A Methodological Proposal for the Metals’ Supply Chain Risk Analysis of Investments Applied to Solar Energy Technologies in Europe

Abstract

1. Introduction

- MFA and LCA: Although detailed in tracing direct material flows, these approaches are time-intensive, bound by narrow or arbitrary system boundaries, and suffer from truncation errors and weak regionalization—thus failing to capture indirect flows and granular, country-level supply dependencies across global chains.

- Available supply risk indices: Tools like GRI and SR capture only some aspects (resource availability, recycling, governance, or supply concentration), never the whole spectrum (including circularity, regional diversity, and governance) within one cohesive methodological framework.

- Diversity and Governance Gaps: Prior frameworks rarely synthesize governance quality of supplier countries or the entropy (diversity) of supplier distribution with resource availability and circularity, leading to incomplete or regionalized policies that do not directly support European energy security policy, especially amid geopolitical interdependencies and critical mineral bottlenecks.

2. Materials and Methods

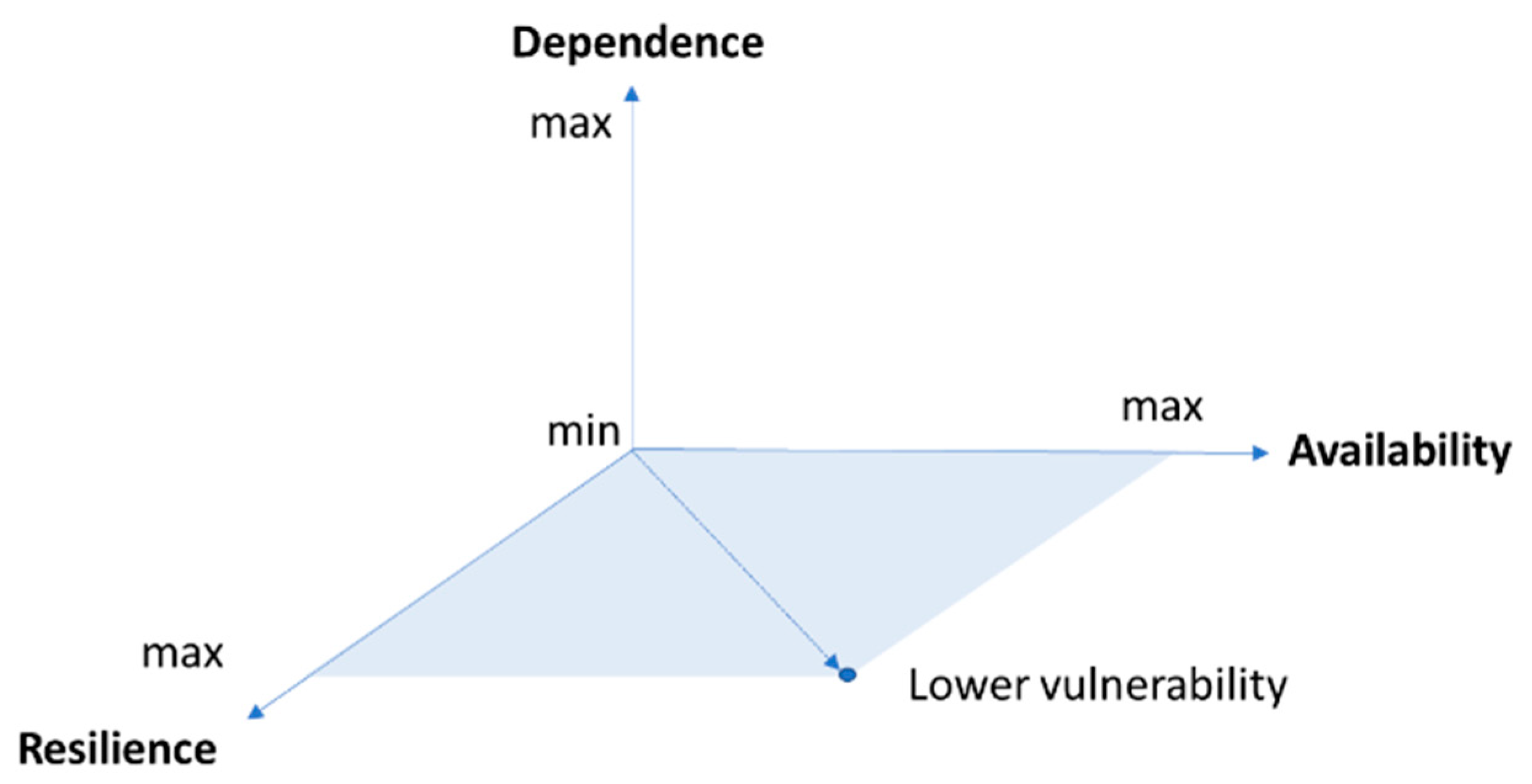

2.1. Theoretical Approach

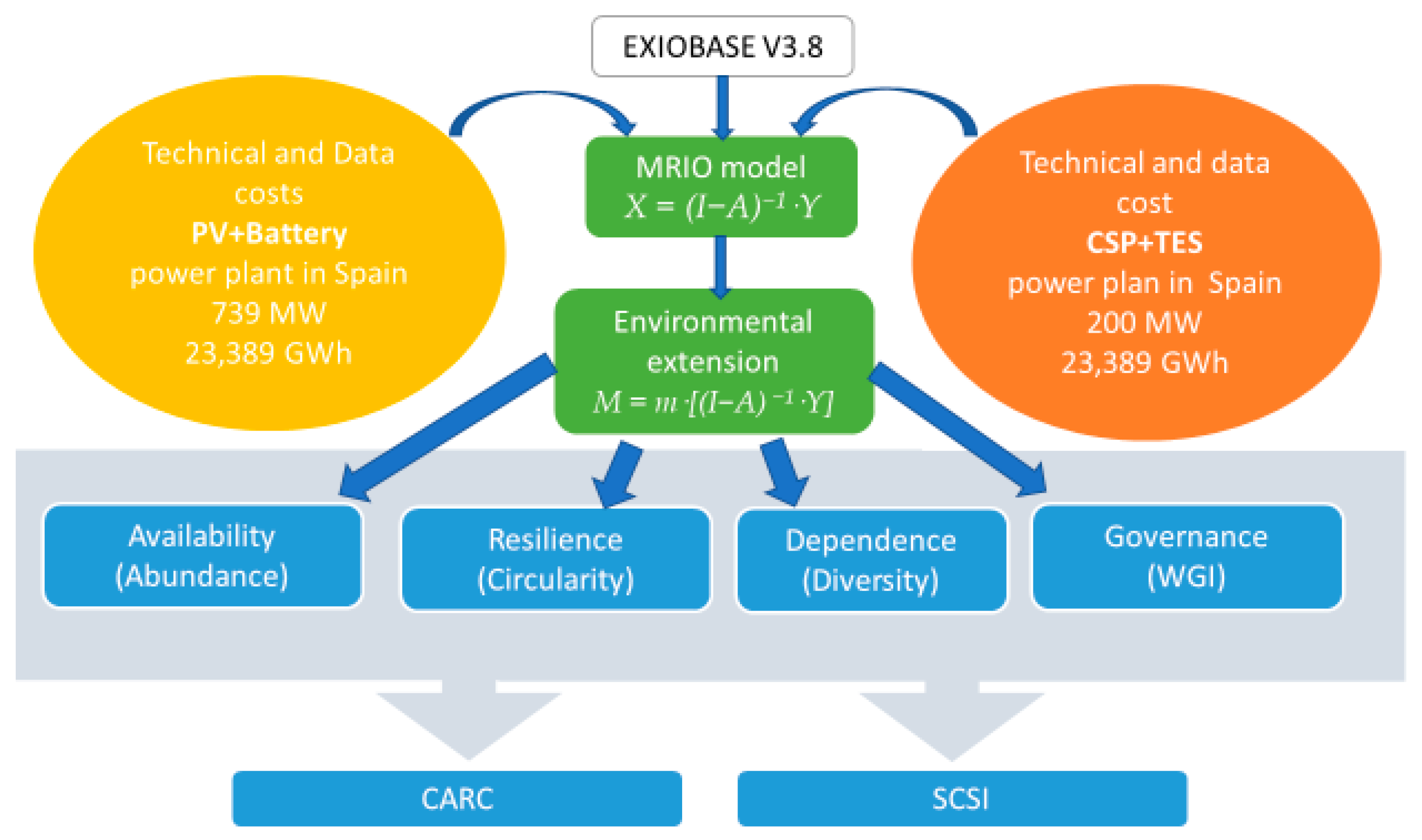

2.2. Model Proposal

2.2.1. Extended Multi-Regional Input–Output Analysis

2.2.2. Availability

2.2.3. Resilience

2.2.4. Dependence

2.2.5. Governance

2.2.6. Comparative Analysis of Individual Risk Components (CARC)

2.2.7. Analysis Combined: Supply Chain Strength Indicator (SCSI)

