Abstract

The article’s main focus is on identifying the key enablers that are making Industry 4.0 adoption easier, utilizing structural equation modeling via SPSS version 26. A comprehensive examination of previous studies led to the identification of 10 main enablers and 35 associated sub-enablers. Data collected from 182 manufacturing companies in India, selected by simple random sampling, was used for quantitative research. The analysis basically depends on PLS-SEM and CB-SEM (Partial Least Squares and Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modeling) path modeling. The findings indicate that technological enablers such as data analytics and artificial intelligence, computational power and connectivity, technologies that integrate physical and digital systems, and other enabling technologies are crucial to Industry 4.0 adoption. Additionally, organizational enablers (including a supportive organization, government efforts and promotions, and human resources) are also found to be significant contributors to Industry 4.0 implementation. Additionally, the study identified a significant mediating effect between technological and organizational enablers, emphasizing the importance of collaborative visualization mechanisms, established through bootstrapping with bias-corrected confidence intervals. Strengthening technological, organizational, and collaborative capabilities through Industry 4.0 adoption allows firms to attain improved operational performance while advancing sustainability objectives. These results contribute to the present understanding of Industry 4.0 adoption by offering useful implications for policymakers and industry practitioners. These insights guide managers and policymakers in structuring digital transformation initiatives.

1. Introduction

Industry 4.0 represents a technology-driven, highly flexible industrial environment where machines communicate, self-learn, and self-optimize in real time to enhance performance. The rapid growth of sensors, data analytics, computational power, and connectivity over the past decade has accelerated its adoption. While the term Industry 4.0 originated in Europe, smart manufacturing is more common in North America, and digital manufacturing is often used interchangeably. Beyond improving productivity and competitiveness, Industry 4.0 also promotes sustainable production and responsible consumption. Through the integration of cyber-physical systems, IoT, and data analytics, it enables efficient resource use, waste reduction, and circular economy practices. When effectively deployed, these technologies foster transparency, predictive maintenance, and data-driven decision-making, aligning digital transformation with sustainability and policy objectives. The industrial domain is swiftly progressing beyond Industry 4.0 toward the paradigms of Industry 5.0 and the emerging Industry 6.0. Contemporary research emphasizes this shift from purely automated and digitalized operations to systems that are human-centered, sustainable, and intelligent, integrating advanced artificial intelligence, resilience, and dynamic human–machine collaboration. Türkeș et al. [1] found that customer demands, competitor strategies, cost efficiency, faster time-to-market, and regulatory requirements were key motivators for Romanian SMEs to implement Industry 4.0, utilizing correlation analysis with SPSS. Additionally, Cater et al. [2] examined how internal efficiencies, external legitimacy, and accessible resources and capabilities impact Industry 4.0 adoption in practice, employing structural equation modeling (SEM) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Gadekar et al. [3] investigated how Industry 4.0 enablers and sustainable organizational performance relate to one another using a quantitative, data-driven approach. For data analysis, the study used structural equation modeling (SEM) and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS).

Key enablers identified included aspects such as organizational strategies, Industry 4.0 technologies, financial investments, established standards, and the integration of intelligent products and operations. Using SEM in SPSS Version 26 to identify the causal pathways and intricate connections between the variables, this study evaluated both measurement and structural models [4]. SEM, as a statistical tool, enables testing of hypotheses by modeling structural relationships among observed and latent variables, thus clarifying the underlying causal mechanisms [5]. Digital twins enhance Industry 4.0 through simulation and optimization but pose major cybersecurity risks. Vulnerabilities in infrastructure, data privacy, IoT/IIoT (Internet of Things/Industrial Internet of Things) devices, and interconnectivity, along with supply chain threats and skills gaps, make security a critical challenge in its adoption [6]. Major barriers include cybersecurity risks, weak infrastructure, poor data quality, lack of certification standards, limited IT support, low managerial involvement, resistance to change, and outdated data [7]. The electrical and electronics sector in Malaysia faces major barriers to Industry 4.0 adoption, including cybersecurity risks, limited government support, shortage of skilled talent, poor digital readiness, and weak infrastructure. The most critical challenges are skill shortages, lack of funds for technology upgrades, and insufficient business justification for investment [8]. Key challenges to Industry 4.0 adoption in the Indian automobile sector include outdated infrastructure, lack of skilled awareness, resistance from leadership, and high implementation costs. The fuzzy-DEMATEL analysis further revealed their ranking and causal interrelationships [9]. Digital manufacturing faces challenges such as high costs, resistance to change, cybersecurity risks, lack of digital skills, and workforce reskilling needs. This study highlights its trends, barriers, opportunities, and impact on industrial processes [10]. Industry 4.0 adoption depends on key enabling factors such as eco-efficient digital technologies, interoperability of systems, and strong organizational awareness toward sustainability. These enablers support the transition toward smarter, resource-efficient, and sustainable manufacturing practices [11]. In the transition from Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0, manufacturing system design (MSD) is increasingly structured using the Thinking-Modeling-Process-Enabler framework, which groups MSD methods around critical enabling factors that drive effective system development [12]. Integrating Industry 4.0 with lean manufacturing is crucial for achieving smart, efficient, and sustainable operations. Digital technologies enhance lean systems, but their effectiveness depends on balancing technological advancement with human-centered practices [13]. Industry 5.0 introduces human-centric, resilient, and sustainable manufacturing beyond the technology-driven focus of Industry 4.0. A literature and bibliometric review shows increasing post-pandemic research emphasizing Industry 5.0’s integration with sustainability and human-focused innovation [14]. The Italian ceramic tile sector is striving to boost efficiency, lessen environmental impact, and improve working conditions. Integrating Industry 4.0 tools has enabled smarter processes, reduced waste, and better production oversight, with multi-year collaborative efforts showing clear sustainability and digital workforce improvements [15]. The industrial landscape is now advancing toward Industry 6.0, which focuses on intelligent, autonomous, and sustainable systems that build upon the digital foundations established by earlier industrial revolutions. From the perspective of management fashion theory, this evolution represents not only technological advancement but also changing societal priorities that are redefining the direction of future industrial transformation [16].

A comprehensive review of prior Industry 4.0 adoption studies revealed that most existing research has examined enablers in isolation, focusing either on technological readiness or organizational preparedness, without integrating them into a unified model. Furthermore, previous studies have not included collaborative and visualization-related enablers—mechanisms that facilitate communication, cross-functional alignment, and data transparency—which are increasingly critical for successful implementation. Empirical studies using advanced modeling techniques remain limited, and almost no research simultaneously applies both PLS-SEM and CB-SEM to validate a multi-dimensional framework of enablers. Additionally, the mediation effect between technological and organizational enablers has not been explored, nor has the link between Industry 4.0 adoption and sustainability-oriented outcomes been sufficiently addressed, especially in the context of manufacturing in developing economies such as India. These gaps demonstrate the need for an integrated, empirically validated enabler framework that contributes to both Industry 4.0 theory and practice.

The Indian manufacturing sector provides a suitable context for this study because of its diverse industrial landscape, expanding technological capabilities, and supportive government programs such as Make in India and Digital India, which encourage digital transformation. Together, these factors make India a key emerging economy for examining the drivers and enablers of Industry 4.0 adoption.

To provide the main contributions of the reviewed papers for the ready reference of the future researchers

H1:

The technological enablers associated with implementing Industry 4.0 are positively correlated to the visualization and collaboration enablers.

H2:

The technological enablers associated with implementing Industry 4.0 are positively correlated to the organizational enablers.

H3:

The organizational enablers associated with implementing Industry 4.0 are positively correlated to the visualization and collaboration enablers.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows: Section 1 introduces the research background and research gap. Section 2 presents the enablers of Industry 4.0 implementation extracted from prior literature. Section 3 provides detailed descriptions of the identified enablers and development of the conceptual model. Section 4 explains the methodology, including the structural equation modeling (SEM) approach using PLS-SEM and CB-SEM. Section 5 presents the data analysis and empirical results. Section 6 discusses the findings, along with theoretical implications and practical contributions. Finally, Section 7 concludes the study and outlines future research directions.

