Abstract

Textile recycling promotes a circular economy, a system seeking to minimize waste and maximize the value of textiles by reusing them. Currently, mechanical recycling produces short, weak, and low-quality fibers that diminish the value of the textiles, resulting in downcycled products and loss of value. The Respool Fiber Research (RFR) model was developed from an examination of current practices, relevant literature, and apparel design and material selection models. Demonstrating the capabilities of mechanically recycled textiles in material development, the RFR model is intended for educators, research laboratories and design studios, product developers, and designers. The RFR model ventures beyond current models of textile recycling through its fiber-oriented approach to material development. To demonstrate the application of the RFR model as part of the development process, mechanically recycled cotton fibers and polyester fibers were used to develop yarns and nonwoven fabrics. The application of the RFR model demonstrated that the RFR model is valuable for selecting which recycled fibers are appropriate for different types of products.

Keywords:

textile recycling; circularity; sustainability; materials research; model; cotton; polyester 1. Introduction

The textile industry is one of the largest industrial sectors in the world, with a global market size of USD 1.11 trillion in 2024 [1]. Global textile fiber production reached a record high of 132 million tonnes in 2024, a 128% increase from 58 million tonnes in 2000 [2]. Fashion (apparel) products are the largest product section of textile products, accounting for about 72.9% of the revenue market share of all textile products [1]. In the U.S., consumers purchased a total of 19,989 million garments, an average of 58.8 garments per person, in 2024 [3]. Textile and apparel production and consumption generate a large quantity of textile and apparel waste after consumer use.

Textile waste includes pre-consumer, or post-industrial, waste fabrics that are generated in the textile and apparel manufacturing process and post-consumer waste fabrics that are discarded garments by end-consumers. In 2018, the U.S. generated 17.03 million tons of solid textile waste, among which 2.51 million tons (14.7%) were recycled, and 11.3 million tons (66.4%) were landfilled, which accounted for 7.7% of all municipal solid waste landfilled [4]. It was estimated that more than USD 500 billion in value is lost every year due to the underutilization of clothes and the lack of recycling [5]. Textile recycling promotes a circular economy (CE), a system seeking to minimize waste and maximize the value of textiles by reusing them [6]. Currently, mechanical recycling produces short, weak, and low-quality fibers that diminish the value of the textiles, resulting in downcycled products, such as insulation [7]. Recognizing the pressing need for increased textile recycling infrastructure, researchers worked collaboratively across academia, government, industry, and nonprofits to create a transdisciplinary partnership, ReSpool, for transforming textile and apparel waste into innovative new products [8].

2. Literature Review

2.1. Textile Recycling

Textiles can be recycled through thermal, chemical, and mechanical routes. There are two types of textile recycling. Downcycling is when the product from recycled material is of lower value or quality than the original product, and upcycling is when the product from the recycled material is of higher value or quality than the original product [9].

The thermal recycling route is the conversion of thermoplastic waste, comprising flakes, pellets, or chips, into fibers by a melt-spinning fiber production process [10]. A large quantity of recycled polyester fibers, forming a big market share, is produced through the thermal recycling method. In 2024, the global production of recycled polyester fiber was 9.3 million tonnes, which accounted for 12.0% of global polyester fiber production [2]. About 98% of recycled polyester fibers were made from plastic polyester (polyethylene terephthalate, PET) bottles through thermal recycling methods [2]. A small percentage of polyester textile fabric is thermally recycled. Unifi Inc. (Greensboro, NC, USA) and Ningbo Dafa Chemical Fiber (China) both recycle plastic bottles and textile scrap waste to produce polyester fibers [10].

Chemical recycling includes depolymerizing synthetic polymer fibers to monomers and repolymerizing them to polymers and then dissolving natural or regenerated cellulosic textiles to produce regenerative cellulosic fibers through a wet-spun process [9]. Polyester can be depolymerized through solvolysis, using solvents including water (hydrolysis), methanol (methanolysis), ethylene glycol (glycolysis), and amine (aminolysis) to produce monomers, and then re-polymerized to create a new polyester [11]. Ma et al. dissolved cotton denim waste in a cosolvent of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and ionic liquid 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate ([Bmim]OAc) and wet-spun it into regenerated cellulosic fibers with similar mechanical properties and morphology to viscose fibers [12]. The global production of regenerated cellulosic fibers that were partially or wholly made from recycled materials, such as cotton linter or pre-consumer cotton textile residues, was 90,000 tonnes, or 1.1% of total regenerated cellulosic fiber production in 2024 [2]. Both thermal and chemical recycling of textile waste require high material purity. However, most garments are produced from a blend of fiber materials, which makes textile recycling difficult, especially for post-consumer textile waste. Andini et al. developed a chemical recycling process to depolymerize and separate a mixture of different fiber contents from end-of-use garments using microwave-assisted glycolysis and ZnO as a catalyst [13]. The process can rapidly depolymerize polyester and spandex to their monomers in 15 min, while cotton and nylon (polyamide 6) remain intact and can be separated by a simple solvent dissolution [13].

