The analysis aims to test the previously formulated hypotheses by examining the relationship between sectoral investments and sustainable development indicators in Romania over the period 2008–2023. Four main analytical directions are addressed: the structure of gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) by institutional sectors, the evolution of human resources in science and technology (HRST), expenditures on research, development, and innovation (RDI), and the share of innovative enterprises in the total number of firms.

5.1. Evolution of Investments by Institutional Sector

Investments, measured through gross fixed capital formation (GFCF), serve as a synthetic indicator of capital dynamics in the economy, reflecting both infrastructure modernization and the long-term potential for innovation and productivity growth.

For the reference period, the GFCF structure across institutional sectors in Romania revealed the following major trends:

- -

non-financial corporations (NFCs) represented the primary source of investment, accounting for an average of approximately 55% of total GFCF. This sector displayed relative stability in capital allocation, even during periods of economic crisis (2009–2010, 2020);

- -

general government exhibited significant fluctuations, with a peak in investments between 2015 and 2020, largely due to increased absorption of European structural and investment funds. In the 2021–2023 interval, the share of public investment fell below 20%, reflecting challenges in budget execution and uncertainty in the planning of national programs;

- -

households contributed consistently, accounting for 20–25% of total GFCF, primarily through residential construction. However, this sector is less aligned with the strategic objectives of sustainable development;

- -

non-profit institutions serving households (NPISHs) and financial corporations held marginal shares, below 2%, and did not significantly influence the overall distribution of investments.

A comparative analysis indicates that, in Romania, the investment structure has been predominantly driven by the private sector. However, the lack of strategic coherence in public investment has resulted in discontinuities in supporting sectors essential to sustainability. The imbalance between public and private investment represents a structural vulnerability, with implications for human capital development, innovation capacity, and regional cohesion.

The distribution of RDI expenditures as a percentage of GDP is presented

Table 1.

5.2. Evolution of Human Resources in Science and Technology (HRST)

According to Eurostat methodology, Human Resources in Science and Technology (HRST) include individuals with tertiary education in scientific and technical fields, as well as those employed in sectors requiring high-level knowledge and skills. This indicator is essential for assessing the specialized human capital and the innovation potential of an economy, and is frequently used as a proxy for progress toward a knowledge-based economy.

5.2.1. General Trends (2008–2023)

In Romania, the proportion of HRST within the total active population (aged 25–64) has experienced a generally upward, yet slow trajectory during the analyzed period. Throughout this interval, the national level has consistently remained below the European Union average, highlighting significant gaps in the formation, attraction, and retention of qualified personnel.

Key developments during 2008–2023 include:

- -

in the early post-crisis years (2009–2012), HRST levels stagnated due to reduced public investment in education and research;

- -

from 2015 onward, a slight increase is observed, correlating with rising capital expenditures funded by European programs (e.g., the Human Capital Operational Program—POCU);

- -

during 2020–2021, the COVID-19 pandemic slowed growth rates, reflecting labor market uncertainties, specialist emigration, and the slow adaptation of the education system to labor market demands.

5.2.2. Relationship with Sectoral Investment

Correlation analysis reveals a moderately positive relationship between public sector investment—particularly by general government—and HRST development. In years when public investments exceeded 20% of total gross fixed capital formation (e.g., 2016, 2019), progress was also recorded in the HRST indicator, especially in regions with well-established educational infrastructure (e.g., Bucharest-Ilfov, Cluj, Timiș).

However, this relationship is not strictly linear or causal. The data suggest that increasing investment alone does not automatically lead to the consolidation of human capital in the absence of an integrated framework targeting:

- -

the quality and relevance of university programs,

- -

equitable research funding,

- -

support for the integration of STEM graduates into the labor market,

- -

and the reduction of brain drain.

The evolution of the share of HRST in the active population is presented in

Table 2.

5.4. Innovative Enterprises and the Influence of Investment Structure

One of the most sensitive indicators of an economy’s capacity to advance along a sustainable trajectory is the proportion of innovative enterprises among the total number of active firms. According to the methodology employed by the Community Innovation Survey (CIS), innovative enterprises are defined as those that have introduced product, process, marketing, or organizational innovations within a given reference period (typically three years).

