Exploring Psychosocial Determinants of Young Adults E-Scooter Speeding: A TPB-Aligned SEM Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

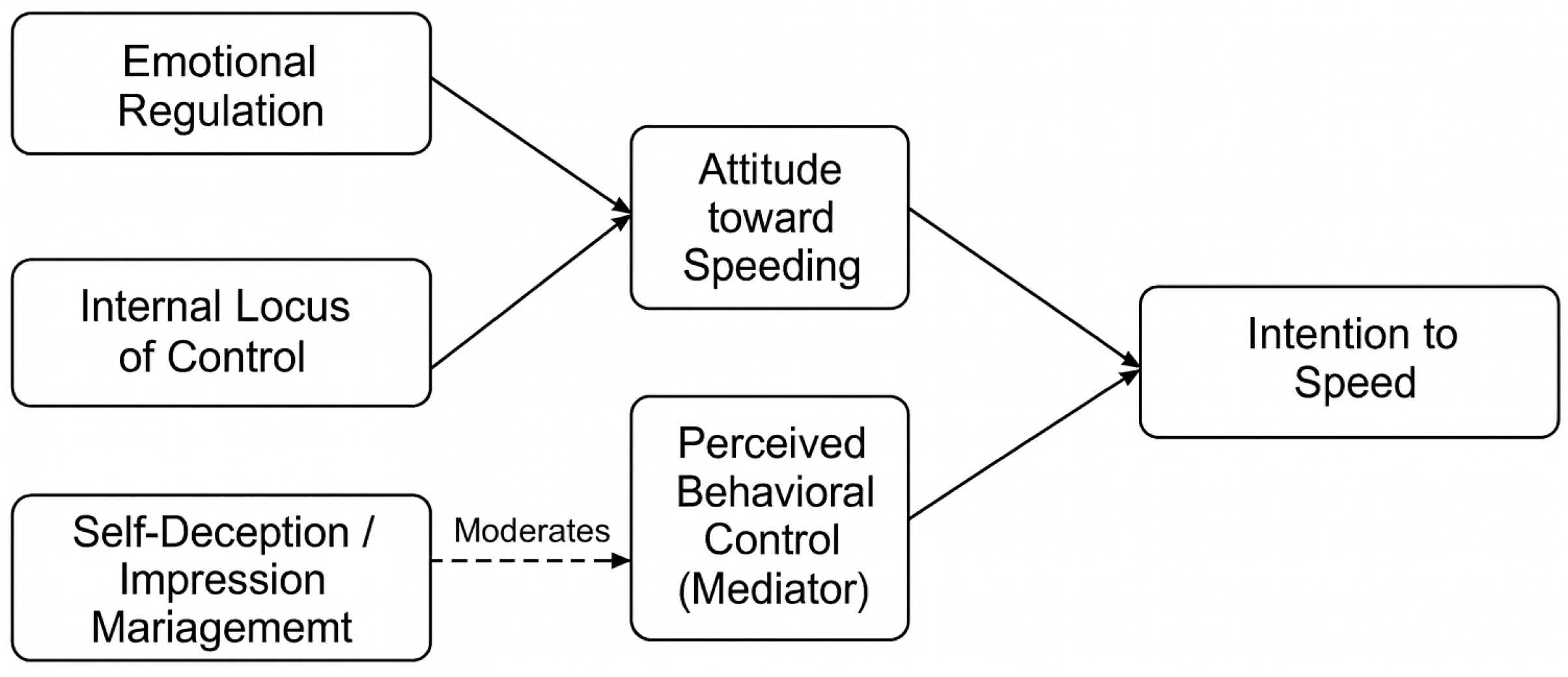

2. Methods

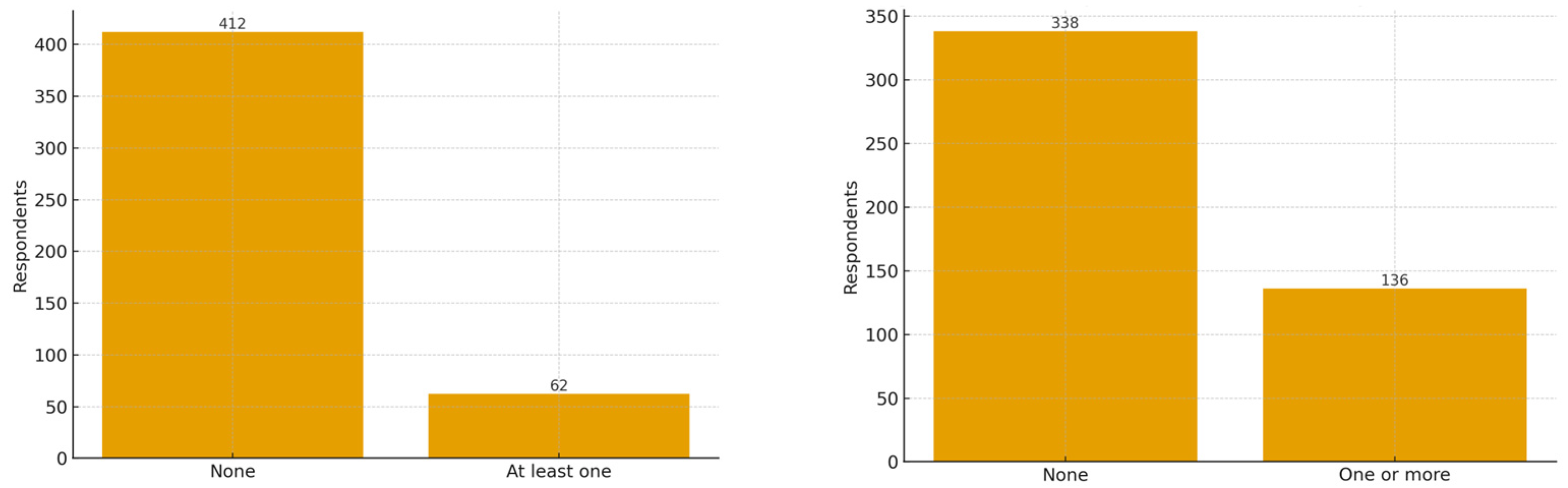

2.1. Sample and Target Population

2.2. Questionnaire Design

3. Data Analysis and Statistical Modelling

3.1. Survey Data Analysis

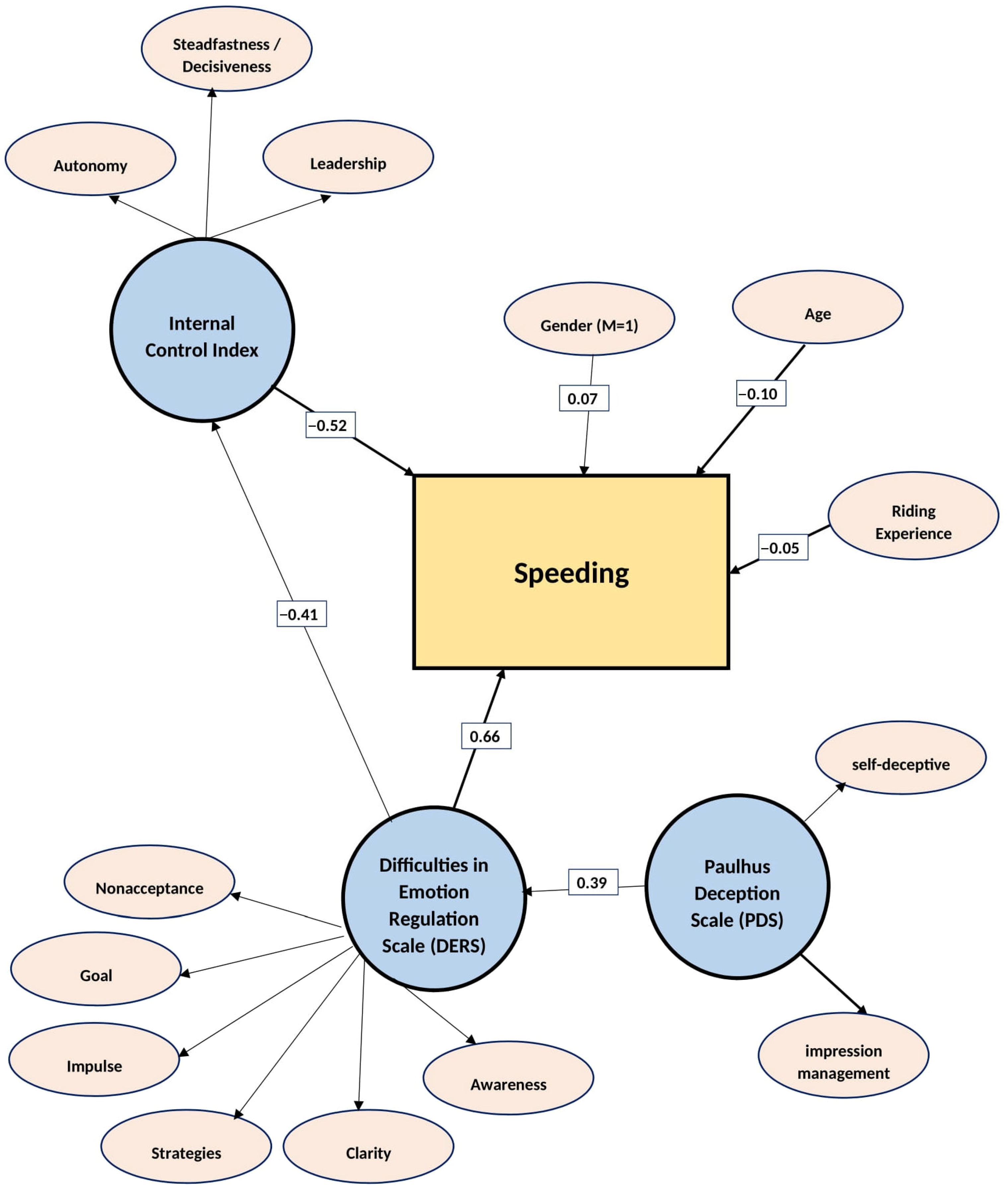

3.2. Structural Equation Modeling

3.2.1. Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS)

3.2.2. Paulhus Deception Scales

3.2.3. Internal Control Index

3.3. Latent Variables and Speeding Behavior

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix

| Question | Component | Factor Loading | t-Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25. When I’m upset, I feel ashamed of myself for feeling that way. | Nonacceptance of emotional responses | 0.58 | 2.75 |

