Abstract

Employers are highlighting the importance of knowledge and professional skills, including personal, interpersonal, communication, and thinking, in their quest for graduates who are prepared for the workforce. Collaborative research is an essential toolbox that integrates knowledge, skills, and attitudes, which is important for future engineers; nonetheless, undergraduate students often struggle to engage effectively in this key competency. This study presents an undergraduate sustainability research experience (CUSRE) that is built into two courses, utilizing a collaborative-based learning (CBL) setting aimed at creating knowledge, improving skills and competencies, encouraging inclusivity, and advancing equitable education. The objective of the study is to narrow the achievement gap, improve graduation rates, and boost students’ enthusiasm and readiness for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It encompasses a strategy that integrates key approaches, including collaborative research, sustainability as a core value and practice, and educational equity supported by compensatory pedagogy that emphasizes teamwork. Introduced at the University of Ottawa (uOttawa) in Canada, the initiative engaged students to deepen their understanding of the SDGs through research cases and projects. This experience yielded significant knowledge gains and a considerable success rate among participants. Moreover, it has been successfully scaled and adapted for the Global Banking School (GBS) in the UK, thereby broadening its impact to a larger audience.

1. Introduction

The Oxford Dictionary defines sustainability as “the ability to be maintained at a certain rate or level.” The official definition may stay “meeting our own needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs” from the Brundtland Commission in 1987 [1]. The UN’s Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (2005–2014) highlighted the importance of education in fostering sustainability by changing knowledge, values, and attitudes [2]. This initiative was further supported by the 2015 UN SDGs, especially Target 4.7, which specifically focuses on education and aims to provide all learners with the knowledge and skills necessary to promote sustainable development (SD) [3].

In the context of engineering education, Arefin et al. [4] characterized sustainability as the integration of environmental, social, and economic factors into the training of future engineers. To foster sustainable futures, it is essential to enhance the curriculum by expanding technical content to incorporate sustainability perspectives, thereby connecting learning to genuine challenges and students’ personal experiences [5]. For effectiveness, sustainability needs to be more deeply integrated into the curriculum by linking academic knowledge with the practical competencies required in professional settings. Additionally, it is crucial to tackle educational disparities, which act as systemic obstacles to social justice, environmental consciousness, and economic progress.

Understanding the ways sustainability is perceived and practiced in both educational and professional settings is crucial for developing successful initiatives. To challenge the above issue, scholars have emphasized the need for a clearer articulation of educational objectives and more robust frameworks for program design and assessment, with a particular focus on social inclusivity and equity [6,7,8]. Inclusion is crucial for sustainable engineering, as demonstrated by the professional standards to which engineers are held and the educational frameworks that underpin them.

Today, there is increasing recognition that, despite ongoing efforts to promote equity and equality, many schools still perpetuate various inequalities arising from disparities across multiple dimensions. Educational equity underscores the interconnectedness of these disparities [9]. Within this context, inclusive education can effectively tackle broader inequalities, promote fairness, and ensure that all students, regardless of their disadvantages, can benefit from their educational experiences. This education is focused on meeting the needs of every student while maintaining the existing structure and mechanisms of the learning process so students can achieve their fullest potential [10,11].

A key aspect of inclusive education is fostering equity-mindedness, which involves educators acknowledging and addressing disparities in student outcomes, exploring the underlying factors, and assuming both personal and institutional responsibility for rectifying these inequities [12,13,14]. This education promotes fair resource distribution, addresses diverse learning needs, and encourages social integration [15]. To effectively realize this goal, educators must adopt an equity-driven approach that strategically combines values with knowledge pathways. Building and nurturing such a culture is vital for empowering students to take ownership of their learning. Critical factors for successful adaptation and implementation include changing mindsets, fostering engagement, and developing a strategy for assessment for learning. These elements are essential for reducing grade repetition, increasing study completion rates, and narrowing the achievement gap.

A productive method for enhancing inclusive education is to integrate the CBL as a fundamental element of engineering practice [16]. This framework serves as a performance-based compensatory resource that encourages student collaboration, sparks innovation, and supports collaborative achievements to identify at-risk students early on [17]. While the effectiveness of teams is a significant factor influencing student experiences with teamwork, additional components also play an essential role [18,19]. These encompass inclusion within teams, fairness among team members, the dynamics of social interactions [20], taking responsibility, and sharing achievements. Collectively, these components can have a compensatory impact that boosts the overall success rate.

Many academic institutions support integrating collaborative research into various study programs due to its complementary benefits and other factors. However, most of these institutions lack the necessary resources to involve all or most undergraduates in research activities [21]. Traditionally, this approach targets a select group of students, usually juniors or seniors, who work closely with a professor on a research project during the academic year or over the summer [22]. Engaging with faculty on research gives students a transformative experience, enabling them to think and question like scientists while developing the skills needed to explore the world and understand their place within it [23].