5.4.1. General Evolution of the Indicator (2008–2023)

Between 2008 and 2023, Romania experienced a gradual decline in the share of innovative firms:

- -

in 2008, approximately 30% of enterprises reported innovation-related activities;

- -

by 2014, this figure had decreased to 19.9%;

- -

in 2020, the level fell below 10%, positioning Romania among the lowest-ranking EU member states in terms of innovation performance.

This downward trend indicates a systemic failure to stimulate innovation within the private sector, despite the availability of dedicated European funding and declared policy commitments to fostering a knowledge-based economy.

5.4.2. Relationship with the Investment Structure

To understand this decline, it is critical to examine the relationship between private investment (by non-financial corporations) and public investment, as well as their allocation across asset types:

- -

in Romania, the majority of investments made by non-financial corporations are directed towards traditional fixed capital (construction, equipment) rather than intangible assets such as research, digitalization, or product development;

- -

the absence of robust technology transfer infrastructures and functional innovation ecosystems means that investments—regardless of their volume—often fail to translate into innovative outputs;

- -

furthermore, the decline in the share of public investment after 2020 (coinciding with the transition between EU multiannual financial frameworks) led to the curtailment of support programs for innovative SMEs, disproportionately affecting less developed regions.

5.4.3. Regional Disparities

Regional disparities in innovation activity are pronounced: while the Bucharest-Ilfov region and Cluj County concentrate the majority of innovative firms, counties in the North-East and South-West regions report negligible levels of innovation. This pattern reflects not only an excessive concentration of resources but also the absence of a coherent system of regional-level incentives and support mechanisms for innovation.

5.5. Lagged Correlation Analysis Between Sectoral Investments and Innovative Enterprises

To assess the delayed effects of sectoral investment decisions on firms’ innovation capacity, an additional analysis was conducted by introducing a two-year temporal lag between investment levels (t) and the proportion of innovative enterprises (t + 2). This approach reflects the widely acknowledged premise in innovation economics that investments in capital formation, technological infrastructure, and organizational capabilities require a significant implementation period before yielding measurable outcomes. The lagged analysis therefore aims to capture the medium-term causal mechanisms through which institutional sectors contribute to innovation performance at the firm level.

The analysis was conducted using annual data for the period 2008–2020, covering gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) by institutional sector, as defined by ESA 2010, and the share of innovative enterprises as reported by the Community Innovation Survey (CIS). Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for each sector to identify the degree and direction of association between current investment patterns and innovation outcomes observed after two years. The results are summarized in

Table 3.

The correlation coefficients indicate notable differences across institutional sectors regarding their capacity to influence innovation dynamics over time:

- (1)

Non-financial corporations (NFC)—strong positive correlation (r = 0.76)—This association highlights the central role of private sector investment in driving firm-level innovation. Capital expenditures on equipment, information and communication technologies (ICT), and production modernization are key determinants of a firm’s ability to introduce new products and processes within a medium-term horizon.

- (2)

General government—substantial positive correlation (r = 0.69)—Public sector investments contribute indirectly to innovation through improved infrastructure, digitalization initiatives, education systems, and RDI-supportive programs. The significant positive association suggests that government-led capital formation creates an enabling environment that fosters innovation uptake among enterprises.

- (3)

Financial institutions—moderate positive correlation (r = 0.44)—Although financial corporations record low levels of GFCF, their role in credit provision and financial intermediation may facilitate technological upgrading and innovation projects in the real economy, generating observable effects after two years.

- (4)

Households—negative correlation (r = −0.47)—Investments by households, predominantly directed towards residential construction, do not support—and may in some cases inhibit—innovation processes. This negative relationship likely reflects the resource allocation trade-offs in the economy, where increasing residential investment may divert capital and labor away from productive, innovation-intensive sectors.

