Beyond Self-Certification: Evaluating the Constraints and Opportunities of Participatory Guarantee Systems in Latin America

Abstract

1. Introduction

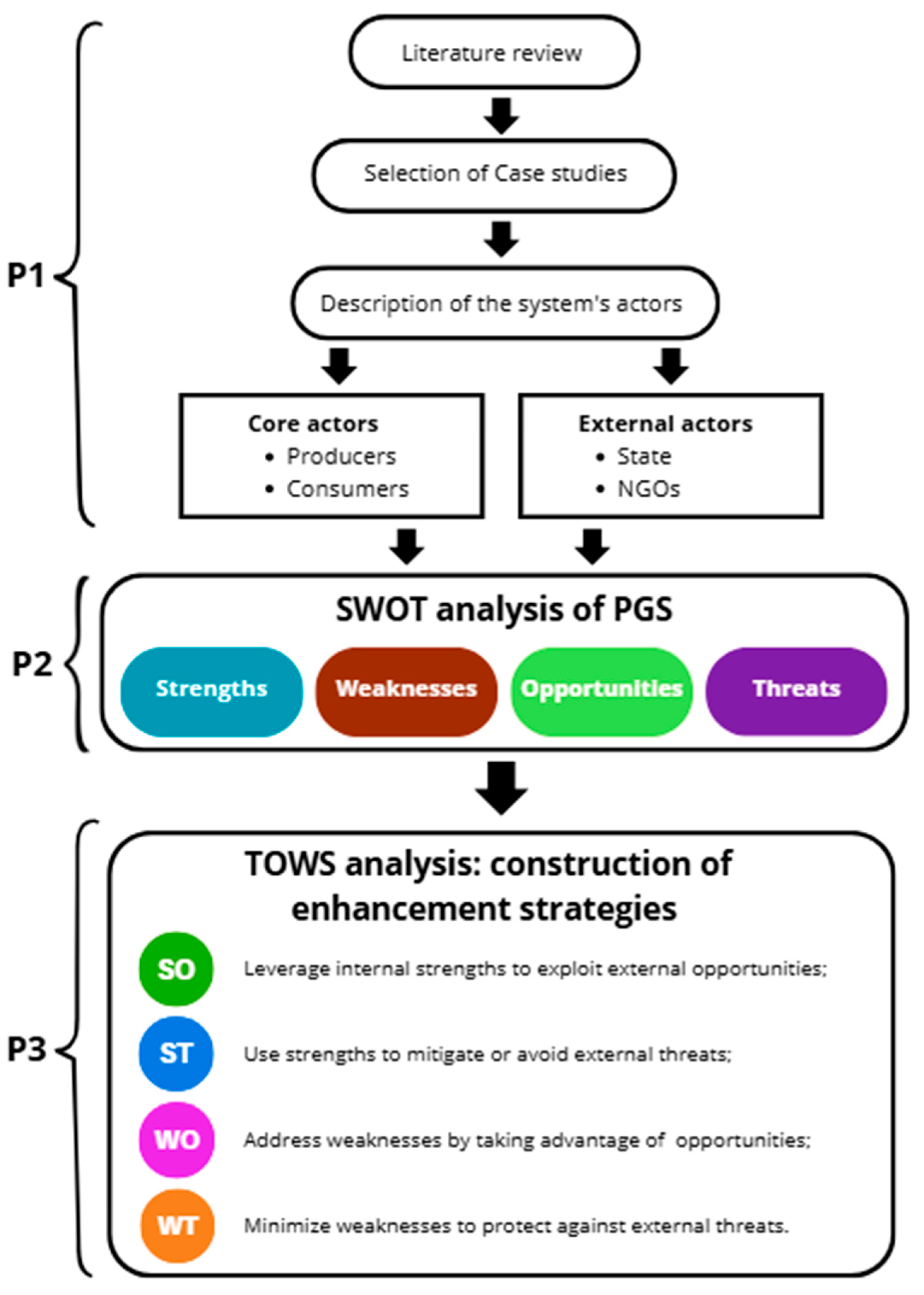

2. Research Method and Approach

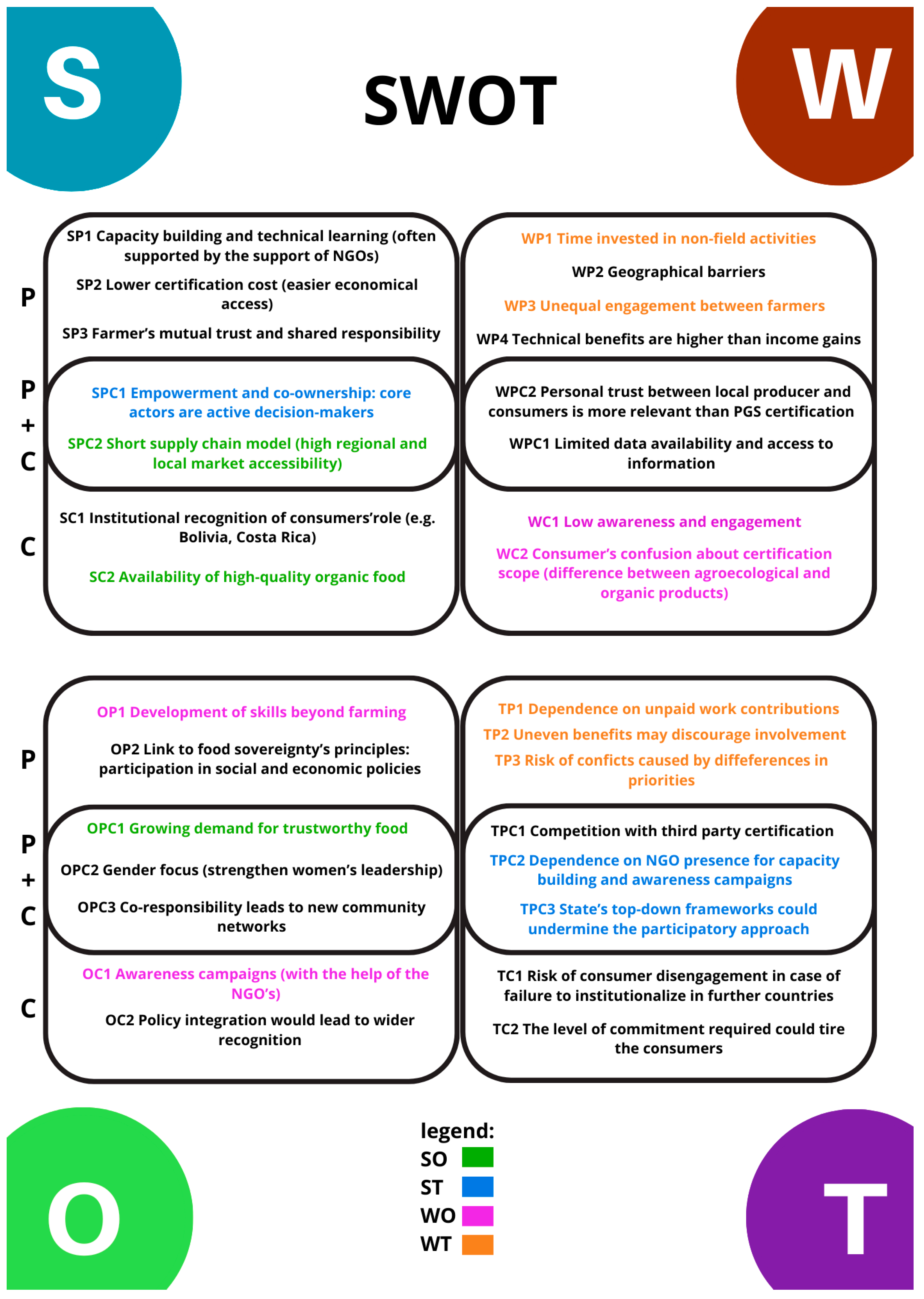

