1. Introduction

The continuous evolution of modern societies necessitates the parallel transformation and adaptation of social infrastructure. Built environments—ranging from individual buildings and neighborhoods to entire cities and regions—have historically been designed based on outdated planning paradigms and socio-technical principles. As a result, many of these structures are increasingly incapable of meeting the complex and evolving needs of modern urban life [

1].

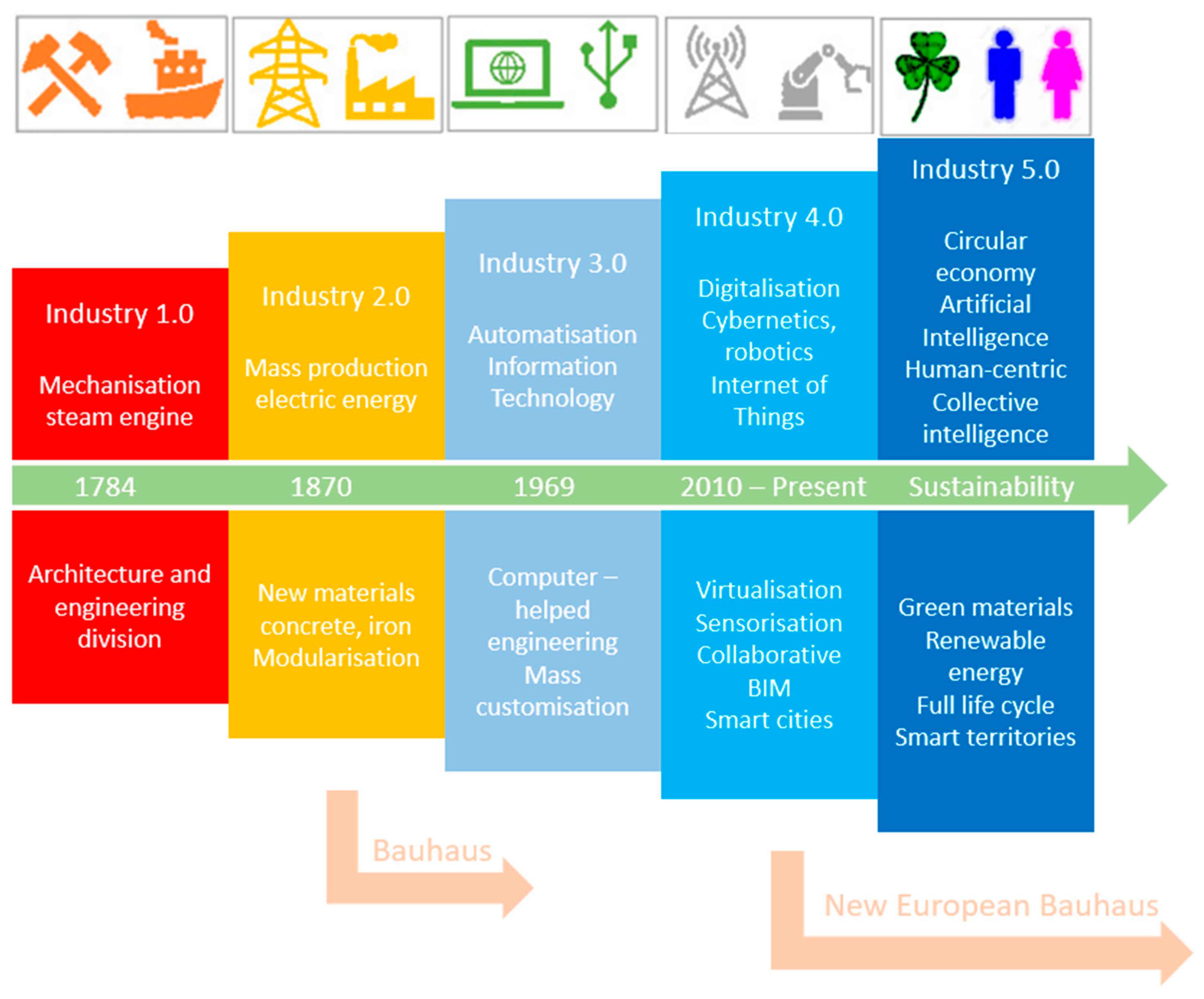

Over time, it becomes evident that technological and cultural advancements are linked to the transformation and regeneration of urban and regional environments. This dynamic relationship, first established during the First Industrial Revolution, when the separation between architecture and civil engineering began. The Second Industrial Revolution was governed by the introduction of new construction materials and modularization, while the Third revolutionized architecture and civil engineering through the use of computer-aided methodologies and mass customization [

2].

Currently, we are experiencing the Fourth Industrial Revolution, characterized by digitalization, cybernetics, and the Internet of Things (IoT). In architecture and civil engineering, this phase is reflected in key trends such as virtualization, sensorization, collaborative Building Information Modeling (BIM), and the emergence of the development of smart cities. The

Figure 1 below illustrates the chronological progression of the Industrial Revolutions and their corresponding influence on the fields of architecture and civil engineering [

2].

The next day of evolution is reflected in the 5th Industrial Revolution, the re-establishment of sustainability, which has already set its principles in the circular economy, artificial intelligence, human-centered targeting, and collective intelligence. Accordingly, architecture and civil engineering are entering a new era through the utilization of renewable energy, the use of green materials, full life cycle analysis, and the transformation of areas into smart territories [

2].

A central policy and design framework facilitating this transition is the NEB, a multidisciplinary initiative launched by the European Commission, reorienting architectural and engineering practices toward sustainability, esthetics, and inclusion [

3]. The launch of the NEB initiative has established a new paradigm in the planning, implementation, and evaluation of urban regeneration projects.

Already in 2012, the European Union adopted the Energy Efficiency Directive (Directive 2012/27/EU), which established as a central objective of regeneration strategies the integration of technical solutions aimed at achieving a more efficient built environment, while aligning its requirements with sustainable and cost-effective energy sources [

4]. Building on this directive, a wide range of methodological implementation models have since been developed, all grounded in the fundamental principles of energy efficiency and environmental protection. Initially, relatively simple frameworks were introduced, typically structured around four main stages: preparation, data collection and analysis, prioritization and decision-making, and final implementation with continuous monitoring [

5]. These were subsequently refined into more elaborate seven-stage methodologies [

6], which provided clearer distinctions between phases, placed greater emphasis on the technical dimension of interventions, and systematically embedded principles of impact assessment. In parallel, distinct methodological approaches were designed with the exclusive aim of strengthening stakeholder participation in decision-making processes [

7]. Over time, the evolution of these approaches has increasingly converged towards the formulation of two comprehensive and ambitious plans: the Strategic Plan and the Operational Plan. These frameworks summarize and consolidate all the critical stages necessary for the effective implementation of urban transformation projects [

8]. Nevertheless, what has not been sufficiently developed to date—and is proposed by the present study—is a fully integrated methodological framework that systematically combines stakeholder perspectives with strategic and operational planning, incorporates co-creation and co-decision practices, and ensures coherent implementation through a unified action plan, followed by structured execution and rigorous evaluation.

In direct alignment with the methodological frameworks previously developed, various models for monitoring effectiveness and evaluating the impact of urban regeneration projects have been introduced, most of which are structured around sets of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). Several studies adopt a narrowly focused perspective, concentrating on specific dimensions of project performance. For instance, some approaches evaluate exclusively the level of stakeholder involvement in urban regeneration projects through targeted indicators [

9], while others assess whether stakeholder expectations have been adequately addressed in the regeneration process [

10]. Similarly, distinct sets of indicators have been designed exclusively to measure the quality and extent of stakeholder participation in decision-making processes [

11]. Beyond stakeholder-centered models, other frameworks emphasize the particularities of the intervention area [

12], while additional studies advance computational approaches that rely on parameterized models and simulations to evaluate project outcomes [

13]. A more holistic, yet thematically restricted, proposal has also been developed, addressing Sustainability and Smart City agendas through indicators covering energy, social impacts, economy, and mobility [

14]. Of particular relevance is the model applied in the Rijeka case study [

15], which, like the present study, was tested on the real implementation of an urban project. Although it incorporates NEB principles, the Rijeka framework places greater emphasis on techno-economic monitoring indicators. In contrast, the framework proposed in this study advances a more comprehensive approach, establishing an evaluation plan that systematically analyzes, monitors, and assesses urban regeneration projects across multiple dimensions. Specifically, it integrates energy, environmental, economic, and digital indicators with measures of social impact, while explicitly aligning the evaluation process with the principles and values of the NEB. The proposed model links KPIs directly with NEB dimensions, thus ensuring that evaluation is both multidimensional and value-driven.

