Abstract

Soil organic carbon (SOC) is a key indicator for assessing pasture degradation. This study presents an integrated, field-based approach to analyzing SOC dynamics in pastures of Rio de Janeiro state (Brazil). Unlike methods based exclusively on remote sensing or modeling, our analysis is based on 350 georeferenced soil samples collected by Embrapa Solos and complemented by historical land use data, providing robust and reliable empirical evidence. Statistical methods (ANOVA, Tukey test), geostatistical interpolation (kriging), and unsupervised clustering (k-means) were used to characterize the spatiotemporal distribution of SOC. The results revealed patterns linked to both topographic and anthropogenic drivers, enabling the objective delineation of degraded versus non-degraded pastures. SOC levels below 40 g/kg in areas under 300 m elevation were strongly associated with degradation due to intensive use. In contrast, degradation at higher altitudes was primarily linked to sloping terrain more prone to water erosion. This methodological approach demonstrates the potential of combining field data with data mining tools to detect degradation patterns and inform targeted land management. The findings reaffirm SOC as a vital indicator of soil quality and highlight the importance of sustainable pasture practices in conserving carbon stocks and mitigating climate change. The proposed threshold-based method offers a practical foundation for diagnosing degraded pastures and identifying priority areas for restoration.

1. Introduction

Grasslands are among the largest ecosystems on Earth, covering between 20% and 40% of the global land surface [1]. They span approximately 3.5 billion hectares and comprise about 70% of the world’s agricultural land [2]. In addition to supporting agriculture, pastures are essential for regulating biogeochemical cycles and store nearly 20% of global carbon stocks [3,4]. Studies suggest that carbon stocks in grasslands can be up to 50% higher than in forests [5], and often exceed those in croplands [6]. Grasslands also provide critical ecosystem services such as biodiversity conservation, climate regulation, and carbon sequestration [3,7]. These processes enhance soil fertility and play a vital role in mitigating climate change through the sequestration of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) [8]. Understanding the ability of grassland soils to store organic carbon is therefore fundamental for developing effective climate change mitigation strategies [9]. Studies, such as Delonge and Basche [10], have highlighted that grasslands are particularly significant due to their vast geographical extent, their high capacity to store carbon compared to croplands, and their crucial contribution to global climate regulation. Meyer et al. [11] highlighted that simulations using models such as the sustainable grazing systems whole-farm system model (SGS) and the RothC soil carbon model in temperate Australian grasslands show that climate variability, particularly precipitation, strongly influences soil organic carbon (SOC) dynamics, which underscores the uncertainty of soil carbon sequestration under future climate scenarios.

However, grasslands are highly susceptible to degradation, frequently resulting from unsustainable land use, poor pasture management, and land conversion [12,13]. It is estimated that roughly 50% of global pasture areas are degraded to some degree [14]. Studies conducted by Fujii et al. [15] in Indonesia showed that land-use changes over a 30-year period from primary dipterocarp forest to secondary forest, Imperata grassland, Acacia plantation, and oil palm cultivation led to substantial losses of soil organic matter. Likewise, Popin et al. [16] observed a generalized and rapid decline in soil carbon (C) stocks in the transition zone between the Amazon and the Cerrado biomes, emphasizing that land-use change is a key driver of soil degradation. A study conducted by Oliveira et al. [17] in Brazil’s main sugarcane-producing region examined the effects of the dominant land-use change sequence from native vegetation to pasture and then to sugarcane on the dynamics of carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) in the upper 1-m soil layer. These land use change transitions led to substantial, though variable, changes in soil C and N stocks across the expanding sugarcane areas in the south-central region of Brazil.

Pasture degradation is often reflected in reduced livestock productivity due to declines in plant biomass, soil compaction, and diminished microbial activity [18]. This directly compromises economic viability by decreasing the land’s carrying capacity. Degraded pastures also contribute significantly to carbon losses from both soil and vegetation, releasing large volumes of CO2 into the atmosphere [19,20]. Globally, Brazil ranks seventh in pasture area, following China, the United States, Canada, Russia, Australia, and Kazakhstan [21]. Nationally, pastures cover approximately 159 million hectares [22], of which nearly 64% showed some degree of degradation in 2022, as reported in the Digital Atlas of Brazilian Pastures [19,23,24,25]. According to Jank et al. [26], degraded pastures cause significant economic impacts. Based on data from the FAO (2006) [27], the authors estimated that, in Brazil, about 8 million hectares of degraded pastures required annual investments for renovation and/or recovery of approximately US$100–200 per hectare—an investment approaching US$1 billion per year.

In response to such challenges, the Brazilian government launched the Low Carbon Agriculture Plan (Plano ABC) in 2010, aimed at promoting sustainable agricultural practices that balance greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction with economic viability. Key strategies include pasture recovery and integrated crop-livestock-forestry (ICLF) systems to enhance carbon sequestration [28]. Among Brazilian biomes, the Atlantic Forest stands out with the highest average soil organic carbon stock—about 50 t/ha—slightly above the Amazon (≈48 t/ha) and much higher than the Caatinga (≈31 t/ha) [22]. The state of Rio de Janeiro, located within the Atlantic Forest biome, thus holds strategic importance for soil carbon conservation, as well as for native vegetation protection.

The Atlantic Forest originally covered around 130 million hectares [29], with nearly 40 million hectares converted to pastures by 2010 [30], in year 2020 11.6 million hectares of pastures in the biome were intermediately degraded, and 4.1 million were severely degraded—together accounting for nearly 39% of the total pasture area in the region [22,31]. Few studies have investigated the effects of pasture systems on SOC stocks in this biome [32,33], but findings suggest that well-managed pastures can improve SOC levels. However, most pastures in the Atlantic Forest are in various stages of degradation [34,35]. Maintaining SOC is essential for climate change mitigation, as degraded soils emit more carbon into the atmosphere. SOC plays a central role in the functioning of terrestrial ecosystems and constitutes the largest terrestrial carbon reservoir [36]. It is a key indicator of soil multifunctionality, closely linked to physical, chemical, and biological properties [37,38]. The balance between carbon inputs and losses determines whether land use trends toward sustainability or degradation [39]. Degraded pastures typically store less carbon than productive ones [40,41]. Conversely, well-managed pastures may retain or even increase SOC to levels comparable to forests [42,43]. SOC sequestration depends on pasture longevity and specific soil characteristics [44], and Resende et al. observed that soils covered by pasture on the Cachoeira farm, located in the municipality of Uberlândia, in the state of Minas Gerais, over 30 years, presented soil organic carbon (SOC) values similar to those found under native vegetation, both in the surface and subsurface layers, indicating the stability of carbon content over time.

In Brazil, few long-term studies track how pasture intensification and diversification affect soil carbon. Zago et al. [45] highlight gaps in knowledge about microbial and biochemical processes regulating carbon and gas fluxes. Azevedo et al. [46] found that degraded pastures acted as GHG sources (4.00 Mg CO2eq ha−1 yr−1), while diversified systems acted as sinks (5.51–6.24 Mg CO2eq ha−1 yr−1). Yet uncertainty remains due to limited long-term data. De Azevedo et al. notably compiled a 46-year dataset on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in Brazil (1970–2015), encompassing over 2 million records in the agriculture, energy, industry, waste, and land use change sectors at the national level. GHG estimates were calculated based on emission sources for each sector and their respective gases, following the methodologies described in the IPCC Guidelines.

The large extent of degraded pastures in Brazil makes it urgent to adopt effective restoration strategies and improve soil management to prevent or mitigate negative environmental impacts [25]. Unlike studies based on models or remote sensing, the present study uses actual field data collected by Embrapa Solos, a unit of the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (Embrapa), which focuses on generating knowledge and technologies for Brazilian agriculture. SOC is widely accepted as a key soil quality indicator [47] and plays a pivotal role in soil processes [48]. Assessing SOC is crucial to evaluate the effects of land use and management on soil quality [49]. It analyzes 350 soil samples collected from across the state of Rio de Janeiro between 1984 and 1998, offering a robust assessment of SOC variability in pasturelands. Analyses were performed on the samples included physical, chemical, morphological, and mineralogical properties, and were conducted at the Embrapa laboratories.

Strong environmental legislation is vital to promoting sustainable resource management and effective environmental governance. In Brazil, federal environmental policies have advanced progressively over the last five decades, reflecting continuous improvements in legal instruments and environmental monitoring systems [50]. Starting in the 1980s, Brazil began to adopt a more preventive approach to environmental protection [51]. An important milestone in this process was the creation of the National Environmental System in December 1981, established to conduct studies and propose government policies for the sustainable use and preservation of natural resources [52]. This period is considered a key moment in environmental law, marking the start of a behavioral and institutional shift towards proactive environmental governance [53]. In contrast, 1998 coincided with a new phase of economic liberalization and agricultural expansion, which intensified land use conversion pressures on forest and pasture systems [34]. The period chosen for the present study therefore represents a transition between early environmental governance and modern agro-industrial development. Together, these temporal benchmarks provide a valuable framework for interpreting the historical and ongoing dynamics of pasture degradation in the Atlantic Forest biome.

Based on this dataset, the study tests the hypothesis that distinct degradation levels can be identified via clustering based on SOC and topographic data. The objectives are to: (1) evaluate land use changes between 1985 and 1998, (2) characterize the spatial distribution of SOC and identify controlling factors, and (3) establish SOC thresholds for identifying degraded pasture zones. These insights aim to support sustainable land management strategies and highlight the Atlantic Forest’s role in carbon conservation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The state of Rio de Janeiro is in the southeastern region of Brazil, between approximately 20°45′ and 23°15′ south latitude and 40°55′ and 44°45′ west longitude. Covering an area of about 43,797.5 km2 (Figure 1a), the state lies within the Atlantic Forest biome. It borders Minas Gerais to the north and northwest, Espírito Santo to the northeast, São Paulo to the southwest, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east and south. Major natural features include the Paraíba do Sul, Paraibuna, Preto, and Itabapoana rivers, as well as the Mantiqueira and Bocaina mountain ranges. According to the 2022 Demographic Census by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics [54], Rio de Janeiro has the highest population density in Brazil, with approximately 367 inhabitants per km2.

