Abstract

This study investigates how corporate governance and changes in governance rankings influence firms’ cost of capital. Using data from 1723 Taiwanese listed firms, comprising 11,940 firm-year observations between 2017 and 2024, the analysis applies Taiwan’s corporate governance evaluation system, published by government-affiliated institutions. The results reveal a significant negative relationship between corporate governance and firms’ cost of capital, indicating that higher governance rankings are associated with lower financing costs. Moreover, when firms’ governance rankings improve, their cost of capital decreases, whereas downgrades lead to increases. These findings suggest that capital markets adjust firms’ cost of capital inversely in response to changes in governance rankings. The study further shows that the ability to reduce capital costs depends on firms’ governance levels; a downgrade results in a more pronounced cost increase for well-governed firms. Overall, this research provides empirical evidence from an emerging market and offers practical implications for firms, creditors, investors, and regulators aiming to enhance sustainable development, strengthen risk management, optimize investment selection, and improve corporate governance practices.

1. Introduction

From a theoretical perspective, a firm requires a reliable source of funding to maintain operational activities and achieve its basic goal of making a profit. According to pecking order theory [1], firms primarily obtain external financing from two sources: debt and equity. The cost of this financing influences firms’ investment decisions, thereby affecting the success or failure of their operations [2]. Consequently, the cost of capital is a pivotal factor in a firm’s operational performance and future development. However, it is important to consider which standards of corporate governance (CG) a firm must achieve to convince creditors and investors to entrust their funds with the firm at a lower cost of capital.

A considerable number of empirical studies have recently utilized various proxies for corporate governance, including the governance index [3,4,5], governance score [6], governance ratings [7,8], and a set of governance components [9,10], to examine the impact of corporate governance on a firm’s cost of capital. For instance, existing literature predominantly reports a negative and significant relationship between the CG index and firms’ cost of capital [3,4], and a decrease in bond spreads following an improvement in the overall quality of the CG index [5]. The current body of research indicates that good corporate governance is consistently associated with lower costs of equity and debt [6]. Additionally, firms with better CG ratings have more accessible financing and better performance [7,8]. Furthermore, a significant negative correlation has been found between CG mechanisms and the cost of equity [9,10]. However, directly comparing the results of these studies is not straightforward, partly because disparate corporate governance indices or ratings were used as proxies to assess compliance and disclosure. The most significant difference between this study and previous similar studies [3,4,5] is the use of corporate governance evaluation rankings published by Taiwan’s government-affiliated institutions as a proxy variable. This allows us to examine the impact of corporate governance on a firm’s cost of capital more directly and precisely using publicly available information.

The analysis is based on a sample of 1723 Taiwanese listed firms from 2017 to 2024, comprising 11,940 firm-year observations. This study contributes to the existing literature in several ways. Firstly, it employs an innovative and unique dataset of corporate governance rankings, released by government-affiliated institutions, to examine the impact of corporate governance on firms’ cost of capital, yielding results that are comparable across various governance proxies. Secondly, although prior empirical studies have documented the effect of corporate governance on firms’ cost of capital [3,4,6,9], limited evidence addresses how changes in governance rankings influence financing costs. This study fills that gap by analyzing the effects of changes in governance rankings on firms’ cost of capital. Thirdly, while previous research has focused on the disclosure of Taiwan’s governance rankings and its role in reducing information asymmetry among investors [11,12,13], this study extends that line of inquiry by providing empirical evidence of a negative relationship between governance rankings and firms’ cost of capital. Finally, the findings highlight that economies such as Taiwan, an emerging market actively implementing governance reforms where firms rely heavily on bank financing, establish and enforce corporate governance practices to protect market participants and address governance challenges.

The empirical findings can be summarized as follows. Firstly, governance quality is significantly and negatively associated with financing costs, suggesting that stronger governance reduces firms’ cost of capital. In addition, improvements in governance rankings further decrease capital costs, while downgrades have the opposite effect, suggesting that markets adjust financing costs inversely to governance changes. Moreover, the results show that the magnitude of these effects depends on firms’ governance levels, as those with stronger governance experience larger cost increases when downgraded. Furthermore, firms with stronger governance exhibit greater sensitivity in their cost of capital to changes in governance rankings. Overall, these findings highlight how governance quality influences financing efficiency.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 relates to the corporate governance evaluation system in Taiwan. Section 3 presents the hypothesis development. Section 4 explains the sample selection and empirical estimation. Section 5 reports the empirical findings. Section 6 discusses the managerial and policy implications, as well as the limitations and future research. Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. A Review of the Corporate Governance System in Taiwan

The extant literature indicates that CG is a crucial element for developing financial markets and protecting market participants [3,14]. Many studies have noted that ill-designed and ineffectively implemented CG practices could have caused the 1997 Asian and 2008 global financial crises [11,15,16]. As a part of the Asia–Pacific region, Taiwan therefore suffered greatly from both economic events. To avoid similar incidents from occurring and in response to rapid developments in corporate governance reforms in neighboring countries, Taiwanese regulators have put forth concerted efforts to improve CG practices. As part of this, the Financial Supervisory Commission (FSC) in Taiwan issued a 5-year “Corporate Governance Roadmap” in December 2013, which is regarded as an essential development for corporate governance reforms, aiming to accelerate the implementation of corporate governance among Taiwanese listed firms, assist firms with sound development and increase market confidence.

According to the Roadmap, the implementation of corporate governance evaluation was one of the major projects of 2014, with the goal of helping investors and firms better understand the performance of corporate governance by comparing the evaluation results among firms. To accelerate the implementation of corporate governance by TWSE/TPEx listed firms, the TWSE and TPEx have teamed up to establish and promote the corporate governance evaluation system. The Corporate Governance Center (the “Center”) works under instruction from the FSC and designs the evaluation indicators. Experts are engaged in joining the Corporate Governance Evaluation Committee to review the indicators. Notably, the content and results of the corporate governance evaluation have been published for a period of ten consecutive years (from 2015 to 2024), and it will be continuously executed. Therefore, further research is needed to determine whether the publication of corporate governance rankings has facilitated investor comprehension of corporate governance performance and whether firms with superior corporate governance rankings have enabled access to cost-effective external financing.

