Abstract

To address carbon cost pressures from the CBAM and fluctuation in China’s domestic carbon-pricing mechanism, it is crucial to design a carbon quota allocation scheme for China’s steel industry that balances total quantity control and structural optimization. This study comprehensively considers the industry’s LCA and regional heterogeneity, introduces indicators related to “energy transformation contribution”, and employs the maximum deviation method and harmony allocation model to calculate and evaluate provincial quotas and their performance. Results show that: (1) Under the national total quantity control strategy, China’s steel industry carbon quota will be reduced to 1770 Mt by 2030; (2) Calculated via the maximum deviation method, the energy transformation contribution index accounts for 18.95% of the total contribution of all factors, while the LCA index accounts for 46.61%; (3) The maximum inter-provincial difference in carbon quotas reaches 175 Mt, reflecting significant heterogeneity in ecological carrying capacity, resource-allocation efficiency, and emission-reduction potential across regions. This study provides a scientific basis for optimizing China’s unified carbon-market mechanism and guiding the steel industry’s energy transition, and offers a reference for developing countries to address international carbon barriers through regionally differentiated strategies.

1. Introduction

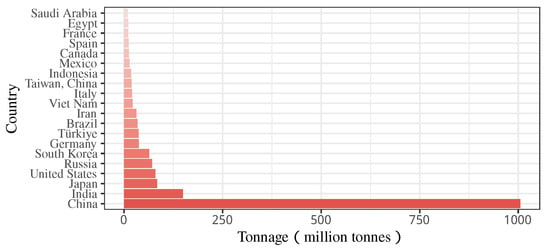

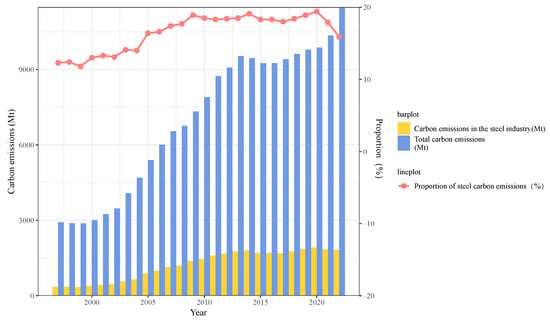

In the context of globalization, reducing greenhouse gas emissions has become a global consensus [1,2,3]. As the world’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide, China explicitly announced its goals of “reaching peak carbon emissions by 2030 and achieving carbon neutrality by 2060” [4] at the 75th session of the United Nations General Assembly. The 15th Five-Year Energy Development Plan [5] further positions energy transition as the core pathway to achieving the dual carbon goals, emphasizing the need to increase the share of non-fossil energy consumption and drive high-carbon industries such as steel from “energy structure adjustment” to “full-chain low-carbon transformation”. As a pillar industry of the national economy, China’s steel sector has maintained its position as the world’s largest producer for over 20 consecutive years, accounting for approximately 53.33% of global output (World Steel Association). Carbon emissions from the steel industry constitute about 15% of China’s total emissions, with energy consumption-related emissions exceeding 80% of this share (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). Therefore, the depth of the energy transition directly determines the pace and quality of achieving the dual carbon goals, and the transformation process of the steel industry has become a key benchmark for optimizing the energy structure of China’s high-carbon industries [6,7].

Figure 1.

The output of major steel-producing countries in 2024.

Figure 2.

Trends in China’s total carbon emissions and carbon emissions from the steel industry from 1997 to 2022.

The national unified carbon market serves as the core mechanism for achieving the dual carbon goals [6]. Its incentive effectiveness in guiding corporate emissions reductions through stable carbon price signals directly impacts the progress of the energy transition. However, carbon prices have recently remained persistently low and exhibited significant volatility. Data from the Shanghai Energy and Environment Exchange shows that the national carbon price stood at 101.10 CNY per ton in October 2024, plummeting to 58.8 CNY per ton in the same period of 2025. This represents only about one-tenth of international carbon prices (such as the EU’s 80–90 EUR per ton). Consequently, the revenue from emissions reductions struggles to cover the costs of transition, directly weakening companies’ willingness to invest in voluntary emissions reduction efforts. This issue has become more pressing under international policy pressure. The EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) will impose carbon tariffs on six high-carbon industries, including steel, starting in 2026. Steel products exported to the EU will be required to pay additional fees based on EU carbon pricing. If the quota system is not optimized simultaneously, the implementation of CBAM could increase the export costs of Chinese steel by 1.7% to 9.6% [8,9]. Enterprises will face substantial additional costs, directly undermining their competitiveness in exports to Europe [10]. The convergence of internal and external challenges underscores the urgency and necessity of restoring the carbon price signal function by optimizing the carbon quota allocation mechanism, thereby balancing domestic emission-reduction targets with international competitiveness. This trend is consistent with the international reform. The reform of the EU ETS (emissions trading system) shows that the free quota is being phased out (2026–2035) and replaced by the CBAM.

In August 2025, the general office of the State Council issued guidance [11] that carbon quota management should shift from intensity control to total amount control, and optimize the carbon price mechanism by reducing the supply of quotas. The policy emphasizes that the quota allocation needs to consider industrial and regional differences, to achieve total amount control and precise allocation, and stimulate the energy transformation of the steel industry.

The scientific allocation of carbon quotas constitutes the core element of the effective operation of the carbon market, which directly determines the compliance cost and market competitiveness of enterprises’ carbon trading [12]. As for the quota allocation method of the iron and steel industry, China’s pilot carbon market generally adopts the historical method derived from the grandfather system [13] (see Appendix A Table A1), but it is easy to solidify the pattern of “high emissions in resource-based regions”, and it is difficult to reflect the heterogeneity of provincial energy structure, technological potential, etc. [14]. With its multi-dimensional evaluation framework and flexible adaptability, the index method has become a scheme that takes into account multiple indicators such as production efficiency, technical level, and environmental benefits [9,15,16,17]. In the process of research progress, the research on the LCA of the steel industry has gradually attracted the attention of scholars [18,19]. The research results of Baji [20] show that the energy consumption of recycled steel can be reduced by 70% compared with the original steel. The establishment of a quota system that combines the LCA and regional differences is essential to balance domestic emission-reduction responsibilities and international carbon costs [21].

At present, there are four main defects in the research on carbon quotas for the steel industry: (1) The academia generally pays attention to the allocation principle of carbon quotas, but ignores the in-depth discussion on the total quota control mechanism. (2) The research perspective mainly focuses on the emission intensity at the production end, and less on the integration from the perspective of the LCA. (3) The lack of a regional coordination mechanism has led to the balance between the transformation advantages of developed regions and the development needs of less developed regions not being properly handled, especially in the consideration of key factors such as energy transformation potential and technology emission-reduction potential. (4) The lag of parameter setting is a common problem in current research. In many studies, the 6% GDP growth rate is usually adopted as the assumption [22,23]. However, the real GDP growth rate from 2021 to 2024 is only 5.5%. If the assumption of 6% is continued, it will inevitably lead to the deviation of the total quota forecast. The inconsistency between the policy requirements and the actual operation of the industry highlights the urgent need to reconstruct the quota allocation mechanism.

Existing research has yet to develop a systematic approach that addresses both domestic and international demands. This paper overcomes these limitations through three innovative approaches: (1) Incorporating the quota gap rate as a core parameter into the total quota calculation formula, coordinating policy adjustments to quota supply, enhancing the stability and effectiveness of carbon price signals, and providing quantitative support for total control targets. (2) Differentiated dynamic adjustments to provincial carbon quotas. This mechanism incentivizes regional energy structure optimization and advances the low-carbon transition process. (3) Incorporate the steel industry’s full life-cycle indicator system into the quota allocation framework. By identifying regional differences in energy endowments, technological capabilities, and industrial structures, achieve precise alignment between quota distribution and actual regional development needs, thereby enhancing the scientific rigor and adaptability of the allocation plan.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to construct a carbon quota allocation system that integrates “energy transition contribution” and dynamic total quantity regulation based on the LCA and regional heterogeneity characteristics of China’s steel industry. By optimizing the model with multiple indicators and implementing a harmonious allocation mechanism, the scientific calculation and fair adjustment of quotas can be achieved. Ultimately, it provides theoretical support and policy paths for improving the national unified carbon-market quota allocation mechanism and promoting the steel industry’s transition from “passive emission reduction” to “active energy transformation”.

