Abstract

Digital Transformation (DTN) and Social Media Use (SMU) are reshaping how firms pursue competitiveness and sustainability. Yet, their combined effects on Sustainable Business Performance (SBP)—particularly in emerging-market retail contexts—remain insufficiently explored. This study contributes to closing this gap by exploring how DTN and SMU jointly enhance SBP through interrelated organizational capabilities: Collaboration Networks (CNS), Service Innovation (SIN), Customer Experience (CEX), Organizational Resilience (ORE), and Competitive Advantage (CAE). A dual-method design was adopted. In Phase 1, twenty-three experts participated in a three-round electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) process, during which Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) clustering was used to refine forty-seven indicators and validate expert consensus. The integration of e-Delphi and FCM clustering introduces a novel approach to consensus validation, enhancing methodological rigor. In Phase 2, survey data from 982 Thai retail executives were evaluated employing Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). The results revealed that DTN and SMU significantly improve SBP when mediated by SIN, CEX, and ORE. Specifically, SMU fosters CNS and SIN, whereas DTN strengthens CEX and CAE. Theoretically, this study integrates the Resource-Based View (RBV) and Dynamic Capabilities Theory (DCT); empirically, it provides rare large-scale evidence from Thailand’s retail industry; and practically, it positions DTN as a driving force behind innovation, resilience, and inclusive development consistent aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

1. Introduction

The accelerated wave of Digital Transformation (DTN) and the pervasive Social Media Use (SMU) are redefining how retail organizations achieve long-term competitiveness and sustainability [1,2]. In today’s retail landscape, digital adoption has evolved beyond operational efficiency to become a strategic pathway toward Sustainable Business Performance (SBP) [3]—encompassing economic, social, and environmental dimensions [4].

Global frameworks such as the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the emergence of Industry 5.0 emphasize the integration of technology with human-centric values, adaptability, and resilience [5,6]. Recent disruptions—including financial crises, pandemics, climate volatility, and supply chain fragmentation—have further unveiled the fragilities inherent in established retail frameworks and underscored the imperative of developing enduring performance mechanisms [7].

Despite increasing digital investments, many retailers in emerging markets—particularly in Thailand—continue to struggle with translating digital initiatives into sustainable value creation [8]. While prior studies have examined how DTN and SMU enhance customer experience and operational outcomes, their integrated impact on sustainability remains inconclusive and context-dependent [9,10].

In Thailand, digital transformation often manifests as technology-driven modernization rather than strategic renewal of business capabilities [11]. This narrow implementation limits its potential to foster innovation, resilience, and competitive advantage. Moreover, there is limited empirical evidence linking DTN and SMU to SBP through mediating mechanisms such as Collaboration Networks (CNS), Service Innovation (SIN), Customer Experience (CEX), and Organizational Resilience (ORE) within the retail industry—where diverse formats and competitive pressures demand adaptive strategies.

This study addresses this research void by designing and validating a mixed-method framework that integrates e-Delphi–Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) clustering with Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to examine how DTN and SMU collectively drive SBP through dynamic capabilities. The research advances theoretical understanding within the Resource-Based View (RBV) and Dynamic Capabilities Theory (DCT) nexus and delivers strategic implications for retail executives and policy authorities striving to attain enduring competitive advantage within fast-changing digital contexts.

2. Literature Review

The accelerating pace of digitalization has reshaped business environments, compelling firms to adopt technologies such as social media and digital platforms to remain competitive [12]. Prior research has highlighted the relevance of digital adoption in improving consumer engagement, inventiveness within organizations, and long-term competitiveness [13,14]. Simultaneously, sustainability imperatives urge organizations to integrate ecological, social, and economic goals into their strategies, with the retail sector facing particular pressure due to its close interaction with consumers and resource-intensive operations [15]. Despite extensive work, the existing literature remains fragmented and inconsistent [16]. Some studies emphasize the benefits of DTN and SMU in promoting innovation and customer-centricity, while others argue that their effects on SBP are limited without complementary capabilities and contextual adaptation [17]. This inconsistency underscores the need for a multi-theoretical perspective that accounts not only for resource possession but also for the dynamic processes that convert resources into performance outcomes [12]. This study addresses this gap by combining the RBV and DCT to demonstrate how DTN and SMU function as strategic resources that generate capabilities such as SIN, CEX, CNS, and ORE. Collectively, these capabilities contribute to Competitive Advantage (CAE) and ultimately to SBP [12]. To strengthen methodological rigor, the study applies a dual-method approach combining FCM clustering and SEM [18]. The following subsections review the relevant literature and formulate hypotheses based on this integrated framework.

2.1. Social Media Use

Social Media Use (SMU) has become a pivotal digital resource in contemporary business, enabling firms to enhance customer engagement, facilitate knowledge sharing, and expand collaboration across organizational boundaries [19]. In retail settings, where consumer preferences change rapidly, SMU plays a critical role in connecting firms with customers in real time, cultivating brand communities, and amplifying marketing effectiveness [20]. Evidence suggests that SMU strengthens customer orientation, market responsiveness, and relational capital, all of which are essential for firms in emerging markets that face intense competition and resource constraints [12]. However, despite these recognized benefits, findings remain mixed regarding SMU’s direct contribution to SBP [21]. Some studies show that SMU enhances innovation and long-term competitiveness by improving market orientation and consumer trust [22]. Others caution that without complementary organizational capabilities, its effects are short-lived and vulnerable to imitation, highlighting the challenge of transforming digital presence into sustained value [12]. This inconsistency indicates that SMU alone may be insufficient to guarantee sustainable outcomes, especially in volatile contexts where adaptability and resilience are essential. From the perspective of the RBV, SMU can be considered as a valuable, rare, and potentially inimitable resource [12,23]. However, DCT emphasizes that firms must develop mechanisms that enable them to sense, seize, and reconfigure digital opportunities for lasting impact [24]. Accordingly, SMU transcends its conventional role as a communication mechanism, emerging as a strategic enabler that underpins the development of CNS and propels SIN [25]. Thus, the subsequent hypotheses are proposed:

H1.

Social media use positively influences collaboration networks.

H2.

Social media use positively influences service innovation.

2.2. Digital Transformation

Digital transformation (DTN) has grown to be the backbone of cutting-edge company direction, reshaping processes, structures, and value delivery through leveraging cutting-edge digital innovation [26]. In the retail industry, DTN is critical for enhancing efficiency, enabling data-driven decision-making, and supporting customer-centric innovation [27]. Scholars emphasize that DTN is not limited to technological upgrades; it requires strategic alignment of digital resources with organizational culture, leadership, and capabilities to achieve sustainable impact [28]. Particularly in emerging economies, DTN helps firms overcome resource scarcity by leveraging digital infrastructures to achieve scalability, agility, and market responsiveness. Despite its potential, empirical evidence regarding DTN’s contribution to long-term performance remains inconsistent. Some studies confirm that DTN enhances competitiveness by improving knowledge integration, service personalization, and customer satisfaction [25]. Others caution that DTN initiatives often fail to deliver sustained outcomes when they are pursued as isolated technological investments without organizational reconfiguration or capability development [29]. This divergence highlights the need to understand DTN not only as a resource but as a catalyst of strategic renewal that requires complementary capabilities to yield enduring benefits [30]. From the perspective of the RBV, DTN constitutes a distinctive and hard-to-replicate capability that strengthens organizational competitiveness. DCT extends this view by emphasizing how organizations must sense digital opportunities, seize them through customer-centric strategies, and reconfigure resources to sustain CAE [12]. In retail, DTN enables firms to transform data and technology into improved service offerings and differentiated CEX, both of which are essential for achieving SBP [31]. On the basis of these arguments, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3.

Digital transformation positively influences competitive advantage.

H4.

Digital transformation positively influences customer experience.