This paper presents the application of this integrated methodology within the European project Eyes, Hearts, Hands Urban Revolution (EHHUR), fully aligned with the NEB principles, in the city of Kozani, Greece. Kozani constitutes a particularly compelling case study, as it is undergoing a profound post-lignite transition while simultaneously being among the few European cities to have formally adopted a Climate Neutrality Plan for 2030. A dual context—industrial restructuring coupled with ambitious decarbonization targets—was explicitly incorporated into the design of the methodology and its adaptation to local conditions. The evaluation framework combines transferable, general KPIs consistent with NEB principles with context-specific indicators reflecting Kozani’s socio-technical profile, including social acceptance, cultural identity, and energy system transformation. Moreover, the methodology integrates participatory co-design activities, ensuring transparency, inclusiveness, and local ownership in the process of indicator selection and validation. By drawing on insights from all Lighthouse projects within the EHHUR framework—one of the first Horizon Europe initiatives dedicated to NEB implementation—this study constitutes one of the earliest documented applications of NEB methodologies in a city undergoing an active energy transition. It addresses a notable gap in the literature, where KPI-based evaluation frameworks for NEB-aligned urban regeneration remain underexplored. Through its cross-pilot analysis and adaptation to Kozani’s post-lignite transformation, the proposed framework demonstrates both replicability and contextual sensitivity. Ultimately, it offers a structured pathway for embedding esthetics, sustainability, and inclusion into urban monitoring systems and transition strategies, thereby promoting evidence-based, NEB-aligned approaches to urban regeneration.

2. Methodology

2.1. New European Bauhaus (NEB)

The New European Bauhaus (NEB), initiated by the European Commission in 2021, builds upon the principles of the historic Bauhaus movement, emphasizing a transdisciplinary, collaborative, and holistic approach. Positioned as a cultural and intellectual catalyst, the NEB integrates artistic expression, scientific inquiry, technological innovation, and cultural engagement through a life-centered design framework informed by ecological integrity and long-term sustainability [

16].

As a key component of the European Green Deal—the Commission’s overarching strategy to make Europe the first climate-neutral continent, decouple resource use from economic growth, and ensure inclusivity—the NEB fosters innovation in the built environment. It encourages solutions that go beyond purely technological or functional approaches by incorporating social, cultural, and design perspectives [

17].

NEB movement invites us to envision a future grounded in three core values:

Beauty,

Sustainability, and

Togetherness [

18]. These values are supported by three working principles:

participatory processes,

multi-level engagement and a

transdisciplinary approach. Together, they shape four thematic axes that define the movement’s vision [

19]:

Reconnecting with nature;

Regaining a sense of belonging;

Prioritizing the places and people who needed the most;

Shaping a circular industrial ecosystem and supporting life-cycle thinking.

2.2. Eyes Harts Hands Urban Revolution (EHHUR)

EHHUR is among the first European projects to move within the framework of NEB, implementing its actions in alignment with the initiative’s core values [

20].

The project aims to tackle complex socio-economic and cultural challenges—such as social segregation, vulnerable communities affected by energy poverty, coal transitions (decarbonization/delignification), as well as depopulated and degraded historic centers—through participatory and co-design processes that form the backbone of its methodology. It fosters a suite of tailored social innovation activities designed to engage urban stakeholders across multiple, interdisciplinary dimensions, including technological co-design, co-financing, and esthetic co-creation [

21]. Seven cities in seven different countries, each with distinct backgrounds and objectives, initiated the implementation of their respective urban regeneration projects. Despite their differences, they share two key commonalities: the application of the methodology developed and described below and the adoption of the principles and values of the NEB.

Through its implementation, EHHUR has developed and tested a comprehensive methodological framework to support cities in transforming their urban environments. This framework builds upon existing best practices while integrating the principles of NEB.

The resulting integrated methodology focuses on several innovative dimensions:

- I.

Engagement strategies that empower citizens as active participants in shaping their urban future and decision-making processes;

- II.

Financing schemes that involve both local businesses and citizens;

- III.

Adoption of digital and green technologies;

- IV.

Architectural design and material innovation addressing climate change and sustainability, while honoring cultural heritage;

- V.

Creative and artistic co-design in public and third-sector buildings and spaces.

