Abstract

This study provides a structured and differentiated review of the literature on platform labour from the workers’ perspective, examining how platform-mediated work affects multiple dimensions of workers’ employment conditions and well-being as well as their subjective experiences. Platform labour is a new form of work where companies create online platforms which match consumers with service providers, thereby providing workers with a new type of employment opportunity, casually referred to as “being your own boss”, accompanied by a certain degree of flexibility and autonomy. However, it is important to note that this flexibility and autonomy is limited by factors such as algorithmic management, and it has also led to the spread of increased precarity and social inequality. Existing studies highlight that these effects vary substantially across types of platforms, worker groups and socio-institutional contexts. The subjective experience of platform workers is neither an absolute “good” nor “bad” experience, but is a function of their own unique work and life experiences and personal needs. Based on these themes, we suggest that attention to the needs of different groups of platform workers, their diverse identities and interests, and to labour equity and social protection is key to the sustainable development of the platform economy. Future research could further prioritise cross-regional differences, algorithmic governance (including emerging technologies), the effectiveness of regulatory and organisational innovations in advancing labour equity and social protection, and the long-term, intersectional effects of platform labour, with a view to promoting a more inclusive and sustainable platform ecosystem.

1. Introduction

As digital technologies such as mobile internet, big data, cloud computing and artificial intelligence are becoming increasingly integrated, vast information networks now permeate every aspect of economies and cultures on an unprecedented scale [1]. The combination of these information technologies and an abundant workforce have led to the emergence of a new economic form—the platform economy—which is driven by big data, supported by digital platforms, and intertwined with the Internet. As an important branch of global capitalism, the platform economy has recreated business models, modes of collaboration and employment patterns, and it is known as “platform capitalism” [2,3]. Over the past decade, the rapid growth of the platform economy has restructured labour markets, changed the way work is organised and transformed traditional employment relationship standards and labour processes. Within this broader transformation, a new type of non-standard employment mediated by digital platforms has emerged, which will be referred to in this paper as “platform labour”. Recent estimates suggest that the number of active platforms has reached several hundred, spanning both developed and developing countries and engaging a large number of workers [4]. Platform labour, as a new type of labour system [5], is a form of work and employment in which workers provide specific services or solve specific problems through digital platforms in exchange for payment, with ride-sharing services such as Uber being a typical example.

Compared with a conventional labour system, platform labour is often portrayed as having a low entry threshold and offering a highly flexible way of working. Enabled by information and communication technologies (ICTs), platform labour appears to allow workers to choose and organise their own working hours and schedules [6,7], and has been widely regarded as an effective model for companies and workers to achieve flexible and autonomous employment [8]. Companies that provide and utilize such platforms, along with the mass media, have sketched a positive depiction of the platform labour as an inclusive employment model that offers additional income opportunities and greater autonomy for workers. However, this optimistic vision has been strongly contested when evaluated against social sustainability criteria. As part of what is often called the informal sector [9,10], platform labour may offer greater autonomy and flexibility, but at the cost of insecurity, low and volatile earnings, and limited access to social protection [11,12]. By classifying platform workers as independent contractors or micro-entrepreneurs, platforms can reduce their labour responsibilities and shift risks and uncertainties onto workers, leading to the temporisation and degradation of work [13,14,15,16,17]. Empirical assessments, including studies of platform labour in the Global South, show that many platform jobs fall short of decent work standards [18], leaving workers without effective safety and employment protections. Taken together, these critiques suggest that platform labour embodies a core tension in contemporary debates on sustainable work: while representing technological innovation and potential income opportunities, it simultaneously risks exacerbating social inequality and enabling new forms of labour exploitation.

Platform labour has attracted significant research interest due to its novel features and wide-reaching implications for work and employment. A rapidly growing body of studies has examined how platform labour influences workers’ income, working time and intensity, flexibility and autonomy, employment security, social protection and well-being in different countries and sectors. However, much of this research focuses on specific platforms, occupations or national contexts, using diverse concepts and indicators to capture the effects of platform-mediated work. Consequently, the available empirical evidence on the effects of platform labour is often fragmented and difficult to compare. Some studies emphasise the various economic and scheduling advantages for workers, while others document various forms of insecurity, work intensification and the degradation of labour standards. Much of this literature analyses individual dimensions of job quality without bringing them together into a more coherent picture. Furthermore, differences between types of platforms, groups of workers and socio-institutional contexts are usually examined separately, and workers’ personal experiences and evaluations tend to receive only limited attention in this literature. These limitations make it challenging to comprehensively assess how platform labour reshapes work for different groups and under what conditions it can be considered a “good” or “bad” form of work.

Against this background, this article aims to provide a structured and differentiated overview of the literature on platform labour from the workers’ perspective. We organise and summarise existing studies on the effects of platform-mediated work on various aspects of employment conditions and well-being (including income, working time and intensity, autonomy, security and social protection), and we pay particular attention to how these dimensions are linked to workers’ subjective experiences of platform work. More specifically, the review is guided by the following research questions: (1) How does platform labour improve or worsen employment conditions and well-being for workers, as described in the existing literature? (2) How do these effects differ across types of platforms, worker groups and socio-institutional contexts? How do workers subjectively experience and evaluate platform work? By addressing these questions, we bring together fragmented evidence on both objective working conditions and subjective experiences, providing a more nuanced understanding of the social effects of platform labour.

2. Defining Platform Labour: The Concept and Classification of Platform Labour

Platform labour, as the name implies, refers to work organized and mediated by digital platforms, where individuals perform short-term tasks or on-demand services in exchange for monetary remuneration [19,20]. In this an emerging form of work, a digital platform is an infrastructure or organization through which work is carried out. In essence, it is an intermediary that connects workers and employers, facilitating the matching of supply and demand for various services [21,22]. Unlike traditional employment, platform labour integrates information and communication technologies (ICTs) to structure work environments and utilizes algorithmic management to monitor worker behaviours, optimize task allocation, and control labour processes [23,24]. Workers engaged in platform labour typically operate as independent contractors, performing demand-driven tasks with clearly defined objectives. Their remuneration is task-based, determined by the nature and completion of specific assignments rather than traditional hourly wages [25,26]. This piece-rate payment system reflects the flexibility and project-oriented nature of platform labour while distinguishing it from standard employment relationships.

Due to the strong heterogeneity across different platforms and the wide range of job types, existing research often conflates related concepts such as digital labour [7,27], crowdsourcing/crowdwork [6,28] and gig work [29,30], making it difficult to clearly define the scope of platform labour. To clarify these overlaps, this paper adopts a specific definition of platform labour, emphasizing two core characteristics: (1) platform mediation, and (2) paid work. In this review, platform mediation means that the matching, allocation and/or payment of tasks is organised via a digital platform. Paid work indicates that workers receive direct monetary remuneration for their labour. This enables us to distinguish platform labour from broader forms of digital labour, including unpaid user-generated content and “playbour”, as well as from crowdsourcing and gig work arranged entirely outside of platform infrastructures. These two characteristics offer clear criteria for distinguishing the types of work considered in this review from broader forms of digital labour, including unpaid user-generated content and “playbour”, as well as from crowdsourcing and gig work arranged entirely outside platform infrastructures. Together, they enable us to define more precisely the types of work we refer to as ‘platform labour’ for the rest of the study.

