Abstract

This study investigates the transferability of measured road-damage data between distinct geographic domains using the YOLOv8s deep-learning framework. A comparative evaluation was performed on two datasets: the locally developed RDD2024_SA (South Africa) and the publicly available RDD2022_India (India). Five training–testing scenarios were designed to analyze intra- and inter-dataset generalization, emphasizing the influence of dataset scale, annotation consistency, and class structure on detection performance. When trained and tested within the same domain, YOLOv8s achieved high accuracy (mAP@0.5 > 0.95), confirming the strength of localized feature learning. However, performance degraded substantially under cross-domain testing, revealing a sensitivity to differences in road texture, illumination, and labeling style. Reducing the number of classes from six to four dominant types improved stability (mAP@0.5 ≈ 0.78) by mitigating annotation noise and class imbalance. Furthermore, a transfer-learning configuration, in which the India-trained model was fine-tuned on 20% of the South-African dataset, achieved mAP@0.5 = 0.86, demonstrating effective recovery of cross-domain detection performance. These findings highlight the importance of domain-aligned data preparation, targeted fine-tuning, and balanced class representation in building robust and transferable AI systems for sustainable, data-driven road maintenance.

1. Introduction

Since the early 1980s, road maintenance has become a focus for many municipalities around the world. With proper and frequent maintenance, the design life of roads may be significantly extended. Typically, the cost of reconstruction of a deteriorated road, due to lack of maintenance, may be more than three times the cost of preserving a road through frequent maintenance [1]. Most road damage recognition strategies for rural roads are based on onerous visual inspections. Visual inspection is the primary method for evaluating the physical and operational state of road infrastructures [2]. These may involve closing off the inspected road or lane from traffic, thereby diverting traffic to alternative routes, which may result in traffic congestion on those routes. Properly maintained road networks are one of the central goals of the United Nations’ ninth sustainable development goal (UN-SDG 9), which aims to build resilient infrastructure [3]. In fact, a good road network ensures accessibility to schools, health centers, markets, industry, urban centers, and other places that are key to good livelihoods. Therefore, just as sustainable transport is mainstreamed across all the United Nations SDGs, properly maintained road networks are the lifeblood of the economy [4]. Road damage, such as potholes and cracks, is one of the reasons for traffic accidents in the United States and around the world, which may lead to deaths and/or loss of well-being. It is further reported that road surfaces that are properly maintained and monitored improve comfort, fuel efficiency, and user safety [5].

Preventive maintenance is crucial for aged pavements (over 15 years old) as they tend to degrade much more quickly than new pavements. At the same time, routine preventive maintenance may be too costly for road agencies in low- and medium-income economies, such as South Africa and India. In these economies, it is therefore common for road agencies to prioritize strategic national road networks, thereby justifiably neglecting local and feeder road networks that connect communities to essential amenities. These local and feeder road networks tend to be subjected to some form of breakdown maintenance, where repair actions are triggered by the occurrence of major road damage. In addition to the deprivation that societies suffer due to a poor road network, this results in heavily patched-up roads that are uncomfortable for use and, eventually, the need for total rehabilitation of the road, which is extremely expensive. However, it is expected that these challenges can be put under control with early detection of road damage and timely maintenance actions [6]. Early detection of damage, requiring maintenance action, can be achieved through the implementation of a condition-triggered strategy. For roads, roughness has traditionally been used as a primary indicator for pavement condition, as evidenced by the wide usage of different forms of roughness indicators in road maintenance decision-making. Road roughness includes everything from cracks to potholes to random deviations in a profile. As disintegration progresses down the pavement layers over time, these cracks and potholes could become much worse. The most common road distress is divided into four major classes: crack, pothole and patch, surface defects, and surface deformations [7]. Each of these distress types requires different repair actions. Thus, it is obvious that knowledge of the type of distress is useful for deciding what repair action should be deployed to the affected road network. However, the challenge is that around the world, road agencies must deal with road transport infrastructure that must be kept operational through constant maintenance operations [8,9]. It is expected that the increase in the figures can be put under control with early detection of road damage and timely maintenance actions [6]. The goals of road maintenance and rehabilitation are to maintain the pavement network in the best possible condition while lowering costs, improving service levels, lowering greenhouse gas emissions, and enhancing road user safety [8].

The traditional methods for identifying road damage and distress are deemed intricate and inadequate when handling a substantial volume of images. For assessing road damage distress, human or semi-automated data collection is presently one of the most utilized approaches [10]. However, these methods, like human visual inspection, may be an easy way to monitor a road’s condition, but they are impractical because they are costly, time-consuming, and labor-intensive. Instead, more efficient road condition monitoring systems are needed to thwart the challenges that are faced by the traditional methods, which are still in common use [11].

Numerous efforts have been made to create a system that combines in-car camera recordings with image processing technology to analyze road properties and examine road surfaces more effectively [12]. Image-based analysis and exploitation remain one of the most studied ways of monitoring and determining defects in roads. The creation of model-based pothole detection algorithms has been prompted by the advancement of image processing techniques and the accessibility of inexpensive camera equipment. The different types of cameras, like smartphone cameras, rangefinder cameras, mirrorless cameras, single-lens reflex cameras, etc., produce a large source of road data [13].

Deep learning, in particular, convolutional neural networks (CNNs), has demonstrated significant potential among artificial intelligence (AI) techniques for identifying road defects like potholes, cracks, rutting, and patches. High-accuracy real-time analysis is now feasible thanks to object detection algorithms like YOLO (You Only Look Once), which empowers municipal planners and infrastructure managers to make well-informed maintenance decisions. Despite these developments, a gap still exists in evaluating the generalizability of modern algorithms such as YOLOv8 when used on geographically and visually distinct datasets. Few studies have specifically looked at how models trained on datasets obtained in one geographical and climatic region might perform when applied to a different geographical and climatic region.

In this study, two objectives have been identified: to implement the YOLOv8s algorithm for automated detection and classification of road damage using smartphone images and to evaluate the model’s performance across five distinct training–testing scenarios involving datasets obtained from Pretoria and Johannesburg in South Africa, and India.

2. Related Work

2.1. Traditional and Machine Learning Methods for Road Damage Detection

Early approaches to road damage detection used basic image processing methods, such as thresholding and edge detection, to segment road defects. For example, Bertozzi and Broggi [14] proposed one of the earliest frameworks for road crack detection using intensity variation analysis. While foundational, such methods are limited in accuracy under variable lighting and surface conditions. To improve performance, researchers introduced machine learning techniques, such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN). Recent advancements in hardware computing power and sensor technology have facilitated the application of high-accuracy techniques, with many state-of-the-art algorithms for identifying and detecting road damage by employing machine learning methods [15]. Hoang [16] applied both ANN and Least Squares SVM (LS-SVM) to detect potholes from digital images processed using Gaussian filters and steerable filters, achieving a classification accuracy of 85% and 89%, respectively. Machine learning, particularly deep learning techniques, has become prominent in identifying roads and detecting road damage.

2.2. Deep Learning with CNNs and Object Detection Models

Over the past decade, there has been significant progress in object and feature detection derived from image analysis, leading to the emergence of convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which have demonstrated superior performance in classifying and visualizing images [17]. With the rise of deep learning, CNNs have become the dominant approach for road surface damage identification. Zhang et al. [18] demonstrated a CNN-based framework capable of detecting cracks in images captured by smartphone cameras. Their study showed that CNNs outperform traditional handcrafted feature methods by learning representations directly from the data. Additionally, Asian et al. [19] presented a framework for automating the roadway condition evaluation that is based on deep learning. They classified four types of road damage, namely, potholes, longitudinal cracks, transverse cracks, and alligator cracks, using a CNN, which was applied to images that were acquired from online internet search engines to construct the crack detection dataset. The developed CNN achieved an overall accuracy of 76%, indicating its suitability for the task. Over the years, other articles have explored the use of convolutional neural networks for road surface and road damage identification [12,13,20,21].