2.3. Collaboration Networks

Collaboration Networks (CNS) are increasingly recognized as vital drivers of innovation and resilience in the digital era [32]. By fostering partnerships with suppliers, customers, and industry peers, firms can access external knowledge, share resources, and co-create solutions that enhance adaptability and long-term performance. In the retail sector, effective CNS strengthen supply chain integration, facilitate digital adoption, and enable firms to respond more effectively to dynamic customer demands [33]. Such networks are especially valuable in emerging markets, where resource scarcity and institutional uncertainty often hinder sustainable growth [34]. However, empirical findings remain inconclusive. Some studies report that collaboration enhances innovation outcomes and accelerating DTN, while others indicate that poorly managed networks may lead to dependency, knowledge leakage, or coordination challenges that weaken performance [35]. This suggests that networks themselves are not automatically beneficial; their effectiveness depends on how firms leverage them to build complementary capabilities [36]. From the perspective of the RBV, CNS provide access to valuable and rare resources beyond firm boundaries [37]. DCT extends this view by explaining how organizations integrate and reconfigure external resources into internal processes to support resilience and innovation. In this study, CNS are conceptualized as drivers of SIN and ORE, both of which serve as essential mechanisms linking external collaboration to SBP [12,38]. Drawing from the foregoing discussion, the subsequent hypotheses are suggested:

H5.

Collaboration networks positively influence service innovation.

H6.

Collaboration networks positively influence organizational resilience.

2.4. Service Innovation

Service innovation (SIN) is a key mechanism through which firms differentiate themselves, enhance customer value, and strengthen long-term competitiveness [39]. It involves the creation of new or improved service processes, delivery methods, and customer interactions that respond to evolving market demands and technological opportunities [40]. In the retail industries, SIN has become crucial for integrating digital channels, personalizing CEX, and co-creating value with stakeholders—thereby supporting sustainability-oriented strategies [41]. Moreover, SIN contributes to knowledge sharing and organizational learning, enabling firms to adapt quickly in uncertain and competitive environments [42]. Despite its recognized importance, empirical evidence on SIN and firm performance remains varied [43]. Some studies find that SIN enhances resilience and competitiveness by fostering adaptability and resource integration. Others caution that without sufficient absorptive capacity and strategic alignment, SIN may lead to increased costs or fragmented service quality, reducing its long-term contribution to sustainable outcomes [44]. This reflects the notion that SIN is not inherently beneficial; its effectiveness depends on how organizations orchestrate internal and external resources to fully realize their potential value [45]. From the RBV, SIN can be seen as a valuable and inimitable capability that extends the benefits of digital resources [46]. DCT explains how SIN enables firms to seize opportunities, translate knowledge into practice, and renew business models for sustained growth [12,47]. In this study, SIN is positioned as a mediator that strengthens ORE and CAE, thereby contributing to SBP. Drawing from the reviewed literature, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H7.

Service innovation positively influences organizational resilience.

H8.

Service innovation positively influences competitive advantage.

2.5. Customer Experience

Customer Experience (CEX) has emerged as a central concept in the digital economy, reflecting the cumulative perceptions, emotions, and interactions that customers associate with a firm’s products and services [48]. In competitive retail environments, CEX serves as a differentiating factor that influences customer satisfaction, loyalty, and advocacy [49]. Effective management of CEX allows firms to deliver consistent value across multiple touch points, integrate digital platforms into service delivery, and strengthen brand positioning in increasingly saturated markets [25]. Moreover, CEX has been linked to higher levels of trust, engagement, and co-creation, all of which are vital for long-term sustainability. Despite its recognized importance, research remains divided into the extent to which CEX directly contributes to SBP [50]. Some studies demonstrate that positive CEX enhances firm resilience and competitiveness by creating enduring customer relationships. Others caution that its improvements benefits may be short-lived or costly if not supported by robust organizational processes and digital alignment, potentially limiting its of impact on SBP [25]. This suggests that CEX is most effective when integrated into broader strategic and capability-building initiatives, rather than treated as an isolated outcome [51]. From the perspective of RBV, CEX can be considered a strategic outcome of leveraging digital resources, representing an organization’s capacity to provide unique and inimitable value [46]. DCT underscores how CEX embodies an organization’s competence in perceiving and adjusting to dynamic customer requirements and optimizing resources in accordance with market expectations [12,52]. In this framework, CEX serves as a pivotal mechanism through which DTN enhances SBP. Considering these insights, the subsequent hypothesis is established:

H9.

Customer experience positively influences sustainable business performance.

2.6. Organizational Resilience

Organizational resilience (ORE) is described as the capacity of an organization to foresee, take in, and adjust to unforeseen events while maintaining objectives and long-term viability [23]. In increasingly uncertain environments, resilience has become essential for sustaining CAE and ensuring business continuity [12,53]. Within the retail industry, ORE empowers companies to cope with disruptions like supply chain disruptions, economic crises, and rapid shifts in consumer demand, while continuing to deliver value. Resilient organizations leverage collaboration, digital tools, and flexible processes to recover faster and transform adversity into opportunities for growth [54]. Despite its recognized importance, findings on the mechanisms through which ORE influences performance are mixed [55]. Some studies indicate that ORE enhances competitiveness and innovation by strengthening a firm’s adaptive capacity and learning orientation [56]. Others suggest that ORE alone may not guarantee sustained outcomes unless integrated with broader strategic resources and dynamic capabilities, such as DTN and SIN [12,57]. This suggests that ORE is most effective when combined with complementary capabilities that enable firms to transform ORE into tangible CAE [58]. From the RBV, ORE is considered an intangible capability that enhances the strategic contribution of firm assets [12]. DCT elaborates on this notion by showing how resilience supports the adjustment of resources and operations to navigate environmental turbulence [59]. In this study, ORE is conceptualized as a key mediator that links CNS and SIN to CAE and SBP. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H10.

Organizational resilience positively influences competitive advantage.

H11.

Organizational resilience positively influences sustainable business performance.

2.7. Competitive Advantage

Competitive Advantage (CAE) is widely acknowledged and recognized as the foundation for achieving sustained superior performance [12]. It demonstrates an organization’s capacity to achieve distinctiveness through unique resources, superior capabilities, and strategic positioning, enabling it to outperform rivals in dynamic environments [25,60]. In the retail sector, CAE may stem from digital adoption, service innovation, or customer-centric strategies that improve efficiency, responsiveness, and value creation [61]. Firms that successfully develop CAE are more capable of sustaining long-term growth and aligning business models with sustainability objectives [62]. Despite its central role, empirical studies present varied evidence regarding how CAE translates into sustainable outcomes. Some scholars argue that CAE drives financial, social, and environmental performance by ensuring resource efficiency and differentiation [62]. Others caution that CAE may be short-lived if based solely on technology or market positioning, as competitors can quickly imitate or neutralize such advantages [12]. This indicates that CAE must be grounded in organizational assets and capacities that are valuable, scarce, difficult to replicate, and lack viable alternatives, thereby ensuring long-term sustainability [63]. From the RBV, CAE represents the strategic outcome of deploying firm-specific resources [64]. DCT complements this view by emphasizing the importance of renewing and reconfiguring resources to sustain CAE in turbulent environments [12]. Within this framework, CAE serves as the immediate precursor to SBP, linking DTN, SIN, and ORE to enduring competitive outcomes. Grounded in the above reasoning, the following hypothesis is derived:

H12.

Competitive advantage enhancement positively influences sustainable business performance.

2.8. Sustainable Business Performance

Sustainable Business Performance (SBP) captures an organization’s capacity to achieve enduring prosperity by integrating monetary, social, and ecological objectives into its strategic and operational activities [65]. Unlike traditional measures of performance that focus primarily on short-term financial returns, SBP emphasizes the creation of enduring long-term value for multiple stakeholders, aligning closely with global agendas such as the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [66]. In the retail sector, SBP requires firms to balance profitability with responsible practices in supply chain management, resource efficiency, and customer engagement [67]. By embedding sustainability into core strategies, firms can build stronger reputations, foster stakeholder trust, and improve resilience in volatile environments [62]. Despite its growing importance, empirical research on SBP remains fragmented. Some studies demonstrate that integrating sustainability enhances long-term competitiveness, innovation, and market positioning [68]. Others caution that sustainability initiatives can be costly or symbolic, producing limited benefits if not properly aligned with organizational capabilities and market conditions [69]. This divergence emphasizes the necessity of exploring the underlying pathways through which DTN, SMU, and dynamic capabilities drive SBP. From the RBV, SBP reflects the successful deployment of valuable and inimitable resources that sustain firm survival and growth [70]. DCT adds that organizations must continuously adapt, reconfigure, and integrate resources to achieve sustainable outcomes [24]. Within this framework, SBP is the ultimate performance construct, linking digital adoption and organizational capabilities to long-term value creation and competitiveness.