Research Objectives

The primary objective of this research is to identify, categorize, and empirically validate the key enablers that support Industry 4.0 implementation in manufacturing organizations. Specifically, this study aims to:

- Identify and categorize Industry 4.0 enablers into technological, organizational, and collaborative/visualization factors through a comprehensive literature review.

- Develop and validate a conceptual model using PLS-SEM and CB-SEM to examine the relationships among these enablers.

- Investigate the mediating role of collaborative visualization mechanisms between technological and organizational enablers.

- Provide theoretical and practical contributions by linking Industry 4.0 adoption to sustainability-oriented performance improvements.

2. Enablers for Industry 4.0 Implementation

The in-depth study of the above 37 articles provided 35 elements that drive or enable organizations to adopt I4.0 effectively. These 35 elements are further grouped under 10 enablers. Including recent empirical case studies from global Industry 4.0 implementations, the review was strengthened through structured searches across major databases (Scopus, WoS, Science Direct), ensuring that the 35 elements and 10 enablers represent the latest technological and industrial advancements. The assignment of the 35 sub-enablers to the 10 major enablers followed a structured procedure. First, a systematic literature review was conducted, and each extracted sub-enabler was coded based on conceptual similarity. Second, thematic grouping was performed, where related sub-enablers were clustered into one overarching enabler. Finally, two rounds of expert validation (Delphi method) were carried out with two industry experts and three academic researchers specializing in Industry 4.0. Sub-enablers were linked to an enabler only when a minimum consensus level of 70% was achieved. These 10 enablers and sub-enablers are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Identified enablers and sub-enablers for Industry 4.0 implementation.

Industry 4.0 enablers have increasingly been examined through the broader lens of economic, environmental, and social sustainability. Considering these three dimensions offers a more comprehensive perspective on how Industry 4.0 adoption shapes overall industrial performance. On the economic front, digital technologies enhance cost effectiveness, boost productivity, and improve the utilization of assets. From an environmental standpoint, intelligent systems help optimize energy use, lower emissions, and reduce waste. Socially, Industry 4.0 supports safer working conditions, better ergonomics, and expanded opportunities for workforce up skilling. Incorporating these sustainability aspects provides a fuller understanding of how Industry 4.0 drives responsible, resilient, and future-oriented industrial transformation.

3. Description for Industry 4.0 Implementation

3.1. Data Analytics and AI

Data analytics is essential for driving automation within the industry. Big data has been available with industries for many decades, but it was the analytics which made it possible to get the useful insights from this data for gainful applications related to marketing, design, production, maintenance, etc. The main driver for Industry 4.0 in the semiconductor industry is big data analytics [17]. Data analytics is a primary enabler for the adoption of Industry 4.0, as indicated by [18]. According to Mogos et al. [19], the utilization of statistics and big data analytics is a key driver of Industry 4.0 implementation within the Norwegian industries of manufacturing. Furthermore, the vast availability of data supports the creation of sophisticated predictive maintenance solutions, as noted by [20]. Big data analytics and existing I4.0 tools like ICT systems and IoT in production drive Industry 4.0 adoption [21].

3.2. Computational Power and Connectivity

Real-time data is essential for digitalization or Industry 4.0 environment. For the continuously flow of data from various equipment and processes, the connectivity of communication channels becomes vital. Industry 4.0 adoption in Norwegian industries was driven by expertise in software programming, sensor technology, robotics, IT knowledge [19]. Industry 4.0 enhances communication between monitoring systems by integrating data from sensors, production, and customer feedback. This enables managers to make informed decisions, improving processes and meeting consumer needs [22]. Implementing IoT enhances process oversight and optimizes the supply chain, providing organizations with a competitive advantage in production efficiency [23]. IoT (Internet of Things) was identified as a driver for Industry 4.0 [24]. IIoT, with security and scalability as main challenges, was found as the enabler for the implementation of Industry 4.0 [25].

3.3. Innovation in Transferring Physical World to the Digital World

Virtual representation of the product helps in designing and developing digital models of the products. Smart and connected machinery and processes make it possible to connect and visualize the working and behavior of the machine/process/plant to get useful insights, particularly when reliability and safety are important concerns. Industry 4.0 provides advanced strategies to handle complexity and optimize operational efficiency [20]. Smart process plays a vital role in Industry 4.0 by facilitating limited batch production of tailored products with intricate designs. As a cornerstone of digital manufacturing, smart process enhances operational efficiency, accelerates market entry, and lowers costs. Smart factories use real-time monitoring to track operations, reroute products in emergencies, and optimize production for flexibility and sustainability [26]. A strong IT infrastructure with regular upkeep is crucial for Industry 4.0 to prevent system failures. Implementing smart maintenance systems helps avoid disruptions, though SMEs often face challenges due to limited financial resources for maintenance [22]. Smart products and operations, core to Industry 4.0, enhance performance and customer satisfaction by integrating product functions with customer data and production systems [3].

3.4. Innovation in Transferring Digital World to the Physical World

The development and availability of the 3D printing technologies and collaborative/autonomous robotics play a crucial role to quickly translate the digital data into actual physical world. High flexibility and scalability enable a swift response to market changes through shorter supply contracts while allowing greater product customization [27]. Additive manufacturing enhances traditional production methods and supports customized design solutions for Industry 4.0 [20]. Autonomous robots in Industry 4.0 collaborate with humans, performing tasks with precision and flexibility. They enhance productivity while reducing long shifts, monotony, and fatigue [26]. Autonomous and distributed entities will form Industry 4.0 manufacturing systems, requiring decentralized decision support for efficient management [28]. Robotics and machine interconnectivity in Industry 4.0 boost efficiency, cut costs, support training, and improve planning with tax benefits. 3D printing supports customization and shortens delivery times, positioning it as a significant enabler of Industry 4.0 [21].

3.5. Innovative Human–Machine Interactions

AR/VR/MR technologies help to impose digital world images in the physical world to enhance the visualization of the digital images which helps in preparing the implementation strategies effectively. Even simple touch HMI has improved the connectivity with machines. Improved human–machine interaction is facilitated by virtual and augmented reality, which overlays essential information into the worker’s field of vision [27]. Augmented reality enables real-time decisions in 3D environments, while virtual training aids uncertainty management and customer data collection, reducing travel and resource use [26]. Industry 4.0 manufacturing systems must continuously monitor and respond to unexpected events in real time. They utilize virtual plant and simulation models linked to sensors for process monitoring, allowing for instant control and predictive analysis [28]. Effective collaboration between humans and machines boosts production efficiency [23]. Augmented reality integrates digital elements into the physical environment, supporting applications in manufacturing, healthcare, and defense. As an Industry 4.0 enabler, it boosts shop-floor awareness and speeds up information flow, especially with 5G connectivity [29].

3.6. Supportive Technologies

Cyber-physical systems are integral part of Industry 4.0 technologies. Availability of technologies like blockchain, cloud, fog, or edge computing is providing confidence to the industry for a reliable, secure, scalable, and transparent data transfer as well as machine/facility sharing from remote through internet. Technology of all sorts (digitalization, connectivity, hardware, and software) are key enablers to Industry 4.0 adoption [30]. The availability of the system, as a technological enabler, ensures that authorized individuals can access data when required and employs various mechanisms to safeguard it from external threats [27]. The seamless connectivity within a manufacturing system is enabled by CPS, which functions in two modes: self-organized and decentralized [20]. ICT is vital for Industry 4.0, managing security risks and integrating advanced technologies to enhance competitiveness [26]. Key IT enablers for Industry 4.0 include interoperability for data exchange, flexibility to adapt to change, and standardized reference architectures to support system integration [31]. Cybersecurity protects data storage, cloud systems, and communications by preventing breaches and unauthorized access through planned security measures [32]. Industry 4.0 adoption is enabled by advanced digital technologies (IoT, cyber-physical systems, AI, data analytics), system interoperability, and organizational readiness, leading to efficient, resource-saving, and sustainable manufacturing [11].