Platform labour encompasses a variety of work arrangements and types of work, and its typological analysis can be conducted along key dimensions, including: (1) work modality: online versus offline labour; (2) geographic scope: local versus global labour markets; (3) skill specialization: simple, repetitive tasks versus skilled services [12,31,32]. We focus on labour platforms where the core of the transaction is workers’ time and labour effort. Within this scope, we concentrate on two primary categories: online crowdsourcing and on-demand work. We excluded “asset-sharing” platforms such as Airbnb, which primarily facilitate the temporary transfer of underutilised assets, with labour input being ancillary to this. Online crowdsourcing refers to remote, task-based work conducted globally, such as data tagging, data collection, or content moderation, with high worker autonomy and minimal platform interference [33,34]. Platforms like Upwork, Freelancer, and Amazon Mechanical Turk are illustrative examples of online crowdsourcing platforms. In contrast, on-demand work entails localized, real-time services—such as ride-hailing, domestic cleaning or food delivery—organised via app-based platforms that exert significant control over worker behaviours to standardize services [35]. Examples of on-demand work platforms include Uber, TaskRabbit, and Foodora. These cases are provided as examples to illustrate the two main categories, and do not limit the scope of the platforms included in this review.

3. Method

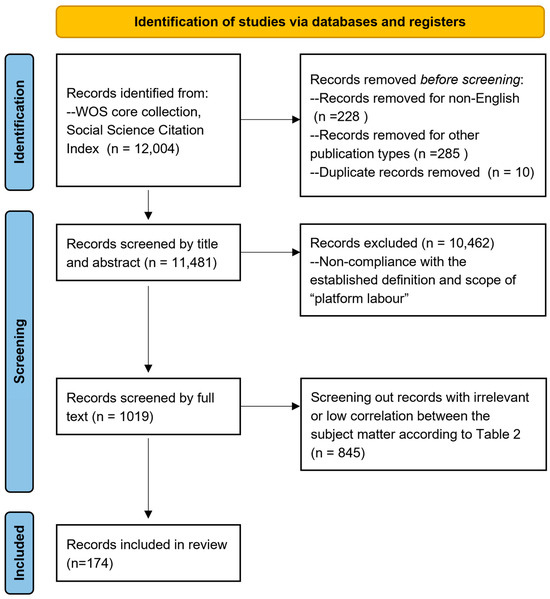

After clarifying the conceptualization and classification of platform labour, this study seeks to comprehensively and systematically uncover the effects of platform labour on workers by summarizing and reviewing existing research findings on the topic. To achieve this, the study adopted the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework, an evidence-based and structured guideline designed to assist researchers in conducting and reporting high-quality systematic reviews [36]. The PRISMA framework provided guidance for literature search, identification, screening, and inclusion processes.

This study selected documents from the Web of Science Core Collection as the data source due to its reputation as a high-quality and comprehensive digital literature resource, ensuring the reliability and completeness of this review. Given the study’s focus on the impact of platform labour on workers, a topic situated within the field of social sciences, the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) was identified as the most relevant database within the collection. A preliminary search was conducted using the topic search (TS) function in Web of Science with specific keywords, including “platform labour” and other related terms, such as “platform work” “labour platform” “gig work” “digital labour” “crowdwork” “on-demand work”. To ensure search precision, the time range was limited to publications from 1 January 2015 to 1 April 2024. A total of 12,004 records were retrieved by this method. Additionally, we used the Web of Science’s filtering functions to restrict the results to records written in English, with the document types set to “Article” and “Review article”. For the detailed searching criteria applied in this study, please refer to Table 1. A total of 11,491 records were retrieved from the preliminary search.

Table 1.

Summary of data source and selection.

The literature acquired through keyword searches may include records that appear relevant but are in fact unrelated to the research topic. To ensure that the studies selected for analysis accurately reflect the effects of platform labour on workers, a manual screening process was conducted to refine the initial pool of 11,491 records and determine the final set of eligible documents. After eliminating 10 duplicate records, the research team developed inclusion criteria (see Table 2) to guide the screening process. In the first stage, we removed records that did not correspond to our definition and scope of ‘platform labour’ by reading titles and abstracts. For example, we excluded studies dealing with general digitalisation or the ‘sharing economy’ that did not analyse platform-mediated work, as well as studies focusing only on consumers or platform companies. This resulted in 1019 records. We then conducted full-text screening to identify studies that examined the effects of platform labour on workers. At this stage, we excluded documents that did not substantially address the working or living conditions of workers, labour relations, or workers’ rights. For example, we excluded studies that described platform business models or technical features without a labour perspective, and studies in which platform labour appeared only as background context rather than the main focus of the analysis. Ultimately, 174 eligible papers were finally obtained for in-depth analysis. The entire screening process is depicted in the PRISMA flow diagram (see Figure 1). All included studies were published between 2015 and 2024, with a marked increase observed after 2017, reflecting the growing scholarly attention to platform labour. The studies draw on a diverse range of national and regional contexts, including European and North American countries, China and other Asian settings, as well as Australia. In addition, a smaller number of studies investigate platform labour in the Global South, for example in parts of Africa and Latin America.

Table 2.

Inclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for this study.

4. Dual Presentation of the Effects of Platform Labour on Workers: A Thematic Categorisation

4.1. Labour Utopia: Employment Opportunities, Flexible Autonomy and “Be Your Own Boss”

This subsection summarises a strand of the literature that emphasises the positive effects of platform labour on workers. It presents a “labour utopia” narrative by bringing together studies that highlight new employment opportunities, flexible and autonomous work arrangements, and the various forms of psychological fulfilment experienced by workers.

4.1.1. New Employment Opportunities

According to the International Labour Organization’s report, the number of digital labour platforms has grown fivefold over the past decade, while the number of mobility and delivery platforms has increased tenfold. Although it is difficult to accurately number the labourers making up the platform workforce, what is certain is that the rapid development of online labour platforms has created many employment opportunities for potential workers. Especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, labour platforms emerged as an economic lifeline for those with financial struggle. Digital labour platforms, which connect workers with customers through apps or websites, experienced significant expansion during this period [4]. For some workers, “side hustles” conducted through platforms have become their primary social safety net [37], even a financially risky strategy for surviving a crisis [38].

The low entry requirements for platform labour break down traditional barriers to labour force entry, thereby acting as a “social equalizer” [39]. For the unemployed and underemployed, platform labour provides alternative employment opportunities [40,41,42], and there is evidence that digital work through platforms appears to increase dramatically when a country’s unemployment rate rises [43]. For workers with short-term financial needs, platform labour offers them a “way to make money online” [44]. For many people who already have formal jobs or other income-generating activities, platform jobs including ride-sharing, delivery and errand-running have become a new source of incremental income [45]. Digital labour platforms offer new opportunities for people to pursue secondary occupations, and more and more people are engaging in platform labour to supplement their primary income [46,47]. Even professionals, including lawyers and independent scientists, are attracted to join [48,49]. For disadvantaged groups that might otherwise be excluded from the traditional labour market and the standard employment relation, such as women, the elderly, the disabled, and other marginalised groups, platform labour offers new employment opportunities that transcend structural barriers such as age, gender, class and ethnicity, allowing this group to overcome structural unemployment and remain active in the labour market [27,50,51].

Meanwhile, platform labour, in particular crowdsourcing, breaks down the geographical restrictions of the labour market to a certain extent and reorganizes of the workspace, allowing some workers to transcend the local labour market and work on a global scale [52,53], which has been shown to bring important economic opportunities to workers in some developing countries and regions. In regions with low income and high unemployment, gig work provided through platforms is often seen as a valuable alternative to traditional forms of employment, especially informal work. From the workers’ perspective, it represents an idealized form of new formal sector jobs [54], and functions as an “alternative safety net” by allowing workers to quickly generate income when other earnings sources decline [55].