Some studies in the existing literature compile a set of independent variables to proxy corporate governance, while others employ one or two variables to analyze its effect on dependent variables. For example, scholars have employed 24 provisions to develop a corporate governance index (the G-index) [17]; considered corporate governance attributes from Institutional Shareholders Services (ISS) [6,18]; and adopted survey-based corporate governance scores provided by the Credit Lyonnais Securities Asia (CLSA) [19]. These studies exemplify the difficulties encountered by researchers in measuring corporate governance [11]. However, in contrast to existing indices, there are several reasons to illustrate how this CG evaluation system in Taiwan is different from existing indices and explain why releasing the CG evaluation rankings in Taiwan is worth exploring. First, following a series of public hearings in which comments and suggestions were invited, multiple dimensions were identified and incorporated into Taiwan’s CG evaluation system. The dimensions in question were derived in accordance with both domestic and foreign corporate governance regulations and practices. Each dimension comprises multiple indicators, with their weight. (See Table A1 in Appendix A for details of the composition of indicators in the five CG dimensions from 2014 to 2023.) Particularly, over the past decade, evaluation indicators have continuously evolved, promising the delivery of more effective information to the public and representing the growing importance of the system.

Second, the ten rounds of CG evaluation exercises conducted in Taiwan from 2014 used indicators from several corporate governance dimensions, providing a comprehensive dataset for the thorough investigation of the published effects of CG evaluation rankings on the agency problem and information asymmetry. Third, the governance structure and system may depend on macroeconomic factors. These factors could depend on the business environment, firm characteristics, and the nature of the capital market [20]. These are the advantages of the Taiwan CG evaluation system, which makes it more suitable for exploratory analysis in this study. Fourth, the present study is closely related to the previous works [3,6], yet it provides a complementary perspective by incorporating the concept of corporate governance reform and firms’ costs of external financing. Fifth, in contrast to the preceding studies, Taiwan’s FSC has mandated that all Taiwanese firms listed on the TWSE/TPEx must engage in these corporate governance assessment exercises. These exercises, which are all inclusive in nature, mitigate the potential selection or judgmental biases that have been identified in previous studies [11,12,13].

3. Hypothesis Development

The literature shows that CG can reduce agency problems and protect minority shareholders against expropriation by managers and controlling shareholders [3,6]. In addition, the literature reports that good corporate governance practices are mainly related to minimizing corporate failure and helping firms attract capital at a lower cost in emerging markets [3]. Thus, firms with better CG are widely recognized to be associated with higher firm value and accounting profitability [7,17,21], which reflects firms’ lower cost of capital [3].

Additionally, prior studies suggest that firms with better governance are associated with lower costs of equity and debt capital [6]. This is consistent with the argument that good corporate governance reduces the risks faced by shareholders and creditors, thereby lowering the cost at which they are willing to provide capital [19,22,23,24]. Earlier studies have adopted corporate governance ratings to measure the level of corporate governance of a firm [6,21], showing that firms with good corporate governance are consistently associated with lower costs of equity and debt capital in different international settings with regard to legal systems, information disclosure and government quality. The above discussions suggest that the relationship between corporate governance and the cost of capital depends on the level of a country’s governance standards. Thus, much can be learned from corporate governance research, particularly from emerging markets, about how to improve corporate governance quality under corporate governance reform. Specifically, it raises the critical question of whether firms in emerging markets can effectively increase their firm value by reducing their cost of capital through the adoption of CG evaluation rankings published by government-affiliated institutions (e.g., Taiwan). While this is not a new research topic, the results of the study may provide necessary policy implications for other emerging economies, such as Taiwan, where empirical findings are rare and vital for providing a broader picture of corporate governance compliance and disclosure behavior. We therefore propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

There is a significantly negative relationship between corporate governance and firms’ cost of capital.

Taiwan’s CG evaluation system has been developed to enable firms to conduct self-assessments and proactively implement governance measures to enhance their corporate governance practices [12]. Research has shown that when a firm’s corporate governance evaluation results for the current year exceed those of the previous year, investors positively react to the firm’s stock price [11]. This suggests that investors may respond positively to firms with strong governance through investment [13], so publishing evaluation results provides investors with valuable reference information. Consequently, CG evaluation rankings disclose governance information, strengthening governance mechanisms, mitigating agency problems, and incentivizing firms to improve their corporate governance practices [11,13]. However, no analysis has examined how changes in corporate governance rankings affect firms’ cost of capital, except for the estimations of the effect of an improvement in corporate governance on firms’ credit ratings [25], and the effects of changes in corporate governance characteristics on firms’ intellectual capital [26]. This study attempts to address this gap by investigating whether changes in corporate governance rankings impact firms’ cost of capital differently. We propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

An upgrade in corporate governance rankings will reduce a firm’s cost of capital. Conversely, a downgrade in corporate governance rankings increases the cost of capital.

The relationship between corporate governance and the cost of capital for firms has been extensively studied in both developed and developing countries [3,4,6,27]. The existing literature indicates that firms with stronger corporate governance have significantly higher credit ratings, which emphasizes the importance of corporate governance in the rating process [25]. Previous studies have also shown that higher levels of corporate governance limit managers’ ability to act in their own self-interest, resulting in more effective decision-making and improved firm performance [24,28]. While there is empirical evidence on the effect of corporate governance on firms’ cost of capital, prior research has not examined whether different levels of corporate governance impact firms’ cost of capital differently. Specifically, the unambiguous quantitative effects of high, medium, and low levels of corporate governance on firms’ cost of capital should be investigated [28]. We therefore propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

Firms with higher levels of corporate governance experience a greater reduction in their cost of capital than firms with lower levels.

4. Data and Methodology

4.1. Data and Sample Selection

The sample used to analyze the effect of corporate governance on firms’ cost of capital consisted of evaluation results from the CG evaluation system published by Taiwan’s Corporate Governance Center (the Center). There were ten rounds of corporate governance evaluations from 2015 to 2024. In the first and second rounds, the publication revealed the top 20% and 50%, respectively, of all participating firms based on calculated CG scores. Starting with the evaluation on 14 April 2017, the Center published the rankings of all the evaluated firms. Since CG evaluation is an ongoing exercise, the evaluation indicators and calculation methods are modified significantly every two years. Therefore, we selected the CG evaluation rankings of firms from 2017 to 2024 as the focus of our research to ensure a consistent annual evaluation interval for the sample.