3.7. Supportive Organization

An organization’s structure and culture help adopt new business models and innovative ideas easily. Organization as main enablers for Industry 4.0 adoption [30]. Strong leadership at the top level helps organizations adapt to changes and ensures the smooth implementation of enhanced processes [27]. The success of Industry 4.0 relies significantly on top-level management, as they provide essential guidance and oversee information systems operations [20]. Management support and commitment are vital enablers for Industry 4.0 [33]. Organizational strategy supports change by promoting managerial commitment and openness to innovation, while a strong digital strategy uses technology to enhance processes, rethink business models, and align with long-term goals [32]. Management support and commitment are vital enablers for Industry 4.0 [33]. Organizational strategy supports change by promoting managerial commitment and openness to innovation, while a strong digital strategy uses technology to enhance processes, rethink business models, and align with long-term goals [32].

3.8. Government Efforts and Promotions

Government initiatives facilitate the adoption of advance technologies and frameworks like Industry 4.0 by organizations. For Romanian SMEs, key factors driving implementation include shorter time-to-market and compliance with regulatory and legal requirements [1]. Normative pressures arise from the pursuit of legitimacy, driving organizations to assess industry peers and align with prevailing standards and norms within their sector [27]. Government initiatives are crucial for the growth of Industry 4.0. Policymakers should foster an ecosystem that transforms traditional manufacturing into a digital and intelligent sector. Digitization drives Industry 4.0, requiring strong leadership, collaboration, data security, digital skills, and supportive policies [26]. Government initiatives drive Industry 4.0 adoption by promoting innovation and allocating resources, encouraging businesses to embrace new technologies [34]. Policymakers are essential in enabling the transition from conventional production methods to more sustainable and innovative approaches. Support from external bodies—such as financial assistance for adopting new technologies—and government legislation ensuring data security can further facilitate this shift [31].

3.9. Collaborative Partnerships

Collaborative supply chains demand uniformity in standards, customer-centric, and availability of funds to adopt new technologies. Sharing financial responsibilities among organizations eases the burden on individual firms, facilitating the adoption of Industry 4.0. A collaborative network serves as a crucial enabler for implementing Industry 4.0 [35]. The enablers for the increased digitalization in manufacturing industries were investigated and flexibility, capability to implement the strategy. and sustainability were identified as the main enablers [36]. Rising demand drives Industry 4.0, as automation and digitalization boost supply chain efficiency. Smart systems adapt to needs, helping industries meet both personalized and projected demands [37]. Collaboration among supply chain partners serves as a critical enabler for Industry 4.0 [33].

3.10. Human Resources

Newer job descriptions are required for employee hiring, education and training. Humans are key enablers identified through a structured Mind Map [30]. The mindset and skills of employees are the key enablers of big data [18]. IoT and CPS are examples of Industry 4.0 technologies that enable automation and advanced task execution by skilled workers, significantly reducing human errors in work processes [27]. Smart manufacturing demands diverse skills, requiring industries to focus on targeted human resource development [38]. Empowering employees, promoting knowledge exchange, and ensuring clear communication indirectly support medium enterprises and are essential to the growth of micro, small, and combined MSMEs [39]. Human factors are key to Industry 4.0 success, as employees drive other elements through their skills, motivation, and development beyond basic training [32].

This research framework is grounded in the Diffusion of Innovation (DOI) Theory [40] and the Dynamic Capability Theory [41]. DOI Theory explains how organizations evaluate and adopt new technologies based on perceived advantages, compatibility, and complexity. This theory supports the identification of technological and organizational enablers that facilitate Industry 4.0 adoption. In addition, Dynamic Capability Theory emphasizes that organizations must continuously build technological, organizational, and collaborative capabilities in order to successfully respond to digital transformation. This perspective supports the inclusion of visualization and collaboration enablers in the model, as these capabilities enable firms to integrate digital resources, enhance cross-functional decision-making, and improve alignment during Industry 4.0 implementation. Together, these theories provide conceptual justification for examining how technological enablers influence organizational readiness and how collaborative visualization mechanisms mediate this relationship.

4. Methodology for Structural Equation Modeling

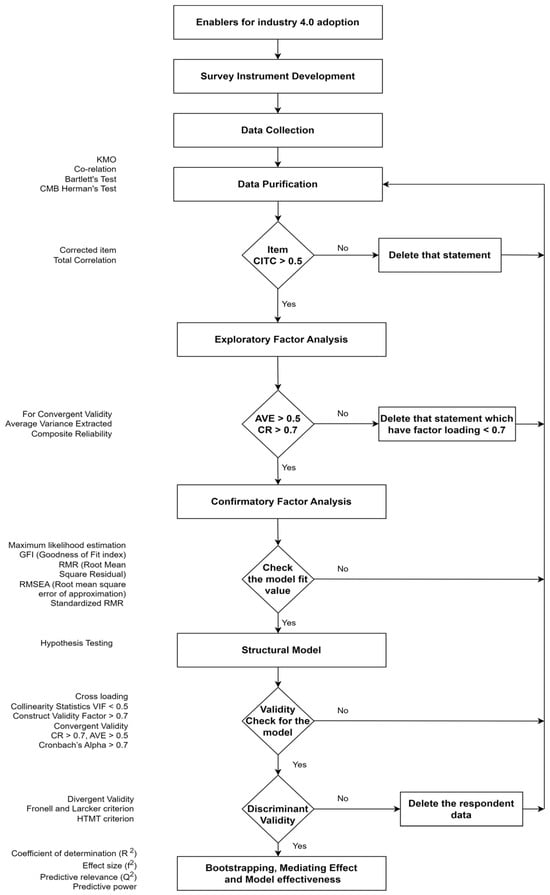

A collection of linear relationships is analyzed using structural equation modeling (SEM) within a structured framework, with the goal of assessing the degree to which the proposed model matches the real data. The structural equation modeling (SEM) process began by developing measurement items based on the 35 sub-enablers identified in the literature review, which were grouped into 10 enabler constructs. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was then performed to refine the measurement set, eliminating items with low communalities, cross-loadings, or insufficient factor contributions. The resulting refined factors were subsequently used to establish the final measurement model. The initial step in SEM typically involves developing a visual representation of the proposed model, known as a “path diagram,” which is grounded in existing theories or prior research. In these diagrams, measured variables are shown as rectangles, while latent or unobserved variables—those inferred from measured data—are illustrated using circles or ovals. Single-headed arrows indicate assumed directional influences between variables (i.e., one variable has a direct effect on another), while double-headed arrows depict mutual associations or correlations. Some researchers prefer using the term “arc” instead of “causal path” to describe these connections [42]. Figure 1 provides a comprehensive depiction of the research strategy that was used for this investigation. In this research, a dual approach using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) and Covariance-Based SEM (CB-SEM) was adopted to enhance methodological rigor. PLS-SEM was first employed, as it is particularly effective in analyzing formative constructs, managing complex interrelationships, and addressing datasets that may deviate from normality. Its predictive orientation also enabled the assessment of variance explained in the main constructs. Once predictive relevance was established, CB-SEM was applied to evaluate the overall model fit and confirm the theoretical framework. The integration of these two techniques combines the advantages of both approaches—PLS-SEM contributes predictive power and variance explanation, while CB-SEM provides model validation and theory testing. This complementary strategy ensures a more robust and coherent analysis.

Figure 1.

Research methodology for SEM.

The SEM analysis was conducted in two phases, following established SEM guidelines. In Phase 1 (PLS-SEM), the measurement model was evaluated by examining indicator reliability (factor loadings ≥ 0.70), internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability ≥ 0.70), and convergent validity (average variance extracted [AVE] ≥ 0.50). Discriminant validity was assessed using both the Fornell–Larcker criterion and the Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio (HTMT ≤ 0.85). In Phase 2 (CB-SEM), model fit indices were examined, including SRMR ≤ 0.08, CFI ≥ 0.90, TLI ≥ 0.90, and RMSEA ≤ 0.08. Indicators that did not meet these criteria were iteratively removed, guided by theoretical justification and modification indices. This two-step approach allowed predictive assessment (PLS-SEM) and confirmatory validation (CB-SEM), ensuring robustness and methodological rigor of the final model.