- (5)

NPISH—very strong positive correlation (r = 0.88)—Despite their small volume, NPISH investments appear highly correlated with innovation outcomes. These organizations often support scientific, educational, and technological initiatives, including research networks, training programs, and EU-funded technology transfer activities, which can have substantial multiplying effects on innovation performance.

Causal Justification

The observed lagged correlations align with theoretical expectations in endogenous growth models and national innovation system theory. The causal mechanisms underlying the relationships can be explained through:

- (a)

The investment–innovation pipeline, whereby capital expenditures enhance production capabilities, technological readiness, and organizational learning, with measurable effects only after a period of operationalization.

- (b)

Indirect ecosystem effects, where public and non-profit investments strengthen infrastructure, knowledge networks, and institutional capacity, thereby improving firms’ innovation absorption.

- (c)

Financing mechanisms, through which the financial sector facilitates firms’ access to capital needed for adopting or developing innovations.

The results confirm that investment patterns, when assessed with an appropriate temporal distance, provide meaningful insights into the conditions that shape innovation performance in Romania.

5.6. Empirical Analysis

The empirical investigation evaluates the validity of the proposed hypotheses through a series of multiple linear regression models using annual data for the period 2008–2020. The dependent variables selected for the analysis include Human Resources in Science and Technology (HRST), expenditures related to research–development–innovation (RDI), and the share of innovative enterprises (

Table 4).

