Abstract

Sustainable Development (SD) is a key concept of the modern era, presenting significant challenges for policymakers worldwide. Due to its holistic and complex nature, the empirical assessment of people’s perceptions about SD, as well as their dependence on different demographic variables such as gender, may become a difficult research task. This work first aimed at assessing the validity and reliability of data regarding adult perceptions about SD and subsequently at examining for gender differences by taking the case of Greek civil servants. Data collection was accomplished via the use of the Greek version of the Sustainability Consciousness Questionnaire (SCQ-GR), an instrument originally applied among Swedish young adults (18–19 years old). The sample consisted of 631 adults serving in the Greek public sector. The data showed excellent overall internal reliability by maintaining all 50 items of the original instrument. For testing data validity, the conduction of exploratory factor analysis (EFA) resulted in four main components, which collectively account for 69.41% of the total variance. Component 1, comprising 19 items, refers to “attitudes and behaviors” regarding SD. Component 2, comprising 18 items, refers to “beliefs” regarding SD. Component 3, comprising 8 items, pertains to “social-environmental activism” for SD. Finally, Component 4, comprising 5 items, refers to “attachment” to SD. The four components identified with EFA were used as input for conducting confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The performance of CFA resulted in a model exhibiting a good fit to the data, thus providing strong additional evidence for its validity. Subsequently, evidence for configural, metric, scalar, as well as strict measurement invariance was obtained, thus allowing for meaningful comparisons between genders. Females were shown to outperform males in all components (with Cohen’s d effect sizes ranging between 0.216 and 0.383) except for the component referring to social–environmental activism, for which no statistically significant gender difference was observed. The good psychometric qualities of SCQ-GR provide strong support for its use in obtaining valid assessments of perceptions regarding sustainable development and possible influencing variables (such as gender) among Greek civil servants and potentially other adult groups as well.

1. Introduction

Since its appearance in the report of the World Commission on Environment and Development in 1987, commonly known as the Brundtland Report [1] the concept of sustainable development (SD) has gained a powerful position in many aspects of human life and activity such as academic research, national and international law and politics, business and economy, agriculture, health, industry and urban development [2].

The definition of SD as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”, provided in the Brundtland Report, still remains very popular even though it has been criticized as being a “political fudge” which is based “on an ambiguity of meaning in order to gain widespread acceptance” [3]. Since then, several other definitions of SD have appeared, which can be categorized into five different (in some cases overlapping) categories, based on their perspectives as follows [4].

(1) In the conventional economists’ perspective, SD corresponds to a steady state possessing normative features and characterized by efficiency in the sense of an attainable level of consumption. It is a perspective that neglects the impact of economic activities on the environment and therefore has limited scope. (2) In the non-environmental degradation perspective, emphasis is given to principal ideas of environmental economics, such as the following: scarcity of natural resources, consumption cannot be continued forever, the fact that nature’s carrying capacity should not be exceeded and the non-depletion of environmental capital. This perspective undervalues the importance of social aspects of SD, “such as the interrelation between the environment and human rights, corruption, poverty, illiteracy, child mortality, and epidemics”. (3) In the integrational perspective, which is considered more complete relative to the first two, the environmental, social and economic dimensions of SD and their interactions are considered. This perspective does not give enough attention to the temporal factor, i.e., the three dimensions of SD as a function of both the present and the future timeframe. (4) In the intergenerational perspective, the focus is on time continuity and the assurance of equity between present and future generations, sometimes lacking the incorporation of the environmental, social and economic aspects of SD. (5) Finally, in the holistic perspective, the integrational and intergenerational perspectives are combined, so that SD is associated with two simultaneous and dynamic equilibria, one involving the three dimensions of SD and the other the temporal factor.

The terms “sustainable development” and “sustainability” are often considered synonymous in the literature and “difficult to tease apart” [5], even though there is a lot of discussion regarding their differences. Thus, according to Robinson [6], the term “sustainable development” is usually adopted by “government and private sector organizations” while academicians and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) tend to prefer the use of “the term sustainability in similar contexts”. According to the same researcher [6], the use of the term “sustainable development” tends to reflect a “more managerial and incremental approach” while the term “sustainability” gives emphasis “where it should be placed” and that is “on the ability of humans to continue to live within environmental constraints”. As noted by Lozano [4], SD constitutes “the journey, path or process” which leads to “sustainability” which is thus conceived as an “ideal dynamic state”. In addition, the term “sustainable development” is often considered a confusing, fuzzy and vague term because the term “development” leads instantly to questions such as development of what and for whom. As pointed out by Jabareen [7], the concept of SD is accompanied by an ethical paradox, since development could be accomplished via “environmental modification, which requires deep intervention in nature and exhausts natural resources”. On the other hand, the term “sustainability”, even though it has the reputation of a buzzword, “carries far less historical baggage” relative to “sustainable development” [5]. At this point, it will be noted that, for the purposes of the current work, the terms “sustainable development” and “sustainability” will be used interchangeably.

The most common conception of sustainability (as well as of sustainable development), whose origins and rigorous theoretical foundation is a matter of active academic debate, is the one of three sectors which refer to the environment, society and the economy and which are mentioned as either “pillars”, “dimensions”, “components”, “aspects”, “stool legs” or “perspectives” of sustainability [5]. To make the sustainability concept more tangible, different visual representations of the three dimensions of sustainability have been developed [4]. The two most common representations are a) a Venn diagram in the form of three interconnected circles with the resulting overlap representing sustainability and b) the nested model of three (not necessarily) concentric circles with economy, society and environment represented by the inner, middle and outer circle, respectively. [3,4]. In the case of the nested model, the series of circles reflects the sequential dependence of each sector/dimension: the economy is dependent on society, which, in turn, is dependent on the environment. Both models have been criticized, although to a different degree, for failing to depict the multi-layered and multi-faceted nature of the concept of sustainability [3] and “suffer from being highly anthropocentric, compartmentalized and lacking completeness and continuity” [4]. The representation of sustainability in three dimensions [4] constitutes an attempt to portray “the complex and dynamic equilibria among economic, environmental and social aspects, and the short-, long- and longer-term perspectives” of the concept. In fact, it is proposed [3,8] that the study and analysis of sustainable development should be based on a systems approach by considering “the emergent properties, complexity and interactions” of its three pillars deployed in both the spatial and temporal dimensions together with equity principles. An example of a systems perspective to approach the concept of sustainability has recently appeared [9].

Although the theoretical underpinnings of sustainable development may remain under debate, it is widely accepted that SD issues are becoming increasingly crucial for people’s lives, and the key to achieving sustainability is via the promotion of education for sustainable development, also referred to as ESD [10]. Consequently, it is essential to develop valid and reliable instruments to probe sustainability perceptions and, therefore, be able to accurately assess the effectiveness of ESD interventions or design new ones. These instruments must also reveal differences between groups (e.g., gender differences).

Therefore, the main aim of the current work is to examine the validity and reliability of the data collected among Greek adults, sampled specifically among in-service civil servants, in order to probe their perceptions regarding sustainable development. Civil servants were selected as the target group because they represent a diverse population in terms of education, age, and geography (residence). In addition, civil servants are the ones who are asked to apply all national legislation related to sustainable development and, therefore, their views, as well as their level of sustainability consciousness, are expected to be important factors for the achievement of the relevant goals that have been set. Another aim of the current work is to examine the (possible) role of gender in shaping the participants’ sustainability perceptions. Exploratory as well as confirmatory factor analysis were employed in order to examine data validity and reliability. In addition, measurement invariance testing of the collected data was administered to allow for valid comparisons between genders. The instrument used for the data collection is the Greek version of the Sustainability Consciousness Questionnaire (long version), briefly referred to as SCQ-L [11]. The corresponding Greek version of SCQ-L will be referred to as SCQ-GR. The need for conducting reliability and validity analysis of data collected via adaptation of an original instrument in a different language and therefore cultural context is vital [12]. In our case, in addition to a different cultural context, the SCQ-L instrument was administered in a different age group (adults with ages ranging between ca 25–65 y) relative to the original validated instrument, which included late adolescents of 18–19 y [11]. This is a fact that makes the necessity for examination of data validity and reliability even more pressing.

