Designing with Spontaneity: The Return to Nature in the Contemporary City. Biodiversity Networks and Adaptive Landscapes in Eastern Rome

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Why a Design Device Now?

1.2. From “Greening” to Process-Based Landscape Infrastructure

1.3. Why Urban? Why Landscape?

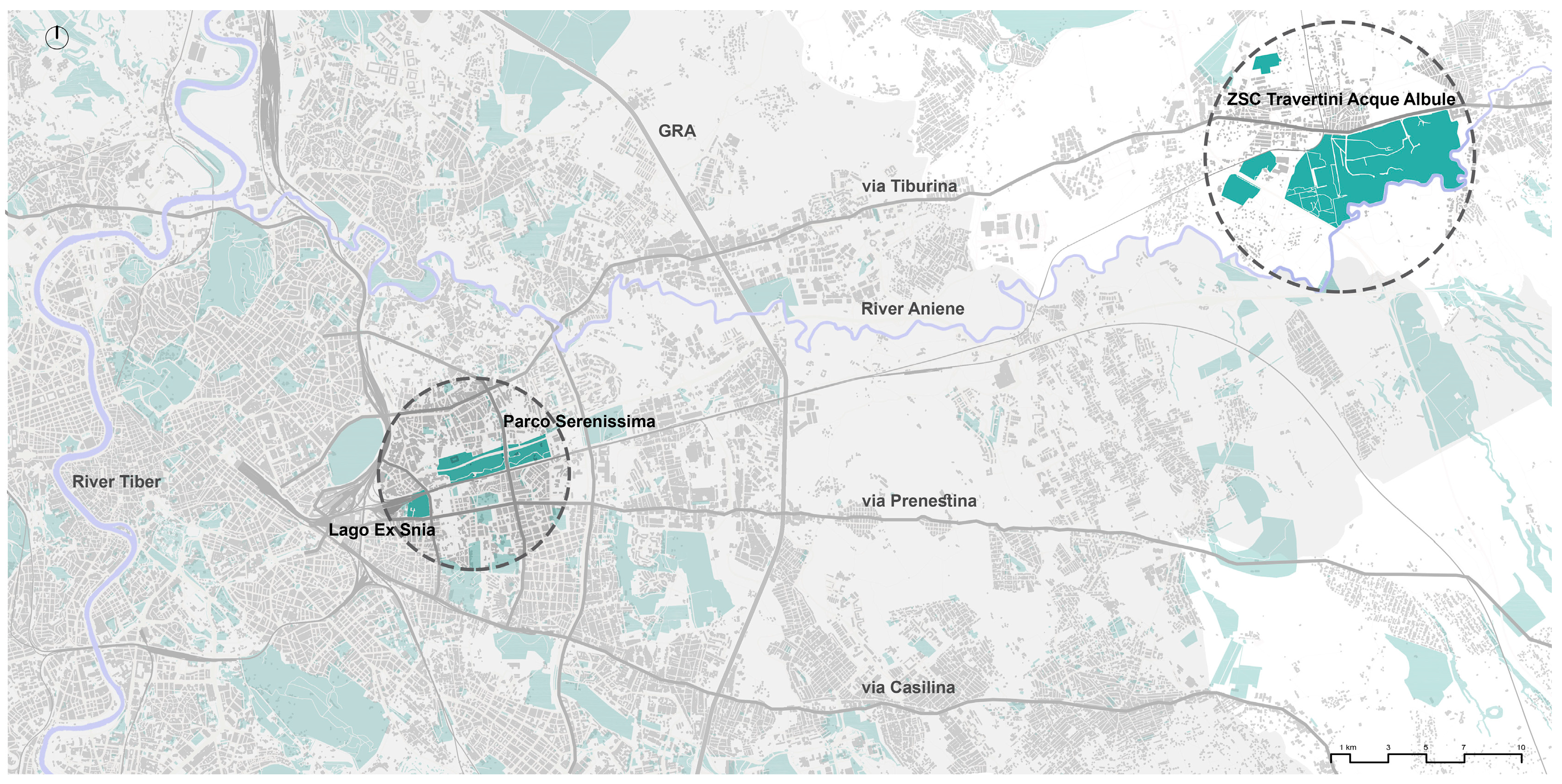

1.4. The Eastern Rome: A Data-Rich Opportunity

- (a)

