The Impact of Digital Governance on Energy Efficiency: Evidence from E-Government Pilot City in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Policy Background and Research Hypothesis

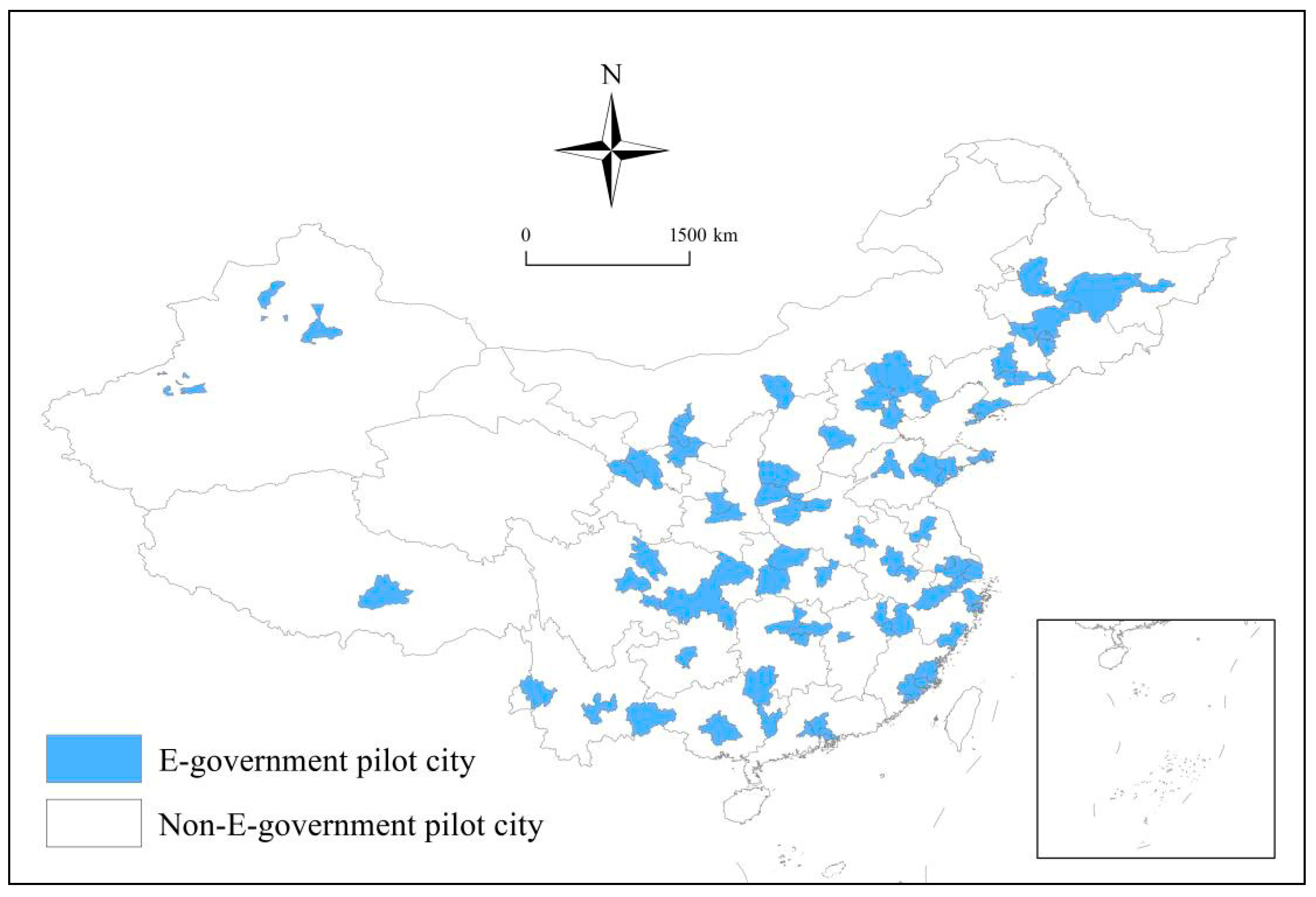

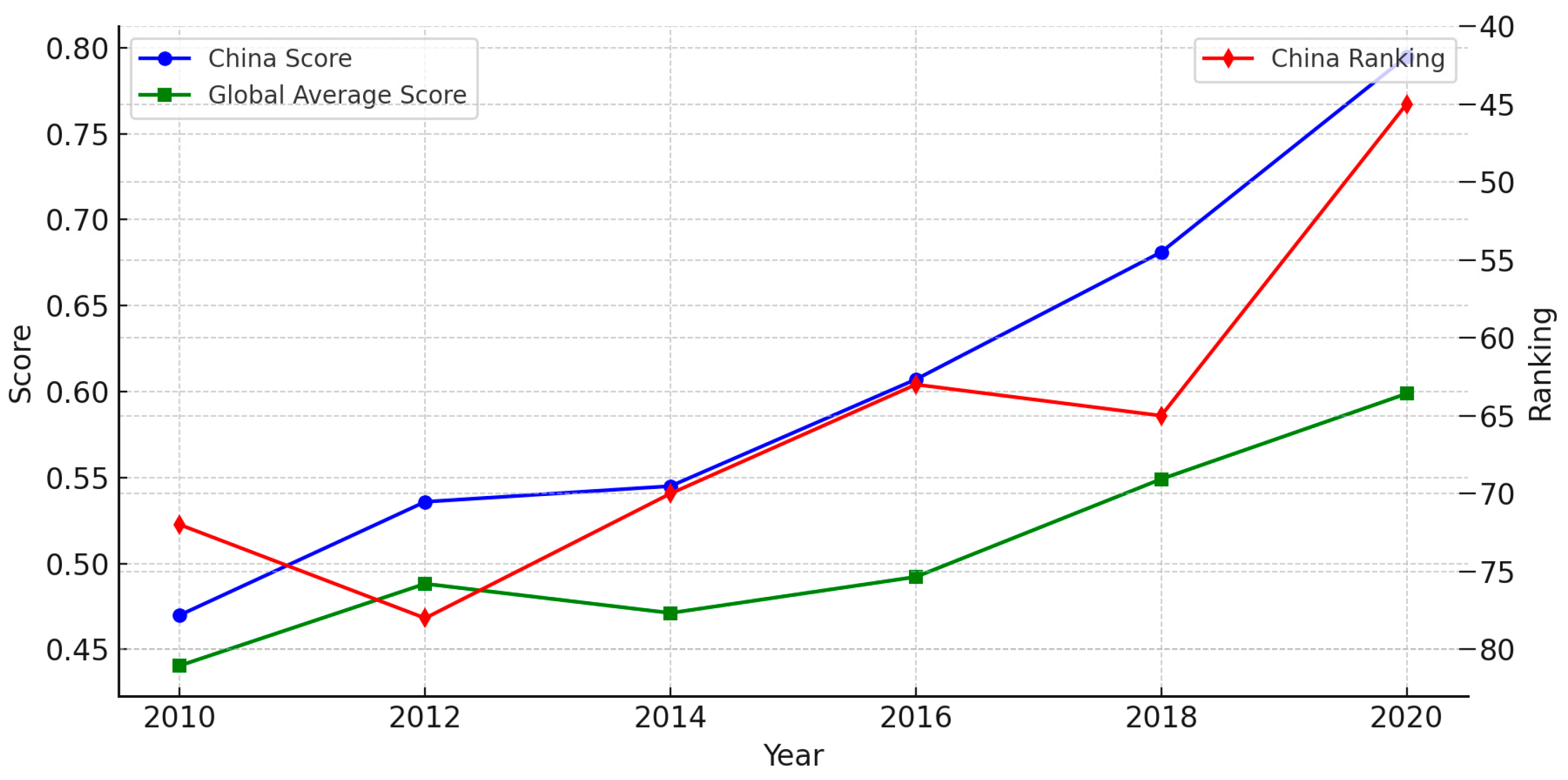

2.1. The EPC Policy

2.2. Research Hypothesis

2.2.1. Industrial Structure Upgrades

2.2.2. Green Technology Innovation