Summarizing, the current work is guided by the following two research objectives:

- (a)

- How valid and reliable are the data collected via the use of the Greek version of the Sustainability Consciousness Questionnaire (SCQ-GR) with regard to the perceptions of Greek civil servants about sustainable development?

- (b)

- What is the effect of gender with regard to the perceptions of Greek civil servants about sustainable development?

The manuscript is subsequently organized in five sections: Background, Methods, Results, Discussion and Conclusions, corresponding to Section 2, Section 3, Section 4, Section 5 and Section 6, respectively.

In Section 2, extensive reference to the existing literature related to the main objectives of this work will be made. Section 3 will refer to the processes of sample selection and instrument adaptation. Section 4 will initially involve a detailed presentation of the outcomes concerning data validity and reliability as obtained via the statistical methods of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. The different modes of use of the statistical methods are incorporated in the presentation in order to ensure a clear understanding of the results obtained. Subsequently, Section 4 will involve presentation of the outcomes concerning the measurement invariance of the collected data, since this is a major requirement for meaningful comparisons between the two distinct gender subgroups of the sample (females and males). Section 4 will be concluded with reference to the comparison of the two genders with regard to their perceptions about sustainable development. In Section 5, the results reached will be discussed in light of the literature presented in Section 2. In this section, specific reference will also be made to the limitations of the current work, its implications, as well as future research directions. Finally, the main conclusions reached in this work will be briefly presented in a dedicated Section 6.

2. Background

Initially, in this section, the main instruments that have been used in order to probe perceptions regarding sustainable development will be briefly discussed. Subsequently, a separate subsection will be devoted specifically to the presentation of the cases of the use of SCQ, which is the instrument employed in the current work. In the third subsection, research findings concerning the relationships between the cognitive and attitudinal/behavioral domains of sustainability perceptions will be briefly reviewed. The information presented in the first three subsections of the Background is necessary in order to assess the quality of the validity and reliability of our data and to discuss the correlations between the identified factors as extracted from the validation model of our study. Finally, a fourth subsection will include a reference to the main research findings regarding the effect of gender on sustainability perceptions, in order to be able to discuss the relevant results regarding the second objective of our study.

2.1. Instruments Assessing Perceptions About Sustainable Development

Several psychometric instruments that aim to assess sustainability perceptions have appeared in the last two decades. In most cases, they are multidimensional since they aim to cover all three dimensions of SD, namely environment, society and economy, and, at the same time, consider the three main areas in which sustainability literacy is expressed, namely the cognitive (often referred with the term knowledge), attitudinal and behavioral domains [13,14].

Excluding the SCQ instrument [11], reference will be made to a total of 21 publications. In most publications (12), the target group is young adults (mainly University students) with ages less than (ca.) 30 y [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Secondary school students constitute the target group of five publications [27,28,29,30,31], while in five publications the sustainability perceptions of the general adult public (>18 y up to senior citizens) are examined [19,32,33,34,35]. Finally, primary school students constitute the target group of one publication [30].

Most of the publications (10) report instruments which aim to probe the three main psychological constructs concerning sustainability, namely knowledge, attitudes and behavior, and will be briefly presented first. More specifically, Michalos and colleagues [27] developed a 50-item questionnaire aiming to probe Canadian secondary school students’ knowledge, attitudes and behaviors regarding SD as those concepts are conceived by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, UNESCO [13]. An updated version of the instrument, composed of 51 items, was presented by the same group a few years later [36]. The instrument developed by Michalos and colleagues was subsequently employed for assessing university students’ sustainability perceptions in Pakistan [17] and Mexico [25]. Moreover, the instrument, enriched with additional homemade questions to create a 70-item scale, was employed to measure university students’ knowledge, attitudes and behaviors towards SD and ESD in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) [18]. It is important to note that the “Michalos et al.” instrument [27] provided the starting point for the development of the SCQ instrument [11]. A 57-item instrument aiming to analyze Colombian university students’ knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP scale) related to sustainability was developed [21]. A 24-item scale aiming to probe the knowledge, attitudes and practices towards the sustainability efforts of a specific tertiary education institution in the UAE was developed for the students of the same institution [20]. Kirby and Zwickle [19] probed sustainability attitudes, knowledge and behaviors of both university students and the general public in the USA by using a composite 27-item instrument composed of the Assessment of Sustainability Knowledge (ASK) instrument and the Sustainability Attitudes Scale (SAS) [37] in addition to a question regarding how often participants were involved in five sustainability behaviors. A homemade instrument composed of 16 items was employed to probe Malaysian university students’ attitudes towards sustainability on campus and their perception of the University’s sustainability programs [24]. A more specialized instrument, which is specifically related to the 14th Sustainable Development Goal (SDG14) entitled “Life below water”, was developed to probe Taiwanese university students’ understandings of concepts regarding marine resources conservation and sustainability [22]. This 21-item instrument, known as the Marine Resources Conservation and Sustainable Concept scale (MRCSC), is composed of three dimensions (cognitive, socio-emotional and behavioral). Chen and colleagues [30] report the application of a 28-item questionnaire, which originates partly from SCQ [11], aiming to assess Chinese secondary as well as primary school students’ knowingness, attitudes and behavior towards SD.

The instruments in three publications aimed at probing mainly the cognitive aspect regarding the participants’ perceptions of sustainable development. More specifically, the “Students’ Perceptions on Sustainable Development” questionnaire was used by Tuncer [15] among university students in Turkey. This 25-item instrument was derived by using the 45-item Environmental Attitude Questionnaire as a basis [38]. The ASK questionnaire [37] was adapted for probing the sustainability knowledge of university students in Spain [23]. More recently, Vaikma [35] developed and validated a 22-item instrument (known as Sustainability Dimensions Perceptions Scale, SDPS) which measures consumer perception of four dimensions of sustainability related to society, economy, environment and health, across four countries (Estonia, France, Italy and Sweden).

In two publications, researchers developed instruments in order to mainly probe attitudes towards sustainability. Thus, Biasutti and Frate [16] developed the Attitudes towards Sustainable Development (ASD) 20-item scale for assessing sustainability attitudes of university students in Italy. The scale involved four dimensions: environment, society, economy and education. By using a four-item questionnaire, De Silva and Pownall [33] studied the attitudes towards sustainability of the general adult public in the Netherlands. The questions assessed the pairwise trade-offs between social well-being (people), financial well-being (profit) and environment (planet).

Five instruments concentrate mainly on assessing the behavioral domain of sustainability perceptions. Thus, the Self-Perceived Action Competence for Sustainability Questionnaire (SPACS-Q) is an instrument that was originally developed and validated among Swedish secondary school students [28] and more recently among German high school students [31]. The concept of action competence was measured via three components: knowledge of action possibilities, confidence in one’s own influence and willingness to act. A relevant instrument to SPACS-Q is the Action Competence in Sustainable Development Questionnaire (ACiSD-Q), which was specifically designed for measuring action competence in early adolescence (mean age = 11 y) when civic involvement is developed [29]. The ACiSD-Q was tested and validated among Belgian secondary school students. Čiarnienė and colleagues [32] employed a 38-item questionnaire in order to explore the manifestation of economically, environmentally and socially sustainable behavior among the Lithuanian general adult public.

