Abstract

The article aims to determine how ergonomic measures support the achievement of ESG goals and how ergonomics as a discipline can be used in sustainability reporting. The study was designed as a mixed-method approach, started with a systematic review of the literature conducted according to the PRISMA protocol, and was followed by a qualitative analysis of the identified literature. The search strategy was based on a combination of keywords in the areas of ergonomics and environmental management. The results of the review identify the main trends in combination of ergonomics with ESG: Ergoecology, Green ergonomics, Environmental ergonomics, and Immaterial ergonomics, as well as indicating areas of objectives particularly reinforced by ergonomic interventions and documenting examples of good practices valuable for ESG reporting. The main results of the study are as follows: (1) organizing research trends in ergonomics for sustainable development; (2) a systematizing approach to green ergonomic practice; (3) a set of ergonomic practices for sustainability that are most frequently described in the literature; and (4) a conceptual model termed the Sustainability through Ergonomic Excellence Model (StEEM). The proposed framework organizes a range of practices into seven areas of excellence and assigns the collected green ergonomic practices to them, showing their contribution to implementing ESG metrics. The research carried out indicates that the role of ergonomics is still underestimated in current reporting standards. The proposed mapping and StEEM frameworks provide a framework to facilitate the systematic integration of ergonomics into ESG strategies and reporting and to provide a structured foundation for future empirical and evaluative research.

1. Introduction

The development of research on the role of ergonomics in sustainable development is a natural consequence of the evolution of this discipline, in which harmony with nature has been postulated since the term ergonomics was coined by the Polish scientist Wojciech Jastrzębowski in 1857 [1]. He defined ergonomics as a science that serves to harmonize human work with the environment, which is consistent with the contemporary approach of integrating ergonomics with global sustainability strategies. At the beginning of its development, ergonomics focused on adapting tools and the working environment to the physical conditions of humans, and later also to their mental, social, and cultural needs. At the end of the 20th century, with the development of macroergonomics, a systemic view of organizations and the processes that occur within them emerged, thus allowing for the resolution of more complex problems at the human–technical environmental interface [2]. At the end of the 20th century, sustainability science also started to gain attention, thus significant changes were taking place in the legal and political spheres on the approach to climate—the Brundtland Report (1987) [3] introduced the concept of sustainable development, and the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro (1992) [4] established a framework for implementing sustainability in organizations. In the following years, researchers highlighted the potential for combining ergonomics with technological innovations and strategic management [5], thus strengthening its importance in the context of a knowledge-based economy. Studies have also pointed to a direct link between ergonomics and the three pillars of sustainable development: economic, social, and environmental [6,7]. The publication of the 2030 Agenda and the UN Sustainable Development Goals (2015) [8] gave these studies a new dimension, and subsequent studies clearly linked ergonomics to sustainable development, placing it at the center of the discussion on the future of work, organization, and social responsibility.

Just as industrial ergonomics has previously rationalized production and manufacturing processes in terms of human resource utilization (paradigm of saving life forces of workers), its developed systemic form has the potential to support the sustainable development of organizations or, more broadly, economic processes. Both ergonomics and sustainable development are human-centered and involve the optimization of complex sociotechnical systems, so it can be indicated that ergonomics can play an important role in supporting the transition to sustainable development [9]. However, the potential of ergonomics extends beyond social sustainability, demonstrating that many initiatives may be ineffective without ergonomics. Only a broader economic perspective, along with analysis from a human factors and ergonomics point of view, enables long-term sustainability in the environmental domain. Therefore, ergonomists must expand their competencies beyond traditional occupational health to include climate change, eco-design, and sustainable development management [10].

In many cases, however, these rather general considerations are insufficient to understand the role of ergonomics and perhaps also to design a strategy for the sustainable development of an organization using its methods. Therefore, it is worth considering how ergonomics can have a measurable impact on the individual dimensions of sustainable development. Hence, the main research question addressed in this article is as follows: how do ergonomic measures influence the achievement of goals set by ESG standards in organizations? The answer to this question can be found by answering the following specific questions:

- What are the trends in the literature regarding the relationship between ergonomics and sustainable development?

- Which ESG goals are particularly supported by actions in the field of ergonomics?

- What ergonomic practices are useful for achieving ESG goals according to the evidence-based literature?

- How can these practices be organized within companies?

The purpose of the research is to identify a gap or underestimation of ergonomics in valid mandatory and voluntary ESG standards in Europe and to identify which standard best supports ergonomics reporting. In theoretical terms, the objective of this study is to construct a conceptual framework and propose an integrative middle-range model that links concrete ergonomic interventions to specific ESG standards and reporting areas. In doing so, we aim to bridge the gap between micro-level ergonomic practices and meso-level ESG governance and reporting logics, and to provide a structured foundation for future empirical and evaluative research.

2. Materials and Methods

The study uses a systematic scoping review design aimed at conceptual model building and precise mapping of evidence. The primary objective for this was to synthesize and organize the available literature on how ergonomic measures relate to the achievement of ESG standards. Although PRISMA is most commonly associated with meta-analyses, in this paper, its framework was adopted to enhance methodological rigor, specifically to ensure comprehensiveness, reproducibility, and transparency throughout study identification, screening, and selection. These principles are foundational for authors to achieve high-quality evidence syntheses and are, at the same time, consistent with best practices for conceptual and scoping reviews. The inclusion criteria guiding the study’s in-depth qualitative synthesis and conceptual analysis required that the articles detail a specific operationalizable ergonomic intervention and articulate a logical connection between that intervention and the completion of a specific ESG standard. Literature searches were conducted in the Scopus and Web of Science databases. The search strategy was based on the combination of keywords in two main thematic areas: ergonomics and ESG, presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Keywords used in the study.

Equivalent Web of Science and SCOPUS queries used the Topic/Abstract field and combined two synonym blocks, ergonomics-related terms, and ESG-related terms as listed in Table 1, formulated as follows: TS = (<ergonomic terms from Table 1>) AND (<ESG terms from Table 1>), with phrases in quotes and OR used within each block.

The screening was conducted in stages 1 and 2. Screening—Stage 1 (preliminary). In the first stage of screening, based on titles and abstracts, we excluded records that, although captured by queries, lacked a substantive link to ergonomics. Direction descriptors included ergonomic, human factors, human-centered design, work design, and ESG. The search function was performed within Excel, followed by the revision of rejected records made by the authors themselves. At this stage, we excluded studies that met the following criteria:

- −

- Addressed ESG/sustainability (for example, environment, energy, waste, CSR, SDGs) without engaging with ergonomics/HFE;

- −

- Fell outside both domains, offering no relevant link to either ergonomics or ESG (e.g., generic proceedings descriptions, unrelated reviews, peripheral topics);

- −

- Discussed ergonomics/HFE (e.g., usability, UX, human factors, safety, cognitive load) without linking it to ESG goals or standards;

- −

- Mentioned both ergonomics and ESG without articulating how a specific ergonomic intervention fulfills an ESG requirement, standard, or metric (e.g., GRI, SDGs, S/G policies);

- −

- Consisted of conference proceedings or overviews lacking an operational connection between ergonomics and ESG.