To investigate the impact of CUSRE and CBL on educational inclusivity and equity, this study examines four key research questions: (1) Which instructional strategies most effectively promote student engagement with sustainability and core human values, and how do these strategies affect students’ hard and soft skills? (2) In what ways do thinking skills shape students’ understanding of inclusivity and equity within engineering education? (3) How can collaborative research and assessment for learning contribute to reducing performance achievement gaps and promoting success among students? (4) How might the scaling and adaptation of interventions enhance or challenge these outcomes to reach a broader audience? The findings related to these questions are discussed in the following sections.

2. Value-Based CBL

CBL enables students to learn from one another while fostering positive relationships with peers from diverse cultural backgrounds and varying learning styles. These transformative practices also support grade-level achievement. CBL activities, such as research case studies and projects, exemplify the transformation necessary for engineering education [24]. These activities prioritize the application of knowledge over mere memorization, offering students hands-on engagement and real-world applications of their skills. They can improve student engagement and help address human values by encouraging students to connect with their social environment and form stronger relationships with peers.

A highly effective approach to integrating sustainability as a core value into education and research is by embracing the 17 interconnected SDGs that constitute the UN 2030 Agenda. These goals aim to promote a more equitable, inclusive, and healthy world [25]. Education is the keystone conduit for all SDGs, and it is only with “quality education,” SDG 4, that the global society can flourish [26]. To actively contribute to the achievement of SDG 4, the higher education sector can leverage its three core functions—knowledge acquisition, knowledge creation, and knowledge dissemination—to support all the SDGs [27]. In particular, the forthcoming cohorts of engineering graduates are positioned to play a vital role in advancing sustainability for socio-technical development. This endeavour necessitates that the education system consistently imparts the essential pedagogies required to envision sustainability as an ethical principle that guides actions in knowledge creation. Universities serve as key spaces for this effort. Accordingly, the CDIO framework, which emphasizes a “conceive, design, implement, operate” methodology, has been revised to incorporate new educational practices such as collaborative research and SD [28].

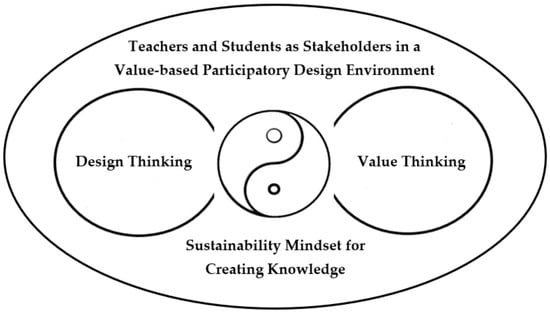

Human values are considered the driving engine of engineering design activities [29]. These values, in essence, are more inclusive when it comes to building technologies that serve society. Engineering educators have advocated for pedagogical approaches that connect engineering practices to students’ values, lives, accountability, ethics, and cultural backgrounds [30,31,32]. These frameworks prioritize inclusive teaching methods alongside a critical analysis of engineered systems. The design process helps students understand how knowledge is constructed and how it reflects the values and perspectives of its creators. This methodology emphasizes the lived experiences of users and stakeholders, particularly those from historically marginalized communities. Such a value-based participatory design entails a cyclical approach that highlights stakeholders’ contributions at every stage of the design process. Ultimately, fostering thinking skills in research and knowledge creation leads to meaningful learning results as undergraduate engineering students gear up for their future careers. The knowledge creation process enables students to understand how knowledge is formed and how it reflects their own experiences and values. Figure 1 illustrates the amalgamation of thinking skills for cultivating a sustainability mindset growth within a participatory setting.

Figure 1.

Thinking skills for sustainability mindset growth within a participatory setting.

3. Compensatory Pedagogy for CUSRE and CBL

Working in an engineering workplace requires strong teamwork and collaborative skills. In addition to technical skills, Fleming et al. [33] identified the top professional skills or “holistic competencies” needed for engineering graduates in the twenty-first century. These include teamwork and collaboration, communication, leadership, and project management. On the other hand, Rieckmann [34] identified the key pedagogies for implementing education for SD. These include learner-centered approach, action-oriented learning, and transformative learning. These pedagogies emphasize the active development of knowledge through experiences that require observation and reflection. Furthermore, most national engineering accreditation bodies like the Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology (ABET), the Canadian Engineering Accreditation Board (CEAB), the European Network for Accreditation of Engineering Education (ENAEE), and the International Engineering Alliance (IEA) have included professional skills, including CBL, as key graduate attributes in their requirements for accrediting engineering programs [35,36]. Therefore, collaborative research opportunities are essential in supporting a pathway toward future careers.

