An Integrated Approach to Assessing the Impacts of Urbanization on Urban Flood Hazards in Hanoi, Vietnam

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Constructing Flood Maps from Sentinel-1 SAR

- Preprocessing: Orbit and terrain correction, radiometric calibration, and speckle filtering using the Refined Lee filter (5 × 5 kernel).

- Flood classification: Calculation of the SAR-based NDWI index, application of Otsu’s automatic thresholding method to classify water and non-water pixels, and generation of binary flood maps for each image [78].

- Flood frequency mapping: The image series was compiled to count the number of times each pixel was classified as inundated during the period from 2015 to 2024. The resulting pixel-occurrence values were then categorized into five flood-frequency levels—very low, low, medium, high, and very high—using the equal-interval classification method based on the statistical distribution of inundation counts [57,79].

- Validation: Using 148 historical flood points (2012–2024) collected from official reports, media sources, and GPS surveys for spatial–temporal matching. The validation focused on flood occurrence and distribution rather than flood depth or duration, due to the limited resolution of reference data.

3.3. Analysis of Urbanization and Land Use

3.4. Flood Risk Assessment by Geomorphology

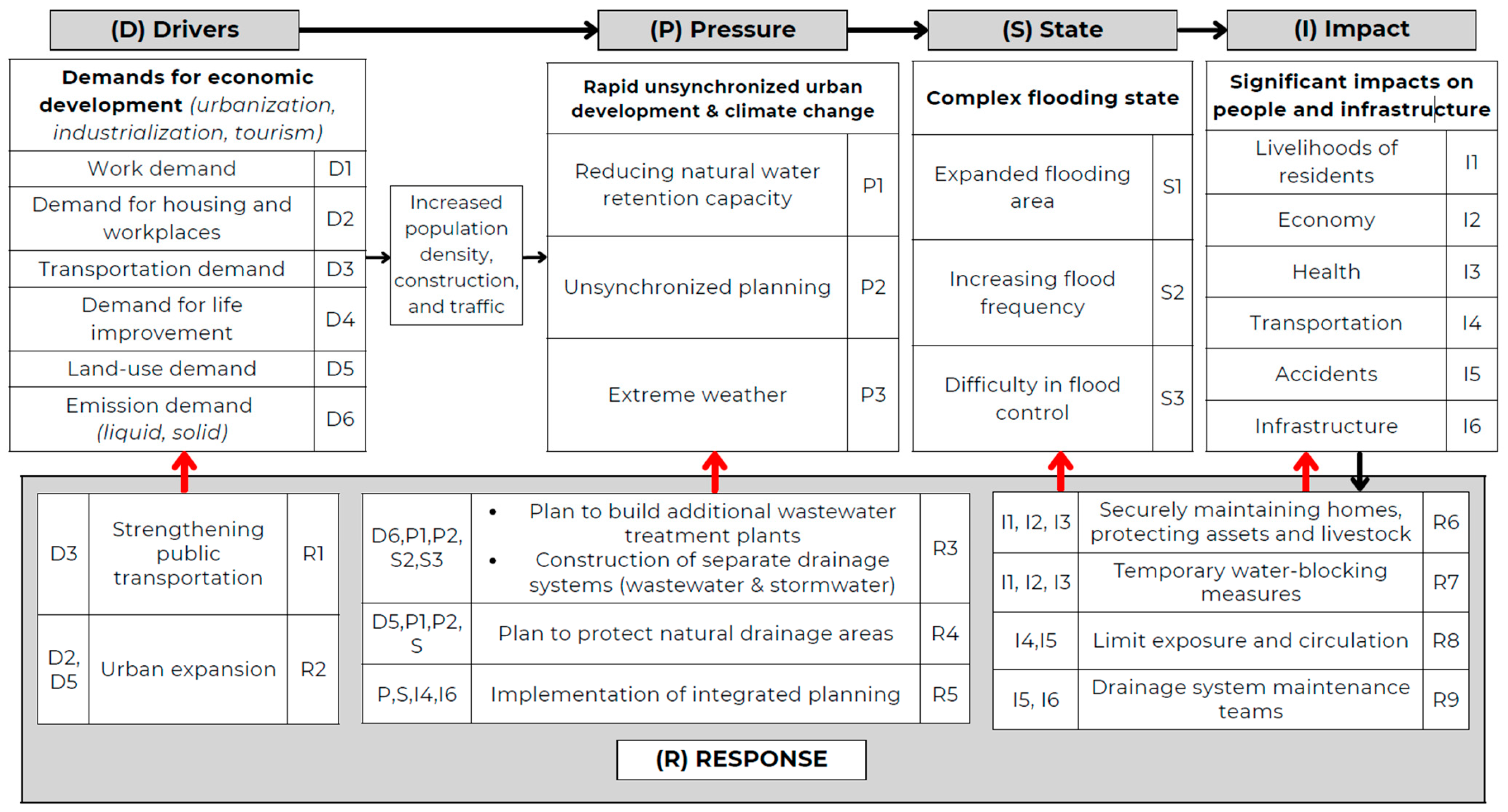

3.5. DPSIR Framework

- Drivers: Population growth, rapid urbanization, and climate change.

- Pressures: Increasing impervious surfaces, infilling of lakes and ponds, and reduced drainage capacity.

- State: Current flood frequency and urbanization maps, combined with geomorphological conditions.

- Impacts: Results from field and sociological surveys assessing effects on livelihoods, infrastructure, and the economy.

- Responses: Policies, planning solutions, and infrastructure projects that have been implemented or are under development.

3.6. Field Surveys and Sociological Investigations

3.7. Study Process

- Data collection and preprocessing: Compilation and preparation of Sentinel-1, ALOS, VLULC, DEM, geomorphological, flood point, population, and drainage datasets.

- Geomorphological and urbanization analysis: Generation of old and new urban maps and analysis by geomorphological unit.

- Flood mapping and frequency analysis: SAR image processing, flood frequency calculation, and validation using historical flood points.

- Risk assessment and adaptive planning proposals: Integration of Weighted Overlay results with the DPSIR framework and social survey data to identify high-risk zones and propose adaptation-oriented solutions.