Mechanical textile recycling shreds or cuts fabrics to preserve fibers [14]. Mechanical recycling is more flexible with regard to fiber content than thermal and chemical recycling. Fabrics made from any type of fiber or fiber blend can be mechanically recycled. However, mechanical recycling results in downcycling, since shredding creates shorter fiber lengths and reduces fiber quality. To preserve textile quality, new fibers are added to mechanically recycled fibers in the textile production [15,16]. Researchers found that the content of mechanically recycled fibers could be 20–30% [15] or up to 50% [16] in textile production without compromising quality.

2.2. Applications for Mechanically Recycled Textiles

Yarns and nonwoven fabrics can be produced from mechanically recycled fibers. Yarn production requires high fiber length, while nonwoven production can use short fibers. Therefore, mechanically recycled fibers are more suitable for producing nonwovens than yarns, and about 95% of mechanically recycled fibers are processed into nonwovens [17]. The fabric tightness of the recycling feedstock affects fiber length after mechanical recycling. It was found that shredding loosely knitted jersey fabric generated longer fibers than tightly knitted interlock fabric [18]. Mechanically recycling heavily worn post-consumer textile waste generated higher fiber lengths than less-worn fabrics, and the fiber length retention from heavily worn fabrics was more significant from single jersey knit fabrics than from tightly woven denim fabrics [16]. Mechanical pretreatment of fabrics through steel needle raising to make the fabric structure more open preserved its fiber length in the mechanical recycling process [19].

Mechanical recycling is generally applied to pre-consumer textile waste, which does not experience wearing and tearing and has a higher quality than post-consumer waste [15]. Pre-consumer textile waste also has simple and clearly identified fiber content and usually does not contain non-textile materials such as buttons and zippers, which makes it easier to recycle than post-consumer textile waste. However, mechanically recycled fibers from heavily worn post-consumer textile waste are a valuable raw material for yarn spinning, since wearing and tearing make the fabric structure more open and generate longer recycled fiber lengths [16].

In yarn production, fibers shorter than 4–5 mm are lost as waste during carding, and fibers shorter than 12–15 mm do not contribute to yarn strength [19]. Ludwig et al. developed yarns from mechanically recycled wool, cotton, polyester, silk, and rayon fibers acquired from pre-consumer and post-consumer textiles and tested the yarns’ size, strength, elongation, and moisture regain [20]. To produce yarns with appropriate strength for weaving and knitting, 100% mechanically recycled wool, polyester, and silk fibers can be used in yarn production, but mechanically recycled cotton and rayon fibers must be blended with new fibers in a ratio of 85% recycled fibers to 15% new fibers to produce yarns [20]. Cotton yarn manufacturer Hilaturas Ferre (Spain) shredded pre-consumer and post-consumer cotton textile waste to produce recycled fibers with a length of 10 to 15 mm and developed yarns using open-end spinning technology [21].

Cao et al. developed nonwoven, woven, quilted, and tufted fabrics from mechanically recycled post-consumer textile waste and tested their textile properties, such as tensile strength and elongation, fabric thickness, thermal resistance, air permeability, and stiffness [22]. Products such as bags, decorative textiles, a hat, cell phone and glasses cases, and a garment were also developed from these textiles [22]. Wazna et al. developed needle-punched nonwoven textiles for building insulation from shredded pre-consumer acrylic and wool waste [23].

2.3. ReSpool

ReSpool is a transdisciplinary partnership among academia, government, industry, and nonprofit entities that has developed a transferable model for mechanical recycling of post-consumer textile and apparel waste into new textile products [8]. ReSpool focused on building regional circular textile ecosystems in two test regions, i.e., Minnesota’s North Shore and the Delaware Valley, and is being transferred to other regions [8]. ReSpool’s engineering team invented proprietary technologies, including the Fiber Shredder, to enable textile-to-fiber shredding for recycled fiber quality retention [9]. Compared to conventional textile shredders, which often produce short, low-value outputs and small pieces of fabric, the ReSpool Fiber Shredder shreds fibers (ReSpool fibers) with sufficient length for yarn and nonwoven development [8,24,25]. ReSpool’s textile development team developed yarns from ReSpool’s mechanically recycled fibers with 15% or less new fibers added. These yarns have appropriate strength for future weaving and knitting [20].