2.3. Case Studies

3. Results

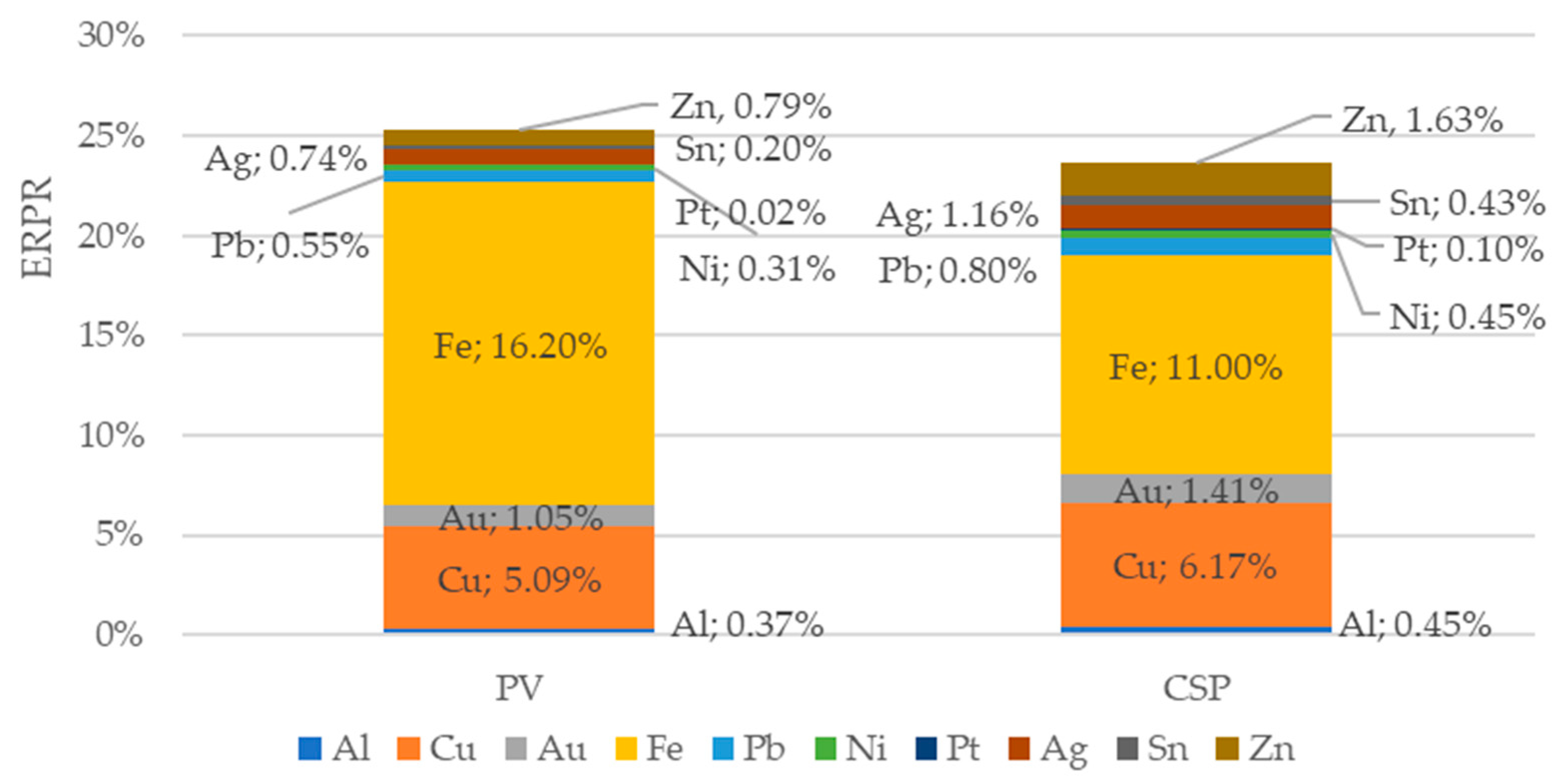

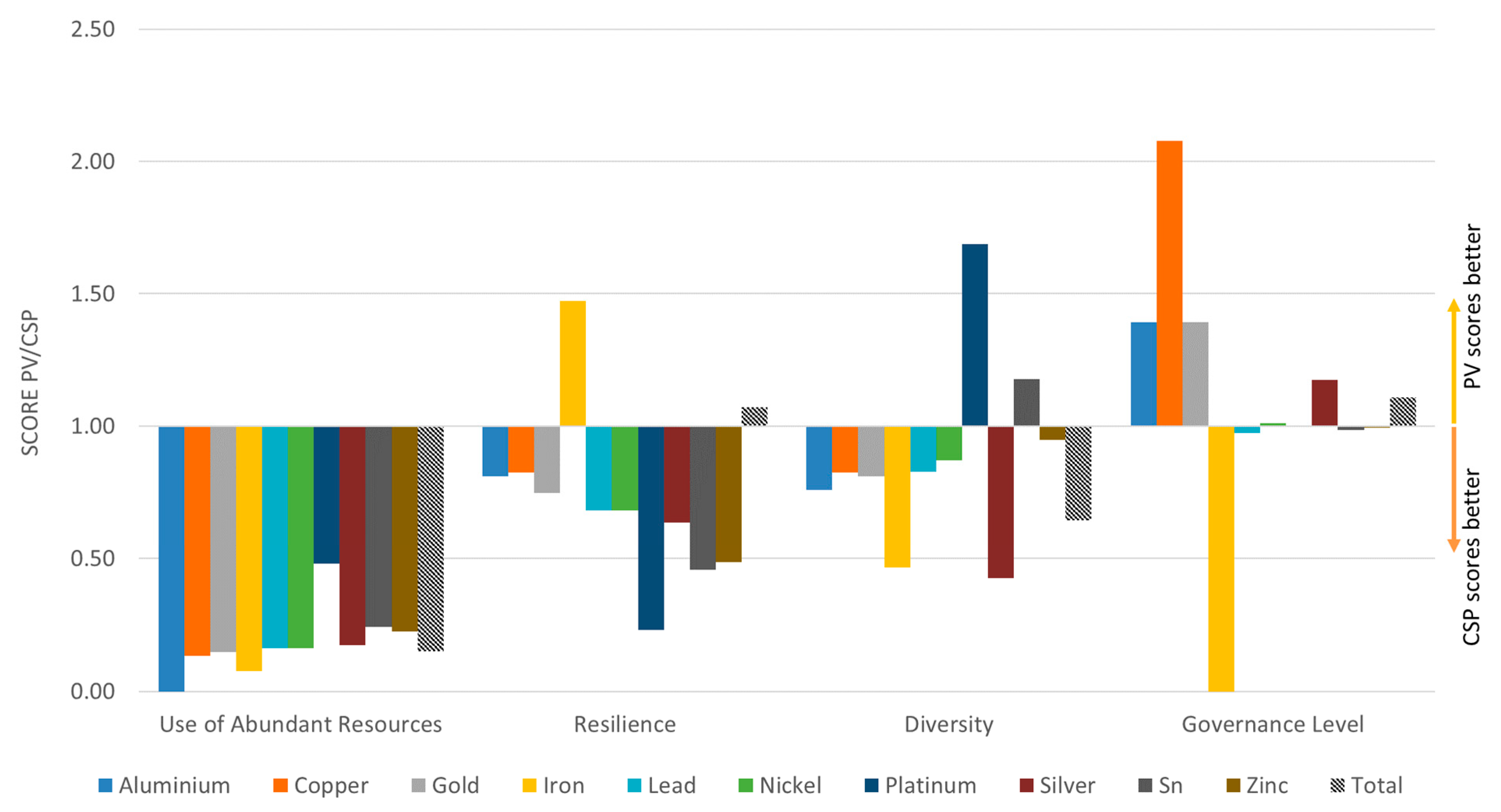

3.1. Availability: Abundance

3.2. Resilience: Circularity

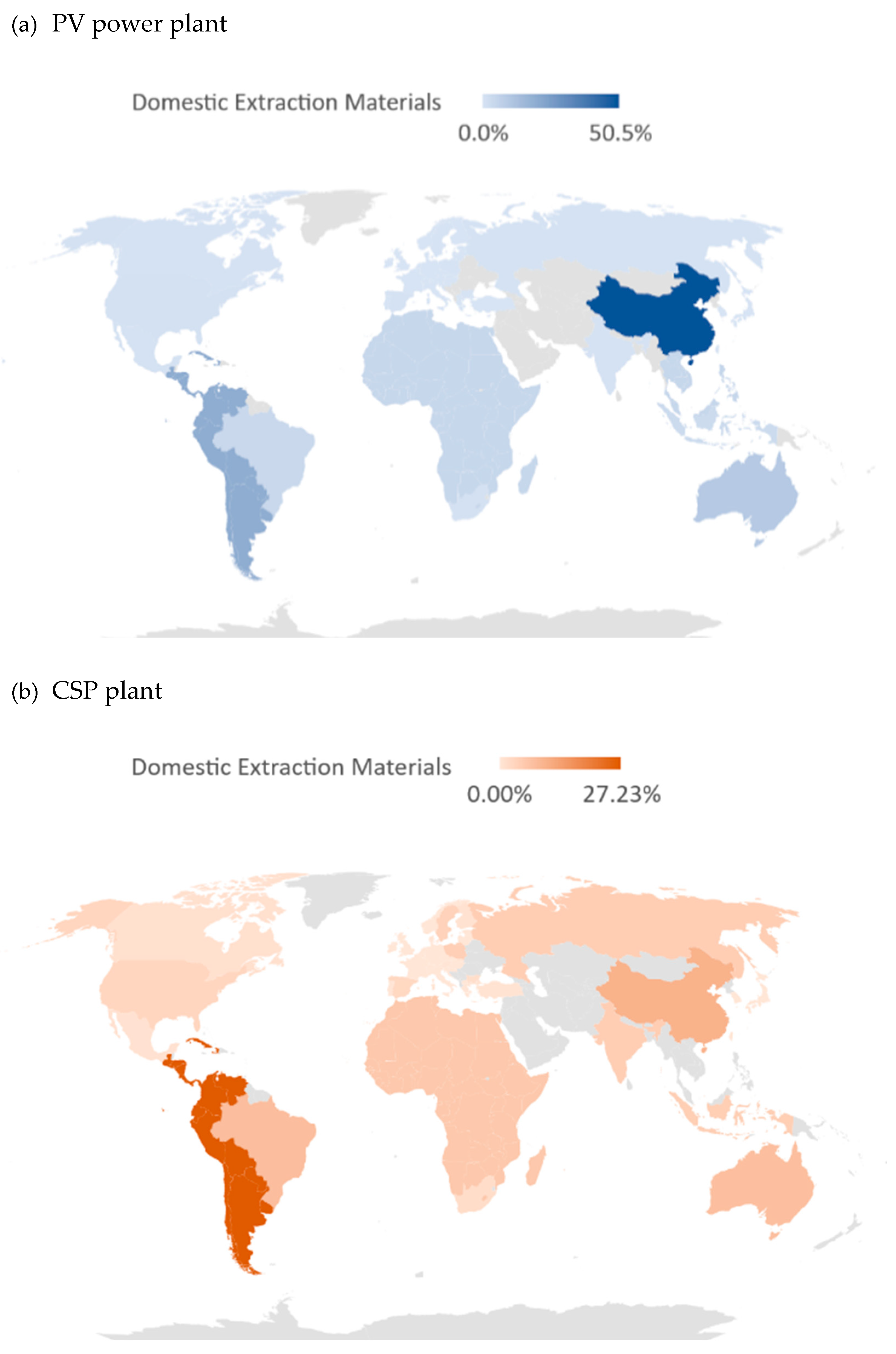

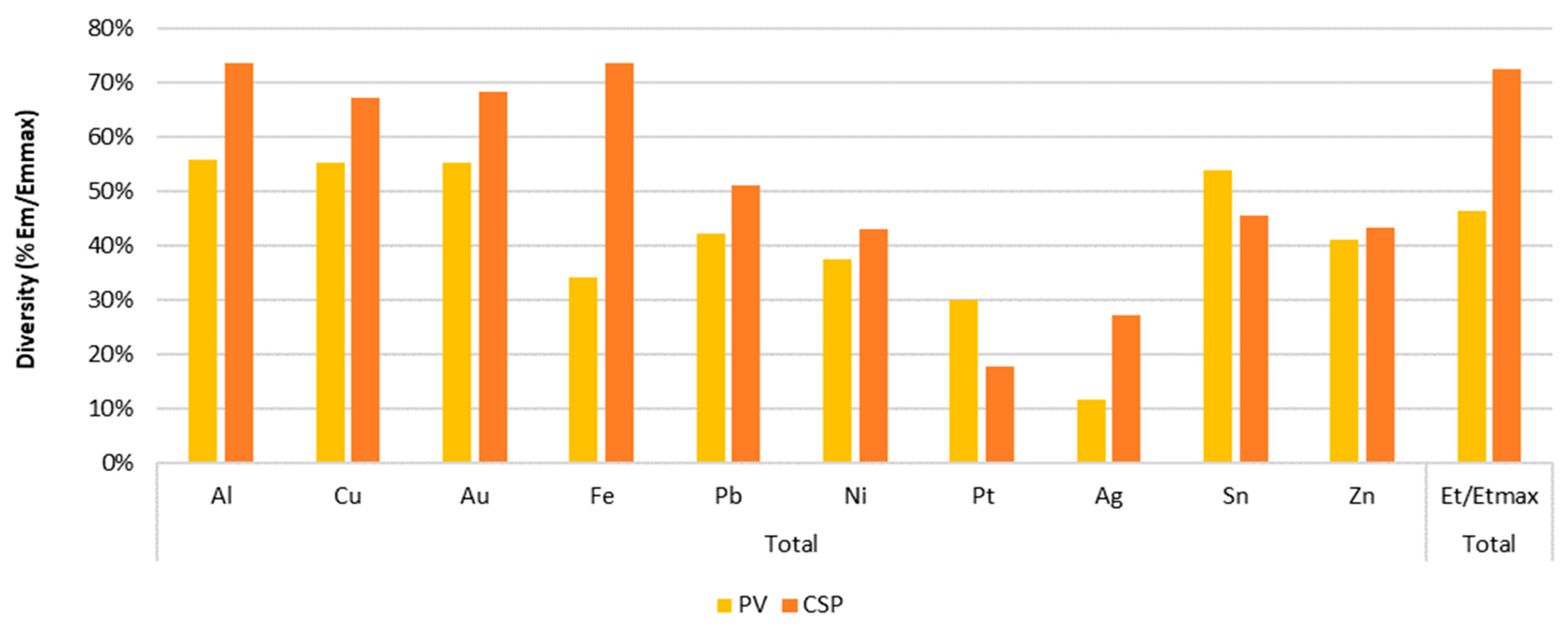

3.3. Dependence: Diversity of the Supply

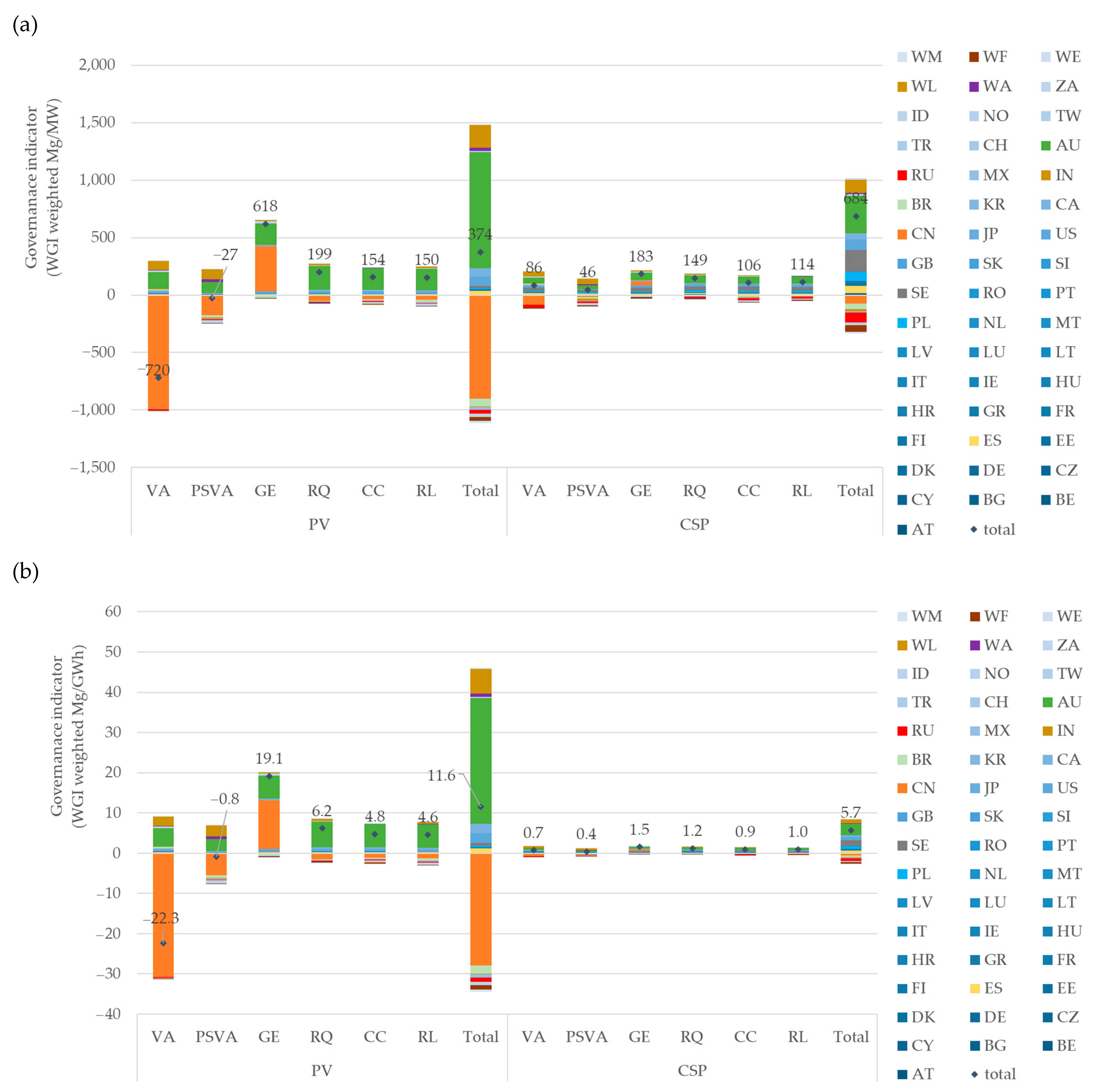

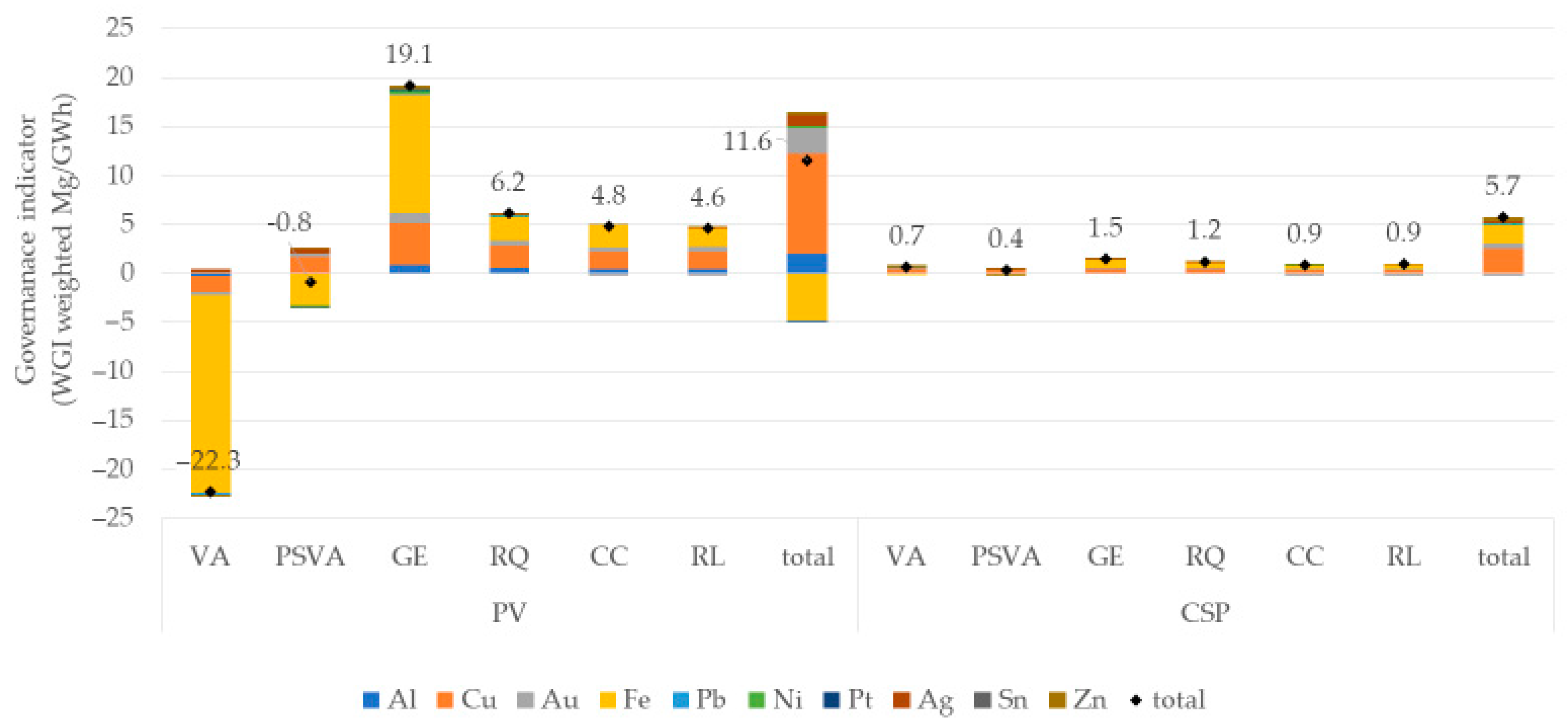

3.4. Governance: Six-Composite Indicator

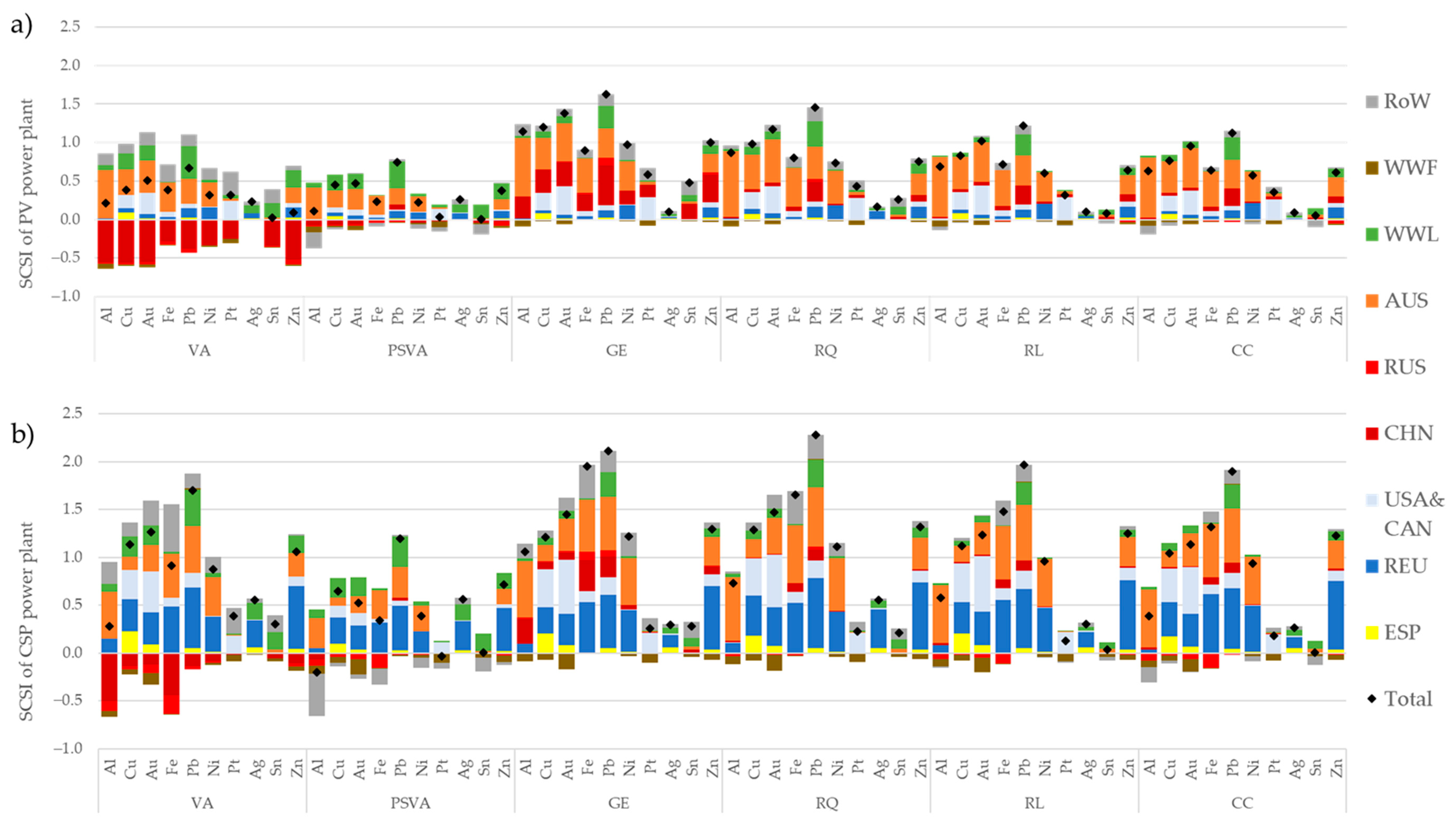

3.5. Comparative Analysis of Individual Risk Components: CARC