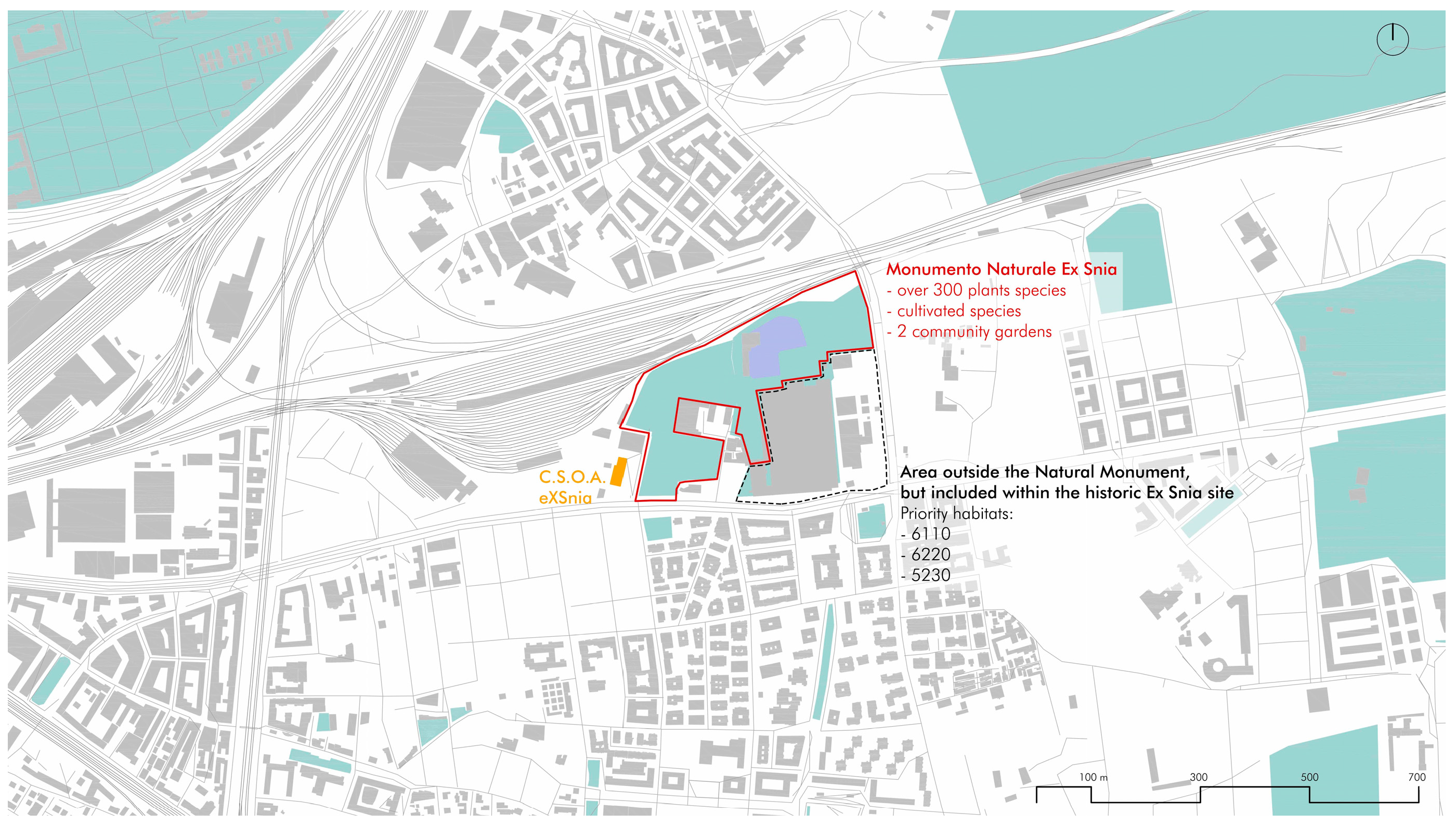

- Ex Snia Viscosa

- (b)

- Parco della Serenissima

- (c)