Significant progress has been made in using CNNs to classify road damage and distress. The use of CNN for classifying road distress was further studied in 2020 [22]. They applied the RetinaNet architecture with VGG16 as the backbone to the asphalt road dataset, comprising over 45,000 instances of various distress types. The model demonstrated superior performance compared to other existing object detection models, such as YOLO- and LBP (Local Binary Patterns)-based object detectors. The model’s small memory footprint facilitates its integration into mobile systems.

In a similar vein, Zhang et al. [23] introduced a road condition monitoring technique based on Faster R-CNN, which is a two-stage detector. This technique enables autonomous detection and localization of cracks, potholes, oil bleeding, and dot surfaces. Utilizing 6498 pavement photographs, they trained and evaluated 20 Faster R-CNNs, among which the best-performing model achieved accuracy rates, recall rates, and location errors of 90.4%, 89.1%, and 6.521 pixels, respectively. The Faster R-CNN exhibited more precise localization of pavement distresses compared to the CNN plus K-value technique. Two-stage detectors have good performance in small object detection and achieve high mAP, but are slower in computation. Baek et al. [24] also proposed a classification model for road pothole detection using edge detection and pothole images as input images. The input image data, which were acquired in red, green, and blue (RGB) color scales, were then converted into grayscale to reduce computational power. All other objects were detected using the object detection algorithm, while road potholes were detected and classified using the YOLO algorithm. In practice, images containing potholes and cracks are processed using Convolutional Neural Networks trained using image patches. These networks classify roads with potholes as positive and those without as negative, enabling easy identification and recognition of potholes.

Successive versions of YOLO, a one-stage detector (v3, v4, v5, and v8), have been tested across numerous road damage datasets, consistently demonstrating improvement in speed, accuracy, and model efficiency, although the detection accuracy might not be very high. Park, Tran, and Lee [25] applied three CNN-based object detection YOLO models (YOLOv4, YOLOv4-tiny, YOLOv5s), using 665 road pothole images each having an image size of 720 × 720 pixels as input, for the detection of road potholes. The YOLO models were used to train, test, and validate the image data subsets of the road potholes. To measure and evaluate the performance of the models, mean average precision at 50% (mAP@0.5) intersection-over-union was used. The results indicated that the YOLOv4-tiny was the better model fit for the detection of road potholes with an mAP@0.5 of 78.7%, while YOLOv4 was next with 77.7%, followed by YOLOv5s with 74.8%. Zhou et al. [26] introduced an enhancement technique for pavement crack detection by improving the YOLOv5s model with Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks, Simplified Spatial Pyramid Pooling-Fast (SimSPPF), and transposed convolution. Compared to YOLOv3-tiny, YOLOv5s, and YOLOv7, the proposed model improves training efficiency, reducing the 500-epoch training time to 2.4 h. It achieved a 90.5% accuracy, 91.6% accuracy, and an mAP of 93.6%. Performance gains over YOLOv5s include a 0.7% higher F1 score, a 0.2% mAP increase, and 1.54% faster frames per second (fps), making it more effective for real-time crack detection. Subsequently, the study by Zhang et al. [27] enhances pavement distress detection using YOLOv5 with optimized anchor frame selection, an Automatic Road Distress detection system (ARDs) attention mechanism, and Content-Aware ReAssembly of FEatures (CARAFE) up-sampling. As a result of this study, a new dataset called ARDs-5, comprising 21,797 images, was created for training. The ARD-YOLO model achieved a 75.8 mAP, outperforming baseline models. When used to evaluate a road in Liaoning, China, it performed well, demonstrating how useful it is for assessing pavements in the real world. However, many of these studies are trained and tested on single-region datasets, limiting the generalizability of the trained models.

Recent research has therefore explored feature alignment across sensing domains to mitigate domain shift in object detection. For instance, R. Zhang et al. [28] proposed Deep-IRTarget, a dual-domain feature extraction and allocation framework that jointly exploits spatial and frequency-domain representations to enhance target detection robustness under changing illumination and background conditions. Building on this, Z. Zhang et al. [29] introduced a Differential Feature Awareness Network within Antagonistic Learning to improve cross-modal consistency between infrared and visible imagery, thereby strengthening detection performance across heterogeneous datasets. These approaches demonstrate that multi-domain feature calibration and adversarial alignment can significantly enhance cross-domain generalization, a challenge conceptually similar to that observed between the RDD2024_SA and RDD2022_India road-damage datasets considered in this study.

Little research has been conducted in rigorously evaluating how models like YOLOv8 function when used across multiple domains, despite the effectiveness of CNN-based techniques, for example, training on an Indian dataset and testing on South African road conditions. This study addresses this gap by comparing intra- and cross-dataset generalization of YOLOv8s using a combination of images collected from smartphones and publicly available data.

2.3. Smartphone-Based Damage Detection

Smartphone technology has advanced significantly in recent years, and examples of road inspection by utilizing smartphone cameras and sensors are becoming more prevalent. In recent years, mobile devices, like smartphones, have been equipped with sensors (e.g., accelerometers, gyroscopes, and GPS) and high-resolution cameras, making them effective for road condition assessment. Smartphones are advantageous because they make it possible to evaluate the road surface of extensive road networks quickly, affordably, and with minimal intervention from humans. The smartphone devices can be mounted on trucks, service vehicles like cabs, and cars. Two main smartphone-based approaches have been widely reported in the literature.

The first approach is the basic use of smartphones for on-board vibration measurement, which is then transformed into roughness data by using algorithms. These approaches are essentially a form of response-type road roughness measuring system (RTRRMS), which constitutes an inexpensive way to track road surface changes daily. These systems are therefore preferred for their simplicity in operation, portability, and scalability. Their shortcomings include poor data resolution, battery energy demands, and data costs, and they are known to achieve moderate estimation accuracies [30,31,32,33,34], although Allouch et al. [35] reported having managed to attain accuracies higher than 98% by using accelerometer and gyroscope data acquired through a smartphone. Extending this approach, Takahashi et al. [36] demonstrated that even a smartphone in a cyclist’s pocket could reliably measure road roughness via sensors.

The second class of smartphone-based approaches identifies road damage via algorithms that process road image data. Mertz et al. [37] suggested a method to process road photographs captured by on-board smartphones deployed in daily driven cars. Alfarrarjeh et al. [11] used smartphone technology to capture different road damages to plan maintenance resources efficiently. Maeda et al. [12], on the other hand, utilized smartphones to capture road damage, which was then classified into eight classes.

In this study, a dataset of road damage photographs has been created utilizing road images that were taken using a smartphone on a standard passenger car’s dashboard. Although smartphone-based damage detection systems have shown promise, limited research exists on evaluating their generalizability across different countries or data collection methods. This study addresses that gap by comparing the YOLOv8s models on both international and locally collected datasets.

