Waste Polypropylene in Asphalt Pavements: A State-of-the-Art Review Toward Circular Economy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Characteristics and Recycling Methods of WPP

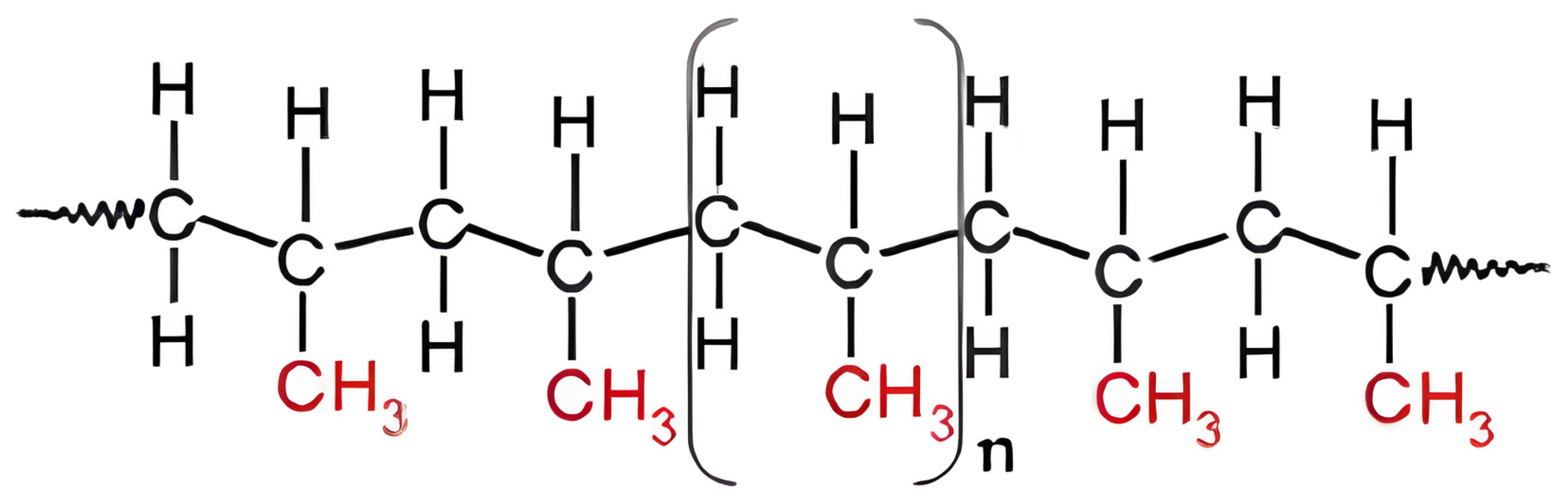

2.1. Main Characteristics of Original PP

2.2. Main Recycling Methods for WPP

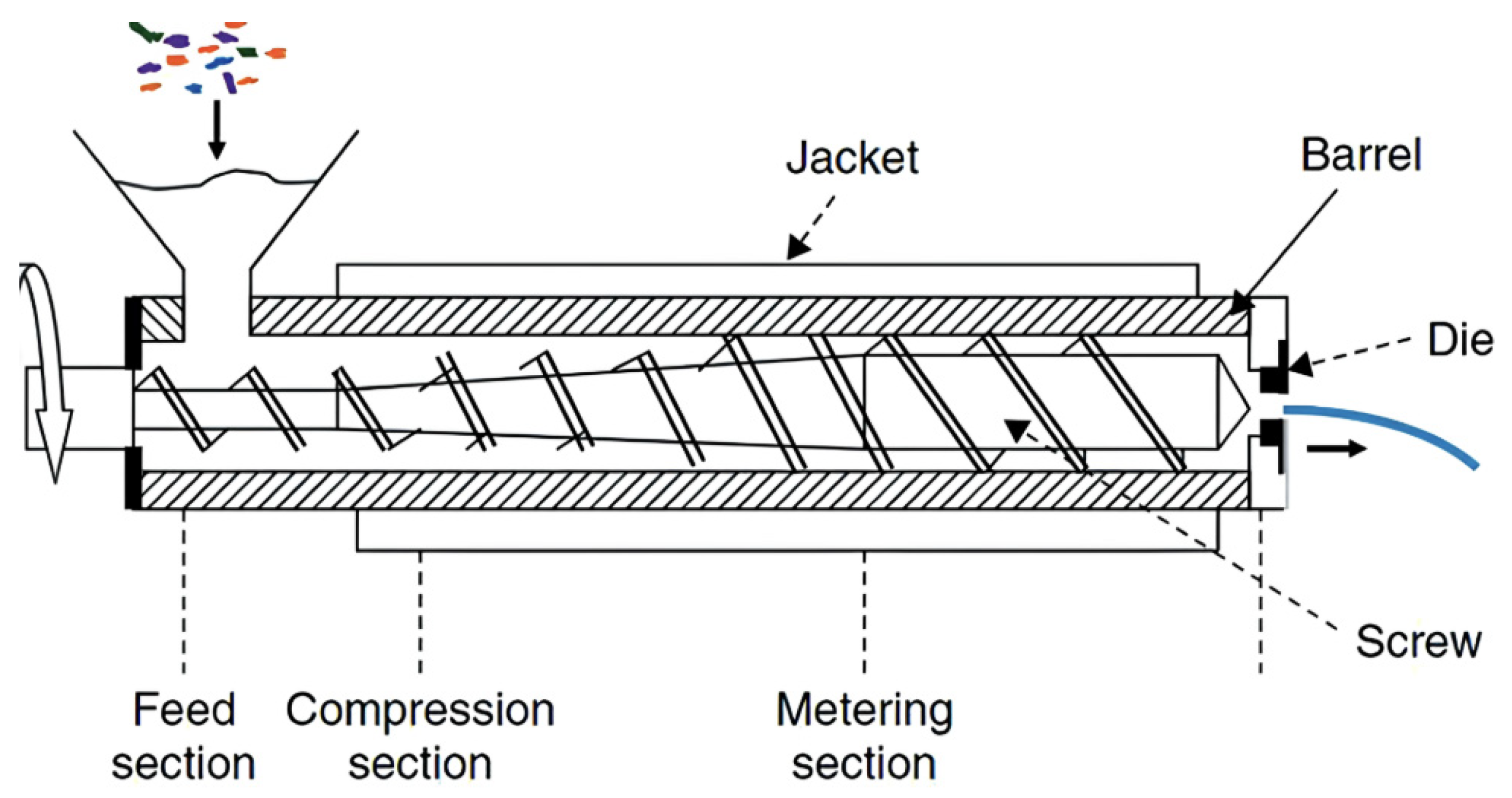

2.2.1. Mechanical Recycling

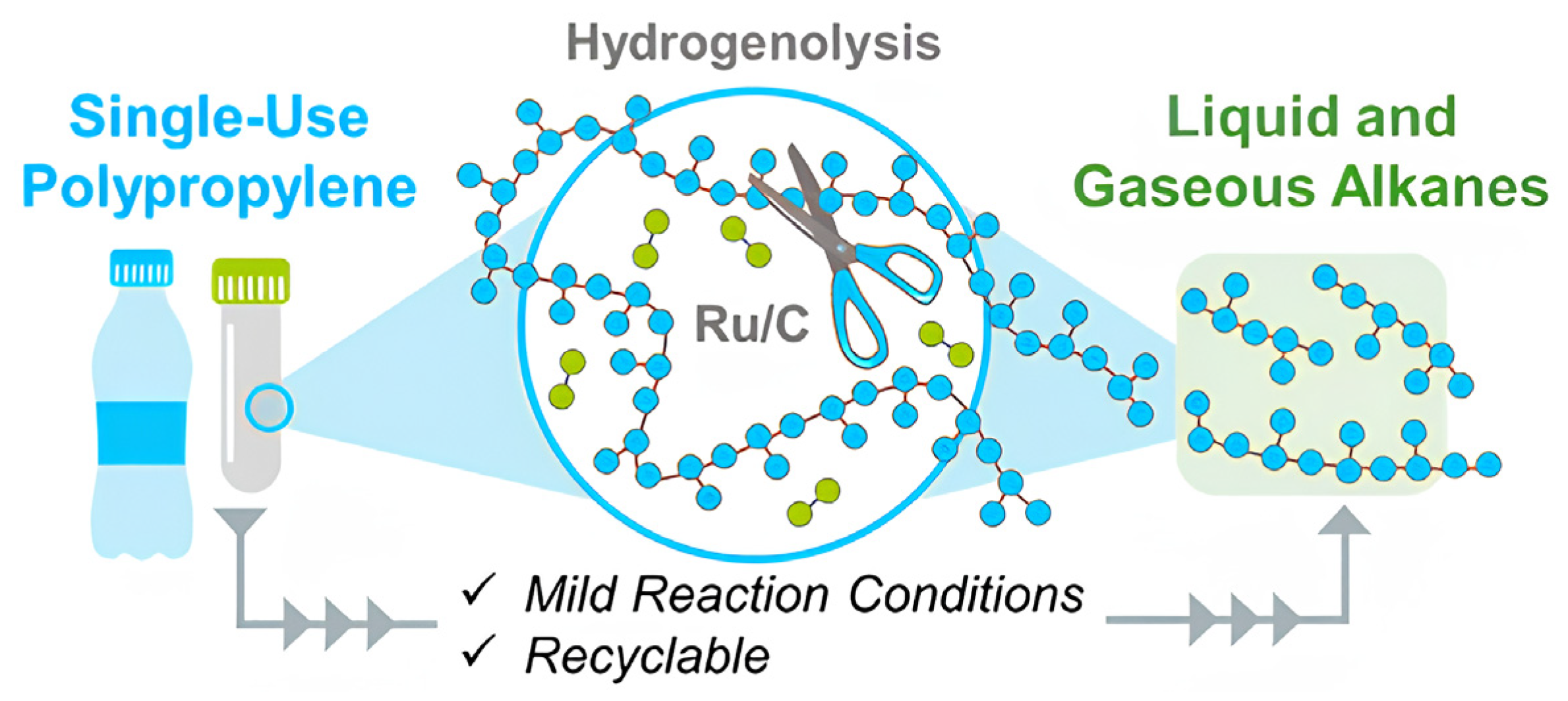

2.2.2. Chemical Recycling

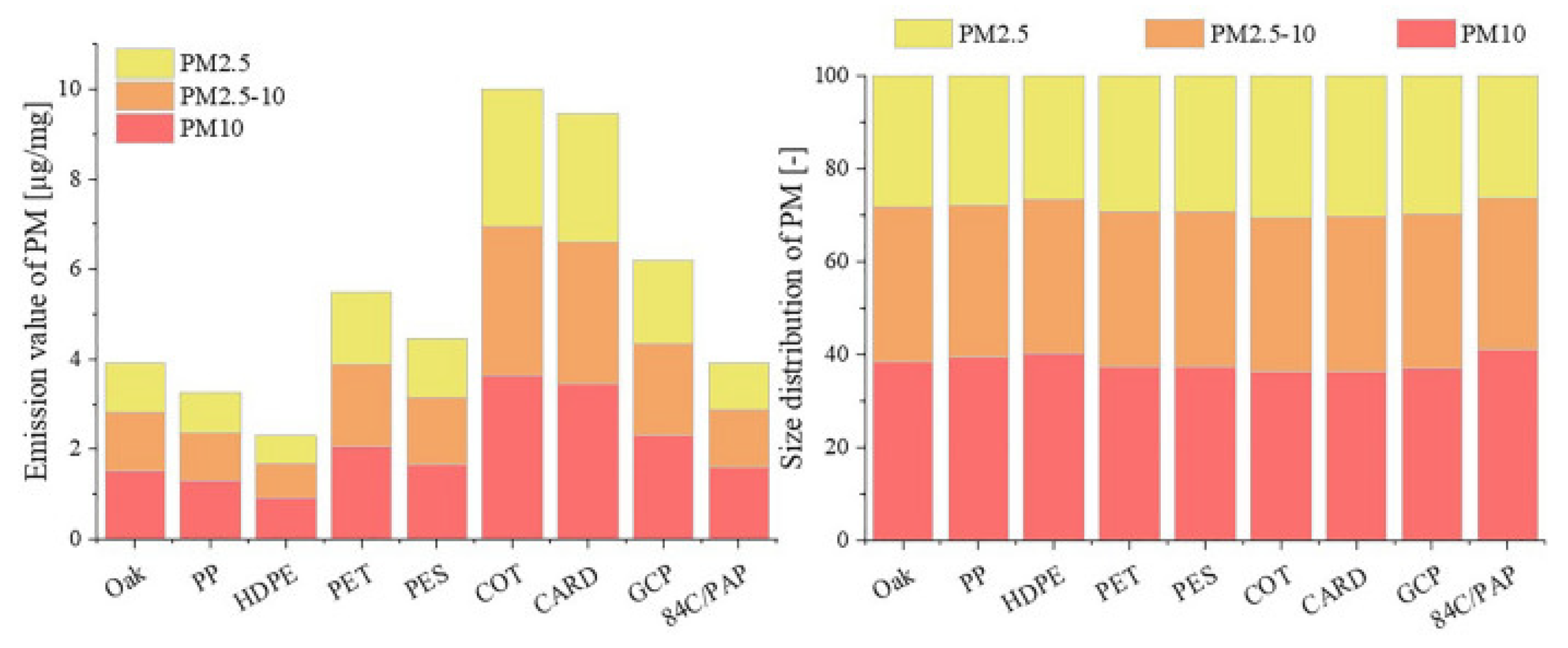

2.2.3. Energy Recovery

3. Research Progress on WPP-Modified Asphalt Binders

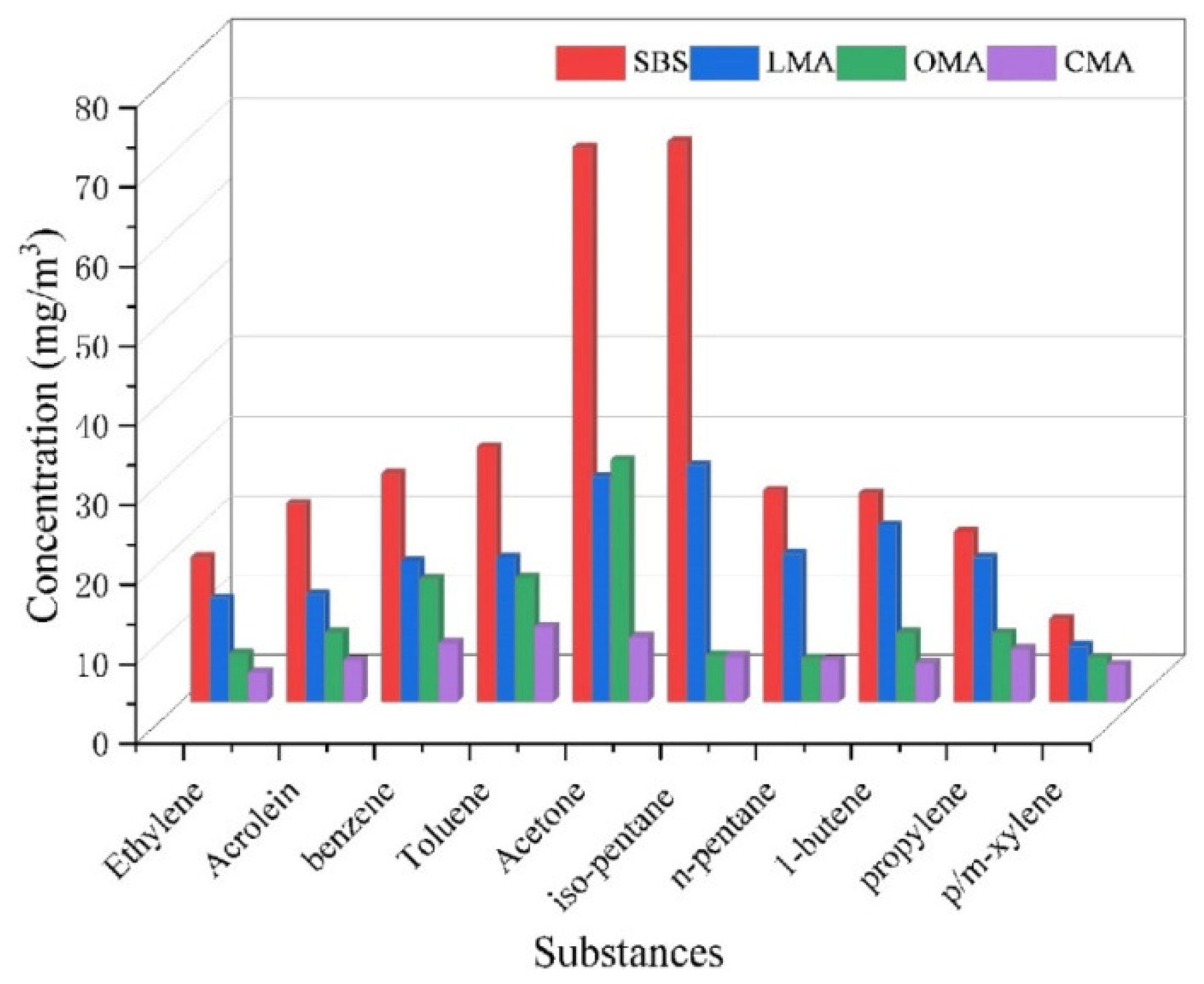

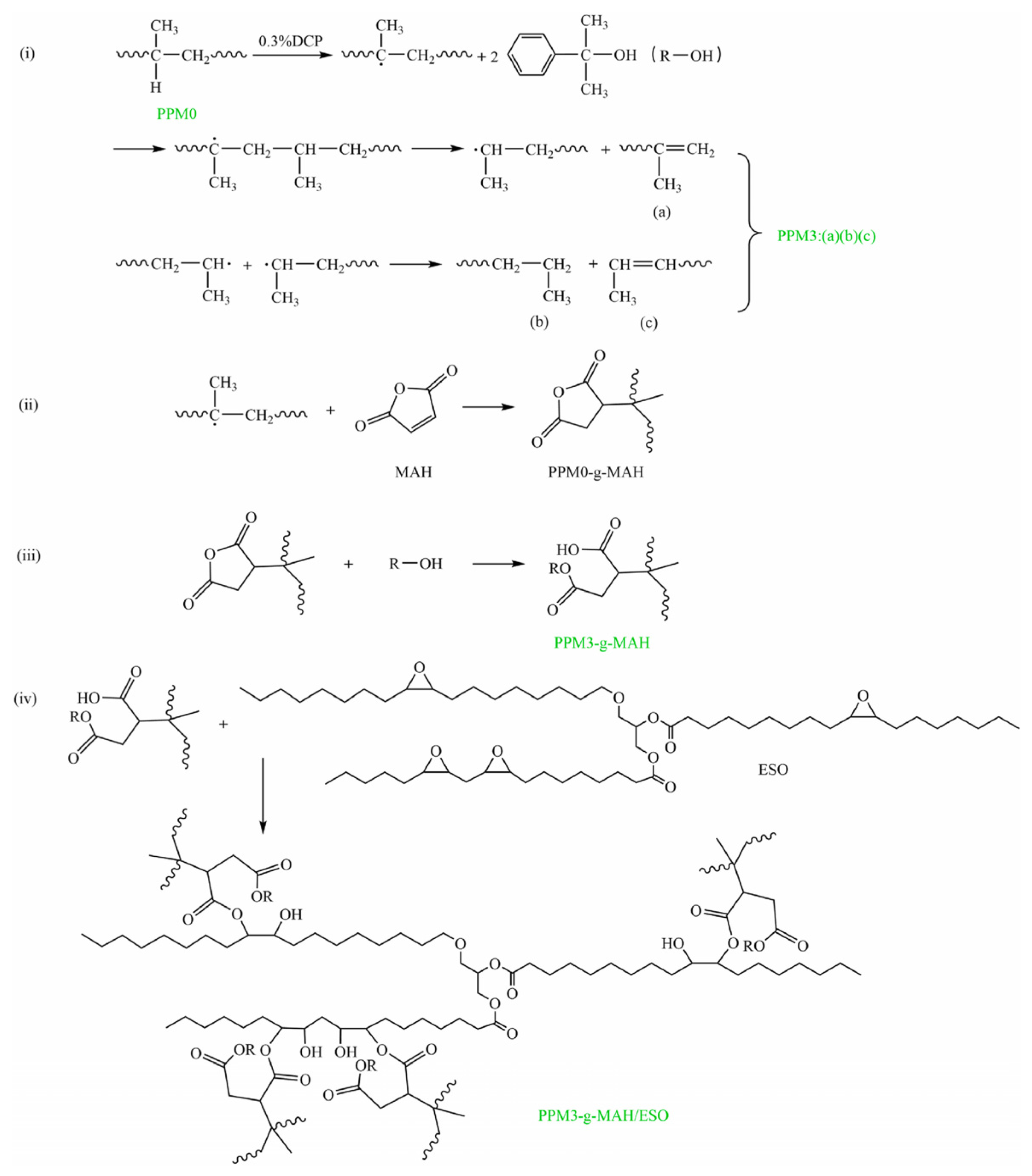

