1. Introduction

Agriculture has been globally practiced to produce food; however, food insecurity remains a critical issue, especially in Africa. According to Mathinya et al. [

1], the largest home of poor and hungry people in the world is Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) followed by Asia. Food security refers to a situation where people have the physical and financial access to safe, adequate, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and preferences for a healthy lifestyle [

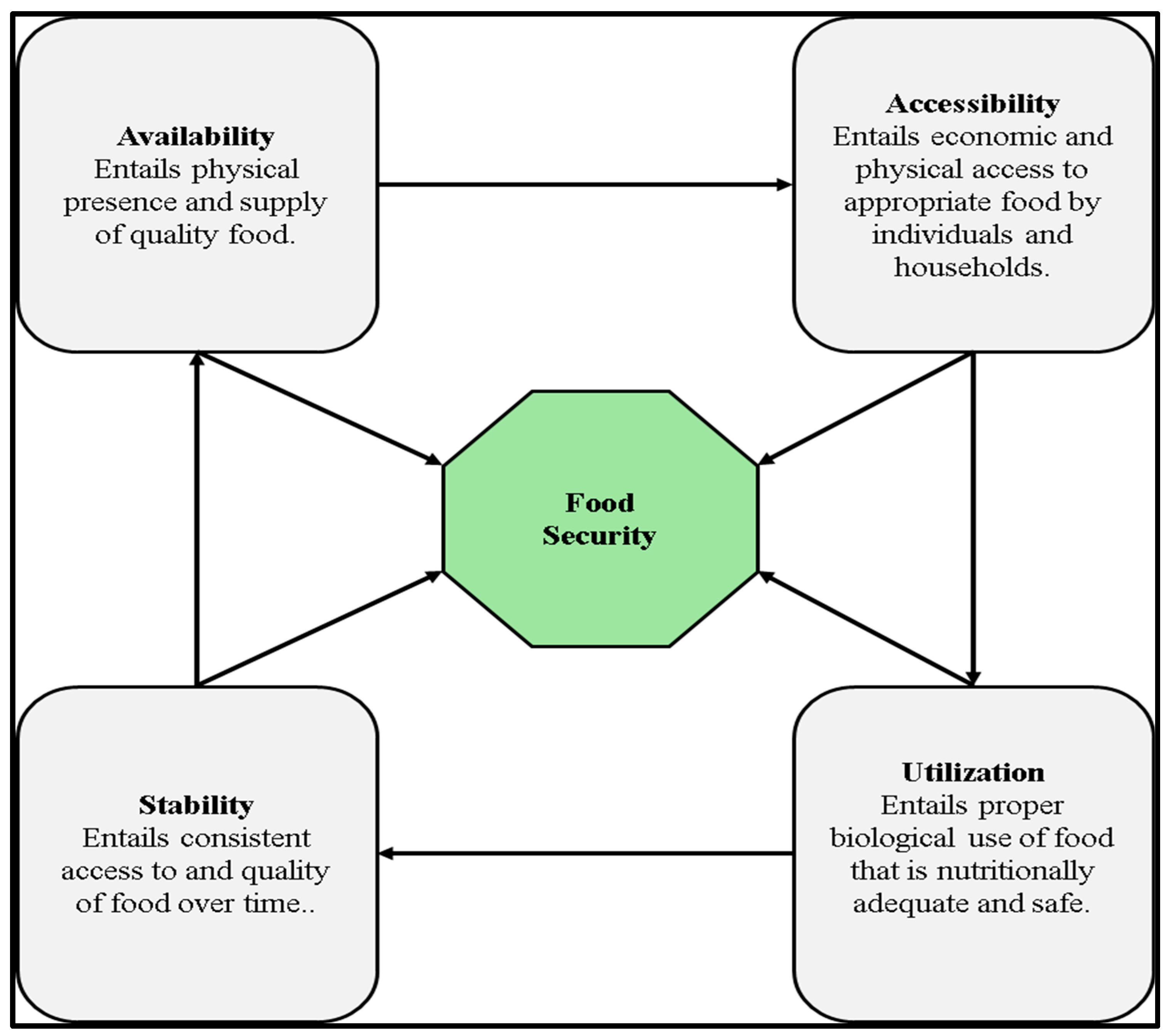

2]. Moreover, this concept consists of four main pillars, namely, food availability, food accessibility, food utilization, and stability of food supply. Therefore, failure to meet any of these pillars is regarded as food insecurity.

Of Africa’s population of about 256 million food-insecure people, 239 million people are situated in Sub-Saharan Africa [

3]. In general, nearly every one in three people in SSA is estimated to experience severe food insecurity [

4]. This highlights the severity of food insecurity as an issue of every citizen in SSA. Inadequate infrastructure, outdated tools, low production, lack of finance, corruption, as well as government policies have been noted as interconnected causes that contribute to food insecurity in SSA [

5]. These causes have means to reduce the farmers’ ability to produce sufficient and nutritious food for household consumption and to meet community demand. For instance, farmers’ production may be reduced due to lack of finance while the distribution of food may be delayed by poor infrastructure.