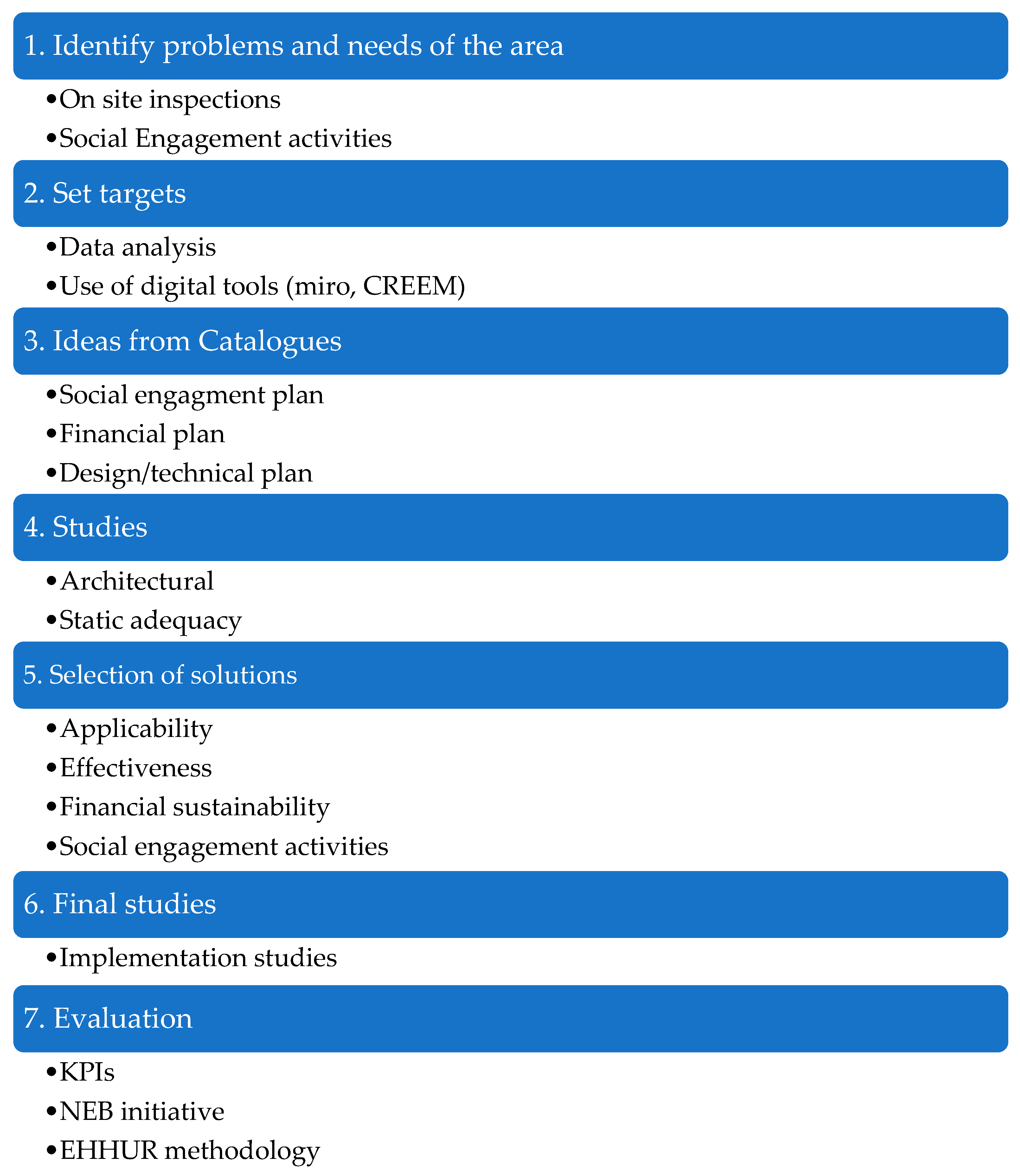

The methodology developed, assessed, and applied across each project’s LH—subject to minor adaptations tailored to the specific context of each case—followed a structured seven-stage process. The core steps of this methodology include the identification of challenges and needs, the formulation of strategic objectives, the selection of appropriate solutions, and the preparation of requisite technical studies. This is followed by project evaluation and the subsequent implementation of the proposed interventions.

The LH project in Kozani adopted the stage methodology grounded in the EHHUR framework and fully aligned with NEB principles, emphasizing sustainability, inclusivity, and esthetics. The methodology was tailored to local conditions and involved interdisciplinary collaboration among technical institutions, municipal authorities, architects, and engineers [

22].

Stage 1: focused on problem identification through infrastructure assessments and stakeholder engagement targeting the Primary Schools, the Cultural Center, and the Park of Agios Dimitrios. Grounded in the principle that the challenges of an urban area are most accurately perceived by those who experience them in their daily lives, a series of participatory activities was undertaken. These included the organization of surveys, the distribution of informational brochures and questionnaires, and the implementation of targeted engagement actions. The objective was to foster direct interaction with all relevant stakeholders—particularly the users of the buildings (students, teachers, and Cultural Center staff) and the park (parents, children, and citizens). Through these processes, the project team sought to identify, articulate, and analyze the genuine issues of the area as expressed by its community members.

Stage 2: entailed data evaluation and the use of digital tools (such as Miro 2.0-Miroverse and CRREM) to identify needs and establish clear qualitative and quantitative objectives. The problems identified during the initial stage were subsequently analyzed and evaluated by the study teams through digital tools. This integrated approach enhanced both the precision and reliability of the process, enabling a more accurate definition of qualitative objectives as well as the quantification of measurable targets.

Stage 3:

centered on the analysis of the Best Practice Catalogues developed within the framework of EHHUR (Social, Economic, Technical), extracting ideas and methodological approaches to support optimal implementation [

23,

24,

25]. An integral component of the applied methodology was the development of these three Best Practice Catalogues, designed to function both as consultative references and as sources of inspiration. The Social Best Practice Catalogue supported the design and implementation of a structured, meaningful, and effective stakeholder engagement strategy. The Economic Best Practice Catalogue facilitated the formulation of a financially sustainable plan, ensuring the long-term viability of the interventions. Finally, the Technical Best Practice Catalogue provided a repository of innovative concepts and technical solutions, whose implementation directly contributes to the attainment of the project’s overarching objectives.

Stage 4: prepared the preliminary studies (architectural) and studies required during the implementation process (static adequacy study). The fourth stage constitutes the most technically intensive phase of the process. Building on the problems identified, the objectives defined, and ideas inspired by the Technical Best Practice Catalogue, this stage initiated the preparation and execution of all necessary technical studies required for the implementation of the interventions.

Stage 5: produced the final implementation plan through inclusive review and consensus-building among stakeholders, ensuring that proposed solutions addressed identified issues and met technical, economic, and social criteria. The preparation of the studies evolved into a structured process of dialog and consultation with all relevant stakeholders, who contributed by expressing their views, proposing innovative ideas, and critically assessing or rejecting certain existing proposals. This iterative and participatory approach led to the co-development of a final implementation plan, better aligned with the specific needs and priorities of the region, while maintaining a clear focus on achieving the defined objectives.

Stage 6: conducted the final implementation studies by experts, including engineers, architects, economists, and agronomists. The final implementation plan underwent a thorough review by experts, with the objective of assessing its feasibility and ensuring its economic and technical viability. During this evaluation process, the experts proposed and introduced the necessary adjustments and refinements, thereby enhancing the plan’s practicality and cost-effectiveness.

Stage 7: focused on evaluating the proposed interventions and their implementation approach, as outlined in the final implementation studies, in alignment with the KPIs, the principles of NEB, and the EHHUR methodology. The final stage focuses on the comprehensive evaluation of the implementation of the final plan. This is carried out by systematically comparing the achieved results against the predefined objectives and by analyzing the corresponding KPI calculations. In parallel, the extent to which the EHHUR methodology has been adopted is assessed through KPI-based measurements, while the degree of integration of the NEB principles within the implementation process is evaluated through the application of digital self-assessment tools.

The final stage of the project—although not included in the adopted and implemented methodology—involves the execution of the interventions and the comprehensive regeneration of the area. The

Figure 2 below illustrates the methodology as it was adopted, adapted, and implemented in the Kozani LH project.

2.3. Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

In alignment with the established methodology and with a specific emphasis on Step 7, the project implementation is evaluated through a comprehensive assessment framework that integrates both quantitative and qualitative approaches. This evaluation is based on a defined set of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), each linked to corresponding numerical or non-numerical targets, enabling a structured measurement of the project’s performance and overall impact. The extent to which these targets are achieved determines whether a project is deemed successful or not. The selection of KPIs followed a collective and highly participatory process, initiated through the development of an extensive database of monitoring indicators. This database was informed by relevant academic and technical studies [

26] as well as by the practical experience of project partners gained from the implementation of comparable initiatives. The final selection of KPIs was achieved through consensus among all participants, ensuring full alignment with the project’s objectives, strict adherence to the principles of the NEB, and sensitivity to the unique characteristics and contextual specificities of each Lighthouse.

In this context, 30 KPIs have been developed and organized into seven distinct categories, aligning with the core principles of NEB [

27]. The KPI categories are as follows [

27]:

Environmental KPIs: focus on both climate change mitigation action (reduction in emissions, planting of new trees, etc.), health and wellbeing inside the new constructions, and sustainable procurement.

Economic KPIs: focus on financial feasibility of the EHHUR renovation activities, with a particular interest in local business development and social return on investment

Energy KPIs: focus on energy saving, energy production from renewable sources at the building and district level, and sustainable mobility.

Social KPIs: focus on citizens’ engagement in EHHUR activities and participation in co-design activities. This aspect is fundamental in the NEB framework, and therefore a particular attention has been given to the accurate choice of the specific KPIs for each LH.

Cultural KPIs: among the social KPIs, a particular interest has been attributed to cultural events organized in the district affected by EHHUR renovation.

Beauty KPIs: focus on the esthetic of the solutions implemented in the district. “Beautiful” is, along with “sustainable” and “together”, one of the three pillars of the NEB compass.

Digital KPIs: focus on citizen involvement in the use of the new digital technologies that will be installed in the district areas, which will increase the level of automation of the buildings that will be renovated.

