In this study, co-word analysis was selected as the primary science mapping technique. This content-based approach captures the semantic structure of a research domain by jointly modeling the appearance of keywords across publications. Unlike citation-based methods, this technique emphasizes the lexical and conceptual content of scholarly outputs, revealing how ideas are articulated and connected within the literature [

44,

45]. This methodological choice is particularly relevant in the context of Blue Finance, where conceptual boundaries remain fluid and are actively shaped through thematic experimentation and cross-sectoral integration. By analyzing co-occurring author keywords, this analysis enables the identification of conceptual clusters that map the conceptual backbone of Blue Finance. This approach reveals both the central paradigms structuring the field and the peripheral themes that signal emerging niches and future research trajectories. It highlights how core themes, peripheral niches, and emerging trajectories are structured and interrelated, offering a fine-grained semantic perspective on the field’s organization [

46]. A keyword co-occurrence network, illustrated in

Figure 4, visualizes the conceptual structure of research on blue finance. The centrality and typographic prominence of “blue economy” underscore its role as the foundational construct around which key thematic clusters coalesce. Notably, the prominence and proximity of “sustainable finance,” “blue bonds,” and “green bonds” suggest strong conceptual linkages, reflecting a scholarly emphasis on financial instruments that advance ocean sustainability. This financial cluster highlights the anchoring of blue finance in market-based mechanisms and the gradual integration of ocean finance into sustainable investment strategies. The co-occurrence of “climate change,” “marine conservation,” and “marine spatial planning” further underscores an integrated research agenda that bridges environmental governance and economic policy. Geographic markets, including “China” and “Seychelles,” point to case-specific investigations, while the presence of “COVID-19” indicates a growing effort to contextualize blue finance within global systemic shocks. Beyond descriptive mapping, the network configuration shows an intense concentration around financial-ecological nexus concepts, indicating that Blue Finance is increasingly organized around hybrid constructs that integrate environmental risk, governance tools, and financial design. Together, these patterns depict an interdisciplinary knowledge structure characterized by a substantial environmental–financial nexus, geographic diversification, and responsiveness to external shocks, positioning blue finance as a rapidly consolidating frontier in sustainability science.

4.2.1. Thematic Clustering and Conceptual Interpretation

Coupling co-word mapping with targeted content analysis transcends descriptive visualization to reveal the cognitive architecture of Blue Finance research. This integrated approach shifts the analytical lens from structural detection to conceptual interpretation, uncovering how thematic clusters are conceptually constructed, discursively mobilized, and dynamically reshaped within the scholarly corpus. By articulating network topology with contextual content reading, it clarifies the positioning, internal coherence, and evolutionary logic of core knowledge domains. This enables a deeper understanding of how emerging research trajectories consolidate into stable thematic paradigms and how peripheral debates evolve into recognized conceptual frontiers. To operationalize this framework, the co-word network was constructed and visualized in VOSviewer with a minimum occurrence threshold of four, ensuring analytical precision while minimizing lexical noise. Ambiguous or overly generic terms were systematically excluded, and semantically related expressions were manually merged to enhance conceptual coherence. This refinement yielded a robust set of 26 core keywords that define the conceptual backbone of the Blue Finance research domain.

Figure 5a illustrates the resulting network structure: 20 salient terms organized into three interconnected clusters, linked by 51 edges with a total link strength of 80, indicating a moderate-to-high density network, suitable for identifying cohesive thematic structures. Node size reflects keyword frequency, while edge thickness signifies co-occurrence intensity. Central anchors, including “blue economy,” “blue finance,” “blue bonds,” “sustainable finance,” and “climate change,” delineate the field’s core semantic architecture and act as connective pivots across thematic dimensions.