2.4. Apparel Product Design and Material Research Models

2.4.1. Traditional Apparel Product Development Frameworks

Apparel product development includes planning for the creative, technical, production, and distribution aspects of soft goods. These products should provide value for a specific consumer group and be ready for sale when that group is prepared to buy [26]. Traditionally, scholars have viewed the apparel development process as a straight, concept-driven sequence [27,28,29,30]. The typical stages are problem identification, concept and design development, prototype construction, evaluation, and implementation. While there is variation in terminology and scope, all models share an underlying consumer- and market-orientation, linking design decisions to merchandising and production outcomes through a series of discrete, decision-based stages [30]. The process consistently flows from creative ideation toward manufacturing and distribution. LaBat and Sokolowski defined this process with three main phases: problem definition and research, creative exploration and prototype development, and evaluation and implementation [28]. Each phase includes feedback loops that repeat [30]. Later frameworks have added elements of sustainability and technological innovation. Gam et al. created the Cradle-to-Cradle Apparel Design (C2CAD) model [31], which adapts McDonough and Braungart’s Cradle to Cradle design principles [32] for the apparel production field. The C2CAD model includes environmental criteria such as material selection, testing, and collaboration with stakeholders in the traditional stages of product development [31]. Sustainability-oriented models presume stable, predictable material inputs and focus on product form and market fit rather than on the variability arising from recycled or waste-derived fibers. This assumption exposes a methodological gap between the aspiration of circularity and the practical realities of textile waste utilization.

2.4.2. Material-Led and Waste-Led Design Approaches

Relative to concept-based paradigms, material-driven or material-led design paradigms invert the usual development order by commencing with the material itself. Material-led design paradigms emphasize the generative co-implications of a material’s sensoriality, physicality, and its ability to inform design directions [33,34]. For this perspective, design is a form of inquiry—a dialog between material agency and designer intention [35,36]. In fashion and textile design, material-led design encourages more circular and responsive methods by anchoring innovation in the observation of existing materials, such as recycled or reclaimed fibers.

A similar paradigm, Waste-Led Design (WLD), takes this line of reasoning even further by emphasizing end-of-life thinking at the very beginning of the design process [37]. The lack of clear protocols for waste inclusion is one of the significant drawbacks in current industry practice. Approximately 15% of material input is wasted in garment manufacturing through seaming and cutting waste [38]. Even companies with sustainable agendas like Reformation are responsible for 10–20% post-industrial losses from a single roll of fabric [39]. While pre-consumer textile waste is easier to reuse, since it contains minimal contamination [40], recycling trimming cut with elastane blends or plastisol screen inks is difficult, because these components must be separated or chemically removed beforehand [41].

2.4.3. Need for a Recycled Material Selection Protocol

Traditional apparel product development begins with a design concept, whereas a materials-first approach begins with material in hand. To invert this sequence necessitates a formal protocol that can lead the practitioner through material source → property analysis → end-use determination. Bye and Griffin developed a Wearable Product Materials Research (WPMR) model that guides apparel designers to consider material choices based on wearers’ physical and perceptual needs [42]. They also illustrated the application of the WPMR model with the development of a nursing bra and a commercial cooling vest [42].

Recycled materials present unique challenges, such as heterogeneity of fiber, erratic degradation, and uncertain provenance; as such, recycled materials are challenging to integrate into conventional product pipelines. These issues can be resolved through an evaluative framework that integrates empirical material testing and design-based decision-making. Circular textile design practices must address the inherent variability of recycled fibers with models that translate lab data and sensory analysis into feasible design recommendations.

The purpose of this study is to develop a ReSpool Fiber Research (RFR) model for the evaluation of mechanically recycled materials towards “second life” applications for textiles and products and demonstrate the RFR model through textile development. The application of the RFR model would assist product developers in determining potential product pathways that can add value back to the textiles for the reuse and restoration of functionality of materials over multiple use-cycles [43]. The RFR model presented in this study demonstrates operationalized material-led and waste-led principles through a systematic, replicable protocol. It establishes a bridge between textile science and creative practice, supporting evidence-based decision-making for sustainable product innovation.