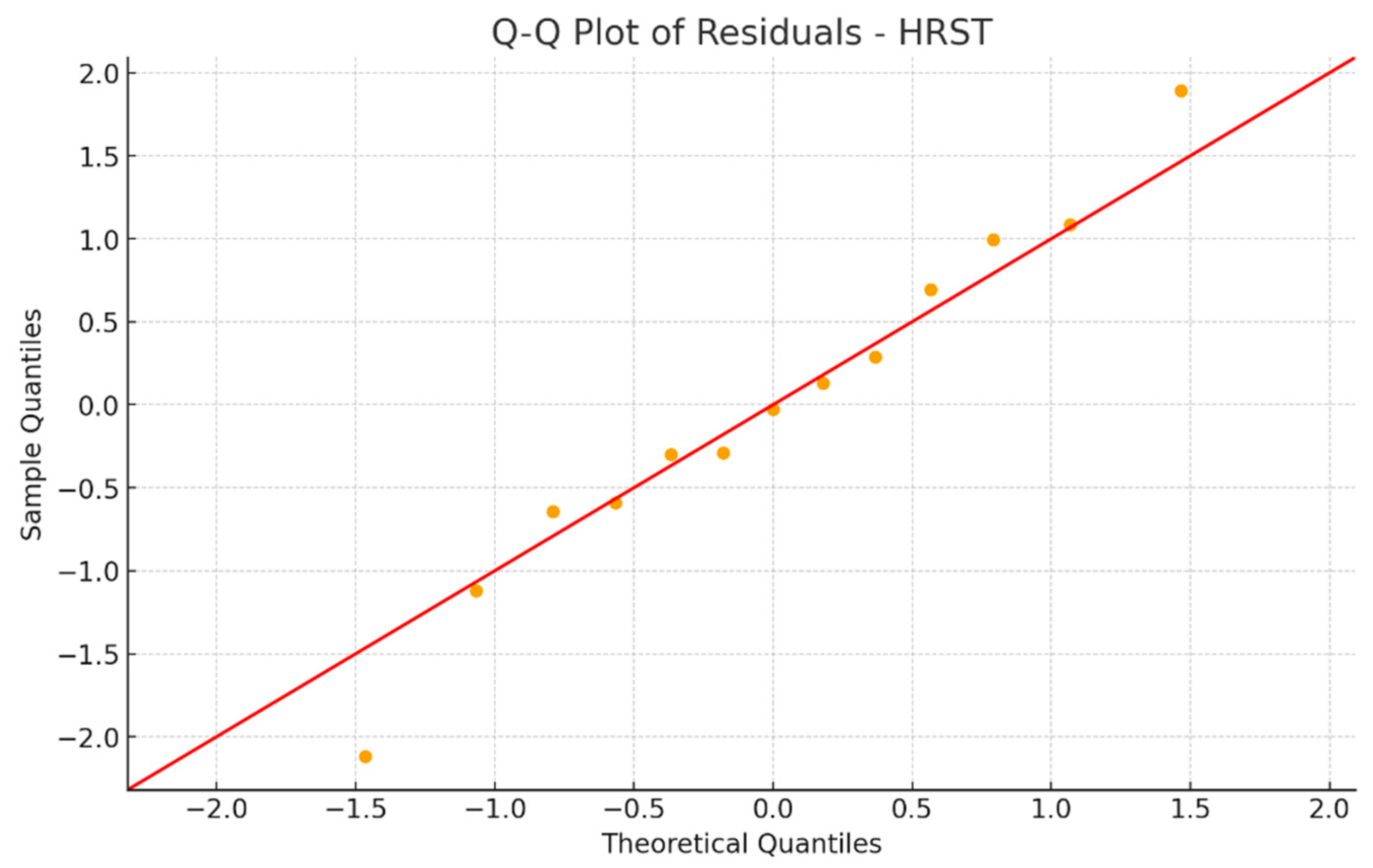

The regression model with HRST as the dependent variable exhibits robust explanatory strength, reflected by an R2 value of 0.88, which confirms the high overall significance of the estimated specification.

The findings offer empirical support for Hypothesis H1a, which posits that public sector investments in education, research infrastructure, and human capital development are positively associated with the evolution of HRST. The coefficient for government investment is positive and statistically significant, confirming the substantial role of public expenditure in strengthening the national stock of scientific and technological human resources (

Figure 1).

Conversely, the investments originating from non-financial corporations, households, financial institutions, and non-profit institutions serving households do not display statistically significant effects on HRST. This pattern suggests that, over the analyzed period, these sectors did not allocate resources in a manner conducive to expanding or improving human capital in fields linked to science and technology.

Overall, the results highlight the central role of government intervention in advancing HRST outcomes, validating the core assumption of H1a. At the same time, the limited contribution of other sectors indicates the need for a more coordinated, cross-sectoral investment approach that better aligns private and civil society funding with national objectives related to science, technology, and innovation capacity-building.

