1. Introduction

Global climate change has become a reality, and it is intensifying with every passing year, with more frequent heatwaves and flooding occurring in many parts of the world. The Middle East, Asia, and Southern Europe are the most affected regions. The increase in regional temperatures in the recent past has significantly increased the demand for cooling, which constitutes a significant share of energy consumption in buildings and industry. Conventional cooling technology based on vapour compression cycles demands a lot of energy. Moreover, these cycles contribute substantially to greenhouse gas emissions, both through high electricity consumption and synthetic refrigerants [

1].

These challenges can be addressed by using absorption cooling technologies. This technology requires heat as an input, which is readily available in such hot climates or through waste heat recovery technologies (e.g., waste heat to cold) [

2]. Recently, lithium bromide–water (LiBr–H

2O) based vapour absorption refrigeration systems have regained importance, as they can provide a low-emission, sustainable, and energy-efficient cooling system for hot regions by utilising thermal energy. Subsequently, they are well-suited for integration with solar collectors or industrial waste heat recovery systems [

3,

4]. For instance, Wang et al. conducted a thermodynamic evaluation of a combined cooling and power system in which an ammonia–water absorption refrigeration cycle is driven by the waste heat from the Kalina power generation cycle [

5]. Their results showed that the thermal efficiency of the proposed system could reach 24.62%.

LiBr–H

2O systems are among the most used absorption systems due to their safety and environmental compatibility [

4,

6]. The system usually operates under vacuum conditions. It essentially consists of a generator, an absorber, a condenser, and an evaporator. Since water serves as the refrigerant in the cycle, it is only suitable for cooling applications where the evaporator temperature remains above 0 °C [

7].

The performance of the LiBr–H

2O vapour absorption cycle is highly sensitive to operating parameters [

3]. In single-effect systems, the coefficient of performance (COP) generally ranges between 0.6 and 0.8, depending on the heat source temperature and operating conditions. The literature review indicates the possibility of the performance improvement of these systems through thermodynamic optimisation, heat recovery techniques, and integration with renewable sources [

8].

Srikhirin et al. conducted a parametric study on operating temperatures. They concluded that system efficiency can be significantly improved if the generator operates at higher temperatures and the absorber at lower temperatures [

4]. Marashli et al. developed a MATLAB/Simulink model for a single-effect system in Ma’an, Jordan. Their findings revealed that the generator temperature is the most critical factor influencing the COP of the cycle [

6]. Their study reported a maximum COP of 0.74 at a generator temperature of 110 °C while operating safely away from the LiBr crystallisation line. Similarly, Patel et al. performed an energy analysis of a 140 kW system [

9]. They concluded that COP increases with generator and evaporator temperatures but decreases with rising condenser temperature. Similar findings were observed in an exergy analysis of a 10 TR (35 kW) chiller by Ochoa Villa et al. [

10]. They found that the major irreversibilities occur in the generator (32%), the cooling tower (34%), and the absorber (16%), thereby emphasising key areas for potential optimisation.

Kaneesamkandi et al. recently conducted a detailed analysis of a solar-powered VARS in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia [

11]. They implemented various condenser cooling methods, such as air, water, evaporative, and hybrid systems. Their findings indicated that the water-cooled condensers yield the highest COP. On the other hand, the hybrid cooling method offers a compromise between performance and the cost involved. This is achieved by intelligently switching between air and evaporative cooling based on ambient temperature. Maintaining an appropriate temperature for the condenser is vital because high condenser temperatures not only reduce COP but also increase the risk of LiBr crystallisation and hence limit the operational range of the system [

6]. Kaushik et al. performed energy and exergy analysis of single-effect and series flow double-effect LiBr–H

2O refrigeration systems. They found the COP of the single-effect system in the range of 0.6–0.75, whereas the double-effect system produced a COP between 1 and 1.28 [

8].

Prieto et al. studied the feasibility of the single-effect LiBr–H

2O absorption heat pump cycle to produce combined heating and cooling [

12]. The research demonstrates that integrating condensation heat recovery into a single-effect LiBr–H

2O system allows for simultaneous cooling and heating. This resulted in an improved overall thermal performance with a COP value of 1.65. Moreover, integrating a solution heat exchanger between the generator and the absorber is a standard, highly effective method. Marashli et al. demonstrated that increasing the effectiveness of this heat exchanger from 0.6 to 0.9 improved the system COP by 8.5% [

6]. This pre-heating of the weak solution entering the generator significantly reduces the external heat required, leading to substantial energy savings.

Exergy-based investigations of absorption refrigeration cycles consistently show that the absorber and generator are the dominant sources of irreversibility. For example, Aphornratana and Eames [

13] demonstrated that improving the solution heat exchanger effectiveness and the evaporator can markedly reduce exergy losses. Talbi and Agnew [

14] quantified this, reporting that the absorber alone accounts for ~60% of total exergy destruction in a single-effect absorption refrigeration cycle with LiBr–H

2O. Later studies, e.g., [

8,

15], confirmed that optimal generator temperatures derived from exergy criteria are lower than those predicted by energy analysis, highlighting the absorber’s strong influence on overall system efficiency. Comparative analyses by Bellos et al. [

16] and Gogoi and Konwar [

17] found that while LiCl–H

2O exhibits marginally higher exergy efficiency than LiBr–H

2O, its crystallisation tendency limits its usability. Lake et al. [

18] further validated that the absorber, generator, and condenser contribute the largest exergy destructions (~30%, 31%, and 28%, respectively), yielding an overall exergetic efficiency of nearly 16% at a COP of 0.65. Castro and Oliet [

19] conducted an exergy-focused evaluation of an air-cooled solar-driven absorption cycle for a chiller, which revealed exergy efficiencies ranging between 0.2 and 0.6, and demonstrated that the Carrol–H

2O working pair provides 6.3% higher exergy efficiency compared with conventional LiBr–H

2O, albeit with a reduced cooling capacity. Overall, the literature establishes that exergy analysis provides clearer insight into component-level losses and remains essential for optimising absorption systems and selecting working pairs.

Thermodynamic modelling is essential for understanding the energy transformations within vapour absorption refrigeration systems (VARS) and for identifying their operational limitations. Although many studies have analysed single-effect LiBr–H2O systems, the literature shows very limited investigation of cycle performance under warm-climate conditions, particularly when minimum cycle temperatures reach 40–45 °C, as commonly encountered in hot regions. The present study addresses this gap by examining the influence of key operational parameters on a LiBr–H2O VARS specifically under these elevated temperature conditions. A further novel aspect of this work is the evaluation of dual heat-recovery configurations integrated into a standard single-effect VARS, an area that, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, has received little attention in previous research. First, the thermodynamic behaviour of the LiBr–H2O working pair is analysed over a wide range of pressures and temperatures to establish fundamental operational limits, including the minimum generator temperature and the allowable solution concentration. Then, a detailed Aspen Plus–based performance assessment is conducted over varying generator and condenser temperatures, evaporator pressures, and solution heat-exchanger effectiveness. In addition, the exergy performance of the system is evaluated by quantifying the irreversibilities across all the major components of the cycle, including the generator, evaporator, condenser, absorber, heat-recovery units, solution pump, and expansion valves, to identify the dominant sources of exergy destruction. Together, these contributions provide new insight into LiBr–H2O system design for warm climates and demonstrate the performance enhancement achievable through integrated heat-recovery strategies.