2.9. Multi-Theoretical Framework (The RBV and DCT Integration)

Drawing upon the complementary insights of the Resource-Based View (RBV) and Dynamic Capability Theory (DCT), this study develops an integrated theoretical framework that explains how DTN and SMU jointly drive SBP in the retail sector. The RBV provides the basis for comprehending how businesses employ key assets to attain CAE, whereas the DCT highlights how those resources are continuously reconfigured to maintain competitiveness in dynamic environments [71].

Originally proposed by Wernerfelt [72], the RBV asserts that organizations achieve a competitive advantage by possessing resources that are valuable, rare, difficult to imitate, and lacking viable substitutes. In this study, DTN and SMU exemplify such strategic digital resources as they enhance knowledge sharing, strengthen market orientation, and support distinctive service offerings. However, RBV has been critiqued for its static orientation, as it assumes that resource value remains constant and underestimates the effects of environmental turbulence [73].

DCT broadens the RBV by highlighting an organization’s capacity to sense, seize, and reorganize resources to SBP amid uncertainty [74,75]. In the retail context, DCT explains how firms transform digital resources into SIN, CEX, and ORE, which collectively enhance SBP. By focusing on adaptive processes rather than static assets, DCT captures how firms innovate and thrive amid digital disruption, market volatility, and sustainability pressures [76].

The integration of RBV and DCT provides a dynamic and process-oriented lens that explains how digital resources are transformed into sustainable outcomes. Specifically, RBV describes the possession of strategic assets (DTN and SMU), while DCT explicates the mechanisms by which these assets are mobilized into higher-order dynamic capabilities—represented in this study by CNS, SIN, CEX, and ORE—that collectively reinforce CAE and SBP. This transformation follows a sequential logic: digital resources → dynamic capabilities → competitive advantage → sustainable business performance. The mediating constructs proposed in this model thus function as operational pathways that embody the RBV–DCT synergy.

Moreover, this study extends prior RBV–DCT research by recognizing the boundary conditions that moderate this transformation process. Organizational culture, managerial digital literacy, and infrastructure readiness can either enable or constrain how effectively firms sense and seize digital opportunities. By situating these factors within Thailand’s emerging-market retail ecosystem, the framework emphasizes that the value of digital transformation depends not only on resource possession but also on contextual adaptability and institutional maturity.

Integrating the RBV and DCT offers a complementary foundation for this study [77,78]. RBV conceptualizes DTN and SMU as critical digital resources [79], while DCT elucidates how these resources evolve into dynamic capabilities—including CNS, SIN, CEX, and ORE—that foster CAE and ultimately drive SBP. This integration is particularly relevant in emerging markets such as Thailand, where firms face both resource constraints and institutional uncertainty, requiring strategies that combine resource accumulation with adaptive capability development.

Taken together, the RBV–DCT framework advances a unified theoretical perspective—termed digital resource orchestration—that captures how firms deploy and renew digital assets through dynamic capabilities to achieve sustainable competitiveness.

Building upon the RBV–DCT integration, recent digital transformation research emphasizes the need to move beyond static conceptualizations of digital capabilities toward a more process-oriented understanding of how digital resources are mobilized, aligned, and reconfigured over time. This perspective highlights an emerging form of digital resource orchestration wherein strategic digital assets such as DTN and SMU initiate capability-building sequences that unfold through sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring activities. Such orchestration logic provides a dynamic explanation for how firms convert digital resources into relational, innovative, and adaptive capabilities, ultimately shaping competitive and sustainability outcomes. This theoretical grounding establishes a conceptual bridge to the capability-development pathways further elaborated in the Discussion Section, where the study’s integrative perspective is formalized.

2.10. Fuzzy C-Means Theory

Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) is a soft clustering algorithm that extends classical K-means by allowing each data point to belong to multiple clusters with varying degrees of membership [80]. Originating from fuzzy set theory introduced by Zadeh and later formalized by Bezdek et al. [81], FCM uses iterative optimization to minimize the distance between data points and cluster centroids. This fuzzy partitioning method adeptly captures uncertainties and overlapping boundaries often missed by traditional clustering methods, thereby improving interpretive accuracy in intricate decision-making environments.

Unlike hard clustering, which allocates each observation exclusively to one cluster, FCM introduces a continuous membership function ranging from 0 to 1. This function represents the strength of association between an observation and each cluster [82], reflecting the ambiguity inherent in human judgment and supporting more realistic modeling of expert consensus [83]. In management and sustainability research, FCM has evolved beyond its engineering origins to serve as a consensus validation tool that transforms expert assessments into fuzzy membership values, providing nuanced insights into collective decision pattern [84]. In this study, FCM was integrated with the e-Delphi method to validate expert consensus. Expert evaluations were converted into fuzzy membership degrees, and weighted centroids were used to establish agreement thresholds. This hybrid approach balances subjective judgment with computational rigor, enhancing both methodological transparency and interpretive depth. The adapted single-centroid framework thus offers a novel methodological contribution for analyzing complex, multidimensional constructs in sustainability and management research.

2.11. Research Conceptual Framework

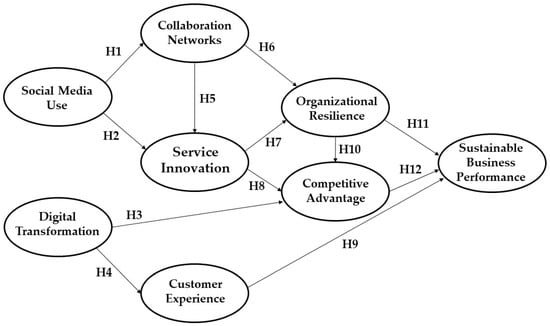

To clarify the theoretical logic underpinning this study, the integrated RBV-DCT framework summarized in Table 1 illustrates how digital resources and dynamic capabilities collectively shape sustainable business performance. Under the RBV perspective, DTN and SMU are positioned as strategic resources that provide technological and informational inputs, fostering knowledge integration and resource leverage across the organization. Within the DCT lens, these resources activate a progressive chain of adaptive and transformative mechanisms—CNS, SIN, CEX, and ORE—that convert digital inputs into dynamic agility, innovation, and learning [85]. CAE then operates as a strategic mediator that consolidates these dynamic capabilities into Sustainable Business Performance (SBP), the ultimate performance outcome [86].

Table 1.

Theoretical hierarchy and functional roles of constructs in the integrated RBV–DCT framework. (Source: Author).

Building upon this theoretical foundation, Figure 1 depicts the hierarchical and sequential nature of the proposed relationships. DTN and SMU serve as digital enablers that initiate the capability development process by facilitating knowledge acquisition, sharing, and utilization across digital platforms [87]. At the first tier of capability formation, CNS represent the relational infrastructure through which firms co-create value and exchange knowledge with external partners, forming the basis for organizational learning. Building on these network resources, SIN emerges as a second-tier capability that transforms shared knowledge into innovative services and operational processes. Together, CNS and SIN capture the exploratory dimension of dynamic capability development [88].

Figure 1.

Research conceptual framework illustrating the hierarchical mediation pathways linking digital resources (DTN, SMU), dynamic capabilities (CNS, SIN, CEX, ORE), strategic mediator (CAE), and performance outcome (SBP). (Source: Author).

At the next stage, CEX and ORE constitute adaptive capabilities that translate innovation outputs into customer value and organizational stability [89]. CEX reflects the firm’s ability to deliver personalized and digitally enabled experiences, while ORE reflects its capacity to absorb shocks and reconfigure resources under uncertainty. These two constructs jointly embody the exploitative dimension of dynamic capabilities by anchoring innovation within resilient and customer-centered systems.

Finally, CAE functions as a strategic consolidator, integrating innovation, experience, and resilience into sustained market strength and competitive positioning. SBP emerges as the terminal outcome, representing the fusion of economic, social, and environmental value creation consistent with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This hierarchical progression—digital resources → relational capabilities (CNS) → innovation (SIN) → adaptive capabilities (CEX, ORE) → strategic advantage (CAE) → performance (SBP)—captures the core principle of digital resource orchestration. It explains how Thai retail firms transform technological investments into sustainability-oriented capabilities through a layered sequence of capability building and reconfiguration.

3. Methodology

This research employed a dual-method strategy to examine the impact of DTN and SMU on SBP within the retail industry. The methodological framework combined both qualitative and quantitative phases to ensure methodological rigor and theoretical contribution. The qualitative phase integrated the e-Delphi technique with FCM clustering to refine and validate the conceptual model. Expert judgments were transformed into fuzzy membership values. In the subsequent quantitative phase, the proposed model was tested using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) [90] to assess construct reliability and validity, followed by Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to assess potential correlations.