4.1.2. Flexible and Autonomous Work Experience

Online labour platforms were initially developed to utilize idle labour resources effectively. Using big data-driven algorithm technology, these platforms accomplish this through the rapid and precise matching of customers with suppliers. This efficient value creation provides platform workers greater opportunities for flexible and autonomous work [13]. For example, Uber promises drivers that “With Uber, you have total control. Work where you want, when you want, and set your own schedule” and “Freedom pays weekly” [24] (p. 3761). Within this system, workers gain access to customer demand information, allowing them to independently search for job opportunities and decide whether to bid for these tasks based on the posted requirements [28]. This sense of empowerment is often presented as a key advantage of platform labour and is a primary reason for its appeal to prospective workers. Platform participants place a high value on the flexibility and autonomy provided by this model [34,55,56].

Some studies highlight that the central role of digital technology has provided workers with greater flexibility and freedom [57]. In contrast to the strict discipline and high-intensity demands of traditional factory work, online labour platforms do not impose mandatory on-duty times, allowing workers to choose when and where to work, decide what tasks to undertake, and organize their work according to their preferences. This setup provides full control over their working hours, locations, and methods [6,58]. The flexibility and autonomy provided by platform labour are primarily manifested in the temporal and spatial dimensions, focusing on when and where tasks are performed [13]. In terms of time, platform labour offers workers significant autonomy over their schedules. Unlike traditional work, where the “tyranny of the clock” dictates the pace, platform workers can independently decide when to work, how much to work, and how to allocate time between different tasks [59,60]. This level of control over working hours is considered a central innovation of platform labour [5]. Without fixed schedules, workers are able to adjust their working hours based on personal circumstances, freely choosing when to log in and provide services, or exit at any time [61,62]. This flexibility further enhances their autonomy and control over their work arrangements. When it comes to space, platform labour grants workers greater discretion over where they work, a feature particularly evident in online crowdsourcing. Freed from the constraints of traditional office environments, crowdsourcing workers can perform tasks from any location that suits them. For many, the ability to work from home is a key motivation for engaging in crowdsourcing [44], as it eliminates the burden of long commutes and significantly enhances their overall labour experience.

In sum, existing studies show that platform labour liberates workers from traditional work environments, enabling them to work independently and flexibly, and granting them greater control over their work arrangements [63]. The flexibility in work schedules and workplaces allows workers to tailor their jobs to meet individual needs, facilitating a balance between platform work and other commitments, such as family responsibilities, education, or leisure activities [7,40,44,59]. This flexibility, particularly in the timing and location of work, is considered one of the core innovations of platform labour, offering workers greater autonomy in managing their work–life balance and achieving personal goals [64]. Furthermore, platform labour’s inherent flexibility and autonomy have been shown to enhance job satisfaction and overall well-being. Studies indicate that gig workers report higher levels of job satisfaction compared to traditional employees, with flexible work arrangements and the ability to freely decide working hours and locations identified as key drivers of this positive outcome [58,65]. These features make platform labour particularly attractive to diverse groups, including those seeking flexible employment or balancing work with caregiving responsibilities.

4.1.3. Psychological Fulfilment

At a time when the Internet and its possibilities were just entering the popular imagination, Digital Nomad was simply a futuristic depiction of how new technologies might revolutionize our lives. The authors envisioned a lifestyle movement by inverting work and leisure, where employees can be scattered around the world and work when they want [66]. The emergence of the platform economy is making this “digital nomadism” a reality. A utopian discourse suggests that the platform economy is offering new possibilities for making money, while platform labour offers new freedom of micro-enterprise without bosses and strict work schedules [67]. Platform companies, represented by Uber, claim that they offer workers the opportunity to start a business and be their own boss. It is a promise that workers have full control over their work, giving them considerable autonomy. Finally, the relationship between platform companies and workers is open, thereby allowing workers to work for multiple platforms at the same time, including rival platforms. Thus, the features of freedom, flexibility and entrepreneurship are realized through digital platforms [24]. In mainstream hegemonic discourse, entrepreneurship has always been considered a superior and more liberating choice than direct employment [68]. This promise of “being your own boss” offered by platform labour is extremely tempting for workers who want to escape the tyranny of 9 to 5 traditional worksites, authoritarian bosses, limited wages and limited opportunities [69]. It has been found that workers highly value this opportunity to “be your own boss” [5,61,67,70], which allows workers to be free from the control and supervision of traditional work, and realize self-management and independent work. Entrepreneurial ideals of self-reliance and flexibility are widely spread among platform labour participants [71].

Workers also perceive a sense of meaning and psychological fulfilment from platform-mediated work. While platform labour is objectively considered low-quality work, some workers find personal significance in these jobs [72]. Many participants highlight the enjoyment from their work, such as keeping fit in courier roles and the opportunities of social interaction it provides. For some, especially those supplementing their income through temporary jobs, platform labour transcends traditional employment, often perceived as a “paid hobby” or even a “game” [65,73]. For some workers, particularly women in food delivery, platform work offers emotional rewards and a sense of fulfilment from assisting customers unable to shop due to age, illness, or disability. This satisfaction is linked to the meaningfulness of care labour. Additionally, platform work allows women to generate income from crafts such as shopping and cooking skills that developed through unpaid housework—a neoliberal reinterpretation of wages for housework [64].

4.2. Labour Dystopia: Spreading Precarity, Fictitious Freedom and Widening Inequality

In contrast, this subsection brings together research that highlights the negative aspects of platform labour. It presents a “labour dystopia” narrative by synthesising studies that point to the spread of precarity, intensified algorithmic control and the reproduction or deepening of social inequalities.

4.2.1. The Spread of Precarity

While platform labour promises unprecedented flexibility, this “flexible” employment arrangement imposes significant costs on workers. Flexibility is often seen as a key advantage of platform labour. However, it has also been used as a business strategy to encourage informal employment and establish non-standard work arrangements outside traditional organizational structures [74]. Since the 1970s, neoliberal policies have driven “institutional innovations” such as labour outsourcing and flexible employment, leading to the growth of informal employment forms, including part-time work, temporary jobs, and freelancing [75]. These trends have contributed to the global spread of precarious work, with wide-ranging social and economic consequences. The emergence of platform labour as a new employment model has further expanded the scope and severity of precarious work. Several studies show that, by turning labour to an extreme commodity, the platform labour tends to heightened precarity to unprecedented levels.

In the platform economy, workers no longer maintain stable, long-term relationships with a single employer. Instead, they complete tasks as flexible, independent individuals [25], reflecting a shift from traditionally secure full-time jobs to casual and temporary work arrangements. This transformation signals a fundamental change in the employment relationship, with the standard employment model being replaced by “pan-employment” and “de-labour” structures. Digital platforms actively designate workers as independent contractors rather than employees through their terms of service (ToS) agreements [20,76,77,78]. In many countries, this classification effectively undermines standard employment relationships and reduces employers’ responsibilities and obligations [25,79]. As a result, platform workers are usually excluded from social security systems and welfare benefits originally designed to protect formal employees [80]. They lack access to essential protections such as minimum wage guarantees, paid leave, health insurance, pensions, and work-related compensation for illness or injury. Additionally, they are denied collective bargaining rights and opportunities for career development, such as training and promotion [81,82,83,84,85,86,87]. The lack of labour protection exacerbates the vulnerable status of platform workers and increases the risk of precarity in their employment. This leaves workers more exposed to economic uncertainty and further entrenches the precariousness that characterizes platform labour.