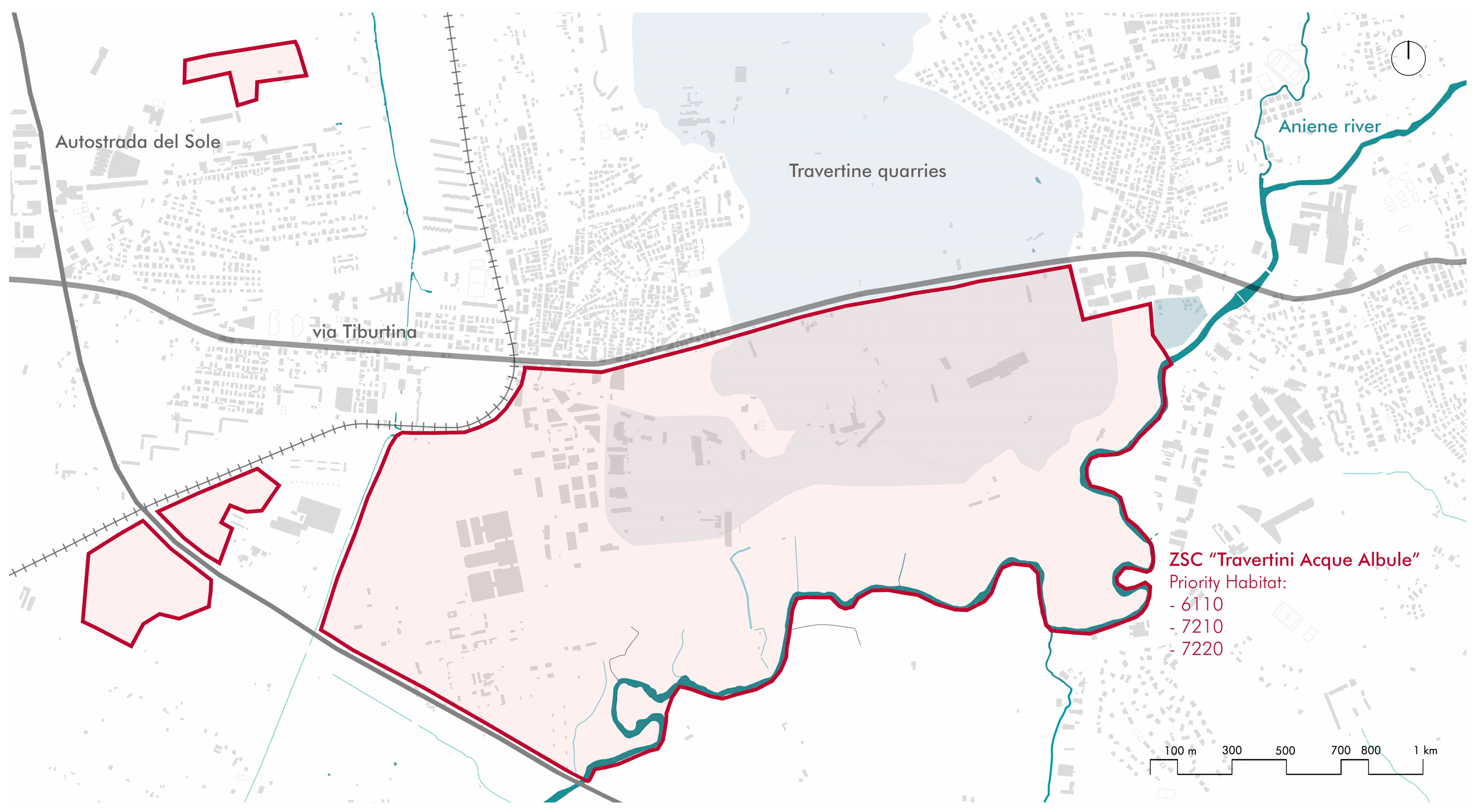

- ZSC “Travertini Acque Albule”

1.5. Aim and Contribution

- Access by least impact—limiting physical intrusion through walkways, viewing platforms and strategically placed seasonal closures. A significant example is the work carried out in Berlin’s Südgelände Park to demarcate high-value succession areas and controlled access routes.

- Differential maintenance—adopts mosaic mowing, cut-and-lift regimes, and rotational schedules to sustain habitat heterogeneity.

- Succession windows—reserve temporal windows for natural succession by designating rotating sectors where intervention is intentionally paused to allow structural development.

- Interpretive minimalism—communicates ecological and cultural values with concise, low-impact interventions (signs, minimal wayfinding, digital augmentation) rather than heavy infrastructural artefacts.

- Co-stewardship—formalises civic stewardship through micro-grants, memoranda of understanding, and community monitoring programmes that share custodial responsibilities with public agencies.

- Adaptive monitoring—implements a lightweight set of indicators (species richness, canopy cover, hydrological retention, user satisfaction) reviewed on a multi-annual cycle to inform incremental interventions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. From Spontaneous Vegetation to a Design Principle

2.2. The Safe-to-Fail City: Rewilding and Ecological Infrastructure

2.3. The Policy Turn Toward Low-Maintenance Nature

2.4. Italian Perspectives: Selvatico and Fitopolis

2.5. Archaeology and Ecological Continuity in Rome

2.6. From Theory to Practice: Addressing the Operational Gap

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area and Rationale

3.2. Data Sources and Thematic Outputs

- ISPRA Carta della Natura (2023 edition) for habitat classification and naturalness indices [41];

- Corine Land Cover 2023 for land-use/land-cover consistency and fragmentation patterns [42];

- Geoportale Regione Lazio for hydrography, soil, and elevation models [43];

- Roma Capitale Open Data Portal for administrative boundaries, transport infrastructure, and demographic data [44];

- Ministero della Cultura (MiC)—Sistema Informativo Territoriale for archaeological and heritage datasets [45];

- Published scientific studies and grey literature concerning vegetation, hydrology, and management of the selected sites.

