Abstract

Reliable forecasts of dam releases are essential to anticipate downstream hydrological responses and to improve the operation of fluvial early warning systems. This study integrates an explicit release prediction module into a digital forecasting framework using the Lindoso–Touvedo hydropower cascade in northern Portugal as a case study. A data-driven approach couples short-term electricity price forecasts, obtained with a gated recurrent unit (GRU) neural network, with dam release forecasts generated by a Random Forest model and an LSTM model. The models (GRU and LSTM) were trained and validated on hourly data from November 2024 to April 2025 using a rolling 80/20 split. The GRU achieved R2 = 0.93 and RMSE = 3.7 EUR/MWh for price prediction, while the resulting performance metrics confirm the high short-term skill of the LSTM model, with MAE = 4.23 m3 s−1, RMSE = 9.96 m3 s−1, and R2 = 0.98. The surrogate Random Forest model reached R2 = 0.91 and RMSE = 47 m3/s for 1 h discharge forecasts. Comparison tests confirmed the statistical advantage of the AI approach over empirical rules. Integrating the release forecasts into the Delft FEWS environment demonstrated the potential for real-time coupling between energy market information and hydrological forecasting. By improving forecast reliability and linking hydrological and energy domains, the framework supports safer communities, more efficient hydropower operation, and balanced river basin management, advancing the environmental, social, and economic pillars of sustainability and contributing to SDGs 7, 11, and 13.

Keywords:

hydropower operations; dam release forecasting; early warning; FEWS; GRU; Random Forest; Lindoso dam 1. Introduction

Climate change and anthropogenic pressures are intensifying hydrometeorological extremes, elevating flood risk, and deteriorating water quality across river networks. Forecasting and early warning systems (FEWS) mitigate these impacts by translating meteorological predictions into forecasts of river flow, inundation, or water quality. Global and regional policy frameworks, most notably the UN Early Warnings for All initiative (targeting universal coverage by 2027) and the European Floods Directive (2007/60/EC), explicitly prioritize FEWS within risk reduction and adaptive basin management strategies [1,2,3]. These initiatives illustrate the growing worldwide emphasis on developing forecasting systems that are not only technically sound but also socially inclusive and regionally adaptable.

Modern FEWS combine ensemble meteorological forcing, coupled hydrologic–hydrodynamic models, and data assimilation to address uncertainties in forcing and model structure. Benchmark reviews emphasize multi-model approaches to span structural errors [4]. Recent comparative studies have confirmed that the use of ensemble and data-assimilation strategies systematically improves short lead (1–7 day) prediction skill and reliability across different basins [5,6,7]. At the same time, the assimilation of discharge and remotely sensed flood extent (e.g., SAR) has been shown to enhance flood forecasting accuracy, particularly in data-scarce catchments. Given the severe consequences of extreme events such as floods, the ability to predict their occurrence, even within short lead times, is essential for timely and effective responses, especially in safeguarding lives [8]. Accordingly, several FEWS initiatives have emerged to anticipate hydrological extremes. Among these, river flood forecasting systems are prominent. Mure Ravaud et al. [9] developed an operational system for the Ouche River (Dijon, France) after a catastrophic flood in 2013. The system integrates hydrological and hydrodynamic models, real-time data assimilation, and web-based dissemination to support decisions across rural and urban zones.

Advanced model coupling and data-assimilation techniques have further improved the forecast accuracy in complex fluvial settings. Barthélémy et al. [10] demonstrated that coupling 1DH/2DH models can better reproduce inundation dynamics and urban flood behavior, while Kauffeldt et al. [4] highlighted that uncertainty remains a persistent issue in operational hydrological forecasting, emphasizing the importance of model diversity. Wijayarathne and Coulibaly [11] concluded that simple hydrological models often perform comparably to complex ones at 1–3 day horizons and recommended ensemble approaches to capture predictive variability more robustly.

Forecasting systems have also been extended beyond flood response, supporting both quantitative and qualitative water management under routine and extreme conditions. For instance, Pinho et al. [12] designed a decision support platform for the Ave River basin in Portugal, integrating real-time data visualization, hydrological and water quality simulations, and scenario analysis. Similar systems were developed for the Alqueva irrigation project, showing the versatility of FEWS-type platforms to support long-term water planning and operation [13,14]. More recently, Pinho et al. [15] assessed the hydrological and infrastructural responses to the January 2016 flood in the Mondego River basin (Portugal), demonstrating that improved coupling between meteorological forecasts, monitoring, and hydrodynamic models substantially enhances early warning performance.

A critical gap persists in many regulated basins: the explicit representation of dam releases (turbine outflows, spills, and pre-releases) within the forecast chain. Because operational releases significantly influence downstream hydrographs, particularly in steep catchments with short concentration times, treating them as exogenous or static can lead to biased estimates of peak magnitude and timing. This evidence suggests that integrating reservoir operations into flood models reduces systematic errors and facilitates scenario analyses. At the same time, large-scale studies demonstrate the detectable hydrological imprint of dam regulation on discharge regimes [16,17,18,19]. However, few studies have explicitly modeled the operational behavior of hydropower plants within real-time forecasting systems, leaving a persistent gap between hydrological prediction and dam-operation decision processes.

Two complementary pathways are emerging in practice: (i) rule or optimization reservoir modules embedded in the forecast chain, and (ii) data-driven surrogates that emulate operational behavior in real time. The Forecast-Informed Reservoir Operations (FIRO) paradigm illustrates the potential of forecast adaptive rules. At Lake Mendocino (California), the Final Viability Assessment and subsequent studies show that FIRO can enhance water supply reliability without compromising flood safety by explicitly conditioning releases based on ensembles of inflow forecasts [20,21,22]. These findings underscore the benefits of integrating forecast-guided operational logic into routine management.

Concurrently, artificial intelligence (AI) has advanced rapidly to predict water flows in regulated basins. Recent studies have demonstrated that Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)/GRU and hybrid models can predict releases and/or downstream flows with higher skill than traditional baselines, capturing nonlinear operational patterns and human decisions. New frameworks also integrate uncertainty quantification and interpretability [23,24,25,26,27]. Despite their high accuracy under flood conditions, most authors conclude that the predictive skill of AI models tends to degrade under normal hydropower operation, when turbine releases depend strongly on energy market signals and plant-specific constraints. For instance, in a FEWS developed for the Douro River estuary, LSTM predictors performed reliably up to a discharge of 5000 m3/s, but showed higher uncertainty during regular turbine-driven operation [28]. These conclusions reveal a clear research gap in coupling market-driven decision processes with hydrological forecasts [28].