| 15. When I’m upset, I become embarrassed for feeling that way. | 0.61 | 5.62 | |

| 14. When I’m upset, I become angry with myself for feeling that way. | 0.52 | 4.21 | |

| 33. When I’m upset, I become irritated with myself for feeling that way. | 0.42 | 6.25 | |

| 27. When I’m upset, I feel like I am weak. | 0.44 | 4.19 | |

| 29. When I’m upset, I feel guilty for feeling that way. | 0.73 | 3.40 | |

| 22. When I’m upset, I have difficulty focusing on other things. | Difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior | 0.69 | 3.65 |

| 16. When I’m upset, I have difficulty getting work done. | 0.72 | 4.12 | |

| 18. When I’m upset, I have difficulty thinking about anything else. | 0.75 | 3.25 | |

| 24. When I’m upset, I can still get things done. | 0.53 | 2.78 | |

| 30. When I’m upset, I have difficulty concentrating. | 0.78 | 5.45 | |

| 13. When I’m upset, I lose control over my behaviors. | Impulse control difficulties | 0.69 | 7.42 |

| 31. When I’m upset, I have difficulty controlling my behaviors. | 0.65 | 4.16 | |

| 17. When I’m upset, I become out of control. | 0.56 | 5.29 | |

| 23. When I’m upset, I feel out of control. | 0.57 | 4.28 | |

| 2. I experience my emotions as overwhelming and out of control. | 0.43 | 3.75 | |

| 28. When I’m upset, I feel like I can remain in control of my behaviors. | 0.45 | 4.45 | |

| 7. I am attentive to my feelings. | Lack of emotional awareness | 0.55 | 3.16 |

| 3. I pay attention to how I feel. | 0.57 | 2.99 | |

| 12. When I’m upset, I acknowledge my emotions. | 0.63 | 4.06 | |

| 21. When I’m upset, I believe that my feelings are valid and important. | 0.52 | 3.28 | |