Figure 5b presents a temporal overlay visualization that traces the field’s evolution through successive phases. The initial stage (2007–2013) is dominated by ecological and climatic concerns, emphasizing environmental risk, resource scarcity, and ecosystem valuation. The transitional phase (2014–2018) introduces governance-oriented concepts, including “sustainability,” “marine conservation,” and “spatial planning,” signaling institutional consolidation. From 2019 onward, the center of gravity shifts toward “blue economy” and related financial instruments, while the latest period (2022–2025) is marked by the emergence of “blue bonds,” “equity,” “Seychelles,” and governance-linked concepts including “blue justice.” This three-phase trajectory encapsulates the conceptual maturation of Blue Finance, reflecting its transformation from an ecologically rooted idea to a financially structured and policy-integrated research paradigm. Overall, the clustering results confirm that climate–environmental risk, sustainability-governance integration, and financial innovation constitute the three structurally central themes around which the Blue Finance literature is organized.

To ensure analytical transparency, the VOSviewer clustering results were systematically examined through a structured interpretation protocol that involved a close reading of cluster-associated documents to identify recurrent conceptual patterns, thematic boundaries, and cross-cluster linkages. This interpretive refinement enhances analytical precision, mitigates descriptive redundancy, and strengthens the conceptual validity of cluster classification. It yields a coherent and methodologically rigorous representation of the conceptual organization of Blue Finance scholarship, as detailed in

Table 5. To complement this structural mapping, Gephi software (version 0.10.1) was employed to visualize trend-based, capturing the temporal and relational evolution of knowledge structures within and across clusters, as summarized in

Table 6. In this context, thematic clusters delineate the field’s structural foundations. At the same time, trend-based trace their conceptual trajectories, providing a comprehensive analytical framework for decoding their cognitive architecture and evolutionary dynamics.

4.2.2. Thematic Trends and Research Topics

Grounded in co-word analysis that delineates the field’s conceptual structure, a complementary content analysis was conducted to enhance interpretive depth and contextual precision. This combined approach identifies dominant and emerging research fronts while revealing how core concepts are defined, operationalized, and interlinked across the corpus. By moving beyond descriptive mapping, the analysis offers a strategic synthesis of conceptual patterns and thematic evolution, advancing Blue Finance toward greater theoretical and policy relevance [

47,

48].

Research Topic 1: Innovative Blue Finance Mechanisms and Economic Resilience

Cluster 1 reflects the financial innovation pillar of Blue Finance, emerging as the core thematic structure within the co-word network. With an average publication year around 2023 and a dense web of conceptual linkages anchored by the term “blue economy,” this cluster illustrates the convergence of research streams on financial innovation, ocean governance, and economic resilience. The prominence of “blue economy” (occurrence = 30, links = 14), together with “blue finance” (10, 9), “blue bonds” (10, 6), and “Seychelles” (4, 7), reveals a highly cohesive conceptual core, reflecting the growing scholarly interest in financing mechanisms dedicated to sustainable marine development [

49,

50].

A closer examination of this cluster shows a growing interest in the evolving discourse on ocean finance. Instruments including blue bonds, blended finance structures, and debt-for-nature swaps are increasingly discussed beyond their early experimental framing, reflecting their potential to mobilize capital over extended horizons [

51,

52]. The 2018 Seychelles sovereign blue bond issuance exemplifies this transition, illustrating how concessional and market-based financing can be strategically combined to support marine spatial planning, fisheries management, and ecosystem protection. Collectively, these instruments represent the expanding role of innovative finance in supporting ocean resilience.

The co-occurrence of terms including “COVID-19” and “fisheries” suggests that some contributions address how external shocks affect ocean-based sectors within blue finance discussions. Blue finance is examined in some studies for its potential to serve as a countercyclical instrument that can stabilize critical ocean-based sectors during external shocks, including pandemics and climate-related disruptions [

53,

54]. This emphasis aligns with broader evidence highlighting the potential of targeted ocean finance to strengthen both economic and ecological resilience in vulnerable economies [

4]. In parallel, critical literature raises concerns about governance, transparency, and distributive equity, emphasizing the fair allocation of benefits and responsibilities among stakeholders [

49]. Scholars highlight the risks of bluewashing, where symbolic commitments exceed verifiable ecological outcomes [

55], and question the limited debt relief achieved under current financing models [

51], underscoring the need for robust accountability mechanisms and standardized impact metrics.