Most recently, Fabio and colleagues [34] developed and validated an 18-item instrument for assessing sustainable behaviors of Italian adults (Sustainable Behavior Questionnaire, SBQ). The instrument was shown to consist of four factors, namely “purchase behavior and awareness”, “reusing and recycling”, “reducing” and “walking and use of public transport”.

Finally, in one case [26], a total of six constructs were assessed in addition to knowledge, attitude and behavior. The additional three constructs were willingness to act, self-efficacy and emotional connection with sustainability issues, and the relevant study involved the development of a 36-item instrument which was administered among university students in Spain.

2.2. The Sustainability Consciousness Questionnaire (SCQ)

The concept of sustainability consciousness (SC), referring to “an individual’s experience and awareness of sustainable development”, was introduced by Gericke and colleagues and operationalized into a psychometrically valid instrument, known as the Sustainability Consciousness Questionnaire (SCQ) [11]. The instrument aimed to cover the broad spectrum of sustainability in terms of the environmental, social and economic dimensions, and, at the same time, the concept of consciousness in terms of the cognitive, attitudinal and behavioral dimensions. The concept of sustainability consciousness may be seen as an extension of the concept of environmental consciousness to include the societal and economic perspectives in addition to the environmental ones. The theoretical framework that led to the operationalization of sustainability consciousness may be regarded as an adaptation of the one presented by Sánchez and Lafuente for environmental consciousness [39]. In the latter publication, the construct of environmental consciousness is defined “from a multidimensional and behaviour-oriented point of view in which environmental consciousness is related to pro-environmental behaviour” and consists of four interwoven dimensions: affective, dispositional, cognitive and active.

The development of SCQ used the instrument of Michalos and colleagues [27] as a starting point and gave rise to a long and short version of the instrument, referred to as SCQ-L and SCQ-S, consisting of 50 and 27 items, respectively. Both versions of SCQ include items in three psychometric constructs, which are referred to as knowingness, attitudes and behavior, with each of these constructs involving questions related to the three pillars of sustainability (environment, society and economy). The term knowingness was adopted [11] instead of the term knowledge to take account of the fact that the instrument does not aim to probe actual factual knowledge (objective truths) but the extent to which the participants recognize the importance of the SD-related issues and fundamentals.

During its development and before the appearance of the study reporting its validation [11], the instrument was employed by the members of the developing team in order to investigate the effectiveness of ESD programs in secondary schools in Sweden [40,41,42,43] and to provide evidence for the decline of Swedish students’ sustainability consciousness in adolescence [44].

Following the appearance of SCQ, several research teams have conducted studies for its adaptation together with statistical evidence for its reliability and validity (either in its short or the long version) in the following different languages and therefore cultural contexts: Mandarin (Taiwan) [45], Spanish [46,47], Japanese [48], Malaysian [49], Korean [50], Pakistani [51] and Portuguese [52]. These adaptations concerned the following age groups: adolescents [45,47], university students/young adults [46,49,50,51] and the general adult population [48,52]. In addition, during these adaptations, certain modifications of the original instrument were deemed necessary in several cases in order to allow the production of a valid and reliable instrument for the different cultural contexts. These modifications concerned either the omission of items [45,50,51,52] or the proposal of a different factor structure [48]. It is therefore interesting and important to discuss the characteristics of the SCQ-GR instrument brought out in this work in comparison with those of the original SCQ instrument [11] as well as the above-reported cultural adaptations.

The validated Spanish version of SCQ-S [46] was subsequently used by Morales-Baños and colleagues among university students of nautical activities [53]. The Swedish [11] and Mandarin [45] versions of SCQ-S were employed for a cultural comparison regarding the sustainability consciousness of Swedish and Taiwanese late adolescents (18–19 y) [54].

The SCQ instrument has been used via conducting reliability and validity testing of the collected data for exploring university students’ sustainability consciousness in India [55] and in a mixed group of participants from 18 different countries [56] as well as among primary school students of 10–11 y in Indonesia [57].

In several cases, the SCQ has been used via conducting only reliability testing (Cronbach’s α for internal consistency). These studies have been conducted in the following countries: China [58,59], Greece [60], Egypt [61], Pakistan [62] and Spain/Belgium/Sweden [63]. All of the above studies refer to university students with the exception of one case [63], where the target group is made up of the general adult population as well as adolescents.

Finally, the SCQ has been used among university students, without conducting any type of reliability or validation testing, in China [64] and Egypt/Saudi Arabia [65,66].

As evidenced from the above listings, the SCQ instrument has been rarely used for probing the sustainability consciousness of the adult population, and the current work is intended to fill this gap as well.

2.3. Relationships Between Cognitive, Attitudinal and Behavioral Domains of Sustainability Perceptions

In this section, representative empirical research findings regarding the relationships between the cognitive, attitudinal and behavioral domains of sustainability perceptions will be briefly reviewed. The cognitive domain will be referred to with the general term “knowledge”, under which both objective (or otherwise factual) knowledge as well as subjective (or otherwise perceived or self-rated) knowledge are included [67]. Subjective knowledge can be considered similar to the term “knowingness” employed by Gericke and colleagues [11] during the development of the SCQ instrument. Before presenting the empirical findings, we will shortly refer to the main theoretical and analytical underpinnings regarding the determinants of pro-environmental behavior with an emphasis on the roles of environmental knowledge and attitudes as predictive variables. The need for environmental protection and preservation has been one of the main driving forces for the maturation of the concept of sustainable development/sustainability. Therefore, the use of the theoretical and analytical frameworks regarding pro-environmental behavior is relevant for examining pro-sustainable behavior as well.

Researchers have developed and employed different psychological theories in order to provide compact models of pro-environmental behavior. Such theories are the theory of planned behavior, TPB [68], the norm activation model, NAM [69], the value-belief-norm (VBN) model [70] and the focus theory of normative conduct [71].

The use of the theoretical models together with the incorporation of personal and social factors has led to the development of numerous analytical models/frameworks which aim to delineate the determinants of pro-environmental behavior, a fact which indicates the complexity of the endeavor. Some of the most common analytical frameworks are reviewed in Kollmuss and Agyeman [72], who also analytically present different categories of factors, namely demographic, external and internal factors, which have been proposed to exert influence on pro-environmental behavior. In the same work [72], the two researchers end up by proposing their own model of pro-environmental behavior, which has the following characteristics: The relationship between knowledge and behavior is only indirect. Knowledge, attitudes, values and emotions make up a complex (called environmental consciousness) that “in turn is embedded in broader personal values and shaped by personality traits and other internal as well as external factors.” The synergistic action of internal and external factors exerts the largest positive influence on behavior.

By conducting a meta-analysis of a total of 57 samples, Bamberg and Möser [73] reached another analytical framework of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behavior in which constructs of both the TPB and NAM theories were employed. More specifically, structural equation modeling (SEM) resulted in a model in which three constructs, namely attitudes, perceived behavioral control and personal moral norms, are the main predictors of pro-environmental behavior, but their effect is mediated by behavioral intention. These three constructs are influenced by a total of four other determinants, namely problem awareness, social norms, internal attribution and feelings of guilt. It is interesting that problem awareness, which is the construct related to knowledge, was shown to play an important role in determining behavioral intention (and in turn behavior), but only indirectly. The links of the Bamberg and Möser framework [73] with VBN theory [70] are also remarkable. In fact, VBN places special emphasis on the direct role of personal norms in predicting “environmentally significant” behavior as well as on the contribution of perceived ability to reduce threat (AR) in shaping personal norms. The AR construct of VBN is closely related to the construct of perceived behavioral control in Bamberg and Möser [73].