Most hydropower forecasting studies target energy production or power output for market participation and scheduling, frequently using day-ahead prices among the predictors but optimizing the generation objective; the mapping from prices to turbined discharge is left implicit. In contrast, studies that explicitly forecast releases/discharges are fewer and typically rely on hydrometeorological drivers (inflow, precipitation, stage), reservoir states, and rule curves; market signals are seldom incorporated directly, and explicit price-informed release surrogates remain rare. Because dam releases are not explicitly modeled, operational river flow forecasts in regulated basins are less accurate, since market-driven commitment decisions modulate turbine on/off states and release magnitudes on sub-daily timescales. Addressing this gap requires new frameworks capable of linking hydrological, operational, and economic drivers within the same forecasting environment.

This study addresses this research gap by introducing a forecasting framework that explicitly links short-term market dynamics to operational reservoir behavior. The novelty lies in coupling electricity price prediction with dam release forecasting inside an operational FEWS, bridging the hydrological and energy domains in real time. The central hypothesis is that short lead electricity price forecasts are relevant to predict turbine discharges with skill comparable to hydrological and operational drivers that usually are more difficult to access or unavailable, thereby improving the accuracy of downstream flow forecasts. Accordingly, two research questions guide this work: (RQ1) To what extent does explicit price-informed release forecasting improve predictive performance compared with conventional rule-based operation? (RQ2) Up to which forecast horizon do such predictions remain reliable and actionable for operational decision support?

By explicitly integrating dam release prediction into forecasting chains, this study contributes to sustainability along the three classical dimensions. Environmentally, it enables more accurate downstream flow and water quality forecasts, improving flood preparedness and ecological protection. Socially, it supports safer and more transparent water and energy governance by providing earlier and more reliable warnings to communities and stakeholders. Economically, it enhances the efficiency of renewable hydropower generation by aligning forecasts with real operational behavior, reducing losses, and improving grid integration. These advances show how technological innovation in forecasting can promote environmentally reliable, socially safer, and economically efficient river basin management, aligning with SDGs 7, 11, and 13.

This study therefore extends previous research by explicitly coupling short-term electricity price forecasts with dam release prediction within an operational forecasting system (Delft-FEWS). Using the Lindoso–Touvedo cascade (Lima River, northern Portugal) as a representative case, it demonstrates the feasibility and benefits of integrating market-driven operational signals into real-time river forecasting. The Lindoso–Touvedo system was chosen for its steep hydrological response, dual regulation function, and strategic role in Portugal’s renewable energy network, providing an appropriate test bed for evaluating release-aware FEWS integration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

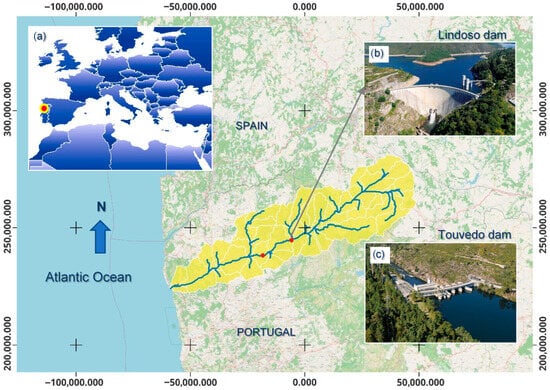

The case study is located in the Lima River basin, northern Portugal, an Atlantic catchment characterized by steep slopes and short hydrologic response times, which make it highly responsive to hydrological extremes. Within this basin, two reservoirs operate in cascade: Alto Lindoso, the largest hydropower facility in Portugal, with a total storage capacity of approximately 379 hm3, operating levels ranging between 280 m and 339 m, a turbine discharge capacity of 240 m3/s, and a spillway capacity of 2500 m3/s; and Touvedo, a smaller reservoir located immediately downstream [29]. The operation of Lindoso exerts decisive control over downstream hydrographs, and the Touvedo dam regulates the turbined discharges of the upstream Lindoso dam. Previous research has highlighted the flood risks in this basin and emphasized the importance of advanced forecasting tools in supporting both safety and hydropower objectives [29]. Figure 1 illustrates the geographical setting of the study area and the locations of the two dams.

Figure 1.

Location and context of the study area. (a) Geographical location (red dot) of the Lima River basin in northern Portugal, shown within a schematic map of Europe. (b) Lindoso dam (publicly available image). (c) Touvedo dam (publicly available image).

2.2. Data

The dataset combined hydrological, operational, and energy market information. Historical outflows at Lindoso were obtained from gauging stations at the dam, managed by the Portuguese Environmental Agency (https://snirh.apambiente.pt (accessed on 1 January 2025)). For this study, the primary dataset covered the period from January 2023 to April 2025, comprising nearly 19,500 hourly records. The variables included the reservoir spillway release (Q Spillway), turbined discharge (Q Turbine), and the Portuguese day-ahead electricity market price. The records were highly consistent, with only 0.02% missing values in the electricity price series.

Hourly Portuguese day-ahead market prices (MIBEL) were retrieved through the REN API (https://datahub.ren.pt/pt/instrucoes-api/ (accessed on 30 April 2025)), covering the study period, which provided a set of 24-hourly values per requested calendar date in units of EUR/MWh. For each day between 1 January 2023 and 27 April 2025, a script was used to download the corresponding daily series, construct hourly timestamps, and concatenate the results into a continuous hourly time series.

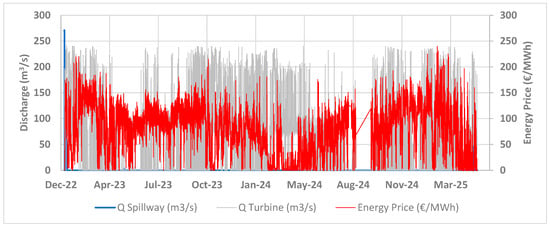

Figure 2 presents the training and test dataset for the period January 2023 April 2025, illustrating the simultaneous variability of discharges and market prices.

Figure 2.

Training and testing dataset (January 2023–April 2025), showing hourly discharges at Lindoso: turbined and zero-spilled discharge (no spill events recorded), together with Portuguese day-ahead electricity market prices. The dataset covers the period from 2023 to April 2025, with approximately 19,500 hourly records.