2.2.3. Foreign Direct Investment

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

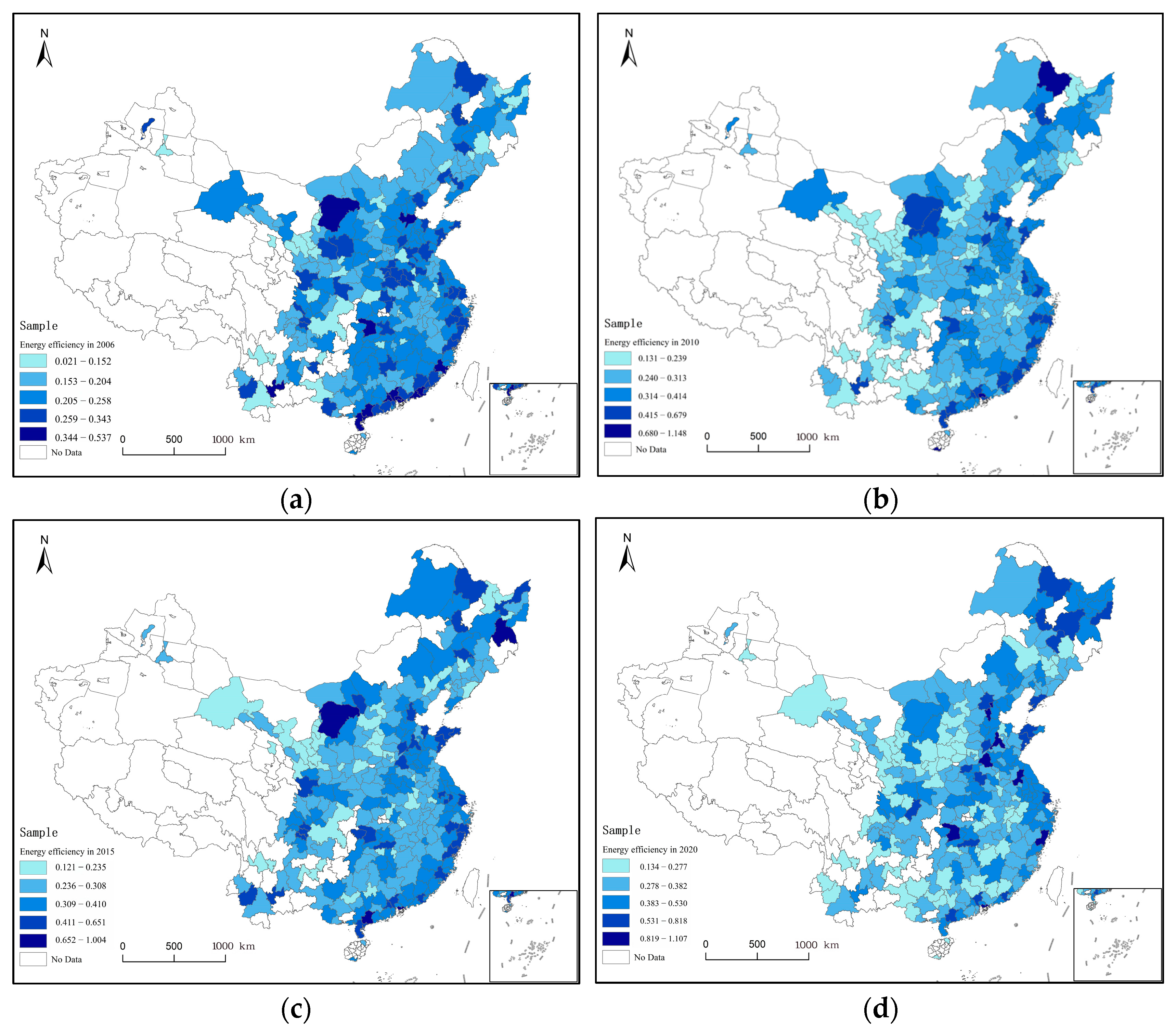

3.2. Variable Selection

3.3. Empirical Strategy

3.3.1. Baseline Model: DID Approach

3.3.2. Mediating Effect Model

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Regression

4.2. Robustness Tests

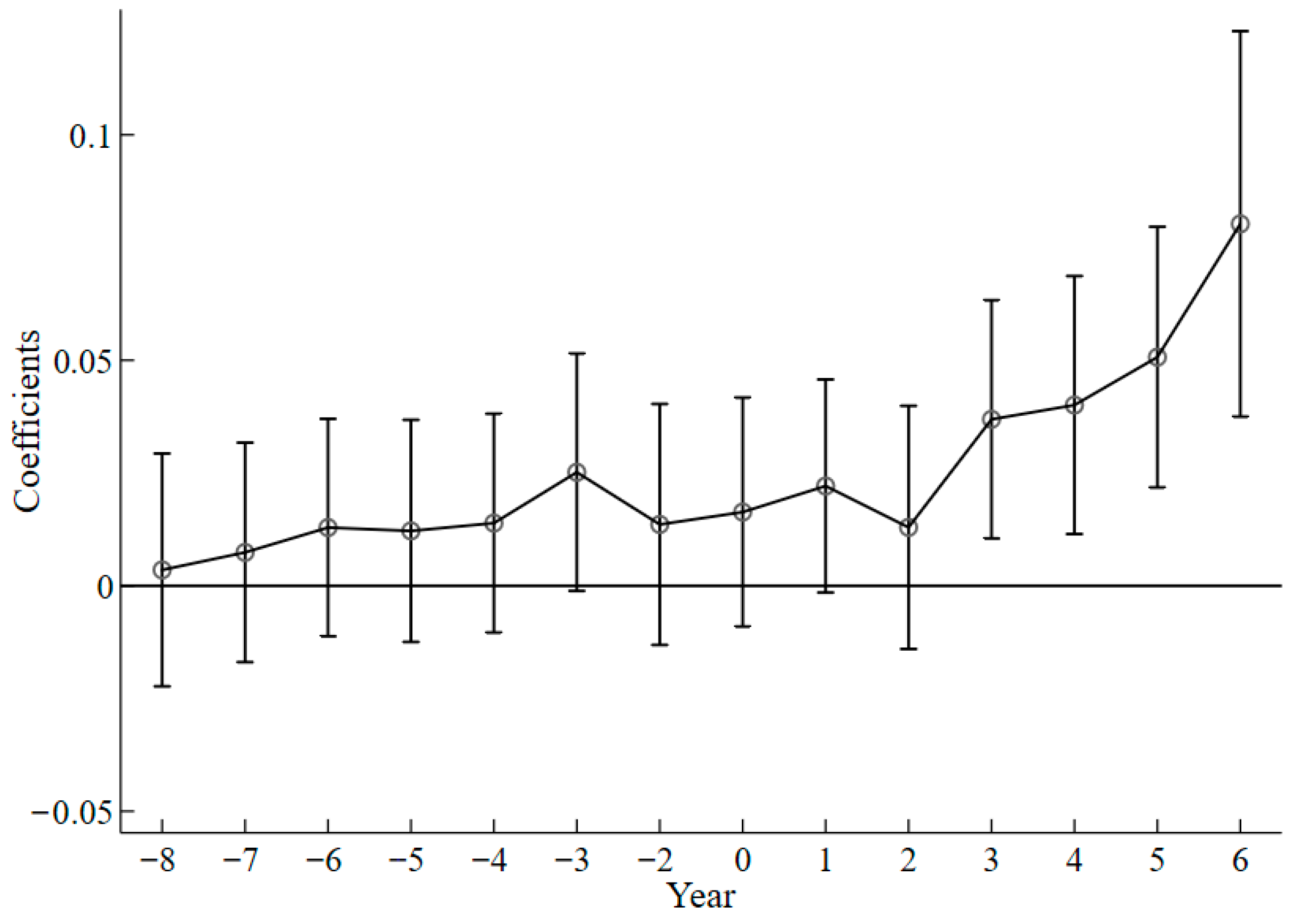

4.2.1. Parallel Trend Tests

