Abstract

Against the backdrop of global climate change and carbon neutrality goals, the transportation sector has become a focal point in urban carbon emission research. This study develops a Spatiotemporal Geographically Weighted Regression (SGTWR) model that integrates spatial, temporal, and attribute similarity dimensions to identify the main driving factors of urban transportation carbon emissions (TCE) across 287 Chinese cities from 2000 to 2019. The model incorporates climatic and geographical variables to capture the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of emission patterns. The results indicate that population density, private vehicle ownership, and heating degree days have positive effects on TCE, while terrain elevation exhibits a mitigating effect. The SGTWR model demonstrates superior explanatory power and accuracy (adjusted R2 = 0.900) compared with traditional models, revealing significant spatial patterns and temporal trends in emission drivers. Based on coefficient clustering, six types of cities are identified, highlighting regional disparities in emission mechanisms. These findings provide methodological and theoretical support for formulating differentiated low-carbon transportation policies tailored to regional geographic and socio-economic contexts.

1. Introduction

As a significant source of global greenhouse gas emissions, transportation has been identified by the United Nations as a key area for sustainable development since the early 1990s, as outlined in Agenda 21. The second Global Conference on Sustainable Transport, held in 2021, further strengthened the consensus and action framework for global low-carbon transportation [,]. In recent years, China’s traffic scale has surged to the forefront of the world [], and urban traffic carbon emissions have continued to rise. According to statistics from the International Energy Agency (IEA), China’s carbon emissions in the transportation sector increased from 94 million tons to approximately 960 million tons between 1990 and 2021, a ninefold increase []. It has become a significant governance challenge under the “dual carbon” target []. Systematically identifying and analyzing the driving mechanism of urban TCE has become an important direction of current traffic carbon research. Revealing the key driving factors of urban TCE is helpful in scientifically guiding the formulation of low-carbon policies and improving the ability of green traffic governance at the city level [].

With the continuous expansion of carbon emissions and the increasingly severe climate and environmental problems, the academic community has conducted more in-depth research on the influencing factors of traffic carbon emissions. The methods used are primarily the STIRPAT model, LMDI model, GFI decomposition model, and GWR along with its extended model. For example, Wu et al. (2015) first used the ‘top-down’ algorithm to calculate the TCE in Gansu Province, and then dynamically analyzed the relevant influencing factors, established the STIRPAT influencing factor analysis model, and adopted the ridge regression method to solve the model []. Zhuang et al. (2017) employed the LMDI method to analyze the factors influencing TCE in Guangzhou []. The study found that the development level of the transportation industry, the transportation structure, and the number of private cars are the primary factors contributing to an increase in Guangzhou’s TCE. Wang et al. also used the LMDI method to decompose the influencing factors of carbon dioxide emissions in China’s passenger and freight transport sectors. The results indicate that economic factors contribute the most to the growth of carbon emissions in the passenger and freight transport sectors, while activity intensity can mitigate this growth []. Fan et al. used the GFI decomposition model to study the influencing factors of carbon emissions in Beijing’s transportation sector, including six factors such as energy structure and energy intensity. Their research results indicate that economic growth is the primary factor driving TCE, while transportation intensity is the primary factor reducing such emissions []. These methods are transparent in calculation and clear in interpretation; however, their disadvantage is that they cannot reflect spatial heterogeneity and regional interaction, making it difficult to reveal the differential influence mechanism between cities.

The GWR model can capture the spatial heterogeneity of carbon emissions between regions, especially when analyzing the impact of multivariate driving factors on carbon emissions, it provides a more accurate model through its local fitting ability [,,]. For example, Zeng Xiaoying et al. (2020) selected 30 provincial administrative units as spatial units, used the exploratory spatial data analysis (ESDA) method to study the spatial and temporal distribution pattern of TCE, and constructed a GWR model to analyze the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of the influencing factors of TCE []. Peng Zhao et al. (2024), based on the panel data of 284 prefecture-level cities in China from 2006 to 2020, used spatial measurement and GWR model to systematically analyze the influencing factors and spatial-temporal heterogeneity of urban TCE, and found that per capita GDP, population, urban road area and per capita private car are important factors leading to the increase in urban TCE []. In addition, the GTWR model is introduced to study urban TCE, which further improves the flexibility and accuracy of the GWR model in processing multi-dimensional spatio-temporal data [,,,,,].

Although existing research on TCE has made significant progress in analyzing spatial heterogeneity and spatial-temporal variability, it often overlooks the potential impact of attribute similarity on carbon emission patterns. The third law of geography states that similar regions often exhibit similar economic, social, and environmental characteristics, and this similarity is particularly important in the study of carbon emissions []. For example, regions with similar levels of economic development, urbanization and traffic demand often face similar energy consumption patterns and traffic flow patterns, resulting in similar carbon emission characteristics. Therefore, although many studies have considered the impact of spatial proximity on carbon emissions, they typically analyze it separately from attribute similarity, failing to reveal the complexity of the interaction between the two. This segmented analysis method does not fully enable us to understand the spatial dynamics of carbon emissions, the similarities between carbon emissions across regions, and the mechanisms of their changes, which in turn affect the predictive ability of the model and the effectiveness of policies.

The impact of climate and geographical conditions on urban TCE has received increasing attention. Climate factors, especially temperature changes, directly affect the mode of urban TCE. Studies have shown that temperature changes, especially under extreme weather conditions, significantly alter carbon emissions, and high temperatures or cold weather have a substantial impact on traffic travel patterns and carbon emissions [,]. In addition, geographical conditions, especially the undulating terrain, are also crucial to the impact of urban TCE [,]. Although natural factors such as climate and topography have been gradually considered in existing studies, there is a lack of systematic coupling analysis with social attribute factors such as traffic structure and economic activities, and a stable multi-dimensional interpretation model has not yet been formed. Therefore, it is of great theoretical and practical significance to study how these factors affect the dynamic change in TCE by altering traffic demand, travel mode, and transportation efficiency.

This paper proposes the SGTWR model, which offers advancements over traditional GWR and GTWR by seamlessly integrating attribute similarity weights with spatio-temporal kernels, thereby forming a comprehensive framework for capturing multi-dimensional heterogeneity. While GWR relies solely on geographic proximity to model spatial variation, and GTWR incorporates temporal dynamics to address time-varying relationships, SGTWR innovatively embeds attribute-based similarities into both spatial and temporal structures. This enables the model to dynamically weigh influences from non-adjacent yet functionally similar locations across evolving time horizons.

The objective of this study is to propose an innovative SGTWR model that integrates spatial proximity, attribute similarity, and temporal dimensions into a unified framework. Building upon this foundation, the model comprehensively incorporates other factors—such as climate, geographical conditions, and economic factors—to uncover the driving factors of transportation carbon emissions and their spatio-temporal heterogeneity.

The structure of this paper is as follows: The second part introduces the research methods and data sources; the third part first shows the spatial characteristics of urban TCE. Through the comparative analysis of different models (including OLS, GWR, SGWR, GTWR, and SGTWR), the advantages of the SGTWR model in explaining the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of TCE are verified. Combined with cluster analysis, the study examines the differences in driving factors of carbon emissions across various cities, revealing the spatial heterogeneity of carbon emissions between them. The fourth part discusses the mechanism of the influence of climate, geographical conditions and urban characteristics on the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of TCE and proposes a differentiated governance strategy based on urban type differences; the fifth part summarizes the main findings of the study and puts forward corresponding policy recommendations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

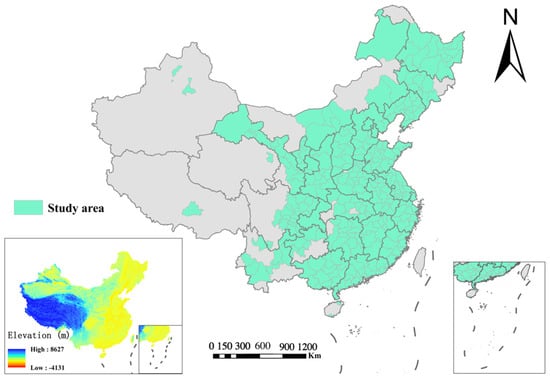

This study focuses on 287 cities in China as its research object (see Figure 1). The spatial scope covers megacities, core metropolitan areas, and small and medium-sized inland cities, forming a multi-level and whole-region urban system.