In an effort to operationalize the concept of environmental consciousness, Sánchez and Lafuente [39] proposed an analytical framework that sought to integrate the most common theories of environmental concern based on a sociological perspective as well as theories of behavior. Their framework covers four dimensions: the affective, which refers to general beliefs and values; the dispositional, which is related to personal attitudes; the cognitive, which refers to knowledge/information; and the active dimension, which corresponds to pro-environmental behavior. In this framework, behavior (the active dimension) is directly interrelated with the dispositional dimension in a bi-directional manner. The dispositional, affective and cognitive dimensions are interrelated with each other in both directions as well.

In 2014, Gifford and Nilsson [74] provided an updated review of the research findings regarding the personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behavior. They refer to a large number of influencing factors (18 in total), a fact that indeed “suggests that understanding pro-environmental concern and behaviour is far more complex than previously thought”, since it is deduced that “environmental outcomes that are a result of these influences undoubtedly are determined by combinations of the 18 categories”.

A high level of the psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behavior or otherwise increased environmental concern does not necessarily lead to actual expression of such behavior. This phenomenon is often referred to as the environmental concern–behavior gap [75]. A list of barriers that preclude the smooth transition to behavior was presented in the analytical framework proposed by Kollmuss and Agyeman [72], with the one related to old behavioral patterns being more prominent. In a later work [76], a series of seven categories of psychological barriers (characteristically named “dragons of inaction”) were presented in order to provide an explanation for the environmental concern-behavior gap. These seven general psychological barriers are manifested in up to almost 30 different ways. Reference is made to the existence of structural barriers (for climate-averse infrastructure), which are, however, mostly out of the control of the individual. Removing structural barriers wherever possible is important, but “this is unlikely to be sufficient” for achieving pro-environmental behavior if the psychological barriers are not overcome. Research in the field has been recently enriched [75] via a study that aims to explore how psychological barriers may be dependent on the cultural framework and therefore “reflect not only individuals’ personal views in the environmental domain but also some domain-general psychological orientations that are rooted in the worldviews and meaning systems in a culture”. The researchers examined data from 32 countries to find that the concern-behavior link was enhanced “in societies with higher levels of individualism and looseness” and less pronounced “in societies characterized by higher levels of distrust, belief in external control, and present orientation”.

Moving on to the presentation of representative empirical research findings regarding the relationships between knowledge, attitudes and behavior regarding sustainability, we note that several publications provide evidence for positive pairwise correlations between the three constructs [20,25,27,30,46,53,59]. In several cases, the knowledge–behavior correlation was found to be weaker relative to the other two pairs (i.e., knowledge–attitudes and attitudes–behavior) [20,27,46,59].

Studies that involved the conduct of linear regression have provided evidence that both knowledge and attitudes predict behavior, but up to a rather limited degree [19,25,27]. Heeren and colleagues [77] showed that knowledge had a weak but statistically significant correlation with behavior, which, however, “disappeared” when controlling for TPB variables, namely attitudes, norms and perceived behavioral control.

Ovais [55] provided evidence that sustainability knowledge impacts sustainability behavior, although to a lesser degree relative to the influence of sustainability attitude. Leal and colleagues [56] found that both sustainability knowledge and attitudes have statistically significant positive effects on sustainability behavior. In addition, they provided evidence that sustainability knowledge also has an indirect effect on sustainability behavior via sustainability attitudes.

Finally, there are a few studies in which either negative or no correlations are observed. Thus, Nousheen and Tabassum [51] failed to identify a statistically significant influence of sustainability attitudes on sustainability behavior. Also, Gong and colleagues [58] detected a negative correlation between knowledge and behavior, as well as between knowledge and attitudes, and only a positive correlation between attitudes and behavior.

2.4. The Effect of Gender on Sustainability Perceptions

Gender has been identified as one of the numerous factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behavior [74]. Gender differences are often explained via the use of socialization theory [78,79] according to which “children are continually influenced by their surroundings” and therefore end up being socialized into different identities. Relevant characteristic empirical research has provided evidence that “compared to males, females had higher levels of socialization to be other oriented and socially responsible” [80]. There is numerous research evidence (Ref. [74] and references therein) that in most cases “women tend to report stronger environmental attitudes, concern and behaviours than men” while men seem to be “more knowledgeable” about environmental problems compared to women.

Subsequently, reference will be made to representative recent research findings (gathered from a total of 20 publications) concerning the effect of gender on perceptions regarding specifically sustainability/sustainable development.

In a set of seven publications, evidence is provided for increased levels (in different measures of sustainability perceptions) in females relative to males. More specifically, Tuncer [15] found a statistically significant difference between Turkish female and male university students’ perception of sustainable development in favor of the females. In a study among Dutch households, it was shown that females played a more significant role relative to males for establishing positive values towards both people and planet, in terms of social welfare and reducing carbon emissions [33]. In a study among Lithuanian adults [32], females achieved higher scores than males in all three domains of sustainable behavior (environmental, social and economic). Female undergraduate students in the Republic of Korea exhibited higher levels of sustainability consciousness relative to their male counterparts [50]. In a transnational study among undergraduate students, females surpassed males in sustainability knowledge, attitudes and behavior [56]. In a study involving pre-service English teachers in China, females reported more positive attitudes towards sustainability relative to males [59]. Finally, in a study aiming to measure consumer perceptions towards sustainability in four different countries (Estonia, France, Italy and Sweden), it was found that “the lowest agreement with different sustainability dimensions was more likely among men” [35].

In a second set comprising six publications, research evidence for mixed results regarding sustainability perceptions, with either females exceeding males or with similarity between the two genders, is reported. More specifically, in a nationwide Swedish study, Olsson & Gericke [81] probed secondary school students’ (6th, 9th and 12th graders) sustainability consciousness to find out that girls overall reported higher mean scores relative to boys with only some exceptions for the 6th graders in the economic dimension and for the 9th graders in schools without an ESD-certification, where girls and boys were almost equal. In a study among university students in the United Arab Emirates regarding SD perceptions, females exceeded males in knowledge, while no gender differences were observed regarding attitudes and behavior [18]. Exploring the sustainability consciousness of secondary school students in Taiwan showed a significant gender effect in favor of the girls among 9th graders and for sustainability behaviors among 12th graders. On the other hand, there were negligible gender differences for 6th graders and for sustainability knowledge and attitudes among 12th graders [45]. In a study involving vocational business students in China, female students were found to exceed males in the environmental and economic attitudes as well as in social behavior, while no gender differences were observed in the remaining dimensions of sustainability consciousness [64]. In another study also involving university students (Spain), females displayed overall higher levels of sustainability knowingness and attitudes compared to males, while non-significant gender differences were observed for sustainability behavior [53]. Finally, in a study probing sustainability consciousness among nursing students in three universities in Egypt, no significant difference was observed between males and females in two universities, and in one university, females surpassed males [66].

In a third set comprising three publications, results reporting only similarity between genders are reported. This is the case for university students’ attitudes towards sustainability in Malaysia [24], for primary and secondary students’ knowingness, attitudes and behavior regarding SD in China [30], and for Spanish university students’ awareness of sustainable development goals and sustainability literacy [23].

In a fourth set comprising two publications, mixed results with females exceeding or lagging behind males or with gender similarity are reported. More specifically, in a study measuring sustainability knowledge, attitudes and behaviors of both university students and the general public [19], the following findings are reported: among university students females exceeded males in sustainability attitudes and behaviors but lagged behind them in sustainability knowledge; in the general public, no statistically significant differences were observed between the two genders for attitudes and behaviors, while males exceeded females in knowledge, as also observed in the group of the university students. Finally, in another study involving university students in Taiwan [22], females exceeded males in the behavioral dimension, the opposite trend was noticed for the cognitive dimension, while no gender differences were detected in the socio-emotional dimension of sustainability.