There were three criteria for selecting the sample. First, we manually collected yearly samples of firms from the CG evaluation system reports published by the Center from 2017 to 2024. These are Taiwanese publicly listed firms in the TWSE/TPEx. Thus, the CG evaluation rankings of the firms in the sample were employed as a proxy for the corporate governance variable. Second, we excluded financial institutions (i.e., firms in the banking, insurance, and securities industries) because their industry characteristics and capital structures differ from those of other industries. Third, firms that experienced financial distress or were delisted are excluded from the sample at the beginning of their financial or delisted year. Fourth, we collected financial and stock market variables from the Taiwan Economic Journal (TEJ). However, if a firm’s financial or stock market variables are missing, the firm is excluded from the sample. Given these inclusion and exclusion criteria, the final sample consists of a cross-section of 1723 Taiwanese firms listed on the TWSE/TPEx. This yields 11,940 firm-year observations for examining the impact of corporate governance on firms’ cost of capital. Furthermore, all the continuous variables are Winsorized at the 1% and 99% levels.

4.2. Methodology and Variables

This study uses an unbalanced panel data analysis due to the combination of a large number of cross-sectional observations, not all of which are time series. Following previous empirical studies [3,4,6], we used the ordinary least squares (OLS) model to estimate the effect of corporate governance evaluation rankings (CGER) on the cost of capital (COC) for Taiwanese listed firms. The empirical model is presented below.

where i and t represent the firm and time, respectively. This study developed the COC variable (the dependent variable) by calculating the weighted average of the cost of capital (WACC), which incorporates the cost of debt and the cost of equity components [3,6]. The cost of debt (COD) = [(interest expense + capitalized interest expense)/average of short-term and long-term debt]—TAIBOR (Taipei Interbank Offered Rate). The cost of equity capital (COE) is calculated using the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). According to the CAPM, a firm’s cost of equity capital is equal to the risk-free rate (Rf) plus the market risk premium multiplied by βi. The COC variable leads one period ahead (t + 1) of all independent variables, including CGER [6], which are announced by the Center and proxied as the quality of a firm’s CG. The CGER variable has multiple values ranging from 1 to 7. These values correspond to ranking categories from 1 to 7, indicating the ordered quality of corporate governance from low to high. Furthermore, to measure the impact of changes in CG evaluation rankings on firms’ costs of capital, we created two dummy variables. The first is CGER_UP (CGER upgrade), which represents an improvement in a firm’s CG evaluation ranking in subsequent years compared with the previous year. The second is CGER_DOWN (CGER downgrade), which represents a worsening of a firm’s CG evaluation ranking in subsequent years compared with the previous year.

COCi,t+1 = β0 + β1CGERi,t + β2CGER_UPi,t + β3CGER_DOWNi,t + Σβj(Firm Characteristics)j,t + Σβk(Control Variables)k,t + εi,t

In line with the literature, firm characteristic variables that have been shown to explain the cost of capital are defined and controlled for in this study. These are as follows: firm leverage (LEVG) proxies for default [25]; the book-to-market ratio (B/M) measures firm value [6]; beta (BETA) captures systematic risk, which is measured using a regression of stock returns against market returns [6]; firm performance is measured using return on equity (ROE) [9]; the dividend payout ratio (DIVD), which makes minority rights shareholders willing to provide external financing [7]; the interest coverage ratio (ICR), which indicates a firm’s ability to pay off interest due on its debt [25]; the sales growth ratio (SALESG), which captures a firm’s operational performance [3]; and Tobin’s Q (TBSQ), which measures a firm’s growth potential [7].

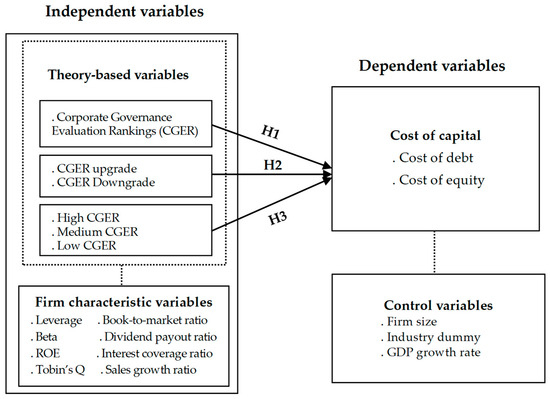

We also used firm size (SIZE), an industry dummy (IND), and the GDP growth rate (GDPG) [4] to control for the different firms, industries, and macroeconomic conditions prevailing at the time of the CGER announcement. ε is the error term. Table A2 in Appendix A lists the definitions of the theory-based, firm characteristics, and control variables. Figure 1 presents the research framework and hypotheses, which are based on hypotheses development and methodology description.

Figure 1.

Research framework and hypotheses.

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Distribution, Descriptive Statistics, and Correlation Analysis

Table 1 shows the distribution of the sample by industry and CG evaluation ranking. The CG evaluation firms are categorized into 26 industries based on the security code of the Taiwan Security Exchange Council (TSEC), as shown in Panel A. Of the 11,940 observations, more than one-third are concentrated in the electronics industry (23.62% in “Electronics” (code 23) and 11.64% in “Other Electronics” (code 24), for a total of 35.26%). This phenomenon can be attributed to efforts by Taiwan’s authorities to foster growth in the high-tech industry, a sector requiring substantial investment, including semiconductor, computer and peripheral equipment, and electronic parts/components. In recent years, Taiwan has played a crucial role in the global IT manufacturing system with government support. Notably, Taiwan has emerged as the third-largest IC and PC manufacturing hub, behind only the United States and Japan. This has earned Taiwan the reputation of being the “chip kingdom” [29]. Therefore, it is imperative to ascertain whether firms in high-tech industries have improved corporate governance and reduced capital costs to promote growth.

Table 1.

Distribution of the sample by industry and CG evaluation rankings (Obs. = 11,940).

Panel B shows how the sample was distributed based on firms’ CG evaluation rankings from 2017 to 2024. The sample size increased yearly, growing from 1380 observations in 2017 to 1595 observations in 2024. Additionally, 35.92% of the observations (i.e., 15.36% ranked 2nd and 20.56% ranked 1st) were distributed across the two lowest ranks of the CG ranking scale, which ranges from 7th to 1st.

Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations of the variables for the full dataset utilized in the present analysis. As illustrated in the accompanying table, the findings indicate that six variables, namely, the cost of capital (COC), the CGER upgrade (CGER_UP), the CGER downgrade (CGR_DOWN), the dividend payout ratio (DIVD), the industry category (IND), and the GDP growth rate (GDPG), exhibited substantial heterogeneity, with their standard deviations exceeding their means. The remaining variables exhibited minimal heterogeneity. The correlations of all the variables are also displayed in Table 2. All the variables exhibited moderate Pearson correlations, ranging from −0.352 to 0.389.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlations.