2. Research Methods

This chapter systematically expounds the methodology from three dimensions: the calculation of the total quota, the construction of the distribution model, and the redistribution from the perspective of harmony. Provide systematic methodological support for the initial carbon quota allocation of the provincial steel industry.

2.1. Total Quota Calculation

This paper establishes a national carbon-emission allowance estimation model for the period 2023–2030. It centers on the core constraint of China’s national target to reduce carbon-emission intensity by 60–65% compared to 2005 levels by 2030 [24]. The model integrates actual carbon-emission intensity data from 2023 with projected GDP growth rates.

Given the relatively stable proportion of carbon emissions from the steel industry within the national total, the initial total quota for the steel sector from 2023 to 2030 was calculated proportionally based on Tian’s [15] research. To adhere to the principle of “overall industry breakeven with a slight deficit” [25], this paper dynamically adjusts the initial total allocation for the steel industry by setting a quota deficit ratio, ultimately determining the 2030 carbon-emission target for the steel sector.

The calculation process is as follows:

Among them:

where represents the total carbon emissions of China in year t; and denote the GDP and carbon-emission intensity in 2023; is the average annual growth rate of GDP, taking 5% [26,27]; q is the average annual decline rate of carbon-emission intensity; is the carbon-emission ratio coefficient of the steel industry, which is taken as 15% [17,23]; is the carbon-emission reduction target, taking 65%; represents the quota gap, This paper sets it at 1.6% [28]).

2.2. China’s Provincial Steel Industry Carbon Allowance Allocation Plan

Against the background of expanding the carbon market, the steel industry, as the main source of carbon emissions, plays a crucial role in planning its emission-reduction path for achieving the dual carbon goals. This article focuses on the initial carbon quota allocation problem in the provincial steel industry, integrating an LCA perspective and regional heterogeneity characteristics to construct a four-dimensional carbon quota allocation system that balances fairness, efficiency, feasibility, and sustainable development.

2.2.1. Quota Allocation Indicator System

In the context of cultivating new quality productivity, the construction of the carbon quota allocation system in the steel industry needs to be based on the industry’s actual situation and energy transformation needs, and explore scientific allocation ideas. To construct a scientifically reasonable and effective carbon-emission allocation index system for the system, this article selects 18 indicators based on existing research results, and conducts subsequent research guided by the four principles of equity, efficiency, feasibility, and sustainability (Table 1).

The principle of fairness is the core of achieving balanced allocation of resources under the framework of carbon quota allocation [29], aimed at ensuring the fairness of carbon-emission rights distribution among all parties, specifically reflected through indicators such as the number of labor force, environmental resource endowment, industry energy structure, and industry carbon emissions.

The principle of efficiency focuses on promoting low-carbon and efficient transformation. The core indicators are as follows: industry carbon productivity, carbon-emission intensity, the comprehensive energy consumption per ton of steel, and the energy consumption intensity.

Table 1.

China’s steel industry carbon quota allocation indicator system.

Table 1.

China’s steel industry carbon quota allocation indicator system.

| Primary Principle | Secondary Principle | Indicator | Measurement Description | Unit | Nature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equity | Equity in Survival | Population [30,31] | Regional resident population | 10,000 people | + |

| Area [32] | Provincial area | square kilometers | + | ||

| Equity in Development | Environmental Resource Endowment [33] | Regional ecosystem service value | billion CNY | + | |

| Industry Cumulative Carbon Emissions [34] | Annual carbon emissions of the steel industry | 10,000 tons | − | ||

| Efficiency | Resource-Allocation Efficiency | Industry Productivity [35] | GDP/Carbon emissions | CNY/ton | + |

| Carbon-Emission Intensity [36] | Total carbon emissions/GDP | ton CO2/ton product | − | ||

| Emission Reduction Space Utilization Efficiency | Carbon Emission per Ton of Steel [37] | Carbon emissions from producing per unit of steel | ton CO2 | − | |

| Comprehensive Energy Consumption per Ton of Steel [37] | Energy consumption per unit product | ton standard coal | − | ||

| Energy Consumption Intensity [38] | Energy consumption/GDP | ton standard coal/10,000 CNY | + | ||

| Feasibility | Economic and Social Feasibility | Industry Fixed Asset Investment [29] | Investment cost for creating and purchasing fixed assets | billion CNY | + |

| Industrial Added Value [39] | Output value of the industrial sector per unit time | billion CNY | + | ||

| Proportion of Tertiary Industry [34] | Tertiary industry output/Regional GDP | % | − | ||

| Urbanization Level [40] | Urban population/Total population | % | − | ||

| Sustainability | Ecological Sustainability | Green Coverage Rate [17] | Green area/Total land area | % | + |

| Energy Transition | Green Steel Production Level [41] | Electric arc furnace production/Total production | % | + | |

| Scrap Steel Recycling [41] | Scrap steel utilization amount | 10,000 tons | + | ||

| Industry Energy Structure [19] | Coal consumption/Total energy consumption | % | − | ||

| Pollution Control Investment [23] | Industrial pollution control investment amount | 10,000 CNY | + |

The feasibility principle focuses on the practical operability of the indicator system, which is embodied in three indicators: industry fixed assets investment, industrial added value, and pollution control investment.

The principle of sustainability emphasizes the regional spatiotemporal coordination between ecological protection and economic and social development, focusing on long-term carbon-emission balance and ecological stability, achieved through indicators such as green coverage, green steel-making level, scrap steel recycling, and urbanization level.

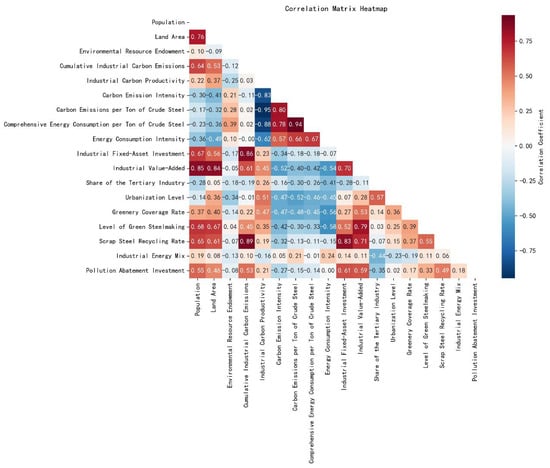

An in-depth study of the quota allocation indicator system was conducted through correlation analysis. The results showed that the proportion of indicators with a correlation coefficient less than 0.7 exceeded 90%, indicating the lack of significant correlation between indicators. In addition, according to the statistical results of factor analysis, the total variance interpretation rate of the presidential index system reached 72.91%. If the indicators corresponding to the four principles of fairness, efficiency, feasibility, and sustainability are excluded, the total variance interpretation rate will be reduced by 8.41%, 5.85%, 6.39%, and 7.96%, respectively. The statistical results confirm that these four principles are interdependent and synergetic, and together constitute an organic whole of the carbon-emission rights allocation system.

The four principles support and work together to form an organic whole of the carbon-emission rights allocation system: the principle of fairness is the foundation, ensuring fair distribution and balancing development differences; The principle of efficiency provides impetus, laying the economic and technological foundation for fair distribution by improving carbon emissions and economic output efficiency; The principle of feasibility ensures implementation, combined with actual economic strength and development stage, avoiding detachment from reality; The principle of sustainability provides direction, focusing on long-term ecological balance and low-carbon transformation, leading the system towards the goal of carbon neutrality. The specific indicators under each principle will transform abstract logic into a quantifiable basis, jointly constructing a scientific and reasonable allocation system.

2.2.2. Indicator Weight and Carbon Quota Calculation

Due to differences in the statistical caliber and dimensions of indicators, which may interfere with the comprehensive evaluation, it is necessary to eliminate dimensional interference through nondimensionalization. This article uses the extreme value method to standardize the data, ensuring a scientific and reliable analysis in the future. The positive indicators (the larger the value, the better) and negative indicators (the smaller the value, the better) are standardized using differential standardization formulas.

In the formula, is the standardized result of the jth indicator in year t, and is the value of the jth indicator in year t; min and max are the minimum and maximum values of the tth indicator, respectively.