The resulting dataset thus contains a complete sequence of hourly electricity market prices, synchronized with the hydrological and operational records of the Lindoso reservoir. This time series served as both a direct predictor of turbine operation and as an input to the GRU neural network used to generate energy price forecasts. The GRU then generated a dataset integrating observed and forecasted electricity prices with hydrological variables.

In the Lindoso–Touvedo cascade, the intervening river reach is short and the contributing catchment is comparatively small; consequently, the hourly downstream hydrograph is primarily governed by operational releases from Lindoso. Under normal operation, flows are dominated by turbined discharges, with spills occurring only during high-inflow episodes. Therefore, treating releases as exogenous or static within the forecasting chain induces timing and magnitude biases in the downstream hydrograph. Thus, this work targeted the explicit prediction of turbined discharges under normal operation, using inflow at Touvedo solely for the external validation of the downstream response. Empirically, during the study period, the inflow at Touvedo closely tracked the turbined discharges at Lindoso, with negligible lag, corroborating this assumption (data not presented in this study).

Throughout the 2023–2025 period, reservoir levels at Lindoso remained below the spillway crest and no spill events occurred. The modeling domain therefore corresponds exclusively to normal turbine-driven operation. Spill forecasting was intentionally excluded from this study, as such events require hydrological predictors rather than market-driven ones, consistent with previous FEWS work [28] in the Douro estuary where LSTM models performed reliably for extreme flows but showed greater uncertainty during market-conditioned turbine operation.

Exploratory correlation analysis revealed weak linear relationships between electricity prices and turbine releases, highlighting the need for nonlinear, data-driven models, such as Random Forests, to capture the actual operational patterns. The Pearson correlation coefficient between hourly day-ahead prices and observed turbined discharge was r = −0.046, indicating a negligible linear association and confirming that turbine operation exhibits predominantly nonlinear, discrete behavior.

The combined dataset was further processed to generate a lagged learning base. This included the present and forecasted prices, temporal encodings, and the last 24 h of observed values. The construction of lag features allowed the model to capture the autoregressive dynamics and operational inertia.

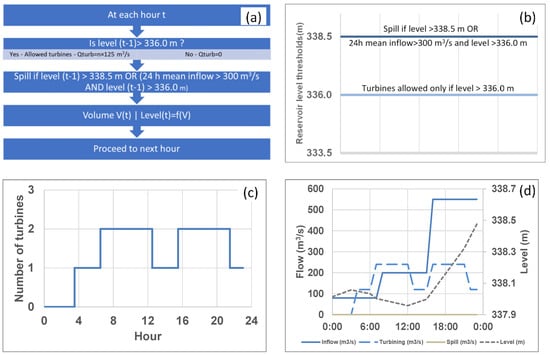

2.3. Rule-Based Method

A conventional rule-based operating model was implemented to provide a benchmark for comparison with the AI approach. In this model, turbine operation was permitted only when the reservoir level exceeded 336 m, with up to two turbines operating simultaneously, each at a capacity of 120 m3/s. Spillway releases were triggered when the reservoir level rose above 338.5 m or when the 24 h mean inflow exceeded 300 m3/s, provided that the level was greater than 336 m. A fixed daily priority schedule was applied to the turbine operation, and the reservoir storage was updated hourly using a mass balance equation. This approach ensures robust and safe operation, but cannot adapt to rapidly changing hydrometeorological or market conditions. The schematic representation of the rule-based operation assumed in this study is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Rule-based operating model: (a) hourly decision flowchart, (b) reservoir level thresholds, (c) daily turbine priority schedule, and (d) example day with inflow, turbine release, spill, and level.

2.4. AI-Based Models

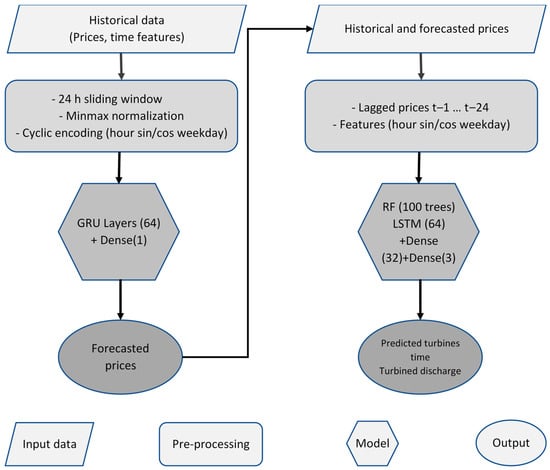

The AI-based forecasting framework developed in this study follows a two-stage approach (Figure 4). In the first stage, electricity market prices are forecasted, as they serve as a proxy for the operational decisions at the hydropower plant. In the second stage, turbine operating states are predicted, since hydropower operation at Lindoso is inherently discrete (0, 1, or 2 turbines), and the hourly turbined discharge reported by the operator corresponds to an average of sub-hourly switching events rather than a physically continuous variable. This approach ensures that the AI component respects the actual decision structure of turbine operation, ensuring that both market dynamics and hydrological drivers are represented in the forecasting chain.

Figure 4.

Architecture of the integrated AI-based models: a GRU network for energy price forecasting (1 h horizon), a Random Forest predictor for turbine operation and discharge using temporal and lagged features, and an LSTM predictor for turbined discharges forecasts. The output of the GRU model feeds the Random Forest and LSTM models, enabling the combined forecasting of reservoir operations.

The first model was designed to predict Portuguese day-ahead market prices for the subsequent hour. This task was implemented using a GRU neural network, a recurrent architecture introduced by Cho et al. [30] and widely used for sequential data. GRUs can capture temporal dependencies in time series while being computationally more efficient than Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks [31].

These series were extended into the future using a GRU neural network [32,33], a recurrent architecture designed to efficiently capture temporal dependencies with reduced complexity compared to LSTM networks [34]. The GRU was trained with normalized historical prices and cyclic encodings of hour of the day and day of the week, generating a 1 h forecast.

To identify the most suitable architecture for price forecasting, three recurrent neural network approaches were tested: a classical LSTM model, a GRU model, and a hybrid Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) LSTM model. All models used the last 24 h of electricity prices, complemented with cyclical encodings of hour of the day and day of the week (sine and cosine transformations). The task consisted of producing direct 1 h ahead forecasts of the day-ahead prices.