5.2. Univariate Analysis

Table 3 presents the results of both the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the differential analysis of the samples. The results of the one-way ANOVA of the CGER in year t − 1 on the cost of capital in year t are displayed in Panel A. Specifically, in 2016, firms that ranked 7th, 6th, 5th, 4th, 3rd, 2nd, and 1st in corporate governance evaluations had average capital costs in 2017 of 0.003, 0.071, 0.075, 0.076, 0.078, 0.079, and 0.086, respectively. (Indeed, the firm underwent an evaluation in 2016, with the results being announced in 2017. Therefore, the 2016 CGER is being compared to the 2017 COC.) The findings indicate a negative relationship between the CGER in 2016 and the cost of capital in 2017, with a significant difference in the cost of capital at the 1% level (F-statistic = 33.13, p-value < 0.000). The results of the analysis of variance (ANOVA) demonstrate consistency across all years (from 2017 to 2024), thus aligning with the hypothesis that firms with higher corporate governance consistently exhibit a lower cost of capital.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis by CG evaluation rankings to COC.

As illustrated in Panel B of Table 3, a comprehensive analysis of the cost of capital is available. The sample was divided into three groups, namely, high CGER (ranking 6th to 7th), medium CGER (ranking 3rd to 5th), and low CGER (ranking 1st to 2nd). The respective numbers of observations for each group were 2237, 5415, and 4288. A two-sample mean comparison test was subsequently implemented for the three groups of samples. The results imply that the cost of capital differed significantly between each pair of groups at the 1% level. For example, these findings indicate that the average cost of capital in high CGER firms was found to be lower than that in medium CGER and low CGER firms (i.e., the mean values are 0.021, 0.088, and 0.099, respectively). Additionally, the average cost of capital for medium CGER firms was lower than that of low CGER firms. Thus, this result suggests that different levels of CG may result in varying effectiveness in reducing the cost of capital, offering further insight into the relationship between CG and firms’ cost of capital. Accordingly, a nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test yielded similar results.

5.3. Multiple Regression Results

5.3.1. Corporate Governance and the Cost of Capital

This section explores the relationship between corporate governance and the cost of capital of firms. As illustrated in Table 4, there is a negative association between corporate governance and firms’ cost of capital, taking into account firm characteristics and control variables. For instance, the coefficients of CGER are −0.0054 in regression (1) and −0.0044 in regression (3), both of which are statistically significant at the 1% level, implying that firms with effective corporate governance exhibit a reduced cost of capital. The findings demonstrate a significantly negative relationship between corporate governance and firms’ cost of capital because firms with higher CGER have a lower cost of capital. The result is consistent with the findings of previous studies [3,6] and supports H1. Consequently, this result suggests that firms’ efforts to enhance their governance may lead to a reduction in their cost of capital.

Table 4.

Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression results.

In addition, to measure the impact of changes in corporate governance evaluation rankings on firms’ costs of capital, regressions (2) and (3) were incorporated with variables representing upgrade (CGER_UP) and downgrade (CGER_DOWN) shifts in corporate governance evaluation rankings. As presented in Table 4, the coefficients for regressions (2) and (3) demonstrate that the coefficients for the upgrade change in corporate governance evaluation ranking (CGER_UP) are −0.0074 and −0.0043, respectively. The statistical significance of these coefficients is supported by a level of at least 5%. In contrast, the coefficients for the downgrade change in corporate governance evaluation ranking (CGER_DOWN) are 0.0223 and 0.0203, respectively, both of which attain statistical significance at the 1% level. The finding is in line with H2 and indicates that a firm’s corporate governance evaluation ranking improves (i.e., it upgrades its governance ranking) in subsequent years compared with the previous year, resulting in a decrease in its cost of capital. Conversely, if the ranking worsens (i.e., if there is a downgrade in governance rankings) in the subsequent year, the cost of capital increases. These results provide evidence that the capital market adjusts the cost of capital for firms when their corporate governance evaluation rankings change. Consequently, the results imply that changes in corporate governance evaluation rankings have incremental information effects, helping creditors and investors assess a firm’s value and operating performance.

In examining the firm characteristics, it is evident that the coefficients on firm leverage (LEVG), book value of equity to market value (B/M), and equity Beta (BETA) are positive and statistically significant at the 1% level in regressions (1)–(3). This finding suggests that firms with lower leverage, book-to-market ratio, and Beta values are associated with a lower cost of capital. With the exception of the coefficient of the interest coverage ratio (ICR), which is negative and insignificant, the coefficients of return on equity (ROE), dividend payout (DIVD), sales growth (SALSG), and Tobin’s Q (TBSQ) are significantly negative at least at the 5% level in regressions (1)–(3). This suggests that firms with higher performance, dividend payments, sales growth, and Tobin’s Q have a lower cost of capital. However, these findings are consistent with predictions in the extant literature [3,25].

Turning to the control variables proxying by firm size, the industry dummy, and the GDP growth rate (SIZE, IND, and GDPG), regressions (1)–(3) show that the coefficients of firm size and the industry dummy are positively associated with firms’ cost of capital at least at the 5% level. This result may be attributed to the structure of the Taiwanese industry, in which a significant proportion of CGER firms are classified as “new economy” (as previously reported in Panel A of Table 1). However, it is not necessarily the case that larger firms have higher capital costs. (This may stem from Taiwan’s bank-based financial system, in which firms depend heavily on bank financing, resulting in substantial funding scales. Other factors include the growth stage of firms in emerging markets, industry characteristics (e.g., the electronics and information technology sectors), and factors unrelated to scale.) In accordance with the extant literature, regressions (1) to (3) show a statistically significant negative correlation between the GDP growth rate and the firm’s cost of capital. This implies that when the GDP growth rate is high, firms may experience lower external financing costs due to abundant external funding.

In summary, our results suggest that firms with good corporate governance have a lower cost of capital. This finding indicates that better corporate governance leads to a lower cost of capital through greater access to external financing. We also found that when corporate governance improves, as indicated by an upgrade in the firm’s corporate governance evaluation ranking, its cost of capital tends to decline. Conversely, when corporate governance deteriorates, as indicated by a downgrade in the firm’s corporate governance evaluation ranking, its cost of capital tends to increase. This provides evidence that the capital market adjusts the cost of capital adversely for firms when their corporate governance evaluation rankings change.