3.1. Pretreatment of WPP-Based Asphalt Modifiers

3.2. Performance and Application of WPP in Asphalt Binders

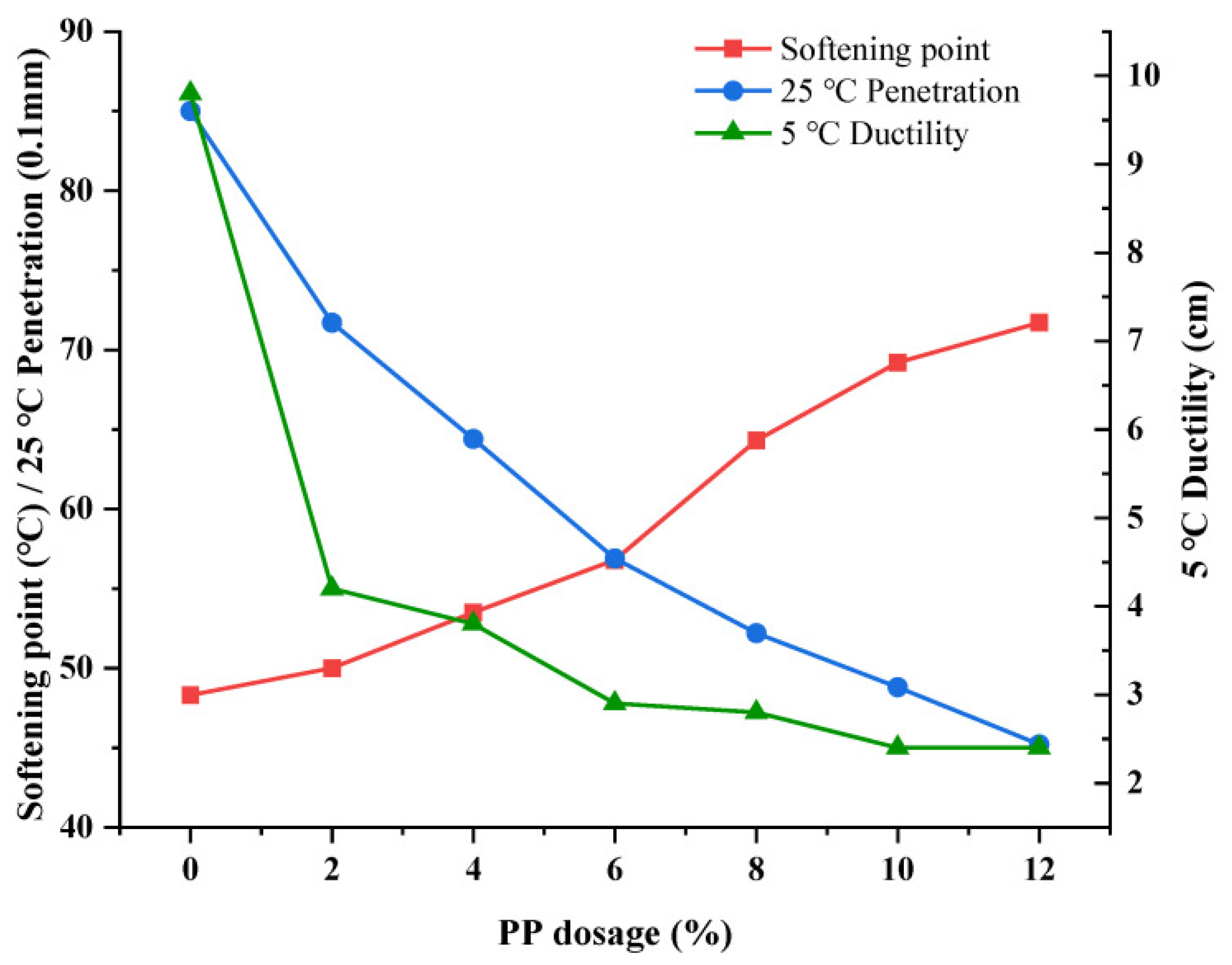

3.2.1. Softening Point and Penetration of WPP-Modified Asphalt

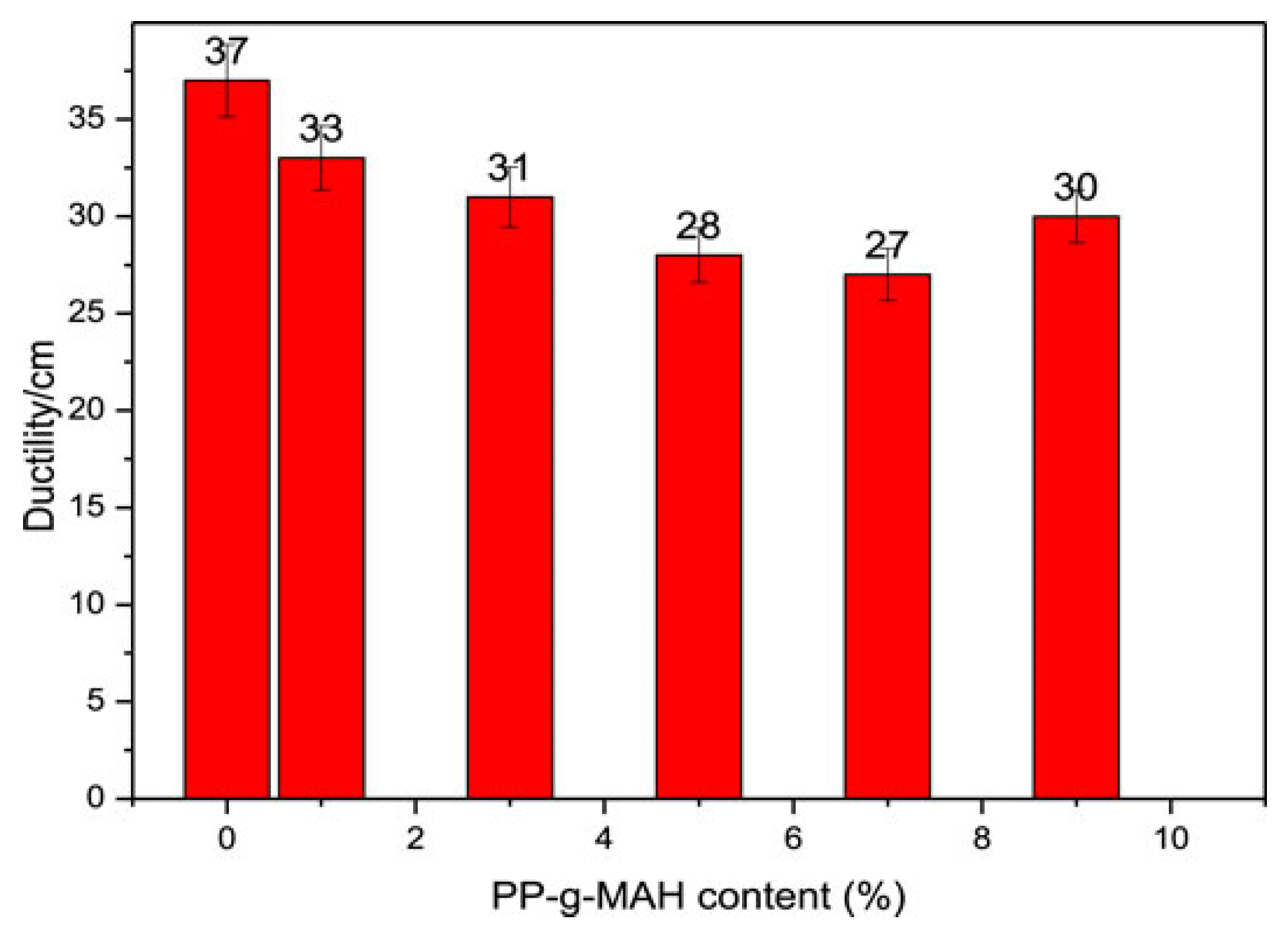

3.2.2. Ductility of WPP-Modified Asphalt

3.2.3. Storage Stability and Compatibility of WPP-Modified Asphalt

3.2.4. Viscosity and Rheological Properties of WPP-Modified Asphalt

4. Performance Study of WPP-Modified Asphalt Mixtures

4.1. Preparation Methods and Process of WPP-Modified Asphalt Mixtures

4.2. Performance Evaluation of WPP-Modified Asphalt Mixtures

4.2.1. Moisture Damage Resistance

4.2.2. Low-Temperature Performance