- habitat distribution maps;

- connectivity overlays highlighting stepping stones and barriers;

- a catalogue of institutional and bottom-up projects coded by governance actor and implementation status;

- a set of indicators (patch size, proximity to rails/greenways, degree of management) used to prioritise interventions and pilot sites.

3.3. Analytical Framework

- local/neighbourhood scale—detailed mapping, stakeholder reconnaissance and site-specific design options;

- corridor/metropolitan scale—scenario-building for the Rome–Tivoli axis to test how the three sites could act as strategic nodes within a broader greenway integrating formal parks, informal habitats and heritage sites.

3.4. Expected Outputs

- Thematic maps of spontaneous habitats and connectivity potential;

- Conceptual diagrams illustrating the six design principles in spatial form;

- A narrative scenario for the Rome–Tivoli Greenway, linking local actions to metropolitan-scale policy;

- A policy-oriented discussion proposing regulatory and management innovations.

4. Result

4.1. Overview of the Eastern Rome Landscape

- (a)

- High ecological value in residual zones, particularly those left unmanaged for long periods;

- (b)

- Hybridisation of natural and cultural layers, where ruins, infrastructure, and vegetation co-evolve;

- (c)

- Mismatch between formal protection boundaries and the actual distribution of priority habitats; and

- (d)

- Active civic engagement, often preceding institutional action.

4.2. Ex Snia Viscosa

4.2.1. Site Genesis and Morphology

4.2.2. Vegetation Structure and Habitats

- Riparian woodland dominated by Salix alba, Populus nigra, and Robinia pseudoacacia;

- Hydrophytic belts with Phragmites australis, Typha latifolia, and Cladium mariscus;

- Ruderal grasslands on rubble and compacted soils, featuring Avena sterilis, Bromus diandrus, Trifolium campestre, and Securigera varia [5];

- Thermophilous shrub and pioneer tree communities (Pinus halepensis, Rhamnus alaternus) on concrete debris.

4.2.3. Ecosystem Functions and Social Use

4.3. Parco Della Serenissima

4.3.1. Geomorphology and Hydrology

4.3.2. Cultural and Archaeological Stratification

- A 150 m segment of via Collatina, a Roman consular road;

- A necropolis of approximately 2500 burials;

- A subterranean section of the Aqua Virgo aqueduct.

4.3.3. Informal Practices and Civic Appropriation

4.4. ZSC “Travertini Acque Albule”

4.4.1. Geology and Ecological Structure

- Rocky and shrubby formations on ancient travertine surfaces;

- Pioneer crusts of mosses, lichens, and annual herbs on neo-formed travertine;

- Hygrophilous belts around springs, dominated by Phragmites australis, Cladium mariscus, Juncus inflexus, and Typha latifolia [54].

4.4.2. Habitat Distribution and Boundary Mismatch

4.4.3. Pressures and Governance

4.5. Archaeology and Spontaneous Habitats: Cross-Case Synthesis

4.6. Existing Initiatives and Emergent Scenarios

4.7. Key Findings in Relation to the Six Design Principles

4.8. The Return-to-Nature Device

- Ecologically, they enhance connectivity and climate resilience.

- Economically, they offer low-maintenance solutions compatible with limited public budgets.

- Socially, they foster stewardship and environmental literacy.

5. Discussion

5.1. From Ecological Restoration to Design Transition

5.2. Spontaneity as Infrastructure

5.3. Governance and Co-Stewardship

5.4. The Role of Heritage in Ecological Transition

5.5. Policy Implications for Italian and European Cities

- design briefs for new parks and regeneration areas;

- maintenance contracts adopting differential and adaptive regimes;

- educational programmes that foster ecological literacy;

- monitoring frameworks linking biodiversity indicators with social well-being metrics.

5.6. Socio-Economic and Governance Factors

5.7. Operational Guidance for Applying the Six Design Principles

- Access by least impact—Use removable or elevated structures (e.g., galvanized-steel grate walkways, chestnut-wood boardwalks, or recycled-plastic planks) placed on micro-piles or screw anchors to avoid soil sealing. Seasonal closures can be implemented with rope fencing and lightweight signage.

- Differential maintenance—Mosaic mowing can be performed with brush-cutters or walk-behind flail mowers, leaving 20–30% of patches unmanaged on a three-year rotation to maintain structural heterogeneity. “Cut-and-lift” cycles reduce nutrient accumulation and favour native dry-grassland species.

- Succession windows—Rotating no-intervention sectors can be designated using simple pin markers in GIS management plans; recommended window duration ranges from 18 to 36 months depending on soil fertility and disturbance regimes typical of Mediterranean climates.