Screening—Stage 2 (in-depth). Two authors independently read 705 abstracts and judged their usefulness for further analysis. The assessment was combined with an expert review of the abstract text, made by both authors, and generative AI support using a fixed prompt. The results (summary, expert rating, AI summary) were continuously pasted into an Excel sheet to enable categorization and comparison. Within that stage, we excluded studies that met the following criteria:

- −

- Referred to related but distinct approaches (e.g., Lean, WELL certification, workforce diversity, general well-being)

- −

- Emphasized other research areas (e.g., parametric design, multi-criteria optimization) without demonstrating a systematic role of concrete ergonomic interventions in meeting ESG requirements;

- −

- Presented case studies treating ergonomics as an ad hoc factor in a single sustainability dimension (e.g., efficiency in traditional vs. eco-friendly fishing; risk reduction in agriculture) without a systemic framing and without linking to ESG standards/metrics;

- −

- Claimed that “ergonomics/human factors” lead to “sustainable development” in general terms, but did not specify how ergonomic actions support the implementation of ESG standards/metrics in organizations.

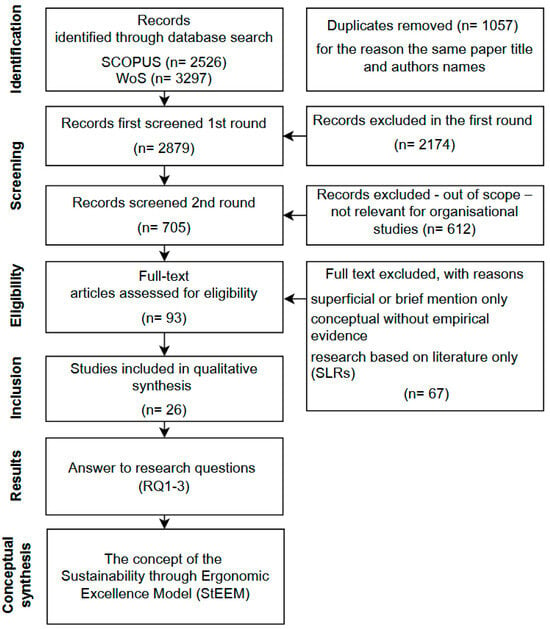

The research steps taken within the rigor of the systematic review of the literature are described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Visualization of the research activities carried out to address the research questions.

The inclusion criteria were scientific publications in English (or with an English abstract) related to ergonomics, with links to sustainable development and ESG. Table 2 presents the individual steps taken to identify the most relevant scientific works for the research problem.

Table 2.

Steps of the analysis.

Ultimately, of the 77 full-text publications analyzed, 26 articles were considered valuable in terms of the research questions/issues raised, as well as 7 systematic reviews of the literature as a background to the problem. These prior reviews were not part of our dataset and were not included in our data extraction, coding, counts, or synthesis. Our analyses in the subsequent sections are based exclusively on the 26 primary articles selected according to our inclusion criteria and cited throughout the text. In contrast, another 20 were considered to contribute partially to the research issue and were used as additional material for the analysis.

One of the key challenges during the literature review was to draw clear boundaries between relevant publications and those that only marginally referred to the problem under analysis. Many articles and studies have addressed issues related to the links between ergonomics and sustainable development, but have done so superficially or sloganistically, without an in-depth analysis of specific ergonomic measures in the context of achieving ESG goals. For this reason, publications that refer to related concepts such as Lean [11], Well certification [12], workforce diversity [13], general well-being [14], or emphasize other areas of research, e.g., parametric design [15], multi-criteria optimization [16], etc. All these publications, in a general way, suggest that the roles of ergonomics and ESG are bound. The authors of this study determined that these articles did not adequately account for the role of ergonomic measures in systematically supporting ESG objectives. Similarly, case studies focused on the use of ergonomics in specific dimensions of sustainable development, treating ergonomics as a factor in overcoming particular problems but not considering its systemic nature, were excluded. Examples of such research, which is certainly valuable from other points of view, include improving efficiency through ergonomics in traditional and more environmentally friendly forms of fishing [17] and reducing risks in agriculture [18]. The further analysis also did not take into account several studies that referred to ergonomics and human factors as a path to “sustainable development” at the general level and strongly advocated for the validity of the ergonomic approach as an essential component on the path to a broadly understood social, economic, and sustainable development [19,20,21].

Publications that were ultimately not selected for in-depth analysis also provide valuable insight into the direction of integrating ergonomic approaches with sustainable development concepts, pointing to two trends:

- −

- Modifying the ‘field’ of ergonomics and extending its applicability to the role of creating human-centered environments/organizations; thus, pointing to the potential of ergonomics in the design of integrated management systems, emphasizing the importance of human factors as an element of competitive advantage and social responsibility [22,23].

- −

- Multi-criteria optimization and functional models that have the potential to balance social, economic, and technological aspects, where the ergonomic approach is treated as an auxiliary, indicating that it considers the needs of diverse groups of recipients in different domains in a broader way [13,24].

Therefore, for the reasons mentioned above, the authors decided not to include specific publications in the in-depth analysis; they were treated instead as auxiliary sources, and their content indirectly contributed to outlining the directions for further research and reflection on the development of the concept of sustainability through an ergonomic management system and, more generally, the contribution of ergonomics in the context of achieving ESG goals. Some of the sources were also used as auxiliary material in formulating the proposed research agenda included in the final part of the article.

The next step in the research was to map ergonomic activities/approaches to ESG goals. Bearing in mind that ergonomics and human factors are a discipline that covers a wide range of approaches and issues, and that sustainability is based on many practical activities (interventions), it is reasonable to indicate which areas of sustainability reporting/tracking can be supported by the identified forms of ergonomic activities. In other words, to determine which areas of interest to companies can be supported by ergonomics, given the need to report on the classification of sustainability activities. To this end, the authors have prepared a list of numbered indicators for ESG reporting areas in accordance with CSRD and ESRS, which formed the basis for the analysis of the selected literature items. The indicators assigned to the reporting areas are described in detail in the Supplementary Materials—Table S1.

Across the 26 publications that were considered valuable, some were published in peer-reviewed journals (n = 19), and the remainder were split between book chapters in the CRC Press volume Human Factors for Sustainability (5), an edited book entry (1), and one item in a proceedings/series (1). The journal of highest use was Sustainability (7), followed by Ergonomics (4), Work (2), and Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science (2). Single appearances included Neural Computing and Applications, Acta Technica Napocensis—Series: Applied Mathematics, Mechanics, and Engineering, International Journal of Technology, and Brazilian Journal of Operations and Production Management. This pattern shows authors splitting their work between flagship HFE/ergonomics journals for theory/method contributions and an interdisciplinary sustainability journal when the emphasis is integration with SDG/ESG agendas; conceptual/programmatic pieces often appear as chapters in the CRC Press collection. The observed utility of Sustainability likely reflects this journal’s recent role in publishing cross-disciplinary studies at the intersection of management and sustainability, which are directly relevant to the research questions of the authors. The selection criteria remained topic-driven, independent of the venue.

When analyzing the literature on the usefulness of specific activities in the field of ergonomics and human factors for meeting ESG requirements, the following criteria were considered:

- −

- The validity of their statements, eliminating, in this case, so-called “wishful thinking” and statements not supported by research or relevant literature references;

- −

- the practical nature of ergonomic activities, i.e., only those items that specified a specific course of action within ergonomics were listed, rather than merely declaring the field’s general application.

The data analysis phase for this last part of our research was conducted following the coding principles and procedures of Grounded Theory. To develop a conceptually grounded transparent mapping between ergonomic practices and ESG standards, we conducted a bottom-up, inductive synthesis alongside a systematic scoping review (PRISMA for identification, screening and selection). Analysis was supported by Grounded Theory tools: open coding was used to extract recurring ergonomics to ESG links (specific practices), and axial coding to systematically organize them into higher-order categories and map them onto ESG objectives. Constant comparison and brief memo-writing were used to refine the definitions. Two authors calibrated and reconciled a shared codebook on an initial subset and then proceeded iteratively; coding decisions and summaries (including fixed-prompt AI aids) were logged in Excel for traceability. This process resulted in Map of connections between practices and individual ESG goals (Table 5). This procedure supported the development of a theory-informed model: seven higher-level “areas of excellence” that make up the integrated StEEM framework were ultimately derived from the axial categories and their interrelations. The authors do not frame the study as a full Grounded Theory; rather, we leverage its systematic coding procedures to strengthen conceptual model building and evidence mapping.