4. Results and Discussion

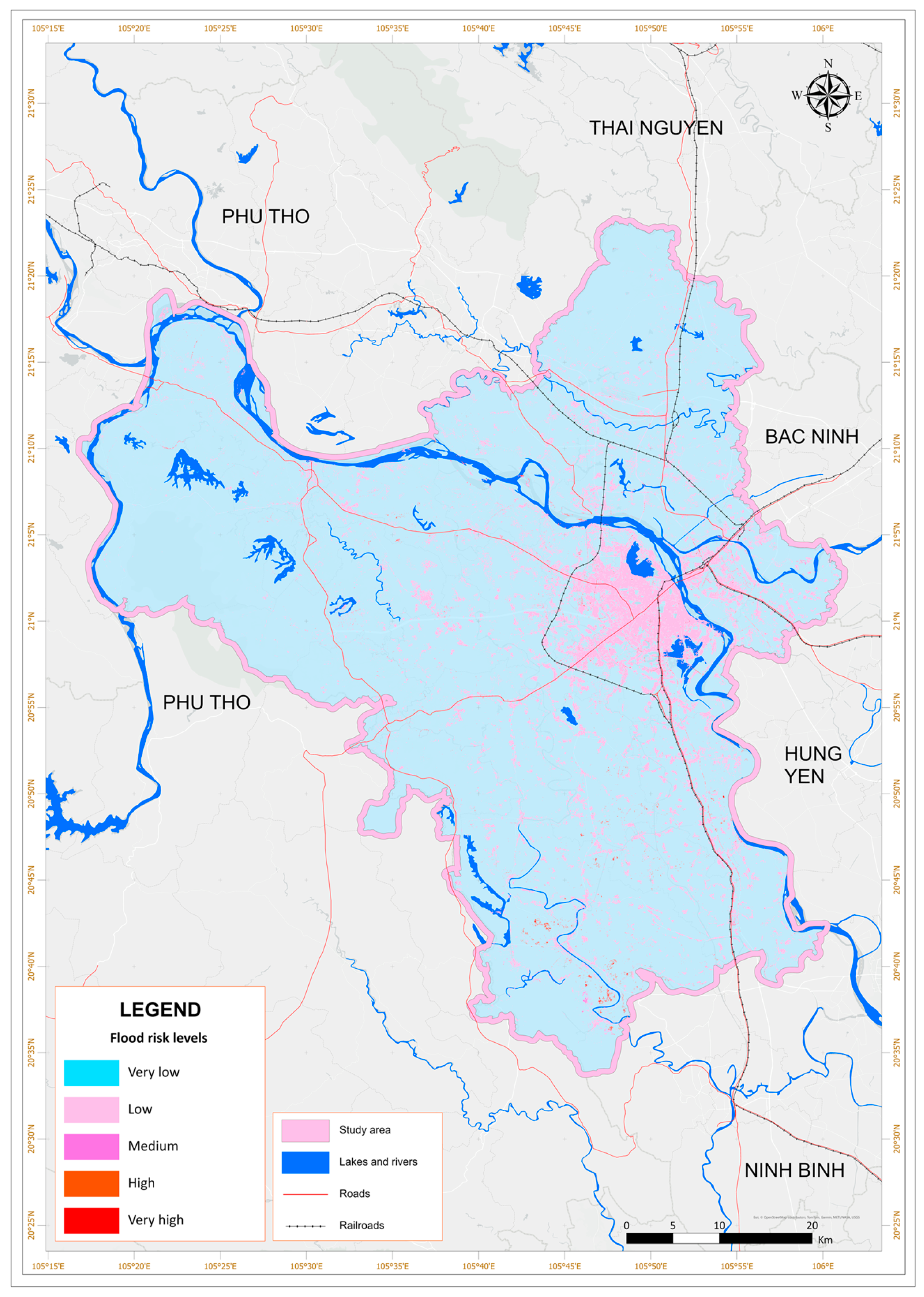

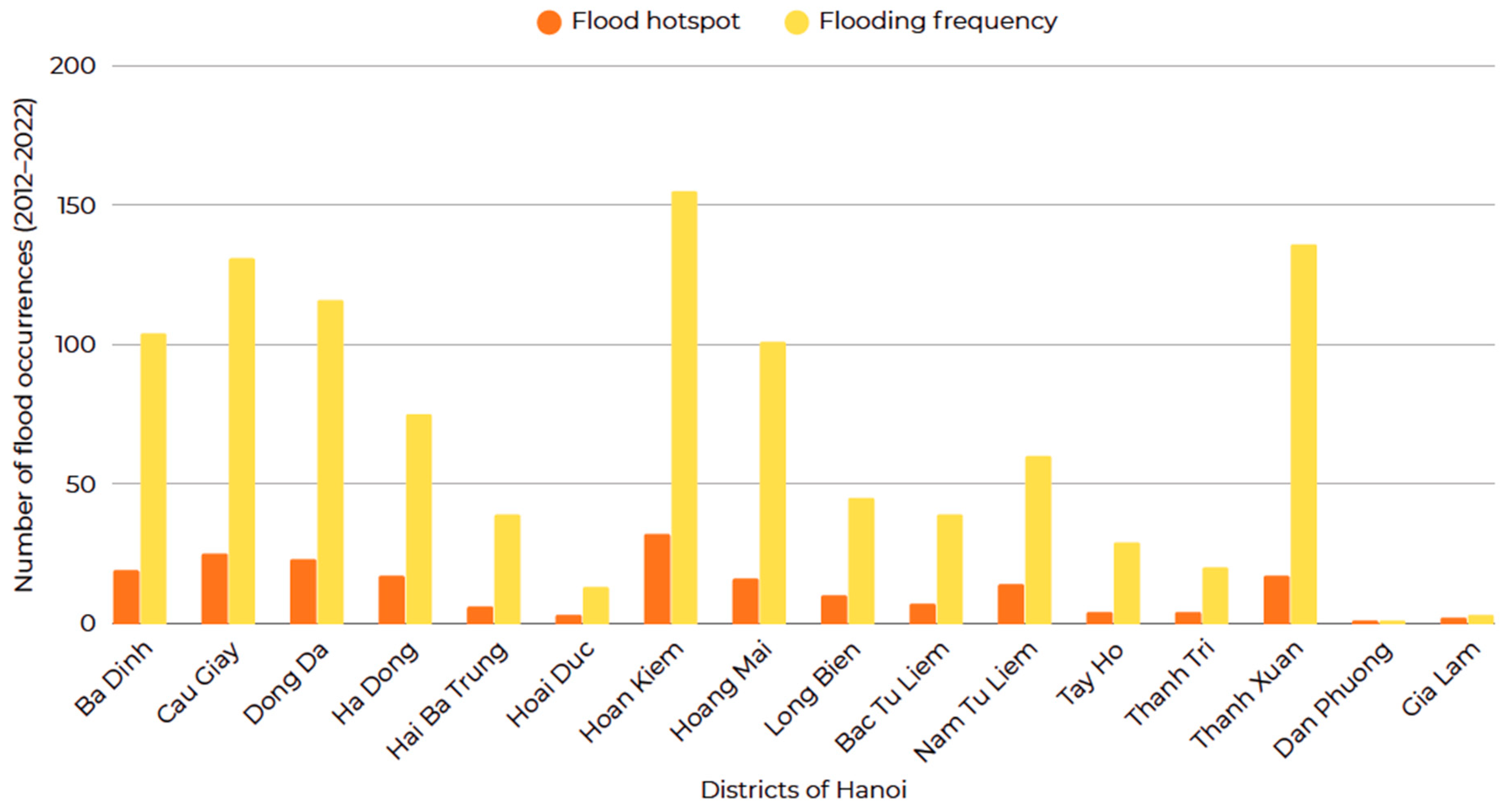

4.1. Flood Frequency in Hanoi City (2015–2024)

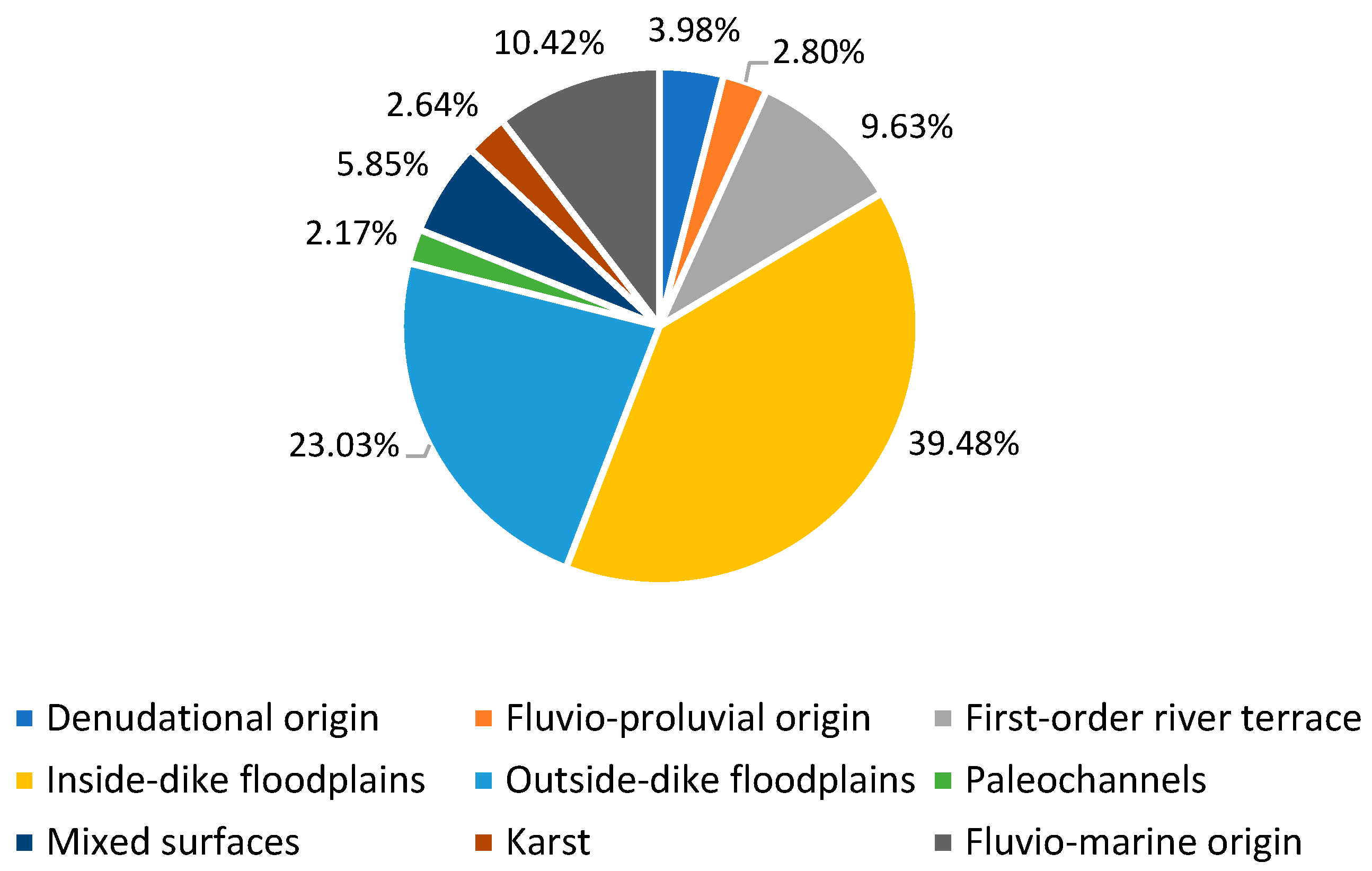

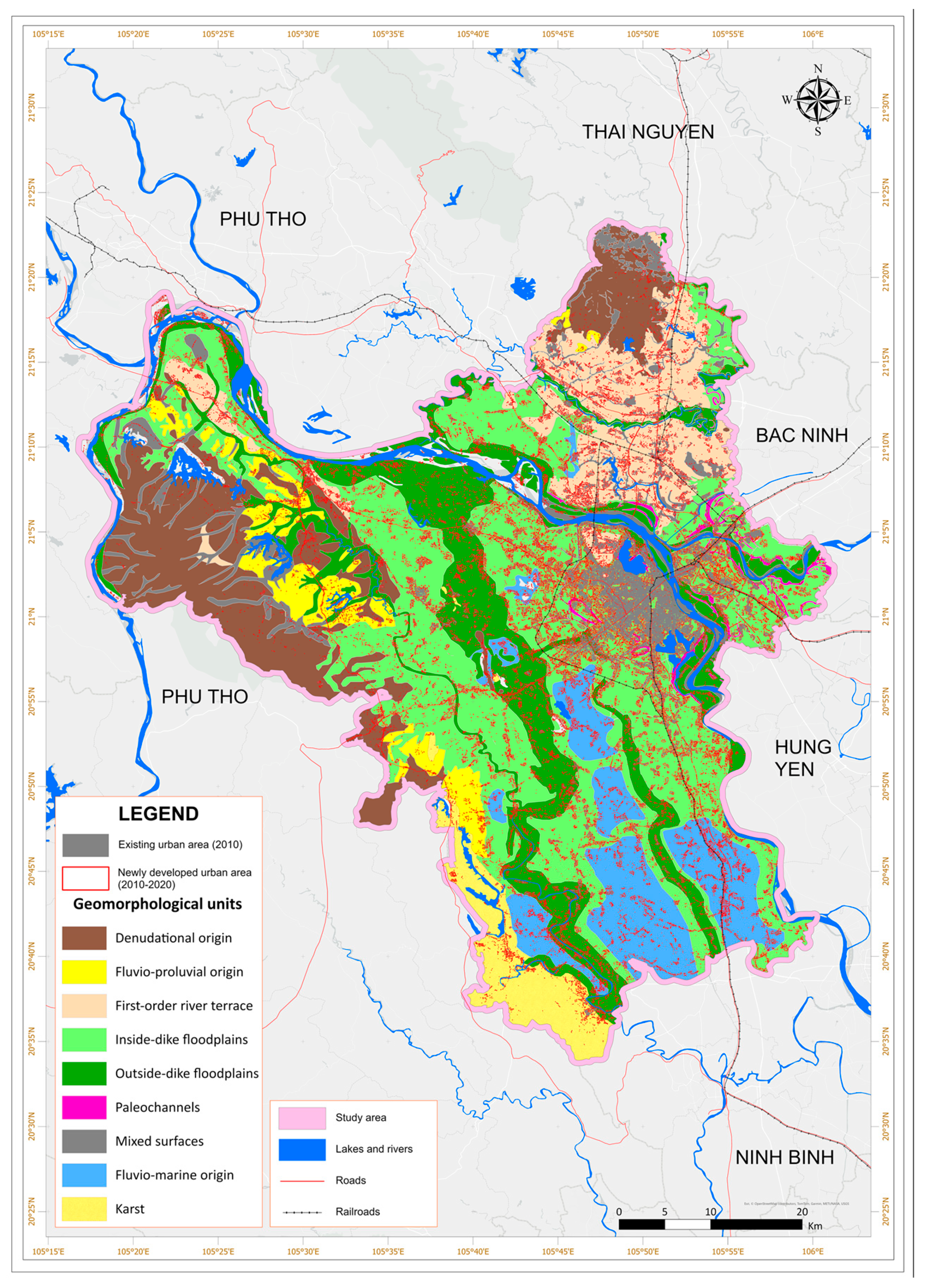

4.2. Urbanization Trends on Geomorphological Units in Hanoi

4.3. Statistics of Inundated Areas by Geomorphological Units

4.4. Characteristics of Inundation in Urban Areas (New and Old Urban Areas)

4.5. Assessment of Flood Risk Using a Geomorphological Approach

4.6. DPSIR Framework in Assessing Urban Flooding and Spatial Planning in Hanoi

4.6.1. Drivers

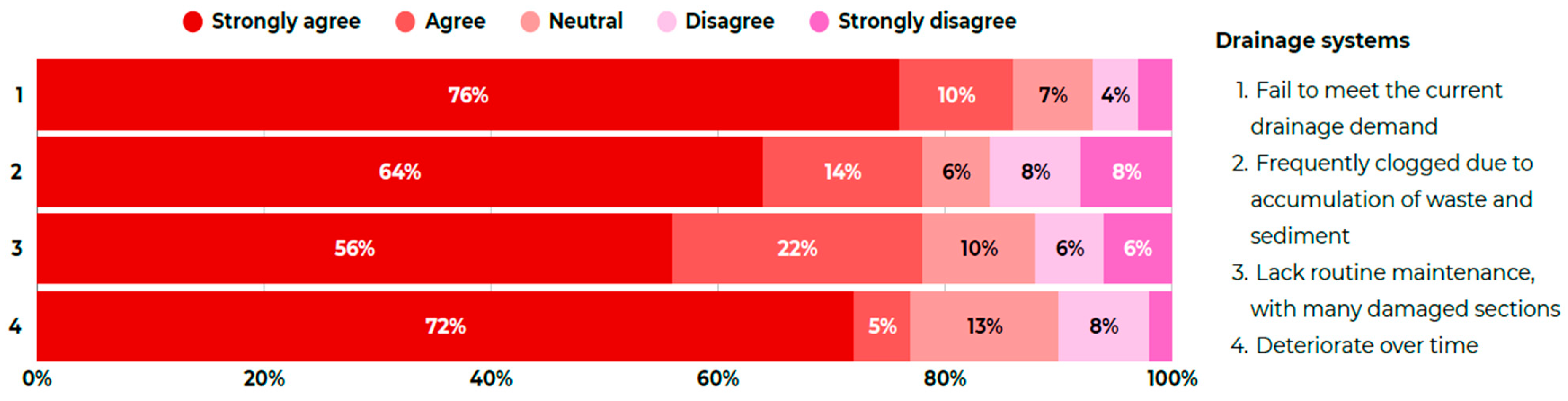

4.6.2. Pressures

4.6.3. State

4.6.4. Impacts

4.6.5. Responses

4.7. Planning Orientations for Flood-Adaptive Urban Development in Hanoi

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| ALOS | Advanced Land Observing Satellite |