3. The Development of the ReSpool Fiber Research (RFR) Model

The ReSpool Fiber Research (RFR) model was developed from an examination of current practices, relevant literature, as well as fiber and material experimentation. It expands on Bye and Griffin’s WPMR model [43], which integrates laboratory testing with sensory and aesthetic evaluation. The RFR model also draws from established apparel product development frameworks such as the Functional Expressive Aesthetic (FEA) model [27], three-stage design model [28], and phased product development approaches [30]. The RFR model is informed by Cradle-to-Cradle Apparel Design (C2CAD) frameworks [31] as well as advances in Material-Driven Design (MDD) [33,34] and Waste-Led Design (WLD) [37]. Collectively, these models emphasize the interplay between technical performance, sensory and aesthetic evaluation, material experience, and design intention. The RFR model extends these principles into the emerging canon of recycled fiber evaluation for circular product innovation.

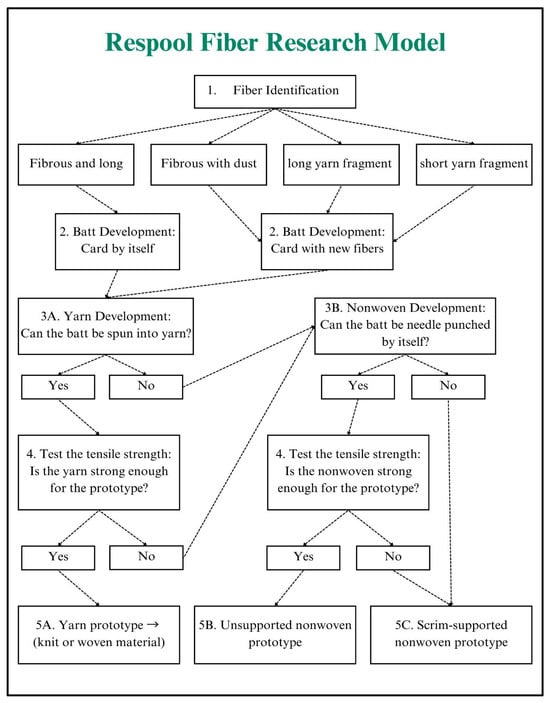

Figure 1 provides an overview of the steps of the RFR model. The first step of the model is to determine the inherent qualities of the recycled fiber through visual, tactile, and sensory evaluation. The 100% mechanically recycled fibers were predominantly long yarns and short fibers, leading the researchers into the second step. To increase the fibrous consistency of the mechanically recycled fibers, the recycled fibers may be mixed with new fibers in the carding process during batt development. If the recycled fibers are long enough, they should be carded without adding new fibers to ensure maximal recycled material use. However, new fibers should be added in the carding process if batts cannot be developed from 100% recycled fibers. To ensure material purity for future recycling or biodegradation, as in the C2CAD model [31], it is important to keep the mixture of recycled and new fibers mono-material. For example, the recycled cotton fibers should be carded with new cotton fibers, and the recycled polyester fibers should be carded with new polyester fibers. If new cotton fiber is not available, the recycled cotton fibers can be carded with other natural cellulosic or protein fibers to ensure the end products can be mechanically recycled again or biodegraded to promote circularity. For recycled polyester fibers, they must be blended with new polyester fibers, so the product can be recycled through a thermal or chemical recycling process at the end of its use to promote circularity.

Figure 1.

The ReSpool Fiber Research (RFR) model.

The batts developed from the second step can be spun into yarns for future weaving and knitting or developed into nonwoven fabrics. The third step of the model prioritizes yarn development in the making of a prototype because its end-uses allow for more upcycling opportunities than a nonwoven prototype. However, if yarn cannot be produced, a nonwoven prototype is also a viable option. To determine which prototype is most appropriate for its application, textile testing, such as tensile strength and elongation tests, should be conducted in the fourth step. In step 5, the development of an unsupported or scrim-supported nonwoven would be most appropriate if the yarns’ tensile strength is too low, while yarns and subsequent knit and woven textile development are appropriate if the yarns’ tensile strength is high.

4. The Application of the RFR Model

4.1. Materials and Methods

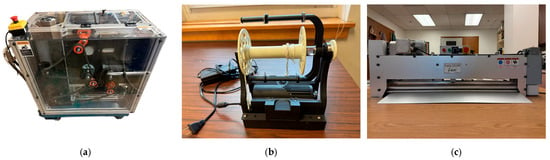

The RFR model is intended to be applied to fibers made from mechanically recycled textiles. To demonstrate the practical feasibility of the Respool Fiber Research (RFR) model, the current study selected two textile waste streams as case studies, i.e., ReSpool recycled fibers from pre-consumer recycled 100% woven denim cotton and recycled 100% woven polyester fabrics, demonstrating how the RFR model can provide a systematic guide to the evaluation of fiber properties, selection of appropriate processing routes, and determination of possible circular textile end-product applications. The researchers obtained ReSpool mechanically recycled polyester and cotton fibers shredded by the proprietary Fiber Shredder (Figure 2a) at the University of Minnesota, Duluth, for yarn and nonwoven development. The fiber content information was acquired from the fiber content label of the end-of-use textile products.