Figure 1.

Study area map and elevation map.

In terms of physical geography, the study area encompasses multiple climatic zones, ranging from the cold and arid areas in the northeast and northwest to the warm and humid regions along the southeast coast and southwest, exhibiting a pronounced heat gradient and spatial climate heterogeneity. There are various types of terrain. The eastern part features a plain and hilly landform, while the western part is mainly characterized by plateaus and mountains, with an altitude difference that can reach thousands of meters.

In terms of economic geography, the eastern coastal cities are economically developed, with complete transportation infrastructure, high motor vehicle density, and intensive carbon emissions. The central and western cities are undergoing rapid urbanization and industrialization, and the rapid evolution of the traffic structure is primarily manifested in the rapid growth of motor vehicle ownership and a shift in the proportion of public transportation and non-motorized transportation, resulting in a significant growth rate of carbon emissions. Although some northeastern cities are undergoing a period of economic transition, their transportation systems still exhibit a high energy intensity.

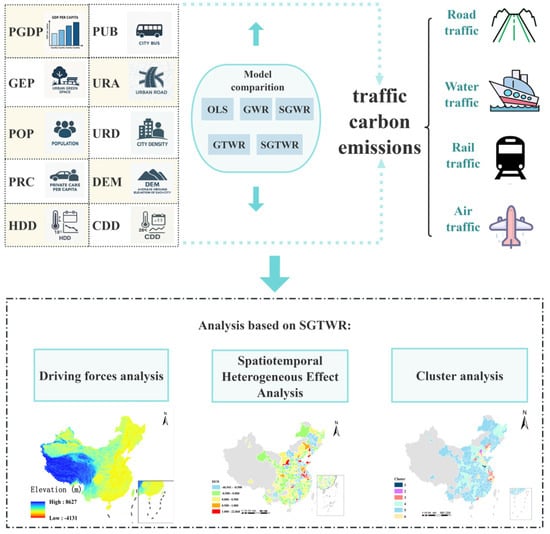

2.2. Research Framework

The research object of this paper is the urban TCE in China from 2000 to 2019. In this study, climatic and geographical factors, such as heating degree days (HDD), cooling degree days (CDD), geological elevation (DEM), and economic and social factors, such as total population at the end of the year (POP), population density (URD), per capita GDP (PGDP), per capita urban road area (PURA), green coverage of built-up areas (GEP), bus ownership per 10,000 people (PUB) and car ownership (PRC), were integrated into the analysis framework. By using ordinary least squares (OLS), geographically weighted regression (GWR), geographically weighted regression with time (GTWR) and GWR considering attribute similarity (SGWR) models for comparative verification, the spatial differences in the impact of various factors on urban TCE considering spatial-temporal heterogeneity and attribute similarity are discussed. Through cluster analysis, the differential responses of various types of cities to economic development, population, topography, and climate adaptability are identified, providing a theoretical basis for subsequent differential governance strategies. The research framework is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Research framework.

2.3. Variable Selection and Data Preprocessing

2.3.1. Variable Selection

Referring to previous studies and considering the current situation of the transportation industry, this paper selects 10 indicators, such as PGDP, as key factors affecting urban TCE. The definitions and measurements of each indicator are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data introduction.

It is worth explaining that in China, a country with a vast territory and four distinct seasons, climate differences in different regions and seasons have a significant impact on traffic travel behavior. However, the data studied in this paper are annual, so it is difficult to accurately reflect the dynamic climate environment faced by the transportation system by using the static index of ‘temperature’. Therefore, this study introduces HDD and CDD as alternative indicators []. These two indicators can more systematically characterize the cold and warm distribution of the annual climate and then reflect the changes in residents’ travel behavior under different climatic conditions, such as a decrease in travel frequency, a change in travel mode, and an increase in traffic energy consumption in cold or hot weather. These changes indirectly affect the carbon emission level of the urban transportation system. At the same time, geographical conditions are also a crucial factor that cannot be overlooked. The undulation of terrain not only restricts the layout and operational efficiency of transportation infrastructure but also directly affects the energy consumption performance of transportation, especially in mountainous or complex terrain areas. Therefore, this paper introduces the DEM as a quantitative variable of terrain.

2.3.2. Data Source

Considering the availability of data, this paper selects the annual data of 287 cities in China from 2000 to 2019 as the research sample. The urban TCE data are from the MEIC Model website, developed by the Department of Earth System Science at Tsinghua University (http://meicmodel.org.cn/, accessed on 3 November 2024). The platform provides an annual high-resolution TCE map with a spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°, covering carbon dioxide emissions from highways, railways, waterways, and air transport. To map the raster data to the city scale, this paper spatially superimposes the carbon emission raster data in the annual image with the administrative boundaries of each city. In this process, for each city, the carbon emission values of all grids within its administrative boundaries are extracted, and the grid data are aggregated to calculate the total TCE of the city each year. The data of other related variables come from the ‘China City Statistical Yearbook’ and the statistical yearbooks of provinces and cities. In order to maintain the consistency of data caliber, this paper gives priority to the data in the ‘China City Statistical Yearbook’. In cases where partial data is missing, the statistical yearbooks of provinces and cities are supplemented, and changes to administrative divisions and adjustments to statistical caliber are verified and corrected. The descriptive statistics of the original data are shown in Table 2. Before modeling, all data were standardized by Z-score to eliminate dimensional differences.

Table 2.

Data descriptive statistics table.

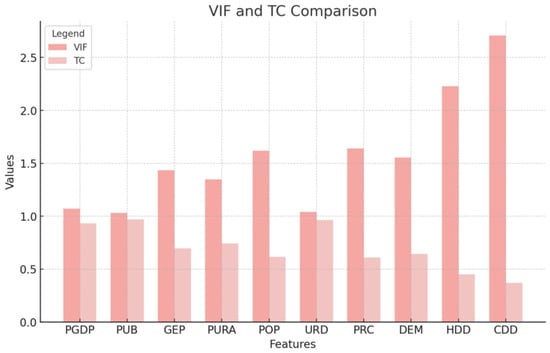

2.3.3. Multiple Collinearity and Correlation Test

Figure 3 illustrates the impact of the influencing factors on the variance inflation factor (VIF) and the tolerance coefficient (TC). VIF and TC are used to evaluate the multicollinearity in the regression model. The higher the VIF value, the stronger the multicollinearity, while the lower the TC value, the stronger the multicollinearity. It can be seen from the figure that the VIF values of most factors are lower than 2, which indicates that the collinearity between these factors and other variables is low, and there is almost no multicollinearity problem. In addition, the VIF values of HDD and CDD are relatively high, but still far from the threshold of multicollinearity problems. Although their VIF values are slightly higher, they do not indicate serious collinearity problems, so it can be considered that the correlation between these variables will not significantly impact the model’s stability.

Figure 3.

Multicollinearity test results.