Finally, in one publication, mixed results reporting either females exceeding males or the opposite are reported [54], and in another one [46], evidence is provided for either no gender differences or for males exceeding females. The first study [54] refers to adolescents (18–19 y) in Taiwan and Sweden and reports higher means for females in all three sustainability constructs (knowingness, attitudes and behavior) in both countries, with the exception of the opposite trend for knowingness in Taiwan. In the other study [46], which involved measurement of sustainability knowingness, attitudes and behavior of Spanish pre-service teachers, the few gender differences that were observed concerned males exceeding females in the economic aspect of sustainability behavior.

From the above, it may be deduced that most publications corroborate the trend for females surpassing males in different measures of sustainability perceptions. However, there is also some evidence for either non-significant gender differences or even for cases where females lag behind males in certain measures.

3. Methods

In this section, reference will be made to the processes followed with regard to participant selection and instrument adaptation to the Greek language and cultural context.

3.1. Participants

The participants in the study were accessed among in-service civil servants in the Greek public sector, who attended obligatory online lifelong training short-term (typically one weeklong) programs organized by the Greek state. Typically, the attendees were asked to complete the online questionnaire (link in the Google Form) by the seminar organizer at the beginning of the formal training session. These seminars are intended for the whole pool of in-service civil servants, irrespective of gender, age, educational background, educational level (high school graduates up to Ph.D. holders), geography or position within their organization. Their participation was anonymous and voluntary. The response rate was very high (>95%) as expected from the mode of access, a fact which also indicates the existence of minimal self-selection bias. The sample exhibited rich diversity with respect to age, educational background and residence. The gender distribution, which is the variable of interest in the present study, was 310 and 320 female and male participants, respectively, with one participant not reporting any gender.

3.2. Instrument

The long version of the Sustainability Consciousness Questionnaire (SCQ-L), consisting of 50 items and originally available in English [11], was the basis for its translation into Greek.

Before starting the translation process, item B13 of the original instrument was modified as follows: the original wording “I work on committees (e.g., the student council, my class committee, the cafeteria committee) at my school” was revised to “I work on different committees (e.g., at my work, in my community, etc.).” This change was deemed necessary because the Greek version of the instrument was intended for adults rather than students, as was the case with SCQ-L.

The forward translation (English to Greek) was carried out by a team of three translators, who are also the authors of this publication. Each translator worked independently to create three initial versions of the Greek SCQ (SCQ-GR), which were later reviewed collectively. During this review process, the translators compared their versions, resolved conflicts or discrepancies, and reached a consensus on the most accurate translation of all items. Afterwards, the SCQ-GR instrument was examined by an expert review panel of three academic staff members originating from the two higher education institutions with which the authors are affiliated. The comments provided by the experts were examined in collaboration with the translation team in order to be incorporated into the questionnaire. Subsequently, the instrument was administered to a team of five civil servants for pilot testing. The above-mentioned rewording of item B13 of the original SCQ-L instrument was shown to possess equivalent meaning in SCQ-GR during pilot testing as well as after the back translation. The few additional points that emerged after the interaction of the pilot participants with the translation team, as well as the expert panel, were taken into account in order to obtain an even more refined version of SCQ-GR. Finally, a professional translator, fluent in both Greek and English (Greek native), performed the back translation (Greek to English). The back-translated version was assessed by the team that had performed the forward translation in order to ensure that it matched as accurately as possible the original (English) instrument.

A five-point Likert scale (1–5) was used in order to examine the participants’ agreement with each of the 50 items of SCQ-GR, with rating “1” corresponding to “Strongly disagree” and “5” to “Strongly agree”. In particular, for the 19 items related to knowingness (K1 to K19 in the original instrument), an additional “Don’t know” option (which subsequently corresponded to a numerical score equal to “0”) was provided. This option was deemed necessary in order to account for the possibility of a complete lack of knowledge by the participants, a procedure which was also adopted in a recent application of the SCQ instrument in China [58]. No missing data were identified in the filled questionnaires. Besides the 50 items, the instrument contained a series of questions aiming at providing demographic information related to different variables such as gender, age, educational level and residence.

The finalized Greek version of SCQ-L (SCQ-GR, whose items are referred to as Q1–Q50) (see Appendix D) was distributed electronically and completed anonymously by adults working in the Greek public sector. A total of 631 complete questionnaires were collected between October and December 2021. The conduct of this research was approved by the ethics committee of the higher education institution with which the corresponding author is affiliated (Reference No 908/26-03-2024). In addition, permission was requested and granted by the authors who originally developed the scale in order to use it in the Greek population.

Statistical analyses of the data (including both descriptive and inferential statistics) were conducted via the SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics v. 26) or the structural equation modeling software AMOS (IBM SPSS AMOS v. 30). The validity and reliability of the collected data were examined via exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. The conduct of EFA is a required step in cases where an instrument has not been created by adhering to the framework of an established psychological theory.

4. Results

Initially, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted in order to identify specific factors (components) underlying the instrument items. Subsequently, the hypothetical measurement model derived from EFA was tested via confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

4.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

EFA with an oblique rotation (promax) in order to allow for correlation between factors and by using the principal components method was employed. EFA was conducted in a sample containing half of the participants of the whole sample, namely 315 participants, of whom 146 were females, and 169 were males. This sample was produced via the random case selection of the SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics v. 26). The results of EFA are subsequently presented. At this point, we emphasize that the terms factor and component are used interchangeably throughout the text.

The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) statistical measure resulted equal to 0.968, which is well above the lowest acceptable limit of 0.50 [82], indicating the sampling adequacy for the analysis. A sample size of at least 300 cases is overall considered adequate as an empirical “rule of thumb” (Ref. [82] and references therein). The item communalities range between 0.452 and 0.828, with the large majority (43 out of 50 items) exhibiting values above 0.6. The elevated communality values provide additional evidence for the adequacy of the sample size (Ref. [82] and references therein).

Bartlett’s test of sphericity was also shown to be statistically significant (p < 0.001), thus indicating the appropriateness of the factor model for the specific data set.

EFA with promax rotation resulted in four components with eigenvalues larger than 1 (Kaiser’s criterion), with the four-component solution being confirmed by the scree-plot as well. The four-factor structure is additionally supported via Velicer’s Minimum Average Partial (MAP) test [83,84], where the smallest average squared parallel correlation corresponding to the fourth highest eigenvalue results in 0.0092. The pattern matrix resulting from the promax rotation, with the corresponding factor loadings of all 50 items of SCQ-GR, is provided in Table 1. The four-component structure accounts for 69.41% of the total variance in the data. With regard to reliability, the value of Cronbach’s α is equal to 0.971, indicating excellent overall scale reliability [82] with all Cronbach’s α values for each separate component also being quite large (>0.800), as it will be reported below. Finally, we point out that in the first column of Table 1, the item numbers as reported in the original instrument [11] are shown in parentheses.

Table 1.

Pattern matrix of SCQ-GR (Promax rotation with Kaiser Normalization) with factor loadings * shown in descending order for each extracted component.

Based on the results shown in Table 1 and after examination of the content of the items that comprise each component, we may reach the following assignments regarding the study of adult perceptions (for the case of civil servants) regarding sustainable development via the SCQ-GR instrument.