Figure 2.

Instruments used in this research: (a): textile-to-fiber shredder; (b): Electric Eel Wheel Spinner; (c): Feltloom.

The ReSpool recycled cotton and polyester fibers were then carded on a Strauch Drum Carding Machine (Strauch Fiber, Hickory, NC, USA) to make batts. When blending ReSpool recycled fibers with new fibers in batt development, the new fibers were carded first, and then the ReSpool recycled fibers were carded on top of the new fibers, creating a two-layered batt. The batt was removed from the machine and carded two more times. After carding, the batts were spun into 2-ply yarn on an Electric Eel Wheel Spinner (Figure 2b or needle punched on a Feltloom (Model Lexi, Feltloom, Sharpsburg, KY, USA, Figure 2c), creating a nonwoven fabric. For nonwoven fabric development, a batt was cut into four equal squares. The squares were laid on top of each other, alternating fiber orientations to create a multidirectional fiber layup. The batts were then felted eight times.

Before testing, the yarn and nonwoven samples were conditioned at 21 °C and 65% relative humidity in an Environmental Chamber (Lunaire, Model No. CEO910-4, Thermal Product Solutions, New Columbia, PA, USA) following the ASTM D1776 [44] method (Standard Practice for Conditioning and Testing Textiles). For the yarn sample, the researchers tested durability properties (tex, tensile strength, and elongation). The weight of eighteen inches of yarn was measured (with three replications), and the linear density (tex, g/km and denier, g/9 km) data were calculated. Tensile strength and elongation were measured following ASTM D2256 [45] (Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Yarns by the Single Strand Method) using a H5KT Benchtop Materials Tester (Tinius Olsen, Horsham, PA, USA) with three replications. Tenacity data were calculated by tensile strength and tex or denier data (gf/denier). For the nonwoven fabric samples, the researchers tested comfort properties (thickness and air permeability). Thickness was tested using a portable gauge (Model J100, SDL Atlas, Rock Hill, SC, USA) with ten replications. Air permeability was measured by an Automatic Air Permeability Tester (Aveno Technology Co., Quanzhou, China) following the ASTM D737 [46] (Standard Test Method for Air Permeability of Textile Fabrics) with ten replications. The test area was 20 cm2, and the pressure drop across the specimen was 200 Pa.

4.2. Illustration of the RFR Model Application

Figure 3 illustrates the application of the RFR model using ReSpool recycled cotton denim and polyester fibers. In the initial stage, fiber identification established the physical properties and processing potential of each of the ReSpool recycled fibers. Short pieces of yarn existed in the ReSpool fibers from the shredding. The ReSpool recycled denim cotton fibers (a mixture of blue and white colors) exhibited short, fibrous content and fiber dust, which are very short fibrous materials that are not appropriate for further yarn or nonwoven development and discarded as waste. The recycled polyester fibers exhibited longer, durable fibrous materials. These fiber differences then dictated the subsequent stage of batt formation, where the fibers were carded to form prototypically appropriate intermediate webs. In the same manner as Cao et al. [22], who made batts of end-of-use cotton garments by mechanically shredding the garments, then carding the resulting pieces, the recycled denim cotton fibers were mixed with new cotton fibers (white color) with an appropriate ratio to provide superior cohesion and ease of removal from the drum carder without loss of structure. It was found that the weight ratio with the highest recycled cotton fiber content was 85% recycled cotton fiber and 15% new cotton fiber to produce batts. The polyester fibers, however, were long and fibrous enough to individually card into consistent batts without blending with new polyester fibers.

Figure 3.

Application of RFR Model.

The third step, the formation of the prototype, mirrors the adaptive design rationale inherent in the RFR model, where the decision-making is material-driven. Researchers spun the batt of the recycled fibers into yarn using 85% recycled ReSpool cotton and 15% new cotton fibers. The recycled polyester fiber batt was processed through a needle punching technology to form a thick nonwoven textile.

The yarn made from 85% ReSpool and 15% new cotton fibers had a big and uneven diameter, because a two-ply yarn was made from a hand spinning device. ReSpool fibers, both recycled cotton and recycled polyester, were staple fibers from the shredding. Therefore, the researchers observed fuzzy edges on the ReSpool cotton yarn and a fuzzy surface of the ReSpool polyester nonwoven fabric.

