Abstract

The contemporary landscape is characterised by overlapping values and pressures, where ecosystem services and cultural spaces are used by diverse categories of users. In fragile contexts such as the Phlegraean Fields in Italy, the exponential growth of mass tourism has intensified the anthropogenic impacts, exacerbated by limited landscape awareness among local communities. Thus, walkability fosters direct exploration, while experiential transects provide a lens to read ecological, cultural, and perceptual layers of places. Together with digital storytelling, these approaches converge in a phygital approach that enriches physical experience without supplanting it. The study covered approximately 115 km of routes across five municipalities, combining road audits, an 11-item survey, participatory mapping, and ArcGIS StoryMaps. Results showed a structurally complex and functionally fragile mobility system: sidewalks are discontinuous, lighting insufficient, less than one quarter of the network is fully pedestrian, and cycling facilities are almost absent. At the same time, digital layers diversified routes and supported situated learning. By integrating geo-spatial analysis and phygital tools, the research demonstrates a replicable strategy to enhance the awareness and sustainable enjoyment of complex landscapes. The present research is part of the PNRR project Changes ‘PE5Changes_Spoke1-WP4-Historical Landscapes Traditions and Cultural Identities’.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Contemporary Landscape Between Mass Tourism and Digital Evolution

The contemporary landscape represents the fundamental hub that connects the processes of building territorial identity with experiences of spatial enjoyment. Depending on how the landscape is structured, it can catalyse infinite forms of experience, amplifying its appeal to users in relation to the scale of the area, its geographical location, and its historical and cultural qualities. These factors can determine the centrality of a certain landscape within the social framework, depending on its aesthetic and cultural values, its inner symbolic character, and the experiences it can offer to the community that uses it. Indeed, it is well-known how strongly social and cultural factors can influence the collective imagination, thereby defining ordinary or tourist practices that are heterogeneous in terms of purpose and modalities [].

A robust body of scholarship has problematised how landscapes are experienced, represented, and governed. Humanistic geography foregrounded the phenomenology of place, emphasising attachment, identity, and the experienced meanings of environments [,]. Cultural-historical perspectives reframed landscape as a symbolic and ideological construct rather than a neutral backdrop, showing how visions of nature are historically produced and politically charged [,]. In parallel, critical urban theory underscored the social production of space, insisting that spatial practices and representations are co-constituted through power, everyday routines, and infrastructures [].

Tourism studies built on these strands by interrogating the mediations that shape the encounter with places. Debates around the tourist gaze argue that mobility, visuality, and expectation configure what is seen and valued [,], while classic and post-classic discussions of authenticity—from the staged authenticity of MacCannell [] to the existential authenticity of Wang []—explain why visitors oscillate between conservationist claims and commodified performances. More recently, the vocabulary of overtourism has sought to update the long-standing problem of limits to growth, re-centring the residents’ well-being and urban liveability; however, critics warn that the term risks diagnostic vagueness unless grounded in measurable pressures and distributive effects [,]. Against this backdrop, the UNWTO notion of carrying capacity remains a necessary—though insufficient—reference that must be integrated with social, cultural, and experiential thresholds [].

Concurrently, the digital turn reframes both participation and interpretation. Scholarship on smart tourism ecosystems and locative media suggests that data-rich platforms, AR/VR, and mobile interfaces hybridise the physical and the mediated dimensions, reconfiguring place attachment and learning outcomes [,]. Narrative cartography extends this by showing how story maps and geospatial narration can connect the micropolitics of everyday mobility with multiscalar readings of territory [,].

Recent works have further advanced this debate by explicitly focusing on the nexus between tourism and landscape transformation. Meneghello [] proposed an integrated framework that critically assesses the ecological, symbolic, and social dimensions of the tourism–landscape relationship, highlighting both methodological challenges and the need for multiscalar approaches. From another angle, Zeqiri et al. [] demonstrated how digital tourism platforms and immersive technologies reshape sustainability practices, calling attention to the ambivalent role of AI and VR in mediating authenticity, accessibility, and governance. These perspectives open promising avenues for linking theoretical insights with operational tools in contexts characterised by high tourist pressure and fragile landscapes.

Comparable advances in digital landscape protection further illuminate this frontier. In China, the Dunhuang Mogao Grottoes have become a paradigmatic case where digital technologies support conservation: recent projects have integrated artificial intelligence for mural restoration [], immersive head-mounted display tours that allow for compelling virtual experiences [], and critical debates on how digital reproduction reshapes the interpretation of ancient art []. These initiatives show how high-fidelity digital surrogates can both limit physical access and expand cultural dissemination, highlighting the dual role of replication and reinterpretation.

In Egypt, research on the Nile Delta demonstrated how remote sensing can be mobilised to track transformations of fragile cultural landscapes. Elfadaly et al. [] combined historic topographic maps with optical and radar data to identify potential settlement areas and monitor archaeological sites under threat. More recently, Elfadaly et al. [] extended this approach to assess environmental pressures in Historic Cairo, demonstrating how satellite and ground data can jointly capture human and natural impacts. These contributions illustrate the methodological innovation of multi-temporal monitoring and the potential of geospatial integration for risk assessment and management.

A different but equally instructive case is the Cosquer Cave near Marseille. Discovered underwater and rendered inaccessible for conservation reasons [], it has been re-presented through a full-scale replica inaugurated in 2022 at the Villa Méditerranée museum complex []. The exhibition combines realistic reconstructions, scenographic design, and immersive devices to redistribute visitor flows ex situ while protecting the fragile submerged cave. This model exemplifies how digital replication and museographic mediation can deflect anthropogenic pressure and sustain public engagement with vulnerable heritage.

Taken together, these three cases underscore distinct but complementary methodological innovations—digital replication, long-term remote sensing monitoring, and ex situ immersive reproduction—that provide comparative insights against which the present study situates its own in situ, phygital approach to landscape valorisation.

In this context, research is converging towards multidisciplinary studies aimed at understanding the extent to which tourist flows influence the very definition of landscape, from a functional and perceptive point of view [,,,], although it is important to focus on analytical and design models and frameworks that can interpret the complexity of the dynamics of mutuality between landscape assets and their use. It is inevitable that tourism exerts considerable pressure on the landscape. The effects can be seen both in quantitative terms, with an increase in visitor numbers, especially at specific moments of the year, and with a growing consumption of resources, and in terms of overall quality.

One example is the real possibility that the identity of places could be gradually eroded by occasional consumers of ecological and cultural amenities, leading to a standardisation of landscape use and undermining the everyday practices of communities that live in these valuable spaces. Mass tourism, in particular, has exacerbated spatial polarisation dynamics, congesting specific landscape hotspots and contributing to the marginalisation of areas that are less accessible or perceived as less profitable in terms of territorial marketing []. In this context, the concept of tourist carrying capacity, introduced by the World Tourism Organisation, is an essential tool for sustainably managing flows, with a view to providing an integrated and multiscale reading of the critical issues and potential of the territorial system [].

This notion is divided into several dimensions—ecological, cultural, social, infrastructural, and organisational—each of which contributes to defining the limits within which it is possible to ensure usage that is compatible with local resources and values. When properly regulated, tourist flows can nevertheless be a lever for urban regeneration and territorial enhancement, promoting investment in green infrastructure and sustainable mobility solutions that improve accessibility to important landscape areas while reducing anthropogenic impact []. The tourist experience thus becomes an opportunity to rethink the balance between use and protection and between promotion and preservation, with a view to integrated development.

In any case, it is important to consider the evolution of methods of enjoying the landscape due to the increasing digitalisation of the tourist experience, which has introduced new ways of accessing and representing the territory. Immersive technologies such as virtual and augmented reality, geo-storytelling tools, and interactive platforms are gradually changing the very experience of visiting places, complementing direct enjoyment with other ways of interacting with the landscape that are parallel to, and sometimes even replace, physical presence []: while on the one hand, these tools amplify the accessibility of cultural and natural heritage even to distant users, effectively removing geographical barriers, on the other hand, they raise doubts about the authenticity of the experience, understood as a direct relationship of knowledge between users and the space they experience.