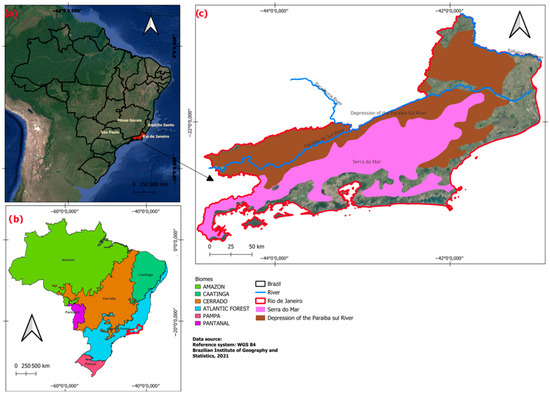

Figure 1.

Geographic location of the state of Rio de Janeiro (a), with representation of the biomes (b) and main physiographic features of the state territory (c).

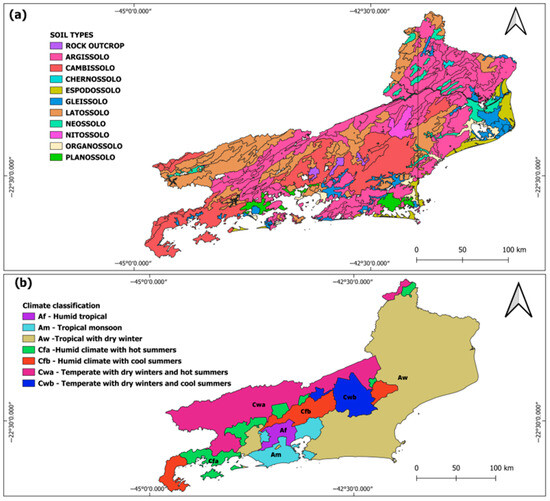

The state’s geodiversity supports a wide variety of soils. In well-drained areas, dominant soil types include Argissolos, Cambissolos, Neossolos, Chernossolos, and Nitossolos, commonly associated with higher elevations. In low-lying humid regions like valleys and coastal plains, Gleissolos, Espodossolos, Planossolos, and Organossolos prevail (Figure A1a, see Appendix A). Latossolos occur in high-altitude areas, and Quartzarenic Neossolos in coastal regions.

The climate in Rio de Janeiro is highly variable due to its rugged topography, which includes hills, mountains, valleys, lowlands, and bays, as well as the influence of the Atlantic Ocean. The state includes several climate types [55], as classified in Figure A1b (see Appendix A): Aw (tropical with dry season), Am (monsoon), Af (humid equatorial), Cfa (subtropical with hot summers), Cfb (subtropical with mild summers), and Cwa/Cwb (with dry winters and hot/mild summers). The Aw climate predominates along the coastal strip, the north-northwest, and the Paraíba do Sul Riverbanks. The Am climate occurs near mountainous regions and the lower slopes of the state capital due to orographic rainfall. In the lower areas of Serra do Mar, the Af climate dominates, with annual precipitation near 2500 mm. On high escarpments, altitude reduces the average annual temperature to ~20 °C, typical of the Cfa climate. In the highest zones, the temperature drops further to around 18 °C, corresponding to Cfb climate. Cwa and Cwb types are found in regions with less orographic influence, where precipitation is summer-concentrated, averaging 1500 mm annually.

As part of the Atlantic Forest biome, Rio de Janeiro is additionally home to one of the world’s most biodiverse and endangered forest formations [56]. Originally covering the entire state, the biome has suffered extensive fragmentation and degradation due to urban, industrial, and agricultural expansion. Today, remnants are mostly secondary and fragmented formations, often located in rugged or protected zones (Figure 1b). Conversion of forests to pastures throughout the 20th century drastically reshaped the rural landscape, with pastures and agricultural mosaics now predominant across much of the state.

2.2. Activity Flow

The methodological approach adopted in this study (Figure 2) was structured into three main stages, each integrating sequential and interdependent procedures designed to ensure data quality and analytical consistency.

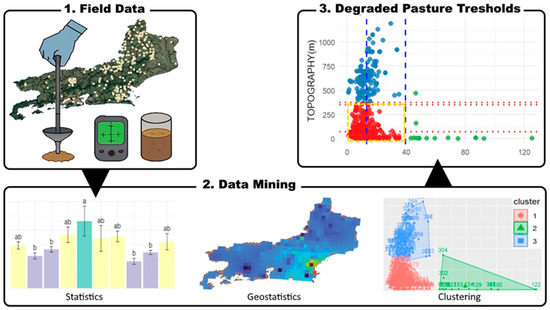

Figure 2.

Methodological workflow for identifying patterns of pasture degradation in the state of Rio de Janeiro.

Stage 1—Compilation and validation of actual field data (soil sampling points).

This stage involved the collection and quality control of SOC data from 350 georeferenced sampling points across the state of Rio de Janeiro, covering 52 of the state’s 92 municipalities, to evaluate SOC distribution over time and space. The primary data source was Embrapa Solos, accessed through the Brazilian Soil Information System (SiBCS) [57]. The Brazilian Soil Classification System (SiBCS) is the official taxonomic system for soils in Brazil. Developed since the 1970s, it is a hierarchical, multi-categorical, and flexible system designed to classify all soils in the national territory. It is obtained from the evaluation of morphological, physical, chemical, and mineralogical data of the profile that represents it. The classification of a soil begins with the morphological description of the profile and the collection of field material, which must be conducted according to criteria established in Embrapa Solos manuals, observing the utmost care, patience, and discernment in the description of the profile and the landscape it occupies in the ecosystem. For this study, the SiBCS soil classes were linked to land use and land cover data from the MapBiomas database, allowing each soil sampling point to be associated with the corresponding land use and land cover class from MapBiomas. MapBiomas is a global and multi-institutional network composed of universities, NGOs, and technology companies that monitors land cover and land use changes across territories and their environmental impacts. It is important to note that MapBiomas data provide a comprehensive overview of the percentage variation among different land use classes over time in the study area.

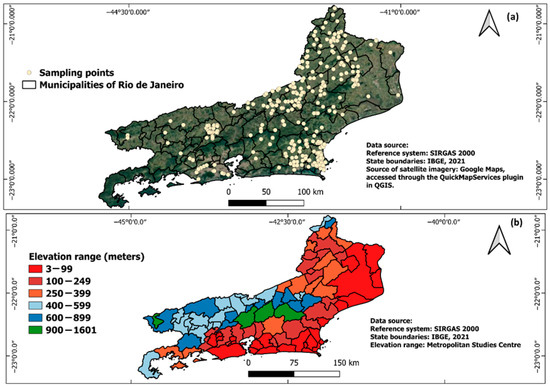

Sampling occurred between 1984 and 1998, a period characterized by significant land-use transformations. The landscapes of the Atlantic Forest in southeastern Brazil have undergone extensive historical deforestation and degradation [58]. One important characteristic of Brazilian livestock farming is that most of its herd is raised on pasture [59]. Data from the IBGE report (2007) [60] showed that there was an evolution in pasture stocking rates in the major regions and in Brazil between 1975 and 2006, due to unsustainable management, most of these pastures are currently very degraded [58] and Figure 3 shows the geographic distribution and elevation classes of each sampling point. Each point included georeferencing, land-use classification, elevation and SOC content (g/kg) at various depths. For consistency, we used data from the 0–40 cm layer in pasture areas, since this topsoil typically reflects the most significant organic carbon variation due to management practices [61]. Strict filtering was applied to exclude points with missing, inconsistent, or erroneous values. Values were considered erroneous when they exhibited spatial discrepancies or were located outside the boundaries of the state of Rio de Janeiro. Geographic coordinates were verified and corrected using Google Earth and missing or incorrect coordinates were manually verified. When the coordinates system was unspecified, WGS 84 was assumed. To ensure consistency, spatial reference systems, municipality names, and federal codes were standardized according to official IBGE standards. Soil samples were collected following Embrapa’s standardized procedures, which involve dividing the study areas into plots of up to 10 hectares, ensuring uniformity in color, topography and texture. Each selected plot was traversed in a zigzag pattern, and soil samples were taken from 15 to 20 different points using an auger (or alternatively a tube or shovel). The composite samples were placed in clean containers for homogenization. Sampling was avoided near houses, sheds, or roads, as well as under waterlogged soil conditions.

Figure 3.

Maps showing: (a) a distribution of the 350 soil sampling points and (b) altitude range of the municipalities, classified into six categories.

SOC content was determined in Embrapa Solos laboratories using the Walkley-Black method [62]: organic matter was oxidized with 0.4 N potassium dichromate in sulfuric acid, then titrated with 0.1 N ferrous sulfate. SOC levels were interpolated using ordinary kriging at a 20 × 20 m resolution, following confirmation of spatial autocorrelation using Moran’s I Index. The result was a continuous map of average SOC across the state from 1984 to 1998.

Stage 2—Data integration and statistical-geospatial analysis.

Field data were combined with environmental variables, including land use/cover (MapBiomas), edaphoclimatic factors (from IBGE and Embrapa), and findings from previous studies on pasture degradation [62,63,64,65]. An initial exploratory analysis compared SOC values across land use classes (pasture, forest, agriculture), using boxplots to illustrate distribution patterns. This revealed a general trend of lower SOC in pasture areas compared to forests, though soil and climate factors also significantly influenced results. Previous studies, such as Müller et al. [66] have highlighted the relationship between pasture degradation, soil properties, and the conversion of forests to pastures in the Brazilian Amazon. It is also important to note that land uses such as forests and agricultural–pasture mosaics have frequently been converted to pasture areas, contributing to the expansion of grazing lands across Brazil.