The comparative assessment showed clear differences in the performance. The LSTM model tended to smooth the signal and exhibited poor skill in capturing extremes (R2 = 0.54). The CNN LSTM captured local patterns and reproduced general trends with acceptable accuracy (R2 = 0.90), although the predictions were noisier. The GRU model provided the best overall performance, with low error values (RMSE = 10.75 EUR/MWh, MAE = 6.99 EUR/MWh) and very high correlation with observed prices (R2 = 0.96).

Conceptually, the GRU offers a simplified yet powerful recurrent architecture, in which the update and reset gates regulate how past information is retained or forgotten. This enables the model to capture both short-term dynamics and longer temporal dependencies, while being computationally more efficient than LSTM networks [35].

The GRU model was trained on hourly energy prices complemented with cyclical encodings of time features (hour of the day and day of the week expressed as sine and cosine functions). Input sequences of the last 24 h of prices were used as lagged predictors, enabling the model to learn short-term dynamics and daily cycles. The network architecture consisted of a single GRU layer followed by a dense output layer that produced forecasts for the next hour. Training was conducted using the Adam optimizer with the mean squared error as the loss function, and early stopping was employed to prevent overfitting. The result was a sequence of predicted prices that reproduced the main temporal patterns of the electricity market. For readers less familiar with machine learning, it is essential to note that recurrent neural networks, such as GRUs, are specifically designed to “remember” information from the past, making them particularly suitable for problems in which recent conditions strongly influence near-future outcomes, such as energy price forecasting.

The data was divided using a chronological 80/20 split, in which the first 80% of the time series forms the training set and the remaining 20% is the testing set. This walk-forward setup preserves temporal causality and reflects real-time operational conditions. No k-fold rotation was applied. The Random Forest surrogate was trained on the full historical dataset, as it is used only for offline hindcast reconstruction and not for out-of-sample forecasting.

Two AI models were considered in Stage 2, each serving a distinct purpose: a Random Forest (RF) model, used as an offline surrogate for the fast simulation of historical events, and an LSTM classifier, used as the operational online forecasting model.

The Random Forest was trained on the full historical record and provided an inexpensive and very fast approximation of turbine behavior, suitable for exploratory analysis, back-testing of scenarios, and the reconstruction of long historical periods. Because RFs do not exploit temporal dependencies and are sensitive to out-of-sample regime changes, their performance deteriorates when applied to unseen periods.

However, when used offline over the complete historical dataset, the RF offers a reliable surrogate to reproduce the general operational patterns of the plant and is computationally attractive for large-scale batch simulations.

The real-time operational forecasting component is implemented using an LSTM neural network, designed to classify the number of turbines expected to operate one hour ahead. The inputs include forecasted electricity prices, 24 h sequences of lagged prices, and cyclical encodings of hour of the day and day of the week. The network architecture consists of a single LSTM layer with 64 units, followed by a dropout layer, a 32-unit dense layer, and a 3-unit softmax output layer corresponding to the three turbine states.

This formulation respects the discrete logic of turbine operation and avoids inconsistencies associated with predicting continuous discharge from hourly averaged telemetry. It also ensures temporal coherence, as the LSTM explicitly learns the short-term dependencies present in the price-driven operational decisions.

Finally, predicted turbine states were mapped to their nominal discharge values (0, 120, and 240 m3/s) solely for comparison with observed hourly turbined discharge. This mapping requires careful interpretation. Hourly turbined discharge corresponds to the average of six 10 min operational intervals, each possibly containing different turbine states. Because this hourly value aggregates these sub-hourly transitions, intermediate discharges (e.g., 100–160 m3/s) may appear even when one turbine was the predominant operational mode.

The LSTM therefore provides the discrete operational forecast used in the real-time chain, while the discharge reconstruction is used only for interpretability and visual comparison.

For reproducibility, the main hyperparameters used in the AI models are summarized here. The GRU price forecasting model employed 64 hidden units, a dropout rate of 0.1, a learning rate of 0.001, and a 24 h input lag window. The LSTM turbine state classifier consisted of a single LSTM layer with 64 units, followed by a dropout layer, a dense layer with 32 neurons, and a final 3-unit softmax output layer corresponding to the discrete turbine states. For the Random Forest surrogate, the configuration included 500 decision trees, a maximum depth of 12 levels, and a minimum of two samples per leaf.

The models were integrated sequentially: the GRU provided 1 h electricity price forecasts, which were subsequently fed into the Random Forest or LSTM models to predict turbine discharges. The model’s performance was evaluated against observed discharges at Lindoso using the Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and coefficient of determination (R2). In Equations (1)–(3), denotes the observed value at hour t, the corresponding forecast, the mean of observations over the evaluation set, and n the number of time steps:

From a broader perspective, the GRU model captured the temporal structure of market prices, whereas the Random Forest/LSTM models translated those forecasts into realistic turbine operation patterns. This two-stage framework highlights the added value of combining different AI techniques, with recurrent neural networks capturing sequential dependencies and ensemble methods capturing nonlinear decision processes. By explicitly modeling dam releases, the proposed approach overcomes the limitations of conventional rule-based methods and provides more reliable forecasts of downstream flows.

3. Results

3.1. AI Models’ Performance

The performance of the AI models developed in this study was evaluated during the validation period. For the GRU and LSTM models, the 80/20 chronological split produced a validation period from November 2024 to April 2025. Since the RF model is used only as an offline surrogate and not for out-of-sample forecasting, its performance metrics refer to the full training dataset.

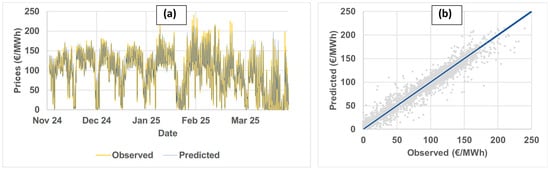

3.1.1. Energy Price Forecasting (GRU)

The GRU network demonstrated excellent skill in reproducing the temporal variability of electricity market prices (Figure 5). The validation metrics yielded an MAE of 6.9 EUR/MWh, an RMSE of 10.7 EUR/MWh, and an R2 = 0.96, indicating that the model can capture both the level and the short-term fluctuations of hourly energy prices with high accuracy. Time series comparisons (for a period between November 2024 to April 2025) show a strong overlap between observed and predicted hourly prices, whilst the scatterplot confirms tight clustering around the 1:1 line. These results highlight the suitability of the model as a driver for subsequent hydropower operation forecasts.

Figure 5.

(a) Observed and predicted hourly energy prices for the period (November 2024–April 2025). (b) Scatterplot of observed versus predicted energy prices (GRU model).

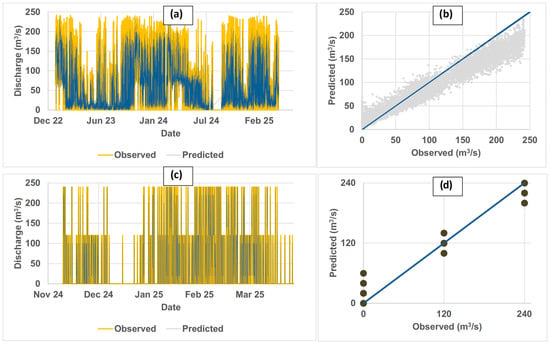

3.1.2. Turbine Discharge Forecasting

The Random Forest model trained on historical discharges, prices, and temporal features achieved an MAE of 15.2 m3/s, an RMSE of 19.9 m3/s, and an R2 = 0.91 during validation. The results presented in Figure 6 demonstrate that the model effectively captures the operational patterns of the Lindoso hydropower plant, including hourly fluctuations linked to market signals. As expected, the largest discrepancies appear during abrupt turbine on/off transitions that are not explicitly represented in the regression scheme. Nevertheless, the overall agreement between observed and predicted values is noteworthy, supporting the use of this surrogate model for short-term hydropower forecasting.

Figure 6.

(a) Observed and predicted turbine discharges (RF model). (b) Scatterplot of observed versus predicted turbine discharges (RF model). (c) Observed and predicted turbine discharges (LSTM model). (d) Scatterplot of observed versus predicted turbine discharges (LSTM model).

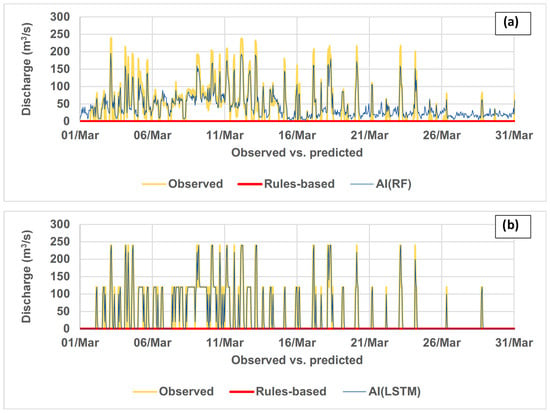

3.2. Rule-Based Versus AI Models Under Normal Turbine Operation

To evaluate the added value of the AI-based approach, the forecasts of turbined discharges were compared with those generated by a conventional rule-based operating model (Section 2.3). The rule-based scheme applied fixed thresholds for the reservoir level and turbine scheduling, with a maximum turbine capacity of 120 m3/s per unit (two units in total). Although this ensures robust operation, it does not account for rapidly varying inflows or market-driven decisions. In contrast, the AI model incorporated electricity price forecasts and historical operation patterns, providing a flexible surrogate for real-time operation.

Figure 7 illustrates the comparison for a representative month (March 2025), where, according to the rule-based approach, the turbined discharge would be 0 m3/s, since the reservoir water level was always below 336 m. The rule-based model produced rigid and often unrealistic outflow patterns. In contrast, the AI-based forecasts closely followed the observed variability of turbine discharges, including the hourly oscillations driven by electricity price signals. The quantitative performance metrics confirm this qualitative difference.

Figure 7.

Observed versus predicted turbined discharges under normal operation for March 2025: (a) comparison between the rule-based model and the AI surrogate (Random Forest); (b) comparison between the rule-based model and the operational AI model (LSTM).

Considering that the entire evaluation period was characterized by normal operation with no spill events, the models were trained and assessed only for turbine discharges. Spill regimes were not part of the training domain and would require a separate hydrology-based modeling approach, as previously demonstrated in studies for the Douro estuary [28].

Across this evaluation period (March 2025), the rule-based model yielded an MAE of 38.3 m3/s, an RMSE of 67.6 m3/s, and a negative coefficient of determination (R2 = −0.47), indicating poor skill and systematic mismatch with observed operation. By contrast, the RF surrogate achieved an MAE of 18.0 m3/s, an RMSE of 21.7 m3/s, and an R2 = 0.85. The operational LSTM model achieved the highest skill, with MAE = 4.0 m3/s, RMSE = 9.4 m3/s, and R2 = 0.98, reproducing the observed discharges with high fidelity. The complete set of performance metrics for this period is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Performance metrics (MAE, RMSE, R2) comparing AI and rule-based forecasts of turbined discharges.

Although simple, the rule-based baseline is more operationally realistic than the default outflow = inflow assumption often used in FEWS configurations. More sophisticated rule curves will be considered in future work as additional operational information becomes available.

4. Discussion

The results demonstrated both the strengths and the limitations of the proposed AI-based forecasting framework. The GRU network for hourly energy price forecasting achieved excellent skill (R2 = 0.96), confirming the working hypothesis that short-term electricity prices can be effectively reproduced with recurrent architectures. This finding is consistent with recent studies reporting high accuracy for GRU/LSTM-based day-ahead price forecasting when temporal dependencies are strong and exogenous covariates are parsimonious [31,35,36]. Accurate price forecasts thus provide a solid basis for downstream hydropower operation models in regulated systems, where market signals influence unit commitment and release magnitudes.

In the second stage, two AI models were evaluated for turbine operation forecasting. The Random Forest model performed well when trained on the full historical dataset, confirming its usefulness as a fast offline surrogate for reconstructing historical operation. However, its performance deteriorated outside the training period, indicating that RF models are not suitable for real-time deployment. This aligns with prior work where release forecasts were derived from hydrometeorological drivers and the reservoir state but not strongly from market-conditioned sub-daily decisions [24,37,38].

In contrast, the LSTM classifier provided operational-grade real-time forecasts, achieving R2 = 0.98 for one-hour-ahead turbine state predictions. This discrete formulation respects the underlying structure of turbine operation (0/1/2 units), avoids the inconsistencies of continuous discharge regression, and accurately captures rapid market-driven changes in release patterns. In terms of operational feasibility, the computational cost is modest: the GRU and LSTM models train within minutes on standard desktop hardware and inference takes only milliseconds, making the approach suitable for real-time deployment within a FEWS environment.

These findings can be better understood when viewed in the context of two parallel bodies of literature, hydrological release forecasting and hydropower production forecasting, each of which addresses part, but not the whole, of the operational problem.

A direct comparison with a rule-based operating scheme underscores this point. While rule curves ensure safe operation during high-inflow episodes, they fail to reproduce the market-driven variability of turbined discharges under normal conditions, yielding large systematic errors (e.g., March 2025: rules predicted zero turbine discharge throughout the month, whereas observations and AI forecasts showed frequent releases). This rigidity in static thresholds and the omission of market signals explains the observed bias, whereas the AI models, particularly the LSTM, successfully reproduced releases across routine operating regimes, including partial and intermittent turbine usage. Comprehensively, this aligns with the evolution toward forecast-conditioned operations (e.g., FIRO), which adapt releases to exogenous forecasts. Our contribution extends that logic to price-informed routine operation, specifically to improve downstream predictions [20].

Multi-step forecasts were initially examined but later removed from the operational framework, as the discrete turbine state signal deteriorates rapidly beyond one hour. As such, only one-hour-ahead forecasts are recommended for real-time operational use in a FEWS-type system, while longer horizons may require probabilistic or sequence-to-sequence architectures to manage uncertainty. The literature suggests direct multi-output (sequence-to-sequence) architectures, hybrid-boosting recurrent ensembles, and probabilistic formulations with uncertainty quantification, directions that can be explored in the future without altering the market-to-release philosophy [39].

Recent release forecasting studies report robust performance when models ingest inflow/level/precipitation data, and, in some cases, infer the effect of management rules [37,38]. By contrast, the hydropower production literature focuses on predicting power/energy for bidding and scheduling, often including prices among predictors but leaving the mapping from price to turbine discharge implicit [40,41]. This study addresses this gap explicitly by translating day-ahead electricity prices into turbine state predictions, thereby providing release-aware inflows to downstream hydrological forecasts in regulated reaches.

The performance obtained in this study is consistent with other recent applications of LSTM, GRU, and tree-based models in reservoir and hydropower forecasting. Studies using hydrometeorological drivers (inflow, precipitation, level) for daily or sub-daily outflow prediction typically report R2 values between 0.70 and 0.95, reflecting the strong physical coupling in these systems. Models attempting to reproduce short-term operational releases, particularly under market-driven regimes and discrete turbine switching, generally obtain lower skill due to the partially unobserved nature of unit commitment. The one-hour skill achieved here (R2 ≈ 0.85–0.90) therefore lies within the upper range of comparable studies and demonstrates that a price-conditioned surrogate can reproduce market-driven operational variability more effectively than hydrology-only predictors.

Transferability to other reservoirs will require incorporating variables that, at Lindoso, were secondary or implicit, including reservoir level/head, environmental flow requirements, ramping constraints, minimum generation levels, maintenance outages, and cascade coordination (such as travel time and multiple units). In basins where decisions are less market-linked (or where spills are frequent), inflow forecasts and reservoir states should be incorporated as structural features. Prior study shows that representing (or inferring) operating rules improves coherence with downstream flow; consequently, hybrid classification regression designs that represent both unit commitment and discharge magnitudes are promising for reducing errors during rapid transitions [38]. Independent studies confirm the substantial downstream imprint of reservoir operations on hydrographs; by removing the “blind spot” of operational releases, river forecasting systems can reduce peak and timing biases and produce more realistic guidance for risk management and scheduling, especially under routine operating conditions [39].

Recent studies framing reservoir and lake forecasting as sustainability enablers typically learn levels or outflows from hydrometeorological drivers and recent history, reporting strong skill at daily to weekly horizons [42,43,44]. However, these approaches do not capture the market conditioned, sub-daily turbine operation decisions typical of hydropower plants. This contrasts with this research, which makes the price release linkage explicit to capture intra-day variability that rule curves and hydro-only surrogates tend to miss. Therefore, our study fills the conceptual gap between hydropower scheduling models that treat releases implicitly and hydrological forecasting studies that neglect market conditioned turbine operation, by providing an explicit and operationally viable mapping from electricity prices to turbine state decisions.

Within the broader flood risk literature, sustainability-oriented work on early warning emphasizes the importance of actionable lead time, community relevance, and operational feasibility from impact-based community FEWS in West Africa to cost–benefit analyses of citizen observatories and flash flood warning feasibility studies [45,46]. By supplying release-aware inflows to the forecast chain, the proposed framework strengthens these public-good functions, improving alerts for navigation, recreational safety, and water-quality advisories in regulated rivers.

Recent analyses increasingly locate hydropower within the water–energy (and water–energy–food) nexus, calling for decision tools that balance environmental integrity, social protection, and economic viability [24,47,48]. Reviews highlight AI’s emerging role as a governance technology, which is particularly useful when embedded in transparent operational workflows that stakeholders can scrutinize. This release-explicit surrogate contributes to this agenda by converting market forecasts into operational guidance, thereby supporting renewable integration, reducing unnecessary spill, and improving downstream risk signaling.

Anchored in these studies, three extensions appear most impactful for sustainability practice: (i) probabilistic, multi-output release forecasts to communicate risk and mitigate error growth beyond one hour; (ii) hybrid classification–regression designs to model unit commitment and ramping explicitly, improving safety-critical warnings around rapid on/off transitions; and (iii) digitalized monitoring (e.g., unit status and bay-level telemetry) that closes the loop between forecasts, operations, and stakeholder transparency directions consistent with recent sustainability-oriented FEWS and climate adaptation assessments [24,42,47,48]. Future work will also incorporate probabilistic forecasting, via RF bootstrapping or Monte Carlo dropout for LSTM, to quantify uncertainty and provide confidence intervals for operational decision-making.

Although the proposed framework was developed for the Lindoso hydropower plant, its transferability to other contexts is promising. Whereas the modeling chain relies mainly on short-term electricity market prices and historical turbine operation data rather than basin-specific hydrological characteristics, the approach is well suited to regulated systems where releases are strongly linked to market signals. When price-driven operation and comparable discharge (or turbine state) telemetry are available, the methodology can be adopted with minimal structural modification. Practical considerations include the local availability of high-frequency operational records, plant-specific constraints such as ramping rules or minimum flow requirements, and differences in market exposure. These factors may require calibration adjustments, but do not alter the underlying workflow, suggesting good scalability to other market-influenced hydropower systems.