2. Thermodynamic Behaviour of LiBr–H2O Solution in VARS

The LiBr–H

2O and NH

3–H

2O are the most used working pairs in absorption cooling systems [

12,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. The current study considers water and LiBr as a working pair to operate the vapour absorption refrigeration cycle, with water being the refrigerant and LiBr being the absorbent. This section highlights the thermodynamic properties of this working pair under various pressure and temperature conditions. Both LiBr and water are non-toxic, non-flammable, and ozone-friendly. Water, being the refrigerant, has zero ozone depletion potential (ODP) and zero global warming potential (GWP). LiBr is highly hygroscopic, making it an excellent absorbent. Moreover, LiBr solution exerts negligible vapour pressure compared to water, so water vapour can be absorbed effectively without contamination. LiBr–water solution has a large boiling point elevation (BPE), enabling the generator in a LiBr–H

2O VARS to operate at moderate temperatures (80–120 °C) using a low-grade heat source, e.g., hot water, waste heat, or solar energy.

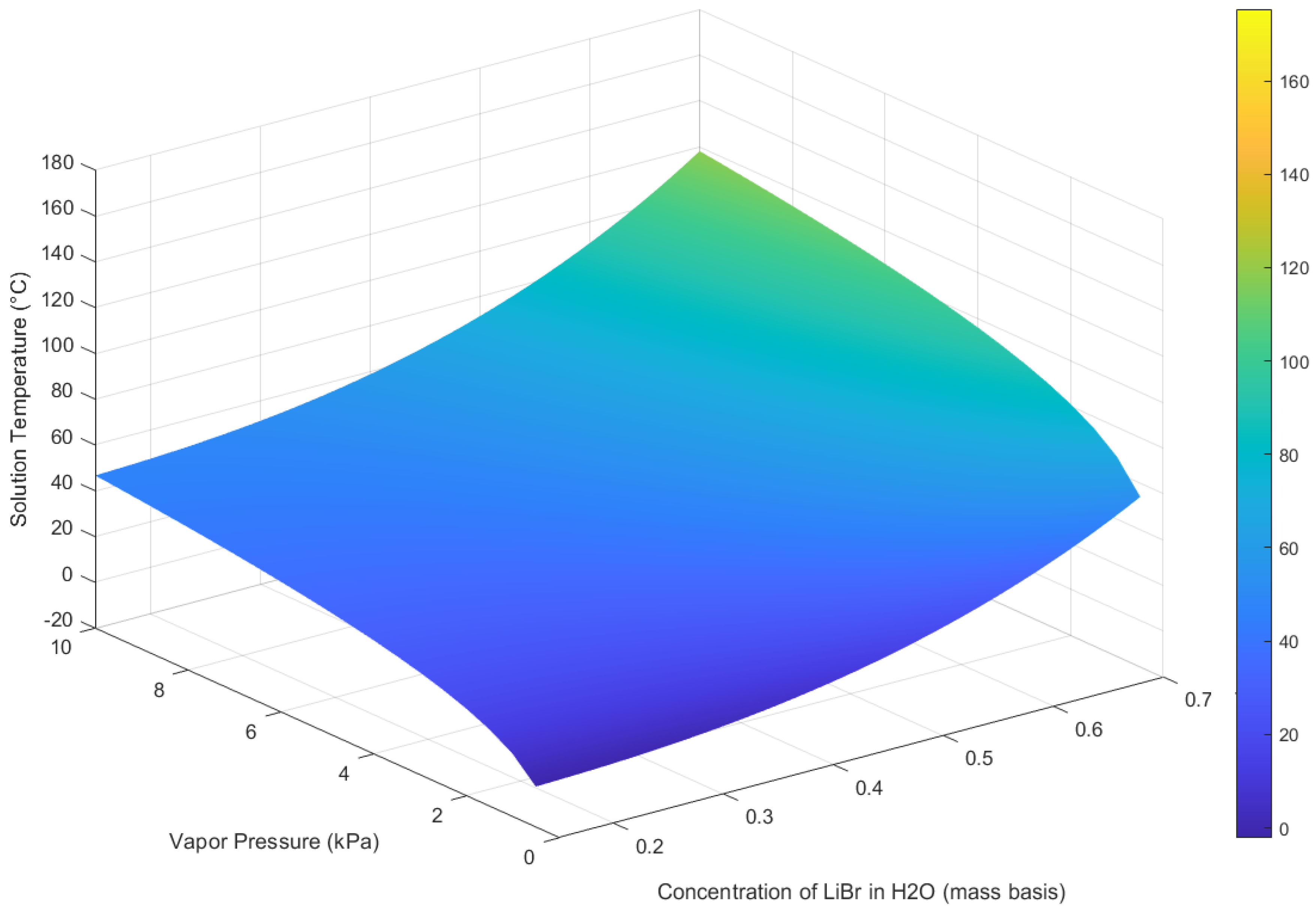

Figure 1 illustrates the three-dimensional pressure–temperature–concentration (P–T–

x) equilibrium surface of the LiBr–H

2O working pair. The ELECNRTL model in Aspen Plus (V11) is used to generate phase equilibrium data for LiBr–H

2O. This model accurately captures the non-ideal behaviour of the electrolyte solution and predicts phase equilibria under varying operating conditions. Aspen Plus models the LiBr–H

2O solution by dissociating solid lithium bromide in water according to the equilibrium reaction LiBr(s) + H

2O(l) ↔ Li

+(aq) + Br

−(aq) + H

+(aq) + OH

−(aq), allowing the ENRTL property method to predict the resulting ionic interactions and solution behaviour. The reaction shows that LiBr forms ions in water, which lowers water activity and reduces the vapour pressure. This explains the boiling-point elevation of the solution and why higher generator temperatures are needed to achieve desorption against a given condenser pressure, making LiBr–H

2O effective for absorption refrigeration cycles.

The surface in

Figure 1 highlights the interdependence of key thermodynamic properties that govern the performance of vapour absorption refrigeration systems. As vapour pressure and temperature are directly linked to the solution’s boiling point, the surface provides insight into how concentration influences system behaviour.

At lower concentrations (left side of the graph): The surface appears relatively flat, indicating that increases in LiBr concentration result in only gradual rises in solution temperature.

At higher concentrations (right side of the graph): The surface becomes much steeper, meaning even a small increase in LiBr concentration requires a substantial rise in solution temperature to maintain the same vapour pressure.

This behaviour shows that higher LiBr concentrations significantly enhance the boiling point elevation (BPE), enabling the generator to operate effectively at moderate temperatures (80–120 °C).

Prior to a more detailed analysis of the LiBr–H

2O vapour absorption refrigeration system (VARS), the thermodynamic model based on the ENRTL property method in Aspen Plus is validated against data recently reported in the literature by Yves et al. [

25].

Table 1 provides a side-by-side comparison between Aspen-predicted mass concentrations of the LiBr–H

2O solution, and the reference values compiled by Yves et al. over a range of operating pressures (0.5–9.5 kPa) and temperatures (40–100 °C) relevant to the current study. To quantitatively assess the accuracy of the model, the percentage deviation between the two datasets is presented in

Table 1. The results indicate excellent agreement, with most deviations lying within ±3%, confirming that the ENRTL model reliably captures the thermodynamic behaviour of the LiBr–H

2O solution.