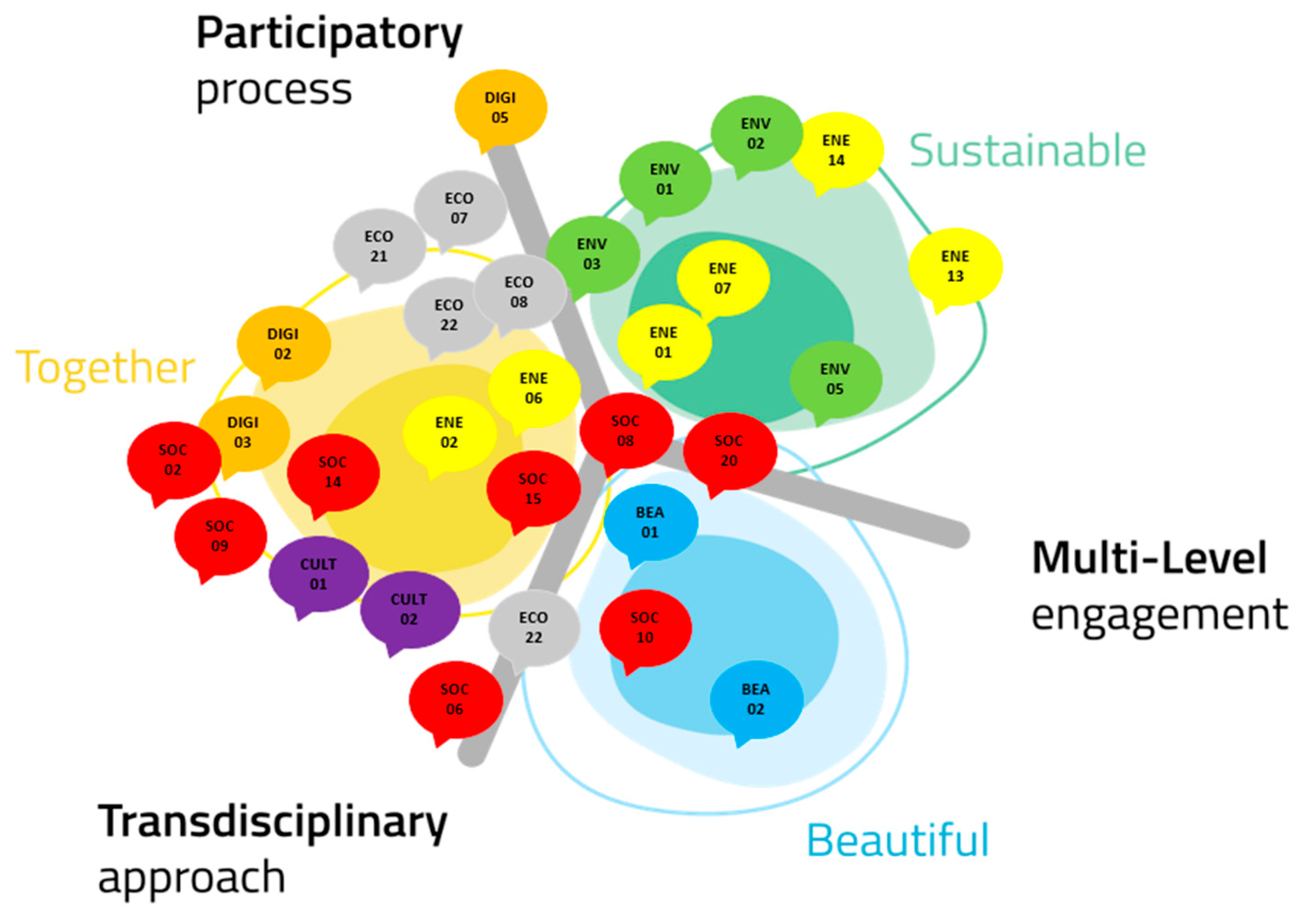

To ensure the evaluation is as objective as possible while also accounting for the unique characteristics of each LH, the developed KPIs were divided into two groups: common KPIs, applied across all LHs, and specific KPIs, tailored to the peculiarities of each LH. The

Table 1 below presents the complete list of KPIs, indicating their respective categories and specifying whether they are common or specific [

27].

One of the key considerations in developing these KPIs was their correlation and alignment with the values and working principles of NEB. As illustrated in the

Figure 3 below, the defined set of KPIs broadly encompasses the three core pillars of the NEB [

27].

3. Case Study of Kozani

3.1. Demonstration Area Description

The selected site for the Greek LH area in Kozani, designated for the implementation of the EHHUR project, possesses notable cultural, historical, and social relevance. The intervention area includes three buildings and a section of the adjacent Park of Agios Dimitrios. The project aims to holistically integrate the revitalization of an urban green space with the energy and esthetic retrofitting of key local infrastructures.

Firstly, the EHHUR project in the Kozani LH area prioritizes the comprehensive regeneration of Agios Dimitrios Park. Planned interventions will enhance the park’s visual character by accentuating its natural features, thereby contributing to the improvement of the area’s environmental and esthetic quality. Concurrently, energy-related enhancements will support the deployment of renewable energy technologies and promote partial energy autonomy within the park. On the social dimension, the project includes measures to improve physical accessibility and install user-centric public amenities—such as seating installations—to foster community engagement and reinforce the principles of inclusivity, collective use, and social cohesion.

Figure 4 illustrates the part of the park that will be renovated.

The second key element of the project entails the energy and architectural retrofitting of two primary school buildings. These upgrades are designed to enhance the buildings’ overall energy performance while simultaneously improving their visual and functional quality, both internally and externally. The scope of work includes implementing strategies to reduce energy demand, increase the integration of renewable energy sources, and achieve a degree of energy self-sufficiency. A particularly impactful—albeit less visually apparent—aspect of the intervention is the deployment of interactive educational screens. These systems serve an educational function by promoting environmental awareness and fostering core values such as energy efficiency and sustainability among students, who are viewed as the next generation of the citizens of Kozani.

Figure 5 presents an aerial perspective of the two primary school buildings.

The final part of the LH initiative focuses on the energy-efficient refurbishment of the Cultural Center of Kozani, the city’s tallest and one of its most architecturally prominent buildings. The planned interventions aim to significantly reduce the building’s energy demand through advanced envelope improvements and the integration of renewable energy systems, thereby facilitating partial energy autonomy. In parallel, the project envisions a comprehensive architectural redesign of the Cultural Center. The main objective is to transform the existing, visually obsolete structure into a modern civic landmark that contributes positively to the city’s esthetic and aligns with the urban design principles of the area.

Figure 6 represents the Cultural Center of Kozani.

3.2. Renovation Activities

In the previous chapter, a general overview of the planned interventions was provided. This chapter offers a more detailed background of the renovations to be undertaken in each part of the LH.

Park of Agios Dimitrios

The interventions planned for the Park constitute a multi-dimensional regeneration initiative, integrating environmental, spatial, and social design principles. These actions are distributed across various sectors and locations within the park to maximize systemic impact.

Key technical elements include the following:

- ▪

Mobility and Accessibility Improvements: Development of new and the rehabilitation of existing pedestrian pathways.

- ▪

Social Infrastructure: Installation of modular street furniture—including wooden platforms, benches, and other seating elements—to promote user interaction and strengthen social cohesion.

- ▪

Environmental Sustainability Measures:

- ○

Enhancement of existing water features.

- ○

Ecological landscape restructuring, including the reinforcement and spatial reorganization of vegetative zones to optimize microclimate regulation and biodiversity.

- ▪

Energy Efficiency and Renewable Integration:

- ○

Deployment of energy-autonomous smart benches.

- ○

Construction of a PV pergola to contribute to decentralized energy production.

- ○

Replacement of existing lighting infrastructure with high-efficiency luminaires to reduce energy demand and improve visual comfort.

- ▪

Cultural and Recreational Enhancements: Architectural transformation of the existing amphitheater and ancillary buildings, integration of outdoor exercise facilities, and redevelopment of the park segment adjoining the Church of Agios Christophoros, thereby enhancing both cultural utility and spatial quality.

Primary Schools Renovation

The renovation strategy for both Primary Schools is divided into three core domains:

- ▪

Energy Efficiency and Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ):

- ○

Application of high-performance thermal insulation to the building envelope, surpassing minimum regulatory thresholds.

- ○

Replacement of non-transparent external elements with advanced thermally insulated window and frame systems, in full compliance with thermal transmittance standards.