4.1. Measurement Items

A well-structured questionnaire was developed to assess the enablers for Industry 4.0 implementation. Participants were asked to rate each enabler using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 represented “no impact” and 5 indicated “very high impact,” with intermediate values indicating increasing levels of impact. This scale type is widely employed in research as it simulates an interval scale, enabling further statistical evaluation by ensuring consistent spacing between response options. It also encourages respondents to make clear and definite choices. The questionnaire underwent a two-phase pre-testing process. Initially, the draft was reviewed by two academicians who evaluated the items in terms of clarity and specificity. Their recommendations led to revisions aimed at improving the accuracy and phrasing of several questions. In the second stage, the refined questionnaire was given to research scholars, who completed it and highlighted any unclear or ambiguous items for further refinement. They were also invited to suggest improvements. This phase included participation from nine research scholars belonging to the Industrial and Production Engineering Department at Punjab Engineering College, Chandigarh. To ensure participants had a consistent understanding of the Industry 4.0 enablers, detailed descriptions were included with each item. Appendix A contains the finalized questionnaire, while Table 1 outlines the measurement indicators associated with each construct, along with the references from which they were adapted.

4.2. Population and Sampling

The research focused on the Indian manufacturing sector as the target population, with survey questions tailored specifically to evaluate the enablers of Industry 4.0 adoption. The primary objective was to examine these enablers affect the adoption of Industry 4.0 technologies. Data was gathered from various manufacturing sectors, including automotive parts, paper production, and steel industries. Simple random sampling technique was employed to provide equal selection opportunities for all units, thereby improving the representativeness of the results. Around 600 senior executives—comprising senior managers and higher-level professionals from manufacturing and production departments—were contacted via email. The message included a survey link, outlined the research’s purpose and background, and assured participants that their answers would be kept private and anonymous. The sample size for PLS-SEM was determined using the rule of thumb, selecting a number at least ten times the largest number of arrows directed toward any construct. For CB-SEM, the sample followed the guideline of 5 to 10 cases per estimated parameter to ensure sufficient statistical power and reliable outcomes. Simple random sampling was applied to meet the study objectives while minimizing selection bias. To enhance representativeness, participants were selected to reflect the demographic and contextual characteristics of the target population. Non-response was managed through follow-up email reminders, and the final dataset was evaluated for non-response bias, with statistical corrections applied as needed. These measures collectively reinforce the study’s methodological rigor and the validity of its results.

4.3. Data Collection

Data for the research was gathered between October 2022 and January 2023, during which 182 completed questionnaires were received out of the 600 distributed. This corresponds with the typical response rate in the Indian manufacturing sector, which generally falls between 30% and 35%. An initial sample size of 182 was considered adequate to investigate the targeted effects. Subsequently, the collected data were thoroughly cleaned and prepared to ensure accuracy and readiness for subsequent analysis. Five questionnaires were identified as exhibiting straight-lining behavior, where respondents were eliminated for repeatedly choosing the same response over a large number of questions. This reduced the dataset to 177 responses. Further examination revealed issues related to discriminant validity, leading to the removal of an additional 9 questionnaires with highly correlated responses. As a result, the final dataset comprised 168 valid responses used for the analysis. The data for this study were collected using a simple random sampling technique from 182 Indian manufacturing firms operating in diverse sectors such as automotive, electronics, textiles, and machinery. This approach ensured a broad industrial representation and minimized selection bias. Respondents were primarily mid- to senior-level managers involved in production, quality, or digital transformation functions, ensuring informed responses relevant to Industry 4.0 adoption.

The data for this study was collected between October 2022 and January 2023. After data collection, the research team proceeded through multiple structured phases, including: (i) iterative model development using PLS-SEM and CB-SEM, (ii) comprehensive assessment of construct validity and reliability (AVE, CR, HTMT, model fit indices), and (iii) manuscript drafting and revisions based on internal and external feedback. These activities required several cycles of analysis and refinement prior to submission. Although the data collection occurred earlier, the factors examined—such as digital infrastructure readiness, managerial commitment, financial investment, technological capability, and workforce development—are strategic, long-term enablers of Industry 4.0 that do not change abruptly. Thus, the dataset continues to accurately represent the current industrial context.

5. Data Analysis and Result

The analysis began with an examination of the respondents’ demographic characteristics and pertinent background details. Subsequently, the researchers performed evaluations of both the measurement and structural models utilizing SPSS software. The upcoming sections present a summary of the participant demographics along with an in-depth assessment of the measurement and structural models. In this study, each construct was defined and operationalized using established definitions from prior research, with items adapted from previously validated measurement scales. The survey instrument was pretested to ensure clarity, relevance, and contextual appropriateness, and necessary adjustments were incorporated based on the feedback. The reliability and validity of the measures were assessed through indicators such as Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability, and factor loadings. To promote transparency and replicability, the manuscript provides detailed information on all constructs, their operational definitions, and the original sources of the measurement items.

5.1. Demographic Data

The demographic analysis of the collected data revealed several key insights regarding the participants and their respective organizations. A majority of respondents (64.29%, n = 117) belonged to large-scale enterprises, while 13.19% (n = 24) represented medium-scale, 10.99% (n = 20) came from small-scale, and 11.54% (n = 21) were from micro or tiny organizations. Industry-wise, the highest number of respondents (n = 111) were from the automotive parts manufacturing sector, followed by those involved in food and beverage production (n = 17), steel manufacturing (n = 11), agricultural equipment (n = 9), pharmaceuticals and medicinal products (n = 8), paper manufacturing (n = 7), electronics and optical equipment (n = 6), scientific instruments (n = 6), chemical manufacturing (n = 5), and domestic appliances (n = 2). In terms of designation, production engineers formed the largest group at 30.40% (n = 55), followed by plant and associate managers (17.60%, n = 32), design engineers (17.03%, n = 31), project engineers (13.73%, n = 25), R&D engineers and assistant engineers (each 3.2%, n = 6), managing directors (2.4%, n = 4), and quality assurance engineers (1.6%, n = 3). Regarding company turnover, the highest share of participants (43.96%, n = 80) came from organizations with annual sales exceeding INR 500 crore. This was followed by 32.42% (n = 59) from firms with turnover between INR 100–500 crore, 13.29% (n = 24) from the INR 1–100 crore range, and 10.44% (n = 19) from companies earning less than INR 1 crore annually. Export activity showed that 54.4% (n = 99) of the respondents were from firms involved in partial exports, while 16.8% (n = 31) represented 100% export-based firms, and 28.8% (n = 52) were from non-exporting companies. Work experience varied, with 40.8% of employees having 6–10 years of experience, followed by 32% with 2–5 years, 8.8% with over 20 years, 6.4% with 10–15 years, another 6.4% with less than 2 years, and 5.6% with 11–15 years. Lastly, 54.40% of respondents were employed in companies with a workforce of over 500 employees, 23.08% were from organizations with 200–500 employees, 12.64% from firms with 50–200 employees, and 9.89% from companies with fewer than 50 employees. A detailed demographic profile of the participating firms—including industry type, employee size, and key organizational characteristics—is provided in Table 2. While specific financial data (e.g., revenue or I4.0 investment amounts) were not collected due to confidentiality constraints, the available demographic indicators adequately represent the diversity and scale of the sample.

Table 2.

Demographic analysis of data.

5.2. Assessment of Measurement and Structural Models

5.2.1. Data Purification

Internal consistency was assessed using reliability measures, specifically Cronbach’s alpha. This analysis, carried out with SPSS version 26.0, evaluated the consistency of items associated with each identified enabler. While a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.70 is typically considered the minimum acceptable threshold for reliability, values as low as 0.60 are acceptable for newly developed measurement scales like the one used in this study. Items that lowered the overall alpha were examined and removed if necessary to improve the scale’s internal consistency.

Three primary methods are commonly utilized to evaluate construct validity: the multi-trait multi-method technique, factor analysis, and correlation or partial correlation approaches. Of these, factor analysis is the most frequently applied method for deciding which items to retain in a reliable measurement instrument. Given that a central objective of this study is to develop variables that precisely represent each enabler, factor analysis plays a crucial role in this process. Factor analysis was selected as the most suitable method for validating construct validity, in accordance with established research practices [38,39,40]. To assess the suitability of the data for factor analysis, it is essential to verify that the minimum recommended ratio of observations to variables has been met [43]. A minimum sample size of 30 is generally considered sufficient for performing factor analysis. To evaluate the appropriateness of the factor model, it is crucial to examine the strength of the relationships among variables [44]. Before conducting factor analysis, the inter-item correlations should be assessed using essential measures such as the correlation matrix, Bartlett’s test of sphericity, and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test for sampling adequacy, as supported by prior research [45].