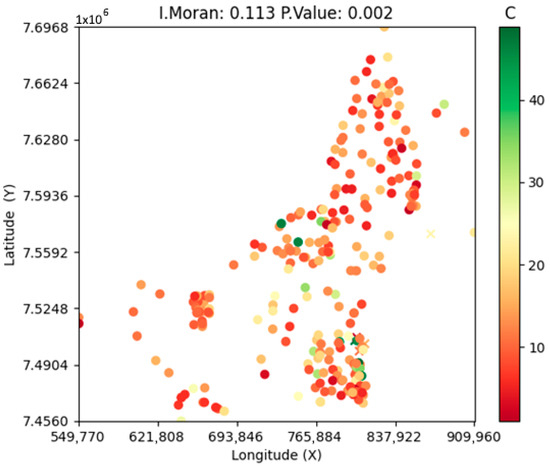

Descriptive and inferential statistical analyses were conducted, including the Shapiro–Wilk test to assess data normality. When the data did not meet the assumption of normality, a logarithmic transformation (LNX + 1.5) was applied. Subsequently, a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (p < 0.05) was performed to evaluate the to compare SOC levels between years (Figure 4). Spatial autocorrelation (Moran’s I) was examined to validate the applicability of ordinary kriging for SOC interpolation. Values range from –1 (dispersion) to +1 (aggregation), with 0 indicating randomness. In our study, Moran’s I = 0.113 and p < 0.05, indicating weak but significant clustering. This justified the use of geostatistical interpolation. All analyses were performed using RStudio version 2025.05.0 [67].

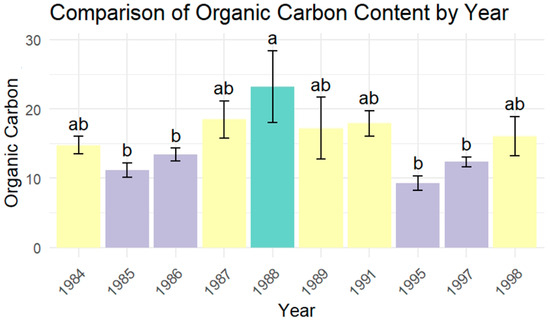

Figure 4.

Annual variation in soil organic carbon (SOC) content from 1984 to 1998 in pasture areas of the state of Rio de Janeiro. Bars represent mean SOC values (± standard error) obtained from soil samples. Different letters (a, b, ab) indicate statistically significant differences among years according to Tukey’s post-hoc test following one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05).

Stage 3—Identifying degraded pasture thresholds.

This final stage aimed to define objective criteria to differentiate degraded from non-degraded pastures based on SOC and environmental variables. The analysis focused on detecting thresholds in SOC content related to topographic features using K-means clustering as the multivariate analysis technique. This method classified samples into homogeneous groups based on similarities in SOC and elevation. Several k values ranging from 1 to 10 were tested by Silhouette method (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Results of the Silhouette method for selecting the optimal number of clusters (k). The peak silhouette score at k = 3, marked by the dotted line, indicates that the dataset is best divided into three clusters.

The Silhouette method indicated that three clusters (k = 3) represented the most cohesive and statistically robust grouping, each characterized by specific combinations of SOC values and elevation. Elevation was selected as the clustering variable instead of land use because all samples were collected exclusively from pasture areas, with no variation in land use that could justify its inclusion as an explanatory variable. Precipitation, on the other hand, was not included in the clustering analysis between soil organic carbon and topographic parameters due to the strong orographic effect in the state of Rio de Janeiro. This condition causes high spatial variability of rainfall over short distances, resulting in highly heterogeneous local patterns that are not representative at a regional scale of analysis. Although slope is recognized as an important topographic factor influencing soil erosion, drainage, and the accumulation of organic matter, it was not included in the present clustering analysis. However, its relevance for understanding the redistribution of soil organic carbon across the pasture is acknowledged, and future studies should incorporate slope to better capture the combined effects of topography on soil carbon variability. This cluster analysis enabled the detection of transition zones suggestive of degradation, supporting the definition of diagnostic criteria for pasture condition.

2.3. Land Use Mapping Data

The analysis of land use and land cover (LULC) changes in Rio de Janeiro relied on two main datasets:

The first dataset provided spatial characterization, including land use, administrative boundaries, soil types, biomes, climate, and elevation. These layers, from [65], were available at 1:250,000 scales and were processed in QGIS for integration. Data sources are detailed in Table A1 (See Appendix A).

The second dataset documented LULC dynamics between 1985 and 1998 (Figure A2, see Appendix A), with 1985 marking the onset of key environmental policies, and 1998 aligning with a new phase in Brazil’s economic development. This dataset was drawn from MapBiomas Collection 9, which uses Landsat images (TM, ETM+, OLI) from satellites 5, 7, and 8, offering a 30-m spatial resolution. The land use classification followed MapBiomas criteria (Table A2). This information supports the contextual understanding of how historical changes in land use have influenced SOC.

From these data, we calculated the area (in hectares) occupied by each LULC class for each reference year, quantifying temporal trends and transitions. The analysis emphasized pasture dynamics relative to forests and mosaics, given their relevance to SOC variation.

3. Results

3.1. Evolution of Land Use (1985–1998)

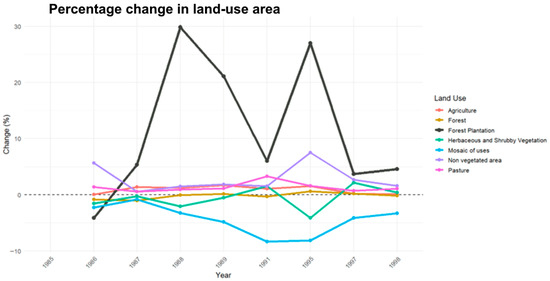

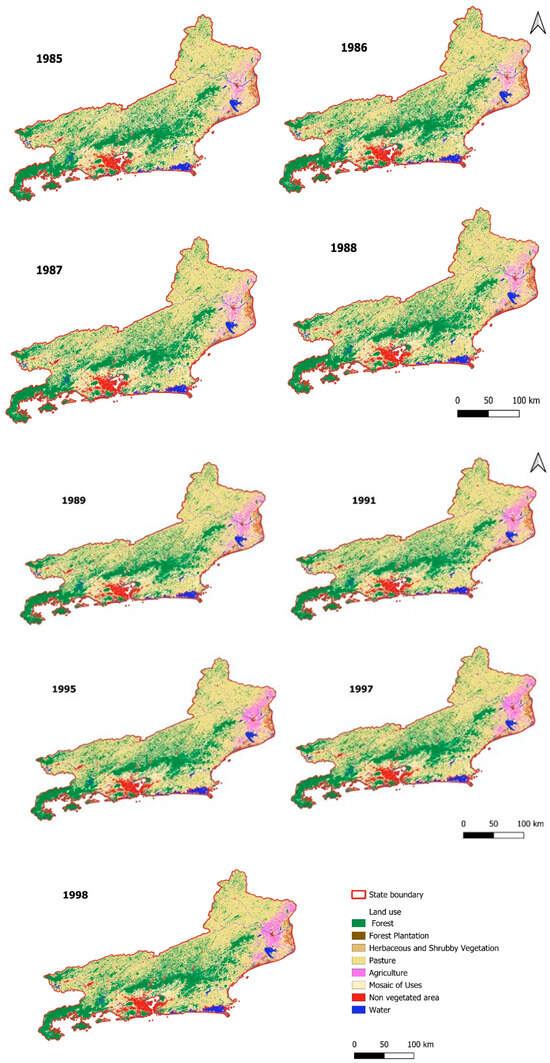

The evolution of land use and land cover (LULC) in the state of Rio de Janeiro from 1985 to 1998 is illustrated in Figure A2 (see Appendix A), considering nine reference years: 1985, 1986, 1987, 1988, 1989, 1991, 1995, 1997, and 1998. The results reveal significant transformations in land occupation over this period (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Annual percentage change in land use and land cover classes in Rio de Janeiro (1985–1998). Positive values indicate area expansion; Negative values represent reductions.

The forestry class showed a cumulative increase of 484,071 hectares, representing a +120% growth between 1985 and 1998. This category includes both forest plantations and native forests under managed or commercial use (e.g., logging), and its expansion suggests localized reforestation initiatives and the spread of intensive forestry systems in specific regions. Agricultural areas increased by 221,095 hectares (+107%), encompassing croplands and other cultivated lands. Pasture areas, treated as a distinct subcategory due to their importance for SOC dynamics, expanded by 194,478 hectares (+111%), largely replacing agricultural mosaics, forest formations, and herbaceous vegetation. Non-vegetated areas (urbanized zones, exposed soils, and other surfaces without vegetation) grew by 81,023 hectares (+124%), reflecting urban expansion and infrastructure development.

Conversely, several natural vegetation categories showed marked declines: native forest formations decreased by 35,418 hectares (–3%), herbaceous and shrub vegetation declined by 8714 hectares (–5%), and agricultural mosaics showed the most substantial reduction at 292,016 hectares (–30%). This pattern indicates a simplification of land use structures, where previously mixed-use areas were converted into more homogeneous classes, particularly pastures and urban areas. Overall, the analysis (Table A3, see Appendix A) indicates a shift in the rural landscape, with pastures and mosaics increasingly displacing forests. By 1998, the combined area of pastures and mosaics approached the total forest area, underscoring the growing dominance of pasture-based land use across Rio de Janeiro.

