Abstract

Based on structural equation modeling, the influence paths and group differences in residents’ low-carbon living behaviors and consumption behaviors were explored in six low-carbon pilot cities in China from the perspectives of low-carbon policy perception and low-carbon information dissemination. The results showed that residents in different pilot cities significantly differed in their low-carbon intention and low-carbon behavior, especially in Hangzhou and Chengdu, which had high low-carbon intention and low-carbon behavior. Low-carbon intention was the core driving force that promoted residents’ low-carbon behavior. Low-carbon policy perception and information dissemination impacted residents’ low-carbon intention and low-carbon behavior, with differences among different pilot cities. Residents in Chengdu and Wuhan showed a significant positive correlation in the direct and indirect paths of low-carbon policy perception on low-carbon behavior. In contrast, residents in Hangzhou showed a significant positive correlation in the impact path of low-carbon information dissemination on low-carbon consumption behavior. In addition, groups with different demographic characteristics significantly differed in the influence paths of their low-carbon behavior. Finally, targeted recommendations were proposed to promote differentiated strategies for implementing low-carbon behaviors, aiming to enhance public awareness and action capacity and support China’s low-carbon transition and carbon reduction goals.

1. Introduction

Cities are major consumers of energy. In addition to industrial production and agricultural activities, daily household behaviors—such as residential energy use, appliance operation, transportation choices, and consumption preferences—can directly or indirectly influence carbon emissions [1]. Due to the rapid advancement of urbanization and the improvement of urban residents’ living standards, residents’ energy consumption has increased significantly, and the resulting carbon emissions have increased yearly [2]. The Emissions Gap Report 2023 (DEW/2589/NA) issued by the United Nations Environment Programme points out that carbon emissions generated by household activities account for approximately two-thirds of the global total. These emissions primarily originate from residential energy consumption, private transportation, and the embodied emissions in carbon-intensive consumer goods. The report further highlights that China is facing significant challenges regarding household carbon emissions. With rapid urbanization and rising living standards, China’s per capita carbon emissions have continued to increase and have now surpassed the global average. The United Nations Population Division indicates that China’s urbanization rate has far exceeded the Asian and global averages since 2000, with the urban population projected to reach approximately 68% by 2050 [3,4]. Given this trend, future residential emissions are difficult to estimate, and China is expected to face mounting pressure to reduce emissions and undergo a stringent low-carbon transition [5,6].

To address this challenge, the Chinese government has formulated and implemented a series of policy documents promoting low-carbon urban development since the initiation of the 12th Five-Year Plan [6,7]. These measures, including tax incentives [8], promotion of clean energy and energy-saving materials, and intensified public awareness campaigns [9], aim to guide residents toward adopting green and low-carbon lifestyles and consumption patterns [10]. In 2024, the “Action Plan for Energy Conservation and Carbon Reduction (Guo Fa [2024], No. 12)” released by the Chinese government pointed out that the power of the media should be utilized to enhance the publicity of energy conservation and environmental protection, raise public awareness of low-carbon living, improve the public participation mechanism, and create a social atmosphere where all citizens participate in energy conservation and carbon reduction. Despite growing environmental awareness, there remains a notable gap between residents’ low-carbon intentions (LCI) and actual behaviors. A relevant study has shown that low-carbon behavior (LCB) is affected by both internal and external factors [11]. The compounded effect of these factors leads to a deviation between residents’ LCI and their actual behavior, reducing the implementation effect of low-carbon policies and restricting the process of social low-carbon transformation [12].

Policy instruments serve as significant contextual factors influencing residents’ adoption of LCB, categorized into four distinct types: informational, economic, technological, and regulatory [5,13]. Policy perception plays a key role in influencing residents’ LCI. Residents’ perceptions of policy can be used as feedback on policy implementation effects, providing valuable information for policymakers. Understanding residents’ views and expectations about existing policies can help policymakers design future policies that are more effective and more in line with the needs of the public [14,15]. However, individual differences in values, modes of policy dissemination, implementation strategies, and social environments result in heterogeneous perceptions of low-carbon policies, leading to varying willingness and behavioral outcomes [16,17]. A survey by Lin and Lan revealed that policy perception significantly influences LCB in China’s first-tier cities, with notable variations across genders and regions [15]. Wang incorporated policy perception into their framework for studying low-carbon consumption behaviors (LCCB), discovering that fiscal incentives and perceptions of convenience influence purchasing intentions, though such effects differ among consumers [18]. Nevertheless, some scholars have pointed out limitations to incentive-based policies. Implementing economic subsidies often entails high costs for governments [19], and their effectiveness in promoting LCB among residents is sometimes limited or short-lived [20].

Information plays a key role in shaping public perception and behavior [21,22]. Multi-channel dissemination methods, including government campaigns, media coverage, interpersonal communication, and community activities, have been incorporated into research frameworks exploring drivers of LCB [23]. In the digital era, both traditional and emerging media have become vital channels for disseminating low-carbon information. Through real-time reports, interactive entertainment, and promotional campaigns, media platforms raise environmental awareness, improve policy comprehension, and encourage behavioral practices [22,24]. The dissemination of low-carbon information through different channels promotes the emergence of LCI. However, if there is a lack of external incentive conditions, such as a good publicity environment [25], community environment [26], and social norms, it may hinder the generation of LCB among residents.

The Emissions Gap report 2023 (DEW/2589/NA) points out that the distribution of global carbon emissions is extremely unequal, with the richest 10% of the population contributing almost half of consumer carbon emissions, and the trend of emissions is still increasing. Large cities are not only the population and economic centers of China, but also highly concentrated areas of energy consumption and carbon emissions, with a relatively high proportion of high-income groups. Given these findings, it is crucial to further investigate the gaps and mechanisms influencing LCI and LCB in large urban populations. Therefore, it is essential to further explore the different characteristics and influence paths of LCB among residents of large urban areas and formulate intervention measures to act against travel alienation according to the characteristics impacting different regions and the different attributes of their different populations to improve residents’ low-carbon motivation. Despite the growing body of research on LCB motivations, consensus remains elusive. Existing studies focus on specific regions, leaving a gap in the understanding of regional differences in LCI and actions under a unified analytical framework. This limitation makes it challenging to develop targeted, differentiated strategies to guide residents’ LCB effectively.

Building on the above research background, this study breaks through the limitation of most studies focusing only on a single dimension from a theoretical perspective, incorporating both policy perception and information dissemination into a unified analytical framework, and thus systematically revealing the direct and indirect paths of influence of these dimensions on residents’ low-carbon willingness and behavior. Compared with the usual research, focusing on a single city, we selected residents from six low-carbon pilot cities distributed in different regions of China as samples and conducted in-depth multi-group analysis (covering gender, age, education, income, and housing status) on this basis, thereby clearly revealing the significant differences in the influence paths among different cities and groups with different development backgrounds. Based on empirical findings and the characteristics of urban development, we propose targeted strategies to promote LCB among residents. These recommendations are designed to enhance public awareness and participation in low-carbon practices, thereby contributing to the carbon reduction goals of China. The remaining chapters of this study are as follows. Section 2 proposes research hypotheses and builds the theoretical framework of this paper based on relevant theories. Section 3 introduces the research methods and data sources. Section 4 is devoted to a detailed analysis of the results. Section 5 discusses the findings and proposes targeted policy recommendations. Section 6 is devoted to a summary of the main research conclusions and future research.

