Abstract

Digital transformation (DT) has become a strategic priority for global ports; however, many in developing countries, including Indonesia, face challenges in translating digital initiatives into measurable business performance (BP). This study examines the impact of DT on BP through the mediating roles of supply chain integration (SCI) and operational performance (OP) within Indonesian ports, using the Dynamic Capabilities Theory (DCT) framework. A quantitative survey of 128 operational managers from state-owned ports was analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modeling. The findings reveal that DT significantly improves SCI and OP, both of which positively influence BP. Moreover, SCI and OP jointly mediate the DT–BP relationship, highlighting that digital technologies create value only when integrated into coordinated processes and operational routines. The study underscores that DT should be managed as a strategic transformation aligning technology, operations, and interorganizational collaboration. For port managers, strengthening digital connectivity across internal and external networks, supported by governance and incentive mechanisms, is essential to enhance visibility, responsiveness, and resilience. Theoretically, this research advances DCT by demonstrating how DT functions as a reconfiguring capability realized through SCI and OP, providing empirical insights from developing-country port contexts.

1. Introduction

In the global landscape, digital transformation (DT) has evolved from a technological trend into a strategic imperative, reshaping industries and redefining sources of competitive advantage. Across regions and sectors, firms are compelled to reconfigure their operations and business models to keep pace with the accelerating digital economy [1,2]. Yet, despite its global momentum, the outcomes of DT remain paradoxical, as organizations often struggle to translate digital investments into measurable business performance (BP). Previous studies have revealed a non-linear relationship between digitalization and BP, with digital business alignment and external social capital acting as positive moderators [3]. Global evidence further suggests that although many firms have invested heavily in DT, they have often failed to capture its full value. For example, previous research indicates that no more than roughly 30% of DT initiatives achieve their expected outcomes, revealing a continued disconnect between digital strategy design and its execution in practice [4,5]. This indicates the need for approaches that bridge the gap between strategy formulation and execution, particularly through integrative mechanisms in supply chains and operational performance [6].

Prior literature has emphasized that DT can improve supply chain efficiency and performance, but these benefits are not automatic. Gains are realized only when DT is accompanied by effective integrative mechanisms. While automation and data integration contribute positively, digital technologies alone are insufficient without broader transformation strategies [7]. DT has been shown to enhance governance and market competitiveness [8], while advanced technologies such as blockchain, big data analytics, and IoT strengthen sustainable supply chain management and drive BP [9]. This challenge becomes even more apparent in sectors that depend on intensive multiactor coordination where DT remains at early or intermediate maturity and is hindered by issues of technological integration, data standardization, and stakeholder connectivity, all of which limit the ability of digital initiatives to deliver meaningful operational improvements [10,11]. To bridge the gap between digital potential and realized outcomes, researchers have increasingly examined the mediating roles of supply chain integration (SCI) and operational performance (OP) as critical mechanisms linking DT to BP. For instance, studies in Indonesia’s food and beverage industry found that digital supply chains and SCI significantly influenced OP, which in turn contributed to business outcomes [12]. Similarly, research in Indonesia demonstrated that SCI enhanced both operational and financial performance [13]. However, limited research has explored how SCI and OP act as transformative mechanisms in bridging DT and BP, particularly in developing countries such as Indonesia.

The significance of examining these relationships, particularly in the Indonesian context, becomes salient given the country’s ongoing yet uneven progress in port digitalization. Although the Container Port Performance Index 2023 report by the World Bank highlights notable improvements—such as the rapid rise of Tanjung Priok Port (Indonesia’s largest container port) and efficiency gains following the deployment of the Pelindo Terminal Operating System–Multipurpose (PTOS-M) in Tanjung Perak Port, Surabaya—these achievements primarily reflect observable performance outcomes rather than the organizational mechanisms that produce them [14]. As an archipelagic nation whose economic cohesion depends almost entirely on maritime circulation, Indonesia faces a troubling paradox: despite ambitious digitalisation agendas and its structural reliance on ports to connect more than two thousand dispersed coastal nodes, the country’s maritime logistics system continues to suffer from entrenched bottlenecks, high logistics costs, and eroding competitiveness—clear evidence that current digital initiatives remain far from delivering the systemwide performance improvements they are envisioned to achieve [10,15].

This misalignment becomes even more evident when considering the scale of Indonesia’s port system: Inaportnet has been deployed in 264 government-operated seaports in 2024, but is fully integrated with the national licensing backbone in only 46 locations [16]—an extremely small fraction of the country’s 2154 ports, which include major commercial hubs, hundreds of community serving noncommercial ports, and nearly a thousand specialized industrial terminals [17]. This stark disparity illustrates how enormous the challenge is to achieve coherent, nationwide digital coordination across such a vast and fragmented archipelagic network. Importantly, these structural realities align with patterns commonly observed across developing-country port systems, where uneven digital maturity, infrastructural gaps, and fragmented governance arrangements differentiate them markedly from the more standardized and technologically consolidated environments found in advanced economies [18,19,20]. Such conditions highlight that improvements in port performance cannot be attributed solely to technological deployment, because the broader institutional, infrastructural, and inter-organizational coordination deficits continue to mediate—and often constrain—the actual outcomes of digitalisation efforts. These structural constraints ultimately manifest as deficiencies in both inter-organizational integration and operational consistency, suggesting that SCI and OP function as the proximate mechanisms through which digitalisation succeeds or fails to translate into performance gains. Therefore, SCI and OP are incorporated into the analytical framework because they function as the critical mechanisms that translate digital transformation from mere technological adoption into actual performance outcomes within Indonesia’s fragmented port system.

Recent empirical studies demonstrate that digitalization does not guarantee performance improvement by itself. Instead, its benefits materialize more reliably when digital initiatives are accompanied by robust SCI and operational alignment. For example, digitalization positively influences firm performance indirectly through SCI [21,22,23], while another study finds that supply chain reconfigurability significantly amplifies the impact of digital transformation on supply chain performance [24]. These findings mirror Indonesia’s port sector structural conditions, reinforcing that SCI and OP should be theorized as mechanisms, not peripheral factors, in analyzing how digital transformation leads to business performance. Accordingly, Indonesia becomes a theoretically and empirically salient research site: as a developing maritime economy with highly heterogeneous technological readiness, the translation of digital transformation into improved SCI, OP, and BP cannot be assumed—making the examination of SCI and OP as mediating mechanisms essential for explaining why some digital initiatives generate meaningful performance improvements while others yield limited or inconsistent outcomes across its diverse port organizations.

Dynamic capabilities theory provides a useful lens for explaining how firms sustain competitive advantage through the core processes of sensing opportunities, seizing them, and reconfiguring resources, as articulated in the foundational work of Teece [25]. Studies have shown that strategic routines, integrated value chains, and sustainability-oriented transformations enhance the development of dynamic capabilities [26,27]. Yet, their impact on performance is complex: sensing and reconfiguring sometimes yield negative effects, while seizing is positively associated with performance [28]. For example, a study found that frequent reconfiguring without formal structures can generate internal confusion and inconsistent operational decisions [29]. Conversely, other studies highlight that SCI and OP, when positioned as mediators, can significantly enhance BP [12,13]. The key unresolved gap is that prior studies have not jointly examined SCI and OP as the core mechanisms that explain why digital transformation often fails to translate into business performance in developing-country port systems. Accordingly, this study advances the conversation by framing SCI and OP as the combined pathways through which digital transformation yields performance outcomes—an angle not previously articulated in the literature.