3. Description of VARS Configuration

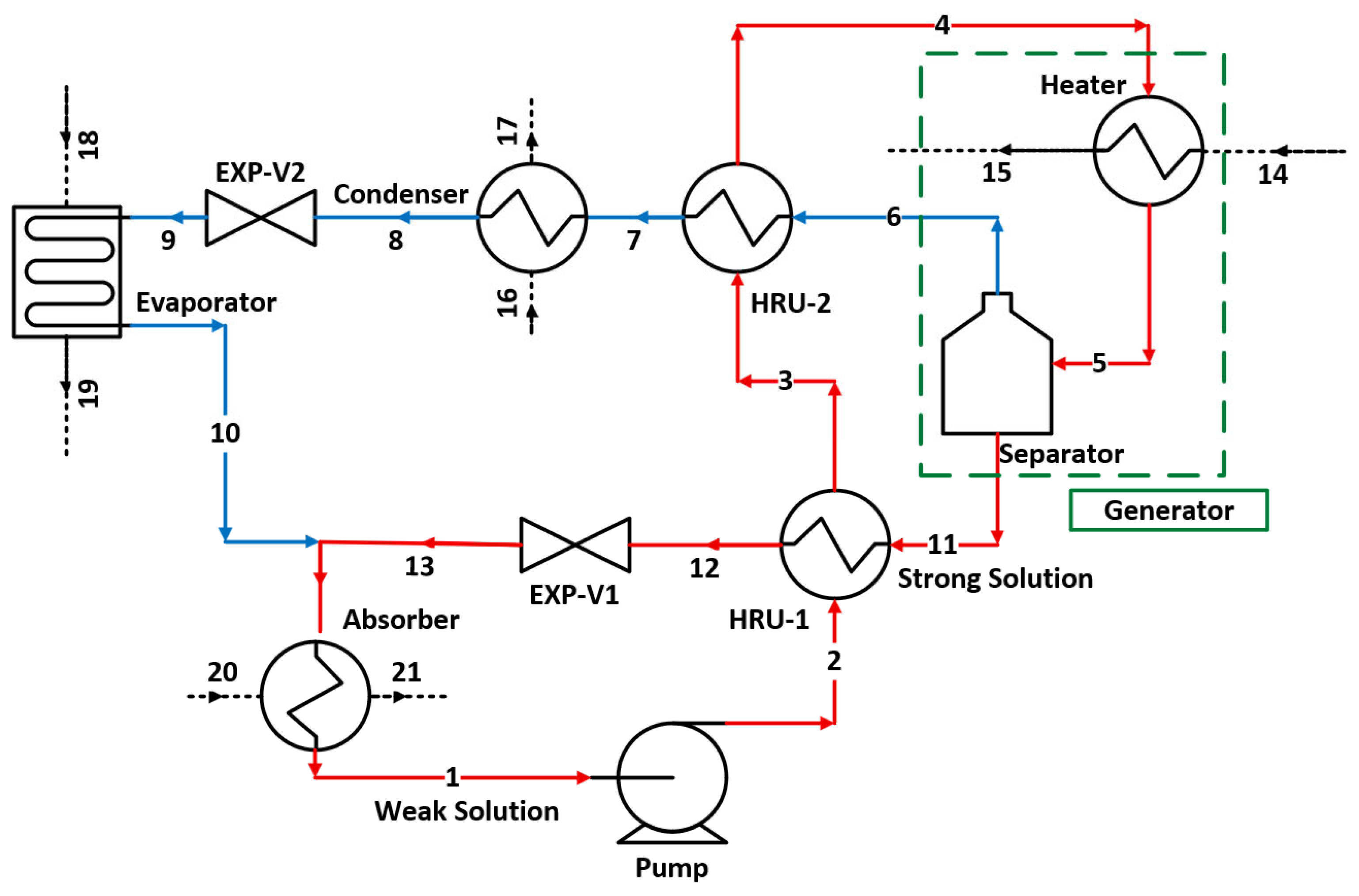

The single-effect vapour absorption cycle is considered in the current study, and its layout is shown in

Figure 2. The cycle is essentially composed of two parts, one with pure refrigerant (water), shown with blue lines connecting state points six, seven, eight, nine, and ten. This part contains a condenser, an expansion valve, and an evaporator, and their functions are identical to the corresponding vapour compression cycle. The second part of the cycle carries LiBr–H

2O solution. This part of the cycle mimics the function of a compressor in a vapour compression cycle.

The weak solution of LiBr–H2O is pressurized to a desired level by a pump from state 1 to state 2. To reduce the amount of heating needed to operate the cycle, which ultimately improves the overall thermal efficiency of the cycle, there are two heat recovery units (HRUs) installed. HRU-1 recovers the heat from the hot, strong solution (i.e., concentrated) of LiBr–H2O coming from the separator (state 11). Stream 2, coming out of HRU-1 (state 3), enters HRU-2, where it exchanges heat with the hot water vapour leaving the Separator before entering the generator. The generator is a component that includes a heater and a separator. The weak solution is heated to a desired temperature in the heater, and then it enters the separator, where the water vapour is removed from the solution, increasing the concentration of LiBr in the solution; thus, it is called a strong solution. The strong solution leaves the separator and exchanges heat with the weak solution in HRU-1; it then passes through a throttling valve (EXP-V1) before absorbing the low-pressure water vapours from the evaporator.

Water vapours leaving the separator at state 6 exchange heat in HRU-2 with the weak solution stream (state 3 to state 4), then it rejects heat in the condenser before it passes through the throttling valve (EXP-V2). The water leaving EXP-V2 enters the evaporator, where it receives heat (the cooling load) and exits as saturated low-pressure vapours of water, and the cycle continues.

4. Simulation Environment and Design Parameters

We simulated a vapour absorption refrigeration cycle in Aspen Plus (V11) under steady-state conditions. The simulation focuses on a LiBr–H

2O solution, which is at equilibrium in both the generator and the absorber. The condenser and the evaporator are operating at saturation conditions. We assessed the cycle’s performance by varying the temperatures of the generator, condenser, absorber, and evaporator. Key design parameters are detailed in

Table 2.

The study specifically evaluated the cycle’s performance with evaporator temperatures ranging from 4 °C to 9 °C. This range corresponds to a saturation pressure for water of approximately 0.8 kPa to 1.2 kPa, indicating that the absorber will also operate within this pressure range.