5.3.2. The Impact of Different Levels of CG on the Cost of Capital

In this section, we conduct further analysis to examine how different levels of corporate governance explain a firm’s cost of capital. We split our sample into three CG levels and defined three dummy variables: HCGER (high CG level, rankings 6th–7th); MCGER (medium CG level, rankings 3rd–5th); and LCGER (low CG level, rankings 1st–2nd). These interval rankings are designed to unambiguously capture the high, medium and low levels of the CG factor. Using this partitioning scheme, we estimate the following ordinary least squares (OLS) model.

where HCGER, MCGER and LCGER represent the three levels of corporate governance previously defined, and all other variables (i.e., firm characteristics and control variables) are defined as in Equation (1). As specified, the above models enable us to estimate the incremental effect of the level of corporate governance (CG) on firms’ cost of capital. In addition, to measure the interaction between CG levels and changes in CGER (i.e., upgrades and downgrades) to firms’ cost of capital, the above three models incorporate six interaction variables: HCGER*CGER_UP, MCGER*CGER_UP, LCGER*CGER_UP, HCGER*CGER_DOWN, MCGER*CGER_DOWN, and LCGER*CGER_DOWN.

COCi,t+1 = β0 + β1HCGERi,t + β2MCGERi,t + Σβj(Firm Characteristics)j,t + Σβk(Control Variables)k,t + εi,t

COCi,t+1 = β0 + β1HCGERi,t + β2LCGERi,t + Σβj(Firm Characteristics)j,t + Σβk(Control Variables)k,t + εi,t

COCi,t+1 = β0 + β1MCGERi,t + β2LCGERi,t + Σβj(Firm Characteristics)j,t + Σβk(Control Variables)k,t + εi,t

Table 5 presents the results of the regression analysis for partitioned corporate governance. In regression (1), the coefficients for HCGER and MCGER are −0.0313 and −0.0036, respectively, and both are statistically significant at the 1% level. However, note that the HCGER coefficient is considerably more negative in magnitude than the MCGER coefficient is (i.e., −0.0313 vs. −0.0036). When regressions (3) and (5) are run separately using two of the three levels of corporate governance proxy variables, the results are similar, but the coefficient of LCGER is positive (0.0025) and statistically insignificant in regression (5). The results indicate that firms with a high level of corporate governance (i.e., firms are reported at a high CGER, as well as in the 6th and 7th rankings) are more likely to receive a lower cost of capital than those with a low level of corporate governance (i.e., firms are reported at a low CGER, as well as in the 1st and 2nd rankings). These results support H3. Thus, if a firm is evaluated within the two lowest rankings of the corporate governance evaluation system for a given year, the system generates a ‘warning’ for the firm’s stakeholders. Creditors and investors are unlikely to reduce the firm’s external financing costs at this time. These findings offer additional insights into the relationship between corporate governance and firms’ cost of capital, a concept not previously documented in the extant literature.

Table 5.

OLS results of different levels of CGER on firms’ cost of capital.

We also examine whether the interaction between firms’ different levels of CG and their CGER changes has a differential effect on their cost of capital. The findings from regressions (2), (4), and (6) suggest that when the CGER of firms are upgraded, firms with strong corporate governance tend to be more influenced by the cross-interaction between the different levels of CG and their CGER changes on the cost of capital. For example, the coefficient of HCGER*CGER_UP is considerably more negative in magnitude than that of MCGER*CGER_UP (i.e., −0.0165 vs. −0.0053) in regression (2). When regressions (4) and (6) are executed separately, utilizing two of the interaction variables, the results are similar. However, the coefficient of LCGER*CGER_UP becomes statistically insignificant in regressions (4) and (6). Consequently, firms with strong corporate governance (i.e., firms are reported at high CGER) are more likely to receive a lower cost of capital when the CGER of firms is changed to upgrade, whereas those with weak governance (i.e., firms are reported at low CGER) may not.

To assess the impact of a downgrade shift in firms’ CGER on the cost of capital across varying levels of firm CG, we have separately measured the three interaction variables. The findings of this analysis are subsequently reported in regressions (2), (4), and (6). The positive and statistically significant coefficients for all levels of CG are evident when there is a downgrade change in the firms’ CGER. Therefore, firms with strong CG (i.e., firms are reported at high CGER) demonstrate a more pronounced increase in the magnitude of their cost of capital than those with weaker CG (i.e., firms are reported at low CGER). For instance, the coefficient of HCGER*CGER_DOWN (0.0725) is considerably more positive in magnitude than MCGER*CGER_DOWN (0.0152) in regression (2). Moreover, the findings from regressions (2), (4), and (6) are consistent with one another.

In summary, corporate governance levels are associated with the capacity of firms to reduce their capital costs. Specifically, firms with higher levels of corporate governance have a greater reduction in their cost of capital than firms with lower levels of corporate governance. Additionally, when a firm is evaluated within the two lowest rankings of the corporate governance evaluation system for a given year, the system generates a ‘warning’ for the firm’s stakeholders. Creditors and investors are unlikely to reduce the firm’s external financing costs at this time.

5.3.3. Robustness Check

To further evaluate the reliability of the results, we conducted two additional robustness tests. First, we further replace the COC measures with two alternative variables, namely, the cost of debt (COD) and the cost of equity (COE). These variables have been commonly employed in many prior studies [3,6]. In the robustness test conducted using the OLS model in Equation (1), the dependent variables were altered to the COD and the COE.

The estimated results are presented in Table 6. As expected, the estimated coefficients of CGER remain statistically significant and negative in regressions (1) and (3), as shown in Panel A. In regressions (2) and (3), the coefficients representing the upgraded (CGER_UP) and downgraded (CGER_DOWN) changes in firms’ CG rankings are statistically significant for negative and positive values, respectively. The findings relating to the use of the COE as the dependent variable are consistent with the earlier results, as shown in Panel B. Additionally, Panels A and B show that the firm characteristics and control variables have the expected signs and significance, which is consistent with the earlier findings. Consequently, the robustness test results confirm our earlier findings, as reported in Table 4.

Table 6.

Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression results for firms’ COD and COE.

The CGER variable takes on values ranging from 1 to 7, corresponding to ranking categories from 1 to 7, which indicate the quality of corporate governance, ordered from low to high. Following previous studies [24,25], the ordered logit model is the recommended technique when the dependent variable has multiple ordered values. Thus, we used the ordered logit model to assess the robustness of our estimation results by switching the roles of the independent and dependent variables (i.e., CGER and cost of capital, respectively). In addition, we define an ordered dependent variable, which takes on values ranging from 1 to 3. These values correspond to low, medium, and high CG evaluation rankings, indicating quality, which is ordered from low to high. Thus, we also examine the effect of different levels of corporate governance on firms’ cost of capital using an ordered logit model to test robustness.