4.2.2. Applications of Synthetic DID

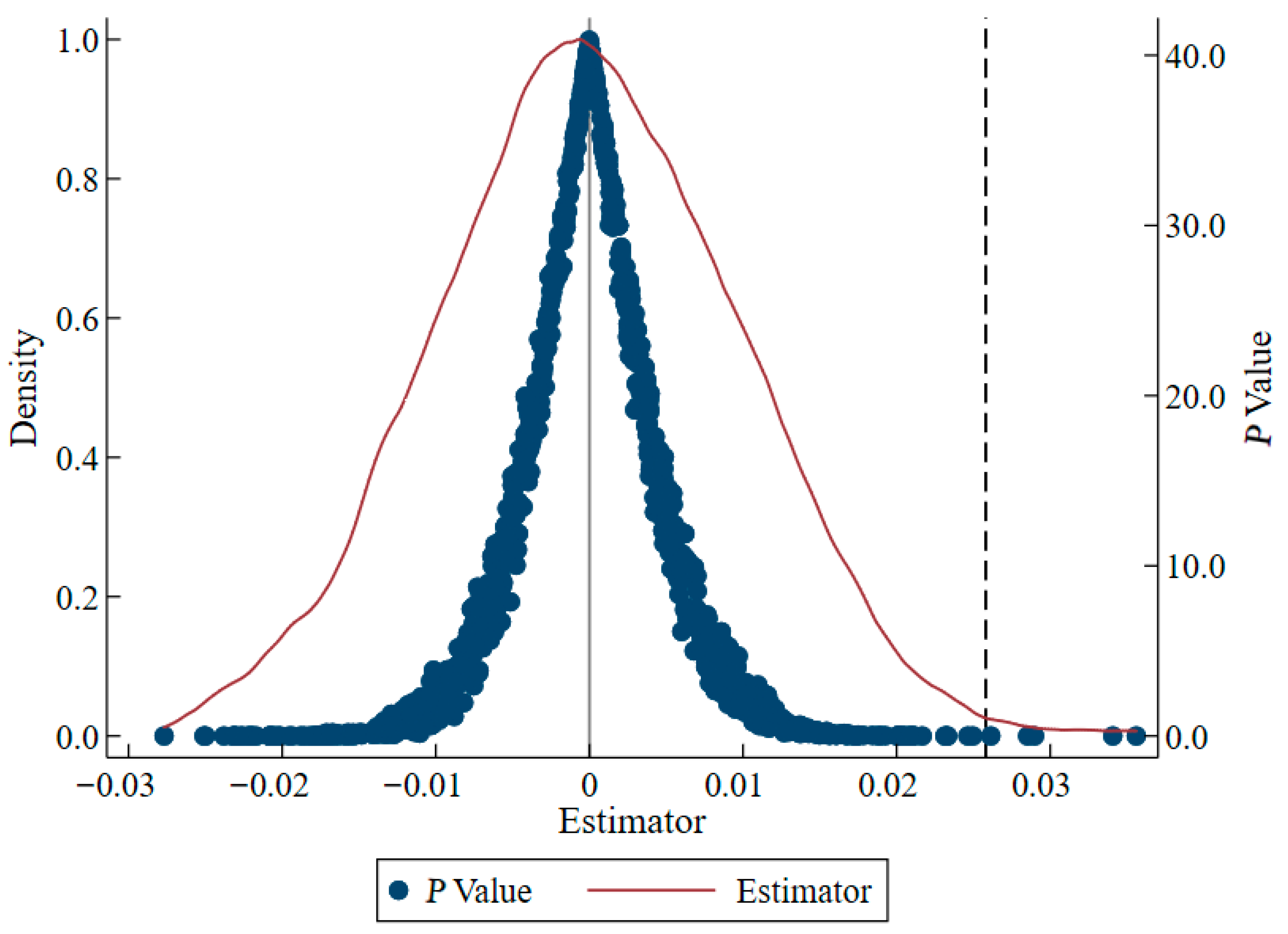

4.2.3. Placebo Test

4.2.4. Additional Robustness Checks

4.3. Mechanism Tests

4.3.1. Facilitating Industrial Structure Upgrades

4.3.2. Promoting Green Technology Innovation

4.3.3. Attracting Foreign Direct Investment

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.4.1. City Characteristics

4.4.2. Institutional Environment

4.4.3. Infrastructure Development

5. Further Studies: Analysis of Spatial Spillover Effects

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Research Conclusions

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Theoretical Implications

6.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Website Performance | Digital Governance Focus | Base-Station Counts |