The emergence of forms of virtual tourism, accelerated by the recent pandemic crisis, marks a paradigm shift that reinterprets tourist space as a hybrid and multilevel environment, in which the experience is mediated, narrated, and georeferenced. Over time, the fragility of the globalised tourism model has been highlighted, opening up new possibilities for a more sustainable and responsible rethinking of tourism, oriented towards community well-being and territorial resilience [,]. However, there is still a need to consider digital tools, in all their forms, as complementary to the physical landscape, rather than as a substitute for it, since knowledge can truly be experienced only in situ. In this sense, there is value in the hypothesis that landscape should not be understood as a mere backdrop to the tourist experience, but rather as a situated epistemic key, capable of broadening the users’ cultural awareness and intensifying their sense of belonging and responsibility towards places.

Therefore, it seems necessary to understand how crossing landscapes can become a means of spatial understanding, in direct contact with the environment but also through new technologies. In this sense, on the one hand, slow mobility practices that follow thematic itineraries are configured as devices through which the landscape manifests itself in its layered complexity as a dynamic palimpsest []; on the other hand, the digital enjoyment of places takes the form of an experiential modality, which while not able to fully restore the importance of direct interaction, can nevertheless integrate the immersive dimension, enhancing the immaterial value of the landscape and acting as a mediating element between meta-sensory narration and spatial enjoyment [,].

1.2. Walkability as a Lens to Understand Landscape Along Experiential Transects

It is worth emphasising how much the configuration of the territory affects the way in which space is used, also depending on the presence of certain significant cultural or physical assets: this brings back the possibility of studying and understanding the landscape through a visual approach based on direct experience of the places. Given the complexity of planning, this could facilitate an understanding of the relationships between users and the environment in which they interact. Landscape areas are in fact a translation of individual perceptions, becoming true commons that condense shared meanings when they are generally shared by the community [].

In line with these premises, the concept of walkability has become increasingly important in urban planning, sustainable mobility, and, more recently, in the understanding of the urban landscape as a form of experiential knowledge: the theory indicates the degree of simplicity with which a service or place can be accessed by foot, with positive impacts on mental and physical health [,].

This concept measures the capacity of a given place to support and encourage the use of space through physical exploration, making it a privileged way of establishing a direct perceptive relationship with landscape assets. This relationship is consolidated through physical actions on site, such as observation, but also through social interaction, constituting the interpretative tools of the landscape itself, and at the same time representing a dynamic experience for the user [].

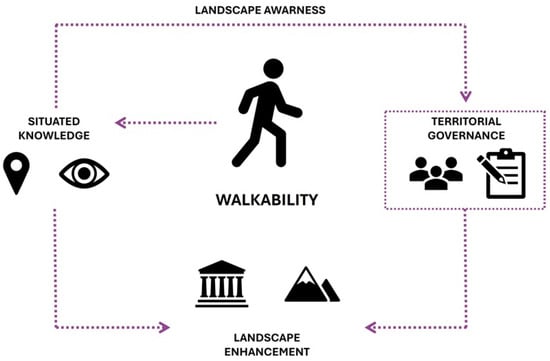

The concept remains a topic for further exploration in decision-making processes, as it can serve as a link between the community’s desires with regard to certain goals, the actual willingness to travel a certain distance to achieve them, and the actual quality of the routes available. In terms of sustainability and social inclusiveness, walkability can describe the extent to which an area supports soft mobility, promoting a fair relationship between distances, times, and accessibility while enhancing not only the value of the assets to be reached, but also the quality of the landscape in which the routes are located (Figure 1) [].

Figure 1.

Walkability may be intended as a way to channel community awareness of landscape in efficient governance and planning dynamics (elaboration of I. Pistone).

The aesthetic, ecological–cultural, and functional characteristics of the landscape are important incentives for the development of walkability, as they influence the sense of comfort and safety when crossing certain places, encouraging place attachment and a propensity for pedestrian exploration, also through the integration of specific landmarks within slow routes in order to implement processes of familiarisation with the context and the visual-sensory experience. These considerations suggest that walking can be intended as a multisensory tool for understanding space, especially in areas with a strong cultural and landscape character as well as for identifying the specific critical issues of places [].

Walkability encodes an experiential mode of movement that rebuilds interaction with the landscape, recognising its characteristic signs, peculiarities, and complexities, quantifying in a certain sense the degree of accessibility to a shared knowledge of places, channelling elements of the community’s imagination of urban experience [].

This is particularly relevant in urban contexts with a rich historical and cultural matrix: the morphology of such places is often favourable to walkability, at least in terms of the inherent environmental and socio-cultural values that can promote an immersive experience in the urban landscape, through the lens of slow mobility as a tool for heritage enhancement and knowledge. However, critical issues such as the physical conformation of the territory as well as growing anthropogenic pressure and related contemporary urban transformations must be taken into account. These are linked to the progressive reduction in spaces intended for pedestrian use to the advantage of increasingly prevalent road mobility, requiring integrated and sustainability-oriented approaches [].

The experience of walking therefore proves to be a cognitive device, which, far from being merely a practical tool, allows for the complexity of material and immaterial values to be grasped: it is thus possible to interpret the landscape through direct interaction, combining the user’s visual-sensory and cognitive experience with the real space and the geographical narrative of the places themselves []. This leads to the need, in the analytical and planning fields, to recognise walkability as a fundamental epistemic dimension, aimed at connecting the assets of the territory in an inclusive and conscious manner. For this reason, it is necessary to implement a dynamic and adaptive pedestrian network within complex landscape areas that is based on temporal, morphological, and socio-demographic factors [].

Since the enjoyment of the landscape depends on spatial knowledge, the landscape matrix of planning strategies can be implemented through the choice of an approach such as the experiential transect (Figure 2). In geography, a transect is a specific method of territorial analysis organised along a linear trajectory: this exploratory procedure requires careful analysis of the various anthropic and environmental elements that contribute to the definition of the landscape structure, studying in sequence the ecological–spatial relationships that connect them [].

Figure 2.

The experiential transect is a tool for understanding the territory in each of its parts, as every movement is linear and involves direct contact with the landscape (elaboration of I. Pistone).

The act of crossing a transect reveals the prior knowledge and perceptions that each observer brings with them, bringing to the fore, on the one hand, their personal wealth of experience, and on the other hand, a set of collective expectations built up through comparison with previous explorations in environments perceived as similar while taking into account differences in socio-morphological composition, economic dynamics, and ecological and environmental issues []. In this sense, the experiential transect can promote integrated involvement with the field of study as well as in relation to the functional links that are established and highlighted [,].

In this context, cultural itineraries, recognised by institutions such as UNESCO and ICOMOS, take on strategic importance as operational and exploratory tools for the landscape: a cultural itinerary is a specific type of asset composed of various elements, tangible or intangible, interrelated in space, and not necessarily characterised by geographical contiguity but fundamental for the creation of a system of knowledge []. In fact, these itineraries can be likened to the notion of transect, as they are essentially linear and capable of activating an immersive cognitive process within a territorial area, integrating themselves into the planning dynamics related to slow mobility and the direct enjoyment of the widespread cultural heritage, activating complex cognitive processes in which sensory perception intertwines with memory and landscape narration. They structure an interpretative experience that combines subjective vision and collective references, constituting a means of communication and cultural exchange, a tool for consolidating identity in a process of reappropriation of the collective landscape [,].

In this sense, the value of cultural itineraries in contributing to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals of the 2030 Agenda is emphasised through forms of responsible tourism that promote social inclusion, the protection of cultural heritage, enhancement of local features, and territorial cohesion. The experience of walking along thematic itineraries can activate forms of situated knowledge, capable of restoring meaning to places and promoting greater awareness of the link between landscape and social identity [].

Walking along these routes is therefore equivalent to embarking on a layered cognitive experience, which develops in continuity with the experiential transect approach: walking through places allows us to understand the landscape in its fundamental parts, which in turn acquire meaning within a network of relationships.