Table 7 shows the results of the ordered logit regressions for the relationship between corporate governance and the cost of capital for firms. As shown in regression (1), the coefficient of the cost of capital (COC) is negative (−2.0010) and significant at the 1% level when the dependent variable is the CGER variable. This indicates a negative relationship between corporate governance and firms’ cost of capital. Furthermore, when the dependent variable is replaced by low, medium and high CG rankings in regression (2), the estimated COC coefficient remains negative (−1.9538) and significant at the 1% level. This implies that firms with higher CG rankings have a greater capacity to reduce the cost of capital than those with lower rankings do. Additionally, all the coefficients of the firm-specific control variables have the expected signs and significance in regressions (1) and (2). These estimations suggest that firms with lower leverage, smaller book-to-market ratios, higher performance, greater value and larger size are associated with higher CG rankings (i.e., higher quality CG).

Table 7.

The ordered logit regression results for CGER and different levels of CGER.

Overall, the results of the robustness test support our earlier findings that corporate governance significantly affects a firm’s cost of capital, even when the cost of capital is proxied by either the cost of debt or the cost of equity. Additionally, the negative effect of corporate governance on firms’ cost of capital remains robust when the roles of the independent and dependent variables are switched (i.e., CGER and cost of capital, respectively).

In order to address the potential endogeneity issue in the relationship between governance and the cost of capital, we further employed the lagged OLS, instrumental variables (IV), and generalized method of moments (GMM) estimations to investigate the extent to which the main findings were affected by this problem, following the approach of prior studies [3,30]. This study reproduces the primary regression model with one-year lagged values for all explanatory variables and utilizes dynamic panel data to run the GMM estimator, which mitigates the detrimental consequences of endogeneity [30]. The econometric model incorporates the lagged value of the dependent variable, lagged COC, as an explanatory variable to investigate the dynamic effects. The results of the study are presented in Table 8. A comparison of the findings from the lagged OLS, IV, and GMM regressions with the results of the un-lagged OLS reveals a high degree of similarity. The two analyses predict coefficients with similar signs and magnitudes of the coefficient with the level of significance. Overall, it is found that endogeneity may not be a serious concern for this study.

Table 8.

Robust results based on lagged OLS, IV, and GMM.

6. Discussion

6.1. Managerial Implications

The empirical results of this study lend support to the effectiveness of Taiwan’s corporate governance evaluation system, suggesting that firms with higher corporate governance evaluation results have a lower cost of capital. This system provides practical information for firms and their stakeholders, thereby effectively mitigating principal–agent conflicts and information asymmetry issues within the Taiwanese market. Accordingly, the findings yield several managerial implications that can serve as a reference for firms, creditors, investors, and regulators.

Firstly, implementing corporate governance evaluations has been shown to reduce firms’ cost of capital. This finding suggests that firms can enhance operational efficiency, performance, and investor confidence. Consequently, it has prompted firms to cultivate a stronger corporate governance culture and pursue sustainable development. Furthermore, the evaluation indicators incorporate environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) factors, encouraging firms to consider sustainability in their business strategies.

Secondly, empirical evidence indicates that firms with higher corporate governance rankings have lower capital costs, demonstrating that governance evaluations offer creditors valuable information. This facilitates the mitigation of credit risk for creditors, thereby enabling more effective risk management and lending decisions.

Thirdly, as a firm’s corporate governance ranking improves, its corporate value also increases significantly, leading investors to place greater emphasis on the firm. Consequently, these rankings assist investors in making more informed investment decisions, thereby enabling them to manage portfolio risks more effectively and select suitable investment targets.

Fourthly, the Taiwan corporate governance evaluation system provides an evolving set of evaluation indicators. The evaluation results offer regulators clear insights into the state of corporate governance within firms, enabling them to promote regulatory revisions, formulate policies, and enhance market mechanisms. As a result, Taiwan’s securities market continues to secure a prominent position in the Asian region.

6.2. Policy Implications

As of 2024, Taiwan’s corporate governance evaluation system has been in operation for a decade. Over this period, the evaluation indicators have continuously evolved, enhancing the delivery of effective information to the public and reflecting the growing importance of the system. The findings of this study yield several policy implications. First, quantitative evaluation indicators provide clear guidance for firms seeking to improve shareholder rights, board governance, information transparency, and sustainable development. This process fosters a more proactive corporate governance culture. Second, the publication of evaluation results enables stakeholders, such as investors and the media, to more effectively assess the quality of corporate governance, thereby encouraging firms to place greater emphasis on it. Third, incorporating information transparency as an evaluation criterion motivates firms to disclose more information, thereby reducing information asymmetry and improving market efficiency. Fourth, the results of corporate governance evaluations are critical for investors when assessing firms. Favorable outcomes not only enhance a firm’s reputation but also help attract greater investment.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

The limitations of this study include the inability to observe firms that participated in the evaluation but were not ranked, as well as the focus on the primary dependent variable of the governance ranking. In light of these limitations, our findings call for further research to determine the additional explanatory power of corporate governance in explaining firms’ cost of capital when unranked firms and broader governance variables (e.g., equity structure and board composition) are incorporated. Additionally, although our empirical results fully support the hypotheses proposed in this study, they apply primarily to an emerging market such as Taiwan, where firms heavily rely on bank financing [31]. In particular, the study lacks a stronger comparative perspective with findings from other emerging Asian economies to enhance its international relevance. Consequently, the generalizability of these findings to other countries remains limited. Further regional research is therefore necessary to examine the relationship between corporate governance and firms’ cost of capital, especially through a comparative analysis of emerging markets in different geographic regions.

7. Conclusions

Effective corporate governance can enhance a firm’s expected value by lowering external financing costs, thereby reducing its cost of capital. This study examines the impact of corporate governance and changes in governance rankings on firms’ cost of capital using Taiwan’s corporate governance evaluation system, which is administered by government-affiliated institutions. The analysis is based on 1723 listed Taiwanese firms, encompassing 11,940 firm-year observations from 2017 to 2024.

Several salient features in this study highlight the influence of corporate governance on firms’ financing costs. Firstly, the study identifies a significant negative relationship between corporate governance and firms’ cost of capital, indicating that firms with higher corporate governance rankings enjoy lower financing costs. This suggests that continuous efforts to strengthen governance can effectively reduce capital costs.

Secondly, when corporate governance improves, as reflected in an upgrade of a firm’s evaluation ranking, the firm’s cost of capital tends to decline. Conversely, when governance deteriorates, as reflected in a downgrade, the cost of capital increases. These results imply that creditors and investors can discern changes in firms’ governance quality through the evaluation system and adjust required returns accordingly.