This integrated approach reflects a dominant quantitative paradigm enriched by qualitative insights, providing an integrated perspective on the multifaceted dynamics linking digital technologies to firm performance. Notably, the integration of FCM clustering with SEM represents a methodological advancement, offering a robust framework for capturing expert consensus and testing dynamic relationships in retail environments undergoing accelerated DTN post-2020 [91].

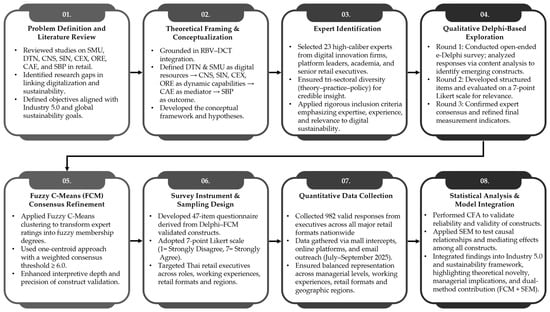

The comprehensive methodological process is visualized in Figure 2, illustrating the sequential flow from qualitative expert consensus formation (e-Delphi–FCM) to quantitative validation (CFA–SEM). The eight-steps—from defining research objectives, identifying experts, refining constructs, validating measures to integrating the model—demonstrates the application of methodological triangulation to ensure validity, robustness, and contextual relevance within Thailand’s retail industry.

Figure 2.

The structure of the research technique (Source: Author).

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Ethics Review Board of Rangsit University (COA. NO. RSUERB2025-068).

3.1. Qualitative Research

The qualitative phase was designed to establish a rigorous foundation for subsequent quantitative testing by integrating the e-Delphi technique with Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) clustering. This dual-method design served two primary purposes: (1) to capture structured expert judgment through iterative feedback, and (2) to apply fuzzy clustering to quantify consensus levels with greater precision than conventional methods [92]. This integration enhanced both validity and reliability, assuring that the preserved indicators were not only theoretically grounded but also practically applicable to the Thai retail context. The key result of this phase was a refined collection of constructs and measurement items, validated through expert consensus, that provided a robust starting point for the quantitative survey.

3.1.1. Population and Sampling

A purposive sampling strategy was employed to recruit 23 experts to validate the proposed framework and measurement items. This panel size exceeded the minimum threshold of 17 experts recommended by Macmillan (1971) [93], thereby ensuring acceptable error rates (<0.02) and enhancing the reliability of the consensus process. The expert panel was deliberately diverse, comprising: (1) seven university professors specializing in marketing, communication, and digital innovation, each with over five years of teaching experience; (2) seven practitioners from social media platforms, consulting firms, and marketing agencies, each with more than five years of industry experience; and (3) seven senior retail executives with over 15 years of managerial experience. This distribution ensured a balanced representation of academic, professional, and strategic perspectives, thereby strengthening the validity of the consensus process.

3.1.2. Research Instruments

Building on insights from the expert panel, the research instruments were refined through a structured three-round e-Delphi process, supported by FCM clustering. Expert evaluations were transformed into fuzzy membership degrees to capture varying levels of agreement, with the fuzzifier coefficient set at = 2.0 [94]. Consensus was defined as a weighted one centroid score of ≥6.0 on a seven-point Likert scale, enabling items to be accepted, revised, or rejected based on collective feedback [95].

This ≥6.0 criterion follows established practices in Delphi–FCM consensus research, where higher-threshold cutoffs are used to ensure stability of expert judgments and minimize the influence of dispersed ratings. In our pilot sensitivity checks, thresholds below 6.0 allowed items with substantial variability, whereas the ≥6.0 cutoff consistently retained indicators demonstrating strong, coherent, and methodologically defensible agreement suitable for subsequent SEM measurement.

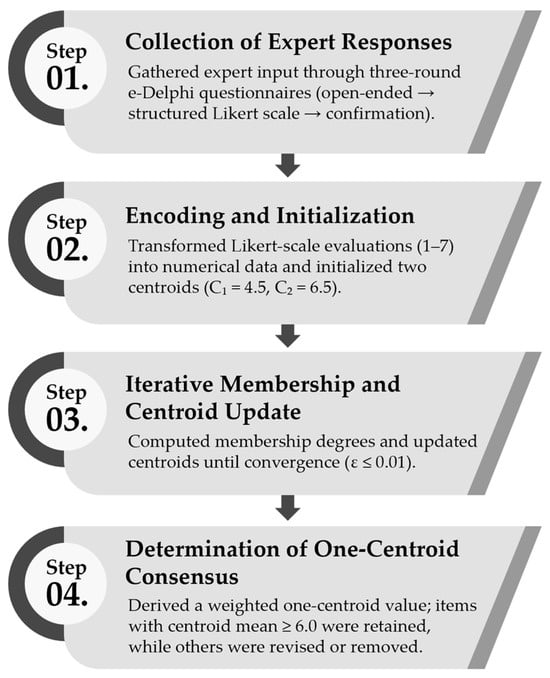

Unlike traditional Delphi approaches that require absolute agreement, the FCM procedure accommodates partial membership, providing a more nuanced and analytically robust assessment of consensus [96]. This process yielded a validated measurement framework that informed the CFA and SEM analysis in the quantitative phase. The four-step integration of e-Delphi with FCM is illustrated in Figure 3. This methodology ensured that only indicators supported by a high and stable level of expert agreement were advanced, thereby enhancing the content validity of the final survey instrument [97].

Figure 3.

Research process using e-Delphi and FCM clustering (Source: Author).

3.1.3. Data Collection

A systemic three-round electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) survey was conducted over a three-month period between April and June 2025. Administered via email, the survey ensured efficiency, accessibility, and consistency across participants. This iterative procedure employed sequential questionnaires, with each subsequent round refining and extending the insights obtained from prior responses.

Round 1 featured open-ended questions designed to elicit expert perspectives on construct completeness, indicator clarity, and potential areas for refinement. Following Round 1, a content analysis synthesized these inputs, ensuring that the questions and indicators were clearly defined and appropriately structured for the subsequent round. Round 2 introduced revised items, which were evaluated using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly irrelevant to 7 = strongly relevant) to assess their perceived relevance [98]. Round 3 presented controlled feedback and consolidated results, enabling experts to review aggregated responses and confirm consensus across all items.

This structured e-Delphi process ensured both the breadth and depth of expert contributions, while enhancing the stability of the final measurement framework. The systematic use of multi-round design allowed for iterative refinement, reduced ambiguity and ensured that the retained items reflected a strong consensus among the expert panel [99]. The final dataset was analyzed using FCM clustering to validate the degree of expert consensus.

3.1.4. Data Analysis

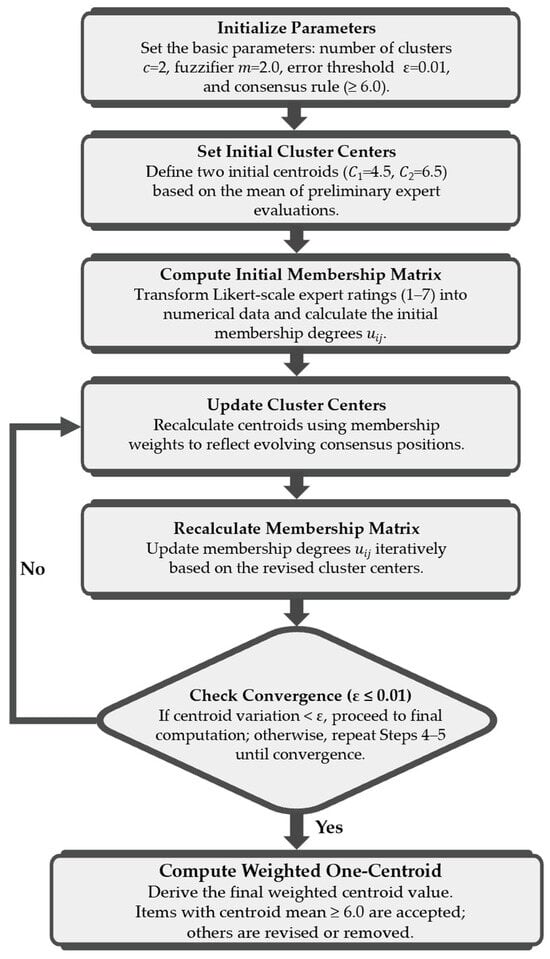

The proposed framework employed the Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) algorithm, a soft clustering method originally introduced by Bezdek (1984) [81], to evaluate the convergence of expert opinions across 47 observed variables. Unlike the K-means algorithm, which assigns each observation exclusively to a single cluster, FCM allows partial membership across multiple clusters, making it particularly suitable for expert-based evaluations, where judgments may not align perfectly with rigid categorical boundaries [82].

