Abstract

This paper proposes the “return-to-nature” as an operational design framework for integrating spontaneous habitats and informal green areas into contemporary urban landscapes. Using spatial analysis, field observations, and open-access ecological datasets, the study examines three sites in Eastern Rome—Ex Snia Viscosa, Parco della Serenissima, and the ZSC “Travertini Acque Albule”—to evaluate how low-maintenance, process-based landscapes can contribute to biodiversity networks and climate adaptation. The results reveal recurrent patterns, including the ecological value of unmanaged areas, the interaction between cultural heritage and spontaneous vegetation, and inconsistencies between formal protection boundaries and actual habitat distribution. Based on these findings, six operational principles are defined: access by least impact, differential maintenance, succession windows, interpretive minimalism, co-stewardship, and adaptive monitoring. The study also advances the idea of a Rome–Tivoli Greenway as a transferable Mediterranean model capable of applying these principles at a territorial scale. The findings show that spontaneous urban nature can function as ecological infrastructure, support community stewardship, and reduce management costs, while also presenting risks such as invasive species dynamics and potential conflicts over access. The paper concludes with policy mechanisms—adaptive maintenance regimes, stewardship agreements, and updated planning tools—to operationalise the proposed approach and support more resilient and biodiverse urban landscapes. Overall, the “return-to-nature” framework provides a transferable approach for cities seeking to enhance biodiversity, resilience, and socio-ecological integration through lighter and more adaptive design strategies.

1. Introduction

1.1. Why a Design Device Now?

The growing desire for nature in increasingly congested cities should not be interpreted merely as an aesthetic or nostalgic impulse, but rather as a manifestation of a profound cultural and environmental shift. This tendency reflects the search for a renewed balance between anthropised and ecological spaces, in response to systemic challenges such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and the need for sustainable resource management [1,2].

Rapid climatic shifts—rising mean temperatures, more frequent heatwaves, and short-duration high-intensity rainfall—are disrupting ecosystems and urban liveability. Biodiversity is declining under the combined effects of habitat destruction, degradation, and fragmentation, often intensified by wildfires and floods. Fossil-fuel emissions, deforestation, and intensive livestock systems amplify these dynamics. In this context, cities—though they occupy only the 3% of global land—will concentrate nearly 85% of the world’s population by 2050 [3]; they are therefore the primary theatres where ecological transitions must be designed, implemented, and maintained.

Within this framework, landscape design assumes a strategic role in urban regeneration processes, acting as a mediating device between nature and artefact, between infrastructure and environment. The experimentation with unconventional landscape solutions—including spontaneous habitats, informal landscapes, and low-maintenance design models—represents an innovative approach to the transformation of urban space [4]. Such strategies embrace the dynamic and adaptive character of natural processes, integrating temporal and ecological dimensions into design practice and overcoming the traditional conception of landscape as a static or finalised form.

1.2. From “Greening” to Process-Based Landscape Infrastructure

The goal is not the artificial reconstruction of idealised natural scenarios, but the reactivation of ecological processes capable of regenerating degraded soils, reconnecting fragmented ecosystems, and fostering new relationships between inhabitants and their environment [5]. In this perspective, nature is no longer conceived as a decorative or separate element, but as a living and productive infrastructure integrated into the urban metabolism [6].

Focusing on urban contexts means recognising that cities today constitute the primary field for experimenting with effective ecological transitions. Here, landscape design can operate as both an environmental and social balancing tool, intervening on interstitial spaces, abandoned areas, infrastructural margins, and urban voids. Practices such as urban forestry, ecological corridors, spontaneous gardens, and multifunctional green systems become devices of regeneration that improve the ecological footprint, reduce maintenance costs, conserve biodiversity, and restore environmental and symbolic quality to the urban landscape [7].

In this sense, the return to nature [8] emerges as an operative category of contemporary design: a paradigm guiding the construction of more resilient, inclusive, and sustainable cities, where landscape is not a complement but a structural component of urban transformation.

1.3. Why Urban? Why Landscape?

Here, the design device is defined as a set of interlinked concepts and tactics through which designers intentionally collaborate with natural spontaneity rather than suppress it. In practice, this means shifting from static, maintenance-intensive compositions to dynamic, safe-to-fail systems that accept succession, seasonality, and disturbance as drivers of form and function [9]. In policy terms, it aligns with the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, which calls for expanding and improving urban green infrastructure through nature-based solutions.

Landscape design occupies a distinctive position at the intersection of ecology, infrastructure, and everyday use, especially in interstitial or abandoned areas where spontaneous vegetation already performs valuable functions. Low-maintenance, process-based strategies can regenerate derelict or marginal land; improve the city’s ecological footprint and microclimate; conserve and connect biodiversity through affordable networks; reduce lifecycle costs compared with conventional horticultural models; and broaden access to meaningful nature experiences in underserved districts [10].

1.4. The Eastern Rome: A Data-Rich Opportunity

Rome provides a unique context: 86,000 ha (approximately 67%) of its 129,000 ha territory are green, agricultural, or otherwise non-built, and 13.78 mq of green per inhabitant is publicly accessible [11,12]. The eastern quadrant concentrates rail corridors, abandoned industrial land, quarry landscapes, and archaeological assets, forming a palimpsest where spontaneous habitats are already widespread. Three sites exemplify this potential:

- (a)

- Ex Snia Viscosa

A 7.5-hectare area in Municipio V where Lago Bullicante is now located, which once hosted the Snia Viscosa factory, which produced synthetic rayon fibres from 1923 to 1954. After decades of abandonment, construction works for a commercial and residential complex in the 1990s intersected the water table, causing groundwater to re-emerge and forming the present artificial lake. Over time, the marshy area has attracted numerous bird and animal species as well as people, “in a sort of multispecies alliance that managed to halt speculation” [13] (p. 32), albeit not definitively. To this day, activists such as those of the Centro sociale occupato autogestito (Csoa) eXSnia [14] continue to fight for the transformation of the former industrial site into a park accessible to all, despite the establishment of the Natura Monument “Lago Ex Snia Viscosa” by the Lazio Region in June 2020 [15].

- (b)

- Parco della Serenissima

It covers approximately 40 ha located in the north-eastern quadrant of the city, in a strip of territory of Municipio IV lying between the Rome–Pescara railway and the A24 motorway. The area is zoned as public green space in the current Piano Regolatore Generale (PRG) of Rome [16]. Between 1997 and 2013 excavations for the Milan–Naples high-speed railway unearthed a substantial archaeological complex: a 150 m stretch of the via Collatina, middle-Republican tombs and an imperial necropolis with roughly 2500 burials, as well as a subterranean section of the Aqua Virgo aqueduct. Alongside this historical and archaeological richness there is a valuable wetland area, including typical trees such as black poplar and white willow, and a notable presence of both aquatic and hygrophilous herbaceous species [16].

- (c)

- ZSC “Travertini Acque Albule”

The “Travertini Acque Albule” site (“Travertini Acque Albule” is the name of a “Zona Speciale di Conservazione” (ZSC)—A Special Area of Conservation—Code IT6030033, located in Bagni di Tivoli (Italy))—designated first as a Sito d’Importanza Communitaria (SIC) in 2008 and in 2019 as a Zona Speciale di Conservazione (ZSC) by ministerial decree—extends over 43,009 ha in the eastern Roman countryside. It is bounded to the south by the Aniene River, to the south-west by the A1 motorway (Autostrada del Sole), to the north by the via Tiburtina, and to the east by Monte Catillo. The ZSC was established because it is the principal travertine deposit in the Italian peninsula and is therefore characterised by very particular plant communities (Referring to “habitat prioritari” (priority habitats) 6110 e 6220, namely “calcareous rocky slopes with chasmophytic vegetation of the Alysso-Sedion albi” and “pseudo-steppe with grasses and annuals of the Thero-Brachypodietea”, as defined by The Habitats Directive 92/43/CEE. The Habitat Directive commonly refers to the establishment of the Natura 2000 network, introduced by Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural and semi-natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora). Despite its high ecological value, the area has remained for years in a state of abandonment and degradation, suffering from open-air dumping—including the so-called “Frigo Valley”.