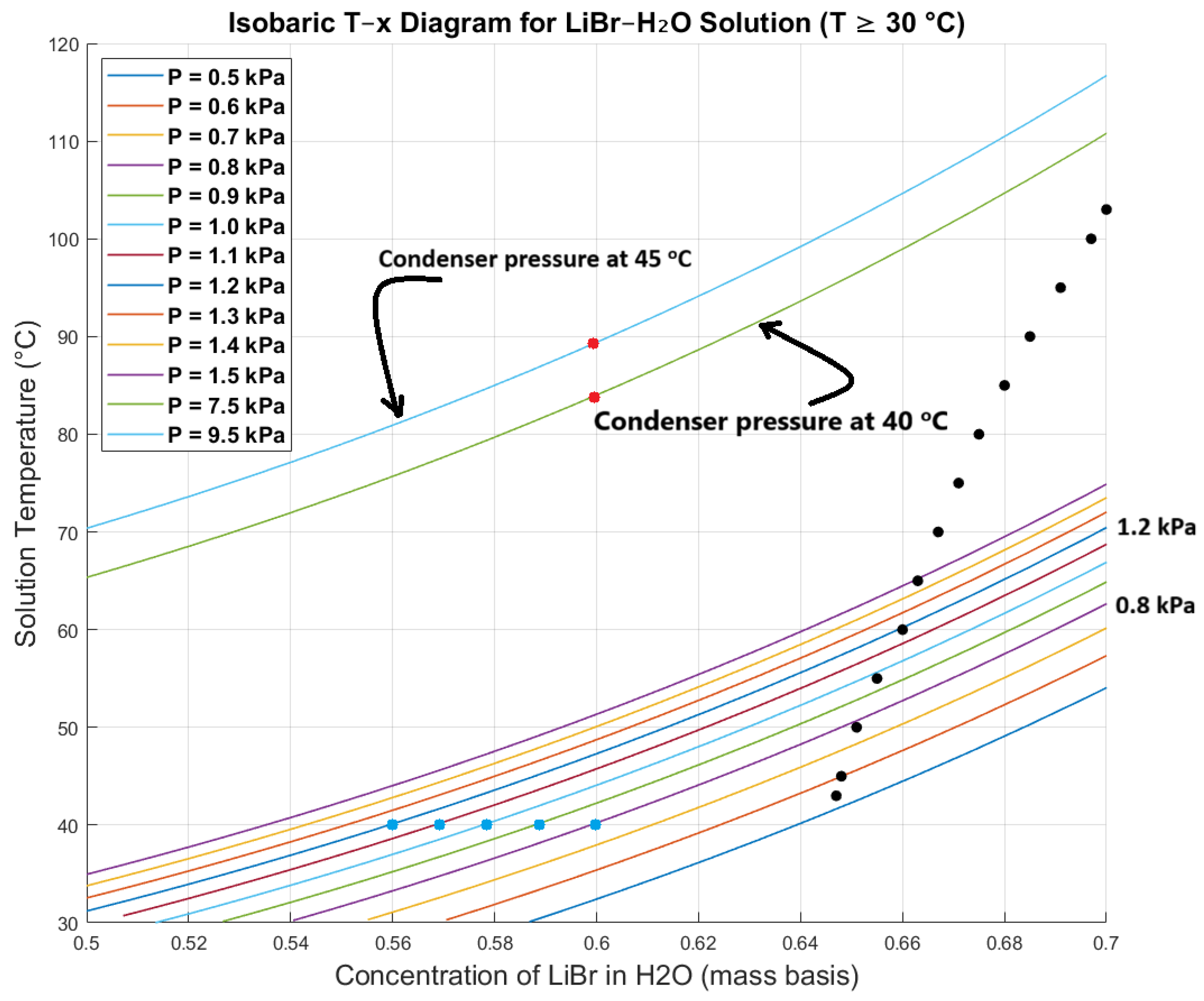

Figure 3 illustrates the equilibrium relationship among temperature, concentration, and pressure for the LiBr–H

2O solution. As shown on the temperature–concentration axes, for a fixed concentration, an increase in solution temperature requires a higher pressure to maintain equilibrium.

The blue dots in

Figure 3 represent the saturation conditions of the LiBr–H

2O solution at an absorber temperature of 40 °C for pressures between 0.8 kPa and 1.2 kPa. This information is crucial for determining the weak solution concentration and ensuring that no vapour forms at the pump inlet.

Figure 3 also provides important insights into the minimum operating temperature of the generator for a given weak solution concentration and condenser pressure. For example, if the weak solution concentration is 0.6, the generator must operate above approximately 83 °C and 89 °C for condenser pressures of 7.5 kPa and 9.5 kPa, respectively (refer to the red dots in

Figure 3). Water vapour (refrigerant vapour) will not be produced if the generator temperature falls below this minimum threshold. This minimum generator temperature corresponds to the point at which the water vapour pressure of the LiBr–H

2O solution becomes equal to the condenser pressure. Below this temperature, the solution’s vapour pressure remains lower than the imposed condenser pressure, so desorption cannot occur and no refrigerant vapour is generated.

5. Energy and Efficiency Assessment of LiBr–H2O Vapour Absorption System

This section presents the fundamental equations for a steady-state energy analysis of a lithium bromide (LiBr) vapour absorption refrigeration system (VARS) based on the provided configuration shown in

Figure 2. The model is based on the conservation laws of mass, energy, and exergy. The model assumes that

The system operates under steady-state conditions;

Changes in kinetic and potential energy are negligible;

The pump, absorber, condenser, evaporator, generator, and heat recovery units (HRUs) are adiabatic, and heat transfer only occurs where it is intended.

The energy analysis is based on the first law of thermodynamics. For each component, the energy balance equation is derived by applying the principle of conservation of energy.

The refrigerant and solution mass flow rates in the cycle can be represented as follows:

where

,

, and

represent mass flow rates of the refrigerant, the weak solution, and the strong solution, respectively. It is to be noted that by fixing either the mass flow rate of the refrigerant or weak or strong solution, one can easily obtain the mass flow rate of the other remaining mass flow rates using the mass balance applied either at the generator or the absorber. For example, with known

, the overall and constituent mass balance at the absorber leads to the following set of equations:

where

is essentially zero as it represents the concentration of LiBr in the solution. Therefore, with known concentrations of weak and strong solutions, one can obtain mass flow rates of weak and strong solutions.

The work needed to pressurise the system is given by

where

and

are the enthalpies at the inlet and exit of the pump, respectively.

The amount of heat provided to the weak solution in the generator to attain the required temperature can be obtained using energy balance and is given by:

where

is the enthalpy of the weak solution entering the generator.

is the enthalpy of the vapour of the refrigerant produced because of the heat provided in the generator and exiting the separator.

is the enthalpy of the strong solution leaving the separator.

The vapours of refrigerant produced in the generator must reject heat during the condensation process, and so they first exchange heat in the heat recovery unit HRU-2, then reject heat in the condenser. The heat rejected in the condenser is given by

where

and

are the enthalpies of the refrigerant at the inlet and exit of the condenser, respectively.

The expansion valves EXP-V1 and EXP-2 are isenthalpic, therefore

The solution heat exchangers (HRU-1 and HRU-2) recover heat from within the cycle to improve the overall energy efficiency of the cycle by reducing the heat input needed. The recovery units are considered operating at specified effectiveness, which allows us to calculate the exit temperatures of the hot streams from HRU-1 and HRU-2, and are given by

The enthalpies of the cold streams leaving the heat recovery units and the heat recovered can be obtained using an energy balance.

The total heat absorbed by the refrigerant in the evaporator (

) is obtained by

where

and

are the enthalpies of the refrigerant at the inlet and exit of the evaporator, respectively.

Finally, the energy performance of the cycle is obtained by taking the ratio of the cooling produced (

) to the net energy input to the cycle, i.e.,

where

represents the coefficient of performance of the cycle.

The circulation ratio (CR) is a compact metric that captures how much “extra” solution mass must be heated, pumped, and handled per unit of refrigerant produced. It is defined as [

26,

27,

28]:

A greater concentration difference between the strong and weak solutions means more refrigerant vapour per unit weak solution, which leads to a lower CR. Conversely, small concentration differences require more solution flow and thus higher CR [

29]. Moreover, large CR means a lot of solution is moving, implying larger pumps, more piping, more heat needed to reheat the solution, and thus higher capital and operating costs [

30].

7. Results and Discussion

This section discusses the performance of the single-effect LiBr–H

2O vapour absorption refrigeration system shown in

Figure 2. The system is assessed for a range of parameters, such as generator temperature, heat exchanger effectiveness, condenser temperature, and solution concentrations. The energy assessment is carried out using the mathematical model presented in

Section 5, while the exergy assessment follows the methodology described in

Section 6.