Sub-Saharan Africa is subjected to high urbanization, evident from past trends, rising from 32 million to 458 million people in the past 60 years starting from the year 1960 to 2020 [

6]. This fosters a need for urban production and provision of nutritious food, which is in line with the United Nations Agenda 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, including SDG 1 (no poverty) and SDG 2 (zero hunger). For these goals to be met, small-scale farmers can be considered as key players. Estimations indicate that small-scale farms account for the most food produced in SSA [

7] and generate more than 80% of the world’s food [

8]. However, these small-scale farmers face various difficulties such as lack of income, labor scarcity, lack of technology, poor access to information, market constraints, and certification barriers [

9]. These contradictions reveal the vital role played by these farmers and the issues they face regardless of their contribution. Moreover, they operate in informal settlements where there is a shortage of land and inadequate infrastructure, which further intensifies their food production challenges.

Looking at the significant role played by small-scale farmers, urban agriculture (UA) is then acknowledged as a viable strategy for reducing food insecurity in urban areas. It is defined as a process of raising animals and cultivating crops within urban settings for domestic use and selling on urban markets [

10]. According to Khumalo et al. [

11], UA offers fresh produce, nutritious agricultural products, balanced biodiversity, and efficient management of waste (composting). This highlights the potential of UA as a tool to assist farmers in sustaining their livelihoods. The role of UA is to reinforce Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by enhancing poverty alleviation (SDG 1), ending hunger (SDG 2), combating climate change (SDG 13), and improving life on land (SDG 15) [

12].

Urban agriculture is an alternative for promoting sustainable development. In fostering these mentioned SDGs, UA promotes household food security by availing fresh produce and income generation from market sales [

13]. It also creates job opportunities and the development of local trade [

14]. UA promotes the cultivation of different crops such as fruits, vegetables, cereals, and root tubers [

15]. This cultivation promotes efficient vegetation cover that helps to combat climate change through reductions in greenhouse gas emission, the effects of urban heat islands, as well as the management of storm water surfaces. UA encourages the use of recycled materials and organic wastes, which promote soil fertility while reducing landfill contributions [

16]. In addition, urban agriculture fosters other advantages such as community development, promoting health as well as education [

17].

Even though the significance of UA is widely recognized, little is known about the determinants of household food insecurity among urban small-scale farmers in SSA. This is linked with the fact that the majority of previous studies on food security and efforts to evaluate and improve food systems in SSA have mostly concentrated on rural areas [

18]. Generally, urban small-scale farming is determined by various factors such as environmental, socioeconomic, and institutional factors [

12]. However, large body of existing knowledge is based on metropolitan areas [

10], and it focuses on urban agriculture challenges and contribution in individual cities, for example, studies conducted in Malawi by Mkwambisi et al. [

19], Nigeria by Adedayo [

20], and South Africa by Menyuka et al. [

21]. This indicates a need for comparable analysis and improved knowledge about factors that determine food security in urban settings by small-scale farmers.

This review fills this gap through examining the existing research to pinpoint the main factors affecting food security in small-scale urban crop farming households. By evaluating findings from various studies, this review identifies and organizes the key influences on food insecurity, with a particular focus in the relationship between urban small-scale farming households and the factors (socioeconomic, environmental, and institutional) influencing participation and contribution to food insecurity. Understanding these determinants is crucial for generating information that is useful in crafting effective strategies to improve food security in the region. This will also contribute to ongoing debates about urban food security dynamics, which will spark researchers’ interest in further exploring this concept. Moreover, it disseminates knowledge for agricultural stakeholders, including small-scale farmers and researchers, as well as government policy makers.

Therefore, this literature review systematically synthesizes various studies conducted across the sub-Saharan Africa region based on the determinants of food insecurity in urban small-scale farming households. However, there is limited information demonstrating urban small-scale farming and the determinants of food insecurity in the SSA region. Therefore, the key objectives of this review are to identify the key determinants of food insecurity among urban small-scale crop farmers in SSA and furthermore to evaluate their influence on the household food insecurity of urban small-scale crop farmers. This review follows a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) format. This literature review is structured to include background, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion.