Ensuring that every student can engage in collaborative research addresses implicit bias and educational inequity. In response to this challenge, several university faculty members have developed innovative strategies to involve all students in research initiatives, thereby extending educational advantages to a broader audience [37]. Traditional collaborative research often perpetuates inequity; however, this can potentially be addressed through the implementation of course-based undergraduate research experiences (CURE). Established in 2012, the CUREnet aims to foster the integration of research into the classroom, mainly in science studies. Its primary objective is to facilitate networking and resource sharing among faculty who adopt the CURE approach in their pedagogy. In contrast, an independent CURE typically arises from a faculty member’s specific research interests or program [38]. Preliminary research suggests that CURE offers numerous advantages to faculty members. These benefits include a closer integration of teaching and research, which can positively influence promotion and tenure outcomes. Moreover, participation in CURE may lead to research publications in conference proceedings and journals, enhancing the overall impact of research programs. Faculty members also gain from the opportunities to identify, recruit, and train students for their research labs, fostering a productive and thriving research environment [39]. Notably, there is currently a lack of specific CURE in the literature that focuses on engineering education.

Student engagement has long been recognized as an inexplicable and multifaceted meta-construct [40], and is often confused with motivation, which is seen as an antecedent and the force that energizes behaviour [41]. One of the primary CBL influences is promoting social motivation, which has been shown to enhance students’ self-esteem and confidence in their academic abilities [42]. Student engagement can be seen as the contagious passion that individuals exhibit when pursuing topics of personal interest through an inductive and investigative learning approach. It is through these highly engaging approaches that students are inspired to enhance their fundamental skills and elevate their work to increasingly higher standards of excellence. Genuine engagement arises from learning activities that motivate students to venture beyond their current comfort zones, employing resources and investigation methods that differ significantly from mere repetitive exercises.

Motivational engagement within the CBL environment may play a compensatory factor in reducing the achievement gap and increasing the success rate. It has been extensively studied as an effective instructional strategy that positively influences student motivation. According to Möller [43], compensatory pedagogy is a theoretical approach that aims to manage social and cultural diversity by providing additional resources or special treatment to groups deemed disadvantaged. Nonetheless, fostering a critical awareness of norms is essential to transforming educational practices into more equitable, representative, and culturally democratic forms [44].

A variety of research [45,46] has shown that CBL significantly enhances students’ academic success. This method facilitates deep learning by engaging students with the content as they interact in discussions, debates, and the joint synthesis of information. Studies indicate that students involved in collaborative activities typically perform better on assessments, as such an environment promotes higher-order thinking skills like critical thinking, reflective thinking, and problem-solving [47]. These collaborative tasks may act as performance-based compensatory methods that motivate students to work together, exchange ideas, and share responsibilities, resulting in a more profound comprehension and achievement.

A major challenge in engineering education is the achievement gap, which often leads to high dropout, withdrawal, and failure rates. This gap can be caused by various factors, including the benefits some students perceive, their backgrounds, and the different ways students learn. One possible solution for this gap is the adoption of collaborative, transformative approaches. According to Lee [48], students who collaborate actively in the group space, as part of the flipped learning approach, for example, have been found to undergo deeper knowledge, increased motivation and greater achievement. Sleeter [49] emphasizes that compensatory pedagogy is designed to address social and cultural diversity by providing additional resources or special considerations for marginalized groups. This approach to social inclusion enhances the participation of individuals and groups in engineering and related fields, particularly focusing on the inclusion of students who are frequently excluded or disadvantaged due to their identities or learning styles within engineering culture and systems [50]. Team performance tends to improve when one or more members take the initiative to compensate for the perceived or actual weaknesses of their peers. This teamwork intervention strategy can be effectively implemented through a CBL, which incorporates interactive and active approaches that merge research with teaching [51]. In this framework, collaborative research skills are utilized to challenge and explore new ideas.

4. Study Motivation and Context

Today, engineering education bears the critical responsibility of addressing complex global challenges. Therefore, it is essential to acknowledge the interconnectedness of these challenges and the vital role that engineering plays in developing innovative solutions. In this context, engineering students, drawing on their diverse perspectives and educational backgrounds, possess the capability to create effective responses to these challenges. To unlock this potential, a transformation in pedagogical approaches is necessary—one that promotes various skills and values within an active learning environment.