3. Review of the Literature

3.1. Identified Systematic Literature Reviews on the Role of Ergonomics in Sustainable Development

A review of the literature revealed that similar systematic reviews had previously been conducted. This also highlights the importance of the topic and the attempts of researchers to build a more structured understanding of this area, even if these attempts were undertaken by different authors using partly overlapping but not fully aligned scopes and criteria. The contribution of previous reviews was to draw attention to the relationship between ergonomics and sustainability. However, their limitations, including the use of selected databases or groups of journals and periods, and, above all, the diverse approaches to sustainability, justified the further analysis conducted in this paper. The results of this re-analysis are presented in this article. The reviews of the previously identified literature relevant to the role of ergonomics in supporting sustainability are characterized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of identified previous reviews on the role of ergonomics in sustainable development and ESG.

Table 4 also includes an article that contains a review of the literature on the research problem, which was not written in English, although the authors used English keywords, and the abstract was also written in English [29]. The list did not include items that analyzed related areas where sustainability only concerned a selected function of the company, e.g., only sustainable manufacturing or the Industry 5.0 concept, or those that took into account the role of ergonomics in an auxiliary manner (not in keywords) or did not meet the rigor of a systematic literature review, although they systematized approaches to the role of ergonomics in sustainable development [10]. The most valuable of these reviews in terms of the research trends in the role of ergonomics in sustainable development are gathered and presented in the next chapter. Identifying these reviews enabled us to integrate trends addressing the relationship between ergonomics and sustainable development—the state of the art (Section 3.2: Research trends in the role of ergonomics in sustainable development). This approach, which is somewhat unconventional for a literature review, serves to introduce a new analytical lens that synthesizes prior work and allows the reader to situate the contribution advanced by the authors of this article.

Table 4.

ESG—areas of activity with documented support for ergonomics.

Some of the reviews of the characterized literature ended with the formulation of a model or the resulting relationships and directions for future research. Other than in the next section, systematic/scoping reviews identified during the search were used only for background mapping and snowballing; they were not included in the extraction or synthesis of data for the results of the study.

3.2. Research Trends in the Role of Ergonomics in Sustainable Development

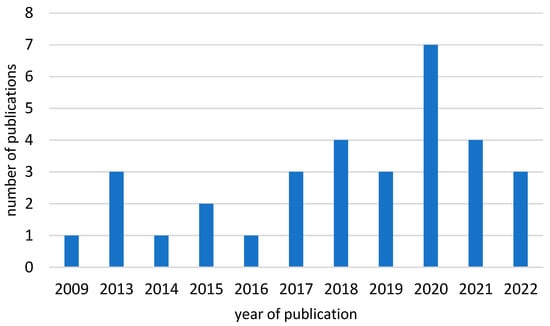

Interest in the role of ergonomics in advancing sustainability is understood in multiple ways, from strictly environmental concerns to corporate social responsibility and the responsible implementation of joined multi-actor projects. It became firmly established toward the end of the second decade of the 21st century by Thatcher, Zink, & Fischer [10]. This trend is clearly visible in the density of the identified publications shown in Figure 2 by year of publication. The subsequent decline in attention to this topic in the subsequent years can be regarded as a research gap, which this article seeks to address.

Figure 2.

Number of articles in each year identified as significant in the context of demonstrating the role of ergonomics in the implementation of ESG objectives.

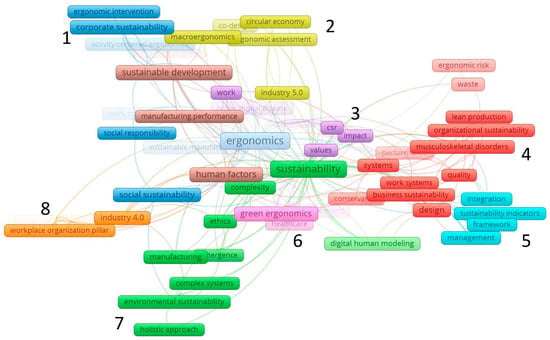

Bibliometric analysis was conducted using VOSviewer v.1.6.20, which enabled the identification of terminological links and main research trends, ordered by occurrences. The literature retrieved on the intersection of ergonomics and sustainability indicates several clusters (clusters were described by the authors to capture a common denominator for the co-occurring keywords). Starting in the top-left, (1) the blue cluster links corporate social responsibility and sustainability to activity-centered ergonomic interventions that improve working conditions; employee well-being at work is framed as a core element of an organization’s accountability to stakeholders and society. (1—corporate sustainability; ergonomic intervention; activity-centered ergonomics; work conditions; social responsibility). (2) The yellow cluster approaches organizational design as a socio-technical system in which people co-create solutions within environmental boundaries. This exemplifies a shift from workstation ergonomics to strategic ergonomics, co-designing the entire organization, assessing loads and risks, and implementing circular economy principles in the spirit of Industry 5.0. (2—macroergonomics; co-design; ergonomic assessment; circular economy; Industry 5.0). (3) In the purple group, keywords focus on a company’s tangible impact on workers’ health, reducing occupational diseases and injuries, and evaluating whether organizational values genuinely protect people at work. (3—work occupational disease; occupational injury; CSR impact; values). (4) The red cluster integrates the continuous improvement of work systems with quality and business outcomes, aiming for organizational durability without compromising workers’ health, by mitigating the human costs of work, like musculoskeletal disorders. (4—lean production; organizational sustainability; musculoskeletal disorders; systems/work systems; quality; business sustainability; design; participatory ergonomics). (5) Keywords in the teal cluster present conceptual approaches to organizational governance—from developing coherent frameworks and measurable sustainability indicators to embedding them in operational decisions and strategic management. (5—integration; sustainability indicators; framework; management). (6) In the pink cluster, keywords suggest responsibility for the broader natural environment and include a discernible stream in the healthcare sector. (6—green ergonomics; ergology; environment; healthcare). (7) The green cluster presents a holistic approach, in which sustainable design and ergonomics methodology are means of coping with complexity and risk. (7—complexity; ethics; emergency; complex systems; systems ergonomics; ergonomic tools and methods; environmental sustainability; holistic). (8) The orange cluster links digitalization/automation with foundational pillars of workplace organization and likely represents a transitional stream—from an initial emphasis on digitalization toward a clearer articulation of the human role in these processes. (Industry 4.0; workplace organization pillar).

In the above overview, not all keyword clusters are characterized; only those judged most significant are discussed. Although the cluster characterizations partially overlap, they collectively indicate that the scope of ergonomics-for-sustainability extends beyond earlier framing trends that merely linked ergonomic action to sustainability, moving toward a broader, more system-level orientation (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

VOSViewer analysis of thematic links by keywords used by the authors of publications that were subjected to full-text research. The numbers 1–8 indicate the thematic areas described above.

An analysis of the full texts of identified bibliographic reviews and research publications allowed us to identify already defined directions of research undertaken within the analyzed research problem, indicating approaches to conceptualizing the combination of ergonomics and sustainable development, namely the following:

- Ergoecology;

- Green ergonomics;

- Environmental ergonomics;

- Immaterial (Intangible) ergonomics.