The richness of these experiences lies in their ability to integrate observation, immersive knowledge, and participation, generating widespread awareness that feeds the active consciousness of users [].

In conclusion, the experiential transect tool, applied to the theory of walkability and in the context of cultural itineraries, offers a theoretical and operational opportunity to renew landscape knowledge practices, combining the methodological rigour of territorial analysis with the subjective dimension of direct experience. This integration produces an epistemological model capable of restoring complexity and depth to the study of space, making the landscape not only an object of observation, but a system of cultural, ecological, and social relationships.

1.3. Digital Valorisation in Tourist and Archaeological Regions: The Case of the Phlegraean Fields

Based on these considerations, the Phlegraean Fields, located on the western coast of the metropolitan area of Naples, represent a unique case study due to their unique landscape and geological features (Figure 3). They are the largest volcanic caldera in Europe and the second largest in the world after Yellowstone. From an archaeological point of view, the Phlegraean area is equally significant, as since the Renaissance ruins and remains have emerged almost intact compared with the urban sites found in Rome.

Figure 3.

The case study of the Phlegraean Fields. Despite the proximity to the main city of Naples, this area suffers from scarce accessibility while hosting large number of tourists due to its ecological and archaeological features (elaboration of A. Acierno).

However, in recent decades, the natural integration between socio-cultural and ecological-environmental elements has been progressively overshadowed by widespread urbanisation, which is why the rich natural heritage (consisting of lakes, coastal areas, protected woodlands, various SPAs and SCIs) and cultural values are now highly fragmented and show extensive signs of degradation, exacerbated by a weak mobility network dominated by car traffic, to the detriment of its accessibility by local users and tourists, leading to the deterioration of the interconnections between the key elements of the territory. Added to this is the significant volcanic risk, which is receiving increasing media attention and requires strategic and planning efforts in the medium- and long-term.

The fragmentation of the Phlegraean territory prevents an effective integration of its naturalistic and historical-archaeological areas, with a consequent loss of tourist and cultural value. Alongside the discontinuity of the main emergencies in the area, there is also widespread carelessness that hinders its enjoyment: from the point of view of accessibility, there are paths that are impossible to walk along due to overgrown vegetation, while street furniture is often subject to damage of various kinds, and signage is not always sufficiently visible to guide visitors. Several sites are currently closed to the public, depriving users not only of ecologically valuable spaces, but also of elements of archaeological and identity value.

To situate the Phlegraean Fields within a broader Euro-Mediterranean discussion, evidence from comparable hotspots clarifies both criticalities and responses. In Venice, long-standing pressure from day-trippers and cruise traffic concentrates on a fragile historic core; scenario-based applications of tourism carrying capacity have been used to test mitigation options (e.g., time shifting, pricing, access management) and their governance trade-offs under overtourism [].

In Dubrovnik, where cruise peaks can overwhelm the urban core, a digital response system links capacity calculations to operational measures—time-windowing entries, routing adjustments, and cruise-day management—shifting from static thresholds to adaptive flow control []. On Santorini, in the South Aegean territory, island-scale assessments combine multi-criteria indicators to show how accommodation dynamics and environmental constraints intensify congestion, underpinning proposals for multiscalar monitoring and zoning [].

For Barcelona, recent work moved from overtourism to overall-mobility, using positioning-based data to measure the spatiotemporal weight of residents, commuters, and visitors across the city, thereby reframing policy beyond the simple host/guest dichotomy [].

Collectively, these cases indicate two transferable strategies—measuring and anticipating demand at multiple scales, and diversifying/narrating visitor experience to redistribute attention—that inform the comparative lens adopted here and prepare the ground for the operational choices outlined below.

At a policy level, several European instruments provide a shared context for addressing the challenges of landscape and tourism valorisation. The European Landscape Convention underlines the role of landscape as a socially perceived and evolving resource []. The UNESCO Historic Urban Landscape recommendation promotes integrative and participatory management across natural–cultural layers []. The New Leipzig Charter and the Territorial Agenda 2030 encourage integrated, multilevel spatial strategies and a green–digital transition [,]. In the tourism field, the Transition Pathway for Tourism and the New European Bauhaus stress the links between quality of place, cultural heritage, and digital innovation [,].

In addition, European frameworks for the valorisation of cultural heritage increasingly emphasise the potential of digital tools for accessibility, knowledge sharing, and community engagement []. As a whole, these instruments establish an enabling environment that situates local case studies within wider continental debates on sustainable tourism and heritage management.

In light of these considerations, this contribution, included in the PNRR research project Changes ‘Cultural Heritage Active Innovation for Sustainable Society’—PE5Changes_Spoke1-WP4-Historical Landscapes Traditions and Cultural Identities, aims to define a framework for understanding the Phlegraean landscape and its intrinsic complexity, with a focus on exploring the theme of the direct experience of places in synergy with digital enjoyment of the landscape. The objective is to provide a multilevel interpretation that allows, on the one hand, to understand the Phlegraean Fields not only from a tourist point of view, but also from the perspective of ordinary use by local users, and on the other hand, to broaden the spectrum of information through technological and digital approaches that allow users to further explore the physical landscape, accessing and at the same time implementing the geolocalised database.

Building on these challenges and insights, we now move from diagnosis to operational choices. The next section presents an in situ, phygital approach centred on experiential transects—walkability-based thematic routes—and geo-storytelling. The aim was to couple the embodied exploration with light digital layers (maps and multimedia annotations) to support situated learning and a more balanced spatial use of the area. Because it relies on widely available tools and stepwise workflows, the approach is incremental and replicable: it can start with pilots and expand as data and community engagement grow.

On this basis, the structure of the article is organised as follows:

- Section 1 introduced the theoretical background, reviewing debates on landscape, tourism, and digital mediation, situating the Phlegraean Fields within this framework;

- Section 2 outlines the methodological orientation, focusing on experiential transects, walkability, and geo-storytelling tools adapted to the local context;

- Section 3 presents the results of the application, emphasising the multilayered readings of the Phlegraean landscape that emerged from the integration of physical experience and digital narration;

- Section 4 broadens the perspective by discussing comparative outcomes, linking them to international debates on overtourism, digital heritage valorisation, and European policy contexts;

- Finally, Section 5 draws the main conclusions, highlighting the contribution’s originality and indicating potential avenues for transferability to other coastal and heritage-rich regions.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Conceptual and Spatial Framework

These premises led to the definition of a composite research methodology for the Phlegraean Fields that would allow for the analysis of the landscape complexity by connecting the various elements that make this place unique, in order to enhance them and expand the knowledge and awareness of the local community, exploiting both the exploratory potential of walkability and the digital implementation of the Phlegraean landscape.

In this study, the experiential transect was operationalised as a linear route purposively selected to capture the ecological, cultural, and perceptual dimensions of the landscape through combined observational notes, geospatial layers, and participatory inputs. As a field protocol, the transect enables sequential reading and documentation of place attributes and practices, aligning with established ‘transect walk’ approaches in urban and landscape research [].

For this reason, it is appropriate to refer to a real analytical-operational protocol that defines a methodological framework through which it is possible to develop various narrative outputs that follow the conventional form of the territorial section, albeit through the personal and subjective lens of field exploration: in fact, this feature represents the distinctive and innovative trait of the proposed approach, which, while proposing direct lines of study that connect relevant points in space, maintains the importance of the user’s experience, so that it can enrich the system, and at the same time, enrich the user, who gains awareness of the potential but also the critical issues of the place [].

In parallel with this definition, by phygital approach, we refer to the methodological integration of on-site, embodied exploration with lightweight digital layers (e.g., ArcGIS StoryMaps, Google My Maps, and immersive-ready content) designed to augment—rather than substitute—the physical experience []. The study area covered the municipalities of Pozzuoli, Bacoli, Monte di Procida, and selected neighbourhoods of Naples and Quarto, comprising approximately 115 kilometres of potential experiential transects. This definition of the research field provides the spatial scope within which the methodology was applied.