Although this research is primarily qualitative, existing datasets provide indicative metrics. At Ex Snia Viscosa, floristic surveys document over 350 vascular plant species and more than 70 bird species, with a 22% increase in shrub and tree cover between 1995 and 2022. At the Travertini Acque Albule ZSC, over 420 taxa have been recorded, including several regionally protected species; yet priority habitats cover only 6.8% of the designated boundary. Conversely, the Serenissima area lacks systematic vegetation mapping, a gap that informs our call for targeted monitoring in Section 5.8.

1.5. Aim and Contribution

To clarify the practical contribution of this work, we explicitly articulate six operational design principles derived from empirical observations of East Rome and emblematic projects, such as the Landschaftspark Duisburg-Nord, the Natur-Park Südgelände, and the Park am Nordbahnhof in Germany. Each principle is stated with a concise explanation and a concrete example:

- Access by least impact—limiting physical intrusion through walkways, viewing platforms and strategically placed seasonal closures. A significant example is the work carried out in Berlin’s Südgelände Park to demarcate high-value succession areas and controlled access routes.

- Differential maintenance—adopts mosaic mowing, cut-and-lift regimes, and rotational schedules to sustain habitat heterogeneity.

- Succession windows—reserve temporal windows for natural succession by designating rotating sectors where intervention is intentionally paused to allow structural development.

- Interpretive minimalism—communicates ecological and cultural values with concise, low-impact interventions (signs, minimal wayfinding, digital augmentation) rather than heavy infrastructural artefacts.

- Co-stewardship—formalises civic stewardship through micro-grants, memoranda of understanding, and community monitoring programmes that share custodial responsibilities with public agencies.

- Adaptive monitoring—implements a lightweight set of indicators (species richness, canopy cover, hydrological retention, user satisfaction) reviewed on a multi-annual cycle to inform incremental interventions.

These principles can make the return to nature device operational: they translate the ecological process into spatial tactics and governance tools suitable for Mediterranean urban contexts.

It is important to clarify that the six design principles proposed here operate at a conceptual and strategic level. Their translation into detailed design elements, technical layouts or project drawings requires site-specific design development and therefore falls beyond the scope of this study. The case studies presented illustrate potential applications, but they do not constitute fully elaborated design proposals.

2. Literature Review

2.1. From Spontaneous Vegetation to a Design Principle

Spontaneous vegetation—once regarded as a sign of neglect—has increasingly been recognised as a resource for urban design. Ecologists have long demonstrated that disturbed or marginal areas can sustain high biodiversity and deliver ecosystem services [17]. The shift toward design engagement emerged through late-twentieth-century European projects that celebrated succession as a creative force.

In the late 1980s, landscape architects began to consider this type of vegetation in landscape projects [18]. Early pioneering interventions in Germany started by valuing the vegetation already present, mostly on former industrial sites. The Duisburg-Nord Landscape Park by Peter Latz is an eloquent example where park aesthetics and structure were founded on pre-existing spontaneous plant communities and on natural succession processes [19]. In Berlin, similar strategies created projects where unkempt nature was preserved rather than replaced: interventions were often limited to defining access (entrances and paths) to increase the attractiveness of spontaneous habitats for a wider public [20]. In the Südgelände Park, the former rail yard became an accessible urban public space while continuing to host local fauna and successional vegetation [21]. These examples revealed that minimal intervention can generate complex ecologies. Kühn [22] described this as “intentional unintentionality”. Spontaneity thus becomes not the opposite of design but one of its authentic expressions.

2.2. The Safe-to-Fail City: Rewilding and Ecological Infrastructure

From the 1980s onward, cost-containment policies in several central European countries weakened the management of urban open spaces, leading to widespread deterioration and shifting notions of care; high-cost ornamental vegetation is thus expected to be restricted to limited areas [22]. In this context, urban spontaneous vegetation gains relevance as a non-sown habitat shaped by colonisation and succession [23], providing essential ecosystem services, as shown by Robinson and Lundholm [24]. Kowarik describes these habitats as “beacons of biodiversity”, often richer than surrounding rural areas [25], while Northern European studies highlight benefits such as CO2 reduction, stormwater retention, particulate filtration, noise mitigation, and habitat provision [24].

Urban rewilding extends these dynamics to the metropolitan scale: by limiting inputs and accepting ecological uncertainty, it promotes both environmental and fiscal sustainability. Ahern’s safe-to-fail landscapes [7] and Alberti and Marzluff’s notion of resilience as adaptive capacity [9] support this return to nature approach, centred on performance rather than permanence. Contemporary frameworks further frame nature as everyday infrastructure: Beatley’s biophilic cities integrate ecological presence into daily experience [1], and Waldheim [6] and Corner [4] emphasise landscape as a structural medium organising ecological and social flows. In parallel, Soga and Gaston warn of the “extinction of experience” and advocate easy access to spontaneous spaces [26], underscoring the need for design strategies that enhance opportunities—both physical and mental—to engage with unkempt nature [27].

2.3. The Policy Turn Toward Low-Maintenance Nature

Major European cities are increasingly embedding this paradigm into planning frameworks. The Barcelona Nature Plan 2021–2030 [28], the Paris Plan Biodiversité 2018–2024 [29], and London’s Biodiversity Action Plan 2021–2026 [30] all promote spontaneous, low-input landscapes, shifting the focus from visual control to ecological function. Barcelona’s plan advances ecological management through resource efficiency, natural-process design, meadow conversion, and the promotion of wild species [28], while Paris and London adopt similar strategies to address heat islands and urbanisation pressures.

These initiatives show how the return to nature approach can link policy ambitions with design practice. In Italy, however, technical norms still favour formal planting and uniform maintenance. Although the National Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 aligns with EU goals to “have more nature in cities” [31], it does not explicitly support unplanned habitats, revealing a gap in operational guidance for integrating spontaneous nature into urban networks.

2.4. Italian Perspectives: Selvatico and Fitopolis

In Italy, reflections on urban wildness have gained relevance within academic discourse. The PRIN project SYLVA. Ripensare la “selva” promotes a renewed alliance between organic and artificial realms, calling for updated imaginaries and design languages for contemporary landscape practice. Marini highlights how nature re-enters the city through neglect and abandonment, requiring alternative aesthetic and methodological frameworks [32]. Similarly, Metta’s work on “urban vacants” and “advanced landscapes” reframes abandoned or transitional areas as experimental laboratories, where indeterminacy and waiting become deliberate design tools [33].

Philosophical and biological perspectives further enrich this debate: Coccia’s reflections on metamorphosis underscore the continuity among living forms [34], while Mancuso’s Fitopolis envisions the city as a plant-inspired organism—horizontal, multicentric, and diffuse [35].

However, operational translation remains limited in Italy. Most initiatives involving spontaneous vegetation arise from bottom-up practices that blend sociability, art, and ecology. Armiero’s “selve ribelli” exemplify such contested spaces reclaimed against urban expansion, embodying counter-hegemonic identities [13]. Overall, while Europe hosts numerous examples and experiments, in Italy, the practical uptake of these ideas is uneven; spontaneous-led design is largely visible in grassroots initiatives where social action, artistic practices, and nature hybridise to generate innovative forms of urban space.

2.5. Archaeology and Ecological Continuity in Rome

Rome offers a paradigmatic context for urban wildness: as Angelucci and Gentili note, its morphology blurs the line between urban and natural systems [36]. With 67% of its territory composed of green, agricultural and undeveloped land, the city forms a vast ecological matrix, further enriched by abandoned areas and disused sites.

Archaeological landscapes play a central role in this continuity. Lucchese and Pignatti show that ancient sites frequently harbour exceptional biodiversity because protection regimes limit disturbance [37]. Ruins and open archaeological grounds thus function as ecological corridors where cultural memory and ecological processes converge.

Botanical surveys conducted within the National Biodiversity Future Centre and related research confirm this value: archaeological sites host flora and habitats of conservation interest, and comparative inventories across Mediterranean contexts show that they often function as refuges for threatened species.