Ergoecology, first proposed by García-Acosta in his 1996/1997 master’s thesis in Spanish [10], is an attempt, frequently cited in the literature, to combine ergonomics, ecology, and the principles of sustainable development into a coherent theoretical framework. It aims to formulate solutions that strike a balance between human needs and environmental possibilities and limitations [31]. Ergology takes a holistic approach to studying humans in their work and living environments, focusing on analyzing human activity as a starting point for understanding the relationship between humans and their surroundings. It combines the perspectives of ergonomics, ecology, anthropology, psychology, sociology, work organization, and economics, and also takes into account the historical and cultural context in which the analyzed activity takes place. Unlike approaches that focus on selected aspects, ergology treats these elements in an integrated manner, emphasizing their interrelationships, the dynamics of change, and the need to adapt to new technological and environmental conditions. Ergoecology expands the scope of analysis in relation to traditional ergonomics, taking into account the broader environment of ergonomic systems with PESTE factors: political–legal, economic–financial, socio-cultural, technological–scientific and ecological–geographical, with particular emphasis on the latter, in order to design sustainable, effective, and environmentally friendly systems, products, and processes [32]. García-Acosta developed the concept by introducing three key principles of ergoecology: an anthropocentric approach, a systemic perspective, and a focus on sustainable development. The central tenets of this approach are also eco-efficiency and eco-productivity, which aim to maximize the positive contribution of human labor to the system while minimizing its negative impact on the environment [31]. The use of thermodynamic theories plays a key role in ergoecology, in which exergy (the useful energy necessary to maintain optimal system performance) is maximized, and anergy (waste energy) is minimized [10]. The close relationship between the ergoecological approach and green ergonomics is highlighted, as they share an interest in moral values within the context of ergonomics and human factors (E/HF). As Lange-Morales and colleagues note, both concepts contribute to the introduction of an ethical dimension into the design of technical and social systems [33]. What is important for distinguishing this approach in the context of human factors is that ergoecology introduces not only the ecological component as a prerequisite for sustainable development into the traditional triple bottom line (TBL) approach, but also other forms of capital—cultural, technological, and political—as integral parts of a systemic approach. It is therefore a clearly expanded approach compared to the classic TBL concept, which allows for a better understanding of the links between anthropogenic (tropic) and biothropic systems. Despite its undoubted conceptual advantages, ergoecology remains underdeveloped in methodological and empirical terms. There is still a lack of systematic research tools and practical implementations that would allow a transition from a theoretical framework to effective implementation in industry or service design, although attempts are being made in this area [34]. The scalable, systemic understanding of the relationship between humans and the environment that ergoecology postulates as part of the development of more responsible, sustainable, and morally justified ergonomic practices should be appreciated. However, despite attempts to separate the theoretical framework of this concept, its proximity to green ergonomics makes it a common trend in E/HF activities, specifically with the environmental dimension of sustainability [27].

Used interchangeably with ergoecology, the concept of green ergonomics was first used in 2008, but it was more widely adopted and strongly emphasized in the mid-2010s [35,36,37]. The most renowned researcher and developer of this trend, Andy Thatcher [38], pointed to a focus on pro-natural design and research activities that emphasize the two-way relationship between human systems and the natural environment. Green ergonomics has the same theoretical basis as the triple bottom line (TBL) but emphasizes pro-nature interventions in the field of human factors and ergonomics. Publications on green ergonomics include studies and characteristics of interventions or approaches that combine the analysis of human capabilities, needs, and activities with the need to protect, preserve, and restore natural systems [39]. Green ergonomics postulates that human health and efficiency are inextricably linked to the state of ecosystems. Therefore, its considerations include the design of systems, products, and workplaces in a manner conducive to the protection, conservation, and restoration of natural resources, as well as the use of ecosystem services to enhance human well-being and productivity. Green ergonomics emphasizes the need to develop low-resource solutions, design ‘green’ professions, support pro-environmental behavioral changes, and create work and living spaces that enable contact with nature and support human physical and mental regeneration [40], often drawing inspiration from biomimetics. Practical examples have already been linked to green ergonomics, such as reducing river and fish pollution [41], intuitive interfaces in solar vehicles [42], bamboo-made manufacturing objects [43], smart meters and thermostats [44], and roundabouts that reduce emissions and fuel consumption [45]. All these practical attempts share the use of human factors knowledge and ergonomic methods in achieving environmental goals. The disadvantage of this approach within green ergonomics is its lack of a specific methodology, which means it is often treated as a set of criteria combined with others to support managerial or design decisions [46]. Nevertheless, the undoubted appeal of this approach requires further work on systematizing the research problems, methods, and frameworks used, which will encourage the development of this concept in future publications.

Environmental ergonomics is an approach that has historically focused on analyzing working conditions—such as noise, lighting, microclimate, and air quality—and their impact on the health, comfort, and attitudes of employees [47]. Over time, this concept has come to be used to describe issues related to pro-environmental ergonomics (analogous to green ergonomics), including research on building design with user well-being in mind [48] or the inclusion of environmental costs in decision support models [49]. Nevertheless, analysis of this approach indicates that environmental ergonomics has not developed into a fully fledged alternative to newer trends, such as green ergonomics or ergoecology, which have more strongly emphasized their independence and the integration of ergonomics with environmental and systemic goals.

Immaterial ergonomics [50] is one of the latest attempts to broaden the traditional understanding of ergonomics to include the immaterial dimension of the workplace, encompassing knowledge, information, communication, cooperation, organizational culture, and social values. In this proposed approach, ergonomics is not limited to the optimization of workstations or technical processes but aims to design systems and interactions that enable effective information exchange, collaborative learning, and the development of social capital in sustainability organizations. According to the authors [50], immaterial ergonomics is intended to address the challenges of the knowledge-based economy and the trends of sustainable development, in which intangible values that support employee well-being and social responsibility are as important as the efficiency and safety of material systems. Complementing the concept of green ergonomics, which focuses on reducing the environmental impact of material products and systems, immaterial ergonomics emphasizes the importance of how knowledge is produced and used to create more conscious and sustainable models of organization and society. In this respect, this approach is similar to macroergonomics, which has the potential to support the development of anthropotechnical systems for sustainability purposes as well [51].

Considerations regarding economic trends supporting sustainable development indicate that some approaches—close to ergoecology or green ergonomics—are not directly defined but rather postulated as a legitimate combination of ergonomic and ecological requirements in the design of solutions, taking into account the evaluation of individual criteria, e.g., in designing for people with special needs while respecting environmental goals [52]. In addition, there are models focused on social sustainability, such as the Workplace Social Sustainability Model [53], which covers five groups of factors: employee well-being, safety, work comfort, musculoskeletal health, and environmental factors, i.e., sustainability considered only in social terms. At the same time, solutions are being developed that integrate ergonomics with ecology and decision-making processes in resource management, an example of which is the Green Ergonomics–RDM model [39], which combines ecological and human-centered principles with scenario analysis, stakeholder participation, and simulation modeling (authors have used ArcGIS and SWMM models), allowing systematic consideration of uncertainties related to climate change, population growth, and environmental degradation. Against the backdrop of these approaches, another interesting approach [29] combines the components of ergonomics—technical (E1): tools, machines, layout; environmental (E2): noise, microclimate, lighting; and organizational (E3): working time, task distribution, flexibility—with corresponding areas of sustainability: economic (S1): cost efficiency, productivity, waste reduction; environmental (S2): energy consumption, CO2 emissions, energy efficiency; and social (S3): health and safety, turnover, satisfaction, work–life balance, which is particularly interesting in view of the research problem addressed. Thus, truly ergonomic trends supporting sustainable development include both a social perspective and systemic approaches to balancing the relationship between people, organizations, and ecosystems.