The yarns and nonwovens were tested for textile properties to define their tensile strengths, elongation, thickness, and air permeability. The results are in Table 1 and Table 2. Testing data was utilized by researchers to finalize end-product classification. The cotton yarn offered sufficient mechanical performance applicable for woven or knit textile applications [20], which can be further made into garments. The polyester nonwoven fabric showed stable, coherent properties suited for unsupported or scrim-supported applications where added strength was a requirement.

Table 1.

Properties of yarn produced from 85% ReSpool recycled cotton fibers and 15% new cotton fibers (data from [20]).

Table 2.

Properties of nonwoven produced from ReSpool recycled fibers.

5. Discussion

The ReSpool cotton yarn’s breaking force of 2.14 kgf is higher than the peak warp tension in the weaving process (0.1088 kgf) and the highest tension of 51.98 cN (0.530 kgf) in circular knitting (0.530 kgf) and tricot knitting (0.612 kgf) [20]. It can be used in both weaving and knitting processes for fabric production. Due to the large diameter of the 2-ply ReSpool cotton yarn made from a hand spinning device, it is recommended to use a handloom machine or a flatbed knitting machine to produce fabrics from the ReSpool cotton yarn. ReSpool cotton yarns can also be used in hand knitting. Because the ReSpool cotton yarn has a large and uneven diameter, a woven or knitted fabric made from the ReSpool cotton yarn would also be thick and uneven, which would contribute to a unique surface texture of the product, such as a garment.

Air permeability is an important property of nonwoven fabrics, and it increases with a decrease in thickness and density and an increase in porosity [47]. Zhu et al. tested the thickness and air permeability of needle-punched polyester nonwoven fabrics [47]. The ReSpool polyester nonwoven’s air permeability of 2799 mm/s and thickness of 3.49 mm were smaller than Zhu et al.’s samples (air permeability in the range of approximately 6000 to 9000 mm/s, and thickness in the range of approximately 6.4 to 8.6 mm) [47]. The ReSpool polyester nonwoven fabric was less porous than Zhu et al.’s nonwovens. The thin and less porous features of the ReSpool polyester nonwoven fabric made it suitable for application in accessories as well as apparel.

Through the application of the RFR model in both yarn and nonwoven development, this research demonstrates how recycled fibers can be evaluated and directed towards the most appropriate reuse trajectory, recovering material value while reducing waste. As with the process by Cao et al. [22], which converted end-of-use cotton apparel into functional woven, nonwoven, quilted, and tufted products, the RFR model broadens the scope of textile reuse by incorporating structured evaluation criteria—fiber morphology, batt quality, and prototype verification—within an iterative decision-making process. This approach facilitates the restoration of functionality to post-consumer textiles, as well as supporting the development of regionally adaptive circular systems capable of reintroducing waste fibers into new product cycles.

The textile sector’s rapid growth in production and consumption increases post-consumer waste and value loss. This raises the need for systematic, materials-led methods that can transform end-of-use input into second-life, high-value output. Industry trends, such as rising global fiber production and apparel throughput, put additional pressure on recycling systems. These systems mainly downcycle materials because mechanical shredding damages fibers, making them shorter and weaker. The RFR model was created to tackle this quality–value issue: mechanical methods allow for flexible input purity but degrade fibers, while chemical and thermal methods require purity and often struggle with blends and trims. RFR model specifically addresses this gap by linking fiber characterization, batt development, prototype pathway (yarn spinning vs. nonwoven development), property testing, and product decision. This process reduces uncertainty in early-stage development and helps retain value instead of downcycling.

In the apparel and product design literature, traditional frameworks often assume predictable and stable inputs. They only implicitly consider materials as variables. Materials-led and waste-led approaches flip this order, putting material agency and variability at the forefront. The Wearable Product Materials Research (WPMR) model by Bye and Griffin [42] established a hands-on, low-cost way to evaluate materials and prototyping. As well, approaches such as The Material-Driven Design method [33] and Waste-Led Design [37] have pushed the field forward by making material behavior a key factor in design decisions. RFR model builds on this approach by applying a materials-first logic to mechanically recycled fibers. It adds classes for fiber morphology, batt formation rules, and specific performance tests linked to circular product paths like mono-material yarns compared to nonwovens and unsupported versus scrim-supported options.

6. Conclusions

The RFR model provides a novel and empirically grounded approach to assess mechanically recycled fibers suitable for specific pathways such as yarns or nonwoven fabrics. The RFR model was developed as part of the ReSpool project [8], which employs design thinking, human-centered design, and user discovery to integrate scientific, engineering, and community perspectives in solving complex problems. The development environment for the RFR model emphasizes iterative prototyping and cross-sector collaboration, shaping the model’s fiber-first, application-oriented structure. In this study, we implement the RFR model using quantitative testing to demonstrate its scientific utility and applicability to recycled fiber pathways.