Theoretically, this research advances the application of DCT in DT contexts by demonstrating how SCI and OP connect DT to BP. Practically, it provides port managers with insights for designing integration strategies that transform digital investments into long-term performance gains, while also informing policymakers on how to accelerate port digitalization as part of Indonesia’s maritime economic development agenda. Based on this background, the study addresses the following research questions:

RQ1. How does DT affect SCI, OP, and BP in Indonesian ports?

RQ2. To what extent do SCI and OP mediate the relationship between DT and BP?

This study finds that DT significantly enhances BP in Indonesian ports, primarily through the mediating roles of SCI and OP. The strongest pathway is sequential: DT improves SCI, which then enhances OP, translating digital capabilities into tangible performance gains and underscoring the importance of aligning digital initiatives with SCI and OP. These findings suggest that port managers and policymakers should prioritize integrated digital and operational strategies to maximize performance outcomes.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature, hypotheses development, and research model. Section 3 presents the research methodology. Section 4 reports the empirical results, followed by discussion. Finally, Section 5 provides the conclusion, along with the theoretical and managerial implications, limitations, and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Dynamic Capability Theory (DCT)

DCT explains how businesses sustain competitive advantage in dynamic environments by sensing opportunities, seizing them, and reconfiguring assets [26,30]. These processes are central to strategy development, particularly in the global context where firms must continuously adapt [26,31]. Compared with the traditional Resource-Based View, which has been criticized for its static orientation, DCT offers a more dynamic explanation by focusing on how firms continuously reconfigure resources in response to turbulence [32]. Research has therefore focused on how organizations not only respond to but also shape environmental change to maintain competitiveness [33]. The development of dynamic capabilities is closely linked to sensing opportunities and fostering organizational learning [34]. Both exploitative and explorative learning influence this development, with strategic leadership playing a pivotal role in guiding the process [35]. Different forms of learning and leadership styles contribute to distinct capabilities depending on organizational context, underlining the multifaceted nature of dynamic capabilities. Nevertheless, the extent to which these capabilities can be developed may vary across industries, suggesting that DCT should be interpreted not as a universal prescription but as a contingent framework shaped by context [36,37].

Building on this foundation, DT is reshaping business operations and supply chain management, requiring firms to cultivate dynamic capabilities that allow them to sense and seize digital opportunities [38]. Key technologies such as big data analytics, blockchain, artificial intelligence, and the Internet of Things (IoT) have become central enablers of this process [39]. To generate value, organizations must align their digital strategies with broader business objectives, focusing on both customer orientation and technological innovation as drivers of competitive advantage [40]. Embedding these technologies in supply chain processes enhances operational efficiency, facilitates monitoring and control, and supports environmentally sustainable practices [9]. Although prior studies have acknowledged the importance of resources, the evidence increasingly indicates that without dynamic capabilities, such resources alone rarely translate into sustainable performance outcomes [41]. In this logic, DT represents the sensing of opportunities, SCI embodies the seizing of those opportunities, OP serves as the bridging outcome, and BP reflects the ultimate capture of value, which together demonstrate how DCT provides a coherent framework for this study. Achieving such transformation requires the establishment of specific routines, including cross-industry digital sensing, the development of digital strategies, and the creation of integrated infrastructures [38]. This process extends beyond the adoption of technologies to embedding them into organizational routines and supply chain relationships, thereby enabling value capture and long-term performance improvement [9,40].

2.2. Digital Transformation (DT)

DT in ports goes far beyond the mere adoption of technology. It reshapes how ports manage their operations, interact within supply chains, and create value for stakeholders. Smart gate systems, for instance, have already demonstrated their ability to improve efficiency [42]. Yet, implementation is rarely straightforward since it often encounters inter-institutional barriers and issues of system ownership [43]. In other words, DT in ports moves in parallel with structural challenges that require a rethinking of how multiple actors work together.

Success in this transformation is not determined by technology alone. It also depends on supporting factors such as the availability of environmentally friendly supply chain information platforms, intelligent vessel scheduling, and digital carbon emission monitoring [44]. However, while many of these initiatives are profit-oriented and aligned with business strategies, conflicting stakeholder interests remain a persistent challenge. This uncertainty regarding the actual benefits—driven by incomplete information and differing expectations among stakeholders—makes it necessary for firms to undertake a more careful and comprehensive economic evaluation before committing to digital investments [45]. In practice, ports must therefore go beyond efficiency-driven agendas by actively building consensus among stakeholders, mobilizing resources, and developing transparent monitoring mechanisms [43].

The challenges become even more pronounced in developing countries, where institutional requirements, limited stakeholder awareness, and the absence of common standards stand in the way of integration [46]. Such conditions frequently produce mismatches between customer expectations and how SCI is perceived, leading to inefficient resource allocation and negative user experiences [47]. At the same time, ports have evolved from simple nodes of cargo handling into essential hubs within global supply chains, shaping logistics patterns and economic flows [48]. This expanded role calls for a more adaptive and collaborative model of integration so that digital initiatives can be translated into long-term business performance.

From a theoretical standpoint, the concept of dynamic capabilities offers a useful lens to understand these dynamics. Recent studies show that the ability to sense opportunities, seize them through strategic allocation of resources, and reconfigure operational processes has a direct impact on port performance and resilience in the face of supply chain disruptions [49,50]. In the case of Chinese ports, DT has also been found to stimulate technological innovation while strengthening operational resilience by aligning human, technological, and informational resources [51]. Through this perspective, port digitalization is not a one-time technological project but a continuous process that demands responsiveness to a changing environment.

2.3. Business Performance (BP)

BP in the context of port management reflects the extent to which ports are able to achieve their strategic objectives through the attainment of both financial and non-financial indicators [52,53,54]. From a financial perspective, common measures include revenue growth, profit margins, cost reduction, revenue growth, and berth utilization [55,56]. Yet recent research shows that business success cannot be reduced to financial outcomes alone. Non-financial dimensions such as customer satisfaction, innovation, reputation, and service quality play a critical role in sustaining long-term competitiveness [57,58]. Taken together, port performance should be understood as a balance between financial stability and the capacity to generate sustainable value for stakeholders.

The multiplicity of actors and interests embedded in port ecosystems further adds to the complexity of managing BP. Challenges extend beyond cost efficiency to include service speed, punctuality, and reliability in daily operations [59]. A systems thinking approach highlights that physical infrastructure, information technologies, service procedures, and human capital interact in shaping performance outcomes [54,60]. Similar arguments are presented by Han [61] and Fahim et al., [62], who note that ports increasingly function as strategic nodes within global supply chains. These insights emphasize that meaningful improvements in port performance can only be achieved when the different elements of the system operate in alignment.

DT has introduced a new dimension to the debate on port business performance. The adoption of technologies such as big data, blockchain, automation, and the IoT has been shown to enhance efficiency while strengthening transparency and operational reliability [63,64]. The concept of smart and sustainable ports further underscores the importance of integrating economic, social, and environmental dimensions into performance measurement [65,66]. Within this perspective, the physical internet highlights the role of network connectivity, reliable information systems, and consistent service quality as critical factors in attracting port users [62]. This shift illustrates that port competitiveness depends increasingly on the ability to manage technological change while adapting to the demands of global supply chains.

The impact of port performance also extends beyond operational boundaries to influence national trade dynamics. Evidence from African countries demonstrates that efficiency gains in port operations reduce logistics costs and stimulate export growth, while inefficiencies create structural barriers to trade [67]. Bouazza et al. [68] similarly argue that maritime connectivity helps lower global trading costs and reinforces national competitiveness. This perspective positions port performance as a strategic economic concern rather than merely an internal managerial agenda. In a globalized and digitized environment, innovation, collaboration across stakeholders, and adaptive capacity are increasingly central to ensuring sustainability and to strengthening the contribution of ports to national competitiveness [69].