In the multi-index evaluation method, the determination of index weight becomes the key link in the application of the method because of the wide variety and large number of indicators involved. The determination methods of weight mainly include the entropy weight method, the maximum deviation method, the equal weight method, etc. According to the research results of Li [42], Linghu [23], and other scholars, this study uses the maximum deviation method to calculate the index weight. The formula is [16]:

In the formula, is the total deviation of the jth indicator; is the normalized value of region i on the ith indicator; is the deviation of the jth indicator. When the total deviation reaches its maximum, the corresponding weighted vector W is the optimal weight vector.

By constructing a Lagrange function to solve the above optimization problem, the analytical solution of the index weight is obtained as follows:

2.2.3. Carbon Quota Space Balance

By comparing and analyzing the initial quota results of the steel industry in 2030 with the actual emissions in the benchmark year (2023), a quantitative assessment model of carbon-emission space is constructed:

where is the carbon-emission quota value of the steel industry in l province from 2016 to 2030; is the carbon-emission space in l provincial from 2016 to 2030; is the actual carbon emissions of the steel industry in the province l in the base year (2023).

2.3. Redistribution of Carbon-Emission Rights from the Perspective of Harmonious Distribution

In the field of carbon-emission quota allocation research, harmonious discriminant analysis is based on the theory of harmony. Its core concept is to follow the basic principles of respecting the development status quo, highlighting distribution fairness, optimizing overall efficiency, and strengthening dynamic regulation. It is committed to achieving the inherent rationality of carbon-emission quota allocation and coordinated sustainable development between regions [43]. To achieve this goal, the academic community has constructed a systematic and harmonious discrimination mechanism, which achieves scientific evaluation and dynamic tuning of allocation schemes through bidirectional discrimination dimensions and reverse optimization paths. Harmony discrimination includes two aspects: directional discrimination and degree discrimination. The former focuses on verifying whether the relative size relationship of quota allocation between regions complies with the principles of fairness and efficiency priority; The latter focuses on quantitatively analyzing whether the specific magnitude of distribution differences between regions is within the optimal range.

Through the synergistic effect of the above discrimination mechanisms, harmonious discriminant analysis can effectively identify potential conflict points in the allocation plan, and rely on the reverse tracking model to iteratively adjust key parameters, ultimately achieving the harmonious allocation of carbon-emission rights under the four-dimensional goals of “fairness, efficiency, feasibility, and sustainability”.

According to the correlation analysis of the above indicators, the calculation results (see Appendix A Table A2) show that the correlation coefficient between the number of permanent residents and the regional GDP is less than 0.7, except that the correlation coefficient between the number of permanent residents and the regional GDP is 0.78. However, since the number of permanent residents and the Gross Regional Product represent the two core principles of equity and efficiency, respectively, both are retained. The factor analysis of the harmony discrimination index reveals that the overall variance interpretation rate is 68.11%. If the corresponding indicators of fairness, efficiency, regulation, and status quo are eliminated in turn, the variance interpretation rate will be reduced by 6.96%, 11.65%, 7.27%, and 11.42%, respectively, which shows that the four selected indicators are irreplaceable and complementary to each other in the harmony discrimination system.

2.4. Select Harmonious Discrimination Indicators

When conducting harmonious discrimination, it is necessary to select scientifically reasonable discrimination indicators to comprehensively reflect the supply–demand balance of carbon-emission rights and economic and social development goals in each province. At the same time, to ensure the continuity of economic and social development in various regions, it is necessary to consider the historical carbon emissions of each region and avoid adverse effects on regional development caused by drastic adjustments in distribution plans [44].

Specifically, the selection of discrimination indicators should consider the following aspects: first, the principle of fairness. In order to reflect the fairness of carbon-emission rights allocation, it is necessary to comprehensively consider factors such as regional population and land area. Based on the principles of per capita emissions and land area, carbon-emission rights can be allocated more reasonably to ensure the basic rights and interests of each region in terms of carbon emissions. The second principle is efficiency, and the effective utilization of carbon-emission rights is closely related to economic benefits. Regional Gross Domestic Product (GDP) can indirectly reflect the carbon-emission demand of each region. Therefore, using GDP as one of the discriminant indicators can help evaluate the economic rationality of carbon-emission rights allocation. The third principle is regulatory, and the investment in environmental pollution control reflects the efforts and investments made by various regions in environmental protection. Incorporating this indicator into the discrimination system can better evaluate the contribution of various regions in carbon reduction and provide appropriate incentives when allocating carbon-emission rights. The fourth principle is the current situation, and historical carbon emissions are an important reflection of the current carbon emissions situation in various regions. Respecting historical carbon emissions can help maintain the continuity of regional development and improve the acceptability of distribution plans. Therefore, the number of permanent residents, regional gross domestic product, investment in environmental pollution control, and historical carbon emissions were selected as the discrimination indicators, as shown in Table 2, and the data were sourced from the China Economic Net statistical database.

Table 2.

Harmonious discrimination index system.

2.5. Discriminant Method

2.5.1. Directional Discrimination

Select the indicator values for harmony discrimination, and use the entropy method to calculate the weight of each indicator to characterize its relative importance. For any regional pair in the initial allocation scheme of carbon emission rights , their corresponding allocated carbon-emission rights are . If , then construct the index set:

In the formula, and are the thresholds for directional discrimination. If all ‘region pairs’ are determined by directional discrimination, then it is assumed that the initial allocation plan is determined by directional discrimination; on the contrary, if there are regions that have not passed directional discrimination, it is determined that the initial allocation plan is not coordinated and needs to be adjusted.

In the formula, is the value of the harmony discrimination indicator i for province . Construct the relative harmony indices and as follows:

where represent the weight of indicator i. The directional discrimination is given by:

2.5.2. Degree Discrimination

Construct a degree discrimination criterion based on comprehensive indicators, as shown in the following equation:

In the formulation, S represents the sum of harmony discrimination indicators; is the weighted composite index coefficient; and represent the upper and lower bound coefficients determined based on provincial characteristics, satisfying and . If all regional pairs pass both the directional discrimination and the degree discrimination, then the initial allocation scheme is considered to have passed the harmony discrimination. Otherwise, the initial allocation scheme is deemed inconsistent and requires adjustment. : represents the value of the i harmony index in the k province. This indicator corresponds to the i indicator value of the l province. The two indicators are used in Formulas (8) to (13) to compare the performance of different provinces in each indicator.

2.6. Reverse Tracing Adjustment of Initial Allocation of Carbon-Emission Rights

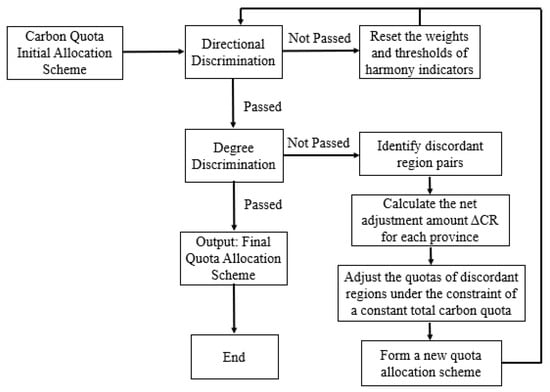

When the initial allocation plan is not coordinated, an uncoordinated area will be observed, i.e., the number of allocated carbon-emission allowances is too much or too little, and the corresponding provinces will be called “regions with excessive carbon-emission allowances” and “regions with insufficient carbon-emission allowances”, respectively. In this regard, this article adopts the reverse tracking adjustment method to find disharmonious areas for optimizing and adjusting carbon-emission quotas. See Figure 3 for the specific process.

Figure 3.

Reverse tracking adjustment process for carbon allowance.

2.6.1. Identify Disharmonious Areas

Firstly, directional discrimination has not been passed. If the initial allocation plan does not pass directional discrimination, it indicates the need to redetermine the weights and thresholds of the harmony discrimination indicators and then reevaluate the harmony discrimination of the initial allocation plan.

Secondly, through directional discrimination, it did not pass degree discrimination. If the initial allocation plan does not pass the degree discrimination based on comprehensive indicators, then, to reverse track which provinces have been allocated too much or too little, pairwise degree discrimination needs to be performed on all provinces. The net adjustment of carbon emissions in province is the synthesis of the discrimination results between that province and other provinces.

Assume that province undergoes rounds of degree discrimination with every other province (where ). Each discrimination yields an amount of carbon-emission rights that should be allocated to province , expressed as:

In the formula, represents the amount of carbon-emission rights that should be adjusted for province relative to province .