| 9. I care about what I am feeling. | 0.46 | 4.16 | |

| 36. When I’m upset, I take time to figure out what I’m really feeling. | 0.50 | 5.12 | |

| 20. When I’m upset, I believe that I’ll end up feeling very depressed. | Limited access to emotion regulation strategies | 0.72 | 4.10 |

| 19. When I’m upset, I believe that I will remain that way for a long time. | 0.65 | 2.10 | |

| 4. When I’m upset, I believe that wallowing in it is all I can do. | 0.64 | 3.10 | |

| 11. When I’m upset, it takes me a long time to feel better. | 0.52 | 4.54 | |

| 32. When I’m upset, I believe that there is nothing I can do to make myself feel better. | 0.50 | 3.41 | |

| 26. When I’m upset, I know that I can find a way to eventually feel better. | 0.50 | 4.42 | |

| 35. When I’m upset, my emotions feel overwhelming. | 0.46 | 5.53 | |

| 34. When I’m upset, I start to feel very bad about myself. | 0.43 | 3.32 | |

| 6. I have difficulty making sense out of my feelings. | Lack of emotional clarity | 0.55 | 3.13 |

| 5. I have no idea how I am feeling. | 0.59 | 5.46 | |

| 10. I am confused about how I feel. | 0.52 | 4.26 | |

| 8. I know exactly how I am feeling. | 0.69 | 3.22 | |

| 1. I am clear about my feelings. | 0.44 | 2.18 |

| Question | Component | Factor Loading | t-Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. My first impressions of people usually turn out to be right. | self-deception | 0.55 | 2.51 |

| 2. It would be hard for me to break my bad habits. (R) | 0.54 | 3.24 | |

| 3. I don’t care to know what other people really think of me. | 0.69 | 3.54 | |

| 4. I have not always been honest with myself. (R) | 0.49 | 5.54 | |

| 5. I always know why I like things. | 0.50 | 3.25 | |

| 6. When my emotions are aroused, it biases my thinking. (R) | 0.51 | 2.21 | |

| 7. Once I’ve made up my mind, other people cannot change my opinion. | 0.43 | 3.12 | |

| 8. I am not a safe driver when I exceed the speed limit. (R) | 0.42 | 2.52 | |

| 9. I am fully in control of my own fate. | 0.70 | 3.13 | |

| 10. It’s hard for me to shut off a disturbing thought. (R) | 0.60 | 2.53 | |

| 11. I never regret my decisions. | 0.77 | 2.52 | |

| 12. I sometimes lose out on things because I can’t make up my mind soon enough. (R) | 0.50 | 3.14 | |

| 13. The reason I vote is that my vote can make a difference | 0.36 | 5.25 | |

| 14. People don’t seem to notice me and my abilities. (R) | 0.52 | 4.10 | |

| 15. I am a completely rational person. | 0.61 | 2.31 | |

| 16. I rarely appreciate criticism. (R) | 0.49 | 6.12 | |

| 17. I am very confident of my judgments. | 0.53 | 2.12 | |

| 18. I have sometimes doubted my ability as a lover. (R) | 0.52 | 4.10 | |

| 19. It’s all right with me if some people happen to dislike me. | 0.52 | 3.45 | |

| 20. I’m just an average person. (R) | 0.42 | 3.26 | |

| 21. I sometimes tell lies if I have to. (R) | Impression Management | 0.44 | 3.54 |

| 22. I never cover up my mistakes. | 0.49 | 2.19 | |

| 23. There have been occasions when I have taken advantage of someone. (R) | 0.47 | 2.28 | |

| 24. I never swear. | 0.59 | 3.41 | |

| 25. I sometimes try to get even rather than forgive or forget. (R) | 0.38 | 3.18 | |

| 26. I always obey laws, even if I’m unlikely to get caught. | 0.51 | 3.02 | |

| 27. I have said something bad about a friend behind his/her back. (R) | 0.55 | 4.15 | |

| 28. When I hear people talking privately, I avoid listening. | 0.59 | 3.49 | |

| 29. I have received too much change from a salesperson without telling him or her. | 0.45 | 3.39 | |