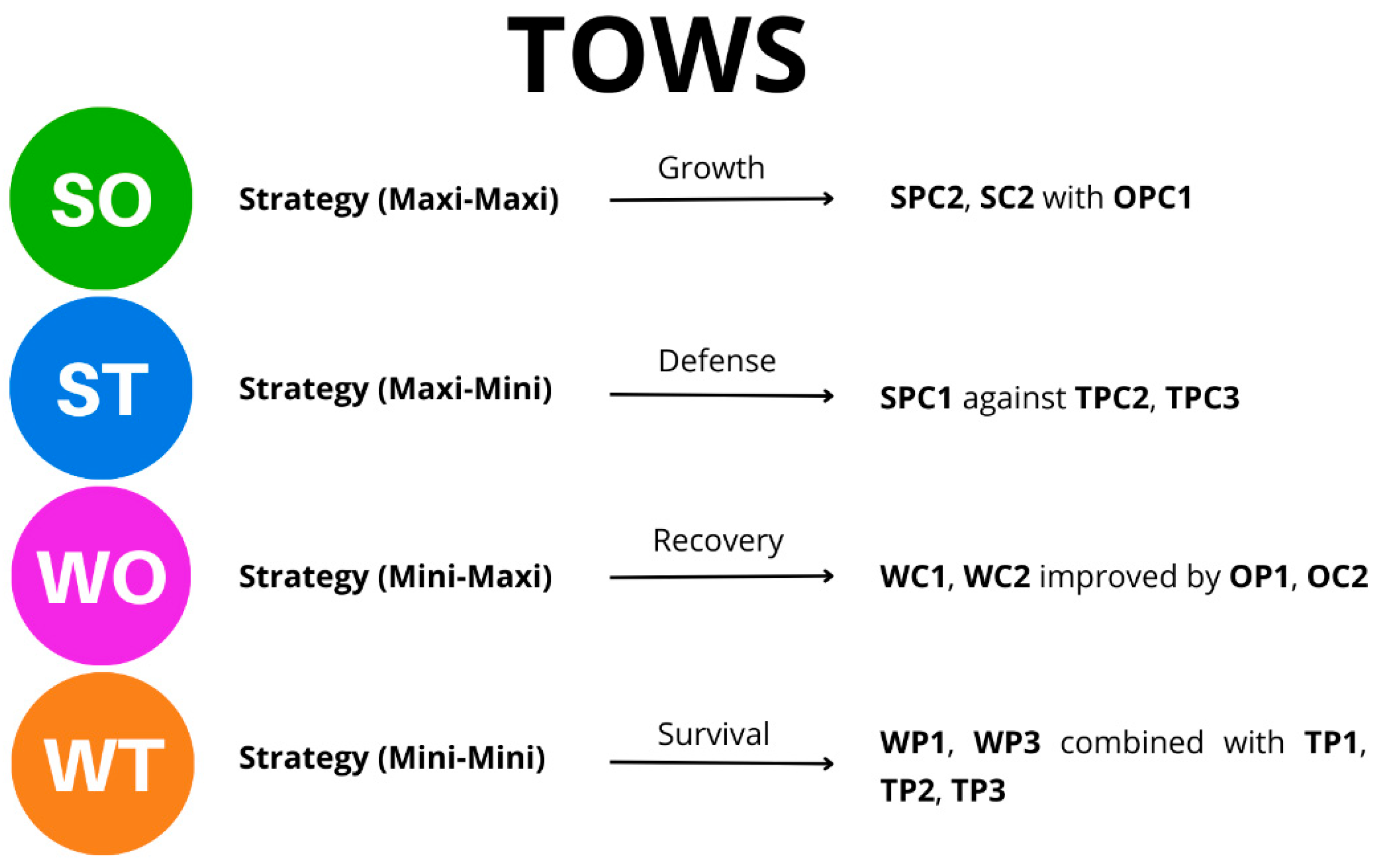

- SO: leverage internal strengths to exploit external opportunities; these are growth-oriented and proactive strategies;

- ST: use strengths to mitigate or avoid external threats; these are defensive strategies;

- WO: address internal weaknesses by taking advantage of external opportunities; these are recovery or improvement strategies; and

- WT: minimize weaknesses to protect against external threats; these are conservative or survival-oriented strategies.