Over recent decades, several disused areas have become strategic components of emerging ecological networks in Eastern Rome—often through public–citizen reclamation—most notably Ex Snia Viscosa, Parco della Serenissima and sections of the ZSC “Travertini Acque Albule”. Together, these sites illustrate distinct intersections of archaeology, industrial heritage, and spontaneous vegetation: Ex Snia hosts neo-formed plant communities, including habitats listed under the Habitats Directive [38]; Parco della Serenissima overlays a necropolis and natural springs with riparian vegetation, producing a layered ecological–cultural palimpsest [39]; and the ZSC “Travertini Acque Albule” contains a mosaic of travertine-related habitats of high botanical interest, some extending beyond the formal conservation perimeter [40].

2.6. From Theory to Practice: Addressing the Operational Gap

Despite a substantial theoretical discourse, Italy still lacks coherent methods for integrating spontaneous habitats into design. Existing approaches remain fragmented, and no shared device translates ecological thinking into actionable spatial and governance strategies. The return-to-nature framework proposed here addresses this gap by recognising unplanned and informal landscapes as legitimate elements of the contemporary city and as vehicles for adaptive, participatory and time-based design.

The literature converges on a core idea: working with spontaneity allows designers to pursue ecological, social and economic goals simultaneously. Building on this premise, the six operational principles previously outlined provide a practical grammar for applying the return-to-nature approach. They are designed to respond to the specific combinations of vegetation structure, accessibility, degrees of abandonment, and archaeological or industrial heritage found in the study areas and are tested empirically in the three case studies that follow.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area and Rationale

The research focuses on Eastern Rome, a landscape corridor connecting the dense urban core to the peri-urban systems toward Tivoli. This area brings together compact built fabric, abandoned industrial estates, major transport infrastructures, archaeological stratifications and remnants of agrarian and natural matrices, forming a mosaic where spontaneous habitats already fulfil ecological and social functions. The three case studies were selected both for their intrinsic vegetational, cultural and social qualities and for their strategic role within a prospective Rome–Tivoli greenway capable of linking formal parks, informal nature and heritage assets.

Ex Snia Viscosa was chosen for its neo-formed ecological complexity and strong civic engagement. The unexpected resurgence of groundwater in the 1990s generated a lacustrine–palustrine system within an industrial ruin, around which riparian belts, multispecies meadows and thermophilous scrubs developed. These assemblages include habitats listed under the Habitats Directive [15,38], making the site particularly relevant for conservation. It also illustrates how grassroots stewardship can stabilise and enhance spontaneous nature in a dense urban context.

Parco della Serenissima combines archaeological richness with active hydrology. Springs and hygrophilous woodlands overlay volcanic tuff and pozzolana substrates, while recent infrastructural works exposed significant archaeological layers (via Collatina, necropolis, Aqua Virgo). These conditions simultaneously constrain intrusive interventions and offer interpretive and governance frameworks for recognising and protecting spontaneous habitats. Informal uses by residents reinforce the site’s social significance.

The ZSC “Travertini Acque Albule” represents the peri-urban end of the gradient: a Natura 2000 site of travertine terraces and thermally fed springs, hosting a patchwork of rocky pioneer, hygrophilous and shrubby communities. Empirical mapping reveals a mismatch between protection boundaries and the actual distribution of priority habitats—only 6.8% of the ZSC contains listed habitats, while more than 100 hectares of equivalent habitat lie outside the perimeter—raising important policy questions [40].

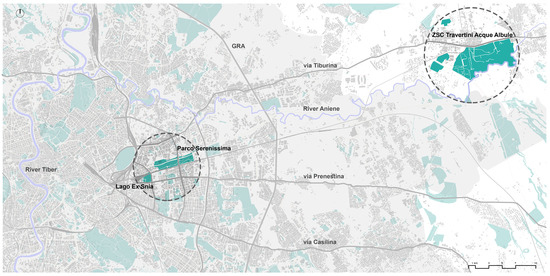

Together, the three sites form a morphological and governance gradient—from civic wilderness embedded in dense fabric, through infrastructural-archaeological interstices, to peri-urban protected landscape—that tests the transferability of the return-to-nature device across scales (Figure 1). Individually, they display distinct vegetation structures, accessibility levels and management or abandonment conditions; collectively, they offer spatial anchors for a Rome–Tivoli greenway integrating informal habitats, formal parks and heritage sites into a resilient metropolitan green infrastructure.

Figure 1.

Eastern Rome and the three case studies (Lago Ex Snia Viscosa; Parco della Serenissima; ZSC “Travertini Acque Albule”). The map highlights the close spatial proximity of the three sites and their directional alignment toward Rome’s eastern quadrant. Data sources: Geoportale Regione Lazio (2023), ISPRA Carta della Natura (2023), Corine Land Cover (2023) [41,42,43] (drawing and GIS processing by the authors).

3.2. Data Sources and Thematic Outputs

The analysis integrates multiple open-access and institutional datasets:

- ISPRA Carta della Natura (2023 edition) for habitat classification and naturalness indices [41];

- Corine Land Cover 2023 for land-use/land-cover consistency and fragmentation patterns [42];

- Geoportale Regione Lazio for hydrography, soil, and elevation models [43];

- Roma Capitale Open Data Portal for administrative boundaries, transport infrastructure, and demographic data [44];

- Ministero della Cultura (MiC)—Sistema Informativo Territoriale for archaeological and heritage datasets [45];

- Published scientific studies and grey literature concerning vegetation, hydrology, and management of the selected sites.

To supplement these sources, visits were also made to the case studies, with direct observations and photographic surveys to verify the condition of the sites, their accessibility, any informal uses, and maintenance regimes.

The above datasets were not only collected but used purposefully to answer specific research questions. GIS layers (Carta della Natura, Corine, MiC SIT) provided the primary ecological and regulatory framework: these were consulted to identify vegetation systems and spontaneous habitats to map elements of ecological connection (wetlands, parks, allotments, residual lots, and railway strips) and to highlight archaeological constraints and landscape protection zones. These thematic maps served as the analytical backbone for comparing the three case studies and for formulating low-impact design options.

The primary GIS layers (ISPRA Carta della Natura, Corine Land Cover and MiC SIT) were not only queried but also graphically reworked to produce a reduced classification tailored to the analytical framework. This involved harmonising projections to a standard Italian cartographic projection (metric coordinate system) and generating simplified cartographic outputs used in mappings.

To ensure reproducibility, all spatial datasets underwent a standardised preprocessing workflow prior to analysis: All spatial datasets were harmonised to a standard Italian cartographic projection to ensure full alignment and comparability (ETRS89/UTM 33N) [46], then clipped to the study area and checked for topological consistency. Overlapping thematic layers were intersected to detect ecological edges and barriers, ambiguous geometries were manually verified, and patch metrics (area, contiguity, proximity to linear infrastructures) were computed using standard GIS tools.

Beyond cartographic sources, the research systematically integrated documentary and social sources: bibliographic and scientific literature on urban biodiversity and nature-based design, planning documents (Piano Territoriale Paesistico Regionale, Rome’s PRG, ZSC management plans), and grey literature—like local newspapers, association reports, blogs and social media. These non-cartographic sources were scanned to reconstruct the social uses of places, the chronology of grassroots initiatives, and undocumented management practices; they were essential to understanding stewardship dynamics but were not used as substitutes for ecological mapping.

The combined use of institutional datasets, literature and field verification allowed for the production of reproducible thematic outputs:

- habitat distribution maps;

- connectivity overlays highlighting stepping stones and barriers;

- a catalogue of institutional and bottom-up projects coded by governance actor and implementation status;

- a set of indicators (patch size, proximity to rails/greenways, degree of management) used to prioritise interventions and pilot sites.

Vegetation structure and habitat types were assessed using a combination of field inspections (2022–2024), classification of existing vegetation maps, and cross-checking with regional open-access datasets (e.g., Lazio Region, ISPRA). The analysis relied on habitat descriptors, dominant species identification and structural categories rather than full phytosociological surveys. Data processing included verification of dataset consistency, integration of layers in GIS, and cross-referencing with on-site photographic documentation.

Open-access datasets used in the analysis (Lazio Region habitat maps, ISPRA land cover layers, municipality open data) were processed through GIS to extract habitat distribution, vegetation cover, disturbance patterns and accessibility constraints. All datasets were harmonised to the same coordinate system and filtered for the 2020–2024 timeframe.