2.4. Supply Chain Integration (SCI)

SCI refers to the degree to which a firm strategically collaborates with its main supply chain partners and manages intra- and inter-organizational processes to achieve efficient and effective flows of products, services, information, and financial resources, ultimately maximizing value to customers [70,71,72,73]. The growing attention to SCI in both academia and practice reflects its critical role in achieving operational excellence and competitive advantage in dynamic markets [72,74]. Over time, the literature has evolved from viewing SCI as a single-dimensional construct toward a multidimensional concept that encompasses both internal and external integration [75]. This multidimensional nature enables firms to synchronize decision-making and information sharing with suppliers and customers, facilitating real-time coordination and performance improvements [13,76,77,78,79]. In recent perspectives, SCI is also seen as a key enabler of dynamic capabilities, as it strengthens a firm’s ability to sense, seize, and reconfigure resources in response to environmental volatility [80,81]. Furthermore, SCI provides the micro-foundations of dynamic capabilities by fostering cross-functional learning, coordination, and adaptive processes that allow supply chain members to co-evolve with market and technological changes [80]. As a result, SCI not only serves as a mechanism for operational efficiency but also as a strategic capability that supports organizational agility and long-term competitiveness in complex supply networks.

In the port context, SCI is increasingly recognized as a key element for enhancing efficiency and operational excellence through collaboration, information sharing, and digital technology adoption. The main focus of integration within ports lies in the ability of multiple stakeholders such as port authorities, terminal operators, and logistics providers to coordinate the flow of information and activities in a unified manner. Previous research indicates that effective information integration strengthens both operational and financial performance by improving speed, accuracy, and transparency in processes [82,83]. Furthermore, factors such as relationship management, strategic alignment, and organizational commitment play crucial roles in the success of integration within port supply chains [84]. With technological advancements, the adoption of artificial intelligence, machine learning, big data, and the IoT has facilitated cross-system integration in the maritime sector, enabling real-time, data-driven decision-making to enhance safety and operational efficiency [85,86]. In addition, the use of blockchain technology in maritime supply chains has been increasingly recognized for improving transparency and data reliability while reducing behavioral uncertainty among business partners [87,88]. Therefore, SCI in ports represents not only the coordination of physical and informational flows among logistics actors but also a broader DT that connects diverse systems and technologies to strengthen competitiveness and ensure sustainable port operations [82,87].

2.5. Operational Performance (OP)

OP describes how effectively an organization manages and executes its operations to achieve strategic goals by ensuring timely delivery, minimizing process delays, optimizing resource use, and maintaining cost efficiency, which together form a foundation for competitive advantage [89,90,91]. Within the framework of the DCT, OP is understood as an outcome of an organization’s dynamic capability to sense environmental changes, seize emerging opportunities, and reconfigure its resources in response to rapid transformation [30,92,93]. The development of digital capabilities, including sensing, organizing, and restructuring processes, forms a critical foundation for improving operational outcomes [93,94]. Consequently, OP is not only driven by technical efficiency but also by the organization’s adaptive capacity to respond to market dynamics and technological advancements.

When viewed through the lens of dynamic capabilities, the port sector exemplifies how OP underpins the continuity of logistics flow, the reduction in vessel turnaround time, and the optimal employment of port assets [95,96]. The growing integration of DT and advanced technologies has reshaped how ports manage their operational activities. Digital twin applications, for instance, enable real-time monitoring and data-driven decision-making within container terminals, which enhances efficiency and resource allocation [96,97]. Studies on smart port initiatives, particularly in Korea, have revealed significant improvements in operational efficiency where digital technologies serve as the primary enabler of performance gains [98,99]. Nonetheless, several challenges remain, including limited system integration, organizational resistance, and a lack of cross-departmental coordination, which can constrain the success of digitalization efforts [95,100]. Leadership capability, strategic direction, data quality, and stakeholder collaboration are therefore essential determinants of successful operational improvement [101]. Furthermore, the interaction between lean practices and digitalization has been shown to strengthen organizational learning systems and foster continuous efficiency enhancement [102]. Through an adaptive and collaborative approach, bulk ports can better manage operational complexity, reinforce competitiveness, and achieve sustainable performance advantages. Moving on we further develop the hypothesis of the study as captured in Figure 1.

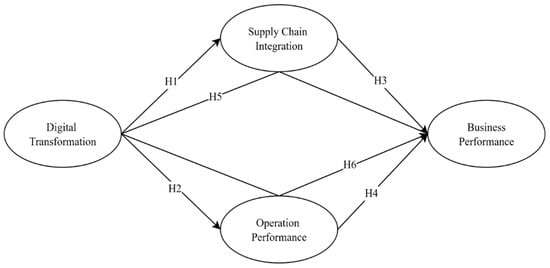

Figure 1.

Research model and hypotheses.

2.6. Hypotheses Formulation and Development of a Conceptual Model

DT acts as a critical catalyst for SCI and performance improvement through the application of advanced technologies. In the context of modern supply chain management, DT enables broad collaboration across organizations by utilizing technologies such as big data analytics, blockchain, artificial intelligence, machine learning, and the IoT [39]. Prior studies indicate that DT significantly and positively influences SCI and overall sustainable supply chain performance, with SCI serving as a partial mediator between DT and BP [103]. Additional empirical evidence confirms that DT within supply chains strengthens integration, agility, and resilience, with more pronounced effects among firms that have achieved higher levels of digital maturity [79]. Consistent with these findings, Kamble et al. [104] demonstrated that blockchain technology contributes positively to sustainable supply chain performance, with SCI functioning as a significant and full mediating variable.

Nevertheless, the effectiveness of SCI often encounters considerable obstacles, especially in developing economies. The port sector provides a clear illustration of how integration challenges emerge as a result of DT implementation. Branco et al. [47] observed that seventy-six percent of port operator customers in Brazil experienced a mismatch between strategic interests and perceived levels of SCI, mainly due to inequitable operational decision-making and negative experiences among supply chain partners. Therefore, understanding how DT operates in developing countries is essential to explain variations in SCI effectiveness that arise from differences in organizational capabilities and institutional settings. Within the scope of port management, dynamic capabilities—particularly strategic agility, innovation ecosystems, and organizational redesign—are essential for the successful realization of DT in maritime container shipping [105].

Thus, while DT encourages the advancement of SCI, its success largely depends on an organization’s ability to cultivate dynamic capabilities that allow it to overcome contextual and institutional barriers.

Based on this discussion, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1.

DT has a significant effect on SCI.

After discussing the role of DT in SCI, it is equally important to understand how DT contributes to improving OP, particularly within the port context. In this sector, DT leverages advanced technologies to optimize operations and enhance competitiveness through the implementation of digital systems and data-driven decision-making [47,106,107]. Studies on port companies in developing economies reveal that DT enhances operational resilience by coordinating human, informational, and technological resources, while technological innovation capacity serves as a crucial mediating mechanism, even though diminishing effects are observed among large port operators [51,97]. These findings indicate that DT not only improves process efficiency but also strengthens the organization’s adaptive capacity. DT further provides higher levels of transparency, control, and data-driven decision-making through essential requirements such as situational awareness, comprehensive data analytics, and multi-stakeholder collaboration interfaces [108]. This highlights the importance of digital readiness and adequate standardization, since DT implementation often encounters challenges related to the lack of standards and inconsistent terminology across the industry [95,109,110]. The successful realization of DT in maritime operations requires specific organizational capabilities and strategic approaches. Dynamic capabilities such as sensing, seizing, and transforming are proven to be vital for container shipping companies, with strategic agility, innovation ecosystems, and organizational restructuring serving as key enablers [105,106].