In addition, the working conditions of platform labour appear to be deteriorating. Platform companies describe themselves as neutral technology platforms, enabling them to externalize responsibilities and risks that they would otherwise bear [88,89]. As a result, market risks and uncertainties are shifted onto platform workers [15,55,90,91]. This has resulted in the radical responsibilisation of the workforce [92], with platform workers shouldering a range of risks and costs associated with their jobs, including financial instability, physical harm, and cognitive stress [93,94]. Given that most platform work operates on an “on-demand” basis, workers often face unpredictable schedules, leading to alternating periods of “overwork” and “underwork,” accompanied by significant income fluctuations. Platforms rely on algorithms that operate on asymmetrical information to manage the workforce, forcing workers to rely on the technology they understand minimally. This results in unpredictable task allocations and pay structures linked to algorithmic decisions, further exacerbating workers’ economic risks [95]. Beyond financial risks, platform labour also exposes workers to physical and mental health challenges [96]. For instance, tasks such as food delivery or transportation often involve heightened risks of injury [97,98,99], and expose workers to bodily and emotional threats, including sexual harassment and threats of violence from strangers [93]. Unpredictable demand and pay rates, uncertain work frequency, and irregular working hours for platform labour all expose workers to uncertainty about their employment and expected earnings, and further contribute to anxiety and psychosocially burdening [100,101]. While platform labour is often praised for its high levels of autonomy and flexibility, it also forces workers to navigate the drawbacks of lacking structural organizational support [102]. The structural and technological design of the platform fosters a sense of isolation and social segregation, which exacerbates the precariousness and vulnerability of workers [54]. Career path uncertainty has been identified as a significant challenge faced by platform workers, who often struggle to plan long-term professional trajectories [103]. Moreover, external labour market uncertainties increase the risk of unemployment for platform workers, with some losing their income sources during economic recessions, shifts in consumer expectations, or periods of illness or injury [104].

The precarities associated with platform labour—including a lack of labour protections, unpredictable demand, income volatility, and health risks—have prevented many workers from building financial buffers against labour market adversities like the COVID-19 pandemic-induced economic crisis [38]. These challenges have significantly impacted workers’ overall well-being [105]. Fortunately, a survey by Schor et al. (2019) found that not all platform workers are experiencing this precariousness at the same time, as many of them merely utilize platforms for supplementary income, which is utilized to reduce precarity, pay off debt, or build savings [5]. However, this does not negate the fact that platform labour overall is frequently causing increased job insecurity. With the continuous expansion of the platform economy, platform labour appears to be fostering a new precariat which works in unsafe jobs with few employment benefits or social protections.

4.2.2. Algorithmic Management and Fictitious Freedom

As mentioned earlier, flexibility and autonomy are frequently promoted as key attractions for workers joining platforms. While there are undoubtedly certain individuals with specialized skills who work on digital platforms and enjoy these benefits, most platform workers face a very different reality [76]. The autonomy and flexibility promised to workers are at odds with how platforms market themselves to customers—offering 24/7 access to inexpensive labour, readily available at short notice [106]. To stabilize their capacity to meet consumer demand, platform companies have adopted a new form of management—algorithmic management—that ensures workers remain perpetually “on-demand” for customers [107]. Vallas and Schor (2020) aptly describe this phenomenon as “the digital cage,” highlighting how algorithmic management shapes and restricts the working conditions of platform labourers [89].

As the operational core of digital platforms, algorithms powered by big data perform roles traditionally associated with human managers, overseeing platform workers distributed across time and space with minimal human intervention [24,108]. Algorithmic management oversees the entire platform labour process, coordinating and matching labour supply with task demands, optimising workflows, providing informational support to workers, monitoring and supervising performance, and handling dispute resolution [13,109,110,111]. At the same time, these algorithms supervise and control workers’ behaviours and performance in real time through ratings and digital reputation systems [7,62,112,113]. To ensure platform efficiency, algorithms continuously collect and analyse ecosystem data, creating a dynamic database to inform platform decision-making. However, these algorithms lack transparency, with data selectively presented to workers, resulting in significant information asymmetry. For instance, workers often lack critical details about how platforms assign tasks, evaluate performance, or determine compensation [24,114,115]. The lack of access to critical information places workers at a disadvantage, leaving them with little to no bargaining power [82,116,117]. The asymmetry creates a significant power imbalance, leaving workers unilaterally dependent on platforms for critical information and technical support [13,14,118]. Such dependence erodes their capacity to exercise control over their work and agency, particularly in managing job arrangements [35,119]. Workers are subject to the “tyranny of the algorithm” [59], reflecting the restrictive and oppressive mechanisms of algorithmic management. Despite platforms’ promises of flexibility, workers find themselves operating within a system that restricts their autonomy.

Empirical evidence reveals that platform workers face substantial constraints on their autonomy in both task selection and scheduling. Algorithmic management exerts tight control over job opportunities through scheduling algorithms that determine task assignment mechanisms [112]. Although workers retain the option to reject assigned tasks, frequent rejections negatively impact their future task allocations, effectively undermining their ability to exercise genuine choice [13,120]. Moreover, reputation systems based on customer feedback are used as assessment tools to continuously drive workers’ self-optimisation [18]. Task assignments are closely linked to platform workers’ ratings and reputations, with those having higher ratings and reputations generally more likely to secure work opportunities [7,30,121]. Conversely, workers with lower ratings may lose eligibility for bonuses or even face account deactivation, preventing them from continuing to work on the platform [120,122]. Faced with this subjective and inconsistent evaluation method, workers rarely have the opportunity to dispute penalties or pay issues [123], which may generate uncertainty for workers [94,124,125]. As online labour markets operate around the clock, platform workers often engage in non-standard working hours, including evenings, nights and weekends, to meet customer demands [126]. Despite claims of temporal flexibility, platform workers’ autonomy is essentially restricted to platform login/out decisions [119], with prolonged offline periods risking account deactivation. Due to the discontinuous nature of tasks, platform workers must spend substantial time waiting for and searching for new tasks [77]. This results in increased exposure to work-related communications outside standard working hours. To avoid missing algorithmically updated work opportunities, workers are forced to remain connected around the clock [84] and work intensively during irregular and unusual hours [7]. While they technically have the freedom to choose their working hours, the platform’s algorithmic management of schedules promotes an “always-on” work culture, making workers prioritise work availability over personal life, thus intensifying work–life conflicts [127,128]. To respond to the dynamic fluctuations in platform labour demand, platforms employ algorithms to dynamically monitor and adjust labour supply. Gamified mechanisms, such as performance-based competition and rewards, as well as dynamic surge pricing, are used to incentivise workers to remain online during periods of high demand or under adverse conditions [30,112,123,129,130,131]. However, these strategies often come at the cost of workers’ personal flexibility. Furthermore, with the growing number of full-time workers in the platform economy, “de-flexibilization” has emerged, where sticky labour—workers trapped in platform work—are more likely to follow fixed schedules rather than flexible ones [132]. Intense competition among workers suppresses wage levels, forcing them to extend their working hours to secure sufficient income [133,134]. These conditions ultimately render the promised flexibility of platform labour illusory, as workers find themselves constrained by algorithmic management rather than empowered with genuine autonomy.