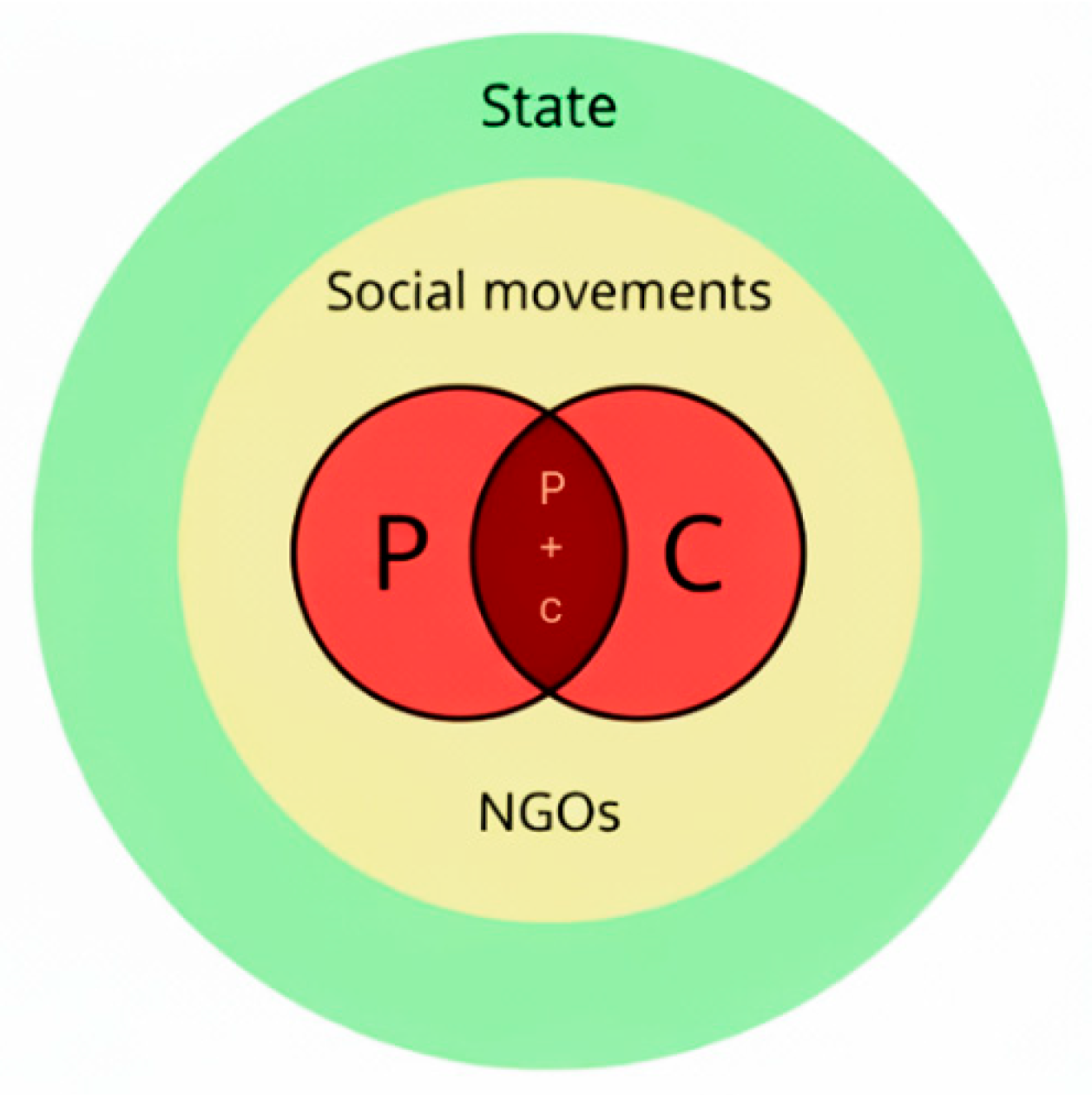

3. PGS Stakeholders

3.1. Core Actors

3.1.1. Producers

3.1.2. Consumers

3.2. External Actors

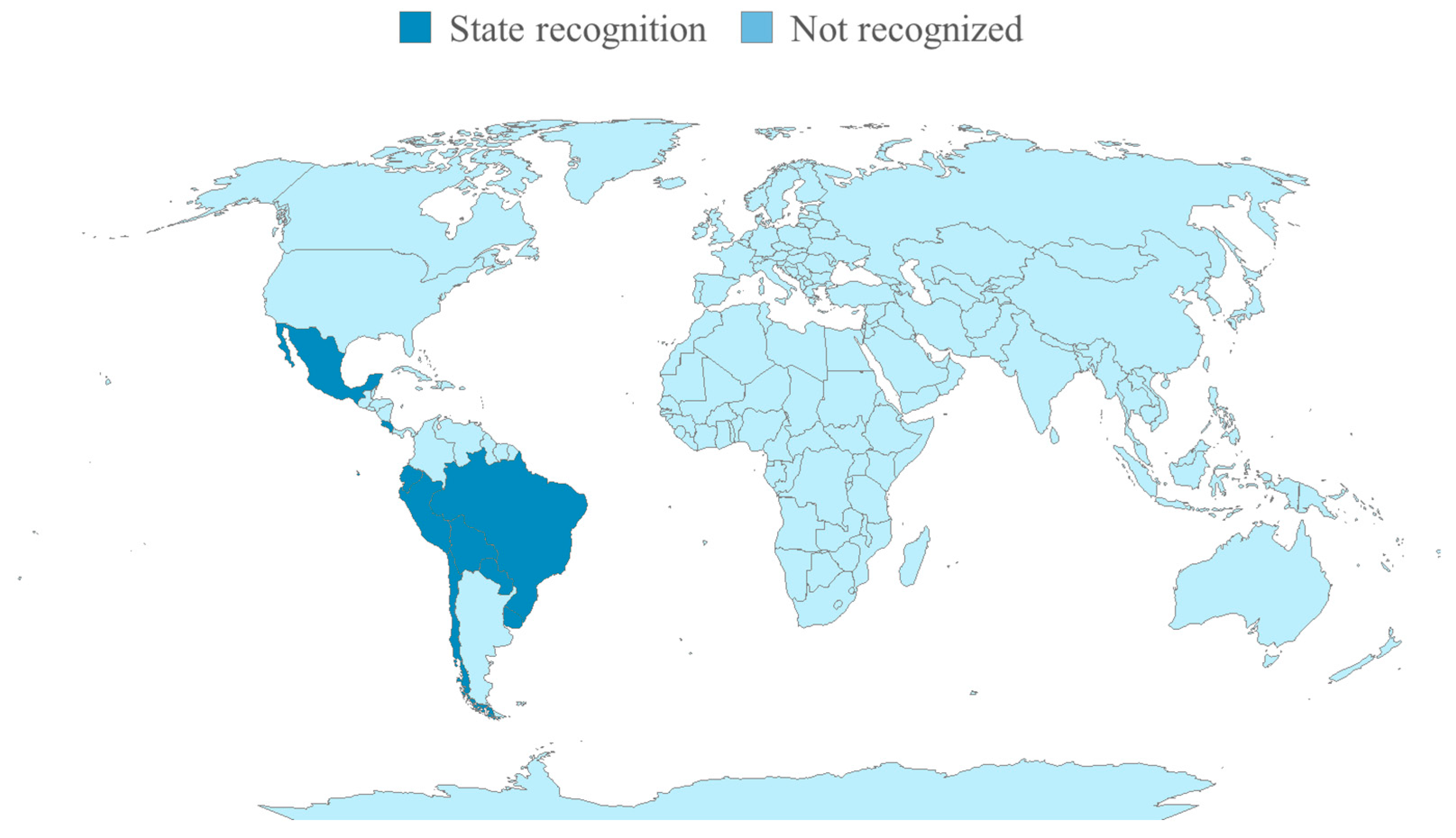

3.2.1. State

3.2.2. NGOs and Civil Society Organizations

4. Potential and Limits of PGS Certification: SWOT and TOWS Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mook, A.; Overdevest, C. What Drives Market Construction for Fair Trade, Organic, and GlobalGAP Certification in the Global Citrus Value Chain? Evidence at the Importer Level in the Netherlands and the United States. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 2996–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinshausen, F.; Richter, T.; Blockeel, J.; Huber, B. Internal Control Systems in Organic Agriculture: Significance, Opportunities and Challenges; FiBL: Frick, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Willer, H.; Trávní, J. The World of Organic Agriculture Statistics and Emerging Trends 2025; Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL): Frick, Switzerland; IFOAM—Organics International: Bonn, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Avesani, M. Agri-Food Certifications in Latin America: Drivers of Accountability or Gateways to Fraud and Corruption? Eur. J. Crim. Policy Res. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willer, E.H.; Lernoud, J. The World of Organic Agriculture Statistics and Emerging Trends 2019; Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL): Frick, Switzerland; IFOAM—Organics International: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Montefrio, M.J.F.; Johnson, A.T. Politics in Participatory Guarantee Systems for Organic Food Production. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 65, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hruschka, N.; Kaufmann, S.; Vogl, C.R. The Benefits and Challenges of Participating in Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS) Initiatives Following Institutional Formalization in Chile. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2021, 20, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannucci, G.; Sacchi, G. The Evolution of Organic Market Between Third-Party Certification and Participatory Guarantee Systems. Bio-Based Appl. Econ. 2021, 10, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Cifuentes, M.; Vogl, C.R.; Cuéllar Padilla, M. Participatory Guarantee Systems in Spain: Motivations, Achievements, Challenges and Opportunities for Improvement Based on Three Case Studies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchi, G. Italian Participatory Guarantee Systems for Organic Agriculture: From Best Practices towards the Evolution of Policies Framework. In Proceedings of the International Conference 2015 Agroecology for Organic Agriculture in the Mediterranean, Vignola, Italy, 10–12 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, R. Sistemas Participativos de Garantía (SPGs) Agroecológicos en la Argentina; University of Buenos Aires: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner, C. Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS) How PGS can Intensify Knowledge Exchange Between Farmers. In Proceedings of the IFOAM Organic World Congress, Istanbul, Turkey, 13–15 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bellante, L. Building the Local Food Movement in Chiapas, Mexico: Rationales, Benefits, and Limitations. Agric. Hum. Values 2017, 34, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouagnimbeck, H.; Ugas, R.; Villanueva, J. Preliminary Results of the Global Comparative Study on Interactions between PGS and Social Processes. In Proceedings of the 4th ISOFAR Scientific Conference, Organic World Congress, Istanbul, Turkey, 13–15 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chaparro-Africano, A.-M.; Páramo, M. Challenges of the Participatory Guarantee System of the Network of Agroecological Markets of Bogota-Region, as a Strategy for Certification and Promotion of Agroecology. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2022, 20, 1307–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bara, C.R.; Gálvez, R.; Hernández, H.; Fortanelli, J. Adaptation of a Participatory Organic Certification System to the Organic Products Law in Six Local Markets in Mexico. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2017, 42, 48–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuéllar-Padilla, M.; Ganuza-Fernandez, E. We Don’t Want to Be Officially Certified! Reasons and Implications of the Participatory Guarantee Systems. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Home, R.; Bouagnimbeck, H.; Ugas, R.; Arbenz, M.; Stolze, M. Participatory Guarantee Systems: Organic Certification to Empower Farmers and Strengthen Communities. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2017, 41, 526–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetti Pessôa Candiotto, L. Toward the Organic Product Certification: Participatory Guarantee System (PGS) in the Certification Process and the Contribution of Ecovida Agroecology Network. In Advances in Organic Farming; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 209–222. ISBN 978-0-12-822358-1. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, E.; Tovar, L.G.; Gueguen, E.; Humphries, S.; Landman, K.; Rindermann, R.S. Participatory Guarantee Systems and the Re-Imagining of Mexico’s Organic Sector. Agric. Hum. Values. 2016, 33, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hruschka, N.; Kaufmann, S.; Vogl, C.R. The Right to Certify—Institutionalizing Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS): A Latin American Cross-Country Comparison. Glob. Food Secur. 2024, 40, 100748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre de Lima, F.; Neutzling, D.M.; Gomes, M. Do Organic Standards Have a Real Taste of Sustainability?—A Critical Essay. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 81, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.A.; Nicholls, C.I. Agroecology: Challenges and Opportunities for Farming in the Anthropocene. Int. J. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2020, 47, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servicio Nacional de Sanidad, Inocuidad y Calidad Agroalimentaria Gobierno. 2025. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/senasica (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Ministério da Agricultura e Pecuária Home. Available online: https://www.gov.br/agricultura (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Binder, N.; Vogl, C. Participatory Guarantee Systems in Peru: Two Case Studies in Lima and Apurímac and the Role of Capacity Building in the Food Chain. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, S.; Hruschka, N.; Vildozo, L.; Vogl, C.R. Alternative Food Networks in Latin America—Exploring PGS (Participatory Guarantee Systems) Markets and Their Consumers: A Cross-Country Comparison. Agric. Hum. Values 2023, 40, 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengnick-Hall, C.A.; Beck, T.E.; Lengnick-Hall, M.L. Developing a Capacity for Organizational Resilience Through Strategic Human Resource Management. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2011, 21, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Desarrollo Rural y Tierras Inicio. Available online: http://www.ruralytierras.gob.bo/ (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Fonseca, M.; Wilkinson, J.; Egelyng, H.; Mascarenhas, G. The Institutionalization of Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS) in Brazil: Organic and Fair Trade Initiatives. In Proceedings of the 2nd ISOFAR Scientific Conference, 16th IFOAM Organic World Congress, Modena, Italy, 18–20 June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Servicio Nacional de Calidad y Sanidad Vegetal y de Semillas Senave. Available online: https://www.senave.gov.py/ (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Servicio Nacional de Sanidad Agraria del Perú Plataforma del Estado Peruano. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/senasa (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Presidencia de la República Decreto N° 175/022: Reglamentación de la Certificación de Los. Available online: https://www.impo.com.uy/bases/decretos/175-2022 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Thamchaisophis, N. Stakeholders’ Trustability Toward Co-Creating and Co-Investment in Safe Agriculture. Humanit. Arts Soc. Sci. Stud. 2021, 21, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Agricultura y Ganadería Ley de Agricultura Orgánica. Available online: https://www.mag.go.cr/ (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero Ley N° 20.089: Sistema Nacional de Certificación de Productos Orgánicos Agrícolas. Available online: https://www.sag.gob.cl/ambitos-de-accion/certificacion-de-productos-organicos (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Gillis, A.S.; Bigelow, S.J.; Pratt, M.K. What Is a SWOT Analysis Definition, Examples and How to CIO.—References—Scientific Research Publishing. 2025. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=4050277 (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Kearns, K.P. From Comparative Advantage to Damage Control: Clarifying Strategic Issues Using Swot Analysis. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 1992, 3, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weihrich, H. The TOWS Matrix—A Tool for Situational Analysis. Long Range Plan. 1982, 15, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaloo, P.; Chamhuri, S.; Liong, C.; Isahak, A. Identification of Strategies for Urban Agriculture Development: A SWOT Analysis. Plan. Malays. J. 2018, 16, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozac, M. SWOT Analysis and TOWS Matrix—Similarities and Differences. Ekon. Istraživanja Econ. Res. 2008, 21, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Neumeier, S. Why do Social Innovations in Rural Development Matter and Should They be Considered More Seriously in Rural Development Research?