3. Materials and Methods

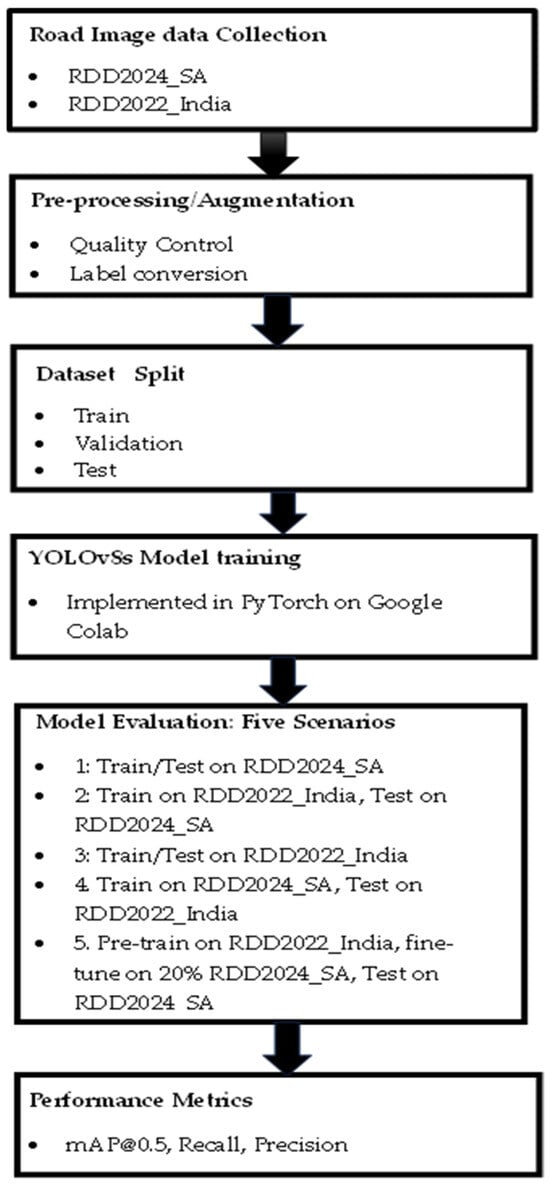

The methodology proposed in this article is split into the segments shown in Figure 1. The flowchart in the figure describes the end-to-end pipeline employed in this study, which utilized YOLOv8 for road damage detection. The process starts with road damage data gathering, which includes the Pretoria/Johannesburg data gathering and the RDD2022_India collection. This is followed by pre-processing and data augmentation, during which quality control is performed to ensure image and annotation consistency. Label conversion was also performed during this phase to ensure that it conforms to the YOLO format for dataset training. After this, the dataset is divided into training, validation, and testing to facilitate model development and evaluation.

Figure 1.

The flowchart of the research methodology from road image data collection to visualization and results reporting in the form of road damage classes.

The next phase involves model training using YOLOv8s, which is implemented in PyTorch 2.1.0 + cu126 and executed in the Google Colab cloud platform using an NVIDIA T4 GPU (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) to leverage GPU acceleration. The next stage involves model evaluation across five distinct scenarios to assess its generalization capabilities: (1) training and testing on RDD2024_SA (in-domain evaluation), (2) training on RDD2022_India and testing on RDD2024_SA (cross-domain transfer: India–SA), (3) training and testing on RDD2022_India dataset (intra-dataset evaluation), (4) training on RDD2024_SA and testing on RDD2022_India (cross-domain transfer: SA–India), and (5) a transfer-learning configuration in which the model pretrained on RDD2022_India was fine-tuned using 20% of the RDD2024_SA images and then evaluated on the RDD2024_SA test set. The performance metrics, such as mean Average Precision at 0.5 IoU (mAP@0.5), recall, and precision, were finally used to quantitatively assess the model’s performance across these evaluation scenarios.

4. CNN Algorithm-Based Classification

One of the key elements in the testing process is a fully connected neural network known as a convolutional neural network (CNN). CNNs are known for their superiority over other artificial neural networks, given their ability to process visual, textual, and audio data. The primary benefit of CNN is the automatic detection of significant features without human guidance. The CNN architecture is made of three main layers, namely: convolutional layers, pooling layers, and fully connected layers (FC).

The first two layers (convolutional and pooling layers) of the CNN model are for feature learning/extraction, while the second layer (connected layer) is for classification. In the first two layers, a convolution tool, called feature extraction/learning, attempts to recognize and isolate distinct aspects of a picture for analysis. The extracted features are then passed from the convolutional layer to the pooling layer, which is responsible for reducing the spatial size of the convolved feature map to reduce computing needs. The decrease in the required computing power is necessary for processing the data with a significant reduction in data dimension. There are two types of pooling, namely, max pooling and average pooling. In max pooling, the largest element is calculated from the feature map, while in average pooling, the element’s average in a predefined image size segment is obtained. The second layer constitutes the output of the convolution process and is made up of a fully connected layer that predicts the image’s class by using previously extracted features.

4.1. YOLOv8 Model Overview

YOLOv8 is a computer vision model architecture developed by Ultralytics, which is used for object detection, image classification, and instance segmentation tasks. YOLO is a series of models that has become famous in the computer vision world and has grown tremendously since its first launch in 2015 with the introduction of the 5 series (YOLOv5). Subsequently, there have been other releases up to the 11 series.

There are five sizes of YOLO models in the 8 series-nano (8n), small (8s), medium (8m), large (8l), and extra-large (8x). In this study, the YOLOv8s algorithm model is utilized. The adoption of YOLOv8s is because of its accuracy, latency balance, enhanced detection head, and training pipeline versus earlier YOLO versions. It also has reliable open tooling, which together supports reproducible experiments on resource-constrained setups. As our focus is on domain transferability, we treat YOLOv8s as a strong baseline.

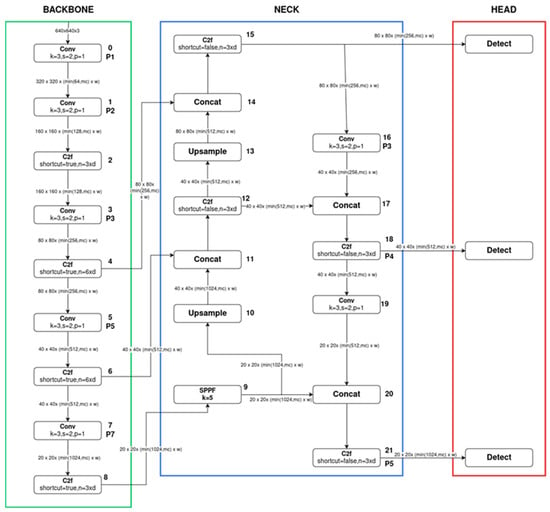

The algorithm structure consists of four main components: the input layer, the Backbone, the neck and detection head. The Backbone layer is the deep learning architecture that acts as a feature extractor for our road dataset images. The features gathered from the different Backbone module layers are combined in the Neck layer. The Head layer, which is the result of the object detection model, forecasts the classes and the bounding box of the objects. Figure 2 is an architecture of the YOLOv8 model.

Figure 2.

Architecture of the YOLOv8 CNN showing the Backbone, Neck, and Head layers with their attendant components within each layer [38].

4.2. Performance Metrics

Three metrics have been used to measure the performance of the various damage classification algorithms [36]. These metrics include the following: recall, precision, and accuracy. The following are the mathematical expressions that define each of the metrics.

Recall assesses the capability of the model to detect all relevant instances. It examines the completeness of the positive prediction. The number of accurately predicted positive cases is known as TP, where FN is the number of true positive cases that were incorrectly identified as negative.

Precision assesses how well the model predicts positive outcomes. It evaluates how accurate the positive predictions are. The number of true negative cases that were incorrectly reported as positive is known as false positives (FP).

Mean Average Precision (mAP) represents the mean value of the Average Precision (AP) scores computed across all different categories. The AP quantifies the area under the Precision–Recall (P–R) curve for each class, describing the relationship between precision and recall at different confidence thresholds. A higher mAP indicates superior overall detection performance. The standard evaluation practice compares AP values at an Intersection-over-Union (IoU) threshold of 0.5. The metric is expressed mathematically as:

where APk is the average precision for the kth class, and n is the total number of classes.

Statistical uncertainty: For each metric, performance variability will be reported as mean ± standard deviation across repeated training seeds, together with bootstrap 95% confidence intervals obtained by resampling test images. Owing to the pilot scale of the RDD2024_SA dataset and computational limitations, the current results are based on single-run estimates and should therefore be interpreted as point values. This limitation is acknowledged, and future work will incorporate repeated-seed experiments to strengthen statistical reliability.

5. Experimental Method

5.1. Road Image Data Collection

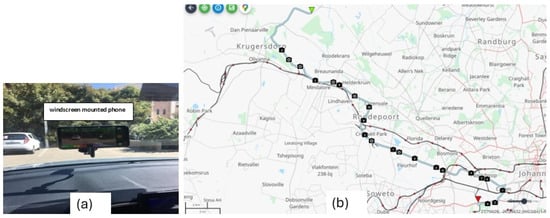

Nowadays, most smartphones are equipped with high-quality cameras and global positioning systems (GPS). In this study, a Samsung Galaxy A70 smartphone (Samsung Electronics, Suwon, South Korea), which was mounted in a custom-made jig fixed on top of the car windshield, was used in the measurement of road surface images. Figure 3a shows the position and orientation of the smartphone to enable it to capture clear road surface images. This smartphone has a screen resolution of 2340 × 1080 pixels at an aspect ratio of 19.5 to 9. Its main camera is 16 MP with an aperture size of F1.7 and a focal length equal to 13 mm. It has a video recording capacity of 1920 × 1080 full high definition at 30 frames per second (fps).