However, in developing countries, DT often faces inter-agency barriers, system ownership disputes, resistance to change, lack of adequate training, cultural resistance, and political interference in port governance [43,107,111,112,113]. These constraints prevent DT implementation from always yielding optimal operational outcomes, as institutional complexity and coordination barriers hinder the effective utilization of digital technologies. Therefore, the effectiveness of DT in enhancing OP depends greatly on an organization’s digital capabilities, including coordination, internal communication, and efficient information management [4,114,115]. Moreover, coordination mechanisms and social norms act as boundary conditions that strengthen the relationship between DT and OP in shipping firms [116]. The existence of this research gap highlights the need for further investigation to understand how DT can be effectively implemented to improve OP in ports within developing economies, where institutional factors and organizational capabilities interact in complex ways. Accordingly, DT serves as a key driver of OP improvement through more effective resource coordination, data-based decision-making, and greater flexibility and transparency in operational processes.

Based on this discussion, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2.

DT has a significant effect on OP.

SCI has consistently shown a positive relationship with BP across diverse industrial contexts. Meta-analytic evidence confirms a significant positive correlation between SCI and firm performance, emphasizing that strong coordination and collaboration among internal functions and external partners directly contribute to improved business outcomes [13,117,118,119,120]. Furthermore, studies conducted in developing countries indicate that internal integration promotes external integration, which in turn enhances firm performance both directly and through mediation effects [21,72,121]. In the maritime industry, external integration exerts a greater influence on BP than internal integration, while the synergy between the two produces the highest level of organizational benefits [109,122]. At a global scale, the integration of logistics and procurement provides strategic advantages, including cost reduction, improved access to technology, greater consistency in procurement processes, stronger supplier relationships, and enhanced information sharing, which collectively strengthen supply chain performance and organizational competitiveness [123]. Taken together, these findings underscore that SCI plays a fundamental role in driving operational excellence and sustainable business growth across industries.

Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3.

SCI has a significant effect on BP.

OP is widely recognized as a critical link between port strategies and BP. Prior study highlight that sustainability practices significantly moderate the relationship between operational competitiveness, particularly efficiency and service quality, and overall performance. Building on this perspective, the improvements in operational processes such as speed, reliability, and service quality are directly associated with financial and nonfinancial business outcomes [124]. A systematic review of port literature found consistent evidence of this relationship and emphasized the importance of sustainable operational practices in enhancing overall BP [125]. In a similar vein, conceptual analyses and simulation studies on sustainability interventions in port operations have shown that efforts improving efficiency and reducing disruptions contribute to stronger BP both at the organizational and network levels. Furthermore, research in supply chain and quality management confirms that strong OP capabilities translate into better BP through improved stakeholder trust and service quality, offering a clear mechanism through which OP positively affects BP [124,126,127].

Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4.

OP has a significant effect on BP.

Recent studies indicate that SCI plays a crucial role in strengthening and moderating the relationship between DT and BP. Empirical findings reveal that DT and SCI together form the foundation for improved supply chain efficiency and superior business outcomes, where SCI acts both as a mediator and a moderator [8,76,103]. This perspective is reinforced by evidence showing that supply chain digitalization positively moderates the relationship between SCI and BP by fostering ethical, transparent, and efficient management practices [21]. In the port industry, the integration of DT into operational and managerial systems has been shown to enhance coordination, cargo throughput, and competitiveness, suggesting that SCI serves as a key mechanism linking DT efforts to measurable business results [11,45,51]. Collectively, these findings emphasize that the success of DT in achieving better business outcomes depends on how effectively SCI is internalized and leveraged across port operations and inter-organizational networks.

Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 5.

SCI significantly mediates the relationship between DT and BP.

OP serves as a crucial mediating mechanism linking DT to BP. Empirical evidence demonstrates that DT enhances BP through the improvement of operational efficiency, internal communication, and coordination capabilities, enabling firms to transform digital initiatives into tangible business value [116,128,129]. In the port industry, the integration of digital systems has been shown to improve operational flow, cargo handling, and resource utilization, thereby mediating the effect of DT on BP through enhanced operational resilience and efficiency [45]. Similarly, research highlights that technological innovation and operational resilience act as key channels through which DT positively influences organizational outcomes, particularly during supply chain disruptions [51]. When OP is well developed, digital technologies can be absorbed and reconfigured into daily processes, reinforcing strategic alignment and improving decision-making effectiveness. This indicates that the success of DT in achieving sustainable business outcomes depends largely on the maturity of OP as a mediating capability that translates digital resources into superior performance.

Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 6.

OP significantly mediates the relationship between DT and BP.

3. Materials and Methods

This study uses a quantitative survey design to examine the causal relationships among four main constructs: DT, SCI, OP, and BP. The research team builds the model based on the DCT, which explains how port organizations strengthen their ability to respond to environmental changes through technology adoption and supply chain process integration within the port management context. This theory provides a relevant foundation to understand how DT and SCI improve OP and BP in the port industry. The research targets port field managers from Indonesian State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) who manage operational activities and implement digital systems. The team applies a purposive sampling method and selects respondents with at least three years of experience in port management and involvement in operational decision-making. The core enterprise variables, DT, SCI, OP, and BP, were operationalized using primary survey data obtained from managerial respondents across Indonesian port organizations. From a total population of 191 managers, the minimum required sample size of 128 was calculated using the Slovin formula to meet the statistical power requirements of PLS-SEM. Data were collected through a mixed-mode survey administration (e-forms and paper-based distribution) to ensure adequate coverage across port service divisions. All constructs were measured reflectively using validated multi-item scales adapted from prior empirical studies and anchored on a seven-point Likert continuum (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). Data collection was conducted between June and August 2025 across multiple ports, ensuring cross-sectional representation and reducing common operational bias.

The research team develops all construct indicators by adapting validated measures from prior studies and adjusting them to the port management context. DT is measured using five indicators widely adopted in operations, information systems, and maritime logistics studies, namely the use of digital technologies (DT1), changes in organizational structure (DT2), adaptive digital strategies (DT3), organizational culture (DT4), and human resource digital competencies (DT5) [130]. These indicators reflect the extent to which ports adopt digital technologies, integrate digital processes, and leverage data-driven systems to support operational and strategic decision-making. The construct is grounded in prior empirical studies conceptualizing DT as an organizational-level capability encompassing technology adoption, process digitalization, and digital alignment. BP is measured using five indicators widely applied in strategic management and port performance studies, namely revenue growth (BP1), profit margin improvement (BP2), market share expansion (BP3), competitiveness (BP4), and achievement of operational and financial targets (BP5) [131]. These indicators capture both financial and non-financial dimensions of port performance. The construct of SCI reflects the level of internal integration (SCI1), supplier integration (SCI2), customer integration (SCI3), and sustainability orientation (SCI4) [132], capturing how effectively ports coordinate processes across stakeholders to achieve operational coherence and long-term value creation. The construct of OP includes cost control efficiency (OP1), process productivity (OP2), service time optimization (OP3), and infrastructure utilization (OP4) [131,133,134], capturing how operational routines convert resources and processes into measurable performance improvements. These indicators together provide a comprehensive understanding of how DT and SCI influence the operational and strategic success of port-based SOEs.