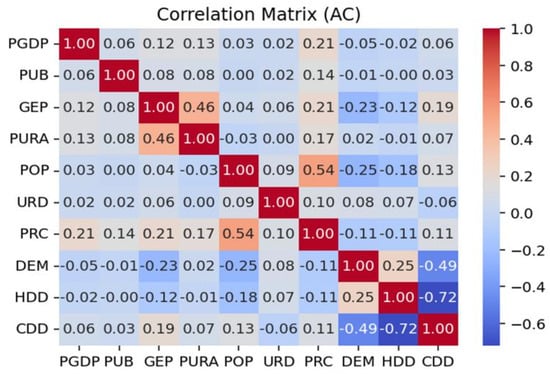

The correlation matrix shows the Pearson correlation coefficient between different factors. Figure 4 shows that the correlation between variables is moderate, and there is no obvious strong positive correlation or strong negative correlation. Specifically, the correlation coefficient between PUB and GEP was 0.46, showing a moderate positive correlation. The correlation coefficient between PURA and GEP is 0.460, indicating a moderate correlation between urbanization and economic growth. The correlation coefficient between PRC and POP is 0.540, indicating a strong positive correlation between the price level and urban total population. The correlation coefficient between HDD and CDD is −0.72, indicating a significant negative correlation between heating degree days and cooling degree days. The correlation between DEM and CDD is −0.49, indicating a significant negative correlation between average ground elevation and cooling degree days. The correlation between most variables is within a moderate range, and there is no obvious multicollinearity problem, indicating that the independence between these factors is strong and further regression analysis can be carried out.

Figure 4.

Correlation analysis.

2.4. Research Methods

2.4.1. OLS Model

Ordinary least squares (OLS) is a global regression method, assuming that the influence of independent variables on dependent variables is uniform and stable across space. In this model, the weights of all observations are equal, and it is assumed that there is no spatial dependence between variables. The specific regression equation is

Among them, yi is the traffic carbon emission of the city , β is the regression coefficient, x is the influencing factor, and ε is the error term.

2.4.2. GWR Model

The geographically weighted regression (GWR) model introduces spatial weights, allowing the regression coefficients to vary in space, thereby enabling the analysis of local effects at each spatial location. The GWR model formula is

represents the spatial coordinates of the city i, and is the local regression coefficient, which reflects the difference in the influence of different spatial locations.

2.4.3. GTWR Model

Based on the GWR model, GTWR incorporates the time factor []. The GWR model allows the regression coefficient to change spatially, while the GTWR is further extended to allow the regression coefficient to change both spatially and temporally (i.e., spatial-temporal heterogeneity). In this way, GTWR can describe the relationship between dependent variables and independent variables, and this relationship varies across geographical locations and over time.

The basic formula of the GTWR model is as follows:

Among them, is the dependent variable of the observed value i, is the spatial coordinates and time of the observed point i, is the regression coefficient of the independent variable estimated on the spatial position , and time , and is the error term.

The estimation formula of regression coefficient can be written as

Among them, is a weighted matrix, which considers the spatial and temporal distance between the observation point i and all other observation points.

The weighted matrix is crucial in GTWR, which is constructed based on the distance between space and time. The combination of spatial distance and temporal distance is as follows:

Among them, is the spatial distance, is the temporal distance, and and are the scale factors used to balance the influence of space and time.

Then, the weighted matrix is constructed by this comprehensive spatio-temporal distance, and the Gaussian attenuation function is used:

where is the bandwidth parameter that controls the decay rate.

2.4.4. SGWR Model

Based on the GWR model, the geographically weighted regression (SGWR) model with similarity further considers the interaction between attribute similarity and geographical proximity, which can reveal the spatial influence range of different factors []. The SGWR model introduces the weight of the spatial weighting matrix and the attribute similarity, so as to distinguish the spatial influence intensity of each variable under the consideration of spatial dependence and attribute similarity. The regression formula is

where is the dependent variable of the -th position; is a constant term, which varies with the spatial position ; is the regression coefficient of the th independent variable in position , which changes with the geographical position . is the th independent variable of the th city; is the error term of position .

In the SGWR model, the attribute similarity weight matrix () is introduced to measure the similarity between the location and other locations based on data attributes (such as economic level, population density, etc.). The calculation method of attribute similarity is as follows:

where () represents the distance between position and position on the -th attribute, and () is the -th attribute value of position . Then, the distance of all attributes is averaged:

where is the number of independent variables.

Using the above formula, the similarity weight is aligned with the GWR weight, where close to 1 indicates that the similarity is high, and close to 0 indicates that the attributes of the two positions are not similar.

After obtaining the geographic weight matrix and the attribute similarity weight matrix , they are combined into a final weight matrix . Among them, is a parameter that controls the relative contribution of geographical proximity weight and attribute similarity weight in the final weight matrix. The optimal value is determined by model evaluation to minimize the AICc (Akaike information criterion), thus ensuring the best fit of the model while avoiding over-fitting. In order to optimize the parameter, the divide-and-conquer method is used for iterative search.

After combining the geographic weight matrix and the attribute similarity weight matrix, the calculation formula of in SGWR becomes

2.4.5. SGTWR Model

The model is a weighted regression that combines geography, time dimension and inter-regional attribute similarity. The SGTWR model is an extension of the geographically weighted regression (SGWR) model that incorporates similarity, aiming to capture the spatial and temporal evolution more accurately, especially in the presence of significant spatial and temporal heterogeneity and regional attribute similarity.

The core idea of the SGTWR model is to introduce the spatio-temporal weighting matrix , and combine it with the attribute similarity weighting matrix of SGWR to form a comprehensive weighting matrix . These weighting matrices reflect the influence of geographical proximity, time difference and regional attribute similarity on the regression coefficients. Through such a weighting mechanism, the model can capture the heterogeneity between different spatial locations, time periods and similar attribute regions, and provide a more accurate analysis of the driving factors of traffic carbon emissions.

Given n observation points, the data of each observation point i include: space-time position , covariate vector , response variable . Local fitting model for each location i:

The regression coefficient varies with location and time.

For point i, define the weighted least squares objective function:

Here, Wij is the comprehensive weight of point j to point i, which will be described in detail later. Ji (β) is expressed in matrix form as

Let Wi = diag(wi1, …, win) ∈ Rn×n, x = [x1, …, xn]T ∈ Rn×p, y = [y1, …, yn]T ∈ Rn,

Then

The spatio-temporal weighting matrix WST is used to reflect the influence of spatio-temporal dimension, and the weight decreases with the increase in spatio-temporal difference. The expression of the WST is

where WST (ui, vi, ti) is the spatio-temporal weight matrix centered at location i with coordinates (ui, vi) and time ti; ds and dt denote the spatial and temporal distances, respectively; and hs and ht are the corresponding bandwidth parameters.

The attribute similarity weighting matrix WS describes the influence of attribute similarity. In order to comprehensively consider the role of space-time and attributes, the SGTWR model combines them to form a new weighted matrix Wi. The specific formula is:

Among them, the attribute bandwidth of SGTWR is 1, α and γ are the parameters that control the weighted influence of space-time and attribute similarity, satisfying

The computation of WS (ui, vi, ti) follows the WS (ui, vi) calculation in SGWR (Equations (9)–(11)). WS (ui, vi, ti) employs a static formulation because inter-annual variation within similar clusters is relatively low (e.g., GDP in eastern cities with comparable development levels). Static computation directly captures this intra-cluster coefficient stability, thereby stabilizing model coefficients and avoiding explanatory bias.

Derivation of Ji (β) with respect to β and let it be zero:

Gradient for β:

Let ▽βJi = 0, get the normal equation:

Suppose is invertible, then

For feature of point i, predict

Weighted residual sum of squares:

For point i, the sample size is n, the trace of the comprehensive weight matrix , AICc is

In the SGTWR model, parameter optimization uses genetic algorithm (GA) to adjust the time bandwidth, the number of nearest neighbors K and the weight coefficient. GA is optimized by simulating the natural selection process. The initial population is composed of multiple randomly selected individuals, each of which represents a set of possible parameter values. Through crossover, mutation and other operations, the population is gradually optimized, and cross-validation (CV) is used to evaluate the fitness of each individual. The fitness function measures the fitting effect of the model by calculating the AICc value and finally selects the parameter combination with the best AICc value as the optimal parameter.