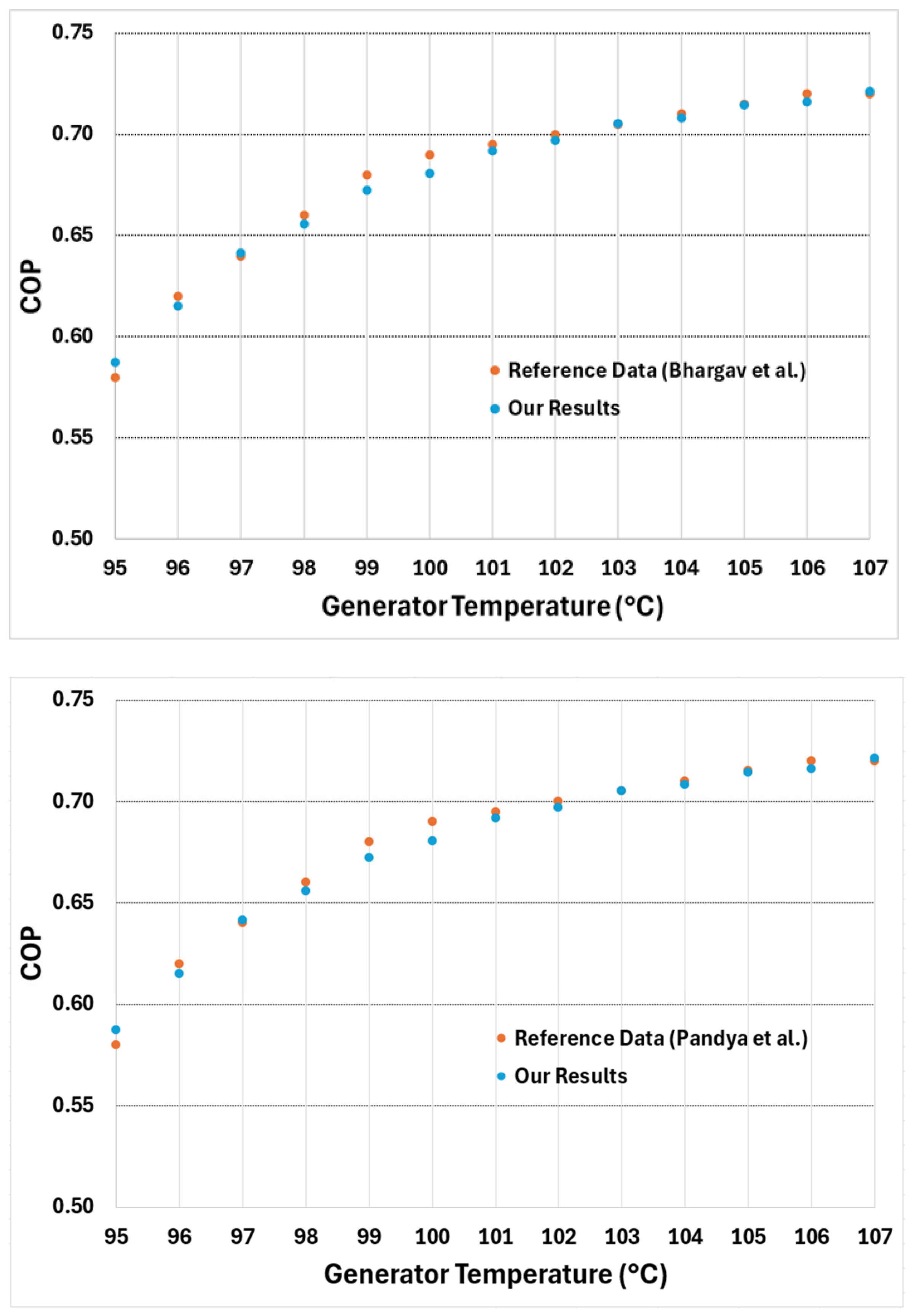

We first assess the energy analysis model presented in

Section 5 by comparing the cycle’s coefficient of performance (COP) calculated from the current simulation data with that reported by Pandya et al. [

31] for a single-effect LiBr–H

2O vapour absorption cycle. It is important to note that the validation is performed by applying the same conditions as those reported in [

31], i.e., an evaporator temperature of 5 °C, absorber and condenser temperatures of 40 °C, and a solution heat exchanger effectiveness of 0.75.

Figure 4 presents the COP plotted for a generator temperature range of 95 to 107 °C along with the COP obtained from reference [

31]. Our results demonstrate excellent agreement (with an average deviation of less than 0.6% compared to the reference) with the reference, matching both the calculated COP values and the overall trend.

7.1. Generator Temperature and Its Effect on Cycle Metrics

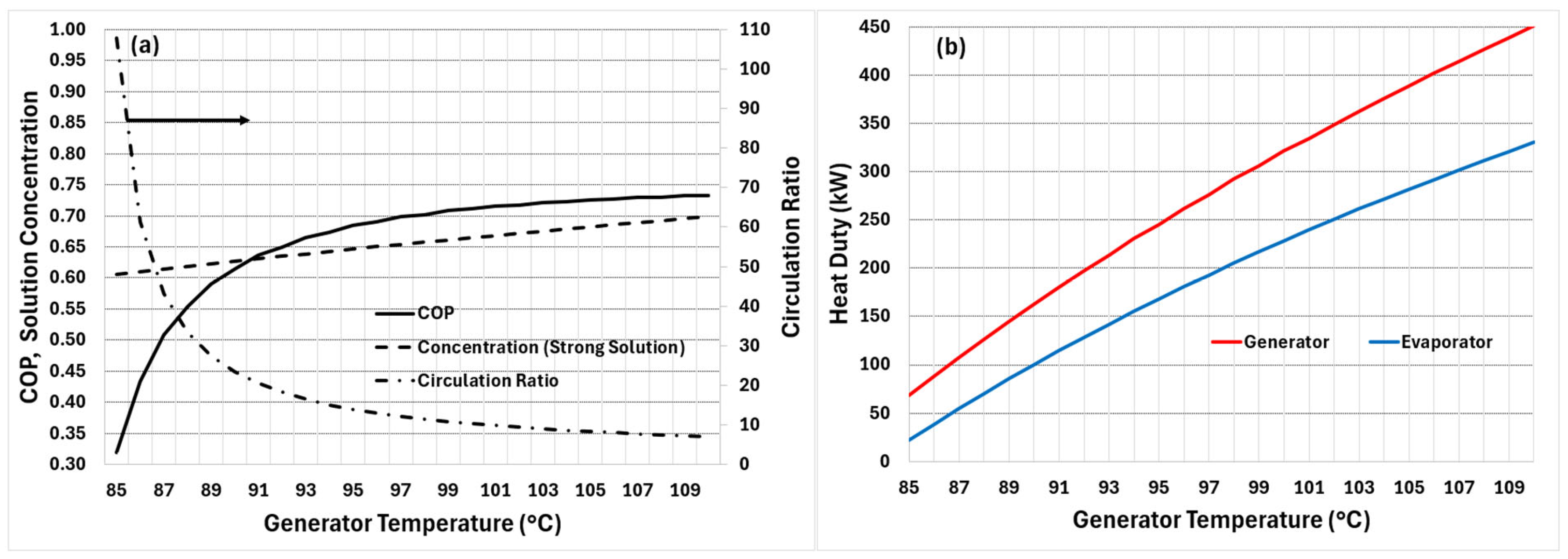

Figure 5a presents the effect of generator temperature on the COP of the cycle, variation in the strong solution concentration, and the circulation ratio, while

Figure 5b presents the corresponding heat duties of the generator and evaporator. These results were obtained with a heat exchanger effectiveness of 0.5 (for both HRU-1 and HRU-2 in

Figure 2). The results are obtained for a fixed evaporator pressure of 0.8 kPa (corresponding to evaporator temperature of 4 °C) and condenser/absorber temperatures of 40 °C. The weak solution concentration is fixed at 0.6, which corresponds to the minimum allowable at an absorber temperature of 40 °C.

It is observed that, as the generator temperature rises, the cycle’s COP increases steadily but non-linearly. The concentration of the strong solution also rises slightly, reflecting the increased desorption rate of water vapour from the LiBr solution at higher generator temperatures. In contrast, the circulation ratio decreases sharply with increasing generator temperature. As the generator temperature rises, the solution in the generator becomes more strongly concentrated (more refrigerant desorbed per kg solution), so the circulation ratio falls. At some point, the strong-solution concentration (and the thermodynamic driving forces) approaches a range where further increases in generator temperature yield only small additional increases in vapour fraction from the solution; this explains the flattening of the circulation-ratio curve at nearly 100 °C. This also explains why the COP’s rate of increase falls above about 100 °C and why the difference between heat duties increases, as seen from

Figure 5b.