3.2. Characterization, Spatial and Temporal Distribution of SOC

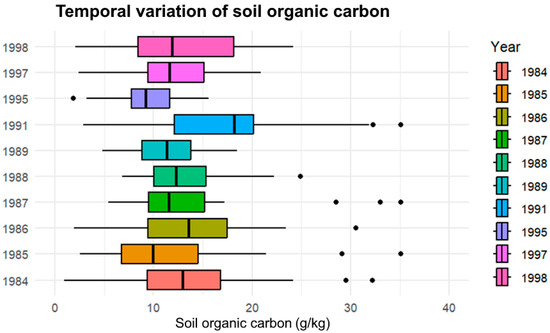

Figure 7 presents the SOC boxplots by year. The highest median occurred in 1995 (27.1 g/kg) and the lowest in 1991 (22.3 g/kg). The Shapiro-Wilk test indicated non-normality (p < 0.05), requiring log transformation for parametric analysis. One-way ANOVA detected significant differences (p < 0.05) between years, and Tukey’s test revealed that 1991 had significantly lower SOC than 1995 and 1997 (Figure 4). These results confirm statistically significant differences in the annual variation of SOC, indicating continuous changes in soil quality and carbon content over the study period. Similar findings have been reported by Santos et al. [68], who emphasized that low SOC levels compromise soil quality.

Figure 7.

Temporal variation in soil organic carbon (SOC) content between 1984 and 1998 in pasture areas of the state of Rio de Janeiro. Each box plot represents the distribution, median, and variability of SOC values (g /kg) for each sampling year.

Descriptive statistics for SOC across the analyzed years (Table A4, see Appendix A) reveal substantial variability both temporally and spatially. The temporal dynamics (Figure 7) indicate 1988 as the year with the highest mean SOC values, while 1995 recorded the lowest levels. The year 1988 presented statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) compared to the other years (Figure 4).

Intermediate SOC values were recorded in the years 1984, 1987, 1989, 1991, and 1997 (Figure 4), with no statistically significant differences among them. This grouping may reflect periods of partial recovery or relative stabilization of pastures areas. Conversely, the years 1985, 1986, 1995, and 1997 constituted the group with the lowest average SOC values (Figure 4). This pattern coincides with the expansion of non-vegetated areas (Figure 4), processes that reduce organic matter inputs to the soil due to the reduction of vegetation [69].

In addition, the years 1984, 1985, 1987, and 1998 exhibited greater data dispersion, with maximum SOC values exceeding 50%, indicating high variability in soil conditions during these periods. The year 1991 was notable for its high median and wide interquartile range, indicating significant heterogeneity among samples. Conversely, 1995 recorded the lowest mean and median values, signaling clear soil depletion and pasture degradation. These results are aligned with the observations of [70] who reported that degraded pasture soils exhibit lower SOC levels than those under agricultural cultivation or secondary vegetation. Following 1997, SOC values showed a slight recovery accompanied by an increase in dispersion, potentially associated with the implementation of restoration practices (e.g., Plano ABC), such as the introduction of planted forests or the adoption of integrated grazing and silviculture systems (Table A4, see Appendix A). However, evidence of heterogeneity remained high, indicating uneven adoption of sustainable practices. Studies by [44,71] have demonstrated that the integration of planted forests with pastures can enhance soil carbon accumulation and contribute to climate change mitigation. However, SOC levels did not reach the values observed between 1984 and 1986, indicating that recovery was only partial.

The continuous decline in SOC between 1984 and 1995 coincides with the expansion of pasture areas (Figure 6). This pattern is consistent with Pereira et al. [72] who reported that forests-to-pasture conversion can result in 20–30% losses of soil organic carbon.

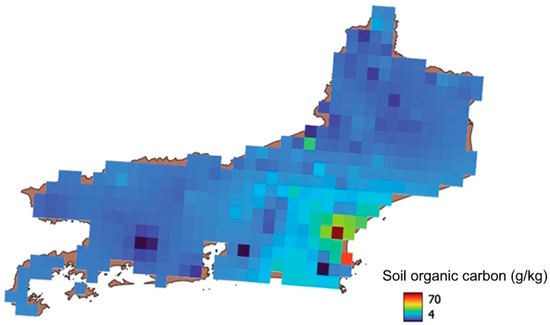

SOC spatial patterns were analyzed using kriging interpolation, which revealed clear regional trends (Figure 8). The calculated Moran’s index was 0.113 (p-value = 0.002; Figure A3, see Appendix A), indicating the presence of positive spatial autocorrelation, although weak but statistically significant. This suggests that SOC values tend to cluster in Specific regions, demonstrating partial spatial continuity. The 350 pasture samples collected in the state of Rio de Janeiro exhibited SOC values ranging from 4 to 70 g/kg in the 0–40 cm soil layer (Figure 8). The average SOC content was 26.9 g/kg, with a standard deviation of 11.9 g/kg. The median was 24.5 g/kg, and the interquartile range (IQR) was 17.2 to 34.7 g/kg, indicating a moderate level of variability among sampled areas. Higher SOC values were concentrated in coastal lowlands, estuarine zones, and some mountainous regions, particularly in the northeast, central-south, and coastal west. These high concentrations are associated with conditions favorable to the accumulation of organic matter, such as greater moisture availability, lower decomposition rates, and higher vegetation productivity. Lower SOC was typical in central and north-central regions, coinciding with intensively used pastures and low organic matter soils. These areas correspond to partially or highly degraded pastures, as identified in the Digital Atlas of Brazilian Pastures in 2020. By highlighting zones with low SOC values, these results can assist practitioners in designing targeted intervention strategies for the recovery and restoration of degraded pastures.

Figure 8.

Spatial distribution of soil organic carbon in the state of Rio de Janeiro. Values range from 4 to 70 g/kg, indicating areas with higher SOC stocks (in reddish tones) and regions with lower values (in bluish tones).

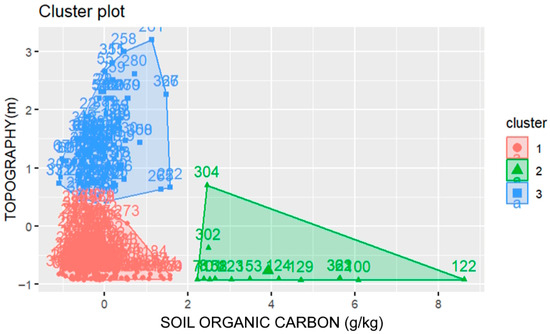

3.3. SOC Thresholds and Clustering

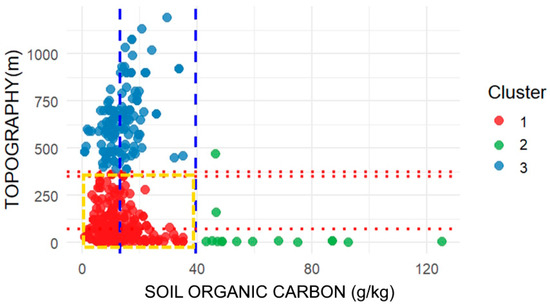

The three clusters, illustrated in Figure 9, were distinguished based on the combined influence of topography and SOC content. The distinct separation among clusters indicates that the joint analysis of these variables effectively captures the relationship between elevation and soil carbon organic across the state. The variations in SOC are spatially structured by topographic gradients, allowing the identification of areas with contrasting soil degradation conditions. The three clusters were defined as follows:

Figure 9.

Results of the three clusters obtained by the K-means method, based on SOC and topography. The relationship between the Between-Cluster Sum of Squares (BSS) and the Total Sum of Squares (TSS) shows that the grouping explains 71.7% of the variance.

The three clusters were separated as follows:

- Cluster 1 (red): This group primarily includes points located in areas with low to moderate elevation, characterized by low to moderate SOC values.

- Cluster 2 (green): This cluster groups points located in very low elevation and corresponds to the highest SOC values recorded in the dataset. The high SOC values in this cluster coincide with the areas of highest carbon accumulation identified in the spatial analysis of SOC distribution (Figure 8).

- Cluster 3 (blue): This cluster comprises samples from areas of higher elevation, where SOC values range from low to moderate.

4. Discussion

4.1. Land Transformation and Dynamics of SOC

Between 1984 and 1998, the state of Rio de Janeiro experienced significant changes in land use, driven by socioeconomic and political transformations. This period therefore represents a transition in the dynamics of land use in the region, which we believe has direct implications for soil organic carbon content. Understanding these transformations provides an essential context for interpreting the spatial and temporal distribution of soil organic carbon. The data confirm that pasture expansion during this period primarily occurred through the conversion of mosaics and forest remnants. This trend aligns with national patterns of agricultural intensification during the same timeframe [22]. Although much of the Atlantic Forest had already been cleared before 1985, the data indicate additional deforestation until 1991. Subsequent forest gains suggest partial recovery, but these increases were insufficient to offset decades of cumulative loss.

To better understand the temporal dynamics of SOC in pastures of Rio de Janeiro, we analyzed SOC values across multiple years. This approach allows for the assessment of interannual variability in SOC and its association with pasture expansion and management practices. Evaluating SOC trends over time provides insight into periods of pronounced loss or recovery that may inform sustainable management strategies. Within the Atlantic Forest biome, studies such as Vicente et al. [33] conducted in one of the historically most deforested regions of Minas Gerais in the municipality of Muriaé (where large areas of native forest have been converted to agricultural use), demonstrate that pasture degradation, such as reduced pasture productivity and soil compaction, has a marked negative impact on SOC accumulation. In that study, soil samples were collected from experimental sites located on the Santa Helena and Mundial farms, in the state of Minas Gerais, comprising 3- and 5-year-old eucalyptus, plantations, a 35-year-old rubber tree plantation, and a 50-year-old pasture dominated by Brachiaria decumbens. However, when pastures are properly managed for instance, through controlled stocking rates to prevent overgrazing and by diversifying forage species, they can act as significant carbon sinks, enhancing SOC sequestration and promoting the long-term storage of carbon in soils.