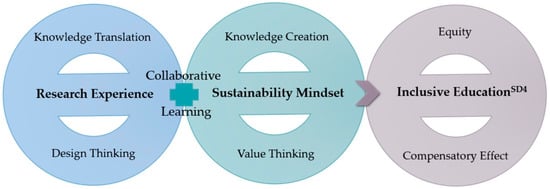

This study may be one of the first to present an enhanced model of CURE for engineering education by integrating collaborative research, sustainability values and practices, and educational equity through an active learning setting. One crucial aspect of this integration is the initiative “CUSRE”, which was implemented at the uOttawa, Canada, in late 2023 and continued through 2025. Two courses were designated to integrate the CUSRE as a fundamental component of the curriculum: a second-year course titled “Professional Practice-CUSRE 1” with 72 students and a fourth-year course named “Power Engineering-CUSRE 2” consisting of 60 students. CUSRE 1 emphasized awareness of the SDGs, whereas CUSRE 2 concentrated on sustainable design. This initiative has been broadened and tailored for a British educational setting, thus increasing its relevance to a wider audience. The key learning themes of the CUSRE are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The CUSRE major theme components.

Sustainability as a core value sets CUSRE apart from CURE, supporting the decision to adopt CUSRE as the main approach to designing the learning content for the two courses. A key feature of the CUSRE is active learning, which motivates students to participate in CBL and reflect on their experiences related to the targeted outcomes and personal growth. As Tormey et al. [52] point out, active learning can enhance knowledge acquisition, promote competency development, and facilitate the realignment of values as learners apply theory in practice. This approach aligns with the idea of “teach less, learn more,” a strategy that actively involves students in the educational journey through various activities [53]. These may include case studies, projects, flipped classrooms, modelling and simulation, peer teaching, debates and discussions, brainstorming sessions, field trips [43], and other collaborative initiatives that empower students to take ownership of their learning.

Assessment plays a crucial role in educational practice, significantly influencing both teaching and learning [54,55,56,57]. This impact is realized through a range of assessment strategies that prioritize “assessment for learning” over “assessment of learning,” promoting a growth-centered approach to grading. Such an equity-based assessment model enables students to demonstrate their progress and uses the results to enhance their knowledge development and skill mastery. It incorporates various formats, methodologies, and tools that resonate with all learners, including portfolios, educational videos, simulations, design manuals, and research articles. By emphasizing personalization, designing effective rubrics, and providing effective feedback, this approach will yield valid insights into each student’s unique learning style.

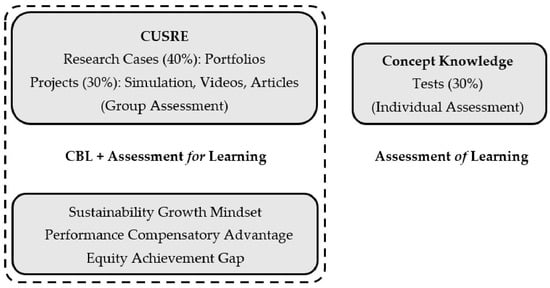

In this study, the curriculum is designed to integrate sustainability and engineering through a research-oriented approach. This integration is accomplished through targeted support modules, the challenges presented, and the criteria set by the instructor. The courses’ content is organized into two primary components: CUSRE/CBL (research cases and projects) based on group assessment (GA) and concept knowledge (tests) based on individual assessment (IA), as illustrated in Figure 3. Both components emphasize cycles of feedback and iteration instead of viewing them as a straightforward sequence.

Figure 3.

Learning components and assessment approaches.

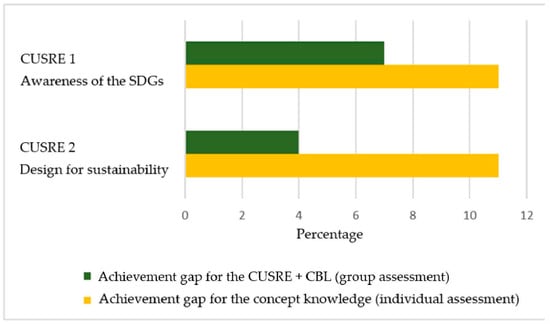

CUSRE 1 aimed to enhance understanding of the SDGs, allowing students to examine both the factual and ethical dimensions of sustainability. They cultivated positive behaviours that encourage a sustainability mindset and ethical comprehension while merging professional skills with engineering knowledge. During the analysis of gathered data, a disparity of 11% in IA was identified between low-achieving and high-achieving students. This gap narrowed to approximately 7% in GA within the CUSRE and CBL setting.

The more advanced CUSRE 2 offered students the chance to explore how intelligent technologies can enhance energy system performance through research, design, and simulation. This method emphasizes systems thinking via participatory design. In analyzing the collected data, an equity gap of about 11% in IA was observed between low-achieving and high-achieving students, which has been reduced to 4% in GA within the CUSRE and CBL environment. Figure 4 shows the positive impact of compensatory pedagogical intervention in narrowing the achievement gaps for CUSRE 1 and CUSRE 2.

Figure 4.

Positive impact of pedagogical intervention on achievement gaps for both courses.

To summarize, understanding sustainability means embedding it in the curriculum and fostering inclusivity within educational content. Both CUSRE and CBL enhance educational practices by promoting active engagement and developing essential soft skills. By utilizing the assessment for learning framework, CBL contributes to narrowing the achievement gap and boosting success rates.