2.5. Model Evaluation Index

In this study, in order to comprehensively evaluate and compare the fitting effects and explanatory power of different regression models (OLS, GWR, SGWR and SGTWR), we selected four commonly used model evaluation indicators: adjusted R2, AICc, RMSE and MAE. These indicators can reflect the model’s fitting accuracy and predictive ability from different angles.

The adjusted R2 is an important index to measure the goodness of fit of the regression model. It is modified based on the ordinary R2, taking into account the number of independent variables, thus avoiding the overfitting problem that may be introduced when the number of independent variables is too large. The formula for adjusting R2 is

Among them, R2 is the ordinary value, n is the sample size, and p is the number of independent variables. The closer the adjusted R2 is to 1, the better the model fitting effect is.

AICc is a modified Akaike information criterion for model selection. AICc helps select the optimal model by balancing the model’s fit and complexity. The smaller the AICc value, the better the model. The calculation formula of AICc is

Here, RSS is the residual sum of squares of the model, tr(S) is the trace of matrix S, and n is the sample size. The smaller the AICc value, the better the performance of the model. The calculation formula of RSS is

Among them: Y is the observed value vector of the dependent variable, S is the weighted matrix, and I is the unit matrix.

The root mean square error is an index used to measure the difference between the predicted value of the model and the actual observation value, which reflects the accuracy of the model prediction. The smaller the RMSE, the smaller the prediction error of the model, and the better the fitting effect. The calculation formula of RMSE is

Among them, yi is the observed value, is the predicted value, and n is the sample size. The smaller RMSE indicates that the prediction accuracy of the model is higher.

The mean absolute error is another commonly used error evaluation index that measures the average difference between the predicted value of the model and the actual observed value. Unlike RMSE, MAE is not affected by extreme errors and provides a direct measure of the size of the error. The calculation formula of MAE is

Among them, yi is the observed value, is the predicted value, and n is the sample size. The smaller the value of MAE, the lower the prediction error of the model and the better the performance of the model.

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Traffic Carbon Emissions

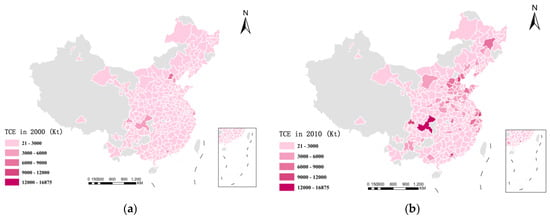

From 2000 to 2019, China’s urban TCE exhibited a significant spatial-temporal growth and evolution trend, with an overall performance characterized by a gradual spatial transfer pattern expanding from the eastern coast to the central and western inland regions (Figure 5). In the early stages of the study, carbon emissions were highly concentrated in the first-tier coastal cities with developed economies, dense populations, large motor vehicle ownership, and excellent transportation infrastructure, such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. However, in the central and western regions, due to the low level of urbanization, an imperfect transportation system and limited motor vehicle ownership, the overall carbon emissions were at a low level. After entering 2010, with the rapid development of the national economy and the rise of second-and third-tier cities, the inland areas, especially the core cities in the central and western regions such as Chengdu, Wuhan, and Chongqing, have accelerated the urbanization process, surged in traffic demand, and rapidly increased the number of motor vehicles. Infrastructure investment continues to increase and gradually evolves into a new carbon emission growth pole []. By 2019, the spatial pattern of transportation carbon emissions tends to be balanced. The carbon emissions of many cities in the central and western regions and northeast regions, such as Zhengzhou, Xi’an and Shenyang, have increased significantly, gradually breaking the original spatial pattern of ‘coastal dominance’ and forming a dual-core emission structure with equal emphasis on coastal-inland and echoing from east to west. From the perspective of total amount, traditional coastal cities still occupy a dominant position, but the incremental contribution of inland cities is increasingly prominent, which indicates that the carbon emission pattern of urban transportation in China is changing from single center to multi-center, and it also shows that the future low-carbon governance needs to pay more attention to the emission pressure and governance capacity of the rising regions in central China and emerging urban agglomerations.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of urban traffic carbon emissions. (a) TCE in 2000; (b) TCE in 2010; (c) TCE in 2019; (d) 2000–2019 Total TCE.

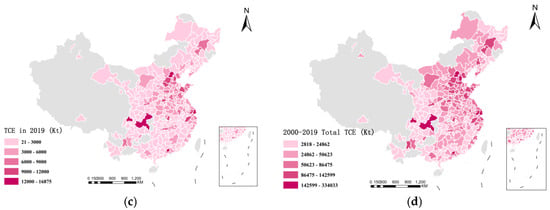

From 2000 to 2019, the evolution of the standard deviation ellipse (SDE) of urban TCE in China reveals significant spatial and temporal dynamic changes (Figure 6). During the period from 2000 to 2010, the center of gravity of carbon emissions continued to shift northward. The elliptical axis was significantly elongated along the northeast-southwest direction, reflecting that the coastal and northeastern regions took the lead in completing the expansion of carbon emissions driven by the construction of transportation infrastructure and the popularization of motor vehicles during this period. At this stage, the high traffic demand and economic growth are synchronized, resulting in the spatial advance of carbon emissions from east to west and from coast to inland. In 2010–2019, the center of gravity of carbon emissions began to move southward, and by 2019, it basically returned to the latitude before 2000. At the same time, the long axis and short axis of SDE were shortened synchronously, and the spatial dispersion and expansion range of carbon emissions tended to converge. This phenomenon mainly benefits from the rapid increase in traffic network density in the central region, especially in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River and the urban agglomerations along the Yangtze River in the south during the ‘Twelfth Five-Year Plan’ and ‘Thirteenth Five-Year Plan’, and the level of infrastructure construction is gradually approaching the eastern coast, which promotes the transfer of TCE from outward expansion to agglomeration. On the whole, the main axis of the standard deviation ellipse has always been stably extended along the northeast-southwest direction throughout the study period, which is in line with the spatial economic structure of the “Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei-Yangtze River Delta-Pearl River Delta” national urban corridor [], indicating that the axis not only constitutes the main belt of China’s economy and population flow, but also becomes the regional channel with the most concentrated TCE.

Figure 6.

SDE analysis.

3.2. Comparative Analysis of Models

Appendix A Table A1 presents the Moran’s I values for the residuals of the OLS model. All Moran’s I values are significantly positive, indicating that the OLS model fails to capture spatial dependence and thus necessitates the adoption of spatio-temporal models to better explain the data.

To systematically evaluate the modeling effect of urban TCE, this paper compares the performance of OLS, GWR, SGWR, GTWR, and SGTWR models in terms of R2, AICc, MAE, RMSE, and RSS. As shown in Table 3, the SGTWR model outperforms the other models in all evaluation indicators, demonstrating significant fitting advantages and improved prediction accuracy. Its adjusted R-squared is up to 0.900, and its explanatory power is significantly stronger than that of OLS (0.678), GWR (0.746), SGWR (0.842), and GTWR (0.855). The AICc value is −13,201.319, which is the lowest among the five, indicating that the information loss is the smallest and the fitting is the best. In terms of error control, the MAE and RMSE of SGTWR are 0.203 and 0.316, respectively, which are significantly better than spatial models such as GWR and SGWR. The residual sum of squares (RSS) is only 572.849, which is much lower than OLS (1848.003) and GWR (1456.331).

Table 3.

Comparison of model results.

Appendix A Table A2 presents the robustness checks for the SGTWR model, demonstrating through re-runs omitting key variables (POP, PRC, HDD, DEM) that the full model significantly outperforms sub-models in fit and error metrics.