2.2. Data Collection and Workflow

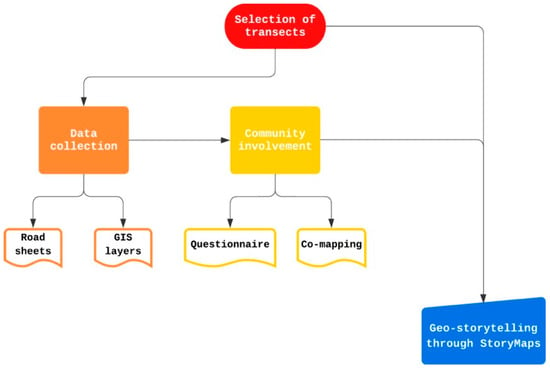

The methodology can be summarised in four steps (Figure 4):

Figure 4.

Methodological flowchart illustrating the sequence of transect selection, data collection, community involvement, and digital integration through StoryMaps (elaboration of I. Pistone).

- Selection of transects according to proximity to cultural and natural hotspots and integration with local planning;

- Data collection through road sheets, GIS layers, and historical cartography;

- Community involvement via questionnaires and co-mapping on Google My Maps;

- Digital integration through ArcGIS StoryMaps, where multimedia layers enrich physical routes with narrative content.

These phases were sequentially designed to ensure transparency and replicability across different contexts. The methodology has therefore identified a number of significant experiential transects of the Phlegraean Fields, in relation to local main hotspots and local planning strategies. Routes were selected solely on the basis of their effective ability to connect landscape and heritage assets—both natural and anthropic—and essential urban services. No additional filters (e.g., slope) were applied at the selection stage; these conditions were recorded through specific GIS tools, such as OpenRouteService, a digital plugin that provides routing alternatives based on terrain conditions and other accessibility features: its usability is also very easy for non-expert users (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Map of the studied transects (in red) in the study area (in blue) (elaboration of I. Pistone).

Using dedicated road sheets, the main features that influence the functionality and connectivity of the soft mobility system were mapped as well as the actual attractiveness of these connections for users. Specifically, the analysis covered the key physical–perceptual characteristics of the identified transects—dominant use (pedestrian or vehicular), state of maintenance, and existing surfacing—alongside the presence and typology of sidewalks (one- or two-sided, continuous, or intermittent). The study also included dedicated cycling facilities and the degree of pedestrian usability as well as prevailing traffic regimes and the presence and upkeep of bus stops. In parallel, factors affecting the liveability of the experiential transects and their perceived safety were examined, notably lighting adequacy, visible signs of physical decay, and the diffusion of informal safety measures.

Building on these audited attributes, in order to spatialise the network of local landscape assets and categorise the different ways in which they can be enjoyed, the research implemented a spatial data model. This tool, which is related to geographical disciplines, allows information related to a physical space to be georeferenced, classifying its various components into geometric objects with precise spatial features, which are useful for describing the distribution of elements and their functions across the territory as well as the attributes that describe their main properties [].

In this context, the use of such an instrument has significant strategic implications, as it proves very useful for analytically addressing the issue of accessibility to certain assets, identifying the services and places of greatest interest within a given radius of action []. The methodological approach focuses on defining significant experiential transects to promote walkability as a fundamental cognitive element.

For this reason, the present spatial data model explored the needs of soft mobility in more depth, in line with the dynamics of sustainable planning from both an ecological and social point of view. This promotes community autonomy, favouring pedestrians in denser urban areas, where numerous critical issues are linked to inadequate road infrastructure, the growing number of functional requirements, and the orographic and physical conditions of the terrain. Keeping in mind safety and usability as the main requirements for an adequate landscape experience system, the structure of the spatial data model was then divided into groups of layers, as summarised below:

- Basic layers. These include aerial photogrammetry, various types of maps, and three-dimensional models dating back to different periods. These are useful for comparing the current situation with the past, but also for mapping the spatial data of the next layers.

- Legal constraints. They highlight the main normative documents that influence and regulate the ways in which transects and the mobility system in general can be enjoyed as well as the spaces and assets they connect. Reference is made to constraints related to environmental risks, but also to ecological constraints and limitations on vehicle accessibility and traffic as well as the actual possibilities of accessing landscape assets.

- Local main hotspots. They identify the most relevant points of interest in the reference area. Since dense city areas offer a number of services that are often scattered throughout the urban landscape, it is important to understand the actual location of the places that residents, commuters, and tourists tend to visit, as this can lead to challenges related to an overloaded and not always adequate accessibility and service network.

- Mobility system. This indicates the more or less extensive network through which users can reach the local main hotspots, either by road or rail as well as by slow and sustainable means of transport. Parking spaces for cars and motorcycles are also identified as well as spaces for bike sharing and electric scooter rental.

This sequential design aimed to ensure transparency and repeatability, following established protocols in participatory GIS. The experiential transect thus translates into the selection of potential itineraries that can facilitate an understanding of the Phlegraean landscape, with a view to soft mobility but also to enhance its unique features. In this regard, the geospatial study is enriched by appropriate collaborative mapping actions aimed at expanding the database and involving users in the analytical and operational processes.

The community has also been involved through specific surveys aimed at listening to demands and desires regarding the evolution of the Phlegraean area as well as possible suggestions for improvement. Starting from March 2024, an anonymous 11-item questionnaire was administered via Google Forms between March and June 2024, with the aim of capturing the users’ experiences in the Phlegraean Fields.

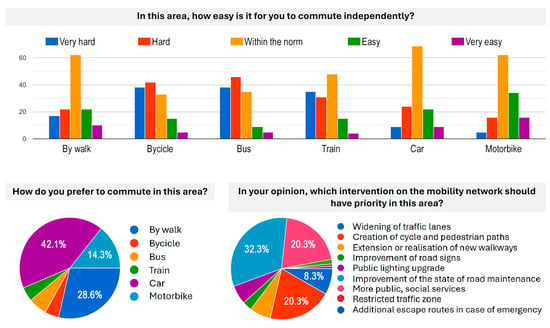

The instrument was structured into three subsections:

- 1.

- Mobility and fruition of the socio-cultural assets, focused on modes of travel, access to cultural and ecological assets, perceived ease/difficulty of reaching places, and on-route constraints; this domain was assessed through the following survey items:Q1. In this area, how easy is it for you to commute independently?Q2. How do you prefer to commute in this area?Q3. In this area, how do you rate the accessibility to the main social services (green spaces, municipal offices, schools, museums, libraries, post offices…)?Q4. In this area, how do you rate the accessibility to the ecological and cultural assets (archaeological sites, parks, beaches, lakes…)?Q5. In this area, how do you assess the availability of public parking spaces for motorbikes and cars?

- 2.

- State of the connection system and future scenarios, centred on the condition and continuity of the connection network, perceived priorities for improvement, and preferences regarding near-term interventions and desirable developments, detailed through the questions listed below:Q6. In this area, how do you assess the maintenance condition of roads?Q7. If the cycle-pedestrian mobility in this area were to be improved, would you prefer it over traditional road transport (cars and motorbikes) for commuting?Q8. How would you like this area to evolve over the next 5 years to improve socio-cultural and functional values?Q9. How would you like the mobility system in this area to be improved over the next 5 years?Q10. In your opinion, which intervention on the mobility network should have priority in this area?Q11. In your opinion, on which roads in this area would it be most urgent to intervene to improve local accessibility to social services and ecological–cultural assets?

- 3.

- Personal information, for sample characterisation, capturing age, gender, municipality of residence, and employment status; responses were collected anonymously and analysed in aggregate form.

Items were predominantly closed-ended and Likert-scale based, in order to optimise comparability and enable straightforward quantitative synthesis across respondents and locations; selected prompts invited short textual notes to contextualise closed answers.

Dissemination combined institutional social media channels (to reach residents, commuters, and visitors already engaged with local institutions) and on-site intercepts carried out at hotspots associated with cultural–ecological assets across the involved Phlegraean municipalities (Pozzuoli, Bacoli, and Monte di Procida). Participation was fully anonymous, and no personal identifiers were requested. The platform has remained active beyond this period, allowing additional responses, but the analysis presented in this article refers exclusively to the data gathered during the initial March–June 2024 window.