Conceptual Framework

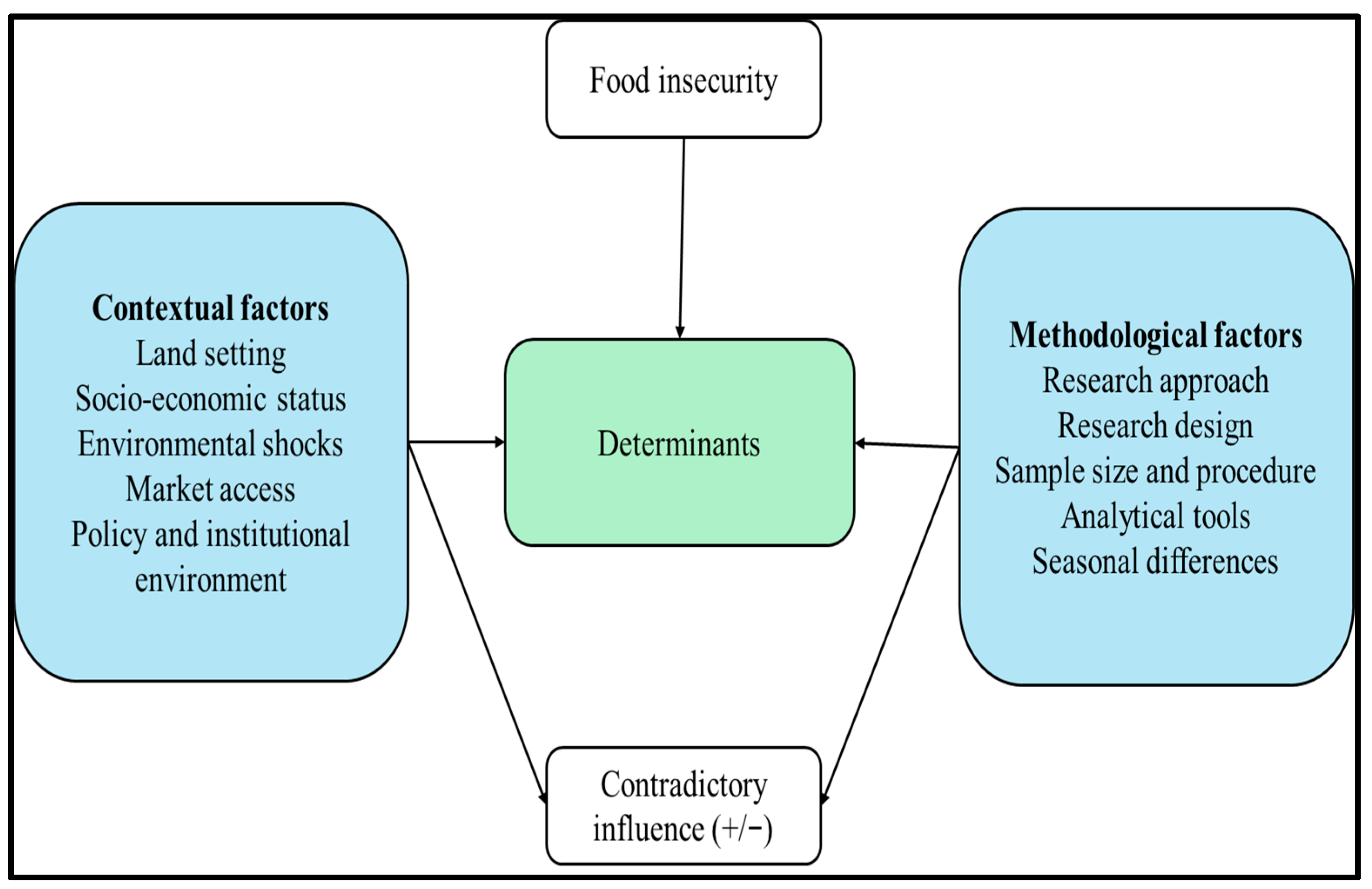

This review integrates the conceptual food security framework adopted from the Food and Agriculture Organization [

22] to explore the factors contributing to food insecurity. This framework entails four key pillars used to define food security: availability, accessibility, utilization, and stability. The combination of these pillars ensures the production of adequate, safe, and nutritious food to be consistently obtained and properly used while sustaining for future times. Small-scale crop farmers are challenged by several factors such as socioeconomic, environmental, and institutional factors that further exacerbate food insecurity in urban areas of the SSA region [

2]. This includes vulnerability to poverty and a high unemployment rate, climate change problems, and inadequate policies and infrastructure supporting agricultural production and food distribution. As a result, UA comes as an initiative to combat the issue of food insecurity among small-scale crop farmers. This is achieved through improving households’ food production for household consumption and income generation, which promotes adequate access to diverse nutritional food. Having access to adequate food promotes proper utilization and consistency, availability, and accessibility even for future times. Therefore, this results in improved urban household food security and sustainable livelihoods for urban citizens. Below is a diagram (

Figure 1) showing the food security conceptual framework.