| CNN–LSTM | Convolutional Neural Network—Long Short-Term Memory |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| DPSIR | Drivers–Pressures–State–Impacts–Responses |

| ESA | European Space Agency |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| GEE | Google Earth Engine |

| IFRI | Integrated Flood Risk Index |

| LID | Low-Impact Development |

| MCDA | Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis |

| MODIS | Moderate-Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer |

| OA | Overall Accuracy |

| PPP | Public–Private Partnership |

| SAR | Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| VLULC | Vietnam Land Use Land Cover |

References

- Duan, W.; He, B.; Nover, D.; Fan, J.; Yang, G.; Chen, W.; Meng, H.; Liu, C. Floods and Associated Socioeconomic Damages in China over the Last Century. Nat. Hazards 2016, 82, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, T.K. Global Exposure to Flood Risk and Poverty. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najibi, N.; Devineni, N. Recent Trends in the Frequency and Duration of Global Floods. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2018, 9, 757–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellman, B.; Sullivan, J.A.; Kuhn, C.; Kettner, A.J.; Doyle, C.S.; Brakenridge, G.R.; Erickson, T.A.; Slayback, D.A. Satellite Imaging Reveals Increased Proportion of Population Exposed to Floods. Nature 2021, 596, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Meteorological Organization. WMO Atlas of Mortality and Economic Losses from Weather, Climate and Water-Related Hazards (1970–2021); World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-92-63-11267-5. [Google Scholar]