- ○

Retrofitting of lighting systems with LED technology resulting in substantial reductions in energy consumption and operational expenditure.

- ○

Installation of a comprehensive Building Energy Management (BEM) system, including smart metering and real-time environmental monitoring equipment.

- ▪

Architectural and Esthetic Enhancements: Renovation works, which are aimed at improving spatial comfort, visual appeal, and the integration of sustainable design principles in educational facilities.

- ▪

Behavioral Shift: The initiative involves the deployment of educational screens designed to disseminate content related to environmental awareness and energy efficiency. These screens will also provide real-time data visualizations of the buildings’ energy performance, enabling ongoing monitoring and analysis. In parallel, interactive educational robots will be introduced to convey similar content in an engaging and dynamic manner. The implementation and operation of these systems aim to enhance students’ understanding and familiarization with core principles such as sustainability, environmental responsibility, and energy conservation.

Cultural Center Retrofit

The retrofitting of the Kozani Cultural Center is structured into two distinct, yet interrelated, parts:

- ▪

Energy Performance Optimization:

An energy upgrade study forms the basis for this part, aiming to reduce the building’s operational energy demand, lower CO2 emissions, improve indoor air quality, and align with sustainable building standards, and proposing:

- ○

Thermal insulation of external walls and roof surfaces.

- ○

Replacement of existing frames with new high-efficiency systems.

- ○

Modernization of lighting and heating systems.

- ○

Installation of a mechanical ventilation system with heat recovery capabilities.

- ○

Integration of photovoltaic panels for on-site renewable energy generation.

- ○

Replacement of the heating and cooling system.

- ▪

Architectural and Visual Redevelopment:

An architectural study, to be developed in accordance with NEB principles and the methodological framework of the EHHUR initiative, will explore façade design enhancements, including

- ○

Integration of Building-Integrated Photovoltaics (BIPV).

- ○

Addition of vertical greenery systems and other bioclimatic design elements.

- ○

Formulation of additional design solutions by the architectural team during the final project elaboration phase.

3.3. Co-Design Activities

One of the main parameters in the successful implementation of the project—closely aligned with the core principles and values of the NEB—is the active participation and engagement of stakeholders and citizens throughout all phases of implementation. Their involvement in processes of co-ideation, co-design, co-decision-making, and co-creation has been instrumental in ensuring the project’s effective realization. This collaborative approach not only facilitated optimal design and execution but also enabled the identification and resolution of challenges encountered along the way.

Participatory Co-Design Framework

At the core of the engagement approach was a co-design model that facilitated synergies between citizen-generated insights and professional expertise. The model provided structured opportunities for residents to articulate needs, priorities, and design preferences, which were then synthesized and operationalized by architects, urban planners, and technical consultants. This participatory mechanism aimed to reinforce transparency, build institutional trust, and embed a sense of ownership across the community.

The strategy was executed through a four-phase engagement lifecycle: Initiation, Planning, Execution, and Replication, each corresponding to distinct stages of project development:

Public awareness and stakeholder activation were prioritized through large-scale outreach events where NEB principles (sustainability, inclusiveness, and esthetics) were contextualized for local application. This phase engaged diverse demographics, including municipal authorities, NGOs, students, and socially vulnerable groups.

- ▪

Planning Phase:

Participatory input collection was formalized through a series of co-design workshops, starting with high-visibility events and followed by targeted sessions with primary school students and educators. Concurrently, digital surveys and participatory diagnostics were employed to capture real-time feedback. Regular bilateral coordination meetings with project partners ensured continuous alignment between participatory outcomes and technical feasibility.

Engagement during implementation centered on validating and refining renovation activities based on prior participatory insights. Citizens contributed actionable proposals—such as integrating renewable energy technologies and prioritizing environmentally sustainable construction methods—that informed the evolving technical specifications. Monitoring surveys tracked early-stage impacts, particularly in the renovated schools and park areas. Both technical experts and community members structured ongoing engagement initiatives to support iterative validation of renovation deliverables.

- ▪

Replication Phase:

The final phase emphasizes the institutionalization and transferability of the participatory model. Best practices and strategic outcomes are being systematized for dissemination to national and EU-level stakeholders.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Evaluation of the Implementation Through KPIs

According to the methodology developed and analyzed in a previous chapter, 30 KPIs were identified to quantitatively and qualitatively assess the implementation of the project. These indicators are categorized into two groups: common and specific. The common indicators were monitored by all LH projects, while the specific indicators are tailored to the unique characteristics of each LH. In the case of Kozani, 23 KPIs were examined and monitored—18 of which are common, and 5 are specific to the local context. The KPIs relevant to the Kozani LH are presented in the following table (

Table 2).

Due to the diverse nature of the KPIs, various evaluation methods were used. These included conducting surveys with residents and stakeholders, collecting data from Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs), distributing and completing customized questionnaires, and other data collection and calculation methods. More specifically, the assessment and evaluation of indicators related to societal aspects (e.g., the use of electric vehicles—ENE 06) were carried out through targeted field surveys. Indicators addressing more qualitative dimensions, such as indoor climate conditions (ENV 02) or perceived esthetic value (BEA 01), were evaluated using structured questionnaires distributed either on-site or online and completed by relevant stakeholders. Accordingly, the evaluation of social indicators was based on the systematic documentation and analysis of social engagement activities. In contrast, the assessment of numerical energy and environmental KPIs relied on EPCs, technical studies, and data derived from the construction process, including material specifications, product labels, and technical manuals. Finally, the evaluation of economic KPIs was performed using a computational model developed within the EHHUR methodology, while the calculation of the SRI followed the standardized European computational framework. The following table (

Table 3) summarizes the evaluation methods applied and the specific KPIs that were calculated using each respective approach.

As previously noted, the project has introduced a new methodology for the implementation of interventions, which extends beyond the deployment of technical solutions to include a comprehensive set of complementary actions. These encompass not only technical measures but also activities related to information dissemination, awareness-raising, co-design, co-decision-making, and co-creation with local stakeholders. This holistic approach results in KPIs being influenced by the entire intervention process rather than by isolated, targeted actions. Naturally, the more technically oriented KPIs—particularly those related to energy performance and environmental impact—are directly affected by the implementation of specific technical measures within the intervention area. For example, energy retrofitting of buildings led to a reduction in energy intensity and GHG emissions, while simultaneously improving indoor air quality and thermal comfort, contributing positively to the relevant energy and environmental KPIs. In parallel, the installation of RES systems on buildings and PV facilities within the park area enhanced energy self-supply and increased the exploitation of PV availability.

In contrast, the social engagement activities implemented throughout the project demonstrated a substantial and positive influence on the KPIs associated with social cohesion, cultural value, and esthetic perception. These activities were instrumental in fostering community participation, enhancing public acceptance, and advancing the broader objectives linked to the non-technical KPIs. Social engagement actions were conducted across all phases of the project, beginning with co-ideation and co-design workshops during the initial stages and subsequently evolving into co-decision and co-creation initiatives. For each activity, stakeholder participation and thematic focus were systematically documented, while the outputs were thoroughly analyzed. These outputs essentially represent actionable solutions proposed for implementation. The outcomes of this participatory process are directly reflected in the Social and Cultural KPIs.

Finally, the adopted economic model supported the systematic estimation and calculation of the Economic KPIs, thereby integrating financial viability into the overall performance evaluation framework.

The table below (

Table 4) summarizes the target values set for each KPI and the corresponding levels achieved through the implementation of the project’s integrated approach.