4. Results of the Study—Achieving ESG Goals Through Ergonomics

An analysis of the evidence and indications regarding the usefulness of ergonomic measures in achieving specific ESG objectives and areas has enabled the compilation of a table of the most frequently cited sustainable measures in which ergonomics can play a key role. Table 4 lists only those that appeared at least twice among the items identified by a systematic literature review.

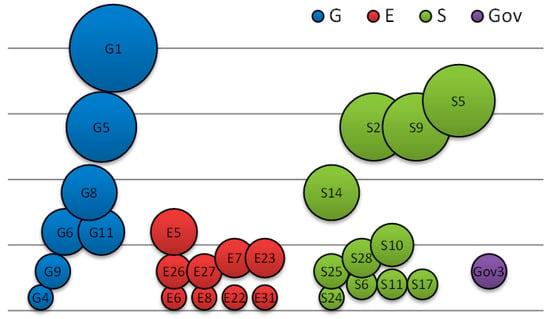

Figure 4 shows a visualization of the frequency of references to individual indicators and reporting areas supported by ergonomic activities, with the size of the circle and its position reflecting the number of mentions in the literature.

Figure 4.

Visualization of ESG areas supported by ergonomic activities.

In dimension G1 (Business model and ESG strategy), the possibility of integrating ergonomics with sustainable development manifests itself in many complementary activities. Firstly, ergonomics supports the development of a strategy based on sustainable development goals, incorporating an ethical and systemic perspective into the long-term priorities of the organization [54]. This is achieved through the implementation of “system of systems” models that combine micro-, meso-, and macro-ergonomics with the triple bottom line (TBL), while taking into account the management of human, social, environmental, and economic capital [55]. Incorporating ergonomics into strategic corporate governance guidelines improves the effectiveness and sustainability of activities. Tools such as EQUID 4.0 emphasize the role of organizational culture change, combining the quality of ergonomics with social and environmental dimensions [56]. In turn, the concepts of sustainable work systems and ergoecology suggest that employees are becoming a central element of ESG strategies, and ergonomics serves as a mechanism that combines economic, social, and environmental requirements [32]. In the long term, this approach enables not only the design of TBL-compliant work systems but also the redesign of entire business models to create sustainable value through a balance between productivity, employee well-being, and the protection of natural capital [10]. Ergonomics, extended to include green design aspects and intangible organizational resources (knowledge, collaboration, innovation), thus supports the development of a culture of social responsibility, strengthening the alignment of activities with ESG and global SDG goals.

In the area of ESG risk and opportunity management (G5), ergonomics acts as a systemic tool for identifying threats and extracting opportunities throughout the entire life cycle of the analyzed anthropotechnical system. It begins with designing for sustainable maintenance, i.e., shaping objects, products, or systems in such a way as to facilitate maintenance, reduce failures, energy losses, and environmental impact [57], taking into account all the roles humans will play in the system. It is postulated that the failure to take human factors into account generates unintended consequences and systemic risks [54]. Ergonomics introduces precautionary thinking and working with uncertainty (fuzzy/precautionary). In the PDD/EQUID 4.0 process, it combines technical, social, and environmental requirements to balance risks and exploit opportunities at the design decision stage [56]. It is crucial to integrate health and safety into the evaluation of risk for ESG and to use ergo-ecological indicators that enable the prediction of effects on human health and the environment, while also revealing opportunities to improve efficiency and innovation [32]. Work-related issues should be included in the register of risks and opportunities, and the risk of complex sociotechnical systems is addressed through resilience engineering and adaptation scenarios (e.g., RDM with stakeholder participation for climate risks) [39]. Work organization analysis (task distribution, pace, and goals) enables the combination of results with long-term well-being, and green ergonomics initiatives demonstrate how to simultaneously reduce WRMSDs and waste while strengthening employee engagement [58]. A crucial ergonomic measure here will be multilateral cooperation—HFE alignment among business, administration, and the environment—which enables the identification of risks and opportunities for sustainability related to the development of technical systems from the perspectives of various stakeholders [59].

In area G9 (ESG measurement and reporting methodology), ergonomics supports the development of consistent and reliable assessment tools that combine financial and non-financial dimensions [60]. The possibility of influencing the methodology for determining GRI indicators is highlighted, and so the methodology could be supplemented with psychosocial and ergonomic measures to more accurately reflect the realities of work and not overlook key aspects such as the psychosocial environment [58]. New methodological proposals, such as decent work analysis (SDW), through the assessment of environmental, ergonomic, and organizational conditions, demonstrate the need for further development of internal tools for assessing work quality (e.g., fuzzy logic, KPIs) and reporting their results within the ESRS and CSR [61]. At the same time, the literature highlights the lack of a comprehensive tool for assessing ergonomic risk, although fragmentary measurement methods are available. This, in the context of Industry 5.0, creates a need to implement digital solutions that integrate all aspects of risk and enable reporting in accordance with ESG requirements [62].

In areas G6 (Value chain—upstream and downstream impact) and G11 (Impact on stakeholders), ergonomics significantly supports ESG management by integrating a systemic approach focused on sustainability. This is because it covers the entire product manufacturing and logistics cycle, as well as the broader product life cycle [55], and shapes participatory relationships with stakeholders in line with the concept of ergonomic design. In the concept of a sustainable system of systems, ergonomics and occupational health and safety are taken into account throughout the value chain—from raw material extraction, through production, to use and disposal—which helps to reduce social, environmental, and health risks, even in countries with lower labor standards [60]. Models such as EQUID 4.0 and Ergo-Brand emphasize the role of active stakeholder participation (employees, customers, investors, regulators) in decision-making processes and identify ergonomics and decent working conditions as a source of competitive advantage [56,63]. Ergonomics is extending its influence to life cycle assessment and supply chain ergonomics, drawing attention to the risks of precariousness in developed countries and exploitation in developing countries. In this context, systemic tools are emerging, such as the Ergonomics Management Evaluation Model for Supply Chain [64], HFE audits in global supply chains, and the use of the triple bottom line (TBL) concept to balance social, environmental, and economic needs [65]. At the same time, ergonomics allows us to emphasize the role of employees as key stakeholders and promoters of sustainable development, as well as the importance of work as a fundamental dimension of social impact [66]. Transparent reporting on the role of HFE to employees, communities, regulators, and international organizations builds trust, supports dialogue, and allows the real impact of ESG to be revealed both upstream and downstream in the value chain.

In areas E5–E8 (total energy consumption, share of renewable energy, climate neutrality plans, climate change adaptation measures), ergonomics makes a significant contribution by combining technical, organizational, and behavioral aspects. Research identified in this area emphasizes that optimizing energy consumption in buildings and processes requires both the implementation of energy-efficient technologies (e.g., HVAC systems, smart lighting, energy management platforms) and the shaping of conscious user behavior [27,40,57]. Green ergonomics promotes the design of products, workstations, and systems that minimize the user’s carbon footprint while maintaining safety and usability [40]. Another important element is the promotion of renewable energy, including through ergonomic, human-friendly technologies (ergonomic conditions for photovoltaic panels, wind turbines) and ergonomic and eco-efficient solutions in transport (e.g., interfaces supporting solar vehicle drivers) [25]. The literature also highlights the need for systemic changes in line with the SDGs (7—clean energy, 12—responsible consumption, and 13—climate action), which involve integrating ergonomics into the design of low-carbon technologies and consumption patterns [32]. In the context of climate change adaptation, ergonomics supports the design of resilient communities, smart cities, and systems for responding to extreme weather events, combining a flexible approach to indoor comfort with urban planning and infrastructure [55]. Thus, ergonomics works simultaneously at the level of reducing emissions, transitioning to renewable energy sources, and preparing organizations and societies for the effects of climate change.