Figure 3.

(a) The positioning and orientation of the smartphone in a jig mounted on the car’s windshield. (b) A sample 40 km section of the road that was used for data collection in Johannesburg.

The image data were measured over a total of one hundred different 100 m road sections in Pretoria and Johannesburg in South Africa. These roads are managed by the Tshwane and Johannesburg Municipality Road Agencies. Figure 3b shows a map of the section of the road network around Johannesburg where the measurements were conducted. In this study, the images were captured while the car was moving at an average speed of 20 km/h (approx. 5 m/s). For a 100 m road section, there were a total of 600 frames that were captured, with each frame having 1920 × 1080 pixels. Thus, the total data size from a 100 m road section can be estimated to be 1.244 GB for black and white images or 3.732 GB for color images.

5.1.1. Road Damage Dataset

A lot of open data sources for road damage are available to be used for free by the public. Our model was trained on one of the publicly available datasets, known as the road damage dataset from 2022 (RDD2022). This dataset has a total number of 47,420 annotated images of road damage collected from India, the Czech Republic, Japan, Norway, China, and the United States. For efficient processing, the format of the data, which is in XML, is converted to TXT. For this study, a dataset from India (RDD2022_India) is used as the road defect type. Some of the road defects considered were alligator cracks, potholes, longitudinal cracks, transverse cracks, as well as other road markings, which may not necessarily fall into the category of defects but are also important as they are significant features on the road, including white line blur and crosswalk blur.

The devices used to capture the images from India included smartphones, high-resolution cameras, and Google Street View. The dataset was used for training and validation. The total number of images in the RDD2022_India is 4205. The RDD2024_SA dataset from Pretoria and Johannesburg roads (Pretoria/Johannesburg dataset) in South Africa consists of 489 images. Samples of the RD2022_india dataset measured in India are shown in Figure 4, while samples of the RDD2024_SA dataset from Pretoria and Johannesburg, South Africa, are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 4.

A selected sample of RDD2022_India Dataset.

Figure 5.

A selected sample of the RDD2024_SA Dataset.

Data collection for the RDD2024_SA dataset was conducted primarily between 10:00 a.m. and 2:00 p.m. in the Johannesburg and Pretoria metropolitan areas under predominantly clear to partly cloudy sky conditions during the dry season (May–September). These daylight hours ensured stable illumination and minimized shadow artifacts from nearby structures and vehicles. The midday solar elevation produced high surface reflectance and consistent color temperature, which improved crack visibility on lighter pavements but occasionally caused specular glare on smooth asphalt sections. Such lighting uniformity benefits in-domain model training yet may reduce robustness when deployed under overcast or low-light conditions typical of other regions. The captured road-vehicle speeds averaged 30–50 km h−1, influencing motion blur and spatial resolution. These optical and environmental factors were therefore considered when interpreting cross-domain generalization performance.

While RDD2024_SA (489 images) provides a valuable local benchmark, its scale increases the risk of overfitting and limits external validity. To address this, we used stronger augmentation (flip, contrast ±20%, saturation ±10%), class weighting, early stopping, and a conservative learning rate. Accordingly, Scenario-1 results should be interpreted as in-domain ceiling performance, not as evidence of cross-domain robustness.

5.1.2. Data Preprocessing and Image Annotation

Certain steps were taken to improve the performance of the model, namely, balancing the dataset, data augmentation, model tuning, and class weights. The Data Augmentation (DA) technique was utilized to increase the range of images. This assisted the model in learning more robust features. DA can greatly lower validation loss and prevent overfitting. To ensure that each class obtains an equal number of images and keep the model from becoming biased towards any one class, the dataset was balanced using a technique called resampling. Class weights were also used to address the problem of imbalance; they helped to give more importance to underrepresented classes.

In the listing of various road damage types, a commonly used classification was used, which was proposed by [12], and the prevalent road issues were characterized by eight types of road damage, namely D00, D01, D10, D20, D40, D43, and D44. For this study, the dataset is refined by removing the labels for two lesser-relevant categories, namely D10 and D11. Table 1 gives a broader definition of road damage types to be used together with their class names.

Table 1.

Road damage dataset together with their respective class names.

Adequate training data for each damage class was required for the deep learning models. Nevertheless, some of the damage types shown in Table 1 are not commonly observed when gathering damage data from the road. Hence, collecting enough samples for these classes was challenging. The “alligator crack” class is a series of interconnected cracks that show a road surface that looks like the back of an alligator. In this study, it represents several crack damage types as defined in Table 1, which includes longitudinal, transverse, linear, and alligator cracks. The “pothole” refers to holes or depressions in the road surface that are shaped like a bowl and range in size. They can have edges that are sharp and may have vertical sides that might be found at the top of the hole.

5.2. YOLO Training and Testing Settings

All experiments were conducted in Python 3.10 using Ultralytics YOLOv8s implementation, built on PyTorch 2.1.0. Training was performed on Google Colab (Tesla T4 GPU, 16 GB VRAM) and on a local workstation (Intel® Xeon® E5-1650 v3 CPU @ 3.50 GHz, 32 GB RAM, Windows 10 Enterprise). The RDD2024_SA dataset, comprising 489 labeled road images, was partitioned into 80% training (391 images), 10% validation (49 images), and 10% testing (49 images). Similarly, the RDD2022_India dataset, containing 4205 annotated road images, was split into 80% training (3364 images), 10% validation (421 images), and 10% testing (420 images). This ratio follows common practice for compact computer-vision datasets to ensure sufficient training diversity while reserving distinct subsets for hyperparameter tuning and unbiased evaluation. The same proportions were maintained across all experimental scenarios to ensure consistent comparison of intra- and inter-domain performance. The amount of data used for training, validation, and testing is summarized in Table 2. Table 3 presents a list of the hyperparameters that were used in the preprocessing of the YOLOv8 model.

Table 2.

Proportioning of the RDD2024_SA and RDD2022_India datasets among training, validation, and testing.

Table 3.

Hyperparameters for the YOLOv8 used in this study.

For network preprocessing and augmentation, an image input size of 640 × 640 pixels was adopted, with a random horizontal flip probability of 0.5, contrast variation to ±20%, and saturation jitter of ±10%. These parameters, although computationally efficient, do not produce high-definition inputs capable of clearly distinguishing fine or closely matching defect features. This limitation likely contributed to part of the observed error and constrained the generalization ability of the YOLOv8s model in this study.

The composite loss function (box + objectness + class) of YOLOv8 was used for optimization. Model performance on the validation split was monitored using mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5–0.95 across epochs, and the held-out test set was evaluated with a confidence threshold = 0.25 and NMS IoU = 0.45. Precision, recall, and mAP were subsequently reported.

Transfer learning protocol (for domain adaptation): the model was initialized from the RDD2022_India-trained checkpoint, with the early backbone frozen while fine-tuning the detection head using a small South African subset (≤20%) under class-balanced sampling and a reduced learning rate. This is expected to mitigate the Scenario-2/4 performance gap by aligning low-level textures and annotation style between the two domains.

6. Results

6.1. Experimental Scenarios for Model Evaluation

To evaluate the robustness and adaptability of the YOLOv8s model for road damage detection, five experimental scenarios were considered, each employing different combinations of training and testing datasets. These scenarios aim to assess the impact of dataset characteristics, class structuring, and domain adaptation strategies, particularly transfer learning, and how they affect model generalization and detection performance across regions.