2.6.2. Reverse Tracking of Carbon-Emission Allowance Allocation

If the initial allocation scheme fails the degree of discrimination based on comprehensive indicators, it means that the carbon-emission allowance allocation ratio of the regional pair exceeds the upper limit or fails to meet the lower limit. Therefore, the amount of carbon-emission rights that province needs to adjust relative to province is expressed as:

Among them, the carbon-emission rights can be further defined as:

Since the total amount of carbon-emission allowances is fixed, the sum of total adjustments across all provinces should be zero.

3. Initial Allocation Results of Carbon Quota

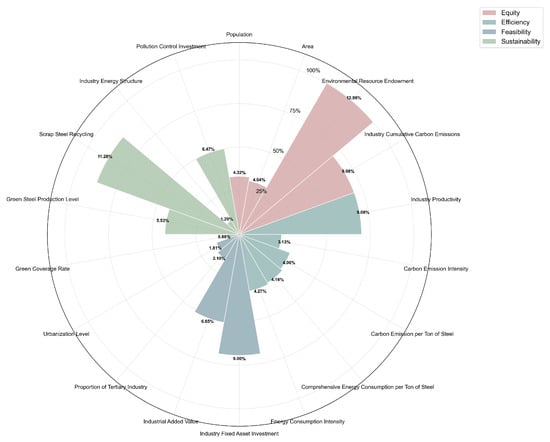

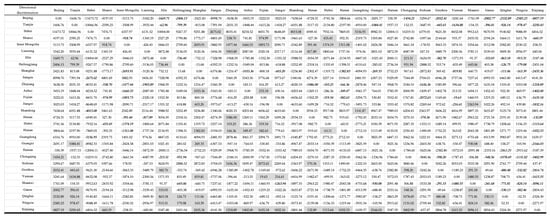

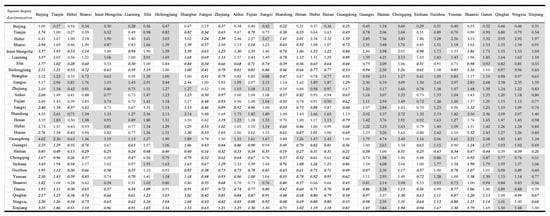

After calculation, the total carbon quota for the national steel industry in 2030 is 1.796 billion tons, and the weights of each indicator are shown in Figure 4. The initial carbon-emission quota weights for each province in China are shown in Table 3. Due to data availability constraints, the sample was selected from 30 provincial-level regions in mainland China (excluding Tibet). Data for national and provincial indicators are from China Steel Industry Yearbook, China National Bureau of Statistics (China NBS), provincial statistical bureaus, and Chinese Research Data Services Platform (CNRDs http://www.efindata.com). Carbon emissions and energy consumption data for the iron and steel industry are derived from the Carbon-Emission Accounts and Datasets (CEADs https://www.ceads.net.cn/). 2030 input-output indicator data are estimated based on the average annual growth rate of each indicator from 2017 to 2021. The specific data explanation and indicator selection logic are detailed in the following text.

Figure 4.

Indicator weights of distribution.

Table 3.

Initial carbon allowance allocation results and carbon-emission space for provincial iron and steel sectors.

After calculation by Equations (1) and (2), the total carbon quota for the national steel industry in 2030 is 1.77 billion tons. Analysis shows that the principle of fairness (30.42%) has the highest weight, followed by the principles of sustainability (25.36%), efficiency (24.65%), and feasibility (19.57%), collectively constituting the core considerations for carbon quota allocation(see Figure 4). It is worth noting that the total weight of characteristic indicators in the steel industry accounts for 46.61%, and the weight of energy transformation-related indicators accounts for 18.95%, significantly higher than general economic and social indicators, reflecting the carbon governance and energy transformation orientation of the LCA of the steel industry.

According to Table 3 data, there are certain regional differences in carbon-emission quotas among different provinces, and the proportion and amount of quotas show different distribution characteristics. Among them, Hebei Province has the highest quota ratio, at 8.40%; The quota ratio in Shandong Province is 5.46%; The quota ratio in Henan Province is 3.92%; The quota ratio in Jiangsu Province is 6.33%. In contrast, the quota ratios in provinces such as Beijing, at 0.74%, and Hainan, at 0.93%, are relatively low.

In order to deeply analyze the initial allocation of carbon-emission rights, this article divides the initial spatial balance of carbon-emission rights into six categories based on the equal interval classification standard: sufficient surplus, moderate surplus, slight surplus, slight deficit, moderate deficit, and severe deficit.

One is a severely deficit area, with only Hebei Province having an initial allocation of 138.86 million tons of carbon-emission rights and an initial spatial balance of −237.45 million tons, showing a significant and severe deficit state. These data indicate that under the current carbon-emission allocation framework, the actual carbon-emission scale in Hebei Province has significantly exceeded the initial allocation quota, facing extremely severe carbon-emission reduction pressure and the need for large-scale carbon emission regulation.

The second is a slightly deficit area, covering six provinces and cities, including Tianjin, Shanxi, Liaoning, Jiangsu, Anhui, and Shandong. The initial spatial balance of carbon-emission rights for these provinces in 2030 is in deficit, but the degree of deficit is relatively mild. This indicates that there is a certain gap between the carbon-emission level of such provinces and the initial allocation quota.

The third is a slightly surplus area, covering six provinces and cities, including Jilin, Jiangxi, Henan, Hubei, Yunnan, and Gansu. The initial spatial balance of carbon-emission rights in these regions in 2030 is in a surplus state, and the degree of surplus is relatively mild. This indicates that there is a certain margin in the carbon emissions level of such provinces compared to the initial allocation quota, and the overall performance is good under the current allocation framework.

The fourth is the moderate surplus area, including 13 provinces and cities such as Beijing, Heilongjiang, Shanghai, Fujian, and Hunan, whose initial spatial balance of carbon-emission rights is at a moderate surplus level. The initial spatial balance of the above-mentioned provinces is significantly higher than that of the slightly surplus area, indicating that there is a certain surplus in the initial allocation of carbon-emission quotas relative to actual demand.

The fifth is the region with sufficient surplus, including Inner Mongolia, Zhejiang, Guangdong, Qinghai, and Xinjiang, whose initial spatial balance of carbon-emission rights is at a relatively high level of surplus. The initial allocation of carbon-emission rights in these provinces has a significant surplus relative to actual demand, providing important support for the cross-regional allocation and optimization of carbon resources.

It can be seen that there are significant regional differences in the initial allocation plan of carbon-emission rights in various provinces of China, which deviates greatly from the ideal and reasonable state. The problem of uneven development between regions is prominent, and this will have a negative impact on the overall low-carbon transformation process of the basin in the long run. Therefore, in order to develop a fair and efficient allocation plan that ensures the achievement of the overall low-carbon development goals in the region while also considering the sustainable development needs of each province, it is urgent to establish a scientific and systematic carbon-emission rights allocation mechanism.

3.1. Harmonious Discriminant Analysis of Initial Allocation Scheme

3.1.1. Directional Discrimination

Based on the results of the entropy method, the weights for the harmony discrimination indicators were determined as follows: urban manufacturing employment () is 0.30, gross regional product () is 0.19, industrial pollution control investment () is 0.21, and historical cumulative carbon emissions of the sector () is 0.30. The thresholds and were set to 0.4 and 1.0, respectively. The directional discrimination of the initial allocation scheme was then performed using the formula (Table 4). As shown in Table 4, there is directional disharmony among provinces in China. Among them, bold and italicized cells represent regions that have not exceeded the relative harmony index , i.e., regions with excessive carbon-emission allocation have significantly higher weights for the harmony index compared to regions with insufficient carbon-emission allocation. For example, if the difference in allocation between Hebei Province and Henan Province is negative, it indicates that Henan Province has significantly more carbon-emission rights allocation than Hebei Province. However, Henan Province has at most two harmony indicators that are greater than Hebei Province, and the relative harmony indicator value is greater than 0.4, and is less than 1. The gray background cells represent regions that do not exceed the sum of two relative harmony indicators and , meaning that the weight of the harmony indicator in areas with excessive carbon-emission allocation is significantly greater than that in areas with insufficient carbon-emission allocation. For example, if the difference in allocation between Shanghai and Sichuan Province is positive, it indicates that Shanghai has significantly more carbon-emission allocation than Sichuan Province, but Shanghai has at most one harmony indicator that is greater than Sichuan Province, and the relative harmony indicator value is less than 0.4 and is less than 1.