The algorithm iteratively minimizes an objective function to optimize both cluster centroids and membership degrees, thereby representing varying levels of expert agreement. In this study, the number of clusters was set to = 2 [100], corresponding to two initial cluster centers ( = 4.5 and = 6.5). The fuzzifier coefficient was set to = 2.0 to control the degree of fuzziness [100]. The stopping criterion (error threshold) was set at = 0.01, while the consensus threshold was determined at a weighted centroid mean of ≥6.0 on a 7-point Likert scale [98].

These parameter settings ensured computational stability and methodological rigor in deriving the final consensus structure. Table 2 summarizes the full configuration—including the number of clusters, fuzzifier coefficient, error threshold, initial centroids, and consensus rule—used in this study. Building on these configurations, the classical FCM procedure proceeds through four structured computational steps to derive the final one-centroid consensus, mathematically formulated as follows [101]:

Table 2.

Parameter settings for Fuzzy C-means clustering (Source: Author).

Step 1: Objective function minimization

The algorithm seeks to minimize the following objective function:

where is the membership degree of item in cluster , denotes the data point, represents the centroid of cluster , and is the fuzzifier coefficient ( = 2.0).

Step 2: Centroid update

Cluster centroids are updated using the following formula:

where represents the centroid of cluster , is the membership degree of item in cluster , denotes the data point, is the fuzzifier coefficient (set as 2.0 in this study), is the total number of data points, and is the number of clusters. In this study, two initial cluster centers were defined as = 4.5 and = 6.5 and iteratively updated until convergence. Once stability was achieved, these centroids were aggregated into a single weighted consensus centroid, representing the overall expert agreement.

Step 3: Membership update

Membership degrees are recalculated iteratively using the following formula:

where denotes the degree of membership of item in cluster . The term xi represents the data point, while and denote the centroids of clusters and , respectively. The parameter is the fuzzifier coefficient, which controls the degree of fuzziness in the clustering process. This iterative process updates membership values based on the relative distances of each data point to the cluster centroids, allowing items to partially belong to multiple clusters simultaneously. This iterative recalculation continues until the change in cluster centroid positions falls below the predefined error threshold ( = 0.01), indicating convergence. Once stability is achieved, a single weighted consensus centroid is computed to represent the final expert agreement.

Step 4: Consensus centroid aggregation

In the classical framework, convergence is achieved when membership matrices stabilize within a tolerance threshold, and the cluster with the highest degree of membership obtains the items. However, this study adapted the procedure to prioritize consensus validation over multi-cluster classification. After deriving individual centroids from clusters, the final consensus was consolidated into a single centroid using a weighted averaging procedure:

where indicates the centroid of cluster , and denotes the weight derived from membership degrees in that cluster. This produces a One Centroid value, which represents the collective consensus of expert judgments for each observed variable. These steps are repeated until the membership matrix converges, after which a single consensus centroid is computed as the final output. This adaptation transforms the conventional multi-cluster FCM output into a single consensus representation, enhancing interpretability and reducing the influence of outlier judgments. By consolidating all expert perspectives into one centroid, the method strengthens methodological transparency, improves convergence reliability, and establishes a robust foundation for subsequent quantitative validation. The overall procedure is summarized in Figure 4, which depicts the adapted FCM procedure for consensus validation.

Figure 4.

Consensus-oriented Fuzzy C-Means process for deriving one-centroid expert consensus (Source: Author).

3.2. Quantitative Research

The quantitative phase was designed to validate the integrated framework refined through the Delphi–FCM consensus process. Eight latent constructs and 47 observed indicators were operationalized into a structured online questionnaire, which yielded 982 valid responses from retail executives in Thailand. This dataset represents one of the most comprehensive samples in emerging market retail research. To ensure measurement rigor, a two-step SEM procedure was applied. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) assessed the reliability and validity of the measurement model [90], while Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) tested the hypothesized causal paths and mediating effects [102]. This dual approach advances prior sustainability research by combining consensus-driven scale development with hypothesis testing, thereby enhancing both methodological robustness and generalizability.

3.2.1. Population and Sampling

Given the complexity of the proposed model, sample size estimation was conducted rigorously in following established SEM methodological protocols. Hair et al. [103] recommend 10–20 responses per indicator, while Kline (2016) [102] suggests a minimum of 400 cases for complex models. Based on these criteria, the required sample size ranged between 470 and 940. This study obtained 982 valid responses, exceeding recommended thresholds and ensuring robust statistical power. Respondents represented diverse organizational roles, educational backgrounds, professional experiences, geographic regions, and retail formats, strengthening the representativeness and broader applicability of the findings.

3.2.2. Research Instruments

The survey methodology was refined based on the preceding e-Delphi–FCM phase and operationalized into eight validated constructs measured by 47 observed items. Each item employed a 7-point Likert scale (1 = “Strongly Disagree” to 7 = “Strongly Agree”) [98], capturing respondent perceptions of DTN, SMU, and a range of interrelated organizational capabilities—including CNS, SIN, CEX, ORE, CAE, and SBP. All items were directly derived from expert consensus and aligned with the study’s theoretical framework, thereby enhancing contextual validity and minimizing measurement error. The instrument was designed to capture both strategic and operational perspectives from retail executives across various hierarchical levels, offering a basis for subsequent CFA and SEM analyses.

3.2.3. Data Collection

A systematic online survey was conducted over a three-month period from July to September 2025, utilizing mall-based outreach, social networking channels, and direct email invitations. After rigorous screening procedures, 982 valid responses were retained from retail executives in Thailand, ranging from department heads to top executives. Respondents represented a wide range of demographic backgrounds, including gender, age groups, regional distribution across all major areas of Thailand, and varying levels of educational attainment and professional experience. Participants were drawn from various retail formats, including specialty stores, shopping centers, department stores, discount/hypermarkets, supermarkets, and convenience stores. This broad representation ensured a comprehensive cross-section of Thailand’s retail sector. This comprehensive data collection approach provided a strong empirical foundation for subsequent analyses.

3.2.4. Data Analysis

To verify the adequacy of the measurement model and ensure reliability and validity, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted as part of the data assessment process [90]. CFA evaluated factor loadings, CR, AVE, α, and R2, ensuring that all constructs met established thresholds (loadings ≥ 0.70, CR ≥ 0.70, AVE ≥ 0.50, α ≥ 0.70, R2 ≥ 0.20) [104]. Model fit was further evaluated using indices: CMIN/DF (≤3.0), AGFI, GFI, NFI, CFI, TLI (all ≥ 0.90) [105,106], along with RMSEA (<0.08) [107], and RMR (<0.05) [105]. These results confirmed the measurement quality of the eight constructs and 47 observed variables, establishing a statistically sound foundation for subsequent hypothesis testing through SEM. By combining a rigorous validation process with a comprehensive model assessment, this study offers strong empirical support to investigate the combined influence of DTN and SMU on SBP within Thailand’s retail industry.

4. Results

This study utilized a dual-method research design to validate and test the suggested framework, integrating both qualitative and quantitative approaches. The first phase drew on qualitative insights from 23 experts representing academia, digital transformation, social media, and retail practice. Using a structured three-round e-Delphi process combined with FCM clustering, the initial pool of items was refined, and consensus was established across all observed variables. This approach emphasized methodological rigor while capturing nuanced expert perspectives beyond the scope of traditional Delphi analysis. The second phase employed quantitative validation using survey data from 982 retail entrepreneurs across Thailand. Measurement reliability and validity were verified through CFA, while hypothesized structural relationships were tested using SEM. The findings validated both the robustness of the measurement model and the explanatory strength of the structural model, emphasizing the importance of DTN and SMU in driving SBP within the Thai retail sector.

4.1. Qualitative Results

The qualitative phase employed a three-round e-Delphi survey with 23 experts, with consensus validated using FCM clustering under a two-cluster specification. After computing individual cluster centroids, the procedure was adapted by aggregating them into a single “One Centroid” consensus value through a weighted averaging approach. Consensus was defined as a weighted centroid score ≥6.0 on a 7-point Likert scale.