4.2.3. High-Temperature Performance

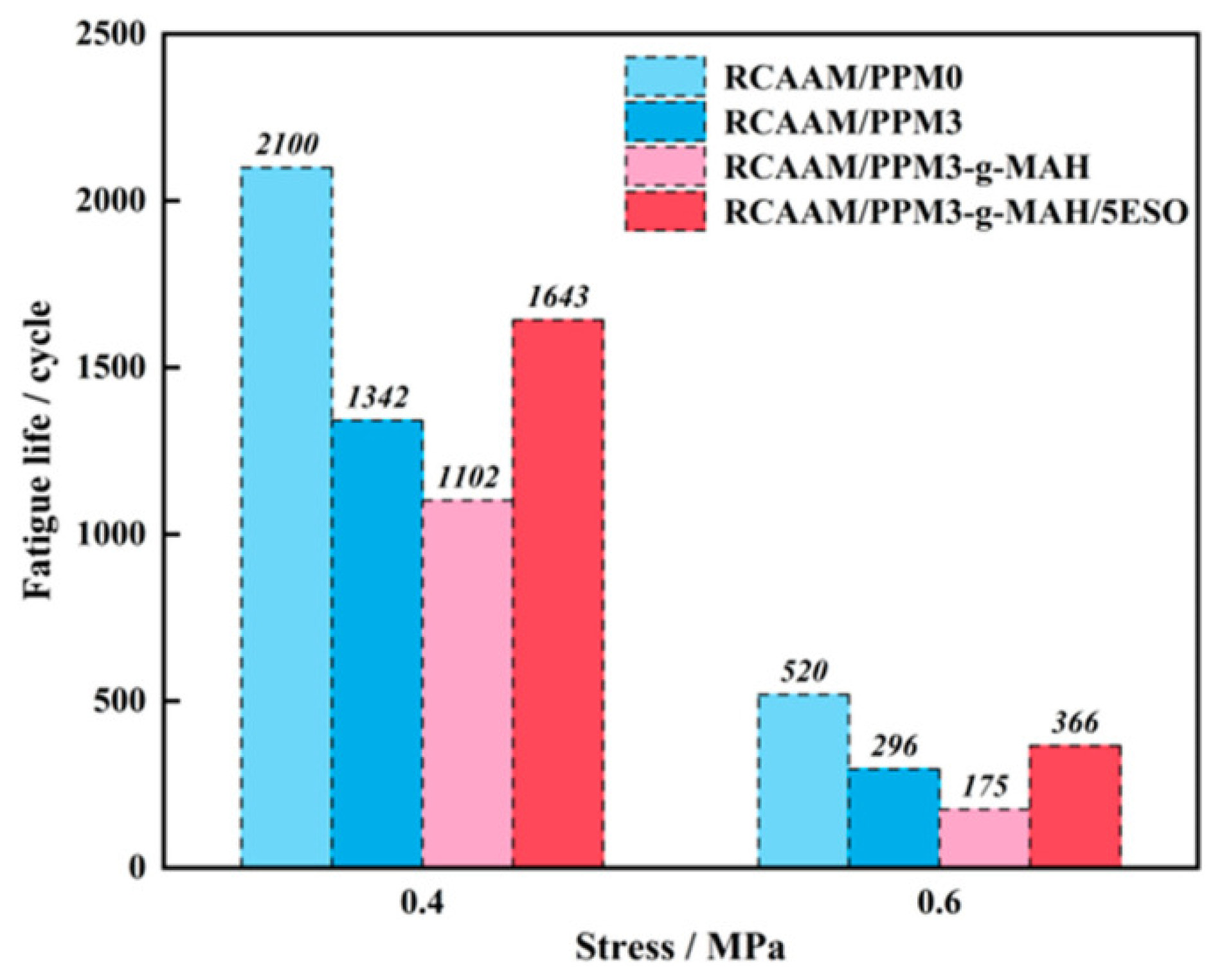

4.2.4. Fatigue Performance

5. Summary and Recommendations

- From the viewpoints of material properties and recycling, WPP demonstrates outstanding mechanical strength, heat resistance, and chemical stability; however, its high crystallinity and hydrophobic nature restrict its natural degradability. While mechanical recycling remains the primary method due to its established efficiency and scalability, emerging techniques such as chemical recycling and thermo-mechanochemical upcycling offer promising potential for converting WPP into valuable functional additives for asphalt modification.

- From modification and performance enhancement, the addition of WPP to asphalt binders improves high-temperature performance, softening point, and rutting resistance but also increases viscosity and reduces low-temperature ductility. These adverse effects can be mitigated by incorporating compatibilizers like PP-g-MAH, reactive additives, or elastomeric polymers including SBS or crumb rubber to achieve balanced rheological and mechanical properties.

- The mixture performance indicated that the incorporation of a moderate and well-dispersed amount of WPP in asphalt mixtures can effectively enhance high-temperature stability and moisture resistance by improving hydrophobicity and interfacial bonding. However, excessive WPP content or poor dispersion may lead to increased stiffness and reduced crack resistance at low temperatures, emphasizing the importance of optimizing both dosage and dispersion for balanced performance.

- New emerging technologies such as thermo-mechanochemical and catalytic degradation present promising approaches for transforming waste PP into warm-mix additives with lower viscosity, reduced emissions, and improved compatibility. These innovations support the advancement of cleaner production practices and promote the realization of a circular economy within the pavement industry.