3.3. Analysis of Influencing Factors

According to the statistical data of SGTWR coefficients (see Table 4), the four factors that have the most significant impact on TCE are POP, PRC, DEM and HDD. First of all, the average regression coefficient of PRC is 0.457 and the standard deviation is 0.323, indicating that there is a positive correlation between the popularity of private cars and TCE. In most cities, the increase in the number of private cars directly promotes the increase in TCE, especially in economically developed cities with imperfect public transportation, where the increase in private car ownership is particularly significant. Secondly, the average regression coefficient of POP is 0.423, and the standard deviation is 0.389, indicating that there is a significant positive correlation between population density and TCE in most cities. Cities with higher population density usually face higher traffic demand and traffic congestion, resulting in higher carbon emissions. The average regression coefficient of DEM is −0.410, which shows that there is a negative correlation between topographic elevation and TCE, which means that cities with large terrain fluctuations usually have low traffic density and low carbon emissions. Although vehicles in high terrain elevation areas need to overcome greater terrain resistance, the overall carbon emissions are limited due to the small size of cities in these areas and low traffic demand. The mean regression coefficient of HDD is 0.261, and the standard deviation is 0.538, which shows the positive impact of cold season climate on TCE. Under the condition of low temperature in winter, the frequency of residents’ private car travel increases and the traffic energy consumption increases, which in turn promotes the increase in TCE.

Table 4.

Regression coefficient statistical table.

In addition, the average regression coefficients of PGDP and PUB are 0.144 and 0.141, respectively, and the standard deviations are all around 0.190, indicating that they have a weak but stable positive impact on TCE. In cities with more developed economies or higher levels of public transport, traffic activity is generally more frequent, resulting in a slight increase in carbon emissions. The average regression coefficients of PURA and URD were 0.057 and 0.037, respectively, which had little effect. The average coefficient of GEP is only 0.035, and some cities even have negative effects, indicating that it has a limited regulatory effect on TCE at the current stage. In addition, the average regression coefficient of CDD is −0.082, which shows a certain negative correlation, which may be related to the decrease in travel frequency and the change in travel mode during the high temperature period. In general, although the impact of these secondary factors is relatively small, they still affect the level of TCE to a certain extent.

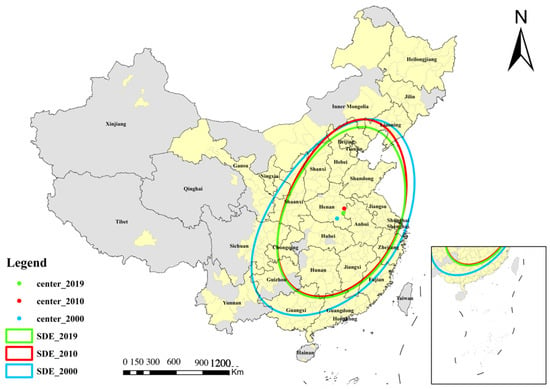

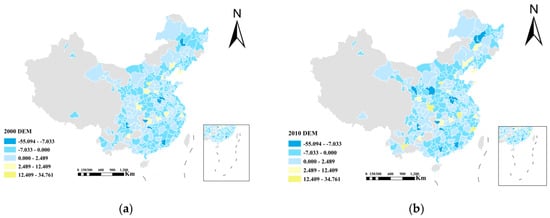

3.4. Spatial-Temporal Heterogeneity Effect Analysis

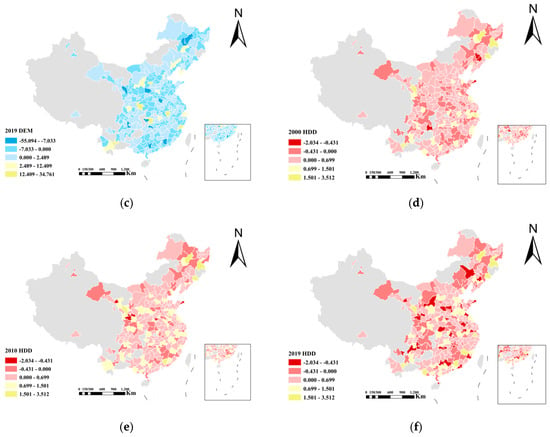

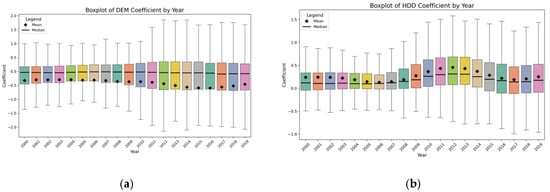

In order to deeply understand the heterogeneity of geographical and climatic factors in the driving mechanism of urban TCE, this paper systematically analyzes the two representative variables of DEM and HDD based on the regression coefficient results of the SGTWR model. Figure 7 shows the spatial and temporal distribution of the fitting coefficients of DEM and HDD, and Figure 8 shows the box plot of the regression coefficients of DEM and HDD from 2000 to 2019.

Figure 7.

The spatial and temporal distribution of the fitting coefficients of DEM and HDD derived from SGTWR. (a) 2000 DEM; (b) 2010 DEM; (c) 2019 DEM; (d) 2000 HDD; (e) 2010 HDD; and (f) 2019 HDD.

Figure 8.

Box plot of DEM and HDD fitting coefficients from 2000 to 2019. (a) Boxplot of DEM coefficient by Year; (b) Boxplot of HDD coefficient by Year.

From the perspective of time trend, the regression coefficient between DEM and TCE is negative as a whole, and its mean value continues to decline from 2000 to 2015, from −0.330 to −0.590, indicating that the inhibition of terrain on traffic development has increased significantly during this period. This trend is highly related to the weak urban traffic foundation and limited traffic development in the western region. After 2015, the mean value of DEM coefficient gradually rebounded and reached −0.460 in 2019, indicating that with the continuous improvement of infrastructure in the west (such as the extension of highways and rail transit), the inhibitory effect of topography on carbon emissions has weakened, and even reverse effects have appeared in some cities. Spatially, the southwest and northwest regions have always shown a significant negative correlation, such as Guiyang, Kunming, Lhasa and other places with low coefficients, reflecting that their complex terrain has a strong restriction on traffic activities. However, the eastern coastal cities showed a clear trend of change. In 2000, most cities were still in the negative correlation interval. In 2010, some cities had a coefficient close to 0. By 2019, some cities such as Ningbo, Xiamen, Guangzhou and so on even turned into positive correlation, indicating that the terrain no longer restricts traffic development. Instead, it may push up TCE by extending urban boundaries and increasing commuting distance.

In contrast, the regression coefficient of the HDD variable is positively correlated as a whole, reflecting the increase in travel demand and traffic energy consumption under cold climate conditions. The mean value increased from 0.240 to 0.460 between 2000 and 2012, and then fluctuated around 0.250, showing a trend of ‘rising first and then stabilizing’. This change shows that the response to cold climate in early cities is mainly reflected by traffic activities (such as private car travel, warm car waiting, etc.), and then with the promotion of clean heating, public transport system optimization and other measures, the role of HDD in promoting carbon emissions tends to be stable. In terms of spatial distribution, the northern alpine regions (such as Harbin, Changchun, Hohhot) have always maintained a strong positive correlation, and the coefficient is generally higher than the national average; the positive correlation between central regions such as Taiyuan and Shijiazhuang increased significantly around 2010, indicating that the impact of climate on TCE has shifted southward. In the southern region (such as Nanning and Sanya), the coefficient is small or even negative, indicating that under the background of warm and hot climates, the effect of HDD on TCE is not significant, and even in some years, the frequency of travel decreases with the decrease in temperature.

In summary, the regression coefficients of DEM and HDD show a certain trend in time series. The former increases from negative to partially weakened, while the latter experiences a process of rising first and then stabilizing. In space, DEM shows a transition from general inhibition to regional differentiation, while HDD maintains a high-impact area dominated by northern cities.