As reported in Table 3, all 47 items achieved consensus, with every construct surpassing the One Centroid threshold of 6.000 on the 7-point Likert scale—highlighting the methodological rigor of the e-Delphi–FCM process. SMU displayed strong agreement scores (6.648–6.890), followed by DTN with similarly robust values (6.471–6.793). CNS recorded consistently high consensus levels (6.401–6.567), while SIN demonstrated a broader yet reliable range (6.402–6.803). CEX also showed strong validation (6.631–6.735), while ORE maintained stable outcomes (6.471–6.709). CAE achieved one of the widest but strongest ranges (6.510–6.677). Finally, SBP emerged as the peak construct, reaching the maximum One Centroid consensus value of 6.837 (6.558–6.837). Collectively, these results confirm that all constructs not only exceeded the required threshold but also demonstrated remarkable consistency. This validates the robustness of the measurement model and establishes rigorous groundwork for conducting CFA and SEM examinations.

Table 3.

Results of e-Delphi and FCM-based expert consensus analysis across observed variables (Source: Author).

4.2. Quantitative Results

The quantitative phase involved statistical validation of the proposed model using survey data collected from 982 Thai retail executives. CFA was first performed to assess construct reliability and validity, followed by SEM to evaluate the hypothesized associations among the core constructs. The detailed empirical results are presented below.

4.2.1. Descriptive Statistics

This study analyzed 982 valid survey responses collected from individuals employed across various segments of Thailand’s retail sector. Before analysis, all responses were screened for completeness and consistency. The demographic characteristics of the sample covered gender, age, education level, organizational position, years of experience, and retail type, ensuring diverse representation across the sector. As shown in Table 4, the gender distribution included 462 males (47.0%) and 520 females (53.0%). Regarding age, the largest group was 29–45 years (49.8%), followed by those aged 46–60 years (41.2%). Younger participants aged 18–28 accounted for 8.6%, while only 0.4% were above 61 years. This indicates a respondent pool dominated by working-age professionals, particularly from Generations Y and X.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of respondents’ demographic characteristics (Source: Author).

In terms of regional representation, 21.9% of respondents were located in the Bangkok metropolitan area, while the remainder were distributed across central (14.7%), northern (13.3%), southern (12.7%), eastern (16.6%), western (10.4%), and northeastern (10.4%) regions. This balanced geographic coverage demonstrates the inclusion of retailers from across Thailand. Education levels revealed that most respondents had at least a bachelor’s degree. Specifically, 55.2% held a master’s degree, 33.9% a bachelor’s degree, and 10.6% a doctoral degree, while only 0.3% reported qualifications below the bachelor’s level. This reflects a highly educated workforce among Thai retail managers and executives. Work experience showed that 34.9% had 6–10 years of experience, 24.4% had 11–15 years, 23.9% had 1–5 years, and 16.8% had over 15 years. Position levels were well distributed: 20.9% serving as department heads, 25.1% in middle management, 26.7% in upper management, and 27.3% as top executives, reflecting perspectives from multiple decision-making levels. Finally, various retail formats were represented by the respondents: department stores (17.8%), specialty stores (16.5%), supermarkets (15.9%), discount stores/hypermarkets (15.7%), community malls (13.7%), shopping centers (12.6%), and convenience stores (7.7%). This diversity underscores the comprehensiveness of the sample across modern retail sub-sectors in Thailand.

4.2.2. Measurement Model Assessment

The Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was initially performed on each construct as a prerequisite to testing, the measurement model [90]. This procedure confirmed that the observed indicators were consistently aligned with their respective latent constructs and theoretically coherent within the proposed framework. The analysis yielded strong empirical support, as all factor loadings exceeded the recommended 0.70 benchmark [108], and overall model fit indices meeting established standards.

As presented in Table 5, the CFA results indicated an excellent measurement model, with fit indices consistently surpassing accepted thresholds. Reliability and validity metrics further reinforced the robustness of the model: Composite Reliability (CR = 0.908–0.953) and Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.910–0.951) were both well above the 0.70 criterion, while Average Variance Extracted (AVE = 0.663–0.757) and R-Squared (R2 = 0.553–0.804) exceeded 0.50 [104]. The uniformly high factor loadings verified strong convergent validity across all constructs.

Table 5.

Construct reliability and validity and factor loading (Source: Author).

These results demonstrate a high level of measurement rigor and internal consistency, underscoring the robustness of the developed scale and its contextual relevance. Collectively, the validated measurement model provides a sound foundation for subsequent hypothesis testing and strengthens the study’s contribution to understanding how DTN and SMU jointly influence SBP.

Prior to testing the structural model, the measurement model was validated through Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to ensure the adequacy and reliability of the latent variables. Reliability and validity were assessed utilizing Composite Reliability (CR), Cronbach’s Alpha (α), and standardized factor loadings for all observed indicators. As summarized in Table 6, the results revealed strong model fit across all latent variables.

Table 6.

Goodness of fit of CFA test (Source: Author).

All goodness-of-fit Indicators met or surpassed the recommended thresholds (χ2/df < 3; AGFI, CFI, GFI, IFI, NFI, and TLI ≥ 0.90; RMSEA < 0.08; RMR < 0.05), confirming the robustness and stability of the measurement structure. Specifically: χ2/df values ranged from 0.392 to 2.690, while fit indices such as AGFI (0.976–0.998), CFI (0.996–1.000), GFI (0.989–1.000), IFI (0.996–1.000), NFI (0.993–1.000), and TLI (0.993–1.002) consistently exceeding the benchmark criteria. The RMSEA (0.000–0.042) and RMR (0.002–0.009) values remained well below acceptable limits, underscoring excellent model convergence. These results confirm that the CFA framework attained exceptional model adequacy and measurement validity, offering a solid empirical basis for subsequent SEM-based hypothesis testing.

4.2.3. Structural Model Assessment

The structural model was evaluated with Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) in statistical software to determine the importance of hypothesized paths and explained variance (R2). Correlations among constructs were below the 0.90 threshold, confirming the absence of multicollinearity among latent variables.

As illustrated in Figure 5, the rigor of the proposed conceptual framework was confirmed by the statistical robustness of all postulated paths. For direct effects, SMU exerted strong positive influences on both CNS (β = 0.895, p < 0.001) and SIN (β = 0.638, p < 0.001), underscoring its role in fostering inter-firm linkages and stimulating co-creative innovation. Similarly, DTN significantly enhanced CEX (β = 0.907, p < 0.001) and CAE (β = 0.260, p < 0.001), underscoring its contribution to digital agility and market responsiveness.

Figure 5.

Structural equation model illustrating hypothesis test results (Source: Author), with significance levels indicated as *** p < 0.001 and ** p < 0.01.

Although the direct effect of DTN on CAE is relatively modest (β = 0.260), this pattern reflects the structural logic of the model, wherein DTN exerts its influence primarily through Customer Experience (CEX)—the only downstream dynamic capability directly shaped by DTN. Consequently, the indirect pathway (DTN → CEX → CAE) absorbs a substantial portion of the total effect, naturally reducing the magnitude of the direct coefficient. This effect pattern is theoretically consistent with digital transformation research, where competitive gains typically emerge after digital capabilities have been fully assimilated, reconfigured, and aligned with strategic objectives.

Regarding the mediating mechanisms, CNS positively influenced SIN (β = 0.321, p < 0.001) and ORE (β = 0.148, p < 0.01), while SIN further contributed to ORE (β = 0.755, p < 0.001) and CAE (β = 0.305, p < 0.001). These findings underscore the roles of CNS and SIN as key transmission channels linking digital resources to adaptive capabilities that support strategic resilience.

In the downstream section of the model, CEX significantly predicted SBP (β = 0.136, p < 0.001), whereas ORE emerged as a central driver of both CAE (β = 0.403, p < 0.001) and SBP (β = 0.179, p < 0.001). Notably, CAE showed the most substantial direct impact on SBP (β = 0.669, p < 0.001), affirming its essential mediating function between upstream digital and relational capabilities and downstream sustainability outcomes.

Overall, the model accounted for substantial variance in the endogenous constructs (R2 = 0.802 for CNS, 0.877 for SIN, 0.823 for CEX, 0.791 for ORE, 0.858 for CAE, and 0.890 for SBP). These high explanatory powers provide compelling empirical evidence for the robustness of the structural model and validate the integration of DTN and SMU as critical enablers of sustainable performance in the retail industry.