5. Scaling and Adaptation

The authors have considered expanding on how an intervention can be scaled or adapted to different educational contexts beyond the uOttawa and making it more applicable to a broader audience. For this task, the second author examined how some non-traditional students (adults), such as those studying construction management at the GBS in London, UK, find the learning and research environment inspirational and supportive, primarily due to its collaborative nature and subsequent assessment. Accordingly, three groups of students studying three modules required by the program, which is delivered in partnership with Bath Spa University, were selected to research the impact of CBL on the learning outcome. The three selected modules, “Preparing for a Professional Career, Environment and Sustainable Issues, and Professional Practice,” have been offered at three different levels of study from Level 3 to Level 5. For this intervention, each of the three selected modules has been assessed using two different strategies, IA and GA.

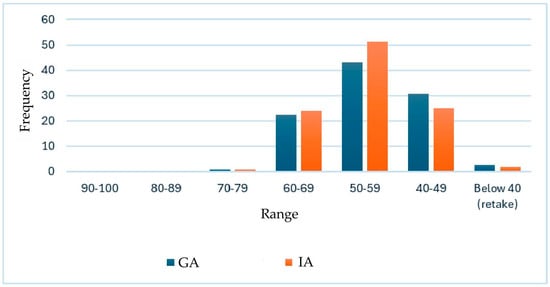

After several weeks of teaching on the Moodle platform, server data on the number of submitted assignment marking requests were analyzed to evaluate the intervention. Server statistics were reviewed using the frequency distribution tool to facilitate practical comparisons between individual and group data. This tool helped to analyze how learners in the three groups performed during IA compared to GA and to identify clusters and gaps in the marks.

Figure 5 presents a comparative analysis using server data between IA and GA achievement. The analysis reveals a pattern of improvement across most of the seven scoring categories. The findings indicate that GA has had a measurable impact on student achievement, particularly within the middle performance ranges. The most significant improvement is seen within the 50–59 mark range, where the percentage of students increased from 43.2% under IA to 51.2% under GA, a rise of 8.0 percentage points. This notable increase suggests that GA positively influenced students near the pass threshold. A modest improvement is also observed within the 60–69 range, where performance rises from 22.3% to 24.1%, showing steady progress among students in the upper-middle tier.

Figure 5.

Impact of assessment methods on the student achievement gap.

In contrast, the 40–49 range saw a decrease from 30.8% in IA to 25.1% in GA, resulting in a drop of 5.7 percentage points. This reduction may be linked to students in this lower range advancing to the 50–59 category following the GA contribution. Similarly, the proportion of students scoring below 40 decreased from 2.7% to 1.9%, indicating a 0.8% improvement in the overall passing rate. These results suggest that GA helps students who were initially performing at or just below the passing mark to improve.

At the upper end of the statistical distribution, the marker indicates minimal changes, with no recorded frequencies in the 80–89 and 90–100 ranges for either IA or GA. The 70–79 range shows only a slight increase of 0.9 percentage points, suggesting that the GA process has a limited impact on higher-achieving students. This consistency at the top end of the distribution indicates that while GA effectively supports students who are borderline and in the mid-range, it does not significantly improve outcomes for those who already demonstrate strong academic performance.

Statistics is used to determine whether there is a statistically significant difference between the score distributions for IA and GA. The Chi-square test for independence was conducted to confirm this validation. The validation relies on observed frequencies using equal sample sizes for both assessments. The test showed no significant difference between the frequency distributions of IA and GA. Additionally, the distribution indicates that the performance of the two assessment types is very similar across the seven scoring categories. Moreover, the non-significant p-value suggests that the observed differences in frequencies are probably due to random sampling error rather than systematic differences between the IA and GA.

Regarding the size analysis of the statistics, the strength of association between the two types of assessments and their score distributions was evaluated using Cramér’s V formula. The computed value for V is 0.07, indicating a negligible effect size according to Cohen’s criteria [58]. The analysis shows that there is no statistically significant difference in performance distributions between the IA and GA. Both assessment types exhibited similar trends, with most participants scoring between 50% and 59%, suggesting that the IA and GA are likely comparable in terms of difficulty and grading outcomes during the evaluation.

6. Study Significance

The significance of this study is fourfold. First, it seeks to address a gap in the existing literature by providing in-depth descriptions of students’ holistic experiences with value-based research and the social significance of CBL as they are applied in engineering practice. Second, it investigates how thinking skills can cultivate a sustainability mindset for knowledge creation within engineering education. Third, the results could help improve educational equity by closing the achievement gap, promoting open-minded assessment practices, and involving all students regardless of their diverse backgrounds and learning styles. Fourth, expanding and modifying the results for implementation in another academic institution, which could extend its influence to a wider audience.