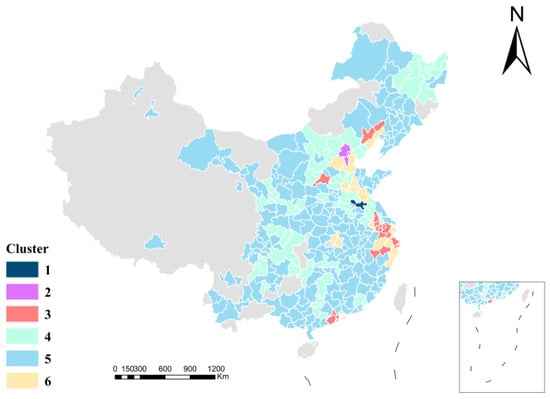

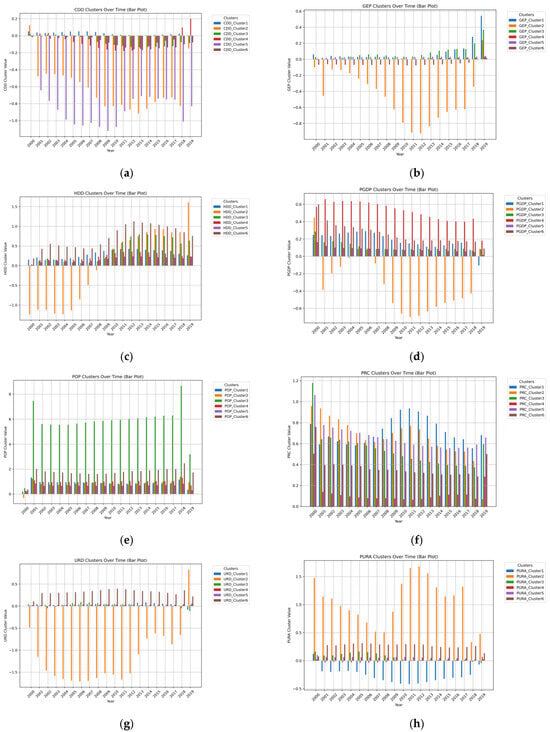

3.5. Cluster Analysis

According to the cluster analysis of 287 cities in China based on the regression coefficient, the cities in the study area are divided into six categories (see Figure 9). The time trend of the regression coefficients of the influencing factors of each category is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 9.

Clustering results.

Figure 10.

Time trend of regression coefficients of each category. (a) CDD; (b) GEP; (c) HDD; (d) PGDP; (e) POP; (f) PRC; (g) URD; and (h) PURA.

According to the results of cluster analysis, the improvement of green infrastructure and public transportation networks has led to a stable growth rate of TCE in the first type of cities, gradually alleviating pressure on emissions. In contrast, type 2 cities relied on high-density development and public transportation to curb carbon emissions in the early stages, but with urban expansion and diversification of travel modes, overall emissions fluctuated, despite a slight decline in private car ownership. The third category consists mostly of developed cities on the southeast coast, which are highly sensitive to fluctuations in population size and climate change. TCE pressure fluctuates greatly with seasons and population mobility. Category 4 primarily encompasses cities in high-cold regions. Due to the intense winter heating demands and high reliance on private vehicles, the impact of climatic factors on transportation emissions is particularly pronounced, with carbon emission levels exhibiting marked fluctuations in tandem with the severity of the cold. The fifth category is small and medium-sized cities such as Sanya and Shangluo. The overall TCE level is low and stable. However, when encountering extremely high temperatures or severe cold weather, it will still be affected by changes in demand for cold and warm products in the short term, and sensitive fluctuations will occur. The sixth category includes economic core areas such as Shanghai, Nanjing, and Tianjin. Although the total carbon emission is the largest, the growth in emissions has tended to be gentle due to a well-developed public transportation system, continuous policy regulation, and green travel promotion.

In general, a policy system of “partition classification and local conditions” should be established. Different strategies should be adopted for different types of cities: For the first category of cities that have achieved green transformation, consolidate achievements and optimize mechanisms—implement dynamic carbon audit incentives and strengthen low-carbon pathway locking to avoid rebound. For the second category of cities with significant fluctuations in carbon structure or sensitivity to climate change, enhance system resilience and emergency response capabilities—deploy AI carbon early warning platforms and establish emergency event buffer funds to improve adaptability. For the third category of cities constrained by natural factors, improve the adaptability of alternative transportation and infrastructure—provide subsidies for resilient alternatives and prioritize ecological network upgrades to address bottlenecks. For the fourth category of super-large urban agglomerations radiating to surrounding areas, drive low-carbon travel networks through regional coordination—lead cross-city carbon trading hubs and shared rail alliances and integrate monitoring sharing to build governance chains. For the fifth category of emerging development catch-up cities, accelerate green leapfrogging and monitoring support—launch development funds and carbon platform pilots and cultivate low-carbon skill chains.

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanism Discussion

By using the STGWR model, this study provides a comprehensive analysis of the spatio-temporal distribution characteristics and driving mechanisms of urban TCE in China, revealing the spatio-temporal heterogeneity and complexity of TCE across different regions. The research indicates that the distribution of transportation carbon emissions is not only influenced by economic, social, and transportation infrastructure factors, but also significantly affected by climatic conditions and geographical characteristics. The spatial and temporal heterogeneity of these factors has brought complex changes to the city’s TCE patterns [].

Specifically, DEM has long been a negative impact factor, indicating that high altitude and undulating terrain inhibit traffic development. However, this inhibitory effect has periodic changes and spatial differentiation trends. From 2000 to 2015, the negative impact of DEM gradually increased, indicating that the western and mountainous cities are more restricted by terrain when the transportation infrastructure is not perfect. After 2015, with the advancement of traffic suitability projects in plateau cities, such as the construction of tunnels, elevated roads and expressway networks, the impact of DEM began to weaken, and some eastern cities even showed positive correlation coefficients, reflecting that terrain is no longer an obstacle to carbon emissions but may become an incentive for urban spatial expansion and commuting distance growth. This trend reveals that the ability of cities to adapt to natural constraints has become a key variable affecting the carbon emission path. Secondly, as a climate-driven variable, the positive correlation of HDD shows stronger stability and regional aggregation. The driving effect of HDD on traffic carbon emissions is mainly concentrated in the cold regions of the north, reflecting the phenomenon of frequent traffic activities and high energy consumption intensity in winter. In terms of time, the impact of HDD increased significantly between 2000 and 2012, and then stabilized, possibly benefiting from policy interventions such as heating efficiency improvement and green travel promotion. At the same time, the impact of HDD in southern cities is always weak, and even negatively correlated in some years.

Through cluster analysis, this study found that China’s urban TCE system showed significant type differentiation, mainly reflected in multiple dimensions such as economic development stage, population density, transportation system maturity and response mechanism to climate disturbances. There are systematic differences in the sensitivity of carbon emission driving factors in different cities: some cities have established a relatively stable low-carbon travel structure, showing a preliminary decoupling between economic growth and carbon emissions; Other cities are faced with a rigid carbon emission structure driven by rising private car use or extreme climate, and it is difficult to control carbon emissions. In addition, cities exhibit varying adaptive capacity and governance performance in response to climate change (such as cold or high temperatures) and rapid urban expansion, resulting in a high degree of spatial and temporal heterogeneity in carbon emission systems. This multi-type coexistence pattern shows that China’s urban traffic carbon governance may start from ‘classification and identification’ and build a differentiated governance path of structural response and system adaptation. These research results provide quantitative evidence for China’s “dual-carbon” strategy. Specifically, transportation carbon emission policies tailored for different regions can help high-emission cities accelerate the transition to green transportation methods, thereby contributing to the achievement of the country’s carbon emission peak and carbon neutrality goals.