Correlation matrix: An examination of the correlation coefficients among items within each construct reveals that all values surpass the 0.3 benchmark, suggesting that the items are likely affected by common underlying factors [45].

Bartlett’s test of sphericity: Bartlett’s test evaluates whether the correlation matrix is significantly different from an identity matrix, which would indicate meaningful relationships among the variables. In this study, the test yielded a Chi-square value of approximately 783.805 with 45 degrees of freedom and a significance level of 0.000, confirming the existence of significant correlations. These findings demonstrate that the correlations among the ten enablers are statistically significant, implying that the variables are likely affected by common underlying factors.

KMO measure of sampling adequacy: The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure produced a value of 0.876, surpassing the widely accepted threshold of 0.5. This indicates that the dataset is appropriate for factor analysis, and consequently, all ten identified enablers were considered suitable for inclusion in the study.

The initial phase of data analysis involved evaluating common method bias (CMB), also known as common method variance (CMV). A commonly used technique for this assessment is Harman’s single-factor test, typically conducted through principal component analysis or exploratory factor analysis. Within the framework of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), this test is adapted accordingly. It is carried out by specifying a model with a single latent construct and then performing either a factor-based or composite-based analysis. The focus is on the variance explained by the first factor (associated with the largest eigen value), which is then compared to the standard threshold of 50%. If the proportion of variance explained by the single factor remains below the established threshold, it indicates that common method bias is not likely to pose a substantial issue [46]. Common method variance and structural parameters are analyzed both including and excluding these measures to assess their possible impact on the observed relationships [47]. The variance for the data is 48.865%, which is less than 50%, as presented in Table 3. The survey was carefully designed to minimize bias by ensuring respondent anonymity, separating questions related to independent and dependent variables, and using clear and straightforward wording to avoid ambiguity. To statistically assess common method bias, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted, revealing that no single factor explained the majority of the variance. Additionally, supplementary techniques such as the marker variable approach and full collinearity assessment were applied, further confirming that common method bias did not pose a significant concern in this study.

Table 3.

Total variance explained.

Item–total correlation measures how an individual item relates to the combined score of all items within the same set. Corrected item–total correlation (CITC) excludes the item’s own score from the total composite score calculation, which is why it is termed “corrected.” Items with item–total correlations below 0.50 are typically considered for removal from the scale [48]. As indicated in Table 4, the corrected item–total correlation (CITC) values for all enablers exceeded the threshold of 0.5.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of data.

The overall findings from the correlation matrix, Bartlett’s test of sphericity, and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure collectively indicate that the dataset is dependable and suitable for comprehensive analysis and model development.

5.2.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to identify the underlying latent constructs that represent the complete collection of observed items. The purpose of the EFA was to reveal the core dimensions representing major categories and to examine how the identified enablers align with these factors through their respective loadings, as outlined in Table 5. This procedure led to the development of a model pinpointing the key enablers related to Industry 4.0 adoption. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) utilizing principal component analysis with Varimax rotation was applied. The analysis revealed three separate factors, each having an eigen value greater than one. The factor loadings, which reflect the strength of the relationship between variables and their respective factors, were deemed acceptable. The minimum loading identified was 0.657 for the variable ‘Computational power and connectivity,’ which exceeds the commonly recommended threshold of ±0.45 [45].

Table 5.

Factor loadings of enablers for Industry 4.0.

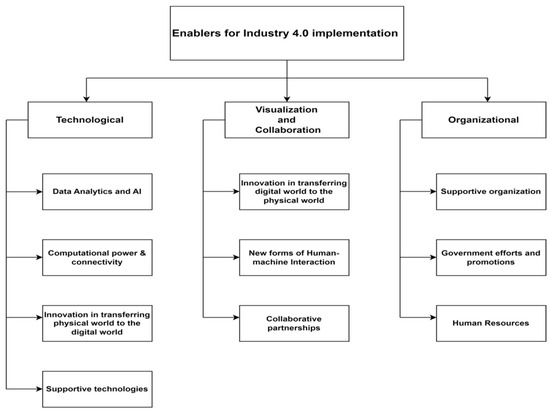

To strengthen the credibility of the results, separate factor analyses were performed for each of the three recognized components. The results validated that the associated enablers are effectively captured by their respective factors, as outlined in Table 5. Therefore, it is clear that each enabler plays a significant role in its respective factor. To establish construct validity, it is essential to first assess the measurement model before proceeding to the structural model analysis. This assessment includes evaluating construct validity, as well as convergent and discriminant validity. Convergent validity is deemed satisfactory when the average variance extracted (AVE) is greater than 0.5, which requires all items to have standardized loadings above 0.7. After thoroughly analyzing the enablers linked to each category, the three identified factors were named technological enablers, organizational enablers, and visualization and collaboration enablers, as illustrated in Figure 2. All statistical information has been thoroughly verified and consistently presented, covering factor loadings, reliability indicators such as Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability, average variance extracted (AVE), path coefficients, and corresponding significance levels.

Figure 2.

Classification of enablers for Industry 4.0 adoption.

Technological enablers: To measure technological enablers, four main enablers and sixteen sub-enablers were assessed, as listed in Table 1. Data analytics plays a vital role in industry automation. Big data has been available with industries for many decades, but it was the analytics which made it possible to get the useful insights from this data for gainful applications related to marketing, design, production, maintenance, etc. Real-time data is essential for digitalization or Industry 4.0 environment. For the continuous flow of data from various equipment and processes, the connectivity of communication channels becomes vital. Smart and connected machinery and processes make it possible to connect and visualize the working and behavior of the machine/process/plant to get useful insights, particularly when reliability and safety are important concerns.

Organizational enablers: To measure organizational enablers, three enablers and eleven sub-enablers were assessed, as listed in Table 1. A clear strategic vision and roadmap is required. I4.0 cannot be achieved by simply tactical low-cost technology purchases. Flat organizational structures, data effective culture, agile mindset, alternate development paths, and distinct jobs around I4.0 with clear roles and responsibilities enables I4.0 adoption. Positive government rules and regulations, long term policies, and financial incentives, particularly in developing and emerging nations, provide traction for I4.0 adoption. Continuous developments of people in an organization bring innovativeness and provide the better-quality products.

Visualization and Collaboration enablers: To measure visualization and collaboration enablers, three enablers and eight sub-enablers were assessed, as listed in Table 1. AR/VR/MR technologies help to impose digital world images in the physical world to enhance the visualization of the digital images which helps in preparing the implementation strategies effectively. The development and availability of the 3D printing technologies and collaborative/autonomous robotics play a crucial role to quickly translate the digital data into actual physical world. I4.0 requires an ecosystem where B2B, B2C, and strategic partnerships can be developed based on win–win concept. Collaborative supply chains demand uniformity in standards, customer-centric, and availability of funds to adopt new technologies.