| 30. I always declare everything at customs. | 0.38 | 4.05 | |

| 31. When I was young, I sometimes stole things. (R) | 0.36 | 2.02 | |

| 32. I have never dropped litter on the street. | 0.55 | 3.25 | |

| 33. I sometimes drive faster than the speed limit. (R) | 0.42 | 5.05 | |

| 34. I never read sexy books or magazines. | 0.40 | 3.45 | |

| 35. I have done things that I don’t tell other people about. (R) | 0.29 | 2.19 | |

| 36. I never take things that don’t belong to me | 0.71 | 2.12 | |

| 37. I have taken sick-leave from work or school even though I wasn’t really sick. (R) | 0.54 | 3.77 | |

| 38. I have never damaged a library book or store merchandise without reporting it. | 0.49 | 3.21 | |

| 39. I have some pretty awful habits. (R) | 0.30 | 3.36 | |

| 40. I don’t gossip about other people’s business. | 0.63 | 2.21 |

| Question | Component | Factor Loading | t-Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. When faced with a problem, I try to forget it. | Autonomy | 0.42 | 3.12 |

| 2. I need frequent encouragement from others for me to keep working at a difficult task. | 0.59 | 3.12 | |

| 5. If I want something, I work hard to get it. | 0.56 | 4.19 | |

| 6. I prefer to learn the facts about something from someone else rather than have to dig them out for myself. | 0.40 | 2.15 | |

| 8. I have a hard time saying “no” when someone tries to sell something I don’t want. | 0.46 | 4.12 | |

| 10. I consider the different sides of an issue before making any decisions. | 0.33 | 4.04 | |

| 14. I need someone else to praise my work before I am satisfied with what I’ve done. | 0.60 | 3.37 | |

| 16. When something is going to affect me, I learn as much about it as I can. | 0.40 | 4.46 | |

| 18. For me, knowing I’ve done something well is more important than being praised by someone else. | 0.56 | 3.72 | |

| 19. I let other people’s demands keep me from doing things I want to do. | 0.49 | 5.52 | |

| 22. I get discouraged when doing something that takes a long time to achieve results. | 0.57 | 3.45 | |

| 26. I prefer situations where I can depend on someone else’s ability rather than just my own. | 0.40 | 6.15 | |

| 27. Having someone important tell me I did a good job is more important to me than feeling I’ve done a good job. | 0.73 | 3.11 | |

| 3. I like jobs where I can make decisions and be responsible for my own work. | Leadership | 0.63 | 5.12 |

| 7. I will accept jobs that require me to supervise others | 0.68 | 3.49 | |

| 9. I like to have a say in any decisions made by any group I’m in. | 0.56 | 7.82 | |

| 12. Whenever something good happens to me, I feel it is because I’ve earned it. | 0.38 | 2.56 | |

| 13. I enjoy being in a position of leadership. | 0.73 | 3.41 | |

| 15. I am sure enough of my opinions to try and influence others. | 0.64 | 3.49 | |

| 17. I decide to do things on the spur of the moment. | 0.46 | 2.52 | |

| 25. I enjoy trying to do difficult tasks more than I enjoy trying to do easy tasks. | 0.59 | 3.14 | |

| 4. I change my opinion when someone I admire disagrees with me. | Steadfastness/decisiveness | 0.68 | 5.25 |

| 11. What other people think has a great influence on my behavior. | 0.49 | 4.10 | |

| 20. I stick to my opinions when someone disagrees with me. | 0.64 | 2.31 | |

| 21. I do what I feel like doing, not what other people think I ought to do. | 0.61 | 2.24 | |

| 23. When part of a group, I prefer to let other people make all the decisions. | 0.57 | 3.96 | |

| 24. When I have a problem, I follow the advice of friends or relatives. | 0.45 | 3.46 | |

| 28. When I’m involved in something, I try to find out all I can about what is going on, even when someone else is in charge. | 0.41 | 2.72 |