2. Research Hypothesis and Framework

Human behavior serves as an intermediary linking the natural and social environments. The formation of human behavior is a complex process influenced by instincts, psychological needs, individual cognition, and social environments. Residents’ LCBs are environmentally friendly actions aimed at protecting ecosystems and reducing carbon emissions based on low-carbon awareness [27]. A variety of theoretical models have been applied to research on residents’ LCB, including the Rational Behavior Theory (RBT), the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), the Information–Motivation–Behavior Model (IMB), the Attitudinal-Behavior-External Conditions Model (ABC), the Stimulus–Organism–Response Theory (SOR), Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), Cognitive Dissonance Theory (CDT), and the Knowledge Gap Theory (KGT).

The Rational Behavior Theory, proposed by Fishbein and Ajzen in 1975, posits that humans are rational beings whose behaviors are controlled by conscious decisions. Before acting, individuals evaluate the value and potential outcomes of their actions based on available information, ultimately making behavioral decisions. According to this theory, behavioral intentions can reasonably predict actual behaviors. However, although LCI plays a critical role in implementing behaviors, the transformation from intention to behavior is not linear. When skills, resources, or opportunities constrain actions, the Rational Behavior Theory struggles to fully explain behavior occurrence. Ajzen expanded the theory in 1991 by proposing the TPB to address this limitation. This theory suggests that adopting a specific behavior depends on behavioral intention and subjective perceptions. The TPB has since been widely applied in the field of LCB research. LCI can be understood as the internal subjective tendency of individuals to save resources, protect the environment, and reduce carbon emissions in daily life and work scenarios. Studies have demonstrated that LCI is a key internal factor driving LCB [28]. Individuals’ values and beliefs about the environment influence their LCI [9,29], which in turn promotes actual behaviors. As research deepens, scholars have emphasized the influence of policy perceptions on residents’ LCB decisions. Several studies have incorporated the technology acceptance model into LCB research. Findings reveal that perceived economic usefulness (residents’ recognition of the economic benefits of LCB) and perceived environmental usefulness (residents’ perception of the environmental protection benefits of such behaviors) positively influence environmental awareness and perceived behavioral control [15,30]. These factors, in turn, significantly enhance LCI and policy acceptance, encouraging individuals to adopt more responsible low-carbon living behavior (LCLB) and LCCB. A series of policies introduced by the government, such as renewable energy subsidy policies and green building standards, have enabled residents to understand the country’s strategic intentions for addressing climate change and promoting low-carbon development [31]. After perceiving the rationality and effectiveness of the policy, residents are made to realize that LCB offers both environmental benefits and certain economic benefits. At the behavioral level, policy perception exerts both motivating and constraining effects on residents. Incentive policies such as tax preferences and financial subsidies directly reduce the cost for residents to engage in LCB, which makes residents more inclined to actively make LCB choices. Binding policies such as carbon emission standards and energy consumption quotas force residents to reduce high-carbon behaviors. When residents realize that some of their behaviors may violate policy regulations and face economic penalties or social public opinion pressure, they will actively adjust their behaviors.

Nevertheless, some scholars argue that focusing solely on internal factors when studying individual behavior is insufficient. An individual’s perception, attitude, and external environmental factors collectively determine their confidence in successfully performing a behavior—called self-efficacy—which subsequently affects behavioral choices. Similarly, the Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) Model emphasizes that external stimuli—including physical, social, and cultural influences—can significantly shape individuals’ internal psychological states and behavioral motivations, ultimately driving decision-making processes [32]. This model underscores the critical role of external factors in resident behavior studies, and subsequent research has validated their applicability. LCB among residents represents integrated responses to internal psychological states and external stimuli. Empirical studies confirm that external stimuli, such as subsidies and policy incentives, can significantly influence self-efficacy [18,20], thereby shaping tendencies toward LCB. However, the effects of such incentives vary depending on implementation methods, communication channels [24], and individual perceptions, resulting in uncertain outcomes. According to Rational Choice Theory, information obtained from external environments is the foundation for forming environmental attitudes, subsequently influencing behavioral decisions [24]. Social norms, community publicity, interpersonal communication, and internet media are important communication channels for residents to obtain information about low-carbon policies and other low-carbon information. Through these communication channels, information such as low-carbon living guidelines, energy conservation and emission reduction technologies, the impact of carbon emissions on the environment, and related subsidy policies can be conveyed to residents, enabling them to have a more comprehensive understanding of the various forms and importance of LCB. This also provides clear behavioral guidance for residents, improving the convenience and operability of implementing LCB. Through dissemination and influence by the media, individuals, and groups, internal factors such as residents’ self-efficacy and environmental responsibility may be changed, thereby promoting or inhibiting the formation of resident awareness and habits with regard to LCB [17,23].

Furthermore, inconsistencies in LCI and LCB may vary among residents with different demographic attributes [29,33]. Due to their different life stages, people of different ages usually have differences in their understanding of environmental issues and consumption concepts. Young people usually have a high acceptance of new things, are more willing to try new lifestyles and technologies, and pay more attention to the personalization and quality of their consumption. As middle-aged people shoulder more family responsibilities, their consumption behavior may be determined more from the perspectives of economy and practicality. Elderly consumers tend to prioritize the practicality and durability of products. They are more sensitive to the prices of items and may be more cautious when choosing products. An individual’s learning ability, acceptance of new things, and values may vary due to different educational levels. Under normal circumstances, people with higher educational qualifications may be more efficient in understanding scientific knowledge and consulting policy information, and these abilities will further influence their behavioral decisions. There are differences in daily living habits and consumption capabilities among people of different income levels. People with higher incomes usually pay more attention to the quality of life in their daily lives and have a stronger economic foundation and consumption capacity. They are relatively less sensitive to prices when consuming. In addition, people living in the houses they purchased have stronger autonomy in decision-making, pay more attention to long-term economic benefits and asset appreciation, and may be more willing to invest costs in energy conservation and environmental protection renovations. Relevant studies have confirmed that there are differences in LCB among residents with different demographic attributes. Yin and Shi found that gender and educational attainment indirectly affect the relationship between social interaction and LCB [23]. Ling and Xu observed that individual values strongly influence environmental behaviors in areas with higher female populations or greater access to social interaction spaces [34]. Park and Lin demonstrated that educational background and income levels positively influence sustainable consumption behaviors among South Korean residents [35]. However, other empirical studies reached different conclusions, arguing that demographic factors—such as education, income, and age—do not significantly influence LCB [36,37]. Household structure, family size, and homeownership also significantly affect LCB. Being more affected by economic cost and a sense of belonging, residents who own houses may be more willing to implement LCB [5]. In summary, promoting LCB requires a multifaceted approach. Efforts should focus on raising public awareness, establishing supportive policies and market environments, and providing feedback and incentive mechanisms. Additionally, leveraging community campaigns and media channels to disseminate low-carbon information and showcase behavioral models is essential. Understanding group differences and low-carbon preferences is equally critical. Such insights can help policymakers and practitioners design more customized and effective intervention strategies, ultimately enhancing individuals’ awareness and ability to adopt LCB.