By beginning with fiber characterization rather than a pre-determined design concept, the RFR model, as a “material-first” process, offers a structured protocol that has direct impacts on design practice, education, and manufacturing systems. For designers and research and development teams, the RFR model helps speed up evidence-based “go/no-go” choices and makes prototyping more effective. For mills and converters, the RFR model offers precise input specifications and blend ratios for recycled materials, while brands can make solid recycled-content claims backed by measured performance.

As a teaching tool, the RFR model improves understanding of materials by combining textile science tests with design thinking. This method helps students and professionals connect fiber behavior to the choice of sustainable end-use. Although this study focused on two mono-fiber streams and lab-scale production, the findings show a scalable way to grasp the potential of recycled fiber. Future developments include textile property tests of prototypes, including developing knits and wovens from the yarn prototype, and application of the model on a larger scale, industry setting. Ultimately, the RFR model demonstrates how design research and materials science can converge to operationalize circularity—transforming variability into a framework for resilient circular textile systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.C., M.Y. and K.L.; methodology, K.C., H.C., M.Y. and K.L. and S.G.; validation, M.Y., K.L. and S.G.; formal analysis, K.C., H.C., M.Y. and K.L.; writing—original draft preparation, K.C., H.C., M.Y. and K.L.; writing—review and editing, K.C. and H.C.; visualization, K.C., K.L. and M.Y.; funding acquisition, K.C. and H.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation, award number 2236100.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Abigail Clarke-Sather and the Applied Sustainable Product Innovation and Resilient Engineering (ASPIRE) Lab of the University of Minnesota, Duluth, for providing the ReSpool mechanically recycled fibers and the picture of the textile-to-fiber shredder.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Grand View Research. Textile Market (2025–2033) Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report by Raw Material (Cotton, Wool, Chemical, Silk), by Product (Natural Fibers, Polyester), by Application (Household, Technical), by Region, and Segment Forecasts. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/textile-market (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Textile Exchange. Materials Market Report. 2025. Available online: https://textileexchange.org/knowledge-center/reports/materials-market-report-2025/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- American Apparel and Footwear Association. ApparelStats. 2025. Available online: https://www.aafaglobal.org (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Environmental Protection Agency. Textiles: Material-Specific Data. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling/textiles-material-specific-data (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future. 2017. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/a-new-textiles-economy (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Facilitating a Circular Economy for Textiles Workshop Report. 2022. Available online: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.1500-207.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Thompson, N. Textile Waste & the 3R’s: Textile Waste Strategy Recommendations for the City of Toronto; Major Paper in Master of Environmental Studies; York University: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, K.; Clarke-Sather, A.R.; Cobb, K.; Cao, H. Respool: Scaling a circular supply chain for recycled textiles. J. Adv. Manuf. Process. 2025, 7, e70000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandin, G.; Peters, G.M. Environmental impact of textile reuse and recycling—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 353–365. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Tan, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhu, G.; Yin, R.; Tao, X.; Tian, X. Industrialization of open- and closed-loop waste textile recycling towards sustainability: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 436, 140676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Darai, T.; Ter-Halle, A.; Blanzat, M.; Despras, G.; Sartor, V.; Bordeau, G.; Lattes, A.; Franceschi, S.; Cassel, S.; Chouini-Lalanne, N.; et al. Chemical recycling of polyester textile wastes: Shifting towards sustainability. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 6857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zeng, B.; Wang, X.; Byrne, N. Circular textiles: Closed loop fiber to fiber wet spun process for recycling cotton from denim. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 11937–11943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andini, E.; Bhalode, P.; Gantert, E.; Sadula, S.; Vlachos, D.G. Chemical recycling of mixed textile waste. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, 6827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribul, M.; Lanot, A.; Pisapia, C.T.; Purnell, P.; McQueen-Mason, S.J.; Baurley, S. Mechanical, chemical, biological: Moving towards closed-loop bio-based recycling in a circular economy of sustainable textiles. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 326, 129325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Echeverria, D.; Venditti, R.; Jameel, H.; Yao, Y. Supply chain of waste cotton recycling and reuse: A review. AATCC J. Res. 2020, 7, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronsson, J.; Persson, A. Tearing of post-consumer cotton t-shirts and jeans of varying degree of wear. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 2020, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piribauer, B.; Bartl, A. Textile recycling processes, state of the art and current development: A mini review. Waste Manag. Res. 2019, 37, 112–119. [Google Scholar]