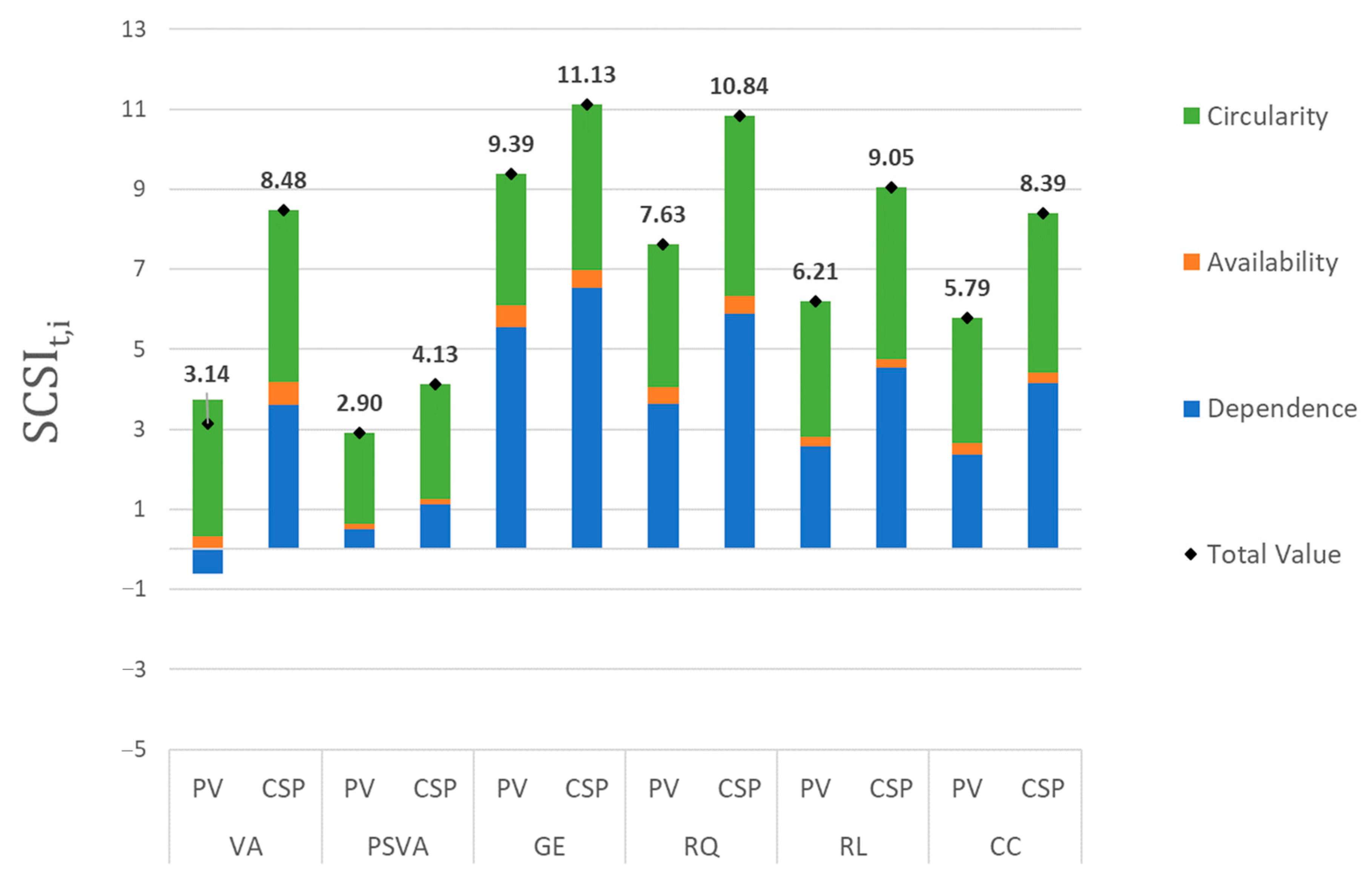

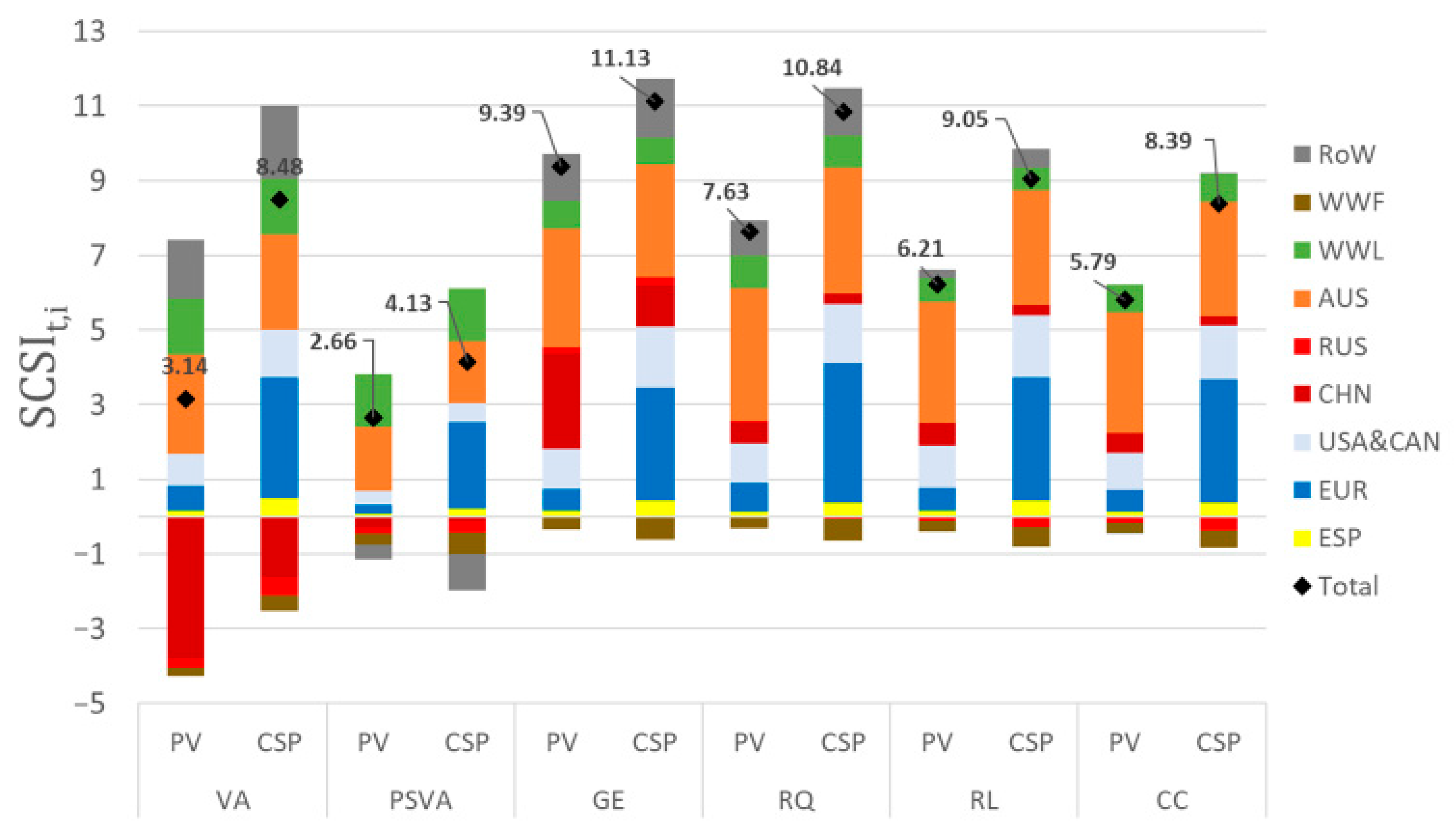

3.6. Supply Chain Strength Index: SCSI

4. Discussion

4.1. Solar Technologies Comparison

4.2. Supply Risk Analysis

4.3. Novelty Contribution, Limitations, Challenges, and Next Steps

- EMRIO-Based integration: It uses EMRIO analysis, enabling planetary system boundaries, global traceability of material extraction, and quantification of both direct and indirect (embedded) flows not reachable to classical LCA/MFA.