Table 4.

Final allocation plan for provincial carbon-emission rights in China’s steel industry by 2030.

It can be observed that 29 provinces and cities, except for Shandong Province, have significant size directional relationships compared to other provinces (Figure 5). Among them, there is directional disharmony between Sichuan Province and 14 provinces, directional disharmony between Xinjiang Province and 12 provinces, and directional disharmony between Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, Hubei Province, Shaanxi Province, and 11 provinces. The allocation of carbon-emission rights in Shandong Province is relatively reasonable in terms of size and direction.

Figure 5.

Results of directional discrimination.

3.1.2. Degree Discrimination

The closer the lower bound coefficient and the upper bound coefficient for the degree discrimination based on comprehensive indicators are to 1, the higher the degree of matching between the carbon-emission allowance allocation ratio and the composite index. Therefore, to further analyze the results and adjust the initial allocation scheme, this paper sets the following scenarios based on different values of and . Each increase of 0.25 in and is considered to be one level of increase in matching degree, with the case where both are closest to 1 set as the highest matching degree.

- Scenario 1: Very Low Matching Degree—,

- Scenario 2: Low Matching Degree—,

- Scenario 3: Medium Matching Degree—,

- Scenario 4: High Matching Degree—,

Considering that it may be difficult to be accepted by all regions when the matching degree is extremely low or low, and it is also difficult to achieve a high matching degree, this article chooses situation 3 for adjustment, starting the first round of degree discrimination and adjustment (Table 5). As shown in Table 5, there is a degree of disharmony among the provinces in the Yellow River Basin. Among them, bold and italicized cells represent regions where the allocation ratio exceeds the upper limit, and the carbon-emission allocation of the province corresponding to the cell is significantly higher than that of the column province corresponding to the cell. For example, the disharmony between Beijing and Jilin provinces, where the allocation ratio exceeds the upper limit, indicates that Beijing has a significantly higher allocation of carbon-emission rights compared to Jilin province. The cells with a gray background represent regions where the allocation ratio has not reached the lower limit. The carbon-emission allocation for the province corresponding to the cell is significantly lower than that for the column province corresponding to the cell. For example, Beijing and Hebei provinces are regions where the allocation ratio has not reached the lower limit, indicating that when compared with Hebei province, Beijing’s carbon-emission rights allocation is significantly lower.

Table 5.

Input parameters of the SBM-DEA model.

It can be observed that in the analysis of the harmony of carbon-emission rights allocation, the allocation amounts in Hebei Province, Jiangsu Province, Shandong Province, and Guangdong Province are relatively high, and there is a degree of disharmony in the allocation amounts between these provinces and other provinces (Figure 6). Specifically, there are significant differences in allocation between Hebei Province and 28 provinces, Jiangsu Province and Shandong Province and 27 provinces, and Guangdong Province and 26 provinces. At the same time, the allocation of carbon-emission rights in Jilin Province, Guizhou Province, and Shaanxi Province is significantly lower, and there is a degree of disharmony between these provinces and 13, 14, 14, and 16 provinces, respectively, indicating that the current carbon-emission rights allocation scheme still needs to be optimized in terms of regional balance.

Figure 6.

Results of degree discrimination.

3.2. Final Allocation Plan for Carbon-Emission Rights

Based on the reverse tracking optimization adjustment method, through multiple iterations and logical deduction until the harmonious discrimination is achieved, it is found that when the directional discrimination thresholds and are set to 0.4 and 0.8, respectively, the size relationship of carbon-emission rights allocation in each province of China is relatively reasonable. At the same time, based on the degree discrimination of comprehensive indicators, under low matching degree, i.e., when the lower limit coefficient is 0.5 and the upper limit coefficient is 1.5, all regions pass the degree discrimination criterion, and the final carbon-emission rights allocation scheme is obtained. As shown in Table 4.

From the final allocation results, the carbon emissions of China’s provincial steel industry in 2030 will be reduced by 539,800 tons compared to the initial allocation. By 2030, the 30 provinces in China can be roughly classified into four categories: firstly, significantly reduced areas, including Beijing, Hainan, Qinghai, Heilongjiang, Guizhou, and Shaanxi, indicating a significant reduction in allocation quotas for these provinces; The second is the moderate reduction zone, including 16 provinces such as Shanxi, Inner Mongolia, Jilin, Shanghai, Jiangxi, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Guangdong, Guangxi, Chongqing, Sichuan, Yunnan, Gansu, Ningxia, and Xinjiang. The allocation weights of these provinces are relatively small compared to the initial allocation amount, indicating that the carbon-emission management in these provinces is relatively mature and can be finely adjusted while maintaining the existing economic and emission balance; The third is to moderately increase the allocation weights for regions including Tianjin, Zhejiang, Anhui, and Fujian, with final allocation weights raised to 2.16%, 3.29%, 3.19%, and 3.06%. The final allocation amount is 83800 tons or more, higher than the initial allocation amount. The fourth is a significant increase in the allocation weights for regions including Hebei, Liaoning, Jiangsu, and Shandong, with final allocation weights raised to 9.94%, 5.37%, 7.34%, and 6.18%, an increase of 10.7326 million tons or more compared to the initial allocation.

Specifically, the adjustment of carbon quotas is a systematic result of the synergistic effect of the three core elements in the allocation system: first, the full life-cycle indicator (weight 44.33%), second, the contribution of energy transformation (weight 23.69%), and third, regional heterogeneity characteristics. As the core regions of steel production capacity, the quota increases in Hebei Province (with a final quota weight of 9.94%) and Jiangsu Province (7.34%) are mainly due to their high historical emission base and significant industrial scale effects (crude steel production accounts for 14.6% and 9.8% of the country’s total). If aggressive quota compression is implemented solely based on emission-reduction targets for high historical emission provinces, it may lead to a surge in operating costs for enterprises, transfer of production capacity across provinces, or systemic risks in the industry. Although such regions are facing short-term pains in green transformation, they have outstanding performance in energy transformation indicators, such as green steel-making technology investment and scrap steel recycling utilization rate. Through the reverse tracking mechanism of the harmonious allocation model (directional threshold 0.4–0.8, upper limit coefficient = 1.5), the quota weights were ultimately increased by 1.54% and 1.01%, respectively, based on initial allocation. This method reflects the quota tilt logic of balancing historical responsibility and transformation potential in two dimensions.

3.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Harmonious Optimization Model

The core objective of this study is to assess the key input parameters of the total amount of carbon-emission quotas in 2030, including carbon-emission reduction targets and GDP growth rate. These parameters are based on clear national policy objectives. Therefore, this study is mainly devoted to the sensitivity analysis of the harmony optimization part.

In this study, the sensitivity analysis of the weight of the harmony discrimination index was carried out, and the random fluctuation of the weight of all indicators was set at about 5% and 10%. In each scenario, two groups of weight schemes are randomly generated, and the differences in the final distribution results under different weight schemes are analyzed. In view of the fact that the data do not conform to the normal distribution, the Friedman difference test was used in this study. The test results showed that the p-value was 0.267, indicating that there was no significant difference in statistical significance. Subsequently, this study used the Nemenyi method to test the pairwise differences under different weight scenarios. The results (see Appendix A Table A3) further confirmed that the weight change had no significant impact on the difference of the final distribution scheme, indicating that the final distribution scheme was less sensitive to the change in index weight.

The sensitivity analysis of the harmony discrimination threshold was carried out. Because the directional discrimination thresholds, and , are the optimal values obtained through optimization iteration, sensitivity analysis is only carried out for the lower limit coefficient and upper limit coefficient of degree discrimination. The baseline scenario is = 0.5, = 1.5, and the loose scenario is set as = 0.25, = 1.75, and the strict scenario is set as = 0.75, = 1.25. The Friedman difference test is also used to analyze the different degree discrimination threshold scenarios. The results showed that the p value was 0.008, indicating that the degree of discrimination threshold had a significant difference effect on the final allocation results, but Cohen’s F value was 0.04, indicating that the difference was small. The Nemenyi method was used to test the pairwise differences between different threshold scenarios. The results showed that the main significant differences came from the loose scenario and the strict scenario. Therefore, the final distribution result is sensitive to the degree of discrimination threshold, but the sensitivity range is small.