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). World Disasters Report 2020: Come Heat or High Water; World Disasters Report 2020 IFRC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-2-9701289-5-3. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, H.; Lawrence, D.; Lang, M.; Martinkova, M.; Kjeldsen, T.R. Review of Trend Analysis and Climate Change Projections of Extreme Precipitation and Floods in Europe. J. Hydrol. 2014, 519, 3634–3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, R.; VishnuRadhan, R.; Eldho, T.I.; Inamdar, A. Flood Risk and Adaptation in Indian Coastal Cities: Recent Scenarios. Appl. Water Sci. 2018, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, R.-S.; Liu, M.; Lu, M.; Zhang, L.-J.; Wang, J.-J.; Xu, S.-Y. Waterlogging Risk Assessment Based on Land Use/Cover Change: A Case Study in Pudong New Area, Shanghai. Environ. Earth Sci. 2010, 61, 1113–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Burian, S.J. Evaluating Real-Time Control of Stormwater Drainage Network and Green Stormwater Infrastructure for Enhancing Flooding Resilience under Future Rainfall Projections. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 198, 107123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Uyttenhove, P.; Van Eetvelde, V. Planning Green Infrastructure to Mitigate Urban Surface Water Flooding Risk—A Methodology to Identify Priority Areas Applied in the City of Ghent. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 194, 103703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham Anh, T. Water Urbanism in Hanoi, Vietnam: An Investigation into Possible Interplays of Infrastructure, Urbanism and Landscape of the City’s Dyke System; KU Leuven, Science, Engineering & Technology: Heverlee, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tramblay, Y.; Mimeau, L.; Neppel, L.; Vinet, F.; Sauquet, E. Detection and Attribution of Flood Trends in Mediterranean Basins. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 23, 4419–4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, T.T. Floods and Prevention Methods; Science and Technology Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2000. (In Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- Ringo, J.; Sabai, S.; Mahenge, A. Performance of Early Warning Systems in Mitigating Flood Effects. A Review. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2024, 210, 105134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofia, G.; Roder, G.; Dalla Fontana, G.; Tarolli, P. Flood Dynamics in Urbanised Landscapes: 100 Years of Climate and Humans’ Interaction. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, D.V.; Hieu, N. Refinement of the Digital Elevation Model Based on Geomorphology for Flood Research in the Lower Thu Bon River. VNU J. Sci. Nat. Sci. Technol. 2004, IVAP/2004, 9–15. (In Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- Mulyasari, F.; Shaw, R.; Takeuchi, Y. Chapter 12 Urban Flood Risk Communication for Cities. In Climate and Disaster Resilience in Cities; Shaw, R., Sharma, A., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2011; Volume 6, ISBN 978-0-85724-319-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, D.V.; Bac, D.D.; Hieu, N.; Bac, D.K. Geomorphological Research for Planning the Western Expansion of Hanoi City. In Proceedings of the 10th Southeast Asian Geography Conference; Hanoi National University of Education Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2010; pp. 132–139. (In Vietnamese). [Google Scholar]

- Bich, T.H.; Quang, L.N.; Thanh Ha, L.T.; Duc Hanh, T.T.; Guha-Sapir, D. Impacts of Flood on Health: Epidemiologic Evidence from Hanoi, Vietnam. Glob. Health Action 2011, 4, 6356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabangchang, O.; Allaire, M.; Leangcharoen, P.; Jarungrattanapong, R.; Whittington, D. Economic Costs Incurred by Households in the 2011 Greater Bangkok Flood. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, M.J.; Chen, A.S.; Djordjević, S.; Butler, D.; Mark, O. Urban Flood Impact Assessment: A State-of-the-Art Review. Urban Water J. 2015, 12, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues do Amaral, F.; Gratiot, N.; Pellarin, T.; Tu, T.A. Assessing Typhoon-Induced Compound Flood Drivers: A Case Study in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 23, 3379–3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction 2019; UNDRR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ngan, D.T. Geomorphological Study in Flood Hazard Warning for the Hanoi Area. Bachelor’s Thesis, VNU University of Science, Hanoi, Vietnam, 2009. (In Vietnamese). [Google Scholar]

- Thien, T.D.; Ha, D.V.; Yen, N.T.; Hung, C.M. Challenges for Urban Water Management in Hanoi. In Proceedings of the National Conference on Research, Transfer, and Application of Science and Technology for Sustainable Development, Hanoi, Vietnam, 21 December 2021; Science and Technology Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2021; pp. 59–69. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357302037_NHUNG_THACH_THUC_DOI_VOI_QUAN_LY_NUOC_DO_THI_HA_NOI (accessed on 12 September 2025). (In Vietnamese).

- Thien, T.D.; Linh, D.T.; Gam, V.T.; Thu, N.T.; Chien, H.C. Current Situation of Urban Flooding in Hanoi during 2012–2022. Vietnam. Archit. J. 2023. Available online: https://www.tapchikientruc.com.vn/chuyen-muc/thuc-trang-ngap-ung-do-thi-ha-noi-giai-doan-2012-2022.html (accessed on 12 September 2025). (In Vietnamese).