Figure 5b presents the effect of the solution temperature in the Generator on its heat duty and the cooling capacity of the Evaporator. The heat input required for generator operation increases almost linearly with the rise in operating temperature. The cooling capacity of the evaporator follows a similar pattern; however, its slope is slightly smaller, causing the gap between the two curves to widen as the generator temperature increases.

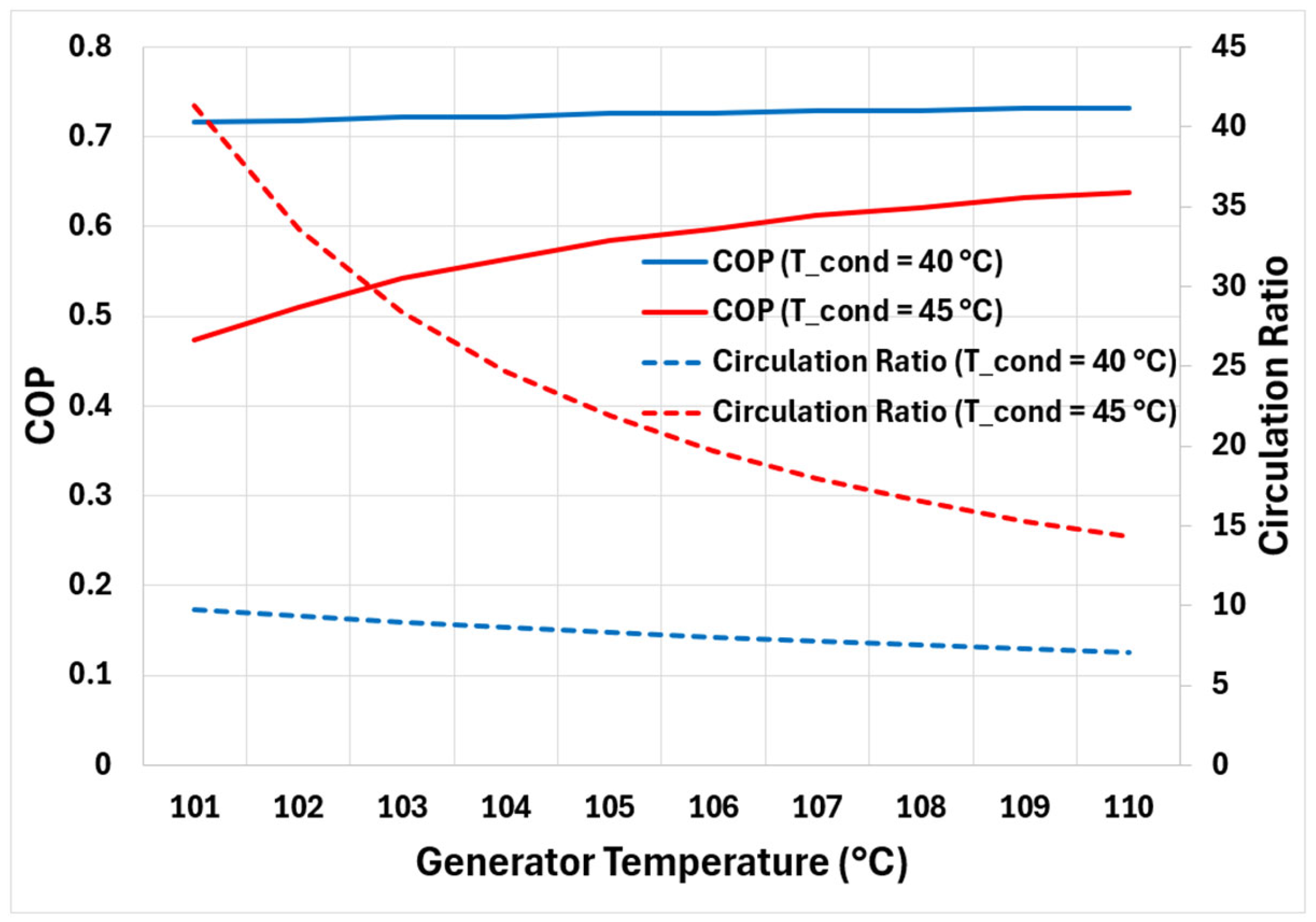

7.2. Condenser/Absorber Temperature and Its Effect on Cycle Performance

Figure 6 presents the cycle’s COP and circulation ratio for a fixed evaporator pressure of 0.8 kPa (corresponding to evaporator temperature of 4 °C) and condenser/absorber temperatures of 40 °C and 45 °C. The condenser and absorber are assumed to be operating at the same temperature. It is to be noted that the minimum generator temperature required to produce and separate refrigerant vapours from the solution is restricted by the operating pressure of the condenser/absorber (refer to

Figure 3). Therefore, the results in

Figure 6 are shown for generator temperatures above 101 °C. Moreover, to operate the evaporator at 0.8 kPa, the lowest allowable weak solution concentration is used, i.e., 0.63. This is performed to prevent vapours at the pump inlet.

Like observations made in

Section 7.1 for condenser/absorber temperature of 40 °C, the COP curve rises non-linearly but eventually flattens with rising generator temperature for condenser/absorber temperature of 45 °C. Similar behaviour is observed for the circulation ratio. However, the overall performance of the cycle seems to be significantly reduced when the cycle’s minimum temperature (condenser/absorber temperature) is increased. This is due to increased minimum allowable concentration of the weak solution and higher generator temperatures needed to operate the cycle, which ultimately require more energy input (

) with comparatively less refrigerant vapour production affecting the cooling capacity (

).

7.3. Evaporator Pressure and Its Effect on Cycle Performance

Figure 7 details the effects of evaporator pressure on the cycle’s COP, circulation ratio, and solution concentrations. The results were obtained with the generator and condenser/absorber temperatures held constant at 100 °C and 40 °C, respectively.

As shown in

Figure 7a, as the evaporator pressure increases from 0.8 to 1.2 kPa, the COP improves from 0.71 to 0.77. This enhancement is primarily due to a sharp decrease in the circulation ratio, which results from a greater concentration difference between the strong and weak solutions. The weak solution concentration was fixed at the minimum allowable level to prevent vapour formation at the pump inlet, a constraint determined by the isobaric T-x diagram (

Figure 3).

Figure 7b further demonstrates this by showing that when the weak solution concentration is fixed at a higher level (0.6), the COP and circulation ratio show almost no change with increasing evaporator pressure. This highlights that the performance improvement seen in

Figure 7a is directly linked to the changing concentration difference. Despite this improvement, the cycle’s performance remains largely dictated by the generator temperature, as seen in

Figure 5a.

In summary,

Figure 7a,b shows that if the concentration of the solution at the pump inlet is at its minimum allowable value (that avoids vapours at the pump inlet) makes the cycle becomes very sensitive to evaporator pressure. This leads to a noticeable increase in COP that is about 10% when comparing the COP at an evaporator pressure of 1.2 kPa with that at 0.8 kPa. This results from a strong decrease in the circulation ratio as the evaporator pressure increases. The decline in the circulation ratio is due to the larger concentration difference between weak and strong solutions, which enhances mass- and heat-transfer. In contrast, when the weak-solution concentration is fixed at 0.6, the concentration difference becomes small and essentially constant, causing both COP and circulation ratio to remain nearly unchanged across the pressure range.