| EPC | 0.381 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.013 *** |

| (0.029) | (0.000) | (0.001) | |

| City FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | −1.891 * | −0.001 ** | −0.497 *** |

| (0.986) | (0.001) | (0.096) | |

| R2 | 0.455 | 0.4220 | 0.525 |

| N | 4230 | 4023 | 4230 |

Appendix B

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | University Student | Technical Staff | Industrial Wastewater | Industrial SO2 | Industrial NOx |

| EPC | 0.026 *** (0.006) | 0.003 *** (0.001) | −0.120 *** (0.032) | −1.758 *** (0.237) | −2.839 ** (1.131) |

| City FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 0.096 (0.164) | 0.044 (0.027) | 2.384 *** (0.913) | −19.289 ** (8.484) | 56.809 (37.457) |

| R2 | 0.905 | 0.592 | 0.805 | 0.771 | 0.358 |

| N | 4230 | 4035 | 4230 | 4230 | 4230 |

References

- World Energy Outlook. 2023. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2023 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Wang, L.H.; Shao, J. Digital economy, entrepreneurship and energy efficiency. Energy 2023, 269, 126801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.Y.; Sun, W.X.; Meng, P.P.; Miao, Y.; Wen, X. How does China’s digital economy affect green total factor energy efficiency in the context of sustainable development? Sustainability 2025, 17, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.R.; Yuan, C.L.; Xu, J.R. The impact of digital government on energy sustainability: Empirical evidence from prefecture-level cities in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 209, 123776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.Z.; Sinha, A.; Hu, K.X.; Shah, M.I. Impact of technological innovation on energy efficiency in industry 4.0 era: Moderation of shadow economy in sustainable development. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 164, 120521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.G.; Zhu, J. Industrial restructuring, energy consumption and economic growth: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 335, 130242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.D.; Yu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.Q.; Chen, X.D. Industrial agglomeration and energy efficiency: A new perspective from market integration. Energy Policy 2023, 183, 113793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Mu, R.Y.; Zhan, Y.F.; Yu, J.H.; Liu, L.Y.; Yu, Y.S.; Zhang, J.X. Digital economy, energy efficiency, and carbon emissions: Evidence from provincial panel data in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 852, 158403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Liu, Y.B.; Chen, P.F.; Zeng, M.L. Assessing the impact of digital economy on green development efficiency in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Energy Econ. 2022, 112, 106127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xiao, W.W.; Bai, C.Q. Can renewable energy technology innovation alleviate energy poverty? Perspective from the marketization level. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, E.D.; Rousaki, A. Reconsidering government digital strategies within the context of digital inequalities: The case of the UK Digital Strategy. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, R. Cloud computing in Singapore: Key drivers and recommendations for a smart nation. Politics Gov. 2018, 6, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Government, Local Government Denmark & Danish Regions. A Stronger and More Secure Digital Denmark: Digital Strategy 2016–2020; Agency for Digitisation: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016.