Research shows that despite emphasis on education for SD, educators worldwide experience common barriers to implementing sustainability education. These barriers include interdisciplinary aspects of sustainability, feeling unprepared in both the content and pedagogies, resources, materials, time for collaboration and ongoing professional learning opportunities [59]. The research gap highlighted in this study pertains partially to the pedagogy barrier and to the absence of a comprehensive inquiry into the CBL experiences of students and the influence of CBL on promoting educational equity. The classroom is envisioned as a dynamic learning community focused on knowledge creation, continually evolving through the integration of sustainability within the educational framework. This approach contrasts with traditional lecture methods by actively engaging students in real-world case studies and projects. Such an environment is essential for fostering skills and competencies that enable individuals to collectively embrace and address SD as a shared identity and responsibility. The study primarily focuses on embedding sustainability research into the learning process, while actively involving students in participatory design and promoting educational equity in the classroom. This is achieved by reducing the achievement gap, encouraging open-mindedness over rote knowledge, and ensuring the active participation of all students, irrespective of their social backgrounds or learning styles.

The structure of engineering programs should focus on CBL as a means to drive transformation into sustainable learning, thereby improving the quality of student output and nurturing mindset growth. While CBL in engineering classrooms is considered effective, it does not always lead to productive outcomes [60]. There are difficulties in motivating group members to actively participate and contribute, managing and aligning shared objectives, and integrating various viewpoints [61]. To tackle the above difficulties, several core objectives have been established in this study, including the development of research skills, increasing awareness and understanding of SD, and promoting equity and inclusion within engineering education. Ultimately, the study demonstrates that CUSRE and CBL, integrated within the framework of active learning, serve as an effective intervention strategy for improving academic achievement.

A key component of active learning involves distinguishing between the planned “visible” curriculum, which details what is intended to be taught, and the actual “invisible” curriculum, which reflects what students ultimately learn. This gap can be partly explained by the concept of the “hidden curriculum,” which refers to the implicit knowledge gained during curriculum implementation [43]. Research-informed active learning enables students to engage with their own interests, an opportunity often missing in passive learning settings. In this study, one notable observation related to this hidden curriculum is that students involved in the CUSRE and CBL environment often can develop communication skills and understand the processes behind effective communication. Importantly, students expressed increased enthusiasm for engineering and a deeper understanding of what it means to work as an engineer. Interestingly, many students have shown greater interest in pursuing graduate studies because of their collaborative research experiences.

A wealth of collaborative research fosters the organic development of knowledge, skills, and competencies that naturally arise from motivational engagement in the educational process. Therefore, within this framework, transformative learning necessitates iterative refinement—once implementation occurs, the revision process begins anew. Additionally, the specifics of each transformation cycle are heavily influenced by the unique needs of individual courses, students, and faculty.

7. Concluding Remarks

This study presents a methodical, data-driven context aimed at advancing the practices of inclusivity and equity in engineering education, thereby contributing to the wider objectives of SDG 4. It underscored significant advancements in students’ understanding of human values, their complexities, and their awareness of SDGs. The intervention strategy, which incorporated CUSRE, CBL, and assessment for learning, effectively contributed to narrowing the achievement gap, improving success rates, and promoting sustainability. It is therefore crucial to implement transformative changes in curricula, teaching methods, and assessment strategies to develop important related knowledge and skills. The insights derived from scaling and adapting interventions reveal how assessment strategies can effectively address disparities in student performance. Achieving transformative change, especially in the pursuit of educational equity, requires a substantial shift towards growth-based assessments.