- Dung, N.T. Scientific Basis for Planning Urban Flood Control Based on Risk Analysis; Construction Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2023. (In Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- Pappenberger, F.; Beven, K.J.; Ratto, M.; Matgen, P. Multi-Method Global Sensitivity Analysis of Flood Inundation Models. Adv. Water Resour. 2008, 31, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Knijff, J.M.; Younis, J.; De Roo, A.P.J. LISFLOOD: A GIS-based Distributed Model for River Basin Scale Water Balance and Flood Simulation. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2010, 24, 189–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, G.J.-P.; Neal, J.C.; Voisin, N.; Andreadis, K.M.; Pappenberger, F.; Phanthuwongpakdee, N.; Hall, A.C.; Bates, P.D. A First Large-Scale Flood Inundation Forecasting Model. Water Resour. Res. 2013, 49, 6248–6257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D.; Herath, S.; Musiake, K. Flood Inundation Simulation in a River Basin Using a Physically Based Distributed Hydrologic Model. Hydrol. Process. 2000, 14, 497–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, P.D.; De Roo, A.P.J. A Simple Raster-Based Model for Flood Inundation Simulation. J. Hydrol. 2000, 236, 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Pan, B. An Urban Storm-Inundation Simulation Method Based on GIS. J. Hydrol. 2014, 517, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merwade, V.; Olivera, F.; Arabi, M.; Edleman, S. Uncertainty in Flood Inundation Mapping: Current Issues and Future Directions. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2008, 13, 608–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, S.H.; Gan, T.Y. Multi-Criteria Approach to Develop Flood Susceptibility Maps in Arid Regions of Middle East. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, C.; Tran, H.X.; Pham, B.T.; Al-Ansari, N.; Tran, T.Q.; Duong, N.Q.; Dao, N.H.; Nguyen, L.P.; Nguyen, H.D.; Thu Ta, H.; et al. Framework of Spatial Flood Risk Assessment for a Case Study in Quang Binh Province, Vietnam. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-R.; Yeh, C.-H.; Yu, B. Integrated Application of the Analytic Hierarchy Process and the Geographic Information System for Flood Risk Assessment and Flood Plain Management in Taiwan. Nat. Hazards 2011, 59, 1261–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakis, N.; Kougias, I.; Patsialis, T. Assessment of Flood Hazard Areas at a Regional Scale Using an Index-Based Approach and Analytical Hierarchy Process: Application in Rhodope–Evros Region, Greece. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 538, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, H.N.; Fukuda, H.; Nguyen, M.N. Assessment of the Susceptibility of Urban Flooding Using GIS with an Analytical Hierarchy Process in Hanoi, Vietnam. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.X.; Nguyen, A.T.; Ngo, A.T.; Phan, V.T.; Nguyen, T.D.; Do, V.T.; Dao, D.C.; Dang, D.T.; Nguyen, A.T.; Nguyen, T.K.; et al. A Hybrid Approach Using GIS-Based Fuzzy AHP–TOPSIS Assessing Flood Hazards along the South-Central Coast of Vietnam. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, P.J.; Jongman, B.; Aerts, J.C.J.H.; Bates, P.D.; Botzen, W.J.W.; Diaz Loaiza, A.; Hallegatte, S.; Kind, J.M.; Kwadijk, J.; Scussolini, P.; et al. A Global Framework for Future Costs and Benefits of River-Flood Protection in Urban Areas. Nat. Clim. Change 2017, 7, 642–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, L.; Bisselink, B.; Dottori, F.; Naumann, G.; de Roo, A.; Salamon, P.; Wyser, K.; Feyen, L. Global Projections of River Flood Risk in a Warmer World. Earth’s Future 2017, 5, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, S.; Tufail, M.; Niaz, A.; Muhammad, S.; Alzahrani, H.; Tariq, A. Flood Susceptibility Assessment and Mapping Using GIS-Based Analytical Hierarchy Process and Frequency Ratio Models. Glob. Planet. Change 2025, 251, 104831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2021: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability (AR6 WGII); IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://unfccc.int/documents/196534 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Moftakhari, H.R.; AghaKouchak, A.; Sanders, B.F.; Matthew, R.A. Cumulative Hazard: The Case of Nuisance Flooding. Earth’s Future 2017, 5, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zscheischler, J.; Westra, S.; van den Hurk, B.J.J.M.; Seneviratne, S.I.; Ward, P.J.; Pitman, A.; AghaKouchak, A.; Bresch, D.N.; Leonard, M.; Wahl, T.; et al. Future Climate Risk from Compound Events. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarpanelli, A.; Mondini, A.C.; Camici, S. Effectiveness of Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 for Flood Detection Assessment in Europe. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 22, 2473–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowell, M.; Bernard, S.; Kilsedar, C.; Gianinetto, M.; Speyer, O.; Kuffer, M.; Grecchi, R.; Gliottone, I.; Melchiorri, M. Earth Observation in Support of EU Policies for Urban Climate Adaptation; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2025; ISBN 9789268261330/9789268261347. [Google Scholar]

- Giezendanner, J.; Mukherjee, R.; Purri, M.; Thomas, M.; Mauerman, M.; Islam, A.; Tellman, B. Inferring the Past: A Combined CNN-LSTM Deep Learning Framework to Fuse Satellites for Historical Inundation Mapping. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 2155–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen XinYi, S.X.; Wang DaCheng, W.D.; Mao KeBiao, M.K.; Anagnostou, E.; Hong Yang, H.Y. Inundation Extent Mapping by Synthetic Aperture Radar: A Review. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor-Escuredo, D.; Morales-Guzmán, A.; Torres-Fernández, Y.; Bauer, J.-M.; Wadhwa, A.; Castro-Correa, C.; Romanoff, L.; Lee, J.G.; Rutherford, A.; Frias-Martinez, V.; et al. Flooding through the Lens of Mobile Phone Activity. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference (GHTC 2014), San Jose, CA, USA, 10–13 October 2014; pp. 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkeki, F.N.; Bello, E.I.; Agbaje, I.G. Flood Risk Mapping and Urban Infrastructural Susceptibility Assessment Using a GIS and Analytic Hierarchical Raster Fusion Approach in the Ona River Basin, Nigeria. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 77, 103097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diep, N.T.H.; Trong Can, N.; Thi Ngoc, T.N.; Thien Nhi, D. Flood Inundation Mapping Using Sentinel-1A in An Giang Province in 2019. Vietnam J. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2020, 62, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, B.H.; Van, N.L.; Vu, H.H. Applications of satellite data for rapid inundation assessment—A case study in Thua Thien Hue province. Transp. Commun. Sci. J. 2024, 75, 1697–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, N.A.; Stéphane, G.; Xuan, N.H.; Van Tho, P. Consideration on the Use of Sentinel-1 Radar Image and GIS for Flood Mapping in the Lai Giang River Basin of Binh Dinh Province (Central Coast Vietnam). In Global Changes and Sustainable Development in Asian Emerging Market Economies Vol. 2: Proceedings of EDESUS 2019; Nguyen, A.T., Hens, L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 517–527. ISBN 978-3-030-81443-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, D.C.; Davenport, I.J.; Neal, J.C.; Schumann, G.J.-P.; Bates, P.D. Near Real-Time Flood Detection in Urban and Rural Areas Using High-Resolution Synthetic Aperture Radar Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2012, 50, 3041–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, G.J.-P.; Moller, D.K. Microwave Remote Sensing of Flood Inundation. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2015, 83–84, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, D.C.; Dance, S.L.; Cloke, H.L. Floodwater Detection in Urban Areas Using Sentinel-1 and WorldDEM Data. JARS 2021, 15, 032003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, D.V.; Bac, D.D.; My, N.Q.; Phai, V.V.; Hieu, N. Geomorphological Map for Flood Warning in the Coastal Plains of Central Vietnam. VNU J. Sci. Nat. Sci. Technol. 2002, 18. Available online: https://js.vnu.edu.vn/NST/article/view/3098 (accessed on 2 September 2025). (In Vietnamese).