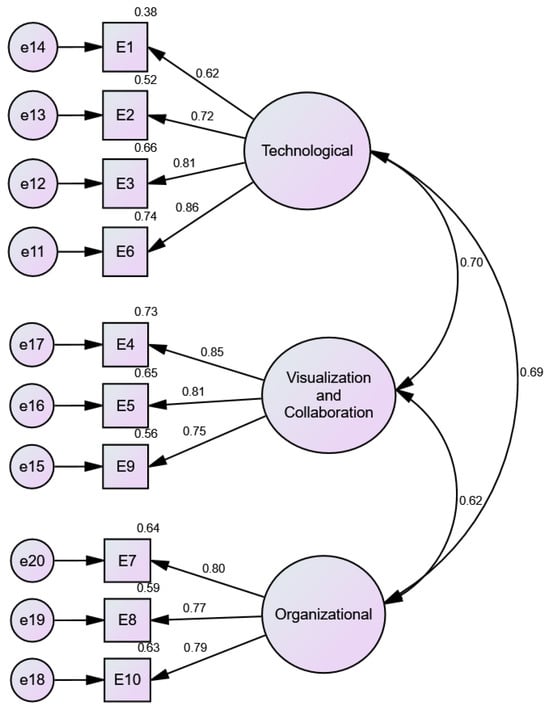

5.2.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA), while useful, does not fully capture all essential measurement characteristics of constructs—particularly aspects like unidimensionality [48]. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) is a multivariate technique employed to further validate a model that was initially specified through exploratory factor analysis (EFA) [45]. The EFA-based model was imported into AMOS 26.0, SEM software version 26, to perform confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), the results of which are presented in Figure 3. The path diagram displays a measurement model comprising three latent variables, each associated with ten measurable indicators. In this visual representation, observed indicators are depicted as rectangles, while the corresponding latent constructs are illustrated using oval shapes. Measurement errors linked to the observed variables are indicated by circular nodes connected via single-headed arrows (e11, e12, e13, …, e20). Double-headed arrows illustrate the true correlations among the latent constructs.

Figure 3.

Measurement model for Industry 4.0 adoption enablers.

Table 6 displays the regression weights in both standardized and unstandardized forms. In the case of unstandardized estimates, one item within each construct is designated as fixed, and the remaining item weights are calculated relative to it. Specifically, the regression weights for “supportive technologies”, “collaborative partnerships”, and “human resources” are fixed arbitrarily. The unstandardized regression weights demonstrate that a one-unit rise in a latent variable results in an increase in the observed item equal to its specific regression weight. In contrast, the standardized regression weights reflect how a one standard deviation increase in the latent construct corresponds to a change in the observed variable’s standard deviation by the respective standardized coefficient.

Table 6.

Confirmatory factor analysis statistics.

In the confirmatory factor analysis, the lowest observed critical ratio—calculated as the item estimate divided by its standard error—was 8.444, which exceeds the commonly accepted threshold of |1.96|, signifying significance at the 0.01 level. The outcomes of the measurement model assessment conducted using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Standard and calculated value for model fit.

The entire model fit indicators fall within acceptable limits, affirming the suitability of the measurement model shown in (Figure 3). Consequently, the structural model can now be examined to validate the overall framework. The covariance values between latent constructs range from 0 to 1, where 0 denotes no shared variance (independent constructs), and 1 signifies that the constructs are essentially identical in what they measure. Table 8 provides the correlation and covariance values among the three latent variables identified. The results indicate that while these variables represent different categories of enablers, they are not entirely independent from one another.

Table 8.

Correlation and covariance of latent variables.

5.2.4. Structural Model

Structural equation modeling (SEM) is a statistical technique that examines and estimates causal relationships by combining empirical data with theoretical frameworks or assumptions [45]. Confirmatory modeling typically begins with hypotheses that are expressed through causal models. Based on an in-depth assessment of the measurement model, the subsequent hypotheses were developed to facilitate the evaluation of the full structural model.

H1:

The technological enablers associated with implementing Industry 4.0 are positively correlated to the visualization and collaboration enablers.

H2:

The technological enablers associated with implementing Industry 4.0 are positively correlated to the organizational enablers.

H3:

The organizational enablers associated with implementing Industry 4.0 are positively correlated to the visualization and collaboration enablers.

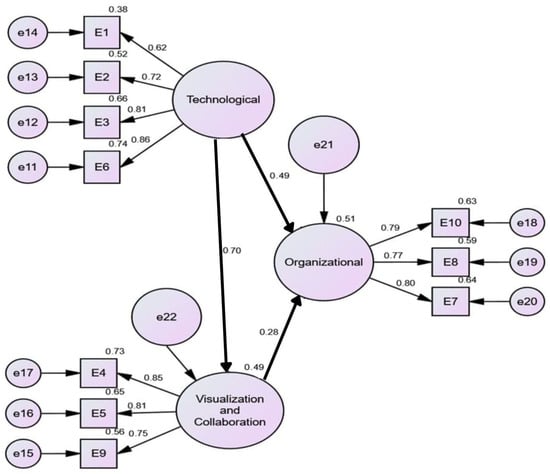

The entire structural equation model was assessed through the application of maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) technique, a method recognized for yielding reliable outcomes even with relatively small sample sizes, such as 50 [45]. The proposed structural framework is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Proposed full structural model of enablers for Industry 4.0 adoption.

Hypotheses H1, H2, and H3 were validated, supported by the β coefficients and p-values. At a 95% confidence level, the acceptance criterion requires p-values to be below 0.05, as reflected in the results presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

Hypothesis test result for Industry 4.0 enablers.

Accepted hypotheses show that technological enablers affect the organizational enablers and organizational enablers affect visualization and collaboration enablers. This indicates that enhancing technological enablers should be the primary focus for the successful implementation of Industry 4.0, as they form the foundational support for its adoption. The squared multiple correlation was 0.514 for organizational enablers; this shows that 51.4% variance in organizational enablers is accounted by technological enablers. The squared multiple correlation was 0.486 for visualization and collaboration enablers; this shows that 48.6% variance in visualization and collaboration enablers is accounted by technological enablers.

Mediating Effect

The standardized indirect effect of technological enablers on organizational enablers is statistically significant at the 0.05 level (p = 0.027, two-tailed), indicating a meaningful mediated relationship between the two constructs. This result is based on a bootstrap estimation using two-sided bias-corrected confidence intervals.

5.3. Collinearity Statistics (VIF)

Before assessing the structural model in Smart PLS 4, it is essential to examine lateral collinearity. As shown in Table 10, the inner Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values for all independent and mediating variables were below the recommended limit of 5.0, suggesting that multicollinearity did not pose a problem in the model [52]. Therefore, the results indicate that lateral collinearity was not an issue in this study.

Table 10.

Multicollinearity test for exogenous constructs.

5.4. Measurement Model (Outer Model)

Before proceeding with the structural model analysis in Smart PLS 4, it is important to first evaluate the measurement model. The following section will concentrate on assessing the model’s reliability and validity by analyzing construct validity, convergent validity, and discriminant validity.

5.4.1. Construct Validity

The research incorporated ten enablers, all of which were retained based on their strong factor loadings, each exceeding the 0.5 threshold. The factor loadings for these enablers ranged from 0.719 to 0.893. These items formed the basis for analyzing construct reliability and for conducting tests to establish convergent and discriminant validity. The selected indicators formed the basis for evaluating the construct’s reliability and validity, encompassing assessments of internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. A detailed summary of these results is presented in Table 11.

Table 11.

Reliability and validity analysis.

Convergent Validity

To evaluate convergent validity, Cronbach’s alpha, average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability (CR) were assessed for each construct, as shown in Table 11 and Figure 5. The factor loadings for all items ranged between 0.719 and 0.893, surpassing the minimum recommended threshold of 0.70 [52]. The composite reliability (CR) values were between 0.892 and 0.905, exceeding the acceptable cutoff of 0.70, while the average variance extracted (AVE) values ranged from 0.675 to 0.760, confirming adequacy as they were above the 0.50 standard. Moreover, Cronbach’s alpha values for all constructs were higher than 0.70, demonstrating strong internal consistency.

Figure 5.

Measurement model of enablers for Industry 4.0.

Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity was established through three principal approaches: examining cross-loadings, applying the Fornell–Larcker criterion, and assessing the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio. Initially, cross-loadings were scrutinized to ensure that each item had a higher loading on its designated construct compared to other constructs [52]. This means that each indicator’s loading on its own latent variable must surpass its loadings on all other factors. As demonstrated in Table 12, all indicators satisfy this criterion. Subsequently, the Fornell–Larcker [53] criterion was used, which stipulates that the average variance extracted (AVE) for every construct must be greater than the squared correlation coefficients between that construct and any other constructs. Table 13 confirms that this requirement is met for all constructs, validating adequate discriminant validity.

Table 12.

Cross-loading.

Table 13.

Discriminant validity (Fornell–Larcker).

Furthermore, discriminant validity was also assessed using the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio as shown in Table 14, all HTMT values fell within the permissible limits, staying below the recommended thresholds of 0.85 or 0.90 [49,50].