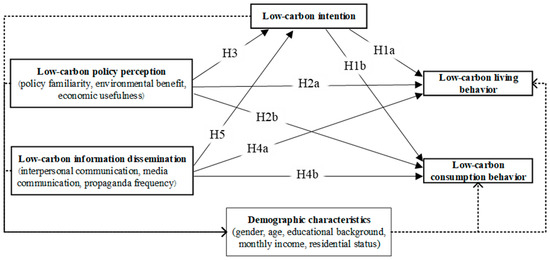

Building on the above analysis, we propose the following research hypotheses and develop a conceptual framework to examine the path influencing residents’ LCI, LCLB, and LCCB, focusing on low-carbon policy perception (LCPP) and low-carbon information dissemination (LCID) as internal and external factors, respectively. The research hypothesis testing framework is illustrated in Figure 1. LCPP includes three dimensions: policy familiarity, environmental benefits, and economic usefulness. LCID encompasses interpersonal influence, social media dissemination, and promotional frequency. Additionally, the framework incorporates demographic variables—such as gender, age, educational background, monthly income, and residential status—to explore whether the paths influencing LCI and LCB differ across groups with varying characteristics. The research hypotheses are as follows:

Figure 1.

Research framework.

H1a.

LCI positively influences residents’ LCLB.

H1b.

LCI positively influences residents’ LCCB.

H2a.

LCPP positively influences residents’ LCLB.

H2b.

LCPP positively influences residents’ LCCB.

H3.

LCPP positively influences residents’ LCI.

H4a.

LCID positively influences residents’ LCLB.

H4b.

LCID positively influences residents’ LCCB.

H5.

LCID positively influences residents’ LCI.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Survey Questionnaire Design

Referring to relevant literature and the “Guidelines for Quantifying Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction of Citizens’ Green and Low-Carbon Behaviors (T/ACEF 031-2022)” issued by the All-China Environment Federation, after conducting pre-research and validity tests, the questionnaire used in this study was determined, as shown in Table 1. The survey questionnaire includes six parts. The first section asks for basic information about the respondents, including gender, age, education level, monthly income, occupation, and housing situation. The subsequent sections assess five key areas: LCPP, LCID, LCI, LCLB, and LCCB. A total of 17 items were included in the questionnaire, each of which used the five-level Likert scale, with the options set as 1–5 and the degree of identification from low to high. The section on low-carbon policy perception includes four items, primarily aimed at gauging the respondents’ familiarity with popular low-carbon policies and their views on the influence of these policies on environmental improvement. The low-carbon information dissemination section contains three items: interpersonal influence, media influence, and the frequency of communication on low-carbon issues. The four items measuring LCI assess respondents’ willingness to adopt low-carbon lifestyles and consumption practices in the context of policy incentives and technological innovations. In addition, six questions were set to investigate the energy-saving habits and behaviors of the respondents in their daily lives and consumption habits.

Table 1.

Questionnaire design.

3.2. Data Collection

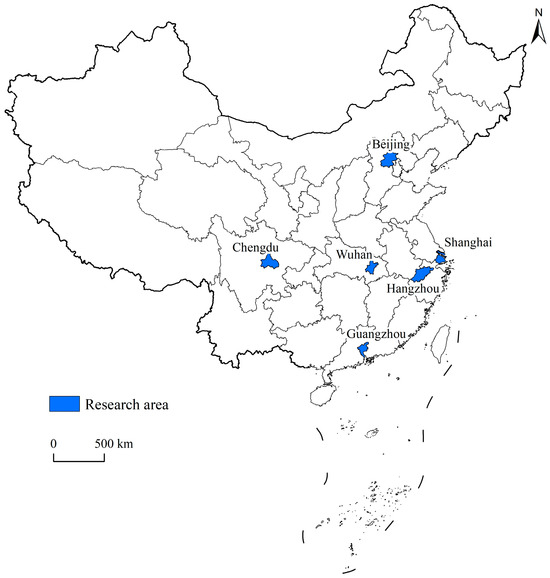

This study selected six large cities with permanent populations of over 10 million—Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Hangzhou, Wuhan, and Chengdu—as the research areas (the geographical locations of these cities are shown in Figure 2. These cities represent important central hubs in the northern, southern, central, western, and eastern regions of China. They are characterized by high levels of economic development and active residents while facing significant carbon reduction pressures. Residents in these regions are more enthusiastic about participating in LCB surveys and exhibit a stronger response to LCB [41]. In 2010, 2012, and 2017, the Chinese government listed these six cities as low-carbon pilot cities and tasked them with developing low-carbon development plans, establishing greenhouse gas emission target responsibilities, and promoting low-carbon lifestyles. This is a strategic move by China to strengthen its national contributions and promote regional low-carbon development. Under policy support and market mechanisms, these pilot regions have successfully slowed the pace of carbon dioxide emissions through measures such as actively promoting technology development, establishing carbon emission trading markets, researching and promoting the use of renewable energy, guiding industrial green transformations, and enhancing green infrastructure. These efforts have strengthened urban ecosystem resilience and provided replicable low-carbon development models and experiences for other regions in China [42]. By selecting residents from these six cities in different regions, the study aims to provide a broader understanding of the current status and differences in residents’ LCI and LCB across various social and regional contexts in China. This will provide scientific evidence for the formulation and evaluation of low-carbon policies.

Figure 2.

Geographical location diagram of the research area.

From July to August 2023, members of the research group randomly distributed questionnaires to residents who lived in the local area for more than half a year through face-to-face inquiry and an online questionnaire platform, and finally obtained 2313 valid questionnaires (414 in Beijing, 314 in Shanghai, 368 in Guangzhou, 327 in Chengdu, 411 in Hangzhou, and 479 in Wuhan). Random stratified sampling was used in different areas of each city to make the proportion of different groups as consistent as possible. This study strictly adhered to data privacy and protection principles. During the data collection process, an anonymized approach was adopted, and no personally identifiable information was obtained. All data were used solely for academic research purposes and kept strictly confidential. Respondents were clearly informed of the above before starting the questionnaire, and their completion of the survey was deemed to constitute informed consent. Table 2 presents the demographic characteristics of the samples. Among the survey, 45.09% were male and 54.91% were female. Regarding age distribution, 23.78% were aged ≤ 25 years, 34.63% were between 26 and 35 years, 25.77% were between 36 and 45 years, 10.64% were between 46 and 55 years, and 5.19% were aged ≥ 56 years. Respondents with a junior college degree or below accounted for 30.18%, respondents with a bachelor’s degree accounted for 44.01%, and those with a master’s degree or above accounted for 25.81%. In terms of monthly income, 19.20% of respondents had a monthly income < 3000 RMB (approximately 422.24 USD, the exchange rate is based on 15 November 2025. The same below), 14.14% of respondents had a monthly income of 3000 RMB to 5000 RMB (approximately 422.24 USD to 703.73 USD), 24.21% of respondents had a monthly income of 5000 RMB to 8000 RMB (approximately 703.73 USD to 1125.97 USD), and 42.45% of respondents had a monthly income > 8000 RMB (approximately 1125.97 USD). Regarding living conditions, 54.86% of the respondents lived in self-owned houses, and 45.14% lived in non-self-owned houses.

Table 2.

Statistical table of demographic characteristics of respondents.

3.3. Research Methods

The Structural Equation Model usually includes two parts: measurement model and structural model. The measurement model is used to analyze the relationship between latent variables (abstract concepts that cannot be directly observed or measured) and observed variables (variables that can be directly observed or measured through questionnaires), while the structural model is mainly used to analyze the causal relationship and influence path between latent variables [29]. Multi-group analysis in structural equation models can compare the differences in potential variables between different groups and explore and identify moderating variables that may affect the relationship between potential variables to develop targeted strategies [37]. This study is based on a structural equation model to explore the influencing factors of residents’ LCI and LCB in China’s pilot low-carbon cities and explore the differences among different groups. The calculation formula of this model is as follows:

In the formula, Formulas (1) and (2) are measurement models, and Formula (3) is the structural model. is the external potential variable, is the observed variable or measurement variable , is the coefficient matrix of variable , which is linked to variable , is the internal potential variable, is the observed variable or measurement variable , is the coefficient matrix of variable , linked to variable , and and are measurement errors. is the directional connection coefficient matrix between the internal potential variables; is the regression coefficient matrix of the influence of the external potential variable on the internal potential variable; is the error value if the internal potential variable cannot be explained by the external potential variable.