Descriptive statistics (Table A4) allowed the identification of periods of SOC depletion or accumulation, highlighting the influence of different management practices and vegetation cover. This result may be associated with a greater availability of plant residues in the surface layer of the soil, as suggested by Conceição et al. [73]. In addition, this period coincides with a marked expansion of planted forests (Figure 6), indicating a possible positive influence of this land use on the accumulation of soil organic matter.

Between 1984 and 1985, a decline in SOC levels was observed, followed by a general upward trend in the subsequent years relative to 1984. These variations are linked to land use and land cover changes, as emphasized by Trumbore and Camargo [74]. This interpretation is consistent with the findings of Freitas et al. [75] who demonstrated the direct impact of land use transformations on soil organic carbon content. Furthermore, our results provide valuable information for the development of strategies aimed at restoring and conserving environmental quality, as well as mitigating climate change in areas undergoing land use and land cover changes.

4.2. Spatial Variability of Soil Organic Carbon

The kriging approach provided a robust estimate of the spatial distribution of COS across the study area, even when sampling points varied between years. A similar approach was employed by Ross et al. [76] in the northeast and east-central regions of Florida, where geostatistical interpolation models were developed using historical SOC data (1965–1996) to assess the spatial variability of soil carbon stocks over time. Their findings demonstrated that geostatistical interpolation can effectively represent spatial trends and long-term changes in SOC, even when sampling locations vary between survey years. These results support the methodological validity of our interpolation-based analysis for assessing SOC dynamics in Rio de Janeiro. Understanding the spatial distribution of soil organic carbon (SOC) is crucial for identifying areas with low and high SOC values and guiding targeted management interventions. Kriging interpolation provided a detailed representation of SOC variability in the state of Rio de Janeiro. Higher SOC values can be attributed to the presence of mangrove areas along the coast, which are known for their exceptional carbon sequestration and storage capacity—up to three to five times higher than in other vegetated ecosystems [77]. Conversely, areas with lower SOC values corresponded to locations with a high prevalence of non-vegetated areas, as illustrated in Figure A2 (see Appendix A).

Three spatial patterns emerged:

High SOC zones: were in floodplains and mangrove areas, suggesting natural accumulation in hydromorphic soils. These values were unrelated to pasture degradation.

Intermediate SOC zones: appeared in forested slopes and mosaic landscapes, reflecting less intensive land use or transitional recovery stages. This grouping reflects partial recovery or relative stability in carbon dynamics.

Low SOC zones: were widely distributed in central and northern zones, often on gently rolling or flat terrain, suggesting degradation from prolonged livestock grazing and low input use.

4.3. SOC Thresholds and Pasture Degradation

The overlap of cluster cut-off lines in the sample space enabled a clear stratification of the different combinations of SOC and elevation, facilitating the identification of thresholds for areas with different soil degradation potentials (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Identification of potential areas of pasture degradation based on the clusters of soil organic carbon and topography. Represented by cluster 1 (red), cluster 2 (green) and cluster 3 (blue). The different lines were used to delimit the transition zones between the clusters.

The clusters were interpreted as follows:

Cluster 1 (SOC < 40 g/kg, elevation < 300 m):

Represents degraded and partially degraded pasture areas, consisting of low to moderate altitude (up to 300 m) with SOC values below 40 g/kg, which marks the onset of pasture degradation. Furthermore, we consider that from the threshold of 15 g/kg onwards, pastures can be classified as severely degraded. This delimitation, based on cluster analysis, reflects areas under high anthropogenic pressure from intensive agricultural activities or inadequate livestock management.

According to the mapping carried out by the Brazilian Digital Pasture Atlas, approximately 64 million hectares of pastures in Brazil are under moderate or severe degradation. This widespread degradation poses significant environmental risks, particularly for soil health, as it promotes erosion and the loss of fertility. Seliger et al. [78] showed that all pastures on slopes in the northwest of Rio de Janeiro state exhibit multiple levels of degradation, evidenced by various erosive forms such as rills, cattle trails, and gullies.

A study by Maia et al. [79] in the Brazilian states of Rondônia and Mato Grosso showed that poorly managed pastures experienced a reduction in SOC of approximately 0.27–0.28 Mg C ha−1 yr−1. Conversely, well-managed or improved pastures in these regions demonstrated potential for carbon sequestration. Cerri et al. [80] investigated the effects of the mainland-use change—conversion of tropical forest to pasture—on soil carbon (C) in the Brazilian Amazon. They analyzed pastures established in 1911, 1951, 1972, 1979, 1983, 1987, and 1989, and found that the conversion to pasture led to an initial decline in soil carbon stocks.

Under these conditions, practices such as excessive soil disturbance, overgrazing, and mechanical compaction accelerate the loss of organic matter and structural degradation of the soil, compromising its carbon storage capacity. This cluster covered the largest number of sampling points and was most prevalent in the central-north region. A study by Daniele Costa Oliveira et al. [81], which analyzed 169 paired comparisons across different pasture types in 14 Brazilian states over a 30-year period, showed that degraded pastures experienced SOC losses of 6%, 10%, and 13% at soil depths of 30, 50, and 100 cm, respectively. In contrast, restored pastures showed SOC gains of 15%, 20%, and 23% for the same depths and period. The pastures in Cluster 1 thus require targeted recovery interventions to enhance soil fertility and carbon sequestration, contributing to climate change mitigation and supporting the goals of the ABC Plan, launched by the Brazilian government in 2012.

Cluster 2 (SOC > 40 g/kg, elevation < 300 m):

Characterized by high SOC levels in very low topographies, it represents areas of low degradation and is associated with mangrove zones and humid highlands. Mangrove areas are known to store relatively high amounts of carbon [82,83], which corroborates our findings. Understanding carbon fluxes in these habitats is crucial for climate change mitigation. Despite significant challenges such as land-use change, sea-level rise, and climate variability, mangroves continue to function effectively as carbon sinks [84]. However, we highlight that even areas with high SOC can become susceptible to degradation due to inadequate management, particularly through overgrazing.

High SOC values are more likely due to natural environmental conditions (e.g., hydromorphic soils, dense root systems). In these environments, anoxic conditions and the constant organic matter deposition favor the accumulation and conservation of large amounts of carbon [85].

Cluster 3 (SOC < 40 g/kg, elevation >300):

This cluster includes pastures located in higher altitude areas with low SOC content. Pastures at high altitudes play an important role in controlling SOC dynamics but are highly susceptible to erosion [86]. Our results are consistent with findings by Jordi et al. [87] in subalpine and alpine pastures along the Pyrenees in Spain, where SOC values were low at higher elevations and higher at lower elevations.

The lower carbon content observed in this group may be associated with steeper slopes, which are more susceptible to erosion and other factors that limit the accumulation of organic matter in the soil. However, some studies, such as Meng Zhu et al. [88] in the Dayekou watershed within the Qilian Mountains National Nature Reserve in Gansu, northwest China, have reported high SOC values at higher elevations, indicating that local conditions can strongly influence SOC distribution.

This clustering analysis proved to be an effective tool for understanding SOC distribution patterns as a function of topography and anthropogenic use. The elevation variable proved to be a key factor in differentiating degradation drivers. In lowland areas, degradation was primarily linked to overgrazing and soil compaction, while in upland areas, degradation correlated more with topographic constraints, especially erosion on slopes.

From this analysis, a critical threshold of 40 g/kg SOC was proposed to distinguish non-degraded or resilient areas. Values below this threshold, especially under 300 m elevation, are indicative of potential degradation and should be prioritized for monitoring and recovery.

This classification supports the development of SOC-based diagnostic tools for pasture condition, which are both empirically grounded and adaptable to similar contexts. The cluster analysis effectively revealed degradation patterns, offering technical insights for defining restoration targets and sustainable land use policies.

Considering future scenarios, the intensification of climatic extremes such as prolonged droughts and intense rainfall may further accelerate SOC depletion and exacerbate erosion in poorly managed pastures. Therefore, integrating SOC monitoring into public policies for land use planning and rural development becomes essential.

5. Conclusions

This study conducted a comprehensive assessment of SOC dynamics in pasture areas of the state of Rio de Janeiro, analyzing spatial patterns and temporal variation between 1984 and 1998, and evaluating the influence of topographic features and land use practices. A key strength of this research lies in its use of empirical field data (350 soil samples collected by reference institutions such as Embrapa Solos) setting it apart from studies based solely on remote sensing or indirect estimates. This robust dataset enhanced the reliability of the analyses and strengthened the validity of the findings.

By applying geostatistical methods and k-means clustering, the study identified well-defined spatial patterns of SOC distribution, emphasizing the decisive role of topography and land use intensity. Areas on steep slopes exhibited lower SOC levels, due to increased susceptibility to erosion and reduced organic matter accumulation. In contrast, humid environments and flatter terrains demonstrated greater carbon sequestration potential, underscoring the interplay between physical landscape features and soil carbon dynamics.

A central finding was the identification of degraded and partially degraded pasture zones, characterized by SOC levels below 40 g/kg and elevations below 300 m. These areas exhibit a clear interface between anthropogenic pressures (such as intensive grazing) and natural constraints like terrain and altitude. The use of data-driven thresholds derived from cluster analysis proved effective for classifying soil conditions and supporting evidence-based management interventions.

The delineation of critical areas for both degradation risk and carbon retention highlights the strategic importance of sustainable pasture management for climate mitigation and the preservation of ecosystem services. Despite relying on historical data and facing limitations due to the absence of more recent georeferenced samples, the study’s results align with current scientific understanding and demonstrate the utility of SOC and topographic variables in diagnosing degradation trends. Good pasture management practices such as rotational grazing, soil cover maintenance and controlled livestock density are essential for preserving SOC and preventing pasture degradation.