- Hieu, N.; Bao, D.V. Study on the Influence of Geomorphological Characteristics on Flood Susceptibility in the Hue Plain Using Remote Sensing and GIS; Research Report; VNU University of Science, Vietnam National University: Hanoi, Vietnam, 1999. (In Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- Bac, D.K. Application of Remote Sensing and GIS in Reconstructing the Ancient Riverbeds of the Day and Nhue Rivers in Hanoi. Master’s Thesis, VNU University of Science, Vietnam National University, Hanoi, Vietnam, 2012. (In Vietnamese). [Google Scholar]

- Jago-on, K.A.B.; Kaneko, S.; Fujikura, R.; Fujiwara, A.; Imai, T.; Matsumoto, T.; Zhang, J.; Tanikawa, H.; Tanaka, K.; Lee, B. Urbanization and Subsurface Environmental Issues: An Attempt at DPSIR Model Application in Asian Cities. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 3089–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien, N.H. Urban Flood Management in Selected Cities Worldwide—Solutions and Lessons Learned. Vietnam. Constr. J. 2024, 8, 50–53. (In Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Environmental Indicators: Typology and Overview. Technical Report No. 25; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, M.F.; Saponieri, A.; Molfetta, M.G.; Damiani, L. The DPSIR Approach for Coastal Risk Assessment under Climate Change at Regional Scale: The Case of Apulian Coast (Italy). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafi, M.A.; Babel, M.S. A DPSIR Conceptual Framework for Index-Based Flood Risk Assessment: Case Study of Riverine Flood in Sirajganj, Bangladesh. J. Civ. Eng. (IEB) 2022, 50, 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, H.N.; Takara, K.; Nguyen, H.S. Flood Hazard Impact Analysis in the Downstream of Vu Gia-Thu Bon River System, Quang Nam Province, Central Vietnam. J. Jpn. Soc. Civ. Eng. Ser. B1 (Hydraul. Eng.) 2015, 71, I_157–I_162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, P.T.T.; Thao, V.T.T. Application of the DPSIR Model to Assess Surface Water Environment in Cu Khe Commune, Thanh Oai District, Hanoi City (2010–2014); Research Paper; VNU–Central Institute for Natural Resources and Environmental Studies (VNU-CRES): Hanoi, Vietnam, 2016. (In Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- Loi, D.T. Assessment of Urban Flood Vulnerability Using Integrated Multi-Parametric AHP and GIS. Int. J. Geoinform. 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanoi Statistics Office. Hanoi Statistical Yearbook 2023; Statistical Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2024. Available online: https://thongkehanoi.nso.gov.vn/storage/manager/niengiam_tk/3DnWGrd-99e4273a-b505-44d9-b12b-aa6abe1ccd48/Niengiamthongkehanoi2023/index.html (accessed on 2 September 2025). (In Vietnamese)

- Prime Minister of Vietnam. Master Plan for Hanoi Capital for the Period 2021–2030, with a Vision to 2050; Ministry of Planning and Investment: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2024. Available online: https://vanban.chinhphu.vn/?pageid=27160&docid=211993 (accessed on 2 September 2025). (In Vietnamese)

- Prime Minister of Vietnam. Adjustment of the General Master Plan for Hanoi Capital to 2045, with a Vision to 2065; Ministry of Construction: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2024. Available online: https://vanban.chinhphu.vn/?pageid=27160&docid=212179 (accessed on 2 September 2025). (In Vietnamese)

- Hanoi People’s Committee Influence of Natural Conditions on Hanoi. Available online: http://hanoi.gov.vn/dia-ly-dia-hinh/anh-huong-cua-dieu-kien-tu-nhien-den-ha-noi-42725833.htm (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Bao, D.V.; Bac, D.K.; Nga, P.T.P.; Phuong, N.T. Ancient Riverbeds in Hanoi: Reconstruction and Management Orientation. VNU J. Sci. Earth Environ. Sci. 2014, 30. Available online: https://js.vnu.edu.vn/EES/article/view/774 (accessed on 2 September 2025). (In Vietnamese).

- Hanoi General Basic Investigation Steering Committee; Dao, D.B. Atlas of Hanoi Capital (Geomorphology Map); Dalat Publishing House: Dalat, Vietnam, 1984. (In Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- European Space Agency (ESA). Sentinel-1 Mission Overview. Available online: https://www.esa.int/Applications/Observing_the_Earth/Copernicus/Sentinel-1 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Otsu, N. A Threshold Selection Method from Gray-Level Histograms. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1979, 9, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twele, A.; Cao, W.; Plank, S.; Martinis, S. Sentinel-1-Based Flood Mapping: A Fully Automated Processing Chain. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2016, 37, 2990–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congalton, R.G. A Review of Assessing the Accuracy of Classifications of Remotely Sensed Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 1991, 37, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabi, H.; Shirzadi, A.; Ghaderi, K.; Omidvar, E.; Al-Ansari, N.; Clague, J.J.; Geertsema, M.; Khosravi, K.; Amini, A.; Bahrami, S.; et al. Flood Detection and Susceptibility Mapping Using Sentinel-1 Remote Sensing Data and a Machine Learning Approach: Hybrid Intelligence of Bagging Ensemble Based on K-Nearest Neighbor Classifier. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai Sy, H.; Luu, C.; Bui, Q.D.; Ha, H.; Nguyen, D.Q. Urban Flood Risk Assessment Using Sentinel-1 on the Google Earth Engine: A Case Study in Thai Nguyen City, Vietnam. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2023, 31, 100987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahalod, N.S.S.; Rajeev, K.; Pant, P.K.; Binjola, S.; Yadav, R.L.; Meena, R.L. Spatial Assessment of Flood Vulnerability and Waterlogging Extent in Agricultural Lands Using RS-GIS and AHP Technique-a Case Study of Patan District Gujarat, India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, O.; Zeinivand, H.; Besharat, M. Flood Hazard Zoning in Yasooj Region, Iran, Using GIS and Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2016, 7, 1000–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, K.; Shahabi, H.; Pham, B.T.; Adamowski, J.; Shirzadi, A.; Pradhan, B.; Dou, J.; Ly, H.-B.; Gróf, G.; Ho, H.L.; et al. A Comparative Assessment of Flood Susceptibility Modeling Using Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Analysis and Machine Learning Methods. J. Hydrol. 2019, 573, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendana, M.; Mohd Razi Idris, W.; Abdul Rahim, S.; Abdo, H.G.; Almohamad, H.; Abdullah Al Dughairi, A. Flood Risk and Shelter Suitability Mapping Using Geospatial Technique for Sustainable Urban Flood Management: A Case Study in Palembang City, South Sumatera, Indonesia. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2025, 9, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.N.; Le Anh, H.; Schneider, P. A DPSIR Assessment on Ecosystem Services Challenges in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam: Coping with the Impacts of Sand Mining. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, K.; Matin, M.A.; Meyer, F.J. Operational Flood Mapping Using Multi-Temporal Sentinel-1 SAR Images: A Case Study from Bangladesh. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Pham, T.; Bui, D.X.; Do, T.A.T.; Do, A.N.T. Assessing Flood Susceptibility in Hanoi Using Machine Learning and Remote Sensing: Implications for Urban Health and Resilience. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 10149–10170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, K.H.; Menenti, M.; Jia, L. Surface Water Mapping and Flood Monitoring in the Mekong Delta Using Sentinel-1 SAR Time Series and Otsu Threshold. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanoi Statistics Office. Hanoi Statistical Yearbook 2010; Statistical Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2011. (In Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- Hanoi Sewerage and Drainage One Member Limited Company Current Status of the Inner-City Drainage System of Hanoi. 2022. Available online: https://vnexpress.net/hien-trang-he-thong-thoat-nuoc-noi-thanh-ha-noi-4471199.html (accessed on 12 September 2025). (In Vietnamese).