As shown in the table above, the implementation of the proposed solutions has substantially contributed to the achievement of the project’s targets. From an environmental perspective, the implemented technical solutions and the adopted methodology proved to be highly effective. Annual CO2 emissions were significantly reduced, surpassing the predefined targets for each building individually. Moreover, issues previously identified by building users, particularly those concerning indoor climate conditions, were successfully addressed through the replacement of heating systems and the installation of Building Management Systems (BMSs). In parallel, the use of recycled and recyclable construction materials contributed to meeting sustainability objectives, while the horticultural study defined the renewal of trees and plant species in the park, thereby enhancing environmental resilience. From an economic standpoint, it is important to note that the evaluation does not solely focus on direct financial benefits but also incorporates social and environmental gains. This integrated approach ensured that all economic indicators presented positive outcomes, with the overall investment demonstrating a payback period of approximately five years. The assessment of the energy dimension yielded even more encouraging results. Energy consumption was reduced by more than 70%, while the energy intensity of the buildings exceeded the established targets by a substantial margin. The only deviation was observed in KPI ENE02, which measures the self-supply by RES. This deviation can be attributed to the specific urban characteristics of the area—namely, its dense urban fabric and central location—which rendered the deployment of additional RRES technically and spatially unfeasible. Nonetheless, the considerable reduction in overall energy demand mitigates the impact of not fully achieving this particular target. From a social perspective, the outcomes, as reflected in the SOC and CULT KPIs, clearly demonstrate the effectiveness of the methodology and its wide adoption. A particularly noteworthy finding is the high level of stakeholder participation in co-design and co-creation processes, ensuring inclusiveness across diverse social groups. Furthermore, all social engagement activities directly contributed to shaping the final implementation plan. The success of co-decision actions is evidenced by citizens’ overwhelmingly positive perception of the interventions’ esthetic and sensory qualities, as captured in the CULT KPIs. Finally, both the deployment of specific technical solutions (e.g., the installation of BEMS) and the project’s information and dissemination activities significantly contributed to advancing the digital transformation of the intervention area.

4.2. Evaluation of Application of NEB Methodology

The evaluation of a project’s implementation in accordance with NEB standards emphasizes the consistent application of the methodology across all phases of execution, with particular focus on the extent to which the initiative fulfills the ambitions of the core NEB values and working principles.

As presented in detail in a previous chapter, the methodology adopted for the implementation of the project in Kozani is based on the approach developed within the framework of the EHHUR project. This methodology fully aligns with the core principles and values of NEB, embodying its conceptual and operational framework throughout the project’s execution.

Throughout the implementation phase, the three fundamental pillars of the NEB were systematically integrated and guided the overall approach. The first pillar, “Sustainability”, was addressed through both technical and social dimensions. The ideas developed and the technical solutions incorporated into the final implementation plan were designed to reduce energy consumption and minimize the environmental footprint, while simultaneously increasing recycling and reuse rates and enhancing local biodiversity through targeted interventions, particularly within the park area. In parallel, social engagement actions focused on informing and raising awareness among citizens regarding sustainability, fostering behavioral change, and promoting habits such as energy conservation, environmental stewardship, recycling, and material reuse. Moreover, the execution of technical interventions adhered to principles of green procurement and prioritized the use of recycled and recyclable materials, further reinforcing the sustainability agenda. The second pillar, “Beautiful”, was embedded in both the design process and its outcomes. On the one hand, the technical solutions included in the implementation plan were the result of co-decision processes, ensuring that stakeholders and citizens alike perceived the outcomes as esthetically meaningful, familiar, and representative of their active contribution to shaping the area. On the other hand, participatory activities fostered collective experiences, co-creation, and a strong sense of belonging to a shared community with a common goal of reshaping and regenerating the neighborhood. These actions strengthened social cohesion, cultivated a sense of belonging, and reinforced the intrinsic link between esthetics and inclusiveness in urban transformation. The third pillar, “Together”, was reflected in the extensive participatory framework implemented across all stages of the project. The inclusive design of engagement processes ensured the involvement of diverse social groups, thereby promoting equality and embedding social justice into the regeneration effort. The co-decision outcomes not only enriched the quality and relevance of the technical solutions but also prioritized accessibility and inclusivity, with a particular focus on meeting the needs of disadvantaged and vulnerable groups.

The adoption and implementation of this model introduced an alternative paradigm for executing urban retrofitting and regeneration projects—markedly distinct from conventional practices (BAUs), creating opportunities but also raising obstacles, which, however, constitute a good lesson and a roadmap for how such projects can be implemented more easily and effectively in the future.

Opportunities

- ▪

Working across levels and being interdisciplinary: Familiarization with new, advanced, innovative materials and technologies aimed at enhancing building renovation processes and the sustainable regeneration of open public spaces.

- ▪

Stakeholders and citizens engagement:

- ○

Enhanced identification and analysis of the area’s challenges and needs to ensure that proposed interventions are context-specific, demand-driven, and capable of addressing real, site-specific issues with maximum effectiveness.

- ○

Generation of new ideas/concepts through participatory processes involving stakeholder interaction, knowledge exchange, and collaborative ideation.

- ○

Establishment of objective evaluation mechanisms, whereby stakeholder feedback and insights serve as critical inputs in assessing project performance and determining the overall success of the implementation.

Obstacles

- ▪

Legislative and tendering:

- ○

In accordance with the current Greek legislative framework, regulatory challenges arise concerning interventions in public buildings and the renovation of open public spaces. Notably, the absence of a dedicated legal structure to support extensive citizen participation in such projects constitutes a significant limitation.

- ○

Public procurement and tendering procedures are characterized by high levels of administrative complexity and duration, often resulting in considerable delays in project implementation timelines.

- ▪

Mindset: Although the implementation of the EHHUR project and the execution of its interventions led to visible transformations—prompting citizens and stakeholders to increasingly recognize the significance and potential impact of such initiatives—a degree of apprehension toward innovation and systemic change remains. Many residents continue to exhibit a reliance on conventional renovation and regeneration practices, indicating the persistence of limited readiness to adopt non-traditional, forward-looking approaches.

- ▪

Stakeholders and citizens engagement: Ensuring continuous and active citizen engagement in co-ideation, co-design, and co-decision-making activities presents significant challenges. It requires structured facilitation, strategic communication, and adaptive stakeholder management to build trust, overcome participation weariness, and effectively motivate broad-based involvement across diverse population groups.

After applying the methodology and carrying out the interventions in the Kozani LH, the project was evaluated. The evaluation was based on the core values and working principles of the NEB and is defined by the following key dimensions [

28]:

NEB Values

- ▪

Beautiful: The LH area buildings are being upgraded both esthetically and energetically, with façade enhancements that respect their architectural character and energy measures that improve indoor comfort, air quality, lighting, and acoustics. In parallel, the park’s redevelopment will create an inclusive, green public space that promotes recreation, relaxation, and community engagement. (Ambition I—to activate)

The park’s renovation transforms it into an attractive and inclusive space where local residents can meet, spend quality time, engage in dialog, and share collective experiences. At the same time, the renovation initiatives offer valuable opportunities for interaction, enhancing the exchange of ideas and mutual understanding, while the organization of community-focused activities—such as tree planting events involving both students and interested citizens—will help to cultivate a sense of belonging and reinforce the values of collectivism and cooperation. (Ambition IΙ—to connect)

- ▪

Sustainable: The interventions aim to reduce primary energy consumption and integrate renewable energy systems. These measures will also lower emissions, decrease energy waste, and reduce the carbon footprint. Environmental benefits will be further supported by tree planting and the use of pathways from permeable materials. (Ambition I—to repurpose)

Throughout the planning, implementation, and maintenance phases of the interventions, recycled and recyclable materials are and will be utilized. All necessary procedures are carried out in accordance with green procurement standards, focusing on the efficient management of waste, the reuse of materials, and the reduction in energy consumption. (Ambition IΙ—to close the loop)

The proposed renovations will play a key role in the comprehensive revitalization of the park and the whole area. These efforts involve introducing new species of trees and shrubs while preserving the existing vegetation, aiming to boost local biodiversity. Simultaneously, the park’s overall esthetic will undergo a complete transformation, with the natural landscape being extended and enhanced. (Ambition IΙI—to regenerate)