In this study, the researchers employ Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) using SmartPLS 4.0 to estimate a theoretically grounded causal predictive model linking DT, SCI, OP, and BP. The model is specified through a set of linear structural equations, wherein DT functions as the exogenous construct predicting both SCI and OP. The first set of structural relations is expressed as:

SCI = β1DT + ζ1; OP = β2DT + ζ2

BP is subsequently modeled as a downstream endogenous construct influenced by both mediators, as specified below:

where β1, β2, β3, and β4 denote the structural path coefficients representing the magnitude and direction of the hypothesized relationships, and ζ1, ζ2, and ζ3 represent the disturbance terms capturing the unexplained variance in SCI, OP, and BP, respectively. This specification enables the estimation of direct, indirect, and total effects, with mediation effects calculated using the product-of-coefficients approach (e.g., β1 × β3).

BP = β3SCI + β4OP + ζ3

All latent constructs are operationalized reflectively, and the measurement model is rigorously evaluated through assessments of convergent validity, discriminant validity, and internal consistency reliability following established criteria in SEM literature. The structural model is subsequently assessed through the magnitude and significance of path coefficients, the explanatory capacity reflected in R2 values, and predictive relevance (Q2) obtained via blindfolding. Statistical inference is conducted using a non-parametric bootstrapping procedure with 5000 resamples to ensure robust estimation under minimal distributional assumptions. All respondents provided informed consent prior to data collection, and the research team ensured confidentiality and adhered to institutional ethical guidelines throughout the study.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Analysis

The study collected responses from 128 port managers. Most respondents were male (75%), reflecting the traditionally male dominated nature of port management in Indonesia. In terms of age, the majority were between 30 and 49 years old (around 66%), indicating that most participants are mid-career professionals with substantial managerial experience. Regarding education, most respondents held a bachelor’s degree (51%), followed by diploma and postgraduate degrees, showing that they possess adequate formal qualifications to support DT in port operations. Most respondents had extensive work experience, with nearly 70% having more than six years in port management. The majority worked in container terminals, bulk terminals (liquid/solid), logistics & hinterland services, and passenger terminals, representing the main operational units of Indonesian ports. Half of the respondents were employed by State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs), while others came from SOE subsidiaries (29.07%) and private partners (20%). Regionally, respondents were evenly distributed across western (Sumatra, Batam, West Java), central (Central Java, Kalimantan), and eastern (Sulawesi, Maluku, Papua) Indonesia, ensuring balanced national representation. Most participants were directly involved in digitalization initiatives, particularly in operations, as well as in planning and evaluation stages of port digital transformation projects. Detailed demographic information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic respondents.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for all measurement items used in the study. Overall, the results indicate relatively high mean scores across the core constructs suggesting generally positive managerial perceptions within Indonesian port organizations. The items measuring BP (BP1–BP5) exhibit mean values ranging from 6.09 to 6.33, with low-to-moderate standard deviations (0.78–0.95), indicating consistently strong performance assessments among respondents. DT items (DT1–DT4) show mean values between 5.69 and 6.14, accompanied by slightly higher variability (SD = 0.88–1.13), suggesting uneven digital adoption levels across port divisions. OP (OP1–OP4) demonstrates high and stable mean responses (6.09–6.16) with standard deviations below 0.92, reflecting a relatively homogeneous perception of operational efficiency. Meanwhile, SCI items (SCI1–SCI4) record mean scores between 5.87 and 6.13, with dispersion values ranging from 0.86 to 1.03, indicating moderate variability in integration practices. Across all constructs, the minimum and maximum values (1 to 7) confirm the full range of response utilization, supporting the appropriateness of the seven-point Likert scale and indicating sufficient discriminability among respondents. These descriptive statistics provide an initial overview of the respondents’ perceptions and support the subsequent reliability and validity assessments within the PLS-SEM framework.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

4.3. Measurement Model

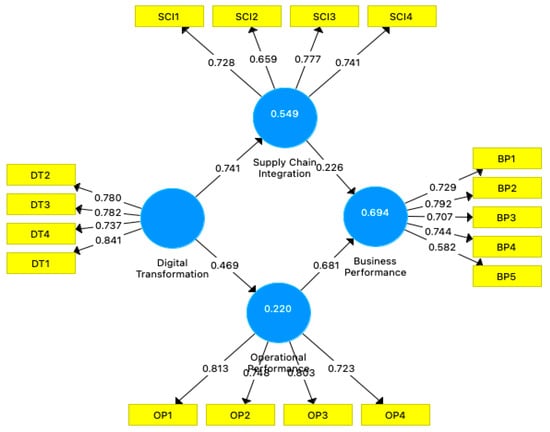

The measurement model consists of validity and reliability testing. To assess validity. We evaluated how each indicator measures its respective construct. The validity assessment included convergent validity and discriminant validity. For convergent validity, we assessed the outer loading value of each indicator. Indicators with loading values above 0.7 are considered highly satisfactory, while those above 0.5 remain acceptable [135,136,137,138]. Based on these criteria, this study adopts 0.5 as the minimum acceptable threshold. As shown in Figure 2 and Table 3, all indicators DT, SCI, OP, and BP have outer loading values above 0.5. indicating that all items meet the acceptable threshold. The outer loading values for DT range from 0.737 to 0.841, for SCI from 0.659 to 0.777, for OP from 0.723 to 0.813, and for BP from 0.582 to 0.792. Therefore, BP5 and SCI2 with an outer loading of 0.582 and 0.659, remains acceptable and theoretically consistent with the construct, confirming the convergent validity of all measurement items. In the next step, we assessed the reliability of each construct using Cronbach’s Alpha, Composite Reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE). The Cronbach’s Alpha values ranged from 0.702 to 0.793, all exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.7, which indicates internal consistency among items. The CR values ranged from 0.818 to 0.866, confirming that the constructs are reliable. Meanwhile, the AVE values ranged from 0.510 to 0.618, all above the minimum acceptable value of 0.5, thus confirming convergent validity. Therefore, all constructs are valid and reliable.

Figure 2.

Measurement model.

Table 3.

Confirmatory factor analysis.

Based on the results of the Fornell–Larcker Criterion in Table 4, the square roots of AVE for each construct are DT (0.786), SCI (0.727), OP (0.773), and BP (0.714). Overall, all values exceed the recommended threshold of 0.70, indicating satisfactory convergent validity. To assess discriminant validity, the square roots of AVE for each construct should be greater than their correlations with other constructs. The results show that most constructs meet this requirement; however, the correlation between BP and OP (r = 0.812) slightly exceeds their square roots of AVE, indicating a potential overlap between these two constructs. Similarly, the correlation between DT and SCI (r = 0.741) is relatively high, suggesting a close conceptual relationship between them. Although several constructs demonstrate strong correlations, the overall results confirm adequate discriminant validity of the measurement model. These findings suggest that DT, SCI, OP, and BP represent distinct yet interrelated dimensions within the research model.

Table 4.

Fornell–Larcker Criterion.

4.4. Structural Model

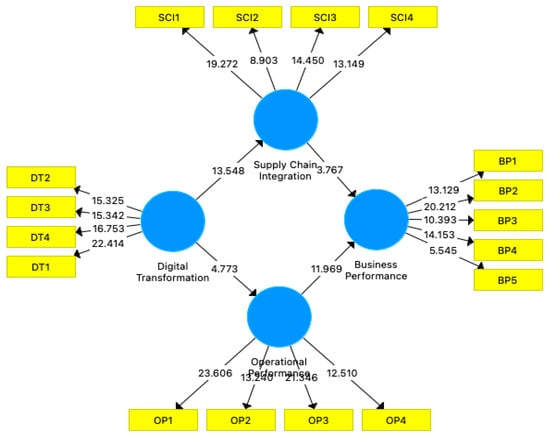

In the structural model analysis, the inner model test was conducted to evaluate the overall strength and predictive relevance of the model. This assessment includes the R2 values, predictive relevance (Q2), path coefficients, and t-statistics. The R2 values indicate the extent to which exogenous constructs explain the variance of endogenous variables, while Q2 values, derived through the blindfolding procedure, measure the model’s predictive capability [139,140]. As presented in Table 5, the model accounts for 22.0% of the variance in OP (R2 = 0.220), 54.9% in SCI (R2 = 0.549), and 69.4% in BP (R2 = 0.694). These values indicate that the explanatory power of the model ranges from moderate to substantial. Furthermore, the Q2 results of 0.119 for OP, 0.273 for SCI, and 0.327 for BP are all greater than zero, confirming that the model possesses predictive relevance. Hence, the structural model can be regarded as having satisfactory explanatory and predictive quality, and the subsequent analysis proceeds to evaluate path coefficients and significance levels to test the proposed hypotheses.