3.3. Analytical Framework

The methodology combines spatial analysis, qualitative assessment and design reasoning, integrating quantitative evidence with design-oriented interpretation to generate flexible, testable scenarios rather than fixed masterplans.

It unfolds in four steps:

Spatial identification—Mapping spontaneous vegetation, naturalness and ecological continuity. Existing GIS layers were analysed to locate stepping stones, barriers and potential corridors connecting the three case studies within the wider green network.

Connectivity analysis—Evaluating relations between spontaneous patches, parks, watercourses and infrastructures, with specific attention to rail corridors, archaeological areas and vacant lands functioning as latent ecological connectors.

Project reconnaissance—Reviewing institutional and grassroots initiatives. This included municipal and regional planning documents (PTPR, PRG, ZSC “Travertini Acque Albule” measures) and civic proposals from networks such as the Forum Territoriale per il Parco delle Energie, ArcheoGRAB, and Greenways Roma Est.

Toolkit development—Translating analytical results into a light-touch toolkit structured around the six design principles of the return-to-nature device, envisioning the three sites as nodes of a prospective Rome–Tivoli biodiversity corridor.

The workflow is iterative: mapping informs design hypotheses; prototypes guide field checks and stakeholder engagement; and pilot monitoring refines indicators and priorities. This research-by-design cycle supports adaptive management as new empirical data emerge.

The methodology operates at two nested scales:

- local/neighbourhood scale—detailed mapping, stakeholder reconnaissance and site-specific design options;

- corridor/metropolitan scale—scenario-building for the Rome–Tivoli axis to test how the three sites could act as strategic nodes within a broader greenway integrating formal parks, informal habitats and heritage sites.

The framework is best suited to urban margins and under-used post-industrial lots, where low-intensity and low-cost interventions and local stewardship are feasible. It is most appropriate in Mediterranean and temperate contexts where small-grant schemes can support adaptive management. It is less suitable for sites requiring immediate engineering remediation, for heavily contaminated land or for densely used recreational areas unless significant management resources are available. These applicability limits and the operational thresholds for pilot projects are discussed in Section 5.8.

3.4. Expected Outputs

Although the study mainly adopted a qualitative and design-oriented approach, we integrated available quantitative indicators derived from open-access datasets (ISPRA, Copernicus Land Cover) and previous ecological surveys where applicable. However, for the three selected sites, no systematic long-term monitoring programmes exist, and therefore only indicative metrics—such as habitat extent, vegetation cover types, and protected species presence—can be reported. These limitations highlight the need for future monitoring tailored to spontaneous urban habitats.

The integrated analysis produces a set of synthetic outputs, including:

- Thematic maps of spontaneous habitats and connectivity potential;

- Conceptual diagrams illustrating the six design principles in spatial form;

- A narrative scenario for the Rome–Tivoli Greenway, linking local actions to metropolitan-scale policy;

- A policy-oriented discussion proposing regulatory and management innovations.

Although not all cartographic materials are reproduced here, figure references indicate where visual documentation supports the argument. The emphasis remains on the interpretive and strategic dimension of design—translating empirical data into actionable knowledge for the transformation of the urban landscape.

4. Result

4.1. Overview of the Eastern Rome Landscape

The eastern sector of Rome displays a striking juxtaposition of infrastructures, residual green areas, archaeological sites, and spontaneous ecosystems. This heterogeneous matrix forms the spatial substrate through which the return-to-nature device can be tested.

Across the three case studies, four recurring patterns emerge:

- (a)

- High ecological value in residual zones, particularly those left unmanaged for long periods;

- (b)

- Hybridisation of natural and cultural layers, where ruins, infrastructure, and vegetation co-evolve;

- (c)

- Mismatch between formal protection boundaries and the actual distribution of priority habitats; and

- (d)

- Active civic engagement, often preceding institutional action.

These patterns indicate that Eastern Rome already contains the latent conditions for a metropolitan biodiversity network, though this potential remains only partially recognised in planning instruments.

The integrated examination of landscape configuration, morphology and vegetation across the three sites reveals how prolonged abandonment has favoured the establishment of undisturbed spontaneous vegetation whose composition is conditioned by local geomorphology and past land uses. Historical traces—industrial ruins and archaeological remains—contribute to place identity and orient uses, conservation practices and interpretive opportunities. Reviewing both institutional proposals and grassroots initiatives yields concrete low-impact scenarios for integrating these spaces into the urban green network while preserving spontaneous processes.

4.2. Ex Snia Viscosa

4.2.1. Site Genesis and Morphology

The Ex Snia Viscosa site originated as a 1930s viscose factory and was partially demolished in the 1950s. In the early 1990s, illegal excavation for an underground parking structure intersected the local aquifer, creating a permanent groundwater lake now known as Lago Bullicante [47]. The accidental emergence of water triggered a spontaneous ecological succession which over three decades has produced one of Rome’s most biodiverse enclaves. The site comprises a 7.5 ha lacustrine area legally protected as Monumento Naturale (since 2020) and approximately 5.5 ha of unprotected factory ruins colonised by xerophilous vegetation and early successional grasslands [15].

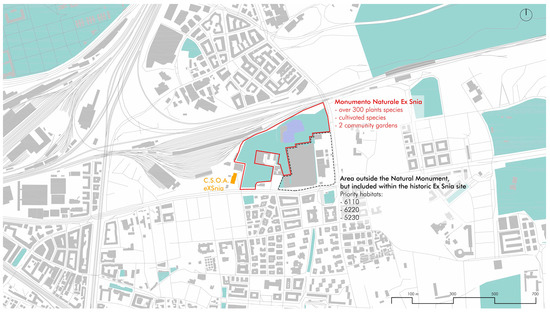

From a geomorphological perspective, subsidence linked to the Marranella ditch and local tectonic conditions produced a lowering of the eastern sector that favoured the reappearance of groundwater and the formation of the lake. The surrounding forest belt—dominated by native Salix spp., Robinia pseudoacacia and Populus spp.—performs key ecosystem services, notably filtering pollutants that would otherwise run into the lake [48]. Around the lake, a multispecific meadow persists (Avena sterilis, Bromus diandrus, Veronica persica, Trifolium campestre, Securigera varia) and acts as an important floristic reservoir for the site [15] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Some of the areas of the former Ex Snia site: (a) Bullicante Lake and the surrounding woodland belt; (b) the area around the former factory ruins, characterised by a rich and compelling ecosystem despite its exclusion from the “Monumento Naturale” designated in 2020 (Photo source: Lisbet A. Ahon Vasquez).

4.2.2. Vegetation Structure and Habitats

Phytosociological surveys identify multiple habitat types:

- Riparian woodland dominated by Salix alba, Populus nigra, and Robinia pseudoacacia;

- Hydrophytic belts with Phragmites australis, Typha latifolia, and Cladium mariscus;

- Ruderal grasslands on rubble and compacted soils, featuring Avena sterilis, Bromus diandrus, Trifolium campestre, and Securigera varia [5];

- Thermophilous shrub and pioneer tree communities (Pinus halepensis, Rhamnus alaternus) on concrete debris.

According to Fanelli [38], at least three priority habitats of the Habitats Directive (6110, 6220, 5230) occur within this mosaic. The resulting diversity provides refuge for over 350 plant species and numerous invertebrates and birds, including the European bee-eater (Merops apiaster) and the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis).

Importantly, the factory ruins that lie outside the Monumento Naturale delineation host particularly distinctive Mediterranean assemblages (e.g., Pinus halepensis, Rhamnus alaternus) and xerophilous herbaceous communities (Trifolium scabrum, Hypochoeris achyrophorus) on anthropic substrates (Figure 3). These neo-formations behave ecologically like coastal cliffs in terms of species turnover and conservation value, thereby representing local botanical refugia with concrete potential for targeted protection and light-touch design interventions [38].

Figure 3.

The Ex Snia site—Habitat types and spatial structure. The map highlights the area designated as a Monumento Naturale (2020), which hosts over 300 plant species, and the adjacent portions of the Ex Snia area where priority habitats 6110, 6220 and 5230 were recorded. Data derived from ISPRA, Corine and Geoportale Regione Lazio GIS layers and subsequently reworked by the authors (drawing and GIS processing by the authors).