In areas E23 (Recycling and material recovery), E26 (Eco-innovation and Circular Economy), and E27 (Total Environmental Impact in the Product Life Cycle), ergonomics supports the implementation of the circular economy and a reduction in the economy’s overall environmental footprint through the integration of sustainable design, cradle-to-cradle, and ergoecology principles. In the field of recycling and recovery, ergonomics focuses on balancing resource cycles, designing products for reuse, and implementing ergonomic segregation and signaling systems that support appropriate user behavior. In the area of eco-innovation, the emphasis is on biomimetics and the use of innovative materials and design strategies that combine product usability with environmental requirements. This approach also includes practical initiatives, such as Green Ergo, which creates ergonomic solutions from waste that reduce waste production while improving working conditions. In turn, life cycle analysis (LCA) and the concepts of eco-efficiency and eco-productivity within ergoecology provide tools for assessing and reducing the overall environmental impact of products and processes—from design and production to the end stage. Green ergonomics promotes the development of eco-labels and user feedback (e.g., smart energy meters), which supports responsible consumer decisions. As a result, ergonomics not only enables a reduction in waste and raw material consumption, but also the creation of systemic innovations that support the circular economy, increase environmental resilience, and improve the eco-efficiency of organizations.

A crucial area of sustainability that will be affected by ergonomics is the social dimension of sustainability, which is mainly referred to in the following areas: S5—health and safety policy, S9—employee satisfaction, S2—accidents at work and occupational diseases, and, perhaps most interestingly from the point of view of current knowledge, the impact on local communities (S14). Sustainability in the social sphere is undoubtedly the most direct field of influence of ergonomics. To avoid tautology, it was decided that the findings in this area should, on the one hand, be of an organizational nature and, on the other hand, make decision-makers aware of the potential for sustainable development in these areas. However, no comprehensive analysis of the impact of ergonomics on social objectives was conducted, as this topic is addressed both practically and methodically [67,68].

Based on the literature, it can be concluded that the S5—Health and Safety Policy is an indisputably related area. Ergonomics plays a key role in shaping occupational health and safety systems, combining technical, organizational, and social perspectives [67,68]. The literature indicates that sustainable workplaces and systems must protect the health, safety, and comfort of users throughout the entire life cycle of these solutions [69] and that the future ethical approach to HFE requires the integration of health and safety principles with sustainable design [62]. Ergonomics supports health and safety policies by implementing micro- and macro-interventions that improve working conditions, reduce accidents, and engage employees and managers in prevention processes. Risk assessment tools are an important element of this, from classic methods (e.g., OWAS, SIDECE) to modern digital and IoT solutions that enable real-time monitoring of well-being and rapid response to hazards [67]. The literature recommends the introduction of more sophisticated methods for evaluating solutions based on ergonomic categories of social sustainability assessment [70]. The role of systematic assessment of environmental and ergonomic conditions (noise, lighting, heat stress, physical strain) is also emphasized in this dimension, as it allows for the identification of deficiencies in the area of decent work [70]. Ergonomics supports the rational implementation of technical solutions (e.g., manipulators, workstations designed with safety in mind), organizational solutions (micro-breaks, training) [68], and communication solutions (transparency of production processes, usability of information). In this dimension, ergonomics becomes the core of health and safety policy, as well as an element of social responsibility and a factor increasing the effectiveness of the organization [71].

In area S9—Employee satisfaction, ergonomics supports engagement and well-being through the design of work, spaces, and systems that promote health, motivation, and a sense of purpose in the work performed. The literature emphasizes that actively involving employees and users in design processes (e.g., when creating buildings or work systems) increases their satisfaction and productivity [72]. Ergonomic design criteria include not only the previously considered risks of musculoskeletal injuries [68], but also well-being and quality of life at work (QWL), which are the basis for engagement and positive employee–organization relationships [29]. Sustainable workplaces, in line with the concept of decent work and sustainable work systems, should support physical and mental health, personal development, recognition, and a sense of purpose at work, which strengthens the win–win relationship [27] between the organization and the employee. Ergonomic interventions—from microbreaks, workstation reorganization, and technical aids to participatory programs and biophilic solutions in offices—lead to increased motivation, better team communication, and continuous adaptation of the work environment [40,57]. Satisfaction indicators (e.g., eNPS, pulse surveys, QVT indicators) can be integrated into reporting systems to monitor well-being and engagement levels [73]. Ergonomics also supports competence development, incentive systems, and process transparency, which further build trust and employee identification with the organization [74]. As a result, employee satisfaction and well-being become not only a goal of sustainability in itself, but also the foundation of competitive advantage, which supports the implementation of sustainable development strategies.

In area S2—Accidents at work and occupational diseases, ergonomics contributes to the methodological aspect of measuring ergonomic risks [67], but also acts as a pillar of prevention, combining work design, health and safety policies, and risk measurement in a general sense [10]. The literature emphasizes that ergonomic work systems directly reduce injuries and occupational diseases, while increasing productivity and overall work quality [70]. Data from companies show that poorly designed tasks increase absenteeism due to MSDs, while ergonomic redesign of workstations reduces accidents and absenteeism [75,76]. In transport, the focus is on driver well-being, vehicle usability, and maintenance—health and safety procedures that reduce operational risk and support social responsibility. At the system level, ‘health and safety’, together with ‘work design and organization’, strengthen the sustainability of human resources, and the reduction in accidents and illnesses reduces costs and legal risks, strengthening the business case for sustainability. Assessment tools (REBA, ERA, OWAS) enable the objective identification of risk factors and their linkage to perceived discomfort [67], which guides preventive actions. ‘Green ergonomics’ in healthcare, in addition to reducing the risk of injury and increasing productivity, encourages reflection on environmental impact [34]. The link between ergonomics and sustainable development in the area of reducing accidents at work will also become more apparent with the development of Industry 5.0, which integrates ergonomics, human–machine collaboration, and advanced monitoring to reduce the number of undesirable events systematically. The redesigning of tasks also expands the possibility of safe work for people of different ages and abilities [77].

Ergonomics has a slightly different and less obvious impact in area S14—impact on local communities. The potential of ergonomics stems from its systemic approach to bringing together different stakeholder groups [78]. In this way, the interests of residents, employees, businesses, and the environment can be combined with those of diverse user groups [55]. HFE practices support the assessment and mitigation of complex impacts (e.g., conflicts over space, weather fluctuations, tourism pressure, or pollution), directing actions to build socio-effectiveness (no harm and improved quality of life) and eco-productivity (value without shifting costs to other systems) [79]. Reporting and management take into account not only the value chain, but also the social environment—hence ‘external’ CSR and responsible practices in the supply chain, such as Social LCA, as well as partnership initiatives such as Ergonomists Without Borders for communities with limited resources [38]. Ergonomics strengthens social capital through equal and open cooperation between stakeholders and the design of work and products with social impacts in mind, especially in primary sectors (agriculture, forestry, mining), where the goal is to protect people and ecosystems [31]. Activities also include local production of ergonomic solutions (e.g., outsourcing production to non-profit organizations), which creates jobs and perpetuates benefits in the community. In healthcare and spatial planning, green ergonomics and biophilic design integrate human systems with nature, enhancing well-being and productivity while caring for ecosystems [34]. In summary, incorporating HFE into community policies and projects not only improves workplaces but also enhances the social sustainability of local communities—from impact assessment and co-creation of solutions to measurable outcomes and mitigation strategies.