Table 5.

Q2 and R2 model.

The results of hypothesis testing indicate that all hypothesized relationships between the exogenous and endogenous constructs are statistically significant. As shown in Figure 3 and Table 6, DT has a strong and positive influence on SCI (β = 0.741, t = 13.548, p < 0.001) and OP (β = 0.469, t = 4.773, p < 0.001). This finding implies that ports implementing DT initiatives are more likely to strengthen supply chain collaboration and enhance internal operational efficiency. In turn, SCI significantly enhances BP (β = 0.226, t = 3.767, p < 0.001), while OP also exerts a positive and significant effect on BP (β = 0.681, t = 11.969, p < 0.001), confirming that both integration and operational excellence serve as strategic drivers of superior business outcomes. Furthermore, DT indirectly affects BP through SCI (β = 0.167, t = 3.667, p < 0.001) and OP (β = 0.319, t = 4.596, p < 0.001), emphasizing that the benefits of DT are maximized when technological investments are supported by internal capabilities and interorganizational integration. All hypothesized paths were supported, confirming that DT plays a pivotal role in enhancing SCI, OP, and ultimately BP.

Figure 3.

Structural model.

Table 6.

Results of hypothesis testing.

5. Discussion

The results of H1 indicate that DT has a significant effect on SCI. This finding confirms that the application of digital technologies effectively enhances inter-organizational coordination and process integration within port supply chains. This result is consistent with prior empirical studies showing that higher levels of digital maturity strengthen collaboration and integration among supply chain actors [79,103]. In the port context, DT facilitates system connectivity among port authorities, terminal operators, and logistics service providers, enabling real-time coordination of information and operational activities [82]. From the perspective of the DCT, these findings further suggest that an organization’s ability to reconfigure digital resources is a key determinant of successful SCI. However, the novelty of this study lies in demonstrating that DT’s influence on SCI is not merely confirmatory of existing findings but contextually stronger in port operations, where inter-organizational dependencies are high and coordination failures carry immediate operational costs. Unlike prior research conducted in manufacturing or general logistics settings, the results show that DT in port ecosystems functions as a ‘coordination amplifier,’ meaning that even incremental digital improvements disproportionately enhance SCI due to the system-wide interconnectedness of port actors. This indicates that in highly synchronized environments like ports, DT establishes not only a technological foundation but also a structural capacity for simultaneous, cross-actor alignment—an effect less emphasized in earlier studies.

The results of H2 confirm that DT significantly enhances OP. This finding illustrates that adopting digital technologies in port operations transforms traditional workflows into integrated systems characterized by precision, transparency, and operational agility. When DT is embedded in daily activities, it streamlines information flows among terminal operators, logistics providers, and shipping lines, thereby reducing delays and informational uncertainty. These findings align with prior research showing that digitalized operations strengthen responsiveness and decision quality in volatile settings (e.g., [116,141]). What this study adds is evidence that digitalization in ports not only accelerates individual tasks but also strengthens the system’s ability to adjust when disruptions occur. In the port environment—where small disturbances can quickly escalate into congestion—digital systems make operational routines more elastic, enabling faster reallocation of equipment, space, and labor without the prolonged downtime typical of manual processes. This adaptability, which emerges from the continuous flow of real-time information, represents the practical capability that allows ports to sustain performance even when operating conditions shift unexpectedly—an aspect often understated in earlier studies conducted outside the port sector. In sum, the improvement in OP observed here reflects not merely the efficiency gains of automation but the development of an operational base that can learn, adjust, and stabilize performance amid uncertainty.

The hypothesis testing results for H3 show that SCI has a significant positive effect on BP. While prior research generally links SCI with improved cost efficiency and operational stability [119], the present findings extend this understanding by showing how integration among port actors directly strengthens business outcomes in an environment characterized by time sensitivity and high interdependence. In port operations—where delays, fragmented information, and coordination gaps can quickly escalate into financial losses—greater integration enables more accurate planning, faster processing, and more reliable service delivery. These improvements create tangible commercial advantages, such as higher asset utilization and more predictable revenue flows, which are particularly critical for ports in developing economies where operational volatility is common. Moreover, integration fosters stronger relational stability among terminal operators, shipping lines, and logistics partners, creating a collaborative environment that supports ongoing performance improvements. This ability to continually align resources and synchronize decisions represents the capability that allows ports to translate integration efforts into sustained business performance rather than short-term efficiency gains. Thus, SCI operates in this context not only as a coordination mechanism but as a strategic enabler that helps ports maintain value creation amid operational uncertainty.

The results for H4 indicate that OP has a significant positive effect on BP. This shows that when port operations run with fewer delays, more reliable processes, and better asset utilization, the commercial outcomes also strengthen. Prior research links operational efficiency to improved revenue and service quality [52,53], but the present study highlights how these effects materialize specifically in the port context, where small improvements in scheduling accuracy, berth productivity, or cargo cycle time can generate disproportionate financial and relational gains. Because port operations are tightly interlinked across multiple actors, enhanced operational reliability translates into fewer disruptions, more predictable service commitments, and higher throughput—all of which reinforce a port’s commercial performance. This is particularly relevant for ports in developing economies, where operational bottlenecks are more common and improvements in process discipline can immediately elevate competitiveness and strengthen customer confidence. The findings also illustrate how consistent operational performance creates a reinforcing cycle: reliable operations improve stakeholder trust, which in turn supports higher demand and more stable revenue flows. In this sense, OP functions not merely as an internal efficiency metric but as a strategic mechanism through which ports convert operational stability into sustained business performance and long-term competitive positioning.

The results for H5 confirm that SCI significantly mediates the effect of DT on BP. This indicates that although DT already contributes directly to BP, its influence becomes more effective when technological capabilities are supported by coordinated supply chain routines. DT provides the infrastructure—data visibility, predictive insights, and automated workflows—while SCI helps channel these capabilities into synchronized decisions and jointly executed processes across port actors. When integration is strong, digital information flows are more readily transformed into reliable scheduling, faster cargo cycles, and fewer coordination gaps, enabling ports to translate technological capacity into stronger commercial performance. This aligns with earlier findings [8,103] and extends them to the port context by showing that SCI strengthens the strategic impact of DT rather than serving merely as an operational add-on. In settings where coordination structures are fragmented or governance remains siloed, technological enhancements tend to operate in isolation, leading to less consistent performance outcomes. The results therefore emphasize the importance of relational and procedural alignment—such as standardized information sharing, incentive compatibility, and trustful collaboration—which facilitate the effective use of digital resources across interdependent stakeholders. These routines reflect the essence of dynamic capability, in which integration provides a foundation for continuously adapting and reconfiguring digital assets in response to operational volatility. Practically, the implication is that digital initiatives should be accompanied by deliberate integration efforts to ensure that the value generated by DT is fully strengthened and translated into improved BP.