Table 14.

Discriminant validity (HTMT).

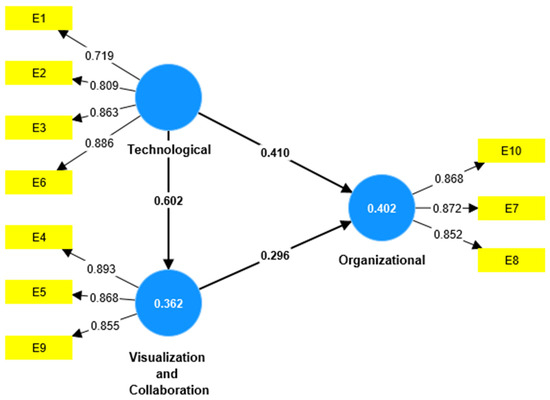

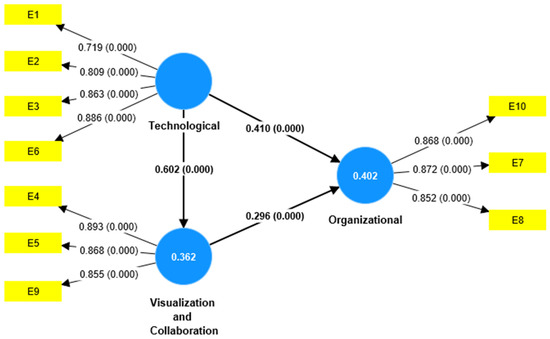

5.5. Structural Model (Inner Model)

The structural model was evaluated following the five-step procedure described by [52], which includes assessing collinearity, examining path coefficients, analyzing R2 values, calculating effect sizes (f2), and evaluating predictive relevance (Q2). The assessment began with a collinearity check (see Table 10) [54]. Subsequently, path coefficients (β) and R2 values were reviewed to determine the strength of the hypothesized causal relationships, in accordance with the guidelines of [55]. Lastly, a bootstrapping technique was employed to derive p-values for each path; with the findings detailed in Table 15. The analysis revealed technological enablers has significant relationships with visualization and collaboration enablers and organizational enablers. Visualization and collaboration enabler has significant effect on organizational enablers. According to the results in Table 15, H1, technological enablers have significant influence on visualization and collaboration enablers (Path coefficients = 0.602, p < 0.05). Similarly, hypothesis H2 predicted that technological enablers have significant influence on organizational enablers (Path coefficients = 0.410, p < 0.05) and hypothesis H3 predicted that visualization and collaboration enablers have significant effect on organizational enablers (Path coefficients = 0.296, p > 0.05). Figure 6 presents the final structural model derived using PLS-SEM, depicting the interrelationships among the key challenge constructs and their combined impact on Industry 4.0 adoption in manufacturing. The figure displays the latent constructs, the hypothesized causal paths linking them, and the significance levels associated with each relationship.

Table 15.

Bootstrapping.

Figure 6.

Full structural model of enablers for Industry 4.0 adoption.

5.5.1. The Coefficient of Determination (R2)

Table 16 displays the R2 values for the two endogenous constructs—organizational enablers and visualization and collaboration enablers. Following Cohen [56], R2 values of 0.75, 0.50, and 0.25 are generally considered to represent high, moderate, and low explanatory power, respectively. In this study, the R2 of 0.402 for the “Organizational” construct indicates that the “Technological” exogenous factor accounts for 40.2% of its variance, reflecting a moderate level of explanatory strength [56]. Additionally, the adjusted R2 for organizational enablers was 0.394; this suggests that the overall regression model effectively validates the proposed hypotheses.

Table 16.

Variance explained in endogenous latent variables.

5.5.2. The Effect Size (f2)

Effect size (f2) evaluates the unique contribution of exogenous variables to endogenous variables by focusing on their distinct variance rather than shared variance [45]. Cohen [56], provided a widely adopted framework for interpreting effect sizes, defining d = 0.2 as small, d = 0.5 as medium, and d = 0.8 as large. The calculated effect sizes for this study are presented in Table 17. Two exogenous effect sizes impacting the endogenous construct “Organizational” were assessed; one of them technological were found to be small; visualization and collaboration were found to be trivial. Additionally, the effect size of technological on visualization and collaboration was medium. Nevertheless, applying standard benchmarks for effect size can be challenging, as the magnitude of effects often varies with the specific framework and research context [45].

Table 17.

Effect Size.

5.5.3. The Predictive Relevance (Q2)

Predictive relevance (Q2) is used to evaluate the extent to which exogenous variables can effectively predict the associated endogenous variables [52,53]. A Q2 value exceeding zero signifies that the exogenous variables have predictive relevance for their corresponding endogenous variables [57]. As presented in Table 18, both organizational enablers and visualization and collaboration enablers recorded Q2 values greater than zero (Q2 > 0), indicating that the model demonstrates sufficient predictive relevance and validity [58]. Furthermore, according to Shmueli et al. [59], within PLS-SEM analysis, a model exhibits strong predictive power when all indicators show lower Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) or Mean Absolute Error (MAE) values compared to those from a Linear Model (LM). Table 19 confirms that this condition was met, validating the model’s high predictive accuracy.

Table 18.

Predictive relevance (Q2).

Table 19.

Predictive power.

5.5.4. Mediating Effect

The mediation effect was evaluated using the bootstrapping technique, as recommended by [55]. This study explored a single mediating effect. As shown in Table 20, the findings indicate that the variable “visualization and collaboration” significantly mediates the relationship between technological and organizational enablers. To strengthen clarity and reliability, the mediation analysis was carried out using bias-corrected confidence intervals to assess indirect effects. The results clearly present direct, indirect, and total effects, along with their corresponding significance levels. Furthermore, robustness checks were conducted across alternative model specifications, ensuring the stability and consistency of the mediation outcomes. These procedures collectively enhance both the transparency and credibility of the findings.

Table 20.

Mediating effect of Industry 4.0 enablers.

6. Discussion, Theoretical Implications, and Practical Implications

6.1. Discussion

This research enhances the theoretical understanding of Industry 4.0 adoption by moving beyond descriptive insights to propose a more comprehensive framework. Unlike earlier models that mainly focused on technological readiness and financial investment, the findings emphasize the pivotal role of organizational culture, digital capabilities, and workforce reskilling as mediating elements influencing adoption outcomes. By incorporating these aspects, the study refines existing models and presents a framework that more accurately reflects the complexities of adoption in emerging economies. The contribution provides a structured classification of enablers and challenges, extending current theories of Industry 4.0 adoption and offering a solid foundation for future empirical studies and managerial practice. This complements previous studies such as Gadekar et al. [3] and Krishnan et al. [60], which addressed I4.0 readiness without incorporating visualization and collaboration as mediating constructs.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

This study provides several theoretical contributions to the literature on Industry 4.0 (I4.0) adoption. First, by identifying ten key enablers and grouping them into three overarching factors, the research enhances existing adoption frameworks that have often been fragmented or focused narrowly on technological readiness. This hierarchical organization offers a more integrative taxonomy of adoption enablers, encompassing technological, organizational, and human-centered dimensions, thereby extending prior models that addressed only select aspects.

Second, the study demonstrates that visualization and collaboration serve as a mediator between technological enablers and organizational readiness, adding a novel perspective to socio-technical adoption theory. While previous research highlighted the need for organizational alignment, the findings empirically show that visualization tools and collaborative practices are critical mechanisms through which technological investments lead to enhanced organizational preparedness. This mediation clarifies the causal pathway, illustrating that technological capabilities must be embedded within social and organizational contexts to effectively support adoption.

Collectively, these contributions deepen the theoretical understanding of I4.0 adoption by presenting both a structured taxonomy of enablers and an empirically validated mechanism linking technology to organizational readiness via collaborative dynamics.

6.3. Practical Implications

The study’s findings offer valuable guidance for both practitioners and policymakers engaged in Industry 4.0 transformation initiatives. The ten identified enablers—organized into three higher-order factors (technological, visualization and collaboration, and organizational)—provide managers with a structured and measurable framework to prioritize the sequence of interventions rather than treating enablers in isolation. This taxonomy allows firms to assess their internal readiness, identify weak enabler dimensions, and allocate resources toward targeted capability development.