6.1.1. Scenario 1: Use of RDD2024_SA Dataset Only

In this configuration, the YOLOv8s model was trained, validated, and tested exclusively on the custom dataset captured from roads in Pretoria and Johannesburg. This scenario establishes a baseline performance by evaluating the model within the same data domain it was trained on. Table 4 is the result of test Scenario 1, and Figure 6 shows a sample of the model predictions from Scenario 1.

Table 4.

Performance metrics (Precision, Recall, mAP@0.5) for Scenario 1 (in domain evaluation using the RDD2024_SA dataset).

Figure 6.

Sample detection outputs of the YOLOv8s model on the RDD2024_SA test set showing accurate identification of multiple defect types.

6.1.2. Scenario 2: Use of RDD2022_India for Training and Validation and RDD2024_SA for Testing

Here, the model was trained and validated using the RDD2022_India dataset, while testing was performed on the RDD2024_SA dataset. This setup assesses the model’s ability to generalize learned features from a large, diverse dataset to a distinct, localized dataset acquired in a different region using smartphone-based imaging. Table 5 is the training result for Scenario 2. According to the obtained results, the model performs fairly well in the detection of white line blur but fails to detect alligator cracks. This is due to the ‘white line blur’ consistent, high-contrast geometry tied to lane markings. In contrast, ‘alligator cracks’ are multi-scale, lower-contrast, and annotated with broader stylistic variation across datasets, reducing cross-domain recall. The detection of the other types of road damage that are studied in this research falls between these two extremes.

Table 5.

Performance metrics (Precision, Recall, mAP@0.5) for Scenario 2 (cross-domain evaluation (RDD2022_India-RDD2024_SA)).

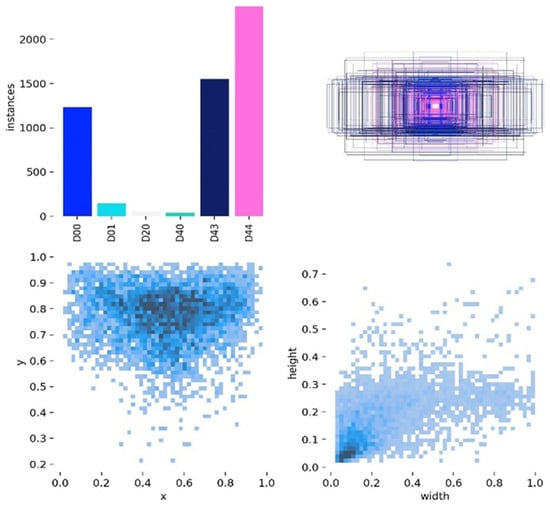

6.1.3. Scenario 3: Use of RDD2022_India Only

In this scenario, the YOLOv8s model network was trained, validated, and tested entirely on the RDD2022_India dataset. It serves as a comparative benchmark, evaluating model performance using a well-established and consistently annotated dataset covering varied Indian road environments. Table 6 is the result of the training outcome for Scenario 3, while Figure 7 shows the six-class configuration exhibited substantial annotation imbalance and limited geometric variation, particularly for D01 and D20. This concentration of small, centrally located bounding boxes constrained the network’s ability to learn distinctive features across classes. Reducing the taxonomy to four dominant categories, therefore, improved feature diversity and training stability, leading to the higher mAP, precision, and recall values reported later.

Table 6.

Performance metrics (Precision, Recall, mAP@0.5) for Scenario 3 (intra-dataset evaluation using RDD2022_India).

Figure 7.

Label instances for the result of Scenario 3.

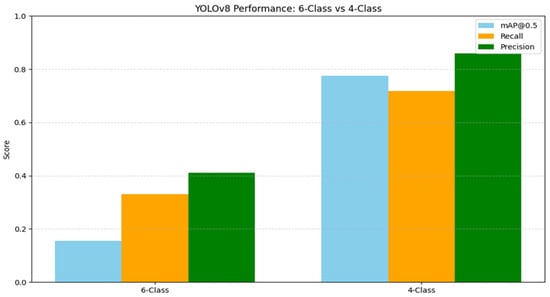

We retrained the YOLOv8s model for Scenario 3 using a refined label set that only included four classes (D00, D20, D40, and D44), eliminating D01 and D43 because they had sparse annotations and worse detection consistency, to investigate whether streamlining the label space could increase model efficiency. The outcome demonstrated a notable improvement in performance: the model’s average mAP@0.5 was 0.776, as opposed to 0.156 from the 6-class version of Scenario 3, and all four retained classes showed notable increases in precision and recall. Figure 8 shows prediction images for this scenario.

Figure 8.

Prediction results of different distress for Scenario 3.

YOLO’s discriminative power may be improved by eliminating low-frequency or poorly annotated classes, according to this targeted reduction, particularly when applied to unbalanced or constrained datasets. The full metrics for each class are shown in Table 7, and the improvement in mAP, precision, and recall in comparison to the 6-class baseline is shown in Figure 9.

Table 7.

Performance metrics (Precision, Recall, mAP@0.5) for Scenario 3 (reduced 4-class configuration (D00, D20, D40, D44)).

Figure 9.

Comparison of YOLOv8s model performance before and after class reduction.

6.1.4. Scenario 4: Use of RDD2024_SA for Training and Validation, and RDD2022_India for Testing

The final scenario involves training and validating the model on the RDD2024_SA (Pretoria/Johannesburg) dataset, while testing it on the RDD2022_India dataset. This test scenario examines the robustness of a model after being trained and validated with data obtained from a small section of the road network in one region, but tested on data from a section of the road network in another region. It has been mentioned in a previous section that although the Indian data were obtained from a broader and more diverse section of the road network, there were fewer instances of the transverse/linear cracks (D01), alligator cracks (D20), and pothole, separation, and rutting defects. Even more challenging was the fact that D01 and D43 contained sparse annotations and exhibited worse detection consistency. These challenges made the testing of the model’s accuracy on the RDD2022_India dataset, solely based on the RDD2024_SA dataset, intractable.

6.2. Model Performance Comparison and Evaluation on Each Scenario

Table 8 summarizes the model’s performance across the scenarios using standard metrics such as Precision, Recall, and mAP@0.5. Scenarios 1–4 correspond to the original domain-transfer experiments, while Scenario 5 represents the transfer-learning configuration in which the RDD2022_India-trained model was fine-tuned using 20% of RDD2024_SA data, yielding substantial performance recovery. The average performance is calculated as the mean over the damage classes considered. The results highlight how dataset selection influences the model’s predictive capabilities on unseen road images.

Table 8.

Performance of YOLOv8s across different training and testing scenarios.

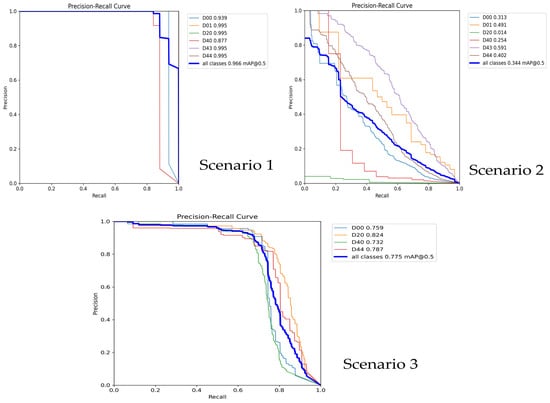

The performance across the first three scenarios is further illustrated using Precision–Recall curves (Figure 10), which highlight the trade-off between recall and precision per class.

Figure 10.

Precision–Recall (P-R) curves at IoU = 0.5 showing per-class performance of the YOLOv8s model across Scenarios 1–3. Axes range from 0 to 1.0.

As shown in Figure 10, Scenario 1 significantly outperformed all other scenarios, with precision, recall, and mAP@0.5 values close to 0.97, reflecting the strong domain alignment between the training and testing data. Scenario 2 exhibited moderate to weak performance, particularly in terms of mAP@0.5. Scenario 3 recorded a very good performance after the reduction in the number of classes from six to four. Scenario 4 recorded poor performance across all metrics, which required further work on data size and the quality of the training data labeling, especially when using small data.