2. Materials and Methods

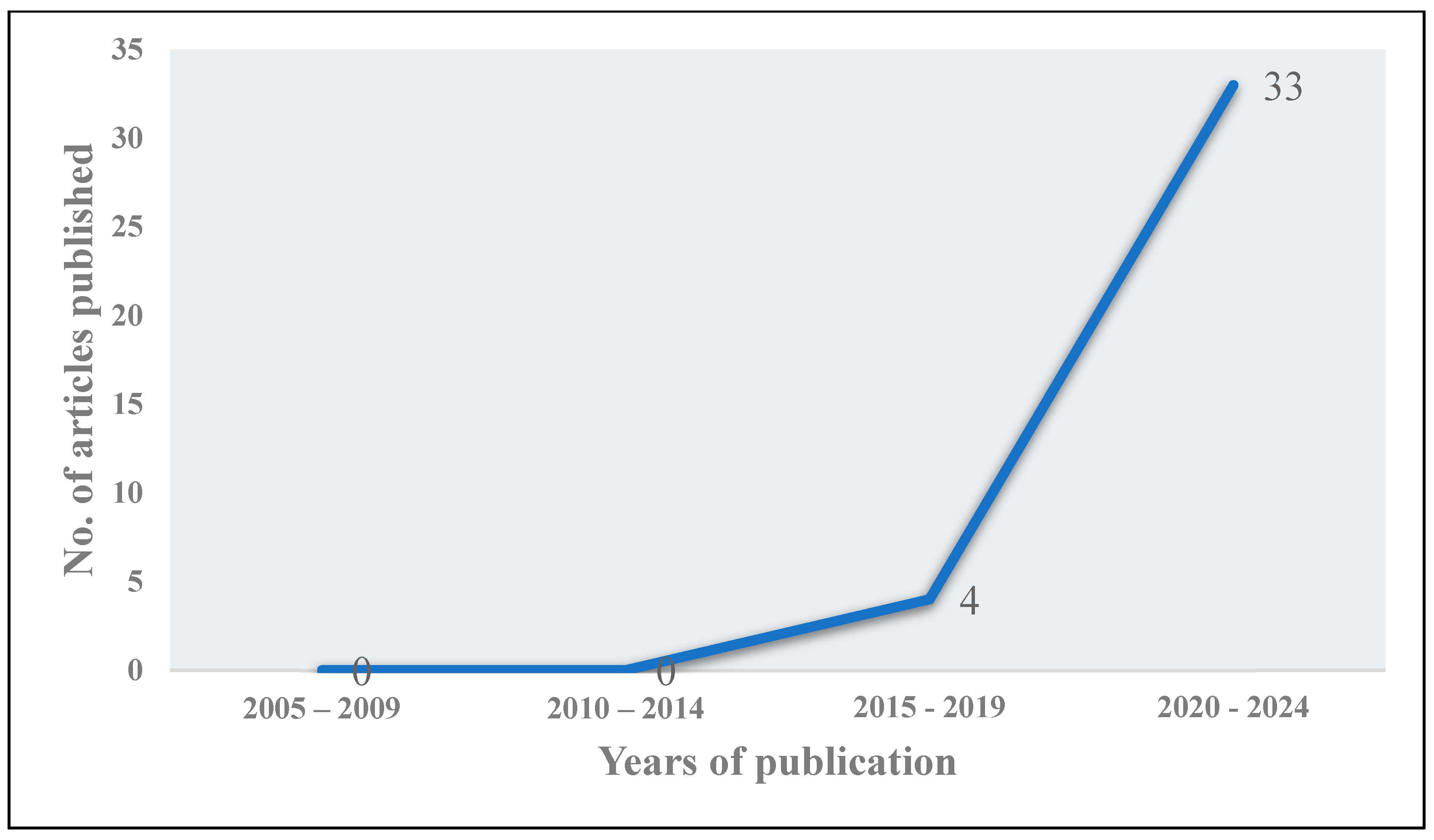

This review extracted relevant research conducted in the Sub-Saharan Africa region from the past 20 years, from 2005 to 2024. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to filter information and ensure the accuracy of retrieved data. After a systematic selection comprising accredited journals, book chapters, reports, and peer-reviewed articles, relevant information was carefully reviewed and used for this literature review. This was aided by considering only high-quality information that was not sourced from conference proceedings, unpublished studies, or papers that were not peer-reviewed. Furthermore, the words “determinants” AND “food insecurity” OR “food security” AND “urban agriculture” AND “small-scale farmers” AND “crop production” were used as keywords. These keywords were selected due to their relevance to the study aim and objectives as well as to retrieve the appropriate existing literature in the field of urban agriculture, food security and vocabulary of selected search engines. The inclusion of “determinants” captured insights on factors affecting food insecurity, “food insecurity or food security” targeted studies based on these concepts, “urban agriculture” specified the setting of farming activities, “small-scale farmers” targeted studies that include smallholder practices, and “crop production” specified the production from the expected studies. This study also used Boolean operators (AND, OR) to strategically combine keywords. Using these keywords enhanced retrieval of the literature while ensuring the omission of irrelevant information.

This study employed five databases, including ScienceDirect, Wiley Online Library, Web of Science, UNUZULU online library, and PubAg, to search for the relevant information. These databases were chosen based on their reliability, coverage, and relevance of published research based on agriculture and food security. Moreover, they were prioritized due to their ability to provide open access and interdisciplinary literature that is relevant to small-scale crop farming in SSA. Each database offered unique resources that significantly improved the depth and quality of findings relevant to the aim and objectives of this study. ScienceDirect specializes in the literature from multiple journals of agriculture and environmental sciences, while Web of Science offers access to high-impact journals that are widely cited [

23]. Wiley Online Library provides the literature from interdisciplinary studies relevant to this review, whereas UNIZULU online library captures both the local and global literature [

24]. Lastly, PubAg specializes in the food- and agriculture-related literature [

25]. Therefore, combining these databases ensured a strong search and collection of relevant evidence for this systematic review.