References

- Anke, J.; Ringhand, M.; Petzoldt, T.; Gehlert, T. Micro-mobility and road safety: Why do e-scooter riders use the sidewalk? Evidence from a German field study. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2023, 15, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Hossain, A.; Rahman, M.A.; Sheykhfard, A.; Kutela, B. Case Study on the Traffic Collision Patterns of E-Scooter Riders. Transp. Res. Rec. 2024, 2678, 575–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchino, J.B.; Chaudhary, N.K.; Solomon, M.G. How Are E-Scooter Speed-Limiter Settings Associated with User Behavior? Observed Speeds and Road, Sidewalk, and Bike Lane Use in Austin, TX, and Washington, D.C. Transp. Res. Rec. 2023, 2678, 03611981231214518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, G.; Mehra, S.; Haider, S.F.; Tsui, G.O.; Chernock, B.; Glass, N.E.; Livingston, D.; Sheikh, F. Electric scooter sharing systems: An analysis of injury patterns associated with their introduction. Injury 2023, 54, 110781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.W.; Lee, S.C.; Yoon, S.H. Exploring e-scooter riders’ risky behaviour: Survey, observation, and interview study. Ergonomics 2024, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopplin, C.S.; Brand, B.M.; Reichenberger, Y. Consumer acceptance of shared e-scooters for urban and short-distance mobility. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 91, 102680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, R.; Sitges, E.; Tirado, S. Psychosocial Predictors of Compliance with Speed Limits and Alcohol Limits by Spanish Drivers: Modeling Compliance of Traffic Rules. Laws 2015, 4, 602–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; He, C.; Liu, S. How psychological factors affect speeding behavior: Analysis based on an extended theory of planned behavior in a Chinese sample. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2023, 93, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huemer, A.K.; Banach, E.; Bolten, N.; Helweg, S.; Koch, A.; Martin, T. Secondary task engagement risk-taking safety-related equipment use in German bicycle e-scooter riders—An observation. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2022, 172, 106685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, M.A.; Thomson, J.A. The social cognitive determinants of offending drivers’ speeding behaviour. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2010, 42, 1595–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duttweiler, P.C. The Internal Control Index: A Newly Developed Measure of Locus of Control. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1984, 44, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almannaa, M.H.; Alsahhaf, F.A.; Ashqar, H.I.; Elhenawy, M.; Masoud, M.; Rakotonirainy, A. Perception Analysis of E-Scooter Riders and Non-Riders in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: Survey Outputs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engström, I.; Gregersen, N.P.; Hernetkoski, K.; Keskinen, E.; Nyberg, A. Young Novice Drivers, Driver Education and Training; Lit. Rev.; Statens väg- och transportforskningsinstitut: Linköping, Sweden, 2003; Available online: https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:vti:diva-6358 (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Barić, D.; Havârneanu, G.M.; Măirean, C. Attitudes of learner drivers toward safety at level crossings: Do they change after a 360° video-based educational intervention? Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2020, 69, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šeibokaitė, L.; Endriulaitienė, A.; Sullman, M.J.M.; Markšaitytė, R.; Žardeckaitė-Matulaitienė, K. Difficulties in emotion regulation and risky driving among Lithuanian drivers. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2017, 18, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useche, S.A.; Gonzalez-Marin, A.; Faus, M.; Alonso, F. Environmentally friendly, but behaviorally complex? A systematic review of e-scooter riders’ psychosocial risk features. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cestac, J.; Paran, F.; Delhomme, P. Young drivers’ sensation seeking, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control and their roles in predicting speeding intention: How risk-taking motivations evolve with gender and driving experience. Saf. Sci. 2011, 49, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, T.; Lajunen, T.; Chliaoutakis, J.E.; Parker, D.; Summala, H. Cross-cultural differences in driving skills: A comparison of six countries. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2006, 38, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bener, A.; Jadaan, K.; Crundall, D.; Calvi, A. The effect of aggressive driver behaviour, violation and error on vehicle crashes involvement in Jordan. Int. J. Crashworthiness 2020, 25, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldon, P.; Morrissey, P.; O’Mahony, M. Long-term cost of ownership comparative analysis between electric vehicles and internal combustion engine vehicles. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 39, 578–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Chin, W.W. A Comparison of Approaches for the Analysis of Interaction Effects Between Latent Variables Using Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2010, 17, 82–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratz, K.L.; Roemer, L. Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: Development, Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2004, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, H. Risk-taking attitudes and risky driving behaviour. Transp. Res. Part. F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2004, 7, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazuras, L.; Rowe, R.; Poulter, D.R.; Powell, P.A.; Ypsilanti, A. Impulsive and Self-Regulatory Processes in Risky Driving Among Young People: A Dual Process Model. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-Y.; Chung, J.-H.; Son, B. Analysis of traffic accident size for Korean highway using structural equation models. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2008, 40, 1955–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulhus, D.L. Paulhus Deception Scales (PDS): The Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding-7; User’s Manual; Multi-Health Systems: North Tonawanda, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tully, R.J.; Bailey, T. Validation of the Paulhus Deception Scales (PDS) in the UK and examination of the links between PDS and personality. J. Criminol. Res. Policy Pract. 2017, 3, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Zhang, N.; Li, W.; Xi, J. Modeling and Application of Pedestrian Safety Conflict Index at Signalized Intersections. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2014, 2014, 314207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebb, B.J.; Beck, J.G. Worry Versus Anxiety: Is There Really a Difference? Behav. Modif. 1998, 22, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 251 | 52.9 |