In the Gov3 dimension (Ethics and Compliance Policy), incorporating ergonomics/HFE into corporate governance means placing responsibility for work, health, and safety issues at the highest decision-making level [60]. Ergonomics becomes a tool for building compliance programs that counteract phenomena such as mobbing, support ethical practices, and incorporate ergonomic and ethical risk management into the organization’s daily operations [54]. In practice, this means implementing codes of conduct, establishing ergonomics committees, and creating an ergonomics ethics framework that promotes environmental responsibility and intergenerational equity. This expands the importance of ergonomics from the area of occupational safety to a broader ethical and social dimension, strengthening corporate governance and compliance with governance requirements. In practice, this cannot be achieved by appointing an ESG/HSE committee on the supervisory board with a member with BHP/HFE competencies; assigning an executive sponsor (e.g., COO/CHRO) on the management board for the ergonomics program; incorporating key indicators (accident and injury severity, ergonomic risk indicators, eNPS/well-being, supply chain audits) into the management board KPIs and remuneration policy; periodic reviews of HFE risks and opportunities in the risk register and integrated report (ESRS 1–2); a permanent employee participation channel (OHS committees, works councils) reporting to the management board/council; a competency and responsibility matrix (RACI) for ESG/HFE roles; and independent verification by internal or external audit [66,67]. This design ensures oversight, accountability, and measurability of decisions regarding green ergonomics throughout the business model.

According to the authors, those reporting areas that did not have a significant number of practical examples (relative to the others) are also worthy of attention. However, they mention activities that offer the potential to strengthen these areas of ESG reporting, including the following: Employees in the Value Chain (S2), Affected Communities (S3), Consumers and End Users (S4), Biodiversity and Ecosystems (E4), and Resources and the Circular Economy (E5). In these areas, ergonomics and compliance programs organize behavioral standards, counteract mobbing, and institutionalize accountability (codes, ethics committees), which directly strengthens the culture of compliance and decision-making transparency (GOV3). Ergonomic design reduces the risk of musculoskeletal injuries, stress, and turnover, improving well-being, safety, and equal access to work, which translates into complex indicators of employee and customer health and productivity (S4). Furthermore, ergonomic requirements embedded in purchasing specifications and supplier audits cascade health and safety standards and work ethics along the supply chain (S2). In the broader environment, ergonomic design impacts investments and their nuisances and risks to local communities (S3). Human-centered design improves user safety, accessibility, and readability of product and service interfaces, reducing accidents and complaints, and increasing customer trust (S4).

The literature on the subject has identified areas of sustainability reporting and activities that could be significantly supported by ergonomics. These include those where the behavioral aspect, related to changing human behavior, is crucial. Without an ergonomic approach that takes into account human behavior, habits, and limitations, implementing regimes that reduce an organization’s environmental impact will be much more difficult and somewhat mechanical. Here, we can expect impacts in the areas of reduced greenhouse gas emissions (E1), reduced GHG emission intensity (E4), and reduced emissions of nitrogen and sulfur oxides, particulate matter, and VOCs (E9). Similarly, in the area of implementing pollution control policies (E12), ergonomically designing procedures and systems that support employees increases the likelihood of their actual use. Changes in user behavior and habits can also influence total water consumption (E13) and improve the quality and reduce the volume of wastewater discharged (E16). In other words, ergonomics has the potential to become a key tool supporting pro-environmental transformation.

5. Sustainability Through Ergonomic Excellence Model (StEEM)

5.1. Green Ergonomic Practices—The Contribution of Ergonomics to Sustainability

An analysis of the collected literature allowed us to select ergonomic practices/approaches that particularly contribute to supporting sustainable development and achieving ESG goals, as well as the conditions under which these practices should be implemented. Bibliometric analysis also allowed us to determine the frequency of ergonomic practices supporting sustainable development, presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Highest number of proofs for ergonomic activity practices supporting sustainable development.

Based on the review, this study’s authors decided to adopt an original definition of green ergonomics practice for further consideration, which is the purposeful, evidence-based application of human factors knowledge to the design and improvement of systems, processes, products, and work environments to simultaneously (1) maximize the health, safety, and well-being of people and the efficiency of the entire system; (2) minimize—throughout the entire life cycle—resource and energy consumption, emissions, and waste; and, as a result, (3) strengthen the organization’s resilience. Green ergonomics practice is therefore a way to avoid shifting the costs of implementing business functions outside the organization (to the environment or external entities, especially with the increasing complexity of work relations [80]). Such practices include the following activities (based on [10,21,27,39,40,81,82,83]):

- Ergonomic audits—systematic reviews of workstations, processes, and organizational systems to adapt them to human psychophysical capabilities, while simultaneously identifying phenomena in the analyzed system that have a negative impact on the environment.

- Life-cycle assessments (LCA)—analysis of the impact of a product, process, or service on users and the environment throughout its entire lifecycle (i.e., all roles that humans will have to fulfill), enabling the identification of ergonomic solutions consistent with the principles of the circular economy.

- Green performance indicators (KPIs)—metrics tracking an organization’s ergonomic processes in terms of productivity, quality, employee safety, and health, as well as human activity with identified environmental impacts and ESG reporting.

- Ergonomic risk assessment—identification, analysis, and estimation of threats to human well-being (health, work-related discomforts), along with the assessment of scenarios (improvement proposals) for sustainable development (energy consumption and environmental impacts).

- Interdisciplinary partnerships for sustainability—creating a network of collaborations between science, business, and public institutions to implement ergonomics on a broad scale, particularly in areas that support social and environmental changes related to human behavior.

- Integrating ergonomics with innovation—utilizing ergonomics in the design of innovative products and services that support sustainable development goals and environmentally friendly technologies while simultaneously improving health and well-being at work.

- Organizational change management with an HFE perspective—incorporating ergonomics into organizational transformation processes, including ESG strategies and pro-environmental policies, to ensure sustainability and acceptance of change.

- Participatory design—engaging users and employees in the ergonomic design process to increase the fit and acceptability of solutions, while simultaneously reducing negative environmental impact.

- Macroergonomics—designing organizational structures and management processes to integrate employee health with social and environmental aspects, supporting sustainable development goals.

Less frequently mentioned in the literature, initiatives that have the potential to advance green ergonomic practices include:

- 10.

- Ergonomic education and training—developing competencies and awareness in ergonomics and sustainable development, both in formal education and within organizations, to foster a pro-environmental culture and human-centered organizations. This also includes the potential for creating competency models for sustainable ergonomics—frameworks defining the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary to perform tasks in a way that promotes employee well-being, as well as environmental and social goals.

- 11.

- Cost–Benefit analysis—an economic evaluation of ergonomic implementations, including their impacts on productivity, employee health, and environmental and social outcomes.

For the identified practices, links to the corresponding individual Sustainable Development Goals were identified. However, it should be emphasized that in many cases, the impact of these practices is multifaceted, making precise classification difficult, but due to the described procedure, feasible. Despite this complexity, an attempt was made to assign them to selected categories, as presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Map of connections between practices and individual ESG goals.

The presented systematic approach to practices supporting specific sustainable development goals does not exclude situations in which these practices may also be useful in achieving other areas and ESG goals. Furthermore, many of them undoubtedly effectively support areas not listed here, but the systematic literature review did not find sufficient evidence to confirm this clearly. This is certainly an interesting area for further research, as is other research that links ergonomics with the Sustainable Development Goals. An example of such an initiative is the company-wide Green Ergo campaign, which involved creating ergonomic solutions from waste materials sourced on-site. This concept reflected the essence of the “green” approach and mobilized engineers and employees across the company to design innovative, pro-ecological ergonomic solutions. The initiative led to the development of over 35 new solutions, reducing waste and solving more than 700 ergonomic problems—all at a fraction of the cost of new purchases [36].