4.2.3. Ecosystem Functions and Social Use

The lake and surrounding vegetation deliver crucial ecosystem services: storm-water retention, microclimate regulation, carbon sequestration, and habitat provision. Moreover, Ex Snia operates as a civic common. Since the early 2000s, community groups such as Forum Territoriale per il Parco delle Energie and Csoa eXSnia have organised educational programmes, ecological monitoring, and low-impact interventions. These activities exemplify the co-stewardship principle, proving that social participation can reinforce ecological outcomes without heavy capital investment.

Local activism has delivered a suite of low-cost, high-value interventions—from self-built benches and interpretation panels to a community apiary (“Api per il Lago” project) [49]—which function as small-scale demonstration projects for ecological education and species support, showing how civic-led initiatives can complement formal protection measures [50].

4.3. Parco Della Serenissima

4.3.1. Geomorphology and Hydrology

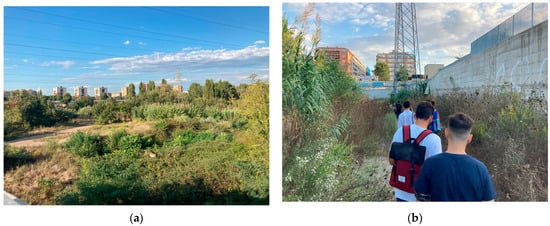

Located between the A24 motorway and the Rome–Pescara railway and high-speed line to Naples, Parco della Serenissima extends over approximately 40 ha on a volcanic tuff and pozzolana substrate (Figure 4). Along the eastern edge, springs emerging from these deposits generate a riparian–hygrophilous woodland characterised by Salix alba, Populus alba, Alnus glutinosa, Ulmus minor, and Fraxinus oxycarpa, while the wetland margins host reed and sedge belts (Phragmites australis, Arundo donax, Scirpus holoschoenus), which stabilise soils and enhance infiltration [16,51]. Morphologically, the site displays a clear west–east gradient with marked dislevelments linked to tuff and pozzolana deposits; the same springs surfacing east of Viale della Serenissima have also sustained localised hygrophilous communities and a small-scale agricultural imprint still visible in the vegetation mosaic [16].

Figure 4.

Parco della Serenissima area—Planned park boundary and current condition. The map outlines the area designated for the proposed Parco della Serenissima (plan not yet implemented) and indicates its present state of neglect; note the immediate proximity and potential ecological continuity with the Ex Snia site. Data sources: Geoportale Regione Lazio (2023), ISPRA Carta della Natura (2023), Corine Land Cover (2023) [41,42,43] (drawing and GIS processing by the authors).

4.3.2. Cultural and Archaeological Stratification

The park’s ecological features are interwoven with significant heritage layers. Within its boundaries lie:

- A 150 m segment of via Collatina, a Roman consular road;

- A necropolis of approximately 2500 burials;

- A subterranean section of the Aqua Virgo aqueduct.

This coexistence of archaeology and spontaneous nature produces a hybrid condition where cultural preservation and ecological regeneration can reinforce one another—a practical example of interpretive minimalism as a design principle.

These heritage constraints both limit intrusive interventions and provide interpretive frameworks that can be leveraged to protect spontaneous habitats. Archaeology here offers an opportunity: protected strata reduce disturbance and therefore act—de facto—as biodiversity refuges, while also enabling low-impact public engagement through informed interpretation and minimal infrastructural insertion [16] (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Selected points in the Parco della Serenissima area: (a) abandonment has enabled the emergence of a distinctive ecosystem, notably a hygrophilous riparian woodland on the north-facing slope; (b) the site’s severe neglect and frequent degradation render it neither easily accessible nor usable. The photograph depicts a site visit by students on the “Urban and Landscape Design Studio” course (MArch in Architecture, taught by Professor A. Capuano) during the 2021–2022 academic year, which focused specifically on Parco della Serenissima (Photo source: Lisbet A. Ahon Vasquez).

4.3.3. Informal Practices and Civic Appropriation

Despite its ecological and heritage value, the site remains largely unplanned. Residents have created informal gardens and footpaths, adding a social layer to the existing ecology. These light interventions—fencing, raised beds, and shared maintenance—illustrate how informal uses can coexist with spontaneous vegetation, diversifying structure and function.

A municipal feasibility plan (2020) [16] proposes transforming the area into a public park emphasising archaeology, tree planting, regulated gardens, and cycling connections with the Grande Raccordo Anulare delle Biciclette (GRAB). Parallel initiatives, such as Parco LineaRE [52] and ArcheoGRAB [53], envision Serenissima as a gateway node for a continuous Greenway Roma Est.

It is important to note that open-source vegetation mapping for Serenissima is incomplete; this data paucity constrains precise ecological assessment and should be addressed by targeted field surveys before large-scale interventions are implemented.

4.4. ZSC “Travertini Acque Albule”

4.4.1. Geology and Ecological Structure

The “Travertini Acque Albule” area forms part of a unique hydro-geological system of travertine terraces and thermal springs. Vegetation analysis identified a gradient of communities:

- Rocky and shrubby formations on ancient travertine surfaces;

- Pioneer crusts of mosses, lichens, and annual herbs on neo-formed travertine;

- Hygrophilous belts around springs, dominated by Phragmites australis, Cladium mariscus, Juncus inflexus, and Typha latifolia [54].

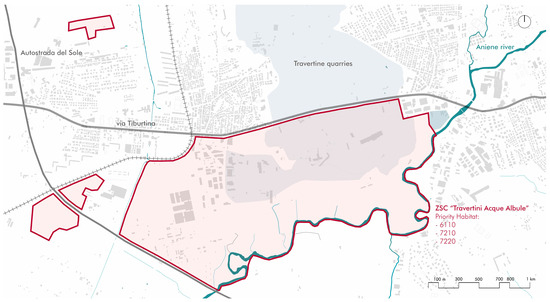

Travertine microtopography promotes pioneer cryptogamic crusts (mosses and lichens) and specialised annual microfloras on recent travertine deposits; edaphic variability and microclimatic heterogeneity foster a mosaic of rocky scrub, pioneer communities, and hydrophilous assemblages that include rare and protected taxa [55] (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The richness and distinctiveness of the vegetational system of the ZSC “Travertini Acque Albule”: (a) the photograph captures the area near the north-east boundary of the ZSC, where a flowering of Linaria purpurea (L.) Mill. and the presence of Chrysopogon gryllus (L.) Trin., a rare grass species, can be observed (Photo source: Sara Radi Ahmed); (b) the “Montarozzo del Barco”, a small artificial hill composed of travertine quarry waste, situated in the south-east of the ZSC, adjacent to the ancient Roman Barco quarry. Despite its diminutive size, the mound has revealed a high floristic richness, notably including Iberis pinnata L., an extremely rare species in Lazio (Photo Source: Lisbet A. Ahon Vasquez).

4.4.2. Habitat Distribution and Boundary Mismatch

Conservation documents identify four priority habitats (6110, 6220, 7210, and 7220) yet empirical mapping shows a marked discrepancy: these habitats occupy only the 6.8% of the official Zona Speciale di Conservazione (ZSC) area, while over 100 ha of equivalent ecological value lie outside the current perimeter [40] (Figure 7). This misalignment exposes a critical policy gap between formal protection and actual biodiversity distribution.

Figure 7.

ZSC “Travertini Acque Albule”—Protected area boundary and adjacent land uses. The map shows the ZSC extents and surrounding land uses, including the nearby motorway, railway corridor and industrial zones, as well as extensive travertine quarries within the landscape. Habitat mosaics and quarry extents were derived from ISPRA Carta della Natura (2023), Corine Land Cover (2023) and Geoportale Regione Lazio (2023) [41,42,43] datasets and subsequently reworked by the authors; field verification 2023 (drawing and GIS processing by the authors).

The evidence that priority habitats extend well beyond the formal ZSC boundary provides a clear operational signal: management and legal frameworks should be revised so that protection reflects ecological reality rather than administrative delineation [40].

4.4.3. Pressures and Governance

The site suffers from illegal waste dumping, uncontrolled vehicle access, and fragmented jurisdiction between regional, municipal, and private entities. Despite these challenges, local associations such as Comitato Parco Pubblico Travertino advocate for an expanded archaeological-environmental park that would integrate natural and cultural heritage while improving accessibility through pedestrian and cycling paths [56].