The results for H6 indicate that OP significantly mediates the effect of DT on BP. The distinct contribution of this finding lies in demonstrating that the performance impact of DT in ports is not generated solely by technological adoption but by the extent to which digital tools are embedded into core operational routines such as vessel scheduling, cargo handling, and resource deployment [142,143]. While prior port digitalization studies have largely emphasized efficiency gains or broad strategic benefits of DT, the present analysis shows that the translation of DT into business value occurs through day-to-day operational absorption, where operational processes act as the mechanism that channels digital improvements into performance outcomes. This study therefore advances the literature by illustrating that operational routines function as adaptive capabilities that align digital resources with process level decision-making in uncertain port environments. In developing country ports where infrastructure and coordination constraints remain prominent, the mediating role of OP becomes particularly salient because improvements in reliability, workflow synchronization, and disruption handling directly strengthen business results. Accordingly, OP not only mediates but also operationalizes the adaptive capacity through which DT supports sustainable improvements in BP within dynamic and resource-constrained maritime contexts.

6. Conclusions

The study confirms that DT significantly improves SCI and OP, both of which lead to higher BP in port operations. The results demonstrate that DT influences business outcomes indirectly through these two mechanisms, showing that technology alone is not sufficient without strong process integration and operational excellence. SCI facilitates coordination, transparency, and trust among port stakeholders, while OP converts digital efficiency into tangible results such as reduced delays and optimized resource use. Together, these elements explain how DT strengthens overall BP. The findings emphasize that integrating digital systems with operational routines creates a continuous flow of information that enhances decision-making quality and service reliability. This alignment transforms DT into a strategic driver of performance rather than a stand-alone technological initiative. In the context of developing ports, such as those in Indonesia, the study underscores that DT must operate through effective SCI and OP to achieve sustainable business improvement.

Building on these results, the findings collectively emphasize that DT in port environments must be managed as a strategic process that unites technology, operations, and interorganizational coordination. For managers, the results suggest that the value of digital investment depends on the extent to which it strengthens operational capabilities and SCI. Port leaders should therefore prioritize initiatives that connect digital systems across internal units and external partners to ensure end-to-end visibility and coordination. This requires not only technological upgrades but also managerial alignment through governance mechanisms, incentive structures, and collaborative decision-making frameworks. Managers must focus on embedding digital technologies into daily operational routines such as cargo handling, vessel scheduling, and resource allocation to achieve tangible improvements in efficiency and competitiveness. Furthermore, ports in developing countries should gradually institutionalize digital practices through training, standardization, and transparent data-sharing policies to overcome capability gaps. The study implies that managerial success in DT depends less on technology adoption itself and more on the ability to integrate, adapt, and sustain those technologies within the broader port ecosystem. Hence, DT becomes a managerial discipline for resilience, responsiveness, and long-term business growth.