3.4. Preliminary Discussion on the Policy Relevance of the Results

On the other hand, in regions such as Beijing (0.00%) and Hainan (0.00%) where significant reductions have been made, based on the positioning of national functional zone planning, the scale of the steel industry in their provinces is extremely small (Beijing’s carbon emissions in the past 5 years are less than 500,000 tons, and Hainan has no large-scale steel enterprises), and the proportion of environmental resource endowment indicators is 12.98%. The harmony model determines the degree of structural mismatch between its initial quota and actual industrial layout through a lower limit coefficient of = 0.5. Finally, the CRL adjustment formula is used to reduce redundant quotas and achieve the goal of regional differentiated allocation that prioritizes ecological functions. This adjustment mechanism deeply links quota changes with industry LCA carbon-emission intensity, energy transformation effectiveness, and regional development positioning through the quantitative weighting of 18 indicators and the harmonious Gini coefficient discrimination, providing a systematic solution for carbon-market quota allocation.

4. Performance Evaluation and Comparison Results of Allocation Schemes

4.1. Fairness

The Gini coefficient is one of the core indicators for measuring fairness in the field of carbon quota research [45,46]. Its value range is 0–1, and 0.2–0.4 is a relatively fair range recognized by the academic community. The smaller the value, the more balanced the distribution.

This study uses the Gini coefficient of population carbon emissions dimension to measure the fairness of regional quotas, and the calculation formula is as follows:

where denotes the population share of region i; denotes the proportion of carbon emissions from the steel industry in region i to the total emissions of China’s steel industry. This indicator can quantitatively evaluate the improvement in regional fairness of the new allocation plan.

4.2. Efficiency of Quota Utilization

Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) is a non-parametric efficiency-evaluation method, which can effectively deal with complex systems with multiple inputs and outputs, so it has been widely used in many fields such as environmental economics [47,48,49,50]. This study constructs an SBM-DEA model based on unexpected output to evaluate the efficiency of initial quota allocation. The model takes labor, capital, and energy as three kinds of input factors, and expected output and unexpected output as output indicators. By solving the linear programming problem with efficiency value as the optimization objective, the quota utilization efficiency value of each evaluation unit is calculated. See Table 5 for specific input indicators. The index data are from China Labor Statistics Yearbook, China Iron and steel industry yearbook, and CEADs database [51,52,53,54,55].

The SBM-DEA model was constructed as follows [56,57]:

In the formula, , and denote slack variables for input factors, desired outputs, and undesired outputs, respectively; , and are vectors of input factors, expected output and unexpected output; denotes the average efficiency of inputs and outputs. When , , and are zero, = 1, the evaluated decision unit is located on the production frontier. N represents the number of input factors, M represents the number of desired outputs, and R represents the number of undesired outputs.

4.3. Marginal Abatement Cost

As a key indicator to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of emission-reduction policies, Marginal Abatement Cost (MAC) is defined as the economic conversion cost or opportunity cost involved in the reduction of unit carbon emissions. Its essence reflects the marginal technology substitution rate between economic output and carbon emissions in the production process. In general, the higher the carbon intensity, the higher the MAC; and vice versa. Among the methods for measuring MAC, the shadow price-based method is the most widely used [58,59]. To this end, based on the SBM-DEA profit maximization framework, this paper measures the MAC of China’s provincial-level regions by calculating the shadow price of carbon emissions and economic output, and using the ratio of the two.

The profit maximization model is constructed as follows:

Equations (21) and (22) are the dual of Equations (19) and (20) and represent the profit maximization of an economy at a given input-output vector shadow price. Among them, , , and represent the shadow prices of input factors, economic output, and carbon emissions, respectively. When production activities are at the frontier of efficiency (i.e., reach the optimal solution state), the marginal technology substitution rate of production conversion is equal to its corresponding shadow price ratio. Solving this equation yields the cost of abatement:

Among them, denotes the market price of economic output, which is generally set at RMB 1; and , respectively, represent the shadow price of economic output and carbon emissions under the optimal solution of Equation (18), and is the MAC. Thus, the MAC for the region is the ratio of carbon emissions to the shadow price of economic output, i.e., the value of economic output forgone per unit of reduced. This transformation relationship in Equation (18) measures the intrinsic link between GDP and carbon emissions.

In the carbon market, the carbon emissions in the above formula are carbon allowances, i.e., the initial carbon-emission rights under the carbon trading mechanism. The total cost or benefit of emission reduction in the region is calculated by the formula:

In the formula, is the initial regional carbon quota and is the actual regional carbon emission.

At that time, > 0 indicates that actual carbon emissions are greater than carbon allowances, i.e., the region has a surplus of carbon emissions and can sell the excess allowances for carbon revenue; conversely, when < 0, it indicates that actual carbon emissions are less than carbon allowances, i.e., the region has a deficit of carbon emissions, and needs to buy carbon allowances and pay the cost of carbon.

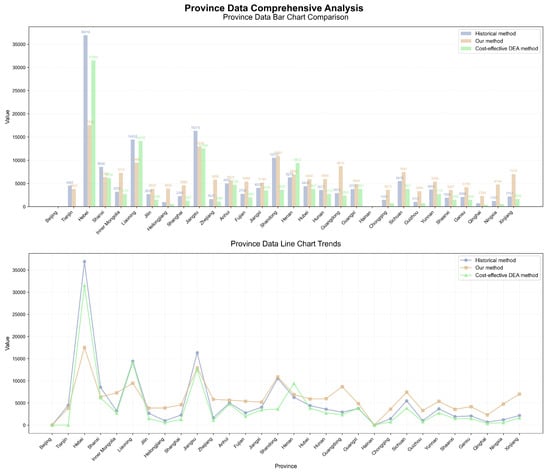

4.4. Solution Comparison

After calculation, the Gini coefficient of this plan is 0.35 (within the reasonable range of 0.2–0.4), the quota utilization efficiency is 0.634, the average marginal emission-reduction cost is 433,500 CNY/ton CO2, and the total emission-reduction cost is 68.273 billion CNY. The results show that the scheme achieves synergistic optimization in four dimensions: fairness (Gini coefficient), efficiency (quota utilization efficiency), feasibility and sustainability (marginal emission-reduction cost), and the emission-reduction cost is within the industry’s affordable range, which meets the sustainable development requirements of low-carbon transformation.

The allocation of carbon quotas, as a key environmental regulatory tool, has differentiated impacts on regional economies due to differences in program design. In the pilot phase of the carbon market, the allocation of quotas in the steel industry mainly relies on the “historical method” or “historical intensity method”. This article sets the historical method as the baseline scenario. In the existing research, Qi’s [38] research is highly similar to the research object in this paper. The comparative analysis of the three key indicators is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Comparison of 3 methods.

A comprehensive comparison of three carbon quota allocation methods: the historical method is simple in calculation and low in data cost, which is suitable for the early establishment of carbon markets in various industries, but it is easy to solidify the high emission pattern and lacks incentives for low-carbon regions; Qi’s DEA model incorporates the double constraints of carbon price and EU CBAM to provide a framework for cross-border carbon cost analysis, but does not consider long-term dynamic factors such as technological progress and industrial structure adjustment; By integrating the indicators of economy, technology, industry characteristics and regional heterogeneity, this study realizes the deep binding between quota allocation and the contribution of carbon emissions and energy transformation in the LCA, and has more comprehensive advantages in indicator coverage and dynamic adaptability.

Further analysis of the emission-reduction costs of this plan shows that there are significant differences in the marginal emission-reduction costs of the steel industry among provinces: 10 provinces, including Beijing, Shanghai, and Hainan, have less than 10,000 CNY; Hebei, Jiangsu, and Guangxi provinces have exceeded 1 million CNY. Based on the spatial distribution characteristics of carbon emissions, five provinces, including Hebei, Liaoning, and Jiangsu, need to bear the cost of carbon emissions, with the steel industry in Hebei and Jiangsu provinces facing significant pressure to reduce emissions; Beijing, Zhejiang, Shanghai, Qinghai, and other provinces can obtain higher emission-reduction benefits due to sufficient carbon-emission space. Specifically, in the benchmark group, Hebei, Tianjin, Shandong, and Guangxi provinces (cities) have higher marginal emission-reduction costs; Under this plan, the costs in all four provinces (cities) have significantly decreased: Hebei has decreased from 5.5721 million CNY to 2.9852 million CNY, Tianjin has decreased from 1.3417 million CNY to 838,600 CNY, Shandong has decreased from 2.8872 million CNY to less than 10,000 CNY, and Guangxi has decreased from 1.2658 million CNY to 1.0286 million CNY. The marginal emission-reduction cost distribution in this plan area is stable (with a standard deviation of 630,800 CNY), while the other two groups have significant volatility.