7.4. Impact of Solution Heat Exchanger Effectiveness

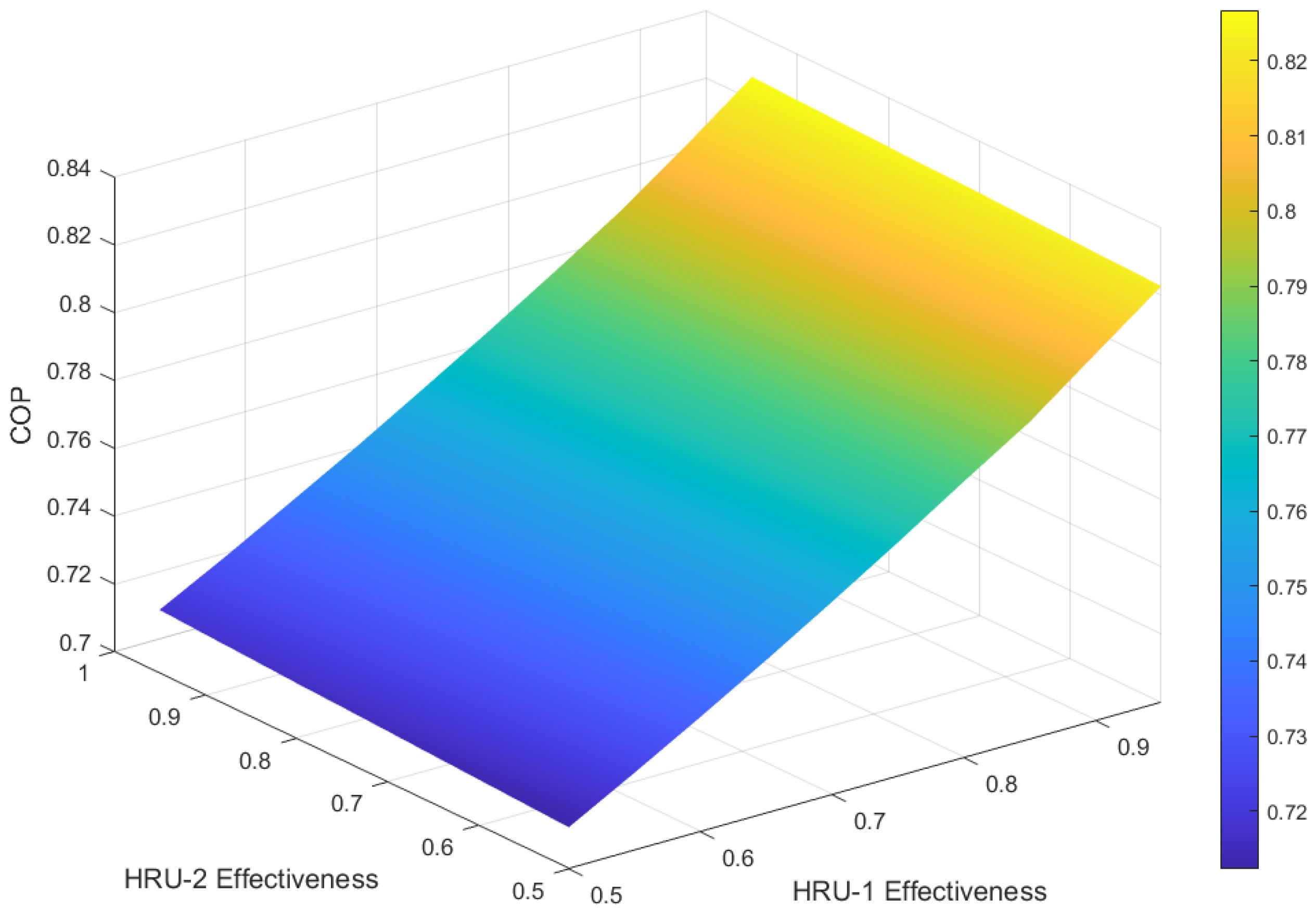

The results shown in the previous sections were obtained with fixed values of heat exchanger effectiveness of 0.5 for both HRU-1 and HRU-2. This section highlights the effect of the heat exchanger effectiveness on the cycle’s performance. This section assumes the generator and condenser/absorber are operating at 100 °C and 40 °C, respectively, and so the weak solution concentration is also fixed at 0.6. The evaporator pressure is also maintained at 0.8 kPa, which corresponds to the evaporator temperature of 4 °C. The solution heat exchangers are crucial for transferring heat from the hot, strong solution leaving the generator to the cooler, weak solution entering it. This preheating of the weak solution reduces the heat input required from the generator, thereby lowering the overall energy consumption and significantly improving the cycle’s COP.

Figure 8 presents a 3D surface plot of COP as a function of heat exchangers, HRU-1 and HRU-2, effectiveness. It is observed that the COP of the cycle is strongly dependent on the effectiveness of HRU-1, with improvement in COP rising from nearly 0.71 to 0.82, respectively, for HRU-1 effectiveness of 0.5 and 0.95. On the contrary, the effectiveness of HRU-2 does not show any significant improvement in the COP of the cycle. Therefore, using HRU-2 in the cycle shown in

Figure 2 increases the cost with no considerable benefits and improvement to the cycle, and so can be removed from the cycle layout.

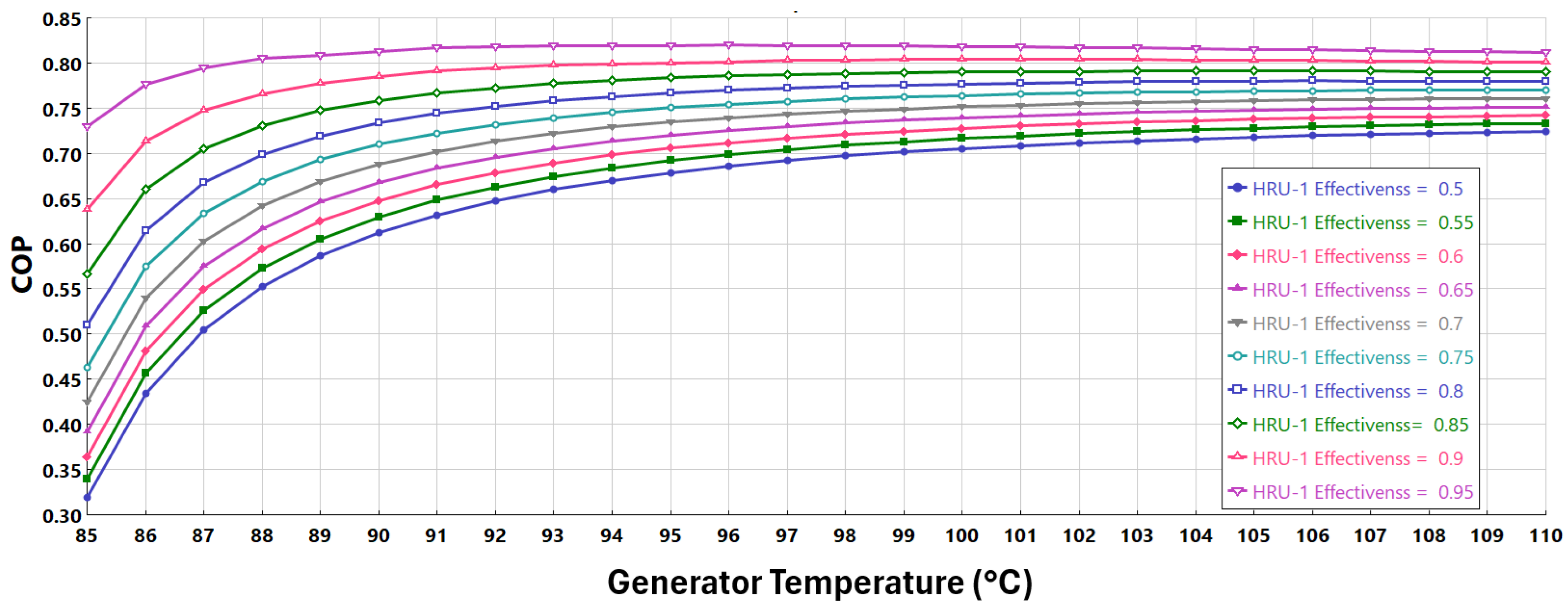

Figure 9 presents the combined effect of generator temperature and HRU-1 effectiveness, ranging from 0.5 to 0.95, on the COP of the cycle. The data presented excludes HRU-2 from the layout, whereas the condenser/absorber operates at 40 °C and the evaporator at 4 °C. Similarly to what is observed previously in

Section 7.1, the COP increases significantly with increasing generator temperature from 85 °C to about 95 °C, after which it tends to plateau, indicating diminishing improvement at higher temperatures.