- ▪

Together: The planned interventions aim to guarantee that both the park and its buildings are fully accessible to all residents of Kozani. Specially designed pathways will be incorporated into the park, and ramps will be added to the buildings to accommodate individuals with mobility challenges. Both the park and the buildings will remain open and freely available for use by all members of the local community. (Ambition I—to include)

NEB Working Principles

- ▪

Participatory process: During the implementation of the project, a range of activities was carried out to keep all stakeholders informed about the progress of the renovation works and to introduce them to the principles of the NEB. At the same time, teams of engineers and architects prepared studies outlining proposed actions and solutions for the holistic regeneration of the area. (Ambition I—to consult)

During the planning phases, co-design activities engaged students, residents, and stakeholders to identify issues, propose solutions, and participate in decision-making for renovations. Participatory processes were held at schools, the park, and the Cultural Center, supported by surveys and dialog to ensure widely supported, user-informed improvements. (Ambition IΙ—to co-develop)

- ▪

Multi-level engagement: Local collaborative networks were formed and activated, fostering partnerships between project stakeholders and community actors who played an active role in both the design and execution of the interventions. Local engineers and architects contributed to the development of renovation plans for the Cultural Center, while dedicated working groups supported the energy efficiency upgrades and esthetic improvements of the school buildings. (Ambition I—to work locally)

During the implementation, the network of collaborations expanded to meet emerging needs. New partnerships were formed with engineers and architects from outside the local community to support the park’s regeneration. At the same time, the pursuit of innovative, modern, and cost-efficient materials prompted the exploration of new markets and the creation of broader networks extending beyond the region. (Ambition IΙ—to work across level)

- ▪

Transdisciplinary approach: Professionals from diverse fields contributed throughout all project phases. Engineers, architects, and agronomists led technical and landscape planning; social scientists facilitated stakeholder engagement; economists developed a sustainable business plan; and administrative staff ensured procedural efficiency. Local workers, including teachers and Cultural Center staff, played a key role in identifying challenges and shaping effective solutions. (Ambition I—to be multidisciplinary)

The professionals involved not only contributed their expertise but also gained knowledge by engaging with innovative ideas and integrating NEB principles and EHHUR methodology into their practices. The project introduced advanced technologies, best practice catalogs, and access to new markets, promoting sustainability, beauty, and togetherness while enhancing professional development. (Ambition II—to be interdisciplinary)

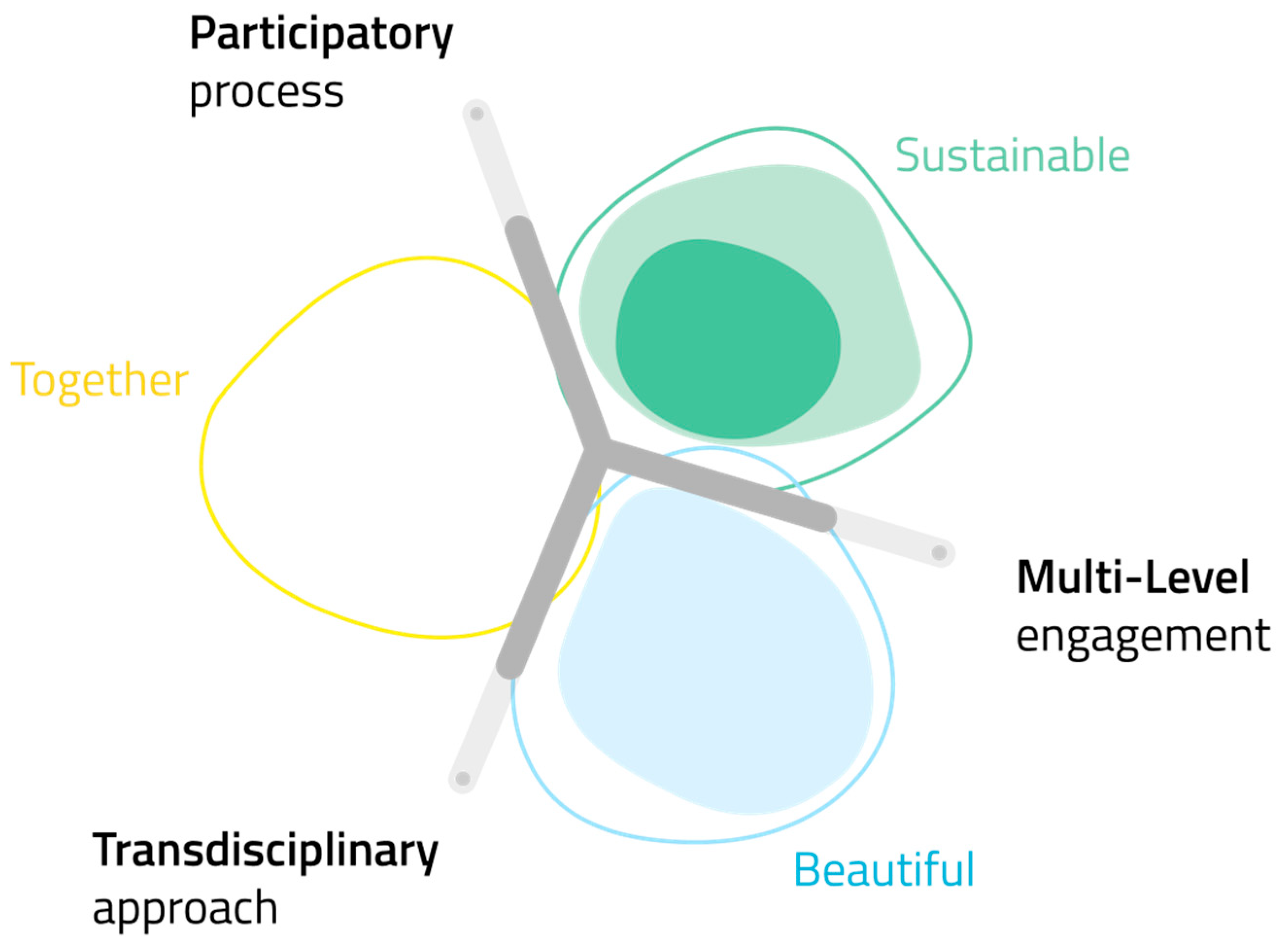

The evaluation of the project within the framework of NEB is clearly illustrated in the following figure (

Figure 7). It showcases the ambitions realized through the implementation of the EHHUR initiative in the area of Kozani, emphasizing their alignment with the fundamental values and guiding principles of the NEB.

4.3. Comparative Analysis with the Other LHs of the Project

As previously noted, the EHHUR initiative encompasses seven distinct intervention areas, one of which is Kozani. While the specific characteristics and objectives of each area differ, a common methodological framework and the shared adoption of NEB principles guide the implementation of all projects. The first intervention area, Høje-Taastrup in Denmark, focuses on the establishment of a Renewable Energy Community (REC), where the primary stakeholders and beneficiaries are the residents of the area, which largely comprises social housing. The interventions include the energy and esthetic renovation of housing facilities and the use of recyclable and reusable materials derived from construction and demolition waste. Strong emphasis is placed on inclusion and affordability, reflecting the socio-economic profile of the residents, alongside the integration of sustainable solutions through the broader adoption of RES technologies. The second intervention area, Zoersel in Belgium, involves the comprehensive renovation of a former municipal library, which is being repurposed as both a library and a social housing facility. In parallel, procedures are underway to establish a REC. Implementation efforts focus on the adaptive reuse of the building, transforming it into an inclusive, welcoming, and sustainable space for residents and visitors, while also fostering behavioral change among citizens and enhancing collective awareness on issues of collaboration and community building. The third intervention area, Maia in Portugal, shares many similarities with the Danish case, as it also centers on a social housing neighborhood while simultaneously seeking to establish an Energy Community. Given that vulnerable groups predominantly inhabit the area—including the elderly and unemployed—the primary objective is to ensure the development of a financially viable and socially inclusive living environment. A key success of this initiative has been the active engagement of residents in participatory processes, enabling them to decision-making processes regarding the future development of their community. The fourth intervention area, Izmir in Turkey, represents a unique case, as it is situated in a location of significant historical and cultural importance. The main objective is the construction of a new multifunctional building, a process that has entailed substantial challenges. These include securing the necessary permits and approvals, obtaining citizen consent for interventions in a sensitive area, and achieving an architectural design that aligns with and respects the historic, cultural, and social character of the surrounding environment. The fifth intervention area, Osijek in Croatia, is characterized primarily by open public spaces, such as parks and streets. Regeneration efforts are directed toward their transformation into more accessible, inclusive, and esthetically enhanced urban environments, fostering opportunities for citizens to interact, exchange ideas, and strengthen community ties. Finally, the sixth intervention area, Biodistretto in Italy, focuses on the energy and esthetic renovation of an elderly center and the establishment of an Energy Community. These interventions aim to create a more accessible, comfortable, and attractive environment for elderly residents, while simultaneously contributing to the sustainability and affordability of the broader district.