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity Test of the Model

Before analyzing the influencing path of residents’ LCB, the reliability and validity of the questionnaire data were tested by measuring parameters such as Cronbach’s Alpha (Cronbach’s α), Combined Reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the research results. The results were shown in Table 3 and Table 4. Firstly, the reliability analysis tool of SPSS 24 software was used to calculate Cronbach’s αof five variables in each pilot city, and the results ranged from 0.633 to 0.842, all higher than 0.6, passing the internal consistency test of the scale. Then AMOS 24 was used to draw the analysis model, and the data were imported into the model to calculate the measurement variables. The results of CR ranged from 0.682 to 0.849, and AVE extracted ranged from 0.413 to 0.663, both of which were greater than 0.6 and 0.4, respectively [43,44]. The results showed a strong internal correlation between the observed variables and the potential variables and had good internal reliability and convergence validity, which can be used for further hypothesis-testing research. The results in Table 5 showed that the square roots of AVE were all greater than the correlation coefficients between variables, indicating that the model has good discriminant validity.

Table 3.

The results of the reliability and validity tests of the scale.

Table 4.

The test results for discriminating validity.

Table 5.

The results of goodness-of-fit indices.

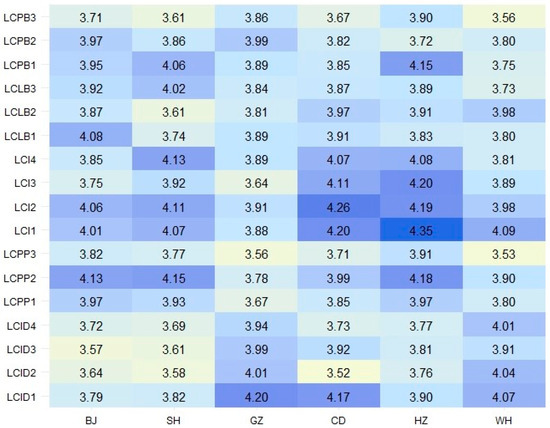

4.2. Descriptive Statistical Analysis of the Questionnaire

Figure 3 shows the statistical result of the average score of each question in the questionnaire. Statistically, residents in different cities showed significant differences in LCPP, LCID, LCI, and LCB. In terms of LCPP, the average score in Guangzhou was as high as 4.03, followed by Wuhan (average score of 4.01), indicating that respondents of these two cities had a high degree of familiarity and identification with low-carbon policies. Among them, 73.91% of respondents in Guangzhou agreed that implementing low-carbon policies would positively influence urban environmental quality and quality of life. In terms of LCID, more respondents in Hangzhou and Beijing answered “agree”, with proportions of 76.56% and 72.62%, respectively, indicating that the two cities had effectively combined traditional and new media to carry out some of the indicated activities, and residents were more willing to share their experiences with low-carbon behaviors and influence each other in social interactions. In terms of LCI, the average score in descending order was Hangzhou (4.20) > Chengdu (4.16) > Shanghai (4.06) > Wuhan (3.94) > Beijing (3.92), indicating that residents of the six pilot cities generally had LCI. Among the respondents in Hangzhou and Chengdu, 82.73% and 80.81% answered “agree”, indicating that residents in these two cities were strongly aware of environmental protection and low-carbon actions in their daily lives. Residents in different cities also had significant differences in the practice of LCLB and LCCB. Overall, the average score of LCLB was 1.15 higher than that of LCCB. Residents in Beijing and Chengdu paid more attention to LCLB, with 71.58% and 70.03% of respondents answering “agree”, respectively. Residents in Hangzhou and Guangzhou showed a higher enthusiasm for low-carbon consumption, with an average score of 3.92 and 3.91, respectively.

Figure 3.

Average score statistics of questionnaire questions. (Note: “BJ” indicates Beijing, “SH” indicates Shanghai, “GZ” indicates Guangzhou, “CD” indicates Chengdu, “HZ” indicates Hangzhou, “WH” indicates Wuhan).

4.3. Analysis of the Influence Path of Residents’ LCB

Firstly, the goodness-of-fit indices of the structural equation model were tested based on confirmatory factor analysis, and various parameters were calculated. The results can be found in Table 5. It can be seen from the results that the values of CMIN/DF were all less than 3, the values of GFI, AGFI, and IFI were all greater than or close to 0.9, the values of PGFI, PNFI, and PCFI were all greater than 0.5, and the values of RMSEA were all less than 0.08. All indicators were within the acceptable range, which indicated that the model had good fitting quality [23,38].

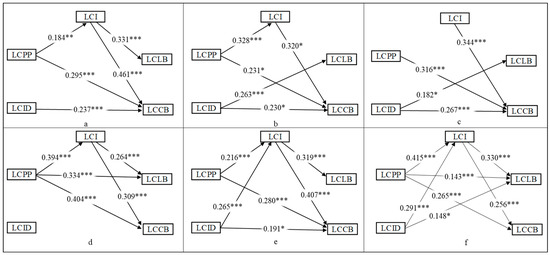

Figure 4 shows the influence path results of LCPP and LCID on the LCI, LCLB, and LCCB in the six pilot cities in China. It can be seen from the results that LCPP, LCID, and LCI all played an important role in promoting residents’ LCLB and LCCB in pilot cities, and there were significant differences in the influence paths of different cities. The research of Wang et al. also confirmed that high intention did not necessarily translate into low-carbon behaviors, and was also affected by factors such as personal perception, publicity, and education [9].

Figure 4.

Coefficient of influence path of residents’ LCB. (Note: * p-value < 0.05, ** p-value < 0.01, *** p-value < 0.001.; “a” indicates Beijing, “b” indicates Shanghai, “c” indicates Guangzhou, “d” indicates Chengdu, “e” indicates Hangzhou, and “f” indicates Wuhan).

(1) The direct influence of “LCI→LCLB/LCCB”: Respondents living in Beijing, Wuhan, Hangzhou, and Chengdu had a direct and significant positive influence on the path of “LCI→LCLB”, and the path coefficients in Beijing and Wuhan were higher, 0.331 and 0.330, respectively. In contrast, there was no significant influence in Shanghai and Guangzhou. Therefore, the research hypothesis H1a was accepted in Beijing, Wuhan, Hangzhou, and Chengdu. The LCI had a direct and significant positive influence on the LCCB of all pilot cities, and the path coefficients in descending order were Beijing (0.461) > Hangzhou (0.407) > Guangzhou (0.344) > Shanghai (0.322) > Wuhan (0.256). It can be seen that the research hypothesis H1b was accepted by all pilot cities, among which the Beijing respondents’ LCI had the most significant influence on LCCB.