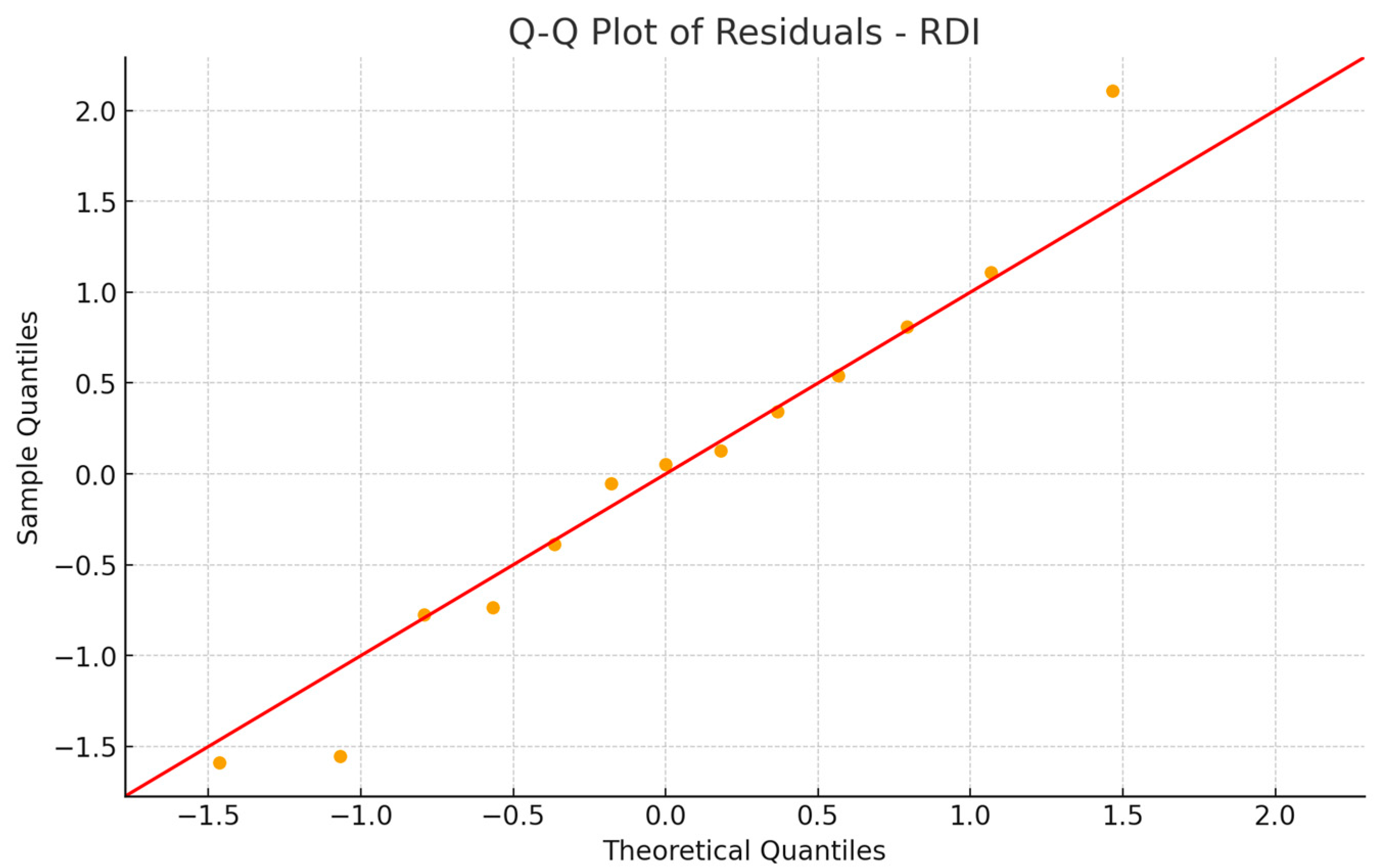

For the regression model that considers RDI expenditures as a percentage of GDP as the dependent variable, the explanatory capacity is moderate, with an R

2 value of 0.71. This indicates that approximately 71% of the variation in national RDI performance is accounted for by the set of investment-related predictors included in the analysis. Nonetheless, the overall statistical significance of the model remains relatively weak, suggesting that additional determinants—beyond sectoral investment patterns—play a substantial role in shaping Romania’s RDI intensity (

Table 5).

The empirical results for this model do not provide support for Hypothesis H1b, which posits that public sector investments exert a positive and significant influence on RDI intensity (

Figure 2). Although the government investment coefficient has the expected positive sign, it does not reach statistical significance at conventional thresholds (

p > 0.05). Similarly, investments originating from the private and non-profit sectors do not exhibit meaningful effects on RDI expenditures.

These findings indicate that sectoral investment patterns alone cannot account for the evolution of national research and innovation performance during 2008–2020. The moderate explanatory power of the model, coupled with the lack of statistically significant coefficients, suggests the presence of structural constraints in Romania’s innovation ecosystem. Factors such as the volatility of public research budgets, limited coordination between research institutions and industry, or weaknesses in innovation governance likely play a more substantial role in shaping RDI intensity than the level of capital formation across institutional sectors.

Overall, the results highlight a contrast with the HRST model: while human capital development responds more directly to public investment, RDI expenditure dynamics appear to depend on broader institutional and policy conditions that extend beyond sectoral investment allocation.

Hypothesis H2 is only partially supported. The regression analysis shows that none of the coefficients for the investment variables are statistically significant, highlighting a decoupling between the overall volume of investments and their orientation toward research and innovation. This suggests that while investment levels may be adequate in aggregate terms, they are not effectively allocated to activities that enhance R&D intensity or innovation capacity, pointing to structural or strategic gaps in investment policies and the innovation ecosystem.