Thirdly, the study finds that firms with stronger corporate governance are more likely to benefit from lower costs of capital compared with those with weaker governance, providing further insight into the relationship between governance quality and financing efficiency.

Finally, when a firm’s corporate governance ranking is upgraded, those with higher baseline governance levels achieve more pronounced reductions in capital costs, whereas firms with weaker governance may not experience similar benefits. Conversely, a downgrade leads to a greater increase in the cost of capital for firms with stronger governance than for those with weaker governance. Thus, compared to firms with weaker governance, firms with stronger governance demonstrate greater sensitivity in their cost of capital to changes in governance rankings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-C.H. and H.-C.L.; methodology, J.-C.H.; software, H.-C.L. and D.H.; validation, J.-C.H., and H.-C.L.; data curation, D.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-C.H., and H.-C.L.; writing—review and editing, J.-C.H., H.-C.L., and D.H.; visualization, D.H.; funding acquisition, J.-C.H. and H.-C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Social Science Planning Project of Fujian Province, grant number FJ2022T012 and FJ2025MGCA015.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Indicators and weightings for each dimension of the Taiwan corporate governance evaluation system.

Table A1.

Indicators and weightings for each dimension of the Taiwan corporate governance evaluation system.

| Panel A: 2014 to 2017 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension/Year | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | ||||||||

| INDs | Wt. | INDs | Wt. | INDs | Wt. | INDs | Wt. | |||||

| Protection of shareholders’ equity | 13 | 15% | 13 | 15% | 14 | 15% | 13 | 15% | ||||

| Equitable treatment of shareholders | 15 | 15% | 15 | 15% | 13 | 13% | 14 | 13% | ||||

| Board composition and operation | 35 | 35% | 35 | 35% | 33 | 32% | 32 | 32% | ||||

| Information transparency and protection of stakeholders’ interests | 21 | 20% | 21 | 20% | 23 | 22% | 21 | 22% | ||||

| Corporate social responsibility | 15 | 15% | 15 | 15% | 15 | 18% | 15 | 18% | ||||

| Total | 99 | 100% | 99 | 100% | 98 | 100% | 95 | 100% | ||||

| Panel B: 2018 to 2023 | ||||||||||||

| Dimension/Year | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | ||||||

| INDs | Wt. | INDs | Wt. | INDs | Wt. | INDs | Wt. | INDs | Wt. | INDs | Wt. | |

| Protection of shareholder rights and equitable treatment of shareholders | 17 | 19% | 17 | 20% | 16 | 20% | 16 | 22% | 16 | 20% | 18 | 22% |

| Strengthen board structure and operations | 29 | 34% | 29 | 33% | 28 | 33% | 26 | 31% | 26 | 33% | 25 | 31% |

| Enhance information transparency | 21 | 26% | 21 | 26% | 21 | 23% | 21 | 19% | 18 | 23% | 15 | 19% |

| Promoting Sustainable Development | 18 | 21% | 18 | 21% | 17 | 24% | 16 | 28% | 18 | 24% | 22 | 28% |

| Total | 85 | 100% | 85 | 100% | 82 | 100% | 79 | 100% | 78 | 100% | 80 | 100% |

Source: https://www.sfb.gov.tw (accessed on 12 August 2025); https://cgc.twse.com.tw (accessed on 12 August 2025). Notes: (1) INDs is the abbreviation for indicators. (2) Wt. is the abbreviation for weightings.

Table A2.

Definition of variables.

Table A2.

Definition of variables.

| Variables | Acronym | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: | ||

| Cost of capital | COC | The cost of capital (COC) is calculated as the weighted average of the cost of capital (WACC), which incorporates the cost of debt and cost of equity components. The cost of debt (COD) = [(interest expense + capitalized interest expense)/average of short-term and long-term debt]—TAIBOR (Taipei Interbank Offered Rate). The cost of equity capital (COE) is calculated using the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). Refer to the explanation of the robustness test variables below. The COC, COD, and COE variables are leading one period ahead (t + 1) of all independent variables. |

| Independent variables: theory-based variables | ||

| Corporate governance evaluation rankings Corporate governance evaluation ranking upgrade Corporate governance evaluation ranking downgrade | CGER CGER_UP CGER_DOWN | The corporate governance evaluation system publishes seven original corporate governance rankings, ranging from the top 5% to 100%. Based on existing literature [24,25], the multiple rankings are collapsed into seven categories, which provide an ordinal assessment of corporate governance quality. Each ranking category is mapped to a range of CG evaluation rankings as follows: Ranking category 7: top 5% Ranking category 6: 6–20% Ranking category 5: 21–35% Ranking category 4: 36–50% Ranking category 3: 51–65% Ranking category 2: 66–80% Ranking category 1: 81–100% The CGER variable takes on values ranging from 1 to 7, which correspond to the ranking categories from 1 to 7 and indicate the ordered quality of corporate governance from low to high. A dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if a firm upgrades its corporate governance evaluation ranking compared to the previous year, and 0 otherwise. A dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if a firm downgrades its corporate governance evaluation ranking compared to the previous year, and 0 otherwise. |

| High corporate governance evaluation ranking Medium corporate governance evaluation ranking Low corporate governance evaluation ranking | HCGER MCGER LCGER | A dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if a firm’s ranking category is 6–7 (i.e., top 5–20%), and 0 otherwise. A dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if a firm’s ranking category is 3–5 (i.e., 21–65%), and 0 otherwise. A dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if a firm’s ranking category is 1–2 (i.e., 66–100%), and 0 otherwise. |

| Firm characteristic variables: | ||

| Firm leverage | LEVG | Total labilities over total asset. |

| Book-to-market ratio | B/M | Total assets minus total liabilities divided by the market price of one of the firm’s shares multiplied by the number of shares outstanding. |

| Beta | BETA | Three years monthly stock returns are used to calculate Beta of firm by using a regression of stock return to market return. |

| Return on equity Dividend payout ratio | ROE DVID | Earnings before interest and tax to total equity of the firm. The firm’s yearly dividends divided by its net income. |

| Interest coverage ratio | ICR | Operating income before tax and depreciation divided by interest expense. |

| Sales growth ratio | SALSG | Sales in current year minus sales in last year to sales of last year. |

| Tobin’s Q | TBSQ | Market value plus book value of assets minus common equity and deferred taxes scaled by the book value of assets. |

| Control variables: | ||

| Firm size | SIZE | The natural log of total assets in thousands of Taiwan Dollars (TWD). |