Future research should aim to integrate additional variables, including current land use, management intensity, slope, and climatic influences, to enable more comprehensive and predictive models. The findings also underscore the need for continuous, spatially explicit SOC monitoring and the advancement of analytical methods that reflect the ecological complexity of tropical agroecosystems.

Overall, this study reinforces the vital role of well-managed pastures in maintaining soil carbon stocks and calls for urgent investment in public policies and land use strategies grounded in scientific evidence. Such measures are essential not only to preserve SOC levels but also to support soil fertility, physical integrity, and the long-term resilience of agricultural landscapes in the face of global environmental change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, writing-original draft, data curations, investigation: F.A.B.J. and J.P.M.; Writing—review & editing, validation, supervision, formal analysis: F.A.L.P. and L.F.S.F.; Validation, Formal analysis: A.M.d.C., C.A.V. and M.d.L.M.-S.; Project administration, funding acquisition: J.P.M. and M.d.L.M.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings reported in this study are fully presented within the article. Any additional or supplementary datasets can be made available by the first author.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the project INCT Soils of Brazil: innovation as a key to sustainable use, CNPQ process 408724/2024-2, sector COPPM/CGNAC/DCOI. For the author affiliated with CITAB, this work was further supported by National Funds of FCT–Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, under the project UIDB/04033/2025 (DOI:10.54499/UIDB/04033/2025). This author is also affiliated with Inov4Agro–Institute for Innovation, Capacity Building and Sustainability of Agri-food Production, funded under the project LA/P/0126/2020 (DOI:10.54499/LA/P/0126/2025). Inov4Agro is an Associate Laboratory composed of two R&D units (CITAB & Green U Porto). For the author integrated in the CQVR, the research was supported by National Funds of FCT—Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, under the projects UIDB/00616/2025 (DOI:10.54499/UIDB/00616/2025) and UIDP/00616/2025 (DOI:10.54499/UIDP/00616/2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SOC | Soil organic carbon |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| ICLF | Integrated crop-livestock-forestry |

| IBGE | Brazilian institute of geography and statistic |

| LULC | Land use and cover |

| SIBCs | Brazilian Soil Information System |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

The figure represents the environmental context of the State of Rio de Janeiro, showing the distribution of soil types according to the Brazilian Soil Classification System (a) and the Köppen climate classification, showing the distribution of the main climate types in the state (b).

Figure A2.

Evolution of land use and land cover (LULC) between 1985 and 1998 for different land use classes in the state of Rio de Janeiro.

Figure A3.

The result of the Morgan index correlation shows the spatial distribution of soil organic carbon. The Morgan index (I. Morgan = 0.113) and p-value (0.002) indicate a positive and statistically significant spatial autocorrelation.

Table A1.

The table presents a description of the source of data used to prepare the results presented.

Table A1.

The table presents a description of the source of data used to prepare the results presented.

| Map Name/Product | Description | Source/Author | Download Address |

|---|---|---|---|

| State and municipal boundaries | Regional boundaries of Brazilian states and municipal divisions (Scale 1:250,000) | IBGE | https://www.ibge.gov.br/geociencias/informacoes-ambientais/pedologia/10871-pedologia.html?t=downloads (accessed on 10 January 2025) |

| Soil types | Soil mapping of Brazil (Scale 1:250,000) | IBGE | https://www.ibge.gov.br/geociencias/informacoes-ambientais/pedologia/10871-pedologia.html?t=downloads (accessed on 9 March 2025) |

| Land use and land cover | Brazilian annual land use and land cover mapping project - Collection 9.0 (Spatial resolution 30 m × 30 m) | MapBiomas | https://brasil.mapbiomas.org/colecoes-mapbiomas/ (accessed on 9 March 2025) |

| Map of biome boundaries | Boundaries between the six Brazilian biomes, Amazon, Atlantic Forest, Caatinga, Cerrado, Pantanal, and Pampa, compatible with a scale of 1:250,000 | IBGE | https://www.ibge.gov.br/geociencias/informacoes-ambientais/estudos-ambientais/15842-biomas.html?t=acesso-ao-produto (accessed on 10 March 2025) |

| Altimetric map | Digital model representing the altitudes of the topographic surface aggregated to the existing geographical elements on it. Data downloaded in vector format with a scale of 1:250,000. | IBGE | https://www.ibge.gov.br/geociencias/modelos-digitais-de-superficie/modelos-digitais-de-superficie/10856-mde-modelo-digital-de-elevacao.html?=&t=o-que-e (accessed on 9 May 2025) |

| Climate map | The Climate Map, on a scale of 1:500,000, represents the different climate zones of Brazil, grouped by temperature and humidity. | IBGE | https://www.ibge.gov.br/geociencias/informacoes-ambientais/climatologia/15817-clima.html (accessed on 9 May 2025) |

| Soil sampling points | The Brazilian soil information system incorporates soil samples and profiles from all over Brazil, providing a detailed description of the morphological, physical, chemical, and mineralogical characteristics of these profiles with their geographical locations. The information and data contained in this system were generated by technical and scientific projects conducted by Embrapa. | EMBRAPA | https://www.sisolos.cnptia.embrapa.br/ (accessed on 10 January 2025) |

| Land use and land cover | MapBiomas is a collaborative science and technology project that produces annual land use and land cover maps in Brazil. | Mapbiomas | https://plataforma.brasil.mapbiomas.org (accessed on 10 January 2025) |

Table A2.

Description of land use and land cover (LULC) classes in the state of Rio de Janeiro, based on the official classification system adopted by the MapBiomas Project (Collection 9).

Table A2.

Description of land use and land cover (LULC) classes in the state of Rio de Janeiro, based on the official classification system adopted by the MapBiomas Project (Collection 9).

| Land Use and Cover | Description |

|---|---|

| Forest | This class is characterized by the following biomes: Cerrado and Atlantic Forest |

| Herbaceous and Shrubby Vegetation | This class is characterized by flooded fields and marshy areas and by grassland formation |

| Pasture | Predominantly planted pasture areas, directly related to farming activities. |

| Agriculture | Areas occupied by agricultural crops. |

| Forest Plantation | Tree species planted for commercial purposes (e.g., pine, eucalyptus, araucaria). |

| Mosaic of Agriculture and Pasture | Areas of agricultural use where it was not possible to distinguish between pasture and agriculture, and soil exposed during preparation for planting or harvesting. |

| Non-vegetated area | Areas with a significant density of buildings and roads, including areas free of buildings, mining, infrastructure, and industries. |

| Water | Rivers, lakes, dams, reservoirs, and other bodies of water |

Table A3.

Result of the area occupied by each land use class in hectares from 1985 to 1998.

Table A3.

Result of the area occupied by each land use class in hectares from 1985 to 1998.

| Land Use | Areas (Hectares) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | 1991 | 1995 | 1997 | 1998 | |

| Forest | 2,459,117 | 2,438,830 | 2,413,150 | 2,412,189 | 2,415,573 | 2,407,540 | 2,422,640 | 2,427,538 | 2,423,699 |

| Herbaceous and Shrubby vegetation | 191,077 | 188,055 | 187,543 | 183,612 | 182,605 | 185,427 | 177,814 | 181,645 | 182,363 |

| Pasture | 1,749,512 | 1,773,814 | 1,783,661 | 1,799,998 | 1,819,905 | 1,879,863 | 1,910,010 | 1,923,245 | 1,943,990 |

| Agriculture | 2,980,671 | 2,982,002 | 3,023,103 | 3,060,670 | 3,111,938 | 3,144,491 | 3,192,877 | 3,198,332 | 3,201,766 |

| Forest Plantation | 367,512 | 3,523,921 | 3,711,694 | 4,818,231 | 5,834,259 | 6,184,901 | 7,854,868 | 8,144,966 | 851,583 |

| Mosaico f uses | 961,740 | 939,959 | 932,326 | 902,203 | 858,459 | 786,654 | 722,742 | 692,710 | 669,724 |

| Non vegetated areas | 324,125 | 3,424,723 | 344,319 | 349,450 | 355,954 | 361,465 | 388,514 | 398,899 | 405,148 |

Table A4.

The table presents descriptive statistics (mean, median, minimum, maximum, and coefficient of variation) for the data set for each year.

Table A4.