More importantly, algorithmic management profoundly impacts platform workers’ perceptions of autonomy, placing them in an autonomy paradox where control over their work becomes illusory [135,136]. While platform workers may appear to have some autonomy in choosing when and where to work, this perceived flexibility often translates into hidden forms of control and constraint. New modes of supervision centred on algorithmic governance diminish the promised flexibility, replacing it with “softer and less visible forms of workforce supervision and control” [119] (p. 2954). The gamified labour process reinforces this illusion of empowerment [30,35], encouraging workers to believe in the meritocratic ideals promoted by digital platforms like Uber—that hard work and perseverance lead to meaningful rewards [41,137]. Studies further highlight how the most efficient workers are incentivized and rewarded [138], perpetuating the belief that individual effort determines success. However, covert algorithmic governance weakens workers’ capacity to resist by immersing them in positive narratives about autonomy, which, in reality, mask their exploitation [139,140]. Unknowingly, platform workers participate in self-management, reinforcing their labour through constant engagement. This results in what Shibata terms “fictitious freedom” [141] (p. 535), where the freedom to work anytime becomes a compulsion to work anytime. The cycle of escalating work engagement traps workers in longer hours and greater commitment, as increased autonomy paradoxically equates to heightened control [84].

4.2.3. Replicating and Widening Inequalities

Platform labour has sparked concerns about replicating and amplifying existing inequalities. Although digital platforms often promise equal access and opportunities, platform labour does not necessarily result in broad participation or equitable opportunities. Equipment requirements and differential access to digital infrastructure are fundamental barriers to online participation. Individuals who are wealthier and have more resources, or those with higher levels of education and superior internet skills, are more likely to participate in online work. Inequalities in digital participation have exacerbated stratification in the labour market and increased labour inequalities [142,143]. Moreover, individuals with existing advantages in the labour market are the primary beneficiaries. Skilled workers with greater social capital can leverage their expertise to create voluntary and desirable work arrangements [29,144]. Similarly, highly educated individuals are more likely to secure work on platforms [145], with many already holding formal full-time jobs and treating platform labour primarily as a source of supplementary income. These participants often perform tasks traditionally associated with blue- and pink-collar roles, such as cleaning, driving, and other manual work, effectively crowding out disadvantaged and less educated workers. The relatively privileged middle class is better positioned to exploit these technological innovations, expanding their opportunities and increasing their income, thereby exacerbating income inequality among the bottom 80% of earners [146]. Consequently, several studies suggest, in the contexts they examine, the platform economy tends to disproportionately benefits the affluent and well-educated [45], while the less privileged and disadvantaged see few comparable gains [147].

Intelligent algorithmic systems used by platforms to identify and screen worker eligibility may inadvertently introduce bias and discrimination [77]. These issues arise from the programming of algorithms and the datasets they are trained on, which often reflect existing societal inequalities. When algorithms rely on biased data, they tend to “unintentionally encode gender, ethnic, and cultural biases” [148] (p. 15), and further contribute to inequality. Evidence from Tan et al. [149] highlights this issue, showing that women, ethnic minorities, and workers in low-income countries are particularly vulnerable to discrimination on digital platforms. As the European Institute for Gender Equality warns that sexism and discrimination in the labour market may be reinforced in platform labour [150]. Gender inequality is one of the most prominent issues in platform labour, and is a reproduction of long-standing forms of inequalities in the digital world of work [20,151]. Occupational gender segregation persists in platform labour, with women more likely to be assigned to low-skilled, repetitive tasks and excluded from higher-paying opportunities. They are predominantly concentrated in low-wage, female-dominated service sectors such as cleaning and caregiving [69,152]. This segregation reflects broader patterns of inequality in traditional labour markets, indicating that platform labour perpetuates and entrenches existing gender disparities. As platforms operate in a new, semi-unregulated environment, they expose women to higher levels of vulnerability and insecurity [153]. Women engaged in platform work often face greater economic insecurity and earn lower incomes compared to men [69]. For example, female Uber drivers in the United States earn approximately 7% less than their male counterparts, partly due to differences in driving speed and unpaid caregiving responsibilities [154]. Moreover, women encounter discrimination within reputation systems, particularly when performing gender-incongruent tasks such as driving. Female drivers frequently receive lower ratings from dissatisfied customers than male drivers, which adversely impacts their ability to secure future tasks or maintain earnings [155]. While flexibility and task dispersal are often cited as motivations for women to participate in platform labour, these features fail to address challenges related to balancing work and life. Instead, they further reinforce the part-time nature of female employment, which is expected to weaken women’s labour status and exacerbate existing inequalities [104,156]. Beyond gender-based inequality, racial discrimination has been identified as a significant issue within platform labour. Minority workers face additional instability at work, ranging from offline aggressive behaviour to online “hate” speech [157]. Consumer ratings often reflect pre-existing racial biases, and given the centrality of reputation systems in algorithmic management, such biases can severely impact workers’ opportunities, which include lower pay, restricted access to tasks, or even account deactivation [158]. Additionally, geographic disparities manifest in platform labour through limited access to opportunities, unequal pay, and other forms of inequality [27,50].

In addition, new dynamics of inequality are emerging on digital platforms: the “servant” economy [45] (p. 9) and reintermediation. Platform labour is fostering the creation and development of a “servant” economy, where consumers can access cheap labour at the click of a finger for services such as errands, deliveries, and dog walking. On-demand work is trending toward a world where low-income earners are sent to perform routine tasks for wealthier people, whether delivering a cup of coffee in a rainstorm or picking up groceries [45]. Additionally, reintermediation has emerged in platform work, where workers with higher reputation scores frequently subcontract tasks to those with lower ratings, exploiting the system where better ratings guarantee more work. This creates multiple layers of inequality within the platform workforce [27,85]. Similarly, licensed delivery workers, with platforms’ tacit approval, use social media and family/social ties to provide informal gig work opportunities to undocumented migrants [159]. These dynamics of platform labour exacerbate income and status inequalities for workers.

5. Not Absolutely Good or Bad: Examining Subjective Experiences of Workers

The effect of platform labour on workers appears to be both utopian and dystopian. While platform jobs are frequently accompanied by neoliberal rhetoric emphasizing freedom, flexibility, and individualized entrepreneurship, workers simultaneously experience relentless pressure and surveillance, shaped by customer ratings and the “algorithmic panopticon” [160] (p. 827). On the one hand, platform labour offers benefits such as employment opportunities, especially for disadvantaged groups, and grants a degree of flexibility and autonomy. On the other, workers confront pressing issues like excessive competition, worsening labour conditions, and inadequate protections. The dualities inherent in platform labour suggest that reducing its impact to a simplistic binary of “good” or “bad” fails to reflect its true complexity. Thus, it becomes essential not only to assess the effects of platform labour but also to explore how workers subjectively perceive and navigate these experiences. Thus, based on existing research, we adopt a heuristic analytical perspective to organise findings on heterogeneity across different labour groups and contexts. This allows us to explain the contradictory and sometimes conflicting results emerging from the literature. Furthermore, we examine how workers subjectively experience and evaluate platform labour in attempt to explain why individuals engaged in similar work may have markedly different opinions.

5.1. Heterogeneity of Platform Workers

One of the key aspects to consider is that platform labour encompasses a diverse and hard-to-define group of workers. While much of the existing literature tends to treat platform workers as a homogeneous entity, recent studies highlight workforce heterogeneity as one of the defining structural characteristics of platform labour [89]. Overlooking these differences risks oversimplifying the complex realities and varied impacts of platform work on different worker groups. In this section, we consolidate disparate evidence regarding heterogeneity and concentrate on three interrelated dimensions that frequently emerge in the literature: the specific type of platform labour, the worker’s socio-structural and geo-institutional context, and their level of economic reliance on platform income. The importance of distinguishing these dimensions lies in their capacity to systematically explain the sources of divergent conclusions found in the platform labour literature.