2.1. Search Strategy

This study developed a search strategy to ensure comprehensive search and identification of relevant information across all five employed databases. The search was conducted as follows:

A search through ScienceDirect database was conducted using the following terms, “determinants” AND “food insecurity” OR “food security” AND “urban agriculture” AND “small-scale farmers” AND “crop production”, which resulted in 26,149 reports. The search was narrowed down by applying the following filters: geography: “Sub-Saharan African countries”; search period: “2005 to 2024”; language: “English”; article type: “Research articles”; subject area: “Agriculture and biological sciences”, “Economics, Econometrics and Finance”, and “Social sciences”; publication title: “Journal of Agriculture and food research”, “Agricultural systems”, “Agriculture ecosystems and environment”, and “Food policy”; and availability: “Open access and open archive”. This resulted in 223 reports.

A search through Wiley Online Library was conducted using the following terms, “determinants” AND “food insecurity” OR “food security” AND “urban agriculture” AND “small-scale farmers” AND “crop production”, resulting in 18 394 reports. The search was then filtered using the following terms: geography: “Sub-Saharan African countries”; search period: “2005 to 2024”; publication type: “Journals”; and availability: “Open access content”. This resulted in 455 articles.

A search through Web of Science resulted in 2 924 reports. The following key terms were used: “determinants” AND “food insecurity” OR “food security” AND “urban agriculture” AND “small-scale crop farmers”. The search was refined using the following key terms: geography: “Sub-Saharan Africa”; search period: “2005 to 2024”; language: “English”; document type: “articles”; publication type: “food security”, “sustainability”, “frontiers in sustainable food system”, “frontiers in nutrition”, “agriculture food security”, “cogent food agriculture”, “food policy”, “agricultural economics”, as well as “agricultural and resource economics review”; and availability: “Open access”. This resulted in 107 articles.

A search through UNIZULU online library (beyond Zululand) was conducted using the following terms, “determinants” AND “food insecurity” OR “food security” AND “urban agriculture” AND “small-scale farmers” AND “crop production”, resulting in 6554 reports. The search was then tweaked using the following terms: geography: “Sub-Saharan African countries”; publication period: “2005 to 2024”; language: English; resource type: “articles”; journal title: “Nutrients”, “Food security”, “Frontiers in Public health”, and “PLOS one”; and availability: “open access and peer reviewed journals”. This resulted in 179 articles.

A search through PubAg was conducted using the following terms, “determinants” AND “food insecurity” OR “food security” AND “urban agriculture” AND “small-scale farmers” AND “crop production”, resulting in 40 266 reports. The search was then filtered using the following terms: geography: “Sub-Saharan African countries”; publication period: “2005 to 2024”; language: English; resource type: “articles”; journal title: “nutrients” and “sustainability”; and subject: “food security”. This resulted in 201 articles.

After filtering, the five databases used in this review resulted in the retrieval of 1165 articles that were evaluated. Below (

Table 1) is a table showing the links and results obtained during the search strategy for this review.