- (a)

- Component 1: This component has the highest eigenvalue (=25.619) and accounts for 51.24% of the total variance. It is characterized by a Cronbach’s α value equal to 0.976. As seen in Table 1, there exist 24 items in total that load in this component with factor loadings of sizable value (>0.3). Twelve items (namely Q20–Q22 and Q24–Q32) refer to attitudes, and twelve (namely Q34–Q40, Q43–Q45, Q47 and Q50) refer to behavior toward SD (based on the structure of the original instrument SCQ-L). Among the twelve behavior-related items, seven (namely Q34–Q37, Q44, Q47 and Q50) mostly pertain to behaviors with a high level of social acceptance/desirability [e.g., I show the same respect to men and women, boys and girls (Item Q50)] and behavioral choices/habits [e.g., I recycle as much as I can (Item Q36)] and they possess sizable loadings (>0.3) solely in Component 1. From the remaining five behavior-related items, four items—namely Q39, Q40, Q43 and Q45—present sizable loadings also in Component 3. These items are differentiated from the group of seven mentioned above, since they refer to behaviors which provide evidence for active involvement in social [e.g., I do things which help poor people (Item Q39)] or environmental issues [e.g., I pick up rubbish when I see it out in the countryside or in public places (Item Q40)]. This is the main characteristic of the items that comprise Component 3, as it is noted below. Therefore, the content of these four items leads us to assign them to Component 3. Finally, one behavior-related item (Q38—I often make lifestyle choices which are not good for my health) loads also in Component 4, and it does so with a much higher loading value. This item, worded negatively, possesses a common characteristic with the rest of the items comprising Component 4 as it expresses the notion of detachment from the notion of sustainability. The above arguments justify its assignment to Component 4.

Considering the above reasoning, it is concluded that Component 1 comprises a total of 19 items, which refer either to attitudes (12) or behaviors (7) toward SD. Therefore, this component may be described via the title “Attitudes and Behaviors regarding SD” (AB).

Finally, we note that, based on the assignments of the original instrument, all three dimensions of SD are represented in these 19 items. More specifically, five items are related to “Environment” (Q24, Q27 and Q34–Q36), nine with “Society” (Q20–Q21, Q28–Q30, Q32, Q37, Q47 and Q50) and five with “Economy” (Q22, Q25–Q26, Q31 and Q44).

The documented inclusion of both attitude and behavior-related items in the same factor/component is not unexpected based on the close relationships between the two constructs predicted in different analytical frameworks [39,73], and it will be further explored in Section 5.

- (b)

- Component 2: It presents the second-highest eigenvalue (=4.877) and accounts for 9.75% of the total variance. It is characterized by a Cronbach’s α value equal to 0.971. As seen in Table 1, there exist 19 items in total that load in this component with factor loadings of sizable value (>0.3). All items except one (namely Q4—Preserving nature is not necessary for sustainable development) possess sizable loadings only in this component. With regard to item Q4, we note that—in similarity with the case of item Q38 discussed above—it shares the same characteristics with the group of items comprising Component 4, as it is worded negatively and expresses detachment from the notion of sustainability. Therefore, item Q4 is assigned to Component 4.

The remaining 18 items which comprise Component 2 include all three dimensions of SD, namely “Environment” (five items—namely Q3, Q6, Q12, Q16 and Q19), “Society” (eight items—Q2, Q5, Q7–Q10, Q13 and Q18) and “Economy” (five items—Q1, Q11, Q14–Q15 and Q17). In addition, they are all related to the construct referred to as “knowingness” in the original instrument.

As pointed out in Section 2 of the current work, the term “knowledge” is mostly linked to facts that may or may not be true, whereas “knowingness” refers to what the participants perceive as important for accomplishing SD and entails both a cognitive and an affective component [11,40]. As noted in Gericke et al. [11], the term “knowingness” is quite similar to Pajares’s definition of the construct “belief”, which refers to what an individual judges as being true [85]. Based on the above, we decided to adopt the title “Beliefs regarding SD” (BEL) as most suitable for the description of the content of this component.

- (c)

- Component 3: It has the third highest eigenvalue (=2.809) and accounts for 5.62% of the total variance. It is characterized by a Cronbach’s α value equal to 0.912. Taking into account the argumentation deployed in the above presentation of Component 1, we conclude that it consists of eight items (namely Q39–Q40, Q42–Q43, Q45–Q46 and Q48–Q49) with all referring to behavior and with representation of all three dimensions of SD (“Environment”—3 items, “Society”—2 items and “Economy”—3 items). The items of this component pertain to behaviors that are more closely associated with activism in the socioeconomic or environmental domains [e.g., I pick up rubbish when I see it out in the countryside or in public places (Item Q40), I support an aid organization or environmental group (Item Q48), I often purchase second-hand goods over the internet or in a shop (Item Q42)]. Therefore, it was decided that a suitable title for describing the content of the items comprising this component is “Social and Environmental Activism for SD” (SEA).

- (d)

- Component 4: It possesses the fourth-highest eigenvalue (=1.399) and accounts for 2.80% of the total variance. It is characterized by a Cronbach’s α value equal to 0.833. Taking into account the argumentation deployed in the above presentation of Components 1 and 2, we conclude that it consists of five items (namely Q4, Q23, Q33, Q38 and Q41). They are related to the environmental and social dimensions of SD via four and one items, respectively. All five items are phrased in a negative manner toward SD [e.g., Preserving nature is not necessary for sustainable development (Item Q4), I think that it is OK that each one of us uses as much water as we want (Item Q33) and I don’t think about how my actions may damage the natural environment (Item Q41)] expressing detachment from the notion of sustainability. However, during the setup of the data set, the ratings they received were inverted (i.e., a rating of “1” was converted to “5”). In this way, the scores concerning these items refer to a notion opposite to detachment, and, therefore, it was decided that a suitable title for describing their content is “Attachment to SD” (ASD). This component resembles the notion of environmental concern and, as it will be discussed below (Section 5), it is mostly relevant to the affective dimension of the framework presented by Sánchez and Lafuente [39].

The correlations between the above-mentioned four components of sustainability consciousness as derived from the promax rotation are shown in Table 2. The fact that several correlations are well above zero provides support for the need to conduct EFA via an oblique rotation. Interestingly, apart from Component 4 which shows only one weak correlation with Component 3 (=−0.328) and very small correlations with Components 1 and 2, all other three SC components (1, 2 and 3) show non-zero pairwise correlations which are either weak (=0.388 for the 2–3 pair), moderate (=0.561 for the 1–3 pair) or strong (=0.695 for the 1–2 pair). As a robustness check, the rotated components matrix of SCQ-GR derived via the orthogonal (varimax) rotation is also provided (Appendix A). The varimax rotation results practically in the same four-factor structure as the promax rotation. Interestingly, as shown in the matrix of Appendix A, the majority of the items assigned to components 1, 2 and 3 display significant loadings (>0.3) to two (and in some cases three) components simultaneously. In addition, the items assigned to Component 4 in the same matrix (Appendix A) display very few significant loadings (>0.3) to items of the first three components. These characteristics of the loading pattern derived from the varimax rotation are in accordance with the elevated pairwise correlations between components 1, 2 and 3 and their much weaker correlations with Component 4, evidenced in the promax rotation (Table 2). The complete pattern matrix of SCQ-GR derived from the promax rotation, as well as the complete rotated matrix derived from the varimax rotation, are available as Supplementary Materials.

Table 2.

Component correlation matrix for SCQ-GR obtained from promax rotation.

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The analysis was carried out via maximum likelihood (ML) estimation. CFA was conducted on the whole sample of 631 participants. The model estimated as a result of CFA may be evaluated for its quality via the determination of its ability to explain the empirical data. This ability is judged via the examination of a series of fit indices, which fall into three main categories: comparative fit indices, absolute fit indices and parsimony correction indices.

The indices of the first category, namely the comparative fit indices, provide an assessment of how well a given model solution aligns with a baseline model solution [86,87]. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI), together with the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), are two commonly used indices belonging to the comparative fit category. CFI and TLI take values between 0 and 1, and both have a recommended cutoff value of >0.90 for an acceptable fit, with the best values being above 0.95 [88].

The indices of the second category, namely the absolute fit indices, evaluate the goodness-of-fit of the model relative to the null hypothesis that the data fit the model perfectly [86,87]. The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) is a fit index belonging to the absolute fit category and has the advantage that it is not dependent on sample size. SRMR has a recommended cutoff value (upper limit) close to 0.08 for an acceptable fit [88].