The concept of platform work encompasses many different types of professional activities, each embedding workers in distinct labour processes. Different sectors vary in terms of labour allocation, the degree of task standardisation and control structures. These differences lead to significant distinctions among workers in terms of occupational risk, precarity and autonomy. For example, online crowdsourcing (e.g., programming, data entry) generally offers greater spatial and temporal flexibility, enabling workers to determine when and where to log in and to select from a diverse range of tasks [7,54,56]. In contrast, on-demand services (e.g., ride-hailing, food delivery) provide only partial flexibility in scheduling, as work hours are tightly constrained by real-time demand and platform requirements [119,129,130]. In these settings, workers are subject to dense forms of algorithmic management, including real-time matching, location tracking and performance monitoring, which narrows their effective autonomy [112].

Furthermore, the worker’s social position and the geo-institutional context significantly shape how platform labour impacts workers. These structural and contextual factors influence how individuals perceive, experience, and adapt to platform work. On a global scale, disparities in labour protection and workers’ rights create varying perceptions of precarity among platform workers. In Euro-American contexts, the rise of platform labour is often framed as a driver of a new “precariat”, marked by a shift from previously secure, regulated employment to more precarious, unprotected forms. The scholarly debate often centres on the erosion of labour rights, the increase in self-employment, and the spread of algorithmic management, which intensifies insecurity and shifts risks onto workers. Meanwhile, in many Global South countries where statutory labour protections have historically been limited or absent, large segments of the workforce have long endured precarious and unprotected working conditions [161]. In this situation, platform labour is often welcomed as a source of income, and is sometimes considered an improvement on existing informal work. However, it still perpetuates insecurity, low pay and a lack of social protection [54,162].

Research on Uber drivers illustrates how the digital ecosystem generates general feelings of insecurity and instability among workers, while different subgroups of drivers experience precariousness in distinct ways [41]. For part-time drivers, Uber primarily serves as a flexible source of supplementary income, allowing them to adjust hours and log off at will, whereas full-time non-professional drivers often treat it as one of their few viable employment options and endure long, irregular hours dictated by demand; full-time professional drivers may join Uber for greater flexibility and lower operating costs than traditional taxi companies, yet oversupply and intense competition frequently undermine their earnings. Schor et al. explained this phenomenon with the term platform dependence, describing the extent to which workers rely on platform income for their livelihoods [5]. Platform dependence offers a useful lens for understanding why some workers view platform labour positively while others express dissatisfaction [45]. It also helps to explain why some studies emphasise the opportunities and autonomy associated with platform work, while others highlight insecurity, long working hours and loss of control, even when they examine similar types of platforms. The degree of autonomy and job stability experienced by platform workers is largely contingent upon their economic reliance on platform income. For supplemental earners, platform work serves as a secondary income source, allowing them to exercise greater autonomy. They can flexibly adjust their schedules, prioritize higher-paying tasks, and log off during periods of low demand, poor traffic conditions, or adverse weather [5,59]. In contrast, dependent earners, whose livelihoods are primarily or entirely tied to platform income, face significantly less flexibility and heightened instability due to fluctuating platform policies and declining wage rates [5,59,163].

This economic dependence is shaped by a complex interplay of factors, including age, race, gender, social capital, and skill levels, all of which are embedded in broader labour market dynamics and socio-economic contexts. While platform labour undeniably creates new income opportunities, it fails to distribute its benefits and risks equitably among workers, perpetuating structural inequalities. Those who are already disadvantaged in the labour market often find themselves grappling with greater precarity, while workers with higher social capital and resources are better positioned to leverage platform labour to their benefit. Disparities in risks and rewards are particularly pronounced between migrant and non-migrant platform workers [164]. With the growth of the platform economy, platforms use technology to rapidly access a worldwide reserve labour army, researchers have increasingly focused on the intersection of migrant labour and platform work [51,165,166,167,168]. Digital platforms undeniably offer relatively low barriers to entry for migrant workers, enabling them to secure income opportunities with minimal identity verification and qualification requirements [51]. However, these opportunities are often concentrated in low-skilled, low-paying, and physically demanding jobs such as delivery services, cleaning, and domestic work [169], exposing migrant workers to heightened risks of instability and exploitation.

5.2. Subjective Experience of Platform Workers

Given the internal differentiation among platform workers, it is crucial to adopt a worker-centred research approach that prioritizes their subjective experiences, as workers’ perspectives and experiences of platform labour are key to understanding this new form of work. Goods et al. highlight that, while food delivery jobs offer limited economic security by objective measures, workers are heavily constrained by algorithmic management, with little autonomy beyond deciding when and where to work [60]. Yet, some workers perceive platform labour as a source of substantial economic opportunity, valuing the autonomy it affords. Surveys of Uber and Lyft drivers reveal similar findings [70]. Many drivers describe their work as flexible, engaging, and even socially meaningful. However, alongside this perceived freedom, they also encounter varying degrees of insecurity and instability. Thus, platform labour presents workers with inherently contradictory experiences.

Platform workers’ diverse needs and preferences may help explain their contradictory attitudes toward platform labour. While certain characteristics of platform labour can be objectively categorized as either “good” or “bad”, workers tend to assess their experiences based on their unique circumstances and personal priorities. Studies have found that even platforms associated with “poor” work quality may still provide opportunities perceived as “good” by certain workers [140,169,170]. This paradox is not unique to platform labour. Despite the known deficiencies of their jobs, food delivery platform workers often rate the quality of their work highly. While food delivery job offers limited economic security and subject workers to strict algorithmic management, some workers subjectively perceive platform labour as a valuable economic opportunity. They view the autonomy provided by the job as a significant advantage [171]. For some, platform work is not viewed as a career but rather as a practical means to earn extra income, often with a clear exit strategy in mind [41,60]. Others approach platform work as a “profitable leisure activity”, drawn by its flexible schedules, opportunities for social interaction, or the sense of fulfilment it offers [58,65,70,169,172,173]. In either case, when platform labour aligns with workers’ individual needs, its perceived benefits can outweigh its drawbacks. Under such circumstances, workers often view platform labour positively, accepting its risks and instability as an inevitable trade-off for the flexibility and autonomy it provides. Under these circumstances, a consequence of algorithm-managed jobs is that work that is structurally considered “bad”—due to unstable (and often low) wages, minimal labour protections, and limited advancement opportunities—may not be perceived as quite so adverse psychologically [174].

Platform labour cannot be viewed in isolation from the broader labour market [175], it must be understood in relation to the structural conditions of the general employment landscape [146]. Embedded within this larger context, platform labour is influenced by the availability and quality of jobs in the wider labour market, which, in turn, shapes workers’ subjective experiences and perceptions [5]. When better employment alternatives are scarce, workers often express gratitude for platform labour, viewing it as a means of securing at least minimal income, relative autonomy, and some degree of satisfaction [41,44,60]. This became particularly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, when platform work served as a crucial fallback option for many workers amidst widespread economic disruptions and job losses. At an individual level, the effects of platform labour must be evaluated through a contextualised lens. While platform work may align with some workers’ personal circumstances, rendering it an acceptable choice for specific groups [60], this does not imply that workers inherently perceive it as a particularly desirable or fulfilling occupation. For many, platform work represents a temporary phase or supplementary activity, with few workers envisioning it as a long-term career prospect [41,172]. In an increasingly unstable economic environment, platform labour often emerges as a “better-than-nothing” option—a fragile safety net rather than a stable source of livelihood.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

As platform labour becomes more widespread, it is crucial to understand its impact on workers comprehensively. Through systematic literature review, this study successfully provides a comprehensive description of the emerging social phenomenon of platform labour, systematically identifying and discussing the multiple effects of this system on workers. We reveal a complex and contradictory dual reality (see Table 3): platform labour serves as both a labour utopia offering employment opportunities and flexible autonomy, and a labour dystopia that spreads instability, creates fictitious freedom, and widens inequality.