Scenario 5: Transfer Learning (RDD2022_India to SA, 20% SA Data Refinement)

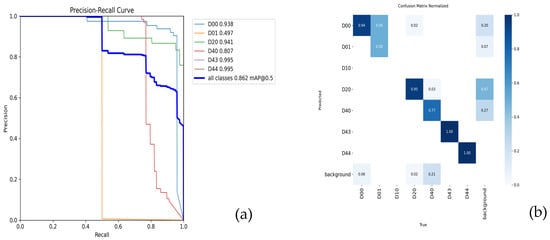

Building upon the cross-domain results in Scenario 2, a transfer-learning experiment was conducted to evaluate whether fine-tuning could mitigate domain-shift effects between the Indian and South-African datasets. The YOLOv8s model pretrained on RDD2022_India (four classes) was fine-tuned on a 20% subset of RDD2024_SA (seven damage types) for 40 epochs at a learning rate of 0.0005, using a batch size of 16, input resolution 640 × 640, and partial layer freezing (first 10 layers).

The fine-tuned model reached mAP@0.5 = 0.862, precision = 1.00, recall = 0.88, and F1 = 0.88 (at confidence = 0.503), representing a major improvement over the direct cross-domain baseline in Scenario 2 (mAP = 0.32). The precision–recall curves (Figure 11a) demonstrate stable class-level behavior, with consistently high reliability for D20, D40, D43, and D44. The normalized confusion matrix (Figure 11b) further confirms reduced misclassification and improved inter-class separability after fine-tuning. However, D01 remains under-detected, which aligns with its sparse representation in both the RDD2022_India and RDD2024_SA datasets.

Figure 11.

Scenario 5: transfer-learning performance after fine-tuning the YOLOv8s model pretrained on RDD2022_India using 20% of RDD2024_SA data. (a) Precision–Recall curve showing mAP@0.5 = 0.862 and balanced performance across classes. (b) Normalized confusion matrix illustrating improved inter-class separability compared with the cross-domain baseline of Scenario 2 in Figure 10.

These results confirm that transfer learning with minimal local data can recover model robustness across domains, reducing the dependence on large, fully annotated datasets. This lightweight adaptation strategy offers a practical engineering pathway for municipalities and transport agencies to deploy pretrained road-defect detectors under new environmental and lighting conditions.

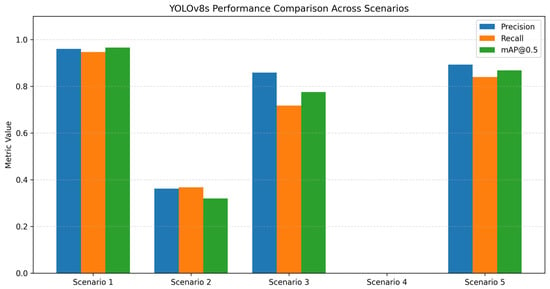

Figure 12 compares the overall performance of YOLOv8s across the five experimental scenarios. Scenario 1 produced the highest accuracy (mAP@0.5 = 0.966), confirming that models perform best when trained and tested on the same domain. Scenario 2 and Scenario 4 show substantial performance degradation, indicating weak cross-regional generalization. Scenario 3 demonstrates that reducing the number of damage classes improves feature separability and detection consistency. Scenario 5 shows that transfer learning, using only 20% of the South African dataset, significantly boosts performance (mAP@0.5 = 0.868), validating the effectiveness of domain adaptation.

Figure 12.

Scenario-wise comparison of mAP@0.5 for YOLOv8s across five road damage classes.

7. Discussion

Scenario 1: The object detection model’s performance evaluation across six road damage types, namely, the longitudinal cracks (D00), transverse/linear cracks (D01), alligator cracks (D20), pothole, separation and rutting defects (D40), white line blur (D43), and crosswalk blur (D44), shows consistently high accuracy, with the mean Average Precision (mAP) at an IoU threshold of 0.5 approaching perfect scores for most classes with precision and recall values significantly exceeding 0.90. Interestingly, the model demonstrated a remarkable capacity to accurately recognize all real cases of transverse/linear cracks, alligator cracks, white line blur, and crosswalk blur, achieving perfect recall of 1.0 for five of the six damage types. Pothole, separation and rutting, and longitudinal cracks resulted in the highest precision equal to 1.0 and 0.998, respectively, with the fewest false positives. For four damage types (transverse/linear cracks, alligator cracks, white line blur, and crosswalk blur), the mAP values, with both false positives and false negatives, represent the model’s overall classification performance exceeding 0.99, showing almost faultless localization and classification accuracy.

Although the model’s precision was excellent, it had a comparatively poor recall for pothole, with separation and rutting equal to 0.742, suggesting that it missed several cases of this damage type despite its excellent overall performance. This challenge implies that even if the model has a high degree of confidence in detecting potholes, separation, and rutting, it might need more training data or architectural adjustments to more effectively generalize all instances of this distress class. In addition, longitudinal cracks showed a somewhat poorer recall value of 0.938 as compared to their extremely high precision, suggesting that recall tuning is also necessary. However, the model shows strong and consistent road surface distress identification capabilities, especially for transverse/linear cracks, alligator cracks, white line blur, and crosswalk blur, which makes it feasible for practical implementation in pavement condition monitoring systems.

Scenario 2: Using the publicly accessible RDD2022_India dataset for training and the locally measured RDD2024_SA dataset from Pretoria and Johannesburg areas for testing, Scenario 2 assesses the performance of the YOLOv8s model using big data acquired in one region for training and validation, and thereafter applying the trained model for defect identification over small data from another region. Significant differences in detection performance between the damage classes were tabulated in Table 5. Some of the distress classes, such as alligator cracks, failed to register any precision or recall at all, whereas white line blur and crosswalk blur had the greatest mAPs, at 0.605 and 0.408, respectively. Common longitudinal and transverse cracks were not well detected, as evidenced by the comparatively low mAP scores for D00 and D01 equal to 0.283 and 0.293, respectively. This is probably because different datasets have different image resolutions, lighting circumstances, and annotation styles. More unique features or comparable representations in both datasets might have benefited the best-performing distress classes, such as white line blur and crosswalk blur. All things considered, Scenario 2 draws attention to a key issue in this study concerning generalization: models developed using big data acquired in one region might not yield good results when applied to small data for damage identification in another region without specific modification or adjustment to fit certain conditions in the application region.

Scenario 3: Scenario 3 is an intra-dataset evaluation where the RDD2022_India dataset is the only dataset used to train and test the model. Unlike earlier experiments involving six classes, this configuration focuses on four dominant damage categories, D00, D20, D40, and D44, based on clearer class representation and annotation quality. The model performs better in this refined setup, achieving mAP@0.5 = 0.7755, Precision = 0.859, and Recall = 0.718 (Table 8), a substantial improvement over the mAP of 0.156 obtained when all six classes were used (Table 6).

The performance breakdown reveals mAP values of 0.759 for longitudinal cracks, 0.824 for alligator cracks, 0.732 for pothole/separation/rutting, and 0.787 for crosswalk blur. These results indicate more stable and reliable predictions across the retained classes. Removing D01 and D43 helped reduce annotation inconsistencies and intra-class variability that previously introduced noise during training. By simplifying the class taxonomy, the model was able to focus on clearer visual patterns and achieve more stable convergence.

These findings emphasize that refining class definitions and limiting training to well-annotated, consistently labeled categories can improve model generalizability in single-domain learning. Thoughtful class curation, therefore, plays a crucial role in enhancing feature learning and ensuring reliable performance in practical road-damage detection systems.