The questionnaire therefore provided a concise, standardised evidence base on everyday mobility, access to socio-cultural assets, and expectations for the evolution of the local connection system, complementing the field audits and geospatial analyses.

Quality control was then addressed by triangulating data sources: in situ observations were systematically compared with the survey results and iterative updates of the collaborative mapping platform. This strategy mitigated biases and strengthened reliability, in line with best practices for assessing volunteered geographic information [].

Tools to strengthen knowledge of the landscape have therefore been implemented through GIS-based tools that combine the analytical-planning component with experiential-participatory involvement through the creation of digital geo-storytelling. This concept brings the principles of ‘urban storytelling’ to the scale of the local spatial context, transforming geographical data and maps into real interactive stories. This results in narratives in which different multimedia data are integrated to provide a better understanding of spatial relationships, environmental phenomena, historical, and socio-cultural processes [].

ArcGIS StoryMaps (through the app ArcGIS Online) was adopted as the primary platform for digital integration. Beyond a mere dissemination tool, StoryMaps was operationalised as part of the methodological workflow, enabling spatially anchored interpretation of cultural and ecological elements along the identified transects. The mapping platform organises in fact geolocated information relating to identified landscape assets, through which users can deepen their knowledge of the place, guided in an informed and engaging way [].

The platform acted both as a visualization interface and as a participatory data-collection environment, reinforcing triangulation with field audits and survey responses. Within this framework, StoryMaps supported phygital integration by linking embodied exploration with lightweight digital augmentation while simultaneously serving as a medium of participatory cartography [,].

Such an approach aligns with the principles of citizen science, which emphasise the value of non-expert contributions for enhancing geographic knowledge and for co-producing data on accessibility and landscape dynamics [,]. By linking embodied transect visits with digital storytelling and volunteered inputs, the methodology reinforced both the experiential and collective dimensions of landscape interpretation.

In practice, on-site exploration was augmented through lightweight AR/VR-ready narratives and StoryMaps interactions that supported situated learning and informed route choices without displacing physical engagement []. Concretely, the phygital layer:

- Provided pre-visit orientation and in situ prompts to reveal latent features;

- Enabled temporal comparison (past/present) via swipe maps and multimedia narratives;

- Diversified flows by suggesting alternative micro-itineraries away from congested hotspots;

- Collected geotagged user feedback to iteratively refine the transects within the participatory GIS workflow [].

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Analysis and Experiential Engagement for a Phlegraean Geo-Database

The application of the research methodology led to the definition of a geo-database for the landscape of the Phlegraean Fields.

The reflections presented here are clearly linked to the unique conditions of this landscape, and in particular to the complexities inherent in its management: despite the presence of important institutions and authorities responsible for heritage and environmental protection, the Phlegraean landscape is still largely in a state of spatial and functional disorder.

Regardless of existing strategies to enhance the ecological and cultural networks, fragmentation is still one of the distinctive features of the study area, making it difficult for the average user to understand and appreciate it. The use of footpaths is often inhibited as well as visits to several local archaeological sites. There is therefore a need to corroborate basic knowledge with technical data and experiential insights: this would clearly have a positive impact on both the citizens who live in these places on a daily basis and on the tourists who could enjoy this unique landscape in a more efficient and responsible manner.

In accordance with the criteria established by the theoretical premises and methodological approach, approximately 115 linear kilometres of the Phlegraean mobility network were analysed, mainly in the municipalities of Pozzuoli, Bacoli, and Monte di Procida, together with Napoli (specifically, the neighbourhood of Agnano) and Quarto (over a small audited base): intended as possible experiential transects, these road sections connect cultural and environmental assets with each other as well as basic services.

The logic was to study the use of the landscape in a broad sense, considering on the one hand, the riches and attractions of the area, and on the other hand, the common functions that serve both the everyday lives of the citizens and occasional visitors. Various attributes of the network linking the Phlegraean hotspots were surveyed in situ in order to understand the route quality and actual efficiency.

Regarding the overall network condition and surfacing on the audited network, the evidence points to a system that is structurally adequate but functionally fragile for slow mobility. Results show that overall maintenance was split almost evenly between good (about 47%) and average (roughly 48%) conditions, with only just over 5% classified as poor. This profile indicates that the main barrier to pedestrian-oriented fruition does not lie in generalised degradation, but rather in the design and equipment deficit of many links. Surfacing confirmed a marked material homogenization, with most of the routes composed of asphalt (almost 84%), and only a reduced percentage made of different materials (cobblestone ≈ 10%, other ≈ 6%).

Differences in municipal patterns appeared: in Agnano, the analysed road system is effectively all asphalt; in Pozzuoli and Monte di Procida, it still retains a considerable cobblestone share; in Bacoli, it is nearly 88% asphalt with limited cobblestone; and Quarto mixes asphalt with a sizeable other category. While standardisation aligns with routine maintenance, it progressively erases historical textures and reduces the sensory cues that support wayfinding and identity along experiential transects.

Pedestrian space emerged as the primary bottleneck. Sidewalks are present along approximately 67% of the network by length, but what really makes the difference is whether they run without interruptions and whether they are provided on one or on both sides of the street: about 38% of streets have sidewalks on both sides, 20% on just one side, 9% are intermittent, and roughly one-third have none at all.

To provide an overall picture, we calculated a continuous sidewalk availability (CSA) score, a length-weighted measure in which each street segment was assigned a value depending on sidewalk continuity—the maximum score (1) is given when sidewalks are present on both sides, half (0.5) when only on one side, lower (0.25) when they are intermittent, and zero when absent. We obtained a CSA value of around 0.504, roughly half of what would be expected in the ideal case, where sidewalks run continuously on both sides of the street—consistent with the recurrent interruptions observed on the ground and the difficulty of defining continuous and legible itineraries that connect ecological–cultural assets with everyday services.

Looking at the spatial patterns, Agnano showed the best results with sidewalks on both sides of the streets. Pozzuoli also had a relatively high share of two-sided sidewalks, though these were often broken by interruptions. Bacoli and Monte di Procida stood out for having long stretches with no sidewalks at all, while Quarto included only a few audited streets, which were short but generally well-equipped.

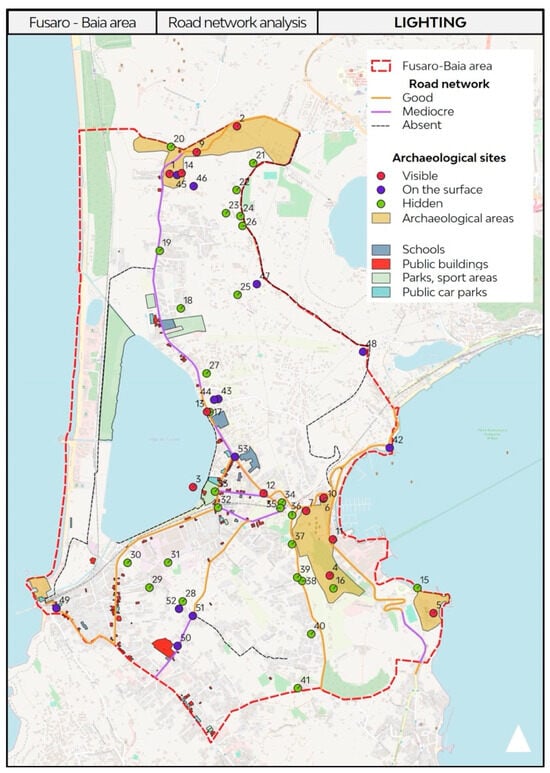

Safety-related equipment compounds these constraints. In terms of street lighting, only about 11% of the audited transects could be considered good, roughly 52% was in average condition, while a reduced share of 8% was recorded as poor, and a consistent third (31%) had no lighting at all. For a broader view of these issues, we introduced the illumination adequacy index (IAI), another length-weighted score: each street segment was scored according to whether lighting was good (1), average (0.5), poor (0.25), or absent (0). The resulting score of about 0.37 was well below half of the level needed to ensure safe walking after sunset and during the periods of the year with shorter days, like winter or autumn, when natural light is limited.