5.2. The Concept of a Model Supporting Sustainable Development Through Ergonomics

One of the reasons why ergonomics is not yet considered a structured set of methods that can significantly support sustainable development is the lack of a methodological framework that would allow its use in both research and practice. Therefore, a conceptual, illustrative framework, Sustainability through Ergonomic Excellence Model (StEEM), is proposed below. This model combines elements of green ergonomics and ergoecology within a combined framework, while simultaneously presenting an approach understandable to decision-makers. To this end, the model’s elements are presented from two perspectives: areas of excellence (macro-action approach) and practices that companies can undertake to achieve specific dimensions of excellence (micro-action approach). The structured activities aimed at achieving sustainable development through ergonomics can be referred to as StEEM.

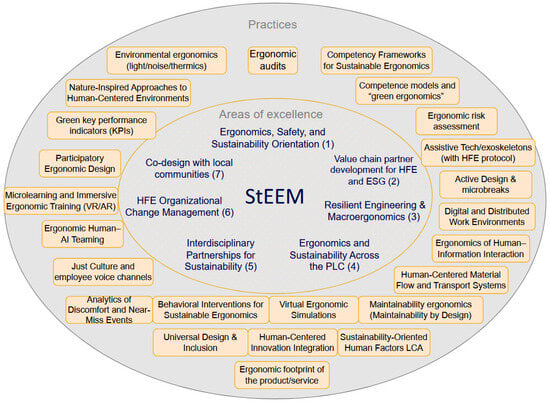

The StEEM framework (Figure 6) treats ergonomics as a kind of “nervous system” of an ESG strategy and organizes a range of practices into seven areas of excellence, which were inductively derived from a PRISMA-guided scoping review and Grounded Theory-informed coding that mapped concrete ergonomic interventions to specific ESG standards. The seven areas of excellence are not mutually exclusive, as some practices may partially span adjacent areas. For this reason, practices located near the boundaries of an area of excellence are not rigidly assigned to a single, graphically delimited action in the model’s visual representation. Accordingly, the areas of excellence are as follows: (1) a simultaneous focus on ergonomics, safety, and sustainability as the foundation of design and operational decisions; (2) developing suppliers in the spirit of HFE and ESG practices, enabling the transfer of responsibility standards up and down the value chain; (3) resilient engineering and a macroergonomic approach, aimed at systemically improving the sustainability and adaptability of the organization; (4) ergonomics and sustainability throughout the product life cycle, integrating perspectives on design, use, repair, and end-of-life; (5) interdisciplinary partnerships for sustainable development, connecting stakeholders and the environment; (6) organizational change management in HFE, enabling the consolidation of effects and building a culture that supports ESG; and (7) co-designing with local communities, enabling the inclusion of user and environmental perspectives in the process of developing pro-social and pro-environmental solutions. Literature analysis indicates that key green ergonomic practices supporting the implementation of ESG goals include ergonomic audits and risk assessments, green KPIs, LCA, and Maintainability by Design, participatory design, digital twins, and human–automation collaboration.

Figure 6.

Sustainability through Ergonomic Excellence Model (StEEM) concept.

At the same time, areas with significant potential, though requiring further research, can be identified, such as standardization of product “ergonomic footprints,” competency frameworks and green ergonomics certifications, biophilic and restorative work environments, VR/AR micro-training, information-cognitive ergonomics and explainable AI, inclusive universal design, as well as co-design with local communities and supplier development in the spirit of HFE×ESG. Although the model has an informational, conceptual character and these areas are presented as ‘areas of excellence’, it can also be understood as a practical roadmap. In other words, the model may guide organizations in planning and prioritizing concrete actions aimed at improving working conditions, strengthening sustainable orientation, and increasing organizational resilience. At the same time, these areas are promising research directions aimed at bringing proof about the real environmental and social benefits for companies from different branches and regions taking this path.

5.3. Future Research Agenda

To further develop the Sustainability through Ergonomics approach and develop and validate StEEM, which delivers measurable ESG results, there is a need for a coherent research program. It should link three complementary strands: (1) clear taxonomies and robust metrics for “green” HFE, (2) well-designed, real-world intervention studies, and (3) governance mechanisms that enable scaling across value chains. The aim is to close the gap between ergonomic practice, reporting requirements, and the practical implementation of ESG goals- moving from declarations to evidence and from “good intentions” to verified indicators. Future work should prioritize precise measurement frameworks, intervention evaluation, and management tools that make effective solutions repeatable and scalable. Some of the research directions fulfilling this purpose are given below (divided into two categories: methodological and area:

(1) From a methodological standpoint, it is preferable to establish a shared framework for the evaluation of impact-assessment instruments, rather than for the studies themselves, whose designs may legitimately vary:

- Development of a taxonomy and metrics related to ergonomics and its impact on organizational sustainability, and development of consistent, comparable KPIs for ESG performance. This series of actions would require the development of cross-industry benchmarks and ergonomic maturity models and thresholds for key components in line with ESRS.

- Development of scientific methodology to check how micro-ergonomic interventions comply with macro-environmental and social effects and build compelling proof-of-concepts for decision-makers. This requires the development of a methodology and a rigorous approach towards its observed results.

- Developing the StEEM framework and its triad: (1) measurement and standards; (2) design and interventions; (3) governance and scaling—as the overarching directions for integrating ergonomics with ESG.

(2) From the perspective of research potential, promising avenues could concern the following domains:

- Research on user-centered design as a means towards efficiency and reducing environmental impacts in processes.

- Developing strategies for the responsible implementation of Industry 5.0 solutions (AI/robotics/cobots) with a focus on human–automation interaction and ESG values.

- Developing the DfX directions supporting the circular economy (repairability, disassembly, serviceability) and the role of well-being, participation, and competences as “engines” of ESG outcomes.

- Research on ergonomics education and training that develops a pro-ecological culture and competency models for sustainable ergonomics in organizations and formal education. requires a coherent research program that defines robust green-HFE metrics, rigorously tests real-world interventions, and establishes governance to scale proven solutions across value chains.

- Cost–benefit analyses of ergonomic implementations in different economies, taking into account productivity, employee health, and environmental and social impacts.

The above summary presents only selected directions of possible research in the area of combining ergonomics with sustainable development, which shows its potential. According to authors, this field has considerable potential for expansion, especially since many companies are willing to connect their orientation to people (human-centeredness and care for the environment. The greatest challenge remains presenting replicable evidence of the effectiveness of individual approaches and a real connection between ergonomics and sustainable development goals, not only in the social aspect. Therefore, a research program should combine reliable methodology with a focus on useful artifacts (metrics, tools, standards) that can be transferred to business practices.

6. Discussion

The research conducted herein proves that ergonomics, understood as a discipline for designing and improving work systems, is a coherent mechanism through which to integrate environmental, social, and managerial objectives. Based on the literature, ergonomic interventions have been found to deliver benefits that extend beyond traditional occupational health and safety, encompassing resource efficiency, reducing waste and energy intensity, and the quality of decision-making processes. At the same time, evidence for the S domain predominates, while E and G remain less quantified in the literature. Therefore, ergonomics continues to be marginalized in the reporting of ESG, despite findings demonstrating its systemic nature and synergistic potential in complex sociotechnical systems. It should be noted that many authors have emphasized the usefulness of ergonomics as a tool in product design; ergonomic requirements, criteria, and standards appear in various stages of product or artifact development [84]. However, in the analysis presented in the paper, we synthesize the literature to demonstrate the usefulness of ergonomic methods and practices implemented at the enterprise level to achieve organizational sustainability and to achieve specific ESG objectives.