Additionally, higher HRU-1 effectiveness consistently yields higher COP values, as more heat is recovered within the system, thereby reducing external heat input requirements. The improvement in COP is more pronounced at lower generator temperatures, highlighting the crucial role of effective heat recovery in improving overall system efficiency, especially under moderate thermal input conditions.

7.5. Exergy Analysis

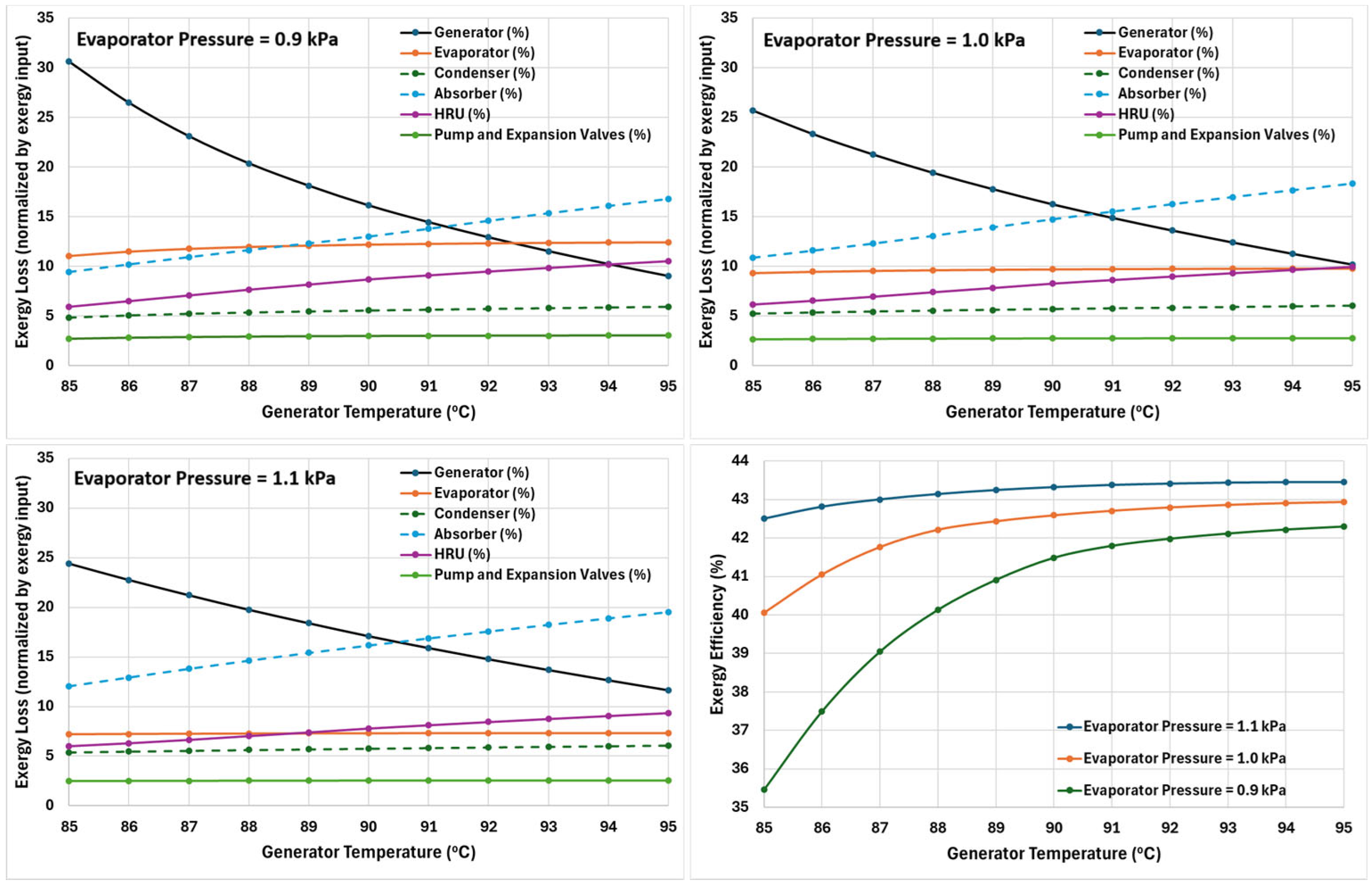

The exergy performance of the cycle is assessed by calculating irreversibilities within the major components of the cycle: generator, evaporator, condenser, absorber, heat recovery units, pump, and expansion valves. Component-wise exergy loss is calculated using the set of equations from Equations (18)–(26). The results are plotted, in

Figure 10, as normalised exergy loss (%) for a range of generator temperatures (85–95 °C) at three evaporator pressures of 0.9, 1.0, and 1.1 kPa (approximately corresponding to evaporator temperatures of 5.5, 7, and 8 °C, respectively). Moreover, the overall exergy efficiency of the cycle is also shown in the same figure.

Across all evaporator pressures, the generator exhibits the highest irreversibilities, especially at lower generator temperatures. However, exergy loss decreases significantly with increasing generator temperature. This is mainly due to a decrease in the temperature difference between the LiBr–H

2O solution and the heat source temperature. Moreover, increasing generator temperature enhances heat transfer and improves refrigerant separation, which leads to less entropy generation. At lower evaporator pressures (0.9 kPa), the generator shows higher irreversibilities. This is because a higher circulation ratio is required at lower evaporator pressure (as seen in

Figure 6), meaning more heat input is needed to produce the same amount of refrigerant.

The evaporator exergy loss plot shows a small but gradual increase with increasing generator temperature, which is mainly driven by increased refrigerant production at higher generator temperatures. Moreover, a small decline in the exergy loss in the evaporator is observed at higher evaporator pressure, which is due to a decrease in the temperature difference between hot and cold fluids in the evaporator.

The exergy loss in the condenser remains nearly constant with only a slight increase at higher generator temperatures. The loss incurred in the condenser accounts for nearly 5% of the overall exergy input. Even though higher generator temperatures produce more refrigerant vapours, increasing the overall load on the condenser, the normalised exergy loss of the condenser shows minimal variation. This is because the condenser was operating at a fixed temperature of 40 °C, and so the normalised exergy loss is largely unaffected by the generator temperature.

The exergy loss in the absorber displays strong dependence on generator temperature and increases significantly with increasing generator temperature. The primary reason for this increase is that the high temperatures in the generator result in the increased temperature difference between the mixing streams (strong solution and refrigerant vapours) in the absorber, leading to higher entropy generation. Moreover, absorption is intrinsically accompanied by high exergy destruction, since the process involves substantial mixing irreversibility and heat rejection to the environment.

The heat recovery unit shows a mild, gradual increase in the exergy loss with increasing generator temperature. Even though HRU improves overall performance by recuperating the heat from within the system, due to the increasing temperature difference between hot and cold streams at higher generator temperature, the overall exergy loss increases, and so a moderate upward trend in exergy destruction is expected. The net exergy loss due to the pump and expansion valves is plotted together as their combined effective loss in the exergy is minimal.