Recent contributions position blue bonds and the Seychelles as emblematic instruments of innovative blue finance. The 2018 issuance marks a pivotal moment in aligning capital markets with marine conservation and sustainable development objectives. Blue bonds operationalize blended finance by mobilizing concessional resources, private capital, and ESG principles to strengthen fisheries resilience and marine spatial planning [

49,

50]. Building on this momentum, Blue Sukuk has emerged as a complementary mechanism that embeds Islamic finance principles to expand investor participation and deepen conservation funding [

56]. Their growing prominence illustrates the field’s evolution toward diversified, inclusive, and impact-oriented financing pathways. While promising, their transformative capacity hinges on transparent governance, rigorous monitoring, and equitable distribution [

51,

55]. Collectively, these contributions highlight recurrent themes in the literature on innovative blue finance and its emerging instruments, reinforcing the significance of this research stream within broader debates on financing ocean resilience and sustainable development.

Although innovative instruments, including blue bonds, blended finance, and debt-for-nature swaps, are widely promoted, critical studies warn that they may intensify fiscal dependence, create “blue debt,” and enable bluewashing when impact verification is weak. These concerns reflect a broader debate in conservation finance, which questions whether market-based tools can generate durable ecological outcomes in contexts of institutional fragility and inequality. Their transformative potential, therefore, depends less on financial innovation itself than on governance legitimacy, transparent accountability, and equitable benefit-sharing.

Research Topic 2: Blue Finance for Sustainability Integration and Governance

Cluster 2 reflects the sustainability integration pillar of Blue Finance and is anchored primarily around the terms “sustainable finance” and “sustainability”, which exhibit the highest occurrences and citation intensity within this thematic configuration. The cluster also includes “blue justice,” “marine conservation,” “marine spatial planning,” “sustainable development,” and “conservation finance.” This constellation of concepts points to an emerging consolidation in the literature, in which sustainability concerns are increasingly embedded in discussions of blue finance and its associated governance mechanisms. Rather than suggesting a definitive functional role, the co-occurrence structure indicates a progressive integration of ecological, financial, and institutional dimensions in recent scholarship. It illustrates how conservation is increasingly framed not only as an environmental imperative but also as a strategic financial and governance endeavor [

39,

57]. “Sustainable finance” (links = 9; occurrences = 9; average publication year = 2023.0) emerges as the conceptual anchor, reflecting its central role in discussions on mobilizing capital for marine sustainability. Innovative financial instruments, including impact investments, biodiversity offsets, insurance mechanisms, and blue carbon credits, are recurrent mechanisms in the literature for strengthening long-term conservation financing. These instruments are frequently discussed alongside governance frameworks, notably marine spatial planning and co-management models, reflecting a thematic association among financial flows, ecological objectives, and institutional capacity-building [

38,

57,

58,

59].

Equally integral to this thematic structure is “blue justice” (links = 3; occurrences = 4; average publication year = 2023.8; average citations = 1.0995), which foregrounds social fairness, inclusivity, and community rights. Beyond its normative scope, it directly shapes resource allocation, benefit distribution, and participatory mechanisms, embedding fairness as a core operational principle of blue finance [

60]. Taken together, the co-occurring terms indicate that sustainability forms the conceptual backbone of Cluster 2, with governance and equity emerging as closely associated themes in the relevant scholarship. Studies consistently highlight how sustainable finance frameworks, governance arrangements, and justice principles intersect in discussions of transparency, participation, and social fairness, reinforcing the prominence of these dimensions in blue finance research.

Research Topic 3: Climate–Environmental Risk Interfaces in Blue Finance

Cluster 3 represents the foundational thematic strand of Blue Finance, centered on “climate change” and “water footprint,” which exhibit the highest co-occurrence strength and citation intensity in the network. With an average publication year around 2021 this cluster reflects earlier scholarly attention to environmental risk, resource security, and the financial valuation of ecosystem services. It captures an initial stage in which blue finance began to be framed in relation to climate-induced vulnerabilities and ecological stress.