- Multidimensional risk framework: The proposed assessment encapsulates four core components—availability (inverse ADP), circularity (end-of-life recycling input rates), dependence (entropy-based diversity), and governance (using WGI)—reflecting the three orthogonal supply security dimensions crucial in current energy-transition policy thinking.

- Composite and actionable indices: By formulating the Comparative Analysis of Risk Components (CARC) and, more importantly, the Supply Chain Strength Index (SCSI), the manuscript offers a single, policy-relevant metric, enabling robust cross-technology and cross-scenario risk comparisons.

- Empirical validation for policy relevance: The methodology is practically tested with detailed case studies comparing CSP and PV supply chains (with storage) for Spain, offering evidence for decision support, in contrast to largely theoretical or mineral-specific case studies in the recent literature.

- Inclusion of governance and circularity: This is one of the first attempts to holistically quantify how supply risk is mitigated or exacerbated not only by material flows and reserve/production ratios, but also by governance quality and circularity—filling acknowledged gaps in both the LCA and criticality/risk literature.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| (I-A)−1 | Leontief inverse |

| A | Technical coefficients matrix based on the MRIOT |

| ADP | Abiotic depletion potential |

| Abiotic depletion potential of the metal m | |

| Ag | Silver |

| Al | Aluminum |

| Au | Gold |

| c | Countries or regions included in the MRIOT |

| CC | Control of Corruption |

| CE | Circular economy |

| CSP | Concentrated solar power |

| Cu | Copper |

| Annual production or extraction rate of resource m (kg/yr) | |

| Annual production or extraction rate of the Sb (kg/yr). | |

| Extraction rate of resource m by the country c (kg/yr) | |

| Extraction rate of resource m globally (kg/yr) | |

| Entropy of the extraction of the metal m along the supply chain | |

| End-of-life recycling input rates in Europe of the metal m | |

| Maximum value of Entropy considering the number of countries or regions c of the extraction of the metal m along the supply chain | |

| EMRIO | Extended Multi-Regional Input–Output |

| Reserve-production ratio | |

| Reserve of the reference metal m in the country c (kg) | |

| Reserve of the metal m globally (kg) | |

| Total Intra-European recycling potential rate of the assessed metals extracted as consequence of the investment | |

| Intra-European recycling potential rate of the metal m extracted as consequence of the investment | |

| EU | European Union |

| Maximum value of Entropy of the total extraction of the assessed metals along the supply chain | |

| Sum of Entropy of the extraction of assessed metals along the supply chain | |

| Fe | Iron |

| Governance index of the total extraction of each material m per governance criteria i | |

| GE | Government effectiveness |

| GRI | Global Resources Index |

| GWh | Gigawatts-hour |

| kg of Sb eq. | Kilograms of antimony equivalent |

| HHI | Herfindahl–Hirschman Index |

| i | Governance criterion (i = VA, PSVA, GE, RQ, RL, CC) |

| LCA | Life Cycle Analysis |

| m | Each metal (m = Al, Cu, Au, Fe, Pb, Ni, Pt, Ag, Sn, Zn) |

| MFA | Material Flow Analysis |

| Mass of each of the extracted metal as consequence of the investment using EMRIO | |

| Mass of each of the extracted metal in the country c as consequence of the investment using EMRIO | |

| MRIO | Multi-Regional Input–Output |

| Total of the quantified mass of extracted metal as consequence of the investment using EMRIO | |

| MW | Megawatts |

| Ni | Nickel |

| Pb | Lead |

| PSVA | Political stability and the absence of violence |

| Pt | Platinum |

| PV | Photovoltaics |

| RL | Rule of Law |

| Ultimate reserve of the reference mineral m (kg) | |

| RQ | Regulatory quality |

| Ratio Reserves-Production of the metal m | |

| Ultimate reserve of the reference mineral Sb (kg) | |

| Supply Chain Strength Indicator of the supply chain of extraction of the metal m for the indicator i | |

| Supply Chain Strength Indicator of the supply chain of extraction of the sum of assessed metals for the indicator i | |

| Sb | Antimony |

| Sn | Tin |

| SR | Supply Risk |

| VA | Voice and accountability |

| WGI | Worldwide Governance Indicators |

| Governance value of each indicator (i = VA, PSVA, GE, RQ, RL, CC) | |

| Average of the values of the governance criteria indicator i of the European countries | |

| Zn | Zinc |

Appendix A. Values of ADP, RP and EOLRIR

| Name | Sym. | ADP | RP | EOLRIR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kg Sb eq/kg | (kg m R2015/ kg m P2015) | % | ||

| Aluminum | Al | 2.54 × 10−8 | 7.68 × 107 | 12.3 1 |

| Copper | Cu | 2.13 × 10−2 | 2.66 × 105 | 16.9 1 |

| Gold | Au | 1.37 × 103 | 7.73 × 104 | 19 1 |

| Iron | Fe | 6.92 × 10−7 | 5.87 × 106 | 31.5 1 |

| Lead | Pb | 1.87 × 10−2 | 5.01 × 105 | 75 1 |

| Nickel | Ni | 8.15 × 10−4 | 4.16 × 106 | 17 1 |

| Platinum | Pt | 9.71 × 102 | 3.28 × 105 | 25.3 1 |

| Silver | Ag | 8.64 × 10 | 3.47 × 105 | 20 2 |

| Tin | Sr | 1.66 × 10−6 | 2.98 × 108 | 19 2 |

| Zinc | Zn | 2.76 × 10−3 | 8.61 × 105 | 31 1 |

Appendix B. Supporting Figures for the Analysis of Results of Diversity, Governance, and SCSI