| Female | 223 | 47.1 | |

| Age group (years) | 18–20 | 137 | 28.9 |

| 20–22 | 161 | 34.0 | |

| 22–24 | 176 | 37.1 | |

| Accident experience (with e-scooter) | None | 412 | 86.9 |

| At least one | 62 | 13.1 | |

| Traffic fines (car or other vehicle) | None | 338 | 71.3 |

| One or more | 136 | 28.7 |

| Path | β | SE | t | p | 95% CI (LL, UL) | Hypothesis Supported? | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Dysregulation → Speeding Intention | +0.66 | 0.09 | 7.33 | <0.001 | [0.49, 0.83] | H1 ✔ | Higher dysregulation increases speeding propensity |

| Internal Locus of Control → Speeding Intention | −0.52 | 0.08 | −6.50 | <0.001 | [−0.68, −0.36] | H2 ✔ | Greater internal control reduces speeding intention |

| Gender → Speeding Intention (M = 1) | +0.07 | 0.05 | 1.40 | 0.162 | [−0.03, 0.17] | No  | Non-significant |

| Age → Speeding Intention | −0.10 | 0.06 | −1.67 | 0.096 | [−0.22, 0.02] | No  | Slight negative trend (ns) |

| Riding Experience → Speeding Intention | −0.05 | 0.05 | −1.02 | 0.308 | [−0.15, 0.05] | No  | Experience effect non-significant |

| Index | Abbreviation | Obtained Value | Recommended Threshold (Lee et al., 2008 [25]) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Fit Index | CFI | 0.93 | ≥0.90 | Acceptable fit |

| Tucker–Lewis Index | TLI | 0.91 | ≥0.90 | Acceptable fit |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation | RMSEA | 0.045 | ≤0.08 (≤0.05 = close fit) | Close fit |

| Standardized Root Mean Square Residual | SRMR | 0.071 | ≤0.08 | Good fit |

| Coefficient of Determination (for Endogenous Construct) | R2 | 0.754 | ≥0.33 = moderate ≥0.67 = substantial | Substantial explanatory power |

| Cross-validated Redundancy Index | Q2 | 0.37 | >0.35 = substantial predictive relevance | High predictive relevance |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lei, T.; Shaaban, K. Exploring Psychosocial Determinants of Young Adults E-Scooter Speeding: A TPB-Aligned SEM Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10645. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310645

Lei T, Shaaban K. Exploring Psychosocial Determinants of Young Adults E-Scooter Speeding: A TPB-Aligned SEM Study. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10645. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310645

Chicago/Turabian StyleLei, Ting, and Khaled Shaaban. 2025. "Exploring Psychosocial Determinants of Young Adults E-Scooter Speeding: A TPB-Aligned SEM Study" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10645. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310645

APA StyleLei, T., & Shaaban, K. (2025). Exploring Psychosocial Determinants of Young Adults E-Scooter Speeding: A TPB-Aligned SEM Study. Sustainability, 17(23), 10645. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310645