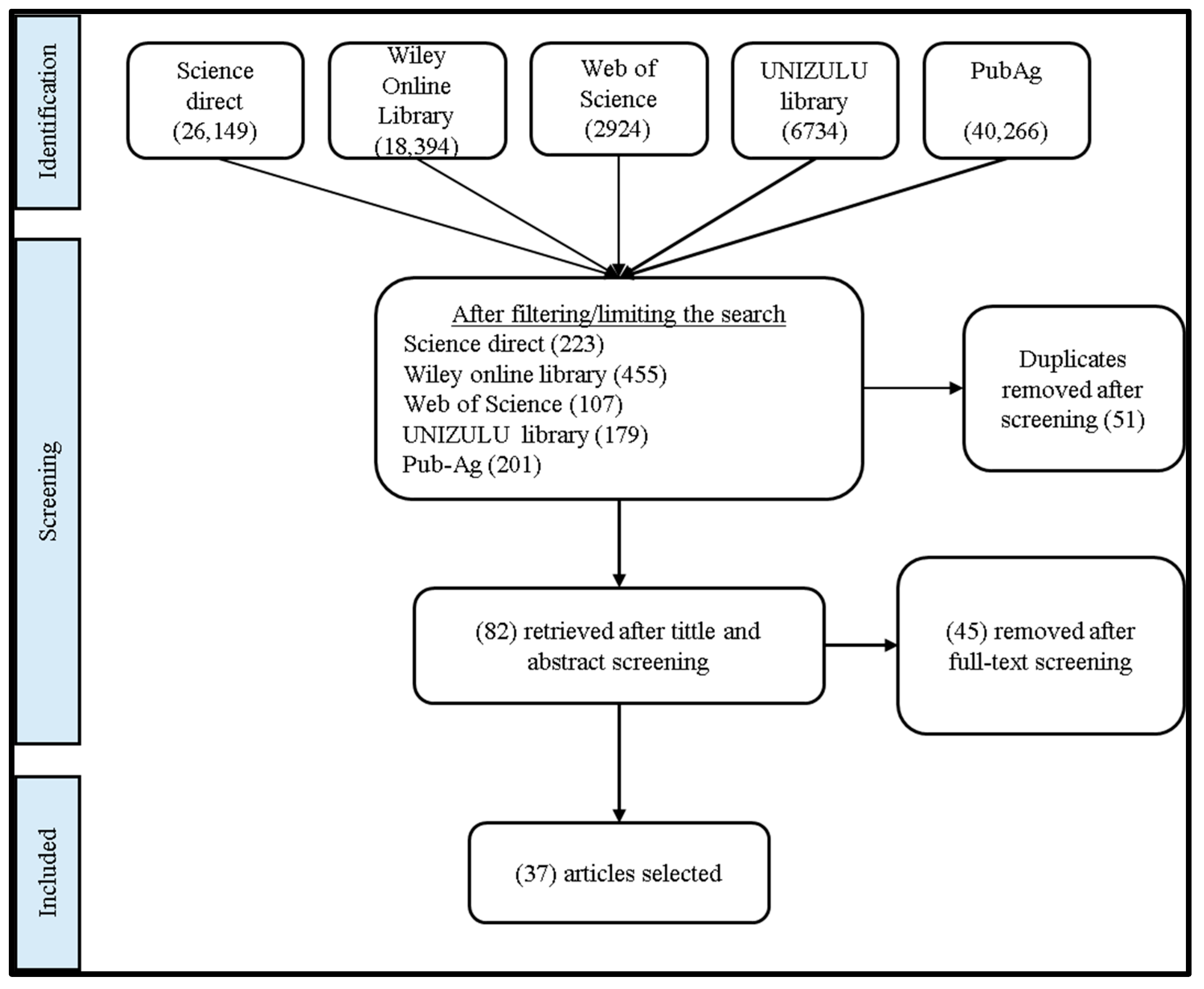

In conducting this systematic review, the PRISMA framework was employed to ensure consistency and transparency in the selection of articles.

Figure 2 below is a PRISMA diagram that depicts the entire process from identification of information (main search) to screening (filtering, duplicate removal, title and abstract screening, as well as full-text screening) and the final inclusion of studies used in this review. For

Supplementary Information regarding this review, the PRISMA checklist was completed, adopted from Page et al. [

26].

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria is defined as a technique used to specify research traits and filter unreliable data to match study goals [

27]. The focus on inclusion criteria for the systematic review was based on articles written in the English language, as it is known as a medium of instruction around the world [

28]. This study selected a publication period of 20 years from 2005 to 2024 to capture as much possible of the existing literature of the most two recent decades, thus ensuring the inclusion of earlier and recent insights. The focus was on determinants of food insecurity among small-scale urban crop farmers in areas of the Sub-Saharan Africa region due to its vulnerability to food insecurity issues. This is supported by Kohnert [

29], who indicated that Sub-Saharan Africa is the region facing the most food insecurity-related issues in the continent and the world. Additionally, this study selected peer-reviewed studies that are open access to ensure credibility and quality while promoting equal access of information without subscription barriers. The exclusion criteria included articles written in languages other than English; published before 2005 and after 2024; not focusing on factors influencing food insecurity; not focusing on urban small-scale urban crop farmers, for instance, livestock farmers and commercial farmers; and studies focusing on parts of the world other than Sub-Saharan Africa. These exclusions were made due to limited resources and feasibility challenges such as resource translation and access to journals that are not open access. Therefore, these criteria maintained the quality, validity, and relevancy of this study. Moreover, all duplicates’ articles were removed to ensure the accuracy and relevancy of the systematic review results.

Table 2 is a summary of the inclusion and exclusion criteria employed in this review.