4.2. Limitations and Future Work

This study introduces the SGTWR model, which improves the explanatory strength and predictive stability of the driving factors by jointly weighting the spatio-temporal proximity and attribute space. Although the results have strong explanatory power, this study still faces many limitations. First, this study assumes that the effects of covariates (such as PGDP and PRC, etc.) on the response variable (TCE) are unidirectional. However, in reality, there may be bidirectional causal relationships between PGDP and PRC and TCE. Secondly, the climate data use annual-scale HDD and CDD indicators, and the high-frequency disturbance effects in the context of intraseasonal variability or frequent extreme weather have not been considered. In the future, daily-scale or weekly-scale meteorological data can be introduced to model short-term climate response mechanisms. Thirdly, the model hypothesis does not explicitly introduce institutional variables such as traffic management measures, energy prices, and vehicle regulations reform, which may miss the non-linear structural impact of some policy interventions. Finally, this study does not explicitly consider the impact of emerging transportation technologies such as Connected and Automated Vehicles (CAVs). As CAVs become increasingly integrated into mixed traffic environments, they are expected to significantly reshape traffic flow efficiency and carbon emission patterns. Existing research indicates that with higher CAV penetration rates, cooperative control and communication mechanisms can greatly enhance intersection capacity and reduce vehicle delays, thereby indirectly promoting the formation of a low-carbon transportation system []. Furthermore, limitations also include annual data masking seasonal variations, MEIC emission uncertainties, computational complexity, and so on.

Future research could be further developed in the following directions: (1) introducing dynamic panel models with lag structures to capture the medium- and long-term effects of policy responses and institutional changes on carbon emission evolution; (2) integrating machine learning methods (such as XGBoost and LSTM) with SGTWR for multi-model integration optimization, enhancing predictive robustness; (3) when constructing the attribute similarity distance, we use equal weighting, which implicitly assumes that the contributing factors have relatively balanced contributions to “urban attribute similarity.” In the future, this can be extended to entropy-weight optimization, where relative importance is automatically assigned through information entropy, thus capturing non-stationary mechanisms more comprehensively.

5. Conclusions

Focusing on 287 prefecture-level cities and above in China, this study constructs an SGTWR that integrates geographic proximity, attribute similarity, and time evolution dimensions to analyze the driving factors of urban TCE from 2000 to 2019. The model further introduces the attribute similarity dimension on the basis of GWR and GTWR and innovatively captures the cross-geographic and the same type of spatial transmission effect affected by variables. It is significantly better than the traditional model in terms of fitting accuracy, residual control and spatio-temporal elasticity recognition. The results show that POP, PRC and HDD are the main positive factors, while DEM plays an inhibitory role in most areas. Due to the differences in infrastructure effect, environmental background and population structure, there are obvious stage and regional differences in carbon emission characteristics among cities.

Based on this, this paper proposes three aspects of policy recommendations: first, proactive intervention in the high-carbon risks of mid-western expansion-type cities, with rational layout of transportation structures. Taking Type 2 medium-balanced cities such as Jinan and Type 5 small-fluctuating cities such as Sanya and Shangluo as examples, the expansion process is prone to exacerbating emission fluctuations. It is recommended to establish an expansion risk assessment mechanism, simulate and predict hotspot areas, and formulate sustainable transportation orientation guidelines. Second, incorporate terrain and climate into the carbon quota system to enhance policy equity and adaptability. For Type 4 high-latitude cold cities such as Harbin and Type 3 southeastern coastal developed cities such as Ningbo, climate and terrain factors highlight regional differences. Policies should formulate differentiated governance strategies to alleviate emission inequities under natural constraints and enhance policy resilience. Third, establish a dynamic monitoring system to improve early warning capabilities and emergency response levels for highly sensitive cities. Spatio-temporal heterogeneity underscores cross-regional fluctuation risks, necessitating the establishment of an experience-sharing platform to promote the dissemination and iterative optimization of advanced low-carbon practices, thereby building an efficient governance closed loop through collaborative networks and achieving an inclusive carbon reduction ecosystem.

This study introduces the attribute similarity dimension to describe the spatial heterogeneity of urban TCE for the first time and incorporates terrain and climate factors into a unified analysis framework, which provides a new reference for the management of relevant departments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L. and W.D.; methodology, M.L., W.D., Z.H. and S.Y.; software, M.L., Z.H. and D.Z.; validation, M.L. and W.D.; formal analysis, M.L., Y.H. and W.D.; data curation, Z.H., M.L., W.D. and L.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.; writing—review and editing W.D., Z.H. and S.Y.; supervision, W.D.; project administration, W.D., Z.H. and S.Y.; funding acquisition, W.D., Z.H. and S.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Inner Mongolia Science and Technology Plan (2024KJHZ0007, 2024KJHZ0002, 2022YFSH0027), the Inner Mongolia’s “Science and Technology” Action Key Project (2020ZD0028), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81860605), the Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia (No.2023MS01001, No. 2020MS01005), and the Basic Scientific Research Business Expense Project of Colleges and Universities Directly under Inner Mongolia (No. ZTY2025063).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is available by emailing the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the support of the Arxan Forest and Grassland Disaster Prevention and Mitigation Field Scientific Observation and Research Station of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Results of the spatial autocorrelation test for OLS residuals.

Table A1.

Results of the spatial autocorrelation test for OLS residuals.

| Moran’s I Test for Residuals of Global Models | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Moran’s I | Z-Value | p-Value |

| 2000 | 0.247 | 3.425 | 0.001 |

| 2010 | 0.196 | 2.604 | 0.009 |

| 2019 | 0.051 | 0.774 | 0.039 |

Table A2.

Robustness Checks for the SGTWR Model.

Table A2.

Robustness Checks for the SGTWR Model.

| Model | AICc | MAE | RMSE | RSS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGTWR | 0.900 | −13201.319 | 0.203 | 0.316 | 572.849 |

| Omitting POP Model | 0.888 | −13180.456 | 0.208 | 0.320 | 583.012 |

| Omitting PRC Model | 0.892 | −13192.134 | 0.205 | 0.318 | 576.945 |

| Omitting HDD Model | 0.886 | −13175.289 | 0.207 | 0.319 | 580.234 |

| Omitting DEM Model | 0.895 | −13198.567 | 0.209 | 0.324 | 574.621 |

Table A3.

Categories of each city.

Table A3.

Categories of each city.

| Cluster | City |

|---|---|

| 1 | Xuzhou. |

| 2 | Beijing, Langfang. |

| 3 | Zhongshan, Foshan, Jiaxing, Ningbo, Changzhou, Yangzhou, Wuxi, Jinzhong, Chaoyang, Jiangmen, Huzhou, Suzhou, Quzhou, Jinhua, Zhenjiang, Fuxin. |

| 4 | Zhongwei, Ulanqab, Yunfu, Bozhou, Yichun, Jiamusi, Liupanshui, Nanchang, Shuangyashan, Lvliang, Hohhot, Xianyang, Harbin, Tangshan, Shangqiu, Guyuan, Datong, Taiyuan, Dingxi, Yibin, Suqian, Bazhong, Pingliang, Guangyuan, Kaifeng, Zhangjiakou, Dezhou, Xinzhou, Huaihua, Chengde, Zhaotong, Jincheng, Zaozhuang, Meizhou, Wuzhou, Yongzhou, Shantou, Taizhou, Jining, Haikou, Huaian, Weinan, Chuzhou, Chaozhou, Jiaozuo, Mudanjiang, Yiyang, Qinhuangdao, Suihua, Zigong, Heze, Pingxiang, Hengshui, Hengyang, Xi’an, Hezhou, Dazhou, Lianyungang, Xingtai, Handan, Chongqing, Tongren, Changsha, Hegang. |