Finally, the indices of the third category, namely the parsimony correction indices, pose a penalty for poor model simplicity (inclusion of too many parameters) [86,87]. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) is a commonly employed fit index of the parsimony correction category, with a recommended cutoff value (upper limit) close to 0.06 for fit acceptability [88].

It has been noted that, as there may exist confounding situations in which the interpretation of fit indices is not straightforward, “it is up to the researcher to provide as much evidence as possible to support the acceptability of a proposed factor model” [89]. In corroboration, it has been pointed out that judgment of the adequacy of a model “rests squarely on the shoulders of the researcher” [87]. It is therefore not unusual that a CFA model is deemed acceptable even in cases where the values of the examined fit indices are slightly below (or above) the recommended highest (or lowest) limits.

In the case of SCQ-GR, in the initial factor structure used for conducting the CFA, we considered the existence of the four components identified via the EFA (denoted Comp1, Comp2, Comp3 and Comp4) and allowed for the existence of pairwise correlations between all of them, based on the evidence provided from the promax rotation (Table 2). The initial estimates after running the CFA calculation gave rise to quite large pairwise correlations between Components 1, 2 and 3 as follows: 0.655 (Comp2 ↔ Comp3), 0.845 (Comp1 ↔ Comp3) and 0.797 (Comp1 ↔ Comp2). These three correlations correspond to covariances of similar strength, which are all statistically significant relative to zero (p < 0.001). On the other hand, the correlations of Component 4 with the other three components were less strong, a fact which is in accordance with the evidence provided from EFA (Table 2), and more specifically as follows: −0.357 (Comp3 ↔ Comp4), −0.099 (Comp1 ↔ Comp4) and 0.043 (Comp2 ↔ Comp4). The very small value of the Comp2↔Comp4 correlation corresponded to a similarly low covariance (=0.053), which in addition was statistically non-significant relative to zero (p = 0.338). Therefore, it was decided to continue the CFA via a model in which all pairwise correlations between the four components are preserved, except for the one between Comp2 and Comp4.

In the next phase, the CFA calculation was run in this updated factor structure (i.e., the one where the Comp2—Comp4 correlation was set equal to zero), and the resulting model had the following fit indices: CFI = 0.900, TLI = 0.895, RMSEA = 0.061, SRMR = 0.068. The value of CFI equals the one that is recommended as a minimum for a good fit (=0.90). The values of the TLI are only slightly lower than the least recommended for a good fit (=0.90). The value of RMSEA is only slightly larger than the highest recommended one (=0.060). The value of SRMR is clearly within the limits (<0.08) for an acceptable fit. Taking into account the above reference on the judgment of a model’s adequacy, we conclude that the values of the four examined fit indices (CFI, TLI, RMSEA and SRMS) are compatible with a CFA model, which actually provides a quite satisfactory fit for the data.

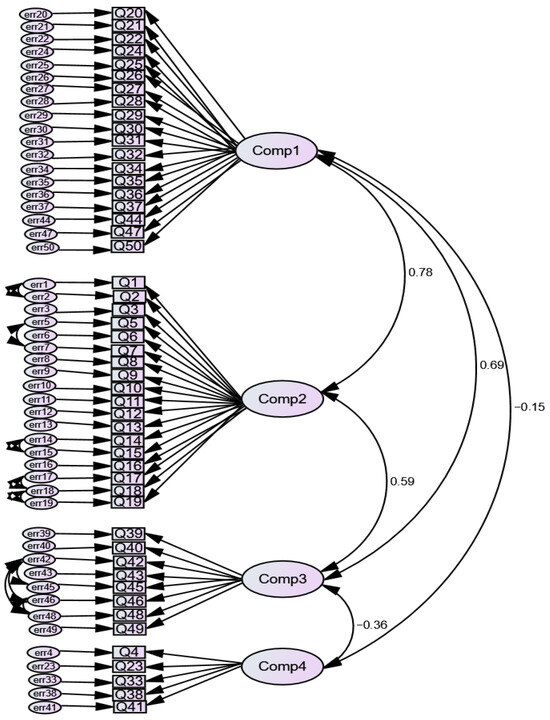

Subsequently, in order to obtain an even more satisfactory fit, we introduced the existence of error covariances via examination of the modification indices provided in the model estimates. We allowed for covariances only between errors with large modification indices [87]. The final factor structure, which resulted after the inclusion of a small number of error covariances (9 in total), is depicted in Figure 1. The error covariances for the nine item pairs are provided in Appendix C.

Figure 1.

Structure of the four-factor (component) model of SCQ-GR employed in the CFA.

The model, which resulted from the CFA calculation based on the factor structure portrayed in Figure 1, is characterized by the following fit indices: CFI = 0.914, TLI = 0.909, RMSEA = 0.057 and SRMR = 0.065. The values of these four fit indices fall well within the recommended cutoffs, and therefore, it is deduced that this final, more refined calculated model provides a good fit for the empirical data. The final values of the pairwise correlations between the four factors are also depicted in Figure 1.

The estimated standardized item loadings of all 50 items of the SCQ-GR instrument are provided in Appendix B. It may be noted that the items of all four factors (components) display sizeable loadings ranging between 0.498 (item Q42 of Comp3) and 0.876 (item Q20 of Comp1).

Based on the above-presented results obtained from CFA, it is concluded that there is strong evidence for the validity of the data provided by the SCQ-GR instrument. These data provide valuable information for adults’ perceptions regarding sustainable development (for the specific adult group referring to Greek civil servants) by probing four distinct components: attitudes and behaviors (AB—Comp1), beliefs (BEL—Comp2), social and environmental activism (SEA—Comp3) and attachment (ASD—Comp4).

4.3. Measurement Invariance Testing for Gender Comparisons

In order to be able to proceed to comparisons between different groups (for example, between genders), it is necessary to ensure that the groups to be compared share a similar measurement model as well. This is performed via a process known as measurement invariance testing, which is deployed in four consecutive steps/levels of invariance [90]: configural, metric, scalar and residual. Before engaging in the steps of measurement invariance testing, separate independent CFAs for each group are conducted, and all of them should be found to have an acceptable data-model fit. During each testing level, a homonymous model is produced, and its fit indices are examined both alone as well as in comparison with ones of the previous level.

The first testing level (configural invariance) corresponds to the configural model (Model 1). The achievement of configural invariance denotes that the general structure of items and factors is similar across groups, or in other words, that the participants of different groups perceive the factors in the same way [12,89]. Configural invariance is considered to be achieved if the values of the fit indices of the configural model are deemed acceptable [88].

The second testing level (metric/weak invariance) corresponds to the metric model (Model 2). The achievement of metric invariance supports the claims of configural invariance in addition to the fact that the strength of associations between the individual items and the latent variables (factors/components) is similar across the different groups [89]. Metric invariance is considered to be achieved if the changes in the fit indices CFI, RMSEA and SRMR of the metric model relative to the previous one (configural) are within the following limits: ΔCFI < −0.010, ΔRMSEA < 0.015 and ΔSRMR < 0.030. The case where ΔCFI ≥ −0.010 supplemented by ΔRMSEA ≥ 0.015 or ΔSRMR ≥ 0.030 would be indicative of noninvariance [91].

The third testing level (scalar/strong invariance) corresponds to the scalar model (Model 3). The achievement of scalar invariance supports the claims of the configural and metric invariances, in addition to the fact that there exist no systematic response biases across groups. If scalar invariance applies, then the comparison between factor means (as estimated from the model) of different groups is supported [89]. Scalar invariance is considered to be achieved if the changes in the fit indices CFI, RMSEA and SRMR of the scalar model relative to the previous one (metric) are within the following limits: ΔCFI < −0.010, ΔRMSEA < 0.015 and ΔSRMR < 0.010. The case where ΔCFI ≥ −0.010 supplemented by ΔRMSEA ≥ 0.015 or ΔSRMR ≥ 0.010 would be indicative of noninvariance [91].