(2) The direct and indirect influence of LCPP on LCLB/LCCB. Respondents in Chengdu and Wuhan showed a direct and significant positive influence, with path coefficients of 0.334 and 0.143, respectively. In contrast, other cities did not reach the level of significance. So, the research hypothesis H2a was accepted only in Chengdu and Wuhan. The residents’ LCPP in all pilot cities had a direct and significant positive influence on LCCB, among which Chengdu and Guangzhou were the most significant, with path coefficients of 0.404 and 0.316, respectively. Therefore, the research hypothesis H2b was verified in all pilot cities. The indirect influence path of “LCPP→LC→LCLB/LCCB” was further verified. We found that residents’ LCPP in Shanghai, Beijing, Chengdu, Hangzhou, and Wuhan significantly influenced LCI, and the path coefficients were 0.328, 0.184, 0.394, 0.216, and 0.415, respectively. Therefore, hypothesis H3 was accepted in these five cities, which indicated that residents in Shanghai, Beijing, and Hangzhou could indirectly promote the implementation of LCLB and LCCB by enhancing their LCPP, and residents in Chengdu and Wuhan could also indirectly promote the implementation of LCCB by enhancing their LCPP.

(3) The direct and indirect influence of LCID on LCLB/LCCB. The residents’ LCID in Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Wuhan directly and significantly positively influenced LCLB, with path coefficients of 0.263, 0.182, and 0.148, respectively. Therefore, the research hypothesis H4a was accepted in these three pilot cities. As the residents’ LCID in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Hangzhou directly and significantly positively influenced LCCB, research hypothesis H4b was accepted in these four cities. The indirect influence path of “LCID→LCI→LCLB/LCCB” was further verified. We found that residents’ LCID in Hangzhou and Wuhan significantly influenced LCI, so hypothesis H5 of the two cities was accepted. At the same time, it also meant that residents in Wuhan could indirectly promote the implementation of LCLB by enhancing their LCI through LCID, while Hangzhou residents could indirectly promote the implementation of LCCB by enhancing their LCI through LCID.

4.4. Multi-Group Analysis of the Influence Path of Residents’ LCB

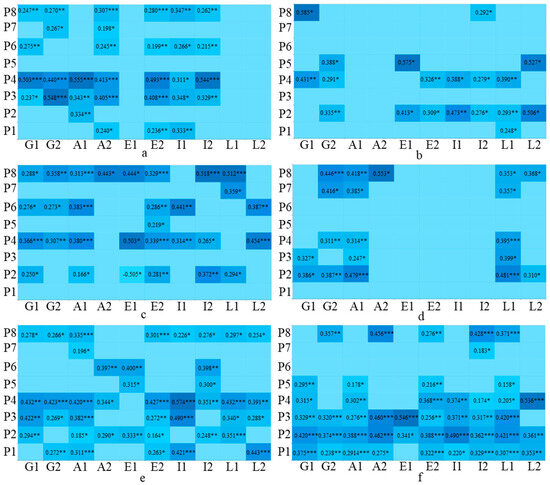

To explore the different characteristics of the LCB influence paths of different groups, the respondents’ demographic characteristics were classified as shown in Table 6. Before the analysis, the model’s goodness-of-fit indices in each pilot city were also tested, and the results are shown in Table 7. We can see that each parameter was within the acceptable range, indicating that the multi-group analysis model had good fitting quality. The results of the multi-group analysis are shown in Figure 5. From the results, it can be seen that the influence paths of residents’ LCB showed significant differences between different pilot cities and groups.

Table 6.

Demographic characteristics of multi-group analysis.

Table 7.

The goodness-of-fit index results of multi-group analysis.

Figure 5.

Multi-group results of influencing paths of residents’ LCB. (Note: P1 indicates the influence path “LCID→LCI”, P2 indicates the influence path “LCPP→LCI”, P3 indicates the influence path “LCI→LCLB”, P4 indicates the influence path “LCI→LCCB”, P5 indicates the influence path “LCID→LCLB”, P6 indicates the influence path “LCID→LCCB”, P7 indicates the influence path “LCPP→LCLB”, and P8 indicates the influence path “LCPP→LCCB”.). (Note: * p-value < 0.05, ** p-value < 0.01, *** p-value < 0.001. “a” indicates Beijing, “b” indicates Shanghai, “c” indicates Guangzhou, “d” indicates Chengdu, “e” indicates Hangzhou, and “f” indicates Wuhan).

4.4.1. The Differences in Direct Influence Path

(1) The direct influence of LCI

In the direct influence path of “LCI→LCLB”, there were significant differences among groups with different genders, ages, educational backgrounds, monthly incomes, and living conditions in Hangzhou and Wuhan, different genders, ages, educational backgrounds, and monthly incomes in Beijing, and different ages, genders, and living conditions in Chengdu. Among them, females in Beijing showed the most significant positive correlation, with a path coefficient of 0.548.

In the influence path of “LCI→LCCB”, residents of different groups in the six pilot cities had significant differences in transforming LCI into LCCB. The respondents with a monthly income ≤ 8000 RMB (1125.97 USD) in Hangzhou and aged ≤ 35 years in Beijing showed the most significant positive correlation, with path coefficients of 0.574 and 0.555, respectively.

(2) The direct influence of LCPP

In the direct influence path of “LCPP→LCLB”, there were significant differences among groups with different ages and genders in Beijing, different living conditions in Guangzhou, different genders, ages, and living conditions in Chengdu, and different monthly incomes in Wuhan. The female in Chengdu showed the most significant positive correlation, with a path coefficient of 0.416.

In the direct influence path of “LCPP→LCCB”, there were significant differences among groups with different genders, ages, educational backgrounds, and monthly incomes in Beijing, different genders and monthly incomes in Shanghai, different genders, ages, and living conditions in Chengdu, and all different groups in Guangzhou, Hangzhou, and Wuhan. The male in Shanghai showed the most significant positive correlation, with a path coefficient of 0.585.

(3) The direct influence of LCID

In the direct influence path of “LCID→LCLB”, there were significant differences among groups with different genders, educational backgrounds, and living conditions in Shanghai, different educational backgrounds in Guangzhou, different educational backgrounds and monthly incomes in Hangzhou, and different genders, ages, educational backgrounds, and living conditions in Wuhan. The respondents with a junior college degree or below in Shanghai showed the most significant positive correlation, and the path coefficient was 0.575.

In the direct influence path of “LCID→LCCB”, there were significant differences among groups with different genders, ages, educational backgrounds, and monthly incomes in Beijing; different genders, ages, educational backgrounds, monthly incomes, and living conditions in Guangzhou; and different ages, educational backgrounds, and monthly incomes in Hangzhou. Among them, respondents whose monthly income was ≤ 8000 RMB (1125.97 USD) in Guangzhou were the most significant, with a path coefficient of 0.441.

4.4.2. The Differences in Indirect Influence Path

(1) The indirect influence of LCPP

In the indirect influence path of “LCPP→LCI→LCLB”, there were significant differences among groups with different ages in Beijing, different genders, ages, and living conditions in Chengdu; different genders, ages, education levels, and living conditions in Hangzhou; and all groups in Wuhan. Among them, respondents aged > 35 years and with a junior college degree or below in Wuhan and living in a self-owned house in Chengdu showed a significant positive correlation, with total path coefficients of 0.922, 0887, and 0.880, respectively.

In the indirect influence path of “LCPP→LCI→LCCB”, there were significant differences among groups with different ages in Beijing; different genders, monthly incomes, and living conditions in Shanghai; different genders, ages, and educational backgrounds in Guangzhou; different genders, ages, and living conditions in Chengdu; and all groups in Hangzhou and Wuhan. Among them, respondents living in non-self-owned houses with a monthly income ≤ 8000 RMB (1125.97 USD) in Wuhan and aged ≤ 35 years in Chengdu showed the most significant positive correlation, and the total path coefficients were 0.897, 0.864, and 0.793, respectively.