- Interpretive minimalism—Signage can rely on QR-based digital interpretation rather than permanent panels; materials should be low-impact (corten, untreated wood). Small-scale wayfinding can follow reversible anchoring to avoid disturbance in archaeological contexts.

- Co-stewardship—Maintenance agreements can be structured around micro-tasks (monitoring, selective cleanup, invasive control) assigned to community groups, using municipal micro-grant schemes (1–5k €/year).

- Adaptive monitoring—A lightweight protocol can focus on 4–5 indicators (species richness, canopy cover, ground permeability, presence/absence of invasive species, user satisfaction), updated annually through combined municipal–citizen monitoring.

5.8. A Design Grammar for Adaptive Urbanism

5.9. The Mediterranean Specificity

5.10. Limitations and Further Research

- Ecological risks: spontaneous vegetation may favour invasive or highly competitive species (e.g., Ailanthus altissima, Robinia pseudoacacia), leading to potential homogenisation. Monitoring protocols with predefined intervention thresholds are necessary.

- Soil and contamination risks: uncertain soil histories require preliminary screening for heavy metals or hydrocarbons before public access or unmanaged succession is permitted.

- Public safety risks: uneven terrain, concealed obstacles and seasonal fuel loads can increase accident and fire risk, necessitating managed access, regular inspections and targeted fuel-reduction measures.

- Quantitative ecological assessment, linking biodiversity indicators and ecosystem services to maintenance regimes;

- Participatory co-design, testing co-stewardship frameworks and adaptive management in pilot projects;

- Comparative studies across Mediterranean cities (e.g., Palermo, Bologna, Athens) to evaluate transferability under different regulatory and governance conditions.

6. Conclusions

- A design grammar, enabling landscape architects to work with spontaneity;

- A governance tool, fostering shared responsibility;

- A policy framework, supporting EU and national biodiversity strategies.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beatley, T. Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Spirn, A.W. The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Data and Projections Sourced from the European Commission’s Mission Board for Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities. Available online: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/funding/funding-opportunities/funding-programmes-and-open-calls/horizon-europe/eu-missions-horizon-europe/climate-neutral-and-smart-cities_en (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Corner, J. The agency of mapping: Speculation, critique, and invention. In Mappings; Cosgrove, D., Ed.; Reaktion Books: London, UK, 1999; pp. 213–252. [Google Scholar]

- Musacchio, L.R. The ecology and culture of landscape sustainability. Landsc. Ecol. 2009, 24, 989–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldheim, C. Landscape as Urbanism: A General Theory; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ahern, J. From fail-safe to safe-to-fail: Sustainability and resilience in the new urban world. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 100, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heatherington, C.; Sargeant, J. A New Naturalism; Packard Publishing Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Alberti, M.; Marzluff, J. Resilience in urban ecosystems: Linking urban patterns to human and ecological functions. Urban Ecosyst. 2004, 7, 241–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartesaghi Koc, C.; Osmond, P.; Peters, A. Towards a comprehensive green infrastructure typology. Urban Ecosyst. 2017, 20, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roma Capitale. Sistema Informativo Territoriale: Indicatori Ambientali e del Verde; Dipartimento Tutela Ambientale: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Regione Lazio. Piano Territoriale Paesistico Regionale (PTPR); Regione Lazio: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Armiero, M. Selve ribelli. Dentro e contro il Wasteocene. In Selve in Città; Bertagna, A., Giberti, M., Eds.; Mimesis Edizioni: Milan, Italy, 2021; pp. 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lago eXSnia: Lago per Tutt*, Cemento per Nessuno. Available online: https://lagoexsnia.wordpress.com/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Buccomino, G.; Gisotti, G.; Dodaro, G. Un ecosistema emergente: Il lago Bullicante a Roma. Geol. Dell’ambiente 2021, 2, 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dipartimento Tutela Ambientale. Progetto di fattibilità tecnica ed economica. Realizzazione di opere di mitigazione socio ambientale Parco della Serenissima. In Relazione Generale Descrittiva; Comune di Roma Capitale: Roma, Italy, 2020; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Sukopp, H.; Werner, P. A Report and Review of Studies and Experiments Concerning Ecology, Wildlife, and Nature Conservation in Urban and Suburban Areas; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kühn, N. Interacting with urban nature. How spontaneous vegetation enhances postmodern greenspaces. In City Meadows. Community Fields in Urban Landscapes; Panzini, F., Ed.; Fondazione Benetton Studi Ricerche-Antiga Edizioni: Treviso, Italy, 2018; pp. 130–158. [Google Scholar]