Scenario 4: Scenario 4, which involved training and validation exclusively on the RDD2024_SA dataset and testing on the RDD2022_India dataset, resulted in complete failure across all damage classes, recording negative to zero values for precision, recall, and mAP. This outcome is indicative of a significant domain shift between the two datasets. Key differences, such as road surface textures, damage patterns, lighting conditions, image resolution, and annotation styles, likely hindered the model’s ability to generalize learned features from the small data to the big data environment. Another contributing factor is the limited scale and variability of the small data, which may not have captured a sufficient range of road damage scenarios to train a robust and generalizable feature extractor. The model may have overfitted to specific characteristics unique to the South African context, resulting in an inability to detect visually and structurally different damage types present in RDD2022_India. This scenario strongly reinforces the importance of training on diverse, representative, and sufficiently large datasets when building deep learning models for global or cross-regional deployment. This scenario strongly reinforces the importance of training on diverse, representative, and sufficiently large datasets when building deep learning models for global or cross-regional deployment.

Scenario 5: The transfer-learning experiment applied fine-tuning to the YOLOv8s model originally trained on the RDD2022_India dataset using a 20% subset of RDD2024_SA images. This adaptation led to a substantial recovery in performance, with mAP@0.5 = 0.862, precision = 1.00, and recall = 0.88, compared with the direct cross-domain baseline of Scenario 2 (mAP = 0.32). The precision–recall curves (Figure 11a) demonstrate stable class-level behavior, with consistently high reliability for D20, D40, D43, and D44. The normalized confusion matrix (Figure 11b) further confirms reduced misclassification and improved inter-class separability after fine-tuning. However, D01 remains under-detected, which aligns with its sparse representation in both the Indian and South-African datasets. These results verify that even limited exposure to localized data allows the pretrained model to adjust its learned feature space, thereby closing a large portion of the performance gap created by domain shift.

From an engineering perspective, this outcome demonstrates the practical value of lightweight model adaptation for real-world deployment. Rather than retraining large models from scratch, municipalities and contractors can reuse pretrained networks from related environments and fine-tune them with a small, representative sample of local road imagery. This approach minimizes annotation cost, reduces computational demand, and ensures rapid scaling of AI-based pavement-inspection systems to new regions with distinct lighting, pavement materials, or camera configurations. The success of Scenario 5, therefore, highlights transfer learning as a sustainable and resource-efficient pathway for achieving robust cross-regional road-damage detection.

Collectively, the outcomes of Scenarios 1–5 demonstrate that dataset domain alignment, class balance, and moderate fine-tuning are decisive factors for achieving stable and transferable road-defect detection performance across heterogeneous environments.

From an engineering standpoint, these results emphasize that the deployment of road-defect detection systems must account for domain-specific conditions and data characteristics. Localized training delivers high accuracy within the region of acquisition, but performance can degrade substantially when applied to different environments without adaptation. In practice, modest fine-tuning using a small subset of local data, improved class balancing, and illumination normalization can significantly enhance reliability across diverse road and climatic conditions. These insights provide actionable guidance for transportation engineers and municipal maintenance teams integrating AI-based pavement inspection into real-world operations.

Recent studies using earlier YOLO frameworks have demonstrated the potential of deep learning for automatic pavement-distress detection. For instance, Jiang et al. [39] RDD-YOLOv5 introduced a transformer-enhanced architecture with Gaussian Error Linear Units, achieving a mAP of 91.48%, about 2.5% higher than the baseline YOLOv5 in UAV-based inspection tasks. Similarly, Pham et al. [40], using YOLOv7 augmented with coordinate attention, label smoothing, and ensemble techniques, obtained F1-scores of 81.7% (U.S. subset) and 74.1% (overall dataset) using Google Street View imagery. Earlier, Sarmiento [41] utilized YOLOv4-based detection and segmentation work on Philippine road images, which also showed that even small, manually collected datasets can yield effective distress identification.

In comparison, the present YOLOv8s-based study achieved mAP@0.5 = 0.95 in the in-domain (RDD2024_SA) scenario and ≈ 0.78 after class reduction on RDD2022_India, performing within or above the ranges reported for earlier YOLO versions. More importantly, the Scenario 5 transfer-learning experiment demonstrated that fine-tuning the India-trained model using only 20% of the South-African dataset restored cross-domain performance to mAP@0.5 = 0.862, substantially higher than the direct cross-domain baseline (mAP = 0.32).

Unlike prior studies that focus primarily on architectural improvements, this work provides a cross-domain and transferability analysis, showing how dataset diversity, annotation style, class structuring, and limited fine-tuning govern generalization across regions. Hence, the study complements architecture-oriented research by offering an evidence-based understanding of domain alignment requirements for real-world, AI-enabled road-maintenance systems.

8. Conclusions

Comparative results across all five scenarios clearly demonstrate the importance of dataset–domain alignment, class structuring, and limited fine-tuning in determining the performance of deep-learning models for road-damage detection. With mAP@0.5 values ranging from 0.877 to 0.995 across all damage classes, Scenario 1, in which the YOLOv8s model was trained, validated, and tested solely on the Pretoria/Johannesburg (RDD2024_SA) dataset, achieved excellent accuracy. This confirms that context-specific localized datasets provide strong feature representations that support reliable detection of road defects. Conversely, Scenarios 2 and 4, which involved cross-domain testing, revealed severe degradation or complete detection failure, highlighting the difficulty of applying models trained in one region to another without adaptation.

Observed cross-domain degradation is primarily linked to variations in illumination and weather conditions, camera viewpoint, road pavement materials, annotation style, and inter-dataset class-distribution differences, all of which affect feature transferability. Scenario 3, which reduced class complexity from six to four dominant categories (D00, D20, D40, and D44), achieved improved performance (mAP@0.5 = 0.776, precision = 0.858, recall = 0.718), demonstrating that curated and consistent class definitions enhance model stability and generalization. Scenario 5, a transfer-learning configuration in which the India-trained model was fine-tuned on only 20% of the South-African dataset, achieved mAP@0.5 = 0.862, precision = 1.00, and recall = 0.88. This significant recovery underscores the engineering practicality of lightweight model adaptation for bridging domain gaps.

Overall, the findings establish that domain-aligned data preparation, targeted fine-tuning, and balanced class representation are decisive for developing robust, transferable, and resource-efficient AI systems for pavement-condition monitoring and sustainable road-maintenance management. Future work should incorporate interpretability methods such as class-activation mapping and feature-attribution analysis to ensure that YOLO-based road damage detectors operate transparently and provide engineering practitioners with insight into the visual cues and decision patterns that underlie each prediction.

Author Contributions

T.B.: Conceptualization; Methodology; Investigation; Data Curation; Software; Validation; Writing-Original Draft Preparation; Formal Analysis; Visualization; Project Administration. H.M.N.: Project Administration; Supervision; Resources; Writing—Review and Editing; Validation. T.P.: Resources; Project Administration; Writing—Review and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from the authors; the data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Tolulope Babawarun upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their heartfelt gratitude to our institution, the University of South Africa (UNISA), for their support and contribution to the successful completion of this research. The resources provided by UNISA made this research feasible. Thanks to the team at Language Editing Services at UNISA (Vergie Malvin) for assisting in the editing of the manuscript. Special thanks go to the team at Roadroid for providing technical support and expertise regarding the use and availability of the smartphone application, which was instrumental to this study. We also acknowledge the South African National Road Agency Ltd. (SANRAL) for granting access to the city’s road networks and providing valuable insights into the province’s road maintenance strategies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| ARD | Automatic Road Distress |

| CARAFE | Content-Aware ReAssembly of FEatures |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DA | Data Augmentation |

| FC | Fully Connected |

| fps | Frames Per Second |

| GB | Gigabyte |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| LBP | Local Binary Patterns |

| LS-SVM | Least Squares Support Vector Machine |

| mAP | Mean Average Precision |

| RDD | Road Damage Detection |

| RTRRMS | Response-type Road Roughness Measuring System |

| SimSPPF | Simplified Spatial Pyramid Pooling-Fast |

| UN-SDG | United Nations Sustainable Development Goal |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