- Utebay, B.; Celik, P.; Cay, A. Effects of cotton textile waste properties on recycled fibre quality. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstrom, K.; van der Holst, F.; Berglin, L.; Persson, A.; Kadi, N. Mechanical Textile Recycling Efficiency: Sample configuration, treatment effects, and fibre opening assessment. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, K.; Gupman, S.; Yatvitskiy, M.; Cao, H.; Cobb, K. Development and Evaluation of Yarns Made from Mechanically Recycled Textiles. Textiles 2025, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteve-Turrillas, F.A.; de la Guardia, M. Environmental impact of Recover cotton in textile industry. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 116, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Cobb, K.; Yatvitskiy, M.; Wolfe, M.; Shen, H. Textile and product development from end-of-use cotton apparel: A study to reclaim value from waste. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazna, M.E.; Gounni, A.; Bouari, A.E.; Alami, M.E.; Cherkaoui, O. Development, characterization and thermal performance of insulating nonwoven fabrics made from textile waste. J. Ind. Text. 2019, 48, 1167–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira Franca Alves, P.H.; Bahr, G.; Clarke-Sather, A.R.; Maurer-Jones, M.A. Combining flexible and sustainable design principles for evaluating designs: Textile recycling application. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2024, 146, 020903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrani, H.; Clarke-Sather, A.; Ludwig, K.; Yatvitskiy, M.; Gupman, S.; Cobb, K.; Cao, H. Textile Circular Economy: Addressing Material Waste in Recycling and Product Development. In Proceedings of the International Design Engineering Technical Conferences & Computers and Information in Engineering (IDETC-CIE) 2025 Conference, Anaheim, CA, USA, 17–20 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Keiser, S.J.; Vandermar, D.A.; Garner, M.B. Beyond Design: The Synergy of Apparel Product Development, 5th ed.; Fairchild Books, Bloomsbury Publishing Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, J.M.; Kallal, M.J. A Conceptual Framework for Apparel Design. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 1992, 10, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaBat, K.L.; Sokolowski, S.L. A Three-Stage Design Process Applied to an Industry–University Textile Product Development Project. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 1999, 17, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, C.L.; Kincade, D.H.; Sheldon, G. Applicability of the Engineering Design Process Theory in the Apparel Design Process. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 1998, 16, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May-Plumlee, T.; Little, T.J. No-Interval Coherently Phased Product Development Model for Apparel. Int. J. Cloth. Sci. Technol. 1998, 10, 342–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gam, H.J.; Cao, H.; Farr, C.; Heine, L. C2CAD: A Sustainable Apparel Design and Production Model. Int. J. Cloth. Sci. Technol. 2009, 21, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, W.; Braungart, M. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things; North Point Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Karana, E.; Barati, B.; Rognoli, V.; Zeeuw van der Laan, A. Material Driven Design (MDD): A Method to Design for Material Experiences. Int. J. Des. 2015, 9, 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rognoli, V. A Broad Survey on Expressive-Sensorial Characterization of Materials for Design Education. METU J. Fac. Archit. 2011, 28, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, T. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tonkinwise, C. Design Ethics beyond Consumerism. In The Routledge Handbook of Sustainable Design; Egenhoefer, R.B., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Semaan, C. Waste-Led Design. Available online: https://slowfactory.earth/courses/waste-led-design/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- ElShishtawy, N.; Sinha, P.; Bennell, J.A. A Comparative Review of Zero-Waste Fashion Design Thinking and Operational Research on Cutting and Packing Optimisation. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2022, 15, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reformation. The Sustainability Report Q3 2023. Available online: https://www.thereformation.com/circularity.html (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Lau, Y.-I. Reusing Pre-Consumer Textile Waste. SpringerPlus. 2015, 4, O9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, K.; Tsianou, M.; Alexandridis, P. Recycling of Blended Fabrics for a Circular Economy of Textiles: Separation of Cotton, Polyester, and Elastane Fibers. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bye, E.; Griffin, L. Testing a Model for Wearable Product Materials Research (WPMR). Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2015, 8, 139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Niinimäki, K.; Peters, G.; Dahlbo, H.; Perry, P.; Rissanen, T.; Gwilt, A. The Environmental Price of Fast Fashion. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D1776/D1776M-20; Standard Practice for Conditioning and Testing of Textiles. American Society for Testing and Materials: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM D2256/D2256M-21; Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Yarns by Single-Strand Method. American Society for Testing and Materials: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM D737-18; Standard Test Method for Air Permeability of Textile Fabrics. American Society for Testing and Materials: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2018.

- Zhu, G.; Kremenakova, D.; Wang, Y.; Militky, J. Air Permeability of Polyester Nonwoven Fabrics. AUTEX Res. J. 2015, 15, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).