It is evident that each Lighthouse presents its own particularities, making none directly comparable to the case of Kozani. Nevertheless, several common denominators emerge across all implementations: the active involvement of stakeholders, the participation of citizens in co-decision and co-creation processes, the emphasis placed on the core pillars of NEB, and most importantly, the systematic application of the methodology developed within the project framework. In certain LHs, such as those in Denmark and Belgium, citizen engagement in co-decision and co-creation activities was particularly strong—largely attributed to the prevailing civic culture and participatory mindset. By contrast, in Kozani, greater emphasis was placed on sustainability measures and energy efficiency interventions. A recurring theme across multiple LHs—specifically the Belgian, Danish, Italian, and Portuguese cases—was the establishment of Energy Communities, a holistic solution that inherently integrates the three NEB pillars: Beautiful, Sustainable, and Together. Equally noteworthy is the strong focus on vulnerable social groups, which varies according to the local context: children in Kozani, elderly populations in Biodistretto, and the unemployed in Maia. Finally, particular attention was devoted to the regeneration of open public spaces, a dimension that proved central in several LHs and was especially pronounced in Osijek and Kozani, where the reconfiguration of parks and communal areas became a pivotal element of the interventions.

4.4. Lessons Learnt

The implementation of the project in the intervention area of Kozani, in contrast to the conventional Business-As-Usual approach, applied the methodology developed within the framework of EHHUR and consistently adhered to the principles and values of NEB. This approach resulted in the establishment of a new model for regional regeneration projects, primarily grounded in the lessons learned throughout the process.

Perhaps the most critical lesson is the active and continuous involvement of stakeholders across all phases of implementation. Stakeholders are uniquely positioned to identify and articulate the real problems of an area, while also contributing valuable insights and envisioning solutions that best address their needs. Within this context, fostering stronger relationships among stakeholders, as well as between stakeholders and the implementing authorities, emerges as a fundamental prerequisite. Furthermore, the creation of effective incentives is essential to broaden citizen participation and strengthen engagement in co-design and co-creation processes. Another key insight relates to the necessity of comprehensive preparation. The successful implementation of urban regeneration initiatives under the NEB framework requires thorough preparatory work to mitigate delays arising from bureaucratic, tendering, or procurement processes. Enhanced coordination and cooperation among all involved entities can further reduce setbacks and improve procedural efficiency. Finally, with regard to the final stage of implementation, the development of a comprehensive and integrated plan is indispensable. Such a plan should encompass not only the technical design of the interventions but also the economic model and the social inclusion roadmap to be pursued, fully aligned with the EHHUR methodology. This integrated approach ensures both the acceleration and the effectiveness of implementation, thereby maximizing the long-term impact of the interventions.

4.5. Policies Recommendation

Urban regeneration in Europe is increasingly shaped by the need to enhance environmental performance, strengthen social inclusion, and improve economic resilience, while ensuring that solutions remain sensitive to local contexts. Achieving these objectives requires coordinated action across multiple governance levels—municipalities, regional authorities, national governments, and EU institutions. Equally critical are integrated methodologies that combine robust technical analysis with meaningful stakeholder engagement, sound financial planning, and systematic knowledge exchange.

The case of Kozani and more broadly the EHHUR project illustrates how these challenges can be addressed through a structured methodology, resulting in seven key recommendations for decision-makers at different levels of governance:

Adopt structured co-creation frameworks. Formalize community participation within urban planning and public procurement processes to ensure that interventions respond to local needs and secure public legitimacy from the outset.

Map and prioritize stakeholders. Apply systematic stakeholder mapping to identify, engage, and prioritize relevant actors—from institutional bodies to grassroots organizations—thereby increasing both the inclusiveness and the effectiveness of decision-making.

Establish long-term sustainable financing strategies. Design resilient financial models that blend public, private, and community-based resources with circular procurement practices, ensuring both economic viability and local environmental benefits.

Integrate socio-economic and technical assessments. Evaluate proposed interventions not only in terms of technical performance and cost but also through their social value and environmental impact, promoting solutions that are both sustainable and broadly accepted.

Pilot and scale interventions through living labs. Implement small-scale, real-world pilot projects as testbeds to validate technical and social feasibility, refine solutions, and inform regulatory and policy frameworks before broader deployment.

Create replication networks and evidence repositories. Establish structured platforms and open-access databases that allow cities to exchange proven solutions, share datasets, and disseminate lessons learned, thereby accelerating innovation and reducing duplication.

Raise awareness and improve energy literacy. Strengthen citizen and institutional capacity through targeted awareness campaigns, training, and user-friendly tools, empowering stakeholders to better understand energy demand, efficiency, and savings.

5. Conclusions

The declaration of the NEB as an official initiative of the European Union, coupled with the systematic integration of its principles and values into diverse methodological models and their application across projects, has introduced an innovative paradigm for urban regeneration. Within this framework, the EHHUR project has been a pioneering effort, developing an implementation methodology explicitly grounded in the values and operational principles of the NEB. This approach redefined not only the execution of interventions and the delivery of technical solutions but also the entire process—from the identification of real, community-experienced problems, to the co-creation of solutions, and ultimately to their long-term utilization and impact. Central to this methodology were participatory practices, including co-design, co-decision, and co-creation activities, ensuring the active involvement of all stakeholders and citizens throughout the project lifecycle.

In Kozani, this methodology was applied to a large-scale urban regeneration project aimed at achieving energy, esthetic, and digital upgrades in three public buildings (two primary schools and the Cultural Center), alongside the comprehensive revitalization of Agios Dimitrios Park. The evaluation of this implementation rests on three key criteria. First, the degree of adherence to the innovative EHHUR methodology, which was fully adopted and operationalized in Kozani through the systematic application of the project’s guidelines, recommendations, and best practice catalogs. Second, the assessment of Key Performance Indicators and their associated targets, the majority of which were successfully achieved, demonstrating the effectiveness of both technical and social interventions. Third, the extent of integration of NEB values and principles into the implementation process, where Kozani presents particularly noteworthy results, reaching the adoption levels initially envisaged and aligning closely with the project’s ambitions.

The findings from Kozani confirm that the developed methodology is highly effective, both in terms of achieving predefined objectives and in ensuring robust stakeholder participation in co-creation processes. Moreover, the approach demonstrates full alignment with NEB principles, thereby setting a new standard for future urban regeneration initiatives. The lessons learned, challenges addressed, and limitations encountered constitute valuable inputs for refining the methodology and strengthening the implementation framework. At the same time, the policy recommendations derived from the project provide guidance at the political and legislative levels, creating more favorable conditions for the replication and scaling-up of similar interventions.

As one of the first European projects to explicitly combine urban regeneration with the principles of the NEB, EHHUR—and specifically the Kozani case—illustrates the potential of this methodology as a reference model. The demonstrated effectiveness, together with the knowledge generated, positions Kozani as a benchmark example for future projects across Europe seeking to bridge sustainability, inclusivity, and esthetics within the NEB framework.