The mediating role of visualization and collaboration demonstrates that technological investments alone are insufficient. Effective Industry 4.0 adoption requires integration of digital visualization tools (e.g., digital twins, real-time dashboards, simulation environments) along with enhanced cross-functional collaboration. Thus, beyond technology acquisition, managers should focus on workforce training, cross-team communication, and digital governance structures to ensure alignment between technology, processes, and people.

From a policy perspective, this research highlights the need for enabling mechanisms such as workforce upskilling programs, incentives for technology acquisition, and shared digital innovation platforms to support collaborative experimentation. Moreover, the findings show that Industry 4.0 adoption directly contributes to sustainable and resource-efficient production by enhancing transparency, reducing waste, improving traceability, and supporting circular economy practices. Aligning Industry 4.0 initiatives with sustainable development strategies can accelerate progress toward SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production). Overall, this study translates theoretical insights into actionable strategies, enabling firms to adopt Industry 4.0 in a more structured, collaborative, and sustainability-oriented manner.

Recent industrial developments indicate a progression from the automation-focused paradigm of Industry 4.0 to the emerging Industry 5.0 framework, where technological innovation is complemented by human-centricity, resilience, and sustainability. The findings of this study reflect this shift, as they highlight the importance of organizational preparedness, sustainable operations, and effective integration of technology with human capabilities. These insights suggest a movement from a technology-centric approach (Industry 4.0) toward a balanced framework in which digital transformation enhances human value and supports long-term sustainable growth (Industry 5.0). In addition, a comparison with studies from other sectors-such as automotive, electronics, and process-based industries reveals similar patterns. Across these diverse environments, interoperability, data-driven decision making, and sustainability-focused technologies consistently emerge as key success factors. This alignment demonstrates that the enablers identified in this research are not limited to the specific context studied but are broadly relevant across industries undergoing digital transformation.

7. Conclusions

This study systematically reviewed the literature to identify ten key enablers 35 associated sub-enablers that are crucial for effectively implementing Industry 4.0 into practice in the industries of manufacturing. Although Industry 4.0 has matured and several core technologies—such as IoT, big data analytics, cyber-physical systems, robotics, and AI—are already deployed across many sectors, research into these enabling factors is still developing. Emerging study point to new enablers, including blockchain integration, enhanced human–machine collaboration, machine-learning-based automation, and machine-to-machine connectivity, which are shaping the next stage of digital manufacturing. Even with these technological advancements, there is still a noticeable shortage of comprehensive exploratory, comparative, and descriptive studies that examine how these enablers operate across diverse industrial environments, particularly in developing economies. This study addresses part of that gap by presenting a unified and empirically tested framework that offers deeper insights into the critical elements influencing Industry 4.0 adoption. The model was confirmed through empirical data gathered from 182 manufacturing companies in India. This paper advances the field by providing insightful answers to four important research issues. First, the main contributions of the reviewed publications are presented for future researchers to reference.

Second, data analytics and AI, computing power and connection, innovation in moving the physical world to the digital world, and supported technologies all have a significant impact on supporting organizations, government initiatives and promotions, and human resources for Industry 4.0 adoption. They will also have an impact on collaborative partnerships, innovative human–machine interactions, and innovation in the transfer of digital world to the physical world. In conclusion, this study investigated a single mediating effect. The results indicate that visualization and collaboration serve as significant mediators in the link between technological enablers and organizational enablers. The study offers practical guidance for industry professionals, emphasizing the importance of prioritizing data analytics, artificial intelligence, computing capabilities, and robust connectivity to successfully navigate digital transformation and implement Industry 4.0 initiatives. Policymakers can also strengthen supportive technology and government activities and promotions to help manufacturing industries accelerate Industry 4.0 adoption. This study highlights the key enablers of Industry 4.0 adoption and places them within the framework of sustainable production and consumption. By combining technological, organizational, and collaborative capabilities, firms can enhance their digital readiness, optimize resource use, reduce waste, and implement circular production practices. The findings indicate that digital adoption not only drives operational efficiency but also promotes environmental and social sustainability. These insights can guide policymakers and industry leaders in developing integrated strategies that connect digital transformation with circular economy initiatives and broader sustainability targets. Overall, the research advances both theoretical understanding and practical application by linking Industry 4.0 adoption to more sustainable, responsible, and policy-aligned industrial practices. The results align with studies from Malaysia, Germany, and Thailand, confirming the universal importance of technological readiness, organizational support, and workforce competence in driving Industry 4.0 adoption.

This study is limited by its cross-sectional design, which allows for identifying associations but not establishing causality. Additionally, with 61% of respondents from the automotive sector, the findings may reflect industry-specific dynamics and may not generalize across all manufacturing sectors.

Future Research Directions

Future work could test the proposed framework using longitudinal data, cross-sectoral comparisons, and multi-group SEM to validate sector-specific differences and dynamic evolution of enablers over time. Additionally, applying this model in cross-country contexts would improve generalizability, as Industry 4.0 adoption varies significantly across nations due to differences in digital readiness, policy support, and technological maturity. Such comparative studies would offer deeper insights into how national digital ecosystems shape Industry 4.0 adoption pathways.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.T. and P.S.; Methodology, R.T.; Software, R.T.; Validation, R.T.; Formal analysis, R.T.; Investigation, R.T.; Data curation, R.T.; Writing—original draft, R.T.; Writing—review and editing, R.T., K.S.S. and S.T.; Visualization, K.S.S. and S.T.; Supervision, K.S.S., P.S. and S.T.; Project administration, K.S.S. and P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is waived for ethical review as such survey-based studies that collect non-sensitive, non-identifiable responses are exempt from requiring formal Institutional Ethics Committee approval by the policies of Punjab Engineering College (Deemed to be University), Chandigarh, and the general guidelines for social science and management research in India.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

Acronyms and abbreviations used in the manuscript.

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| PLS-SEM | Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling |

| CB-SEM | Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modeling |

| I4.0 | Industry 4.0 |

| IIoT | Industrial Internet of Things |

| MR | Mixed reality |

| VR | Virtual reality |

| AR | Augmented reality |

| CPS | Cyber-physical systems |

| B2B | Business-to-Business |

| B2C | Business-to-Consumer |

| HMI | Human–Machine Interface |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technology |

| IT | Information Technology |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| MSME | Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises |

| SME | Small and Medium Enterprises |

| CFA | Confirmatory factor analysis |

| EFA | Exploratory factor analysis |

| MSD | Manufacturing system design |

| AMOS | Analysis of Moment Structures |

| AVE | Average variance extracted |

| CR | Composite Reliability |

Appendix A

From: Rupen Trehan <rupentrehan.phd19mech@pec.edu.in>

Subject: Survey regarding Enablers and Challenges for Industry 4.0

Dear Sir/Madam,

I am Rupen Trehan, a Research Scholar currently pursuing my doctoral studies at Punjab Engineering College (Deemed to be University), Chandigarh. My research focuses on the Development of Industry 4.0 Enablers and Challenges for Indian Industry. It is a privilege to connect with you on this significant topic. Industry 4.0—also referred to as smart or digital manufacturing—represents the fourth industrial revolution. It integrates robotics and advanced computing to automate operations, enhance machine efficiency, and reduce reliance on manual intervention. This revolution is driven by digital technologies that bridge the physical and digital domains; fostering seamless collaboration among stakeholders, including partners, suppliers, and workforce, while streamlining industrial processes. One of the critical gaps in this area, especially for developing nations like India, is the absence of a comprehensive framework that identifies key enablers and challenges related to Industry 4.0 adoption. In line with this, I humbly request you to kindly take a few moments to complete the attached questionnaire, which forms an essential part of my research. Your thoughtful and valuable input will significantly contribute to the success of this study, and I would be pleased to acknowledge your support in my work. Thank you for your time and cooperation.

Thanking you.

Yours truly,

Rupen Trehan

9812109916, 8708624207

- PART—1: General information of participating organization and responding person.

| Name of the Organization: | __________________________________________________ | |

| Address of the Organization: | __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ | |