A Taxonomy of Responsible Consumption Initiatives and Their Social Equity Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Responsible Consumption and Equity in Organizational Contexts

2.2. Responsible Consumption and Equity from Social Justice Perspectives

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Eligibility Criteria

3.2. Sources of Information

3.3. Search Strategy

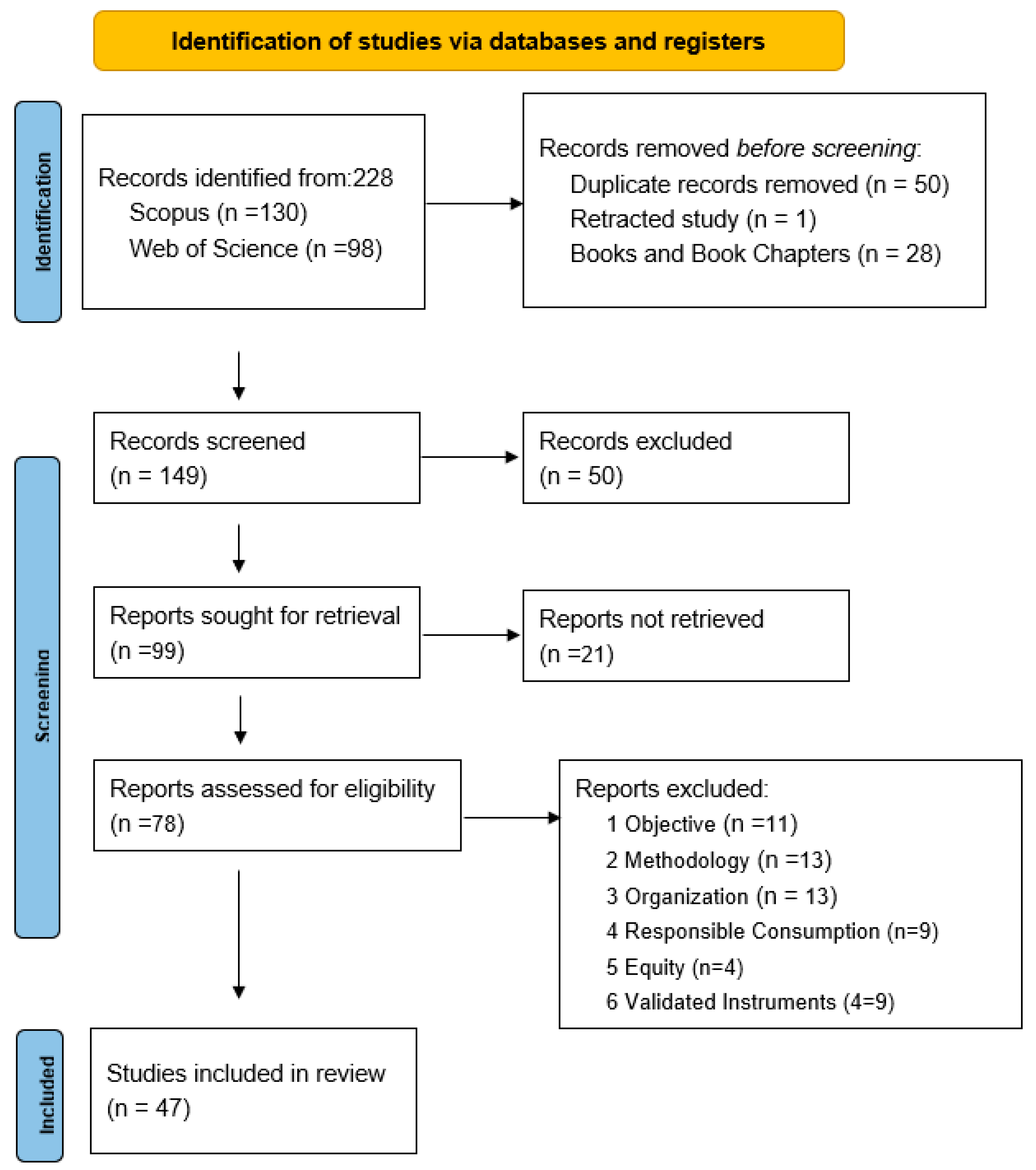

3.4. Selection Process

3.5. Data Collection Process

3.6. Data Elements

3.7. Synthesis Methods

4. Results

4.1. Selection of Studies

4.2. Characteristics of the Study

| Authors | Year | Qualification | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Furlong, K. [38] | 2013 | The Dialectics of Equity: Consumer Citizenship and the Extension of Water Supply in Medellin, Colombia | Colombia (Medellín) |

| Lyon, S. [39] | 2014 | Fair trade towns USA: Growing the market within a diverse economy | USA |

| Balsiger, P. [40] | 2014 | Between shaming corporations and promoting alternatives: The politics of an “ethical shopping map” | Swiss |

| Milovantseva, N.; Fitzpatrick, C. [41] | 2015 | Barriers to electronics reuse of transboundary e-waste shipment regulations: An evaluation based on industry experiences | Multinational, with emphasis on countries in the European Union, the United States, Costa Rica, Venezuela, Ukraine, India, Jordan, South Africa, among others. |

| Kingston, L.N.; Guellil, J. [42] | 2016 | TOMS and the Citizen-Consumer: Assessing the Impacts of Socially Minded Consumption | USA |

| Gough, I. [43] | 2017 | Recomposing consumption: Defining necessities for sustainable and equitable well-being | United Kingdom |

| Ladhari, R; Tchetgna, N.M. [44] | 2017 | Values, socially conscious behavior and consumption emotions as predictors of Canadians’ intent to buy fair trade products | Canada |

| Argüelles, L.; Anguelovski, I.; Dinnie, E. [45] | 2017 | Power and privilege in alternative civic practices: Examining imaginaries of change and embedded rationalities in community economies | Multiple countries in Europe: Finland, Germany, Italy, Scotland and Spain |

| De Hoop, E.; Jehlička, P. [46] | 2017 | Reluctant pioneers in the European periphery? Environmental activism, food consumption and “growing your own” | Czech Republic (post-socialist context of Eastern Europe) |

| Cardozo, L.R. [47] | 2017 | Development of Mexican Non-Governmental Organizations and its Coincidences with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals | Mexico |

| Tolosa, A.E.; Irizar, M.Z.; Elena, M.T. [48] | 2017 | An approach to consequences of market orientation in the Basque social Economy fostering public service | Spain (Autonomous Community of the Basque Country) |

| Rommel, J.; Radtke, J.; von Jorck, G.; Mey, F.; Yildiz, Ö. [62] | 2018 | Community renewable energy at a crossroads: A think piece on degrowth, technology, and the democratization of the German energy system | Germany |

| Hankammer, S.; Kleer, R. [49] | 2018 | Degrowth and collaborative value creation: Reflections on concepts and technologies | Germany (RWTH Aachen University and Technical University of Berlin) |

| Lobato-Calleros, M.O.; Fabila, K.; Shaw, P.; Roberts, B. [50] | 2018 | Quality assessment methods for index of community sustainability | Canada (Cowichan Valley, British Columbia) |

| Cuomo, M.T.; Foroudi, P.; Tortora, D.; Hussain, S.; Melewar, T.C. [51] | 2019 | Celebrity Endorsement and the Attitude Towards Luxury Brands for Sustainable Consumption | United Kingdom (data collected in London) |

| Garcia-De los Salmones, M.D.M.; Laziness. [54] | 2019 | The role of brand utilities: application to buying intention of fair trade products | Spain (University of Cantabria; study at a fair trade university in Spain) |

| Jones, R.; Wham, C.; Burlingame, B. [52] | 2019 | New Zealand’s food system is unsustainable: A survey of the divergent attitudes of agriculture, environment, and health sector professionals towards eating guidelines | United Kingdom (both authors are affiliated with UK universities: University of Manchester and University of Bristol) |

| Welch, D.; Southerton, D. [53] | 2019 | After Paris: transitions for sustainable consumption | United Kingdom (both authors affiliated with British universities) |

| Dinu, M.; Patarlageanu, S.R.; Petrariu, R.; Constantin, M.; Potcovaru, A.M. [55] | 2020 | Empowering Sustainable Consumer Behavior in the EU by Consolidating the Roles of Waste Recycling and Energy Productivity | Romania (Bucharest University of Economic Studies; applied study of the European Union) |

| Caruana, R.; Glozer, S.; Eckhardt, G.M. [56] | 2020 | ‘Alternative Hedonism’: Exploring the Role of Pleasure in Moral Markets | United Kingdom (authors affiliated with British universities and interviews conducted in the UK) |

| Guerra, P.; Lavega, S.R. [57] | 2020 | Social and solidarity economy law in Uruguay: Text and context | Uruguay |

| Lynch, A.J.; Elliott, V.; Phang, S.C.; Claussen, J.E.; Harrison, I.; Murchie, K.J.; Steel, E.A.; Stokes, G.L. [58] | 2020 | Inland fish and fisheries integral to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals | United States (organizations and authors linked to the USGS, Smithsonian, American universities) |

| Villalba-Eguiluz, U.; Egia-Olaizola, A.; from Mendiguren, J.C.P. [59] | 2020 | Convergences between the Social and Solidarity Economy and Sustainable Development Goals: Case Study in the Basque Country | Spain (Basque Country) |

| Zhou, M.; Govindan, K.; Xie, X.B. [60] | 2020 | How fairness perceptions, embeddedness, and knowledge sharing drive green innovation in sustainable supply chains: An equity theory and network perspective to achieve sustainable development goals | China (empirical study applied to 225 manufacturing companies in 16 provinces) |

| Garwood, K.C.; Steingard, D.; Balduccini, M. [61] | 2020 | Dynamic collaborative visualization of the united nations sustainable development goals (SDGs): Creating an SDG dashboard for reporting and best practice sharing | United States (Saint Joseph’s University, Philadelphia) |

| Hess, O.; Relan, A.; Shaghaghi, N. [63] | 2020 | GoodBuys | United States (Santa Clara University, California) |

| Mathai, M.V.; Isenhour, C.; Stevis, D.; Vergragt, P.; Bengtsson, M.; Lorek, S.; Mortensen, L.F.; Coscieme, L.; Scott, D.; Waheed, A.; Alfredsson, E. [64] | 2021 | The Political Economy of (Un)Sustainable Production and Consumption: A Multidisciplinary Synthesis for Research and Action | An international and comparative approach with contributions from authors from India, the United States, Europe, Japan, and Pakistan. |

| Olwig, M.F. [65] | 2021 | Sustainability superheroes? For-profit narratives of “doing good” in the era of the SDGs | Denmark (although with implications for European and global multinationals) |

| Hatipoglu, B.; Inelmen, K. [66] | 2021 | Effective management and governance of Slow Food’s Earth Markets as a driver of sustainable consumption and production | Multinational exhibition (52 markets in 14 countries); largest representation in Italy |

| Morell, M.F.; Espelt, R.; Cano, M.R. [67] | 2021 | Expanded abstract Platform cooperativism: Analysis of the democratic qualities of cooperativism as an economic alternative in digital environments | Spain (although it includes platforms from several European countries) |

| Stojanova, S.; Cvar, N.; Verhovnik, J.; Bozic, N.; Trilar, J.; Kos, A.; Duh, E.S. [68] | 2022 | Rural Digital Innovation Hubs as a Paradigm for Sustainable Business Models in Europe’s Rural Areas | Slovenia (case study: Divina Wine Hub in Šmarje) |

| Narayanan, S. [69] | 2022 | Does Generation Z value and reward corporate social responsibility practices? | India |

| Khaskhely, M.K.; Qazi, S.W.; Khan, N.R.; Hashmi, T; Chang, A.A.R. [70] | 2022 | Understanding the Impact of Green Human Resource Management Practices and Dynamic Sustainable Capabilities on Corporate Sustainable Performance: Evidence From the Manufacturing Sector | Pakistan |

| Zhang, X.M.; Cao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, J.S. [71] | 2022 | Fairness Concern in Remanufacturing Supply Chain-A Comparative Analysis of Channel Members’ Fairness Preferences | China (Zhejiang University of Technology) and USA (University of Iowa, co-author) |

| Sänger, J. [72] | 2023 | Stepping up on climate action—How can book sector associations support businesses in reducing CO2 emissions? | Germany (Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels) |

| Cleveland, D.A. [73] | 2023 | What’s to Eat and Drink on Campus? Public and Planetary Health, Public Higher Education, and the Public Good | United States (University of California, Santa Barbara) |

| Hoekstra, J.C.; Leeflang, P.S.H. [74] | 2023 | Thriving through turbulence Lessons from marketing academia and marketing practice | Netherlands (University of Groningen) and United Kingdom (Aston Business School) |

| Bisquert I Pérez, K.M.; Meira Cartea, P.Á.; Agúndez Rodríguez, A. [76] | 2023 | Ecocitizenship and Food Consumption Education. Socio-Educational Good Practices in Citizen Initiatives of Responsible Consumption | Spain (province of A Coruña, Galicia) |

| Huerta, M.K.; Garizurieta, J.; González, R.; Infante, L.-Á.; Horna, M.; Rivera, R.; Clotet, R. [77] | 2023 | A Long-Distance Wi-Fi Network as a Tool to Promote Social Inclusion in Southern Veracruz, Mexico | Mexico (Mecayapan, Veracruz) |

| Gupta, S.; Bothra, N. [78] | 2023 | Is CSR still optional for Luxury Brands, or can they afford to ignore it? | India (both authors are from universities in Delhi) |

| Leonidou, L.C.; Theodosiou, M.; Nilssen, F.; Eteokleous, P.; Voskou, A. [75] | 2024 | Evaluating MNEs’ role in implementing the UN Sustainable Development Goals: The importance of innovative partnerships | Multinational study (authors based in Cyprus and Norway); the analysis includes multinational companies from North America, Europe, and Asia. |

| Stein, L.; Michalke, A.; Gaugler, T.; Stoll-Kleemann, S. [79] | 2024 | Sustainability Science Communication: Case Study of a True Cost Campaign in Germany | Germany |

| Velásquez Chacón, E.; Salinas Gainza, F.R. [80] | 2024 | Difficulties for the integration of the circular economy in the strategic sustainable management of SMEs in Arequipa, Peru | Peru (Arequipa region) |

| Appiah, M.K.; Dordaah, J.N. Sam, A.; Amaning, N. [81] | 2024 | Modeling the implications of sustainable supply chain management practices on firm performance: the mediating role of green performance | Ghana |

| Saha, P.; Belal, H.M.; Talapatra, S. [82] | 2024 | Driving Toward Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the Ready-Made Garments (RMGs) Sector: The Role of Digital Capabilities and Operational Transparency | Bangladesh |

| Xu, Z.Y.; Song, Z.W.; Fong, K.Y. [83] | 2025 | Perceived Price Fairness as a Mediator in Customer Green Consumption: Insights from the New Energy Vehicle Industry and Sustainable Practices | China |

| Adeborode, K.O.; Dora, M.; Umeh, C.; Hina, S.M.; Eldabi, T. [84] | 2025 | Leveraging organizational agility in B2B ecosystems to mitigate food waste and loss: A stakeholder perspective | Nigeria |

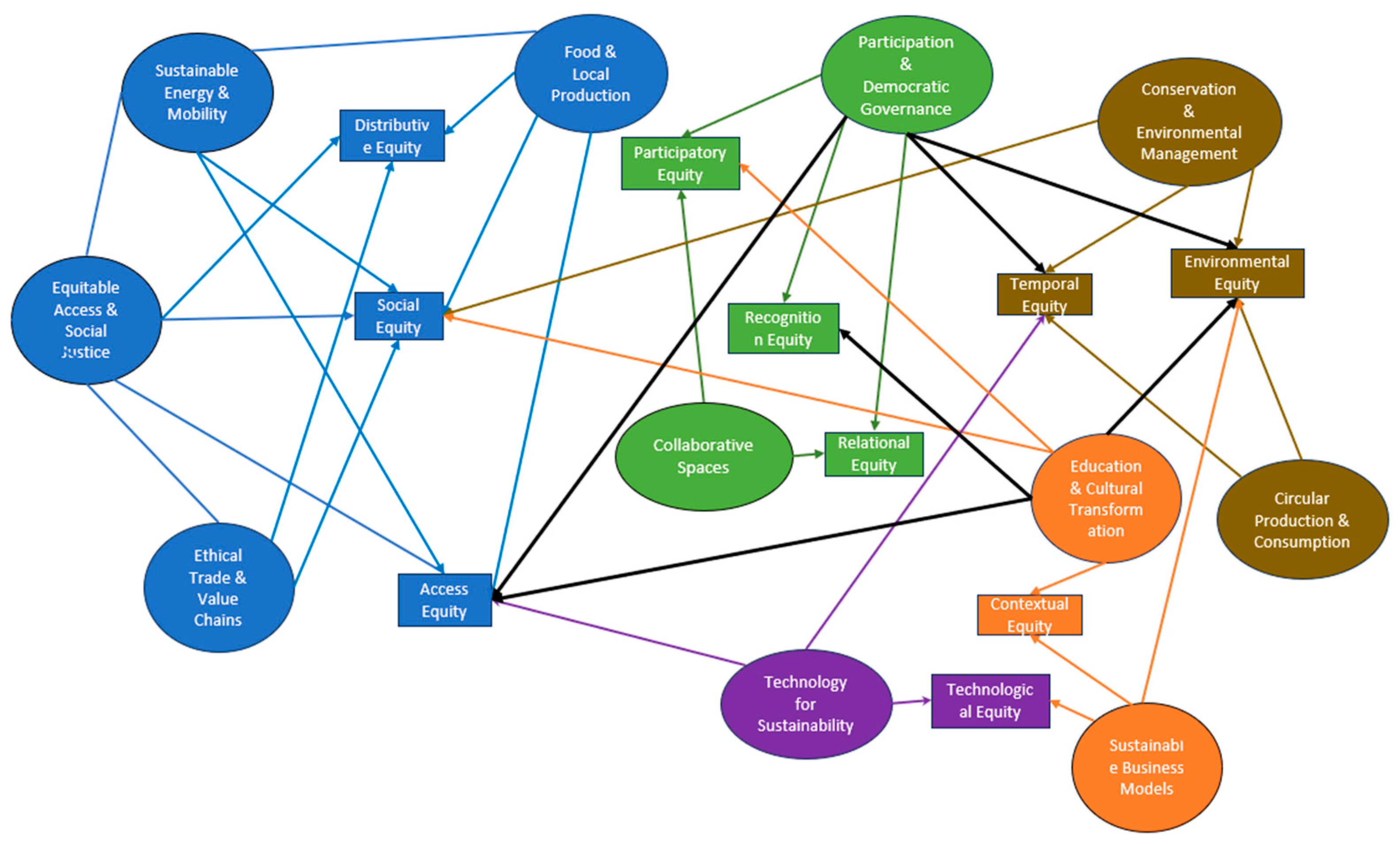

4.3. Results of the Synthesis

4.3.1. Responsible Consumption Initiatives Implemented by Organizations in Different Contexts

4.3.2. Forms of Social Equity Addressed in the Reviewed Studies

| General Category | Specific Forms of Equity | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Equal access | Equity of access and inclusion; Equity of access; Information and digital equity; Equity in education and access to knowledge | [38,39,40,41,42,43,45,46,47,48,50,51,52,53,54,57,61,63,68,75,77] |

| Distributive equity | Distributive equity; Economic equity; Perceived price equity | [38,39,43,44,49,50,52,53,55,57,58,60,62,65,66,67,77,78,80,83] |

| Equity of recognition | Equity of recognition; Symbolic equity; Cultural and recognition equity | [38,39,40,42,43,44,45,46,49,51,52,53,54,56,57,62,63,64] |

| Participatory equity | Participatory equity; Procedural equity; Digital and governance equity | [38,39,40,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,52,53,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,66,67,76,77] |

| Contextual equity | Contextual equity; Territorial equity; Global equity | [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,49,50,53,56,59,61,62,66,68,76,80] |

| Environmental equity | Environmental equity; Ecological equity; Sustainability and natural resource equity | [40,41,45,46,47,55,57,58,59,61,63,64,66,67,75,79,81] |

| Social equity | Social equity; Gender equity; Racial and social equity; Labor equity; Equity in working conditions; Food equity | [57,58,59,61,63,64,66,67,73,75,76,79,82,87] |