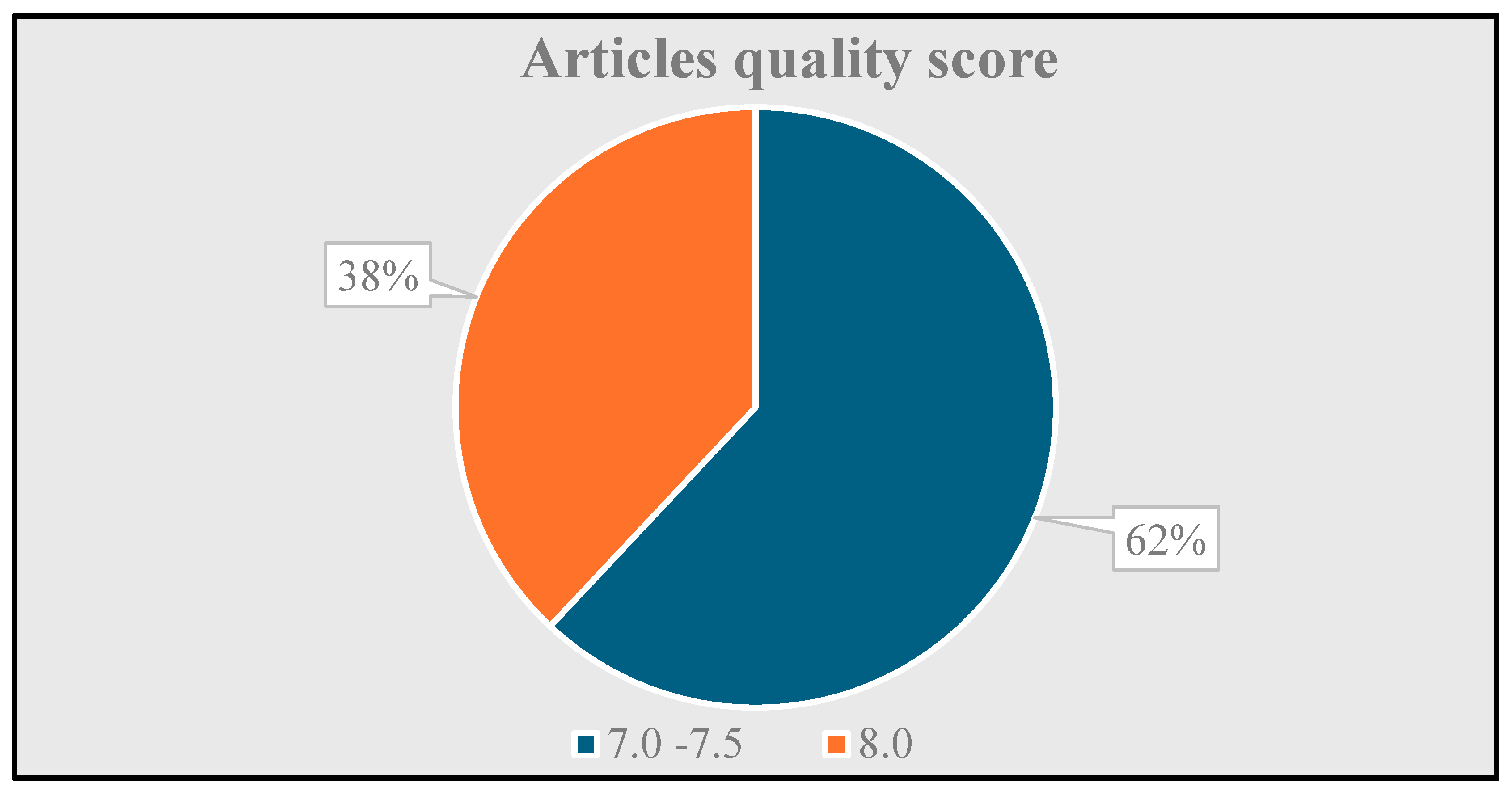

The eligibility criteria were applied to carefully review articles, focusing on the full text to perfectly meet the inclusion criteria for this review. Moreover, articles were tested for quality using an eight-point checklist adopted from Monteiro et al. [

30]. The aim was to promote high-quality input for systematic review through selecting articles with acceptable standards. Moreover, this enhanced the synthesis of the study results through the support of high-quality studies while strengthening credibility of the methodology. The quality assessment was evaluated using eight questions from the checklist shown in

Table 3. Articles were scored based on the quality of information relating to each question. Scores were categorized as follows: 0 = No; 0.5 = Hard to tell; 1 = Yes. This produced a total score of 8 points for each article, as shown in

Appendix A (

Table A1). All articles that failed to meet 50% (4 out of 8) of the criteria were removed; however, none scored less than 4 from the tested articles. In addition, articles that met the criteria were kept and included for the final synthesis of this review. Therefore, (37) articles were deemed eligible for this systematic literature review. This is mainly due to the large number of initial reports that were duplicates, were focused on rural settings and conducted outside the SSA region, and did not directly address determinants of food insecurity among urban small-scale crop farmers. The final included articles, therefore, present only the most relevant and appropriate evidence for the study objectives.

After quality testing, out of 37 articles included for this review, 23 articles scored between 7 and 7.5 points, which accounts for 62%. On the other hand, the remaining 14 articles scored 8 points, equivalent to 38%. This presents the appropriate quality of articles included in this systematic review, making a significant contribution towards the results drawn. Furthermore, findings from these studies will enrich the context through providing the most robust evidence captured from reliable studies. The application of eight-point quality testing on the selected articles for this systematic review is shown in

Figure 3 below.