Citizen-led proposals for an extended archaeological-environmental park emphasise inclusive access (cycle and pedestrian routes) and the need to consider habitat patches lying beyond the statutory boundary—a bottom-up vision that can inform boundary revision and park design [56].

4.5. Archaeology and Spontaneous Habitats: Cross-Case Synthesis

The analysis confirms that archaeological contexts in Rome act as unintentional biodiversity reserves, due to their restricted access and low management intensity [37,57]. Across all three sites, ruins, excavations, and infrastructural relics serve as micro-habitats and ecological connectors.

At Ex Snia, industrial archaeology coexists with lacustrine ecology, producing a new form of civic wilderness. At Serenissima, the coexistence of necropolis, ancient roads and spontaneous woodland creates a palimpsest landscape where historical and ecological layers remain jointly legible. In the case of ZSC “Travertini Acque Albule”, quarry voids, casali, and Roman bridges structure a continuum of travertine biotopes.

These findings indicate that Rome’s archaeological heritage can be understood as a structural component of its biodiversity network, supporting the interpretive-minimalism and succession-window principles of the design device. Comparative floristic studies across Mediterranean archaeological areas show that protected heritage grounds often host species of conservation interest, reinforcing the need to align heritage protection with biodiversity objectives at the landscape scale.

4.6. Existing Initiatives and Emergent Scenarios

Multiple bottom-up and institutional projects already point toward an integrated ecological corridor. At Ex Snia, civic stewardship initiatives have stabilised habitats and generated social value, functioning as a prototype of co-governance [14]. At Serenissima, the alignment of municipal and academic visions—through the GRAB and Greenway Roma Est—lays the foundation for corridor continuity [58]. At ZSC “Travertini Acque Albule”, proposals for an extended park demonstrate that even peripheral Natura 2000 sites can anchor broader ecological strategy [56].

Historically, interventions have often been intermittent and under-resourced. Ex Snia exemplifies “unintended restoration”: spontaneous ecological recovery coupled with civic activism (Csoa eXSnia, Stalker, etc.) and small-scale practical interventions—signage, benches, apiary projects—that collectively produce durable social-ecological benefits without major investment. These grassroots practices often articulate a more coherent corridor logic than some institutionally bounded proposals, indicating the need for governance that can integrate bottom-up initiatives with formal planning.

Synthesising these efforts, the research proposes a Rome–Tivoli Greenway connecting the three nodes through rail corridors, waterways, and abandoned lots. The corridor would employ differential maintenance (mosaic mowing, succession phases), low-impact access (raised walkways, seasonal closures), and shared governance agreements between municipal departments, regional authorities, and civic networks.

4.7. Key Findings in Relation to the Six Design Principles

To clarify how the six operational principles translate into practice, Table 1 synthesises the key empirical findings from the three sites and outlines the corresponding spatial and operational implications.

Table 1.

Key findings linking each of the six design principles of the return-to-nature device to the corresponding empirical evidence and their spatial/operational implications.

These principles operate at a strategic and conceptual level. Their translation into detailed technical solutions, drawings or material specifications requires site-specific design development and is beyond the scope of this study.

4.8. The Return-to-Nature Device

The combined evidence demonstrates that Rome’s spontaneous and unplanned landscapes already function as ecological, social, and cultural infrastructures. When interpreted through the return-to-nature device, they reveal replicable strategies for urban transformation:

- Ecologically, they enhance connectivity and climate resilience.

- Economically, they offer low-maintenance solutions compatible with limited public budgets.

- Socially, they foster stewardship and environmental literacy.

These results confirm the operational relevance of the six design principles and validate the Eastern Rome corridor as a model for process-based urban landscape design.

The floristic and geomorphological characteristics observed across the three sites indicate broad opportunities: conservation of priority habitats, reinforcement of ecological corridors, light renaturalisation measures, and green infrastructure interventions compatible with archaeological and industrial residues. Crucially, many bottom-up experiences express a system-level vision that institutional projects should acknowledge and incorporate into corridor-scale governance and design.

A cross-case comparison was developed in Table 2 to identify shared challenges and site-specific conditions influencing the applicability of the six operational principles.

Table 2.

Comparative assessment of the three case studies (ecological constraints, opportunities, governance, challenges, social dynamics, maintenance regimes).

Although the three sites differ significantly in morphology, governance structures and levels of public accessibility, they also reveal a set of recurrent socio-spatial patterns that influence the implementation of the return-to-nature principles. Ex Snia demonstrates how strong civic stewardship can guide low-maintenance ecological processes, while Parco della Serenissima illustrates the challenges of fragmented governance and low community engagement. The ZSC Travertini Acque Albule shows how protected sites with complex ownership structures require multi-level coordination rather than purely volunteer-driven models.

However, the study does not systematically analyse the organisational mechanisms behind these forms of stewardship, nor the conflicts, negotiations, or motivations that shape participation in each context. These limits point to the need for future research on the social dynamics that condition the success of nature-based design approaches.

Table 2 synthesises the key ecological, cultural, social and governance characteristics of the three case studies, highlighting similarities and differences that influence the applicability of the six operational design principles. It clarifies how each site presents distinct challenges and opportunities and how these variations inform the implementation of the return-to-nature device across different contexts. Taken together, the cases form a complementary gradient: Ex Snia demonstrates the potential of civic wilderness and co-stewardship; Serenissima illustrates the constraints and opportunities of archaeological–ecological palimpsests; and the ZSC Travertini Acque Albule represents the landscape-scale potential of spontaneous habitats within a protected setting. These differences provide important guidance for adapting the six design principles to diverse Mediterranean urban conditions.

5. Discussion

5.1. From Ecological Restoration to Design Transition

The results show that spontaneous and informal habitats can assume a structural role in urban biodiversity networks, provided that design and policy frameworks evolve to support them. In this sense, the return-to-nature device represents not a romantic regression but a design transition—a deliberate shift from restoration to co-evolution between human and non-human systems.

Traditional restoration seeks to recreate past ecological conditions, typically through intensive intervention and maintenance [59]. In contrast, process-based design works with contemporary ecological dynamics, recognising that post-industrial soils, altered hydrologies and spontaneous vegetation can sustain new forms of biodiversity and beauty [60].

In this perspective, design does not impose equilibrium but orchestrates conditions for adaptation. As Ahern [7] and Prominski [61] argue, resilient landscapes embrace uncertainty, enabling self-organisation and feedback. The return-to-nature framework contributes to this discourse by providing an operational grammar—a set of repeatable principles for translating resilience theory into spatial practice.

The application of return-to-nature principles also involves trade-offs, such as balancing ecological protection with public accessibility, and addressing safety concerns in minimally managed environments. Such tensions require adaptive management and clear communication with local communities.

5.2. Spontaneity as Infrastructure

The case studies reveal that spontaneous habitats already perform infrastructural functions: water retention, heat mitigation, soil regeneration, and pollinator support. Recognising these capacities challenges the binary distinction between planned infrastructure and waste ground. Instead, these environments embody what Corner [4] and Waldheim [6] conceptualised as Landscape Urbanism: a mode of city-making in which ecological processes rather than architecture, act as the organising medium.

In Rome, these readings gain particular resonance. The city’s archaeological topography and hydrogeological structure create conditions in which time and ecology overlap. The Ex Snia and ZSC “Travertini Acque Albule” sites demonstrate that spontaneous nature can reactivate obsolete infrastructures, converting them into ecological corridors and cultural catalysts. Such reinterpretations align with global trends toward green-infrastructure planning [62,63], while foregrounding context-specific design intelligence rooted in local history.

Empirical evidence from the study areas further shows how hydraulic and geomorphological specificities enable spontaneous ecosystems to deliver measurable services—stormwater detention, infiltration enhancement and microclimatic buffering—that can be integrated into infrastructure planning. Understanding these functions as components of the metropolitan green infrastructure allows low-cost, high-benefit interventions to complement or replace more expensive engineered solutions.