The table presents descriptive statistics (mean, median, minimum, maximum, and coefficient of variation) for the data set for each year.

| Year | Average | Median | Minimum | Max | Coefficient of Variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | 14.77 | 13.25 | 0 | 46.8 | 60.40 |

| 1985 | 11.17 | 10 | 2.5 | 35.1 | 59.3 |

| 1986 | 13.40 | 13.6 | 1.9 | 30.5 | 45.87 |

| 1987 | 18.47 | 11.7 | 5.4 | 59.5 | 79.2 |

| 1988 | 23.2 | 12.4 | 6.8 | 125.3 | 116.1 |

| 1989 | 17.22 | 12.5 | 4.8 | 92.8 | 115.35 |

| 1991 | 17.91 | 18.2 | 2.9 | 35.1 | 47.3 |

| 1995 | 9.31 | 9.25 | 1.87 | 15.6 | 41.63 |

| 1997 | 12.35 | 11.65 | 2.38 | 20.9 | 34.87 |

| 1998 | 16.08 | 12 | 2.05 | 45.35 | 74.26 |

References

- Reynolds, S. Grasslands: Developments Opportunities Perspectives; Frame, J., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; ITPS. Recarbonizing Global Soils: A Technical Manual of Recommended Sustainable Soil Management; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dondini, M.; Martin, M.; De Camillis, C.; Uwizeye, A.; Soussana, J.-F.; Robinson, T.; Steinfeld, H. Global Assessment of Soil Carbon in Grasslands; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, K.; Lal, R. Carbon Sequestration in Grassland Soils. In Carbon Sequestration in Agricultural Ecosystems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 175–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. State of the World’s Forests 2007; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Fultz, L.M.; Moore-Kucera, J.; Acosta-Martínez, V.; Horita, J.; Strauss, R.; Zak, J.; Calderón, F.; Weindorf, D. Soil Carbon Sequestration Potential in Semi-Arid Grasslands in the Conservation Reserve Program. Geoderma 2017, 294, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, S.; Palmer, S.M.; Chapman, P.J. Soil Organic Carbon Stock in Grasslands: Effects of Inorganic Fertilizers, Liming and Grazing in Different Climate Settings. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 223, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, B.; Sommer, R.; Piikki, K.; Söderström, M.; Namirembe, S.; Notenbaert, A.; Tamene, L.; Nyawira, S.; Paul, B. Potential for Soil Organic Carbon Sequestration in Grasslands in East African Countries: A Review. Grassl. Sci. 2020, 66, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.M.; Bishop, T.F.A.; Wilson, B.R. Factors Controlling Soil Organic Carbon Stocks with Depth in Eastern Australia. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2015, 79, 1741–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delonge, M.; Basche, A. Managing Grazing Lands to Improve Soils and Promote Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation: A Global Synthesis. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2018, 33, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, R.S.; Cullen, B.R.; Whetton, P.H.; Robertson, F.A.; Eckard, R.J. Potential Impacts of Climate Change on Soil Organic Carbon and Productivity in Pastures of South Eastern Australia. Agric. Syst. 2018, 167, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardgett, R.D.; Bullock, J.M.; Lavorel, S.; Manning, P.; Schaffner, U.; Ostle, N.; Chomel, M.; Durigan, G.; Fry, E.L.; Johnson, D.; et al. Combatting Global Grassland Degradation. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 720–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquini Neto, R.; Furtado, A.J.; da Silva, G.V.; Lobo, A.A.G.; Abdalla Filho, A.L.; Brunetti, H.B.; Bosi, C.; Pedroso, A.dF.; Pezzopane, J.R.M.; Oliveira, P.P.A.; et al. Forage Accumulation and Nutritive Value in Extensive, Intensive, and Integrated Pasture-Based Beef Cattle Production Systems. Crop Pasture Sci. 2024, 75, CP24043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, C.; Zhou, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Z.; Li, J.; Qi, J.; Odeh, I. Quantitative Assessment of the Contri-butions of Climate Change and Human Activities on Global Grassland Degradation. Environ. Earth Sci. 2014, 72, 4273–4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, K.; Sukartiningsih; Hayakawa, C.; Inagaki, Y.; Kosaki, T. Effects of Land Use Change on Turnover and Storage of Soil Organic Matter in a Tropical Forest. Plant Soil 2020, 446, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popin, G.V.; de Resende, M.E.B.; Locatelli, J.L.; Santos, R.S.; Siqueira-Neto, M.; Brando, P.M.; Neill, C.; Cerri, C.E.P. Land-Use Change and Deep-Soil Carbon Distribution on the Brazilian Amazon-Cerrado Agricultural Frontier. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 381, 109451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.M.d.S.; Paustian, K.; Davies, C.A.; Cherubin, M.R.; Franco, A.L.C.; Cerri, C.C.; Cerri, C.E.P. Soil Carbon Changes in Areas Undergoing Expansion of Sugarcane into Pastures in South-Central Brazil. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 228, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias-Filho, M.B. Degradação de Pastagens: O Que é e Como Evitar, 1st ed.; Embrapa: Brasília, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Abdalla, K.; Mutema, M.; Chivenge, P.; Everson, C.; Chaplot, V. Grassland Degradation Significantly Enhances Soil CO2 Emission. Catena 2018, 167, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, T.J.; Siqueira, D.S.; de Figueiredo, E.B.; Bordonal, R.d.O.; Moitinho, M.R.; Marques Júnior, J.; La Scala, N. Soil Carbon Stock Estimations: Methods and a Case Study of the Maranhão State, Brazil. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 16410–16427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Land Statistics: Global, Regional and Country Trends, 1961–2018; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mapbiomas. Projeto MapBiomas–Mapeamento Anual de Cobertura e Uso Da Terra Do Brasil. A Evolução Da Pastagem Nos Últimos 36 Anos-Coleção 6. 2020. Available online: https://brasil.mapbiomas.org/map/colecao-6/ (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Damian, J.M.; da Silva Matos, E.; e Pedreira, B.C.; de Faccio Carvalho, P.C.; Premazzi, L.M.; Williams, S.; Paustian, K.; Cerri, C.E.P. Predicting Soil C Changes after Pasture Intensification and Diversification in Brazil. Catena 2021, 202, 105238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavanti, R.F.R.; Montanari, R.; Panosso, A.R.; La Scala, N.; Chiquitelli Neto, M.; Freddi, O.d.S.; Paz González, A.; de Carvalho, M.A.C.; Soares, M.B.; Tavanti, T.R.; et al. What Is the Impact of Pasture Reform on Organic Carbon Compartments and CO2 Emissions in the Brazilian Cerrado? Catena 2020, 194, 104702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Valle Júnior, R.F.; Siqueira, H.E.; Valera, C.A.; Oliveira, C.F.; Sanches Fernandes, L.F.; Moura, J.P.; Pacheco, F.A.L. Diagnosis of Degraded Pastures Using an Improved NDVI-Based Remote Sensing Approach: An Application to the Environmental Protection Area of Uberaba River Basin (Minas Gerais, Brazil). Remote Sens. Appl. 2019, 14, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jank, L.; Barrios, S.C.; do Valle, C.B.; Simeão, R.M.; Alves, G.F. The Value of Improved Pastures to Brazilian Beef Production. Crop Pasture Sci. 2014, 65, 1132–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profiles Brazil; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. Plano ABC-Agricultura de Baixa Emissão de Carbono. 2010. Available online: https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/sustentabilidade/planoabc-abcmais/plano-abc (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Boddey, R.M.; Xavier, D.F.; Alves, B.J.R.; Urquiaga, S. Brazilian Agriculture: The Transition to Sustainability. J. Crop Prod. 2003, 9, 593–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Investigação (MCTI). Relatório de Referência–Setor Uso Da Terra, Mudança Do Uso Da Terra e Florestas. Terceiro Inventário Brasileiro de Emissões e Remoções Antrópicas de Gases de Efeito Estufa; Ministério da Ciência e Tecnologia: Brasília, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- de Mello, K.; Taniwaki, R.H.; de Paula, F.R.; Valente, R.A.; Randhir, T.O.; Macedo, D.R.; Leal, C.G.; Rodrigues, C.B.; Hughes, R.M. Multiscale Land Use Impacts on Water Quality: Assessment, Planning, and Future Perspectives in Brazil. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 270, 110879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarré, R.; Macedo, R.; Cantarutti, R.B.; Rezende, C.d.P.; Pereira, J.M.; Ferreira, E.; Alves, B.J.R.; Urquiaga, S.; Boddey, R.M. The Effect of the Presence of a Forage Legume on Nitrogen and Carbon Levels in Soils under Brachiaria Pastures in the Atlantic Forest Region of the South of Bahia, Brazil. Plant Soil 2001, 234, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, L.C.; Gama-Rodrigues, E.F.; Gama-Rodrigues, A.C. Soil Carbon Stocks of Ultisols under Different Land Use in the Atlantic Rainforest Zone of Brazil. Geoderma Reg. 2016, 7, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltran-Barbieri, R.; Féres, J.G. Degraded Pastures in Brazil: Improving Livestock Production and Forest Restoration. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8, 201854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rocha Junior, P.R.; Andrade, F.V.; Mendonça, E.d.S.; Donagemma, G.K.; Fernandes, R.B.A.; Bhattharai, R.; Kalita, P.K. Soil, Water, and Nutrient Losses from Management Alternatives for Degraded Pasture in Brazilian Atlantic Rainforest Biome. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 583, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R.; Smith, P.; Jungkunst, H.F.; Mitsch, W.J.; Lehmann, J.; Nair, P.K.R.; McBratney, A.B.; de Moraes Sá, J.C.; Schneider, J.; Zinn, Y.L.; et al. The Carbon Sequestration Potential of Terrestrial Ecosystems. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2018, 73, 145A–152A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockmann, U.; Adams, M.A.; Crawford, J.W.; Field, D.J.; Henakaarchchi, N.; Jenkins, M.; Minasny, B.; McBratney, A.B.; Courcelles, V.d.R.d.; Singh, K.; et al. The Knowns, Known Unknowns and Unknowns of Sequestration of Soil Organic Carbon. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2013, 164, 80–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeferino, L.B.; Lustosa Filho, J.F.; dos Santos, A.C.; Cerri, C.E.P.; de Oliveira, T.S. Soil Carbon and Nitrogen Stocks Following Forest Conversion to Long-Term Pasture in Amazon Rainforest-Cerrado Transition Environment. Catena 2023, 231, 107346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, W.S.; Gorelik, S.R.; Baccini, A.; Aragon-Osejo, J.L.; Josse, C.; Meyer, C.; Macedo, M.N.; Augusto, C.; Rios, S.; Katan, T.; et al. The Role of Forest Conversion, Degradation, and Disturbance in the Carbon Dynamics of Amazon Indigenous Territories and Protected Areas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 3015–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asner, G.P.; Elmore, A.J.; Olander, L.P.; Martin, R.E.; Harris, A.T. Grazing Systems, Ecosystem Responses, and Global Change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2004, 29, 261–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonte, S.J.; Nesper, M.; Hegglin, D.; Velásquez, J.E.; Ramirez, B.; Rao, I.M.; Bernasconi, S.M.; Bünemann, E.K.; Frossard, E.; Oberson, A. Pasture Degradation Impacts Soil Phosphorus Storage via Changes to Aggregate Associated Soil Organic Matter in Highly Weathered Tropical Soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 68, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Zhu, G.; Tang, Z.; Shangguan, Z. Global Patterns of the Effects of Land-Use Changes on Soil Carbon Stocks. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2016, 5, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittl, T.F.; Oliveira, D.; Cerri, C.E.P. Soil Carbon Stock Changes under Different Land Uses in the Amazon. Geoderma Reg. 2017, 10, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resende, T.M.; Rosolen, V.; Bernoux, M.; Brito, J.L.S.; Borges, E.N.; Almeida, F.P. Atributos Físicos e Carbono Orgânico Em Solo Sob Cerrado Convertido Para Pastagem e Sistema Misto. Soc. Nat. 2015, 27, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zago, L.M.S.; Ramalho, W.P.; Caramori, S. Does Crop-Livestock-Forest Systems Contribute to Soil Quality in Brazilian Savannas? Floresta E Ambiente 2019, 26, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Azevedo, T.R.; Costa, C.; Brandão, A.; Dos Santos Cremer, M.; Piatto, M.; Tsai, D.S.; Barreto, P.; Martins, H.; Sales, M.; Galuchi, T.; et al. SEEG Initiative Estimates of Brazilian Greenhouse Gas Emissions from 1970 to 2015. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielniczuk, J. Matéria Orgânica e a Sustentabilidade de Sistemas Agrícolas. In Fundamentos da Matéria Orgânica do Solo: Ecossistemas Tropicais Subtropicais; Metropole: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2008; pp. 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, R.P. Qualidade Do Solo Sob Sistemas Agroflorestais, Pastagens e Agrícolas No Bioma Mata Atlântica. Ph.D. Thesis, Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRRJ), Seropédica, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Segnini, A.; Xavier, A.A.P.; Otaviani-Junior, P.L.; Oliveira, P.P.A.; Pedroso, A.d.F.; Praes, M.F.F.M.; Ro-drigues, P.H.M.; Milori, D.M.B.P. Soil Carbon Stock and Humification in Pastures under Different Levels of Intensification in Brazil. Sci. Agric. 2019, 76, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, L.G.; Alves, M.A.S.; Grelle, C.E.V. Actions against Sustainability: Dismantling of the Environmental Policies in Brazil. Land Use Policy 2021, 104, 105384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, V.; Andreoli, C.V.; Bruna, G.C.; Philippi, A. History and Evolution of the Environmental Man-agement System in Brazil. História Ambient. Latinoam. Caribena 2021, 11, 275–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losekann, C.; Paiva, R.L. Brazilian Environmental Policy: Shared Responsibility and Dismantling. Ambiente Soc. 2024, 27, e01764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, K.S.; Junqueira Júnior, J.A.; Sousa, P.E.d.O.; Moreira, H.S.; Baliza, D.P. A Evolução Da Legislação Ambiental No Contexto Histórico Brasileiro. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e14010212087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE-Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Censo Demográfico de 2022; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2022. Available online: https://censo2022.ibge.gov.br/panorama/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Alvares, C.A.; Stape, J.L.; Sentelhas, P.C.; de Moraes Gonçalves, J.L.; Sparovek, G. Köppen’s Climate Clas-sification Map for Brazil. Meteorol. Z. 2013, 22, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros Ozório, J.M.; Rosset, J.S.; Schiavo, J.A.; Panachuki, E.; Souza, C.B.d.S.; Menezes, R.d.S.; Ximenes, T.S.; Castilho, S.C.d.P.; Marra, L.M. Estoque de carbono e agregação do solo sob fragmentos florestais no bioma mata atlântica e cerrado. Rev. Bras. Ciências Ambient. 2019, 53, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, A.; Lumbreras, J.; Wittern, K.; Lemos, A. Levantamento de Reconhecimento de Baixa Intensidade dos Solos do Estado do Rio de Janeiro; Embrapa Solos: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sattler, D.; Seliger, R.; Nehren, U.; de Torres, F.N.; da Silva, A.S.; Raedig, C.; Hissa, H.R.; Heinrich, J. Pasture Degradation in South East Brazil: Status, Drivers and Options for Sustainable Land Use Under Climate Change. In Climate Change Adaptation in Latin America: Managing Vulnerability, Fostering Resilience; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, J.B.S.; de Felício, P.E. Production Systems—An Example from Brazil. Meat Sci. 2010, 84, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Censo Agropecuário 2006; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2007. Available online: https://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Censo_Agropecuario/Censo_Agropecuario_2006/Segunda_Apuracao/censoagro2006_2aapuracao.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Bernoux, M.; da Conceição Santana Carvalho, M.; Volkoff, B.; Cerri, C.C. Brazil’s Soil Carbon Stocks. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2002, 66, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embrapa. Manual de Métodos de Análise de Solo, 2nd ed.; Claessen, M.E.C., Ed.; Embrapa Solos: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, M.; Mendes, L.M.S.; Silva, W.L.C.; Sparovek, G. A National Soil Profile Database for Brazil Available to International Scientists. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2005, 69, 649–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MapBiomas. Mapbiomas Brasil. 2024. Available online: https://brasil.mapbiomas.org/estatisticas/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Müller, M.M.L.; Guimarães, M.F.; Desjardins, T.; Mitja, D. The Relationship between Pasture Degradation and Soil Properties in the Brazilian Amazon: A Case Study. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2004, 103, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RStudio Team. RStudio. Integrated Development Environment for R; RStudio Team: Boston, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos, C.A.; Rezende, C.d.P.; Machado Pinheiro, É.F.; Pereira, J.M.; Alves, B.J.R.; Urquiaga, S.; Boddey, R.M. Changes in Soil Carbon Stocks after Land-Use Change from Native Vegetation to Pastures in the Atlantic Forest Region of Brazil. Geoderma 2019, 337, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assunção, S.A.; Pereira, M.G.; Rosset, J.S.; Berbara, R.L.L.; García, A.C. Carbon Input and the Structural Quality of Soil Organic Matter as a Function of Agricultural Management in a Tropical Climate Region of Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 658, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froufe, L.C.M.; Rachwal, M.F.G.; Seoane, C.E.S. Potencial de Sistemas Agroflorestais Multiestrata Para Sequestro de Carbono Em Áreas de Ocorrência de Floresta Atlântica. Pesqui. Florest. Bras. 2011, 31, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchane, M.N.; Sileshi, G.W.; Gripenberg, S.; Jonsson, M.; Pumariño, L.; Barrios, E. Agroforestry Boosts Soil Health in the Humid and Sub-Humid Tropics: A Meta-Analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 295, 106899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dortzbach, D.; Pereira, M.G.; Blainski, É.; González, A.P. Estoque de C e Abundância Natural de 13C Em Razão Da Conversão de Áreas de Floresta e Pastagem Em Bioma Mata Atlântica. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2015, 39, 1643–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, M.C.G.d.; Matos, E.S.; Bidone, E.D.; Rodrigues, R.d.A.R.; Cordeiro, R.C. Changes in Soil Carbon Stocks under Integrated Crop-Livestock-Forest System in the Brazilian Amazon Region. Agric. Sci. 2017, 8, 904–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumbore, S.; Barbosa de Camargo, P. Soil Carbon Dynamics. Geophysical Monograph Series. 2009, 186, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, I.C.; Alves, M.A.; Pena, A.N.L.; Ferreira, E.A.; Frazão, L.A. Changing the Land Use from De-graded Pasture into Integrated Farming Systems Enhance Soil Carbon Stocks in the Cerrado Biome. Acta Sci. Agron. 2023, 46, e63601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.W.; Grunwald, S.; Myers, D.B. Spatiotemporal Modeling of Soil Organic Carbon Stocks across a Subtropical Region. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 461–462, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friess, D.A.; Yando, E.S.; Alemu I, J.B.; Wong, L.-W.; Soto, S.D.; Bhatia, N. Ecosystem Services and Disservices of Mangrove Forests and Salt Marshes. In Oceanography and Marine Biology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 107–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seliger, R.; Sattler, D.; Soares da Silva, A.; da Costa, G.C.P.; Heinrich, J. Rehabilitation of Degraded Sloped Pastures: Lessons Learned in Itaocara, Rio de Janeiro. In Strategies and Tools for a Sustainable Rural Rio de Janeiro; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, S.M.F.; Ogle, S.M.; Cerri, C.E.P.; Cerri, C.C. Effect of Grassland Management on Soil Carbon Se-questration in Rondônia and Mato Grosso States, Brazil. Geoderma 2009, 149, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerri, C.E.P.; Paustian, K.; Bernoux, M.; Victoria, R.L.; Melillo, J.M.; Cerri, C.C. Modeling Changes in Soil Organic Matter in Amazon Forest to Pasture Conversion with the Century Model. Glob. Change Biol. 2004, 10, 815–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, D.C.; Maia, S.M.F.; Freitas, R.d.C.A.; Cerri, C.E.P. Changes in Soil Carbon and Soil Carbon Sequestration Potential under Different Types of Pasture Management in Brazil. Reg. Environ. Change 2022, 22, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adame, M.F.; Kauffman, J.B.; Medina, I.; Gamboa, J.N.; Torres, O.; Caamal, J.P.; Reza, M.; Herrera-Silveira, J.A. Carbon Stocks of Tropical Coastal Wetlands within the Karstic Landscape of the Mexican Caribbean. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DelVecchia, A.G.; Bruno, J.F.; Benninger, L.; Alperin, M.; Banerje, O.; De Dios Morales, J. Organic Carbon Inventories in Natural and Restored Ecuadorian Mangrove Forests. PeerJ 2014, 2014, e388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]