(2) The indirect influence of LCID

In the indirect influence path of “LCID→LCI→LCLB”, there were significant differences among groups with different ages, educational backgrounds, and monthly incomes in Beijing and different genders, ages, educational backgrounds, monthly incomes, and living conditions in Hangzhou and Wuhan. Among them, respondents with a monthly income ≤ 8000 RMB (1125.97 USD) and living in non-self-owned houses in Hangzhou and aged > 35 years in Wuhan showed the most significant positive correlation, and the total path coefficients were 0.911, 0.731, and 0.735, respectively.

In the indirect influence path of “LCID→LCI→LCCB”, there were significant differences among groups with different ages, education levels, and monthly incomes in Beijing; different living conditions in Shanghai; and different genders, ages, education levels, monthly incomes, and living conditions in Hangzhou and Wuhan. Among them, respondents with a monthly income ≤ 8000 RMB (1125.97 USD) and living in non-self-owned houses in Hangzhou and the group with an age of > 35 in Wuhan showed the most significant positive correlations, and the total path coefficients were 0.897, 0.864, and 0.793, respectively.

5. Discussion and Policy Implications

5.1. Discussion

Throughout the investigation, we found that there were significant differences in the low-carbon intentions and LCBs of residents in different pilot cities. Residents in Hangzhou and Chengdu were outstanding in LCI, especially in choosing or using energy-saving products and houses with low-carbon and energy-saving designs. Residents in Beijing and Chengdu showed a high motivation for low-carbon living, especially in turning off lights and electrical appliances and setting the temperature of air conditioners, while residents in Hangzhou paid more attention to energy conservation when buying daily necessities and cars. However, the residents in Wuhan and Guangzhou had a relatively low level of LCI and low-carbon action, which means that the governments of Wuhan and Guangzhou still need to make great efforts to push residents to implement LCB. These differences might be caused by the inconsistency in the social, economic, and low-carbon policy backgrounds of various cities. From the perspective of social and economic background, Beijing and Shanghai, as the leading economic hubs in China, have residents with relatively high-income levels, strong consumption capabilities, and high demands for quality of life. Beijing has numerous innovative enterprises in high-tech fields such as new energy, energy conservation, and environmental protection, while Shanghai has significant advantages in green finance and other aspects. New undertakings, such as those through the Internet in Hangzhou, are developing rapidly. When residents go online, it is relatively easier for them to come into contact with and spread the concept of low-carbon behavior. The relaxed living atmosphere and rich and diverse social activities in Chengdu have promoted close connections and frequent interactions among residents, which also provides a context for the dissemination of the low-carbon concept. The implementation intensity and effect of low-carbon policies also vary among different cities. In recent years, the Hangzhou government has issued relevant documents, proposing to intensively carry out the creation of green living action, expand the certification of green and low-carbon products, explore the establishment of green product procurement incentive measures, and guide residents to purchase and use green and low-carbon products. The implementation of these policy measures may have played a positive role in enhancing residents’ acceptance and willingness to purchase low-carbon products. The strict environmental protection regulations and regulatory measures formulated by the Beijing government may have effectively ensured the implementation of low-carbon policies such as carbon emission trading and the promotion of green buildings. The Shanghai government is actively exploring a low-carbon development model in line with international standards and is integrating domestic waste classification with community governance and the construction of a “waste-free city” with the goal of creating a “new fashion of low-carbon life”. In contrast, the low-carbon policies in Wuhan and Guangzhou still have some deficiencies in the implementation process, and there is relatively less low-carbon guidance for residents’ lives.

Based on the structural equation model, we further explored the influence path of LCB for residents in China’s pilot cities. LCI, LCPP, LCID, LCLB, and LCCB constitute an interrelated system, and the LCI, LCPP, and LCID jointly promote the formation of residents’ LCB. In addition, groups with different genders, ages, educational backgrounds, monthly incomes, and living conditions showed significant differences in their influence paths. Other related studies have also pointed out that factors such as publicity and education, and social relationships can directly and indirectly affect residents’ LCB. There are differences in LCB among people of different genders, ages, educational levels, and incomes [22,38]. A relevant study has found that external factors such as social norms have different effects on LCB in different age groups in Beijing, and our findings are consistent with this [29]. LCI played a key role in promoting LCLB and LCCB, especially the positive correlation between LCI and LCCB, which showed a significant positive correlation in all cities. In addition, the empirical results also confirmed that LCPP and LCID had an important influence on residents’ LCI and LCB. LCI embodies residents’ values on sustainable development and environmental protection. As environmental consciousness grows stronger, residents begin to realize that their behavior will have a certain influence on environmental quality, and this understanding prompts residents to regard LCB as a due environmental responsibility. Based on this sense of environmental responsibility in daily life, residents may be more likely to consciously implement various low-carbon practices to support environmental protection with practical actions [19]. When low-carbon policies are communicated to the public in a clear and easy-to-understand manner, residents can more clearly understand their purpose and implementation requirements, and the incentive mechanism contained in the policy can effectively motivate residents to make environmentally friendly low-carbon choices in their consumption and living practices, and the binding regulations in the policy can effectively guide public behaviors to shift in a low-carbon direction [18]. Information dissemination is a key method of policy advocacy. With the popularization of social media, low-carbon information has become more accessible and shared, which has contributed to LCB becoming a widely accepted standard in society. Related research confirmed that the demonstration effect of people around them has a significant impact on residents’ low-carbon behaviors [45]. The conclusion of this study further confirms that amplifying the exemplary role of public figures and community leaders through media and social platforms can further stimulate the imitative effect among residents, which is conducive to consolidating residents’ willingness to adopt low-carbon behaviors and preventing their regression [18,46]. Policymakers should fully consider the interaction of these factors and formulate comprehensive strategies to effectively guide and motivate the public to engage in a low-carbon life and jointly promote the sustainable development and low-carbon transformation of society.

5.2. Policy Implications

Based on the above analysis, we put forward targeted suggestions to improve residents’ LCB. Compared with other pilot cities, Hangzhou and Chengdu have achieved remarkable results in designing and promoting low-carbon policies, and residents have a higher LCI. Policymakers should fully use the existing policy foundation to consolidate residents’ LCB practice through precise policy incentives and differentiated guidance, and promote social low-carbon transformation and sustainable development.

The Hangzhou government should continue to promote the green life initiative, expand the supply of low-carbon products, vigorously promote green product certification, and explore the establishment of incentives for the sale and purchase of green products. In addition, relevant departments should actively promote energy-saving equipment such as smart meters, smart thermostats, and smart garbage sorting recycling boxes in community construction to create a low-carbon and high-quality living environment for residents in Hangzhou. Relevant studies suggest that policymakers and enterprises should pay attention to using tools such as social media to promote marketing strategies in order to publicly share users’ positive experiences of low-carbon products and attract more low-carbon consumption [47]. The results of this study show that the motivation to transform low-carbon willingness into action among men and highly educated and high-income groups in Chengdu needs to be further stimulated. We also suggest that a social communication effect of low-carbon living can be formed through online sharing based on the public’s reliance on social media. In addition, intelligent software should be developed to set up personal carbon accounts for residents, which can be used to monitor their carbon emissions in household electricity consumption, green travel, garbage classification, and other aspects in real-time, and display residents’ energy-saving effects through visual data to enhance the sense of accomplishment and feedback experience of LCB.