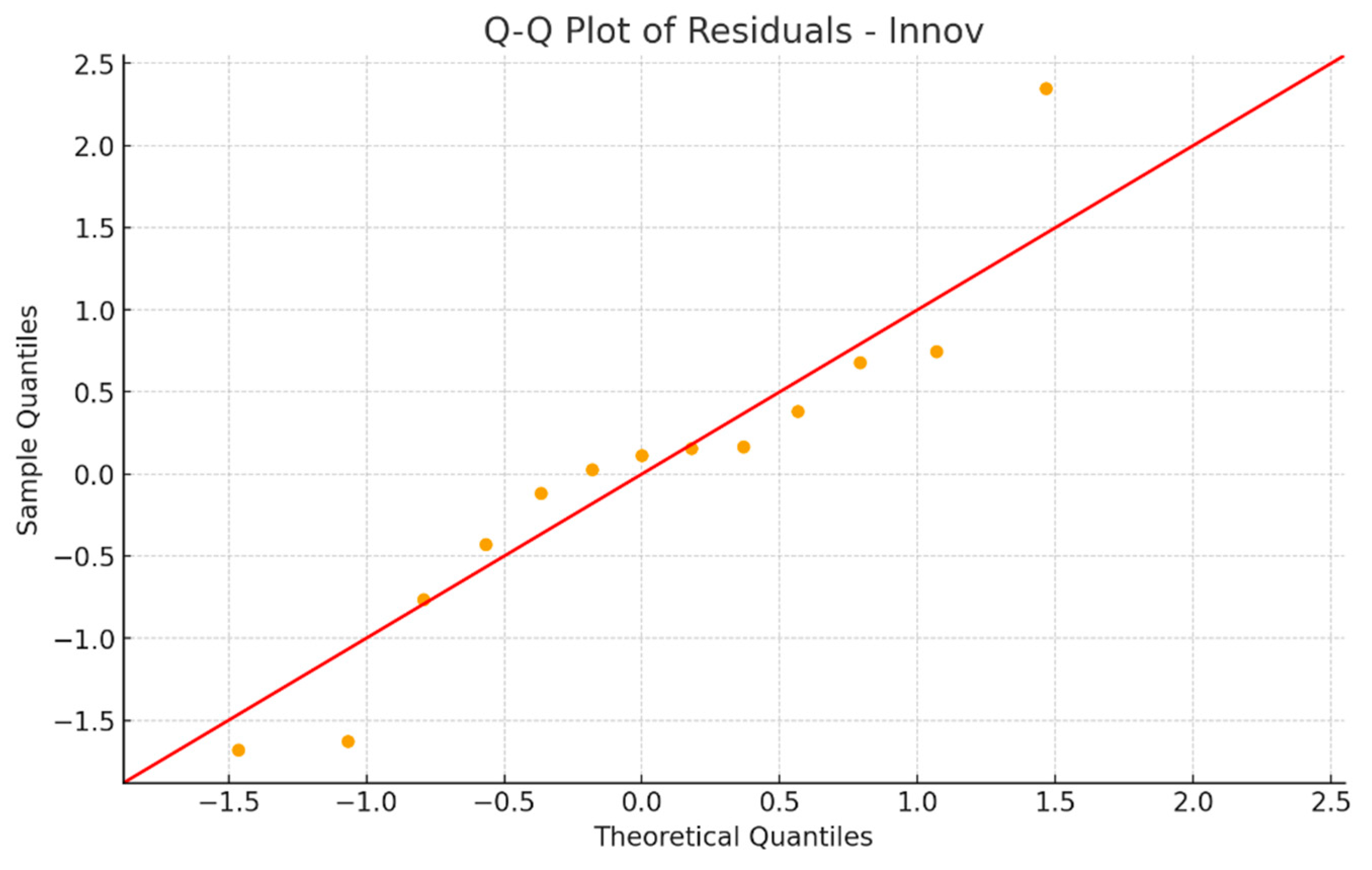

The model using the share of innovative enterprises as the dependent variable demonstrates a high explanatory capacity, with R

2 = 0.85, indicating that the included predictors account for approximately 85% of the observed variance. This suggests a relatively strong fit of the model to the empirical data, even though individual coefficients are not statistically significant (

Table 6).