- Ali, M.A.; Hoque, M.R.; Alam, K. An empirical investigation of the relationship between e-government development and the digital economy: The case of Asian countries. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 1176–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Dong, S.Y.; Huang, Y.X. Government digital governance and urban green economic efficiency in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 392, 126686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwilinski, A.; Lyulyov, O.; Pimonenko, T. The impact of digital business on energy efficiency in EU countries. Information 2023, 14, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Li, H. Can digital technology innovation promote total factor energy efficiency? Firm-level evidence from China. Energy 2024, 293, 130682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, I.; Guarini, G.; Laureti, T. Digitalization in Europe: A potential driver of energy efficiency for the twin transition policy strategy. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2023, 89, 101701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.R.; Chang, X.Y.; Zhu, J.N. How does the digital economy affect energy efficiency? Empirical research on Chinese cities. Energy Environ. 2024, 35, 1703–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Li, W.; Hu, J.; Ren, Y. Can government digital transformation improve corporate energy efficiency in resource-based cities? Energy Econ. 2025, 141, 108043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.Q.; Huang, C.C. Nonlinear relationship between digitization and energy efficiency: Evidence from transnational panel data. Energy 2023, 276, 127601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.G.; Zhu, Z.X. The impact of digital governance on urban carbon emissions: Quasi-natural experimental evidence based on “National pilot policy of information benefiting the people”. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 500, 145287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, T.; Zhang, M.X.; Zhang, Z.Q. The impact of digital government policy on entrepreneurial activity in China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 79, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notice on Accelerating the Implementation of Information Benefiting People. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xxgk/moe_1777/moe_1779/201401/t20140120_162796.html (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Notice on Approving the Designation of Shenzhen and 79 Other Cities as National Information Benefiting the People Pilot Cities. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/zcfb/tz/201406/t20140623_964160.html (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Du, P.; Yu, S.Y.; Yang, D.L. The development of e-governance in China: Improving cybersecurity and promoting informatization as means for modernizing state governance. In Research Series on the Chinese Dream and China’s Development Path; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Chao, W.M.; Mbanyele, W.; Zhu, B.C.; Huang, H.Y. From pilot to peers: How intelligent manufacturing policy drives corporate intelligent transformation through demonstration effects. Econ. Model. 2025, 152, 107292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainey, H.G. Understanding and Managing Public Organizations; Jossey-Bass: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Edler, J.; Georghiou, L. Public procurement and innovation—Resurrecting the demand side. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 949–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbanyele, W.; Huang, H.Y.; Muchenje, L.T.; Zhao, J. How does climate regulatory risk influence labor employment decisions? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment. China Econ. Rev. 2024, 87, 102236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margetts, H.; Dunleavy, P. The second wave of digital-era governance: A quasi-paradigm for government on the Web. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2013, 371, 20120382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.M.; Li, H.Q.; Xu, C.; Zhao, X.Y.; Zheng, Z.X.; Li, Y.S.; Liu, W. Impacts of industrial structure adjustment, upgrade and coordination on energy efficiency: Empirical research based on the extended STIRPAT model. Energy Strategy Rev. 2022, 43, 100911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Kuk, G. The challenges and limits of big data algorithms in technocratic governance. Gov. Inf. Q. 2016, 33, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Pardo, T.A.; Nam, T. What makes a city smart? Identifying core components and proposing an integrative and comprehensive conceptualization. Inf. Polity 2015, 20, 61–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Linde, C.V.D. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.H.; Yi, N.; Zhang, L.; Li, D.Y. Does institutional pressure foster corporate green innovation? Evidence from China’s top 100 companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 188, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergel, I.; Edelmann, N.; Haug, N. Defining digital transformation: Results from expert interviews. Gov. Inf. Q. 2019, 36, 101385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish; Khan, S.; Haneklaus, N. Sustainable economic development across globe: The dynamics between technology, digital trade and economic performance. Technol. Soc. 2023, 72, 102207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Helbig, N.; Ojo, A. Being smart: Emerging technologies and innovation in the public sector. Gov. Inf. Q. 2014, 31, I1–I8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Wallis, J.; Singh, M. E-government development and the digital economy: A reciprocal relationship. Internet Res. 2015, 25, 734–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, J.B.; Lu, J.X. China’s outward foreign direct investment in the belt and road initiative: What are the motives for Chinese firms to invest? China Econ. Rev. 2021, 68, 101628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Crescenzi, R. Research and development, spillovers, innovation systems, and the genesis of regional growth in Europe. Reg. Stud. 2008, 42, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, R.; Neumayer, E. Geographic variations in the early diffusion of corporate voluntary standards: Comparing ISO 14001 and the Global Compact. Environ. Plan. A 2010, 42, 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, T.H. How does FDI affect host country development? Using industry case studies to make reliable generalizations. In Does Foreign Direct Investment Promote Development; Center for Global Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 281–313. [Google Scholar]