—Proposal for a Stronger Focus on Social Innovations in Rural Development Research. Sociol. Rural. 2012, 52, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torquati, B.; Pedini, S.; Santucci, F.M.; Da Re, R. Participatory Guarantee System and Social Capital for Sustainable Development in Brazil: The Case Study of OPAC Orgânicos Sul de Minas. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Varella Miranda, B.; Parcell, J.; Chen, C. The Foundations of Institutional-Based Trust in Farmers’ Markets. Agric. Hum. Values 2019, 36, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rover, O.J.; de Gennaro, B.C.; Roselli, L. Social Innovation and Sustainable Rural Development: The Case of a Brazilian Agroecology Network. Sustainability 2017, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosset, P. Research, Part of a Special Feature on A Social-Ecological Analysis of Diversified Farming Systems: Benefits, Costs, Obstacles, and Enabling Policy Frameworks Rural Social Movements and Agroecology: Context, Theory, and Process. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intriago, R.; Gortaire Amézcua, R.; Bravo, E.; O’Connell, C. Agroecology in Ecuador: Historical processes, achievements, and challenges. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2017, 41, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skotnicka-Zasadzien, B.; Zasadzień, M.; GREBSKI, W. Application of tows/swot analysis as an element of strategic management on the example of a manufacturing company. Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technol. Organ. Manag. Ser. 2023, 2023, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deroche-Leydier, Y. Enhancing the Resilience of Short Food Supply Chains: Toward a Relational Understanding of the Resilience Process in the Face of Inflation. Agric. Food Econ. 2025, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, M.; De Rosa, M.; Charatsari, C.; Lioutas, E.D.; Vecchio, Y. Enhancing Value Creation in Short Food Supply Chains Through Digital Platforms. Agric. Food Econ. 2025, 13, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennhardt, L.; Home, R.; Yen, N.; Hoi, P.; Ferrand, P.; Grovermann, C. Mixed Method Evaluation of Factors Influencing the Adoption of Organic Participatory Guarantee System Certification Among Vietnamese Vegetable Farmers. Agric. Hum. Values 2024, 42, 885–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchi, G.; Romanello, L.; Canavari, M. The Future of Organic Certification: Potential Impacts of the Inclusion of Participatory Guarantee Systems in the European Organic Regulation. Agric. Econ. 2024, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Countries | N° Specific Articles | N° Government Docs | N° Cross-Country Included | N° Total per Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 1 [11] | 0 | 1 [22] | 2 |