Yet recognising spontaneous habitats as infrastructural assets calls for a clear assessment of their trade-offs. Ecosystem-service deliver may conflict with expectations for safe and equitable public access and can be undermined by aggressive colonising or non-native species if left unmanaged. Low-intervention regimes therefore require explicit governance arrangements: clear zoning of areas prioritised for ecological functions, assigned monitoring responsibilities, and predefined intervention triggers to address safety or ecological dominance—measures that ensure adaptive stewardship rather than a one-size-fits-all prescription.

5.3. Governance and Co-Stewardship

A major outcome of the research is the recognition that social dynamics are as crucial as ecological ones. At Ex Snia, the community-driven management model illustrates how co-stewardship can sustain both ecological and civic value. These practices resonate with the growing literature on commons-based urban governance [64], where residents and institutions share responsibility for the care of public assets.

Such arrangements challenge conventional top-down management, instead promoting distributed maintenance and adaptive governance [65]. They also provide financial advantages: when local actors contribute labour, monitoring, and decision-making, public costs decrease while ecological quality often improves. This insight echoes the principles of Elinor Ostrom’s [66] work on common-pool resources, demonstrating that collective action can achieve stability without centralised control.

To institutionalise this potential, urban policies must evolve beyond ownership categories. Flexible memoranda of understanding, micro-grant schemes, and neighbourhood charters can formalise civic care while maintaining ecological spontaneity. The “return-to-nature” device thus implies not only a design method but a governance model, in which participation becomes a means of ecological regeneration.

Specific mechanisms observed locally include volunteer-led monitoring, community apiaries, and ad hoc maintenance teams (e.g., Csoa eXSnia activities) that provide regular stewardship at near-zero public cost. Formalising such practices would scale civic involvement while reducing municipal burdens and improving ecological outcomes.

5.4. The Role of Heritage in Ecological Transition

The coexistence of heritage and ecology in Rome provides fertile ground for a new interpretation of the landscape continuum. Archaeological areas, often subject to strict protection, inadvertently function as refuges for biodiversity [37]. Rather than treating these zones as static monuments, the return-to-nature approach suggests understanding them as living archives where environmental and cultural processes intertwine.

This perspective resonates with Spirn’s [2] notion of urban nature as heritage, and with the Mediterranean discourse on cultural ecology. It also aligns with the principles of the European Landscape Convention (2000), which encourages the recognition of ordinary and evolving landscapes as part of cultural identity.

By integrating ecological management into heritage conservation, cities like Rome could pioneer a new type of eco-archaeological infrastructure, where maintenance activities simultaneously preserve cultural layers and foster natural succession. In this sense, the city’s historical depth becomes not an obstacle but a catalyst for biodiversity planning.

Practically, this means that conservation strategies for archaeological sites can be reinterpreted to include controlled, conservation-compatible ecological processes: limited access regimes, selective stabilisation of ruins, and interpretive trails that promote understanding while protecting habitats. Such an approach turns heritage management into an instrument for biodiversity protection rather than a competing objective.

5.5. Policy Implications for Italian and European Cities

The findings hold significance beyond Rome, as many Mediterranean and European cities face similar conditions—fragmented green systems, abandoned industrial land and limited maintenance budgets. The return-to-nature device offers an adaptable framework for these contexts.

At the European scale, the approach aligns with the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 and the Nature Restoration Law (2024) [67], both promoting urban biodiversity enhancement and green-infrastructure connectivity. In Italy, it complements the Strategia Nazionale per la Biodiversità 2030 and the Piano Nazionale Ripresa e Resilienza PNRR, which include funding lines for urban forestry and ecological corridors [31].

Moving from quantitative (e.g., number of trees planted) to qualitative targets (e.g., diversity, connectivity, resilience) is essential. Integrating spontaneous habitats into official plans would enhance functional diversity, reduce costs and strengthen climate-adaptation objectives. Municipalities could embed the six return-to-nature principles into:

- design briefs for new parks and regeneration areas;

- maintenance contracts adopting differential and adaptive regimes;

- educational programmes that foster ecological literacy;

- monitoring frameworks linking biodiversity indicators with social well-being metrics.

Operationalising this shift requires statutory recognition of spontaneous habitats supported by pragmatic tools: mapping informal corridors in Piano di Governo del Territorio (PGT) or Piano Regolatore Generale (PRG) revisions; including procurement and maintenance clauses that reward ecological performance rather than routine tasks; and formalising local partnerships through standardised memoranda of understanding (MoU). Municipal biodiversity plans in Paris, Barcelona and London demonstrate how city-scale strategies can provide normative frameworks for recognising and protecting spontaneous habitats; in Italy, the Piani Comunali del Verde could serve a similar function. Small-scale financing (micro-grants) can activate community stewardship, while pilots should follow a clear sequence-diagnostic mapping, soil screening, temporary designation or MoU, targeted funding calls, adaptive-maintenance contracts and independent monitoring.

These policy shifts could be tested through pilot corridors—such as the proposed Rome-Tivoli Greenway—where EU and national funding streams specifically support governance innovation, adaptive maintenance and community stewardship, demonstrating cost-effective multifunctionality at the corridor scale.

5.6. Socio-Economic and Governance Factors

Implementing low-maintenance, process-based landscapes also depends on economic feasibility and governance structures. Across the three sites, funding mechanisms range from municipal programmes to community-managed activities, though detailed cost data are not available. Nevertheless, our assessment indicates that differential maintenance regimes reduce operational costs compared with conventional high-input urban green spaces, aligning with evidence from comparable Mediterranean cities.

5.7. Operational Guidance for Applying the Six Design Principles

To address the need for clearer technical implementation raised in the review process, this section outlines practical methods, low-impact construction techniques, and maintenance protocols that translate the six principles into replicable design actions in Mediterranean urban contexts.

- Access by least impact—Use removable or elevated structures (e.g., galvanized-steel grate walkways, chestnut-wood boardwalks, or recycled-plastic planks) placed on micro-piles or screw anchors to avoid soil sealing. Seasonal closures can be implemented with rope fencing and lightweight signage.

- Differential maintenance—Mosaic mowing can be performed with brush-cutters or walk-behind flail mowers, leaving 20–30% of patches unmanaged on a three-year rotation to maintain structural heterogeneity. “Cut-and-lift” cycles reduce nutrient accumulation and favour native dry-grassland species.

- Succession windows—Rotating no-intervention sectors can be designated using simple pin markers in GIS management plans; recommended window duration ranges from 18 to 36 months depending on soil fertility and disturbance regimes typical of Mediterranean climates.

- Interpretive minimalism—Signage can rely on QR-based digital interpretation rather than permanent panels; materials should be low-impact (corten, untreated wood). Small-scale wayfinding can follow reversible anchoring to avoid disturbance in archaeological contexts.

- Co-stewardship—Maintenance agreements can be structured around micro-tasks (monitoring, selective cleanup, invasive control) assigned to community groups, using municipal micro-grant schemes (1–5k €/year).

- Adaptive monitoring—A lightweight protocol can focus on 4–5 indicators (species richness, canopy cover, ground permeability, presence/absence of invasive species, user satisfaction), updated annually through combined municipal–citizen monitoring.

5.8. A Design Grammar for Adaptive Urbanism

From a disciplinary standpoint, the return-to-nature device contributes to the evolution of landscape design theory. It synthesises insights from ecological urbanism [68], landscape as infrastructure [6], and biophilic design [1], but grounds them in the pragmatic realities of Mediterranean cities.

By operationalising spontaneity, the framework challenges the aesthetic dominance of control and order in urban greening. Instead, it promotes aesthetic diversity and temporal awareness—qualities that reflect ecological health and cultural plurality. As Musacchio (2009) [5] observed, sustainable landscapes must engage both ecological processes and human perception. The return to nature transforms this principle into an actionable toolkit, making resilience visible and experiential.

Furthermore, by recognising time as a material of design, the framework aligns with Ahern’s [7] and Prominski’s [61] call for safe-to-fail systems that evolve through experimentation. This perspective reframes maintenance as a creative practice, where adaptation and care replace perfection and permanence.

Designers are thus invited to produce stimuli—thresholds, interpretive nodes, differential mowing regimes. These stimuli catalyse ecological processes while offering legible experiences for people, enabling both biodiversity enhancement and meaningful engagement.