The thematic configuration highlights the convergence between climate risk, resource security, and environmental finance mechanisms. A significant body of literature demonstrates that climate-driven stressors reshape both ecological systems and economic structures, particularly in regions highly exposed to environmental degradation and resource scarcity [

61]. Within this nexus, ecosystem services emerge as a pivotal analytical construct, linking environmental stress to the valuation of natural capital and the translation of ecological vulnerability into measurable financial risks. This framing marks a conceptual shift from traditional resource management to adaptive, finance-based strategies for climate resilience. Recent contributions show a growing tendency to frame environmental risks as both systemic financial pressures and catalysts for finance-enabled resilience strategies embedded within sustainability frameworks [

62]. Trend analysis identifies “water footprint” (links = 2; occurrences = 10) as the key anchor of this cluster, signaling intensified scholarly focus on integrating environmental risk metrics into climate adaptation and sustainable finance models [

63,

64]. Collectively, this cluster underscores the foundational role of climate–environmental risk in shaping the conceptual roots of Blue Finance. It lays the conceptual groundwork for subsequent research streams in sustainability integration and financial innovation, positioning environmental risk as both a catalyst and a connective axis for the field’s theoretical and practical evolution.

A parallel strand of critical literature questions the growing financialization of ecosystem services within this research stream. While natural capital valuation and blue carbon credits are promoted as mechanisms to mobilize conservation finance, scholars argue that translating ecological functions into investment assets risks reducing complex socio-ecological processes to marketable units of value [

65]. The legitimacy of these valuation practices is further challenged by scientific uncertainty, methodological arbitrariness, and power asymmetries that privilege investors and intermediaries over local communities. These critiques underscore that the investment framing of ecosystem services is not a neutral extension of environmental finance but a contested transformation with ethical, distributive, and epistemic implications. Understanding when and for whom this financialization generates genuine ecological and social benefits remains a central challenge for future blue finance scholarship.

4.2.3. Research Agenda and Challenges for the Blue Finance Frontier

Drawing on the structural patterns and knowledge gaps identified through bibliometric and science-mapping analysis,

Table 7 proposes a forward-looking research agenda to consolidate Blue Finance as both a platform of financial innovation and a catalyst for sustainability transitions. This agenda integrates conceptual, methodological, and operational priorities to bridge the persistent divide between financial mechanisms, environmental governance, and climate resilience. Collectively, these research directions delineate the next frontiers of Blue Finance, where sustainability, innovation, and resilience converge to shape the evolution of ocean investment research.

The first axis, Innovative Blue Finance Mechanisms and Economic Resilience, calls for a transition from descriptive analyses of blue bonds, Blue Sukuk, blended finance, and debt-for-nature swaps toward rigorous, impact-oriented evaluation frameworks. Persistent governance and impact-reporting gaps in early sovereign blue bond implementations [

66] reinforce this need, and future inquiries must develop standardized models for assessing ecological and socioeconomic returns while embedding equity, governance, and transparency principles. Advancing risk-adjusted valuation systems and unified monitoring protocols can strengthen investor confidence and accountability. Expanding blended finance and credit enhancement mechanisms remains central to mobilizing private capital, yet fragmented regulation and capacity asymmetries continue to constrain scalability.

The second axis, Blue Finance for Sustainability Integration and Governance, emphasizes the institutionalization of sustainability and blue justice principles within marine financial architectures. The persistent underfunding of marine protected areas and fragmented governance structures hinder implementation. Future studies should advance hybrid financing models, aligning philanthropic, public, and private resources to achieve durable conservation outcomes. Embedding Blue-ESG metrics into investment decision-making, reinforcing co-management frameworks, and mainstreaming equity-based accountability will enhance the alignment between ecological stewardship and financial governance.

The third axis, Climate-Environmental Nexus and Finance-Driven Resilience, underscores the urgency of embedding climate stress indicators and environmental risk metrics within blue finance architectures. Despite rising awareness of climate-induced vulnerabilities, empirical validation and model integration remain limited. Research should explore how blue bonds, public–private partnerships, and blue carbon credits can operate as adaptive finance instruments that reinforce systemic resilience. Integrating geospatial analytics, climate-risk modeling, and sustainability indices will enable evidence-based, context-sensitive financial strategies, particularly in emerging and coastal economies.