The municipal gradient was sharp: Agnano and Quarto showed comparatively higher adequacy (IAI around 0.68–0.71), Pozzuoli and Monte di Procida sat at intermediate values, while Bacoli was weak, with an IAI near 0.16 and roughly two-thirds of routes unlit (67%). Since perceived safety strongly influences slow-mobility choices [], the result is a fragile user experience after dusk, precisely where a place-based reading of the landscape would benefit from more safely usable time.

Overlapping deficits cluster risk and erode the legibility of the transect network. Segments that are simultaneously unlit and without sidewalks affected almost 14% of the audited length; beyond that, there were other unlit sections where sidewalks were discontinuous (1%) or present on only one side (9%), and stretches with sidewalks on both sides (7%): in these cases, the binding constraint was lighting. The evidence highlights three critical conditions: unlit links without sidewalks, one-sided or intermittent sidewalks on key streets linking cultural sites and everyday services, and junctions where crossings are unclear—contexts in which transect continuity and perceived safety were most compromised (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Example of the graphic representation of road sheets related to the Fusaro-Baia area, showing the existing degree of public lighting. The routes are linked to the presence of services or ecological–cultural assets, simply numbered in the map for identification (elaboration of I. Pistone).

When looking at accessibility, less than a quarter of the audited network (about 23%) could be considered fully pedestrian, roughly 48% offered only limited fruition, and close to one-third provided no real pedestrian accessibility at all (approximately 29%). Cycling facilities were nearly absent: dedicated lanes covered just over 1% of the routes studied, concentrated almost entirely in Bacoli where they reached about 3% of the municipal length and appeared only in isolated lakeside stretches, with a width between 450 and 500 cm, rather than as a systematic provision.

The system is largely structured for car circulation, with nearly 74% of the network operating as two-way streets, around 17% as one-way, and only small shares were either traffic-free (about 6%) or subject to restrictions (just over 3%). Looking at each municipality, the same trend appeared: Agnano was almost entirely two-way; Quarto still preserved car-free pockets equal to about 22% of its streets; Pozzuoli combined a two-way base with a non-trivial share of one-way segments, while Bacoli and Monte di Procida displayed more mixed regimes. Public transport coverage was equally uneven. Bus stops were present along 37% of the audited transects; where present, and even where they exist, their condition is often unsatisfactory: in almost half of the cases, maintenance was poor (45%), about 40% were in average condition, and less than 15% could be rated as good.

Differences among cities were marked: Agnano showed the highest concentration of stops (approximately 72%) but with mostly average or poor upkeep; in Pozzuoli, almost half of the network had stops (48%), even if most of them were poorly maintained (around 62%); Bacoli had fewer stops (about 21%) but with relatively better conditions. Monte di Procida had bus stops along about 38% of its audited network, most of which were in average (48%) or poor condition (37%), with only a small share rated as good (15%); Quarto showed a similar presence, close to 39%, but with much better quality: more than 70% of stops were well-maintained while the rest were poorly maintained.

The outcome is a weak first- and last-mile connection, which undermines intermodality and reduces the attractiveness of public transport in areas already marked by strong car dependence

Beyond routine maintenance, perceived safety shapes slow-mobility choices and the willingness to linger. Signs of physical decay were visible along roughly 40% of the audited network, driven mainly by surrounding abandoned areas (about 48%), followed by graffiti (just over 28%) and illegal dumping (almost 17%). The share of transects characterised by signs of degradation was very high in Napoli and Quarto, with values of approximately 91% and 78%, respectively. On the other hand, Pozzuoli had an intermediate score of almost 54%, while lower values were recorded in Monte di Procida (about 31%) and Bacoli (about 19%). Where signs of physical decay, poor lighting, and missing sidewalks coincide, perceived danger rises, and people tend to avoid those specific routes.

Informal safety measures, such as CCTV, gates, private security, and alarms, covered about 48% of the total audited length. In Napoli, Agnano showed very high coverage (approximately 89%), with gates as the prevailing form of informal defence (84% of the applied measures). Monte di Procida also exhibited a wide share of 81%, but here, private security prevailed (about 83% of the applied measures), consistent with a more residential and commercial local fabric. Pozzuoli featured a distribution value of 46% with a CCTV-centric profile (almost 60% the applied measures), while Bacoli recorded a lower general rate of 35% and a more mixed configuration, with measures such as gates standing at just below 40% and CCTV at 25%. Quarto had an overall share of 54%, where this number was composed of 51% for CCTV, 28% for gates, and 21% for private security.

From a design standpoint, these figures suggest that passive technological mitigation has often replaced active urban management (e.g., continuous sidewalks, decent lighting conditions), with ambiguous effects on the subjective experience of safety.

Street-level frontages align with this picture: hard/passive edges (high walls and fences) exceeded about 34% (around 40% including opaque glazing), whereas active edges—street-facing shops or offices and transparent glazing—amounted to only 14% overall (higher in Pozzuoli and Monte di Procida, scarce in Bacoli). In practice, hard frontages, visible decay, and weak lighting reduce social legibility and the likelihood of walking in quieter hours, limiting opportunities to appreciate the landscape in a more relaxed setting.

Spatial heterogeneity emerged as a decision-relevant matter. At the network scale, indicators point to a system that is usable but under-equipped (CSA about 0.50; IAI about 0.37). Within this, local profiles diverged: Bacoli concentrated the only continuous cycling layer (roughly 3% of municipal length, lakeside), meaning that continuity is largely confined to that corridor. Monte di Procida showed the highest share of streets without sidewalks (almost 56%), indicating foundational gaps on steep residential routes. Pozzuoli coupled a relatively high two-sided sidewalk share (46%) with many interruptions (approximately 18% along the analysed transects), so discontinuity rather than outright absence emerged as the main constraint. In Napoli (Agnano), comparatively higher lighting (IAI about 0.68–0.71) coexisted with clusters of hard frontages and decay, which appeared to weigh more on perceived safety than illumination itself. Quarto preserved car-free areas, with a value of about 22%; their effective use appears to depend on lighting continuity and sidewalk provision.

Orography can also be considered as a structural constraint. The caldera morphology, steep local gradients, abrupt elevation shifts between crater rims, tuff slopes and coastal areas, together with the fine-grain micro-relief typical of volcanic landscapes, amplify the cost and difficulty of delivering efficient equipment along the main territorial links. Tough gradients discourage walking on uphill routes even where infrastructure exists, and long detours to avoid steep segments often conflict with the shortest-path logic of everyday trips. Exposed ridgelines and wind corridors can degrade thermal comfort and social presence at off-peak hours, further reducing perceived safety.

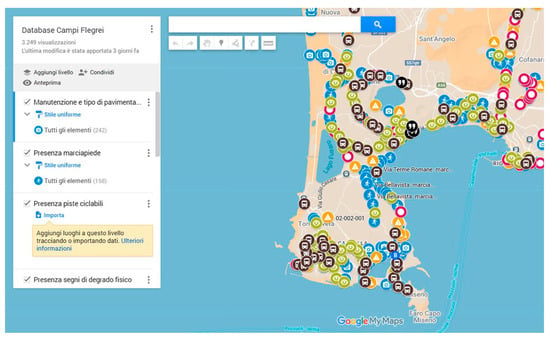

In order to promote forms of experiential engagement with the Phlegraean landscape on the one hand, and to improve the quality of the geo-database on the other hand, user participation is essential through the use of digital co-mapping techniques [,]. The validation of such data as well as their progressive updating thus requires the effective involvement of the community, which is called upon to actively suggest hypotheses and express needs as well as expand its own knowledge of the Phlegraean area.

To this end, a Google My Maps platform has been set up; following this, the data were refined in the processing phase and can be further updated in relation with the feedback collected. Users noted down their personal impressions, preferably in photographic form with supporting notes, and shared their non-expert knowledge, which is essential in providing an accurate and up-to-date picture of such a complex and varied landscape.