These results empirically substantiate the integrated RBV–DCT framework proposed in this study. Specifically, digital resources (SMU and DTN) act as strategic assets that initiate dynamic capabilities (CNS, SIN, CEX, and ORE), which are subsequently consolidated through CAE to yield superior SBP.

These empirical patterns also reveal a hierarchical transformation mechanism whereby digital resources are sequentially converted into dynamic capabilities and strategic outcomes. SMU initiates relational learning through CNS and SIN, while DTN drives CEX and CAE via data-driven process reconfiguration. Together, these mechanisms illustrate how firms orchestrate digital resources into sustainable value through capability recombination and strategic alignment—addressing the causal chain that links social and technological inputs to long-term performance.

4.2.4. Model-Fit Indices

The structural model exhibited strong alignment with empirical data (Table 7). Although the chi-square statistic was significant (χ2 = 1780.551, df = 997), the normalized ratio (χ2/df = 1.786) remained well below the recommended threshold of 3.0 threshold, underscoring model adequacy. Incremental fit indices, including AGFI (0.921), CFI (0.984), GFI (0.930), IFI (0.984), NFI (0.964), and TLI (0.982), all surpassed the suggested cutoff of 0.9, substantiating the framework’s incremental validity. Absolute fit measures further reinforced the model’s robustness, with RMSEA (0.028) and RMR (0.029) residing within acceptable bounds. Collectively, these indices affirm the model’s reliability and appropriateness for subsequent hypothesis testing.

Table 7.

Model-fit test Results (Source: Author).

The proposed hypotheses were empirically examined using the SEM, with the significance level of each causal relationship evaluated. Table 8 presents the hypothesis testing outcomes, showing that all hypothesized relationships within the research model were supported at acceptable significance levels.

Table 8.

Consolidated Results of Hypothesis Verification (Source: Author).

4.2.5. Mediation Analysis

Bootstrap-based mediation analysis using 5000 resamples was conducted to examine the indirect effects of SMU and DTN on SBP through the proposed dynamic capabilities (Table 9). Confidence intervals at 95% were applied to determine the statistical significance and identify the mediation patterns across multi-stage capability pathways.

Table 9.

Specific indirect effects and mediation paths (Source: Author).

For SMU, the total indirect effect on SBP was significant (β = 0.561, 95% CI [0.514, 0.607], p < 0.001), confirming that SMU’s influence on sustainable performance primarily operates through the sequential activation of collaboration, innovation, resilience, and strategic advantage. Among the specific mediation chains, the strongest indirect effects were observed in SMU → SIN → ORE → CAE → SBP (β = 0.131, 95% CI [0.065, 0.195]) and SMU → SIN → CAE → SBP (β = 0.130, 95% CI [0.068, 0.192]), followed by SMU → SIN → ORE → SBP (β = 0.086, 95% CI [0.042, 0.130]). These pathways indicate that social-media-driven connectivity fosters SIN and ORE, which collectively reinforce CAE and long-term sustainability. The direct path from SMU to SBP remained non-significant, confirming a full mediation effect, consistent with the RBV–DCT logic that digital social resources must be transformed into dynamic capabilities to yield performance value.

Similarly, DTN exhibited a significant total indirect effect on SBP (β = 0.298, 95% CI [0.245, 0.350], p < 0.001), with the main mediation channels through CEX (β = 0.123, 95% CI [0.083, 0.164]) and CAE (β = 0.175, 95% CI [0.116, 0.232]). These results demonstrate that DTN enhances sustainability performance not through direct technological effects, but by enabling superior CEX and converting digital assets into strategic CAE. Once again, the non-significant direct effect supports a full mediation pattern, reinforcing that technology-driven initiatives create long-term value only when embedded within adaptive, customer-centric capability systems.

To further validate the robustness of the proposed framework, alternative structural models were compared against the full-mediation model. A direct-only model (excluding mediating constructs) and a partial-mediation model were tested. The proposed full-mediation model achieved superior fit indices (χ2/df = 1.786, CFI = 0.984, TLI = 0.982, RMSEA = 0.028), outperforming both alternatives. This result confirms that incorporating dynamic capabilities as mediating mechanisms significantly enhances the model’s explanatory power and theoretical consistency.

Among all mediating mechanisms, CAE exerted the strongest direct influence on SBP (β = 0.669, p < 0.001), followed by ORE, highlighting that while SIN and CEX enable responsiveness and agility, it is the strategic consolidation of these mechanisms through CAE that ultimately converts dynamic capabilities into enduring performance outcomes. In the Thai retail context, this multi-stage mediation structure reflects how firms in emerging markets transform fragmented digital practices into integrated capability systems—simultaneously leveraging SMU for relational engagement and DTN for process digitalization to build resilient ecosystems and sustain competitiveness amid rapid technological shifts.

Collectively, these results validate and extend the integrated RBV–DCT framework by uncovering a “digital resource orchestration” mechanism—where SMU and DTN jointly generate sustainability through a sequential cascade of collaboration, innovation, resilience, and strategic advantage that together underpin long-term SBP in the Thai retail industry.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions and Empirical Patterns

This study advances theoretical understanding by empirically validating an integrated framework linking Social Media Use (SMU) and Digital Transformation (DTN) to Sustainable Business Performance (SBP) through multiple mediating mechanisms. The findings demonstrate that SMU enhances Collaboration Networks (CNS) and Service Innovation (SIN), while DTN strengthens Customer Experience (CEX) and Competitive Advantage (CAE), forming dynamic capability pathways that reinforce sustainable performance outcomes. These outcomes are consistent with Piller et al. [109], Islam et al. [110], and Halale et al. [111], who assert that digital interaction and network connectivity accelerate organizational learning and innovation capacity in turbulent markets.

In particular, DTN further contributes to CEX and CAE, underscoring that technological transformation delivers enduring value when customer-centricity and organizational agility are embedded within digital systems. This finding aligns with Patil et al. [112] and Mohapatra et al. [113], who emphasize that responsive and personalized digital engagement translates technology investments into sustainable differentiation. The causal chain CEX → CAE → SBP highlights how service excellence and adaptive customer engagement secure competitiveness amid ongoing technological disruption.

Beyond customer-facing dynamics, the interplay among SIN, ORE, and CAE reveals a capability-building sequence in which innovation and resilience mutually reinforce organizational agility and strategic strength—an effect echoed by Garrido-Moreno et al. [12] and Asare-Kyire et al. [114]. This pattern substantiates the principles of Dynamic Capabilities Theory (DCT) by illustrating how firms reconfigure digital resources into ORE, CAE, and sustainable outcomes over time.

Building upon these empirical insights, the study advances from description to explanation by clarifying how RBV and DCT jointly operate within a unified causal logic. RBV defines DTN and SMU as strategic digital assets, while DCT elucidates how these assets are sensed, seized, and reconfigured into interconnected dynamic capabilities (CNS, SIN, CEX, ORE) that culminate in CAE and SBP. This process unfolds as a multistage causal mechanism—digital resources → dynamic capabilities → competitive advantage → sustainable performance—providing empirical support for the logic of resource mobilization and renewal.

Moreover, this causal mechanism is not universal but contextually contingent. Factors such as organizational culture, managerial digital literacy, and infrastructure maturity emerge as boundary conditions that moderate this process in the Thai retail context. Firms with strong digital leadership and data-driven culture are better able to translate DTN and SMU into SIN and ORE, whereas those with limited capabilities may face implementation gaps. Such variation demonstrates that dynamic capability formation is both resource-dependent and context-sensitive.

Taken together, these results position SMU and DTN as dual strategic levers driving SBP through interconnected pathways involving CNS, SIN, CEX, and ORE. This integrative logic reinforces the tenets of DCT while bridging them with RBV, offering a coherent explanation of how digital and social resources evolve into dynamic, sustainability-oriented capabilities.

Extending this reasoning, the study introduces a novel theoretical lens—Digital Resource Orchestration for Sustainable Competitiveness (DROSC)—which articulates how digital resources are mobilized, synchronized, and renewed through dynamic capabilities to produce enduring competitive and sustainability outcomes. Within this lens, DTN and SMU are conceptualized not as isolated technological tools but as strategic enablers of capability recombination. DROSC therefore advances existing digital transformation theories by clarifying how orchestrated, sequential capability-building processes generate sustainable value—distinct from static digital capability or IT-enabled capability models typically found in prior research.