| Temporary equity | Intergenerational equity | [43,52,53,55,56,58,64] |

| Technological equity | Technological equity | [49] |

| Relational equity | Relational equity | [60] |

4.3.3. Equity Promotion Mechanisms and Outcomes

5. Discussion

5.1. Forms of Social Equity and Initiative Impacts

5.2. Causal Mechanisms: How Initiatives Generate Equity

5.3. Limitations and Future Studies

5.4. Implications

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Borg, K.; Macklin, J.; Kaufman, S.; Curtis, J. Consuming responsibly: Prioritising responsible consumption behaviours in Australia. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2024, 12, 100181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, V.; Dahiya, A.; Tyagi, V.; Sharma, P. Development and validation of scale to measure responsible consumption. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2023, 15, 795–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabłońska-Karczmarczyk, K. Towards Socially Responsible Consumption: Assessing the Role of Prayer in Consumption. Religions 2024, 15, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, C.G.; Caffray, K.; Maas, K. Implementing Equity: Planners, Officials, and Equity Policy. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2025, 91, 380–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyamsundar, P.; Marques, P.; Smith, E.; Erbaugh, J.; Ero, M.; Hinchley, D.; James, R.; Leisher, C.; Nakandakari, A.; Pezoa, L.; et al. Nature and equity. Conserv. Lett. 2023, 16, e12956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, M.O.R.; Heldt, R.; Silveira, C.S.; Luce, F.B. Brand equity chain and brand equity measurement approaches. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2023, 41, 442–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, A.; Ramachandaran, S. Online Apparel Purchase and Responsible Consumption Among Malaysians. TEM J. 2023, 12, 2378–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranowski, M.; Kopnina, H. Socially responsible consumption: Between social welfare and degrowth. Econ. Sociol. 2022, 15, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpova, S.; Cherenkov, V.; Rozhkov, I. Responsible consumption in the evolution of marketing. OOO “Zhurnal “Voprosy Istorii. 2022, 2022, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcombe, A.-C.; Sayfullaev, K.; Islamova, N. Redefining responsible consumption decent work: Insights from the second-hand industry in Uzbekistan. J. East. Eur. Cent. Asian Res. (JEECAR) 2024, 11, 604–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, N.; Solanki, C.S.; Kumar, A. Responsible energy production and consumption: Improving knowledge, attitude and behaviour through energy literacy training in India. Clim. Policy 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S. Environmental mitigation through responsible consumption: A Markov process model on parental influence. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S. Culture and individual attitudes towards responsible consumption. J. Islam. Mark. 2025, 16, 2077–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcão, D.; Roseira, C. Mapping the socially responsible consumption gap research: Review and future research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 1718–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, B. Debt or equity? Financial impacts of R&D support across firm demographics. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2024, 31, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Echeverri, H.; Rosso, J.; Fragua, D.F. Effects of Foreign Investment on Domestic Private Equity. Int. J. Econ. Bus. 2021, 28, 247–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Echeverri, H.; Nandy, D.K.; Fragua, D. The role of private equity investments on exports: Evidence from OECD countries. J. Multinatl. Financ. Manag. 2022, 65, 100739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Pan, H. Can cross-listing relax financial frictions in trade and equity holdings? A sector-level analysis. Appl. Econ. 2015, 47, 2012–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, L. Globalisation with Growth and Equity: Can we really have it all? Third World Q. 2011, 32, 629–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeerken, A.; Feng, D. Does digital service trade promote inclusive domestic growth?—Empirical research of 46 countries. Econ. Labour Relat. Rev. 2024, 35, 292–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, S.; Li, L.; Cui, W. How Does Foreign Equity Right Impact Manufacturing Enterprise Innovation Behaviors? Mediation Test Based on Technology Introduction. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2020, 2020, 8921083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Lee, J.-D.; Hwang, W.-S.; Yeo, Y. Growth versus equity: A CGE analysis for effects of factor-biased technical progress on economic growth and employment. Econ. Model. 2017, 60, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawls, J. A Theory of Justice; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M.C. Creating Capabilities; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargittai, E.; Hsieh, Y.P. Digital Inequality; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. Reimagining Political Space in a Globalizing World; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/fras14680 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Jaffee, D. Fair Trade Coffee, Sustainability, and Survival, 1st ed.; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2007; Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1pp2mq (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Schlosberg, D. Defining Environmental Justice; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellow, D.N. Total Liberation: The Power And Promise of Animal Rights and the Radical Earth Movement; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2015; Volume 24, pp. 840–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; Volume 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira González, I.; Urrútia, G.; Alonso-Coello, P. Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis: Scientific Rationale and Interpretation. Rev. Española Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2011, 64, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobrido Prieto, M.; Rumbo-Prieto, J.M. The systematic review: Plurality of approaches and methodologies. Enfermería Clínica (Engl. Ed.) 2018, 28, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; Higgins, J.P.; Sterne, J.A. Assessing risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 349–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, K. The Dialectics of Equity: Consumer Citizenship and the Extension of Water Supply in Medellín, Colombia. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2013, 103, 1176–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, S. Fair trade towns USA: Growing the market within a diverse economy. J. Polit. Ecol. 2014, 21, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsiger, P. Between shaming corporations and promoting alternatives: The politics of an ‘ethical shopping map’. J. Consum. Cult. 2014, 14, 218–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovantseva, N.; Fitzpatrick, C. Barriers to electronics reuse of transboundary e-waste shipment regulations: An evaluation based on industry experiences. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 102, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingston, L.N.; Guellil, J. TOMS and the Citizen-Consumer: Assessing the Impacts of Socially-Minded Consumption. J. Hum. Rights Pract. 2016, 8, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, I. Recomposing consumption: Defining necessities for sustainable and equitable well-being. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2017, 375, 20160379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladhari, R.; Tchetgna, N.M. Values, socially conscious behaviour and consumption emotions as predictors of Canadians’ intent to buy fair trade products. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 41, 696–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argüelles, L.; Anguelovski, I.; Dinnie, E. Power and privilege in alternative civic practices: Examining imaginaries of change and embedded rationalities in community economies. Geoforum 2017, 86, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hoop, E.; Jehlička, P. Reluctant pioneers in the European periphery? Environmental activism, food consumption and ‘growing your own. Local Environ. 2017, 22, 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo, L.R. El desarrollo de las ONG de México y su coincidencia con los Objetivos para el Desarrollo Sostenible de Naciones Unidas. CIRIEC-Espana Revista de Economia Publica Social y Cooperativa 2017, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolosa, A.; Irizar, M.; Martínez, E. An approach to consequences of market orientation in the Basque social Economy fostering public service. CIRIEC-Espana Revista de Economia Publica Social y Cooperativa 2017, 89, 55–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hankammer, S.; Kleer, R. Degrowth and collaborative value creation: Reflections on concepts and technologies. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 1711–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobato-Calleros, M.O.; Fabila, K.; Shaw, P.; Roberts, B. Quality assessment methods for index of community sustainability. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2018, 24, 1339–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, M.T.; Foroudi, P.; Tortora, D.; Hussain, S.; Melewar, T.C. Celebrity endorsement and the attitude towards luxury brands for sustainable consumption. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Wham, C.; Burlingame, B. New zealand’s food system is unsustainable: A survey of the divergent attitudes of agriculture, environment, and health sector professionals towards eating guidelines. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, D.; Southerton, D. After Paris: Transitions for sustainable consumption. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2019, 15, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-De los Salmones, M.D.M.; Perez, A. The role of brand utilities: Application to buying intention of fair trade products. J. Strateg. Mark. 2019, 27, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, M.; Pătărlăgeanu, S.R.; Petrariu, R.; Constantin, M.; Potcovaru, A.M. Empowering sustainable consumer behavior in the eu by consolidating the roles of waste recycling and energy productivity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana, R.; Glozer, S.; Eckhardt, G.M. ‘Alternative Hedonism’: Exploring the Role of Pleasure in Moral Markets. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 166, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, P.; Lavega, S.R. Social and solidary economy law in uruguay: Text and context. CIRIEC-Espana, Revista Juridica de Economia Social y Cooperativa 2020, 2020, 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, A.J.; Elliott, V.; Phang, S.C.; Claussen, J.E.; Harrison, I.; Murchie, K.J.; Steel, E.A.; Stokes, G.L. Inland fish and fisheries integral to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Res. 2020, 3, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalba-Eguiluz, U.; Egia-Olaizola, A.; de Mendiguren, J.C.P. Convergences between the social and solidarity economy and sustainable development goals: Case study in the Basque Country. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Govindan, K.; Xie, X. How fairness perceptions, embeddedness, and knowledge sharing drive green innovation in sustainable supply chains: An equity theory and network perspective to achieve sustainable development goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 120950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garwood, K.C.; Steingard, D.; Balduccini, M. Dynamic collaborative visualization of the united nations sustainable development goals (SDGs): Creating an SDG dashboard for reporting and best practice sharing. In VISIGRAPP 2020, Proceedings of the 15th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications, Valletta, Malta, 27–29 February 2020; SciTePress: Setúbal, Portugal, 2020; pp. 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rommel, J.; Radtke, J.; von Jorck, G.; Mey, F.; Yildiz, Ö. Community renewable energy at a crossroads: A think piece on degrowth, technology, and the democratization of the German energy system. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 1746–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, O.; Relan, A.; Shaghaghi, N. GoodBuys. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference, GHTC 2020, Seattle, WA, USA, 29 October 2020–1 November 2020; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathai, M.V.; Isenhour, C.; Stevis, D.; Vergragt, P.; Bengtsson, M.; Lorek, S.; Mortensen, L.F.; Coscieme, L.; Scott, D.; Waheed, A.; et al. The Political Economy of (Un)Sustainable Production and Consumption: A Multidisciplinary Synthesis for Research and Action. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 167, 105265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olwig, M.F. Sustainability superheroes? For-profit narratives of ‘doing good’ in the era of the SDGs. World Dev. 2021, 142, 105427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatipoglu, B.; Inelmen, K. Effective management and governance of Slow Food’s Earth Markets as a driver of sustainable consumption and production. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1970–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morell, M.F.; Espelt, R.; Cano, M.R. Expanded abstract Platform cooperativism: Analysis of the democratic qualities of cooperativism as an economic alternative in digital environments. CIRIEC-Espana Revista de Economia Publica Social y Cooperativa 2021, 102, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanova, S.; Cvar, N.; Verhovnik, J.; Božić, N.; Trilar, J.; Kos, A.; Stojmenova Duh, E. Rural Digital Innovation Hubs as a Paradigm for Sustainable Business Models in Europe’s Rural Areas. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S. Does Generation Z value and reward corporate social responsibility practices? J. Mark. Manag. 2022, 38, 903–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaskhely, M.K.; Qazi, S.W.; Khan, N.R.; Hashmi, T.; Chang, A.A.R. Understanding the Impact of Green Human Resource Management Practices and Dynamic Sustainable Capabilities on Corporate Sustainable Performance: Evidence from the Manufacturing Sector. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 844488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, J. Fairness Concern in Remanufacturing Supply Chain—A Comparative Analysis of Channel Members’ Fairness Preferences. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sänger, J. Stepping up on climate action—How can book sector associations support businesses in reducing CO2 emissions? Inf. Serv. Use 2023, 44, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, D.A. What’s to Eat and Drink on Campus? Public and Planetary Health, Public Higher Education, and the Public Good. Nutrients 2023, 15, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, J.C.; Leeflang, P.S.H. Thriving through turbulence: Lessons from marketing academia and marketing practice. Eur. Manag. J. 2023, 41, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Theodosiou, M.; Nilssen, F.; Eteokleous, P.; Voskou, A. Evaluating MNEs’ role in implementing the UN Sustainable Development Goals: The importance of innovative partnerships. Int. Bus. Rev. 2024, 33, 102259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisquert I Pérez, K.M.; Meira Cartea, P.Á.; Agúndez Rodríguez, A. Ecocitizenship and Food Consumption Education. Socio-Educational Good Practices in Citizen Initiatives of Responsible Consumption. Pedagog. Soc. 2023, 42, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, M.K.; Garizurieta, J.; González, R.; Infante, L.Á.; Horna, M.; Rivera, R.; Clotet, R. A Long-Distance WiFi Network as a Tool to Promote Social Inclusion in Southern Veracruz, Mexico. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Bothra, N. Is CSR still optional for Luxury Brands, or can they afford to ignore it? Int. J. Exp. Res. Rev. 2023, 35, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, L.; Michalke, A.; Gaugler, T.; Stoll-Kleemann, S. Sustainability Science Communication: Case Study of a True Cost Campaign in Germany. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez Chacón, E.; Salinas Gainza, F.R. Difficulties for the integration of the circular economy in the strategic sustainable management of SMEs in Arequipa, Peru. Eur. Public Soc. Innov. Rev. 2024, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah, M.K.; Dordaah, J.N.; Sam, A.; Amaning, N. Modelling the implications of sustainable supply chain management practises on firm performance: The mediating role of green performance. Cogent Eng. 2024, 11, 2370898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, P.; Belal, H.M.; Talapatra, S. Driving Toward Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the Ready-Made Garments (RMGs) Sector: The Role of Digital Capabilities and Operational Transparency. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 14071–14082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Song, Z.; Fong, K.Y. Perceived Price Fairness as a Mediator in Customer Green Consumption: Insights from the New Energy Vehicle Industry and Sustainable Practices. Sustainability 2025, 17, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olushola Adeborode, K.; Dora, M.; Umeh, C.; Hina, S.M.; Eldabi, T. Leveraging organisational agility in B2B ecosystems to mitigate food waste and loss: A stakeholder perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2025, 125, 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, K.; McCauley, D.; Heffron, R.; Stephan, H.; Rehner, R. Energy justice: A conceptual review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 11, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, N.; Barry, J. Politicizing energy justice and energy system transitions: Fossil fuel divestment and a ‘just transition’. Energy Policy 2017, 108, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs, C.C. Embeddedness and local food systems: Notes on two types of direct agricultural market. J. Rural Stud. 2000, 16, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mount, P. Growing local food: Scale and local food systems governance. Agric. Human Values 2012, 29, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seele, P.; Gatti, L. Greenwashing Revisited: In Search of a Typology and Accusation-Based Definition Incorporating Legitimacy Strategies. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, E.F. Small Is Beautiful: Economics as If People Mattered; Borgo Press: San Bernardino, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. In Proceedings of the 2000 ACM conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2–6 December 2000; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2000; p. 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulgan, G. Social Innovation: How Societies Find the Power to Change; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2019; p. 228. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, J.; York, H.; Graetz, N.; Woyczynski, L.; Whisnant, J.; Hay, S.I.; Gakidou, E. Measuring and forecasting progress towards the education-related SDG targets. Nature 2020, 580, 636–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G. Democratic Innovations; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicchieri, C. Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure, and Change Social Norms; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. Post Growth: Life After Capitalism; Polity Press: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Dimension | Theoretical Basis | Key Components | Application in Responsible Consumption |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Distributive Equity | Rawls (1971) [23] —Theory of Justice | Redistribution of economic resources; equitable access to goods/services; opportunities for disadvantaged groups | Tiered tariffs; cross-subsidies; labor inclusion of vulnerable groups |