Operationally, co-mapped contributions were ingested as attribute updates and points of interest (e.g., sidewalk gaps, unlit stretches, decay sightings, bus stop conditions), underwent quality control and moderation, and then triggered incremental recalculations of composite indicators and logical filters (e.g., segments simultaneously unlit and without sidewalks). In this way, the platform works as a two-way channel that supports micro-audits, the sequencing of interventions, and ex-post evaluation of the delivered actions.

Co-mapping outputs also serve as one of the siting criteria for the phygital layer detailed in Section 3.3, while Section 3.2 folds in social perceptions to check priorities against community preferences. The result is a living, participatory geo-database that couples objective measurements with situated, experiential knowledge, improving both the legibility and the governance of the Phlegraean landscape (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The co-mapping platform elaborated for the research on Google My Maps. Users pinned elements divided by categories, considering the sidewalk presence and conditions (with blue symbols), signs of physical decay (in yellow), the perception of defence strategies (in violet), the presence of windows or fences facing the road (in green) and the presence and maintenance of bus stops (in black) (elaboration of I. Pistone).

3.2. Social Perceptions of Mobility and Landscape Accessibility

Section 3.1 described a network that is usable but under-equipped along the audited transects: the backbone exists, but continuity, legibility, and care remain insufficient to sustain confident walking and cycling beyond peak hours or tourist cores. Building on this evidence, Section 3.2 shifts to a perception-based analysis, aimed at testing and refining the geo-spatial diagnosis. This approach is valuable not only for capturing the specific needs and representations of the community regarding accessibility, but also for involving citizens as active users within a complex framework. It allows for a diverse set of respondents to express priorities, thereby generating knowledge exchange and enhancing the perceived usability of spaces.

In addition, it provides planning institutions with inputs that are aligned with the users’ priorities while relying on a reduced but representative sample. Following the notion of representativeness, as reported by de Singly [], even a relatively small group can produce empirically robust insights, provided its composition reflects the local context in relation to the phenomenon under study. By integrating mapped attributes with expressed needs, the survey thus functions as a triangulation layer: it validates where patterns converge—such as the importance of care and continuity—and adds nuance where perceptions diverge. The result is an operative reading that moves from what the network is to what the community can and wishes to do with it, thereby setting a clear agenda for the phygital dimension addressed in Section 3.3.

Between March and June 2024, 133 people completed the survey. The sample showed a near gender balance, with about 57% women, roughly 42% men, and about 1% other. In terms of age, the largest share of respondents was between 20 and 40 years old (about 57%), followed by those between 40 and 60 years old for roughly 26% of the sample, while the over-60s were about 11%; and the under-20s were only 7%. As for the occupational profile, employees were the largest group (about 42%), followed by students (roughly 29%), self-employed (about 14%), unemployed (roughly 9%), and retirees (about 5%). As for residence, almost half of the respondents lived in the three Phlegraean municipalities (23% in Pozzuoli, 15% in Monte di Procida, 12% in Bacoli), roughly 11% in Naples, and the remaining share resided in other areas. In short, the dataset blends everyday local users with a non-negligible share of external stakeholders—useful for reading both routine needs and visitor expectations.

On mobility habits (Q2), the questionnaire revealed a dual pattern. Private cars remained the most chosen option (about 42%), but walking ranked second (roughly 29%), ahead of motorbikes (about 14%); bus, bicycle, and train each collected about 5–6%. When we compared this preference with perceived ease in independent commuting (Q1), a tension appeared across different modalities. The share rating for mobility as easy or very easy was about 24% for walking, roughly 23% for car mobility, and about 38% for motorbikes, while bicycle use was approximately 15%, the train option reached 14%, and bus about 11%. Essentially, people enjoy walking and driving but find neither option consistently convenient; easiness peaked (relatively) with motorcycles. This gap highlights unmet conditions—equipment continuity, safety, comfort—that currently penalise slow mobility even where it is preferred.

Perceived accessibility was cautiously negative. Regarding social services (Q3), responses clustered at the middle but tilted to the low end. Almost 16% judged accessibility as very poor, and approximately 20% as poor. The majority, about 40%, opted for the middle value, thus signalling a perception of average accessibility. More positive views were less frequent: approximately 17% considered accessibility good, while only about 7% rated it as very good. The analysis of accessibility to ecological–cultural assets (Q4) showed a very similar picture, with a slightly worse balance. About 14% rated accessibility as very poor (score 1), and roughly 25% judged it poor. A further 35% opted for the middle value, indicating an ‘average’ situation. On the more positive side, about 17% considered accessibility good, while only 10% rated it as very good. These data were consistent across everyday services and heritage and natural sites: many places are reachable, but too often under conditions perceived as difficult or less than ideal, which erodes the willingness to rely on soft mobility to experience these landscape elements.

Two structural weaknesses emerged clearly, helping to explain why car use was common but unsatisfying. First, parking availability attracted strong criticism (Q5). More than one third of respondents (about 38%) assigned the lowest score (very poor), while an additional 29% judged it simply as poor. Around 23% selected the midpoint, indicating an average condition. Only 8% considered parking provision good, and a mere 2% rated it as very good. The condition of road maintenance also elicited critical evaluations, though with a more even spread across categories (Q6). Roughly one fifth of the sample (21%) rated it very poor, and about one third (32%) considered it poor. Another 30% settled on the middle value, suggesting neither clear satisfaction nor outright rejection. Positive assessments were less frequent: about 14% described road maintenance as good, and only 3% as very good. These findings clarify the paradox observed earlier: poor surfaces and limited parking foster continued car reliance but little satisfaction, while fragile pedestrian infrastructure keeps walkability low, even for willing users.

Importantly, the survey captured a conditional availability to change. When asked whether they would give up cars and motorbikes if cycle-pedestrian mobility were improved (Q7), only a very small share of respondents, about 3%, declared that they would not at all be willing to do so, and roughly 11% said only a little. Around 23% positioned themselves as indifferent, signalling uncertainty rather than clear rejection or acceptance. On the more positive side, 20% affirmed that they would be quite willing to substitute slow mobility for traditional transport, while the largest group (about 44%) expressed that they would be very keen to make this change. Taken together, the distribution revealed that opposition is marginal, indecision concerns about one in four respondents, and a clear majority—well over sixty percent—would actually be ready to replace traditional motorised transport with walking or cycling if adequate infrastructures were provided. This evidence suggests that slow mobility cannot be seen as a purely aspirational behaviour. Rather, it represents a conditional choice, with respondents willing to change if adequate infrastructures were guaranteed. From a policy perspective, the sequence is clear: fundamentals must be secured first, and only then can integrated slow-mobility networks be successfully implemented.

Preferences regarding the medium-term evolution of places and transect systems confirmed the same hierarchy of priorities identified earlier. With regard to future socio-cultural and functional evolution (Q8), the most widely supported options were those oriented to everyday public life. New recreational spaces such as squares, outdoor sport areas, or bathing facilities received the highest approval, with nearly four out of five respondents (about 78%) expressing strong or very strong interest. Close behind, new public green areas attracted broad consensus (roughly 73%), while outdoor archaeological-ecological visiting paths also garnered significant support (about 67%), together with new museums and cultural centres (around 65%). Sports infrastructures, including gyms and swimming pools, were likewise seen positively, with almost two thirds of the sample (about 64%) in favour. In contrast, proposals for expanding commercial areas gathered only limited enthusiasm, with fewer than four respondents in ten (roughly 39%) supporting them, and a similar share supported the creation of new accommodation facilities (about 40%). The overall picture is therefore one of clear preference for open-air, culturally anchored civic spaces, perceived as capable of both diffusing pressure from overcrowded hotspots and improving the quality of everyday urban life.