Residents in Beijing and Shanghai show a moderate level of LCI and LCB on the whole, and the low-carbon potential of different groups still needs to be further tapped. As the capital of China, Beijing must fully utilize its leadership position to enhance the dissemination and advocacy of low-carbon initiatives and comprehensively enhance residents’ LCPP by relying on traditional media and new media platforms to build the city image of “green capital”. Since low-income groups in Beijing were not sensitive to LCPP, the government should implement measures such as an energy-saving equipment subsidy program and a low-carbon family support fund to encourage this group to take the initiative on LCB and stimulate the vitality of the green consumption of citizens. As an international metropolis with a large floating population, an energy-saving leasing plan could be introduced by the government of Shanghai to provide leasing subsidies for energy-saving home appliances, attract tenants to choose low-carbon lifestyles, and support landlords to carry out low-carbon transformations of houses through preferential subsidy policies. Young people in Shanghai have a strong low-carbon awareness and a high acceptance of new technologies. The government should leverage the leadership of the younger generation and hold activities such as “low-carbon Life Festival” and “Green Consumption Week” based on the positioning of international cities to introduce international advanced green products and show the convenience and high-quality of high-end low-carbon products, and guide citizens to transition from high-carbon consumption to green consumption.

Residents in Wuhan and Guangzhou have not yet formed effective cognition and feedback on low-carbon policies. The communication power and interaction of policies should be further strengthened, and the market guidance and mechanism innovation should be optimized to promote the continuous expansion of low-carbon consumption, and a low-carbon social atmosphere should be created through diversified communication means and interactive activities. In terms of promoting LCCB, the government should further optimize the green consumption subsidy policy to reduce the participation cost of low-carbon life, simplify the application process, launch a series of activities such as “energy-saving electrical appliances consumption season”, and further promote high-income groups to become leaders in low-carbon consumption. In terms of enhancing residents’ sense of identity with low-carbon policies, relevant organizations should carry out low-carbon policy publicity activities and resident satisfaction survey activities through public places, in combination with the characteristics of different groups, and use data and cases to demonstrate the actual effects of policies. In addition, the opinions and suggestions of different groups on policy implementation should be listened to in order to timely optimize the policy content and implementation path, ensure that low-carbon policies are more in line with real needs, and enhance residents’ perception of and interaction with low-carbon policies. In terms of creating a low-carbon atmosphere, measures such as establishing a low-carbon cultural corridor in public places to display low-carbon models and low-carbon knowledge should be adopted to guide residents to establish and cultivate low-carbon awareness and behavioral habits, and the core content and actual benefits of low-carbon policies should be interpreted through multi-channel and multi-level information dissemination. In addition, green offices and low-carbon supply chains should be actively promoted in the enterprise management process to fulfill low-carbon responsibilities.

6. Conclusions and Prospects

Based on the structural equation model, we explored the influence paths and group differences in residents’ LCI and LCB in six pilot cities of China from the perspective of LCPP and LCID. The main research conclusions are as follows:

(1) Residents of different pilot cities significantly differed between LCI and LCB. Residents in Hangzhou and Chengdu had high LCI and LCB, while residents in Wuhan and Guangzhou had relatively low levels, which meant that Wuhan and Guangzhou still need to make great efforts in promoting residents’ LCB. LCI was the core driving force that promoted residents’ LCB, and Beijing residents were more inclined to convert LCI into LCB.

(2) LCPP and LCID had an important influence on residents’ LCI and LCB, and there were differences among different pilot cities. In the path of “LCPP→LCLB”, residents in Chengdu and Wuhan showed a direct positive correlation in both direct and indirect influence. In the path of “LCPP→LCCB”, all other urban residents except Guangzhou showed significant direct and indirect influences, among which Chengdu had the strongest indirect influence, with a total path coefficient of 0.703. In the path of “LCID→LCLB”, residents in Wuhan showed a significant positive correlation in both direct and indirect influences. In the path of “LCID→LCCB”, residents in Hangzhou showed a significant positive correlation in both direct and indirect influences, and the total path coefficient of indirect influences was 0.672.

(3) Groups with different demographic characteristics had significant differences in the influence paths of residents’ LCB. In the direct influence path, residents with a monthly income ≤ 8000 RMB (1125.97 USD) in Hangzhou and females in Beijing showed a significant positive correlation in the direct path of transforming LCI into LCB (path coefficients were 0.574 and 0.548, respectively). Females in Chengdu and males in Shanghai showed a significant positive correlation in the direct path of transforming LCPP into LCB (path coefficients were 0.416 and 0.585, respectively). Residents with a junior college degree or below in Shanghai and with a monthly income ≤ 8000 RMB in Guangzhou showed a significant positive correlation in the direct path of transforming LCID into LCB (path coefficients were 0.575 and 0.441, respectively). In the indirect influence path, residents aged > 35 years and living in non-self-owned houses in Wuhan showed a significant positive correlation in the indirect path of “LCPP→LCI→LCB” with total path coefficients of 0.922 and 0.897, respectively. Residents with a monthly income ≤ 8000 RMB (1125.97 USD) and aged ≤ 35 years in Hangzhou showed a significant positive correlation in the indirect path of “LCID→LCI→LCB” with total path coefficients of 0.911 and 0.731, respectively. Based on the empirical analysis results and the positioning of urban development, we suggested that policymakers should develop pertinent policies based on full consideration of the differences between different regions and different groups to effectively guide and motivate the public to participate in low-carbon lifestyles and collaboratively advance the sustainable growth of society.

This research has made significant contributions both in theory and practice. Theoretically, by integrating the dual perspectives of policy perception and information dissemination, a comprehensive analysis framework for the influence path of LCB has been constructed. The three-dimensional measurement system of policy perception (policy familiarity, environmental benefits, and economic usefulness) and the three-dimensional measurement system of low-carbon information dissemination (interpersonal communication, media communication, and publicity frequency) proposed in this study have enriched the analytical framework and perspective for the research on residents’ LCB, providing reference value for subsequent studies. On the practical level, this study clarified the influence paths and differences in different pilot cities on residents’ LCB in terms of policy perception and information dissemination through empirical analysis, which provided a scientific basis for policymakers and helped pilot cities to carry out low-carbon city construction and publicity in a more targeted way. In future research prospects, we will expand the sample scope to residents in cities with low economic development levels or non-low-carbon pilots to carry out a more comprehensive survey, and LCB will include transportation, housing, and other aspects to explore the commonalities and differences in residents’ LCB in China in different social backgrounds. The binary gender classification used in the questionnaire of this study neglects gender-diverse populations. In future research, more inclusive gender classification methods will be explored to more comprehensively analyze the differences in LCB among participants from different gender groups. In addition, relevant studies have shown that price changes in low-carbon products and subsidy incentives closely related to residents’ interests may also impact residents’ LCB. So, in the future, we will continue to track residents’ LCB and further explore the dynamic impact of price changes and other factors on Chinese residents’ LCB in a more in-depth and detailed manner by combining scenario simulation technology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C. (Yi Chen); investigation, Y.C. (Yi Chen); data curation, Y.C. (Yi Chen); methodology, Y.C. (Yi Chen); software, Y.C. (Yi Chen); visualization, Y.C. (Yi Chen); writing—original draft preparation, Y.C. (Yi Chen); writing—review and editing, Y.C. (Yinrong Chen); supervision, Y.C. (Yinrong Chen); funding acquisition, Y.C. (Yinrong Chen). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 42271270).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Huazhong Agricultural University (protocol code HZAUHU-2025-0105, approval date: 5 July 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LCB | Low-carbon behavior |

