684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Zhao, Y. The impact of carbon trading on the “quantity” and “quality” of green technology innovation: A dynamic QCA analysis based on carbon trading pilot areas. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, K.; Cao, L.; He, Y. Can green bonds promote corporate green technology innovation?—Evidence from China. Appl. Econ. 2024, 57, 3268–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Wen, J.; Li, Y.; Li, L. How does digital economy affect green technological innovation in China? New evidence from the “Broadband China” policy. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 81, 1093–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Zhou, X.; Wan, J. Unlocking Sustainability Potential: The Impact of Green Finance Reform on Corporate ESG Performance. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 4211–4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Li, W.; Duan, K.; Zhang, X. Does climate policy uncertainty really affect corporate financialization? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 4705–4723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Luo, L.; Tang, Q. Climate risk and opportunity exposure and firm value: An international investigation. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2024, 33, 5540–5562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X. Can climate risk exposure compel companies to undergo a green transformation? J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, X.; Kong, X. Do climate-related risks perception drive corporate green and low-carbon transformation? Evidence from listed companies in China. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2024, 60, 2938–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, X. Exploring the green technology collaboration network of the Yangtze River City cluster—from intra-cluster and inter-cluster perspectives. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, B.Y.; Hu, Z.Y.; Zhou, J.K. Environmental Protection-Oriented Executives, Power Distribution, and Corporate Environmental Responsibility Fulfillment. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2023, 9, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, M. Does chief executive officer turnover affect green innovation quality and quantity? Evidence from China’s manufacturing enterprises. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 81760–81782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Tian, W.; Zhu, Y.; Lyulyov, O.; Pimonenko, T. The Effect of Governance Structure on Green Technology Innovation: Based on the Internal Control Perspective. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2025, 33, early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Feng, G.-F.; Jang, C.-L.; Chang, C.-P. Terrorism and green innovation in renewable energy. Energy Econ. 2021, 104, 105695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Duan, K.; Ibrahim, H. Green investments and their impact on ESG ratings: An evidence from China. Econ. Lett. 2023, 232, 111365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Wang, F.; Song, G.; Liu, L. Digital transformation on enterprise green innovation: Effect and transmission mechanism. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasant, M.; Ganesan, S.; Kumar, G. Enhancing E-commerce Security: A Hybrid Machine Learning Approach to Fraud Detection. FinTech Sustain. Innov. 2025, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Tan, L.; Chen, Y. Smarter is greener: Can intelligent manufacturing improve enterprises’ ESG performance? Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Teo, T.S. Green technology innovation, environmental externality, and the cleaner upgrading of industrial structure in China—Considering the moderating effect of environmental regulation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 184, 122020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagar, V.; Schoenfeld, J. Measuring weather exposure with annual reports. Rev. Account. Stud. 2022, 29, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Tan, L.; Wu, J.; Gao, D. From risk to sustainable opportunity: Does climate risk perception lead firm ESG performance? J. Int. Financ. Manag. Account. 2025, 36, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughran, T.; Mcdonald, B. When is a liability not a liability? Textual analysis, dictionaries, and 10-Ks. J. Financ. 2011, 66, 35–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolov, T.; Sutskever, I.; Chen, K.; Corrado, G.S.; Dean, J. Distributed representations of words and phrases and their compositionality. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2013, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Barko, T.; Cremers, M.; Renneboog, L. Shareholder engagement on environmental, social, and governance performance. J. Bus. Ethic 2022, 180, 777–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Mu, Z.; Li, L. The impact of corporate environmental responsibility on green technological innovation: A nonlinear model including mediate effects and moderate effects. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 80, 754–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Said, R.M.; Rahim, N.A.; Ni, M. Can green finance Lead to green investment? Evidence from heavily polluting industries. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 95, 103445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Hu, H.Z.; Lin, H.Y.; Ren, X.Y. Enterprise Digital Transformation and Capital Market Performance: Empirical Evidence from Stock Liquidity. Manag. World 2021, 37, 130–144. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, X. Executives with overseas background and green innovation. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Gao, D.; Tan, L. Strategic or Substantive: The Role of Green Finance in Shaping Enterprise Green Innovation. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 104, 104636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Mbanyele, W.; Wang, F.; Song, M.; Wang, Y. Climbing the quality ladder of green innovation: Does green finance matter? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 184, 122007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Jin, S.; Ni, J.; Peng, K.; Zhang, L. Strategic or substantive green innovation: How do non-green firms respond to green credit policy? Econ. Model. 2023, 126, 106451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, S.; Fan, Z. Modeling the role of environmental regulations in regional green economy efficiency of China: Empirical evidence from super efficiency DEA-Tobit model. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 261, 110227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, S.I.; Khan, M.K.; Sun, T.; Khan, U.; Wang, X.; Niu, Y. Government innovation support for green development efficiency in China: A regional analysis of key factors based on the dynamic GMM model. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 995984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Climate Shocks and Corporate Default Risk: A Physical Risk Perspective. J. World Econ. 2025, 48, 90–110. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, Y.; Zhou, Y.P. How does the "Belt and Road" initiative affect green innovation in patent-intensive industries in China’s provinces along the route? China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2023, 10, 85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Tan, L.; Peng, J. Restraint or guidance? The impact of institutional investors’ herding behavior on firm innovation. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 85, 108247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Tan, L.; Chen, Y. Unlocking carbon reduction potential of digital trade: Evidence from China’s comprehensive cross-border e-commerce pilot zones. Sage Open 2025, 15, 21582440251319966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Lee, C.C.; Xiong, K. What determines the subsidy decision bias of local governments? An enterprise heterogeneity perspective. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2021, 57, 1215–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Tan, L. Lighting a green future: The role of FinTech in the renewable energy transition. Sci. Prog. 2025, 108, 00368504251323566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).