Table 3.

Summary of perspectives on the effects of platform labour on workers.

Amid these conditions, workers experience a “splintering precarity”, balancing between risks and rewards. This precarious state prompts workers to rationalise their feelings of insecurity and uncertainty, inadvertently facilitating corporate exploitation and the promotion of neoliberal privatisation [70] (p. 384). However, the effect of platform labour cannot be universally categorised as either entirely “good” or “bad”, as platform workers are heterogeneous along three interrelated dimensions: the specific type of platform labour in which they are engaged, their socio-structural and geo-institutional context, and their level of economic reliance on platform income. Workers positioned differently across these dimensions often evaluate similar forms of platform labour in very different ways. Focusing on the subjective experiences of platform workers reveals that platform labour entails a complex interplay of both positive and negative outcomes. Workers tend to assess the outcomes of platform labour based on their distinct work and life experiences and personal needs. They are drawn to the relative freedom and autonomy it offers, appreciating the ability to earn income flexibly and independently. Simultaneously, they face the insecurities and uncertainties inherent in platform labour.

These contradictions also depend on the perspective and level of analysis. From a macro-perspective, algorithmic management is perceived as a formidable engine for economic growth, enhancing the flexible autonomy of platform work. However, substantial evidence indicates that it can also become an exploitative mechanism that unfairly monitors, rewards, and punishes workers. What is often celebrated as work flexibility can, in reality, translate into instability. Consequently, platform labour can be perceived in starkly contrasting ways: it may be viewed as a utopian innovation that liberates workers or as a dystopian exploitation, largely depending on one’s view of digital participants—whether they are seen as empowered creators or merely as tools of capital [176]. Furthermore, to accurately assess the effect of platform labour, it is essential to consider broader labour market conditions. When job instability and insecurity are prevalent, and temporary contracts, poor working conditions, low wages, overwork, and lack of social protection are widespread, platform labour often becomes a more appealing option, at least offering workers some autonomy and income. This phenomenon was evident in Spain’s “sí soy autónomo (yes, I’m self-employed)” movement, where platform workers protested against government regulations that failed to address the precarious conditions faced by wage earners across the labour market [175]. Research on crowdsourced workers in Nigeria has shown that the Western perspective on work precarity does not align with the life experiences of workers in developing countries. Therefore, categorizing all types of work under the vague umbrella of “platform labour” and forming mainstream interpretations about its precarity and technological control is insufficient. Instead, it is essential to deepen our understanding of the specific realities of workers [177].

As digital technologies, platformisation, and non-standard employment practices continue to spread into traditional industries, it becomes essential to move beyond polarized assessments of platform labour to better understand these novel forms of work and the consequences of the growing demand for gig work. While this study provides a comprehensive understanding of platform labour through systematic literature review methods, several limitations need to be acknowledged. First, reliance on the Web of Science Core Collection as a single data source, limited to SSCI-indexed English articles and reviews, may result in the omission of relevant studies, particularly those from non-Western countries. Second, the platform economy is evolving rapidly, with new research emerging continuously, potentially leaving out the latest developments. Finally, although the 174 articles included in the analysis underwent rigorous screening, publication bias may still exist, as studies with positive or significant results are more likely to be published and indexed.

Based on the findings and limitations of this study, future research could focus on the following directions to deepen and expand the understanding of platform labour. (1) Future research should incorporate non-English literature to capture regional variations in platform labour, particularly in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. (2) Given the heterogeneity of platform workers, future research should examine the experiences of diverse groups of workers, with particular attention to those in marginalised positions, such as migrant workers [178,179], women in male-dominated industries, disabled workers and elderly participants. (3) Future research should move beyond critiquing “algorithmic panopticon” to explore actionable solutions for ethical algorithm design, such as transparency mechanisms, worker participation in algorithm development [180], and the impact of “human-in-the-loop” systems on labour conditions. Additionally, investigating the effects of emerging technologies (e.g., generative AI for task automation) on platform labour can anticipate new labour dynamics and risks. (4) Recent research has started to investigate how extending traditional employment regulations, such as employer-side payroll taxes and minimum wages, to online labour platforms would affect market outcomes [181,182]. However, we still know relatively little about the effectiveness of regulatory innovations (e.g., “third-category worker” classifications, algorithmic impact assessments) and alternative models (e.g., platform cooperatives, collective bargaining for gig workers [183]) in mitigating precarity and advancing labour equity and social protection. (5) Future research should examine the long-term effects of platform labour (e.g., career mobility, health impacts [184], and intergenerational inequality transmission) and analyse intersectional influences (e.g., how gender [151,185], race, and class interact to shape platform workers’ experiences of discrimination or autonomy), providing evidence for targeted interventions.

As a rapidly developing social phenomenon, the future direction of the platform economy remains uncertain. Stakeholders, including platform companies, investors, workers, customers, and regulators, are actively shaping the competitive landscape of platform operations [89]. A growing body of empirical evidence indicates that platform workers are not passively accepting conditions imposed by platform labour. They are taking initiatives to resist harsh working conditions and advocate for their employment rights, income growth and labour protection by strategically manipulating algorithms, engaging in cross-platform work and participating in collective action [35,54,83,94,95,119,186,187,188]. In some countries and regions, regulatory and legislative activities on the platform economy are advancing, with the classification of platform workers emerging as a key issue. Policymakers are experimenting with different approaches, ranging from incorporating platform workers into existing employment law categories and classification tests [14,25,189] to creating new tests and employment categories specifically for platform workers [88,190,191]. These efforts share the goal of extending at least a basic level of labour protection to platform workers. At the same time, some scholars and activists advocate a more radical “platform cooperativism” movement [45]. In their view, establishing and promoting autonomous platform cooperatives may be a key strategy to counteract “digital slavery”, and to achieve genuine work autonomy and even labour liberation for workers [192].

Platform labour is reshaping labour markets globally, with profound implications for economic equity and social sustainability. To foster a more inclusive and decent form of platform labour, policymakers should consider the following recommendations: (1) Establish a clear “third-category worker” status for platform participants who are neither traditional employees nor independent contractors, ensuring access to core protections such as minimum wage guarantees, work-related injury compensation, and collective bargaining rights. Platforms should be mandated to disclose task allocation and payment algorithms to reduce information asymmetry, with penalties for discriminatory practices in ratings or task assignment. (2) Invest in digital infrastructure and digital literacy training to reduce participation barriers for low-income and marginalized groups, ensuring platform labour does not exacerbate existing inequalities. (3) Encourage multi-stakeholder dialogue among platforms, workers’ organizations, and civil society can facilitate balanced regulations that protect workers without stifling innovation.