| 2. Capability Equity | Sen (1999) [24]—Capability Approach | Agency-building; development of human and social capital; expansion of substantive freedoms | Training programs; organizational strengthening; community empowerment |

| 3. Recognition Equity | Fraser (2009) [27]—Theory of Recognition | Valuation of cultural identities; combating systemic stigmatization; symbolic inclusion | Ethical certifications; fair trade; recognition of traditional producers |

| 4. Procedural Equity | Participatory Justice Theories | Access to decision-making; democratization of governance; effective political voice | Participatory governance; cooperatives; deliberative councils; multi-stakeholder forums |

| 5. Environmental Equity | Ecological Justice (Schlosberg, 2007 [29]) | Equitable distribution of environmental benefits/burdens; protection of vulnerable communities | Responsible localization; environmental monitoring; conservation of natural resources |

| 6. Contextual Equity | Territorial Justice Theories | Adaptation to local specificities; geographic/territorial diversity; respect for local knowledge | Contextualized design; respect for cultural traditions; territorial governance |

| PEO Category | Keyword | Suggested Search String |

|---|---|---|

| P (Population) | Organizations | (“organization*” OR “company*” OR “firm*” OR “business” OR “corporate”) |

| E (Exposure) | Responsible consumption | (“responsible consumption” OR “sustainable consumption” OR “ethical consumption”) |

| O (Outcome) | Equity/Reduction in inequality | (“equity” OR “social justice” OR “inequality” OR “inclusion”) |

| Thematic Cluster | Categories Included | Representative Initiatives | Main Quotes | Predominant Types of Organization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equitable access and social justice |

|

| [38,41,57,59,77] | Public; Social |

| Participation and democratic governance |

|

| [38,47,48,58,78] | Public; Social |

| Ethical trade and value chains |

|

| [39,40,54,57,60,78,79,81] | Public; Social; Private |

| Circular production and consumption |

|

| [41,45,52,55,66,71,84] | Private; Social; Public |

| Energy and sustainable mobility |

|

| [45,52,53,55,62] | Social; Public |

| Food and local production |

|

| [39,46,66,73,76] | Social; Public |

| Conservation and environmental management |

|

| [38,47,58,78] | Public; Social; Private |

| Business models and sustainable innovation |

|

| [42,49,56,69,74,83] | Private |

| Technology for sustainability |

|

| [52,61,67,68,82] | Private; Social |

| Education and cultural transformation |

|

| [39,40,43,63,64,74] | Public; Social; Private |

| Collaborative spaces |

|

| [45,49,55] | Social; Public |

| Thematic Cluster | Representative Initiatives | Impact on Social Equity | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equitable access and social justice | Extension of basic services; Tiered rates; Bridging the digital divide; Job placement; Universal basic income |

| [38,41,57,59,77] |

| Participation and democratic governance | Community participatory mechanisms; Democratization of decision-making; Participatory methodologies; Collaborative working groups |

| [38,43,47,61,62,75] |

| Ethical trade and value chains | Fair trade promotion; Certification assessment; Transparent labeling; Sustainable supply chains |

| [39,40,44,54,60,63,79,81] |

| Circular production and consumption | Product reuse; Return systems; Waste management; Remanufacturing; Plastic reduction; Anti-waste |

| [41,55,66,71,80,84] |

| Energy and sustainable mobility | Energy cooperatives; Emissions reduction; Energy efficiency; Shared mobility |

| [45,52,53,62] |

| Food and local production | Urban gardens; Local consumption campaigns; Producer markets; Alternative channels; Sustainable institutional food |

| [46,59,66,73,76] |

| Conservation and environmental management | Ecosystem conservation; Responsible fishing practices; Comprehensive socio-environmental programs |

| [47,58,82] |

| Business models and sustainable innovation | Models with social impact; Sustainable marketing; CSR programs; Product co-creation; Ethical tourism |

| [42,56,69,74,78,83] |

| Technology for sustainability | Collaborative economy platforms; Best practice platforms; Cooperative platforms; Rural digital hubs |

| [49,52,67,68,82] |

| Education and cultural transformation | Raising awareness about responsible consumption; Educational tools; Thematic events; Differentiated taxes; Promoting a sufficient life |

| [39,40,43,44,63,64,74] |

| Collaborative spaces | Sustainable community spaces; Fab Labs and maker spaces; Shared infrastructure; Co-living and co-working |

| [45,49,55] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Salirrosas, E.E.; Acevedo-Duque, A.; Millones-Liza, D.Y. A Taxonomy of Responsible Consumption Initiatives and Their Social Equity Implications. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10672. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310672

García-Salirrosas EE, Acevedo-Duque A, Millones-Liza DY. A Taxonomy of Responsible Consumption Initiatives and Their Social Equity Implications. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10672. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310672

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Salirrosas, Elizabeth Emperatriz, Angel Acevedo-Duque, and Dany Yudet Millones-Liza. 2025. "A Taxonomy of Responsible Consumption Initiatives and Their Social Equity Implications" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10672. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310672

APA StyleGarcía-Salirrosas, E. E., Acevedo-Duque, A., & Millones-Liza, D. Y. (2025). A Taxonomy of Responsible Consumption Initiatives and Their Social Equity Implications. Sustainability, 17(23), 10672. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310672