Empirically, this integration refines and extends both RBV and DCT. The RBV is extended by demonstrating that digital assets such as SMU and DTN generate enduring value only when dynamically reconfigured through DCT mechanisms, consistent with Vinekar and Teng [115]. Simultaneously, the study refines DCT by revealing how the sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring processes transform static digital resources into interdependent capabilities—CNS, SIN, CEX, and ORE—that collectively sustain competitiveness and resilience. In doing so, the RBV–DCT integration broadens the theoretical boundary conditions of both perspectives and anchors them within the intertwined domains of digital transformation and sustainability in emerging-market retail environments.

Finally, this study contributes to sustainability scholarship by positioning SBP within the broader “triple-bottom-line” paradigm encompassing economic, social, and environmental value creation. The empirical results show that dynamic capabilities such as Service Innovation and Organizational Resilience improve operational and financial outcomes (economic pillar), strengthen stakeholder engagement and collaborative networks (social pillar), and promote resource efficiency and responsible digital operations (environmental pillar). By embedding these sustainability dimensions within the DROSC framework, the study demonstrates how orchestrated digital and social transformation processes support UN SDGs (SDG 9—Industry, Innovation & Infrastructure; SDG 12—Responsible Consumption & Production; SDG 13—Climate Action), thereby advancing the theoretical frontier linking digital transformation with sustainable development and responsible digital evolution.

5.2. Managerial and Practical Implications

While the theoretical results clarify how DTN and SMU function as foundational digital resources driving SBP, the practical implications translate these insights into actionable strategies for retail leaders and policymakers. Anchored in the integrated RBV–DCT framework, digital resources must be continuously mobilized through dynamic capabilities to generate CAE and support long-term sustainability. This aligns with Praveenraj et al. [87] and Mboungou (2024) [116], who stress that digital transformation should evolve from fragmented projects into an organization-wide strategic orientation.

Retail executives should therefore move beyond viewing DTN and SMU as isolated tools and embed them into the firm’s strategic core—spanning infrastructure, data analytics, and omnichannel engagement. Such integration transforms digital investments into dynamic capabilities that nurture SIN and ORE, which in turn enhance innovation capacity and adaptive resilience, as demonstrated by Migdadi [117] and Evenseth et al. [118].

Furthermore, aligning these capabilities with CNS enables firms to co-create value, accelerate innovation diffusion, and respond proactively to market turbulence, consistent with Tariq [119]. Collectively, these synergies fortify CAE and translate capability development into measurable and enduring performance gains.

Practically, the study proposes a three-tier strategic roadmap for retail organizations:

- Strengthen core digital levers (DTN and SMU) as the foundation for competitiveness and growth.

- Cultivate dynamic capabilities (SIN, ORE, CNS) to convert digital tools into innovation, agility, and resilience.

- Reframe success metrics from short-term efficiency toward long-term sustainability, aligning strategic intent with stakeholder engagement.

For policymakers, the findings highlight the importance of building an enabling digital ecosystem—through fiscal incentives, infrastructure, and regulatory frameworks—that empowers Thai retail firms to scale their digital and sustainable transformation. In Thailand, this requires synchronizing initiatives under the Thailand 4.0 policy, the Digital Economy Promotion Agency (DEPA), and the National E-Commerce Strategy to enhance interoperability, cybersecurity, and data-sharing standards across retail platforms. Government-led infrastructure programs such as 5G expansion, nationwide digital payment adoption, and regional SME digital upskilling are crucial for strengthening omnichannel competitiveness and sustainable logistics integration.

Moreover, collaborative partnerships among government agencies, private digital platforms, and academic institutions can catalyze innovation transfer and knowledge diffusion across the retail value chain, echoing Subrahmanyam [120] and Mokkapati & Goel [121]. For retail practitioners, context-specific actions should reflect the diversity of Thailand’s market formats—including department stores, community malls, supermarkets, convenience stores, and hybrid e-commerce channels—each requiring differentiated digital strategies tailored to customer behavior and infrastructure readiness.

Ultimately, these insights reposition Thai retail firms from passive technology adopters to active orchestrators of digital ecosystems. By leveraging DTN and SMU, organizations can transform technological progress into sustained competitive advantage, social value, and contributions to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—advancing Thailand’s trajectory toward a resilient, inclusive, and innovation-driven digital economy.

Collectively, these managerial and policy-oriented implications reinforce the integrated RBV–DCT framework by demonstrating how digital and social resources, when activated through dynamic capabilities, can be operationalized into measurable sustainability outcomes. This alignment between theoretical logic and managerial practice underscores the model’s practical validity, providing a blueprint for emerging-market firms to translate digital transformation into enduring strategic advantage and societal impact.

5.3. Methodological Contributions and Pathways for Refinement

This study advances methodological practice by integrating e-Delphi technique, FCM, and SEM into a unified dual-method framework. This integration bridges qualitative consensus building with quantitative validation, establishing a rigorous pathway from expert judgment to causal inference—an approach still relatively uncommon in management and sustainability research.

The e-Delphi process systematically gathered expert knowledge through multiple rounds of consensus-building, revealing relationships consistent with prior research by Moss et al. [99]. The FCM algorithm, which is based on fuzzy logic, translated these expert evaluations into graded membership levels, offering a nuanced interpretation beyond simple binary outcomes of “agree–disagree,” similar to earlier work by Agarwal [122]. This fuzzy-based approach enriched construct reliability and overcame one long-standing limitation of traditional Delphi studies—the loss of interpretive depth during convergence in accordance with the previous studies of Roldán López de Hierro et al. [92].

Subsequently, both CFA and SEM validated that the conceptual clarity derived from the qualitative phase remained statistically sound throughout the quantitative stage, aligning with prior research by Lotfi and Sodhi [123]. This two-stage linkage between expert-driven conceptualization and empirical validation enhances methodological rigor and internal validity, offering a replicable model for complex constructs in digital transformation and sustainability research, as demonstrated in the research of Nitlarp and Kiattisin [124].

5.4. Future Research Directions and Global Relevance

Building upon the validated dual-method framework, future research can expand these insights by exploring how DTN and SMU jointly foster SBP through the dynamic interactions among CNS, SIN, CEX, ORE, and CAE across different contexts. Given that this study is grounded exclusively in the Thai retail sector, future research should explicitly validate the model in cross-national and cross-industry settings to enhance its generalizability. Cross-national and cross-sectoral studies could further reveal how variations in regulatory sophistication, digital readiness, and cultural orientation shape these capability linkages—particularly within emerging regions such as Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Africa—where digital ecosystems and institutional infrastructures are still evolving. Such inquiries would align with the findings of Algazo et al. [125] and Michelotto & Jóia [126], who emphasize the contextual sensitivity of digital-sustainability pathways.

Beyond contextual generalization, future scholars may advance the methodological frontier by refining the integrated e-Delphi–FCM–SEM framework. Hybrid extensions—such as fuzzy–rough or machine-learning–driven consensus models, swarm intelligence, or adaptive weighting systems—could enhance computational precision and cross-sector robustness. These innovations would not only elevate the accuracy of consensus-driven modeling but also reinforce the credibility of fuzzy-based analytics in unpacking multidimensional constructs related to sustainability, innovation, and organizational transformation.

Looking ahead, longitudinal and dynamic-panel studies are encouraged to capture how these interlinked capabilities evolve over time—transforming DTN and SMU from operational enablers into strategic architectures of sustainable competitiveness. Additionally, future research could incorporate cross-cultural comparison frameworks to investigate how national culture, institutional support, and digital maturity influence the strength and direction of capability linkages across markets. Introducing moderators such as organizational culture, leadership orientation, or digital maturity would further clarify boundary conditions under which the proposed DROSC framework operates across varying environments. Such temporal and comparative analyses would illuminate how organizations transition from passive technology adopters to proactive orchestrators of digital ecosystems, thereby enriching global understanding of how digital and social technologies converge to advance the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the next generation of resilient business models.

6. Conclusions

This study offers a comprehensive and empirically validated framework that integrates the RBV and DCT to explain how SMU and DTN jointly enhance SBP in the Thai retail sector. By combining the e-Delphi, FCM, and SEM techniques, the research demonstrates a robust methodological pathway that connects digital resources to dynamic capabilities—namely CNS, SIN, CEX, and ORE—which in turn consolidate into CAE and long-term sustainability outcomes [127].