- Latz, P. Rust Red: Landscape Park Duisburg-Nord; Hirmer Publisher: Munich, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kowarik, I. Working with Wilderness: A Promising Direction for Urban Green Spaces. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2021, 9, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowarik, I.; Langer, A. Natur-Park Südgelände: Linking Conservation and Recreation in an Abandoned Railyard in Berlin. In Wild Urban Woodlands; Kowarik, I., Körner, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 29–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kühn, N. Intentions for the Unintentional. Spontaneous vegetation as the basis for innovative planting design in the urban areas. J. Landsc. Archit. 2006, 1, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, C.; Hauck, T.E.; Ahn, S.; Pasta, S. Paesaggi senza architetti del paesaggio. La bellezza ecologica dei paesaggi urbani informali. AGATHÓN—Int. J. Archit. Art Des. 2023, 13, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, S.L.; Lundholm, J.T. Ecosystem services provided by urban spontaneous vegetation. Urban Ecosyst. 2012, 15, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowarik, I. Novel urban ecosystem, biodiversity, and conservation. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 1974–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J. Extinction of experience: The loss of human–nature interactions. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowarik, I. Urban wilderness: Supply, demand, and access. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. Barcelona Nature Plan 2021–2030; Area of Urban Ecology, Barcelona City Council: Barcelona, Spain, 2021; Available online: https://bcnroc.ajuntament.barcelona.cat/jspui/bitstream/11703/123630/3/Barcelona%20Nature%20Plan%202030%20WEB.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Le Nouveau Plan Biodiversité Pour Paris. Available online: https://www.paris.fr/pages/un-nouveau-plan-biodiversite-pour-paris-5594 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- City of London Corporation. Biodiversity Action Plan 2021–2026; City of London Corporation: London, UK, 2021.

- Ministero della Transizione Ecologica. Strategia Nazionale per la Biodiversità 2030; Ministero Della Transizione Ecologica: Rome, Italy, 2022. Available online: https://www.mase.gov.it/portale/strategia-nazionale-per-la-biodiversit%C3%A0-al-2030 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Marini, S. Il ritorno della selva. In Sylva. Città, Nature, Avamposti; Marini, S., Moschetti, V., Eds.; Mimesis Edizioni: Milan, Italy, 2021; pp. 8–26. [Google Scholar]

- Metta, A. (Ed.) Vacanze. Farsi vago, invaghirsi. In Il paesaggio è un Mostro. Città Selvatiche e Nature Ibride; DeriveApprodi: Rome, Italy, 2021; pp. 115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Coccia, E. Metamorfosi. Siamo Un’unica, Sola Vita; Einaudi: Turin, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso, S. Fitopolis, la Città Vivente; Editori Laterza: Bari, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Angelucci, D.; Gentili, D. Avvertenze. In Roma. Guida Alla Selva; Carreri, F., Gentili, D., Olcuire, S., Eds.; Nero Edizioni: Rome, Italy, 2024; pp. 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Lucchese, F.; Pignatti, E. La vegetazione nelle aree archeologiche di Roma e della Campagna Romana. Quad. Bot. Ambient. Appl. 2009, 20, 3–89. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354949117_La_vegetazione_nelle_aree_archeologiche_di_Roma_e_della_Campagna_Romana (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Fanelli, G. Habitat Prioritari Dell’area SNIA Viscosa. Available online: https://lagoexsnia.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/allegato_4.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Misure di Conservazione del SIC IT6030033 “Travertini Acque Albule (Bagni di Tivoli)”. Available online: https://www.regione.lazio.it/sites/default/files/documentazione/AMB_DGR_813_06_12_2017_All1.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Iamonico, D.; Di Pietro, R. L’Ecologia vegetale per la conservazione attiva e la gestione sostenibile del territorio. Il caso dell’area protetta “Travertini Acque Albule”. Urbanistica 2018, 15, 209–213. [Google Scholar]