- Future research should focus on developing multi-scale models that integrate molecular dynamics simulations with experimental validation to better understand WPP–asphalt interaction mechanisms, optimizing pretreatment and blending techniques to lower energy consumption and improve storage stability, conducting comprehensive life cycle assessments (LCA) to evaluate environmental and economic benefits, and advancing standardization and field validation to facilitate large-scale engineering applications.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, X.; Chu, Y.; Chen, R.; Wu, Q.; Chen, X.; Zou, F.; Peng, C. Thermo-mechanochemical recycling of waste polypropylene into degradation products as modifiers for cleaner production and properties enhancement of bitumen. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379, 134792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Yang, Z.; You, Z.; Luo, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, L. Laboratory investigation of traffic effect on the long-term skid resistance of asphalt pavements. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 401, 132642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, J.; Jin, H.; Guo, L. Current research progress of physical and biological methods for disposing waste plastics. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 408, 137199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Dong, Y.; Chen, J. Preparation and road performance of solvent-based cold patch asphalt mixture. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2022, 15, 1155–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddah, H.A. Polypropylene as a Promising Plastic: A Review. Am. J. Polym. Sci. 2016, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Salem, S.M.; Lettieri, P.; Baeyens, J. Recycling and recovery routes of plastic solid waste (PSW): A review. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 2625–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrady, A.L.; Neal, M.A. Applications and societal benefits of plastics. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 1977–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquini, D.; de Morais Teixeira, E.; Curvelo, A.A.S.; Belgacem, M.N.; Dufresne, A. Surface esterification of cellulose fibres: Processing and characterisation of low-density polyethylene/cellulose fibres composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2010, 70, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragaert, K.; Delva, L.; Van Geem, K. Mechanical and chemical recycling of solid plastic waste. Waste Manag. 2017, 69, 24–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.C.; Swan, S.H.; Moore, C.J.; Vom Saal, F.S. Our plastic age. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 1973–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Global Plastics Outlook: Economic Drivers, Environmental Impacts and Policy Options; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Achillas, D.S.; Roupakias, C.; Megalokonomos, P.; Lappas, A.; Antonakou, E.V. Chemical recycling of plastic wastes made from polyethylene (LDPE and HDPE) and polypropylene (PP). J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 149, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulas, D.G.; Zolghadr, A.; Chaudhari, U.S.; Shonnard, D.R. Economic and environmental analysis of plastics pyrolysis after secondary sortation of mixed plastic waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 384, 135542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Leng, Z.; Lan, J.; Wang, W.; Yu, J.; Bai, Y.; Sreeram, A.; Hu, J. Sustainable practice in pavement engineering through value-added collective recycling of waste plastic and waste tyre rubber. Engineering 2021, 7, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, A.; García, J.M. Chemical recycling of waste plastics for new materials production. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017, 1, 0046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, H. Thermal-and-mechanochemical recycling of waste polypropylene into warm-mix asphalt modifier. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 398, 136542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, R.; Ivanov, S. Chemical modification of road asphalts by atactic polypropylene. Polym. Sci. Ser. A 2017, 59, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Chen, J.; Zhao, M. Mechanochemical Upcycling of Waste Polypropylene into Warm-Mix Modifier. Polymers 2024, 16, 2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moubark, S.; Khodary, F.; Othman, A. Evaluation of Mechanical properties for polypropylene Modified Asphalt concrete Mixtures. Int. J. Sci. Res. Manag. (IJSRM) 2017, 5, 7797–7801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.O.R.; Ali, S.; Beg, T.; Farrukh, M.; Sun, D. Enhancement of Hot Mix Asphalt (Hma) Properties Using Waste Polypropylene. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2024, 23, 2405–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummala, S.K.; Ogundana, A.K.; Kosaraju, S.; Bobba, P.B.; Singh, S.K. Waste Plastic in Road Construction, Pathway to a Sustainable Circular Economy: A Review. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 391, 01116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, X. Life cycle assessment of end-of-life treatments for waste plastics in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Fang, Z.; Tong, L.; Xu, Z. Degradation and thermal properties of in situ compatibilized PS/POE blends. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2007, 92, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoti, M. Melt-crystallizations of α and γ forms of isotactic polypropylene in propene-butene copolymers. Polymers 2022, 14, 3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunderlich, B. Heat capacity and other thermodynamic properties of linear macromolecules. III. Polypropylene. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1981, 10, 119–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J. Later Stage Melting of Isotactic Polypropylene. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 2136–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, T.; Morton, J.; Al-Rekabi, Z.; Cant, D.; Davidson, S.; Pei, Y. Surface properties and rising velocities of pristine and weathered plastic pellets. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2022, 24, 794–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, Š.; Sapcanin, A. Polymeric materials in gluing techniques. J. Sustain. Technol. Mater. 2023, 3, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ash, S.; Sharma, R.; Rabnawaz, M. Comparative Study of Polyethylene, Polypropylene, and Polyolefins Silyl Ether-Based Vitrimers. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 22287–22297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisticò, R. Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) in the packaging industry. Polym. Test. 2020, 90, 106707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksiuta, Z.; Jalbrzykowski, M.; Mystkowska, J.; Romanczuk, E.; Osiecki, T. Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Polylactide (PLA) Composites Modified with Mg, Fe, and Polyethylene (PE) Additives. Polymers 2020, 12, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Narro, G.; Hassan, S.; Phan, A.N. Chemical recycling of plastic waste for sustainable polymer manufacturing–A critical review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Beukelaer, H.; Hilhorst, M.; Workala, Y.; Maaskant, E.; Post, W. Overview of the mechanical, thermal and barrier properties of biobased and/or biodegradable thermoplastic materials. Polym. Test. 2022, 105, 107803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Loughlin, J.; Doherty, D.; Herward, B.; McGleenan, C.; Mahmud, M.; Bhagabati, P.; Boland, A.N.; Freeland, B.; Rochfort, K.D.; Kelleher, S.M.; et al. he Potential of Bio-Based Polylactic Acid (PLA) as an Alternative in Reusable Food Containers: A Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siracusa, V.; Blanco, I. Bio-based and Conventional Polyolefins: Properties and Applications. Polymers 2020, 12, 1012–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.; Yaqoob, M.; Aggarwal, P. An overview of biodegradable packaging in food industry. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Cai, K. Review of research progress on waste plastic modified asphalt. J. Hebei Univ. Archit. Technol. 2025, 1516, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamtai, A.; Elkoun, S.; Robert, M.; Mighri, F.; Diez, C. Mechanical Recycling of Thermoplastics: A Review of Key Issues. Waste 2023, 1, 860–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, P.; Petersmann, S.; Wild, N.; Feuchter, M.; Duretek, I.; Edeleva, M.; Ragaert, P.; Cardon, L.; Lucyshyn, T. Impact of Multiple Reprocessing on Properties of Polyhydroxybutyrate and Polypropylene. Polymers 2023, 15, 4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Vacano, B.; Reich, O.; Huber, G.; Türkoglu, G. Elucidating pathways of polypropylene chain cleavage and stabilization for multiple loop mechanical recycling. J. Polym. Sci. 2023, 61, 1849–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polachova, A.; Cisar, J.; Novak, M.; Dusankova, M.; Sedlarik, V. Effect of repeated thermoplastic processing of polypropylene matrix on the generation of low-molecular-weight compounds. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2025, 238, 111337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Mantia, F.P.; Scaffaro, R.; Baiamonte, M.; Ceraulo, M.; Mistretta, M.C. Comparison of the Recycling Behavior of a Polypropylene Sample Aged in Air and in Marine Water. Polymers 2023, 15, 2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawoud, M.; Taha, I. Effects of Contamination with Selected Polymers on the Mechanical Properties of Post-Industrial Recycled Polypropylene. Polymers 2024, 16, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tratzi, P.; Giuliani, C.; Torre, M.; Tomassetti, L.; Petrucci, R.; Iannoni, A.; Torre, L.; Genova, S.; Paolini, V.; Petracchini, F.; et al. Effect of Hard Plastic Waste on the Quality of Recycled Polypropylene Blends. Recycling 2021, 6, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, Z. Extrusion. In Food Process Engineering and Technology; Berk, Z., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 333–350. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, L.; Zhu, J.; Li, S.; Ma, Y.; Yue, C. Analysis of liquid products and mechanism of thermal/catalytic pyrolysis of polypropylene. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2025, 238, 111338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldahshory, A.I.; Emara, K.; Abd-Elhady, M.S.; Ismail, M.A. Catalytic pyrolysis of waste polypropylene using low-cost natural catalysts. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papageorgiou, G.Z.; Papaspyrides, C.D. A study on the dissolution/reprecipitation technique for polymer recycling: The case of polypropylene and other common plastics. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2009, 114, 2267–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parku, G.K.; Collard, F.-X.; Görgens, J.F. Pyrolysis of waste polypropylene plastics for energy recovery: Influence of heating rate and vacuum conditions on composition of fuel product. Fuel Process. Technol. 2020, 209, 106522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumasa, T.; Kawatani, Y.; Masuda, H.; Nakashita, I.; Hashiguchi, R.; Takemoto, M.; Suganuma, S.; Tsuji, E.; Wakaihara, T.; Katada, N. Shape selective cracking of polypropylene on an H-MFI type zeolite catalyst with recovery of cyclooctane solvent. RSC Sustain. 2025, 3, 890–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmay, P.; Medina, C.; Donoso, C.; Barzallo, D.; Bruno, J.C. Catalytic pyrolysis of recycled polypropylene using a regenerated FCC catalyst. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2023, 25, 1539–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, X.T.; Kim, E.S.; Mun, D.H.; Jung, T.; Shin, J.; Kang, N.Y.; Park, Y.-K.; Kim, D.K. Catalytic Cracking of Crude Waste Plastic Pyrolysis Oil for Enhanced Light Olefin Production in a Pilot-Scale Circulating Fluidized Bed Reactor. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 12493–12503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravgaard, D.P.; Henriksen, M.L.; Hinge, M. Dissolution recycling for recovery of polypropylene and glass fibres. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2024, 26, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rorrer, J.E.; Troyano-Valls, C.; Beckham, G.T.; Román-Leshkov, Y. Hydrogenolysis of Polypropylene and Mixed Polyolefin Plastic Waste over Ru/C to Produce Liquid Alkanes. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 11661–11666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchocki, T. Sustainable Energy Application of Pyrolytic Oils from Plastic Waste in Gas Turbine Engines. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentes, D.; Nagy, G.; Szabó, T.J.; Hornyák-Mester, E.; Fiser, B.; Viskolcz, B.; Póliska, C. Combustion behaviour of plastic waste—A case study of PP, HDPE, PET, and mixed PES-EL. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 402, 136850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xayachak, T.; Haque, N.; Lau, D.; Parthasarathy, R.; Pramanik, B.K. Assessing the environmental footprint of plastic pyrolysis and gasification: A life cycle inventory study. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 173, 592–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemwell, B.E.; Levendis, Y.A. Particulates generated from combustion of polymers (plastics). J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2000, 50, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-S.; Wang, G.-H.; Liu, Y.; Jiao, Y.-H.; Liu, D. Thermal Stability, Combustion Behavior, and Toxic Gases in Fire Effluents of an Intumescent Flame-Retarded Polypropylene System. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 6978–6984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentes, D.; Jordán, A.; Farkas, L.; Muránszky, G.; Fiser, B.; Viskolcz, B.; Póliska, C. Evaluating emissions and air quality implications of residential waste incineration. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalhat, M.A.; Al-Abdul Wahhab, H.I. Performance of recycled plastic waste modified asphalt binder in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2017, 18, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira Bueno, I.; Tighi, J.; Teixeira, J.E.S.L. Effects of waste plastic addition via dry method and pre-mixing temperature on the mechanical performance of asphalt concrete. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Liu, Q.; He, Y.; Shen, Z.; Han, X.; Xu, S.; Yu, J. Enhanced asphalt fume suppression through cellulose- and lignin-rich biochar: A structure-property relationship. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 495, 143655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, M.; Leng, B.; Wu, S.; Chen, D.; Zhao, Z. Investigation on storage stability, H2S emission and rheological properties of modified asphalt with different pretreated waste rubber powder. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 456, 142469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Zhao, Y.; Li, K. Using Waste Plastics as Asphalt Modifier: A Review. Materials 2021, 15, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikrishnan, S.; Jubinville, D.; Tzoganakis, C.; Mekonnen, T.H. Thermo-mechanical degradation of polypropylene (PP) and low-density polyethylene (LDPE) blends exposed to simulated recycling. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2020, 182, 109390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Chen, A.; Wu, S.; Xu, H.; Wang, H.; Lv, Y. Synergistic Reduction in Asphalt VOC Emissions by Hydrochloric Acid-Modified Zeolite and LDHs. Materials 2024, 17, 5664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Li, C.; Wang, H.; Zeng, W.; Ling, T.; Jiang, L.; Li, R.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, D. Preparation of Wax-Based Warm Mixture Additives from Waste Polypropylene (PP) Plastic and Their Effects on the Properties of Modified Asphalt. Materials 2022, 15, 4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Wang, H.; Fu, C.; Shi, S.; Li, G.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, D.; Jiang, L.; Cheng, Y. Evaluation of modified bitumen properties using waste plastic pyrolysis wax as warm mix additives. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 405, 136910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.C.; Jusli, E.; Anggraini, V.; Jaya, R.P.; Zhang, X.Q. Performance and environmental impacts of waste plas-tic-modified asphalt pavement: A comprehensive review. Clean. Mater. 2025, 18, 100357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhou, L.; Sun, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, M.; Hu, Y.; Temitope, A.A. Analysis of the Influence of Production Method, Plastic Content on the Basic Performance of Waste Plastic Modified Asphalt. Polymers 2022, 14, 4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Fu, Q.; Fang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, C. Preparation, Structure, and Properties of Modified Asphalt with Waste Packaging Polypropylene and Organic Rectorite. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 2019, 5362795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.T.; Leng, Z.; Chen, R.Q.; Xu, X.; Li, R.; Zou, F.L.; Tan, Z.F. A chemical method to upcycle waste polypropylene into bitumen compatible modifier by polyol grafting through reactive extrusion. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 517, 145831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugraha, A.F.; Naindraputra, A.J.; Gaol, C.S.A.L.; Ismojo, I.; Chalid, M. Polypropylene-based Multilayer Plastic Waste Utilization on Bitumen Modification for Hot-Mixed Asphalt Application: Preliminary Study. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. Educ. 2022, 4, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Hao, X.; Fan, C.; Zhang, S.; Ma, D.; Yu, X.; Fu, Z.; Feng, G. Effect of Polypropylene Grafted Maleic Anhydride (PP-G-MAH) on the Properties of Asphalt and its Mixture Modified With Recycled Polyethylene/Recycled Polypropylene (RPE/RPP) Blends. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 814551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Li, J.; Shan, B.; Yao, Y.; Huang, C. A Comprehensive Review of Applications and Environmental Risks of Waste Plastics in Asphalt Pavements. Materials 2025, 18, 3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, W.; Wu, S. Selecting the Best Performing Modified Asphalt Based on Rheological Properties and Microscopic Analysis of RPP/SBS Modified Asphalt. Materials 2022, 15, 8616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buruiana, D.L.; Georgescu, P.L.; Carp, G.B.; Ghisman, V. Recycling micro polypropylene in modified hot asphalt mixture. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Lin, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, D.; Xie, N.; Shi, X. A review of polymer-modified asphalt binder: Modification mechanisms and mechanical properties. Clean. Mater. 2024, 12, 100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melekhina, V.Y.; Vlasova, A.V.; Ilyin, S.O. Asphaltenes from Heavy Crude Oil as Ultraviolet Stabilizers against Polypropylene Aging. Polymers 2023, 15, 4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, P.; Xu, G.; Yang, J.; Chen, X.; Zhu, Y. Study on Storage Stability of Activated Reclaimed Rubber Powder Modified Asphalt. Materials 2021, 14, 4684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galpaya, D.; Ismail, H.; Ahmad, Z. The Effects of PP-g-MA on the Physical Properties and Morphology of Polypropylene (PP)/Recycled Acrylonitrile Butadiene Rubber (rNBR) Blends. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Eng. 2010, 49, 1150–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, N.Z.; Kamaruddin, I.; Tan, I.M.; Komiyama, M. Investigation on the effect of phase segregation on the mechanical properties of polymer modified bitumen using analytical and morphological tools. MATEC Web Conf. 2017, 120, 07002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, M.; Yan, Y.; Han, M.; Zhao, Y. Modified Asphalt Prepared by Coating Rubber Powder with Waste Cooking Oil: Performance Evaluation and Mechanism Analysis. Coatings 2025, 15, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhou, H.; Jiang, X.; Polaczyk, P.; Xiao, R.; Zhang, M.; Huang, B. The utilization of waste plastics in asphalt pavements: A review. Clean. Mater. 2021, 2, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Luo, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Chu, Y.; Hu, G.; Xu, X. Mechanochemical preparation and performance evaluations of bitumen-used waste polypropylene modifiers. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hao, P.; Sun, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y. Rheological Properties and Mechanism of Asphalt Modified with Polypropylene and Graphene and Carbon Black Composites. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2022, 34, 04022343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Chen, Z.; Hong, J.; Liao, Z.; Wang, D.; Yuan, D.; Zhang, Y.; Falchetto, A.C. Preparation and Properties of High-Viscosity Modified Asphalt with a Novel Thermoplastic Rubber. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; Hu, T.; Xu, X.; Yin, B. Enhancing the properties and engineering performance of asphalt binders and mixtures with physicochemically treated waste wind turbine blades. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 473, 141023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulghafour, M.M.; Ismael, M.Q. Moisture Susceptibility of Asphalt Mixtures Modified by Recycled Polypropylene. J. Eng. 2025, 31, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, H.K.; Giri, D.; Das, S.S. Moisture and rutting resistance of recycled polypropylene fiber-modified dense bituminous mix. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2023, 8, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.M.; He, M.; Hao, G.; Ng, T.C.A.; Ong, G.P. Recyclability potential of waste plastic-modified asphalt concrete with consideration to its environmental impact. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 439, 137299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, K.; Li, F.; Wang, L.; Cao, J. Exploring the effect of different waste polypropylene matrix composites on service performance of modified asphalt using analytic hierarchy process. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 405, 133292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, H.; Osei, P.; Shalaby, A. Performance of Bituminous Binder Modified with Recycled Plastic Pellets. Materials 2023, 16, 6730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qabur, A.; Baaj, H.; El-Hakim, M. Exploring the low-temperature performance of MPP-modified asphalt binders and mixtures using wet method. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 51, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyelere, A.; Wu, S.; Hsiao, K.-T.; Kang, M.-W.; Dizbay-Onat, M.; Cleary, J.; Venkiteshwaran, K.; Wang, J.; Bao, Y. Evaluation of cracking susceptibility of asphalt binders modified with recycled high-density polyethylene and polypropylene microplastics. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 438, 136811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vamegh, M.; Ameri, M.; Chavoshian Naeni, S.F. Experimental investigation of effect of PP/SBR polymer blends on the moisture resistance and rutting performance of asphalt mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 253, 119197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Hou, H.; Zhu, S.; Zha, J. Utilization of Waste Polypropylene Plastic in Asphalt Mixtures to Improve Fatigue and Rutting Resistance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 406. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Xu, O.; Guo, P. Fatigue Resistance of Polypropylene Modified Asphalt under Cyclic Loading. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2014, 26, 04014008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q. Rheological Properties and Fatigue Resistance of Recycled Polypropylene Modified Asphalt. Polymers 2019, 11, 1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Property | PP (Virgin) [34,35,36] | PE [34,35,36] | PET [34,35,36] | PLA [34,35,36] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density (g/cm3) | 0.90–0.92 | 0.91–0.96 | 1.34–1.39 | 1.20–1.25 |