Overall, based on the perspective of promoting energy transformation, this study constructs an inter-provincial carbon quota allocation scheme for the steel industry that integrates the full life-cycle perspective and regional heterogeneity characteristics. By balancing the principles of fairness, efficiency, feasibility, and sustainability, it is more effective in promoting low-carbon transformation in the steel industry compared to traditional historical methods, providing theoretical support and practical paths for regions with significant regional development differences to achieve emission-reduction goals in a coordinated manner.

5. Research Results and Discussion

This article takes the carbon quota allocation mechanism of China’s provincial steel industry as the research object, integrates the perspective of the entire life cycle and regional heterogeneity characteristics, and constructs a quota allocation system that combines dynamic total quantity regulation and multi-dimensional indicator coordination. The results show that this scheme significantly optimizes the allocation balance compared to the historical method: the weight proportion of the entire life-cycle indicators reaches 44.33%, the standard deviation of regional marginal emission-reduction costs is reduced by 45.4%, and the extreme value ratio is 1.73 (far lower than the international average extreme value ratio of 2.85 for similar schemes). The research innovation points are reflected in: (1) constructing a dynamic carbon quota total control mechanism; (2) The selection of allocation indicators takes into account the contribution of energy transformation; (3) Consider provincial quota schemes that take into account the full life-cycle characteristics and regional heterogeneity of the steel industry. The practical value lies in providing theoretical support for solving the dilemma of “regional one size fits all”.

5.1. Research Findings

- (1)

- Dynamic Total Quantity Control Mechanism

The total quota calculation model based on “benchmark tightening” shows that the total quota of the steel industry will be controlled at 1.77 billion tons in 2030. The dynamic total adjustment mechanism is designed to tighten the quota by 38.26 million tons. The average marginal emission-reduction cost of the new plan is 433,500 CNY/ton CO2, which is 45.4% lower than the historical method (794,400 CNY/ton CO2). The standard deviation of regional emission-reduction cost distribution has decreased from 1.15 million CNY to 630,800 CNY, promoting the transformation of the steel industry from “passive emission reduction” to “active energy transformation”.

- (2)

- Improve the accuracy of quota matching for the LCA and energy transition indicators

Existing studies mainly focus on the carbon-emission intensity in the production process, but pay insufficient attention to the carbon-emission impact of raw material acquisition, logistics and transportation, and product recovery in the iron and steel industry. In this study, LCA indicators were introduced, and key factors such as “scrap recycling rate” were included in the model construction, to achieve a comprehensive assessment of the impact of the industry’s life-cycle carbon emissions. The weight allocation of indicators in this plan deeply responds to policy requirements, with the total weight of the steel industry’s life-cycle indicators and energy transformation indicators accounting for 44.33%, of which the combined weight of energy transformation contribution indicators accounts for 23.69%. The matching degree between quotas and industry low-carbon potential has increased by 23.5% compared to historical methods, and a market-oriented incentive path of “cleaner energy structure and more sufficient quota acquisition” has been constructed.

- (3)

- Regional heterogeneity regulates the balance between fairness and efficiency

The traditional method uses a unified standard to allocate quotas, without considering the differences in regional industrial scale and energy endowment. In this study, the directional threshold and degree coefficient were introduced through the harmonious distribution model, and the quota increased by 1.54% in Hebei and other core areas of production capacity, and decreased to 0.00% in Beijing and other ecological priority areas, highlighting the regional heterogeneity. After iterative optimization through the harmonious allocation model, the Gini coefficient of provincial quotas decreased from 0.45 in the historical method to 0.35, and the efficiency of SBM-DEA quota utilization increased to 0.634. The maximum quota difference between provinces is 175 million tons, reflecting significant heterogeneity in ecological carrying capacity, resource-allocation efficiency, and emission-reduction potential among different regions.

5.2. Policy Suggestions

The steel industry has been included in the context of China’s unified carbon market. Based on research conclusions, it is recommended to optimize the policy guidance framework from the following dimensions:

- (1)

- Taking the national “dual carbon” target as a hard constraint, strictly implementing the quota total control system, and using a dynamic adjustment mechanism to stabilize the total quota of the steel industry in the scientific range by 2030, avoiding the distortion of carbon price signals caused by excessive quota supply. Establish an annual update system for the “dual-dimensional indicators of the LCA and energy transformation”, incorporating core indicators such as scrap steel recovery rate, and industry energy structure into the dynamic adjustment factors of quotas, and forming an adjustment mechanism that directly links the effectiveness of energy transformation with the ability to obtain quotas.

- (2)

- Establish a low-carbon transformation fund, directing paid quota income towards the scrap steel recycling systems in traditional industrial provinces such as Shanxi and Shaanxi, and reducing energy transformation costs through regional collaboration; For enterprises with a high proportion of short process steel-making and a large proportion of green electricity, they are allowed to use CCER to offset the quota clearance ratio and increase it to 15% (usually 5%), and be prioritized for inclusion in the list of carbon price pilot enterprises. Carbon price leverage is used to incentivize energy structure optimization and ensure fair sharing of regional emission-reduction responsibilities under the total control target.

- (3)

- Build a national carbon footprint tracing platform for the steel industry, integrate energy consumption and carbon emissions data for the entire chain of “raw materials production transportation”, and provide accurate accounting basis for quota total amount verification and carbon price formation; Fully implement the “quota reserve and carbon price linkage adjustment mechanism”, initiate quota repurchase when carbon prices continue to decline (the annual repurchase amount shall not exceed 5% of the total quota), and release reserve quotas if they are too high (the single release amount shall not exceed 10% of the total reserve amount), stabilize the carbon price range through market-oriented means, and guide enterprises to increase long-term energy transformation investment under the constraint of total quantity control.

- (4)

- With the continuous improvement of the national carbon market, the steel industry, as a key emission control industry, is expected to gradually improve the accuracy of the carbon-emission data indicators directly submitted by its enterprises. In this process, the soundness of the Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) system cannot be achieved without the joint investment and cost-sharing of the government and enterprises in the initial stage. For small and medium-sized steel enterprises with relatively weak technological foundations, it is recommended to establish a reasonable policy transition period and provide special subsidies for equipment updates and digital transformation. At the same time, by building a unified integrated data management platform and combining it with trusted certification technologies such as blockchain, data transparency and reliability can be comprehensively improved, providing a continuous and robust data foundation and support guarantee for the green and low-carbon transformation and energy structure optimization of the steel industry.

5.3. Shortcomings and Prospects

There are some shortcomings in this study that need to be further improved in the future. The selection of data level indicators and quota calculation relies on existing steel industry data. Due to incomplete disclosure of carbon-emission data by enterprises, the model may rely on non-core data, which affects the accuracy and adaptability of the results. In terms of data timeliness and long-term forecasting, the lack of long-term target data limits long-term estimation and weakens the guiding significance of the model for long-term policies.

In response to the above shortcomings, optimization can be carried out from two aspects in the future. At the data level, relying on the industry’s carbon market and the improvement of enterprise data disclosure mechanisms, expanding core data sources (such as direct reporting of carbon emissions and full life-cycle energy consumption data by enterprises), and combining carbon footprint tracking technology to enhance quota refinement and dynamic adjustment. At the long-term forecasting level, combining IPCC climate scenarios with machine learning algorithms, we predict long-term carbon-emission intensity targets, expand the time applicability of the model, and provide long-term tools for cross-cycle carbon quota adjustments.

Author Contributions

K.C., X.X. and Z.G. contributed to conceptualization and validation. K.C. and H.L. were responsible for methodology, resources, writing—review and editing, visualization, and supervision. Z.G. performed software development, investigation, data curation, and writing—original draft preparation. X.X. contributed to funding acquisition. X.T. contributed to writing—review, editing, and visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in CEADs (Carbon Emission Accounts and Datasets) at https://www.ceads.net/.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SBM-DEA | Slacks-Based Measure Data Envelopment Analysis |

| China NBS | China National Bureau of Statistics |

| CEADs | Carbon-Emission Accounts and Datasets |

| CNRDs | Chinese Research Data Services Platform |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| MAC | Marginal Abatement Cost |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Quota allocation methods in China’s carbon-emission trading pilot market (Steel industry).