In conclusion, platform labour is neither a utopian solution for flexible employment nor a dystopian nightmare of unregulated exploitation. Its future depends on addressing structural inequalities, protecting worker rights, and leveraging technological innovation for social good. By bridging academic research, policy design, and worker participation, we can build a platform economy that balances flexibility, equity, and sustainability, ensuring the benefits of digital transformation are shared by all.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z., C.L. and M.W.; Methodology, Y.Z. and C.L.; Investigation, Y.Z. and C.L.; Writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; Writing—review and editing, Y.Z., C.L. and M.W.; Funding Acquisition, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant number: 24CSH084).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

Y.Z. would like to acknowledge the Advanced Biomedical Imaging Facility of Huazhong University of Science and Technology for the support of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Schiller, D. Digital Capitalism: Networking the Global Market System; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Srnicek, N. Platform Capitalism; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, P.; Leyshon, A. Platform capitalism: The intermediation and capitalisation of digital economic circulation. Financ. Soc. 2017, 3, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2021. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/publications/world-employment-and-social-outlook-trends-2021 (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Schor, J.B.; Attwood-Charles, W.; Cansoy, M.; Ladegaard, I.; Wengronowitz, R. Dependence and precarity in the platform economy. Theory Soc. 2020, 49, 833–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S.A.; Green, A.; de Hoyos, M. Crowdsourcing and work: Individual factors and circumstances influencing employability. New Technol. Work. Employ. 2015, 30, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.J.; Graham, M.; Lehdonvirta, V.; Hjorth, I. Good Gig, Bad Gig: Autonomy and Algorithmic Control in the Global Gig Economy. Work Employ. Soc. 2019, 33, 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundararajan, A. The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-Based Capitalism; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, E.J. Digital China’s informal circuits: Platforms, labour and governance. China Inf. 2020, 34, 294–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, J. Entrepreneurship, Informality and the Platform Economy. In Platform Labour and Global Logistics: A Research Companion; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2022; pp. 230–242. [Google Scholar]

- Deeming, C. Guy Standing (2011), The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class. London: Bloomsbury Academic. £19.99, pp. 198, pbk. J. Soc. Policy 2012, 42, 416–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, F. Digital Labour Markets in the Platform Economy: Mapping the Political Challenges of Crowd Workand Gig Work; Division for Economic and Social Policy: Bonn, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, K.M.; Maleki, A. Micro-entrepreneurs, dependent contractors, and instaserfs: Understanding online labor platform workforces. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 31, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney Thomas, K. Taxing the gig economy. Univ. Pa. Law Rev. 2018, 166, 1415–1473. [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg, A.L.; Vallas, S.P. Probing Precarious Work: Theory, Research, and Politics. In Precarious Work; Research in the Sociology of Work; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2017; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ravenelle, A.J. Hustle and Gig: Struggling and Surviving in the Sharing Economy, 1st ed.; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dubal, V. Winning the battle, losing the war? Assessing the impact of misclassification litigation on workers in the GIG economy. Wis. Law Rev. 2017, 2017, 739–802. [Google Scholar]

- Heeks, R.; Gomez-Morantes, J.E.; Graham, M.; Howson, K.; Mungai, P.; Nicholson, B.; Van Belle, J.-P. Digital platforms and institutional voids in developing countries: The case of ride-hailing markets. World Dev. 2021, 145, 105528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. New Forms of Employment. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2015/new-forms-employment (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- van Doorn, N. Platform labor: On the gendered and racialized exploitation of low-income service work in the ‘on-demand’ economy. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2017, 20, 898–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushner, S. The freelance translation machine: Algorithmic culture and the invisible industry. New Media Soc. 2013, 15, 1241–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Stefano, V. The Rise of the ‘Just-in-Time Workforce’: On-Demand Work, Crowd Work and Labour Protection in the ‘Gig-Economy’. SSRN Electron. J. 2015, 37, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, P. The Quantified Self in Precarity: Work, Technology and What Counts; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 1–234. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblat, A.; Stark, L. Algorithmic Labor and Information Asymmetries: A Case Study of Uber’s Drivers. Int. J. Commun. 2016, 10, 3758–3784. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, A.; Stanford, J. Regulating work in the gig economy: What are the options? Econ. Labour Relat. Rev. 2017, 28, 420–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandini, A. Digital labour: An empty signifier? Media Cult. Soc. 2021, 43, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.; Hjorth, I.; Lehdonvirta, V. Digital labour and development: Impacts of global digital labour platforms and the gig economy on worker livelihoods. Transf. Eur. Rev. Labour Res. 2017, 23, 135–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howcroft, D.; Bergvall-Kåreborn, B. A Typology of Crowdwork Platforms. Work. Employ. Soc. 2018, 33, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M.; Cameron, L.; Garrett, L. Alternative Work Arrangements: Two Images of the New World of Work. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 473–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandini, A. Labour process theory and the gig economy. Hum. Relat. 2018, 72, 1039–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, M.; Zysman, J. Chapter 1 Work and Value Creation in the Platform Economy. In Work and Labor in the Digital Age; Research in the Sociology of Work; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2019; pp. 13–41. [Google Scholar]

- Jabagi, N.; Croteau, A.-M.; Audebrand, L.; Marsan, J. Gig-workers’ motivation: Thinking beyond carrots and sticks. J. Manag. Psychol. 2019, 34, 192–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irani, L. Difference and Dependence among Digital Workers: The Case of Amazon Mechanical Turk. South Atl. Q. 2015, 114, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, T.; Chen, C.; Frey, C.B. Drivers of disruption? Estimating the Uber effect. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2018, 110, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veen, A.; Barratt, T.; Goods, C. Platform-Capital’s ‘App-etite’ for Control: A Labour Process Analysis of Food-Delivery Work in Australia. Work Employ. Soc. 2020, 34, 388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenelle, A.J.; Kowalski, K.C.; Janko, E. The Side Hustle Safety Net: Precarious Workers and Gig Work during COVID-19. Sociol. Perspect. 2021, 64, 898–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, J.; Kincaid, R. Gig Work and the Pandemic: Looking for Good Pay from Bad Jobs During the COVID-19 Crisis. Work. Occup. 2023, 50, 60–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, L.; Blank, G.; Quan-Haase, A. The winners and the losers of the platform economy: Who participates? Inf. Commun. Soc. 2020, 23, 681–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtch, G.; Carnahan, S.; Greenwood, B.N. Can You Gig It? An Empirical Examination of the Gig Economy and Entrepreneurial Activity. Manag. Sci. 2018, 64, 5497–5520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peticca-Harris, A.; deGama, N.; Ravishankar, M.N. Postcapitalist precarious work and those in the ‘drivers’ seat: Exploring the motivations and lived experiences of Uber drivers in Canada. Organization 2018, 27, 36–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, O.; Borland, J.; Charlton, A.; Singh, A. The Labour Market for Uber Drivers in Australia. Aust. Econ. Rev. 2022, 55, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.; Burtch, G.; Hong, Y.; Pavlou, P.A. Unemployment and Worker Participation in the Gig Economy: Evidence from an Online Labor Market. Inf. Syst. Res. 2020, 31, 431–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Joshi, K.D. Why Individuals Participate in Micro-task Crowdsourcing Work Environment: Revealing Crowdworkers’ Perceptions. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2016, 17, 648–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schor, J.B.; Attwood-Charles, W. The “sharing” economy: Labor, inequality, and social connection on for-profit platforms. Sociol. Compass 2017, 11, e12493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doucette, M.H.; Bradford, W.D. Dual Job Holding and the Gig Economy: Allocation of Effort across Primary and Gig Jobs. South. Econ. J. 2019, 85, 1217–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]