Future research should focus on developing consistent and equitable metrics for assessing value-based experiences and exploring the influence of education delivered through collaborative research. Moreover, accreditation bodies should establish robust and enforceable standards to ensure that all engineering students are sufficiently prepared to develop sustainable solutions that address the SDGs’ challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.H. and G.Y.B.; methodology, R.H. and G.Y.B.; formal analysis, R.H. and G.Y.B.; investigation, R.H. and G.Y.B.; resources, R.H. and G.Y.B.; data curation, R.H. and G.Y.B.; writing—original draft preparation, R.H.; writing—review and editing, R.H. and G.Y.B.; visualization, R.H. and G.Y.B.; supervision, R.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Brundtland, G. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; United Nations General Assembly document A/42/427; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Buckler, C.; Creech, H. Shaping the Future We Want: UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (2005–2014): Final Report; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.refworld.org/legal/resolution/unga/2015/en/111816 (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Arman Arefin, M.d.; Nabi, N.; Sadeque, S.; Gudimelta, P. Incorporating sustainability in engineering curriculum: A study of the Australian universities. Int. J. Sustain. High. Edu. 2021, 22, 576–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmerich, A.; Deilami, N.; Ngo, T.-A.; Satia, A.; Fleisig, R. Advancing inclusivity in engineering education: Student perceptions of design thinking courses and workshops. In Proceedings of the 2025 Canadian Engineering Education Association Conference, Montreal, QC, Canada, 17–21 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- O’Byrne, D.; Dripps, W.; Nicholas, K.A. Teaching and learning sustainability: An assessment of the curriculum content and structure of sustainability degree programs in higher education. Sustain. Sci. 2015, 10, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, T.L. Competencies and pedagogies for sustainability education: A roadmap for sustainability studies program development in colleges and universities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, A.; Sidhu, G.; Alvarez, M.I.R.; Ramos, J.A.L.; Srinivasan, S. Equity, diversity, and inclusion strategies in engineering and computer science. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Educational Innovation Towards Equity: Self-reflection Questionnaire and Workshop. In Measuring Innovation in Education: Tools and Methods for Data-Driven Action and Improvement; Vincent-Lancrin, S., Ed.; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral-Gouveia, C.; Menezes, I.; Neves, T. Educational strategies to reduce the achievement gap: A systematic review. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 1155741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinzie, J.; Gonyea, R.; Shoup, R.; Kuh, G.D. Promoting persistence and success of underrepresented students: Lessons for teaching and learning. New Dir. Teach. Learn. 2008, 115, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murrihy, L. Equity-Mindedness: Challenging the Land of Inequality, Disadvantage and Marginalization. 2017. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/equity-mindedness-challenging-land-inequality-lesley-murrihy/ (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Ainscow, M. Promoting inclusion and equity in education: Lessons from international experiences. Nord. J. Stud. Educ. Policy 2020, 6, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, A.; Lipsky, D.K. Beyond special education: Toward a quality system for all students. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1987, 57, 367–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorde, O.; Lapidot-Lefler, N. Sustainable educational infrastructure: Professional learning communities as catalysts for lasting inclusive practices and human well-being. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Simmonds, H.E.; Godwin, A.; Langus, T.; Pearson, N.; Kirn, A. Building inclusion in engineering teaming practices. Stud. Eng. Educ. 2023, 3, 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitha, I.; Mokgania, G.; Sinthumule, O. Collaborative learning among extended curriculum programme students. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimpton, C.; Maynard, N. Teamwork skill development in engineering education: A holistic approach. In Proceedings of the 51st Annual Conference of the Engineering Society for Engineering Education (SEFI), Dublin, Ireland, 10–14 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tonso, K. Teams that work: Campur, culture, engineer, identity, and social interaction. J. Eng. Educ. 2006, 95, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, N.; Hladik, S.; Cicek, J.S. A proposed case study of teamwork in a Canadian mechanical engineering program. In Proceedings of the Conference of the Canadian Engineering Education Association, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 15–19 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Adebisi, Y.A. Undergraduate students’ involvement in research: Values, benefits, barriers and recommendations. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 81, 104384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansel, N.H. Course-Based Undergraduate Research: Educational Equity and High-Impact Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kardash, C.M. Evaluation of an undergraduate research experience: Perceptions of undergraduate interns and their faculty mentors. J. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 92, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habash, R. Amalgamation of research-, case-, project-, and video-based learning in teaching engineering and computing ethics. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2024, 40, 491–498. [Google Scholar]

- Habash, R. Course-based undergraduate sustainability research for equitable engineering education. In Proceedings of the 52nd Annual Conference of the European Society for Engineering Education (SEFI), Lausanne, Switzerland, 2–5 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, R.X.; Pagano, A.; Marengo, A. Values-based education for sustainable development (VbESD): Introducing a pedagogical framework for education for sustainable development (ESD) using a values-based education (VbE) approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, A. Knowledge-Driven Actions: Transforming Higher Education for Global Sustainability, UNESCO. 2022. Available online: https://www.learntechlib.org/p/221510/ (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Malmqvist, J.; Edström, A.; Rosen, A.; Hugo, R.; Campbell, D. Optional CDIO standards: Sustainable development, simulation-based mathematics, engineering entrepreneurship, internationalization and mobility. In Proceedings of the 16th International CDIO Conference, Gothenburg, Sweden, 8–10 June 2020; Volume 1, pp. 48–59. [Google Scholar]