References

- von der Leyen, U. Special Address by President von Der Leyen at the World Economic Forum 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/sk/speech_23_232 (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- OECD. Global Material Resources Outlook to 2060 Economic Drivers and Environmental Consequences; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietveld, E.; Bastein, T.; van Leeuwen, T.; Wieclawska, S.; Bonenkamp, N.; Peck, D.; Klebba, M.; Le Mouel, M.; Poitiers, N. Strengthening the Security of Supply of Products Containing Critical Raw Materials for the Green Transition and Decarbonisation; Publication for the Committee on Industry, Research and Energy (ITRE), Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies, European Parliament: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions; IEA: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Llorente-González, L.J.; Vence, X. Decoupling or “Decaffing”? The Underlying Conceptualization of Circular Economy in the European Union Monitoring Framework. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IndustriAll Europe Executive Committee. Position Paper 2021/129. Securing Sustainable Raw Materials Supply in Europe; IndustriAll Europe Executive Committee: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rangel Hernández, Á. Geopolitics of the Energy Transition: Energy Security, New Dependencies and Critical Raw Materials. Old Wine in New Bottles for the EU? Bruges Political Research Papers/Cahiers de recherche politique de Bruges No 87; Collège d’Europe: Bruges, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, W.C. Global Supply Chains in a Post-Pandemic World. Harv. Buisiness Rev. 2020, 98, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Aboagye, A.; Burkacky, O.; Mahindroo, A.; Wiseman, B. Chip Shortage: How the Semiconductor Industry Is Dealing with This Worldwide Problem|World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/02/semiconductor-chip-shortage-supply-chain/ (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Schuh, C.; Schnellbächer, W. The Semiconductor Crisis Should Change Your Long-Term Supply Chain Strategy. Available online: https://hbr.org/2022/05/the-semiconductor-crisis-should-change-your-long-term-supply-chain-strategy (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Gordon, N. How the U.S.-China Trade War Could Derail the Energy Transition | Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Emissary 2025. Available online: https://carnegieendowment.org/emissary/2025/04/us-china-trade-war-tariffs-critical-minerals-clean-energy-impacts?lang=en (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Conteduca, F.P.; Mancini, M.; Borin, A. Roaring Tariffs: The Global Impact of the 2025 US Trade War|CEPR. VoxEU Column 2025. Available online: https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/roaring-tariffs-global-impact-2025-us-trade-war (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Pham, L.; Hsu, K.C. Metals of the Future in a World in Crisis: Geopolitical Disruptions and the Cleantech Metal Industry. Energy Econ. 2025, 141, 108004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzuni, A.; Breyer, C. Definitions and Dimensions of Energy Security: A Literature Review. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Energy Environ. 2018, 7, e268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APERC. Quest for Energy Security in the 21st Century Resources and Constraints; Asia Pacific Energy Research Centre: Tokyo, Japan, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, E.M. Assessing Energy Security in a Low-Carbon Context: The Case of Electricity in the UK. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sussex, Brighton, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, J.C.; Seebregts, A.J. Long-Term Energy Services Security: What Is It and How Can It Be Measured and Valued? Energy Policy 2010, 38, 1654–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narula, K.; Reddy, B.S. A SES (Sustainable Energy Security) Index for Developing Countries. Energy 2016, 94, 326–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K. Evaluating Energy Security in the Asia Pacific: Towards a More Comprehensive Approach. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 7472–7479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Mukherjee, I. Conceptualizing and Measuring Energy Security: A Synthesized Approach. Energy 2011, 36, 5343–5355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivoda, V. Diversification of Oil Import Sources and Energy Security: A Key Strategy or an Elusive Objective? Energy Policy 2009, 37, 4615–4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherp, A.; Jewell, J. The Concept of Energy Security: Beyond the Four As. Energy Policy 2014, 75, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.E.; Blair, P.D. Input-Output Analysis: Foundations and Extensions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; ISBN 9780521517133. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, T.; Merciai, S.; Mogollón, J.M.; Tukker, A. The Role of Recycling in Alleviating Supply Chain Risk–Insights from a Stock-Flow Perspective Using a Hybrid Input-Output Database. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 185, 106474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamarra, A.R.; Lechón, Y.; Banacloche, S.; Corona, B.; de Andres, J.M. Hybrid Approaches to Quantify the Environmental Impacts of Renewable Energy Technologies: A Comparison and Methodological Proposal. SSRN Electron. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamarra, A.R.; Lechón, Y.; Escribano, G.; Lilliestam, J.; Lázaro, L.; Caldés, N. Assessing Dependence and Governance as Value Chain Risks: Natural Gas versus Concentrated Solar Power Plants in Mexico. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 93, 106708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamarra, A.R.; Banacloche, S.; Lechón, Y.; del Río, P. Assessing the Sustainability Impacts of Concentrated Solar Power Deployment in Europe in the Context of Global Value Chains. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 171, 113004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banacloche, S.; Gamarra, A.R.; Tellez, F.; Lechon, Y. Sustainability Assessment of Future CSP Cooperation Projects in Europe. Deliverable 9.1 MUSTEC Project; MUSTEC Project; Madrid, Spain. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic?documentIds=080166e5d219e2a3&appId=PPGMS (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Beylot, A.; Corrado, S.; Sala, S. Environmental Impacts of European Trade: Interpreting Results of Process-Based LCA and Environmentally Extended Input–Output Analysis towards Hotspot Identification. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 2432–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, V.; Beylot, A.; Sala, S. Environmental Impacts of Household Consumption in Europe: Comparing Process-Based LCA and Environmentally Extended Input-Output Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 240, 117966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, V.; Hidalgo, C.; Gelabert, L.; Riera, M.R.; Escamilla, M.; Mengual, E.S.; Sala, S. Consumer Footprint Basket of Products Indicator on Household Goods. 2019. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC116120 (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Hertwich, E.G.; Gibon, T.; Bouman, E.A.; Arvesen, A.; Suh, S.; Heath, G.A.; Bergesen, J.D.; Ramirez, A.; Vega, M.I.; Shi, L. Integrated Life-Cycle Assessment of Electricity-Supply Scenarios Confirms Global Environmental Benefit of Low-Carbon Technologies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 6277–6282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, E.; Gregory, J.; Field, F.; Kirchain, R. Material Availability and the Supply Chain: Risks, Effects, and Responses. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 6649–6656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adibi, N.; Lafhaj, Z.; Yehya, M.; Payet, J. Global Resource Indicator for Life Cycle Impact Assessment: Applied in Wind Turbine Case Study. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 165, 1517–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blengini, G.A.; Blagoeva, D.; Dewulf, J.; Torres de Matos, C.; Ita, V.; Vidal-Legaz, B.; Latunussa, C.E.L.; Kayam, Y.; Talens Peirò, L.; Baranzelli, C.; et al. Assessment of the Methodology for Establishing the EU List of Critical Raw Materials; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talens Peiró, L.; Martin, N.; Villalba Méndez, G.; Madrid-López, C. Integration of Raw Materials Indicators of Energy Technologies into Energy System Models. Appl. Energy 2022, 307, 118150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Brown, M.A. Competing Dimensions of Energy Security: An International Perspective. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2010, 35, 77–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabernard, L.; Pfister, S.; Hellweg, S. A New Method for Analyzing Sustainability Performance of Global Supply Chains and Its Application to Material Resources. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 684, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Koning, A.; Kleijn, R.; Huppes, G.; Sprecher, B.; van Engelen, G.; Tukker, A. Metal Supply Constraints for a Low-Carbon Economy? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 129, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merciai, S.; Schmidt, J. Methodology for the Construction of Global Multi-Regional Hybrid Supply and Use Tables for the EXIOBASE v3 Database. J. Ind. Ecol. 2018, 22, 516–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.; Sonderegger, T.; Alvarenga, R.; Bach, V.; Cimprich, A.; Dewulf, J.; Frischknecht, R.; Guinée, J.; Helbig, C.; Huppertz, T.; et al. Mineral Resources in Life Cycle Impact Assessment: Part II—Recommendations on Application-Dependent Use of Existing Methods and on Future Method Development Needs. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 798–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oers, L.; de Koning, A.; Guinee, J.B.; Huppes, G. Abiotic Resource Depletion in LCA Improving Characterisation Factors for Abiotic Resource Depletion as Recommended in the New Dutch LCA Handbook; Road and Hydraulic Engineering Institute of the Dutch Ministerie van Verkeer em Waterstraat: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Itsubo, N.; Inaba, A. LIME2—Chapter 2: Characterization and Damage Evaluation Methods; LCA-forum: Tokyo, Japan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel, H.; Hauschild, M.Z.; Alting, L. Environmental Assessment of Products: Volume 1: Methodology, Tools and Case Studies in Product Development; Springer Science & Business Media: Cham, Switzerland, 1997; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- van Oers, L.; Guinée, J.B.; Heijungs, R. Abiotic Resource Depletion Potentials (ADPs) for Elements Revisited—Updating Ultimate Reserve Estimates and Introducing Time Series for Production Data. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, S.; Linnenluecke, M.K. Circular Economy and Resilience: A Research Agenda. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 2754–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrafi, A.; Chiarini, A.; Belhadi, A.; El Baz, J.; Chaouni Benabdellah, A. Digital Technologies and Circular Economy Practices: Vital Enablers to Support Sustainable and Resilient Supply Chain Management in the Post-COVID-19 Era. TQM J. 2022, 34, 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, B.; Shen, L.; Reike, D.; Rosales Carreón, J.; Worrell, E. Towards Sustainable Development through the Circular Economy—A Review and Critical Assessment on Current Circularity Metrics. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 151, 104498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walzberg, J.; Lonca, G.; Hanes, R.J.; Eberle, A.L.; Carpenter, A.; Heath, G.A. Do We Need a New Sustainability Assessment Method for the Circular Economy? A Critical Literature Review. Front. Sustain. 2021, 1, 620047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC-DG GROW Contribution of Recycled Materials to Raw Materials Demand—End-of-Life Recycling Input Rates (EOL-RIR) (Cei_srm010). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/metadata/en/cei_srm010_esmsip2.htm (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Corsetti, G.; Lafarguette, R.; Mehl, A. ECB Working Paper Series No 2300. Fast Trading and the Virtue of Entropy: Evidence from the Foreign Exchange Market; European Central Bank: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Teza, G.; Caraglio, M.; Stella, A.L. Growth Dynamics and Complexity of National Economies in the Global Trade Network. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Többen, J.; Wiebe, K.S.; Verones, F.; Wood, R.; Moran, D.D. A Novel Maximum Entropy Approach to Hybrid Monetary-Physical Supply-Chain Modelling and Its Application to Biodiversity Impacts of Palm Oil Embodied in Consumption. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 115002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, D.; Kraay, A. The Worldwide Governance Indicators-Datasets. World Bank. Available online: www.govindicators.org (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Kaufmann, D.; Kraay, A.; Mastruzzi, M. The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues. Hague J. Rule Law 2011, 3, 220–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X. Supply Chain Risks of Critical Metals: Sources, Propagation, and Responses. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 957884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, N.A.; Singh, S.; Schoenherr, T.; Ramkumar, M. Risk Assessment in Supply Chains: A State-of-the-Art Review of Methodologies and Their Applications. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 322, 565–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyvi Group-ISM-University of Bordeaux the GeoPolRisk Tool. Available online: https://geopolrisk.org/about/ (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Yan, W.; Wang, Z.; Cao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Z. Criticality Assessment of Metal Resources in China. iScience 2021, 24, 102524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graedel, T.E.; Harper, E.M.; Nassar, N.T.; Nuss, P.; Reck, B.K.; Turner, B.L. Criticality of Metals and Metalloids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 4257–4262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watari, T.; Nansai, K.; Nakajima, K. Review of Critical Metal Dynamics to 2050 for 48 Elements. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USGS. Mineral Commodity Summaries 2020; U.S. Government Publishing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Bach, V.; Berger, M.; Finogenova, N.; Finkbeiner, M. Analyzing Changes in Supply Risks for Abiotic Resources over Time with the ESSENZ Method-A Data Update and Critical Reflection. Resources 2019, 8, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichl, C.; Schatz, M. World Mining Data 2022; Federal Ministry of Agriculture, Regions and Tourism of Republic of Austria: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Teseletso, L.S.; Adachi, T. Future Availability of Mineral Resources: Ultimate Reserves and Total Material Requirement. Miner. Econ. 2021, 36, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöniger, F.; Resch, G. Case Studies Analysis of Prospects for Different CSP Technology Concepts. Deliverable 8.1; MUSTEC Project; Wien, Austria. 2019. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348936677_Case_Studies_analysis_of_prospects_for_different_CSP_technology_concepts_Deliverable_81&ved=2ahUKEwi0w-a1nZ6RAxVMRWwGHQXsOwUQFnoECCAQAQ&usg=AOvVaw1i1taK02saCnjL7f9GqKOh (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Feldman, D.; Margolis, R.; Denholm, P.; Stekli, J. Exploring the Potential Competitiveness of Utility-Scale Photovoltaics Plus Batteries with Concentrating Solar Power, 2015–2030, NREL/TP-6A20-66592; National Renewable energy Laboratory (NREL): Golden, OC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, R.; Remo, T.W.; Margolis, R.M. 2018 U.S. Utility-Scale Photovoltaics-Plus-Energy Storage System Costs Benchmark; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Markaki, M.; Belegri-Roboli, A.; Michaelides, P.; Mirasgedis, S.; Lalas, D.P. The Impact of Clean Energy Investments on the Greek Economy: An Input–Output Analysis (2010–2020). Energy Policy 2013, 57, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banacloche, S.; Gamarra, A.R.; Tellez, F.; Lechon, Y. MUSTEC Deliverable 9.1 Inputs and Results. MUSTEC Project; Version 2; Madrid, Spain. 2020. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/3964021 (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Mahmud, M.A.P.; Huda, N.; Farjana, S.H.; Lang, C. Environmental Impacts of Solar-Photovoltaic and Solar-Thermal Systems with Life-Cycle Assessment. Energies 2018, 11, 2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions Critical Raw Materials Resilience: Charting a Path towards Greater Security and Sustainability; EC: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- EC. COM(2023) 160 ANNEX 1 to 6—Annexes to the Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council Establishing a Framework for Ensuring a Secure and Sustainable Supply of Critical Raw Materials; EC: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Font Vivanco, D. The Role of Services and Capital in Footprint Modelling. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, H.; Wenz, L.; Steckel, J.C.; Minx, J.C. Truncation Error Estimates in Process Life Cycle Assessment Using Input-Output Analysis. J. Ind. Ecol. 2018, 22, 1080–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Ierapetritou, M. Comparison between Different Hybrid Life Cycle Assessment Methodologies: A Review and Case Study of Biomass-Based p-Xylene Production. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 22313–22329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomponi, F.; Lenzen, M. Hybrid Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Will Likely Yield More Accurate Results than Process-Based LCA. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamarra, A.R.; Lechón, Y.; Banacloche, S.; Corona, B.; de Andrés, J.M. A Comparison and Methodological Proposal for Hybrid Approaches to Quantify Environmental Impacts: A Case Study for Renewable Energies. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 867, 161502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montana, F.; Cellura, M.; Di Silvestre, M.L.; Longo, S.; Luu, L.Q.; Riva Sanseverino, E.; Sciumè, G. Assessing Critical Raw Materials and Their Supply Risk in Energy Technologies—A Literature Review. Energies 2024, 18, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC-DG. Internal Market Industry Entrepreneurship and SMEs. In 3rd Raw Materials Scoreboard: European Innovation Partnership on Raw Materials; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Component of the Supply Chain Risk Analysis | Measure by | Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Availability | Abundance | 1/ADPm |