References

- AASHTO. Rough Roads Ahead: Fix Them Now or Pay for It Later; American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, C.; Georgieva, K.; Kasireddy, V.; Akinci, B.; Fieguth, P. A Review on Computer Vision Based Defect Detection and Condition Assessment of Concrete and Asphalt Civil Infrastructure. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2015, 29, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anish, B.K.; Mahato, A.; Thapa, S.; Rai, A.; Devkota, N. Achieving Nepal’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by Effective Compliance of Corporate Governance. Quest J. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2019, 1, 50–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, Y.T.; Thotawaththa, T.A.I.; Wijayasari, A. Measuring Road Roughness through Crowdsourcing While Minimizing the Conditional Effects. Int. J. Intell. Transp. Syst. Res. 2022, 20, 581–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, A.; Nikam, D.; Balachandran, V.N.; Guo, L.; Wang, R.; Hu, L.; Comert, G.; Jia, Y. Cloud-Based Collaborative Road-Damage Monitoring with Deep Learning and Smartphones. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.; O’Brien, E.J.; Li, Y.Y.; Cashell, K. The Use of Vehicle Acceleration Measurements to Estimate Road Roughness. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2008, 46, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, R.B.; Miller, R.W.; Kulkarni, R.B. Pavement Management Systems Past, Present, and Future. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2003, 1853, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Ortiz, S.; Pascual-Muñoz, P.; Castro-Fresno, D. Machine Learning Algorithms for Monitoring Pavement Performance. Autom. Constr. 2022, 139, 104309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnebele, E.; Tanyu, B.F.; Cervone, G.; Waters, N. Review of Remote Sensing Methodologies for Pavement Management and Assessment. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2015, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrieri, M.; Parla, G.; Khanmohamadi, M.; Neduzha, L. Asphalt Pavement Damage Detection through Deep Learning Technique and Cost-Effective Equipment: A Case Study in Urban Roads Crossed by Tramway Lines. Infrastructures 2024, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfarrarjeh, A.; Trivedi, D.; Ho Kim, S.; Shahabi, C. A Deep Learning Approach for Road Damage Detection from Smartphone Images. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Seattle, WA, USA, 10–13 December 2018; pp. 5201–5205. [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, H.; Sekimoto, Y.; Seto, T.; Kashiyama, T.; Omata, H. Road Damage Detection Using Deep Neural Networks with Images Captured Through a Smartphone. Comput. Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2018, 33, 1127–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benallal, M.A.; Tayeb, M.S. An Image-Based Convolutional Neural Network System for Road Defects Detection. IAES Int. J. Artif. Intell. 2023, 12, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertozzi, M.; Broggi, A. GOLD: A Parallel Real-Time Stereo Vision System for Generic Obstacle and Lane Detection. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 1998, 7, 62–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caltagirone, L.; Bellone, M.; Svensson, L.; Wahde, M. LIDAR–Camera Fusion for Road Detection Using Fully Convolutional Neural Networks. Rob. Auton. Syst. 2019, 111, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, N.D. An Artificial Intelligence Method for Asphalt Pavement Pothole Detection Using Least Squares Support Vector Machine and Neural Network with Steerable Filter-Based Feature Extraction. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2018, 2018, 7419058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, F.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, Y.J. Road crack detection using deep convolutional neural network. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 25–28 September 2016; pp. 3708–3712. [Google Scholar]

- Asian, O.D.; Gultepe, E.; Ramaji, I.J.; Kermanshachi, S. Using Artifical Intelligence for Automating Pavement Condition Assessment. In International Conference on Smart Infrastructure and Construction 2019, ICSIC 2019: Driving Data-Informed Decision-Making; ICE Publishing: London, UK, 2019; pp. 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arman, M.S.; Hasan, M.M.; Sadia, F.; Shakir, A.K.; Sarker, K.; Himu, F.A. Detection and Classification of Road Damage Using R-CNN and Faster R-CNN: A Deep Learning Approach. In Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social-Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering, LNICST; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 325, pp. 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, V.; Pham, C.; Dang, T. Road Damage Detection and Classification with Detectron2 and Faster R-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Big Data, Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–13 December 2020; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 5592–5601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Ruiz, G.; Angulo-Murillo, A.A.; Ochoa-Zezzatti, A.; Aguilar-Lobo, L.M.; Vega-Fernández, J.A.; Natraj, S. An Asphalt Damage Dataset and Detection System Based on Retinanet for Road Conditions Assessment. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Nateghinia, E.; Miranda-Moreno, L.F.; Sun, L. Pavement Distress Detection Using Convolutional Neural Network (CNN): A Case Study in Montreal, Canada. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.W.; Chung, K. Pothole Classification Model Using Edge Detection in Road Image. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.S.; Tran, V.T.; Lee, D.E. Application of Various Yolo Models for Computer Vision-Based Real-Time Pothole Detection. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Yang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Qu, F.; Punetha, P.; Li, W.; Li, N. Enhancing Autonomous Pavement Crack Detection: Optimizing YOLOv5s Algorithm with Advanced Deep Learning Techniques. Measurement 2025, 240, 115603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, J.; Song, W.; Zhuang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Ye, X.; Shi, G.; Zhang, H. ARDs-YOLO: Intelligent Detection of Asphalt Road Damages and Evaluation of Pavement Condition in Complex Scenarios. Measurement 2025, 242, 115946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Xu, L.; Yu, Z.; Shi, Y.; Mu, C.; Xu, M. Deep-IRTarget: An Automatic Target Detector in Infrared Imagery Using Dual-Domain Feature Extraction and Allocation. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2022, 24, 1735–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Li, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Xu, L.; Zhang, B.; Wang, B. Differential Feature Awareness Network Within Antagonistic Learning for Infrared-Visible Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 6735–6748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwangwa, H.M.; Heyns, P.S.; Breytenbach, H.G.A.; Els, P.S. Reconstruction of Road Defects and Road Roughness Classification Using Artificial Neural Networks Simulation and Vehicle Dynamic Responses: Application to Experimental Data. J. Terramech. 2014, 53, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harikrishnan, P.M.; Gopi, V.P. Vehicle Vibration Signal Processing for Road Surface Monitoring. IEEE Sens. J. 2017, 17, 5192–5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwangwa, H.M. Calculation of Road Profiles by Reversing the Solution of the Vertical Ride Dynamics Forward Problem. Cogent Eng. 2020, 7, 1833819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, A.; Pan, G. A Maximum-Entropy-Attention-Based Convolutional Neural Network for Image Perception. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 35, 8647–8655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, H.; Ye, Y.; Na, X.; Hu, H.; Wang, G.; Wu, C.; Hu, S. Sustainable Road Pothole Detection_ A Crowdsourcing Based Multi-Sensors Fusion Approach. Sustainabilty 2023, 15, 6610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouch, A.; Koubaa, A.; Abbes, T.; Ammar, A. RoadSense: Smartphone Application to Estimate Road Conditions Using Accelerometer and Gyroscope. IEEE Sens. J. 2017, 17, 4231–4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, J.; Kobana, Y.; Isoyama, N.; Tobe, Y.; Lopez, G. YKOB: Participatory Sensing-Based Road Condition Monitoring Using Smartphones Worn by Cyclist. Electron. Commun. Jpn. 2018, 101, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertz, C.; Varadharajan, S.; Jose, S.; Sharma, K.; Wander, L.; Wang, J. City-Wide Road Distress Monitoring with Smartphones. 2014, pp. 1–9. Available online: https://www.ri.cmu.edu/pub_files/2014/9/road_monitor_mertz_final.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Timilsina, A. YOLOv8 Architecture Explained. 2024. Available online: https://abintimilsina.medium.com/yolov8-architecture-explained-a5e90a560ce5 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Jiang, Y.; Yan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, K.; Liu, R.; Lin, C. RDD-YOLOv5: Road Defect Detection Algorithm with Self-Attention Based on Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Inspection. Sensors 2023, 23, 8241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, V.; Nguyen, D.; Donan, C. Road Damage Detection and Classification with YOLOv7. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Big Data, Osaka, Japan, 17–20 December 2022; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 6416–6423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, J.-A. Pavement Distress Detection and Segmentation Using YOLOv4 and DeepLabv3 on Pavements in the Philippines. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.06467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).