| Melting point (°C) | 160–170 | 110–135 | 250–260 | 150–170 |

| Glass transition temperature (°C) | −10 | −120 | 70–80 | 55–65 |

| Tensile strength (MPa) | 25–40 | 10–30 | 50–80 | 50–70 |

| Elastic modulus (GPa) | 1.2–1.8 | 0.2–1.0 | 2.0–2.7 | 2.7–3.5 |

| Chemical resistance | Excellent | Excellent | Good | Moderate (hydrolyzable) |

| Biodegradability | Non-degradable | Non-degradable | Non-degradable | Degradable |

| Cost level | Low | Low | Medium | High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, N.; Du, C.; Tang, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, S.; Xu, X. Waste Polypropylene in Asphalt Pavements: A State-of-the-Art Review Toward Circular Economy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410954

Yang N, Du C, Tang Y, Li Z, Xu S, Xu X. Waste Polypropylene in Asphalt Pavements: A State-of-the-Art Review Toward Circular Economy. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):10954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410954

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Nannan, Congying Du, Ye Tang, Zhiqi Li, Song Xu, and Xiong Xu. 2025. "Waste Polypropylene in Asphalt Pavements: A State-of-the-Art Review Toward Circular Economy" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 10954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410954

APA StyleYang, N., Du, C., Tang, Y., Li, Z., Xu, S., & Xu, X. (2025). Waste Polypropylene in Asphalt Pavements: A State-of-the-Art Review Toward Circular Economy. Sustainability, 17(24), 10954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410954