5.9. The Mediterranean Specificity

While international rewilding discourse often originates from northern and Atlantic Europe, Mediterranean contexts demand a nuanced approach. Here, water scarcity, fire risk, and cultural layering create unique constraints and opportunities. The Eastern Rome corridor illustrates how rewilding can be selective and adaptive, combining dry grasslands, ruderal species, and heritage sites within the same ecological mosaic.

Such an approach values ecotones—edges between habitats—as drivers of biodiversity. It also accepts that Mediterranean “wildness” is historically co-produced by centuries of human use [69]. Thus, the return-to-nature device reframes rewilding not as abandonment but as curated coexistence, balancing autonomy and care.

This interpretation resonates with emerging Mediterranean research on productive landscapes, temporary ecologies [70], and climate-sensitive design [71]. It suggests that the cultural dimension of design—its ability to narrate coexistence—remains crucial to achieving resilient and inclusive urban transitions.

5.10. Limitations and Further Research

This study presents several limitations, which also indicate directions for future research.

First, although the analysis identifies ecological structures, governance patterns and spatial dynamics, it does not quantify biodiversity trajectories, ecosystem-service delivery or maintenance-cost differentials. Such metrics require long-term monitoring and standardised datasets.

Second, socio-economic and governance aspects—including cost–benefit relations, funding mechanisms and levels of community acceptance—remain only partially addressed due to heterogeneous institutional responsibilities across the three sites.

Third, while civic engagement is recognised as a key factor, the study does not analyse how community groups mobilise, negotiate responsibilities or manage conflicts. Dedicated social research would be essential to understand stewardship dynamics.

Fourth, the investigation relies mainly on present-day observations. Successional trajectories at Ex Snia, Parco della Serenissima and the ZSC “Travertini Acque Albule” require longitudinal ecological and social datasets to detect thresholds and temporal transitions.

Fifth, although the paper outlines strategic policy directions, it does not provide detailed operational tools—such as sample design briefs, maintenance templates or governance protocols—that municipalities could directly adopt. Developing such templates is a crucial next step.

Sixth, applying spontaneous-vegetation approaches involves operational risks that require explicit assessment and safeguards:

- Ecological risks: spontaneous vegetation may favour invasive or highly competitive species (e.g., Ailanthus altissima, Robinia pseudoacacia), leading to potential homogenisation. Monitoring protocols with predefined intervention thresholds are necessary.

- Soil and contamination risks: uncertain soil histories require preliminary screening for heavy metals or hydrocarbons before public access or unmanaged succession is permitted.

- Public safety risks: uneven terrain, concealed obstacles and seasonal fuel loads can increase accident and fire risk, necessitating managed access, regular inspections and targeted fuel-reduction measures.

Addressing these limitations and risks is fundamental to defining realistic expectations and ensuring appropriate application of the return-to-nature framework.

Future work should advance the framework along three main fronts:

- Quantitative ecological assessment, linking biodiversity indicators and ecosystem services to maintenance regimes;

- Participatory co-design, testing co-stewardship frameworks and adaptive management in pilot projects;

- Comparative studies across Mediterranean cities (e.g., Palermo, Bologna, Athens) to evaluate transferability under different regulatory and governance conditions.

Mixed-methods approaches integrating ecological sampling, remote-sensing metrics and user surveys would provide the empirical basis needed to refine maintenance protocols, assess ecological performance and evaluate socio-economic feasibility.

6. Conclusions

The discussion confirms that the return-to-nature device functions simultaneously as:

- A design grammar, enabling landscape architects to work with spontaneity;

- A governance tool, fostering shared responsibility;

- A policy framework, supporting EU and national biodiversity strategies.

By combining ecological process, cultural continuity, and social participation, this approach outlines a path toward adaptive urbanism—a city form that learns, evolves, and regenerates through its living landscapes. Overall, the evidence suggests that embracing spontaneous habitats within a coherent design-governance toolkit yields high ecological and social returns at modest cost—a particularly relevant proposition for Mediterranean cities facing budgetary constraints and complex heritage landscapes.

This study proposes the “return-to-nature” as a design device—a conceptual and operational framework for guiding landscape transformation in contemporary cities. Drawing on three case studies in Eastern Rome, the research shows that spontaneous and informal habitats can function as resilient, low-maintenance ecological infrastructure when reframed through six interconnected principles: access by least impact, differential maintenance, succession windows, interpretive minimalism, co-stewardship, and adaptive monitoring. These principles translate ecological theory into actionable design guidance.

The device can be implemented through existing planning and regulatory instruments. Municipal design briefs may require minimal-impact access and differentiated maintenance; landscape guidelines can mandate reversible installations in archaeologically sensitive areas; and maintenance contracts can incorporate adaptive cycles linked to ecological indicators. Such mechanisms provide feasible routes for embedding process-based design within current planning and conservation frameworks.

The three case studies highlight how spontaneous vegetation and cultural heritage can form a continuous ecological–cultural fabric: the civic wilderness of Ex Snia sustained by community stewardship; the archaeological–ecological palimpsest of Parco della Serenissima; and the peri-urban reserve of the ZSC “Travertini Acque Albule”, where spontaneous processes extend beyond administrative boundaries. Together, they demonstrate that urban nature is an integral—rather than marginal—component of ecosystem functioning and urban identity.

The findings also underscore the need for lightweight instruments to support implementation, including pilot projects testing succession windows and differential maintenance; monitoring protocols linking indicators to management decisions; and governance tools such as micro-grants, memoranda of understanding, or neighbourhood agreements that formalise civic stewardship.

Although focused on Rome, the framework is transferable to other Mediterranean—and non-Mediterranean—cities characterised by fragmented landscapes, budgetary constraints, and layered historical ecologies. Future research should test this transferability through comparative case studies, co-design processes, and mixed-methods ecological and social monitoring capable of refining maintenance regimes and evaluating ecosystem services.

The approach is not suited to sites requiring heavy engineering remediation, severely contaminated soils, or highly programmed recreational spaces with intense public use. Recognising this scope prevents inappropriate applications and supports realistic expectations for pilot projects. Modest investments in facilitation, monitoring, and community support can, however, generate disproportionate ecological and social returns. The return-to-nature device thus emerges as both principle and practice—an invitation to reconceive the city as an adaptive socio-ecological system capable of regenerating through its spontaneous and emergent processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, L.A.A.V. and A.C.; methodology, A.C.; formal analysis, L.A.A.V.; investigation, L.A.A.V.; resources, L.A.A.V.; data curation, L.A.A.V.; writing—original draft preparation, L.A.A.V. and A.C.; writing—review and editing, L.A.A.V. and A.C.; visualisation, L.A.A.V.; supervision, A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research results presented here were developed within two interrelated projects on the conservation of urban biodiversity and cultural heritage at the Department of Architecture and Design, under co-Principal Investigator (co-PI) Prof. Alessandra Capuano: (1) Project “Biodiversità Urbana” UNIROMA 1 Spoke 5, coordinated by Prof. Giulia Capotorti, Department of Environmental Biology, within the CENTRO NAZIONALE BIODIVERSITÀ as part of the Italian National Recovery and Resilience Plan (Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza, PNRR), Mission 4 “Education and Research”, Component 2, Investment 1.4; funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU—Project code CN00000033—CUP H43C22000530001, Project title ‘National Biodiversity Future Centre—NBFC’. Sapienza CUP: B83C22002950007; (2) Project “Itinerari del sacro lungo l’Aniene” UNIROMA 1 Spoke 1, coordinated by Prof. Orazio Carpenzano, Thematic Line 1 within the PARTENARIATO ESTESO CHANGES PE5 SPOKE 1—“Historic Landscapes, Traditions and Cultural Identities”, Spoke leader: University of Bari “Aldo Moro” Prof. Giuliano Volpe; part of the Italian National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR), Mission 4 “Education and Research”, Component 2, Investment 1.4; funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU—CUP: B53C22003780006.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: https://www.comune.roma.it/web/it/dati-e-statistiche.page, accessed on 25 October 2025.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, version GPT-5 Thinking mini) to assist with rephrasing and reorganising the sequence of paragraphs and support the interpretation of the acquired data. The authors reviewed and edited all outputs generated by the tool and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Beatley, T. Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]