Finally, the fourth testing level (residual/conservative/strict invariance) corresponds to the residual model (Model 4). The achievement of residual invariance supports the claims of the configural, metric, as well as scalar invariances, in addition to the fact that measurement error variances are similar across groups. If residual invariance applies, then the comparison between observed scale scores of different groups is supported [89]. Residual invariance is considered to be achieved if the changes in the fit indices CFI, RMSEA and SRMR of the residual model relative to the previous one (scalar) are within the following limits: ΔCFI < −0.010, ΔRMSEA < 0.015 and ΔSRMR < 0.010. The case where ΔCFI ≥ −0.010 supplemented by ΔRMSEA ≥ 0.015 or ΔSRMR ≥ 0.010 would be indicative of noninvariance [91]. It should be noted that the achievement of residual invariance (Model 4) is usually quite difficult, and in practice, researchers typically rely on the achievement of scalar invariance (Model 3) in order to proceed to meaningful comparisons between groups.

In order to compare the perceptions regarding SD between the two genders, we first conducted CFAs for each separate subgroup (Females N = 310 and Males N = 320). The model fit indices were the following:

- Females: CFI = 0.898, TLI = 0.892, RMSEA = 0.063, SRMR = 0.070

- Males: CFI = 0.870, TLI = 0.863, RMSEA = 0.071, SRMR = 0.069

Examination of the above fit indices shows that for both subgroups, CFI and TLI display quite satisfactory values, which are only slightly lower than the recommended lower limit (=0.90). Similarly, the RMSEA index displays a quite satisfactory value, which is only slightly higher than the recommended upper limit (=0.060). At the same time, the SRMR index has a value within the recommended limit (<0.08) in both subgroups. Taking into account the smaller sample size of the subgroups relative to the whole sample and the relevant argumentation in Section 4.2, we may conclude that the CFA model fits for the two subgroups (females, males) are deemed acceptable.

Subsequently, the results of the calculation regarding the measurement invariance testing for comparing male and female participants are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Measurement invariance testing for the SCQ-GR instrument comparing male and female participants.

As evidenced in Table 3, the values for ΔCFI, ΔRMSEA and ΔSRMR of the metric and scalar testing level models are much smaller than the limits mentioned above, thus denoting the existence of metric and scalar invariance across the two gender groups. With regard to Model 4, it is noted that ΔCFI is equal to the recommended limit (=−0.010), and, at the same time, this value is not supplemented by a large (above the recommended limits) value for either ΔRMSEA or ΔSRMR. This fact implies the existence of residual invariance as well. It is therefore fully justified to move on and make comparisons between the observed scale scores for the two genders.

4.4. Greek Civil Servants’ Perceptions About Sustainable Development: Gender Comparisons

The mean values of the four components (after converting the item scores to the 0–100 scale) regarding adult perceptions about SD as extracted from SCQ-GR are shown in Table 4 separately for each gender.

Table 4.

Gender dependence of the four components regarding Greek civil servants’ perceptions about sustainable development (Scale: 0–100).

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was shown to be significant (p < 0.05) for the data regarding all four components and for both genders, indicating deviation from the normal distribution. However, taking into account the large sample sizes for both genders, the normality requirement is less strict, thus allowing the search for statistically significant differences via the parametric t-test for independent samples. The results obtained after conducting the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test are shown as well.

As shown in Table 4, for three SC components, namely components 1, 2 and 4, female participants exhibited higher mean values relative to males, with the differences being statistically significant (p < 0.05). With regard to Component 3, the higher mean value for the male participants was not shown to be statistically significant (p > 0.05), thus indicating that the two genders exhibit statistically similar levels for this component. These statistical inferences are confirmed by both the parametric and non-parametric statistical tests for two independent samples. The calculated Cohen’s d values are closer to 0.2 (=small effect) and further away from 0.5 (=moderate effect), a fact which is indicative of a small effect size for all three observed statistically significant differences between the two genders [92].

5. Discussion

In the current work, the long version of the Sustainability Consciousness Questionnaire (SCQ-L) originally developed by Gericke and colleagues [11] was employed in order to probe the sustainability perceptions of Greek adults (from ca. 25 up to 65 years old) sampled from the body of active civil servants. Strong evidence was provided for the reliability and validity of the collected data via rigorous statistical testing, a fact that allows for a more accurate depiction of the perceptions and more extensive use of the instrument for further studies.

5.1. Validity of SCQ-GR

Starting with the validation process itself, it is noted that its successful completion often requires the omission of one or more problematic items. Thus, in the case of SCQ-L, even though the original instrument involved a total of 50 items, its final validated version [11] included 49 items since 1 item (namely Q1 in SCQ-GR or K1 in SCQ-L) had a non-significant factor loading and was omitted. A similar need appeared during the adaptation/validation of SCQ-L in the Portuguese [52], Korean [50], Pakistani [51] and Mandarin [45] languages. In fact, the final Portuguese version of SCQ-L included 46 items, the corresponding Pakistani and Mandarin versions were composed of 48 items each, while the Korean version comprises 33 items. It is therefore important to notice that the final validated Greek version of SCQ-L (referred to as SCQ-GR) includes all 50 items which are present in the original instrument since the validation process. There appeared to be no problematic items that needed to be omitted from the statistical analyses. This fact provides additional evidence for the strong validity of the data collected via SCQ-GR within the Greek cultural context and in a target group such as the civil servants, which covers a wide range of characteristics like age, education and residence (different levels of urbanization).

5.2. Factor Structure of SCQ-GR

Subsequently, the factor structure of SCQ-GR will be discussed. The statistical analyses provided a four-factor structure for the 50-item instrument, which is different from the nine-factor structure (knowingness, attitudes, and behavior, each deployed in the environmental, as well as social and economic dimensions of SD), of both the long (SCQ-L) and short (SCQ-S) versions of the original SCQ instrument [11]. Taking into account that in comparison to the original instrument, SCQ-GR refers to a different cultural context (Greece vs. Sweden) and at the same time is applied to a different target group (adults vs. adolescents), its different factor structure is not unexpected. It is, in fact, a strong indication of the absolute necessity to conduct reliability and validity testing during the use of a psychometric instrument in a different cultural setting and, in general, under circumstances that are sizably modified relative to the original ones. In accordance with this argument and similarly to the case of SCQ-GR, the Japanese version of SCQ-S was also shown not to conform to the nine-factor structure of the original instrument but to be compatible with a two-factor structure instead [48]. In the Japanese case, the following two factors were identified: sustainability knowingness/attitude and sustainability behavior. Each factor involves the items corresponding to all three dimensions of sustainability (environment, society and economy), and this is the reason they are also reported as single-level factors.

A common characteristic of all four factors that support the data collected via the SCQ-GR instrument in the current work is that each one of them comprises items that refer to at least two of the three dimensions of SD. In fact, in Components 1, 2 and 3, the environmental, social and economic aspects of SD are represented almost equivalently, and it is only Component 4 which includes items from two dimensions of SD (namely environment and society). This mingling is in accordance with different frameworks that have been developed for defining the concept of SD. As noted in the “Introduction”, the integrational perspective for approaching SD considers the interactions of the economic, social and environmental dimensions, while the holistic perspective, in addition, incorporates the temporal element in order to account for intergenerational equity as well [4]. In corroboration with these definitions of SD, researchers have pointed out the need to study and analyze SD via a systems approach so that, among other issues, the complex interconnections between the three dimensions of the concept are accounted for [3,8,9].

5.3. Factor Content of SCQ-GR