- Hanoi Statistics Office. Hanoi Statistical Yearbook 2014; Statistical Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2015. (In Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- Ly, N.N. Report on Hanoi Lakes 2015; Vietnam Women’s Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2015. (In Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- Westra, S.; Fowler, H.J.; Evans, J.P.; Alexander, L.V.; Berg, P.; Johnson, F.; Kendon, E.J.; Lenderink, G.; Roberts, N.M. Future Changes to the Intensity and Frequency of Short-Duration Extreme Rainfall. Rev. Geophys. 2014, 52, 522–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.S.; Lu, X.X. Sustainable Urban Stormwater Management in the Tropics: An Evaluation of Singapore’s ABC Waters Program. J. Hydrol. 2016, 538, 842–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikhi, F.; Li, C.; Ji, Q.; Zhou, X. Review of Sponge City Implementation in China: Performance and Policy. Water Sci. Technol. 2023, 88, 2499–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Li, N.; Wang, J.; Wang, S. Comprehensive Performance Assessment for Sponge City Construction: A Case Study. Water 2023, 15, 4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prime Minister of Vietnam Decision No. 725/QD-TTg: Approval of the Drainage Master Plan for Hanoi Capital to 2030, with a Vision to 2050. 2013. Available online: http://vanban.chinhphu.vn/default.aspx?pageid=27160&docid=167363 (accessed on 14 September 2025). (In Vietnamese).

| No. | Types of Data | Formats | Duration | Source/References | Purposes of Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sentinel-1 SAR (C-band, IW) | Raster (10 m) | 2015–2024 (July–October) | ESA/Copernicus Hub | Flood mapping, constructing maps of flood frequency |

| 2 | ALOS AVNIR-2 | Raster (30 m) | 2010, 2020 | JAXA | Analysis of urban fluctuation |

| 3 | VLULC Vietnam Land Use Land Cover | Vector/Raster | 2010–2020 | Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, VLULC update | Map of land use, urban expansion |

| 4 | DEM (SRTM v3) | Raster (30 m) | 2011 | USGS | Topographic analysis, geomorphological indices |

| 5 | Geomorphological map of Hanoi | Vector (1:320,000) | Original 2015; Reclassified 2024 | Dao Dinh Bac (1984) [76]; Authors (reclassification and GIS update 2024) | Classification of 9 geomorphological units |

| 6 | Historical flood points | Vector (GPS points) | 2012–2022 | Reports of authority, press, and field surveys | Flood map validation |

| 7 | Population (Statistical yearbook) | Data tables | 2013–2021 | Hanoi Statistics Office | Assessment of “Drivers” in DPSIR (non-GIS) |

| 8 | Drainage systems | Documents | 2018–2022 | Hanoi Sewerage and Drainage Company Limited | Evaluation of “Pressures” in DPSIR (non-GIS) |

| Flood Frequency Level | Area (ha) | Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Very low | 225,626.2 | 67 |

| Low | 47,631.2 | 14 |

| Medium | 24,061.7 | 7 |

| High | 30,347.2 | 9 |

| Very high | 7435.1 | 2 |

| Urban Types | Area (ha) | Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Old urban area | 37,122.1 | 66 |

| New urban area | 19,421.6 | 34 |

| Inundated Area | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Denudation–erosion origin | 11,336.1 | 9.5% |

| Fluvial-origin surfaces | 4595.2 | 3.8% |

| River terrace | 7554.0 | 6.3% |

| Inner-dike floodplains | 43,638.6 | 36.4% |

| Outer-dike floodplains | 19,950.7 | 16.7% |

| Paleochannels | 4534.4 | 3.8% |

| Mixed surfaces | 2145.1 | 1.8% |

| Karst | 7250.1 | 6.1% |

| Fluvio-marine plain | 18,727.5 | 15.6% |

| Urban Types | Inundated Area (ha) | Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| New urban area | 3500.12 | 73 |

| Old urban area | 1279.0 | 27 |

| Risk Level | Denudation Origin | Fluvial-origin Surfaces | River Terrace | Inner-Dike Floodplains | Outer-Dike Floodplains | Paleochannels | Mixed Surfaces | Karst | Fluvio-Marine Plain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very low | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Low | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Medium | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| High | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Very high | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hieu, N.M.; Trang, T.T.K.; Bac, D.K.; Oanh, V.T.K.; Nga, P.T.P.; Tuan, T.V.; Phin, P.T.; Liem, P.S.; Thu, D.T.T.; Hung, V.K. An Integrated Approach to Assessing the Impacts of Urbanization on Urban Flood Hazards in Hanoi, Vietnam. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10763. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310763

Hieu NM, Trang TTK, Bac DK, Oanh VTK, Nga PTP, Tuan TV, Phin PT, Liem PS, Thu DTT, Hung VK. An Integrated Approach to Assessing the Impacts of Urbanization on Urban Flood Hazards in Hanoi, Vietnam. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10763. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310763

Chicago/Turabian StyleHieu, Nguyen Minh, Trinh Thi Kieu Trang, Dang Kinh Bac, Vu Thi Kieu Oanh, Pham Thi Phuong Nga, Tran Van Tuan, Pham Thi Phin, Pham Sy Liem, Do Thi Tai Thu, and Vu Khac Hung. 2025. "An Integrated Approach to Assessing the Impacts of Urbanization on Urban Flood Hazards in Hanoi, Vietnam" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10763. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310763

APA StyleHieu, N. M., Trang, T. T. K., Bac, D. K., Oanh, V. T. K., Nga, P. T. P., Tuan, T. V., Phin, P. T., Liem, P. S., Thu, D. T. T., & Hung, V. K. (2025). An Integrated Approach to Assessing the Impacts of Urbanization on Urban Flood Hazards in Hanoi, Vietnam. Sustainability, 17(23), 10763. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310763