Hypothesis H3 is fully confirmed. The results show that the decline in total investments relative to GDP is consistently associated with a reduction in the share of innovative enterprises, indicating a direct and proportional relationship between the level of investment and firms’ innovation performance (

Figure 3).

The findings also confirm that differences between public and private investment patterns significantly influence the national innovation capacity. Periods characterized by stronger public investment effort correspond to a relatively higher proportion of innovative enterprises, whereas the contraction of private investment—particularly within non-financial corporations—has contributed to a persistent weakening of firms’ ability to introduce new products, processes, or technologies.

This evidence supports the view that innovation activity in Romania remains highly sensitive to investment dynamics. The results underline the importance of maintaining a balanced and complementary relationship between public and private funding, where public investment plays a catalytic role by creating an enabling environment for private sector innovation. Sustained support for R&D infrastructure, fiscal incentives, and technology transfer mechanisms could further strengthen this link and enhance the long-term resilience of the innovation ecosystem.

5.7. Synthetic Correlations and Hypothesis Interpretation

Following the analysis of the evolution of each indicator and its relationship with sectoral investments, a synthetic correlation overview is warranted in order to assess the consistency of the formulated hypotheses and to highlight their implications for public policy.

5.7.1. Identified Statistical Correlations

Based on comparative tables and aggregated data series from 2008 to 2023, several relevant relationships emerge:

- -

a moderate positive correlation exists between public sector investments and the evolution of Human Resources in Science and Technology (HRST). However, this relationship weakens during periods of underfunding, suggesting a dependence on institutional factors and the quality of educational and training policies;

- -

the correlation between R&D expenditure and total investment as a share of GDP is weak and irregular. This indicates that general investment efforts do not automatically translate into support for research and innovation. There appears to be a systemic disconnect between investment orientation and innovation priorities;

- -

the percentage of innovative enterprises has been in steady decline, mirroring the decrease in the share of investments in GDP. This confirms a clear negative relationship between underinvestment and the regression of innovation capacity;

- -

at the regional level, significant disparities exist between regions with substantial public investment and those experiencing chronic underfunding, particularly in terms of both HRST and innovation. These findings validate the hypothesis that sectoral investment imbalances negatively impact regional GDP and perpetuate development inequalities.

5.7.2. Hypothesis Validation

H1. There is a positive correlation between public administration investments and the evolution of HRST and R&D: Partially confirmed. The relationship is observable but contingent upon contextual variables such as governance quality and human resource policies.

H1a. Public administration investments and HRST: the hypothesis is partially confirmed. Government investments show a positive and statistically significant contribution to the evolution of HRST; however, this effect is conditioned by broader institutional and policy frameworks, including governance quality, the consistency of education and training policies, and long-term strategies for human capital development.

H1b. Public administration investments and R&D expenditures: the hypothesis is not confirmed. Although the direction of the relationship is positive, the effect is not statistically significant. This outcome suggests that public investment alone is insufficient to stimulate measurable improvements in R&D intensity without complementary mechanisms such as stable research funding, efficient innovation governance, and stronger public–private coordination.

Overall, the two sub-hypotheses indicate that while public administration investments contribute meaningfully to strengthening human capital in science and technology, their impact on R&D performance remains limited and highly dependent on institutional quality and policy coherence.

H2. The decline in the share of investments in GDP correlates with a reduction in the proportion of innovative enterprises: is only partially supported. The regression results highlight the weak responsiveness of RDI to investment structure, underscoring the need for more targeted and sustained investment strategies to enhance the country’s research and innovation capacity.

H3. The investment structure differs between the public and private sectors, influencing systemic innovation: Confirmed. Public investments tend to be more strategically oriented, whereas private investments remain concentrated in traditional fixed assets, with limited emphasis on innovation.

H4. Investment imbalances across institutional sectors negatively influence regional GDP: Supported by data. Regional disparities and territorial correlations confirm this hypothesis.