| 5 | Qitaihe, Sanya, Sanming, Sanmenxia, Shangrao, Dongying, Linfen, Lincang, Dandong, Lishui, Lijiang, Wuhai, Urumqi, Leshan, Jiujiang, Baoshan, Xinyang, Karamay, Lu’an, Lanzhou, Neijiang, Baotou, Beihai, Shiyan, Nanchong, Nanning, Nanping, Nantong, Nanyang, Xiamen, Hefei, Ji’an, Jilin, Wuzhong, Zhoukou, Hulunbuir, Xianning, Shangluo, Jiayuguan, Siping, Daqing, Dalian, Tianshui, Weihai, Loudi, Ningde, Anqing, Ankang, Anyang, Anshun, Yichang, Yichun, Baoji, Xuancheng, Suzhou, Yueyang, Chongzuo, Bayannur, Changde, Pingdingshan, Guang’an, Guangzhou, Qingyang, Yan’an, Zhangjiajie, Zhangye, Deyang, Huizhou, Chengdu, Fuzhou, Fushun, Lhasa, Jieyang, Panzhihua, Xinxiang, Xinyu, Rizhao, Kunming, Pu’er, Jingdezhen, Qujing, Shuozhou, Benxi, Laibin, Songyuan, Liuzhou, Zhuzhou, Guilin, Yulin, Wuwei, Bijie, Hanzhong, Shanwei, Chizhou, Shenyang, Hechi, Heyuan, Quanzhou, Luzhou, Luoyang, Zibo, Huaibei, Huainan, Qingyuan, Xiangtan, Zhanjiang, Binzhou, Luohe, Zhangzhou, Weifang, Puyang, Yantai, Yulin, Yuxi, Zhuhai, Baicheng, Baishan, Baiyin, Baise, Yancheng, Panjin, Meishan, Shizuishan, Shijiazhuang, Fuzhou, Mianyang, Zhaoqing, Wuhu, Maoming, Jingzhou, Jingmen, Putian, Yingkou, Bengbu, Xiangyang, Xining, Xuchang, Guigang, Guiyang, Ziyang, Ganzhou, Chifeng, Liaoyuan, Liaoyang, Yuncheng, Tonghua, Tongliao, Suining, Zunyi, Shaoyang, Zhengzhou, Chenzhou, Ordos, Ezhou, Jiuquan, Jinchang, Qinzhou, Tieling, Tongchuan, Tongling, Yinchuan, Changchun, Changzhi, Fuyang, Fangchenggang, Yangjiang, Yangquan, Longnan, Suizhou, Ya’an, Qingdao, Anshan, Shaoguan, Ma’anshan, Zhumadian, Jixi, Hebi, Yingtan, Huanggang, Huangshan, Huangshi, Heihe, Qiqihar, Longyan. |

| 6 | Shanghai, Dongguan, Linyi, Baoding, Nanjing, Taizhou, Tianjin, Xiaogan, Hangzhou, Wuhan, Cangzhou, Tai’an, Jinan, Shenzhen, Wenzhou, Shaoxing, Liaocheng, Zhoushan, Huludao, Jinzhou. |

References

- United Nations. Agenda 21: Programme of Action for Sustainable Development, Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, Statement of Forest Principles: The Final Text of Agreements Negotiated by Governments at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), 3–14 June 1992, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; United Nations Department of Public Information: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Report of the Second United Nations Global Sustainable Transport Conference; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Statistical Yearbook 2023; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). CO2 Emissions from Fuel Combustion; IEA Publications: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- State Council of China. Guiding Opinions on Completely, Accurately, and Comprehensively Implementing the New Development Philosophy and Achieving Carbon Peak and Carbon Neutrality; State Council of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Zhang, J.; Jia, R.; Yang, H.; Dong, K. Does electric vehicle promotion in the public sector contribute to urban transport carbon emissions reduction? Transp. Policy 2022, 125, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Xiong, J.; Wu, W.; Gao, W.; Liu, X. Calculation and effect factor analysis of transport carbon emission in Gansu Province based on STIRPAT Model. Glaciol. Geocryol. 2015, 37, 826–834. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, Y.; Xia, B. Guangdong Province’s traffic carbon emissions accounting and influencing factors analysis. Res. Environ. Sci. 2017, 30, 1154–1162. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Sun, Y.F.; Chen, Q.X.; Wang, Z. Determinants analysis of carbon dioxide emissions in passenger and freight transportation sectors in China. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2018, 47, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.Y.; Lei, Y.L. Decomposition analysis of energy-related carbon emissions from the transportation sector in Beijing. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2016, 42, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Shi, C.; Fang, C.; Feng, K. Examining the spatial variations of determinants of energy-related CO2 emissions in China at the city level using Geographically Weighted Regression Model. Appl. Energy 2019, 235, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Fang, C.; Ma, H.; Wang, Y.; Qin, J. Spatial differences and multi-mechanism of carbon footprint based on GWR model in provincial China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2014, 24, 612–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, Q.; Huang, F.; Qiu, R.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, L.; Hu, X. Understanding spatial variation in the driving pattern of carbon dioxide emissions from the taxi sector in great Eastern China: Evidence from an analysis of geographically weighted regression. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2020, 22, 979–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.-Y.; Qiu, R.-Z.; Lin, D.-T.; Hou, X.-Y.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Hu, X.-S. Spatio-temporal heterogeneity of transportation carbon emissions and its influencing factors in China. China Environ. Sci. 2020, 40, 4304–4313. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, P.; Tian, B.S.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, S. Influencing factors and their spatial-temporal heterogeneity of urban transport carbon emissions in China. Energies 2024, 17, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Zhang, X.; Du, X.; Du, K. Spatiotemporal heterogeneity of the characteristics and influencing factors of energy-consumption-related carbon emissions in Jiangsu Province based on DMSP-OLS and NPP-VIIRS. Land 2023, 12, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Yu, J.; Luo, J.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Q.; Chen, Y. A GDM-GTWR-coupled model for spatiotemporal heterogeneity quantification of CO2 emissions: A case of the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration from 2000 to 2017. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Jin, K.; Duan, Z.; Gao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Gao, C. Spatial-temporal differentiation and influencing factors of carbon emission trajectory in Chinese cities: A case study of 247 prefecture-level cities. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 928, 172325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Li, S.; Ji, Q. Regional differences and driving factors analysis of carbon emission intensity from transport sector in China. Energy 2021, 234, 120178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Sang, Y.; Gui, Q.; Li, J.; Yuan, J.; Zhu, K. Research on carbon emission efficiency and spatial-temporal factors in the transportation industry: Evidence from the Yangtze river economic belt. Glob. Nest J. 2024, 26, 637–648. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Z.; Li, L.; Du, Y. Can polycentric urban morphology improve transportation carbon emission efficiency? Evidence from 285 Chinese cities, 2005–2020. Transportation 2024, 51, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, A.-X.; Liu, G.; Liu, J.; Qin, C.-Z.; Zhou, C. Spatial prediction based on the Third Law of Geography. Ann. GIS 2018, 24, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Susilo, Y.O.; Karlström, A. Estimating changes in transport CO2 emissions due to changes in weather and climate in Sweden. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2016, 47, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H. The impact of climate change on passenger vehicle fuel consumption: Evidence from U.S. panel data. Energies 2019, 12, 4460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, D.W.; Li, H.; Tate, J.E. The impact of road grade on carbon dioxide (CO2) emission of a passenger vehicle in real-world driving. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2014, 31, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, D.; Costa, Y.; Demir, E.; Florio, A.M.; Van Woensel, T. The pollution-routing problem with speed optimization and uneven topography. Comput. Oper. Res. 2024, 64, 106557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hadhrami, L.M. Comprehensive review of cooling and heating degree days characteristics over the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 27, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Wu, B.; Barry, M. Geographically and temporally weighted regression for modeling spatio-temporal variation in house prices. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2010, 24, 383–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessani, M.N.; Li, Z. SGWR: Similarity and geographically weighted regression. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2024, 38, 1232–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Shao, B.; Bian, G.; Dai, H.; Zhou, F. Analysis of influencing factors and trend forecast of CO2 emission in Chengdu-Chongqing urban agglomeration. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Sun, H.; Yuan, W.; Xia, X. The spatial pattern of the prefecture-level carbon emissions and its spatial mismatch in China with the level of economic development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Wang, M.; Yang, Y. Analysis of the influencing factors of regional carbon emissions in the Chinese transportation industry. Energies 2020, 13, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Luo, Q.; Xiao, T. Capacity modeling for mixed traffic with connected automated vehicles on minor roads at priority intersections. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2024, 47, 1794–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).