| Industry dummy | IND | A dummy variable takes the value of one if a firm belongs to the “new economy” (e.g., the electronics and high-tech industries), and zero otherwise. |

| GDP growth rate | GDPG | Annual percentage growth rate of GDP per capita. |

| Robustness test variables: | ||

| Cost of debt | COD | The cost of debt (COD) = [(interest expense + capitalized interest expense)/average of short-term and long-term debt]—TAIBOR (Taipei Interbank Offered Rate). The cost of debt is leading one period ahead (t + 1) of all independent variables. |

| Cost of equity | COE | The cost of equity capital (COE) is calculated using the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). According to the CAPM, a firm’s cost of equity capital is equal to the risk-free rate (Rf) plus the market risk premium multiplied by βi. The following equation can be used to express it. E(Ri) = Rf + βi [E(Rm) − Rf] where E(Ri) represents the expected return on the stock of firm i, which is equivalent to the cost of equity capital (COE) for firm i. The risk-free rate (Rf) is calculated using the average one-year time deposit interest rates of nine major Taiwanese banks each year from 2017 to 2024. βi represents the systematic risk of a given firm i, calculated as the annual Beta value for each stock using a regression of stock return to market return based on annual data from the Taiwan Economic Journal (TEJ) database. E(Rm) represents the expected return of the market portfolio and is calculated based on the annual market returns (the Taiwan Weighted Stock Price Index) from 2017 to 2024. The cost of equity is leading one period ahead (t + 1) of all independent variables. |

References

- Myers, S.C.; Majluf, N.S. Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. J. Financ. Econ. 1984, 13, 187–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.C.W.; Wei, K.C.; Chen, Z. Disclosure, Corporate Governance, and the Cost of Equity Capital: Evidence from Asia’s Emerging Markets. 2003. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=422000 (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Khan, M.Y.; Javeed, A.; Cuong, L.K.; Pham, H. Corporate governance and cost of capital: Evidence from emerging markets. Risks 2020, 8, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlHares, A. Corporate governance and cost of capital in OECD countries. Int. J. Account. Inf. Manag. 2020, 28, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghouma, H.; Ben-nasr, H.; Yan, R. Corporate governance and cost of debt financing: Empirical evidence from Canada. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2018, 67, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F. Corporate governance and the cost of capital: An international study. Int. Rev. Financ. 2014, 14, 393–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessens, B.; Yurtoglu, B.B. Corporate governance in emerging markets: A survey. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2013, 15, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.A.; Sarkar, M.A.R.; Alharthi, M.; Ebn Jalal, M.J.; Rahman, M.N. Effect of integrated reporting quality disclosure on cost of equity capital in developed markets: Exploring the moderating role of corporate governance quality. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0324147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faysal, S.; Salehi, M.; Moradi, M. Impact of corporate governance mechanisms on the cost of equity capital in emerging markets. J. Pub. Aff. 2020, 21, e2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.C.; Claresta, V.; Bui, T.M.N. Green building, cost of equity capital and corporate governance: Evidence from US real estate investment trusts. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, Y.H. Does the release of corporate governance evaluation information decrease information asymmetry? Evidence from Taiwan. Corp. Manag. Rev. 2021, 41, 129–166. [Google Scholar]

- Tai, Y.H. The relation between the corporate governance evaluation and abnormal returns: The role of company financial performance. Asia-Pac. J. Account. Econ. 2020, 30, 1086–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, Y.H.; Hwang, N.C.R. Market reactions to corporate governance ranking announcement: Evidence from Taiwan. Abacus 2020, 56, 627–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, R.; Lopez-de-Silanes, F.; Schleifer, A.; Vishny, R.W. Investor protection and corporate governance. J. Financ. Econ. 2000, 58, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitton, T. A cross-firm analysis of the impact of corporate governance on the East Asian financial crisis. J. Financ. Econ. 2002, 64, 215–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkens, D.H.; Hung, M.; Matos, P. Corporate governance in the 2007-2008 financial crisis: Evidence from financial institutions worldwide. J. Corp. Financ. 2012, 18, 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gompers, P.; Ishii, J.; Metrick, A. Corporate governance and equity prices. Q. J. Econ. 2003, 118, 107–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, W.; Kim, J.B.; Song, B.Y. Internal governance, legal institutions and bank loan contracting around the world. J. Corp. Financ. 2012, 18, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.C.W.; Chen, Z.; Wei, K.C. Legal protection of investors, corporate governance, and the cost of equity capital. J. Corp. Financ. 2009, 15, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Cheng, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L. Investor protection and cost of debt: Evidence from dividend commitment in firm bylaws. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2020, 56, 627–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.; Erel, I.; Stulz, R.M.; Williamson, R. Differences in governance practice between U.S. and foreign firms: Management, causes, and consequences. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2009, 22, 3131–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.R.; Khurana, I.K.; Pereira, R. Disclosure incentives and effects on cost of capital around the world. Account. Rev. 2005, 80, 1125–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klock, M.S.; Mansi, S.; Maxwell, W.F. Does corporate governance matter to bondholders? J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2005, 40, 693–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashbaugh-Skaife, H.; Collines, D.W.; LaFond, R. The effects of corporate governance on firms’ credit ratings. J. Account. Econ. 2006, 42, 203–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alali, F.; Anandarajan, A.; Jiang, W. The effect of corporate governance on firm’s credit ratings: Further evidence using governance score in the United States. Account. Financ. 2012, 52, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassirzadeh, F.; Askarany, D.; Arefi-Asl, S. The Relationship between changes in corporate governance characteristics and intellectual capital. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, A.S.; Elmarzouky, M. Beyond Compliance: How ESG reporting influences the cost of capital in UK firms. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2024, 17, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebchuk, L.; Cohen, A.; Ferrell, A. What matters in corporate governance? Rev. Financ. Stud. 2009, 22, 783–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.C.; Tseng, J.J.; Lin, H.C. The impact of financial constraint on firm growth: An organizational life cycle perspective and evidence from Taiwan. Int. J. Organ. Innov. 2020, 12, 1–12. Available online: https://www.ijoi-online.org/index.php/current-issue/207 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Chowdhury, S.P.; Ahmed, R.; Debnath, N.C.; Ali, N.; Bhowmik, R. Corporate governance and capital structure decisions: Moderating role of inside ownership. Risks 2024, 12, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.C.; Huang, J.C.; You, C.F. Bank diversification and financial constraints on firm investment decision in a bank-based financial system. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).