- Mbanyele, W.; Huang, H.Y.; Liu, Y.; Qu, X.W. Foreign bank entry and corporate emissions: Evidence from staggered deregulations in China. J. Multinatl. Financ. Manag. 2025, 79, 100919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiding Opinions of the State Council on Strengthening the Construction of Digital Government. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2022-06/23/content_5697299.htm (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- IPC Green Inventory. Available online: https://www.wipo.int/classifications/ipc/green-inventory/home (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Easy Professional Superior (EPS) Data Platform. Available online: https://www.epsnet.com.cn (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Zhou, P.; Ang, B.W.; Wang, H. Energy and CO2 emission performance in electricity generation: A nonradial directional distance function approach. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 221, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.Q.; Cui, L.H.; Hong, P.H. The impact of carbon emissions trading on energy efficiency: Evidence from quasi-experiment in China’s carbon emissions trading pilot. Energy Econ. 2022, 110, 106025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government Website Performance Evaluation Report. Available online: https://www.wuchang.gov.cn/fzlm/wzpj/202101/P020210122415085714840.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Wen, H.W.; Liang, W.T.; Lee, C.-C. Urban broadband infrastructure and green total-factor energy efficiency in China. Util. Policy 2022, 79, 3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.Y.; Mbanyele, W.; Zhang, L.B.; Chen, X.-L.; Song, M.L. Nonnegligible transition risks towards net-zero economy: Lessons from green finance initiatives in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 375, 124132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angrist, J.D.; Pischke, J.-S. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Akerlof, G.A. The market for “Lemons”: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. Q. J. Econ. 1970, 84, 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. A transaction cost theory of politics. J. Polit. 1990, 2, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Li, Y.; Li, G. Boosting the green total factor energy efficiency in urban China: Does low-carbon city policy matter? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 56341–56356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkhangelsky, D.; Athey, S.; Hirshberg, D.A.; Imbens, G.W.; Wager, S. Synthetic Difference-in-Differences. Am. Econ. Rev. 2021, 111, 4088–4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, F.L.; Yan, L.; Wang, D. The complexity for the resource-based cities in China on creating sustainable development. Cities 2020, 97, 102571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Circular of the State Council on Printing and Issuing the National Plan for Sustainable Development of Resource-Based Cities (2013–2020). Available online: https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2013/content_2547140.htm (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Dong, S.H.; Wang, X.-C.; Dong, X.B.; Kong, F.J. Unsustainable imbalances in urbanization and ecological quality in the old industrial base province of China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Old Industrial Base Adjustment and Renovation Plan (2013–2022). Available online: https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2013/content_2441018.htm (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Wang, J.D.; Wang, B.; Dong, K.Y.; Dong, X.C. How does the digital economy improve high-quality energy development? The case of China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 184, 121960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.L.; Deng, Y.J. How does intellectual property protection contribute to the digital transformation of enterprises? Finance Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Market Index Database. Available online: https://cmi.ssap.com.cn (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Shen, G.B. Nominal level and actual strength of China′s intellectual property protection under TRIPS agreement. J. Chin. Econ. Foreign Trade Stud. 2010, 3, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.J.; Zhao, X.; Lv, K.J.; Rosak-Szyrocka, J.; Mentel, G.; Truskolaski, T. Internet development and carbon emission-reduction in the era of digitalization: Where will resource-based cities go? Resour. Policy 2023, 81, 103345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, F.; Tong, Q.M. A spatial difference-in-differences approach to evaluate the impact of light rail transit on property values. Econ. Model 2021, 99, 105496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, R.B.; Huang, H.Y.; Zhang, J.C.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, X. Green economic efficiency and productivity for sustainable development in China: A ray epsilon-based measure model analysis. Environ. Sci. Policy 2024, 160, 103860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batten, D.F.; Karlsson, C. Infrastructure and the Complexity of Economic Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Helsley, R. Economics of agglomeration: Cities, industrial location and regional growth. J. Econ. Geogr. 2004, 4, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Zarzoso, I.; Maruotti, A. The impact of urbanization on CO2 emissions: Evidence from developing countries. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1344–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.A.; Elliott, R.J.R. FDI and the capital intensity of dirty sectors: A missing piece of the pollution haven puzzle. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2005, 9, 530–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Types | Variables | Definitions | Mean | S.D. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | TFEE | Total factor energy efficiency measured by the SBM–Malmquist–Luenberger index method | 0.313 | 0.122 |

| Core independent variable | EPC | =1 if the prefecture-level city implemented the EPC policy, 0 otherwise | 0.120 | 0.119 |

| Control variables | GDP | Gross domestic product/Total population, logarithm | 10.452 | 0.723 |

| Fiscal | Budget revenues/Budget expenditures | 0.467 | 0.228 | |

| Openness | Total exports and imports of goods, logarithm | 13.985 | 2.134 | |

| Human capital | Number of university students enrolled per 10,000 persons | 0.054 | 0.014 | |

| Finance | Balance of loans from financial institutions, logarithm | 16.089 | 1.283 | |

| Industrialization | Number of industrial enterprises above designated size, logarithm | 6.554 | 1.118 | |

| Population density | Total population/Size of administrative area | 5.735 | 0.919 | |

| Mechanism variables | Structure | Value added of the tertiary sector/Value added of the primary and secondary sector | 0.723 | 0.391 |

| GTI | Green technology patents granted per 10,000 persons | 0.121 | 0.321 | |

| FDI | Total foreign direct investment | 0.506 | 1.063 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | TFEE | TFEE | TFEE | TFEE | TFEE |

| EPC | 0.026 *** | 0.029 *** | 0.027 *** | 0.026 *** | 0.026 *** |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |

| GDP | 0.030 *** | 0.032 *** | 0.047 *** | 0.047 *** | |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.012) | (0.012) | ||

| Fiscal | 0.023 | 0.022 | 0.029 * | 0.030 * | |

| (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.016) | ||

| Openness | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.005 | ||

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |||

| Human capital | 0.673 *** | 0.643 *** | 0.630 *** | ||

| (0.156) | (0.155) | (0.159) | |||

| Finance | −0.001 | −0.001 | |||

| (0.009) | (0.009) | ||||

| Industrialization | −0.025 *** | −0.026 *** | |||

| (0.006) | (0.006) | ||||

| Population density | 0.036 | ||||

| (0.049) | |||||

| City FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 0.309 *** | −0.015 | −0.118 | −0.117 | −0.315 |

| (0.001) | (0.083) | (0.096) | (0.153) | (0.293) | |

| R2 | 0.689 | 0.692 | 0.693 | 0.695 | 0.695 |

| N | 4230 | 4230 | 4230 | 4230 | 4230 |

| Line | Test Methods | Coefficients | Standard Error | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Controlling disturbing policies | ||||

| (1) | Energy Saving and Emission Reduction Fiscal Policy | 0.026 *** | 0.005 | 4230 |