| LCLB | Low-carbon living behavior |

| LCCB | Low-carbon consumption behavior |

| LCPP | Low-carbon policy perception |

| LCID | Low-carbon information dissemination |

| LCI | Low-carbon intention |

References

- Li, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, L. Forecasting carbon emissions peak in Chinese household consumption and selecting low-carbon development strategies: A study based on the extended SPIRPAT model. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2025, 44, e14537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; Sheng, N.; Song, Q.; Yuan, W.; Li, J. Empirical evidence on the characteristics and influencing factors of carbon emissions from household appliances operation in the Pearl River Delta region, China. Appl. Energy 2024, 376, 124191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cai, H.; Chen, Y. Spatial correlation and interaction effect intensity between territorial spatial ecological quality and new urbanization level in Nanchang metropolitan area, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 156, 111163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Huang, S.; Wang, T.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Gao, W. The Influencing Factors and Future Development of Energy Consumption and Carbon Emissions in Urban Households: A Review of China’s Experience. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Jiang, X.; Liu, Z.; Long, R.; Xu, Z.; Cao, Q. Factors affecting low-carbon consumption behavior of urban residents: A comprehensive review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 132, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Liu, H. Research on energy conservation and carbon emission reduction effects and mechanism: Quasi-experimental evidence from China. Energy Policy 2022, 169, 113180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Huang, Y.; Wu, S.; Hu, S. Does “low-carbon city” accelerate urban innovation? Evidence from China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 83, 103954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, I.H.; Chiu, A.S.F.; Gandajaya, L. Impact of subsidy policies on green products with consideration of consumer behaviors: Subsidy for firms or consumers? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 173, 105669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Shen, B.; Springer, C.H.; Hou, J. What prevents us from taking low-carbon actions? A comprehensive review of influencing factors affecting low-carbon behaviors. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 71, 101844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, C.; Wei, S.; Zhang, Q.; Rehman, A.; Shah, A. Characteristics and Evolution of China’s Carbon Emission Reduction Measures: Leading Towards Environmental Sustainability. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 924887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bai, X.; Mills, F.P. Characterizing energy-related occupant behavior in residential buildings: Evidence from a survey in Beijing, China. Energy Build. 2020, 214, 109823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElHaffar, G.; Durif, F.; Dubé, L. Towards closing the attitude-intention-behavior gap in green consumption: A narrative review of the literature and an overview of future research directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 122556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindén, A.-L.; Carlsson-Kanyama, A.; Eriksson, B. Efficient and inefficient aspects of residential energy behaviour: What are the policy instruments for change? Energy Policy 2006, 34, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Wang, B. Policy cognition is more effective than step tariff in promoting electricity saving behaviour of residents. Energy Policy 2020, 139, 111338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Lan, T. Progress of increasing-block electricity pricing policy implementation in China’s first-tier cities and the impact of resident policy perception. Energy Policy 2023, 177, 113544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Guo, J.; Wei, C. Impact of information feedback on residential electricity demand in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 125, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Chen, H.; Long, R.; Yang, J. The impact of different regulation policies on promoting green consumption behavior based on social network modeling. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 32, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-W.; Cao, Y.-M.; Zhang, N. The influences of incentive policy perceptions and consumer social attributes on battery electric vehicle purchase intentions. Energy Policy 2021, 151, 112163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Gong, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y. Effects of monetary and nonmonetary incentives in Individual Low-carbon Behavior Rewarding System on recycling behaviors: The role of perceived environmental responsibility. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 38, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, L.; Gan, X.; Sun, Y.; Lv, T.; Qiao, L.; Xu, T. Effects of monetary and nonmonetary interventions on energy conservation: A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 149, 111342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chu, Z.; Gu, W. Participate or not: Impact of information intervention on residents’ willingness of sorting municipal solid waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 318, 128591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, P.; Shen, L.; He, H. Low-carbon behavior between urban and rural residents in China: An online survey study. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 46, 690–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Shi, S. Social interaction and the formation of residents′ low-carbon consumption behaviors: An embeddedness perspective. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Chen, H.; Long, R.; Zhang, L.; Feng, Q. Maturity of residents’ low-carbon consumption and information intervention policy. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 124080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Tian, L.; Batool, H. Impact of negative information diffusion on green behavior adoption. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 136, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.; Lu, Q.; Tong, X. How to improve the consistency of consumers’ food waste reduction intentions and behaviors? An analysis based on the expanded Motivation–Opportunity–Ability framework. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, F.; Dewitte, S. Measuring pro-environmental behavior: Review and recommendations. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 63, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Duan, W.; Zhao, D.; Song, Q. Identifying the influence factors of residents’ low-carbon behavior under the background of “Carbon Neutrality”: An empirical study of Qingdao city, China. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 6876–6886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhan, J.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Chu, X.; Liu, W.; Teng, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y. Multi-group analysis on the mechanism of residents’ low-carbon behaviors in Beijing, China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 183, 121956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Li, L.; Yang, R. Understanding household electricity-saving behavior: Exploring the effects of perception and cognition factors. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, X.; Bu, W.; Li, L. How to design renewable energy support policies with imperfect carbon pricing? Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 958979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Yu, J.; Zhang, H.; Guo, J.; Zhang, X. How does social support affect the retention willingness of cross-border e-commerce sellers? Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 797035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Ge, J. Electric vehicle development in Beijing: An analysis of consumer purchase intention. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 216, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, M.; Xu, L. Relationships between personal values, micro-contextual factors and residents’ pro-environmental behaviors: An explorative study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 156, 104697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Lin, L.M. Exploring attitude–behavior gap in sustainable consumption: Comparison of recycled and upcycled fashion products. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Li, G. Determinants of energy-saving behavioral intention among residents in Beijing: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2014, 6, 053127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Li, J. Who are the low-carbon activists? Analysis of the influence mechanism and group characteristics of low-carbon behavior in Tianjin, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 683, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Guo, D. Policy implications of the purchasing intentions towards energy-efficient appliances among China’s urban residents: Do subsidies work? Energy Policy 2017, 102, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, S. Environmental concern, attitude toward frugality, and ease of behavior as determinants of pro-environmental behavior intentions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, M.J.; Rau, H.; Fahy, F. Different shades of green? Unpacking habitual and occasional pro-environmental behavior. Glob. Environ. Change 2015, 35, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Long, R.; Wu, F.; Geng, J.; Yang, J. How social interaction shapes habitual and occasional low-carbon consumption behaviors: Evidence from ten cities in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 182, 113387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, J. Evaluation of low carbon city pilot policy effect on carbon abatement in China: An empirical evidence based on time-varying DID model. Cities 2022, 123, 103582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.W. Impact of competitiveness on salespeople’s commitment and performance. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1328–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.C.; Wu, C.G.; Lee, C.S.; Pham, T.T.T. Factors affecting the behavioral intention to adopt mobile banking: An international comparison. Technol. Soc. 2020, 63, 101360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhu, J.; Yang, L.; Shi, W.; Qiu, L.; Wu, S.; Qin, Y. Differential Analysis of Carbon Emission Reduction Potential on the Consumption Side Based on the Willingness of Family Lifestyle Transformation. Environ. Sci. 2024, 11, 6422–6432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bai, X.; Mills, F.P.; Pezzey, J.C.V. Examining the attitude-behavior gap in residential energy use: Empirical evidence from a large-scale survey in Beijing, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habich-Sobiegalla, S.; Kostka, G.; Anzinger, N. Citizens’ electric vehicle purchase intentions in China: An analysis of micro-level and macro-level factors. Transp. Policy 2019, 79, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).