Beyond managerial implications, the study also provides theoretical implications. The results extend the DCT by demonstrating how DT acts as an enabler of sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring capacities within port ecosystems. The findings reveal that SCI and OP are not only performance outcomes but also mediating mechanisms through which dynamic capabilities are materialized. This enriches the DCT framework by showing that DT transforms static resources into adaptive routines that enhance agility and strategic renewal. In developing-country contexts, where resource constraints and institutional gaps are more pronounced, the capacity to reconfigure digital assets becomes a critical determinant of competitiveness. The study contributes to the literature by positioning DT as both a technological and organizational capability that bridges digital infrastructure with strategic performance outcomes. It underscores that dynamic capabilities manifest not in isolated technological advancements but in the continuous orchestration of data, knowledge, and collaboration among stakeholders. Therefore, the research advances DCT by embedding DT into the core logic of capability evolution, particularly in industries characterized by high uncertainty and interdependence such as ports.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design reflects the condition of port operations at a single point in time, which limits the ability to capture the long-term dynamics of DT and BP. The use of self-reported survey data may also introduce subjective bias, as respondents might provide answers that align with organizational expectations rather than actual practices. Moreover, the research context is confined to Indonesian ports, many of which are state-owned or subsidiaries of state enterprises, making the generalization of findings to other countries or different logistics sectors less straightforward. Another limitation lies in the scope of the model, which includes only four key constructs (DT, SCI, OP, and BP), while other relevant variables such as organizational culture, leadership capability, and stakeholder engagement were not incorporated. These factors could enrich our understanding of how DT unfolds in complex port environments. Future studies are therefore encouraged to explore these dimensions to build a more comprehensive framework of DT in the port context, particularly in developing economies where institutional and managerial capabilities continue to evolve.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.W.P., M.J.S. and L.D.; methodology, B.W.P., M.J.S. and L.D.; software, B.W.P.; validation, B.W.P. and M.J.S.; formal analysis, B.W.P.; investigation, B.W.P.; resources, B.W.P. and A.P.; data curation, B.W.P. and M.J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, B.W.P. and L.D.; writing—review and editing, A.A.A.P.A.; visualization, A.A.A.P.A.; project administration, B.W.P. and A.P.; funding acquisition, B.W.P. and A.P.; translation, A.A.A.P.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (Ethics Committee) of the Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Ciputra, Indonesia (protocol code 289/EC/KEPK-FKUC/X/2025, approved on 27 October 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. All participants completed the informed consent form, which stated that participation was voluntary, responses were fully anonymized, and that anonymized responses could be used for academic publication. No personally identifiable information was collected, and all data were analyzed anonymously.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are restricted due to privacy and ethical regulations imposed by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medi-cine, Universitas Ciputra. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the port management professionals from Indonesian State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) who participated in this study for their valuable time and insights.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Ari Primantara is employed by Petrokimia Gresik. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Khoshroo, M.; Talari, M. Discovery and analysis of global studies trend on digital transformation strategy: Exploring challenges and opportunities. Kybernetes 2024, 54, 5482–5507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quynh, T.N.N.; Buics, L. The Evolution of Digitalization Transformation and Industry 4.0 in Supply Chain Management: A Systematic Literature Review. Eng. Proc. 2024, 79, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Cai, Z.; Chen, J. The Non-Linear Impact of Digitalization on the Performance of SMEs: A Hypothesis Test Based on the Digitalization Paradox. Systems 2024, 12, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Moaid, N.A.A.; Almarhdi, S.G. Developing dynamic capabilities for successful digital transformation projects: The mediating role of change management. J. Innov. Entrep. 2024, 13, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, K.; Kho, H.; Choi, Y.; Lee, S. Determinants for Successful Digital Transformation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correani, A.; De Massis, A.; Frattini, F.; Petruzzelli, A.M.; Natalicchio, A. Implementing a Digital Strategy: Learning from the Experience of Three Digital Transformation Projects. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2020, 62, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atieh, A.A.; Abu Hussein, A.; Al-Jaghoub, S.; Alheet, A.F.; Attiany, M. The Impact of Digital Technology, Automation, and Data Integration on Supply Chain Performance: Exploring the Moderating Role of Digital Transformation. Logistics 2025, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Fan, M.; Fan, Y. Digital transformation and supply chain efficiency improvement: An empirical study from a-share listed companies in China. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0302133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroumpoulis, A.; Kopanaki, E. Theoretical Perspectives on Sustainable Supply Chain Management and Digital Transformation: A Literature Review and a Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utama, D.R.; Hamsal, M.; Abdinagoro, S.B.; Rahim, R.K. Developing a digital transformation maturity model for port assessment in archipelago countries: The Indonesian case. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2024, 26, 101146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tian, X.; Lu, Z.; Wu, J. Impact of Digital Transformation on Sustainable Development of Port Performance: Evidence from Tangshan Port. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saryatmo, M.A.; Sukhotu, V. The Influence of the Digital Supply Chain on Operational Performance: A Study of the Food and Beverage Industry in Indonesia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, U.A.A.; Rahayu, A.; Wibowo, L.A.; Sultan, M.A.; Aspiranti, T.; Furqon, C.; Rani, A.M. Supply chain integration as the implementation of strategic management in improving business performance. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. The Container Port Performance Index 2023; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Iman, N.; Amanda, M.T.; Angela, J. Digital transformation for maritime logistics capabilities improvement: Cases in Indonesia. Mar. Econ. Manag. 2022, 5, 188–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Transportation of the Republic of Indonesia. Improvement of Maritime Transportation Logistics Services Through Inaportnet Needs to be Improved. 2024. Available online: https://dephub.go.id/post/read/peningkatan-layanan-logistik-transportasi-laut-melalui-inaportnet-perlu-ditingkatkan (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Coordinating Ministry for Maritime and Investment Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia. Strategic Plan of the Deputy for Infrastructure and Transportation Coordination 2020–2024. 2024. Available online: https://share.google/k0QbTGJJEEc3tXYBz (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Danladi, C.; Tuck, S.; Tziogkidis, P.; Tang, L.; Okorie, C. The impact of port sector reforms on the productivity and efficiency of container ports in lower-middle-income countries: A Malmquist productivity index approach. J. Shipp. Trade 2025, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keefe, D.H.S.; Jang, H.; Sur, J.-M. Digitalization for agricultural supply chains resilience: Perspectives from Indonesia as an ASEAN member. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2024, 40, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utama, D.R.; Hamsal, M.; Rahim, R.K.; Furinto, A. The effect of digital adoption and service quality on business sustainability through strategic alliances at port terminals in Indonesia. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2024, 40, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.P.; Chiu, W. Supply Chain 4.0: The impact of supply chain digitalization and integration on firm performance. Asian J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 10, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamah, E.; Alzubi, A.; Yinal, A. Unveiling the Impact of Digitalization on Supply Chain Performance in the Post-COVID-19 Era: The Mediating Role of Supply Chain Integration and Efficiency. Sustainability 2023, 16, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashat, R.M.; Abourokbah, S.H.; Salam, M.A. Impact of Internet of Things Adoption on Organizational Performance: A Mediating Analysis of Supply Chain Integration, Performance, and Competitive Advantage. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Gu, F.; He, M. The Influence of Digital Transformation on the Reconfigurability and Performance of Supply Chains: A Study of the Electronic, Machinery, and Home Appliance Manufacturing Industries in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitelis, C.N.; Teece, D.J.; Yang, H. Dynamic Capabilities and MNE Global Strategy: A Systematic Literature Review-Based Novel Conceptual Framework. J. Manag. Stud. 2023, 61, 3295–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bari, N.; Chimhundu, R.; Chan, K.-C. Dynamic Capabilities to Achieve Corporate Sustainability: A Roadmap to Sustained Competitive Advantage. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrrido, I.; Kretschmer, C.; Vasconcellos, S.; Gonçalo, C. Dynamic Capabilities: A Measurement Proposal and its Relationship with Performance. Braz. Bus. Rev. 2020, 17, 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, H.; Maurer, I.; Ebers, M. (When) Are Dynamic Capabilities Routine? A Mixed-Methods Configurational Analysis. J. Manag. Stud. 2022, 59, 1531–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prester, J. Operating and Dynamic Capabilities and Their Impact on Operating and Business Performance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Wang, T. Enhancing digital transformation: Exploring the role of supply chain diversification and dynamic capabilities in Chinese companies. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2024, 124, 2467–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correggi, C.; Di Toma, P.; Ghinoi, S. Rethinking dynamic capabilities in light of sustainability: A bibliometric analysis. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2024, 33, 7990–8016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, H.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Z.J.; Jasimuddin, S.M. Linkage between digital supply chain, supply chain innovation and supply chain dynamic capabilities: An empirical study. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2024, 35, 1200–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Souza, C.P.; Takahashi, A.R.W. Dynamic capabilities, organizational learning and ambidexterity in a higher education institution. Learn. Organ. 2019, 26, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornay-Barrachina, M.; López-Cabrales, Á.; Salas-Vallina, A. Sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring dynamic capabilities in innovative firms: Why does strategic leadership make a difference? BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2025, 28, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, J.; Zhang, S.; Trimi, S. The contingent impacts of dynamic service innovation capabilities on firm performance. Serv. Bus. 2023, 17, 819–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikalef, P.; van de Wetering, R.; Krogstie, J. Building dynamic capabilities by leveraging big data analytics: The role of organizational inertia. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellström, D.; Holtström, J.; Berg, E.; Josefsson, C. Dynamic capabilities for digital transformation. J. Strateg. Manag. 2022, 15, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavana, M.; Shaabani, A.; Raeesi Vanani, I.; Kumar Gangadhari, R. A Review of Digital Transformation on Supply Chain Process Management Using Text Mining. Processes 2022, 10, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, R.S.; Thangavelu, C.; Thangarajan, R. Strategic Orientation, Digital Transformation Capabilities, and Their Impact on Organizational Performance: A Comprehensive Analysis. J. Inf. Syst. Eng. Manag. 2025, 10, 530–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Bashiri, M.; K Lim, M.; Akpobi, T. How to improve supply chain sustainable performance by resilience practices through dynamic capability view: Evidence from Chinese construction. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 212, 107965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basulo-Ribeiro, J.; Pimentel, C.; Teixeira, L. Digital Transformation in Maritime Ports: Defining Smart Gates through Process Improvement in a Portuguese Container Terminal. Futur. Internet 2024, 16, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakita, B.M.; Helgheim, B.I.; Bråthen, S. The Principal-Agent Theoretical Ramifications on Digital Transformation of Ports in Emerging Economies. Logistics 2024, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Park, K.-S.; Su, M. Critical Success Factors for Green Port Transformation Using Digital Technology. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Xu, X. Digital transformation and port operations: Optimal investment under incomplete information. Transp. Policy 2024, 151, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.G.; Zhang, A.; Deakins, E.; Mani, V.; Shi, Y. Supply Chain Integration Barriers to Port-Centric Logistics—An Emerging Economy Perspective. Transp. J. 2020, 59, 215–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, M.; Teixeira, R.; Mir, S.; Lacerda, D.P. Barriers to the Development of Port Operator Supply Chain Integration: An Evaluation in a Developing Country. Transp. J. 2021, 60, 141–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Host, A.; Pavlić Skender, H.; Mirković, P.A. The Perspectives of Port Integration into the Global Supply Chains—The Case of North Adriatic Ports. Pomorstvo 2018, 32, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore, L.; Pai, Y.P.; Geetha, E.; Dmello, V.J.; Bidi, S.B. The impact of dynamic capabilities on shipping port performance: A serial-mediation of sustainability practices based on dynamic capability view. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Hughes, M.; Hodgkinson, I.; Hughes, P. Digital transformation of industrial businesses: A dynamic capability approach. Technovation 2022, 113, 102414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Hu, W.; Li, W.; Hu, R. Digital transformation, technological innovation, and operational resilience of port firms in case of supply chain disruption. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 190, 114811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucak, U.; Başaran, İ.M.; Esmer, S. Dimensions of the Port Performance: A Review of Literature. J. ETA Marit. Sci. 2020, 8, 214–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.W.; Lee, Y.H. Effects of internal and external factors on business performance of start-ups in South Korea: The engine of new market dynamics. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2019, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]