- Eddahab-Burke, F.-Z.A.; van Langen, P.; Slingerland, G.; Brazier, F. Teaching value-based participatory design of complex socio-technical systems. Proc. Des. Soc. 2025, 5, 3011–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, D. Engineering and Social Justice; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, A.; Reid, K.; Riley, D.; van Tyne, N. Overcoming challenges to enhance a first year engineering ethics curriculum. Adv. Eng. Educ. 2020, 8, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, S.; Godwin, A.; Riley, D.M. A sociocultural learning framework for inclusive pedagogy in engineering. Chem. Eng. Educ. 2021, 55, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, G.C.; Klopfer, M.; Katz, A.; Knight, D. What engineering employers want: An analysis of technical and professional skills in engineering job advertisements. J. Eng. Educ. 2024, 113, 251–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieckmann, M. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Braodland, G.W. ABET and CEAB. Available online: https://www.civil.uwaterloo.ca/brodland/MechanicsModels/ABET&CEAB.html (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Picard, C.; Hardebolle, C.; Tormey, R.; Schiffmann, J. Which professional skills do students learn in engineering team-based projects? Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2021, 47, 314–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.A.; Woodin, T. Undergraduate research experiences in biology: Alternatives to the apprenticeship model. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2011, 10, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habash, R. Engaging undergraduate students in research and design experience. In Proceedings of the 2024 47th MIPRO ICT and Electronics Convention (MIPRO), Opatija, Croatia, 20–24 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fukami, T. Integrating inquiry-based teaching with faculty research. Science 2013, 339, 1536–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, J.J.; Christenson, S.L.; Furlong, M.J. Student engagement with school: Critical conceptual and methodological issues of the construct. Psychol. Sch. 2008, 45, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C. Engaging learners in online learning environments. TechTrends 2004, 48, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitha, D.; Kavitha, D. Improving problem-solving skills through technology-assisted collaborative learning in a first-year engineering mathematics course. Interact. Technol. Smart Educ. 2023, 4, 534–553. [Google Scholar]

- Möller, A. What is compensatory pedagogy trying to compensate for? Compensatory strategies and the ethnic ‘other’. Issues Educ. Res. 2012, 22, 60–78. [Google Scholar]

- Jaroenkhasemmeesuk, C.; Lima, R.M.; Horgan, K.; Mesquita, D.; Supeekit, T. Active learning in engineering education: Case study in mechanics for engineering. In Leveraging Transdisciplinary Engineering in a Changing and Connected World—Proceedings of the 30th ISTE International Conference on Transdisciplinary Engineering, Hua Hin Cha Am, Thailand, 11–14 July 2023; Cooper, A., Koomsap, P., Stjepandic, J., Eds.; Advances in Transdisciplinary Engineering; IOS Press BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Volume 41, pp. 633–642. [Google Scholar]

- Melzner, N.; Dresel, M.; Kollar, I. Examining the regulation of motivational and comprehension-related problems during collaborative learning. Metacogn. Learn. 2022, 3, 813–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.; Fontão, E. Team-based learning—An approach to enhance collaboration and academic success in engineering education: A comprehensive study. Forum Educ. Stud. 2025, 3, 2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thite, S.; Ravishankar, J.; Tomeo-Reyes, I.; Ortiz, A.M. Design of a simple rubric to peer-evaluate the teamwork skills of engineering students. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2024, 49, 623–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-K. Flipped classroom as an alternative future class model? Implications of South Korea’s social experiment. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2018, 66, 837–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleeter, C.E. Making Choices for Multicultural Education. Five Approaches to Race, Class, and Gender; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gidley, J.M.; Hampson, G.P.; Wheeler, L.; Bereded-Samuel, E. From access to success: An integrated approach to quality higher education informed by social inclusion theory and practice. High. Educ. Policy 2020, 23, 123–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguez, J.; Neri, I. Research-based learning: A case study for engineering students. Int. J. Interac. Des. Manuf. 2019, 13, 1283–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tormey, R.; LeDuc, I.; Issac, S.; Hardebolle, C.; Vonèche Cardia, I. The formal and hidden curricula of ethics in engineering education. In Proceedings of the 43rd Annual SEFI Conference, Orléans, France, 29 June–2 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cotton, D.; Winter, J. “It”s not just bits of paper and light bulbs’: A review of sustainability pedagogies and their potential for use in higher education. In Sustainability Education: Perspectives and Practice Across Higher Education; Jones, P., Selby, D., Sterling, S., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Feldman, I.; Libman, Z. One size does not fit all: Educational assessment in a multicultural and intercultural world. Intercult. Educ. 2022, 33, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser Abu-Alhija, F. Large scale testing: Benefits and pitfalls. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2007, 33, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipos, Y.; Battisti, B.; Grimm, K. Achieving transformative sustainability learning: Engaging head, hands and heart. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2008, 9, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J. Seven recommendations for creating sustainability education at the university level. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2005, 6, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, S.; Metzger, E. Barriers to learning for sustainability: A teacher perspective. Parry Metzg. Sustain. Earth Rev. 2023, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, H.H.; Sears, D.A.; Maeda, Y. Effects of small-group learning on transfer: A meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 27, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menekse, M.; Purzer, S.; Heo, D. An investigation of verbal episodes that relate to individual and team performance in engineering student teams. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2019, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).