Table A1.

Quota allocation methods in China’s carbon-emission trading pilot market (Steel industry).

| Markets | Allocation Methods | Allocation Formula | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shanghai | Historical Intensity Decline Method | Enterprise annual base quota = ∑ historical intensity × annual product | Shanghai Carbon Quota Allocation Program for 2017 |

| Hubei | Historical Method | Quota due = historical emission base industry × emission control coefficient × market adjustment factor ÷ 12 × number of months of production | Hubei Carbon-Emission Right Quota Allocation Program for 2017 |

| Guangdong | Baseline Method (long process); Historical Emissions Method (short process) | Enterprise quota = production × baseline value (long process); Enterprise quota = historical average carbon emissions × annual decrease factor (short process) | Guangdong Carbon-Emission Quota Allocation Implementation Program for 2017 |

| Fujian | Historical Intensity Decline Method | Unit quota = Historical intensity value × Emission-reduction factor × Production | Fujian Carbon-Emission Quota Allocation Implementation Program for 2016 |

| Beijing | Historical Method | Enterprise quota = Existing quota + New quota + Quota adjustment | Notice on Matters Concerning Approval of Carbon Dioxide Carbon-Emission Allowance for Key Emission Units for 2016 |

| Tianjin | Historical Method | Enterprise quota = Emission base × Performance base × Industry emission control factor | Tianjin Pilot Carbon-Emission Right Trading Incorporated into the Carbon-Emission Allowance Allocation Program for Enterprises (for Trial Implementation) |

| Shenzhen | Historical Method | Actual quota = Statistical indicator data × Annual carbon intensity target | Notice of Shenzhen Municipal Development and Reform Commission on Carbon-Emission Right Trading for the Year 2016 |

| Chongqing | Business Owned Declarations | The upper limit shall be determined according to the carbon-emission reduction target of the city issued by the State. | Chongqing Carbon-Emission Allowance Management Rules (for Trial Implementation) |

Figure A1.

Correlation matrix (heatmap) of the carbon quota allocation indicators.

Table A2.

Correlation matrix of the harmony discrimination indicator system.

Table A2.

Correlation matrix of the harmony discrimination indicator system.

| Resident Population | GDP | Environmental Pollution Control Investment | Historical Carbon Emissions of Industry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resident Population | 1 | 0 | ||

| GDP | 0.78 | 1 | ||

| Environmental Pollution Control Investment | 0.54 | 0.48 | 1 | |

| Historical Carbon Emissions of Industry | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 1 |

Table A3.

Correlation matrix of the harmony discrimination indicator system.

Table A3.

Correlation matrix of the harmony discrimination indicator system.

| Weight Scenario | Statistic | p-Value | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|

| = 0.25; = 0.24; = 0.21; = 0.29 VS Benchmark Weight | 1.501 | 0.803 | 0 |

| = 0.33; = 0.18; = 0.19; = 0.30 VS Benchmark Weight | 0.346 | 0.9 | 0 |

| = 0.38; = 0.10; = 0.31; = 0.21 VS Benchmark Weight | 1.848 | 0.664 | 0 |

| = 0.41; = 0.26; = 0.10; = 0.23 VS Benchmark Weight | 0.693 | 0.9 | 0 |

References

- Zhu, J.; Fan, Y.; Deng, X.; Xue, L. Low-carbon innovation induced by emissions trading in China. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawzy, S.; Osman, A.I.; Doran, J.; Rooney, D.W. Strategies for mitigation of climate change: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 2069–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, F.; Anwar, A.; Hsu, C.C.; Sharif, A.; Razzaq, A.; Sinha, A. The role of information and communication technology in encountering environmental degradation: Proposing an SDG framework for the BRICS countries. Technol. Soc. 2021, 65, 101587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, J. Holding High the Great Banner of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics and Striving in Unity for the Comprehensive Construction of a Modernized Socialist Country-Report at the Twentieth National Congress of the Communist Party of China; People’s Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2022; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Xinhua News Agency. Proposal of the CPC Central Committee on Formulating the 15th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development. Xinhua News Agency 2025. Available online: https://english.news.cn/20251028/efbfd0c774fd4b1c8daeb741c0351431/c.html (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Zhu, J.; Ge, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Wang, C. Evaluating regional carbon emissions trading in China: Effects, pathways, co-benefits, spillovers, and prospects. Clim. Policy 2022, 22, 918–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, X.; Zhang, D.; Geng, Y.; Tian, L.; Fan, Y.; Chen, W. Research on Energy Economic Transformation Paths and Policies Under the Carbon Neutrality Target. Manag. World 2022, 38, 35–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Cao, X. Study on the lmpact of EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism onChina’s trade:GTAP-E model simulation analysis based on dynamic recursion. World Econ. Stud. 2024, 39, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Zheng, M.; Liu, W.; Gu, Y.; Xing, Y.; Pan, C. Impacts of carbon border adjustment mechanism on the development of chinese steel enterprises and government management decisions: A tripartite evolutionary game analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.W.; Wang, S.; Li, X.D. Research Progress on Tariff Absorption in International Trade: And a Theoretical Framework. J. Int. Trade 2018, 5, 160–174. [Google Scholar]

- General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Opinions on Promoting Green and Low-Carbon Transition and Strengthening the Construction of the National Carbon Market; Policy Document Issued by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council; General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- De Perthuis, C.; Trotignon, R. Governance of CO2 markets: Lessons from the EU ETS. Energy Policy 2014, 75, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohringer, C.; Lange, A. On the Design of Optimal Grandfathering Schemes for Emission Allowances. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2004, 49, 2041–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Li, H. A multi-criteria decision analysis model for carbon emission quota allocation in China’s east coastal areas: Efficiency and equity. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Chen, C. Reward and punishment scheme of China’s provincial carbon emission reduction based on the allocation of carbon emission rights. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2020, 30, 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, P.; Fu, H. A dynamic multi-criteria allocation of carbon emission reduction responsibility towards carbon neutrality: Evidence from Hubei Province. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Zhang, Q.; Ye, R.; Zhou, Y. Allocating China’s carbon emission allowance to the provincial quotas in the context of the Paris Agreement. Acta Sci. Circumstantiae 2018, 38, 1224–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, B.; Wang, Z.; Yan, J.; Gong, L. Two-stage allocation model for carbon emission rights of provincial power sector under the goal of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality. Stat. Decis. 2023, 39, 168–173. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X.; Zhao, T.; Wang, J. Allocation of carbon emission quotas in China’s provincial power sector based on entropy method and ZSG-DEA. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 284, 124683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katta, B.; Sambandam, M.; Premalatha, M. Life cycle and economic assessment of recycled steel using waste heat in industry. J. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, S.; Du, T.; Wang, Y. Life Cycle Assessment and Environmental Impact Evaluation of CCU Technology Schemes in Steel Plants. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Zou, S. Provincial allocation of carbon emission quotas and assessment of carbon-reduction potential in the yellow river basin under the constraint of 2030 carbon intensity target. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2022, 42, 230–239. [Google Scholar]

- Linghu, D.; Peng, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhu, B. Initial Carbon Quota Allocation at Provincial Level in china from the New Development Concept. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2024, 11, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Action Plan for Carbon Dioxide Peaking Before 2030; Technical Report Guo Fa [2021] No. 23; State Council of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China. Work Plan for Covering Iron & Steel, Cement, and Aluminum Smelting Industries in the National Carbon Emission Trading Market. 2024. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk03/202503/t20250326_1104736.html (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Zou, X.; Chen, Z. Estimation and Prediction of China’s Potential Economic Growth Rate. China Price 2025, 3, 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Jiang, W.; Tang, Z.; Han, M. Research on the Pathway to Achieving Carbon Peak in China Before 2030—A Combined Analysis Based on GDP Growth Rate. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2022, 52, 1268–1282. [Google Scholar]

- National Development and Reform Commission. Iron and Steel Industry Energy Conservation and Carbon Reduction Special Action Plan; Technical Report; National Development and Reform Commission: Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]