| (2) | Air Pollutant Emission Standards Policy | 0.021 *** | 0.005 | 4230 |

| (3) | Low Carbon City Policy | 0.025 *** | 0.005 | 4230 |

| (4) | Carbon Emissions Trading Pilot Policy | 0.026 *** | 0.005 | 4230 |

| (5) | All policies | 0.021 *** | 0.005 | 4230 |

| Panel B: PSM-DID model | ||||

| (6) | Kernel matching | 0.036 *** | 0.007 | 2918 |

| (7) | Radius matching | 0.033 *** | 0.007 | 2897 |

| (8) | Nearest neighbor matching | 0.035 *** | 0.007 | 2913 |

| Panel C: Adjustment of sample range and core variables | ||||

| (9) | Adding province-year fixed effects | 0.031 *** | 0.006 | 4155 |

| (10) | Replacement core variables | −0.044 *** | 0.010 | 4230 |

| (11) | Adding predicate variables | 0.026 *** | 0.006 | 4230 |

| (12) | Excluding the municipality sample | 0.023 *** | 0.006 | 4170 |

| Panel D: Other tests | ||||

| (13) | Excluding samples in 2020 | 0.020 *** | 0.005 | 3948 |

| (14) | Considering lag effects | 0.015 *** | 0.005 | 3948 |

| (15) | Considering the expectation effect | −0.012 | 0.010 | 4230 |

| (16) | Considering two-way clustering (city, year) and a wild-cluster bootstrap check. | 0.026 *** | 0.012 | 4230 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Structure | GTI | FDI | L.Structure | L.GTI | L.FDI |

| EPC | 0.048 *** | 0.180 *** | 0.257 *** | 0.046 *** | 0.162 *** | 0.028 *** |

| (0.010) | (0.014) | (0.044) | (0.009) | (0.013) | (0.043) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R2 | 0.909 | 0.730 | 0.857 | 0.913 | 0.743 | 0.865 |

| N | 4230 | 4230 | 4230 | 3948 | 3948 | 3948 |

| Population Size | Resource-Based City | Old Industrial Bases | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small | Big | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Variables | TFEE | TFEE | TFEE | TFEE | TFEE | TFEE |

| EPC | −0.003 (0.009) | 0.041 *** (0.007) | 0.026 *** (0.007) | −0.004 (0.008) | 0.040 *** (0.007) | −0.017 ** (0.008) |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R2 | 0.685 | 0.724 | 0.688 | 0.692 | 0.663 | 0.776 |

| N | 2141 | 2086 | 2565 | 1665 | 2805 | 1425 |

| Marketization Level | IPP Level | Clan Culture | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Variables | TFEE | TFEE | TFEE | TFEE | TFEE | TFEE |

| EPC | 0.011 (0.007) | 0.047 *** (0.010) | −0.003 (0.010) | 0.041 *** (0.009) | 0.013 (0.009) | 0.036 *** (0.006) |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R2 | 0.714 | 0.714 | 0.760 | 0.732 | 0.698 | 0.700 |

| N | 2031 | 2157 | 2105 | 2109 | 2115 | 2115 |

| Infrastructure Investment | Digital Infrastructure | Internet Coverage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less | More | General | Good | General | Good | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Variables | TFEE | TFEE | TFEE | TFEE | TFEE | TFEE |

| EPC | −0.006 (0.010) | 0.038 *** (0.009) | −0.025 *** (0.007) | 0.039 *** (0.008) | −0.015 * (0.008) | 0.046 *** (0.010) |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R2 | 0.762 | 0.730 | 0.712 | 0.709 | 0.781 | 0.722 |

| N | 2109 | 2107 | 2101 | 2094 | 2104 | 2114 |

| Adjacency Matrix | Inverse Distance Matrix | Economic Matrix | Economic-Geographical Matrix | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Variables | TFEE | TFEE | TFEE | TFEE |

| EPC | 0.026 *** (0.005) | 0.024 *** (0.005) | 0.022 *** (0.005) | 0.020 *** (0.005) |

| W × EPC | −0.033 *** (0.010) | −0.180 * (0.093) | −0.031 ** (0.013) | −0.037 *** (0.012) |

| sigma2_e | 0.004 *** (0.000) | 0.004 *** (0.000) | 0.005 *** (0.000) | 0.004 *** (0.000) |

| Direct effect | 0.026 *** (0.005) | 0.024 *** (0.005) | 0.022 *** (0.005) | 0.020 *** (0.005) |

| Indirect effect | −0.032 *** (0.010) | −0.217 * (0.125) | −0.030 ** (0.013) | −0.037 *** (0.013) |

| R2 | 0.011 | 0.215 | 0.187 | 0.187 |

| N | 4230 | 4230 | 4230 | 4230 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Huang, W.; Liu, J. The Impact of Digital Governance on Energy Efficiency: Evidence from E-Government Pilot City in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10475. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310475

Li X, Huang W, Liu J. The Impact of Digital Governance on Energy Efficiency: Evidence from E-Government Pilot City in China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10475. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310475

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xiaoling, Weiting Huang, and Jilong Liu. 2025. "The Impact of Digital Governance on Energy Efficiency: Evidence from E-Government Pilot City in China" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10475. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310475

APA StyleLi, X., Huang, W., & Liu, J. (2025). The Impact of Digital Governance on Energy Efficiency: Evidence from E-Government Pilot City in China. Sustainability, 17(23), 10475. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310475