Finally, it must be stressed that the Touvedo inflow is mentioned only to contextualize the downstream relevance of Lindoso outflows. A meaningful comparison requires coupling with the hydrological–hydrodynamic modules of the FEWS cascade, which lies outside the scope of this study and will be addressed in future work.

5. Conclusions

This study implemented a two-stage AI framework that linked short-term electricity price forecasts (GRU) to turbined discharge prediction to optimize operational dam release modeling. The GRU model reproduced hourly electricity prices with high accuracy, and the discrete LSTM model provided reliable one-hour-ahead turbine state forecasts (MAE = 4.0 m3/s, RMSE = 9.3 m3/s, R2 = 0.98). These results show that market signals can be translated into accurate, operationally meaningful release forecasts in systems where sub-daily operation is strongly market driven. The improved release prediction accuracy (RMSE reduction of ~60–70 m3/s) relative to the rule-based benchmark directly reduces boundary condition errors for downstream FEWS modules, supporting earlier and more reliable advisories and low-flow warnings.

The Random Forest model was retained as a fast offline surrogate for historical reconstruction, but only the LSTM classifier proved suitable for real-time forecasting. By explicitly modeling turbine states rather than relying on fixed rule curves or implicit operating assumptions, the approach supplies release-aware inflows to downstream hydrological models and corrects a structural omission common in many FEWS-type systems.

This study has several limitations. Turbine operation is only partially observed at hourly resolution, and abrupt start/stop transitions remain challenging to capture. The model also relies on price signals alone and does not yet incorporate reservoir level, ramping constraints, or other operational drivers relevant in less market-controlled systems. Forecast skill degrades beyond the one-hour horizon, and the current formulation is deterministic.

Future work should explore probabilistic forecasting to quantify uncertainty, hybrid classification–regression architectures to better represent ramping and partial-flow transitions, and the integration of improved operational telemetry. Extending the approach to cascaded reservoirs and systems where market influence is weaker will further test its generality. Despite that, the proposed framework already provides a practical and operationally relevant pathway for improving short-term flow prediction and river management support in regulated basins.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P.; Methodology, J.P. and W.W.d.M.; Software/model execution, J.P.; Validation, J.P. and W.W.d.M.; Formal analysis, J.P. and W.W.d.M.; Investigation, J.P. and W.W.d.M.; Writing—original draft preparation, J.P. and W.W.d.M.; Writing—review and editing, J.P. and W.W.d.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Institutional support from CTAC—Centre for Territory, Environment and Construction (FCT reference UID/04047/2025 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/04047/2025) is acknowledged; no dedicated project funding supported this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge CTAC—Centre for Territory, Environment and Construction and FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Willian Weber de Melo was employed by the company Moody’s Analytics. Both authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- UNDRR. Early Warnings for All: Executive Action Plan 2023 2027; United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.undrr.org (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- UN. Early Warnings for All (Initiative Page). United Nations. 2024. Available online: https://earlywarningsforall.org/site/early-warnings-all (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- European Parliament and Council. Directive 2007/60/EC on the Assessment and Management of Flood Risks. Off. J. Eur. Union 2007, L288, 27–34. Available online: https://eurlex.europa.eu (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Kauffeldt, A.; Wetterhall, F.; Pappenberger, F.; Salamon, P.; Thielen, J. Technical review of large scale hydrological models for implementation in operational flood forecasting schemes on continental level. Environ. Model. Softw. 2016, 75, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Gharamti, M.; McCreight, J.L.; Noh, S.J.; Hoar, T.J.; RafieeiNasab, A.; Johnson, B.K. Ensemble streamflow data assimilation using WRF Hydro and the National Water Model for Hurricane Florence. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 5315–5346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostache, R.; Chini, M.; Giustarini, L.; Neal, J.; Kavetski, D.; Wood, M.; Corato, G.; Pelich, R.; Matgen, P. Near real time assimilation of SAR derived flood maps for improving flood forecasts. Water Resour. Res. 2018, 54, 5516–5535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mauro, C.; Hostache, R.; Matgen, P.; Pelich, R.; Chini, M.; van Leeuwen, P.J.; Nichols, N.K.; Blöschl, G. Assimilation of probabilistic flood maps from SAR data into a coupled hydrologic hydraulic forecasting model: A proof of concept. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 4081–4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, D.H.; Lee, M.H.; Moon, S.K. Development of a precipitation area curve for warning criteria of short duration flash flood. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 18, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mure Ravaud, M.; Binet, G.; Bracq, M.; Perarnaud, J.; Fradin, A.; Litrico, X. A web based tool for operational real time flood forecasting using data assimilation to update hydraulic states. Environ. Model. Softw. 2016, 84, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthélémy, S.; Ricci, S.; Morel, T.; Goutal, N.; Le Pape, E.; Zaoui, F. On operational flood forecasting system involving 1D/2D coupled hydraulic model and data assimilation. J. Hydrol. 2018, 562, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijayarathne, D.B.; Coulibaly, P. Identification of hydrological models for operational flood forecasting in St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2020, 27, 100646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, J.; Vieira, J.; Pinho, R.; Araujo, J. Web Based Decision Support Framework for Water Resources Management at River Basin Scale. Curr. Issues Water Manag. 2011, 44–65. [Google Scholar]