In relation to possible improvements to the local mobility system (Q9), respondents expressed clear preferences that reflected a strong orientation towards inclusivity and basic maintenance. The introduction of disability aids such as tactile maps, ramps, or Braille information gathered the highest consensus, with about 71% of the sample declaring themselves strongly in favour. Almost the same share highlighted the need to improve road maintenance, while the creation of new cycle and pedestrian paths was also widely supported, attracting 68% of positive responses. Slightly lower, though still significant, was the endorsement for extending or realising new sidewalks, indicated by around 63% of participants. Other measures, while not ignored, were considered somewhat less urgent: the upgrading of public lighting was favoured by approximately 60% of respondents, and improvements in road signs by roughly 54%. In contrast, the widening of traffic lanes received the lowest support, with fewer than half of the respondents (about 49%) considering it a priority.

On the question of which measure should be given priority (Q10), responses showed that the hierarchy remained consistent but became sharper. The improvement in road maintenance emerged as the leading option, chosen by about one third of the sample (32%). Two other measures shared second place, each gathering around 20% of responses: the introduction of disability aids and the creation of cycle-pedestrian paths. All other interventions attracted much lower percentages: the widening of traffic lanes was mentioned by about 8% of respondents, while sidewalk extension by roughly 7%; lighting upgrades were a priority for approximately 6% of the sample, and better road signs for only 3%.

Taken together, these results show a very clear pattern. The community identified the care and continuity of the existing network as the essential foundation; it is only once these basic deficiencies have been addressed that the respondents will prioritise inclusive and slow-mobility infrastructures. Road capacity enhancements, in contrast, did not rank among the main expectations (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Some of the results of the social survey. Slow mobility is a strong desire of the community but there is also the priority of maintaining the routes (elaboration of I. Pistone).

The open-ended responses on the roads perceived as most in need of intervention (Q11) were diverse in form but converged on a limited set of priorities. Many participants pointed to coastal and connector routes—such as Via Domiziana, Via Miliscola, Via Panoramica, Via Bellavista, Via Castello, and the waterfront areas of Pozzuoli and Baia—as the places requiring urgent attention. The problems most often mentioned related to the poor state of maintenance, with potholes and degraded surfaces, but also to the absence or discontinuity of sidewalks, insufficient lighting, heavy traffic and parking conflicts, and the lack of safe cycling continuity. Some respondents also underlined the need to improve public-transport access to archaeological sites like Cuma, Baia, and the Solfatara area, stressing that current bottlenecks limit cultural potential. Considered alongside the closed-ended questions, these insights outline a pragmatic agenda centred on continuous and well-lit pedestrian routes, safer routes, and systematic care along the very streets most commonly used in daily routines.

Overall, the questionnaire portrays a community that values walking and the enjoyment of open-air cultural assets but faces daily constraints generated by fragmented infrastructures and a long-standing reliance on cars. Compared with the field audits, perceptions emerged as coherent in direction but more pronounced in tone: respondents highlighted physical deficits, recognised the persistence of unresolved maintenance issues, and directly linked these shortcomings to their everyday mobility choices.

3.3. Phygital Approach to Amplify Landscape Fruition

Building on the spatial analysis of transects (Section 3.1) and the survey of community perceptions (Section 3.2), this third set of results focused on the integration between physical exploration and digital narration. In this perspective, the phygital approach works as the operational hinge that translates network evidence and social expectations into an experiential framework, where walkability and cultural awareness are amplified by interactive tools.

The physical crossing of space, the awareness of dimensions and orography, shapes, and distances is an irreplaceable direct exploration for knowledge, but the landscape in its broadest (and most complex) sense is not limited to the space inhabited by physical action as it activates ever-changing multisensory perceptions, memories, and interpretative keys filtered through individual and collective knowledge. The experience of spatially crossing a landscape can be considered as the interface that enables contact between the physical, material object (i.e., places) and its changing perceptions, individual, and historical memories, activating an emotional aspect that constitutes the immaterial part of the experience.

If the experience of landscape is implemented through digital content, the typical linear flow of narration activates a network of possible points of knowledge to be interpreted and connected according to one’s personality and sensitivity. The phygital space, understood as a physical space blended with the digital, provides an experiential microsphere in which people, acting physically in places and interacting with digital content, increase their ability to connect with the immaterial aspects of landscape exploration. The journey thus becomes a physical performative act that is indispensable for the knowledge and creation of narrative storytelling, unique to each exploration as it is independently decided through the multiple choices made possible by nonlinear interactivity with digital content.

The implementation of digital content can guide the physical experience of traversing space, highlighting latent aspects, recalling historical memories, bringing out distinctive features that are not immediately apparent, and thematically intertwining distant physical places through a guided journey of discovery. The augmented, immersive, and virtual exploration of the landscape can transform physical spaces into places of narrative that transcend and coexist with the limits of material reality.

In particular, in highly stratified historical landscapes such as the Phlegraean Fields, the cultural heritage of a community is characterised precisely by that inseparable link between its material component, which roots it to the territory, and its immaterial dimension, capable of arousing imagination and attributions of value. This dual nature, intertwined with the temporal dimension of history and anthropogenic transformations of the territory, contributes to defining its uniqueness. At the same time, the design and creation of digital content for a phygital experience require representation strategies that are able to hold together the complexity of all of these aspects.

This perspective directly responds to the equipment gaps measured along the transects and to the priorities expressed by the community. The research therefore aimed to design a phygital space for the Phlegraean Fields that is capable of communicating the inseparable intertwining of the natural ecosystem, its representation, and the sedimentation of historical and cultural processes.

Today, new models of territorial enhancement are constantly determined and conditioned by rapid advances in digital technology. The very notion of enhancement is undergoing a profound renewal thanks to the opportunities offered by new representation and communication technologies. In particular, for the Phlegraean Fields, the problem of the physical fragmentation of the landscape has been repeatedly highlighted, which is difficult to overcome with specific and targeted interventions. In this context, digital representation can be an effective strategy for re-establishing narrative links between places, artefacts, and landscapes in order to rebuild relationships with local communities on the basis of emotional and interactive experiences, supporting the creation of a flexible digital network of spaces, data, and information that are located in equally fragmented and distant physical contexts.

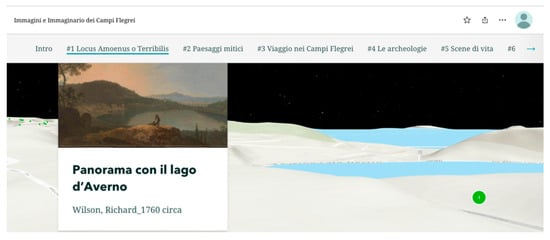

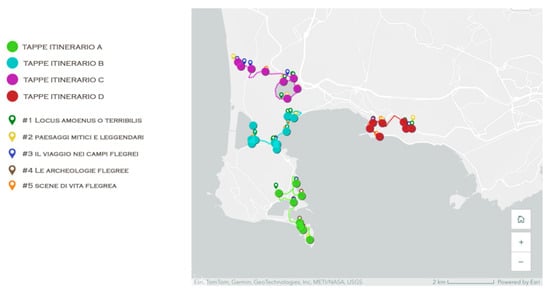

In line with the gaps and expectations highlighted in the previous sections, the choice therefore fell on a dynamic and interactive communication system, namely Esri’s ArcGIS StoryMaps, populated with pictorial images produced between the 18th and 19th centuries that formed the shared imagery of the Phlegraean Fields and now constitute an important testimony to a state that has completely changed as a result of the wild and chaotic construction that the area has undergone since the 20th century (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

A screenshot from the dedicated StoryMaps webpage where it is possible to see a three-dimensional view of the Phlegraean Fields, namely the perspective view of the landscape model compared to the painting “Panorama con il Lago d’Averno/Landscape with Averno’s Lake by W. Richard, 1760 about. The digital storytelling tool provides an immersive experience that integrates the physical experience (elaboration of A. Pagliano).

Operationally, StoryMaps augments on-site exploration through short, geolocated narratives (text/audio), historic–current swipe comparisons, and interactive maps that connect vantage points and the thematically related places identified by the transect-based analysis. This enables on-site, glanceable comparison and reduces cognitive effort for non-expert users. In this way, the phygital layer mitigates the physical fragmentation outlined earlier and re-establishes narrative links between places, artefacts, and landscapes.