Taken together, these three axes outline a research agenda that reflects both the conceptual expansion and the operational maturation of Blue Finance. Nonetheless, several challenges persist, including non-standardized impact metrics, fragmented regulation, limited empirical validation of instruments, and persistent inequities in benefit-sharing, especially in vulnerable coastal and island economies. Across these three axes, a critical research challenge concerns the growing financialization of ocean resources. As conservation finance mechanisms increasingly treat ecosystem functions and carbon-sequestration capacities as investment assets, scholars highlight unresolved ethical, distributive, and epistemic concerns. This transformation raises fundamental questions about who defines value, who captures benefits, and how market-based instruments reshape power relations within coastal communities. Addressing these tensions is essential for ensuring that blue finance contributes to genuine ecological resilience rather than reproducing social or environmental inequities. Overall, this research agenda defines the frontier of Blue Finance as a transformative space where financial systems evolve to serve ecological imperatives. It calls for a paradigmatic shift from fragmented experimentation to systemic integration, from descriptive mapping to measurable impact, and from isolated innovation to inclusive governance. Advancing this frontier demands cross-sectoral collaboration among scholars, investors, and policymakers to design transparent, adaptive, and equitable ocean finance ecosystems that sustain both economic prosperity and planetary well-being.

Table 7.

Research Agenda for Blue Finance.

Table 7.

Research Agenda for Blue Finance.

| Research Topic | Research Gaps | References | Research Agenda | Sustainability Implementation Challenges |

|---|

| Topic 1: Innovative Blue Finance Mechanisms and Economic Resilience | - −

Limited causal evidence on the ecological and socio-economic impact of blue finance instruments (blue bonds, Blue Sukuk, blended finance, debt-for-nature swaps) - −

Weak integration of equity and governance dimensions - −

Lack of standardized risk–return/pricing frameworks for blue assets - −

Low private capital mobilization - −

Verification gaps and bluewashing risks - −

Over-reliance on case studies (Seychelles)

| [4,49,50,51,52,53,55,56,67,68] | - −

Develop longitudinal impact evaluation to assess real outcomes (MPA coverage, stock status, income) - −

Build risk-adjusted valuation models and impact-linked pricing tools for blue assets - −

Strengthen governance, taxonomy alignment, and independent verification - −

Integrate equity and benefit-sharing protocols - −

Expand blended finance, Blue Sukuk, and credit enhancement mechanisms to mobilize private capital

| - −

Fragmented regulatory frameworks - −

Weak MRV (Monitoring, Reporting, Verification) and disclosure systems for blue assets - −

High investor risk asymmetry and limited blue asset track records - −

Underdeveloped blue asset markets - −

Capacity gaps in SIDS - −

Limited access to affordable local finance

|

| Topic 2: Blue Finance for Sustainability Integration and Governance | - −

Chronic underfunding of MPAs and conservation projects due to limited blue finance deployment - −

Fragmented governance and weak integration of blue justice principles within financing frameworks - −

Lack of standardized and scalable co-management financing models - −

Insufficient alignment between conservation objectives and financial structures - −

Uneven adoption of Blue-ESG disclosure standards

| [39,57,58,59,60,69] | - −

Develop hybrid blue finance models combining public, philanthropic, and private capital to secure long-term conservation funding - −

Institutionalize equity and governance mechanisms within blue finance instruments - −

Strengthen financial sustainability assessment frameworks for MPAs and conservation assets - −

Advance integration of Blue-ESG metrics into financial decision-making and reporting - −

Foster adaptive co-management frameworks linking financial flows to measurable conservation outcomes

| - −

Regulatory and governance fragmentation - −

Weak enforcement capacity and lack of harmonized standards for blue financing mechanisms - −