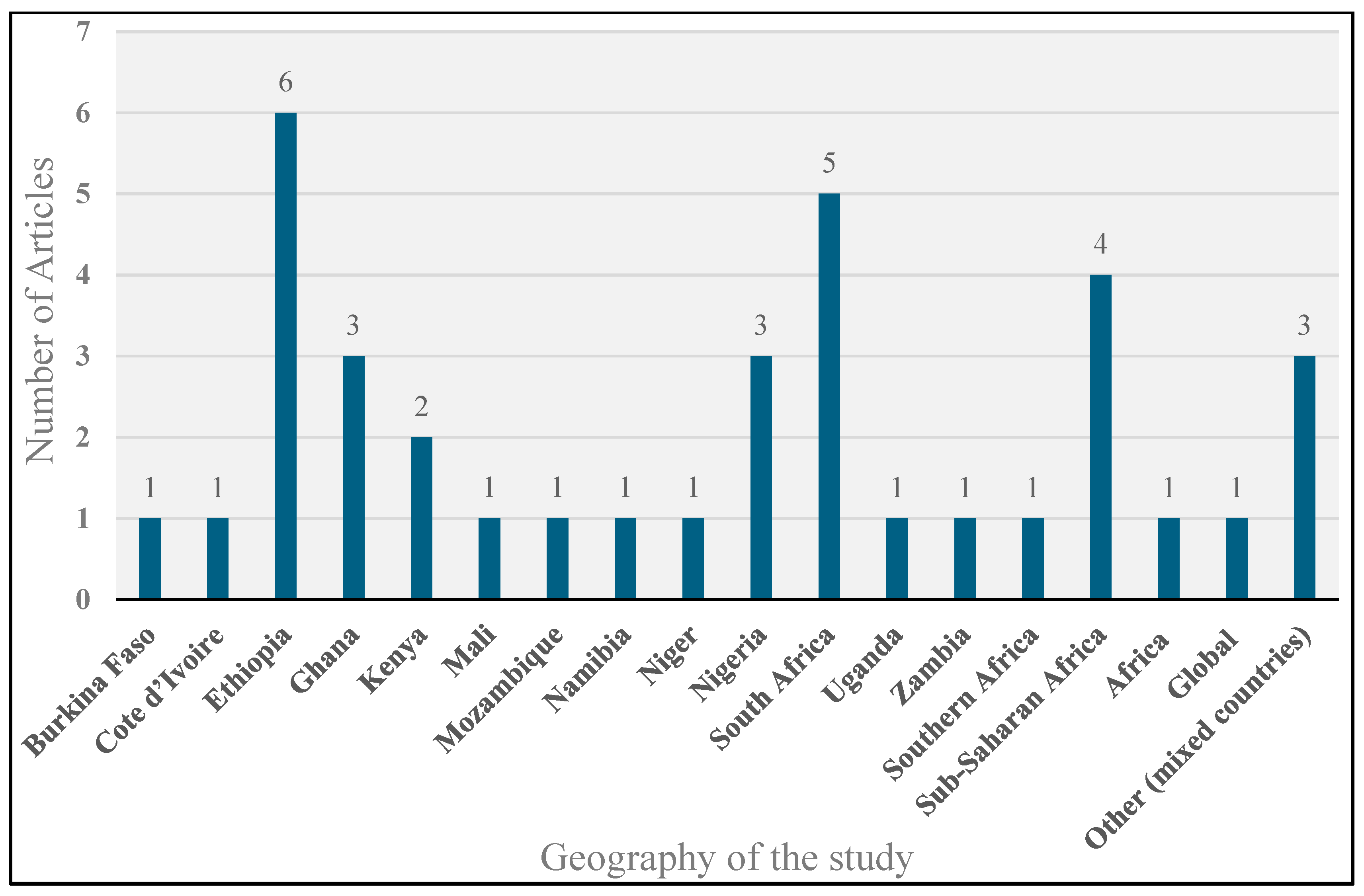

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

Data was imported using Endnote (Version 20.2.1), which assisted in carefully removing all duplicates and the continuation of data screening. The screening of articles focused on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, which specified the language, publication period, and findings based on factors influencing food insecurity, geography of the studies, as well as the type of article. After all irrelevant articles were removed from selection, a sample size of 37 articles was obtained. Findings were systematically summarized to draw conclusions, and some were interpreted using diagrammatic illustrations extracted from Microsoft Excel 365.

5. Conclusions

This review focuses on urban settings of Sub-Saharan Africa, where some people tend to engage in agricultural practices for food consumption and income generation. This tends to encourage the exchange of fresh food, promoting dietary diversity and nutrition, job creation, and a sustainable environment. Findings indicate an increase in the recognition of urban practices, though food insecurity is still a serious challenge. A significant role played by journals in creating an up-to-date and knowledgeable region is also recognized through the impact of articles. This systematic review also points out various factors affecting food insecurity among urban households. These food insecurity factors can be categorized into demographic, economic, social, institutional, and environmental factors. However, findings depicted a contradicting influence on food insecurity, which indicates a lack of and imbalance in government strategies and policy invention. SSA is made up of developing countries that often experience challenges of financial instability, poverty, inequality, climate vulnerability, government policy failure, and those relating to agriculture. Therefore, the identification of determinants influencing food insecurity reveals critical issues such as poor extension support, shortage of land availability and its ownership, and access to credit and markets, which are overlooked in several isolated studies. This review provides evidence and highlights the most significant matters that will guide the crafting of policies and strategies to improve urban agriculture. In light of food insecurity-related issues, government structures should interfere to assist small-scale farmers in addressing urban farming risks and uncertainties. Extension services such as training should be expanded in relation to farmers’ problems and emphasis on the adoption of new technology with sustainable urban agricultural practices (e.g., vertical and rooftop farming). Moreover, provision should be made for essential farming inputs such as subsidies (seeds and fertilizers) and access to land for farming, for instance, community gardens. Development and improvement of market access for farmers is crucial for sustainable urban food supply. Therefore, governments must structure urban markets and ensure trading contracts between farmers and institutional buyers such as hospitals, schools, and prisons. Areas for further study must look to risk mitigation strategies for enhancing urban small-scale farming households’ food security. Additionally, they could assess agricultural policy intervention in urban farming households, since results indicate issues of access to extension services, infrastructural gaps, and access to formal markets.