- Pinho, J.; Vieira, J.; Pinho, R.; Araújo, J. A web based decision support system for water quality management in a large multipurpose reservoir. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Hydroinformatics, Hamburg, Germany, 14–18 July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, A.; Samevedham, L.; Schwanenberg, D.; Galelli, S.; Vieira, J.; Pinho, J. A coordination based approach for real-time management of large-scale water systems. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Hydroinformatics, Hamburg, Germany, 14–18 July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pinho, J.L.S.; Vieira, L.; Vieira, J.M.P.; Venâncio, S.; Simões, N.; Sá Marques, A.; Seabra Santos, F. Assessing causes and associated water levels for an urban flood using hydroinformatic tools. J. Hydroinform. 2020, 22, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.; Juan, A.; Bedient, P. Integrating Reservoir Operations and Flood Modeling with HEC RAS 2D. Water 2020, 12, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salwey, S.; Coxon, G.; Pianosi, F.; Singer, M.B.; Hutton, C. National scale detection of reservoir impacts through hydrological signatures. Water Resour. Res. 2023, 59, e2022WR033893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinti, R.A.; Condon, L.E.; Zhang, J. The evolution of dam induced river fragmentation in the United States. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin, F.; Razavi, S.; Elshamy, M.; Davison, B.; Sapriza Azuri, G.; Wheater, H. Representation and improved parameterization of reservoir operation in hydrological and land surface models. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 23, 3735–3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CW3E (Scripps/UCSD). Lake Mendocino FIRO: Final Viability Assessment. 2020. Available online: https://cw3e.ucsd.edu/firo (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Delaney, C.J.; Hartman, R.K.; Mendoza, J.; Dettinger, M.; Delle Monache, L.; Jasperse, J.; Ralph, F.M.; Talbot, C.; Brown, J.; Reynolds, D.; et al. Forecast Informed Reservoir Operations Using Ensemble Streamflow Predictions for a Multi Purpose Reservoir in Northern California. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2019WR026604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodeur, Z.P.; Delaney, C.; Whitin, B.; Steinschneider, S. Synthetic forecast ensembles for evaluating forecast informed reservoir operations. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR034898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longyang, Q.; Zeng, R. A Hierarchical Temporal Scale Framework for Data Driven Reservoir Release Modeling. Water Resour. Res. 2023, 59, e2022WR033922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Zhang, L.; Liu, S.; Yang, T.; Lu, D. Investigation of hydrometeorological influences on reservoir release using LSTM and SHAP. Front. Water 2023, 5, 1112970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.; Guan, W.; Cao, J.; Zou, Y.; Yang, M.; Wei, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, H. A hybrid hydrologic modelling framework with data driven and conceptual reservoir operation schemes for reservoir impact assessment and predictions. J. Hydrol. 2023, 619, 129246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.N.; Ivanov, V.Y.; Nguyen, G.T.; Anh, T.N.; Nguyen, P.H.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, J. A deep learning modeling framework with uncertainty quantification for inflow outflow predictions for cascade reservoirs. J. Hydrol. 2024, 629, 130608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Fuente, L.A.; Ehsani, M.R.; Gupta, H.V.; Condon, L.E. Toward interpretable LSTM based modeling of hydrological systems. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 28, 945–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo, W.W.; Iglesias, I.; Pinho, J. Early warning system for floods at estuarine areas: Combining artificial intelligence with process based models. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 4615–4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, L.; Pinho, J.; Schwanenberg, D. Towards a Decision Support System for Flood Management in a River Basin. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Hydroinformatics (HIC 2014): Informatics and the Environment Data and Model Integration in a Heterogeneous Hydro World, New York, NY, USA, 17–21 August 2014; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 2924–2931. Available online: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_conf_hic/358/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Cho, K.; van Merriënboer, B.; Gulcehre, C.; Bahdanau, D.; Bougares, F.; Schwenk, H.; Bengio, Y. Learning Phrase Representations using RNN Encoder Decoder for Statistical Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Doha, Qatar, 25–29 October 2014; Moschitti, A., Pang, B., Daelemans, W., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2014; pp. 1724–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Gulcehre, C.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Empirical Evaluation of Gated Recurrent Neural Networks on Sequence Modeling. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Liu, L.; Liu, J.; Gu, Y. ATTnet: An Explainable Gated Recurrent Unit Neural Network with Attention for Electricity Spot Price Forecasting. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 158, 109975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitsos, V.; Vontzos, G.; Bargiotas, D.; Daskalopulu, A.; Tsoukalas, L.H. Data Driven Techniques for Short Term Electricity Price Forecasting through Novel Deep Learning Approaches with Attention Mechanisms. Energies 2024, 17, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Van Merriënboer, B.; Bahdanau, D.; Bengio, Y. On the properties of neural machine translation: Encoder decoder approaches. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.; Ramentol, E.; Schirra, F.; Michaeli, H. Short and long-term forecasting of electricity prices using embedding of calendar information in neural networks. J. Commod. Mark. 2022, 28, 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria Lopez, A.; Sobrido Pouso, C.; Mejuto, J.C.; Astray, G. Assessment of Different Machine Learning Methods for Reservoir Outflow Forecasting. Water 2023, 15, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tounsi, A.; Temimi, M.; Gourley, J.J. On the use of machine learning to account for reservoir management rules and predict streamflow. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 18917–18931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.; Zohren, S. Time series forecasting with deep learning: A survey. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2021, 379, 20200209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejewski, D.; Mudryk, K.; Sporysz, M. Forecasting Electricity Production in a Small Hydropower Plant (SHP) Using Artificial Intelligence (AI). Energies 2024, 17, 6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, C.; Feng, Y.; Wang, S. Predicting hydropower generation: A comparative analysis of machine learning models and optimization algorithms for enhanced forecasting accuracy and operational efficiency. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2025, 16, 103299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, H.H.; Chang, S.W.; Lee, J.E.; Chung, I.M. Evaluating the Hydrological Impact of Reservoir Operation on Downstream Flow of Seomjin River Basin: SWAT Model Approach. Water 2024, 16, 3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.W.; Huang, Y.F.; Koo, C.H.; Teo, K.T.K.; Ahmed, A.N.; Razali, S.F.M.; Elshafie, A. A Review of Hybrid Deep Learning Applications for Streamflow Forecasting. J. Hydrol. 2023, 625, 130141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Huo, Z.; Miao, P.; Tian, X. Comparison of Machine Learning Models to Predict Lake Area in an Arid Area. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, S.; Ozkan Yildirim, S. Prediction of Water Level in Lakes by RNN Based Deep Learning Algorithms to Preserve Sustainability in Changing Climate and Relationship to Microcystin. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, M.; Wehn, U.; See, L.; Monego, M.; Fritz, S. The Value of Citizen Science for Flood Risk Reduction: Cost–Benefit Analysis of a Citizen Observatory in the Brenta–Bacchiglione Catchment. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 24, 5781–5798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarchiani, V.; Massazza, G.; Rosso, M.; Tiepolo, M.; Pezzoli, A.; Housseini Ibrahim, M.; Katiellou, G.L.; Tamagnone, P.; De Filippis, T.; Rocchi, L.; et al. Community and Impact Based Early Warning System for Flood Risk Preparedness: The Experience of the Sirba River in Niger. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amore, G.; Di Vaio, A.; Balsalobre Lorente, D.; Boccia, F. Artificial Intelligence in the Water–Energy–Food Model: A Holistic Approach towards Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2022, 14, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).