Overreliance on short-term donor funding - −

Limited investor interest in non-market conservation assets - −

Asymmetric capacities across regions and institutions

|

| Topic 3: Climate–Environmental Interfaces in Blue Finance | - −

Limited integration of climate and environmental risk indicators into blue finance frameworks - −

Limited predictive modeling of climate-driven systemic risks for investment strategies - −

Weak empirical evidence on the effectiveness of blue finance instruments (blue bonds, PPPs, blue carbon finance) - −

Lack of standardized climate-risk metrics for disclosure and ESG alignment - −

Limited transferability of existing frameworks across developed and emerging economies

| [22,62,63,64] | - −

Integrate climate-induced environmental stress indicators into blue finance architectures to strengthen risk-informed investment strategies - −

Expand empirical assessments of blue bonds, PPPs, and blue carbon credits as resilience-enhancing mechanisms - −

Develop standardized climate-risk metrics and disclosure frameworks aligned with ESG finance - −

Link financial innovation to adaptation and resilience objectives in marine and coastal systems - −

Foster policy coordination and incentive structures to scale capital mobilization for climate resilience

| - −

Fragmented regulatory and governance frameworks - −

Weak MRV and disclosure systems for climate-related risks - −

Underdeveloped markets for resilience-oriented financial instruments - −

Investor uncertainty and asymmetrical risk perception - −

Limited institutional capacity and weak cross-sector coordination

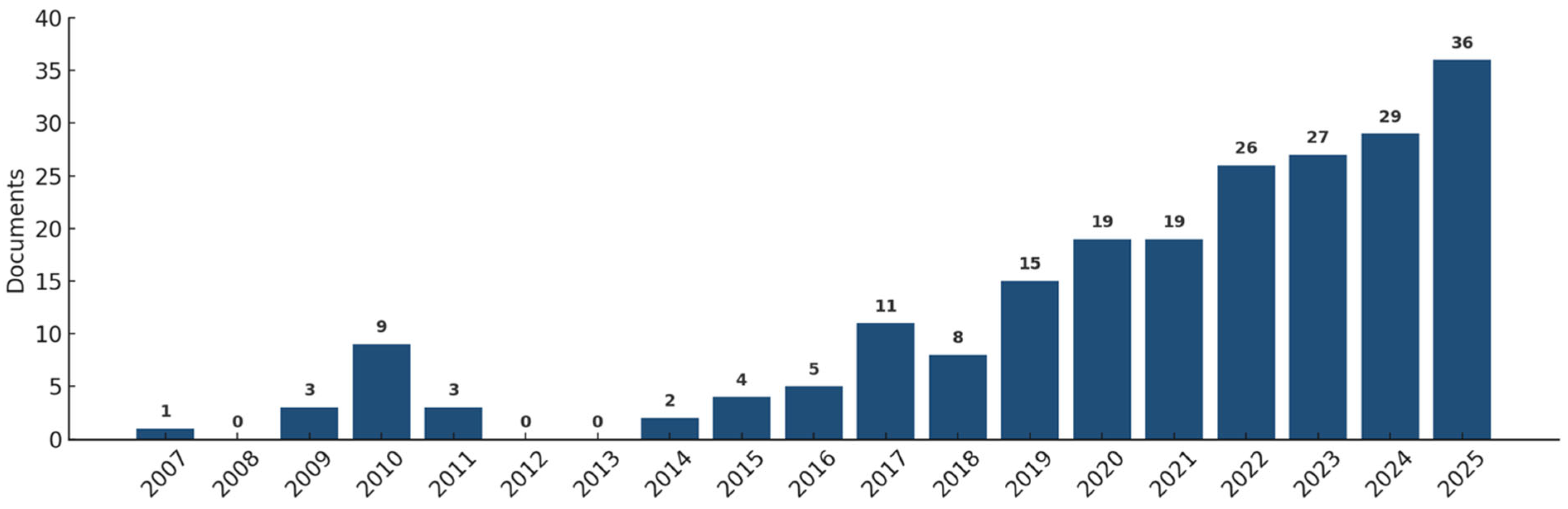

|