- ISPRA. Carta della Natura—Edizione 2023; Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale: Rome, Italy, 2023. Available online: https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/it/servizi/sistema-carta-della-natura (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Copernicus Land Monitoring Service. Corine Land Cover 2023 Database; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024; Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/en/products/corine-land-cover (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Regione Lazio. Geoportale Dati Ambientali; Regione Lazio: Rome, Italy, 2024; Available online: https://geoportale.regione.lazio.it/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Roma Capitale. Portale Open Data; Rome, Italy, 2024; Available online: https://dati.comune.roma.it/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Ministero della Cultura. Sistema Informativo Territoriale—Archeologia e Paesaggio; MiC: Rome, Italy, 2023; Available online: https://www.archeositarproject.it/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- ETRS89/UTM zone 33N (EPSG:25833); EPSG Geodetic Parameter Dataset. International Association of Oil & Gas Producers (IOGP): London, UK, 2024. Available online: https://epsg.io/25833 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Regione Lazio. Monumento Naturale Lago Ex Snia Viscosa: Misure di Conservazione; RomaNatura: Rome, Italy, 2021; Available online: https://www.parchilazio.it/lago_ex_snia_viscosa (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Mattioli, W.; Chiarabaglio, P.M.; Rosso, L.; Meloni, R.; Corona, P. Valutazione speditiva della potenzialità fitodepurativa di boschi ripariali. For. @-J. Silvic. For. Ecol. 2020, 17, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Progetto “Api per il Lago”. Available online: https://lagoexsnia.wordpress.com/progetto-api-per-il-lago/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Battisti, C.; Dodaro, G.; Fanelli, G. Paradoxical environmental conservation: Failure of an unplanned urban development as a driver of passive ecological restoration. Environ. Dev. 2017, 24, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regione Lazio. Carta Idrogeologica della Città Metropolitana di Roma Capitale; Rome, Italy, 2023; Available online: https://geoportale.regione.lazio.it/maps/870 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Comitato Parco LineaRE. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/ComitatoParcoLineaRE/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Sapienza University Research Grants 2020/Large Projects: ARCHAEOGRAB. Green Network for Sustainable Mobility and Public. A Space Projects for the Enhancement of Archaeological and Natural Heritage in the Suburbs of the City of Rome. Available online: https://research.uniroma1.it/progetti-di-ricerca/111735/vista (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Giardini, M. Aspetti floristici e vegetazionali dei travertini delle Acque Albule (Tivoli, Roma). In Atti del Convegno sul Tema: Il Travertino. Aspetti Naturalistici e Sfruttamento Industriale All’inizio del Terzo Millennio; Martella, M., Ed.; Ripoli snc: Rome, Italy, 2000; pp. 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Montelucci, G. Investigazioni botaniche nel Lazio. III. Aspetti della vegetazione dei travertini delle Acque Albule (Tivoli). Nuovo G. Bot. Ital. 1947, 54, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Associazione Parco dei Travertini e Delle Acque Albule. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/parcotravertiniacquealbule (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Capuano, A. Living Amidst the Ruins in Rome: Archaeological Sites as Hubs for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuano, A.; Giovannelli, A.; Ahmed, S.R.; Azzolini, A.; Visconti, C. Serenissima. In Grab the City; Capuano, A., Frediani, D., Giancotti, A., Giovannelli, A., Eds.; TLON Aleph: Rome, Italy, 2024; pp. 200–207. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, W.R.; Gilpin, M.E.; Aber, J.D. Restoration Ecology: A Synthetic Approach to Ecological Research, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Hallett, L.M.; Standish, R.J.; Hulvey, K.B.; Gardener, M.R.; Suding, K.N.; Starzomski, B.M.; Murphy, S.D.; Harris, J.A. Towards a Conceptual Framework for Novel Ecosystems. In Novel Ecosystems: Intervening in the New Ecological World Order; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Prominski, M. Designing Landscapes as Evolutionary Systems. Des. J. 2005, 8, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Benedict, M.A.; McMahon, E.T. Green Infrastructure: Linking Landscapes and Communities, 1st ed.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, R.; Pauleit, S. From multifunctionality to multiple ecosystem services? Ecol. Indic. 2014, 42, 516–528. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, S.R.; Iaione, C. Co-Cities: Innovative Transitions toward Just and Self-Sustaining Communities, 1st ed.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C.; Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Norberg, J. Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 441–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030; Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/biodiversity-strategy-2030_en (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Mostafavi, M.; Doherty, G. (Eds.) Ecological Urbanism; Harvard GSD: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Di Giovine, M. Conoscenza della flora, conoscenza dell’ambiente: Fruizione e tutela. In Atlante della Flora di Roma, 1st ed.; Celesti Grapow, L., Ed.; Argos Edizioni: Roma, Italy, 1995; pp. 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Clément, G. Manifeste du Tiers Paysage; Sujet/Objet: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Viganò, P.; Cavalieri, C. (Eds.) The Horizontal Metropolis. A Radical Project; Park Books: Zurich, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Design Principle | Empirical Evidence | Spatial/Operational Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Access by least impact | Sensitive habitats at Ex Snia and ZSC “Travertini Acque Albule” require controlled entry. | Use boardwalks and viewing points; introduce seasonal closures. |

| Differential maintenance | Grasslands and riparian zones respond differently to mowing frequency. | Apply mosaic mowing and cut-and-lift regimes to enhance diversity. |

| Succession windows | Long-term spontaneous evolution at Ex Snia shows structural benefits. | Designate rotating zones for temporal succession rather than fixed composition. |

| Interpretive minimalism | Heritage layers at Serenissima and ZSC “Travertini Acque Albule” allow ecological education without heavy infrastructure. | Provide concise, bilingual signage and digital interpretation tools. |