| Resilience | Circularity | ERPRm |

| Dependence | Diversity of supply | Em/Emmax |

| Governance Level | World Governance Indicators (WGI) criteria | GWGIim |

| ADP (kg Sb eq./MWh) | 1/ADP (MWh/kg Sb eq.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PV | CSP | PV | CSP | |

| Al | 2.30 × 10−8 | 3.80 × 10−12 | 4.30 × 107 | 2.60 × 1011 |

| Cu | 2.40 × 10−4 | 3.20 × 10−5 | 4.20 × 103 | 3.20 × 104 |

| Au | 2.80 × 10 | 4.10 × 10−1 | 3.60 × 10−1 | 2.40 × 10 |

| Fe | 1.30 × 10−8 | 9.80 × 10−10 | 7.60 × 107 | 1.00 × 109 |

| Pb | 5.00 × 10−6 | 8.10 × 10−7 | 2.00 × 105 | 1.20 × 106 |

| Ni | 5.50 × 10−7 | 8.90 × 10−8 | 1.80 × 106 | 1.10 × 107 |

| Pt | 3.30 × 10−2 | 1.60 × 10−2 | 3.10 × 101 | 6.40 × 101 |

| Ag | 1.20 × 10−2 | 2.00 × 10−3 | 8.50 × 101 | 4.90 × 102 |

| Sn | 3.10 × 10−5 | 7.60 × 10−6 | 3.20 × 104 | 1.30 × 105 |

| Zn | 2.60 × 10−6 | 5.90 × 10−7 | 3.80 × 105 | 1.70 × 106 |

| Total | 2.80 × 10 | 4.30 × 10−1 | 3.50 × 10−1 | 2.30 × 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gamarra, A.R.; Lechón, Y.; Banacloche, S.; de Andrés Almeida, J.M. A Methodological Proposal for the Metals’ Supply Chain Risk Analysis of Investments Applied to Solar Energy Technologies in Europe. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10827. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310827

Gamarra AR, Lechón Y, Banacloche S, de Andrés Almeida JM. A Methodological Proposal for the Metals’ Supply Chain Risk Analysis of Investments Applied to Solar Energy Technologies in Europe. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10827. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310827

Chicago/Turabian StyleGamarra, Ana Rosa, Yolanda Lechón, Santacruz Banacloche, and José Manuel de Andrés Almeida. 2025. "A Methodological Proposal for the Metals’ Supply Chain Risk Analysis of Investments Applied to Solar Energy Technologies in Europe" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10827. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310827

APA StyleGamarra, A. R., Lechón, Y., Banacloche, S., & de Andrés Almeida, J. M. (2025). A Methodological Proposal for the Metals’ Supply Chain Risk Analysis of Investments Applied to Solar Energy Technologies in Europe. Sustainability, 17(23), 10827. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310827