| Bolivia | - | 1 [24] | 2 [22,25] | 3 |

| Brazil | 4 [20,26,27,28] | 1 [29] | 1 [22] | 6 |

| Chile | 1 [7] | 1 [30] | 2 [22,25] | 4 |

| Colombia | 1 [16] | - | 1 [22] | 2 |

| Costa Rica | - | 1 [31] | 2 [22,25] | 3 |

| Ecuador | 1 [30] | - | 1 [22] | 2 |

| Mexico | 3 [14,17,21] | 1 [32] | 2 [22,25] | 6 |

| Paraguay | - | 1 [33] | 1 [22] | 2 |

| Peru | 1 [34] | 1 [35] | 1 [22] | 3 |

| Uruguay | - | 1 [36] | 1 [22] | 2 |

| Total | 12 | 8 | 15 | 35 |

| Countries | N° Producers Articles | N° Consumers Articles | N° NGOs Articles | N° State Articles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Bolivia | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Brazil | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Chile | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Colombia | 1 | - | 1 | 1 |

| Costa Rica | - | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Ecuador | 1 | - | - | 2 |

| Mexico | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Paraguay | - | - | - | 1 |

| Peru | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Uruguay | - | - | - | 1 |

| Total | 11 | 7 | 7 | 18 |

| Countries | Year of Recognition | Competent Authority |

|---|---|---|

| Bolivia | 2006 | SENASAG—Servicio Nacional de Sanidad Agropecuaria e Inocuidad Alimentaría |

| Brazil | 2007 | CPOR—Coordinación de Producción Organica |

| Chile | 2016 | SAG—Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero |

| Costa Rica | 2017 | ARAO—Acreditación y Registro en Producción Organica |

| Ecuador | 2013 | AGROCALIDAD—Agencia de Regulación y Control Fito y Zoosanitario |

| Mexico | 2006 | SENASICA—Servicio Nacional De Sanidad, Inocuidad Y Calidad Agroalimentaria |

| Paraguay | 2008 | SENAVE—Servicio Nacional de Calidad y Sanidad Vegetal y de Semillas |

| Peru | 2006 | SENASA—Servicio Nacional de Sanidad Agraria |

| Uruguay | 2008 | MGAP—Ministerio de Ganadería, Agricultura y Pesca; Dirección General de Servicios Agrícolas |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bregolin, R.; Cardone, G.; Brunetti, L.; Cannizzaro, F.; Peano, C. Beyond Self-Certification: Evaluating the Constraints and Opportunities of Participatory Guarantee Systems in Latin America. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10483. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310483

Bregolin R, Cardone G, Brunetti L, Cannizzaro F, Peano C. Beyond Self-Certification: Evaluating the Constraints and Opportunities of Participatory Guarantee Systems in Latin America. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10483. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310483

Chicago/Turabian StyleBregolin, Riccardo, Gaetano Cardone, Lorenzo Brunetti, Fabrizio Cannizzaro, and Cristiana Peano. 2025. "Beyond Self-Certification: Evaluating the Constraints and Opportunities of Participatory Guarantee Systems in Latin America" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10483. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310483

APA StyleBregolin, R., Cardone, G., Brunetti, L., Cannizzaro, F., & Peano, C. (2025). Beyond Self-Certification: Evaluating the Constraints and Opportunities of Participatory Guarantee Systems in Latin America. Sustainability, 17(23), 10483. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310483