| Co-stewardship | Community management at Ex Snia sustains ecological quality. | Formalize agreements and micro-grants for civic caretakers. |

| Adaptive monitoring | Lack of consistent data across sites hampers management. | Introduce simple indicators—species richness, canopy cover, user satisfaction—updated annually. |

| Dimension | Ex Snia Viscosa | Parco della Serenissima | Travertini Acque Albule (TAA) | Comparative Synthesis/Implications for Design Principles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ecological structure | Neo-formed lacustrine and wetland system; high species richness; priority habitats both inside and outside the protected boundary. | Hygrophilous woodland, springs and riparian edges; vegetation not fully mapped; high potential but fragmented. | Travertine terraces, rocky pioneer habitats, hygrophilous belts; several priority habitats; strong microtopographic diversity. | All sites host habitats of ecological interest; Ex Snia and the TAA exhibit greater ecological complexity, while Serenissima requires preliminary mapping → affects adaptive monitoring. |

| 2. Cultural/archaeological layers | Industrial archaeology; ruins provide niches for vegetation and informal uses. | Roman road, necropolis, Aqua Virgo; archaeological constraints limit heavy interventions. | Roman bridges, quarry voids, historic farmhouses; archaeological features interwoven with spontaneous vegetation. | All cases show stratification; Serenissima and the TAA are more constrained → implications for interpretive minimalism and access strategies. |

| 3. Degree of abandonment and disturbance | Long-term abandonment; strong spontaneous succession; active community stewardship mitigates degradation. | Severe neglect; dumping; vulnerable to invasive scrub and unauthorised uses. | Chronic dumping (“Fridge Valley”); fragmentation due to infrastructure; low institutional maintenance. | Ex Snia exhibits “positive abandonment” with stewardship; Serenissima and the TAA require stronger governance → informs differential maintenance and co-stewardship. |

| 4. Accessibility and social use | High informal use; established paths; community and educational activities. | Low accessibility; limited paths; informal gardens; perceived insecurity. | Low public use; restricted access due to road and rail barriers; low public awareness. | Accessibility decreases from Snia → Serenissima → TAA; major implications for access by least impact and interpretive minimalism. |

| 5. Governance and stewardship | Strong bottom-up stewardship; active civic networks. | Weak institutional presence; emerging but fragmented community engagement. | Mixed governance (regional/municipal/private); civic groups advocate ecological restoration and park expansion. | Ex Snia is a model of co-stewardship; Serenissima requires hybrid governance; SAC requires multi-scalar institutional coordination. |

| 6. Protection status and regulatory constraints | Partial protection (Natural Monument); priority habitats also outside current boundary. | Local planning zoning as “public green”; strong archaeological protection; no ecological management plan. | Natura 2000 site; boundary misalignment with actual habitat distribution; strict procedural constraints. | Increasing levels of constraints shape the range of feasible actions → relevant for succession windows and adaptive planning. |

| 7. Maintenance regimes | Mostly informal, low-input; selective volunteer interventions. | No systematic maintenance; occasional clearing; unmanaged succession. | Minimal institutional maintenance; disturbance-driven dynamics. | All sites need differential, low-intensity regimes; Ex Snia already shows adaptive informal practices. |

| 8. Main challenges | Legal disputes; limited institutional recognition of habitats outside the protected perimeter. | Lack of monitoring; degradation; poor accessibility. | Boundary mismatch; dumping; fragmentation from infrastructures. | Challenges vary by scale and governance → essential for tailoring the six principles. |

| 9. Opportunities for applying the six design principles | High: strong stewardship, ecological diversity, public awareness. | Medium–high: heritage–ecology interface; requires monitoring and governance. | High at landscape scale: ecological corridor potential and habitat richness. | Sites are complementary: each reveals different operational opportunities for the six principles. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahon Vasquez, L.A.; Capuano, A. Designing with Spontaneity: The Return to Nature in the Contemporary City. Biodiversity Networks and Adaptive Landscapes in Eastern Rome. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10828. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310828

Ahon Vasquez LA, Capuano A. Designing with Spontaneity: The Return to Nature in the Contemporary City. Biodiversity Networks and Adaptive Landscapes in Eastern Rome. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10828. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310828

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhon Vasquez, Lisbet Alessandra, and Alessandra Capuano. 2025. "Designing with Spontaneity: The Return to Nature in the Contemporary City. Biodiversity Networks and Adaptive Landscapes in Eastern Rome" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10828. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310828

APA StyleAhon Vasquez, L. A., & Capuano, A. (2025). Designing with Spontaneity: The Return to Nature in the Contemporary City. Biodiversity Networks and Adaptive Landscapes in Eastern Rome. Sustainability, 17(23), 10828. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310828